Abstract

Pediococcus species isolated from forage crops were characterized, and their application to silage preparation was studied. Most isolates were distributed on forage crops at low frequency. These isolates could be divided into three (A, B, and C) groups by their sugar fermentation patterns. Strains LA 3, LA 35, and LS 5 are representative isolates from groups A, B, and C, respectively. Strains LA 3 and LA 35 had intragroup DNA homology values above 93.6%, showing that they belong to the species Pediococcus acidilactici. Strain LS 5 belonged to Pediococcus pentosaceus on the basis of DNA-DNA relatedness. All three of these strains and strain SL 1 (Lactobacillus casei, isolated from a commercial inoculant) were used as additives to alfalfa and Italian ryegrass silage preparation at two temperatures (25 and 48°C). When stored at 25°C, all of the inoculated silages were well preserved and exhibited significantly (P < 0.05) reduced fermentation losses compared to that of their control in alfalfa and Italian ryegrass silages. When stored at 48°C, silages inoculated with strains LA 3 and LA 35 were also well preserved, with a significantly (P < 0.05) lower pH, butyric acid and ammonia-nitrogen content, gas production, and dry matter loss and significantly (P < 0.05) higher lactate content than the control, but silages inoculated with LS 5 and SL 1 were of poor quality. P. acidilactici LA 3 and LA 35 are considered suitable as potential silage inoculants.

Pediococci are a major component of the microbial flora which live in various types of forage crops; they commonly grow with other plant-associated lactic acid bacteria (LAB) during silage fermentation, and they may influence the fermentation characteristics of silage. Therefore, Pediococcus species and their effects on silage fermentation require further study. However, the phenotypic procedures to assign isolates to known species are difficult, because it is hard to differentiate readily between species of pediococci (22). This is particularly true of Pediococcus pentosaceus and Pediococcus acidilactici (14, 30). There have been many studies that report changes in numbers of epiphytic lactobacilli, enterococci, and leuconostocs during silage fermentation, but the characterization and identification of pediococci isolated from forage crops and their effect on the silage fermentation have not been reported.

In the present study, the characterization of Pediococcus species isolated from forage crops and their application to silage preparation were examined. In order to determine their taxonomic status, representative strains were also studied by 16S rRNA sequence analysis and DNA-DNA hybridization.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials and strains studied.

Corn (Zea mays) at ripe stage, sorghum (Sorghum bicolor) at dough stage, alfalfa (Medicago sativa) at flowering stage, Italian ryegrass (Lolium multiflorum) at heading stage, and guinea grass (Panicum maximum) at flowering stage were obtained from the National Grassland Research Institute (Nishinasuno, Tochigi, Japan).

Forage crops were chopped into 10-mm lengths, and three replicates of the same forage crop were used for microbiological analysis. Samples (10 g) were shaken well by hand with 90 ml of sterilized distilled water, and 10−1 to 10−8 serial dilutions were made in 0.85% sodium chloride solution. From each dilution, 0.05 ml of suspension was spread on agar plates. LAB were counted on both plate count agar (Nissui-Seiyaku Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) with bromocresol purple (0.04 g/liter) and glucose, yeast extract, peptone, and CaCO3 (GYP) agar after incubation in an anaerobic box (TE-HER Hard Anaerobox model ANX-1; Hirosawa Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) at 35°C for 2 to 3 days. The GYP medium contained 10.0 g of glucose, 5.0 g of yeast extract, 5.0 g of peptone, 2.0 g of sodium acetate, 0.25 g of Tween 80, 200 mg of MgSO4 · 7H2O, 10 mg of MnSO4 · 4H2O, 10 mg of FeSO4 · 7H2O, 5.0 g of NaCl, 5 g of CaCO3, and 1,000 ml of distilled water and was adjusted to pH 6.8. Approximately 20 colonies were isolated at random from the agar plates. Each colony was purified twice by streaking on MRS agar (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.). LAB were detected by the presence of a yellowish colony and a clear zone due to dissolving CaCO3. Lactobacilli, pediococci, leuconostocs, and enterococci were counted after morphological observation and determination of Gram staining, catalase reaction, spore formation, nitrate reduction, and fermentation type (16). Aerobic bacteria were counted on nutrient agar (Difco), and mold and yeasts were counted on potato dextrose agar (Nissui-seiyaku). The agar plates were incubated at 30°C for 2 to 4 days. Yeasts were distinguished from mold or bacteria by colony appearance and observation of cell morphology. Colonies were counted as viable numbers of microorganisms (CFU g of fresh matter [FM]−1).

Each colony of LAB was purified twice by streaking on MRS agar. The pure cultures were grown on MRS agar at 30°C for 24 h, and the colonies were collected with nutrient broth (Difco) containing 10% dimethyl sulfoxide and stored as stock cultures at −80°C for further examination. The type strains of Pediococcus were obtained from the Japan Collection of Microorganisms (JCM), The Institute of Physical and Chemical Research, Wako, Saitama, Japan.

Morphological, physiological, and biochemical tests.

Gram stain, morphology, catalase activity, spore formation, motility, nitrate reduction, and gas production from glucose were determined according to methods for LAB described by Kozaki et al. (16). Growth at different temperatures was observed in MRS broth after incubation at 10 and 15°C for 14 days and at 45 and 50°C for 7 days. Bile tolerance was determined in GYP broth containing bile at 10, 20, 30, and 40%. Salt tolerance was determined in MRS broth containing NaCl at 3.0 and 6.5%. Growth of LAB at pH 3.0, 3.5, 4.0, 4.5, 5.0, 5.5, and 6.0 was determined in MRS broth after incubation at 30°C for 7 days. Carbohydrate fermentation patterns were tested in GYP basal medium (16) containing 1% (wt/vol) carbohydrate. For tests of carbohydrate fermentation, the strains were cultivated on liver broth (20) at 30°C for 24 h and the broth was then diluted 10-fold with sterile saline solution. Carbohydrate fermentation patterns were examined with a semiautomatic system for bacterial identification as described by Benno (2). The isomers of lactate formed from glucose were determined enzymatically with reagents obtained from Boehringer GmbH, Mannheim, Germany.

16S rRNA sequencing.

The 16S rRNA sequence coding region was amplified by PCR performed in a PCR ThermalCycler (Takara Shuzo Co., Ltd., Ohtsu, Japan) as described by Suzuki et al. (28). The sequences of the PCR products were determined directly with a sequence kit (ALFexpress AutoCycle; Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, N.J.) with the prokaryotic 16S ribosomal DNA universal primers 27F (5′-AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG-3′) and 1492R (5′-GGTTACCTTGTTACGACTT-3′) (28). Nucleotide substitution rates (Knuc values) were calculated (15), and the phylogenetic tree was constructed by the neighbor-joining method (25). The topologies of trees were evaluated by bootstrap analysis of the sequence data with CLUSTAL W software based on 100 random resamplings (31). This sequence was aligned with the following published sequences from DDBJ, GenBank, and EMBL: Enterococcus faecalis JCM5803 (AB012212), Enterococcus faecium JCM 5804 (AB012213), Enterococcus gallinarum (AF039898), Enterococcus casseliflavus (AF039903), Lactobacillus casei JCM 1177 (D16553), Lactobacillus sake DSM 20017 (M58829), Lactobacillus alimentarius DSM 20249 (58804), Lactobacillus buchneri DSM 20057 (M58811), Lactobacillus brevis NCDO 1749 (X61134), Lactobacillus animalis NCD0 2425 (X61133), Lactobacillus aviarius DSM 20655 (M58808), Lactobacillus agilis DSM 20509 (M58803), Lactobacillus bifermentans DSM 20003 (M58809), Lactobacillus amylophilus DSM 20533 (M58806), Lactobacillus amylovorus DSM 20531 (M58805), Lactobacillus acidophilus ATCC 4365 (M58802), Lactobacillus acetotolerans DSM 20749 (M58801), Pediococcus dextrinicus JCM 5887 (D87679), Pediococcus parvulus JCM 5889 (D88528), P. pentosaceus DSM 20336 (58834), P. acidilactici NCDO 2767 (X95976), Pediococcus damnosus JCM 5886 (D87678), Aerococcus urinaeequi IFO 12173 (D87677), Lactococcus raffinolactis NCDO 617 (X54261), Lactococcus plantarum NCDO 1869 (X54259), Lactococcus piscium (X53905), Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis NCDO 2118 (X54260), and Lactococcus garvieae NCDO 2156 (X54262). Bacillus subtilis NCDO 1769 (X60646) was used as an outgroup organism.

DNA-DNA hybridization.

DNA was extracted from cells harvested from MRS broth incubated for 8 h at 30°C and was purified by the procedure of Saito and Miura (24). DNA base composition was determined by the method of Tamaoka and Komagata (29) with high-performance liquid chromatography following enzymatic digestion of DNA to deoxyribonucleosides. The equimolar mixture of four deoxyribonucleotides in a Yamasa GC kit (Yamasa Shoyu Co., Ltd., Choshi, Japan) was used as the quantitative standard. The DNA-DNA relatedness was determined by the method of Ezaki et al. (11) with photobiotin and microplates.

Laboratory silage preparation and chemical analysis.

Alfalfa and Italian ryegrass were harvested at the flowering stage. Silages were prepared by using a small-scale system of silage fermentation (4). The isolates and SL 1 (L. casei, isolated from a commercial inoculant [Snow Lact-L; Brand Seed Ltd., Sapporo, Japan]) were used. MRS broth was inoculated with these strains and incubated overnight. After incubation, the optical density of the suspension at 700 nm was adjusted to 0.42 with sterile 0.85% NaCl solution. The inoculum size of LAB was 1 ml of microbial suspension per kg of FM basis. Approximately 100-g portions of forage material, chopped into about 20-mm lengths, were packed into plastic film bags (Hiryu KN type; 180 by 260 cm; Asahikasei), and the bags were sealed with a vacuum sealer (BH 950; Matsushita). The silage treatments were designated untreated control, LA 3, LA 35, LS 5, and SL 1. The film bag silos were kept at 25 and 48°C. Three silos per treatment were used for chemical analysis.

The chemical compositions of the forage crops and silages were determined by conventional methods (21). The dry-matter (DM) content of the fresh forage was determined by oven drying at 70°C for 48 h, whereas that of the silages was determined by the removal of water by toluene distillation with ethanol correction (9). The organic acid contents were measured by high-performance liquid chromatography (23). The content of ammonia-nitrogen and lactic acid isomers was determined by enzymatic analysis according to the F-Kit UV method (Boehringer GmbH). Gas production and DM loss were determined by a small-scale fermentation loss test for silage as described by Cai et al. (4).

Statistical analysis.

Data on the chemical composition of the 60-day silages were analyzed by analysis of variance, and the significance of differences among means was tested by the multiple range test (10).

RESULTS

Counts of microorganisms.

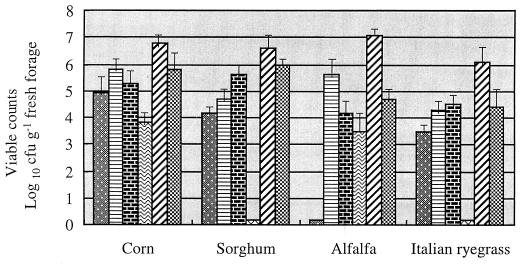

The counts of microorganisms in fresh forage are shown in Fig. 1. Overall, there were 106 aerobic bacteria; 104 to 105 enterococci, leuconostoc, mold, and yeast; and 103 and less lactobacilli and pediococci in each of the four forage crops (counts are in CFU g of FM−1).

FIG. 1.

Microbiological analysis of fresh forage crops. The

values are means ± standard deviations of three samples.

, lactobacilli;

, lactobacilli;

, leuconostocs;

, leuconostocs;

, enterococci;

, enterococci;

, pediococci;

, pediococci;

, aerobic bacteria;

, mold and yeast.

, aerobic bacteria;

, mold and yeast.

Physiological and biochemical properties.

A total of 41 strains were isolated from the forage crops, these isolates were gram-positive and catalase-negative tetrad cocci that did not produce gas from glucose and formed approximately equal quantities of l-(+)- and d-(−)-lactic acid. The carbohydrate fermentation patterns of Pediococcus species are shown in Table 1. These strains were divided into three groups on the basis of their carbohydrate fermentation patterns. Strains LA 3, LA 35, and LS 5 are representative isolates from groups A, B, and C, which were originally recovered from forage crops. Group A included 15 strains that produced acid from lactose and did not produce acid from maltose. Group B included eight strains that did not produce acid from lactose and produced acid from maltose. Group C was different from the other groups which produced acid from trehalose and did not produce acid from d-xylose. All of the isolates were easily distinguished from the type strains of Pediococcus species. The characteristics of strains LA 3, LA 35, LS 5, and L. casei SL 1 are shown in Table 2. Strains LA 3, LA 35, and LS 5 were homofermentative gram-positive tetrad cocci that formed l-(+)- and d-(−)-lactic acid. Strains LA 3 and LA 35 grew under low-pH (3.5) and high-temperature (50°C) conditions. Strain LS 5 did not grow below pH 4.0 or above 45°C. Strain SL 1 was a homofermentative Lactobacillus that formed lactic acid as an l-(+) isomer and grew at pH 3.5 but did not grow above 45°C.

TABLE 1.

Carbohydrate fermentation patterns of Pediococcus and Tetragenococcus speciesa

| Acid source | Results for:

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group A (n = 15) | Group B (n = 8) | Group C (n = 18) | P. acidilactici JCM 8797T | P. dextrinicus JCM 5887T | P. pentosaceus JCM 5890T | T. halophilus JCM 5888T | |

| l-Arabinose | + | + | + | + | − | + | + |

| d-Ribose | + | + | + | + | − | + | + |

| d-Xylose | + | + | − | + | − | + | + |

| Gluconate | − | − | − | W | − | − | W |

| Glucose | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Fructose | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Galactose | + | + | + | + | − | + | + |

| Mannose | + | + | + | + | − | + | + |

| Rhamnose | W | W | + | + | − | − | − |

| Cellobiose | + | + | + | + | W | + | + |

| Lactose | + | − | + | − | − | + | + |

| Maltose | − | + | + | − | W | + | + |

| Melibiose | − | − | − | − | − | + | − |

| Sucrose | − | − | − | − | − | + | − |

| Raffinose | − | − | − | − | − | + | − |

| Salicin | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Trehalose | − | − | + | + | W | + | + |

| Mannitol | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Sorbitol | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

All strains were gram-positive tetrad cocci that did not produce gas from glucose. The tests were performed by using the semiautomatic identification system. Reactions were determined at 30°C for 7 days. n, number of strains tested; +, positive; −, negative; W, weakly positive.

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of strains LA 3, LA 35, LS 5, and L. casei SL 1

| Characteristic | Valuea

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LA 3 | LA 35 | LS 5 | SL 1 | |

| Shape | Tetrad | Tetrad | Tetrad | Rod |

| Gram stain | + | + | + | + |

| Fermentation type | Homo | Homo | Homo | Homo |

| Optical form of lactate | dl | dl | dl | l-(+) |

| Growth (°C) | ||||

| 10 | − | − | + | − |

| 15 | + | + | + | + |

| 45 | + | + | + | − |

| 50 | + | + | − | − |

| Growth (pH) | ||||

| 3.0 | − | − | − | − |

| 3.5 | + | + | − | + |

| 4.0 | + | + | + | + |

| 4.5 | + | + | + | + |

| 5.0 | + | + | + | + |

| 5.5 | + | + | + | + |

| 6.0 | + | + | + | + |

+, positive; −, negative; Homo, homofermentative.

16S rRNA sequence.

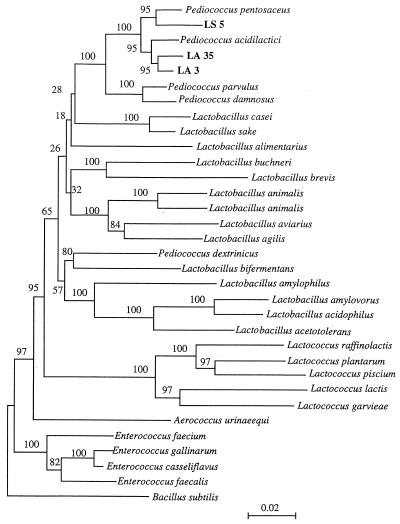

More than 1,500 bases of 16S rRNA of LA 3, LA 35, and LS 5 were determined. The phylogenetic tree shown in Fig. 2 was constructed from evolutionary distances by the neighbor-joining method. Following phylogenetic analysis, representative strains LA 3, LA 35, and LS 5 were placed in the cluster making up the genus Pediococcus. This cluster was recovered in 100% of bootstrap analyses. P. acidilactici JCM 8797T and P. pentosaceus JCM 5890T were the species most closely related to the strains LA 3, LA 35, and LS 5 in the phylogenetic tree, and they showed a high sequence homology value (>98%) with each other.

FIG. 2.

Phylogenetic tree derived from 16S ribosomal DNA sequence. The tree was created by the neighbor-joining method with Knuc values. The numbers indicate bootstrap values for the branch points.

DNA-DNA hybridization.

The results of DNA base composition and DNA-DNA hybridization analyses are shown in Table 3. Representative strains LA 3 and LA 35 had a G+C content range of 40.5 to 41.0 mol%. Strain LS 5 had a G+C content of 38.6 mol%. Strains LA 3 and LA 35 were 93.6 to 97.6% homologous with their representative strains, showing that they belonged to a single species which had the highest levels of DNA relatedness (>91.8%) to the type strains of P. acidilactici. Strain LS 5 was 88.8 or 97.5% homologous with the type strains of P. pentosaceus.

TABLE 3.

DNA base compositions and levels of DNA-DNA homology for Pediococcus species

| Strain | G+C content (mol%) | % DNA-DNA reassociation with strain:

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LA 3 | LA 35 | LS 5 | JCM 8797T | JCM 5890T | ||

| LA 3 | 41.3 | 100 | 93.6 | 9.2 | 90.2 | 25.0 |

| LA 35 | 40.5 | 97.6 | 100 | 9.0 | 96.7 | 28.4 |

| LS 5 | 38.6 | 16.5 | 16.9 | 100 | 22.3 | 88.8 |

| P. acidilactici JCM 8797T | 40.8 | 95.6 | 91.8 | 28.1 | 100 | 26.9 |

| P. dextrinicus JCM 5887T | 38.7 | 22.4 | 15.2 | 6.9 | 20.0 | 23.8 |

| P. parvulus JCM 5889T | 39.6 | 12.1 | 9.6 | 8.3 | 17.6 | 15.5 |

| P. pentosaceus JCM 5890T | 37.6 | 18.0 | 22.7 | 97.5 | 15.6 | 100 |

Silage quality and DM loss.

Silage quality and DM loss are shown in Table 4. When stored at 25°C, the alfalfa and Italian ryegrass silages that were treated with LA 3, LA 35, LS 5, and SL 1 were well preserved; the pH values, butyric acid, propionic acid, and ammonia-nitrogen contents, gas production, and DM loss were significantly (P < 0.05) lower and the lactic acid contents were significantly (P < 0.05) higher than those of the control. When stored at 48°C, silages inoculated with LA 3 and LA 35 were also well preserved and had significantly (P < 0.05) higher lactic acid contents and significantly (P < 0.05) lower pH values and butyric acid, propionic acid, and ammonia-nitrogen contents than the control. However, in silages inoculated with LS 5 and SL 1, these values were similar to those of the control in alfalfa and Italian ryegrass silages. Compared with the control, silages inoculated with LA 3 and LA 35 had significantly (P < 0.05) reduced DM loss and gas production, but silages inoculated with LS 5 and SL 1 resulted in similar levels of these contents in alfalfa and Italian ryegrass silages.

TABLE 4.

Fermentation quality of silage ensiled at 25 or 48°C for 60 daysa

| Parameter | Value for:

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alfalfa

silage

|

Italian ryegrass silage

|

|||||||||

| Ut | LA 3 | LA 35 | LS 5 | SL 1 | Ut | LA 3 | LA 35 | LS 5 | SL 1 | |

| 25°C | ||||||||||

| pH | 4.85 | 4.40 | 4.20 | 4.50 | 4.15 | 4.60 | 4.15 | 4.14 | 4.20 | 4.00 |

| DM (% FM) | 19.62 | 20.16 | 20.21 | 20.20 | 20.24 | 20.70 | 21.20 | 20.50 | 20.34 | 20.80 |

| Lactic acid (% FM) | 0.42B | 0.94A | 1.01A | 0.89A | 1.05A | 0.85B | 1.49A | 1.65A | 1.42A | 1.60A |

| Acetic acid (% FM) | 0.60 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.55 | 0.53 | 0.21 | 0.20 | 0.27 | 0.18 | 0.25 |

| Butyric acid (% FM) | 0.63A | 0.06B | ND | 0.10B | ND | 0.1A | 0.04B | 0.02B | 0.06B | 0.01B |

| Propionic acid (% FM) | 0.23 | 0.00 | ND | 0.00 | ND | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | ND |

| Ammonia-N (% DM) | 0.66A | 0.45B | 0.38B | 0.46B | 0.40B | 0.47A | 0.28B | 0.32B | 0.36AB | 0.25B |

| Gas production (liters/kg of FM) | 5.98A | 1.81B | 1.96B | 2.01B | 1.50B | 5.38A | 1.18B | 1.01B | 1.33B | 1.14B |

| DM loss (% DM) | 7.27A | 4.25B | 4.05B | 4.33B | 4.01B | 6.23A | 3.86B | 3.57B | 4.20B | 3.64B |

| 48°C | ||||||||||

| pH | 5.10 | 4.76 | 4.37 | 5.10 | 5.00 | 4.82 | 3.77 | 3.85 | 4.85 | 4.80 |

| DM (% FM) | 19.33 | 19.87 | 20.00 | 19.96 | 19.30 | 20.50 | 22.20 | 21.60 | 20.15 | 20.40 |

| Lactic acid (% FM) | 0.31B | 0.74A | 0.80A | 0.35B | 0.38B | 0.50B | 1.03A | 0.98A | 0.53B | 0.62B |

| Acetic acid (% FM) | 0.29 | 0.20 | 0.18 | 0.30 | 0.27 | 0.15 | 0.10 | 0.13 | 0.12 | 0.20 |

| Butyric acid (% FM) | 0.78A | 0.13B | 0.12B | 0.70A | 0.75A | 0.45A | 0.02B | 0.04B | 0.31A | 0.39A |

| Propionic acid (% FM) | 0.02 | ND | 0.01 | 0.02 | ND | 0.02 | ND | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| Ammonia-N (% DM) | 0.72A | 0.56B | 0.48B | 0.78A | 0.75A | 0.32A | 0.17B | 0.19B | 0.27A | 0.30A |

| Gas production (liters/kg of FM) | 7.10A | 1.98B | 1.90B | 5.50A | 5.68A | 6.05A | 2.13B | 1.98B | 4.23A | 5.03A |

| DM loss (% DM) | 9.78A | 4.33B | 4.20B | 8.24A | 9.35A | 8.00A | 4.40B | 4.26B | 7.84A | 7.91A |

Values are means of three silage samples. Means in the same row within a silage type with different letters differ (P < 0.05). Ut, control; ND, not detected.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The 16S rRNA sequences of LA 3, LA 35, and LS 5 have been deposited in the DDBJ database under accession no. AB018213, AB018214, and AB018215, respectively.

DISCUSSION

Pediococci are often found living in association with plant material, dairy products, and foods produced by LAB (5, 12, 13, 17, 18), and several papers have reported pediococci as the dominant microbial population on forage crops and silage. Some isolates from forage crops and silage have been identified as P. acidilactici and P. pentosaceus (17, 18). However, available phenotypic procedures to assign isolates to known species are difficult because it is not easy to differentiate clearly between species of pediococci (14, 22, 30). In the present study, the isolates were gram-positive and catalase-negative tetrad cocci that did not produce gas from glucose and formed approximately equal quantities of l-(+)- and d-(−)-lactic acid. These properties show that these strains belong to the genus Pediococcus. Strains in groups A, B, and C were different from the type strains of P. acidilactici and P. pentosaceus in some carbohydrate fermentation patterns, such as those of lactose, maltose, trehalose, and d-xylose, and could not be identified to the species level on the basis of phenotypic characteristics.

The genetic interrelationships of members of the LAB have been studied extensively in 16S rRNA sequence and DNA-DNA hybridization experiments, and new genera and species have been added (3, 6–8). Recent results have clearly indicated that the genera Pediococcus, Enterococcus, Leuconostoc, Weissella, and Lactococcus exhibit a high degree of sequence similarity to each other and form a phylogenetically coherent group that is separate from other bacteria (3, 6, 8). In the present study, the representative strains LA 3, LA 35, and LS 5 were placed in the genus Pediococcus in the phylogenetic tree, confirming that these strains belong to the genus Pediococcus and that they are the species most closely related to P. acidilactici and P. pentosaceus. The DNA-DNA hybridization results demonstrated that strains LA 3 and LA 35 could be assigned to P. acidilactici, and LS 5 could be assigned to P. pentosaceus.

The addition of LAB inoculants at ensiling is intended to ensure rapid and vigorous fermentation that results in faster accumulation of lactic acid, lower pH values at earlier stages of ensiling, and inhibition of growth of some pathogenic bacteria (19). Many studies (19, 26, 27) have shown the advantage of such inoculants. Generally, moist dairy farm silage is based on a natural lactic acid fermentation. The epiphytic LAB transform the water-soluble carbohydrates into organic acid in the ensiling process. As a result, the pH is reduced and the forage is preserved (19). However, LAB, especially lactobacilli, are present in forage in very low numbers (5, 17, 18). When LAB fail to produce sufficient lactic acid during fermentation to reduce the pH and inhibit the growth of clostridia, the resulting silage will be of poor quality. As shown in Fig. 1 and Table 4, low numbers of lactobacilli (<103 CFU g of FM−1) and high numbers of aerobic bacteria (>105 CFU g of FM−1) were present in the material, and poor-quality silage resulted. The factors involved in assessing fermentation quality include the chemical composition of the silage material and the physiological properties of epiphytic bacteria. Generally, alfalfa and Italian ryegrass have relatively low water-soluble-carbohydrate content and low numbers of lactobacilli. During silage fermentation, the lactobacilli could not produce sufficient lactic acid to inhibit the growth of harmful bacteria, and the resulting silage was of poor quality. Therefore, it is necessary to use some bacterial inoculants to control microbes in silage fermentation.

The changes in temperature during silage fermentation are well known. Generally, fermentation heating in the silage was consistently correlated with microorganism development and plant respiration. The temperature rises rapidly in the early stage of the ensiling processes and reaches over 45°C (1). In addition, the growth of some lactobacilli would be inhibited by the high-temperature conditions. In our study, when stored at 25°C, silages inoculated with P. acidilactici LA 3 and LA 35, P. pentosaceus LS 5, and L. casei SL 1 were well preserved, with significantly (P < 0.05) reduced fermentation loss compared with the control in alfalfa and Italian ryegrass silages. The most plausible explanation lies in the physiological properties of LAB. The strains LA 3, LA 35, LS 5, and SL 1 used in this study were homofermentative LAB which grew well at 25°C and under low-pH (3.5) conditions. Therefore, inoculation with these LAB may result in beneficial effects by promoting the propagation of LAB and by inhibiting the growth of clostridia and aerobic bacteria, as well as by decreasing the amount of gas production and DM loss. On the other hand, when stored at 48°C, silages inoculated with strains LA 3 and LA 35 were also well preserved, with significantly (P < 0.05) lower pH, butyric acid and ammonia-nitrogen content, gas production, and DM loss and significantly (P < 0.05) higher lactate content than the control. However, silages inoculated with LS 5 and SL 1 were of poor quality and were of quality similar to the control in the two kinds of silage. These results reflect the observation that strains LA 3 and LA 35 could grow at 50°C but strains LS 5 and SL 1 did not grow at that temperature and may die above 45°C. Therefore, during silage fermentation, isolates LA 3 and LA 35 improved silage quality and reduced fermentation loss at high temperatures while strains LS 5 and SL 1 were unable to grow and ferment WSC to produce sufficient lactic acid, resulting in the pH value of silage not falling to less than 4.2 and allowing butyric acid fermentation by clostridia to occur.

The results confirmed that P. acidilactici LA 3 and LA 35 were suitable as potential silage inoculants and that they were more effective in improving silage quality than P. pentosaceus LS 5 and the L. casei inoculant strain SL-1 under high-temperature (48°C) conditions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank J. A. Hudson (Environmental Science and Research Ltd., Christchurch Science Centre, Christchurch, New Zealand) for reading the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barnett A J G. Silage fermentation. London, England: Butterworth Scientific Publication; 1954. pp. 111–123. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benno Y. A semi-automatic system for bacterial identification. Riken Rev. 1996;12:57–58. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cai J, Collins M D. Evidence for a close phylogenetic relationship between Melissococcus pluton, the causative agent of European foulbrood disease, and the genus Enterococcus. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1994;44:365–367. doi: 10.1099/00207713-44-2-365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cai Y, Ohmomo S, Ogawa M, Kumai S. Effect of NaCl-tolerant lactic acid bacteria and NaCl on the fermentation characteristics and aerobic stability of silage. J Appl Microbiol. 1997;83:307–313. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.1997.00229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cai Y, Benno Y, Ogawa M, Ohmomo S, Kumai S, Nakase T. Influence of Lactobacillus spp. from an inoculant and of Weissella and Leuconostocspp. from forage crops on silage fermentation. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:2982–2987. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.8.2982-2987.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Collins M D, Williams A M, Wallbanks S. The phylogeny of Aerococcus and Pediococcus as determined by 16S rRNA sequence analysis: description of Tetragenococcusgen. nov. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1990;70:255–262. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1097(05)80004-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Collins M D, Ash C, Farrow J A, Wallbank S, Williams A M. 16S ribosomal ribonucleic acid sequence analyses of lactobacilli and related taxa. Description of Vagococcus fluvialisgen. nov., sp. nov. J Appl Bacteriol. 1989;67:453–460. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1989.tb02516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Collins M D, Metaxopoulos J, Wallbanks S. Taxonomic study on some leuconostoc-like organisms from fermented sausages: description of a new genus Weissella for the Leuconostoc paramesenteroidesgroup of species. J Appl Bacteriol. 1993;75:595–603. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1993.tb01600.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dewar W A, McDonald P. Determination of dry matter in silage by distillation with toluene. J Sci Food Agric. 1961;12:790–795. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duncan D B. Multiple range and multiple F test. Biometrics. 1955;11:1–42. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ezaki T, Hashimoto Y, Yabuuchi E. Fluorometric deoxyribonucleic acid-deoxyribonucleic acid hybridization in microdilution wells as an alternative to membrane filter hybridization in which radioisotopes are used to determine genetic relatedness among bacteria strains. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1989;39:224–229. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gashe B A. Involvement of lactic acid bacteria in the fermentation of Tef (Eragrostis tef), an Ethiopian fermented food. J Food Sci. 1985;50:800–801. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gashe B A. Kocho fermentation. J Appl Bacteriol. 1987;62:473–474. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Judicial Commission. Opinion 68. Designation of strain B213c (DSM 20284) in place of strain NCDO 1859 as the type strain of Pediococcus acidilacticiLindner 1887. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1996;46:835. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kimura M, Ohta T. On the stochastic model for estimation of mutation distance between homologous proteins. J Mol Evol. 1972;2:87–90. doi: 10.1007/BF01653945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kozaki M, Uchimura T, Okada S. Experimental manual of lactic acid bacteria. Tokyo, Japan: Asakurasyoten; 1992. pp. 34–37. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin C, Bolsen K K, Brent B E, Fung D Y C. Epiphytic lactic acid bacteria succession during the pre-ensiling and ensiling periods of alfalfa and maize. J Appl Bacteriol. 1992;73:375–387. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lin C, Bolsen K K, Brent B E, Hart R A, Dickerson J T, Feyerherm A M, Aimutis W R. Epiphytic microflora on alfalfa and whole-plant corn. J Dairy Sci. 1991;75:2484–2493. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(92)78010-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McDonald P, Henderson N, Heron S. The biochemistry of silage. 2nd ed. Marlow, Berkshire, United Kingdom: Chalcombe Publications; 1991. pp. 48–249. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mitsuoka, T. 1969. Vergleichende Untersuchungen uber die Laktobazillen aus dem Faeces von Menschen, Schweinen und Huhnern. Zentbl. Bakteriol. Parasitenkd. Infektionskr. Hyg. Abt. 1 Orig. 210:32–51. [PubMed]

- 21.Morimoto H. Experimental method of animal nutrition. Tokyo, Japan: Youkendo; 1971. pp. 284–285. . (In Japanese.) [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nigatu A, Ahrne S, Gashe B A, Molin G. Randomly amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) for discrimination of Pediococcus pentosaceus and Pediococcus acidilactici and rapid grouping of Pediococcusisolates. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1998;26:412–416. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ohmomo S, Tanaka O, Kitamoto H. Analysis of organic acids in silage by high-performance liquid chromatography. Bull Natl Grassl Res Inst. 1993;48:51–56. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saitou H, Miura K. Preparation of transforming deoxyribonucleic acid by phenol treatment. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1963;72:619–629. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saitou N, Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol. 1987;4:406–425. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sebastian S, Phillip L E, Fellner V, Idziak E S. Comparative assessment of bacterial inoculated corn and sorghum silages. J Anim Sci. 1996;71:505–514. doi: 10.2527/1996.742447x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sharp R, Hooper P G, Armstrong D J. The digestion of grass silages produced using inoculants of lactic acid bacteria. Grass Forage Sci. 1994;49:42–53. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Suzuki K, Sasaki J, Uramoto M, Nakase T, Komagata K. Agromyces mediolanus sp. nov., nom. rev., comb. nov., a species for “Corynebacterium mediolanum” Mamoli 1939 and for some aniline-assimilating bacteria which contain 2,4-diaminobutyric acid in the cell wall peptidoglycan. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1996;46:88–93. doi: 10.1099/00207713-46-1-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tamaoka J, Komagata K. Determination of DNA base composition by reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1984;124:11–16. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tanasupawat S, Okada S, Kozaki M, Komagata K. Characterization of Pediococcus pentosaceus and Pediococcus acidilactici strains and replacement of the type strains of P. acidilacticiwith the proposed neotype DSM 20284. Request for an opinion. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1993;43:860–863. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thompson J D, Higgins D G, Gibson T J. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting position specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]