Abstract

Drought stress is known to significantly limit crop growth and productivity. Lateral organ boundary domain (LBD) transcription factors—particularly class-I members—play essential roles in plant development and biotic stress. However, little information is available on class-II LBD genes related to abiotic stress in maize. Here, we cloned a maize class-II LBD transcription factor, ZmLBD5, and identified its function in drought stress. Transient expression, transactivation, and dimerization assays demonstrated that ZmLBD5 was localized in the nucleus, without transactivation, and could form a homodimer or heterodimer. Promoter analysis demonstrated that multiple drought-stress-related and ABA response cis-acting elements are present in the promoter region of ZmLBD5. Overexpression of ZmLBD5 in Arabidopsis promotes plant growth under normal conditions, and suppresses drought tolerance under drought conditions. Furthermore, the overexpression of ZmLBD5 increased the water loss rate, stomatal number, and stomatal apertures. DAB and NBT staining demonstrated that the reactive oxygen species (ROS) decreased in ZmLBD5-overexpressed Arabidopsis. A physiological index assay also revealed that SOD and POD activities in ZmLBD5-overexpressed Arabidopsis were higher than those in wild-type Arabidopsis. These results revealed the role of ZmLBD5 in drought stress by regulating ROS levels.

Keywords: LBD, drought stress, ROS, stomata, maize

1. Introduction

Drought tolerance is a complex trait that involves a series of adaptive changes in the molecular, cellular, physiological, and morphological levels [1]. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) accumulated under drought stress are versatile in plant development and environmental stress responses [2,3]. ROS act as secondary messengers in stress signaling pathways by triggering defensive/adaptive responses to stress at low-to-moderate concentrations, such as stomatal closure, deposition of lignin and cellulose, and modulation of protein activity and gene expression [3,4]. In addition, ABA stimulates the production of H2O2 through NADPH oxidase in guard cells [4]. In rice, Abscisic acid, Stress and Ripening5 (ASR5) is known to potentiate ABA biosynthesis, the expression of peroxidase 24 precursor, H2O2 accumulation, and stomatal closure, as well as the osmotic and drought tolerance of the seedlings [5]. However, ROS causes growth retardation and eventual cell death once a threshold of ROS concentration is reached [2]. Therefore, ROS detoxification is essential for cell survival, metabolism, and development. Recent studies reveal that increased expression of ROS-scavenging-related genes can improve plants’ drought tolerance. Yang et al. found that drought-tolerant maize seedlings have higher antioxidant activities and, consequently, accumulate fewer ROS than sensitive genotypes when exposed to water deficit [6]. Overexpression of OsLG3 significantly improves rice’s tolerance to drought stress by triggering the ROS scavenging system, whereas suppression of OsLG3 results in decreased ROS scavenging activity and increased drought susceptibility [7].

Lateral organ boundary domain (LBD) proteins, defined by a conserved lateral organ boundary (LOB) domain, belong to the plant-specific transcription factor family [8]. The characteristic LOB domain comprises a C-block containing four cysteine residues (CX2CX6CX3C) required for DNA binding, a Gly-Ala-Ser (GAS) block, and a leucine zipper-like coiled-coil motif (LX6LX3LX6L) responsible for protein dimerization [8,9,10]. The variable C-terminal region of LBD confers transcriptional control of downstream gene expression [10]. Based on the conserved regions, most LBD genes belong to class-I, which is characterized by a complete leucine-zipper-like domain, while all members of class-II have an incomplete or no leucine zipper-like coiled-coil motif [8]. Several LBD proteins form homo-interactions and hetero-interactions, such as LBD10, LBD27, LBD18, and LBD33 in Arabidopsis [11,12], and RTCS (rootless concerning crown and seminal roots), RTCL (RTCS-like), IG1, and RS2 in maize [9,13]. According to whole-genome sequencing, Arabidopsis [8], rice [14], maize [15], barley [16], tomato [17], grape [18], Eucalyptus [19], and potato [20] have been identified as harboring 43, 35, 44, 24, 46, 49, 47, and 43 LBD genes, respectively, of which 7, 5, 7, 5, 6, 7, 8, and 8 are LBD class-II family members, respectively. There were significantly fewer LBD class-II members than LBD class-I members. The expression patterns of LBD genes were diverse, revealing the diversity of LBD function [8,14].

Most studies have revealed the function of class-I members, including organ development, plant regeneration, photomorphogenesis, and environmental cue responses. AtASL4 was first discovered to regulate leaf development in Arabidopsis [8]. AtASL4 interacts with AtAS1 to bind the cis-element of the KNAT1 promoter, inhibits the expression of KNAT1, and promotes the development of leaf primordia and inflorescence [21]. In maize, IG1 (indeterminate gametophyte1) interacts with RS (AtAS1 homolog) to regulate the development of female gametophytes and the number of tassel branches [13,22]. AtLBD16, OsCRL1, and ZmRTCS are involved in root development downstream of the auxin signal transduction pathway [9,23,24,25]. In trees, LBD genes also promote stem thickening by accelerating the cell division activity of vascular cambium cells during secondary growth [26,27,28]. In addition to participating in plant growth and development, LBD genes are involved in plants’ responses to external biotic and abiotic stresses [10]. In Arabidopsis, the root-specific LBD gene AtLBD20 inhibits the defense genes THI2 (thionin 2.1) and VSP2 (volatile storage protein 2) via COI1 (coronatine-insensitive 1)/MYC2-mediated jasmonic acid (JA) signaling, thereby preventing the damage of the root-invading fungal pathogen Fusarium oxysporum in plants. AtLBD14 regulates the branching of lateral roots through the ABA signaling pathway [29,30]. AtLBD15 directly binds to the promoter of AtABI4 (ABSCISIC ACID INSENSITIVE4) to activate its expression, resulting in stomatal closure, reduced water loss rate, and enhanced drought tolerance in AtLBD15-overexpressed plants [31]. In rice, OsLBD12-1 directly interacts with the OsAGO10 promoter to inhibit its expression, resulting in growth retardation, leaf distortion, anther abnormality, and SAM reduction, and LBD12-1 has a stronger effect on AGO10 under salt stress [32].

In contrast, reports about class-II members remain limited. The class-II LBD genes characterized thus far are mainly involved in metabolism, such as anthocyanin biosynthesis and nitrogen metabolism [33,34,35]. In this study, the role of ZmLBD5—a class-II member—in drought response was investigated. Overexpression of ZmLBD5 in Arabidopsis caused the drought-sensitive phenotype by suppressing ROS accumulation, increasing the stomatal aperture and water loss. Our results suggest that ZmLBD5 mediates the response of maize seedlings to drought by regulating H2O2 homeostasis, and is expected to be used in genetically modified crops.

2. Results

2.1. ZmLBD5 Was Induced by Osmotic Stress in Maize

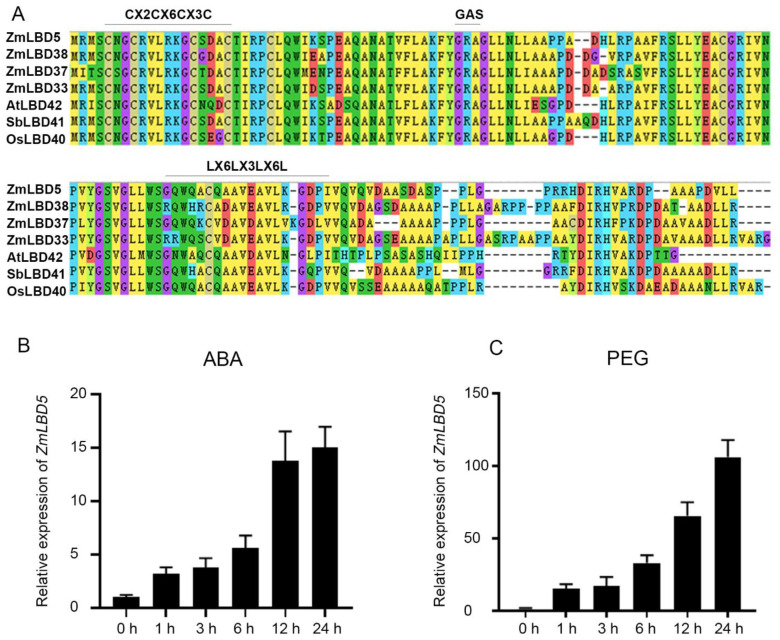

In the present study, we cloned the class-II LBD gene ZmLBD5 from inbred B73 maize. The full-length CDS of ZmLBD5 is 942 bp, and encodes a polypeptide of 313 amino acid residues with a predicted molecular mass of 33.96 kD and a pI value of 6.61. Sequence alignment revealed that ZmLBD5 contained a typical DNA-binding domain, CX2CX6CX3C, whereas the GAS block and LX6LX3LX6L coiled-coil motif were incomplete, allowing for a distinction between the class-I and class-II members of the LBD family (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Sequence and expression pattern analysis of ZmLBD5: (A) LOB domain sequence alignment of ZmLBD5 and LBD members from other plant species. The class-I LBD members had typical CX2CX6CX3C, GAS, and LX6LX3LX6L domains. The same position in class II is marked. (B,C) The expression of ZmLBD5 upon ABA and drought treatment in maize. Total RNA was isolated from 3-leaf seedlings grown without (0 h) or with 10 µM ABA and 20% PEG6000 treatment. Transcript levels of ZmLBD5 were determined by qPCR, using Zme1F1α and Zm18S as reference genes. Fold change was calculated by 2−∆∆t. All bars represent means ± SD (n = 3).

Given that gene expression levels are regulated by promoters, we examined the ZmLBD5 promoter region (approximately 2000 bp upstream of the first codon). Several stress-response-related cis-acting elements were present in the ZmLBD5 promoter, including seven ABREs (ABA-responsive elements), three DREs (dehydration-responsive elements), two LTREs (low-temperature-responsive elements), one MBS (MYB-binding site, involved in drought-inducibility), eight MYBRSs (MYB recognition sites), and other light-response elements (Table 1). Therefore, the response of ZmLBD5 to drought stress was investigated by RT-qPCR using drought- and ABA- treated maize plants. The results showed that the expression of ZmLBD5 was strongly induced by ABA and drought stress (Figure 1B,C). These results suggest that ZmLBD5 plays a prominent role in the response to drought stress in maize.

Table 1.

Cis-elements in the promoter region (~2 kb) of ZmLBD5.

| Site Name | Sequence | Position | Strand | Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABRE | ACGTG | −1984 | - | Abscisic acid responsiveness |

| ABRE | CGTACGTGCA | −1730 | - | Abscisic acid responsiveness |

| ABRE | CACGTG | −1596 | + | Abscisic acid responsiveness |

| ABRE | ACGTG | −1595 | + | Abscisic acid responsiveness |

| ABRE | ACGTG | −1528 | + | Abscisic acid responsiveness |

| ABRE | ACGTG | −71 | - | Abscisic acid responsiveness |

| ABRE | CCACGTGG | −1597 | + | Abscisic acid responsiveness |

| DRE | GCCGAC | −1896 | - | Dehydration-responsive element |

| DRE | GCCGAC | −1495 | - | Dehydration-responsive element |

| DRE | ACCGAGA | −38 | + | Dehydration-responsive element |

| LTR | CCGAAA | −1635 | + | Low-temperature responsiveness |

| LTR | CCGAAA | −262 | + | Low-temperature responsiveness |

| MBS | CAACTG | −597 | - | MYB-binding site involved in drought-inducibility |

| MYBRS | CAACCA | −1566 | - | MYB recognition site |

| MYBRS | CAACTG | −597 | - | MYB recognition site |

| MYBRS | TAACCA | −593 | - | MYB recognition site |

| MYBRS | CAACCA | −518 | + | MYB recognition site |

| MYBRS | CAACCA | −100 | + | MYB recognition site |

| MYBRS | CAACCA | −96 | + | MYB recognition site |

| MYBRS | CCGTTG | −1844 | + | MYB recognition site |

| MYBRS | TAACCA | −593 | - | MYB recognition site |

| CCAAT-box | CAACGG | −1844 | - | MYBHv1-binding site |

| ARE | AAACCA | −1631 | + | Anaerobic induction |

| ARE | AAACCA | −259 | + | Anaerobic induction |

| G-box | CACGTC | −1984 | + | Light responsiveness |

| G-box | GCCACGTGGA | −1598 | + | Light responsiveness |

| G-box | CACGTG | −1596 | + | Light responsiveness |

| G-Box | CACGTG | −1596 | + | Light responsiveness |

| G-Box | CACGTT | −1529 | - | Light responsiveness |

| G-box | CACGTC | −71 | + | Light responsiveness |

“+” represents sense strand, and “-” represents the antisense strand.

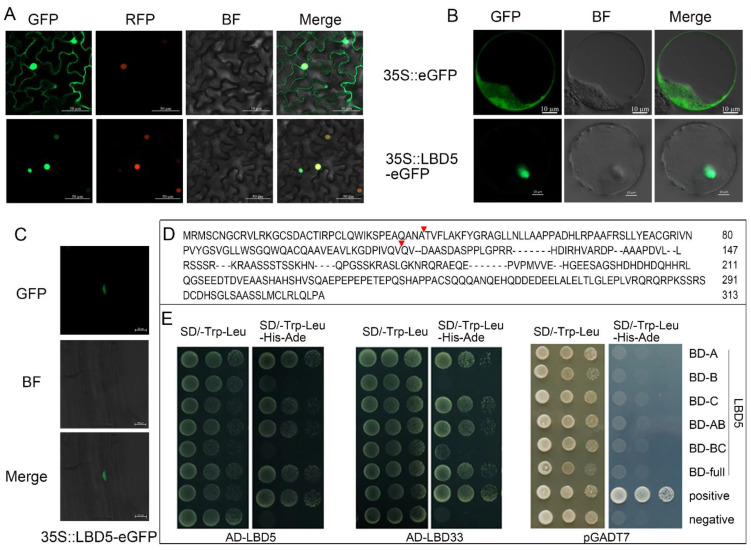

2.2. ZmLBD5 Is Localized in the Nucleus, and Could Form Dimers

Understanding the subcellular localization of gene expression products is important for the functional analysis of genes. To determine the subcellular localization of ZmLBD5, ZmLBD5-GFP was transiently expressed in tobacco leaf cells and maize protoplasts under the control of the cauliflower mosaic virus (CaMV) 35S promoter. The strong green fluorescence signal of GFP was mainly distributed in the nucleus and the cytoplasm, whereas the green fluorescence signal of ZmLBD5-GFP was observed in the nucleus, which completely overlapped with the red fluorescence signal of the nuclear localization signal (Figure 2A,B). In addition, GFP fluorescence was observed in the nuclei of the root cells in ZmLBD5-GFP-overexpressed Arabidopsis (Figure 2C).

Figure 2.

Subcellular localization and dimer-forming ability of ZmLBD5: (A–C) Subcellular localization of ZmLBD5 in tobacco leaves, maize protoplasts, and 35S::ZmLBD5-eGFP transgenic Arabidopsis, respectively (bar = 50, 10, and 20 μm, respectively). (D) Three fragments of ZmLBD5 (A–C) were divided and the red triangle indicated the position of truncation. (E) The ability of ZmLBD5 to form dimers in the yeast strain Y2H Gold. The Y2H Gold strains containing target plasmids were diluted and cultured on no-selection synthetic dropout (SD) media without tryptophan and leucine (SD/-T-L), or on selection SD media without tryptophan, leucine, histidine, and adenine (SD/-T-L-H-A). Photos were taken 3 days after inoculation for the plates. Fragments A, B, and C represent CX2CX6CX3C, GAS, and LX6LX3LX6L, and various C-terminal domains, respectively.

Given that the GAS block and LX6LX3LX6L coiled-coil motif of class-I members are essential for protein dimerization, and class-II members are characterized by a lack of or an incomplete domain, the ability of ZmLBD5 to dimerize was tested. The full length of ZmLBD5 and its five truncated peptide fragments (A, B, C, AB, and BC) were tested for the interaction with ZmLBD5 itself and another LBD member, ZmLBD33. Fragments A, B, and C represent the N-terminal C-block (CX2CX6CX3C), the GAS and LX6LX3LX6L coiled-coil motifs, and the C-terminal domain, respectively (Figure 2D). Although it was difficult to determine the essential region for the interaction, homo- and heterodimerization were clearly detected through yeast two-hybrid screening (Figure 2E).

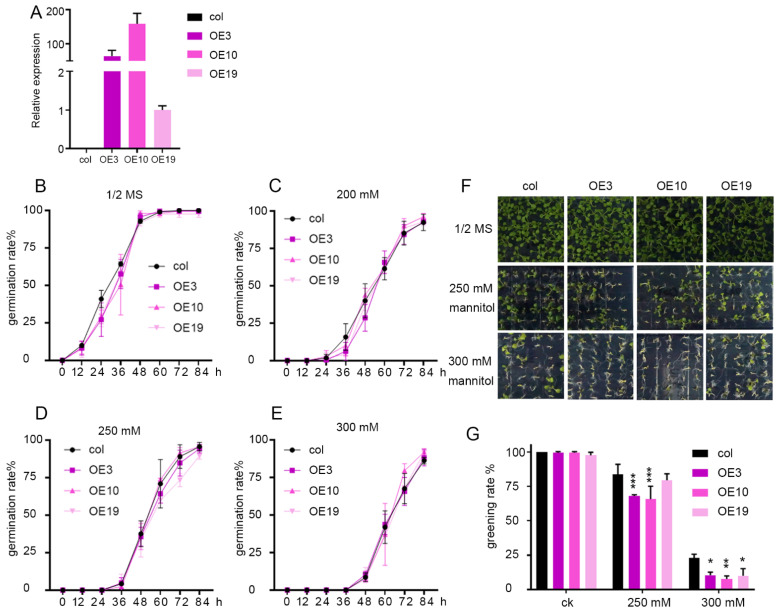

2.3. Overexpression of ZmLBD5 Decreased Drought Tolerance in Transgenic Arabidopsis

ZmLBD5 was overexpressed in Arabidopsis to observe its function. Eleven transgenic lines were generated, and the three homozygous lines with the highest expression levels (OE3, OE10, and OE19) were selected for subsequent experiments (Figure 3A). Transgenic lines and the wild-type seeds were exposed to different concentrations of mannitol (0, 200, 250, and 300 mM). The germination rates of ZmLBD5-overexpressed plants were comparable to that of the wild type, and it was significantly delayed along with the increase in mannitol concentration (Figure 3B–E). The cotyledon greening rate of the overexpressed lines was significantly lower than that of the wild type under 250 mM and 300 mM mannitol stresses 3 days after germination (Figure 3F,G).

Figure 3.

The germination and greening rate of ZmLBD5 transgenic Arabidopsis with mannitol treatment: (A) RT-qPCR analysis of ZmLBD5 expression in the overexpression lines and wild type. (B–E) Statistical analysis of ZmLBD5 transgenic lines’ and wild-type’s seed germination rates under 0 mM, 200 mM, 250 mM, and 300 mM mannitol, respectively. (F) The phenotypes of ZmLBD5 transgenic and wild-type Arabidopsis lines treated with 0 mM, 250 mM, and 300 mM mannitol. (G) Greening rate of ZmLBD5 transgenic and wild-type Arabidopsis under 0 mM, 250 mM, and 300 mM mannitol stress. Significance was calculated by one-way ANOVA. * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001. All bars represent means ± SD, (n ≥ 3).

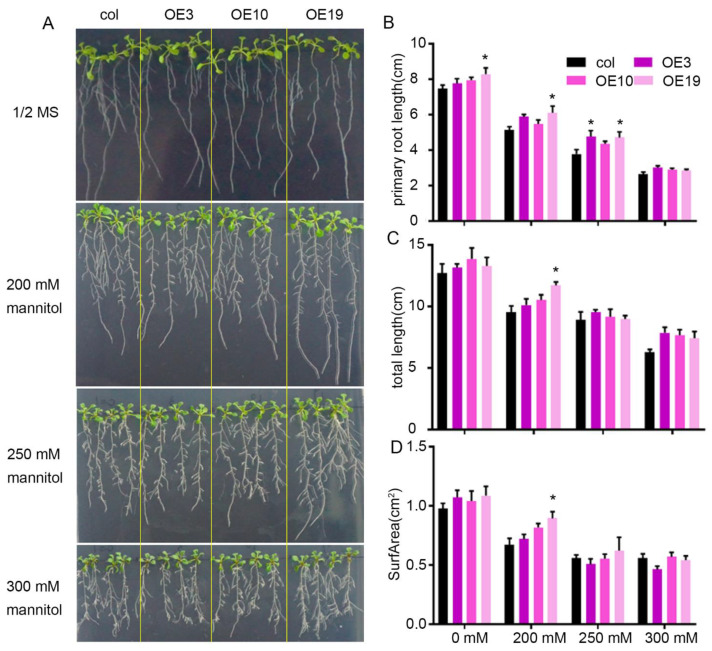

To further characterize the responses of the wild-type and ZmLBD5-overexpressed plants to osmotic stress, 5-day-old seedlings were exposed to different concentrations of mannitol (0, 200, 250, and 300 mM) for 7 days. Unexpectedly, there was no significant difference between the wild-type and the transgenic seedlings, except for line OE19 (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The phenotype of ZmLBD5 transgenic Arabidopsis with mannitol treatment: (A) Seedlings of wild-type and ZmLBD5 transgenic lines grown on 1/2 MS medium with 0 mM, 200 mM, 250 mM, and 300 mM mannitol. (B–D) Statistical analysis of primary root length, total root length, and root surface area of wild-type and ZmLBD5 transgenic seedlings grown on 1/2 MS medium with or without mannitol treatment. Mean values and standard errors (bars) are shown from 12 independent seedlings. Asterisks on bar represent the difference compared with wild type is significant (* p < 0.05).

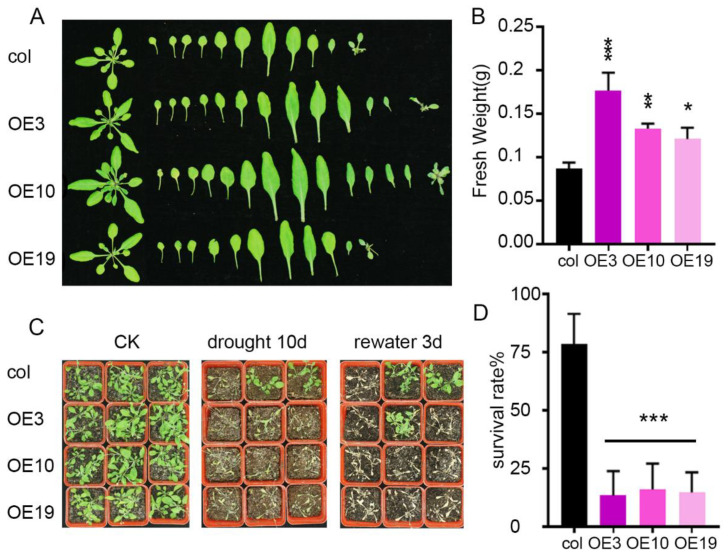

To further understand the role of ZmLBD5 under drought stress, 7-day-old plants were transplanted into the soil and grown for one month. Then, plants were exposed to drought stress for 10 days. Three days after rewatering, ZmLBD5-overexpressed plants displayed a higher survival rate than that of the wild type (Figure 5C,D). Under well-watered conditions, the rosette leaf areas of ZmLBD5-overexpressed Arabidopsis were significantly larger than those of the wild type (Figure 5A), and the fresh weight increased in ZmLBD5-overexpressed seedlings (Figure 5B). These results indicated that ZmLBD5 promotes seedling growth under normal conditions, and increases drought sensitivity under drought stress.

Figure 5.

Phenotype and survival rate of ZmLBD5 transgenic seedlings under normal or drought conditions in soil: (A,B) Phenotype and fresh weight of ZmLBD5 transgenic seedlings under normal conditions in soil. (C,D) Survival rate of ZmLBD5 transgenic seedlings under drought conditions in soil. Significance was analyzed by one-way ANOVA. * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001. All bars represent means ± SD (n ≥ 12).

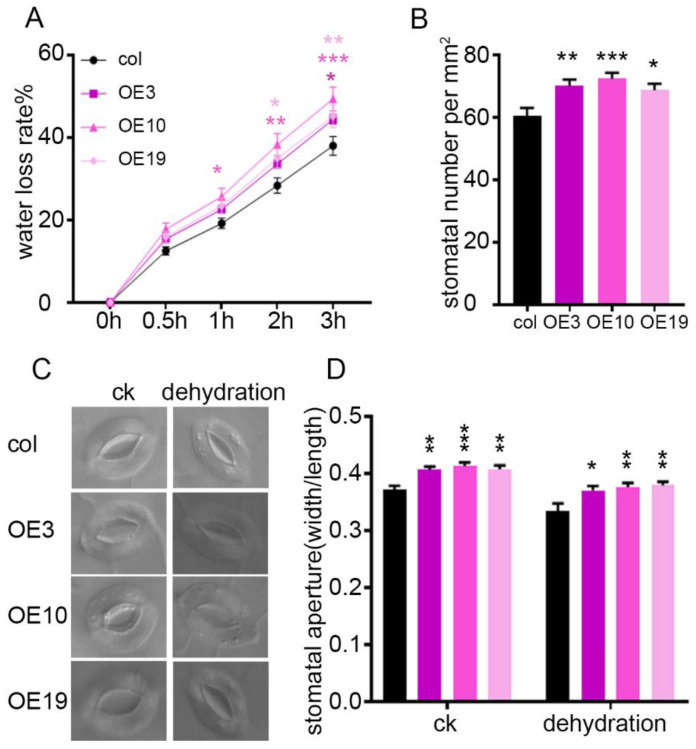

2.4. ZmLBD5 Increased the Water Loss Rate by Enhancing the Stomatal Density and Aperture

We measured the rate of water loss from detached leaves to investigate why ZmLBD5-overexpressed seedlings displayed drought sensitivity. The results showed that detached leaves of ZmLBD5 transgenic seedlings lost water at a greater rate than that of the wild-type plants after 1 h of dehydration (Figure 6A), indicating that ZmLBD5-overexpressed seedlings ran out of soil water more rapidly than the wild-type seedlings, leading to earlier wilting. Given that water evaporated mainly through the stomata, the stomatal number and apertures on abaxial leaves were analyzed. The stomatal number and stomatal aperture of ZmLBD5-overexpressed plants were both greater than those of the wild-type plants (Figure 6B–D). Thus, the overexpression of ZmLBD5 enhanced drought sensitivity by increasing the stomatal number and apertures in Arabidopsis under drought conditions.

Figure 6.

Water loss rate, stomatal number, and apertures of leaves in ZmLBD5 transgenic seedlings: (A) Water loss rate of leaves in ZmLBD5 transgenic seedlings. (B) Stomatal number of the fourth leaves in ZmLBD5 transgenic seedlings. Each sample had at least 12 seedlings. (C,D) Stomatal aperture of fourth leaves after detachment for 1 h in ZmLBD5 transgenic seedlings (n > 30 for each sample). Significance was analyzed by one-way ANOVA. * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001. All bars represent means ± SD (n ≥ 12).

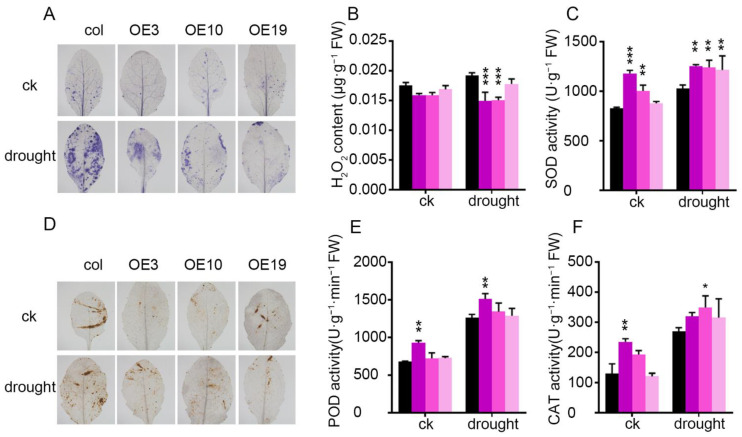

2.5. Overexpression of ZmLBD5 Improved Antioxidant Enzyme Activity and Blocked ROS Accumulation in Arabidopsis

ROS are important molecular signaling and cytotoxic substances in plants’ response to drought stress. The accumulation of H2O2 is important for stomatal closure [4,5,36]. Therefore, H2O2 and superoxide anions were investigated using DAB and NBT staining, and H2O2 content was quantitatively measured by the potassium iodide method. The accumulation of H2O2 and superoxide anions in the leaves of ZmLBD5-overexpressed seedlings was significantly lower than that of the wild-type seedlings (Figure 7A,B,D). Many antioxidant enzymes—such as POD, SOD, and catalase (CAT)—are associated with ROS levels and the tolerance of plants to abiotic stress [3,37]. SOD activity was higher in ZmLBD5-overexpressed seedlings than that of the wild-type seedlings under both normal and drought conditions (Figure 7C). The activities of POD and CAT were not different between the wild-type plants and the transgenic plants, except for OE3 (Figure 7E,F).

Figure 7.

Reactive oxygen species staining and physiological indices in ZmLBD5 transgenic Arabidopsis: (A,D) NBT and DAB staining of leaves for H2O2 from ZmLBD5 transgenic seedlings and wild-type plants under normal conditions and drought stress (3-week-old seedlings were subjected to drought for 7 days). (B) H2O2 content in leaves from ZmLBD5 transgenic seedlings and wild-type plants under normal conditions and drought stress (withholding water for 7 days). (C) SOD activity, (E) POD activity, and (F) CAT activity in leaves from ZmLBD5 transgenic seedlings and wild-type plants under normal and drought conditions (withholding water for 7 days). Significance was analyzed by one-way ANOVA. * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001. All bars represent means ± SD (n = 6).

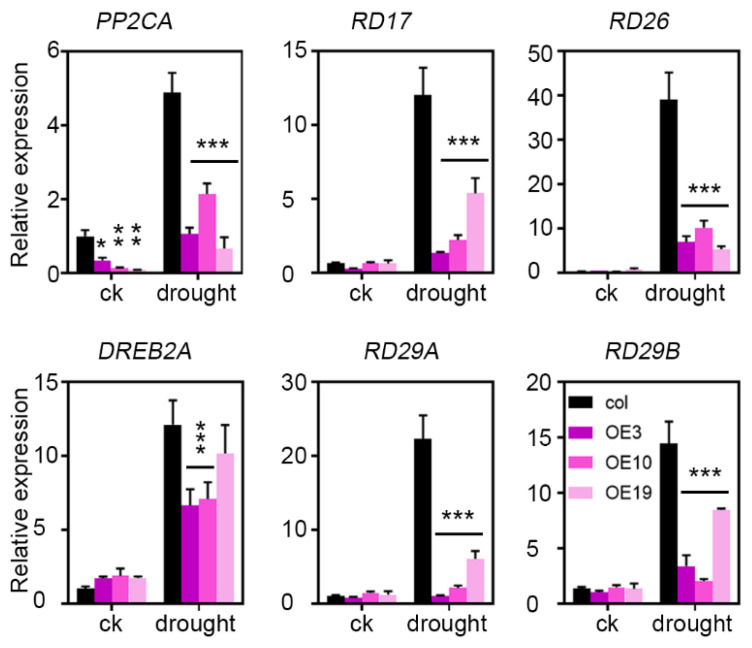

2.6. ZmLBD5 Negatively Regulates Drought-Related Genes’ Expression in Transgenic Arabidopsis

From the above findings, ZmLBD5 is a negative regulator of plant in drought tolerance. Therefore, we analyzed the expression of several widely reported drought-related genes (PP2CA, RD17, RD26, DREB2A, RD29A, and RD29B) in ZmLBD5-overexpressed plants and wild-type plants. Under normal conditions, the expression levels of these genes were similar between the transgenic plants and the wild-type plants, except for PP2CA (Figure 8). Under drought conditions, the expression levels of these tested genes were remarkably increased in both the transgenic plants and the wild-type plants. However, the expression levels were lower in the transgenic plants than those in the wild-type plants (Figure 8), indicating that ZmLBD5 suppressed drought-related genes’ expression under drought stress.

Figure 8.

Expression levels of drought-stress-related genes in ZmLBD5 transgenic Arabidopsis: Total RNA was isolated from 15-day-old seedlings grown without (CK) or with 250 mM mannitol treatment for 7 days. Transcript levels of PP2CA, RD17, RD26, DREB2A, RD29A, and RD29B in the transgenic lines and wild type were determined by qPCR, using AtACTIN8 and AtUBQ10 as reference genes. Fold change was calculated by 2−∆∆t. Significance was analyzed by one-way ANOVA. * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001. All bars represent means ± SD (n = 3).

3. Discussion

The LBD genes are plant-specific transcription factors. According to their GAS and leucine zipper domains, LBD genes are divided into class-I and class-II members. With the publication of genomic data on different species, the distribution, gene structure, and expression pattern of the LBD gene family involved in plants’ development and stress response have been displayed [14,15,38,39,40]. Most class-I LBD genes are involved in root growth, leaf extension, pollen development, plant regeneration, photomorphogenesis, pathogen response, and secondary cell wall development [10,33,35]. However, studies of class-II members are scarce, and these are involved in anthocyanin synthesis, nitrogen metabolism, root development, auxin response, and GA response [33,34,41,42]. In this study, ZmLBD5 was reported to negatively regulate drought tolerance by decreasing ROS levels and suppressing stomatal closure.

LBD proteins generally function by forming homodimers or heterodimers with themselves or other proteins [43]. In Arabidopsis, the dimerization of AtLBD16 and AtLBD18 is critical for lateral root formation [44]. AtLBD10 interacts with AtLBD27 to regulate pollen development [11]. In maize, RTCS and RTCL form heterodimers to affect the initial crown root generation [9]. The difference between class-I and class-II LBD proteins is in the GAS and leucine zipper domains, which are proposed to be necessary for protein–protein dimerization [10,35]. In this study, ZmLBD5, without the complete GAS and leucine zipper domains, could form homodimers and heterodimers in the same way as class-I members, implying that the GAS and leucine zipper domains may be not essential for dimerization.

Previous studies have shown that the functions of the class-I LBDs are mainly related to organ determination, including embryo, root, leaf, and inflorescence development [13,45,46,47]. In Arabidopsis, AtASL4 is expressed at the boundary between the developing leaf primordia and the shoot-tip meristem to regulate leaf development [45]. AtAS2 (At LBD6) represses cell proliferation in the adaxial domain, and is critical for the development of properly expanded leaves [46,47]. IG1, an LBD gene, affects the formation of the leaf’s ligular region by inhibiting the expression of KNOX while also inhibiting the development of female gametophytes in ig1 mutants, and limiting the number of male ear branches in maize [13]. In addition, the class-I member AtLBD15 promotes drought tolerance by increasing stomatal closure and reducing the water loss rate [31]. OsLBD12-1 reduces SAM size by directly binding to the promoter region, and strongly represses the expression of AGO10 under salt conditions [32]. ZmLBD5, a class-II LBD gene, also regulates organ development and response to drought stress in transgenic Arabidopsis, indicating the functional overlap between class-I and class-II members. The function of ZmLBD5 is similar to that of the class-I members of the LBD gene family, thereby portraying substantial evidence for the study of class-II members in plant growth and the regulation of drought.

Drought stress brings about the production of ROS. The excessive accumulation of ROS causes damage to plant cells; however, they also act as signaling molecules that participate in the regulation of stomatal number and apertures. Therefore, ROS have been widely reported to regulate drought tolerance in various studies [5,6,7,48]. Many studies have shown that ABA stimulates the production of H2O2 through NADPH oxidase in guard cells, and H2O2 is an important signaling molecule that activates calcium channels in the plasma membrane, thereby mediating ABA-induced stomatal closure [36,49,50]. In rice, H2O2 accumulated in guard cells in dst (drought- and salt-tolerant transcription factor) mutants was able to promote stomatal closure, reduce water loss, and improve drought and salt tolerance. DST also inhibited stomatal closure by directly regulating the expression of the H2O2 homeostasis-related gene peroxidase 24 predictor [5,48]. In this study, the activities of SOD and POD were remarkably higher, and the ROS level was significantly lower in ZmLBD5-overexpressed Arabidopsis than that in the wild type. This indicates that ZmLBD5 regulates the response of the seedlings to drought through the regulation of H2O2 signal molecules on the stomatal aperture—not the antioxidant pathway. Accordingly, ZmLBD5 overexpression increased water loss rate by suppressing stomatal closure, and resulted in the drought-sensitive phenotype.

4. Conclusions

In summary, this study demonstrated ZmLBD5 as a negative regulator of drought tolerance. Overexpression of ZmLBD5 increased the stomatal aperture and water loss rate by suppressing ROS accumulation. Furthermore, the enhancement of SOD and POD activities in ZmLBD5-overexpressed Arabidopsis revealed the role of ZmLBD5 in drought stress by regulating ROS levels. The study of ZmLBD5 promoted our understanding of the function of the class-II LBD genes in maize.

5. Materials and Methods

5.1. Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

ZmLBD5 transgenic lines and wild-type (ecotype: Col-0) seeds were surface-sterilized with 3% NaClO3 for 8 min, and washed five times with sterile water. The sterilized Arabidopsis seeds were plated on half of the Murashige and Skoog (1/2 MS) medium and stored at 4 °C for 72 h in darkness. Then, they were transferred into a growth incubator (22 °C, 16 h light/8 h dark) for germination and growth. Seven days later, the seedlings were transplanted into soil and grown in a greenhouse (22 °C, 16 h light/8 h dark). Tissues were harvested from the seedlings for further study.

For drought stress and ABA treatment, two-leaf-stage seedlings were transferred to Hoagland nutrient solution in a greenhouse with a 14 h light/10 h dark photoperiod at 28 °C, and grown to the three-leaf stage. Then, seedlings were subjected to polyethylene glycol 6000 (PEG6000) (20% w/v) and ABA (10 μM). The roots were collected after 0, 1, 3, 6, 12, and 24 h of treatment. The harvested samples were frozen immediately in liquid nitrogen and used for RNA isolation.

5.2. Sequence Analysis

The ZmLBD5 cDNA was obtained from MaizeGDB (https://www.maizegdb.org/) (accessed on 16 February 2022). Homologous sequences of ZmLBD5 were retrieved from the Phytozome database (https://phytozome-next.jgi.doe.gov/) (accessed on 16 February 2022), and sequence alignment was performed using ClustalX. Plant CARE (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/plantcare/html/) (accessed on 1 March 2022) was used to analyze the promoter sequences of different abiotic-stress-related cis-elements.

5.3. Subcellular Localization

The full-length CDS of ZmLBD5 was inserted into the binary vector pCAMBIA2300-eGFP to generate the pCAMBIA2300-ZmLBD5-eGFP vector. The constructed vector was introduced into Arabidopsis and tobacco leaves using agrobacterium-mediated methods. In addition, the plasmid was transformed into maize protoplasts via PEG-mediated methods. GFP fluorescence was investigated using a laser confocal microscope (LSM800, Zeiss, Germany). The primers used here are listed in Supplementary Table S1.

5.4. RNA Extraction and Quantitative RT-qPCR Analysis

Total RNA was extracted from Arabidopsis or maize (inbred line: B73) seedlings according to the manufacturer’s protocol of the Plant Total RNA Isolation Kit (FOREGENE, Re-05014), and treated with DNase I (Trans, GD201-01) at 37 °C for 30 min to eliminate genomic DNA contamination. The PrimeScript RT reagent kit with a gDNA eraser (Takara, RR047A) was used to synthesize first-strand cDNA as real-time PCR templates with gene-specific primers. Furthermore, we performed qPCR amplification on a Bio-Rad CFX96 PCR instrument according to the SYBR Green Fast qPCR Mix Kit instructions (ABclonal, RM21203). AtACTIN8 and AtUBQ10 were used as internal reference genes for Arabidopsis. ZmeF1α and Zm18S were used as internal reference genes for maize. The mean values and standard deviations were estimated using 2−∆∆CT from the data of three biological experiments. All of the primers used in the experiments are listed in Supplementary Table S1.

5.5. Generation of Transgenic Plants and Phenotypic Analysis

The coding sequence of ZmLBD5 was cloned into the pCAMBIA2300-eGFP vector to generate the 35S::ZmLBD5-eGFP vector. The product was introduced into the wild-type Col-0 using the agrobacterium-mediated floral-dip method. Homozygous plants were screened under 10 µg/mL neomycin (G418) conditions, and three high-expression lines were used for further study. All of the primers used in the experiments are listed in Supplementary Table S1.

Seeds were sterilized and sowed on 1/2 MS medium containing 0 mM, 200 mM, 250 mM, and 300 mM mannitol and grown in a greenhouse. Germination rates were recorded every 12 h. Seeds were recorded as germinated when the radicles protruded from the seed coat. After germination for 5 d, the greening rate of the seedlings was recorded. Each sample contained three biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed with one-way ANOVA, and the mean value each transgenic line was compared with the wild type.

Five-day-old seedlings vertically grew on 1/2 MS medium containing 0 mM, 200 mM, 250 mM, and 300 mM mannitol for one week. Primary root length was measured using ImageJ software. Root lengths and surface areas were collected and analyzed using an Epson 11,000 × l root scanner and WinRHIZO pro2013. All experiments were performed in triplicate. Each biological replicate contained at least 12 seedlings.

Seven-day-old plants were transplanted into the soil under short-day conditions to grow for three weeks. Subsequently, water was withheld for approximately 10 days, and photographs were taken. After re-watering for 3 days, the survival rates were investigated.

5.6. Water Loss Measurement

To assay the water loss rate, 12 one-month-old seedlings of each sample were detached on the laboratory bench and weighed at different time points. The experiment was replicated three times. ANOVA was used to assess the differences between the wild-type and transgenic plants.

5.7. Stomatal Density and Stomatal Aperture

The fourth expanded rosette leaves of Arabidopsis were detached on a laboratory bench for one hour. Leaves were placed into the Carnot fixed solution (absolute ethanol: glacial acetic acid = 3:1) for 24 h, followed by dehydration with 30%, 50%, 70%, 80%, 85%, 90%, 95%, and 100% alcohol for 30 min, dehydration with 100% alcohol again, and placement into a transparent solution (trichloroacetaldehyde: water: glycerol = 8:3:1). Stomatal apertures were observed under microscopes, and the ratio of the stomatal length to width was recorded using ImageJ software. At least 30 stomata of each sample per replicate were measured, and three replicates were performed.

5.8. ROS Measurements

Histochemical assays for reactive oxygen species (ROS) accumulation were performed using DAB and NBT staining. The detached leaves of Arabidopsis seedlings were treated with DAB staining solution (0.1 g/mL DAB, PH 3.8) through a vacuum pump for 30 min, and placed in the dark at room temperature for 10 h, soaked in decolorizing solution (acetic acid: glycerol: ethanol = 1:1:3) in 95 °C boiling water for 5 min, stored in 95% ethanol, and observed under a stereomicroscope. Superoxide anion accumulation was detected using NBT staining. The detached leaves of Arabidopsis were immediately immersed in 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.5) containing 0.1 g/mL NBT at room temperature for 8 h in the dark. The decolorization method was similar to that of DAB staining. Each line contained at least 10 different seedlings, and representative images are shown.

Quantitative measurement of H2O2 concentration was performed using the potassium iodide method [51]. Briefly, 100 mg leaf samples were placed in liquid nitrogen and ground into powder. Furthermore, 1 mL of precooled 0.1% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) solution was immediately added and mixed with the samples. After centrifugation (10,000× g, 4 °C, 10 min), equal volumes of PBS buffer were added to the 500 µL supernatant, and then 1 mL of 1 M potassium iodide solution was added, and the mixture was shaken with 150 rpm at 30 °C for 1 h. Absorbance was measured at 390 nm. In addition, 300 µmol/L H2O2 was used to obtain a standard curve. Each experiment was performed in six replicates.

The activities of antioxidant enzymes (SOD, POD, and CAT) were measured following the aforementioned protocols [52,53,54]. The units of the antioxidant enzyme activities were defined as follows: a unit of SOD activity is the quantity of enzyme required to cause 50% inhibition of the photochemical reduction of NBT per minute at 560 nm [54]; a unit of POD activity is the amount of enzyme required to cause a 0.01 increase in the absorbance of H2O2 per minute at 470 nm [52,53]; and a unit of CAT activity is the amount of enzyme required to cause a 0.01 decrease in the absorbance per minute at 240 nm [53].

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/plants11101382/s1, Table S1: The primers of RT-PCR and vector construction.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.F. and Y.L.; Methodology, J.X. (Jing Xiong), W.Z., D.Z. and H.X.; Data Curation, J.X. (Jing Xiong), W.Z. and X.Z.; Writing—original draft preparation, J.X. (Jing Xiong) and X.F.; Writing—review and editing, Q.W., F.W., J.X. (Jie Xu) and Y.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding Statement

This research was funded by the key Research Program of the Department of Science and Technology of Sichuan province, China (2021YFH0053, 2020YFH0116), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31901557, 32072074).

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Blum A. Drought resistance, water-use efficiency, and yield potential—are they compatible, dissonant, or mutually exclusive? Aust. J. Agric. Res. 2005;56:1159–1168. doi: 10.1071/AR05069. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Apel K., Hirt H. Reactive oxygen species: Metabolism, oxidative stress, and signal transduction. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2004;55:373–399. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.55.031903.141701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miller G., Suzuki N., Ciftci-Yilmaz S., Mittler R. Reactive oxygen species homeostasis and signalling during drought and salinity stresses. Plant Cell Environ. 2010;33:453–467. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2009.02041.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marino D., Dunand C., Puppo A., Pauly N. A burst of plant NADPH oxidases. Trends Plant Sci. 2012;17:9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li J., Li Y., Yin Z., Jiang J., Zhang M., Guo X., Ye Z., Zhao Y., Xiong H., Zhang Z., et al. OsASR5 enhances drought tolerance through a stomatal closure pathway associated with ABA and H2O2 signalling in rice. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2017;15:183–196. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang L., Jake F., Hui W., Xinzhi N., Pingsheng J., Robert L., Robert K., Brian S., Baozhu G. Stress sensitivity is associated with differential accumulation of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species in maize genotypes with contrasting levels of drought tolerance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015;16:24791–24819. doi: 10.3390/ijms161024791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xiong H., Yu J., Miao J., Li J., Zhang H., Wang X., Liu P., Zhao Y., Jiang C., Yin Z., et al. Natural variation in OsLG3 increases drought tolerance in rice by inducing ROS scavenging. Plant Physiol. 2018;178:451–467. doi: 10.1104/pp.17.01492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shuai B., Reynaga-Peña C.G., Springer P.S. The lateral organ boundaries gene defines a novel, plant-specific gene family. Plant Physiol. 2002;129:747–761. doi: 10.1104/pp.010926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Majer C., Xu C., Berendzen K.W., Hochholdinger F. Molecular interactions of rootless concerning crown and semial roots, a LOB domain protein regulating shoot-borne root initiation in maize (Zea mays L.) Philosphical Trans. Rayal Soc. B. 2012;367:1542–1551. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2011.0238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xu C., Luo F., Hochholdinger F. LOB domain proteins: Beyond lateral organ boundaries. Trends Plant Sci. 2016;21:159–167. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2015.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim M.J., Kim M., Lee M.R., Park S.K., Kim J. Lateral organ boundaries domain (LBD) 10 interacts with sidecar pollen/LBD27 to control pollen development in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2015;81:794–809. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berckmans B., Vassileva V., Schmid S.P.C., Maes S., Veylder L.D. Auxin-dependent cell cycle reactivation through transcriptional regulation of Arabidopsis E2Fa by lateral organ boundary proteins. Plant Cell. 2011;23:3671–3683. doi: 10.1105/tpc.111.088377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Evans M.M.S. The indeterminate gametophyte1 gene of maize encodes a LOB domain protein required for embryo Sac and leaf development. Plant Cell. 2007;19:46–62. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.047506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang Y., Yu X., Wu P. Comparison and evolution analysis of two rice subspecies lateral organ boundaries domain gene family and their evolutionary characterization from Arabidopsis. Mol. Phylogenetics Evol. 2006;39:248–262. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2005.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang Y.M., Zhang S.Z., Zheng C.C. Genomewide analysis of lateral organ boundaries domain gene family in zea mays. J. Genet. 2014;93:79–91. doi: 10.1007/s12041-014-0342-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guo B.J., Wang J., Lin S., Tian Z., Zhou K., Luan H.Y., Lyu C., Zhang X.Z., Xu R.G. A genome-wide analysis of the asymmetric leaves2/lateral organ boundaries(AS2/LOB) gene family in barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) Biomed. Biotechnol. 2016;17:763–774. doi: 10.1631/jzus.B1500277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gupta K., Gupta S. Molecular and in silico characterization of tomato LBD transcription factors reveals their role in fruit development and stress responses. Plant Gene. 2021;27:100309. doi: 10.1016/j.plgene.2021.100309. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grimplet J., Pimentel D., Agudelo-Romero P., Martinez-Zapater J.M., Fortes A.M. The lateral organ boundaries domain gene family in grapevine: Genome-wide characterization and expression analyses during developmental processes and stress responses. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:15968. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-16240-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lu Q., Shao F., Macmillan C., Wilson I.W., van der Merwe K., Hussey S.G., Myburg A.A., Dong X., Qiu D. Genomewide analysis of the lateral organ boundaries domain gene family in Eucalyptus grandis reveals members that differentially impact secondary growth. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2018;16:124–136. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu H., Cao M., Chen X., Ye M., Zhao P., Nan Y., Li W., Zhang C., Kong L., Kong N., et al. Genome-wide analysis of the lateral organ boundaries domain (LBD) gene family in Solanum tuberosum. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019;20:5360. doi: 10.3390/ijms20215360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guo M., Thomas J., Collins G., Timmermans M.C.P. Direct repression of KNOX loci by the asymmetric leaves1 complex of Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2008;20:48–58. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.056127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bortiri E., Chuck G., Vollbrecht E., Rocheford T., Martienssen R., Hake S. ramosa2 encodes a lateral organ boundary domain protein that determines the fate of stem cells in branch meristems of maize. Plant Cell. 2006;18:574–585. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.039032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taramino G., Sauer M., Stauffer J.L., Jr., Multani D., Niu X., Sakai H., Hochholdinger F. The maize (Zea mays L.) RTCS gene encodes a LOB domain protein that is a key regulator of embryonic seminal and post-embryonic shoot-borne root initiation. Plant J. 2007;50:649–659. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03075.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Inukai Y., Sakamoto T., Ueguchi-Tanaka M., Shibata Y., Gomi K., Umemura I., Hasegawa Y., Ashikari M., Kitano H., Matsuoka M. Crown rootless1, which is essential for crown root formation in rice, is a target of an auxin response factor in auxin signaling. Plant Cell. 2005;17:1387–1396. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.030981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goh T., Toyokura K., Yamaguchi N., Okamoto Y., Uehara T., Kaneko S., Takebayashi Y., Kasahara H., Ikeyama Y., Okushima Y., et al. Lateral root initiation requires the sequential induction of transcription factors LBD16 and PUCHI in Arabidopsis thaliana. New Phytol. 2019;224:749–760. doi: 10.1111/nph.16065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ye L., Wang X., Lyu M., Siligato R., Eswaran G., Vainio L., Blomster T., Zhang J., Mähönen A.P. Cytokinins initiate secondary growth in the Arabidopsis root through a set of LBD genes. Curr. Biol. 2021;31:3365–3373.e3367. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2021.05.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bdeir R., Busov V., Yordanov Y., Gailing O. Gene dosage effects and signatures of purifying selection in lateral organ boundaries domain (LBD) genes LBD1 and LBD18. Plant Syst. Evol. 2016;302:433–445. doi: 10.1007/s00606-015-1272-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yordanov Y.S., Busov V. Boundary genes in regulation and evolution of secondary growth. Plant Signal Behav. 2011;6:688–690. doi: 10.4161/psb.6.5.14973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jeon E., Young Kang N., Cho C., Joon Seo P., Chung Suh M., Kim J. LBD14/ASL17 positively regulates lateral root formation and is involved in ABA response for root architecture in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Physiol. 2017;58:2190–2201. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcx153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jeon B.W., Kim J. Role of LBD14 during ABA-mediated control of root system architecture in Arabidopsis. Plant Signal Behav. 2018;13:e1507405. doi: 10.1080/15592324.2018.1507405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guo Z., Xu H., Lei Q., Du J., Li C., Wang C., Yang Y., Yang Y., Sun X. The Arabidopsis transcription factor LBD15 mediates ABA signaling and tolerance of water-deficit stress by regulating ABI4 expression. Plant J. 2020;104:510–521. doi: 10.1111/tpj.14942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ma W., Wu F., Sheng P., Wang X., Zhang Z., Zhou K., Zhang H., Hu J., Lin Q., Cheng Z., et al. The LBD12-1 transcription factor suppresses apical meristem size by repressing argonaute 10 expression. Plant Physiol. 2017;173:801–811. doi: 10.1104/pp.16.01699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rubin G., Tohge T., Matsuda F., Saito K., Scheible W.R. Members of the LBD family of transcription factors repress anthocyanin synthesis and affect additional nitrogen responses in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2009;21:3567–3584. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.067041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Albinsky D., Kusano M., Higuchi M., Hayashi N., Kobayashi M., Fukushima A., Mori M., Ichikawa T., Matsui K., Kuroda H., et al. Metabolomic screening applied to rice FOX Arabidopsis lines leads to the identification of a gene-changing nitrogen metabolism. Mol. Plant. 2010;3:125–142. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssp069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Majer C., Hochholdinger F. Defining the boundaries: Structure and function of LOB domain proteins. Trends Plant Sci. 2011;16:47–52. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2010.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang P., Song C.P. Guard-cell signalling for hydrogen peroxide and abscisic acid. New Phytol. 2008;178:703–718. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02431.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miller G. Reactive oxygen signaling and abiotic stress. Physiol. Plant. 2008;133:481–489. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.2008.01090.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang Y., Li Z., Ma B., Hou Q., Wan X. Phylogeny and functions of LOB domain proteins in plants. Intern. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21:2278. doi: 10.3390/ijms21072278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang X., He Y., He W., Su H., Wang Y., Hong G., Xu P. Structural and functional insights into the LBD family involved in abiotic stress and flavonoid synthases in Camellia sinensis. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:15651. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-52027-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xu J., Hu P., Tao Y., Song P., Gao H., Guan Y. Genome-wide identification and characterization of the Lateral Organ Boundaries Domain (LBD) gene family in polyploid wheat and related species. PeerJ. 2021;9:e11811. doi: 10.7717/peerj.11811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zentella R., Zhang Z.L., Park M., Thomas S.G., Endo A., Murase K., Fleet C.M., Jikumaru Y., Nambara E., Kamiya Y., et al. Global analysis of della direct targets in early gibberellin signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2007;19:3037–3057. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.054999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ariel F., Diet A., Verdenaud M., Gruber V., Frugier F., Chan R., Crespi M. Environmental regulation of lateral root emergence in Medicago truncatula requires the HD-Zip I transcription factor HB1. Plant Cell. 2010;22:2171–2183. doi: 10.1105/tpc.110.074823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee H.W., Kim M.J., Park M.Y., Han K.H., Kim J. The conserved proline residue in the LOB domain of LBD18 is critical for DNA-binding and biological function. Mol. Plant. 2013;6:1722–1725. doi: 10.1093/mp/sst037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee H.W., Kang N.Y., Pandey S.K., Cho C., Lee S.H., Kim J. Dimerization in LBD16 and LBD18 transcription factors is critical for lateral root formation. Plant Physiol. 2017;174:301–311. doi: 10.1104/pp.17.00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thatcher L.F., Kazan K., Manners J.M. Lateral organ boundaries domain transcription factors: New roles in plant defense. Plant Signal. Behav. 2012;7:1702–1704. doi: 10.4161/psb.22097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Semiarti E., Ueno Y., Tsukaya H., Iwakawa H., Machida C., Machida Y. The ASYMMETRIC LEAVES2 gene of Arabidopsis thaliana regulates formation of a symmetric lamina, establishment of venation and repression of meristem-related homeobox genes in leaves. Development. 2001;128:1771–1783. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.10.1771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Iwakawa H., Iwasaki M., Kojima S., Ueno Y., Soma T., Tanaka H., Semiarti E., Machida Y., Machida C. Expression of the ASYMMETRIC LEAVES2 gene in the adaxial domain of Arabidopsis leaves represses cell proliferation in this domain and is critical for the development of properly expanded leaves. Plant J. 2007;51:173–184. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03132.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Huang X.Y., Chao D.Y., Gao J.P., Zhu M.Z., Shi M., Lin H.X. A previously unknown zinc finger protein, DST, regulates drought and salt tolerance in rice via stomatal aperture control. Genes Dev. 2009;23:1805–1817. doi: 10.1101/gad.1812409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang X., Zhang J., Song J., Huang M., Cai J., Zhou Q., Dai T., Jiang D. Abscisic acid and hydrogen peroxide are involved in drought priming-induced drought tolerance in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) Plant Biol. 2020;22:1113–1122. doi: 10.1111/plb.13143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang X., Zhang L., Dong F., Gao J., Galbraith D.W., Song C.-P. Hydrogen peroxide is involved in abscisic acid-induced stomatal closure in Vicia faba. Plant Physiol. 2001;126:1438–1448. doi: 10.1104/pp.126.4.1438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sergiev I., Alexieva V., Karanov E.N., Karanov E., Sergiev L.M., Karanova E., Alexieva V. Effect of spermine, atrazine and combination between them on some endogenous protective systems and stress markers in plants. Comptes Rendus Acad. Bulg. Sci. 1997;51:121–124. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Otter P.A. Apoplastic peroxidases and lignification in needles of Norway Spruce (Picea abies L.) Plant Physiol. 1994;106:53–60. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.1.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chance M.A. The assay of catalases and peroxidases. Methods Biochem. Anal. 1954;1:357–424. doi: 10.1002/9780470110171.ch14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fridovich B.A. Superoxide dismutase: Improved assays and an assay applicable to acrylamide gels. Anal. Biochem. 1971;44:276–287. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(71)90370-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.