Abstract

Background and Objective:

Child- and adolescent-onset psychopathology is known to increase the risk for developing substance use and substance use disorders (SUDs). While pharmacotherapy is effective in treating pediatric psychiatric disorders, the impact of medication on the ultimate risk to develop SUDs in these youth remains unclear.

Methods:

We conducted a Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) systematic review of peer-reviewed literature published on PubMed through November 2021, examining pharmacological treatments of psychiatric disorders in adolescents and young adults and their effect on substance use, misuse, and use disorder development.

Results:

Our search terms yielded 21 studies examining the impact of pharmacotherapy and later SUD in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), two studies on Major Depressive Disorder, and three studies on psychotic disorders. The majority of these studies reported reductions in SUD (N = 14 sides) followed by no effects (N = 10) and enhanced rates of SUD (N = 2). Studies in ADHD also reported that earlier-onset and longer-duration treatment was associated with the largest risk reduction for later SUD.

Conclusions:

Overall, pharmacological treatments for psychiatric disorders appear to mitigate the development of SUD, especially when treatment is initiated early and for longer durations. More studies on the development of SUD linked to the effects of psychotherapy alone and in combination with medication, medication initiation and duration, adequacy of treatment, non-ADHD disorders, and psychiatric comorbidity are necessary.

Keywords: pharmacotherapy, adolescent, psychiatric disorders, substance use

Introduction

Substance use and substance use disorders (SUD) are common in the United States. In 2020, it was estimated that 139 million people endorsed alcohol use, 51.7 million endorsed tobacco use, 49.6 million people endorsed marijuana use, and 59.3 million people endorsed illicit drug use. In addition, 20.4 million people over 12 years (7.4% of this population) reported having an SUD, including 14.5 and 8.3 million people with past-year alcohol and illicit drug use disorders, respectively (Administration, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services 2020). The onset and highest rates of SUD are reported in individuals ages 18 to 25 years (Han et al. 2017; Esser et al. 2019; Administration, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services 2020). For example, one study reported a mean age of substance use onset of 13 years and other studies support that almost one-half of SUD begins before age 18 years (Compton et al. 2000; Han et al. 2017).

Individuals who report initiating substance use before the age of 18 are associated with worse outcomes, including higher rates of SUD, poor health, and worse social outcomes (Poudel and Gautam 2017). Given that hazardous substance use and SUD are associated with high degrees of morbidity and mortality, more efforts are needed to identify ways to mitigate the risk for developing SUD in young people (Esser et al. 2020).

One of the most replicated and robust risk factors for developing SUD in young people is the presence of psychopathology (Abraham and Fava 1999; Kessler 2004; Wilens et al. 2011; Merikangas and McClair 2012; Groenman et al. 2017). Similar to the initiation of SUD, psychopathology frequently begins in childhood, with 25%–50% of adult psychiatric disorders beginning before age 18 years [for review see Wilens et al. (2018)]. These childhood-onset disorders have been shown to increase the risk of developing SUD. For instance, children and adolescents with major depressive disorder (MDD) are twice as likely to develop an SUD (Alpert et al. 1994). Similarly, individuals with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) are two to three times more likely to develop an SUD (Wilens et al. 2011; Groenman et al. 2017).

Similar findings have been shown for virtually all major psychiatric disorders of childhood (Groenman et al. 2017). Co-occurring SUD and psychiatric disorders are linked to various adverse outcomes, including increased odds of additional psychopathology, hospitalizations, suicide attempts, drug overdoses, criminal behavior, and homelessness (Gonzalez and Rosenheck 2002; Mitchell et al. 2007; Curran et al. 2008; Oquendo et al. 2010; Bohnert et al. 2012; Wilton and Stewart 2017; Yule et al. 2018). Left untreated, adults with co-occurring disorders report overall lower quality of life, and lower social and occupational functioning (Saatcioglu et al. 2008; Kronenberg et al. 2014).

Pharmacotherapy is one of the most utilized and well-studied treatments in the management of juvenile-onset psychopathology (MK 2022). Despite multiple controlled trials demonstrating its shorter-term efficacy for various disorders, questions remain about the longer-term impacts of pharmacotherapy on functional outcomes such as the development of SUD. This is of particular importance given that untreated psychopathology robustly increases the risk for later SUDs, and its management may be critical in the mitigation of subsequent SUD (Volkow et al. 2019). Moreover, concerns linger as to the potential for psychotropics in children to actually increase the ultimate likelihood for substance misuse and use disorders (Al-Haidar 2008). Understanding the role of pharmacotherapy on the ultimate risk for SUD in children and adolescents has the immense potential to affect public policy, clinical decisions, and research domains related to preventing substance use and SUD.

To this end, we systematically reviewed the existing literature to examine the impact of treating psychopathology pharmacologically in children and adolescents on the ultimate risk of developing subsequent substance use, misuse, or SUD. We also aimed to determine whether a differential risk for developing subsequent SUD exists based on the specific psychiatric disorder(s) being treated. Based on conceptual considerations, and our prior work, we hypothesized that the pharmacotherapy of juvenile psychopathology would not increase but would instead reduce the risk for the development of substance use, misuse and/or SUD (Wilens 2003; Wilens et al. 2016; Volkow et al. 2019; Boland et al. 2020).

Methods

We conducted a Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) systematic review of peer-reviewed literature published through November 2021, examining pharmacological treatments of psychiatric disorders in adolescents and young adults and their effect on substance use/use disorder development. We searched the PubMed database using various combinations of the following terms (see Table 1): “Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder,” “mood disorder,” “depressive disorder,” “bipolar disorder,” “psychotic disorder,” “anxiety disorder,” “conduct disorder,” “personality disorder,” “post-traumatic stress disorder,” “adolescent,” “child,” “childhood,” drug therapy,” “complications,” substance-related disorders,” “substance use,” and “substance abuse.” Bibliographies of reviewed articles were also examined for additional studies to ensure that no relevant articles were omitted.

Table 1.

Search Terms

| Disorder treatment effect on substance use/use disorder development | Search terms |

|---|---|

| ADHD | (((“Adolescent”[mesh] OR adolescent[ti] OR “child”[mesh] OR child[ti] OR childhood[tiab]) AND (“Attention Deficit Disorder with Hyperactivity/complications”[mesh] OR “Attention Deficit Disorder with Hyperactivity/drug therapy”[Mesh]) AND (SUD[tiab] OR “Substance-Related Disorders/complications”[mesh] OR “Substance-Related Disorders/epidemiology”[mesh] OR Substance abuse[tiab]))) |

| Mood disorder | (((“Adolescent”[mesh] OR adolescent[ti] OR “child”[mesh] OR child[ti OR childhood[tiab]]) AND (“Mood Disorders/complications”[Mesh] OR “Mood Disorders/drug therapy”[Mesh]) AND (SUD[tiab] OR “Substance-Related Disorders/complications”[mesh] OR “Substance-Related Disorders/epidemiology”[mesh] OR Substance abuse[tiab]))) |

| Depressive disorder | (((“Adolescent”[mesh] OR adolescent[ti] OR “child”[mesh] OR child[ti] OR childhood[tiab]) AND (“Depressive Disorder/complications”[Mesh] OR “Depressive Disorder/drug therapy”[Mesh]) AND (SUD[tiab] OR “Substance-Related Disorders/complications”[mesh] OR “Substance-Related Disorders/epidemiology”[mesh] OR Substance abuse[tiab]))) |

| Bipolar disorder | (((“Adolescent”[mesh] OR adolescent[ti] OR “child”[mesh] OR child[ti] OR childhood[tiab]) AND (“Bipolar Disorder/complications”[Mesh] OR “Bipolar Disorder/drug therapy”[Mesh]) AND (SUD[tiab] OR “Substance-Related Disorders/complications”[mesh] OR “Substance-Related Disorders/epidemiology”[mesh] OR Substance abuse[tiab]))) |

| Psychotic disorder | (((“Adolescent”[mesh] OR adolescent[ti] OR “child”[mesh] OR child[ti] OR childhood[tiab]) AND (“Psychotic Disorders/complications”[Mesh] OR “Psychotic Disorders/drug therapy”[Mesh]) AND (SUD[tiab] OR “Substance-Related Disorders/complications”[mesh] OR “Substance-Related Disorders/epidemiology”[mesh] OR Substance abuse[tiab]))) |

| Anxiety disorder | (((“Adolescent”[mesh] OR adolescent[ti] OR “child”[mesh] OR child[ti] OR childhood[tiab]) AND (“Anxiety Disorders/complications”[Mesh] OR “Anxiety Disorders/drug therapy”[Mesh]) AND (SUD[tiab] OR “Substance-Related Disorders/complications”[mesh] OR “Substance-Related Disorders/epidemiology”[mesh] OR Substance abuse[tiab]))) |

| CD | (((“Adolescent”[mesh] OR adolescent[ti] OR “child”[mesh] OR child[ti] OR childhood[tiab]) AND (“Conduct Disorder/complications”[Mesh] OR “Conduct Disorder/drug therapy”[Mesh]) AND (SUD[tiab] OR “Substance-Related Disorders/complications”[mesh] OR “Substance-Related Disorders/epidemiology”[mesh] OR Substance abuse[tiab]))) |

| Personality disorder | (((“Adolescent”[mesh] OR adolescent[ti] OR “child”[mesh] OR child[ti] OR childhood[tiab]) AND (“Personality Disorder/complications”[Mesh] OR “Personality Disorder/drug therapy”[Mesh]) AND (SUD[tiab] OR “Substance-Related Disorders/complications”[mesh] OR “Substance-Related Disorders/epidemiology”[mesh] OR Substance abuse[tiab]))) |

| Post-traumatic stress disorder | (((“Adolescent”[mesh] OR adolescent[ti] OR “child”[mesh] OR child[ti] OR childhood[tiab]) AND (“PTSD/complications”[Mesh] OR “PTSD/drug therapy”[Mesh]) AND (SUD[tiab] OR “Substance-Related Disorders/complications”[mesh] OR “Substance-Related Disorders/epidemiology”[mesh] OR Substance abuse[tiab]))) |

ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; CD, conduct disorder.

The inclusion criteria were primary prospective quantitative studies examining pharmacological treatments of psychiatric disorders in adolescents and young adults and their effect on the development of substance use/use disorder. Studies were included only if they included adolescents and young adults (up to 24 years of age), were published in English between 1976 and 2021, and had a follow-up period of at least one year. We excluded editorials, commentaries, opinion articles, chapters, review articles, and studies involving only nonpharmacological interventions. Any remaining discrepancies were resolved through discussion.

Selection of studies

Two reviewers independently screened the titles and abstracts of all articles (J.D.K. and D.W.). Any disagreements were resolved by consensus and irrelevant titles were excluded. A record was kept of all irrelevant and duplicate articles. The full texts of the remaining articles were reviewed by three investigators and included/excluded (J.D.K., D.W., and A.B.). A third senior reviewer reviewed the included articles (T.W.).

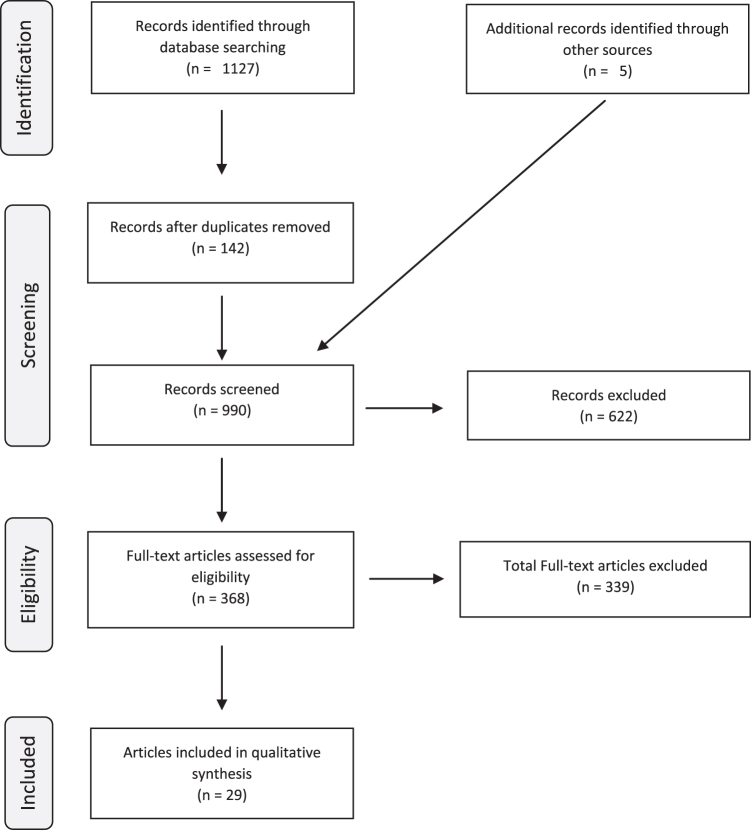

We initially found a total of 1127 articles: 319 for ADHD, 9 for Mood Disorder, 280 for MDD, 129 for Bipolar Disorder, 165 for Psychotic Disorder, 167 for Anxiety Disorder, 58 for Conduct Disorder (CD), 0 for Personality Disorder, and 0 for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. The results were combined to exclude 142 duplicate (or even triplicate) findings. Nine hundred ninety articles were screened according to the exclusion criteria. Three hundred seventy-one titles appeared to be clearly irrelevant to our interest for our review; 32 were published before 1976, 43 were in vitro, and 176 were reviews and opinion pieces.

We then reviewed the remaining 368 articles in full text for exclusion. We found 35 studies involving nonpharmacological treatments, 12 involving less than 1 year of follow-up, 34 with subjects with prior SUD, 23 involving primary SUD treatment, 6 commentaries, 34 involving primarily adult population, 194 descriptive studies, and 1 irrelevant article. The remaining 29 articles were included in our review. Three articles were earlier publications of longitudinal studies, leaving 26 final studies. Five studies were added outside of our search, either independently or from citations in primary studies (Figure 1).

FIG. 1.

PRISMA diagram. PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

Data extraction, analysis, and synthesis

Data were extracted from the quantitative studies by three reviewers using a standardized extraction form designed with the senior reviewer. The following variables were extracted: Study date, disorder, follow-up, subjects, age, sex, measures administered for psychopathology, medication, and findings.

Results

Population

Our search terms yielded 21 studies examining the impact of pharmacotherapy and later SUD in ADHD, 2 studies on MDD, and 3 studies on psychotic disorders (Table 2 and Table 3). There were no studies examining the impact of pharmacotherapy on SUD with anxiety, CD alone, or personality disorders. In 17 of 26 treatment studies, the population was predominately male (>60% male). In seven of these studies, the ratio of male to female was ∼1:1, and the remaining two articles did not report the gender of their participants.

Table 2.

The Impact of Pharmacotherapy of Childhood-Onset Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder on the Development of Substance Use/Use Disorders

| Disorder | Study | Follow-up (years) | Subjects | Age and sex | Measure | Medication | Findings | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADHD treatment reduced subsequent substance use/use disorders | ||||||||

| ADHD | Paternite et al. (1999) (Prospective longitudinal follow-up), fall-back) | At ages 21–23 years |

N (total) = 219 N (ADHD) = 219 N (no ADHD) = N/A N (Tx stimulant ADHD) = 121 N (Tx behavioral ADHD) = 98 |

4–12-Year-olds 100% male |

ADHD dx: psychiatric chart Substance use: SADS-L SUD dx: SADS-L |

MPH | Higher doses of MPH Tx associated with fewer AUD diagnoses. Magnitude of effect not reported. | Higher MPH dose with lower suicide attempts Better response to medication was associated with lower MMPI D scores and better social functioning Longer MPH duration was associated with multiple academic, social, and psychiatric outcomes over time |

| ADHD | Biederman et al. (1999) (Prospective longitudinal follow-up) Biederman (2003) (Prospective longitudinal follow-up) Biederman et al. (2008) (Prospective longitudinal follow-up) |

4 Years 10 Years |

N = 212 N = 56 Tx ADHD N = 19 UnTx ADHD N = 137 non-ADHD controls Initial N (total) = 260 N (ADHD) = 140 N (no ADHD) = 120 N (Tx ADHD) = 92 N (UnTx ADHD) = 39 follow-up N (ADHD) = 112a N (Tx ADHD) = 82 N (UnTx ADHD) = 30 |

15–21-Year-olds 100% male 6–17 Years old (mean @ follow-up = 22 years old) 100% male |

K-SADS | Stimulants and non-stimulants for ADHD Tx | Tx ADHD at baseline were at a significantly reduced risk for a SUD at follow-up in adolescence versus UnTx ADHD (aOR: 0.15 [0.04–0.6]) Follow-up of smaller sample into adulthood did not show stimulant/nonstimulant Tx impact on SUDs |

Findings adjusted for baseline severity between groups The direction of the Tx effect similar for each SUD Only small group of adults persistently on stimulants in follow-up |

| ADHD | Katusic et al. (2005) (Retrospective cohort) |

17.2 Years |

N (total) = 1137 N (ADHD) = 379 N (controls) = 758 N (Tx ADHD) = 295 N (UnTx ADHD) = 84 |

5+ Years old 74.9% male |

ADHD dx, SUD dx: School and medical records (teacher/parent questionnaires, dx ADHD, Tx hx) |

Stimulants | Tx ADHD were at significantly decreased risk for developing SUD compared UnTx ADHD (20% vs. 27%) | Findings largely accounted for by the significant decrease in substance use in Tx versus UnTx boys with ADHD (22% vs. 36%) |

| ADHD | Wilens et al. (2008) (Prospective longitudinal follow-up) | 5 Years |

N (total) = 262 N (ADHD) = 140 N (no ADHD) = 122 follow-up N (ADHD) = 114 N (Tx ADHD) = 94 N (UnTx ADHD) = 20 |

6–18-Year-olds with ADHD 100% female |

SCID/K-SADS | Stimulants | Stimulant exposure decreased likelihood of manifesting a SUD compared to no stimulant exposure (N = 113; HR = 0.27 [0.125–0.60], χ2 = 10.57, p = 0.001) | Significant protective effect of stimulant exposure on the age-adjusted rate of development of drug use disorders |

| ADHD | Chang et al. (2014) (Retrospective cohort, registry) | 3 Years |

N (controls) = N (ADHD) = 38,753 N (Tx ADHD) = 19,410b N (UnTx ADHD) = 19,343b |

8–46-Year-olds 49.3% male |

ADHD dx: ICD diagnoses from the National Patient Register Substance use: ICD codes and convictions for substance related crime |

Stimulants and nonstimulants | Tx ADHD youth aged ≤15 years had a 31% significantly decreased rate of SUD compared to UnTx youth There was a 13% decrease in SUD risk for every year of stimulant Tx |

No indication that stimulant ADHD medication increased the rate of SUD in this cohort but rather, there was a negative association (HR = 0.38, 95% CI [0.23–0.64]) |

| ADHD | Hammerness et al. (2017) (Prospective open-label clinical trial) | 24 Months |

N (total) = 211 N (no ADHD) = 52 N (Tx ADHD) = 115 N (comparators) = 44c |

12–17-year-olds Tx 76% male, controls 73% male, comparators 68% male |

ADHD dx: clinical interview SUD dx Substance use: DUSI, urine toxicology screensd |

Extended-release MPH | Tx ADHD had significantly lower rates of alcohol [χ2 (3) = 12.56, p = 0.006] and drug use [χ2 (3) = 18.68, p = 0.001] when compared to UnTx and comparators No significant differences in rates of alcohol and drug use between Tx ADHD and non-ADHD controls |

Prospective clinical trial with main outcomes smoking, substance use, and SUD |

| ADHD | Quinn et al. (2017) (Prospective longitudinal observational) | Up to 9 years |

N (total) = 2,993, 887 N (no ADHD) = N/A N (ADHD) = 2,993,887 N (Tx ADHD) = 2,552,774 N (UnTx ADHD) = 441,113 |

13 Years old or older 52.8% male |

ADHD dx: ICD codes and/or ADHD Tx history in health care claims Substance-related events: substance use Tx history (emergency department claims, Tx visits) |

Stimulants and/or atomoxetine | Lower risk (male 35%, female 31%) of concurrent substance-related events during Tx episodes versus UnTx episodes Lower risk for SUD between Tx and UnTx ADHD; and ∼50% reduction in new onset of SUD in Tx versus UnTx groups Lower odds of substance-related events at 2-year follow-up in male patients (OR = 0.81, 95% CI [0.78–0.85]) and female patients (OR = 0.86, 95% CI [0.82–0.91]) |

In adjusted within-individual models, ADHD medication predicted a 19% reduction in the odds of substance-related events 2 years later among male patients (OR = 0.81, 95% CI [0.78–0.85]) and a 14% reduction among female patients (OR = 0.86, 95% CI [0.82–0.91]) |

| ADHD | Upadhyay et al. (2017) (Retrospective cohort from survey) | Not reported |

N (total) = 6483 N (no ADHD) = 5498 N (ADHD) = 985 N (Tx ADHD) = 333 N (UnTx ADHD) = 652 |

13–18-Year-olds 65.4% male |

ADHD dx: WHO CIDI Substance use: NCS-A SUD dx: NCS-A |

Not specified | Tx ADHD had significantly lower rates of substance use when compared to UnTx ADHD (OR = 0.53, 95% CI [0.31–0.90]) | ADHD Tx is negatively associated with substance use in adolescents with ADHD-C (OR = 0.53, 95% CI [0.24–0.97]) and those with ADHD-H (OR = 0.23, 95% CI [0.07–0.78]), but not ADHD-I subtype (OR = 0.49, 95% CI [0.17–1.39]) |

| ADHD and CD | Rasmussen et al. (2019) (Case control, retrospective survey) |

Retrospective |

N (total) = 472 N (no ADHD) = N/A N (ADHD) = 472 N (Tx ADHD) = 136 N (UnTx ADHD) = 336 |

17–56-Year-olds 72.7% male |

ADHD dx: SCL-90 R; The hyperkinetic checklist Substance use: SCL-90 R |

Stimulants | Tx ADHD had significantly lower rates of SUD compared to UnTx ADHD: Alcohol (13% vs. 34%) and drug (20% vs. 37%) | Previously CD-treated persons had a substantially lower frequency of problems (alcohol/substance abuse, criminality), and of certain psychiatric disorders (depressive, anxiety, and personality ones) |

| ADHD treatment increased subsequent substance use/use disorders | ||||||||

| ADHD | Lambert and Hartsough (1998) Lambert (2002) |

24–28 Years |

N = 492 N = 175 stimulant-Tx ADHD N = 39 with Tx ADHD and seizures N = 68 with ADHD without stimulant Tx N = 51 without ADHD with behavior problems N = 159 non-ADHD age-matched controls |

Kindergarten to 5th grade 83% male controls: 82% male |

CSBS and QDIS-III-R | Stimulant Tx for >6 weeks | ADHD > controls: tobacco, alcohol, marijuana, “stimulants,” and cocaine dependence Tx >1 year with stimulants versus Tx <6 months or no TX had higher rates: tobacco (42% vs. 26%) and cocaine dependency (21% vs. 10%). Follow-up: Tx ADHD with stimulants >1 year were twice as likely to become dependent on cocaine as UnTx |

CD, a major independent contributor to SUD, was not accounted for and was overrepresented in the group Tx with stimulants |

| ADHD treatment had no effect on subsequent substance use/use disorders | ||||||||

| Reading disorder and ADHD | Mannuzza et al. (2003) | 16 Years |

N = 231 N (reading disorder Tx) = 39 N (reading disorder UnTxe) = 63 N (controls) = 129 |

7–13-Year-olds 73.6% male |

Reading disorder dx: WISC K-SADS and DSM III-R |

MPH | No significant differences among Tx versus UnTx groups on rates of SUD | Normal controls had a significantly higher rate of cocaine use (60%; p = 0.01) compared to ADHD groups |

| ADHD | Barkley et al. (2003) (Prospective longitudinal follow-up) | 13 Years |

N (total) = 239 N (no ADHD) = 81 N (ADHD) = 158 N (Tx children ADHD) = 98 N (UnTx children ADHD) = 21 N (Tx high schoolers ADHD) = 32 N (UnTx high schoolers ADHD) = 115 |

4–12 Years | ADHD dx: CPRS-R, WWPARS, SCID Substance use: SCID |

Stimulants (MPH, d-amphetamine, pemoline, or combination of MPH and d-amphetamine or pemoline and d-amphetamine) |

No significant differences among Tx versus UnTx groups on rates of SUD, except for cocaine use. Higher risk for cocaine use disorders in Tx versus untreated groups (26% vs. 5%; p = 0.037) Duration of Tx not associated with any SUD risk |

Significant effect of Tx on subsequent SUD lost after correcting for ADHD severity and comorbid CD |

| ADHD | Faraone et al. (2007) (Case control, retrospective survey) | N/A |

N (total) = 206 N (full ADHD) = 127 N (late onset ADHD) = 38 N (ADHD UnTx) = 108 N (ADHD past Tx) = 33 N (ADHD past and current Tx) = 65 |

18–55-Year-olds 48% male in late-onset ADHD 53% male in full ADHD |

SCID/K-SADS DUSI |

Stimulant/nonstimulant Tx for ADHD | No significant differences among Tx versus UnTx groups on rates of SUD | Retrospective case control survey |

| ADHD | Winters et al. (2011) (Prospective longitudinal follow-up) | 15 Years |

N (total) = 242 N (ADHD) = 149 N (no ADHD) = 93 |

8–10-Year-olds 81% male |

ADHD Dx: DICA-R Substance use: ADI, CUQ |

Stimulants | No effect of stimulant medication on risk of SUDs and tobacco use | |

| ADHD | Molina et al. (2013) (Randomized controlled trial) | 8 Years |

N (total) = 697 N (ADHD) = 436 N (no ADHD) = 261 N (Tx ADHD) = not reported N (UnTx ADHD) = note reported |

7–9.9-Year-olds 81.3% male |

ADHD Dx: DISC-IV; teacher reported ratings of ADHD symptoms Substance use: child/adolescent-reported MTA questionnaire SUD Dx: DISC-IV |

Predominantly stimulants, but occasionally atomoxetine, guanfacine, clonidine, and amitriptyline | No significant differences among Tx versus UnTx groups on rates of SUD or substance use | Neither randomized Tx assignment nor proportion of days medicated in the past year was a predictor of SUD at the 6- and 8-year assessments |

| ADHD | Dalsgaard et al. (2014) (Retrospective cohort, registry) | 31 Years old |

N (total) = 2,500,208 N (ADHD) = 208 N (no ADHD) = 2,500,000 N (Tx ADHD) = 208 N (UnTx ADHD) = 2,499,792 |

4–15-Year-olds 87.9% male |

ADHD dx: DSM-IV and ICD-10 diagnostic checklists SUD dx and substance use: ICD diagnoses from national register |

MPH or dexamphetamine | No effect of stimulant Tx in childhood on adult SUD Early initiation of stimulant Tx for ADHD was associated with a reduced risk of later alcohol and other SUDs |

For every year older at initiation of stimulants, the risk of SUD in adulthood increased by a factor of 1.46 |

| ADHD | Levy et al. (2014) (Retrospective survey) | Not reported |

N (total) = N (ADHD) = 232 N (no ADHD) = 335 N (Tx ADHDf) = 139 N (UnTx ADHD) = 93 |

Birth cohort; at least 5 years of age ADHD 72% male; controls 62.7% male |

ADHD dx: school and medical records, MINI SUD dx: school and medical records, MINI |

Stimulants | No significant differences among Tx versus UnTx groups on rates of SUD Higher risk for SUD in those Tx after age 13 years |

Confounds not accounted for in analyses |

| ADHD | McCabe et al. (2016) (Retrospective cohort, multi-cohort national registry) | Not reported |

N (total) = 40,358 N (controls) = 35,447 N (ADHD) = 4911 N (Tx stimulant ADHD) = 3539 N (Tx nonstimulant ADHD) = 1332 N (UnTx ADHD) = not reported |

High school seniors 48% male |

Substance use: alcohol single question, cigarette questionnaire, marijuana and other drug use questionnaire. ADHD dx: not reported |

Stimulant and nonstimulant medication therapy for ADHD. | No significant differences among Tx versus UnTx groups on rates of SUD Individuals who initiated Tx earlier (<9 years old) and for a longer duration (6 years or more) had significantly lower risk for substance use compared to individuals who initiated Tx later (>9 years old) and for a shorter duration (<6 years) |

In general, the prevalence of substance use was highest among individuals who reported the latest onset and shortest duration of prescription stimulant medication therapy for ADHD (aOR for Controls 1.8 (95% CI [1.3–2.6]) |

| ADHD | McCabe et al. (2016) (Retrospective cohort, Multi-cohort National Registry) | 4 Years |

N (total) = 4755 N (ADHD) = 556 N (Tx medical ADHD) = 322 N (nonmedical use) = 124 |

Secondary school students 47.1% male |

SSLS | Stimulants | Individuals who initiated Tx earlier (≤9 years of age) had significantly lower odds of marijuana and other substance use compared to those who initiated Tx later (>9 years of age) | The odds of substance use and substance-related problems were significantly greater among those who initiated earlier nonmedical use of stimulant medications relative to later nonmedical initiation |

| ADHD | Mannuzza et al. (2008) (Prospective longitudinal follow-up) | Late adolescence (M = 18.4) and adulthood (M = 15.3) |

N (total) = 354 N (no ADHD) = 178 N (ADHD) = 176 N (Tx ADHD) = 176 N (UnTx ADHD) = N/A |

6–12-Year-olds 100% male |

ADHD, substance use and SUD: DISC, CHAMPS | MPH | Earlier onset ADHD Tx (initiation ages <7 years) had significantly lower rates of SUD compared to later onset ADHD Tx (initiation ages 8–12) (27% vs. 44% Wald χ2 = 5.38, p < 0.02) | Even when controlling for SUD, age at stimulant Tx initiation was significantly and positively related to the subsequent antisocial personality disorder Age at first MPH Tx was unrelated to mood and anxiety disorders |

| ADHD and CD | Harty et al. (2011) (Prospective longitudinal follow-up) | 9.3 Years |

N (total) = 182 N (no ADHD) = 85 N (ADHD) = 66 N (ADHD+CD) = 31 N (Tx ADHD) = 69 N (UnTx ADHD) = 28 |

7–11-Year-olds 87.8% male |

ADHD dx: DISC; CBCL; IOWA; CPRS CD dx: CBCL; IOWA; CPRS Substance use: K-SADS; RAPI SUD dx: K-SADS. |

Stimulants | No significant differences among Tx versus UnTx groups on rates of SUD | Within an ethnically diverse urban sample, the increased rate of substance use associated with ADHD was fully accounted for by comorbid CD |

Statistical analyses conducted on this group only.

Not reported specifically for 15 and under, however, 48.7% of male patients and 53% of female patients in total sample were exposed to ADHD (Tx).

Eighteen currently on medication, 26 not currently on medication (historical Tx history not specified).

Tx participants only.

Placebo.

Tx defined as 6 months of longer.

ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; ADI, Adolescent Diagnostic Interview; aOR, adjusted odds ratio; CBCL, Child Behavior Checklist; CD, conduct disorder; CDRS-R, Children's Depression Rating Scale-Revised; CGAS, Children's Global Assessment Scale; CHAMPS, Schedule for the Assessment of Conduct, Hyperactivity, Anxiety, Mood, and Psychoactive Substances; CI, confidence interval; CPRS-R, Conners Parent Rating Scale-Revised; CSBS, California Smoking Baseline Survey; CUQ, Cigarette Use Questionnaire; DICA-R, Diagnostic Interview for Children and Adolescents-Revised; DISC-IV, Diagnostic Interview Schedule-IV; DSM III-R, Lifetime Semi Structured Psychiatric Interview; DUSI, Drug Use Screening Inventory; dx, diagnosis; hx, history; ICD, International Classification of Disease; IOWA, Inattention/Overactivity with Aggression; K-SADS, Schedule for the Assessment of Conduct, Hyperactivity, Anxiety, Mood; MDD, major depressive disorder; MINI, Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview; MPH, methylphenidate; MTA, Multimodal Treatment Study of Children with ADHD; NCS-A, National Comorbidity Survey-Adolescent; NMUPPR, Non-Medical Use of Prescription Pain Relievers; OR, odds ratio; QDIS-III-R, Quick Diagnostic Interview Schedule 3rd edition; RADS, Reynolds Adolescent Depression Scale; RAPI, Rutgers's Alcohol and Drug Use Problem Index Questionnaire.; SADS-L, Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia-Lifetime; SCID, Structured Clinical Interview for DSM Disorders; SIQ-Jr, Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire-Jr. High Version; SSLS, Secondary Student Life Survey; SUD, substance use disorder; TAU, treatment as usual; Tx, treatment; UnTx, untreated; WHO CIDI, World Health Organization Composite International Diagnostic Interview 3.0; WISC, Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children; WWPARS, Werry-Weiss-Peters Activity Rating Scale.

Table 3.

The Impact of Pharmacotherapy of Childhood-onset Mood or Psychotic Disorders on the Development of Substance Use Disorders

| Disorder | Study | Follow-up (years) | Subjects | Age and sex | Measure | Medication | Findings | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depressive Disorder | Curry et al. (2012) (Randomized Control Tx) | 5 Years |

N (total) = 192 N (depression no SUD) = 192 |

12–18-Year-olds 43.8% male |

Demographics, Duration of Index MDE, CDRS-R, RADS, SIQ-Jr., CGAS, Comorbidity for mental health disorders/SUD | Mental health Tx-CBT, FLX, combination of CBT and FLX, or placebo | Short-term MDD Tx significantly reduced the rate of subsequent drug use disorder but not AUD specifically. Twelve of 103 TADS treatment responders (11.6%) developed an SUD versus 22 of 89 nonresponders (24.7%) [χ2 (1, N = 192) = 5.38, OR = 2.49 [1.15–5.38], p- = 0.02]. |

Before depression Tx, greater involvement with alcohol or drugs predicted later AUD or SUD, as did older age (for AUD) and more comorbid disorders (for SUD) |

| Depressive Disorder | Carrà et al. (2019) (Retrospective cohort, National Registry) | Retrospective |

N (total) = 391,753 N (youth depression) = 121,526 N (adult depression) = 270,227 |

12–17-Year-olds and 18+ 51.1% and 48.2% male respectively |

National Comorbidity Survey-Adolescent measured NMUPPR | Mental health Tx and/or substance use Tx | The likelihood of reports NMUPPRs among respondents who did not receive any Tx was higher for those with past year MDE. MDE risk ratio for youths who received some Tx (Mental Health or Substance Use Tx) was about 70–80% (ARR = 1.15, p < 001)) as compared with their UnTx counterpart (ARR = 1.57, p < 001) |

The analysis did not differentiate the type of Tx or describe details of Mental Health Tx |

| Bipolar Disorder | Goldstein et al. (2013) (Prospective longitudinal follow-up) | 4.25 Years |

N (total) = 167 N (bipolar no SUD) = 167 |

12–17 Years old % male not listed |

K-SADS, K-MRS | Psychotropic medications | Greater proximal use of Lithium (exposure in the preceding 12-week period) predicted lower likelihood of SUD development (HR: 0.99, 95% CI [0.97–1.00], p = 0.02). In contrast, use of antidepressants and any psychotropic medication other than Li had increased risk for developing SUD. |

Greater hypo/manic symptom severity in the preceding 12 weeks predicted greater likelihood of SUD onset |

| Psychotic Disorder | Turner et al. (2009) (Prospective longitudinal follow-up) | 2 Years |

N (total) = 236 N (psychotic features) = 236 |

16–30 Years old 72.5% male |

DSM-IV clinical diagnosis, substance use assessment, PANSS, GAF, duration of untreated psychosis before starting an antipsychotic, QLS, HoNOS | Low-dose atypical antipsychotics | Marginal reduction in SUD (16%, p < 0.10) in SUD from baseline in individuals who continued Tx versus those who stopped Tx. | Participants reported substance use, but not necessarily SUD |

| Psychotic Disorder | Petersen et al. (2007) (Uncontrolled open incidence cohort) | 2 Years |

N (total) = 547 N (schizophrenia spectrum) = 547 N (OPUS Tx) = 275 N (standard Tx) = 272 |

M = 25 years old 70.0% male |

SCAN, SAPS, SANS | Second generation antipsychotics | Multidisciplinary Tx reduced SUD (OR = 0.5; 95% CI [0.3–10], p = 0.05) and improved clinical outcome in the SUD group versus TAU (reduced hospitalized days (109 days vs. 167 days) | Evaluation of multidisciplinary team approach versus treatment as usual. Both groups received antipsychotics. |

CDRS-R, Children's Depression Rating Scale-Revised; CGAS, Children's Global Assessment Scale; CI, confidence interval; GAF, Global Assessment of Functioning; HoNOS, Health of the Nation Outcome Scale; HR, hazards ratio; K-MRS, Kiddie Mania Rating Scale; K-SADS, Schedule for the Assessment of Conduct, Hyperactivity, Anxiety, Mood; NMUPPR, Non-Medical Use of Prescription Pain Relievers; PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; OR, odds ratio; QLS, Quality of Life Scale; RADS, Reynolds Adolescent Depression Scale; SANS, Scale for Assessment of Negative Symptoms; SAPS, Scale for Assessment of Positive Symptoms; SCAN, Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry; SIQ-Jr, Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire-Jr. High Version; SUD, Substance Use Disorder; Tx, treatment; UnTx, untreated.

Treatment type

All 26 studies examined the impact of one or more treatments on the development of SUD. Twenty-one studies examined stimulants, including methylphenidate, amphetamine, pemoline, and dextroamphetamine. Two studies used nonstimulants, including atomoxetine and guanfacine (Molina et al. 2013; Quinn et al. 2017). Two studies used psychotherapy in addition to medications, including cognitive behavior therapy (Curry et al. 2012; Carrà et al. 2019). Three studies examined antipsychotic medication, including lithium (Petersen et al. 2007; Turner et al. 2009; Goldstein et al. 2013). Two studies examined the impact of antidepressants (Curry et al. 2012; Goldstein et al. 2013). One study examined substance use treatment (Carrà et al. 2019).

Treatment outcomes

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder

The majority of studies showed a positive impact on the effect of stimulants and other ADHD treatments in reducing the development of SUDs. Eleven studies (48%) found that patients who received treatment for ADHD were less likely to develop an SUD and experience adverse outcomes related to substance use. Biederman et al. (2008) found that treatment for ADHD had a significant protective effect (odds ratio [OR]: 0.15 [0.04–0.6]) for developing SUD in adolescence, which was no longer found in adulthood-the authors noted low medication adherence into adulthood (Biederman et al. 2008).

In a large claims database of almost 3 million individuals with ADHD, Quinn et al. (2017) found that individuals treated for ADHD were ∼50% less likely to develop a new onset of SUD compared to individuals who did not receive treatment. This group also showed an ∼30% reduced likelihood to manifest SUD during active times of receiving versus not receiving medication treatment (Quinn et al. 2017).

Similarly, Chang et al. (2014) found a 13% reduction in SUD risk for every year of stimulant treatment (Chang et al. 2014). In contrast, Lambert et al. (2002) found that individuals who used stimulants for over 1 year were significantly more likely to use tobacco (42% vs. 26%) and become dependent on cocaine (21% vs. 10%)—although this study was confounded by higher ADHD severity and CD prevalence in the group receiving stimulants (Lambert and Hartsough 1999). Eleven studies (48%) found no effect of stimulant use on the development of SUD compared to individuals who did not receive treatment for ADHD (Barkley et al. 2003; Mannuzza et al. 2003, 2008; Faraone et al. 2007; Wilens et al. 2008; Harty et al. 2011; Winters et al. 2011; Molina et al. 2013; Dalsgaard et al. 2014; Levy et al. 2014; McCabe et al. 2016).

Time of stimulant initiation appeared related to later SUD. Two studies (8%) did not report on the effects of stimulants on ADHD but found that earlier initiation of treatment for ADHD was associated with significantly lower odds of developing an SUD (Mannuzza et al. 2003; McCabe et al. 2016). This finding was replicated in four other studies, suggesting that earlier initiation of treatment may lead to better outcomes for SUD (Wilens et al. 2008; Dalsgaard et al. 2014; Levy et al. 2014; McCabe et al. 2016). In addition, McCabe et al. (2016) found that a longer duration of treatment (6 years or more) was associated with a lower risk for SUDs (McCabe et al. 2016). Of interest, no studies found that later initiation (e.g., adolescence) or shorter duration of treatment resulted in reduced risk for SUD.

Depressive disorders/MDD

The research was limited on the effects of treating MDD pharmacologically on the development of SUDs as only two studies met our search criteria (Curry et al. 2012; Carrà et al. 2019). Curry et al. (2012) treated 12–18 years old patients with Cognitive Behavioral Therapy and fluoxetine (Curry et al. 2012). The authors reported that the combined treatment significantly reduced the rate of subsequent drug use disorders (11.6% vs. 24.7%), but not alcohol use disorder. Carrà et al. (2019) examined the use of nonmedical prescription pain relievers in a large sample (N = 391,753) in both youth (12–17 years old) and adults (18 or older) who were receiving treatment for mental health and/or SUD (Carrà et al. 2019).

They found that individuals treated for MDD were significantly less likely to report the use of nonmedical prescription pain relievers than individuals who were not treated for MDD. However, the authors did not specify what type of treatment was most effective in preventing the use of nonmedical prescription pain relievers. Overall, research suggests that treating depressive symptoms appears to reduce the development of drug misuse and use disorder. No studies found that treatment for MDD increased the likelihood of developing an SUD.

Bipolar and psychotic disorders

Results varied on the impact of treating psychotic disorder on SUD. Two studies found that second-generation antipsychotics effectively reduced symptoms of SUDs (16%, p < 0.10; OR = 0.5; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.3–10, p = 0.05) and reduced hospitalization days from 167 to 109 (Petersen et al. 2007; Turner et al. 2009). Similarly, Goldstein et al. (2013) found that adolescents with bipolar spectrum of full disorder treated with lithium were less likely to develop an SUD (hazards ratio: 0.99, 95% CI 0.97–1.00, p = 0.02) (Goldstein et al. 2013). In contrast, Goldstein et al. (2013) found that using antidepressants and other psychotropic medication besides lithium was associated with an increased risk for developing an SUD, especially in individuals with fewer asymptomatic weeks and greater proximal hypo/manic symptom severity to the SUD episode.

Discussion

The aim of this review was to examine the impact of treating psychopathology pharmacologically in children and adolescents on the risk of developing substance use, misuse or SUD. Overall, we failed to find consistent data showing an increase in the risk for subsequent SUD associated with medication treatment of psychiatric disorders in childhood. In contrast, the data support that treating ADHD and MDD with medication appear to mitigate the risk of developing SUD. While there appear to be promising signals of reduced substance use subsequent to treatment of bipolar and psychotic disorders, clearly more data are needed to draw more definitive conclusions.

In addition, we found evidence suggesting that the earlier-onset and longer duration of treatment results in the best outcomes for reducing the likelihood of developing an SUD. In contrast to a relatively large literature on ADHD, relatively few studies examined MDD, psychosis, or psychiatric comorbidity. No studies examined disorders of anxiety, conduct (outside of ADHD), personality, or post-traumatic stress disorder.

The current findings add to the growing literature on the importance of identifying and treating psychiatric disorders in childhood through adulthood. Moreover, our findings suggest the need to treat juvenile-onset psychiatric disorders as early as possible and for long durations to have optimal outcomes in preventing longer-term sequelae such as the development of substance use, misuse, or SUD. For instance, findings in ADHD converge to show that the early-onset and longer-durations of treatment resulted in improved outcomes relative to later-onset and shorter duration treatments (McCabe et al. 2016).

We also noted that studies in samples followed over time showed enhanced protection against the development of SUD lost over time, presumably linked to adherence (Biederman et al. 2008; Quinn et al. 2017). Data from within-group designs support that unmedicated treatment periods were related to an almost 30% increase in the likelihood to develop SUD compared to medicated times (Goldstein et al. 2013; Quinn et al. 2017). It may also be that a sensitive developmental time for SUD risk exists, during which a lag in pharmacotherapy may increase youth's likelihood of developing SUD.

Whereas mood symptoms and prominent mood dysregulation drive the onset or recurrence of SUD, the current findings support that treatment of mood symptoms may oppose this effect (Wilens et al. 2013; Fatseas et al. 2018). For example, in a detailed analysis of treatment episodes in bipolar disorder, pharmacotherapy with lithium reduced the subsequent development of SUD (Goldstein et al. 2013). Similarly, we previously showed that in a sample of adolescents with bipolar disorder followed into young adulthood, those with low-level bipolar symptoms (e.g., treated and nonpersistent group) were similar to non-mood disordered controls and were at lower risk for SUD compared to those with prominent bipolar symptoms (Wilens et al. 2016). Similar findings were reported for non-bipolar depressive disorders in both prospective and retrospective between-group examinations (Curry et al. 2012; Carrà et al. 2019).

Although the specific mechanisms by which treatment of psychopathology mitigates SUD risk are largely unexplored, the extant literature suggests multiple possible pathways (Abraham and Fava 1999; Kessler 2004; Wilens et al. 2011; Merikangas and McClair 2012; Groenman et al. 2017). For example, pharmacological treatment of psychiatric symptoms may reduce the drive for self-medication via problematic substance use (Khantzian 1997; Wilens et al. 2007).

It may also be that treatment of psychopathology reduces the associated dysfunction (e.g., delinquency, academic failure) that may independently increase the risk for SUD (Trucco 2020). For instance, longer-term data with ADHD show enhanced functional outcomes, including academic performance and criminality (Boland et al. 2020). Academic underachievement and/or criminality that have been shown to increase the risk for SUD independently (Fothergill et al. 2008). Hence, treatment of ADHD may directly improve SUD outcomes, and reduce risk factors like academic underachievement and criminality that may independently contribute to SUD.

The results of our review have noteworthy clinical and public health implications. The literature showing that juvenile-onset psychiatric disorders are among the most replicable risk factors for SUD coupled with the current aggregate findings of a reduction in the ultimate risk for developing SUD with pharmacotherapy highlights the need to identify and treat psychopathology early in the life course. Signals clearly emerge from the present review that an early (e.g., <9 years of age in ADHD) and longer duration of pharmacotherapy (e.g., >6 years) were associated with the largest risk reduction in SUD. These findings highlight the need to consider initiating treatment proximal to the onset or diagnosis of psychopathology while enhancing treatment adherence over time.

There are a number of limitations in the current review. To focus on the effects of psychopharmacology, we did not include articles that focused only on psychotherapy as a treatment for psychiatric disorders, nor did we explore extensively the use of psychotherapy in pharmacological studies. Psychotherapy has a critical role in treating psychiatric disorders of all ages and should be addressed alone and in combination with pharmacotherapy for preventing SUD outcomes in future studies. In addition, the studies reviewed did not specifically address the magnitude of symptom reduction or treatment adequacy. Given the importance of improving symptoms and functionality in treating psychopathology and its downstream effect on potentially preventing the development of SUD, future research should focus on examining the extent of symptom improvement necessary to translate into better outcomes for SUD.

Likewise, the studies in our review did not mention comorbid psychiatric diagnoses. Given that individuals with ADHD, MDD, and psychotic disorders often struggle with more than one psychiatric disorder, further research is needed to better understand the impact of treatment for multiple conditions on the development of substance use/SUD. Interestingly, only one study (Hammerness et al. 2017) used a urine toxicology screen to assess for substance use. Future research should assess substance use with biological measures in addition to self-report measures to increase the detection of substance use and SUD. Future research should assess substance use with biological measures in addition to self-report measures to increase the detection of substance use and SUD. This is critical when attempting to determine whether or not the trajectory to substance use is changed.

In addition, data derived from the majority of studies did not distinguish between sociodemographic features of participants that may independently predict SUD. Further studies need to assess independent risk factors that may result in SUD. Publication bias may have contributed to a tendency of studies reporting significant differences in SUD outcomes associated with pharmacotherapy. The bulk of studies examined ADHD and may not generalize to other disorders. Finally, these studies ascertained primarily white male populations and may not generalize to the broader population.

Conclusion

Despite these limitations, our review suggests that psychopharmacological treatment in children and adolescents, in general, does not increase the likelihood for subsequent substance use, misuse, or SUD; but conversely has the potential to mitigate the development of substance misuse or SUD. In addition, these treatments may be most effective when they are initiated earlier and for longer durations of time.

Clinical Significance

Given the importance of preventing SUD, further studies examining psychotherapy alone and in combination with medications, adequacy of treatment, treatment of comorbid psychopathology, optimal onset and duration of treatment, and levels of risk reduction are necessary.

Disclaimer

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or its NIH HEAL Initiative.

Disclosures

T.W. works as a consultant for the Gavin Foundation, Bay Cove Human Services, the US National Football League, the US Minor and Major League for Baseball, and White Rhino/3D Therapy LLC. He also has a licensing agreement with Ironshore. In addition, he has published the book Straight Talk About Psychiatric Medications for Kids with the Guilford Press for which he receives royalties. A.Y. is a consultant to the Gavin House and BayCove Human Services (clinical services), as well as the American Psychiatric Association's Providers Clinical Support System Sub-Award. D.W., A.B., J.D.K., and C.B., do not have any conflicts of interest to report.

References

- Abraham HD Fava M: Order of onset of substance abuse and depression in a sample of depressed outpatients. Compr Psychiatry 40:44–50, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Administration, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services: Key Substance Use and Mental Health Indicators in the United States: Results from the 2019 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (HHS Publication No. PEP20-07-01-001, NSDUH Series H-55). Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Haidar FA: Parental attitudes toward the prescription of psychotropic medications for their children. J Family Community Med 15:35–42, 2008. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alpert JE, Maddocks A, Rosenbaum JF, Fava M: Childhood psychopathology retrospectively assessed among adults with early onset major depression. J Affect Disord 31:165–171, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkley RA, Fischer M, Smallish L, Fletcher K: Does the treatment of ADHD with stimulant medication contribute to illicit drug use/abuse? A 13 year prospective study. Pediatrics 111:97–109, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biederman J, Wilens T, Mick E, Spencer T, Faraone S: Pharmacotherapy of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder reduces risk for substance use disorder. Pediatrics 104:e20, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biederman J: Pharmacotherapy for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) decreases the risk for substance abuse: findings from a longitudinal follow-up of youths with and without ADHD. J Clin Psychiatry 64(Suppl 11):3–8, 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biederman J, Ball SW, Monuteaux MC, Mick E, Spencer TJ, McCreary M, Cote M, Faraone SV: New insights into the comorbidity between ADHD and major depression in adolescent and young adult females. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 47:426–434, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohnert AS, Ilgen MA, Ignacio RV, McCarthy JF, Valenstein M, Blow FC: Risk of death from accidental overdose associated with psychiatric and substance use disorders. Am J Psychiatry 169:64–70, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boland H, DiSalvo M, Fried R, Woodworth KY, Wilens T, Faraone SV, Biederman J: A literature review and meta-analysis on the effects of ADHD medications on functional outcomes. J Psychiatr Res 123:21–30, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrà G, Bartoli F, Galanter M, Crocamo C: Untreated depression and non-medical use of prescription pain relievers: Findings from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health 2008–2014. Postgrad Med 131:52–59, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang Z, Lichtenstein P, Halldner L, D'Onofrio B, Serlachius E, Fazel S, Langstrom N, Larsson H: Stimulant ADHD medication and risk for substance abuse. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 55:878–885, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton WM, Cottler LB, Abdallah AB, Phelps DL, Spitznagel EL, Horton JC: Substance dependence and other psychiatric disorders among drug dependent subjects: Race and gender correlates. Am J Addict 9:113–125, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran GM, Sullivan G, Williams K, Han X, Allee E, Kotrla KJ: The association of psychiatric comorbidity and use of the emergency department among persons with substance use disorders: An observational cohort study. BMC Emerg Med 8:17, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curry J, Silva S, Rohde P, Ginsburg G, Kennard B, Kratochvil C, Simons A, Kirchner J, May D, Mayes T, Feeny N, Albano AM, Lavanier S, Reinecke M, Jacobs R, Becker-Weidman E, Weller E, Emslie G, Walkup J, Kastelic E, Burns B, Wells K, March J: Onset of alcohol or substance use disorders following treatment for adolescent depression. J Consult Clin Psychol 80:299–312, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalsgaard S, Mortensen PB, Frydenberg M, Thomsen PH: ADHD, stimulant treatment in childhood and subsequent substance abuse in adulthood—A naturalistic long-term follow-up study. Addict Behav 39:325–328, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dulcan MK: Dulcan's Textbook of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association Publishing, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Esser MB, Guy GP Jr., Zhang K, Brewer RD: Binge drinking and prescription opioid misuse in the U.S., 2012–2014. Am J Prev Med 57:197–208, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esser MB, Sherk A, Liu Y, Naimi TS, Stockwell T, Stahre M, Kanny D, Landen M, Saitz R, Brewer RD: Deaths and years of potential life lost from excessive alcohol use—United States, 2011–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 69:1428–1433, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faraone SV, Biederman J, Wilens TE, Adamson J: A naturalistic study of the effects of pharmacotherapy on substance use disorders among ADHD adults. Psychol Med 37:1743, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fatseas M, Serre F, Swendsen J, Auriacombe M: Effects of anxiety and mood disorders on craving and substance use among patients with substance use disorder: An ecological momentary assessment study. Drug Alcohol Depend 187:242–248, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fothergill KE, Ensminger ME, Green KM, Crum RM, Robertson J, Juon HS: The impact of early school behavior and educational achievement on adult drug use disorders: A prospective study. Drug Alcohol Depend 92:191–199, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein BI, Strober M, Axelson D, Goldstein TR, Gill MK, Hower H, Dickstein D, Hunt J, Yen S, Kim E, Ha W, Liao F, Fan J, Iyengar S, Ryan ND, Keller MB, Birmaher B: Predictors of first-onset substance use disorders during the prospective course of bipolar spectrum disorders in adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 52:1026–1037, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez G, Rosenheck RA: Outcomes and service use among homeless persons with serious mental illness and substance abuse. Psychiatr Serv 53:437–446, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groenman AP, Janssen TWP, Oosterlaan J: Childhood psychiatric disorders as risk factor for subsequent substance abuse: A meta-analysis. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 56:556–569, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammerness P, Petty C, Faraone SV, Biederman J: Do stimulants reduce the risk for alcohol and substance use in youth with ADHD? A secondary analysis of a prospective, 24-month open-label study of osmotic-release methylphenidate. J Atten Disord 21:71–77, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han B, Compton WM, Blanco C, DuPont RL: National trends in substance use and use disorders among youth. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 56:747–754.e3, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harty SC, Ivanov I, Newcorn JH, Halperin JM: The impact of conduct disorder and stimulant medication on later substance use in an ethnically diverse sample of individuals with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in childhood. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 21:331–339, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katusic SK, Barbaresi WJ, Colligan RC, Weaver AL, Leibson CL, Jacobsen SJ: Psychostimulant treatment and risk for substance abuse among young adults with a history of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A population-based, birth cohort study. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 15:764–776, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC: The epidemiology of dual diagnosis. Biol Psychiatry 56:730–737, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khantzian EJ: The self-medication hypothesis of substance use disorders: A reconsideration and recent applications. Harvard Rev Psychiatry 4:231–244, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kronenberg LM, Slager-Visscher K, Goossens PJJ, van den Brink W, van Achterberg T: Everyday life consequences of substance use in adult patients with a substance use disorder (SUD) and co-occurring attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) or autism spectrum disorder (ASD): A patient's perspective. BMC Psychiatry 14:264, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert NM, Hartsough CS: Prospective study of tobacco smoking and substance dependencies among samples of ADHD and non-ADHD participants. J Learn Disabl 31:533–544, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert N: Stimulant treatment as a risk factor for nicotine use and substance abuse. In: Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disroder: State of the Science; Best Practices. Edited by Jensen PS, Cooper J, Vol 18. Kingston, NJ: Civic Research Institute, 2002, pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Levy S, Katusic SK, Colligan RC, Weaver AL, Killian JM, Voigt RG, Barbaresi WJ: Childhood ADHD and risk for substance dependence in adulthood: A longitudinal, population-based study. PLoS One 9:e105640, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannuzza S, Klein RG, Moulton JL, III: Does stimulant treatment place children at risk for adult substance abuse? A controlled, prospective follow-up study. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 13:273–282, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannuzza S, Klein RG, Truong NL, Moulton JL, III, Roizen ER, Howell KH, Castellanos FX: Age of methylphenidate treatment initiation in children with ADHD and later substance abuse: Prospective follow-up into adulthood. Am J Psychiatry 165:604–609, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe SE, Dickinson K, West BT, Wilens TE: Age of onset, duration, and type of medication therapy for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and substance use during adolescence: A Multi-Cohort National Study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 55:479–486, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas KR, McClair VL: Epidemiology of substance use disorders. Hum Genet 131:779–789, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell JD, Brown ES, Rush AJ: Comorbid disorders in patients with bipolar disorder and concomitant substance dependence. J Affect Disord 102:281–287, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina BS, Hinshaw SP, Eugene Arnold L, Swanson JM, Pelham WE, Hechtman L, Hoza B, Epstein JN, Wigal T, Abikoff HB, Greenhill LL, Jensen PS, Wells KC, Vitiello B, Gibbons RD, Howard A, Houck PR, Hur K, Lu B, Marcus S: Adolescent substance use in the multimodal treatment study of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (MTA) as a function of childhood ADHD, random assignment to childhood treatments, and subsequent medication. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 52:250–263, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oquendo MA, Currier D, Liu SM, Hasin DS, Grant BF, Blanco C: Increased risk for suicidal behavior in comorbid bipolar disorder and alcohol use disorders: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC). J Clin Psychiatry 71:902–909, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paternite CE, Loney J, Salisbury H, Whaley MA: Childhood inattention-overactivity, aggression, and stimulant medication history as predictors of young adult outcomes. J Child and Adolesc Psychopharmacol 9:169–184, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen L, Jeppesen P, Thorup A, Ohlenschlaeger J, Krarup G, Ostergård T, Jørgensen P, Nordentoft M: Substance abuse and first-episode schizophrenia-spectrum disorders. The Danish OPUS trial. Early Interv Psychiatry 1:88–96, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poudel A, Gautam S: Age of onset of substance use and psychosocial problems among individuals with substance use disorders. BMC Psychiatry 17:10, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn PD, Chang Z, Hur K, Gibbons RD, Lahey BB, Rickert ME, Sjolander A, Lichtenstein P, Larsson H, D'Onofrio BM: ADHD medication and substance-related problems. Am J Psychiatry 174:877–885, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen K, Palmstierna T, Levander S: Differences in psychiatric problems and criminality between individuals treated with central stimulants before and after adulthood. J Atten Disord 23:173–180, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saatcioglu O, Yapici A, Cakmak D: Quality of life, depression and anxiety in alcohol dependence. Drug Alcohol Rev 27:83–90, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trucco EM: A review of psychosocial factors linked to adolescent substance use. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 196:172969, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner MA, Boden JM, Smith-Hamel C, Mulder RT: Outcomes for 236 patients from a 2-year early intervention in psychosis service. Acta Psychiatr Scand 120:129–137, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Upadhyay N, Chen H, Mgbere O, Bhatara VS, Aparasu RR: The impact of pharmacotherapy on substance use in adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: Variations across subtypes. Subst Use Misuse 52:1266–1274, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Jones EB, Einstein EB, Wargo EM: Prevention and treatment of opioid misuse and addiction: A review prevention and treatment of opioid misuse and addictionprevention and treatment of opioid misuse and addiction. JAMA Psychiatry 76:208–216, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilens T: Does the medicating ADHD increase or decrease the risk for later substance abuse?. Rev Bras Psiquiatr 25:127–128, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilens T, Adamson J, Sgambati S, Whitley J, Santry A, Monuteaux MC, Biederman J: Do individuals with ADHD self-medicate with cigarettes and substances of abuse? Results from a controlled family study of ADHD. Am J Addict 16:14–23, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilens TE, Adamson J, Monuteaux MC, Faraone SV, Schillinger M, Westerberg D, Biederman J: Effect of prior stimulant treatment for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder on subsequent risk for cigarette smoking and alcohol and drug use disorders in adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 162:916–921, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilens TE, Biederman J, Martelon M, Zulauf C, Anderson JP, Carrellas NW, Yule A, Wozniak J, Fried R, Faraone SV: Further evidence for smoking and substance use disorders in youth with bipolar disorder and comorbid conduct disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 77:1420–1427, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilens TE, Martelon M, Anderson JP, Shelley-Abrahamson R, Biederman J: Difficulties in emotional regulation and substance use disorders: A controlled family study of bipolar adolescents. Drug Alcohol Depend 132:114–121, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilens TE, Martelon M, Joshi G, Bateman C, Fried R, Petty C, Biederman J: Does ADHD predict substance-use disorders? A 10-year follow-up study of young adults with ADHD. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 50:543–553, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilens T, Isenberg B, Kaminski T, Lyons R, Quintero J: Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and transitional aged youth. Curr Psychiatry Rep 20:100, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilton G, Stewart LA: Outcomes of offenders with co-occurring substance use disorders and mental disorders. Psychiatr Serv 68:704–709, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winters KC, Lee S, Botzet A, Fahnhorst T, Realmuto GM, August GJ: A prospective examination of the association of stimulant medication history and drug use outcomes among community samples of ADHD youths. J Child Adolesc Subst Abuse 20:314–329, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yule AM, Carrellas NW, Fitzgerald M, McKowen JW, Nargiso JE, Bergman BG, Kelly JF, Wilens TE: Risk factors for overdose in treatment-seeking youth with substance use disorders. J Clin Psychiatry 79:3, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]