Abstract

A nested reverse transcriptase (RT) PCR assay detected mRNA of the salmonid pathogen Renibacterium salmoninarum in samples of RNA extracts of between 1 and 10 cells. Total RNA was extracted from cultured bacteria, Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.) kidney tissue and ovarian fluid seeded with the pathogen, and kidney tissue from both experimentally challenged and commercially raised fish. Following DNase treatment, extracted RNA was amplified by both RT PCR and PCR by using primers specific for the gene encoding the major protein antigen of R. salmoninarum. A 349-bp amplicon was detected by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and silver stain. Inactivation of cultured bacteria by rifampin or erythromycin produced a loss of nested RT PCR mRNA detection corresponding to a loss of bacterial cell viability determined from plate counts but no loss of DNA detection by PCR. In subclinically diseased fish, nested RT PCR identified similar levels of infected fish as determined by viable pathogen culture. Higher percentages of fish testing positive were generated by PCR, particularly in samples from fish previously subjected to antibiotic chemotherapy where 93% were PCR positive, but only 7% were nested RT PCR and culture positive. PCR can generate false-positive data from amplification of target DNA from nonviable pathogen cells. Therefore, nested RT PCR may prove useful for monitoring cultured Atlantic salmon for the presence of viable R. salmoninarum within a useful time frame, particularly samples from broodstock where antibiotic chemotherapy is used prior to spawning to reduce vertical pathogen transmission.

Bacterial kidney disease (BKD) caused by Renibacterium salmoninarum is a persistent disease affecting cultivated salmonids in Europe, Japan, and North and South America (reviewed in reference 10). The frequent occurrence of subclinically infected carrier fish and the currently available, less than completely effective, antibiotic chemotherapies undoubtedly contribute to this persistence. BKD transmission can occur horizontally from fish to fish or vertically from subclinically infected female fish to progeny via infected eggs (10).

Control of BKD is attempted through monitoring and culling of subclinically infected broodstock to prevent vertical transmission. Immunodiagnostic methods developed for this screening (8, 16, 29) lack the necessary sensitivity to identify many subclinical carrier fish (1, 12, 15). Culture of this fastidious bacterium on selective media is impractical due to the lengthy (many weeks [6]) incubation required before identification can be achieved.

More recently, sensitive PCR methods to detect DNA (7, 21, 26, 27) and reverse transcriptase (RT) PCR methods to detect rRNA (24) from R. salmoninarum in fish kidney tissue, ovarian fluid, and egg samples have been reported. However, it is becoming increasingly apparent that these methods can produce false-positive results through the amplification of target DNA (18, 25) or rRNA sequences (31) from nonviable bacteria. In Atlantic salmon intraperitoneally injected with formalin-treated Aeromonas salmonicida cells, PCR detected DNA from the dead bacteria in tissues of the live sampled fish for at least 16 weeks postinjection (17). With R. salmoninarum, this problem may be inflated by the use of antibiotic chemotherapy not only to treat fish during overt BKD outbreaks but also to routinely treat broodstock fish prior to spawning to reduce vertical transmission from subclinical fish. In a survey of such treated broodstock, only 4 to 5% of the PCR-positive ovarian fluid and kidney tissue samples were ultimately found to contain viable R. salmoninarum by culture (27). With PCR-positive samples not uncommonly representing 10 to 50% of the total broodstock samples assayed (27), it may become useful to identify those samples containing viable pathogen cells within a practical time frame.

Bacterial mRNA has a short half-life, usually measured in minutes (20), and its detection decreases comparatively quickly with a loss of bacterial cell viability (31). For this reason, the detection of bacterial mRNA has been investigated recently as a method to more quickly identify the presence of viable bacteria (4, 5, 19, 28, 31). This report describes a nested RT PCR assay to detect R. salmoninarum mRNA. A comparison between mRNA detection and R. salmoninarum cell viability was made in vitro in cultured bacteria inactivated by antibiotics and in situ in Atlantic salmon.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and cultivation.

The R. salmoninarum K2A2 strain, isolated from Atlantic salmon at a hatchery on the Margaree River, Nova Scotia, and kindly provided by Gilles Olivier, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Halifax, Nova Scotia, (14) was subcultured on selective kidney disease medium (SKDM) (2) agar at 15°C for 3 weeks. Confluent lawns of bacteria were washed off the agar plates in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Cell numbers were estimated by absorbance (an optical density at 660 nm of 1.0 corresponded to approximately 109 cells ml−1 from hemocytometer counts as previously reported [27]). Serial dilutions of the harvested bacteria in PBS were used to determine sensitivity of the nested RT PCR assay.

Other bacterial strains used (Escherichia coli ATCC 1103, Staphylococcus epidermidis ATCC 155, Micrococcus luteus ATCC 4698, Aeromonas salmonicida S-Rest. 80204 [33], and Vibrio ordalii B [13]) were subcultured as previously described (27) and harvested as above for specificity of the nested RT PCR assay.

Total RNA extraction from bacterial strains.

Harvested bacteria in PBS were centrifuged at 6,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. Cell pellets were suspended immediately in 200 μl of 20 mM sodium acetate, pH 5.5, and 1 mM EDTA followed by the addition of 20 μl of 10% (wt/vol) sodium dodecyl sulfate with mixing and 200 μl of phenol-chloroform equilibrated with water (1:1) with mixing. Yeast tRNA (10 μg) was added, and the mixture was agitated at 70°C for 10 min and centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C (23). The aqueous phase was collected, combined with 200 μl of TRIzol reagent (Gibco BRL Life Technologies Inc., Grand Island, N.Y.), mixed, and set at room temperature for 7 min. Chloroform (100 μl) was added, and the mixture was vortexed, set at room temperature for 7 min, and centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C. The aqueous phase was collected, combined with an equal volume of isopropanol, set at −20°C for 30 min, and centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C. The extracted RNA pellet was washed with 75% (vol/vol) ethanol and stored at −70°C until assayed.

Synthetic oligonucleotide primers.

Oligonucleotide primers were selected from the published gene sequence of the major protein antigen (9) produced by R. salmoninarum isolates from a wide geographic range (11) with the assistance of the Oligo software program (National Bioscience Inc., Plymouth, Minn.). The nucleotide sequences of the primers for reverse transcription of the specific mRNA species and preamplification of the cDNA were LP3 (5′TTACCCGATCCAGTTCCC-3′), reverse 3′-position 1483, and UPI (5′ATGTCGCAAGGTGAAGGG-3′), forward 5′-position 127. The primers used for the second amplification reaction (FL7 and RL11) were those previously reported (27). The oligonucleotides were synthesized by Interscience Inc. (Markham, Ontario, Canada).

Nested RT PCR assay to detect R. salmoninarum mRNA.

Extracted RNA pellets were air dried, suspended in 175 μl of sterile, distilled, deionized H2O, incubated at 57°C for 10 min, vortexed, and centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. Supernatant aliquots (15 μl) were treated with 10 U of RQ1 RNase-free DNase (Promega Corp., Madison, Wis.) in a total reaction volume of 50 μl, containing 40 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 3 mM MgCl2, 10 U of RNasin (Promega Corp.), and 1 mM dithiothreitol incubated at 37°C for 30 min. One microliter of 500 mM EDTA was added, and the reaction mixture was centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 1 min, placed at 90°C for 5 min to inactivate DNase, and placed on ice.

For RT PCR, the reaction volume of 50 μl contained 15 μl of the DNase-treated RNA extract, 0.1 μM (each) primers LP3 and UP1, 50 mM Tris-HCl, 75 mM KCl, 12 mM MgCl2, 10 mM dithiothreitol, 2 mM (each) nucleotide triphosphate, 10 U of RNasin, 10 U of Taq polymerase (Gibco BRL Life Technologies Inc.), and 200 U of Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (Gibco BRL Life Technologies Inc.). The reaction mixture was allowed to reach 37°C on a PTC-100 programmable thermal controller (MJ Research Inc., Watertown, Mass.) before addition of reverse transcriptase. The incubation conditions were 37°C for 62 min for RT followed by 95°C for 5 min and 20 cycles of 95°C for 1.5 min (denaturing), 55°C for 1.5 min (annealing), 72°C for 2 min (extension), and 72°C for 10 min for PCR.

For the second amplification, the reaction volume of 50 μl contained 15 μl of the preamplification product, 0.2 μM (each) primers FL7 and RL11 (27), 5 μl of 10× PCR buffer (Gibco BRL Life Technologies Inc.), 0.1 mM (each) nucleotide triphosphate, 2% (vol/vol) formamide, 0.001% (wt/vol) gelatin, and 2 U of Taq polymerase. The thermal cycling conditions were 94°C for 5 min and 45 cycles of 93°C for 1 min (denaturing), 60°C for 1 min (annealing), 72°C for 30 s (extension), and 72°C for 2 min. RT was omitted from the first reaction for DNase-digested RNA extract controls to ensure DNA digestion. The nested RT PCR products (10-μl volumes) were subjected to 8% (wt/vol) polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis at a constant 200 V for 30 min by using a Mini Protean II electrophoresis apparatus (Bio-Rad Laboratories Ltd., Hercules, Calif.) and visualized by silver staining (Bio-Rad Laboratories Ltd.).

PCR assay to detect R. salmoninarum DNA.

DNA was extracted from bacterial cells as previously reported (27). PCR amplification was performed by using 50-μl volumes containing 10 μl of DNA extract, 0.1 μM (each) primers FL7 and RL11 (26), 5 μl of 10× PCR buffer, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM (each) nucleotide triphosphate, 2% (vol/vol) formamide, 0.001% (wt/vol) gelatin, and 1.5 U of Taq polymerase. Thermal cycling conditions were the same as those used for the second PCR amplification reaction above, except that 35 cycles were used. The PCR products were subjected to polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and visualized by silver staining as described above.

Sensitivity of nested RT PCR assay of seeded Atlantic salmon kidney tissue and ovarian fluid.

Kidneys were removed from Atlantic salmon, homogenized (10% [wet wt/vol]), and stored at −20°C as reported previously (15). Ovarian fluid was collected from gravid female fish and stored at −20°C as reported previously (12). Aliquots (50 μl) of presumed-negative samples (by culture on SKDM agar and PCR [27]) were seeded with serial dilutions of cultivated R. salmoninarum cells. Seeded kidney homogenate samples were washed twice with 1 ml of PBS by centrifugation at 13,000 × g for 30 s and suspended in 50 μl of PBS. Total RNA was extracted from the seeded ovarian fluid and washed kidney homogenate samples and assayed by nested RT PCR as described above.

Antibiotic inactivation of cultured R. salmoninarum cells.

R. salmoninarum was subcultured in 250-ml Erlenmeyer flasks containing 100 ml of Mueller-Hinton broth containing 0.1% (wt/vol) cysteine hydrochloride (MHB-C) (3) at 15°C and 150 rpm on a Psychrotherm environmental shaker (model G-26; New Brunswick Scientific Co. Inc., Edison, N.J.) and used to inoculate MHB-C with and without rifampin (final concentration, 10 μg ml−1) to a final cell concentration of approximately 106 ml−1. Samples (0.5 ml) of each incubated culture were removed at the times indicated for RNA extraction and nested RT PCR, DNA extraction and PCR (as described above), and culture of viable cells. For culture, samples were washed with and suspended in MHB-C broth. Aliquots (20 μl) of serial 10-fold dilutions of the washed cell samples were drop plated (15) in triplicate onto SKDM agar and Trypticase soy agar (TSA), and the number of CFU were determined after 3, 6, and 8 weeks incubation at 15°C. Growth on SKDM agar in the absence of growth on TSA was used to confirm colonies as R. salmoninarum (15). Similar experiments were carried out where erythromycin (final concentration, 200 μg ml−1) was used in place of rifampin.

Comparison of nested RT PCR, PCR, and culture to detect R. salmoninarum in kidney tissue from experimentally challenged and commercially raised Atlantic salmon.

For experimentally challenged fish, Atlantic salmon (weight, 25 to 50 g each) were acclimated and maintained at 10 to 11°C as previously described (22). Fish were injected intraperitoneally with approximately 107 CFU of R. salmoninarum K2A2 in 0.2 ml of PBS, the fins were clipped for identification, and 50 fish were placed into each of three tanks containing 50 unchallenged fish to initiate a low-level BKD infection in the cohabitant unchallenged fish. Any fish that died were removed daily and checked for internal clinical signs of BKD (10), and 10% were checked for R. salmoninarum by nested RT PCR, PCR, and culture from kidney tissue. Nested RT PCR and PCR were performed on 10% (wet wt/vol) kidney homogenates as described above. For culture, sterile cotton swabs were dipped into the kidney homogenate and swabbed onto the surface of SKDM agar and TSA plates, and the plates were checked for growth of R. salmoninarum after 6 weeks incubation at 15°C. At week 9 postchallenge, surviving fish challenged by intraperitoneal injection (only 7%) were removed from the tanks. At week 14 postchallenge, samples (10 fish from each tank) of the surviving fish challenged by cohabitation (95%) were sacrificed, and kidney tissue was assayed for R. salmoninarum by nested RT PCR, PCR, and culture. For culture, the number of R. salmoninarum CFU per gram wet weight of kidney tissue was determined by drop plating 20-μl aliquots of serial 10-fold dilutions of kidney homogenates in triplicate on SKDM agar and TSA plates and incubating the plates at 15°C for 6 weeks.

Samples of commercially raised Atlantic salmon from a sea cage site on the Bay of Fundy, New Brunswick, were also obtained and assayed for R. salmoninarum by nested RT PCR, PCR, and culture from kidney tissue.

RESULTS

Nested RT PCR assay to detect R. salmoninarum mRNA.

Several PCR assays specifically detecting target DNA from R. salmoninarum isolates from diverse geographic locations (7, 26, 27) have been based on the published sequence of the gene coding the 57-kDa protein (major soluble antigen) from the R. salmoninarum ATCC 33209 type strain (9) and suggest this gene is highly conserved. We have recently sequenced this gene from the R. salmoninarum K2A2 strain used here from bp 127 to 1500 and have found only two differences (a base change at bp 464 and an extra codon between bp 768 and 769) from the published sequence of the ATCC 33209 type strain (32). Therefore, nucleotide sequences for primers for reverse transcription of mRNA and PCR preamplification of cDNA were selected from the published sequence of this gene from the type strain, and PCR as previously reported (27) was used to amplify a 349-bp segment of the cDNA.

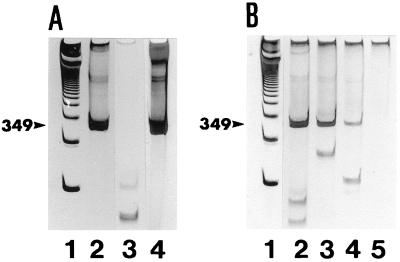

Nested RT PCR of DNase-treated RNA extracts from R. salmoninarum K2A2 consistently produced the expected 349-bp amplification product (Fig. 1A, lane 2). Control reactions (RT omitted from the first reaction) consistently failed to produce a detectable 349-bp amplification product, showing that any contaminating R. salmoninarum DNA in the RNA extracts was destroyed (Fig. 1A, lane 3). Lower-molecular-mass bands (of lengths less than 349 bp) were variably seen in both test and control samples (Fig. 1A, lane 2, and Fig. 1B, lanes 2 to 4) but did not hinder interpretation of the results and likely represented residual primers and/or dimerization products of the primers (30).

FIG. 1.

Polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis of nested RT PCR products amplified from RNA extracts from Atlantic salmon (S. salar L.) kidney homogenate (10% [wt/vol]) samples seeded with R. salmoninarum cells. (A) Nested RT PCR amplification products from RNA extract of 1.6 × 107 R. salmoninarum cells (lane 2), control PCR amplification products from the RNA extract used in lane 2 (lane 3), and PCR amplification products from DNA extract of 1.6 × 107 R. salmoninarum cells (lane 4). (B) Nested RT PCR amplification products from RNA extracts of 1.6 × 102 (lane 2), 1.6 × 101 (lane 3), 1.6 (lane 4), and 0 (unseeded sample) (lane 5) R. salmoninarum cells. Lanes 1 (A and B) contained 1-kb DNA ladder (Gibco Life Technologies Inc.). Arrowheads indicate the position of the 349-bp DNA product.

Sensitivity and specificity of the nested RT PCR assay.

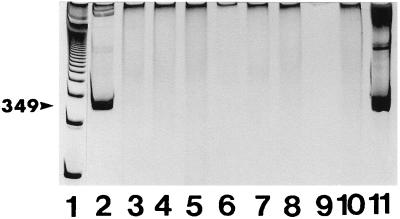

To examine the sensitivity of the nested RT PCR assay, total RNA was extracted from presumed-negative (by culture and PCR) Atlantic salmon kidney tissue homogenate (10% [wet wt/vol]) and ovarian fluid seeded with serial dilutions of cultivated R. salmoninarum cells. The intensity of the stained 349-bp amplification product detected on polyacrylamide gels decreased with the concentration of R. salmoninarum cells in the seeded samples but was consistently detected by the assay with aliquots of the DNase-treated RNA extracts of between 1 and 10 R. salmoninarum cells (Fig. 1B). The nested RT PCR assay of total RNA extracts of cultures of a variety of other bacteria tested did not produce a positive result, as no amplification product of the appropriate size was detected (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Polyacrylamide gel analysis of nested RT PCR products amplified from RNA extracts from R. salmoninarum cells and other cultivated bacterial strains. Total RNA was extracted from bacterial suspensions in PBS and treated with DNase, and 15-μl samples containing RNA extracted from 106 bacterial cells of R. salmoninarum K2A2 (lane 2), E. coli ATCC 11303 (lane 3), S. epidermidis ATCC 155 (lane 4), M. luteus ATCC 4698 (lane 5), V. ordalii B (lane 6), and A. salmonicida S. Rest. 80204 (lane 7) were subjected to nested RT PCR, electrophoresed, and stained as described in Materials and Methods. Lane 1 contained 1-kb DNA ladder. Control nested RT PCR products with PBS (lane 8) and H2O (lane 9) and control PCR products of the R. salmoninarum RNA extract used in lane 2 (lane 10) and PCR amplification products from R. salmoninarum DNA extract of 106 cells (lane 11) are also shown. Arrowhead indicates the position of the 349-bp DNA product.

Effect of antibiotic treatment on R. salmoninarum cell viability and mRNA detection.

To compare mRNA detection by nested RT PCR and cell viability by culture, R. salmoninarum cells were inoculated and incubated in MHB-C broth (3) and rifampin (10 μg ml−1 of broth) or erythromycin (200 μg ml−1 of broth). Viability was defined here as visible colonies produced from washed cell samples of the broth culture plated on SKDM agar (2) and incubated at 15°C for 8 weeks. Rifampin, an inhibitor of mRNA synthesis, and erythromycin, an inhibitor of protein synthesis, were chosen to inactivate the cells (20), as they would be less likely to directly cause destruction of existing mRNA in the cells than other inactivation methods, such as heat (31).

Growth of R. salmoninarum in MHB-C broth without antibiotics was evident by 2 days incubation from the increase in CFU observed from the broth samples plated on SKDM agar and scored at 3 weeks incubation at 15°C (data not shown). In MHB-C broth with rifampin, the initial cell sample (Table 1, 0 days incubation), which was subjected to brief exposure to the antibiotic before and during sampling, showed little effect on viability from the number of CFU of viable cells ultimately observed after 8 weeks incubation on SKDM agar and no obvious decrease in mRNA detection. However, visible formation of the colonies on SKDM agar was very slow compared to cell samples from MHB-C broth without rifampin, indicating some effect of the antibiotic. By day 1 of incubation, number of CFU had declined by approximately 1 log unit, and mRNA detection had declined by approximately 3 log units. Again, growth of the surviving cells into visible colonies on SKDM agar was very slow, and the decrease in mRNA detection may suggest that these surviving cells exposed to rifampin contained less target mRNA at the time of sampling from the broth. This may be due to an inhibition of mRNA synthesis and degradation of existing mRNA prior to cell death. Interestingly, some viable cells were observed from the broth with rifampin at 21 days incubation, at which time the number of CFU was approximately 3 log units lower, and the target mRNA detection was approximately 2 to 3 log units lower than in the initial (0-day incubation) broth sample. In contrast, there was no obvious change in the level of target DNA detection by PCR over the 21-day incubation period in cell samples from the MHB-C broth with rifampin, indicating that PCR detected DNA from nonviable cells.

TABLE 1.

Comparison of mRNA detection by nested RT PCR of RNA extracts, DNA detection by PCR of DNA extracts, and numbers of CFU resulting from the culture on SKDM agar of R. salmoninarum incubated in MHB-C broth containing rifampin

| Incubation time (days) | Results for:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNA and mRNA detection

|

CFU ml−1 after culture on SKDM ford:

|

|||||

| 0-time cell equivalenta | Nested RT PCRb | PCRc | 3 wk | 6 wk | 8 wk | |

| 0 | 104 | + | + | 2 × 105e | 8.8 × 105 | 1.1 × 106 |

| 103 | + | + | ||||

| 102 | + | + | ||||

| 10 | + | + | ||||

| 1 | − | − | ||||

| 1 | 104 | + | + | —f | 8.8 × 104 | 2.2 × 105 |

| 103 | − | + | ||||

| 102 | − | + | ||||

| 10 | − | + (w)g | ||||

| 1 | NPh | − | ||||

| 2 | 104 | + (w) | + | — | 4.0 × 104 | 6.4 × 104 |

| 21 | 104 | + | + | — | 8 × 102i | 1.5 × 103 |

| 103 | + (w) | + | ||||

| 102 | − | + | ||||

| 10 | NP | + | ||||

| 1 | NP | − | ||||

From R. salmoninarum inoculated to give a final concentration of approximately 106 cells ml−1 of MHB-C broth plus rifampin.

Detection of nested RT PCR amplified product on silver-stained polyacrylamide gels.

Detection of PCR amplified product on silver-stained polyacrylamide gels.

Washed cell samples taken from R. salmoninarum incubated in MHB-C broth containing 10 μg of rifampin per ml. Results in CFU recorded after 3, 6, and 8 weeks incubation at 15°C.

Comparatively very tiny, barely visible colonies by 3 weeks incubation.

—, no visible colonies (less than approximately 4 × 102 CFU ml−1).

w, weak reaction.

NP, not performed.

Not statistically significant, but shows presence of viable R. salmoninarum.

In MHB-C broth with erythromycin, growth of surviving cells similarly was very slow as seen by colony formation on SKDM agar after 8 weeks of incubation. Viability and mRNA detection declined more slowly in broth with erythromycin than in broth with rifampin, perhaps indicating a more bacteriostatic effect of erythromycin on R. salmoninarum and a lack of direct effect of the antibiotic on mRNA synthesis (Table 2). Some viable cells also remained in the broth with erythromycin after 21 days of incubation, at which time the number of CFU was approximately 3 log units lower and target mRNA detection was approximately 2 log units lower than the initial (0-day incubation) sample. However, no obvious decrease in target DNA detection by PCR was observed over the 21 days of incubation in broth with erythromycin. The very slow observed rate of visible colony formation by surviving cells exposed to rifampin or erythromycin may have implications for determining antibiotic minimum bactericidal concentrations for R. salmoninarum, where shorter incubation times (less than 3 weeks) on agar plates have been used to examine cell viability (3).

TABLE 2.

Comparison of mRNA detection by nested RT PCR of RNA extracts, DNA detection by PCR of DNA extracts, and numbers of CFU resulting from the culture on SKDM agar of R. salmoninarum incubated in MHB-C broth containing erythromycin

| Incubation time (days) | Results for:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNA and mRNA detection

|

CFU ml−1 after 8 wk culture on SKDMc | |||

| 0-time cell equivalenta | Nested RT PCRb | PCRb | ||

| 0 | 5 × 104 | + | + | 5 × 106 |

| 5 × 103 | + | + | ||

| 5 × 102 | + | + | ||

| 50 | + | + | ||

| 5 | + | − | ||

| 0.5 | − | − | ||

| 1 | 5 × 104 | + | + | 5 × 106 |

| 5 × 103 | + | + | ||

| 5 × 102 | + | + | ||

| 50 | + | + | ||

| 5 | + | − | ||

| 0.5 | − | − | ||

| 9 | 5 × 104 | + | + | 1.2 × 105 |

| 21 | 5 × 104 | + | + | 1.5 × 103 |

| 5 × 103 | + | + | ||

| 5 × 102 | + | + | ||

| 50 | − | + | ||

| 5 | − | − | ||

| 0.5 | − | − | ||

From R. salmoninarum inoculated to give a final concentration of approximately 4.9 × 106 cells ml−1 of MHB-C broth + erythromycin.

Under same conditions as described in Table 1.

Washed cell samples taken from R. salmoninarum incubated in MHB-C broth containing 200 mg of erythromycin per ml.

Comparison of culture, nested RT PCR, and PCR for detection of R. salmoninarum in experimentally challenged Atlantic salmon.

A low-level BKD infection was established in previously unchallenged fish by cohabitation for 9 weeks with fish injected intraperitoneally with R. salmoninarum, by which time most (93%) of the intraperitoneally injected fish had died. All mortalities displayed typical symptoms of BKD (e.g., white granulomatous lesions in kidney tissue [10]), and those mortalities checked (14 fish) were positive for R. salmoninarum by cultivation on SKDM agar, nested RT PCR assay, and PCR assay from kidney tissue.

Most of the live sampled fish challenged by cohabitation and assayed from kidney tissue on week 14 postchallenge were culture positive (66%) with low numbers of R. salmoninarum CFU per gram (wet wt) of kidney tissue (Table 3). The detection limit of the culture method used as the indicator for viable pathogen cells was approximately 5 × 102 to 5 × 103 CFU g−1 of kidney tissue. If the detection limits used for nested RT PCR and PCR did not exceed the detection limit for culture, then culture could be used to evaluate the nested RT PCR and PCR methods for detection of viable and/or dead pathogen cells. Therefore, the detection limits of the nested RT PCR and PCR methods, as used, were between approximately 7 × 103 and 7 × 104 and between 4 × 103 and 4 × 104 seeded bacterial cell equivalents g−1 kidney tissue, respectively.

TABLE 3.

Results of culture on SKDM agar, nested RT PCR of RNA extracts, and PCR of DNA extracts from kidney tissue from representative live Atlantic salmon challenged with R. salmoninarum by cohabitation

| Fish no. | CFU g−1 (wet wt) of kidneya | Nested RT PCR assayb | PCR assayc |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1G | >5 × 107 | + | + |

| 2J | >5 × 107 | + | + |

| 3H | 2.4 × 106 | + | NPd |

| 3J | 1.6 × 106 | + | NP |

| 3G | 8.5 × 105 | + | NP |

| 3D | 3.4 × 105 | + | NP |

| 2D | 2.0 × 105 | + | NP |

| 3I | 3.5 × 104 | + | NP |

| 2B | 3.0 × 104 | − | + |

| 3A | 2.1 × 104 | + | + |

| 1I | 2.1 × 104 | + | + |

| 2F | 1.2 × 104 | + (weak) | + |

| 3B | 9.2 × 103 | + (weak) | NP |

| 3C | 1.0 × 103 | − | NP |

| 1C | NDe | + (weak) | NP |

| 2C | ND | + (weak) | + |

| 1D | ND | − | + |

| 2A | ND | − | + |

| 2E | ND | − | + |

| 2H | ND | − | + |

| 1B | ND | − | − |

| 2G | ND | − | − |

After 6 weeks incubation at 15°C on SKDM agar (2).

Detection of nested RT PCR amplified product on silver-stained polyacrylamide gels.

Detection of PCR amplified product on silver-stained polyacrylamide gels.

NP, not performed.

ND, not detected.

All kidney samples from challenged fish found to contain greater than 3 × 104 CFU g−1 by culture tested positive by nested RT PCR (Table 3). Of eight kidney samples containing 5 × 102 to 3 × 104 CFU g−1, four produced positive results by nested RT PCR, which may indicate the range where the nested RT PCR detection limit was being exceeded. Most kidney samples (8 of 10) testing negative by culture also tested negative by nested RT PCR, but two culture-negative kidney samples tested weakly positive by nested RT PCR. Some of the differences between nested RT PCR and culture may have been caused by chance sampling from kidney homogenates containing low numbers of unequally distributed viable R. salmoninarum cells, such that not all aliquots from the same sample contained viable pathogen cells.

A selected number of kidney samples from the live, sampled, challenged fish also were assayed by PCR (Table 3). While the culture-positive kidney samples tested were positive by PCR, a number of the culture-negative and nested RT PCR-negative kidney samples also produced positive results by PCR.

R. salmoninarum detection in commercially raised Atlantic salmon.

Subclinical live fish from a commercial sea cage site in the Bay of Fundy with a recent history of BKD were sampled in May 1997. One sample (16 fish) was obtained from a sea cage of untreated fish, and the other (15 fish) was obtained from a separate sea cage of fish previously subjected to antibiotic chemotherapy (oxytetracycline for 21 days in May and November 1996). Kidney tissue from these fish was assayed in the same manner as tissue from the experimentally challenged fish, except that no serial dilutions of the kidney homogenate samples were plated for culture.

Of the untreated fish, 11 were culture positive and 10 were nested RT PCR positive (Table 4). Some of the culture-positive fish (3) containing very low numbers of R. salmoninarum CFU (1 to 6 colonies per plate, less than approximately 3 × 103 CFU g−1 of kidney tissue) were nested RT PCR negative, and some of the culture-negative fish (2) produced weak-positive nested RT PCR reactions. Again, this suggested the range where the detection limits of the assays, as used, may have been exceeded and where chance sampling of different aliquots from the same kidney sample may or may not have contained viable pathogen cells. However, all 16 fish tested were PCR positive. These results were similar to those observed by using the subclinical challenged fish. With the fish sample previously subjected to antibiotic chemotherapy, only one fish was culture-positive (one colony) and one fish was weakly RT PCR positive, but 14 of the 15 fish were PCR positive, suggesting the PCR was detecting target DNA from nonviable R. salmoninarum cells.

TABLE 4.

Results of culture on SKDM agar, nested RT PCR of RNA extracts, and PCR of DNA extracts from kidney tissue from samples of commercially raised, sea cage Atlantic salmon

| No. of fish sampled | Assay results ofa:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Culture | Nested RT PCR | PCR | |

| Untreated | |||

| 8 | +b | + | + |

| 3 | +c | − | + |

| 2 | − | + (weak) | + |

| 3 | − | − | + |

| Prior antibiotic chemotherapyd | |||

| 1 | +c | − | + |

| 1 | − | + (weak) | + |

| 12 | − | − | + |

| 1 | − | − | − |

Under same conditions as described in Table 2.

All samples with ≥10 colonies per plate.

All samples with 1 to 6 colonies per plate.

Sampled in May 1997 from fish receiving oxytetracycline treatment (21 days) in May and November 1996.

DISCUSSION

Recent investigations have described the potential use of mRNA detection by RT PCR methods to identify low numbers of viable bacterial cells of human pathogens such as Listeria monocytogenes (19) and Vibrio cholerae (5) in complex environments such as food. These and other reports (4, 28, 31) indicate that, due to the short half-lives of bacterial mRNAs, detection of mRNA may be a good indicator of the presence of viable cells or cells that have died shortly before the time of sampling. Here, the nested RT PCR assay to detect mRNA from the gene coding the major protein antigen of the salmonid fish pathogen R. salmoninarum detected target mRNA from between 1 and 10 pathogen cells in aliquots extracted from seeded Atlantic salmon kidney tissue homogenate or ovarian fluid. The assay was specific and could be completed within 72 h.

Incubation of R. salmoninarum cells in MHB-C broth with rifampin indicated a relationship between mRNA detection by the nested RT PCR assay and R. salmoninarum cell viability. The significant decrease in mRNA detection (99 to 99.9%) in the broth samples corresponding to a significant loss of cell viability (90 to 99.9%) as determined from colony formation after 8 weeks incubation of the broth samples on SKDM agar. Similar results were obtained when R. salmoninarum was incubated in MHB-C broth with erythromycin. The failure to observe any loss of target DNA detection by PCR even after 21 days incubation in the broths with antibiotics showed that PCR amplified target DNA from dead bacterial cells. It is known that detection of DNA by PCR or rRNA by RT PCR may not distinguish between living and dead organisms due to the greater stability of these cellular components (18, 25, 31).

To examine these relationships in situ in Atlantic salmon, a low-level BKD infection was experimentally established in fish, and kidney tissue from live sampled fish was assayed. The detection limits, as used, for the nested RT PCR and PCR assays did not exceed the detection limit of the culture method. Therefore, culture was used to evaluate the nested RT PCR and PCR methods for detection of viable and/or dead pathogen cells. The majority of culture-positive samples tested positive by nested RT PCR, and the majority of culture-negative samples tested negative by nested RT PCR. In some kidney samples, differences between culture and nested RT PCR results were observed where culture results indicated very low numbers of CFU g−1 of kidney tissue or nested RT PCR reactions were weak. The results suggested that these latter samples contained very low numbers of viable pathogen cells, perhaps where detection limits of the assays, as used, were being exceeded and/or where, due to chance sampling, different aliquots from the same kidney homogenate may or may not have contained viable pathogen cells. In contrast, while PCR identified all culture-positive kidney samples tested, it also produced positive results for many kidney samples which were negative by culture and nested RT PCR, suggesting that PCR amplified target DNA from nonviable R. salmoninarum cells in the kidney tissue.

Results similar to those obtained with the experimentally infected fish were produced when a live sample of untreated, commercially raised, sea cage Atlantic salmon with a recent history of BKD were subjected to the same assays. However, an examination of a second live sample of fish from a separate sea cage at the same site, which had previously been subjected to antibiotic chemotherapy, produced a much lower number of fish testing positive by culture and nested RT PCR than was observed for the untreated fish sample. In contrast, PCR produced a number of fish testing positive which was as high as that observed from the untreated fish sample. The results of the fish analyses indicated that the nested RT PCR detection of R. salmoninarum mRNA is a better indicator of the presence of viable pathogen cells in kidney samples from Atlantic salmon and that PCR produced significant false-positive data through amplification of target DNA from nonviable pathogen cells particularly evident in fish subjected to antibiotic chemotherapy. The results also indicated a potential use for the nested RT PCR assay as a method to more quickly assess the efficacy of any antibiotic chemotherapy.

The detection limit used for the nested RT PCR assay of kidney tissue for experimental comparison purposes most likely contributed to its failure to identify some of the culture-positive kidney samples containing low numbers of viable R. salmoninarum cells. However, this detection sensitivity can be increased greater than 10-fold (i.e., tested to approximately 5 × 102 to 5 × 103 cell equivalents g−1 of kidney tissue) without affecting the assay. There are components of kidney tissue which may have an inhibitory effect on the assay (27) at higher concentrations of kidney tissue extracts which are presently under investigation. However, the data show that the nested RT PCR assay has potential use as a sensitive assay to monitor Atlantic salmon kidney tissue and ovarian fluid for the presence of viable R. salmoninarum within a practical time frame, especially where broodstock are routinely subjected to antibiotic chemotherapy prior to spawning to reduce vertical pathogen transmission.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported in part by a grant from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada and in part by a grant from the Huntsman Marine Science Centre.

We gratefully acknowledge the capable technical assistance of L. Hutchins and K. Melville (Research and Productivity Council of New Brunswick).

REFERENCES

- 1.Armstrong R D, Martin S W, Evelyn T P T, Hicks B, Dorward W J, Ferguson H W. A field evaluation of an indirect fluorescent antibody-based broodstock screening test used to control the vertical transmission of Renibacterium salmoninarum in chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) Can J Vet Res. 1989;53:385–389. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Austin B, Embly T M, Goodfellow M. Selective isolation of Renibacterium salmoninarum. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1983;17:111–114. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bandin I, Santos Y, Toranzo A E, Barja J L. MICs and MBCs of chemotherapeutic agents against Renibacterium salmoninarum. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1991;35:1011–1013. doi: 10.1128/aac.35.5.1011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bej A K, Mahbubani M H, Atlas R M. Detection of viable Legionella pneumophila in water by polymerase chain reaction and gene probe methods. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:597–600. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.2.597-600.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bej A K, Ng W Y, Morgan S, Jones D D, Mahbubani M H. Detection of viable Vibrio cholerae by reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) Mol Biotechnol. 1996;5:1–10. doi: 10.1007/BF02762407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benediktsdottir E, Helgason S, Gudmundsdottir S. Incubation time for the cultivation of Renibacterium salmoninarum from Atlantic salmon, Salmo salar L., broodfish. J Fish Dis. 1991;14:97–102. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown L L, Iwama G K, Evelyn T P T, Nelson W S, Levine R P. Use of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to detect DNA from Renibacterium salmoninarum within individual salmonid eggs. Dis Aquat Org. 1994;18:165–171. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bullock G L, Stuckey H M. Fluorescent antibody identification and detection of the Corynebacterium causing kidney disease of salmonids. J Fish Res Board Can. 1975;32:224–227. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chien M S, Gilbert T L, Huang C, Landolt M L, O’Hara P J, Winton J R. Molecular cloning and sequence analysis of the gene coding for the 57-kDa major soluble antigen of the salmonid fish pathogen Renibacterium salmoninarum. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1992;26:259–266. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(92)90414-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Evenden A J, Grayson T H, Gilpin M L, Munn C B. Renibacterium salmoninarum and bacterial kidney disease—the unfinished jigsaw. Annu Rev Fish Dis. 1993;1:87–104. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Getchell R G, Rohovec J S, Fryer J L. Comparison of Renibacterium salmoninarum isolates by antigenic analysis. Fish Pathol. 1985;20:149–159. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Griffiths S G, Liska K, Lynch W H. Comparison of kidney tissue and ovarian fluid from broodstock Atlantic salmon for the detection of Renibacterium salmoninarum and use of SKDM broth culture with Western blotting to increase detection in ovarian fluid. Dis Aquat Org. 1996;24:3–9. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Griffiths S G, Lynch W H. Characterization of Aeromonas salmonicida variants with altered cell surfaces and their use in studying surface protein assembly. Arch Microbiol. 1990;154:308–312. doi: 10.1007/BF00248973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Griffiths S G, Lynch W H. Instability of the major soluble antigen produced by Renibacterium salmoninarum. J Fish Dis. 1991;14:55–66. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Griffiths S G, Olivier G, Fildes J, Lynch W H. Comparison of Western blot, direct fluorescent antibody and drop-plate culture methods for the detection of Renibacterium salmoninarum in Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.) Aquaculture. 1991;97:117–129. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gudmundsdottir S, Benediktsdottir E, Helgason S. Detection of Renibacterium salmoninarum in salmonid kidney samples: a comparison of results using double sandwich ELISA and isolation on selective medium. J Fish Dis. 1993;16:185–195. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoie S, Heum M, Thoresen O F. Detection of Aeromonas salmonicida by polymerase chain reaction in Atlantic salmon vaccinated against furunculosis. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 1996;6:199–206. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Josephson K L, Gerba C P, Pepper I L. Polymerase chain reaction detection of nonviable bacterial pathogens. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:3513–3515. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.10.3513-3515.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klein P G, Juneja V K. Sensitive detection of viable Listeria monocytogenes by reverse-transcription PCR. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:4441–4448. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.11.4441-4448.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kushner S R. mRNA decay. In: Neidhardt F C, Curtiss R, Ingraham J L, Lin E C C, Low K B, Magasanik B, Reznikoff W S, Riley M, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. Vol. 1. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1996. pp. 849–860. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leon G, Maulen N, Figueroa J, Villanueva J, Rodriguez C, Vera M I, Krauskopf M. A PCR-based assay for the identification of the fish pathogen Renibacterium salmoninarum. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1994;115:131–136. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1994.tb06627.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lovely J E, Cabo C, Griffiths S G, Lynch W H. Detection of Renibacterium salmoninarum infection in asymptomatic Atlantic salmon. J Aquat Anim Health. 1994;6:126–132. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Magni C, Marini P, Mendoza D. Extraction of RNA from gram-positive bacteria. BioTechniques. 1995;19:880–884. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Magnusson H B, Fridjonsson O H, Andresson O S, Benediktsdottir E, Gudmundsdottir S, Andresdottir V. Renibacterium salmoninarum, the causative agent of bacterial kidney disease in salmonid fish, detected by nested reverse transcription-PCR of 16S rRNA sequences. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:4580–4583. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.12.4580-4583.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Masters C I, Shallcross J A, Mackey B M. Effect of stress treatments on the detection of Listeria monocytogenes and enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli by the polymerase chain reaction. J Appl Bacteriol. 1994;77:73–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1994.tb03047.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McIntosh D, Meaden P G, Austin B. A simplified PCR-based method for the detection of Renibacterium salmoninarum utilizing preparations of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss, Walbaum) lymphocytes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:3929–3932. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.11.3929-3932.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miriam A, Griffiths S C, Lovely J E, Lynch W H. PCR and probe-PCR assays to monitor broodstock Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.) ovarian fluid and kidney tissue for the presence of DNA of the fish pathogen Renibacterium salmoninarum. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1322–1326. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.6.1322-1326.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Patel B K R, Banjerjee D K, Butcher P D. Determination of Mycobacterium leprae by polymerase chain reaction amplification of 71-kDa heat shock protein mRNA. J Infect Dis. 1993;168:799–800. doi: 10.1093/infdis/168.3.799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rockey D D, Gilkey L L, Wiens G D, Kaattari S L. Monoclonal antibody-based analysis of the Renibacterium salmoninarum p57 protein in spawning chinook and coho salmon. J Aquat Anim Health. 1991;3:23–30. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rychlik W. Selection of primers for polymerase chain reaction. In: White B A, editor. Methods in molecular biology. Vol. 15. Totowa, N.J: Hamana Press; 1993. pp. 31–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sheridan G E C, Masters C I, Shallcross J A, Mackey B M. Detection of mRNA by reverse transcription-PCR as an indicator of viability in Escherichia coli cells. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:1313–1318. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.4.1313-1318.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Simard, N., and W. H. Lynch. Unpublished data.

- 33.Wood S C, McCashion R N, Lynch W H. Multiple low-level antibiotic resistance in Aeromonas salmonicida. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1986;29:992–996. doi: 10.1128/aac.29.6.992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]