Abstract

To control the pH during antimicrobial peptide (nisin) production by a lactic acid bacterium, Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis (ATCC11454), a novel method involving neither addition of alkali nor a separation system such as a ceramic membrane filter and electrodialyzer was developed. A mixed culture of L. lactis and Kluyveromyces marxianus, which was isolated from kefir grains, was utilized in the developed system. The interaction between lactate production by L. lactis and its assimilation by K. marxianus was used to control the pH. To utilize the interaction of these microorganisms to maintain high-level production of nisin, the kinetics of growth of, and production of lactate, acetate, and nisin by, L. lactis were investigated. The kinetics of growth of and lactic acid consumption by K. marxianus were also investigated. Because the pH of the medium could be controlled by the lactate consumption of K. marxianus and the specific lactate consumption rate of K. marxianus could be controlled by changing the dissolved oxygen (DO) concentration, a cascade pH controller coupled with DO control was developed. As a result, the pH was kept constant because the lactate level was kept low and nisin accumulated in the medium to a high level compared with that attained using other pH control strategies, such as with processes lacking pH control and those in which pH is controlled by addition of alkali.

Nisin is an antimicrobial peptide produced by certain Lactococcus species. Nisin has been accepted as a safe and natural preservative in more than 50 countries (4, 10, 12). This peptide inhibits the vegetative growth of a range of gram-positive bacteria. Since, in particular, nisin inhibits the food-borne pathogens Listeria monocytogenes, Staphylococcus aureus, and psychrotrophic enterotoxigenic Bacillus cereus, the effectiveness of nisin as a food preservative against these organisms under various preservation conditions has been investigated in detail (2, 20, 25).

Not only the use of nisin-producing lactic acid bacteria (LAB) as a fermentation starter culture but also the direct addition of nisin to various kinds of foods, such as cheese, margarine, flavored milk, canned foods, and so on, is permitted (4). The development of effective nisin production systems using LAB is a new field of interest. Nisin Z is a lantibiotic bacteriocin similar to nisin A which is produced by Lactococcus lactis IO-1 (15). Although nisin Z has not yet been accepted as a food additive, the effects of culture conditions such as pH, temperature, and calcium ion concentration on nisin production were investigated. It was suggested that an increased calcium ion concentration stimulated the production of nisin Z by L. lactis IO-1. However, the most important problem in nisin production is the inhibition of growth due to the increase in lactate concentration and the decrease in pH (24).

To avoid growth inhibition by the decrease in pH caused by the accumulation of lactate in LAB fermentation processes, pH control methods involving the addition of alkali or the extraction of lactate by using organic solvents have been reported (9, 27). However, the methods of extraction with organic solvents could not be used for food additive production. Although the addition of alkali as a means of pH adjustment was sometimes adopted for production of fermented foods, more attention has been paid to purely natural foods, without addition of artificial ingredients, as described in a paper forecasting the food industry in the year 2020 (22), and consumers who are sensitive to environmental issues are increasing in number. In this regard, removal of lactate from the reactor in an appropriate way will be preferable for pH control. Continuous-culture methods for lactate fermentation processes, using free or immobilized cells, have been reported (1, 7). Continuous culture with separation systems such as membranes (8, 18, 21) or electrodialyzers (11, 16, 26) also has been reported. Immobilization of cells in an L. lactis IO-1 cultivation process (6) and microfiltration in an L. lactis IFO12007 cultivation process (24) enabled continuous production of nisins Z and A, respectively. In these studies, nisin was produced continuously by keeping the cells in the fermentors. Removal of lactate from the cultivation medium with these separation systems precluded growth inhibition and achieved an extension of the fermentation period. However, the total fermentation processes including these separation systems were mechanically complex and costly.

In this study, L. lactis subsp. lactis (ATCC 11454) was used as a nisin-producing microorganism, and lactate was assimilated by a yeast, Kluyveromyces marxianus, which was isolated from kefir grains. The developed pH control strategy, without addition of alkali, will meet the demand of consumers who are sensitive to environmental issues. Moreover, the mixed-culture system gives us an example of the microorganisms’ interaction and provides useful information for future study of ecosystems. To exploit the interaction of these microorganisms in order to maintain a high level of nisin production, the kinetic parameters of both microorganisms, including specific growth rates and specific rates of production of nisin and lactate by L. lactis and the specific consumption rate of lactate by K. marxianus, were determined in a pure culture. Based on this information, a cascade pH control system in a batch mixed-culture process was developed. Nisin production in a mixed culture was compared with anaerobic and aerobic production in pure cultures of L. lactis with and without pH control by addition of NaOH.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Microorganisms and media.

L. lactis subsp. lactis ATCC 11454 (American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, Md.) was used as a nisin-producing microorganism. K. marxianus MS1 was isolated from kefir grains in our laboratory and identified by its morphological and biochemical properties (13). S. aureus IFO12732, which was obtained from the collection at the Institute for Fermentation Osaka (IFO), Osaka, Japan, was used as an indicator microorganism in the bioassay used for measurement of nisin concentrations. The compositions of media used for growth of microorganisms are summarized as follows. Medium a, used for seed culture and preculture of L. lactis (pH 7.0), contained (per liter) 5 g of maltose, 5 g of polypeptone (Nihonseiyaku, Tokyo, Japan), and 5 g of yeast extract (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.). Medium b, used for seed culture and preculture of K. marxianus (pH 7.0), contained (per liter) 10 g of l-lactate, 10 g of polypeptone, and 10 g of yeast extract. Medium c, used for the primary culture of L. lactis, contained maltose at 10 g/liter (in anaerobic cultures without pH control) or at 33 to 37 g/liter (in both anaerobic and aerobic cultures with pH control [pH 6.0]), 10 g of polypeptone per liter, and 10 g of yeast extract per liter. Medium d, used for primary cultures of K. marxianus (pH 6.0), contained (per liter) 40 g of l-lactate, 10 g of polypeptone, and 10 g of yeast extract. Medium e, used for mixed culture of L. lactis and K. marxianus (pH 6.0), contained (per liter) 42 g of maltose, 10 g of polypeptone, and 10 g of yeast extract. Medium f, used for bioassay of nisin (pH 7.0), contained (per liter) 10 g of glucose, 5 g of polypeptone, 5 g of yeast extract, and 5 g of NaCl. Selective medium g, used for determination of L. lactis CFU (pH 7.0), contained (per liter) 5 g of maltose, 5 g of polypeptone, 5 g of yeast extract, 5 mg of cycloheximide (Wako, Osaka, Japan), and 15 g of agar. Selective medium h, used for determination of K. marxianus CFU (pH 7.0), contained (per liter) 5 g of glucose, 5 g of polypeptone, 5 g of yeast extract, 5 mg of streptomycin (Nacalai tesque, Kyoto, Japan), and 15 g of agar. Initial maltose concentrations in the pH-controlled anaerobic, pH-controlled aerobic, and mixed cultures were 33.2, 36.8, and 41.4 g/liter, respectively.

Analysis.

Cell concentrations of the pure cultures were measured by determining the dry cell mass and optical density (OD). For determination of dry cell mass, the cells were filtered with a membrane filter (pore size, 0.45 μm; ADVANTEC, Tokyo, Japan) and dried in an oven at 70°C. ODs at 660 nm (OD660s) were measured at 660 nm with a UV spectrophotometer (model UV-2000; Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan). The viable-cell concentrations of L. lactis and K. marxianus in mixed cultures were determined as CFU on selective media g and h, respectively. The relationship between dry-cell concentration (dry weight [DW]) and CFU was approximated linearly by the least-squares method-derived correlation coefficients of data, and estimated values were also calculated by using the determined line (5). Concentrations of l-lactate, acetate, and formate in the medium were analyzed enzymatically by using F-Kit Lactate, F-Kit Acetate, and F-Kit Formate (Boehringer, Mannheim, Germany), respectively. Ethanol concentrations were measured with a gas chromatography apparatus (Hitachi model G-3000). Glucose concentrations were measured with a glucose analyzer (model 2700; YSI Inc., Yellow Springs, Ohio). Maltose concentrations were measured after hydrolysis to glucose as follows. A 100-μl volume of 2 N HCl was added to an equal volume of the sample, and the solution was boiled at 100°C for 20 min. Then 200 μl of 1 N NaOH was added, and the glucose concentration was measured with a glucose analyzer. The calibration curves for ethanol and maltose concentrations were determined linearly by the least-squares method. Accuracy of measurements was evaluated by using correlation coefficients (5).

Nisin concentrations were measured by a bioassay method based on the method of Matsuzaki et al. (14) as follows. Five milliliters of medium f was inoculated with S. aureus IFO12732 and incubated on a reciprocal shaker (100 strokes/min) at 30°C for 12 h. Fifty microliters of the cell suspension of S. aureus and 50 μl of the sample solution were added to 5 ml of fresh medium, and the cell suspension was incubated on the reciprocal shaker under the same conditions. After 12 h, the cell concentration was determined by measuring the OD660, using a UV spectrophotometer (model U-2000; Hitachi). A calibration curve was made for each new nisin concentration measurement, using commercially available nisin as a standard (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.; 1,000 IU/mg of solid; nisin content, 2.5% by weight). The sample was diluted so that the OD660 was in the range of 0.1 to 1.5 absorbance units because in this range the nisin concentration was linearly related to the OD660. A calibration curve for bioassay of the nisin was prepared for each fermentation experiment by the least-squares method (5). Nisin concentration was represented by concentration by weight (in milligrams per liter), and a nisin concentration of 1 mg/liter was equivalent to 40 IU/ml (15, 24).

Cultivation methods.

All microorganisms in the growth phase were stored in 20% (vol/vol) glycerol at −80°C. Before cultivation in 5-liter jar fermentors was performed, culture size was scaled up by two steps in order to increase the proportion of cells with high growth activity; first, a culture was started in test tube (the so-called seed culture), and second, culture size was scaled up to 500-ml Erlenmeyer flasks (for preculture) and, finally, 5-liter jar fermentors (for primary cultures). For seed cultures of L. lactis, 10 ml of medium a was inoculated with 50 μl of a stock solution and statically incubated at 30°C for 6 h. Preculture of L. lactis was performed in 500-ml Erlenmeyer flasks containing 200 ml of medium a and also 200 μl of the seed medium. The flask was statically incubated at 30°C for 10 h, and harvested cells were inoculated into the primary-culture medium. In the seed culture of K. marxianus, 5 ml of medium b was inoculated with 50 ml of stock solution and incubated on a reciprocal shaker at (100 strokes/min) at 30°C for 6 h. Preculture of K. marxianus was performed in 500-ml Erlenmeyer flasks with 100 ml of medium b and 100 μl of seed medium. The flask was incubated in the same way as the seed culture. After 16 h, the cells were harvested by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 15 min and used to inoculate the primary-culture medium.

Primary cultures were performed in 5-liter jar fermentors (EPC Control Box, Eyla, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with temperature, pH, dissolved oxygen [DO]) concentration, and gas flow control systems. The working volume was 2 liters. The pCO2 in the exhaust gas was measured with a CO2 gas analyzer (model VBI-210; Horiba, Kyoto, Japan). Air or nitrogen was supplied to the fermentor for aerobic or anaerobic cultivation conditions, respectively. The CO2 production rate (rCO2, in moles per hour) was determined as shown in equation 1:

|

1 |

where rAF, pCO2, pCO2*, R, and T are the air flow rate (in liters per hour), partial CO2 pressure in the exhaust gas from the fermentor (in atmospheres), partial CO2 pressure in the air (in atmospheres), gas constant (0.08206 liter · atm K−1 mol−1), and fermentation temperature (in degrees Celsius), respectively. The accumulation of CO2 was determined by integrating the CO2 production rate. The cascade controller developed for this system has more than one output per manipulation (23). In this study, the cascade control strategy was applied to control the pH level via DO control by manipulation of the agitation speed. The control strategy was coded in N88BASIC (NEC, Tokyo, Japan) on a personal computer (NEC model PC-9801BX). The control strategy and inoculum conditions in the mixed culture are described later.

Calculation of kinetic parameters.

The kinetic parameters, such as specific rates, were evaluated by the least-squares method (5). An example for the specific production rate of nisin is as follows. The material balance of nisin production is represented as shown in equation 2:

|

2 |

where [N], V, XL, and ρN are the nisin concentration, culture volume, cell concentration of L. lactis, and specific production rate of nisin, respectively. Equation 2 was integrated as shown in equation 3:

|

3 |

where 0 indicates the initial value of a variable. If ρN is constant, equation 3 can be rewritten equation 4:

|

4 |

If the plot of [N]V versus the integral of VXL is a linear relationship, it indicates that ρN is constant and can be estimated from the slope of the line by the least-squares method.

RESULTS

Statistical evaluation of regression lines for measurement and determination of kinetic parameters.

The relationship between DW and CFU of L. lactis is described by the equation DW = 2.02 × 10−9 CFU + 0.012 (correlation coefficient of data and estimated values [r2] = 0.99). The relationship between DW and OD660 of L. lactis is described by the equation DW = 0.404 × OD660 + 2.9 × 10−3 (r2 = 0.99). Theses relationships were obtained from the experiment using a pure culture of L. lactis. The relationship between DW and CFU of K. marxianus is described by the equation DW = 1.86 × 10−8 CFU (r2 = 0.99). The relationship between DW and OD660 of K. marxianus is described by the equation DW = 0.270 × OD660 + 0.103 (r2 = 0.99). These relationships were obtained from the experiment using a pure culture of K. marxianus. All of the correlations with measured and standard values of calibration curves for ethanol and maltose concentrations were evaluated with acceptable accuracy by chemical analysis (r2 = 0.95 to 0.99). The correlation coefficient of the regression line for nisin concentration was always larger than 0.995, which was also acceptable statistically. All of the kinetic parameters of L. lactis and K. marxianus are shown in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. The correlation coefficients for all of the parameter estimations obtained by the least-squares method are also shown in these tables. The basis for determining the kinetic parameters over the first 5 h and from 5 h to the completion of the experiment at 8, 12, or 11 h was mainly due to the fact that growth under anaerobic conditions without pH control ceased after 5 h. However, as a result, the determinations reflected the differences between the log and stationary phases of growth. Moreover, the consistency of the basis for these determinations was checked by determining the correlation coefficients of the linear line because the data included lag, log, and stationary phases of growth if they existed. Almost all of the correlation coefficients of the kinetic parameters were above 0.9, and it was concluded that the estimated values of the kinetic parameters were consistent.

TABLE 1.

Kinetic parameters of L. lactis under various conditions

| Conditions | Kinetic parameter (r2)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| μL (1/h) | ρL (g of lactate/g of cells/h) | ρA (g of acetate/g of cells/h) | ρN (mg of nisin/g of cells/h) | YL/Ma (mol of lactate/mol of maltose) | YA/Mb (mol of acetate/mol of maltose) | |

| Anaerobic | ||||||

| Without pH control, 0–5 h | 0.30 (0.979) | 0.81 (0.976) | NMc | 4.0 (0.940) | 3.7 (0.95) | NMc |

| With pH control | ||||||

| 0–5 h | 0.73 (0.988) | 0.70 (0.955) | 0.29 (0.994) | 9.4 (0.972) | 2.0 (0.94) | 0.96 (0.91) |

| 5–8 h | 0.25 (0.982) | 0.67 (0.995) | 0.16 (0.994) | 3.9 (0.985) | (0–8 h) | (0–8 h) |

| Aerobic | ||||||

| With pH control | ||||||

| 0–5 h | 0.45 (0.967) | 0.67 (0.931) | 0.32 (0.986) | 7.6 (0.989) | 1.29 (0.88) | 1.55 (0.98) |

| 5–12 h | 0.20 (0.977) | 0.34 (0.997) | 0.23 (0.989) | 5.2 (0.984) | (0–8 h) | (0–8 h) |

| Mixed culture | ||||||

| 0–5 h | 0.63 (0.985) | —d | 0.28 (0.997) | 9.7 (0.998) | —d | 0.94 (0.99) |

| 5–11 h | 0.22 (0.976) | —d | 0.24 (0.984) | 5.8 (0.994) | (0–11 h) | |

YL/M, lactate production yield with respect to maltose.

YA/M, acetate production yield with respect to maltose.

NM, not measured.

—, cannot be evaluated.

TABLE 2.

Kinetic parameters of K. marxianus

| Culture type | Kinetic parameter (r2)

|

|

|---|---|---|

| μK (1/h) | νL (g of lactate/g of cells/h) | |

| Pure culture | ||

| DO, 0.5 mg/liter | 0.12 (0.987) | 0.13 (0.965) |

| DO, ≥2 mg/liter | 0.38 (0.988) | 0.71 (0.997) |

| Mixed culture | ||

| 0–5 h | 0.48 (0.991) | —a |

| 5–11 h | 0.31 (0.987) | —a |

—, cannot be evaluated.

Nisin production without and with pH control.

The time course of nisin production by L. lactis under growth under anaerobic conditions without pH control is shown in Fig. 1. The pH of the medium fell below 5.0 within 3 h. Cell growth was completely terminated after 6 h, at which time the concentration of nisin was 7.4 mg/liter. After the cessation of growth, the nisin concentration decreased slightly. When maltose was used as the carbon source, not only lactate but also ethanol and acetate were produced (data not shown), even under anaerobic conditions. The change in carbon metabolism due to the carbon source and aeration is discussed later. The kinetic parameters obtained from this experiment are summarized in Table 1. The specific growth rate of L. lactis (μL) and the specific rate of production of nisin (ρN) without pH control were 0.30 h−1 and 4.0 mg of nisin/g of cells/h, respectively.

FIG. 1.

Nisin production by L. lactis without pH control under anaerobic conditions.

The time course of nisin production by L. lactis under anaerobic conditions at pH 6.0 is shown in Fig. 2. The cell concentration and the nisin concentration increased during cultivation to a greater extent than they did without pH control; however, μL was decreased after 5 h and nisin production reached a maximum value of 58 mg/liter (Fig. 2). μL was 0.73 h−1 for 0 to 5 h of batch culture, which was much higher than the value attained without pH control (Table 1); however, after 5 h, μL decreased to 0.25 h−1. ρN changed in proportion to μL (Table 1).

FIG. 2.

Nisin production by L. lactis with pH control under anaerobic conditions. The pH was controlled at 6.0 by the addition of NaOH.

Aerobic culture of L. lactis.

Aerobic cultivation of LAB is not common, but the aerobic growth of, and production of lactate by, some species have been reported (3). For lactate to be effectively assimilated by K. marxianus, aerobic conditions must be used. Hence, growth of L. lactis under aerobic conditions was investigated. The pH and dissolved oxygen (DO) concentration were maintained at 6.0 (by addition of NaOH) and 2.0 mg/liter, respectively. The results are shown in Fig. 3. As shown in Table 1, μL and ρN from 0 to 5 h of aerobic batch culture were slightly lower than the values obtained under anaerobic conditions. Furthermore, μL after 5 h under aerobic conditions was lower than it was under anaerobic conditions, but ρN under aerobic conditions was higher than it was under anaerobic conditions. As a result, the production yield of lactate with respect to maltose and the lactate concentration at 13 h were lower than the values obtained under anaerobic conditions (Table 1). Lactate, formate, acetate, and ethanol were formed from maltose under anaerobic conditions. On the other hand, lactate, acetate, ethanol, and CO2 were formed from maltose under aerobic conditions.

FIG. 3.

Aerobic growth of L. lactis, with pH control achieved by addition of NaOH.

Aerobic fermentation of K. marxianus.

The specific lactate consumption rate of K. marxianus was determined under aerobic conditions. The effect of the DO concentration on the rate of lactate consumption is shown in Fig. 4. The maximum specific rate of lactate consumption by K. marxianus (νL) was about 0.7 g of lactate/g of cells/h (Table 2), which was higher than the maximum specific rate of lactate production by L. lactis under aerobic conditions. Thus, it was expected that the lactate produced by L. lactis would be completely consumed by K. marxianus. νL decreased linearly as the DO concentration decreased in the range below 2 mg/liter, as shown in Fig. 4. When the lactate concentration was expected to be decreased, the DO level should have been increased and the specific rate of lactate consumption by K. marxianus would have been enhanced. On the other hand, when the lactate concentration was expected to be increased, the DO level should have been decreased and the specific rate of lactate consumption by K. marxianus would have been attenuated. These strategies were realized by a cascade controller of pH with DO concentration control in the mixed culture (see below). The maximum specific growth rate of K. marxianus (μK) in pure culture at a high DO level was lower than μL (Table 2).

FIG. 4.

Effect of DO level on the specific rate of lactate consumption by K. marxianus.

Dynamics of pH in the mixed culture of L. lactis and K. marxianus with a cascade controller.

The dynamics of concentrations of lactate and acetate ([L] and [A], respectively) are represented by equations 5 and 6, respectively:

|

5 |

|

6 |

where XL, ρL, and ρA are the cell concentration and the specific production rates of lactate and acetate of L. lactis, respectively, and XK and νL are the cell concentration and specific lactate consumption rate of K. marxianus, respectively. For overall electroneutrality balance, the total cation concentration in the medium has to be equal to the anion concentration. The H+ ion concentration (10−pH), OH− ion concentration (10pH − 14), dissociated lactate ion concentration, and dissociated acetate ion concentration were balanced with the ionic concentrations of acid and base, except lactate and acetate, as shown in equation 7:

|

7 |

where Xacid and Xbase are the total dissociated ion concentrations of acid and base, except lactate and acetate; MWA and MWL are molecular weights of acetate and lactate, respectively; and pKL and pKA are the pK values of lactate and acetate, respectively. Terms 1 and 2 in equation 7 correspond to the dissociated lactate ion concentration and the dissociated acetate ion concentration, respectively. By rewriting the right-hand side of equation 7 as a nonlinear function of pH, L, and A as f(pH, L, A) and differentiating equation 7 with respect to time (t), equation 8 is obtained:

|

8 |

|

Because the changes in Xacid and Xbase are negligible compared with the changes in the concentrations of lactate and acetate, the dynamics of the pH change with time is described as shown in equation 9:

|

9 |

By substituting equations 5 and 6 into equation 9, equation 10 is obtained:

|

10 |

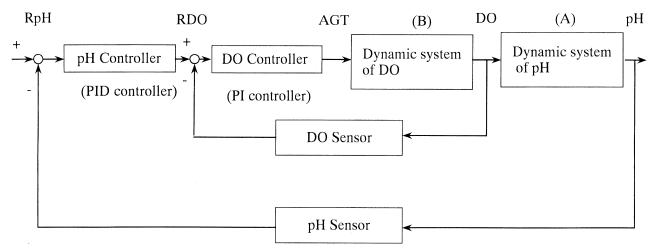

The terms (∂f/∂pH), (∂f/∂[L]), and (∂f/∂[A]) in equation 10 are positive, and the rate of production of acetate at the beginning of the batch culture is negligible. Thus, it is easily understood that if the rate of lactate production by L. lactis is higher than the rate of lactate consumption by K. marxianus—that is, the term (ρLXL − νL XK) is positive—the pH decreases. On the other hand, when the rate of consumption of lactate is higher than its rate of production—that is, the term (ρLXL − νL XK) is negative—the pH increases. Then, the rate of lactate consumption by K. marxianus must be increased or decreased depending on whether the pH is above or below the set point of 6.0, as long as lactate exists in the medium. The specific rate of lactate consumption by K. marxianus (νL) can be controlled within a limited range (0 to 0.7 g of lactate/g of cells/h) by changing the DO level (0 to 2 mg/liter) as shown in Fig. 4. The DO concentration in the medium can be controlled by manipulating the agitation speed of the impeller. Finally, it was found that the pH of the medium of the mixed-culture system could be controlled by changing the DO control set point. This type of controller is categolized as a cascade controller (23). The cascade controller of pH coupled with DO control developed here is shown below (see Fig. 5). Proportional and integral (PI) and proportional, integral, and differential (PID) controllers were used as precompensators of DO and pH in the cascade controller, respectively.

FIG. 5.

Scheme of a cascade pH controller incorporating DO control. Two outputs of pH and DO were measured by pH and DO sensors, respectively. Manipulation was only via agitation speed (AGT), which changed the DO, and the DO changed the pH via lactate consumption by K. marxianus. The pH was controlled by the DO set point, RDO.

The dynamic response resulting from the change in pH due to the DO change, shown in box A of Fig. 5, was as follows: when the DO changes, νL changes according to the relationship between DO and νL shown in Fig. 4. Note that Fig. 4 shows a static relationship. However, when the DO level changes dynamically, there is a dynamic time delay from DO change to νL, because cell lactate assimilation activity occurs after changes in activities of many enzymes due to the change in DO concentration. The change in pH is based on the dynamics described by equation 10. The dynamic response of the agitation speed of the impeller to the DO level, shown in box B of Fig. 5, is as follows: when the agitation speed changes, the mass transfer rate of oxygen from air bubble to liquid changes, with a very small time delay, and the dynamics of DO are described by the balance between oxygen supply from air bubble to liquid and the rate of consumption of oxygen by both microorganisms. The automatic control strategies of pH and DO are described later.

Inoculum size of mixed culture.

The ratio of L. lactis and K. marxianus inoculum sizes was determined so that the lactate concentration was constant at the initial time of the operation, i.e., the start of the fermentation, as shown below. If lactate accumulates to a high level in the medium at the beginning of mixed culture, the growth rate of L. lactis is dramatically decreased, causing a fatal condition. For a reliable mixed-culture operation, the ρL was overestimated as 2.0 g of lactate/g of cells/h, which was three times higher than the actual data (Table 1). On the other hand, νL was initially set to 0.5 g of lactate/g of cells/h. Then, the ratio of XL to XK was set to 0.25, which could be derived by setting the right-hand side of equation 5 to zero, which is equivalent to the lactate concentration being constant. For the same reasons, the right-hand side of equation 10 becomes zero, which means that the pH does not change. After all, before the primary-culture experiment started, the concentrations of both microorganisms in the preculture was determined by measuring the OD660 and the inoculum size was set as XL/XK = 0.25 in the subsequent experiments.

Nisin production with pH cascade control in a mixed culture at pH 6.

The time course of a mixed culture of L. lactis and K. marxianus is shown in Fig. 6. The pH set point was 6.0. The DO set point was not obtained automatically but was manually changed in this case for the first trial. The lactate concentration was kept at almost zero throughout the experiment. After 2 h, the DO level was increased and the νL was enhanced because the pH decreased slightly from the set point of 6.0. The cascade control of pH succeeded. Both L. lactis and K. marxianus were growing exponentially until 11 h. The nisin production rate reached a maximum of 98 mg/liter.

FIG. 6.

Nisin production in a mixed culture of L. lactis and K. marxianus. The pH was controlled at 6.0 by the cascade controller.

Even though acetate accumulated (4 g/liter), the decrease in pH was less than that observed with lactate accumulation (Fig. 1), because when maltose was used as a carbon source under anaerobic conditions, not only lactate but also acetate and formate were produced. When lactate was produced at 2 g/liter, acetate and formate were produced at 1.5 and 2.5 g/liter, respectively. The decrease in pH evident in Fig. 1 was due to production of lactate, acetate, and formate. On the other hand, formate was not produced under aerobic conditions; instead, CO2 was produced. Figure 6 shows that lactate accumulated at a rate of 0.45 g/liter in the early stages of fermentation (at 2 h) and that it was consumed by K. marxianus for 6 h. The pH decreased during the 0- to 2-h period due to the accumulation of lactate. Consumption of lactate after 2 h counteracted the accumulation of acetate.

Biomass production by the mixed culture was also compared with that of a pH-controlled anaerobic pure culture of L. lactis. In an anaerobic pure culture of L. lactis, the dry-weight cell concentration was 2.6 g/liter after 13 h. The dry-weight cell concentration of L. lactis in the mixed culture could not be measured directly but was estimated by using the relationship between DW and CFU, which was obtained from the experiment using a pure culture of L. lactis. The estimated dry-weight cell concentration of L. lactis in the mixed culture was 3.4 g/liter, which was higher than that in the pure culture. The fact that the rate of nisin production in the mixed culture was also higher than that in the pure culture indicates that nisin production was growth associated.

Figure 7 shows the automatic cascade control results for the coupling of pH with DO control in the mixed culture. PI and PID control strategies for the automatic control of DO and pH controllers are described in the Appendix. The control parameters of the PI (DO) controller—sampling time (Δt), proportional gain (Kp), and integral time (Ti)—are set to 0.5 min, 40 rpm · liter/mg, and 2.0 min, respectively. The control parameters of the PID (pH) controller—pH set point (RpH), sampling time (Δt), proportional gain (Kp), integral time (Ti), and derivative time (Td)—are set to 6.0, 0.5 min, 0.5 mg/liter, 12.5 min, and 6.0 min, respectively. The control parameters of PI and PID controllers were tuned so that pH fluctuation was less than ±0.5 units.

FIG. 7.

Control of pH and DO by the cascade controller without addition of NaOH in the mixed-culture system.

As shown in Fig. 7, because the set point of DO at time zero for the DO controller [RDO(0)] was 1.0 mg/liter, the actual value of DO decreased rapidly at the beginning of the experiment and returned to the set point within 2 h. When the pH decreased below the set point at around 3 h, the RDO increased according to equation A4 (see Appendix). As a result, the νL recovered and the pH increased again to around 4 h due to the decreasing lactate concentration. By changing the RDO, the pH was reliably and accurately controlled at the set point of 6.0. To improve the performance of the controller, a predictive controller with an estimator of the lactate consumption activity may have to be developed. Also, to analyze the stability of the controller in detail, the dynamic responses of the activity of microorganisms to changes in environmental conditions must be investigated precisely.

DISCUSSION

In this study, a novel method of pH control, utilizing the interaction between two microorganisms was developed. Nisin production in a mixed culture (98 mg/liter) was higher than that in a pure culture (58 mg/liter). In an anaerobic pure culture of L. lactis without pH control, the amount of nisin produced was quite small. When the pH was controlled by addition of NaOH, nisin production in anaerobic cultivation was increased slightly compared with that attained under aerobic conditions. However, production ceased at 58 mg/liter because of growth inhibition, not due to the decrease in pH but rather due to the increase in the lactate concentration. In a mixed culture with cascade pH control, the produced nisin concentration was over 98 mg/liter (3,920 IU/ml), which was 1.7 times higher than that in the anaerobic culture with pH control via addition of NaOH.

It was reported that the maximum production of nisin Z (3,150 IU/ml) was obtained in batch culture with pH control via addition of NaOH (15). It is difficult to compare these two methods directly because the species of microorganisms used and kinds of bacteriocins produced were different; however, because the undissociated lactate and low pH strongly inhibited the growth of LAB (9), the complete removal of lactate might be more effective for maintaining a high rate of cell growth and production of the growth-associated product than the system using the pH control via addition of alkali.

Nisin production by a microfiltration technique also has been reported (24). The maximum production rate with this method was 78 IU/ml/h. The cultivation method developed in our study was a batch method, so the production rate was evaluated as the amount produced divided by the volume and the production time and was found to be 360 IU/ml/h. Another reason why the microfiltration method gave a low production rate may be adsorption of nisin onto the membrane filter.

The proposed mixed-culture system was mechanically simple because the system utilized the interaction between two microorganisms. This method requires careful selection of the carbon source. In this study, maltose was selected. To develop the cascade controller, aerobic conditions were necessary. With this limitation, it might be difficult to extend this methodology to other mixed-culture systems. Recently, we isolated from cheese different strains of a yeast which cannot assimilate lactose but can assimilate lactate. In this case, lactose is used as a carbon source. Thus, it should also be stressed that by careful selection of the system, the principle presented here can be made available for use with another carbon source and other combinations of microorganisms.

It is expected that this mixed-culture system will become an example of microbial interactions and will provide technical information for further studies. For example, the difference between pH control by addition of alkali and that by mixed culture in terms of nisin production will be analyzed more precisely in the future. For this, the effect of the controlled levels of lactate concentration and DO on the lactate and nisin production rates of L. lactis as well as the lactate consumption rate of K. marxianus in the mixed culture should be measured directly or estimated precisely.

CO2 formation by L. lactis was observed under aerobic conditions. A C4 compound such as acetoin or butanediol might be produced under aerobic conditions, because CO2 formation indicated that pyruvate dehydrogenase was active under these conditions (17). In glucose and lactose media, homofermentation by L. lactis was observed. It was reported that when maltose was assimilated, heterofermentation of L. lactis that is different from glucose metabolism occurs (19). The change of molar flux in the metabolic pathway should be analyzed in the future.

Appendix

PI (DO) control strategy. For the DO controller shown in Fig. 5, the PI controller used is represented by the equation

|

A1 |

where AGT(t) and DO(t) are the agitation speed of the impeller and DO at time t, RDO(t) is the set point of DO control, Δt is the sampling time, Kp is the proportional gain, and Ti is the integral time in the controller, respectively. In the conventional PI controller, RDO(t) was usually treated as a constant value, but it was given as the output of the pH controller in the cascade controller. The PI controller was actually used as a velocity form by rewriting equation A1 as

|

|

A2 |

where the initial value of AGT, AGT(0), was set to 100 rpm. In the velocity form of the controller, AGT(t) was realized by correcting AGT(t − 1). Although equations A1 and A2 are completely equivalent, the overshoot would be reduced when manipulated variables of AGT have upper and lower limits.

PID (pH) control strategy. For the pH controller, a PID controller was used as shown in equation A3:

|

A3 |

where pH(t), RpH, and Td are the pH at time t, the pH set point, and the derivative time in the controller, respectively. In this controller, the derivative of the pH was estimated by subtracting the present pH from the pH data at time (t − 6). The PID controller was used as a velocity form in the same way as the PI (DO) controller as shown in equation A4:

|

A4 |

RDO at time zero, RDO(0), was set 1.0 mg/liter. Because there was a lengthy delay between the DO change and the change in the specific lactate consumption rate of K. marxianus responses, the derivative correction term in the controller was very important for detecting the pH change, while there was a short delay from the agitation change to the DO response.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amrane A, Prigent Y. A novel concept of bioreactor: specialized function two-stage continuous reactor, and its application to lactose conversion into lactic acid. J Biotechnol. 1996;45:195–203. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beuchat L R, Clavero M R S, Jaquette C B. Effects of nisin and temperature on survival, growth, and enterotoxin production characteristics of psychrotrophic Bacillus cereus in beef gravy. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:1953–1958. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.5.1953-1958.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borch E, Molin G. The aerobic growth and product formation of Lactobacillus, Leuconostoc, Brochothrix, and Carnobactrium in batch cultures. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1989;30:81–88. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Broughton J B. Nisin and its uses as a food preservative. Food Technol. 1990;44:100–117. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bulmer M G. Principles of statistics. New York, N.Y: Dover Publications Inc.; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chinachoti N, Endo N, Sonomoto K, Ishizaki A. Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Society of Fermentation and Bioengineering of Japan. Society of Fermentation and Bioengineering of Japan, Fukuoka. 1995. Fermentative production of peptide antibiotic (nisin Z) by Lactococcus lactis IO-1 cells immobilized with various kinds of gel materials; p. 52. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Demirci A, Pometto III A L, Johnson K. Evaluation of biofilm reactor solid support for mixed-culture lactic acid production. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1993;38:728–733. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hayakawa K, Sansawa H, Nagamune T, Endo I. High density culture of Lactobacillus casei by a cross-flow culture method based on kinetic properties of the microorganisms. J Ferment Bioeng. 1990;70:404–408. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Honda H, Toyama Y, Takahashi H, Nakazecko T, Kobayashi T. Effective lactic acid production by two-stage extractive fermentation. J Ferment Bioeng. 1995;79:589–593. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hurst A. Nisin. Adv Appl Microbiol. 1981;27:85–123. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ishizaki A, Vonktaveesuk P. Optimization of substrate feed for continuous production of lactic acid by Lactococcus lactis IO-1. Biotechnol Lett. 1996;18:1113–1118. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jack R W, Tagg J R, Ray B. Bacteriocins of gram-positive bacteria. Microbiol Rev. 1995;59:171–200. doi: 10.1128/mr.59.2.171-200.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kultzman C P, Fell J W. The yeasts: a taxonomic study. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matsusaki H, Endo N, Sonomoto K, Ishizaki A. Purification and identification of a peptide antibiotic produced by Lactococcus lactis IO-1. J Fac Agric Kyushu Univ. 1995;40:73–85. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matsusaki H, Endo N, Sonomoto K, Ishizaki A. Lantibiotic nisin Z fermentative production by Lactococcus lactis IO-1: relationship between production of the lantibiotic and lactate and cell growth. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1996;45:36–45. doi: 10.1007/s002530050645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nomura Y, Yamamoto K, Ishizaki A. Factors affecting lactic acid production rate in built-in electrodialysis fermentation, and approach to high speed batch culture. J Ferment Bioeng. 1991;71:450–452. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Novak L, Cocaign-Bousquet M, Lindley N D, Loubiere P. Metabolism and energetics of Lactococcus lactis during growth in complex or synthetic media. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:2665–2670. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.7.2665-2670.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ohara H, Hiyama K, Yoshida T. Lactic acid production by filter-bed-type reactor. J Ferment Bioeng. 1993;76:73–75. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Qian N, Stanley G A, Bunte A, Radstrom P. Product formation and phosphoglucomutase activities in Lactococcus lactis: cloning and characterization of a novel phosphoglucomutase gene. Microbiology. 1997;143:855–865. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-3-855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ryan M P, Rea M C, Hill C, Ross R P. An application in cheddar cheese manufacture for a strain of Lactococcus lactis producing a novel broad-spectrum bacteriocin, lacticin 3147. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:612–619. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.2.612-619.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shi Z, Shimizu K, Iijima S, Morisue T, Kobayashi T. Adaptive on-line optimizing control for lactic acid fermentation. J Ferment Bioeng. 1990;70:415–419. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sloan A E. Food industry forecast: consumer trends to 2020 and beyond. Food Technol. 1998;52:37–44. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stephanopoulos G. Chemical process control. Englewood, Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall International Inc.; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Taniguchi M, Hoshino K, Urasaki H, Fujii M. Continuous production of an antibiotic polypeptide (nisin) by Lactococcus lactis using a bioreactor coupled to a microfilteration module. J Ferment Bioeng. 1994;77:704–708. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thomas L V, Wimpenny J W T. Investigation of the effect of combined variations in temperature, pH, and NaCl concentration on nisin inhibition of Listeria monocytogenes and Staphylococcus aureus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:2006–2012. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.6.2006-2012.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vonktaveesuk P, Tonokawa M, Ishizaki A. Stimulation of the rate of l-lactate fermentation using Lactococcus lactis IO-1 by periodic electrodialysis. J Ferment Bioeng. 1994;77:508–512. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yabannavar V M, Wang D I C. Extractive fermentation for lactic acid production. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1991;37:1095–1100. doi: 10.1002/bit.260371115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]