Abstract

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus – SARS CoV 2 (COVID 19) has posed a dire threat, not only to physical health but also to mental health, impacting our overall lifestyles. In addition to these threats, there have been unique challenges for different subsets of the population. Likewise, college students including research scholars are facing a variety of challenges in response to the COVID-19 outbreak. The scoping review maps existing literature on the mental health of college students in the times of COVID-19, approaches adopted by universities and academic institutions to help students cope with challenges posed by COVID-19 and draws lessons learnt and potential opportunities for integrating mental health promotion as part of routine services, particularly in low-and-middle-income countries context such as India. Four electronic databases (PubMed, PsycINFO, Scopus and Google Scholar) were searched following Arksey and O'Malley's scoping review process. Out of the total 1038 screened records, thirty-six studies were included in the review. Data characteristics such as the type of document, intervention and outcome were extracted. Data were synthesized using thematic content analysis. The fact that the COVID-19 pandemic has impacted the mental health of students, accentuates the urgent need to understand these concerns to inform the action and public mental health interventions that can better support college students to cope with the crisis.

Keywords: COVID-19, Pandemic, Mental health, College students, Scoping review

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has impacted the mental health of most if not all individuals, as a result of the physical health implications, lockdown and disrupted lifestyles. It is becoming apparent that mental health of young people (15–24 years of age) has been adversely affected adversely (Malhotra and Patra, 2014; Population Fund of India, 2020). A notable proportion of younger individuals pursue higher education all over the world, accounting for about 250 million students (2020) which are projected to grow up to 600 million students by 2040 (Dojchinovska, 2021). As the COVID-19 pandemic has been escalating, the threat to the well-being of students pursuing higher education (college students) has only risen globally. The pandemic has impacted college students' mental health (apart from academic function) adversely with the closure of campuses, remote learning and fear of infection, and a sense of uncertainty about their academic and professional careers (Sahu, 2020; Zhai and Du, 2020; Duan and Zhu, 2020).

Mental health problems ranging from psychological distress to clinically diagnosable psychiatric illnesses have been documented long before the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic (Kumaraswamy, 2013; Wahed and Hassan, 2017; Roy et al., 2020). Some common mental health problems among college students have been stress, relationship difficulties, low self-confidence, issues around sex and sexuality, substance use, traumatic experiences (such as rape, sexual assault or abuse), loneliness and homesickness anxiety, eating problems, depression and suicidal ideation (Kumaraswamy, 2013; Wahed and Hassan, 2017; Li et al., 2021).

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused ripples of strong negative emotions among college students and research scholars as well, exacerbating the existing psychological challenges that they face (Dennon, 2021; Fleurimond et al., 2021). In response to COVID-19 and the lockdown measures, many colleges had suspended in-person classes and evacuated students from their campuses. Other public health measures such as mandatory physical distancing and regulations on social gatherings have left many students feeling disconnected and lost social support. Recent evidence highlights a spectrum of psychological consequences viz., stress, fear, loneliness, sleeplessness, over-thinking and given rise to a heightened sense of uncertainty among young people including college students due to the pandemic (Sahu, 2020; Zhai and Du, 2020; Duan and Zhu, 2020; Fleurimond et al., 2021). While the world is busy addressing COVID-19, it is also imperative to attend to the mental health issues of college students. This article discusses the mental health of college students in the times of COVID-19 and proposes strategic actions for higher education institutions in low and middle-income countries.

2. Material and methods

The review was conducted using Arksey and O'Malley's scoping review framework (Arksey and O'Malley, 2005). Accordingly, the methodology is described in the following stages:

-

Stage 1

Identifying the research question

-

Stage 2

Searching for relevant studies

-

Stage 3

Selection of studies

-

Stage 4

Charting of data

-

Stage 5

Collating, summarizing, and reporting the result

2.1. Identifying the research question (stage 1)

This review aimed to identify current evidence on the COVID-19 pandemic impact on the mental health of college students and approaches adopted by higher education institutions to prevent and help students cope with mental health consequences. The research questions were.

-

1.

What are the mental health consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic in college students?

-

2.

What are the approaches adopted by higher education institutes to prevent and help students cope with mental health challenges?

Operational definitions.

-

•

College students: Students pursuing higher education (graduate, post-graduate and doctoral studies) after the 12th class

-

•

Mental health: Mental health is a state of well-being in which an individual realizes his or her abilities, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and can make a contribution to his or her community.

-

•

Mental health consequences: It refers to a negative impact where one is not able to cope with the stress.

-

•

COVID-19 pandemic: It refers to different waves of COVID-19.

2.2. Searching for relevant studies (stage 2)

References for this review were identified through searches of PubMed, PsychINFO, Scopus and Google Scholar with the search terms like “COVID-19 pandemic” OR coronavirus outbreak” AND “college students,” OR “university students,” “higher education,” AND “mental health,” and “COVID-19” from November 2021 until February 2022. These keywords were combined with Boolean operators to narrow down the search results. Manual searches were executed to identify gray literature and additional articles based on the references mentioned in the articles selected for full-text review. Only records published in English were reviewed. Following inclusion and exclusion criteria were used for screening and selection of records (See Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria for including studies in the present review.

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| Studies on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of college students | Studies published on mental health during COVID-19 in students of secondary school or other population |

| Reviews or studies focusing on approaches adopted by higher education institutions | Studies conducted on college students' mental health in the general context |

| Records published between January 2020 until February 2022. | Records published before January 2020. |

| Studies with full-text being available by journal or pre-print server | Studies/records whose full texts are not available |

| Studies published in English | Studies published in other than English |

2.3. Selection of studies (stage 3)

Two reviewers (PL + AkP) screened the articles, and disagreements were discussed. In addition, databases of COVID-19 literature were hand searched. These databases included MedArchives, Zenodo, and WHO COVID-19 Research Database. The references of articles that matched the eligibility criteria were also further searched. The studies obtained through reference searching and the COVID-19 literature databases were subject to the same screening and selection process.

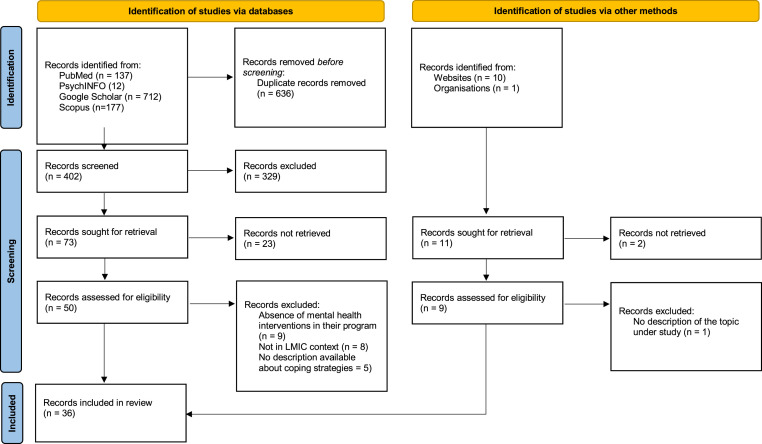

The initial search yielded 1038 records (PubMed-137; PsychINFO-12; Scopus-177; Google Scholar-712) of which 636 were excluded based on title review and duplicates. Later 329 records were rejected based on the abstract review. About 50 records were selected for full text reviews. Out of which, a total of 36 records (28 peer-reviewed articles, 1 guideline & 7 newspaper articles & blogs) met the inclusion criteria and were finally selected for the scoping review. The literature search has adhered to the PRISMA-ScR (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis extension for Scoping Reviews) guidelines (Tricco et al., 2018). The PRISMA chart is presented in Fig. 1 .

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of the scoping review study.

2.4. 4. charting of data (stage 4)

Data extraction criteria of the present scoping review were determined, and the data extraction form in the excel sheet was designed in consultation with both reviewers.

2.5. Collating, summarizing, and reporting the result (stage 5)

Findings were synthesized narratively. Summary of findings are presented in the results section in three sections: 1) impact of COVID-19 on academics of college students, 2) mental health of college students, and 3) Approaches adopted by higher education institutions. Recommendations are presented in the discussion section.

3. Results

3.1. The impact of COVID-19 on academics of college students

In the last two years, there have been a surge in COVID-19 cases multiple times and colleges/university had to shut down as precautionary public health measure. Thus colleges had to close and start education virtually. The transition to online teaching (which includes a digitally equipped platform, resources for teaching as well as assessment and follow up) was challenging for many students in low resources countries, especially the LMICs where teaching was a conventional, in-person affair along with the lack of technological provision as well as poor technical know-how. In a way, education was disrupted by the pandemic. As noted by previous studies, disruption in academics reduces motivation for studies and increases pressure to learn independently among students (Grubic et al., 2020). Therefore, it is reasonable to think that students may experience stress, reduced motivation to learn, abandonment of daily routines, and potentially higher rates of dropout as direct consequences of public health measures. YoungMinds administered a worldwide student survey that reported 83% of young respondents agreed that the pandemic worsened pre-existing mental health conditions, mainly due to the closure of academic institutions, loss of routine, and restricted social connections (YoungMinds, 2020). Beyond these numbers, one in three students reported having a diagnosed mental health condition in 2020 (YoungMinds, 2020) and one in four students was taking psychiatric medication (Brown, 2021). Disruption in students’ research projects and internships have compromised their study and, in some cases, delayed their completion of the study/degree which further means delayed admissions to higher studies, and this fuels anxiety among students (Zhai and Du, 2020).

Some additional challenges that the college students faced that directly and/or indirectly negatively impacted their mental health were financial struggles imposed by the pandemic, health complications within the family, death of dear ones, fear of getting the infection as well as fear of being the carrier and transmitting COVID-19 to their family members (Zhai and Du, 2020; Pan et al., 2020) An Indian study looked at the impact of COVID-19 on students which found that a rise in apprehension about productivity, postponing planned activities, and nervousness about healthcare availability was observed (Moghe et al., 2021). Further, dependence on video games, emotional eating and excessive use of social media are also noteworthy negative consequences that demand attention. Despite the focus on developing a ‘lockdown routine’ students found it challenging to do so. COVID-19 also brought along for students an inclination toward an existential approach and introspection that initially did invoke anxiety (Twenge and Campbell, 2018).

3.2. The impact of COVID-19 on the mental health of college students

Many students complained of psychological difficulties and ill effects of screen time to authors (as counselling practitioners), which has also been previously established (Ochnik et al., 2021). It has brought several challenges to learning and increased vulnerability to mental health (Sahu, 2020; Ochnik et al., 2021). For example, some students harboured intense negative feelings such as frustration, anxiety, and betrayal when they had to stay away from the college for a long time (Kumaraswamy, 2013; Wahed and Hassan, 2017; Roy et al., 2020; Verma, 2020). Similarly, being away from home had set in homesickness for many students studying overseas. Some struggled with loneliness and isolation because of being disconnected from friends and partners. Many studies have reported increased levels of stress, anxiety, depressive thoughts, disruptions to sleeping patterns, difficulty in concentrating, feelings of denial, anger, fear and increased concerns about academic performance among young people including college students (Wahed and Hassan, 2017; Moghe et al., 2020; Adedoyin and Soykan, 2020). Furthermore, there is a tendency for psychological symptoms of those students with existing mental illness to exacerbate and increase some students’ risk for suicide and substance abuse. Anecdotal evidence and the gray literature (newspaper reports) confirm the same, an increasing trend of suicide among college students during the pandemic, warranting emergency services more than ever before (Arsandaux et al., 2021; Dennon, 2021).

Another survey that studied the impact of COVID-19 on students confirmed that the status of being a student was associated with a higher frequency of depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms, perceived stress and suicidal thoughts (Akin-Odanye et al., 2021). The research literature also elaborated on the impact of COVID-19 on the mental health of students all across the world. In a survey by Best Colleges, it was found that over 90% of students had negative mental health as a result of the pandemic and the three most common of them (negative mental health effects) were social isolation, lack of focus and anxiety, among many others (Population Fund of India, 2020). In another study, where students were surveyed to understand the mental health impact of COVID-19 on higher institutions students. results deliberated that financial stability, interpersonal relationships and worries related to achieving academic milestones were the major factors that triggered mental health problems among students (Akin-Odanye et al., 2021).

3.3. Approaches adapted to address college students’ mental health in low-middle-income countries

A systematic review (El Harake et al., 2022), shows that college students experience quite several mental health problems as a result of COVID-19 lockdown, reopening and closure of colleges as well as the emergence of new variants of the disease. The common problems in the student population were noted as mentioned above. The review unveils the fact that previously experienced pandemics such as that of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS, 2003), the swine flu pandemic in 2009, and the Ebola epidemic had a similar impact on the mental health of students, such as seen in COVID-19. This emphasizes that future public health emergencies will also have a huge impact on the mental health of students, hence the need to have sustainable coping strategies in place to ensure mental health resilience.

In response to the mental health upheaval, as a result of the pandemic, colleges, governments and organizations in the field (of mental health) have taken several measures to address the needs of the students. LMICs like India demonstrate some promising national and state-level responses. For instance, The Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India, issued a toll-free helpline number for ‘behavioural health’ called the psychosocial toll-free helpline- 08046110007 that can be used by anyone needing mental health assistance (including students) during the COVID-19 pandemic (The Hindu, 2020). The Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment of the Indian government also launched another toll-free helpline called ‘Kiran’ to address suicide prevention and mental health concerns which have been accessed by Indian students and citizens (Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment, 2020). The Ministry of Education of Indian government, as part of Atma Nirbhar Bharat Abhiyan also launched Mano Darpan, for psycho-social support for the mental health and well-being of students during the COVID-19 outbreak (Ministry of Education, 2020). It has prescribed suggestions for the well-being of students, parents and teachers. (Jain, 2020). Manodarpan has an exquisite advisory for college/university students where they also provide some practical tips to manage the mental health of students, parents and faculties, with a dedicated section to students with a disability as well. (Population Fund of India, 2020).

In addition, the University Grants Commission (UGC, India) (University Grants Commission, 2020) also spearheaded various initiatives for the mental well-being of students. The UGC proposed the setting up of helplines, regular mentoring of students through interactions, appeals and letters, identifying students needing help and providing them with that help and sharing various videos, reading material through social media platforms to ensure mental health, psycho-social well-being of students and keeping them calm and stress-free (Jain, 2020). UNESCO, India office launched a guide called ‘Minding our Minds’ to help students manage their mental health during the pandemic. Accompanying the guide are also an array of posters available in various Indian languages to foster mental health literacy (UNESCO, 2020).

Many universities and colleges started helplines for COVID-19 for the general population which were extended to the students as well. Tele-counselling services for students were available in voice call as well as video call where several issues were addressed: uncertainty about exams, academic pressure, mental health concerns among students and support to those students affected by COVID-19 and quarantine/isolation (The Hindu, 2020; O ’ Hara, 2020). Besides, colleges launched online support groups, online sessions for students, surveys to assess mental health needs among students and online psychological counselling services (Bengrut, 2020). The positive impact of peer support was also realized especially during COVID times to ameliorate the negative impact on mental health during the pandemic (Suresh et al., 2021). Notably, a team of research scholars and students also came together to provide help to their fellow college mates through telephonic and email conversations as well as assisting with academic pressure (Ibrar and Chettri, 2020; Akin-Odanye et al., 2021). It was recommended that students' access to economic relief packages, access to virtual counselling and psychosocial support would help improve the negative impacts of the pandemic (Dorsey and Topol, 2020).

4. Discussion

The present review brings attention to the issue of mental health concerns of college students that have blazed amidst the period of the pandemic. Almost two years into the pandemic, it is commendable how many colleges have responded promptly by focusing on remote education instead of in-person classes (Ibrar and Chettri, 2020). Remote learning allows college students to sustain their academic routine which is found to benefit mental health and psychological resilience in the long run (Akin-Odanye et al., 2021). Though learning via online classes has allowed for education to continue amidst the wreck of the pandemic, it hasn't been the most comfortable for many. In addition, college students may experience less anxiety because remote learning helps them continue to manage their academic routine regularly (Li and Lalani, 2020). However, this transition can also lead to acute stress among some students due to the lack of time to adjust to online learning. Anecdotally, students using the online medium for learning have also had several complaints such as that headaches, back-aches, irritation and watering of the eyes as well as ear problems; in addition to experiencing a lack of motivation to study online, not feeling involved and interested, missing in-person classes, inability to effectively understand and learn practice-oriented subjects (such as Mathematics and Geometry) and finally leading to the inexorable screen fatigue (Brenes et al., 2015).

There are sufficient indicators to warrant attention to their mental health. This realization calls for systemic level action to address the mental health concerns of students beyond the pandemic. Over the years, more and more academic institutes are instating counselling cells, which are more of a curative intervention missing out on prevention and promotion of positive mental health. With growing academic pressure and several other stressors in addition to COVID-19, the need for college mental health promotion programs in academic institutes is imperative for the student's holistic well-being which inadvertently contributes to better academic performance and personal and social adjustments.

4.1. Strategic recommendations to address the mental health crisis in low and middle-income countries

For students, the college serves an indispensable role in supporting and accommodating their health, education as well as safety needs. To make recommendations effective, the authors classify them into the following suitable categories:

4.1.1. Recommendations for the current pandemic situation

As the pandemic is here to stay and online classes to ensue, a few recommendations for colleges and academic institutions could help aid the loopholes: First, in addition to remote education, (online) mentor-mentee meetings should be available to provide academic support for students. Second, colleges may consider offering virtual office hours to students, to share and address academic and administrative concerns as well. Third, for students whose internships or research scholars whose research projects were affected by the pandemic, supervisors and research guides should actively engage in helping students seek alternative plans such as virtual internship opportunities, make timelines more flexible, accommodate research based on secondary data or systematic review and likewise virtually suited alternatives, to maintain the momentum on research projects and maximize academic learning. Fourth, faculty members may be trained on identifying the fundamental mental health problems in students and psychological first-aid so that they can guide students with first-line help while maintaining the confidentiality and promptly refer them to mental health services whenever needed. Fifth, assigning mentors to groups of students and informal interactions between mentors and mentees would be effective where each student can share their problems with the mentor. Sixth, colleges should set up counselling centres or empanel mental health professionals to provide online mental health services (i.e., tele-mental health counselling) to the students as per the requirement. Tele-mental health has been found effective in treating anxiety and depressive symptoms (Wang et al., 2020; Rollman et al., 2018), and implementing tele-mental health will facilitate the delivery of counselling services to address students’ pressing mental health concerns. University counselling centers can also provide options for students to join online support groups that enable them to share common concerns and receive social support (Rollman et al., 2018). Seven, academicians/professors/research mentors can duly incorporate reporting on mental health problems as part of educational feedback interventions. Eight, colleges can circulate positive mental health messages, and coping resources to the students, encouraging them to take action to protect their mental health. Lastly, colleges must not forget to actively address the mental health and emotional well-being of the college staff and academicians who have equally been contributing to making students' learning experience worthwhile and promoting students' positive mental health.

4.1.2. Recommendations for the reopening of colleges after periodic lockdowns

Before we look at some further recommendations for the reopening of colleges, some prerequisites must be adopted (Herpich, 2020; The Jed Foundation, 2020; National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences, 2020; Borwankar, 2020; Humphrey and Forbes- Mewett, 2021; Saha et al., 2021; Chaturvedi et al., 2021; Sustarsic and Zhang, 2021; Gomes and Forbes- Mewett, 2021).

-

1.

Though colleges/universities are educational institutes, the focus should not be restricted to strategizing only for educational curriculum but also students' mental well-being. This can be done by ensuring their support via helplines, and online support groups as well as making flexible schedules for academic assignments.

-

2.

Consistent communication should be established with students that should be clear and also compassionate which helps students to stay connected not just to get academic updates but to also feel emotionally rested. Counsellors may provide emotional support to understand how the pandemic may have caused personal distress and understand how they have been coping (or may need support for coping).

-

3.

The teachers and research mentors are close to students; the time of the pandemic may challenge the staff to take on some additional responsibilities in the best interest of the students. Teachers and research mentors may help students with addressing some of their emotional worries relevant to academics.

-

4.

The emotional well-being of everyone on campus should be a priority; along with the well-being of students, and that of the teaching/managing professionals as well. The professionals who have been working tirelessly with additional responsibilities are prone to burnout. Their well-being must be ensured with the right amounts of breaks, shared responsibility and professional support for mental well-being.

-

5.

One more concern that gravitates immediate attention is that of the burnout experience among those college students who have volunteered to provide peer mentorship, and academic help as well as help to address emotional concerns in fellow students. Though these students may have higher grit and stress thresholds, the college must cater to the mental health support among these students (Wang et al., 2020; American Council of Education, 2020). In addition, the following recommendations may deem helpful (OECD, 2020; American Council of Education, 2020; Herpich, 2020; The Jed Foundation, 2020)

-

6.

Employing a comprehensive public health approach to ensure that mental health counselling is a part of the strategic planning of the universities and colleges. The strategic planning must be inclusive of and consider the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and call upon the various experts on the campuses to provide health literacy and strategies to promote healthy habits among students and the staff. Focusing more specifically on students' mental health and well-being by having mental health professionals can help students accommodate better and faster.

4.1.2.1. Crisis communication for students in COVID-19 times

Crisis communication is defined broadly as the collection, processing, and dissemination of information required to address a crisis situation.

-

1.

As students start coming in, there may be a one-year campus campaign focused on mental health awareness and culture change, to cultivate an environment in which students feel encouraged and empowered to care for their mental, physical and emotional well-being. Through the campaign, awareness about mental health may be accelerated and students are informed that their mental health needs will be a priority.

-

2.

Keeping in mind the aftermath of the pandemic, concerted efforts are needed to ensure a culturally sensitive counselling staff. Another area that shall need further exploration and attention is the potential use of digital devices (increased screen time) and interventions for ensuring healthy digital habits for promoting positive mental health.

-

3.

There will be a need for careful examination of how the university can address issues of mental health holistically ensuring inclusiveness, a sense of belonging and compliance to COVID-19 precautions as students slowly return to the campus.

-

4.

Providing clear guidance and mentoring support to faculty and training senior students as peer counsellors can ensure early detection of psychological distress, psychological first-aid and timely referral for specialist care.

-

5.

As some schools are picking up weekly mental health classes, replication of such initiatives for college students may serve as a supportive measure for their mental health.

-

6.

Mental health professionals may encourage staff and students to prioritize self-care, which includes adequate sleep, healthy eating, regular exercise, refraining from substances and taking breaks from academics. Professionals may also ensure that students (and staff) can describe their mental health concerns so they may be helped adequately with the right information about their diagnosis and relevant intervention needed.

-

7.

Colleges should also consider developing collaborative relationships with community-based organizations to help students access appropriate levels of care and should ensure that students maintain communication with the mental health providers, family and along with social support systems to foster their mental health on campus.

-

8.

Unlike school counsellors who are made mandatory for schools by several boards, students of colleges and universities do not have such mandated privileges. Thus, in advocating for students' mental health, the first requirement begins with a greater number of college counsellors and on-campus psychologists at least in LMICs. If not hiring counsellors or psychologists, colleges should establish linkages with mental health professionals where students can access mental health services, periodic workshops and seminars on life skills.

4.2. Strengths and limitations

To our best knowledge, this is the first attempt to review existing literature on mental health consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic in college students and approaches adopted by higher education institutions to reduce adverse academic and psychosocial outcomes. There are several limitations that authors would like to highlight. The present scoping review does not cover the psychosocial impact of COVID-19 on students from marginalized communities due to the limited literature. Although the focus of scoping review was studies from low-middle-income countries (LMIC), few studies from high-income countries (HIC) were included due to limited studies from LMIC. Studies were heterogeneous and limited in its scope thus authors could not separate finding from (HIC) and LMIC. Despite these limitations, the study has significant implications. Findings from the review may help to inform student-centred support programmes and mitigate the long-term negative implications of COVID-19 on student education.

5. Conclusion

Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic are proposed to impact the mental health and wellbeing of college students profoundly; thus, mental health services serve a crucial role in combating the pandemic. College students would benefit from tailor-made coping strategies to meet their specific needs and enhance their psychological resilience. Thus, it is peremptory for colleges, universities and academic institutions to create awareness on mental health needs and concerns, promote healthy habits and lifestyles and emphatically include the provision of primary mental health services (formulating buddy system, empowering students as “peer counsellor”, tele-counselling services, setting up guidance & counselling centre, etc.) and referral services for specialist care. At the same time, creating a conducive environment to address the stigma around mental health and invigorate their students to seek help and support during such public health emergency is crucial. Early interventions may result in improved long-term positive mental health outcomes for college students.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or non-profit sectors.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Apurvakumar Pandya: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. Pragya Lodha: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of competing interest

Authors declare no conflict of interest in the development and production of this manuscript.

Acknowledgements

Nil.

References

- Adedoyin O.B., Soykan E. Covid-19 pandemic and online learning: the challenges and opportunities. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2020:1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Akin-Odanye, et al. Psychosocial impact of COVID-19 on students at institutions of higher learning. Eur. J. Educ. Stud. 2021;8(6):112–128. doi: 10.46827/ejes.v8i6.3770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Council of Education . American Council of Education; Washington: 2020. Mental Health, Higher Education and COVID-19: Strategies for Leaders to Support Campus Well-being. Report. [Google Scholar]

- Arksey H., O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32. [Google Scholar]

- Arsandaux, et al. Mental health condition of college students compared to non-students during COVID-19 lockdown: the CONFINS study. BMJ Open. 2021;11(8) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-053231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bengrut D. Hindustan Times; 9 April, 2020. Covid-19: Pune Colleges, Universities Provide Psychological Counselling to Students. [Google Scholar]

- Borwankar V. Times of India; 2 January, 2020. Mumbai: Schools Start Weekly Mental Health Classes. [Google Scholar]

- Brenes, et al. Telephone-delivered cognitive behavioral therapy and telephone-delivered nondirective supportive therapy for rural older adults with generalized anxiety disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatr. 2015;72(10):1012–1020. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.1154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown S. “Overwhelmed—the real campus mental-health crisis and new models for well-being,” Chron. High Educ., accessed June 1, 2021.

- Chaturvedi K., Vishwakarma D.K., Singh N. COVID-19 and its impact on education, social life and mental health of students: a survey. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2021;121 doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennon A. 2021. Over 9 in 10 College Students Report Mental Health Impacts from COVID-19.https://www.bestcolleges.com/research/college-mental-health-impacts-from-covid-19/ (2021) [Google Scholar]

- Dojchinovska A. 2021. 23 Remarkable Higher Education Statistics.https://markinstyle.co.uk/higher-education-statistics/ [Google Scholar]

- Dorsey E.R., Topol E.J. Telemedicine 2020 and the next decade. Lancet. 2020;395(10227):859. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30424-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan L., Zhu G. Psychological interventions for people affected by the COVID-19 epidemic. Lancet Psychiatr. 2020;7(4):300–302. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30073-0. 2020 Apr. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Harake, et al. Mental health impact of COVID-19 among children and college students: a systematic review. Child Psychiatr. Hum. Dev. 2022;1–13 doi: 10.1007/s10578-021-01297-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleurimond, et al. 2021. College Students' Mental Health and Well-being: Lessons from the Frontlines of COVID-19.https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/insights/industry/public-sector/college-students-mental-health-covid-19.html [Google Scholar]

- Gomes C., Forbes-Mewett H. International students in the time of COVID-19: international education at the crossroads. J. Int. Stud. 2021;11(S2) doi: 10.32674/jis.v11iS2.4292. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grubic N., Badovinac S., Johri A.M. Student mental health in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic: a call for further research and immediate solutions. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatr. 2020 doi: 10.1177/0020764020925108. 0020764020925108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herpich N. Harvard University; USA: 23 July, 2020. Task Force Recommends 8 Ways to Improve Emotional Wellness for Harvard as Issues Rise Nationally. Report. [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey A., Forbes-Mewett H. Social value systems and the mental health of International students during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Int. Stud. 2021;11(S2):58–76. doi: 10.32674/jis.v11iS2.3577. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ibrar M., Chettri S. The Times of India; 3 April, 2020. Universities in Delhi Connect with Students to Help Cope with Uncertainty amid Lockdown. [Google Scholar]

- Jain R. University Grants Commission; India: November 2020. UGC Guidelines for Reopening of Universities and Colleges Post Lockdown Due to the COVID-19 Pandemic. Report. [Google Scholar]

- Kumaraswamy Academic stress, anxiety and depression among college students: a brief review. Int. Rev. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2013;5(1):135–143. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Lalani 2020. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/04/coronavirus-education-global-covid19-online-digital-learning/

- Li, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of college students: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Psychol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra S., Patra B.N. Prevalence of child and adolescent psychiatric disorders in India: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Child Adol Ment. 2014;8(1):22. doi: 10.1186/1753-2000-8-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Education . Ministry of Education Government of India; 2020. Manodarpan.http://manodarpan.mhrd.gov.in/ [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment . 2020. Kiran Mental Health Rehabilitation Helpline: Resource Book.http://niepmd.tn.nic.in/documents/Kiran_resbook.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Moghe K., Kotecha D., Patil M. 2020. COVID-19 and Mental Health: A Study of its Impact on Students.https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.08.05.20160499v1.full.pdf [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences . 2020. Mental Health in the Times of COVID-19 Pandemic.http://nimhans.ac.in/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/MentalHealthIssuesCOVID-19NIMHANS.pdf [Google Scholar]

- O'Hara D. 2020. College Counselors Ensure Students Can Access Mental Health Services during COVID-19.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7712388 [Google Scholar]

- Ochnik, et al. 2021. Mental Health Prevalence and Predictors Among University Students in Nine Countries during the COVID-19 Pandemic: a Cross-National Study.https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-021-97697-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OECD . November 19, 2020. OECD Policy Response to COVID-19. The Impact of COVID-19 on Student Equity and Inclusion: Supporting Vulnerable Students during School Closures and School Reopenings.https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/the-impact-of-covid-19-on-student-equity-and-inclusion-supporting-vulnerable-students-during-school-closures-and-school-re-openings-d593b5c8/ [Google Scholar]

- Pan, et al. Asymptomatic cases in a family cluster with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020;20(4):410–411. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30114-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Population Fund of India . 2020. Understanding the Impact of COVID-19 on Young People.https://populationfoundation.in/understanding-the-impact-of-covid-19-on-young-people/ [Google Scholar]

- Rollman, et al. Effectiveness of online collaborative care for treating mood and anxiety disorders in primary care: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatr. 2018;75(1):56–64. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.3379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy, et al. Mental health implications of COVID-19 pandemic and its response in India. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatr. 2020 doi: 10.1177/0020764020950769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha A., Dutta A., Sifat R.I. The mental impact of digital divide due to COVID-19 pandemic induced emergency online learning at undergraduate level: evidence from undergraduate students from Dhaka City. J. Affect. Disord. 2021;294:170–179. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.07.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahu P. Closure of universities due to Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): impact on education and mental health of students and academic staff. Cureus. 2020;12(4) doi: 10.7759/cureus.7541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suresh R., Alam A., Karkossa Z. Using peer support to strengthen mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: a review. Front. Psychiatr. 2021;12:1119. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.714181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sustarsic M., Zhang J. Navigating through uncertainty in the era of COVID-19: experiences of international graduate students in the United States. Int. J. Stud. 2021;12(1):61–80. doi: 10.32674/jis.v12i1.3305. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- The Hindu . 2020. Center Launches 24/7 Toll-free Mental Health Helpline.https://www.thehindu.com/sci-tech/health/centre-launches-247-toll-free-mental-health-helpline/article32545325.ece [Google Scholar]

- The Jed Foundation . The Jed Foundation; 2020. JED's POV on Student Mental Health and Well-Being in Fall Campus Reopening.https://www.jedfoundation.org/jeds-pov-on-student-mental-health-and-well-being-in-fall-campus-reopening/ [Google Scholar]

- Tricco, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Annals Int. Med. 2018;169(7):467–473. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850. 2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twenge J.M., Campbell W.K. Associations between screen time and lower psychological well-being among children and adolescents: evidence from a population-based study. Prev Med. Rep. 2018;12:271–283. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2018.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO . UNESCO; New Delhi: 2020. Union Minister of Education Launches UNESCO's Mental Health Guide for Students in India.https://en.unesco.org/news/union-minister-education-launches-unescos-mental-health-guide-students-india [Google Scholar]

- University Grants Commission . 2020. Mental Health and Wellbeing of Students.https://www.ugc.ac.in/pdfnews/7012639_Mental-Health-and-Well-Being-of-the-Students.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Verma K. The mental health impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on college students in India. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;53 doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahed W.Y., Hassan S.K. Prevalence and associated factors of stress, anxiety and depression among medical Fayoum University students. Alexandria Med. J. 2017;53(1):77–84. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, et al. Risk management of COVID-19 by universities in China. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2020;36 [Google Scholar]

- YoungMinds . 2020. Coronavirus: Impact on Young People with Mental Health Needs. Report, YoungMinds, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Zhai Y., Du X. Addressing collegiate mental health amid COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatr. Res. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]