Abstract

Positional occlusion of the internal carotid artery is an unusual phenomenon. Reports are scarce in the literature and generally related to compression by external agents when the head is rotated. Cases with no extrinsic etiology are even more uncommon and require high suspicion to avoid misdiagnosis. We present a case of a patient with intermittent internal carotid occlusion depending on the position of the head with no external agent identified. Due to the dynamic characteristics of this presentation, diagnostic tests yielded contradictory results. Carotid ultrasound during neck rotation revealed the positional occlusion. Ultrasound is a versatile technique to explore the carotid arteries in different angles of the neck, useful if positional pathology is suspected.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s40477-020-00490-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Positional occlusion, Head rotation, Carotid ultrasound, Bow´s hunter

Introduction

Positional occlusion of supra-aortic arteries has been seldom reported in the literature. This entity should be suspected in case of transient cerebral symptoms triggered by head movements. Rotation of the head within normal ranges provokes interruption of the flow, and therefore, focal symptoms depending on the impaired artery. The most common presentation is called rotational vertebrobasilar insufficiency or bow´s hunter syndrome [1, 2], when the dominant vertebral artery is compressed during head movements [3]. The carotid system is rarely affected by rotation and it is usually provoked by external agents [4].

Diagnosis should be established after the demonstration of the dynamic occlusion by neuroimaging. Angiography in the provocative position is the gold standard technique. As conventional angiography is an invasive procedure, CT-angiography (CTA) or MR-angiography (MRA) have gained popularity in the assessment of cervical arteries. However, CTA and MRA should be performed with the head still, impeding the evaluation of dynamic changes linked to rotational occlusion. On the other hand, ultrasonography (US) provides real-time information about the blood flow of carotid arteries and allows to explore the vessels at different angles of rotation.

Case report

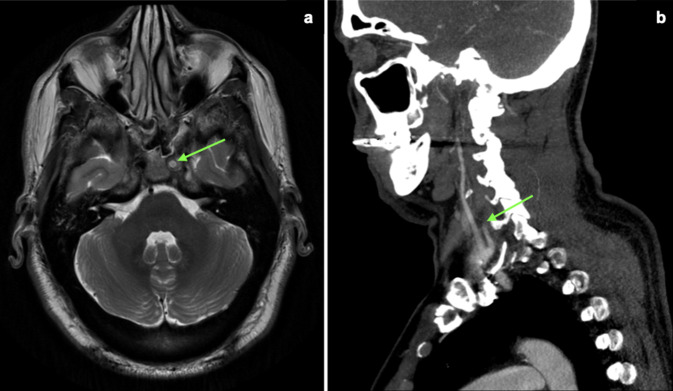

A 56 year old male presented in our clinic complaining of daily headaches with progressive severity during the last 6 months. The headaches usually occurred in the morning, although particularly painful episodes could wake him up at night. His medical history was only remarkable for a seat belt injury from a car accident ten years before the beginning of the symptoms. As part of the diagnostic work-up, a brain MRI was performed revealing loss of normal flow void in the left internal carotid artery (ICA) suggesting proximal occlusion (Fig. 1a).

Fig. 1.

Apparent internal carotid artery (ICA) occlusion. a MRI (T2-weighted, axial plane) showing loss of normal flow void in the left ICA (green arrow) suggesting proximal occlusion. b CT-angiography with abrupt attenuation of flow within the left ICA (green arrow) indicating complete occlusion

To verify if the ICA was occluded, further ancillary tests were ordered. Neck CTA revealed an abrupt attenuation of flow within the left ICA, indicating complete occlusion approximately 2 cm distal to the bifurcation (Fig. 1b). However, carotid ultrasound (US) showed no signs of carotid occlusion. There was an area of stenosis in the mid ICA with systolic peak flow velocity of 302 cm/s, end-diastolic flow velocity of 96 cm/s, and ICA/CCA ratio of 5 at the point of maximum narrowing. These measurements indicated a significant greater than 70% stenosis in the left mid ICA (Fig. 2a). Given the discrepancies, we performed a new carotid US test with the head of the patient at different angles. These maneuvers showed that the presence of the occlusion depended on the head position. When the head was turned to either side, the left ICA remained open with a high-grade stenosis; however, when the head was in the neutral position — as it is positioned during a CT or an MRI — the vessel looked occluded (Fig. 2b, c).

Fig. 2.

Carotid ultrasound demonstrating head-dependent occlusion. a With the head in the neutral position, the internal carotid artery (ICA) looks occluded (green arrow) in cross-sectional view. b With the head turn to the right, the ICA looks open (green arrow) in cross-sectional view. c The mid ICA with velocities suggesting stenosis ≥ 70% (systolic peak velocity flow 302 cm/s, end-diastolic flow velocity 96 cm/s)

Conventional angiography with the head straight confirmed the suspected diagnosis, revealing an 80% stenosis of the post-bulbar segment of the left ICA. The appearance of this lesion resembled an old dissection (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Angiography showing an 80% stenosis of the post-bulbar segment of the left internal carotid artery

Discussion

Rotational occlusions of the cervical arteries are rare. Due to anatomic reasons, neck movements may compress the dominant vertebral artery interrupting the blood flow to the brain [5], receiving the name of Bow-Hunter´s syndrome. Various external enablers as osteofibrous bands, osseous prominences, osteophytes, or atypical vertebral artery anatomical disposition have been related to this entity [6]. In the carotid system, extrinsic compression is also the most common etiology with reports of prominent styloid processes [4], abnormal congenital fascial bands [7], or hypertrophied digastric muscles [8, 9]. Hypoperfusion is not the only mechanism of stroke described. Microemboli have also been documented, the most accepted theory states that extrinsic pressure causes changes in the vessel wall with intimal hyperplasia and fibrosis [10]. Other authors have postulated that tortuosity or kinking of the carotid arteries could have a role among non-compressive etiologies [7, 11].

There is no consensus about the recommended treatment for positional occlusion of the ICA. Surgical removal of the external compressive agent is the most common approach [4, 6–8, 10, 12]. If kinking or tortuosity are identified as responsible for hemodynamic symptoms, surgical correction seems to obtain better results than medical management [13, 14]. However, when no external etiology could be determined, management remains controversial.

In our case report, it is remarkable that we found neither a compressive agent nor an important tortuosity that could justify the dynamic occlusion. Another interesting feature is that the occlusion was noted when the head was in a neutral position, contrary to previous reports where the occlusion happened when the head was rotated. As the lesion revealed in the angiography resembled an old dissection, we hypothesized that a mobile flap could occlude the vessel when the head remained in the neutral position.

The disparity of results between carotid US and CTA is also noteworthy. In these cases, it is important to perform a confirmatory exam. Angiography performed in the suspected position is the most reliable modality [6, 8, 15]. In this patient, US proved to be a versatile method of assessing the carotid arteries in different angles of head rotation.

Conclusions

Despite positional internal carotid artery occlusion is an uncommon entity, this diagnosis should be considered in case of intermittent occlusion. It is usually provoked by extrinsic compression, however, this phenomenon can occur in the absence of identified external agents. In our opinion, carotid US is a rapid and non-invasive technique that allows examination of supra-aortic vessels in different angles of neck rotation if dynamic pathology is suspected.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval

Institutional Review Board approval was not required because this is a case report which did not involve any changes of the routine diagnostic workflow and the standard management of the patient.

Informed consent

For this type of study formal consent is not required.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Jost GF, Dailey AT. Bow hunter’s syndrome revisited: 2 new cases and literature review of 124 cases. Neurosurg Focus. 2015;38(4):E7. doi: 10.3171/2015.1.FOCUS14791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cornelius J, Bostelmann R, Slotty P, El Khatib M, Hanggi D, Steiger H. Hemodynamic stroke: a rare pitfall in cranio cervical junction surgery. J Craniovertebral Junction Spine. 2014;5(3):122. doi: 10.4103/0974-8237.142306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agarwal D, Rezak K, Hines GL. Positional symptomatic occlusion of the internal carotid artery: evaluation and surgical management. Ann Vasc Surg. 2008;22(2):293–296. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2007.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tubbs RS, Loukas M, Dixon J, Cohen-Gadol AA. Compression of the cervical internal carotid artery by the stylopharyngeus muscle: an anatomical study with potential clinical significance. J Neurosurg. 2010;113(4):881–884. doi: 10.3171/2010.1.JNS091407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frisoni GB, Anzola GP. Vertebrobasilar ischemia after neck motion. Stroke. 1991;22(11):1452–1460. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.22.11.1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zaidi HA, Albuquerque FC, Chowdhry SA, Zabramski JM, Ducruet AF, Spetzler RF. Diagnosis and management of Bow Hunter’s syndrome: 15-year experience at Barrow Neurological Institute. World Neurosurg. 2014;82(5):733–738. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2014.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hardin CA, Poser CM. Rotational obstruction of the vertebral artery due to redundancy and extraluminal cervical fascial bands. Ann Surg. 1963;158(1):133–137. doi: 10.1097/00000658-196307000-00025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Etheredge SN, Effeney DJ, Ehrenfeld WK. Symptomatic extrinsic compression of the cervical carotid artery. Arch Neurol. 1984;41(6):672–673. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1984.04210080084020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ballotta E, Thiene G, Baracchini C, Ermani M, Militello C, Da Giau G, et al. Surgical vs medical treatment for isolated internal carotid artery elongation with coiling or kinking in symptomatic patients: a prospective randomized clinical study. J Vasc Surg. 2005;42(5):838–846. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2005.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pozzati E, Nasi MT, Vergoni G, Staffa G, Gaist G. Cerebrovascular insufficiency secondary to extrinsic compression of the internal carotid artery by a fibrous band. Case report Ital J Neurol Sci. 1986;7(6):605–607. doi: 10.1007/BF02341475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bauer R, Sheehan S, Meyer JS. Arteriographic study of cerebrovascular disease. II. Cerebral symptoms due to kinking, tortuosity, and compression of carotid and vertebral arteries in the neck. Arch Neurol. 1961;4:119–131. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1961.00450080001001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nguyen H, Doan N, Eckardt G, Pollock G. Surgical decompression coupled with diagnostic dynamic intraoperative angiography for Bow Hunter′s syndrome. Surg Neurol Int. 2015;6(1):147. doi: 10.4103/2152-7806.165173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Poindexter JM, Patel KR, Clauss RH. Management of kinked extracranial cerebral arteries. J Vasc Surg. 1987;6(2):127–133. doi: 10.1067/mva.1987.avs0060127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grego F, Lepidi S, Cognolato D, Frigatti P, Morelli I, Deriu GP. Rationale of the surgical treatment of carotid kinking. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino) 2003;44(1):79–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Go G, Hwang S-H, Park IS, Park H. Rotational vertebral artery compression : Bow Hunter’s syndrome. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2013;54(3):243. doi: 10.3340/jkns.2013.54.3.243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.