Abstract

Aims

Increasing evidence points towards the use of epicardial fat (EF) as a reliable biomarker of coronary artery disease extent and severity. We aim to assess the different locations of echocardiographic EF thickness measurement and their relation with the presence, extent, and severity of coronary artery disease (CAD) in patients admitted with acute coronary syndromes (ACS).

Methods

Prospective cohort study including patients admitted for ACS. EF was assessed by transthoracic echocardiography and compared with coronary angiography findings. Spearmen correlation analysis was used to search for EF correlations. Receiver-operating characteristic curve analysis was performed to assess the predictive value of the different sites of measurement of EF thickness for the presence of CAD. To evaluate other potential variables independently associated with CAD, we performed multivariate analysis employing logistic regression.

Results

196 patients were included. Significant CAD was diagnosed in 83.7% of patients. In all views, EF thickness was greater in patients with CAD (p < 0.001). We found a moderate correlation between EF thickness and CAD extent and severity. EF thickness measured at RV basal level showed a good performance in predicting significant CAD in patients with ACS (AUC = 0.885, 95% CI 0.80–0.97, p < 0.001). For a value of mean RV basal region EF thickness ≥ 12.57 mm, sensitivity was 85% and specificity was 80.8%.

Conclusion

In patients admitted with ACS, echocardiographic EF thickness predicted the presence of CAD, as well as its extent and severity. We found EF thickness measured at the RV basal region to be the best predictor of significant CAD.

Keywords: Epicardial fat, Coronary artery disease, Echocardiography, Biomarker

Introduction

Epicardial fat (EF) is the adipose tissue surrounding the surface of the heart and epicardial coronary arteries. There is increasing evidence pointing to EF as an active structure, capable of producing several active pro-inflammatory and atherogenic adipokines [1–3]. As such, EF may interact with coronary vessels by paracrine or vasocrine mechanisms, contributing to coronary atherosclerosis and having an inflammatory effect in coronary plaques, leading to plaque instability [1, 4, 5].

There is growing interest in the imaging of EF. Recent studies have shown that the thickness and total volume of EF in patients with coronary artery disease (CAD) are greater compared with patients with no CAD [6–10] and that those same features correlate with CAD severity [7–9, 11]. However, study methods were heterogeneous, leading to conflicting results.

Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) has been used to measure EF. Its accuracy to determine EF has been validated against precise imaging methods such as cardiac magnetic resonance [12, 13]. Nevertheless, little is known about the association between EF assessed with TTE, CAD, and its extent and severity in patients admitted with acute coronary syndrome (ACS). Also, there is no consensus of the region of EF measurement and its clinical relevance remains unknown.

Thus, our objectives are i) to assess the relationship between EF thickness (as measured by echocardiography) and the presence of CAD, its extent and severity in patients admitted with ACS; ii) to study the optimal site for the TTE EF measurement.

Methods

Study participants and variables

We conducted a prospective cohort study including consecutive patients admitted in a coronary care unit (CCU) of a tertiary center with the clinical diagnosis of ACS, between January and April 2018. All patients underwent coronary angiography and TTE during the hospital stay. Patients with a previous history of coronary artery bypass grafting surgery, percutaneous coronary intervention, pericardial disease, and/or pericardial effusion were excluded from the analysis. Clinical and laboratory parameters were collected including weight, height, comorbidities, and laboratory measures, as lipid panel and glomerular filtration rate (calculated with MDRD 4-variable formula) [14]. Chronic kidney disease was defined as glomerular filtration rate < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2, based on the lowest creatinine level obtained during the hospital stay. High-sensitivity cardiac troponin I (Hs-cTnI) and C-reactive protein (CRP) were repeated whenever necessary during the hospital stay. Patients were divided into two groups according to the presence of significant CAD, as defined in the coronary angiography subsection (CAD group and NCAD group).

Coronary angiography

The interventional angiography system in use at our lab is a Siemens® Artis Zee (Siemens AG, Medical Solutions, Erlangen, Germany). A diseased epicardial vessel was defined as a vessel with ≥ 50% luminal stenosis in angiography. The presence of ≥ 1 of such lesions determined the diagnosis of significant CAD. The extent of CAD was quantified taking into account the number of diseased coronary vessels. The angiographic characteristics and complexity of coronary lesions were classified using the SYNTAX score [15], a score able to stratify adverse clinical outcomes after percutaneous coronary intervention [16–18].

Transthoracic echocardiography

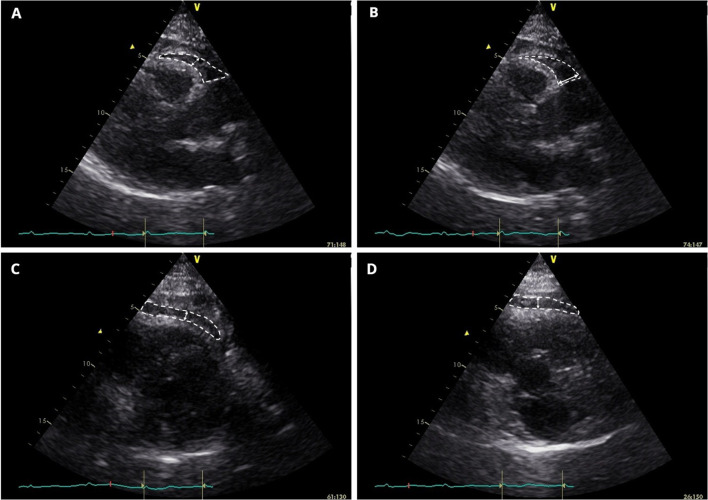

All echocardiograms were performed after coronary angiography, with the patient positioned in left lateral decubitus. Echocardiographers were blinded to the coronary angiography results. Obtained images were then exported to a computer database and processed with EchoPAC® Clinical Workstation Software version 113 (General Electric, Healthcare, Chicago, Illinois) by the same cardiologist, who was blinded to clinical data and angiographic results. Exams were conducted using a General Electric Vivid S6 Ultrasound system and 3Sc-RS tissue harmonics transducer operating with a frequency of 1.4/3.4 MHz. EF measurement included the method proposed by Iacobellis and Willens [19] (PLAXFW) (Fig. 1a). Still, in PLAX view, we positioned the caliper just to the right of the aortic annular plane at the basal region of the RV (PLAXB) (Fig. 1b), as suggested by the same authors [19]. Using parasternal short-axis (PSAX) view, we measured EF at mid-ventricular level (PSAXMV) (Fig. 1c) and in the basal segment of the RV (PSAXB) (Fig. 1d), taking into account the greater thickness of EF in both regions. We also calculated the average value of EF thickness and local mean EF thickness at mid-ventricular and basal levels. EF thickness was measured in millimeters (mm).

Fig.1.

Epicardial fat (within white dashed shape) is identified as the echo-lucent space between the outer myocardium and echo-dense visceral pericardium. The largest local epicardial fat thickness is measured (white arrows). Panel A-B. Parasternal long-axis view, right-ventricular free-wall and basal epicardial fat measurement, respectively. Panel C-D. Parasternal short-axis view, right mid-ventricular and basal epicardial fat measurement, respectively

All EF measures were taken at end-systole. We considered EF as the relatively echo-lucent space between the outer myocardium wall and echo-dense visceral pericardium.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation (± SD) or median with interquartile range (IQR), as adequate, and categorical variables as frequencies or percentages. Categorical variables and continuous variables were compared with Pearson’s χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test and Student t test or Wilcoxon rank-sum test, respectively. Correlations of EF with multiple clinical and biochemical variables were performed by Spearmen correlation analysis. A receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was performed to assess the predictive value of the different measures of EF thickness for the presence of CAD. To evaluate other potential variables independently associated with CAD, we performed multivariate analysis employing logistic regression with a forward conditional method.

The analysis was conducted using IBM® SPSS® Statistics, version 26.0 software. All reported p values were two-sided and p values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Both JF and RM had full access to data and take full responsibility for its integrity.

Interobserver and intraobserver variability

Interobserver and intraobserver variability of PLAXFW, PLAXB, PSAXMV, and PSAXB were assessed employing coefficient of variation (CoV), Bland–Altman method [20] and intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) [21]. Analyses were performed in 40 randomly selected patients, being repeated 2 weeks later by the same echocardiographer to determine intraobserver variability (JF). Interobserver variability was assessed by a second echocardiographer (RM), who repeated the analyses in the same group of patients, comparing obtained values with the first measurement. Both echographers were blinded to the previous measurements.

Results

Characteristics of the study population

A total of 196 patients were included in the study. The median age was 65 years (IQR 18.0) and 74.5% were male. TTE and angiography were performed in 3.6 ± 0.2 and 0.9 ± 0.1 days, respectively, from hospital admission. Diagnosis at admission was ST-elevation acute myocardial infarction (STEMI) in 50.5% (n = 99), non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction in 36.7% (n = 72), and unstable angina in 12.8% (n = 25). Significant CAD was diagnosed in 83.7% (n = 164) of patients, meaning that 16.3% (n = 32) had no CAD or lesions with no clinical significance (< 50% stenosis). Patients in the CAD group were predominantly male (79.9% vs. 46.9%, p < 0.001), more likely to be smokers (44.0% vs. 13.8%, p = 0.002) and to suffer from heart failure (56.3% vs. 29.0%, p = 0.006), compared to the NCAD group. There were no differences between groups regarding previous medication use. Hs-cTnI at admission was higher in CAD group (4983 ± 22,329 vs. 556 ± 1704, ng/L, p = 0.014), as well as peak hs-cTnI (12,291 ± 42,335 vs. 1767 ± 7136, ng/L, p = 0.001) and glycated hemoglobin levels (6.69 ± 1.6 vs. 5.68 ± 0.4, %, p < 0.001). Characteristics of the study population can be seen in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study population

| Variable | All patients (n = 196) | CAD group (n = 164) | No CAD group (n = 32) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Male gender | 146 (74.5%) | 131 (79.9%) | 15 (46.9%) | < 0.001 |

| Age (years) | 65 ± 13 | 65 ± 13 | 66 ± 14 | 0.574 |

| Body mass index (Kg/m2) | 27.8 ± 4.3 | 27.8 ± 4.3 | 28.1 ± 4.5 | 0.692 |

| Medical history (%) | ||||

| Chronic kidney disease | 35 (17.9%) | 30 (18.3%) | 5 (15.6%) | 1.000 |

| Dyslipidemia | 135 (68.9%) | 115 (70.1%) | 20 (64.5%) | 0.531 |

| Diabetes | 65 (33.2%) | 57 (34.8%) | 8 (25.8%) | 0.409 |

| Arterial hypertension | 143 (73.0%) | 122 (74.4%) | 21 (67.7%) | 0.507 |

| Active smoker | 77 (39.3%) | 72 (43.9%) | 5 (16.1%) | 0.004 |

| Previous AMI | 25 (12.8%) | 24 (14.9%) | (3.3%) | 0.136 |

| Previous stroke | 4 (2.0%) | 3 (1.9%) | 1 (3.3%) | 0.498 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 14 (7.1%) | 11 (6.9%) | 3 (10.0%) | 0.467 |

| Familiar history of CAD | 7 (3.6%) | 4 (2.5%) | 3 (10.0%) | 0.046 |

| Heart failure | 99 (50.5%) | 90 (56.3%) | 9 (29.0%) | 0.006 |

| Laboratory tests | ||||

| Peak Hs-cTnI (ng/L) | 12,291 ± 42,335 | 14,239 ± 45,745 | 1767 ± 7136 | 0.001 |

| Glycated hemoglobin (%) | 6.56 ± 1.5 | 6.69 ± 1.6 | 5.0.68 ± 0.4 | < 0.001 |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 118 ± 41 | 119 ± 42 | 109 ± 38 | 0.234 |

| Peak CRP (mg/dL) | 5.21 ± 6.9 | 5.60 ± 7.1 | 3.12 ± 4.6 | 0.17 |

| Echocardiographic features | ||||

| LVEF (%) | 50 ± 9.9 | 49 ± 9.4 | 53 ± 12.2 | 0.083 |

| PLAXFW EF thickness (mm) | 11.3 ± 2.6 | 11.7 ± 2.5 | 9.1 ± 1.9 | < 0.001 |

| PLAXB EF thickness (mm) | 19.3 ± 5.1 | 20.6 ± 4.4 | 13.6 ± 3.7 | < 0.001 |

| PSAXMV EF thickness (mm) | 10.5 ± 2.8 | 11 ± 2.6 | 8.2 ± 2.4 | < 0.001 |

| PSAXB EF thickness (mm) | 10.6 ± 2.8 | 11.1 ± 2.7 | 8.3 ± 2.4 | < 0.001 |

| Mean EF thickness MV segments (mm) | 10.9 ± 2.3 | 11.3 ± 2.1 | 8.7 ± 2.1 | < 0.001 |

| Mean EF thickness basal segments (mm) | 15.0 ± 3.4 | 16.0 ± 2.9 | 11.1 ± 2.8 | < 0.001 |

Epicardial fat assessment

In the PLAX view, the mean PLAXFW EF thickness was 11.3 ± 2.6 mm and the mean PLAXB EF thickness was 19.3 ± 5.1 mm. Regarding the PSAX view, the mean PSAXMV EF thickness was 10.5 ± 2.8 mm and the mean PSAXB EF thickness was 10.6 ± 2.8 mm. Mean EF thickness in the RV mid-ventricular/free-wall segments was 10.9 ± 2.3 mm and the mean EF thickness in the RV basal segments was 15.0 ± 3.4 mm.

Only mean EF thickness in the RV basal segments was higher in men when compared to women (15.5 ± 3.4 vs. 14.0 ± 3.4, mm, p = 0.021). PLAX RV free wall (11.6 ± 2.7 vs. 10.7 ± 2.2, mm, p = 0.028) and mean PLAX EF thickness (15.8 ± 3.7 vs. 14.5 ± 3.2, mm, p = 0.029) were higher in patients with dyslipidemia. PLAX RV free wall (11.6 ± 2.7 vs. 10.7 ± 2.3, mm, p = 0.028), PSAX mid-ventricular RV (10.8 ± 2.9 ± 9.7 ± 2.3, mm, p = 0.013), and mean RV mid-ventricular (11.2 ± 2.4 vs. 10.1 ± 2.0, mm, p = 0.005) EF thickness were higher in patients with arterial hypertension. PSAX mid-ventricular EF thickness was higher in patients taking statins (11.2 ± 3.4 vs. 10.1 ± 2.3, mm, p = 0,045), with no difference regarding other drug use.

EF thickness was consistently greater in all views in patients with CAD: in PLAX view, adjacent to the RV free wall (11.7 ± 2.5 vs. 9.1 ± 1.9, mm, p < 0.001) and basal region (20.6 ± 4.4 vs. 13.6 ± 3.7, mm, p < 0.001) and in PSAX view, at mid-ventricular region (11 ± 2.6 vs. 8.2 ± 2.4, mm, p < 0.001) and basal region (11.1 ± 2.7 vs. 8.3 ± 2.4, mm, p < 0.001).

A more detailed overview of patient characteristics can be seen in Table 1

Association with CAD extent and severity

We found EF thickness to be significantly increased with the extent and severity of CAD. EF was thicker in patients with multivessel disease compared with patients with single-vessel disease: in PLAX view, adjacent to RV free wall (12.2 ± 2.7 vs. 10.9 ± 2.1, mm, p = 0.004) and basal region (21.4 ± 4.2 vs. 18.9 ± 4.5, mm, p = 0.002) and in PSAX view, at mid-ventricular region (11.3 ± 3.05 vs. 10.3 ± 1.9, mm, p = 0.047) and basal region (11.8 ± 2.7 vs. 10.0 ± 2.3, mm, p < 0.001). In patients with SYNTAX score > 12, we found similar results: in PLAX view, adjacent to RV free wall (12.1 ± 2.8 vs. 11.1 ± 2.1, mm, p = 0.021) and basal region (21.1 ± 4.4 vs. 19.2 ± 4.6, mm, p = 0.020) and in PSAX view, at mid-ventricular region (11.3 ± 3.05 vs. 10.2 ± 1.8, mm, p = 0.025) and basal region (11.4 ± 2.6 vs. 10.2 ± 2.5, mm, p = 0.011). A higher SYNTAX score was found to be associated with an increased EF thickness. EF was also significantly correlated with the number of diseased vessels and the number of coronary lesions. Table 2 shows described associations of EF with CAD extent and severity.

Table 2.

Association of epicardial fat with coronary artery disease extent and severity

| Variable | ρ Coefficient | p value |

|---|---|---|

| Association with Syntax score | ||

| PLAXB EF thickness (mm) | 0.402 | < 0.001 |

| Mean EF thickness (mm) | 0.479 | < 0.001 |

| Mean basal EF thickness (mm) | 0.452 | < 0.001 |

| Association with number of diseased coronary vessels | ||

| PLAXB EF thickness (mm) | 0.521 | < 0.001 |

| Mean EF thickness (mm) | 0.536 | < 0.001 |

| Mean basal EF thickness (mm) | 0.518 | < 0.001 |

| Association with number of coronary lesions | ||

| PLAXB EF thickness (mm) | 0.482 | < 0.001 |

| Mean EF thickness (mm) | 0.528 | < 0.001 |

| Mean basal EF thickness (mm) | 0.479 | < 0.001 |

| EF denotes epicardial fat; PLAXB, parasternal long-axis basal right ventricular | ||

ROC curve analysis showed a good performance of EF thickness to predict significant CAD in patients with ACS. The best measure was mean RV basal region EF thickness (area under curve = 0.885, 95% CI 0.80 – 0.97, p < 0.001), as shown in Fig. 2. For a value of mean RV basal region EF thickness ≥ 12.57 mm, sensitivity was 85% and specificity was 80.8%.

Fig.2.

Receiver-operating characteristics (ROC) curves of parasternal long-axis right-ventricular basal region (PLAXB), parasternal long-axis right-ventricular free wall (PLAXFW), parasternal short-axis at mean ventricular level (PSAXMV) and parasternal short-axis at basal RV region [PSAXB) epicardial fat thickness for predicting angiographic significant coronary artery disease. AUC denotes area under the curve

At univariate analysis, active smoking and all measures of EF thickness were predictors of CAD. In a multivariate regression model, which included classic risk factors for CAD, smoking, diabetes, and mean basal RV EF thickness were independent predictors of CAD (Table 3).

Table 3.

Predictors of coronary artery disease in patients with acute coronary syndrome in multivariate regression model

| Variable | Univariate model | Multivariate model | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio (95% CI) | p value | Odds ratio (95% CI) | p value | |

| Age, per year | 0.998 (0.968–1.028) | 0.874 | 0.952 (0.895–1.012) | 0.115 |

| Dyslipidemia | 1.221 (0.530–2.813) | 0.639 | 1.040 (0.243–4.453) | 0.958 |

| Diabetes | 1.688 (0.680–4.186) | 0.259 | 5.907 (1.028–33.932) | 0.046 |

| Arterial hypertension | 1.554 (0.670–3.606) | 0.305 | 5.468 (0.944–31.660) | 0.058 |

| Previous AMI | 4.662 (0.605–35.939) | 0.140 | 2.092 (0.194–22.567) | 0.543 |

| Active smoking | 4.906 (1.635–14.724) | 0.005 | 9.740 (1.372–69.156) | 0.023 |

| Mean RV basal EF, per mm | 1.940 (1.499–2.510) | < 0.001 | 2.433 (1.658–3.571) | < 0.001 |

AMI denotes acute myocardial infarction; EF, epicardial fat; RV, right ventricle

Epicardial fat measurement variability

The interobserver and intraobserver variations were tested and the reproducibility of all measured parameters was good. A complete description of the variability of echocardiographic variables measured can be seen in Table 4.

Table 4.

Variability of echocardiographic variables (n = 40)

| Interobserver variability | Intraobserver variability | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bias (limit of agreement) | ICC (95% CI) | CoV (%) | Bias (limit of agreement) | ICC (95% CI) | CoV (%) | |

| PLAXFW | 0.25 (-1.21; 1.71) | 0.98 (0.97–0.98) | 6.1 | 0.05 (-0.83; 0.93) | 0.99 (0.98–0.99) | 2.5 |

| PLAXB | 1.02 (-0.33; 2.37) | 0.97 (0.95–0.99) | 3.5 | 0.13 (-0.98; 1.23) | 0.98 (0.96–0.99) | 1.7 |

| PSAXMV | 0.49 (-1.11; 2.09) | 0.98 (0.97–0.99) | 6.8 | 0.22(-0.94; 1.38) | 0.99 (0.98–0.99) | 4.4 |

| PSAXB | 0.58 (-0.82; 1.97) | 0.97 (0.95–0.99) | 5.3 | 0.13 (-0.89; 1.13) | 0.99 (0.97–0.99) | 2.9 |

CI denotes confidence interval; CoV, coefficient of variation; ICC, intraclass correlation coefficient; PLAXB, parasternal long-axis basal right ventricular; PLAXFW, parasternal long-axis right-ventricular free wall; PSAXB, parasternal short-axis basal; PSAXMV, parasternal short-axis mid-ventricular

Discussion

In the present study, we sought to determine whether echocardiographic measurement of EF could predict the presence of CAD in a cohort of patients admitted for ACS and what is the best region of EF measurement. We found that EF thickness i) is a sensitive and specific marker of CAD; ii) correlates with both the extent and severity of the disease in patients admitted with the diagnosis of ACS. Also, we found that EF thickness measured at the basal RV region, in parasternal long-axis view, had the best predictive value for significant CAD when compared to other regions of EF measurement.

There is a growing body of evidence suggesting EF is an important player in the development of an unfavorable metabolic and cardiovascular profile. As the cardiac visceral fat, it is known to have an active dichotomous role, both unfavorable and protective. On one hand, EF tends to have higher rates of fatty acid uptake and secretion when compared to other visceral fat depots [22]. As such, EF can work as a buffer, absorbing excess fatty acids and therefore protecting the heart from its effects and as a local energy source in times of higher demand [22]. It has also a role in local distribution and regulation of vascular flow through vasocrine mechanisms [23] and as an immune barrier, protecting the coronary arteries from inflammatory substances [24]. On the other hand, under pathological circumstances, such as diabetes and visceral obesity, increased EF may blunt the toxic effects of fatty acids on the myocardium [25].

EF is considered to be a very active organ that produces several active pro-inflammatory and proatherogenic adipokines [1, 2]. It has been suggested that EF, due to its proximity to the heart and coronary arteries, may interact with them through paracrine or vasocrine secretion of adipokines [4], and, as such, it is legitimate to affirm that EF can have also an inflammatory effect in coronary plaques, amplifying vascular inflammation, and plaque instability [1]. Sacks et al. also postulated the hypothesis that the paracrine secretion of cytokines from EF could traverse the coronary vessel wall and interact with its layers, by entering the vasa vasorum and be transported downstream into the arterial wall [3]. This secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines can be dominant over anti-inflammatory mechanisms in unstable CAD [26]. Ito et al. assessed the association of epicardial fat volume measured with computed tomography with coronary plaque vulnerability using optical coherence tomography. This study found that epicardial fat volume was associated with coronary plaque vulnerability and was also an independent predictor of ACS in patients with CAD [27].

Several observational studies in patients undergoing coronary angiography have found an association between EF thickness measured by echocardiography and the presence and severity of CAD [6–8, 28, 29]. However, the extent of the results has been heterogeneous, as the methods of EF used were different, such as measurement in end-systole or end-diastole, resulting in significant variability in EF thickness. Patients included had different characteristics, ranging from elective referral for coronary angiography to AMI, and some studies did not include patients with normal coronary arteries, which we did in our study. Also, by measuring EF at multiple sites, we compared the predictive power of different sites previously used in other studies and concluded which one had the most predicate power of significant CAD, which can be useful to select the best region of EF measurement in future studies, to minimize heterogeneity.

EF has also been associated with CAD extent and severity. Wang et al. found that in 373 AMI patients undergoing coronary angiography, EF could discriminate patients with high SYNTAX scores and was also a predictor for major in-hospital events [30]. Christensen et al. found that in 1030 patients with type 2 diabetes, high levels of EF were associated with the composite of incident cardiovascular disease and mortality during a mean follow-up of 4,7 years [31]. Other studies also found EF to be associated with SYNTAX score and extent of coronary artery disease [7, 11]. In our study, we found that, in patients admitted with ACS, EF thickness was higher in patients with the presence of significant CAD. Also, we proved that EF was correlated with the SYNTAX score, the number of diseased coronary vessels, and the number of coronary lesions.

Epicardial fat is usually measured in the RV free wall, perpendicularly on the free wall of the RV at end-systole in 3 cardiac cycles [19]. As EF is compressed during diastole, EF is best measured at end-systole [12]. To the best of our knowledge, our study was the first to measure EF in other sites such as basal RV in PLAX and basal RV in PSAX using TTE. We found EF thickness to be greater in RV basal region when compared to other regions, and EF thickness measured at this site and mean RV basal EF were the best predictors of CAD, among classical CAD risk factors such as diabetes and active smoking.

Echocardiographic measurement of EF was first validated by Iacobellis et al., showing a significant correlation between magnetic resonance imaging and TTE measures of EF [12, 13]. Computed tomography also proved to be an excellent tool to evaluate EF [32, 33]. Although the other techniques described can offer a more detailed image of EF, TTE is a cheap, accessible and accurate tool to measure not only EF but also to provide fast and important information in the context of acute coronary syndrome suspicion.

Our study has some limitations: (i) as previously described in the literature, there is some concern on the dispersion and variability in the measurement of EF [34]; (ii) as EF is measured in 2D echocardiography, the regions appraised may not reflect the total epicardial volume as the thickest EF regions may be missed, such as atrioventricular grooves [9, 35]; (iii) our sample was small, and patients were mostly male, mainly in CAD group, as opposed to the NCAD group that consisted of where patients were mostly female. Also, mean RV basal EF was greater in men than in women, which was a small group overall; iv) patients were admitted with the diagnosis of ACS, which can select those with the greatest prevalence of classical coronary risk factors. Previous studies have shown the correlation of metabolic syndrome and thickness of EF [6, 13] and, as such, our control group may represent a population with higher EF at baseline.

Conclusion

In patients admitted with ACS, we confirmed that EF thickness measured with TTE predicted the presence of CAD, as well as its extent, severity, and complexity. Also, EF measured at the basal RV region in parasternal long-axis view, a previously undescribed site, had the best predictive power for significant CAD in the same patients.

Availability of data and materials.

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

JF conceptualized the research, performed transthoracic echocardiograms, elaborated the database, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. RM performed transthoracic echocardiograms, elaborated the database, and analyzed the data. SM, RT, and LG actively discussed the results and reviewed the draft manuscript. JF and RT elaborated the revised manuscript. All the authors have read and approved the manuscript version submitted.

Funding

The author(s) received no specific funding for this work.

Declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval

All procedures performed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. As this is an observational study, the local ethics committee has confirmed that no ethical approval is required.

Consent to participate

Consent was not obtained as procedures were part of patient standard care and there was no concern about identifying information.

Consent for publication

Consent was not obtained as procedures were part of patient standard care and there was no concern about identifying information.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Mazurek T, Zhang LF, Zalewski A, et al. Human epicardial adipose tissue is a source of inflammatory mediators. Circulation. 2003;108(20):2460–2466. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000099542.57313.C5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baker AR, da Silva NF, Quinn DW, et al. Human epicardial adipose tissue expresses a pathogenic profile of adipocytokines in patients with cardiovascular disease. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2006;5:1. doi: 10.1186/1475-2840-5-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sacks HS, Fain JN. Human epicardial adipose tissue: a review. Am Heart J. 2007;153(6):907–917. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iacobellis G, Corradi D, Sharma AM. Epicardial adipose tissue: Anatomic, biomolecular and clinical relationships with the heart. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med. 2005;2(10):536–543. doi: 10.1038/ncpcardio0319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chaldakov GN, Stankulov IS, Aloe L. Subepicardial adipose tissue in human coronary atherosclerosis: another neglected phenomenon. Atherosclerosis. 2001;154(1):237–238. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9150(00)00676-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ahn S-G, Lim H-S, Joe D-Y, et al. Relationship of epicardial adipose tissue by echocardiography to coronary artery disease. Heart. 2008;94(3):e7–e7. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2007.118471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eroglu S, Sade LE, Yildirir A, et al. Epicardial adipose tissue thickness by echocardiography is a marker for the presence and severity of coronary artery disease. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2009;19(3):211–217. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2008.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jeong J-W, Jeong MH, Yun KH, et al. Echocardiographic epicardial fat thickness and coronary artery disease. Circ J. 2007;71(4):536–539. doi: 10.1253/circj.71.536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang T-D, Lee W-J, Shih F-Y, et al. Relations of epicardial adipose tissue measured by multidetector computed tomography to components of the metabolic syndrome are region-specific and independent of anthropometric indexes and intraabdominal visceral fat. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94(2):662–669. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-0834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iwasaki K, Matsumoto T, Aono H, Furukawa H, Samukawa M. Relationship between epicardial fat measured by 64-multidetector computed tomography and coronary artery disease. Clin Cardiol. 2011;34(3):166–171. doi: 10.1002/clc.20840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Altun B, Colkesen Y, Gazi E, et al. Could epicardial adipose tissue thickness by echocardiography be correlated with acute coronary syndrome risk scores. Echocardiography. 2013;30(10):1130–1134. doi: 10.1111/echo.12276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iacobellis G, Assael F, Ribaudo MC, et al. Epicardial fat from echocardiography: a new method for visceral adipose tissue prediction. Obes Res. 2003;11(2):304–310. doi: 10.1038/oby.2003.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iacobellis G, Ribaudo MC, Assael F, et al. Echocardiographic epicardial adipose tissue is related to anthropometric and clinical parameters of metabolic syndrome: a new indicator of cardiovascular risk. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88(11):5163–5168. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levey AS, Coresh J, Greene T, et al. Using standardized serum creatinine values in the modification of diet in renal disease study equation for estimating glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(4):247–254. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-4-200608150-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sianos G, Morel M-A, Kappetein AP, et al. The SYNTAX Score: an angiographic tool grading the complexity of coronary artery disease. EuroIntervention. 2005;1(2):219–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Girasis C, Garg S, Räber L, et al. SYNTAX score and Clinical SYNTAX score as predictors of very long-term clinical outcomes in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary interventions: a substudy of SIRolimus-eluting stent compared with pacliTAXel-eluting stent for coronary revascularizatio. Eur Heart J. 2011;32(24):3115–3127. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wykrzykowska JJ, Garg S, Girasis C, et al. Value of the SYNTAX score for risk assessment in the all-comers population of the randomized multicenter LEADERS (limus eluted from a durable versus ERodable stent coating) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56(4):272–277. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.03.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garg S, Serruys PW, Silber S, et al. The prognostic utility of the SYNTAX score on 1-year outcomes after revascularization with zotarolimus- and everolimus-eluting stents: a substudy of the RESOLUTE All Comers Trial. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2011;4(4):432–441. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2011.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iacobellis G, Willens HJ. Echocardiographic epicardial fat: a review of research and clinical applications. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2009;22(12):1311–1418. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2009.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet. 1986;1(8476):307–310. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(86)90837-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shrout PE, Fleiss JL. Intraclass correlations: uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychol Bull. 1979;86(2):420–428. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.86.2.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marchington JM, Pond CM. Site-specific properties of pericardial and epicardial adipose tissue: the effects of insulin and high-fat feeding on lipogenesis and the incorporation of fatty acids in vitro. Int J Obes. 1990;14(12):1013–1022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yudkin JS, Eringa E, Stehouwer CDA. “Vasocrine” signalling from perivascular fat: a mechanism linking insulin resistance to vascular disease. Lancet (London, England) 2005;365(9473):1817–1820. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66585-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schäffler A, Schölmerich J. Innate immunity and adipose tissue biology. Trends Immunol. 2010;31(6):228–235. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2010.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Iacobellis G, Barbaro G. The double role of epicardial adipose tissue as pro- and anti-inflammatory organ. Horm Metab Res. 2008;40(7):442–445. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1062724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Iacobellis G, Pistilli D, Gucciardo M, et al. Adiponectin expression in human epicardial adipose tissue in vivo is lower in patients with coronary artery disease. Cytokine. 2005;29(6):251–255. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2004.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ito T, Nasu K, Terashima M, et al. The impact of epicardial fat volume on coronary plaque vulnerability: insight from optical coherence tomography analysis. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2012;13(5):408–415. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jes022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yun KH, Rhee SJ, Yoo NJ, et al. Relationship between the echocardiographic epicardial adipose tissue thickness and serum adiponectin in patients with angina. J Cardiovasc Ultrasound. 2009;17(4):121–126. doi: 10.4250/jcu.2009.17.4.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mustelier JV, Rego JOC, González AG, Sarmiento JCG, Riverón BV. Echocardiographic parameters of epicardial fat deposition and its relation to coronary artery disease. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2011;97(2):122–129. doi: 10.1590/S0066-782X2011005000068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang T, Liu Q, Liu C, et al. Correlation of echocardiographic epicardial fat thickness with severity of coronary artery disease in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Echocardiography. 2014;31(10):1177–1181. doi: 10.1111/echo.12545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Christensen RH, Von Scholten BJ, Hansen CS, et al. Epicardial adipose tissue predicts incident cardiovascular disease and mortality in patients with type 2 diabetes. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2019;18(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12933-019-0917-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gorter PM, de Vos AM, van der Graaf Y, et al. Relation of epicardial and pericoronary fat to coronary atherosclerosis and coronary artery calcium in patients undergoing coronary angiography. Am J Cardiol. 2008;102(4):380–385. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dey D, Wong ND, Tamarappoo B, et al. Computer-aided non-contrast CT-based quantification of pericardial and thoracic fat and their associations with coronary calcium and Metabolic Syndrome. Atherosclerosis. 2010;209(1):136–141. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2009.08.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saura D, Oliva MJ, Rodríguez D, et al. Reproducibility of echocardiographic measurements of epicardial fat thickness. Int J Cardiol. 2010;141(3):311–313. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2008.11.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Abbara S, Desai JC, Cury RC, Butler J, Nieman K, Reddy V. Mapping epicardial fat with multidetector computed tomography to facilitate percutaneous transepicardial arrhythmia ablation. Eur J Radiol. 2006;57(3):417–422. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2005.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.