Abstract

Reinfection and reactivation of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) have recently raised public health pressing concerns in the fight against the current pandemic globally. In this study, we propose a new dynamic model to study the transmission of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. The model incorporates possible relapse, reinfection and environmental contribution to assess the combined effects on the overall transmission dynamics of SARS-CoV-2. The model’s local asymptotic stability is analyzed qualitatively. We derive the formula for the basic reproduction number () and final size epidemic relation, which are vital epidemiological quantities that are used to reveal disease transmission status and guide control strategies. Furthermore, the model is validated using the COVID-19 reported situations in Saudi Arabia. Moreover, sensitivity analysis is examined by implementing a partial rank correlation coefficient technique to obtain the ultimate rank model parameters to control or mitigate the pandemic effectively. Finally, we employ a standard Euler technique for numerical simulations of the model to elucidate the influence of some crucial parameters on the overall transmission dynamics. Our results highlight that contact rate, hospitalization rate, and reactivation rate are the fundamental parameters that need particular emphasis for the prevention, mitigation and control.

Keywords: COVID-19, Epidemic model, Reactivation, Reinfection, Reproduction number, Pandemic

Introduction

Emerging and reemerging infectious disease pathogens remain a monumental problem to global public health and socioeconomic ripening [1], [2]. These include coronaviruses and other globally dominated infectious diseases like vector-borne diseases, tuberculosis, sexually transmitted diseases, and meningitis. Coronaviruses are a group of encompassed RNA viruses that primarily circulate or persist among humans (and other mammals) and birds and cause respiratory, neurologic, enteric, and hepatic disease [1]. The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). It emanated from China in December 2019 and was declared a global pandemic on March 11, 2020, by the World Health Organization (WHO) [3].

The COVID-19 pandemic is still in progress and endures in generating disastrous public health and socioeconomic misery worldwide [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11]. By April 15, 2022, the disease had affected more than 220 countries and territories across all regions of the world, causing 500 million cases and 6 million deaths, respectively [12]. Apart from the SARS-COV-2, six other human coronaviruses are known to infect humans, including severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus and middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus [4]. Coronaviruses are likely to reemerge periodically/seasonally in human population owing to recurring cross-species infections and cyclic spillover events [1]. This is plausibly due to the high prevalence and wide geo-distribution of coronaviruses, the enormous heterogeneity of the genetic and persistent recombination of genomes, and the increased human-to-animal interface activities [1].

The COVID-19 vaccines [13], [14] coupled with nonpharmaceutical intervention (NPI) measures (e.g. social distancing, face mask use, quarantine, isolation, contact tracing, travel restrictions, school and border closures) effectively helps in suppressing the impact of the pandemic, especially in terms of severity and mortality cases [12], [15], [16], [17].

Since the emergence of the pandemic, several epidemiological (and clinical) investigations have been performed to examine the transmission dynamics of SARS-CoV-2, ranging from the disease’s clinical characteristics [1], [5], estimation of reproduction number, exponential growth, patterns of the epidemic curve, and epidemic modeling [6], [7], [15], [16], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23]. Some studies have explored the COVID-19 serial interval [24], [25], [26], while some used fractional modeling approach to analyze the transmission of COVID-19 infection [8], [9]. Furthermore, heterogeneity and super-spreading event have also been investigated [27], [28]. In addition, the issue of reactivation [29], [30], [31], [32], [33], [34], [35], [36], and reinfection [37], [38], [39], [40], [41], [42], [43] have also been studied to explore their impact on the overall transmission of SARS-CoV-2.

The scenario of COVID-19 relapse and reinfection has been reported recently [29], [30], [31], [32], [33], [34], [35], [41], [42], [43], [44]. That is, subsequent infection of SARS-CoV-2 by individual after recovery from previous episode of the disease (i.e., a COVID-19 patient can be certified recovered after satisfying the standard discharge criteria) [29], [45]. Re-detectable positive (RP) SARS-CoV-2 can be obtained by using a reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) test from a COVID-19 patient after recovery from a previous infection. Eventually, reinfection and reactivation of SARS-CoV-2 need hasty action by epidemiologists and public health practitioners to advise policymakers and public health authorities on how to control/alleviate the pandemic effectively. SARS-CoV-2 reactivation seems improbable in mildly infected outpatients, especially those with no risk factors for severe infection. A relapse (which is of no or less infectiousness) observed during the first eight weeks of sickness implies that retest or isolation is unneeded [46]. Reinfection of SARS-CoV-2 is typically defined as clinical recurrence of COVID-19 followed by a positive PCR test in ()90 days (on average) after commencement of the primary infection; it usually has reduced infectiousness compared to new infection [39], [46]. Moreover, after a symptom-free interval and re-positive PCR outcomes, the motley of clinical recurrence of SARS-CoV-2 infection has not been researched vastly and may be rare in outpatients. However, it could pose a severe threat to public health, thus, studying this issue is imperatively needed [39], [40].

This paper proposes a new dynamic model for the transmission of the COVID-19 pandemic incorporating the combined effects of reactivation and reinfection, as well as considers environment’s contribution on the overall dynamics of the disease. According to previous studies [35], [42], [44], reactivation and reinfection significantly impact COVID-19 dynamics and evolution, which needs to be investigated broadly to uncover the strength of the disease severity and infectiousness, which mathematical modeling study has not explored extensively.

Following this introductory Section, the other component of the study is assembled as follows: The proposed model is designed in Section “Model Description”. Theoretical analysis and model fitting results are reported in Section “Analytical Results” . Numerical simulation results are also given in Section “Numerical Results”. Finally, brief conclusions of the study are presented in Section “Discussion and Conclusions”.

Model description

To analyze the transmission of COVID-19 through mathematical modeling, we, first of all, downloaded the time-series COVID-19 situations report for Saudi Arabia from the public domain of the WHO disease surveillance system (dashboard), accessible via https://covid19.who.int/ [12].

We designed a new classical model based on traditional SEIR-typed to analyze the transmission of COVID-19 pandemic with consideration of possible relapse/reactivation and reinfection, which has been reported previously [29], [30], [31], [32], [41], [42], [46], [47]. Moreover, our model considers two different modes of transmission, i.e., human-to-human or direct transmission and environment-to-human or indirect transmission [48]. We did not include the zoonotic (animal-to-human) transmission route due to its less infectiousness, especially with the evolving herd immunity caused due to the COVID-19 vaccine or prior exposure to the disease [49], [50], [51], [52].

The total human population given by is partitioned into mutually exclusive classes of susceptible , exposed , asymptomatically infected , symptomatically infected (mild and severe) , hospitalized (mild and severe) and recovered individuals. The parameter represent concentration of the virus in contaminated environment. Thus, the total human population, , is given by

The proposed model is illustrated in Fig. 1, and the state variables and model parameters are given in Table 1. Note that all the parameters are assumed to be non-negative. The models’ systems are, thus, given by Eq. (1) below.

| (1) |

Fig. 1.

COVID-19 epidemic model diagram with reactivation, reinfection and environmental transmission. Parameter is the force of infection (infection rate) representing direct and indirect transmission.

Susceptible humans gain SAR-CoV-2 infection following effective community contact with an infected person or via the contaminated environment, which is time-dependent and is given by

| (2) |

where represents the proportion of SARS-CoV-2 pathogens in the contaminated environment which can cause up to about 50% chance of infection. Infectious individual can contaminate the environment by shading the virus pathogens at rates from , and respectively, while pathogens in the environment decay at a per capita rate . One of the novelties of the proposed model over prior studies is that the current model incorporates the combined effect of relapse, reinfection and environmental contribution with time-varying transmission rate to evaluate the overall transmission dynamics of SARS-CoV-2.

Following previous studies [15], [21], [48], [53], [54], we consider that the contact rate is a time-dependent decreasing function (i.e. decrease with respect to time ), and is given by

| (3) |

where is the contact rate at the initial time, is the minimum contact rate under the current control strategies, and represents the NPI compliance (which provides a measure of public health intervention improvement). For convenience, we normalize the parameter to the interval , that is , which has the following properties:

-

•

representing total non-compliance of the NPI measures by the general public. This further shows that is the target control parameter that provides a measure of public health intervention improvement and should be reduced as much as possible;

-

•

representing total compliance of NPI measures by the general public that is , which is highly unlikely. This further implies that is equivalent to , which indicates 100% of NPI measures, leading to minimal contact and thus minimal transmission rate.

For mathematical convenience, we set in most of results.

Table 1.

Model’s variables and parameters description.

| Variable | Description |

|---|---|

| Total population of individuals | |

| Susceptible individuals | |

| Exposed individuals | |

| Asymptomatically infected individuals | |

| Symptomatically infected individuals | |

| Hospitalized individuals | |

| Recovered individuals | |

| Infectious item on the contaminated environment | |

| Parameter | |

| Time-dependent contact rate | |

| Contact rate before NPIs policy implementation | |

| Minimal contact rate under the current NPIs measure | |

| Rate of NPI measure compliance | |

| Modification parameter for the reduction of infectiousness on | |

| Modification parameter for the reduction of infectiousness on | |

| Per capita rate (daily interaction of individual with environment) | |

| Proportion of SARS-CoV-2 pathogen in the infected environment | |

| Progression rate | |

| Proportion of exposed individuals with clinical symptoms | |

| Hospitalization/isolation rate from | |

| COVID-19 induced death rates | |

| Recovery rates | |

| Environmental contamination rates | |

| Rate of decay of the virus pathogen from the environment | |

| Reinfection rate | |

| Reactivation rates | |

| Hospitalization/isolation rate from | |

Analytical results

Basic epidemiological features of the model

Following [48], by successively applying the procedures of separation of variables and integrating factor on system (1), it ascertains that any solution of system (1) that mimics positive initial conditions will be positive. Also, since the total population of humans, denoted by , is a decreasing function, so that . According to Gronwall inequality, any solution of model (1) will be associated with the compact set given below

whenever , and the constant given by which is the total population. Suppose a solution of the system (1) falls beyond the region (e.g., and for all ), it is obvious that the solution will converge to some point of the closed set . Hence, the model given in Eq. (1) is a dynamical system on the compact set , which is attractive and biologically feasible.

Disease-free equilibrium

In order to analyze the model and obtain some crucial epidemic parameters, first of all, we have to get the disease-free equilibrium (DFE), which is determined below. The disease-free equilibrium of the model (1) is evaluated by equating the right-hand side of the model (1) to zero, which epidemiologically represents a situation where there is no COVID-19 infection in a population. Thus, we have .

Basic reproduction number

The prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 can be evaluated using a threshold quantity, also known as the basic reproduction number, , which is obtained following the next-generation matrix technique (see eqn (5)). It constitutes the number of secondary COVID cases that a typical primary case would cause (i.e., by an infected person or through contact with a pathogen infested material) during the infectious period in a wholly susceptible population [54], [55], [56], [57], [58], [59], [60], [61].

Thus, the associated next-generation matrices, representing the new infection terms and the transition terms, respectively, and are given by

| (4) |

with , , .

Thus, the basic (or control) reproduction number, , are given by

| (5) |

where (spectral radius) is essentially the maximum eigenvalues of the next generation matrix, , and and are respectively given by

| (6) |

The quantities and given in (6) measure the contributions from human-to-human (via respiratory route) and environment-to-human (via the contaminated environment), respectively, to the overall infection risk at time . Thus, the result below is in line with the results of Theorem 2 of [56].

Theorem 1

The DFE,, of the model (1) , is locally-asymptotically stable (LAS) inside the biologically-feasible region, , if , and unstable if .

The basic reproduction number () is one of the most crucial epidemiological quantities that guide the control and prevention of emerging infectious diseases. Epidemiologically, the result established in Theorem 1 above insinuates that would not bring a large outbreak of COVID-19. Whereas for , a severe outbreak could happen. Furthermore, the need for making for model (2) is only adequate but not mandatory for COVID-19 mitigation efforts. Hence SARS-COV-2 can be eradicated with time when and spreads when . To achieve this, there is a need to monitor the contribution of human-to-human and environment-to-human transmission of COVID-19 in order to enhance mitigation processes. Therefore, strict containment measures are also necessary to prevent further transmission.

Final size epidemic relation

In this subsection, we obtained the final size epidemic relation for the COVID-19 pandemic by adopting previous technique [15], [48], [62]. With the expression of in Eq. (5), we consider constant contact rates, i.e., and . The result to be computed here helps estimate the severity of the outbreak with respect to its final size relations used previously [62] and was recently adopted for COVID-19 models [15], [48].

Theorem 2

Suppose and . Let and represent respectively the column vector and the row vector . Thus, we have:

- 1.

Consider the functions , and which satisfy the fallowing propertieswhere denote the final size epidemic to be computed.

(7) - 2.

The final epidemic size relation is given bywhere or , and the inverse matrix was adopted for computing .

(8)

To obtain the final epidemic size given in (8), we assumed some initial conditions to be zero, i.e., and [15], [62]. So that, by determining the matrix , we can simply obtain the following lower bound for the final epidemic size relation (8):

| (9) |

The term represent the “infection attack rate”, which determines the proportion of the population severely infected by susceptible individuals, , who scarpers the infection during the outbreak [63]. The severity of the epidemic largely depends on the attack rate, which significantly increases the cumulative number of disease cases (). Following [64], Theorem 2 indicates that, irrespective of the value of , the epidemic will die out, not because of the pandemic fatigue only, but also due to the effectiveness of the interventions strategies.

Numerical results

Model fitting

In this subsection, we adopted similar approach as in [23], [65], [66] for model fitting/validation processes. We fitted the proposed model to the SARS-CoV-2 situations report for Saudi Arabia for the data from December 20, 2021, to March 20, 2022 (third wave), obtained from the public domain of the WHO dashboard for COVID-19 situations reports [12] (see Fig. 2). We employed chi-square distribution and estimated the following parameters: , , , and . The initial conditions used for the fitting processes are: ; ; ; ; ; ; and . Using the estimated parameters and other parameters given in the Table 2, we computed the given in Eq. (5) as 3.672442. The estimation of the in the current study is consistent with previous results (see, for instance, [67] and the references therein).

Fig. 2.

Fitting results of the COVID-19 model (1) using the reported data in Saudi Arabia from December 20, 2021, to March 20, 2022 (third wave). In each panel, the sand color dots denote the observed COVID-19 cases, and the black lines represent the model prediction to the reported data. The result in the left panel shows the cumulative number of COVID-19 instances, and the result in the right panel shows the daily reported COVID-19 situations in Saudi Arabia. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Table 2.

Ranges of the parameters and their units used for the simulations.

| Parameter | Value (Range) | Units/Remarks | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| – | Fitted | ||

| – | [48] | ||

| – | [48] | ||

| – | [15], [68] | ||

| – | [15], [68] | ||

| – | [48] | ||

| Estimated by [69], [70] | |||

| – | [71], [72] | ||

| – | [15], [72] | ||

| – | [22], [72] | ||

| – | [22], [73] | ||

| – | [22], [73] | ||

| – | [15], [72] | ||

| – | [15], [72], [74] | ||

| – | [22], [72] | ||

| – | [48] | ||

| – | [48] | ||

| – | [48] | ||

| – | [48] | ||

| – | Fitted | ||

| – | Fitted | ||

| – | Fitted | ||

| – | [48], [68] |

Numerical simulations

In this part, numerical simulations were carried out to explain the theoretical results given in the previous sections as well as to gain deeper insight into the COVID-19 dynamic transmission behavior. To obtain numerical solutions to the proposed model, we employed the Euler framework to find the graphical results using parameter values from Table 2 [8], [9], [10], [11], [75], [76], [77]. The procedure is as follows: Suppose the initial condition, which is well-posed, is given below.

| (10) |

a sequence of approximation point is formed by Euler method to exact solutions of ordinary differential equation by and , and .

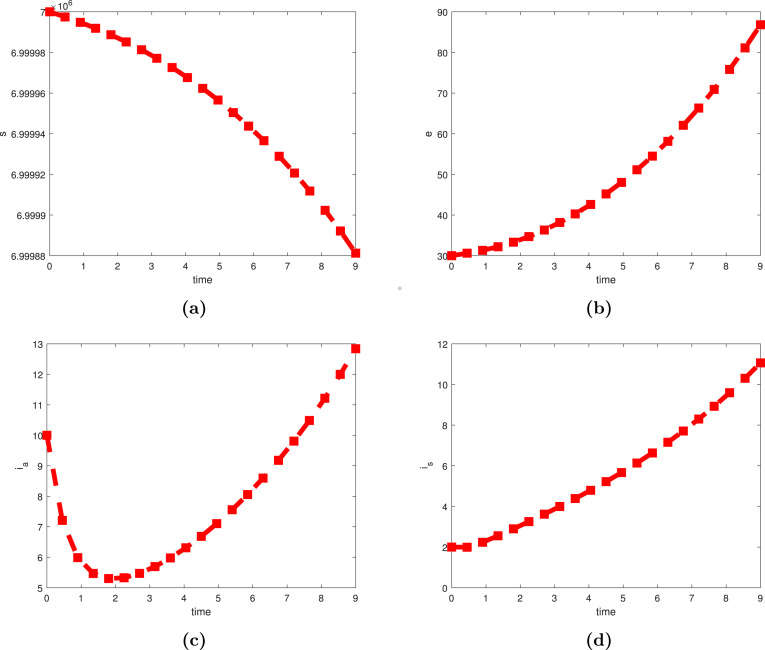

We analyzed the respective numerical dynamic of each of the state variables of the model (1) namely (Susceptible individuals), (exposed individuals), (asymptomatically infected individuals), (symptomatically infected individuals), (hospitalized individuals), (recovered individuals), and (infectious item on the contaminated environment) as can be seen in Fig. 3, Fig. 4. In addition, there are several significant factors for the chosen COVID-19 model under consideration that must be examined for their growing or lowering values. In this regard, we have picked certain parameters due to their epidemiological impact on transmission such as , , , , . In Fig. 5(a) and (b), we show that raising the value of would slightly cause the infection to expand significantly, but increasing the rate of progression rate leads the exposed population to rise immensely. Such manners exemplify the pandemic’s theoretical observations. For increasing and decreasing values of reactivation rates, Fig. 6(a) and (b), a slight increase or decrease in the disease’s reactivation rate from the asymptomatically and symptomatically infection’s stage propels infectious individuals to the top, which is consistent with real phenomenon observed experimentally for the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. Another critical parameter is the COVID-19 induced mortality rate, which was found to be changed with various proper values to evaluate how the model’s behavior changes; this is depicted in Fig. 7.

Fig. 3.

Simulation results of the COVID-19 pandemic model showing the dynamics behavior over the time period. Profiles of the variables , , , and are portrayed in (a), (b), (c), and (d), respectively.

Fig. 4.

Simulation results of the COVID-19 pandemic model showing the dynamics behavior over the time period. Profiles of the variables , , and are portrayed in (a), (b), and (c), respectively.

Fig. 5.

Dynamic behavior of the proposed model with changing values of and in (a) and (b), respectively.

Fig. 6.

Dynamic behavior of the proposed model with changing values of and in (a) and (b), respectively.

Fig. 7.

Dynamic behavior of the proposed model with changing values of .

Sensitivity analysis

Following previous studies [55], [78], we employed the partial rank correlation coefficient (PRCC) to investigate sensitivity analysis. The PRCC of the and the infection attack rate of the system (1) are evaluated. The sensitivity analysis results depicted in Fig. 8 reveal top-ranked parameter to be accentuated in controlling the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic is the contact/transmission rate (), per capita rate of susceptible individuals who mingle with the environment per day (), and the proportion of SARS-CoV-2 pathogens present in the environment (). Other top-ranked parameters apart from the ones mentioned include the rate of decay of the virus pathogen from the environment () and environmental contamination rates ().

Fig. 8.

The partial rank correlation coefficients (PRCC) of basic reproduction number () and infection attack rate versus the model’s parameters.

Discussion and conclusions

Since COVID-19 pandemic started in early 2020 [3], [79], non- pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) measures have been playing a pivotal role in halting the number of cases and deaths [80], [81], despite the increasing rate of vaccination worldwide [13], [14]. This paper proposed an SEIR-based epidemic model that incorporated direct and indirect transmission as the potential transmission pathways of COVID-19. The model also included possible relapse and reinfection of SARS-CoV-2 from a recovered patient who satisfied all the standard discharge procedures from the previous episode of the infection [31], [42], [44].

Some of the key epidemiological findings of the present study are outlined as follows:

-

(i)

The basic reproduction number, of the model was determined (see Eqs. (5), (6)), which measures the potential transmission for an outbreak. It depends on the transmission coefficient and the average duration of infectiousness during the epidemic period. and indicates that the disease will die out and persists, respectively. Thus, the elimination of an infectious disease requires that must be reduced to one either by vaccination or via other intervention strategies, such as public awareness programs [82].

-

(ii)

We analytically computed the final size of epidemic relations for the simplified model (i.e., by considering human-to-human transmission route only) to give an account of the rough epidemic size over the cause of the epidemics period [62], [83]. The simplified version of the model was used in computing the final epidemic size relations due to the complexity of the full model and the fact that likely no significant changes could be detected even if the fundamental model was used.

-

(iii)

The proposed model was fitted to the COVID-19 situation reports in Saudi Arabia for the third wave, i.e., for the data from December 20, 2021, to March 20, 2022. Our numerical results show that the fitting results nicely represented the actual situation and were adopted to estimate other crucial parameters of the model that are useful for control and mitigation strategy and could be used to predict future scenarios of the disease outbreak.

-

(iv)

Furthermore, by using the and infection attack rates as response functions, we conducted the sensitivity analysis, which demonstrates the highest PRCCs ranked parameters (i.e., , , and ), which are relevant to environmental influence on the overall transmission of SARS-CoV-2. Hence, this study determines the parameters that should be targeted for effectual control of the pandemic. Other peak parameters with high ranked PRCCs (but not as high as the most sensitive ones) are the rate of decay of the pathogen from the environment () as well as environmental contamination rates ().

-

(v)

Finally, we performed numerical simulations to portray the impact of the model’s parameters on the overall transmission dynamics. In particular, Fig. 3, Fig. 4 showed the general dynamics behavior of SARS-CoV-2 dynamics in each sub-population and how they affect the overall effect transmission. In Fig. 5(a), we showed that increasing the value of would slightly increase the epidemic impacts significantly, thereby increasing the transmission rate. We also showed a slight increase or decrease in the disease’s activation rate from the asymptomatically and symptomatically infection stage propels the infectious population to the top; thus, it could not affect the overall transmission dynamics. Similarly, in Eq. (6)(a) and (b), increase in and likely increase the transmission. Moreover, a decrease in in Eq. (7) significantly helps suppress the transmission.

In summary, this study designed an SEIR-typed model to qualitatively investigate the transmission dynamics of COVID-19 incorporating the relapse, reinfection and environmental transmission to get more profound knowledge of its transmission potential and provide suggestions for effective control. In addition, we obtained some crucial epidemiological parameters that need more emphasis for mitigation and control of the COVID-19 pandemic. Our results showed that , , and are the key parameters that should be prioritized to control the epidemics. Those parameters could help to maintain disease transmission at a low level with minimal socio-economic distraction and play an essential role, especially in the public health and policy-making sectors, in generating a continuous and imperishable plan to mitigate against the effects of the still ongoing pandemic.

Hitherto, several studies revealed that reactivation or reinfection causes less or no severe infection in vulnerable people; however, health workers and authorities should be prudent in declaring recovery for SARS-CoV-2 patients [39], [40], [44], [84]. Thus, it is imperative to monitor recovered patients to prevent subsequent transmission.

The current study has some limitations. The proposed model is a time-dependent model, which makes it non-autonomous. Thus, analyzing it theoretically, particularly if more vital dynamics are incorporated (such as seasonality factors), will be challenging, requiring the design of a new mathematical theory and methodology. Further, characterizing bifurcation types for non-autonomous models is essential and will be considered in future work by extending the current study. Furthermore, the current study can be extended by employing an artificial neural network scheme to solve the model of the nonlinear dynamics for COVID-19 or by using a stochastic algorithm framework as proposed by previous studies [85], [86], [87], [88], [89], which would significantly help in prevention and mitigation strategies of emerging infectious diseases.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Salihu S. Musa: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Abdullahi Yusuf: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Shi Zhao: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Zainab U. Abdullahi: Writing – original draft, Revision. Hammoda Abu-Odah: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Farouk Tijjani Saad: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Lukman Adamu: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Daihai He: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the Handling Editor and the anonymous reviewers, whose comments have remarkably contributed to improving the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Since no individual data was used, neither ethical approval nor personnel consent was needed.

Availability of data and materials

The COVID-19 reported data used in this work were freely obtained from the public domains of the WHO dashboard via https://covid19.who.int/.

References

- 1.Zhu N., Zhang D., Wang W., Li X., Yang B., Song J., et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:727–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gao GF. From A IV to Z IKV: attacks from emerging and re-emerging pathogens. Cell. 2018;172(6):1157–1159. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.02.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization; 2020. WHO coronavirus disease (Covid-19) pandEmic. https://www.who.int/ (Accessed 17 October 2021) [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gilbert M, Pullano G, Pinotti F, Valdano E, Poletto C, Boëlle PY, et al. Preparedness and vulnerability of African countries against importations of COVID-19: a modelling study. Lancet 395(10227):871–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Huang C., Wang Y., Li X., Ren L., Zhao J., Hu Y., et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li Q., Guan X., Wu P., Wang X., Zhou L., Tong Y., et al. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1199–1207. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhao S., Lin Q., Ran J., Musa SS., Yan G., Wang W., et al. Preliminary estimation of the basic reproduction number of novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in China, from 2019 to 2020: A data-driven analysis in the early phase of the outbreak. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;92:214–217. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.01.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khan MA., Atangana A. Mathematical modeling and analysis of COVID-19: A study of new variant Omicron. Physica A. 2022 doi: 10.1016/j.physa.2022.127452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Atangana A., Araz Sİ. Springer Nature; 2022. Fractional stochastic differential equations: applications to covid-19 modeling. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Din A., Li Y. Controlling heroin addiction via age-structured modeling. Adv Difference Equations. 2020;2020(1):1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Din A., Li Y., Khan T., Zaman G. Mathematical analysis of spread and control of the novel corona virus (COVID-19) in China. Chaos Solitons Fractals. 2020;141 doi: 10.1016/j.chaos.2020.110286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization; 2020. WHO coronavirus disease (Covid-19) dashboard. https://covid19.who.int/ (Accessed 20 December 2020) [Google Scholar]

- 13.COVID-19 Vaccine Tracker . 2020. COVID-19 vaccine and therapeutics tracker. https://biorender.com/covid-vaccine-tracker (Accessed 10 October, 2021) [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization; 2020. Global regions. Covid-19 vaccines. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/covid-19-vaccines (Accessed 10 October, 2021) [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eikenberry SE., Mancuso M., Iboi E., Phan T., Eikenberry K., Kuang Y., Kostelich E., Gumel AB. To mask or not to mask: Modeling the potential for face mask use by the general public to curtail the COVID-19 pandemic. Infect Dis Model. 2020;5:293–308. doi: 10.1016/j.idm.2020.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Musa SS., Zhao S., Wang MH., Habib AG., Mustapha UT., He D. Estimation of exponential growth rate and basic reproduction number of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Africa. Infect Dis Poverty. 2020;9:96. doi: 10.1186/s40249-020-00718-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Musa SS., Tariq A., Yuan L., Haozhen W., He D. Infection fatality rate and infection attack rate of COVID-19 in South American countries. Infect Dis Poverty. 2022;11(40) doi: 10.1186/s40249-022-00961-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ma J. Estimating epidemic exponential growth rate and basic reproduction number. Infect Dis Model. 2020;5:129–141. doi: 10.1016/j.idm.2019.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Musa SS., Zhao S., Hussaini N., Zhuang Z., Wu Y., Abdulhamid A., Wang MH., He D. Estimation of COVID-19 under-ascertainment in Kano, Nigeria during the early phase of the epidemics. Alexendria Eng J. 2021;60(5):4547–4554. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhao S., Musa SS., Lin Q., Ran J., Yang G., Wang W., Lou Y., Yang L., Gao D., He D., Wang MH. Estimating the unreported number of novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) cases in China in the first half of 2020: a data-driven modelling analysis of the early outbreak. J Clin Med. 2020;9(2):388. doi: 10.3390/jcm9020388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tang B., Bragazzi NL., Li Q., Tang S., Xiao Y., Wu J. An updated estimation of the risk of transmission of the novel coronavirus (2019-nCov) Infect Dis Model. 2020;5:248–255. doi: 10.1016/j.idm.2020.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Musa SS., Gao D., Zhao S., Yang L., Lou Y., He D. Mechanistic modeling of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in the early phase in Wuhan, China, with different quarantine measures. Acta Math Appl Sin. 2020;43(2):350–364. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Musa SS., Baba IA., Yusuf A., Sulaiman TA., Aliyu AI., Zhao S., He D. Transmission dynamics of SARS-CoV-2: A modeling analysis with high-and-moderate risk populations. Results Phys. 2021;26 doi: 10.1016/j.rinp.2021.104290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nishiura H., Linton NM., Akhmetzhanov AR. Serial interval of novel coronavirus (COVID-19) infections. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;93:284–286. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.02.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Du Z., Xu X., Wu Y., Wang L., Cowling BJ., Meyers LA. Serial interval of COVID-19 among publicly reported confirmed cases. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26(6):1341. doi: 10.3201/eid2606.200357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhao S., Cao P., Gao D., Zhuang Z., Cai Y., Ran J., et al. Serial interval in determining the estimation of reproduction number of the novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) during the early outbreak. Travel Med. 2020;27(3) doi: 10.1093/jtm/taaa033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang L., Didelot X., Yang J., Wong G., Shi Y., Liu W., Gao GF., Bi Y. Inference of person-to-person transmission of COVID-19 reveals hidden super-spreading events during the early outbreak phase. Nature Commun. 2020;11(1):5006. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-18836-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang Y., Li Y., Wang L., Li M., Zhou X. Evaluating transmission heterogeneity and super-spreading event of COVID-19 in a metropolis of China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(10):3705. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17103705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lan L., Xu D., Ye G., Xia C., Wang S., Li Y., Xu H. Positive RT-PCR test results in patients recovered from COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;323(15):1502–1503. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mei Q., Li J., Du R., Yuan X., Li M., Li J. Assessment of patients who tested positive for COVID-19 after recovery. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(9):1004–1005. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30433-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tang X., Zhao S., He D., Yang L., Wang MH., Li Y., et al. Positive RT-PCR tests among discharged COVID-19 patients in Shenzhen, China. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2020;41(9):1110–1112. doi: 10.1017/ice.2020.134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.An J., Liao X., Xiao T., Qian S., Yuan J., Ye H., et al. Clinical characteristics of recovered COVID-19 patients with re-detectable positive RNA test. Ann Transl Med. 2020;8(17):1084. doi: 10.21037/Fatm-20-560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen Y., Bai W., Liu B., Huang J., Laurent I., Chen F., et al. Re-evaluation of retested nucleic acid-positive cases in recovered COVID-19 patients: Report from a designated transfer hospital in Chongqing, China. J Infect Public Health. 2020;13(7):932–934. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2020.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lafaie L., Célarier T., Goethals L., Pozzetto B., Grange S., Ojardias E., Annweiler C., Botelho-Nevers E. Recurrence or relapse of COVID-19 in older patients: a description of three cases. J Amer Geriatr Soc. 2020;68(10):2179–2183. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yuan B., Liu HQ., Yang ZR., Chen YX., Liu ZY., Zhang K., Wang C., Li WX., An YW., Wang JC., Song S. Recurrence of positive SARS-CoV-2 viral RNA in recovered COVID-19 patients during medical isolation observation. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):11887. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-68782-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Murray CJ., Piot P. The potential future of the COVID-19 pandemic: will SARS-CoV-2 become a recurrent seasonal infection? JAMA. 2021;325(13):1249–1250. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.2828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Overbaugh J. Understanding protection from SARS-CoV-2 by studying reinfection. Nat Med. 2020;26(11):1680–1681. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-1121-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Boyton RJ., Altmann DM. Risk of SARS-CoV-2 reinfection after natural infection. Lancet. 2021;397(10280):1161–1163. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00662-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Prete CA., Buss LF., Buccheri R., Abrahim CM., Salomon T., Crispim MA., Oikawa MK., Grebe E., Costa AG.da., Fraiji NA., Carvalho M.do.PSS. Reinfection by the SARS-CoV-2 Gamma variant in blood donors in manaus, Brazil. BMC Infect Dis. 2022;22(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12879-022-07094-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Abu-Raddad LJ., Chemaitelly H., Ayoub HH., Tang P., Coyle P., Hasan MR., Yassine HM., Benslimane FM., Al-Khatib HA., Al-Kanaani Z., Al-Kuwari E. Relative infectiousness of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine breakthrough infections, reinfections, and primary infections. Nature Commun. 2022;13(1):1. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-28199-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.To KK., Hung IF., Ip JD., Chu AW., Chan WM., Tam AR., et al. COVID-19 re-infection by a phylogenetically distinct SARS-coronavirus-2 strain confirmed by whole genome sequencing. Clin Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Murillo-Zamora E., Mendoza-Cano O., Delgado-Enciso I., Hernandez-Suarez CM. Predictors of severe symptomatic laboratory-confirmed SARS-COV-2 reinfection. Public Health. 2021;193:113–115. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2021.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Duggan NM., Ludy SM., Shannon BC., Reisner AT., Wilcox SR. Is novel coronavirus 2019 reinfection possible? Interpreting dynamic SARS-CoV-2 test results. Amer J Emerg Med. 2020;39:256–e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2020.06.079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tang X., Musa SS., Zhao S., He D. Reinfection or reactivation of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2: A systematic review. Front Public Health. 2021;9 doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.663045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.WHO; 2020. World health organization (WHO) criteria for releasing covid-19 patients from isolation. Available from https://www.who.int/news-room/commentaries/detail/criteria-for-releasing-covid-19-patients-from-isolation (Accessed on 15 November 2020) [Google Scholar]

- 46.Buskermolen M., Paske K.Te., Beek J.van., Kortbeek T., Götz H., Fanoy E., Feenstra S., Richardus JH., Vollaard A. Relapse in the first 8 weeks after onset of COVID-19 disease in outpatients: Viral reactivation or inflammatory rebound? J Infect. 2021;83(2):e6–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2021.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC); 2020. Reinfection with SARS-CoV: Considerations for public health response: ECDC. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/reinfection-and-viral-shedding-threat-assessment-brief.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Garba SM., Lubuma JM., Tsanou B. Modeling the transmission dynamics of the COVID-19 pandemic in South Africa. Math Biosci. 2020;328 doi: 10.1016/j.mbs.2020.108441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lin Q., Zhao S., Gao D., Lou Y., et al. A conceptual model for the outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in wuhan, China with individual reaction and governmental action. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;93:211–216. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.02.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Burki TK. Herd immunity for COVID-19. Lancet Respir Med. 2021;9(2):135–136. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30555-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.He D., Artzy-Randrup Y., Musa SS., Stone L. The unexpected dynamics of COVID-19 in manaus, Brazil: Was herd immunity achieved? MedRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1101/2021.02.18.21251809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Britton T., Ball F., Trapman P. A mathematical model reveals the influence of population heterogeneity on herd immunity to SARS-CoV-2. Science. 2020;369(6505):846–849. doi: 10.1126/science.abc6810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.He D., Dushoff J., Day T., Ma J., Earn DJ. Inferring the causes of the three waves of the 1918 influenza pandemic in England and Wales. Proc R Soc Biol Sci. 2013;280(1766) doi: 10.1098/rspb.2013.1345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.He D., Wang X., Gao D., Wang J. Modeling the 2016–2017 Yemen cholera outbreak with the impact of limited medical resources. J Theoret Biol. 2018;451:80–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2018.04.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Musa SS., Zhao S., Gao D., Lin Q., Chowell G., He D. Mechanistic modelling of the large-scale lassa fever epidemics in Nigeria from 2016 to 2019. J Theoret Biol. 2020;493 doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2020.110209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Driessche P.van.den., Watmough J. Reproduction numbers and sub-threshold endemic equilibria for compartmental models of disease transmission. Math Biosci. 2002;180:29–48. doi: 10.1016/S0025-5564(02)00108-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Driessche P.van.den. Reproduction numbers of infectious disease models. Infect Dis Model. 2017;2(3):288–303. doi: 10.1016/j.idm.2017.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Diekmann O., Heesterbeek J., Metz J. On the definition and the computation of the basic reproduction ratio,, in models for infectious diseases in heterogeneous populations. J Math Biol. 1990;28:365–382. doi: 10.1007/BF00178324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mustapha UT., Musa SS., Lawal MA., Abba A., Hincal E., Mohammed MD., Garba BD., Yunus RB., Adamu SA. Mathematical modeling and analysis of schistosomiasis transmission dynamics. Int J Model Simul Sci Comput. 2020;11(3):1–19. doi: 10.1142/S1793962321500215. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Din A., Khan T., Li Y., Tahir H., Khan A., Khan WA. Mathematical analysis of dengue stochastic epidemic model. Results Phys. 2021;20 [Google Scholar]

- 61.Din A., Li Y. Controlling heroin addiction via age-structured modeling. Adv Difference Equations. 2020;2020(1):1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Arino J., Brauer F., Driessche P.van.den., Watmough J., Wu J. A final size relation for epidemic models. Math Biosci Eng. 2007;4(2):159. doi: 10.3934/mbe.2007.4.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Brauer F., Castillo-Chavez C. second ed. Springer; 2012. Mathematical models in population biology and epidemiology. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kermack WO., McKendrick AG. A contribution to the mathematical theory of epidemics. Proc R Soc Lond Ser A Math Phys Eng Sci. 1927;115(772):700–721. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hussaini N., Okuneye K., Gumel AB. Mathematical analysis of a model for zoonotic visceral leishmaniasis. Infect Dis Model. 2017;2(4):455–474. doi: 10.1016/j.idm.2017.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Okuneye KO., Velasco-Hernandez JX., Gumel AB. The unholy chikungunya–dengue–Zika trinity: a theoretical analysis. J Biol Syst. 2017;25(04):545–585. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Alajlan SA., Alhusseini NK., Asdaq SM., Mohzari Y., Alamer A., Alrashed AA., Alamri AS., Alsanie WF., Alhomrani M. The impacts OF lockdown strategies on the basic reproductive number of coronavirus (COVID-19) cases in Saudi Arabia. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2021;28(9):4926–4930. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2021.06.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ngonghala CN., Iboi E., Eikenberry S., Scotch M., MacIntyre CR., Bonds MH., Gumel AB. Mathematical assessment of the impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions on curtailing the 2019 novel coronavirus. Math Biosci. 2020;325 doi: 10.1016/j.mbs.2020.108364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kim JH., Mogasale V., Burgess C., Wierzba TF. Impact of oral cholera vaccines in cholera-endemic countries: A mathematical modeling study. Vaccine. 2016;34(18):2113–2120. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yang C., Wang X., Gao D., Wang J. Impact of awareness programs on cholera dynamics: two modeling approaches. Bull Math Biol. 2017;79(9):2109–2131. doi: 10.1007/s11538-017-0322-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wu P., Hao X., Lau EHY., Wong JY., Leung KSM., Wu JT., et al. Real-time tentative assessment of the epidemiological characteristics of novel coronavirus infections in Wuhan, China, as at 22 2020. Eurosurveillance. 2020;25(3) doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.3.2000044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tang B., Wang X., Li Q., Bragazzi N.L., Tang S., Xiao Y., Wu J. Estimation of the transmission risk of the 2019-nCoV and its implication for public health interventions. J Clin Med. 2020;9:462. doi: 10.3390/jcm9020462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Iboi EA., Ngonghala CN., Gumel AB. Will an imperfect vaccine curtail the COVID-19 pandemic in the US? Infect Dis Model. 2020;5:510–524. doi: 10.1016/j.idm.2020.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhou F., Yu T., Du R., Fan G., Liu Y., Liu Z., Xiang J., Wang Y., Song B., Gu X., Guan L. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Din A., Li Y., Yusuf A. Delayed hepatitis B epidemic model with stochastic analysis. Chaos Solitons Fractals. 2021;146 [Google Scholar]

- 76.Din A., Li Y. Stationary distribution extinction and optimal control for the stochastic hepatitis b epidemic model with partial immunity. Phys Scr. 2021;96(7) [Google Scholar]

- 77.Din A., Li Y., Shah MA. The complex dynamics of hepatitis b infected individuals with optimal control. J Syst Sci Complex. 2021;34(4):1301–1323. doi: 10.1007/s11424-021-0053-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gao D., Lou Y., He D., Porco TC., Kuang Y., Chowell G., Ruan S. Prevention and control of Zika as a mosquito-borne and sexually transmitted disease: a mathematical modeling analysis. Sci Rep. 2016;6(1) doi: 10.1038/srep28070. 1-0. PMID: 27312324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Center for Disease Control (CDC); 2020. Coronavirus (COVID-19) https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-nCoV/index.html (Accessed 20 December, 2020) [Google Scholar]

- 80.Fan G., Yang Z., Lin Q., Zhao S., Yang L., He D. Decreased case fatality rate of COVID-19 in the second wave: a study in 53 countries or regions. Transb Emerg Dis. 2021;68(2):213–215. doi: 10.1111/tbed.13819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zhao S. A simple approach to estimate the instantaneous case fatality ratio: Using the publicly available COVID-19 surveillance data in Canada as an example. Infect Dis Model. 2020;5:575–579. doi: 10.1016/j.idm.2020.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Musa SS., Qureshi S., Zhao S., Yusuf A., Mustapha UT., He D. Mathematical modeling of COVID-19 epidemic with effect of awareness programs. Infect Dis Model. 2021;6:448–460. doi: 10.1016/j.idm.2021.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ludwig D. Final size distribution for epidemics. Math Biosci. 1975;23(1–2):33–46. [Google Scholar]

- 84.World Health Organization; 2021. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) post COVID-19 condition. https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/coronavirus-disease-(covid-19)-post-covid-19-condition?gclid=Cj0KCQjwjN-SBhCkARIsACsrBz4p-5xCB9QxEGVMVtz8sjp2oS7_doRMClQgBL3erqyhR1dczaWPP1YaAkYAEALw_wcB (Accessed 15 April 2022) [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sabir Z., Botmart T., Raja MA., Sadat R., Ali MR., Alsulami AA., Alghamdi A. Artificial neural network scheme to solve the nonlinear influenza disease model. Biomed Signal Process Control. 2022;75 [Google Scholar]

- 86.Sabir Z., Wahab HA., Nguyen TG., Altamirano GC., Erdoğan F., Ali MR. Intelligent computing technique for solving singular multi-pantograph delay differential equation. Soft Comput. 2022:1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sabir Z., Baleanu D., Ali MR., Sadat R. A novel computing stochastic algorithm to solve the nonlinear singular periodic boundary value problems. Int J Comput Math. 2022:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sabir Z., Ali MR., Sadat R. Gudermannian neural networks using the optimization procedures of genetic algorithm and active set approach for the three-species food chain nonlinear model. J Ambient Intell Humaniz Comput. 2022 doi: 10.1007/s12652-021-03638-3. 1-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Sabir Z., Raja MA., Shoaib M., Sadat R., Ali MR. A novel design of a sixth-order nonlinear modeling for solving engineering phenomena based on neuro intelligence algorithm. Eng Comput. 2022:1–6. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The COVID-19 reported data used in this work were freely obtained from the public domains of the WHO dashboard via https://covid19.who.int/.