Abstract

Introduction

Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in neonates (MIS-N) related to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) has increasingly been reported worldwide amid the spread of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic.

Methods

We searched PubMed, EMBASE, and CINAHL and preprint servers (BioRxiv.org and MedRxiv.org) using a specified strategy integrating Medical Subject Headings terms and keywords until October 20, 2021. Our aim was to systematically review demographic profiles, clinical features, laboratory parameters, complications, treatments, and outcomes of neonates with MIS-N. Studies were selected when fulfilling the inclusion criteria. Articles were included if they fulfilled the World Health Organization (WHO), Centers for Disease Control (CDC) definitions of MIS-C, or our proposed definition.

Results

Sixteen reports of MIS-N including 47 neonates meeting MIS-N criteria were identified. Presentation included cardiovascular compromise (77%), respiratory involvement (55%), and fever in (36%). Eighty-three percent of patients received steroids, and 76% received immunoglobulin. Respiratory support was provided to 60% of patients and inotropes to 45% of patients. Five (11%) neonates died.

Conclusion

The common presentation of MIS-N included cardiorespiratory compromise with the possibility of high mortality. Neonates with MIS-N related to SARS-CoV-2 may be at higher risk of adverse outcomes.

Keywords: Neonate, Multisystem inflammatory, Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2, COVID-19, Multisystem inflammatory syndrome

Introduction

As the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic continues worldwide, increasing cases of severe disease are being reported, including multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) [1]. Similar to macrophage activating syndrome (MAS) and other inflammatory diseases in children, the presentation of MIS-C with SARS-CoV-2 infection is usually severe with a good prognosis [2]. Interestingly, MIS-C is reported more frequently in children of older age [3]. To date, there are more than 6,000 reported cases of MIS-C [1].

Recently, there have been reports of multisystem involvement following SARS-COV-2 infection in neonates; however, the extent of involvement, assessment, and their management has varied. Of note, multisystem inflammatory syndrome in neonates (MIS-N) takes various forms with multiple cardiac presentations and complications, and the reported therapies include various immunological treatments [4, 5, 6]. MIS-N is postulated to develop because of immune-mediated multisystem injury either due to the transplacental transfer of maternal SARS-Co2 antibodies or due to late response to antibodies mounted by the newborn to SARS-CoV-2 infection [4, 5, 7, 8]. The SARS-CoV-2 virus was reported as one of the rare causes of foetal inflammatory response syndrome [4] and may also be associated with MIS-N, similar to a case reported in the paediatric population [9]. As these reports are surfacing, our objective was to conduct a systematic review and summarize the clinical and demographic profiles, management employed, and outcomes following MIS-N after SARS-CoV-2 exposure/infection.

Methods

Research Question

What are the demographic profile, clinical characteristics, management strategies, prognosis, and outcomes of MIS-N associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection?

Protocol and Registration

This systematic review was constructed in accordance with the framework of the PRISMA (see the PRISMA checklist in online suppl. material; see www.karger.com/doi/10.1159/000524202 for all online suppl. material). In addition, the protocol was registered under the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (registration number CRD42021266065).

Data Sources and Searches

We searched MEDLINE, WHO COVID-19 database, LitCovid, Google Scholar, Science Direct, Web of Sciences, and preprints from medRxiv and bioRxiv using the search terms “COVID 19,” “SARS CoV2,” “Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in neonates,” “MIS-N,” “Fetal/Foetal multi-system inflammatory syndrome temporally associated with SARS-CoV-2,” and Project Management Information Systems Overviews − Transformation system “PMIS-TS” for all articles published up to October 20, 2021. Two independent reviewers performed the search using appropriately chosen relevant Medical Subject Headings terms and keywords. A complete list of search terms is provided (online suppl. Table S1). A shadow search of the reference lists was performed manually by independent reviewers to avoid missing key articles and considering the ongoing pandemic. The search was restricted to articles in the English language.

Study Selection Based on Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The identified articles were reviewed critically based on title, date, place, authors, and type of study by two independent reviewers, L.S. and M, and differences were resolved by discussion with K.M. and P.S.S. All the included abstracts were screened and stratified based on their type and design. The following inclusion criteria were considered for quantitative data analysis: (1) case report or case series regardless of the sample size, (2) cohort studies and (3) retrospective observational studies, and (4) research letter or correspondence articles having detailed data on patient characteristics. We excluded narrative reviews, viewpoints, perspectives, correspondence articles lacking patient data, and articles focussing only on pathogenesis. Duplicate reports not providing additional information were excluded. The two reviewers independently analysed the included publications by full-text reading and screening (see online suppl. material). In cases of discrepancy, a unanimous decision was attained through Web-based conference discussions with all authors.

MIS-N Diagnosis

There is a clear definition of MIS-C in children as described by the World Health Organization (WHO) and Centers for Disease Control (CDC). In general, the MIS-C definition includes fever with multi-organ involvement (2 or more organs) and evidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection. The major difference between the CDC and WHO definitions is the duration of fever. Currently, there is no agreed definition of MIS-N for which we adapted criteria for diagnosis in this special group. We categorized neonates as having confirmed MIS-N when they fulfilled either the CDC or WHO criteria for MIS-C and had a confirmed infection or exposure to SARS-CoV-2 infection before 28 days of age after excluding other causes (Table 1) [12, 13]. The fulfilment of one of the criteria was sufficient to confirm the diagnosis of MIS-N. Neonates with confirmed infection or exposure to SARS-CoV-2 infection before 28 days of age and who presented without fever and had three-organ involvement were categorized as suspected MIS-N after excluding other possible causes, such as sepsis, birth asphyxia, and others.

Table 1.

| CDC case definition [10] | WHO case definition [11] | |

|---|---|---|

| All 4 criteria must be met | All 6 criteria must be met | |

|

| ||

| 1. Age <21 years | 1. Age 0–19 years | |

|

| ||

| 2. Clinical presentation consistent with MIS-C, including all of the following | a − Fever: documented fever >38.0°C (100.4°F) for ≥24 h or report of subjective fever lasting ≥24 h | 2. Fever for ≥3 days |

| b − Multisystem involvement: 2 or more organ systems involved Cardiovascular (e.g., shock, elevated troponin, elevated BNP, abnormal echocardiogram, arrhythmia) Respiratory (e.g., pneumonia, ARDS, pulmonary embolism) Renal (e.g., AKI, kidney failure) Neurologic (e.g., seizure, stroke, aseptic meningitis) Haematologic (e.g., coagulopathy) Gastrointestinal (e.g., abdominal pain, vomiting, diarrhoea, elevated liver enzymes, ileus, gastrointestinal bleeding) Dermatologic (e.g., erythroderma, mucositis, other rash) |

3. Clinical signs of multisystem involvement (at least 2 of the following) Rash, bilateral non-purulent conjunctivitis, or mucocutaneous inflammation signs (oral, hands, or feet) Hypotension or shock Cardiac dysfunction, pericarditis, valvulitis, or coronary abnormalities (including echocardiographic findings or elevated troponin/BNP) Evidence of coagulopathy (prolonged PT or PTT; elevated D-dimer) Acute gastrointestinal symptoms (diarrhoea, vomiting, or abdominal pain) |

|

| c − Laboratory evidence of inflammation including, but not limited to, any of the following Elevated CRP Elevated ESR Elevated fibrinogen Elevated PCT Elevated D-dimer Elevated ferritin Elevated LDH Elevated IL-6 level Neutrophilia Lymphocytopaenia Hypoalbuminemia |

4. Elevated markers of inflammation (e.g., ESR, CRP, or PCT) | |

| d − Severe illness requiring hospitalization | – | |

|

| ||

| 3. No alternative plausible diagnoses | 5. No other obvious microbial cause of inflammation, including bacterial sepsis and staphylococcal/streptococcal toxic shock syndromes | |

|

| ||

| 4. Recent or current SARS-CoV-2 infection or exposure | 6. Evidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection | |

| Any of the following | Any of the following | |

| Positive SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR | Positive SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR | |

| Positive serology | Positive serology | |

| Positive antigen test | Positive antigen test | |

| COVID-19 exposure within the 4 weeks prior to the onset of symptoms | Contact with an individual with COVID-19 | |

HAN, Health Alert Network; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase.

We further categorized neonates into early and late presentation as follows:

1. Early MIS-N − hypothesized as presenting due to the transplacental transfer of maternal SARS-CoV-2 antibodies when a neonate is born to a mother who is SARS-CoV-2 positive, and the neonate is demonstrating clinical/laboratory features within 72 h after birth.

2. Late MIS-N − hypothesized as occurring due to antibodies produced secondarily to SARS-CoV-2 infection in the newborn when the neonate presents with clinical and laboratory features beyond the first 72 h of age [14].

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

Data extraction was performed by two reviewers, independently, from the studies included. The extracted data were segregated into demographic parameters, which included the number of cases in each study, sex, and age; clinical parameters comprising gastrointestinal symptoms, neurological symptoms, pericardial disease, myocarditis, and left ventricular dysfunction. Also included are laboratory investigations comprising the requirement of vasopressor support or invasive ventilatory support and the incidence of coronary artery abnormalities and mortality. We also included management strategies, which included the use of intravenous immunoglobulin, corticosteroids, and the need for second-line immunomodulators and COVID-19 status on RT-PCR testing as well as serological evidence (IgG, IgM, and IgA).

Risk of Bias

Two reviewers assessed the risk of bias of each study by using the National Institute of Health quality assessment tool or the Joana Briggs Institute's tool [15] for case series and observational cohort studies. Each study was evaluated for risk of bias in methodology, including patient selection, attrition, detection, confounding factors, and causality association. A third independent reviewer, K.M., sorted any discrepancies via group discussion between reviewers, which was further confirmed by an independent reviewer, P.S.S. The studies were assigned low risk of bias or high risk of bias. The studies with low risk of bias were then assigned “included,” and the studies with high risk of bias were then assigned “excluded” status based on the responses.

Data Synthesis and Statistics

The extracted data were tabulated in a predefined manner. Data were summarized from all included studies in a table format to provide the complete context of the available evidence. No statistical analysis was planned as we expected case reports or case series based on the low prevalence of the condition.

Results

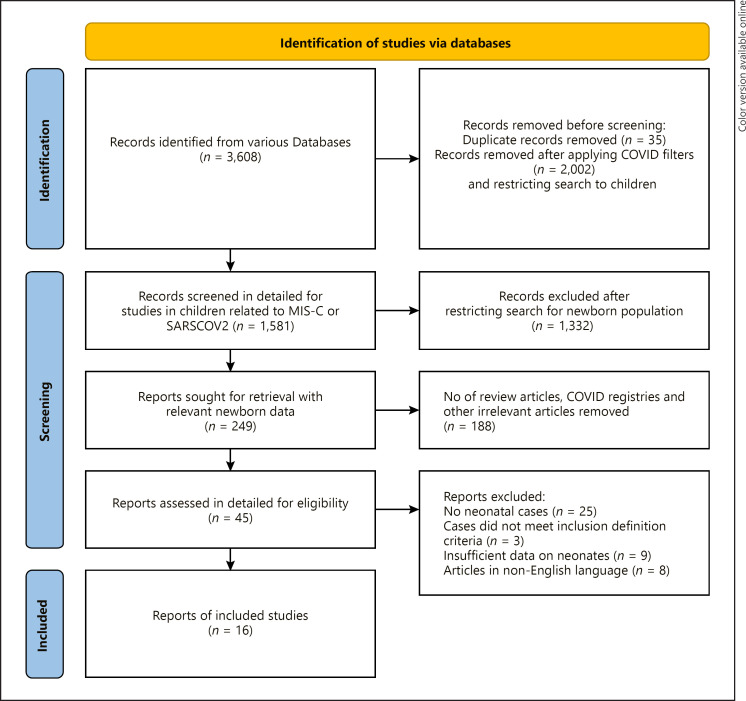

A total of 3,608 studies were retrieved from various databases with a broad search for “COVID 19,” “SARS CoV2,” and “Multisystem inflammatory syndrome”; however, only 1,581 were screened in detail after applying COVID-19 filters, removing duplicates and restricting the search to the child population. The details of the search terms and the results of the search strategies are contained in online supplementary Table 1. The PRISMA flow diagram for study selection is depicted in Figure 1. A total of 16 studies reporting on 47 neonates were included in the systematic review. The risk of bias among the included studies revealed that most reports met the Joanna Briggs Institute criteria for the reporting of key characteristics; however, we could not exclude the possibility of publication bias (Table 2). The majority of all included studies' answers were reported as “yes,” as shown in Table 2. These studies were from India (7), the USA (2), Saudi Arabia (2), Qatar (1), Israel (1), Iran (1), Netherland (1), and Brazil (1). Fourteen studies were case reports, and two were case series. According to the CDC and WHO criteria for the diagnosis of MIS-C, 15 neonates had confirmed MIS-N, and 32 neonates had suspected MIS-N (Table 3) [6].

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram for study selection.

Table 2.

Assessment of quality of studies [4, 5, 14, 16–28]

| Author [ref] | Were patient's demographic characteristics clearly described? | Was the patient's history clearly described and presented as a timeline? | Was the current clinical condition of the patient on presentation clearly described? | Were diagnostic tests or assessment methods and the results clearly described? | Were the interventions or treatment procedure clearly described? | Was the post-intervention clinical condition clearly described? | Were adverse events (harms) or unanticipated events identified and described? | Does the case report provide takeaway lessons? | Risk of bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| More et al. [14] | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Low |

| Pawar et al. [16] | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Low |

| Shaiba et al. [17] | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Low |

| Borkotoky et al. [5] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Low |

| Diggikar et al. [18] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Low |

| Divekar et al. [19] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Low |

| Diwakar et al. [20] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Low |

| Eghbalian et al. [21] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Low |

| Kappanavil et al. [22] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Low |

| Lima et al. [23] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Low |

| Magboul et al. [24] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Low |

| McCarty et al. [4] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Low |

| Orlanski-Meyer et al. [25] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Low |

| Saha et al. [26] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Low |

| Schoen-makers et al. [27] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Low |

| Shaiba et al. [28] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Low |

Table 3.

Demographic, clinical presentation, length of the hospital stay, and outcome of neonates with MIS-N [4, 5, 14, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28]

| Author/[ref] country/N | Type of study | Sex | Age presented | Mode of birth | Gestational age | Clinical manifestation | ICU length of stay | Outcome | Diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| More et al. [14] (India) N = 12 | Case series | F:M = 8:4 | 1–7 days: 6/12 7–28 days: 6/12 | V/CS: 5/7 | Term = 9 Late preterm (32–37 wk) = 3 | Fever 6/12, respiratory-6/12, CVS 6/20, GI manifestations-8/12, haematological 3/12, neurological 1/12 | 5 days to 11 week | Death-2 Survived-10 | Confirmed MIS-N in 7 Suspected MIS-N in 5 |

|

| |||||||||

| Pawar et al. [16] (India) N = 20 | Case series | F:M = 10:10 | 1–5 days | V/CS: 13/7 | Term = 3, late preterm (34–37 wk) = 13, less than 33 wk = 4 | Fever 2/20, respiratory 11/20, CVS 18/20, GIT 6/20, renal 1/20, haematological 2/20, neurological 2/20, cutaneous 1/20 | 7–36 days | Death-2 Survived-18 | Confirmed MIS-N in 2 (duration of fever is not mentioned, appearance on day 1 of life) Suspected MIS-N in 18 |

|

| |||||||||

| Shaiba et al. [17] (KSA) N = 1 | Case series | F | 30 days | NA | NA | Fever, respiratory, CVS, GIT, renal, haematological | 15 days | Death | Confirmed MIS-N |

|

| |||||||||

| Borkotoky et al. [5] (India) N = 1 | Case report | M | 4 h | CS | 38 3/7 | Fever, respiratory, CVS, GIT, haematological, cutaneous | 34 days | Survived | Confirmed MIS-N |

|

| |||||||||

| Diggikar et al. [18] (India) N = 1 | Case report | NA | 7 days | NA | Term | Fever, CVS, neurological | NA | Survived | Confirmed MIS-N |

|

| |||||||||

| Divekar et al. [19] (USA) N = 1 | Case report | F | 1 day | CS | 30 wk | Respiratory, CVS, liver, renal, haematological | 2 months (mostly due to premature) | Survived | Suspected MIS-N |

|

| |||||||||

| Diwakar et al. [20] (India) N = 1 | Case report | M | 19 days | CS | 39 wk | Fever, GIT, haematological, cutaneous | 6 days | Survived | Confirmed MIS-N |

|

| |||||||||

| Eghbalian et al. [21] (Iran) N = 1 | Case report | M | 9 days | CS | 39 wk | Fever, respiratory, GIT: Yes, haematological | 4 days | Survived | Suspected MIS-N (did not specify the duration of fever) |

|

| |||||||||

| Kappanavil et al. [22] (India) N = 1 | Case report | F | 24 days | V | Term | Respiratory, CVS Liver, renal, cutaneous | 20 days | Survived | Suspected MIS-N |

|

| |||||||||

| Lima et al. [23] (Brazil) N = 1 | Case report | F | 1 day | CS | 33 wk | Respiratory, CVS, liver | 22 days | Survived | Suspected MIS-N |

|

| |||||||||

| Magboul et al. [24] (Qatar) N = 1 | Case report | F | 14 days | V | 36+6 wk | Fever, liver, haematological | 14 days | Survived | Suspected MIS-N (duration fever 11 h) |

|

| |||||||||

| McCarty et al. [4] USA N = 1 | Case report | M | 1 day | V | 34+6 wk | Fever, respiratory CVS, haematological | 22 days | Survived | Suspected MIS-N (the neonate became febrile at 12 h of age, and duration is not mentioned) |

|

| |||||||||

| Orlanski-Meyer et al. [25] (Israel) N = 1 | Case report | F | 8 wk | NA | NA | Fever, CVS, GIT, liver, haematological | NA | Survived | Confirmed MIS-N |

|

| |||||||||

| Saha et al. [26] (India) N = 1 | Case report | F | 25 days | NA | Term | Fever, respiratory CVS, GIT, liver, renal, haematological, neurological, cutaneous | 25 days | Survived | Confirmed MIS-N |

|

| |||||||||

| Schoenmakers et al. [27] (Netherlands) N = 1 | Case report | F | 1 day | CS | 31+4 wk GA | Respiratory, CVS, liver, renal, haematological | NA | Survived | Suspected MIS-N (absence of fever) |

|

| |||||||||

| Shaiba et al. [28] (Saudi Arabia) N = 2 | Case report | F | 1 day | V/CS: 1/1 | 36 wk, 32 wk | Respiratory yes in both, CVS yes both Liver yes in 1 case, haematological yes in both | Case 1: 12 days Case 2: 30 days | Both survived | Suspected MIS-N (both) |

F, female; M, male; V, vaginal delivery; CS, caesarean section; CVS, cardiovascular system; GIT, gastrointestinal system; ICU, intensive care unit.

Clinical manifestation, laboratory evidence of inflammation, radiological investigation, and the associated diagnoses of 47 neonates are shown in Tables 3 and 4. At the time of MIS-N diagnosis, 34 neonates were ≤7 days of age, and 13 were >7 days of age. Early neonatal MIS was identified in 28 neonates, while late MIS-N was identified in 19 neonates. Twenty-two neonates were born via vaginal route, 21 were born via caesarean section, and the mode of birth data were unavailable for 4 patients. Eighteen patients were delivered at full term, 27 were preterm, and data on gestation at birth were not available for 2 patients. Two neonates were reported to have a concomitant bacterial infection.

Table 4.

Serologies of mothers and their neonates presenting with MIS-N and laboratory/radiological investigation [4, 5, 14, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28]

| Author [ref] | Maternal SARS-CoV-2 NPA RT-PCR | Maternal SARS-CoV-2 serology | Neonatal SARS-CoV-2 NPA RT-PCR | Neonatal SARS-CoV-2 serology | Laboratory evidence of inflammation | Radiological investigation | Echocardiogram | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| More et al. [14] | Positive in 5/12 History of COVID-19 positive in 9/12 | IgG-positive in all | Negative in all | IgG-positive in all | ↑CRP: 4/12 | CXR: pneumonia like change 2/12, RDS 4/12 | Cardiac dysfunction 6/12 Dilated coronaries 1/12 | |

| ↑PCT: 3/12 | ||||||||

| ↑D-dimer: 7/12 | ||||||||

| ↑Ferritin: 5/12 | ||||||||

| ↑LDH: 4/12 | ||||||||

| ↑NT-proBNP: 7/12 | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Pawar et al. [16] | NA | 4 IgG positive 3 IgG below cut-off limit | NA | IgG positive: 17 | ↑CRP: high 15/20 | CXR: cardiomegaly 1/20 | Arrhythmia − 11 Dilated coronaries − 2 intracardiac thrombus − 2 shock/cardiac dysfunction − 5 | |

| IgG below cut-off limit: 2 | ↑PCT: 4/20 | |||||||

| IgG negative: 1 | ↑D-dimer: 19/20 | |||||||

| ↑Ferritin: 4/20 | ||||||||

| ↑LDH: 8/20 | ||||||||

| ↑NT-proBNP: high 9/20 | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Shaiba et al. [17] | NA | NA | Positive | NA | ↑CRP | CXR: bilateral opacities/pulmonary oedema/atelectasis | Small pericardial effusion, EF 80.5% | |

| ↑PCT | ||||||||

| ↑D-dimer | ||||||||

| ↑Ferritin | ||||||||

| ↑LDH | ||||||||

| ↑NT-proBNP | ||||||||

| ↑Troponin | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Borkotoky et al. [5] | Negative | IgG positive | Negative | IgG positive | ↑CRP | Chest CT: diffuse bilateral ground-glass opacities | Severe PHT | |

| IgM negative | IgM negative | ↑PCT | ||||||

| ↑D-dimer | ||||||||

| ↑Ferritin | ||||||||

| ↑LDH | ||||||||

| ↑NT-proBNP | ||||||||

| ↑Troponin | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Diggikar et al. [18] | Positive | NA | Positive | Negative | ↑CRP | CXR: normal | a small coronary artery aneurysm and good biventricular function | |

| ↑D-dimer | ||||||||

| ↑Ferritin | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Divekar et al. [19] | Positive | NA | Negative | NA | ↑D-dimer | CXR: cardiomegaly/ | Small pericardial effusion | |

| ↑NT-proBNP | pulmonary oedema | |||||||

| ↑Troponin | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Diwakara et al. [20] | Positive | NA | Negative | NA | ↑CRP | CXR | Normal | |

| ↑D-dimer | NA | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Eghbalian et al. [21] | Negative | NA | Positive | NA | ↑CRP | CT chest: bilateral | NA | |

| ↑ESR | peripheral ground-glass infiltration and opacity | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Kappanavil et al. [22] | Positive | Positive IgG | Negative | Positive IgG | ↑CRP | CXR: cardiomegaly | Severe biventricular dysfunction LVEF of 10% and global hypokinesia. Coronary arteries appeared prominent and hyperechoic | |

| ↑D-dimer | ||||||||

| ↑Ferritin | ||||||||

| ↑LDH | ||||||||

| ↑NT-proBNP | ||||||||

| ↑Troponin | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Lima et al. [23] | Swab: NA | Positive | Positive | IgG positive | ↑D-dimer | CXR: normal | Pericardial effusion | |

| IgM negative | ↑Ferritin | Chest CT: ground-glass opacities | ||||||

| ↑LDH | ||||||||

| ↑Troponin | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Magboul et al. [24] | Negative | NA | Positive | NA | ↑CRP | CXR: bilateral opacities | Normal | |

| ↑ESR | ||||||||

| ↑PCT | ||||||||

| ↑D-dimer | ||||||||

| ↑Ferritin | ||||||||

| ↑NT-proBNP | ||||||||

| ↑Troponin | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| McCarty et al. [4] | Positive | NA | Negative | NA | ↑CRP: high | CXR: bilateral granular opacities | Severe PHT | |

|

| ||||||||

| Orlanski-Meyer et al. [25] | NA | NA | NA | Positive | ↑CRP | CXR | Mild-moderate mitral régurgitation | |

| ↑ESR | NA | |||||||

| ↑D-dimer | ||||||||

| ↑Ferritin | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Saha et al. [26] | NA | NA | Positive | NA | ↑CRP: high | CXR: pulmonary oedema/cardiomegaly | Systolic dysfunction (EF ˜ 40%)/mild pericardial effusion | |

| ↑D-dimer | ||||||||

| ↑Ferritin | Chest CT: atelectasis of both lower lobes of lung | |||||||

| ↑NT-proBNP | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Schoenmakers et al. [27] | Positive | Positive | Negative | Negative | ↑D-dimer | CXR: bilateral opacities | PPHN/significantly enlarged LMCA | |

| ↑Ferritin | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Shaiba et al. [28] | Positive for both mothers | NA | Case 1: negative | Case 1 positive | ↑CRP: 1/2 | CXR | Case 1: moderately dilated LV with poor systolic function myocarditis/PDA with a bidirectional shunt Case 2: normal | |

| Case 2: positive | Case 2 negative | ↑ESR: 1/2 | Case 1: normal | |||||

| ↑PCT: 1/2 | Case 2: bilateral ground- | |||||||

| ↑D-dimer: 1/2 | glass appearance | |||||||

| ↑Ferritin: 2/2 | ||||||||

| ↑LDH: 2/2 | ||||||||

| ↑NT-proBNP: 2/2 | ||||||||

| ↑Troponin: 2/2 | ||||||||

PPHN, pulmonary hypertension of the newborn; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; PHT, pulmonary hypertension; LMCA, left main coronary artery; LV, left ventricle.

The clinical presentation of included neonates is summarized in Table 5. The most common presenting features were cardiovascular manifestations (77%). This included cardiac dysfunction in 14 neonates, arrhythmia in 11 neonates, dilated coronaries/aneurysm in five neonates, pericardial effusion in four neonates, and persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn in three as well as intracardiac thrombus in two neonates. Fever was present in 17 patients (36%).

Table 5.

Summary of clinical presentation

| Clinical manifestations | Numbers (N = 47), N (%) |

|---|---|

| Cardiovascular | 36 (76.6) |

| Shock/cardiac dysfunction | 14/36 |

| Arrhythmia | 11/36 |

| Dilated coronaries/aneurysm | 6/36 |

| Tachycardia | 4/36 |

| PPHN | 4/36 |

| Pericardial effusion | 3/36 |

| Intracardiac thrombus | 2/36 |

| Mitral regurgitation | 1/36 |

| Respiratory | 27 (55.3) |

| Respiratory distress | 27/27 |

| Pulmonary oedema | 3/27 |

| Respiratory failure | 1/27 |

| Gastrointestinal | 20 (42.6) |

| Feeding intolerance | 13/20 |

| Loose stool/diarrhoea | 4/20 |

| Vomiting | 2/20 |

| Enterocolitis | 2/20 |

| GI bleeding | 2/20 |

| Fever | 17 (36.2) |

| Haematological | 17 (36.2) |

| Thrombocytopaenia | 14/17 |

| Leukopenia | 6/17 |

| Anaemia | 5/17 |

| Neutropenia | 5/17 |

| Lymphopenia | 2/17 |

| Hepatic | 8 (17.0) |

| Liver dysfunction | 5/8 |

| Hepatomegaly | 3/8 |

| Renal | 6 (12.8) |

| Acute kidney injury | 6/6 |

| Cutaneous | 5 (10.6) |

| Rash | 5/5 |

| Neurological | 5 (10.6) |

| Seizure | 5/5 |

| Decreased reflexes | 1/5 |

PPHN, pulmonary hypertension of the newborn.

Laboratory testing (Table 4) revealed that troponin was high in all neonates who were tested (8/8 neonates), 38/45 (84%) had elevated D-dimer, 4/6 neonates (67%) had an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, 30/46 had elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) (65%), 5/8 (63%) had anaemia, 24/40 (60%) had high NT-beta-natriuretic peptide, 20/42 (48%) had high ferritin, 18/38 (47%) had high lactate dehydrogenase, 6/20 (30%) had lymphopenia, 11/38 (29%) had high procalcitonin (PCT), 13/46 (28%) had thrombocytopaenia, and 9/43 (21%) had neutrophilia.

Eighteen neonates had a chest X-ray reported, of which 11 had opacities, four had cardiomegaly, three had pulmonary oedema, and three were normal (some had multiple abnormalities). A computed tomography scan of the chest was conducted in 4 cases and identified ground-glass opacities in 3 patients and atelectasis in 1 patient. Forty-six patients had echocardiograms (Table 4).

Maternal SARS-CoV-2 swab was positive for 13/23 (37%) mothers, and serology was positive in 20/23 (87%) mothers. Among neonates, 7/26 (27%) had a positive RT-PCR test for SARS-CoV-2, 19/26 had a negative RT-PCR (21 had no RT-PCR done), and 34/40 (85%) neonates had positive serology; 32 neonates had positive IgG and two had nonspecific positive serology; 7 neonates had no serology reported (Table 4).

Most neonates received immunoglobulins as part of treatment for suspected/confirmed MIS-N (36/47, 77%). The dose of immunoglobulin ranged between 1g/kg/dose for one or two doses or 1–2g/kg/dose once. Specific treatments targeted for anti-inflammatory/anti-infective agents and supportive managements are reported in Table 6. Most neonates received steroids (83%) as part of the management of MIS-N. Anakinra was only given in 4 patients. Respiratory support was needed in 60% of patients. Many neonates required inotropic support (45%), and 40% of neonates received heparin. A total of 42 infants (89%) survived till discharge, and five neonates died (5/47, 11%). Two neonates died due to multi-organ dysfunction, two neonates died due to shock with left ventricular dysfunction, and one neonate died due to necrotizing enterocolitis. The length of hospital stay ranged between 6 days to 11 weeks; however, many stayed in the hospital for their underlying reasons for admission, which mainly was preterm birth (Table 3).

Table 6.

Summary of management of neonates with MIS-N

| Management | N = 47, N (%) |

|---|---|

| Anti-inflammatory/anti-infective agents | |

| Steroid | 39 (82.9) |

| Immunoglobulin | 36 (76.6) |

| Antibiotics | 25 (53.2) |

| Anakinra | 4 (8.5) |

| Antiviral (remdesivir) | 1 (2.1) |

| Supportive therapies | |

| Respiratory support | 28 (59.6) |

| Inotrope | 21 (44.7) |

| Heparin | 19 (40.4) |

| iNO | 3 (6.4) |

| Antihypertensive | 2 (4.3) |

| Aspirin | 2 (4.3) |

iNO, inhaled nitric oxide.

Discussion

MIS-N is emerging as a new disease in the newborn population, similar to MIS-C in children, and this is the first systematic review summarizing the available literature on the clinical course and outcome of MIS-N. The perinatal vertical transmission of SARS-CoV-2 is fortunately infrequent, with a reported incidence varying from 1 to 10% in different registries [29, 30]. However, newborns may still present soon after birth due to immune-mediated systemic effect secondary to the transplacental transfer of maternal antibodies along with other chemical mediators, leading to MIS-N [10, 11, 31]. Some newborns acquiring the SARS-CoV-2 infection during the perinatal or postnatal period may remain asymptomatic for the infection yet can produce antibodies against SARS-CoV-2, which may manifest as MIS-N, similar to the process of MIS-C in children [8]. The latent period for antibody production may range from 2 to 4 weeks, and thus, it may be difficult to predict the onset of MIS-N. Understanding the immune mechanisms of MIS-N is critical for advising on management strategies and potential preventive measures [7, 8]. MIS-N is a multifactorial disease with an unknown pathophysiology. Three mechanisms have been postulated, as mentioned above: either secondary to in utero exposure to maternal antibodies or via transplacental infection acquired from maternal infection and the endogenous production of antibodies in the foetus/child or via a postinfectious immune response to SARS-CoV-2 infection in a neonate. These antibodies can initiate a cascade of inflammatory response and result in multi-organ involvement [8]. Most of the neonates (60%) included in this systematic review were categorized as early MIS-N, signifying possible in utero exposure to maternal antibodies or via transplacental acquired immune response. The remainder of the neonates (40%) presented as late MIS-N and are possibly postinfectious immune response to SARS-CoV-2 infection in a neonate.

In this review, we summarized data from 16 studies reporting on 47 newborns, and most of these studies were from India. Of note, none of the included neonates had a pre-existing comorbidity other than preterm birth, which was present in more than half of the included cases. Interestingly, although fever is a major criterion for diagnosing MIS-C, it was only present in approximately one-third of the neonates. Most neonates had cardiovascular involvement, and most received steroids and immunoglobulin for management. The presence of cardiovascular manifestations in MIS-N is similar to features seen in typical Kawasaki disease or systemic haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis/MAS. Both these conditions occur as a result of delayed hyperimmune response, and it is thought that a similar situation occurs with exposure to SARS-CoV-2 infection. The majority of patients included in this review exhibited changes in inflammatory markers, such as elevated CRP, ferritin, and PCT, as well as lymphopenia, similar to children reported as having MIS-C [19, 20]. However, there were differences in the presentation features of MIS-N. The differences in MIS-C and MIS-N could be due to the differential activation of the immune system as it is developmentally immature in neonates. A systematic review on MIS-C reported that most children presented with fever [2] (compared to 36% of the neonates had fever in our review) or gastrointestinal symptoms (70%) [32] (compared to 40% in neonates). However, cardiovascular manifestations were comparable (60–70% in MIS-C and 77% in MIS-N) [2, 32].

MIS-N seems to be more severe in presentation compared to MIS-C as the 11% mortality rate in our review far exceeds the 1.9% reported in MIS-C [3]. The mortality was high in neonates presenting with MIS-N and is reported at 11% among the cases included in this report, which is concerning for clinicians. A recent multicentre study from Latin America has reported high mortality in children with MIS, where the mortality rate was 2.1% of the whole cohort [33]. Of interest, in the same study, two out of 36 neonates died for reason other than MIS [33]. Since it is not clearly reported to be the cause of death, it is difficult for us to tease out the reasons as it could be secondary to issues related to preterm birth. Three of the babies who died in our review were born at preterm gestation, one each at 27, 32, and 36 weeks' gestation, and one was at full-term gestation. One of the neonates who died had no gestational age reported. Moreover, our review included only 47 neonates, whereas MIS-C is reported in over 6,000 cases [1]. There might be under-recognition of MIS-N, leading to less reported cases, and, thus, publication bias could not be ruled out.

The management employed by various clinicians when faced with suspected or confirmed MIS-N varied, especially due to this being uncharted territory for neonatologists. Many clinicians adopted treatments employed in children or adults, which also was in a phase of evolution during this pandemic. The most employed modes were to provide some form of anti-inflammatory/anti-infective therapies and supportive management, including respiratory support, cardiovascular support, and the prevention of thrombosis. Intravenous immunoglobulin and corticosteroids were the mainstays; however, the mechanism of action for these therapies in MIS-C is unknown [34]. Most of the included neonates recovered with evidence of reduced inflammatory markers and cardiovascular recovery within 48–72 h of the initiation of therapy. It will be difficult to determine whether this was secondary to therapies or the natural course of illness. Sixty per cent of neonates received some form of respiratory support compared to 24%, 33%, and 6% of children having received non-invasive ventilation, mechanical ventilation, and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, respectively, in MIS-C [3]. Although more neonates presented with cardiac compromise, only 45% of them required inotropic support, and 6.4% required inhaled nitric oxide compared to 77% of children requiring inotropic support in MIS-C [32].

Currently, there is no evidence that maternal vaccination can be protective against developing MIS-N, as seen in protecting children against MIS-C [35], and it is not demonstrated that these transmitted vaccine-related antibodies can lead to the development of MIS-N. However, the presence of these transmitted antibodies and its effect on neonates in the evolution of MIS-N is unknown. Thus, in such situations, the typing of antibodies to differentiate anti-spike versus anti-nucleoprotein antibodies may be helpful to differentiate the two.

Our systematic review has strengths. We conducted a comprehensive search, meticulously collected data from the included studies, and assessed the studies for risk of bias. However, we must acknowledge its limitations. Most reports are case reports and thus the possibility of publication bias cannot be ruled out. Moreover, the reported laboratory investigations and management principles are not evidence informed and may reflect local/clinicians' practices and may or may not help in the development of clinical practice guidelines. One of the limitations of the review is that there is no consistent report of SARS-CoV-2 serologies in the included neonates and their mothers. Considering the scope of the review as well as the type of studies included in the review, we can only recommend physicians have a low threshold of suspicion of MIS-N managing neonates presenting with SARS-CoV-2 infection. However, strong research implications can be generated with regard to the development of a registry for such cases and the standardization of investigations needed to confirm diagnosis as well as the management and possibility of evaluating various modalities in proper experimental settings.

MIS-N may manifest with varied presentations and varying severity in neonates. The diagnosis of MIS-N can be challenging and requires a high index of suspicion whenever encountering an unusual presentation of an infant exposed in utero or postnatally to SARS-CoV-2. It is advisable that attending teams perform specific investigations to evaluate the inflammatory state and perform a cardiac evaluation as well as provide supportive measures as appropriate. Neonatologists should perform specific investigations when managing neonates presenting with SARS-CoV-2 infection including but not limited to; SARS-CoV-2 antigens and antibodies, CRP, PCT, ferritin, interleukin-6 levels, and D-dimers, especially when the neonate is presenting with at least two systems involvement after excluding other causes. Also, in newborns with suspected or confirmed MIS-N, the measurement of proBNP, lactate dehydrogenase, and troponin should be considered, and early ECHO screening should be performed to assess for myocardial dysfunction. Vigilance is warranted in a situation where MIS-N is suspected as, according to these estimates, the mortality rate is of concern. Further larger observational studies are needed to characterize this evolving condition to guide clinicians in its management.

Statement of Ethics

An ethics statement is not applicable because this study is based exclusively on published literature.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Sources

No funding was secured for this study.

Author Contributions

Lana A. Shaiba, Kiran More, and Prakesh Shah conceptualized and designed the study, coordinated and supervised data collection, drafted the initial manuscript, and reviewed and revised the final manuscript. Adnan Hadid and Rana Almaghrabi were involved in design of the study; contributed, coordinated, and supervised data collection; formatted Tables; and reviewed/approved initial and final manuscript. Muneera Almarry and Mahdi Alnamnakani were involved in design of the study; they contributed and coordinated data collection and carried out the initial analyses and critically reviewed the manuscript and approved final manuscript. All the authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Data Availability Statement

The research data obtained from the included articles are available and can be requested from the corresponding author and will be made available when requested.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Abdul Kareem Pullattayil for his contribution to this study by helping with the development of the research strategy. The authors would like to acknowledge King Saud University and King Saud University medical city for providing the support to the authors along the journey of the production of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [Internet]. CDC COVID data tracker. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [cited 2022 Feb 26]. Available from: https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#mis-national-surveillance.

- 2.Kaushik A, Gupta S, Sood M, Sharma S, Verma S. A systematic review of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children associated with SARS-COV-2 infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2020;39((11)):e340. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000002888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yasuhara J, Watanabe K, Takagi H, Sumitomo N, Kuno T. COVID-19 and multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2021;56((5)):837–48. doi: 10.1002/ppul.25245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McCarty KL, Tucker M, Lee G, Pandey V. Fetal inflammatory response syndrome associated with maternal SARS-COV-2 infection. Pediatrics. 2020;147((4)):e2020010132. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-010132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khaund Borkotoky R, Banerjee Barua P, Paul SP, Heaton PA. COVID-19-related potential multisystem inflammatory syndrome in childhood in a neonate presenting as persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2021;40((4)):e162–4. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000003054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lakshminrusimha S, Hudak ML, Dimitriades VR, Higgins RD. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in neonates following maternal SARS-COV-2 COVID-19 infection. Am J Perinatol. 2021 doi: 10.1055/a-1682-3075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buonsenso D, Riitano F, Valentini P. Pediatric inflammatory multisystem syndrome temporally related with SARS-COV-2: immunological similarities with acute rheumatic fever and toxic shock syndrome. Front Pediatr. 2020;8:574. doi: 10.3389/fped.2020.00574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gee S, Chandiramani M, Seow J, Pollock E, Modestini C, Das A, et al. The legacy of maternal SARS-COV-2 infection on the immunology of the Neonate. Nat Immunol. 2021;22((12)):1490–502. doi: 10.1038/s41590-021-01049-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaushik S, Aydin SI, Derespina KR, Bansal PB, Kowalsky S, Trachtman R, et al. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection (MIS-C): a multi-institutional study from New York City. J Pediatr. 2020;224:24–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.06.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang AT, Garcia-Carreras B, Hitchings MD, Yang B, Katzelnick LC, Rattigan SM, et al. A systematic review of antibody mediated immunity to coronaviruses: kinetics, correlates of protection, and association with severity. Nat Commun. 2020;11((1)):4704. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-18450-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Facchetti F, Bugatti M, Drera E, Tripodo C, Sartori E, Cancila V, et al. Sars-cov2 vertical transmission with adverse effects on the newborn revealed through integrated immunohistochemical, electron microscopy and molecular analyses of placenta. EBioMedicine. 2020;59:102951. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2020.102951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children and adolescents with COVID-19 [Internet]. World Health Organization. World Health Organization. [cited 2021 Nov 22]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications-detail/multisystem-inflammatory-syndrome-in-children-and-adolescents-with-covid-19.

- 13.Han archive: 00432 [Internet]. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2020. [cited 2021 Nov 22]. Available from: https://emergency.cdc.gov/han/2020/han00432.asp.

- 14.More K, Aiyer S, Goti A, Parikh M, Sheikh S, Patel G, et al. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in neonates (MIS-N) associated with SARS-CoV2 infection: a case series [published online ahead of print, 2022 Jan 14] Eur J Pediatr. 2022:1–16. doi: 10.1007/s00431-022-04377-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.For use in JBI systematic reviews checklist for case reports [Internet] [cited 2021 Nov 22]. Available from: https://jbi.global/sites/default/files/2019-05/JBI_Critical_Appraisal-Checklist_for_Case_Reports2017_0.pdf.

- 16.Pawar R, Gavade V, Patil N, Mali V, Girwalkar A, Tarkasband V, et al. Neonatal multisystem inflammatory syndrome (MIS-N) associated with prenatal maternal SARS-COV-2: a case series. Children. 2021;8((7)):572. doi: 10.3390/children8070572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shaiba LA, Altirkawi K, Hadid A, Alsubaie S, Alharbi O, Alkhalaf H, et al. COVID-19 disease in infants less than 90 days: case series. Front Pediatr. 2021;9:674899. doi: 10.3389/fped.2021.674899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Diggikar S, Nanjegowda R, Kumar A, Kumar V, Kulkarni S, Venkatagiri P. Neonatal Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome secondary to SARS-COV-2 infection. J Paediatr Child Health. 2021 doi: 10.1111/jpc.15696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Divekar AA, Patamasucon P, Benjamin JS. Presumptive neonatal multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children associated with coronavirus disease 2019. Am J Perinatol. 2021;38((6)):632–6. doi: 10.1055/s-0041-1726318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Diwakar K, Gupta BK, Uddin MW, Sharma A, Jhajra S. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome with persistent neutropenia in neonate exposed to SARS-COV-2 virus: a case report and review of literature. J Neonatal Perinatal Med. 2021 doi: 10.3233/NPM-210839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eghbalian F, Sami G, Bashirian S, Jenabi E. A neonate infected with coronavirus disease 2019 with severe symptoms suggestive of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in childhood. Clin Exp Pediatr. 2021;64((11)):596–8. doi: 10.3345/cep.2021.00549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kappanayil M, Balan S, Alawani S, Mohanty S, Leeladharan SP, Gangadharan S, et al. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in a neonate, temporally associated with prenatal exposure to SARS-COV-2: a case report. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2021;5((4)):304–8. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(21)00055-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lima AR, Cardoso CC, Bentim PR, Voloch CM, Rossi ÁD, da Costa RM, et al. MATERNAL SARS-COV-2 infection associated to systemic inflammatory response and pericardial effusion in the newborn: a case report. J Pediatr Infect Dis Soc. 2020;10((4)):536–9. doi: 10.1093/jpids/piaa133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Magboul S, Hassan M, Al Amri M, Alhothy A, Almaslamani E, Ellithy K, et al. Refractory multi-inflammatory syndrome in a two weeks old neonate with COVID-19 treated successfully with intravenous immunoglobulin, steroids and anakinra. Open Access J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2020;5((4)) [Google Scholar]

- 25.Orlanski-Meyer E, Yogev D, Auerbach A, Megged O, Glikman D, Hashkes PJ, et al. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 in an 8-week-old infant. J Pediatr Infect Dis Soc. 2020;9((6)):781–4. doi: 10.1093/jpids/piaa137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saha S, Pal P, Mukherjee D. Neonatal MIS-C: managing the cytokine storm. Pediatrics. 2021;148((5)):e2020042093. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-042093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schoenmakers S, Snijder P, Verdijk RM, Kuiken T, Kamphuis SS, Koopman LP, et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 placental infection and inflammation leading to fetal distress and neonatal multi-organ failure in an asymptomatic woman. J Pediatr Infect Dis Soc. 2020;10((5)):556–61. doi: 10.1093/jpids/piaa153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shaiba LA, Hadid A, Altirkawi KA, Bakheet HM, Alherz AM, Hussain SA, et al. Case report: Neonatal multi-system inflammatory syndrome associated with SARS-COV-2 exposure in two cases from Saudi Arabia. Front Pediatr. 2021;9:652857. doi: 10.3389/fped.2021.652857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang J, D'Souza R, Kharrat A, Fell DB, Snelgrove JW, Murphy KE, et al. COVID-19 pandemic and population-level pregnancy and neonatal outcomes: a living systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2021;100((10)):1756–70. doi: 10.1111/aogs.14206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang Z, Wang M, Zhu Z, Liu Y. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and pregnancy: a systematic review. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2020;35:1619–22. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2020.1759541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McMurray JC, May JW, Cunningham MW, Jones OY. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C), a post-viral myocarditis and systemic vasculitis: a critical review of its pathogenesis and treatment. Front Pediatr. 2020;8:626182. doi: 10.3389/fped.2020.626182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Radia T, Williams N, Agrawal P, Harman K, Weale J, Cook J, et al. Multi-system inflammatory syndrome in children & adolescents (MIS-C): a systematic review of clinical features and presentation. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2021;38:51–7. doi: 10.1016/j.prrv.2020.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Antúnez-Montes OY, Escamilla MI, Figueroa-Uribe AF, Arteaga-Menchaca E, Lavariega-Sárachaga M, Salcedo-Lozada P, et al. COVID-19 in South American children: a call for action. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2020;39((10)):e332–4. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000002851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Consiglio CR, Cotugno N, Sardh F, Pou C, Amodio D, Rodriguez L, et al. The immunology of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children with COVID-19. Cell. 2020;183((4)):968–81.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zambrano LD, Newhams MM, Olson SM, Halasa NB, Price AM, Boom JA, et al. Effectiveness of BNT162b2 (Pfizer-BioNTech) mRNA vaccination against multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children among persons aged 12–18 years: United States, July–December 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:52–8. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7102e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The research data obtained from the included articles are available and can be requested from the corresponding author and will be made available when requested.