Abstract

Introduction

This study aimed to compare the mental health, quality of life, and caregiving burden between male and female informal caregivers of older adults (≥60 years) during the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in Germany.

Methods

The sample consisted of 301 female and 188 male informal caregivers of older adults in need of care (≥60 years). Data were used from a cross-sectional study in March 2021 that questioned a representative sample of adults aged 40 years and older from Germany. Information on informal care provision, mental health (depressive and anxiety symptoms), caregiving burden, and quality of life was assessed for the period between December 2020 and March 2021. Regression analyses, adjusted for (1) the sociodemographic background and health of the caregivers, (2) the caregiving time and caregiving tasks, and (3) the perception of impairment and danger posed by the pandemic, were conducted.

Results

Findings of the fully adjusted model indicated a higher level of anxiety and lower quality of life among female caregivers, compared to male caregivers. Gender differences in depression and caregiver burden were not significant in analyses that controlled for care tasks and time. Moderator analyses indicated that gender differences in caregiver's anxiety levels were influenced by the danger perceived to be posed by the pandemic: among men the danger to the care recipient, and among women the danger to themselves, increased anxiety.

Conclusion

Female informal caregivers were more negatively affected than male informal caregivers during the pandemic, as indicated by higher levels of anxiety and lower quality of life. Gender differences in anxiety depended on the perceived danger posed by the pandemic. Thus, policy and pandemic measures should focus on gender-specific support of female caregivers who seem to be particularly vulnerable during the pandemic. More caregiver-specific support and information around protecting themselves and their care recipients are recommended. Also, further research on gender differences in care performance and their relation to psychosocial health outcomes is recommended.

Keywords: COVID-19, Pandemic, Informal caregiving, Gender, Psychosocial health

Introduction

Around the globe, the COVID-19 pandemic has impacted the mental health and wellbeing of the general population negatively [1, 2, 3, 4]. However, different population groups may be more vulnerable than others. Identifying these groups is highly important to inform future policy decisions and enable the provision of appropriate support during this health crisis and in the future.

One group that has been found to be more vulnerable with respect to reduced health and wellbeing are informal caregivers of relatives, friends, or neighbors [5, 6] with health- or age-related impairments. This group represents a central aspect of health care. In Europe, around a third of the adult population provides informal care [7]. In Germany, this reflects the care-at-home policy of the care system. Individuals can receive financial support from nursing care insurance for the use of ambulatory care services when cared for at home, if the criteria for a significant impairment are fulfilled [8]. At the end of 2019, about 80% of those who fulfilled the criteria for a significant impairment received care at home. Despite the formal care options, the majority of those (about 70%) still only received support from informal caregivers [9]. Thus, in Germany, the majority of care for older adults is provided by informal caregivers, and this is likely to have also been the case during the pandemic. Moreover, the majority of informal caregivers can be expected to be women, as has been found in the previous research on informal caregiving in the USA and Europe [7, 10, 11]. Thus, research on gender differences in health and wellbeing in the informal care context during the pandemic is required to ascertain whether female caregivers may be a particularly vulnerable group during the COVID-19 pandemic. These findings could inform policy decisions regarding gender-specific support actions, as well as help to identify the groups to be targeted primarily during the pandemic and in future similar crisis situations, in order to prevent or lessen the health deterioration among informal caregivers.

Theoretical Framework

Pre-pandemic findings indicated that the health and wellbeing of informal caregivers differed between men and women. Poorer mental health (e.g., depressive symptoms) and higher caregiver burden have been found among female caregivers, when compared to male caregivers [12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17], although this was not found consistently [18, 19]. Some studies have also reported better quality of life among male caregivers, compared to female caregivers [20, 21]. In brief, previous findings indicate a gender gap in health, burden, and wellbeing among informal caregivers. However, this was found inconsistently and research often did not include possible confounders that may be of relevance in this context, such as caregiving time or caregiving tasks, although previous findings indicated that these factors are relevant [22, 23, 24] and can differ between men and women [12].

Moreover, research has shown that the pandemic and the pandemic restrictions (e.g., working from home, closure of day care facilities for children and older people [25, 26]) have impacted women and men differently in their work and family life. For example, more men worked from home and undertook short-term work than women during the pandemic [27]. Men may therefore have had more opportunity to make use of the flexible ways of working to become more involved in family life. Due to the different family and work situation during the pandemic, the gender gap in health, wellbeing, and burden in informal caregivers may thus change during the COVID-19 pandemic. Thus, research that analyzes gender differences in informal caregiving during the COVID-19 pandemic and that takes into account the characteristics of caregiving is required. This could provide insight into the gender-specific burden of caregiving and indicate if it is still women who are primarily affected by care provision despite the changes in work and family life seen during the pandemic. Moreover, results may help to identify which aspects of the caregiving situation (e.g., care time or tasks) may contribute to gender differences and should be targeted primarily with gender-specific interventions.

Literature Review

To date, only few studies have investigated the informal caregiving situation during the pandemic. In particular, further research on the gender differences in psychosocial health, wellbeing, and burden of informal caregivers is needed.

Studies from China [28] and Italy [29] indicated, for example, a higher risk of anxiety during the pandemic among female caregivers. However, Zucca et al. [29] did not use validated instruments, and Li et al. [28] surveyed only a convenience sample of caregivers of individuals with neurocognitive disorders. Further findings from Austria [30], using two cross-sectional quota-samples, indicated that male caregivers experienced increased depressive symptoms during the pandemic, but no differences were found for female caregivers. However, female caregivers still reported more depressive symptoms than men. In the USA, poorer well-being was found among female caregivers as well [5]. Adding to this, a descriptive, representative study from Germany [31] found that a larger proportion of female caregivers, compared to male caregivers, reported depressive symptoms during the pandemic. Results from Serbia [32] indicate lower mental and physical health among female compared to male caregivers during the pandemic, however, this difference was not significant. Poorer mental health was found in female caregivers compared to male caregivers in the UK as well, from before to during the first pandemic wave, but this gender difference was no longer found after the first wave (during summer 2020) [33]. A longitudinal representative Dutch study [34] analyzed caregiving burden. Their findings suggest that women were more likely to have lower burden during the pandemic compared to before the pandemic than was found among men, and men had in general a higher increase in burden than women. However, in this study, no validated instruments were used.

In sum, findings are not consistent with respect to gender differences in health and wellbeing of informal caregivers during the pandemic, and previous research leaves various research gaps which require further analysis. For example, further research comparing male and female caregivers directly with each other is needed, as this was not done by some of the previous studies (e.g., [30]). Moreover, it was primarily international studies that investigated gender differences in informal care. However, the pandemic developed and was managed differently worldwide. To draw conclusions for Germany, analyses of national data are therefore needed. Yet, research from Germany has been, to date, only descriptive [31]. Also, international studies have not always used established and validated instruments [29, 34] and often only used convenience samples (e.g., [28, 32]). Furthermore, all studies were conducted during the first or shortly after the first pandemic wave. During this time, the number of infections was still low compared with the second pandemic wave in Germany, which reached its peak of weekly infections in December 2020, and the peak of deaths in January 2021 [35]. During the second wave, the German government had also issued strict measures, such as a lockdown (e.g., closure of schools, day care, and retail; private meetings were restricted [25]), obligations to wear mouth-nose-protection, testing strategies in nursing homes, and new entry regulations for travelers [36]. These measures from December 2020 were extended multiple times (with some adaptions) at the beginning of 2021 [36, 37, 38].

Therefore, research that was conducted during the worst phase of the pandemic to date, uses a representative sample from Germany, and compares male and female caregivers with well-established and validated instruments is required in order to be able to draw conclusions whether and what kind of gender differences among informal caregivers can be found in psychosocial health and wellbeing in Germany during the COVID-10 pandemic.

Objectives

This study aims to fill current research gaps by analyzing gender differences in mental health, quality of life, and caregiver burden among informal caregivers during the pandemic, using data from a representative sample of informal caregivers aged ≥40 years from Germany. This sample was questioned during the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, using well-established and validated instruments.

Materials and Methods

Sample

Data were collected between the 4th and 19th of March 2021 and questions referred to the 3 months prior to the survey. The sample was drawn randomly from the forsa.omninet online panel in cooperation with the market research institute forsa, weighted by age, gender, and federal state and included only individuals aged 40 years or older (N = 3,022). We focused only on adults in the second half of life because the majority of informal caregivers in Europe and the USA have been found to be at least 40 years of age [7, 10, 11]. Forsa.omninet is based on the sample from forsa.omnitel, which is drawn randomly according to the ADM-phone sampling scheme (dual-frame sample, including home and mobile phone numbers). Thus, the basic sample was assessed via phone (offline) and can be seen as representative for the population in the second half of life. In this study, we focused only on informal caregivers from the project's sample (N = 489, 16% of the complete sample). Informal caregiving is defined as care provision for a relative, friend, neighbor, or other acquaintance aged ≥60 years during the last 3 months (i.e., December 2020 to March 2021) at least once per week, in terms of help with, for example, personal hygiene, mobility, or household tasks.

Written informed consent was provided by all participants before their participation in the online survey. Approval for the study was given by the Local Psychological Ethics Committee of the Center for Psychosocial Medicine of the University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf (LPEK-0239).

Variables

Mental health was assessed using two well-established, validated self-report questionnaires. Depressive symptoms were measured using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) [39, 40], which has excellent composite reliability = 0.94 [40]. Higher scores of the sum score (9 items, Range: 0–27) indicate more depressive symptoms. Anxiety symptoms were assessed with the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Screener (GAD-7) [41, 42], which also has good reliability (Cronbach's α = 0.89 [42]). Higher scores in the sum score (7 items, Range: 0–21) indicate more anxiety symptoms.

Caregiving burden was assessed with the Burden Scale for Family Caregivers short version (BSFCs) [43], a well-established instrument with good reliability (Cronbach's α = 0.92 [44]). It assesses the burden of informal caregiving with 10 items (e.g., “My standard of living has decreased due to caregiving,” “I often feel physically exhausted.”). Higher scores in the sum score (Range: 0–30) indicate higher caregiver burden.

Quality of life was assessed with the CASP-12 [45, 46], a short form of CASP-19 that assesses quality of life in four areas: control, autonomy, self-realization, and pleasure. Higher scores in the sum score (12 Items, Range: 12–48) indicate higher quality of life. It is a well-used instrument that is integrated in European panel studies, such as the Study of Health Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) [47], and has good internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha = 0.83 [46]).

Caregiving time was measured by asking informal caregivers to report the number of hours per week they provided informal care. Caregiving tasks were measured by asking respondents to indicate (no/yes; multiple answers possible) whether they undertook the following tasks: personal hygiene, dressing, feeding, household tasks, supervision, transportation, medication intake, or help with financial matters.

Indicators related to the COVID-19 pandemic were assessed, including perceived impairment of daily life by the pandemic, perceived impairment in caregiving routine due to the pandemic, perceived danger to themselves, and perceived danger to their care recipients. Answers for all variables ranged from 1 “not at all” to 5 “very,” with higher scores indicating greater levels of perceived impairment or danger.

Lastly, participants were asked to provide information on their sociodemographic background (e.g., age, education, marital status, income) and health (for detailed information see Appendix 1). To be able to compare female and male informal caregivers, gender (male, female) was used as the main predictor variable, with male as the reference group.

Statistics

In the descriptive results section, the average mean and standard deviations are given for continuous variables and frequency and percentage for categorical variables. χ2 tests and unpaired t tests were calculated for unadjusted comparisons. Ordinary Least Squares regression analyses adjusted (1) for sociodemographic background and health of caregivers, (2) for aspects of the care performance, namely, caregiving time and care tasks, and (3) for indicators of impairment and danger posed by the pandemic were conducted. Variance inflation factors were all well below 5, indicating no multicollinearity. Robust standard errors were calculated for all models. Alpha-level was set at 0.05 and all analyses were performed with Stata version 16.1 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Descriptive Results Provided for the Sample of Informal Caregivers

Descriptive results are provided in Table 1. The sample consisted of 301 female caregivers, aged on average 57.61 (SD = 9.85) years, and 188 male caregivers, aged on average 59.12 (SD = 9.30) years. They differed significantly in their employment situation during the pandemic as shown by the χ2 tests (χ2(4) = 77.08, p < 0.001). More male caregivers were full-time employed (57.22% vs. 27.33% female caregivers), and more female caregivers were part-time employed (31.33% vs. 5.35% male caregivers); also, more male caregivers were retired (30.48% vs. female caregivers 23.67%), and more female caregivers were unemployed (11.67% vs. 6.42% male caregivers). With respect to the outcome variables, the unpaired t tests indicated that female caregivers reported significantly more depressive (t = −2.19, p < 0.05, Cohen's d = −0.21, CI [−0.40; −0.02]) and anxiety symptoms (t = −2.88, p < 0.01, Cohen's d = −0.27, CI [−0.46; −0.09]) than male caregivers. Quality of life was on average lower among female caregivers compared to male caregivers (unpaired t test, t = 3.27, p < 0.01, Cohen's d = 0.32, CI [0.12; 0.51]). Higher caregiver burden was reported by female caregivers compared to male caregivers (unpaired t test, t = −2.49, p < 0.05, Cohen's d = −0.24, CI [−0.43; −0.05]).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for informal caregivers (N = 489) during the second wave of the pandemic differentiated by gender

| M (SD)/N (%) |

p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| female informal caregivers (N = 301) | male informal caregivers (N = 188) | ||

| Age, years | 57.61 (9.85) | 59.12 (9.30) | ns |

| Highest educational degree | |||

| Upper secondary school | 70 (23.49) | 56 (30.27) | |

| Qualification for applied upper secondary school | 35 (11.74) | 18 (9.73) | |

| Polytechnic secondary school | 22 (7.38) | 18 (9.73) | ns |

| Intermediate secondary school | 114 (38.26) | 59 (31.89) | |

| Lower secondary school | 57 (19.13) | 34 (18.38) | |

| Marital status | |||

| Married/partnership | 215 (71.67) | 130 (69.52) | |

| Divorced | 31 (10.33) | 23 (12.30) | |

| Widowed | 18 (6.00) | 6 (3.21) | ns |

| Single | 36 (12.00) | 28 (14.97) | |

| Living situation | |||

| Living alone in private household | 70 (23.33) | 44 (23.78) | |

| Living with others in private household | 228 (76.00) | 140 (75.68) | ns |

| Living in assisted living, retirement home or nursing home | 2 (0.67) | 1 (0.54) | |

| Children in one's household | |||

| No, no children in household | 230 (76.67) | 155 (84.24) | |

| Yes, children in the household (<14 years) | 31 (10.33) | 12 (6.52) | ns |

| Yes, children in the household (14–18 years) | 39 (13.00) | 17 (9.24) | |

| Employment status | |||

| Employed (full-time) | 82 (27.33) | 107 (57.22) | |

| Employed (part-time) | 94 (31.33) | 10 (5.35) | |

| Marginally employed | 18 (6.00) | 1 (0.53) | <0.001 |

| Retired | 71 (23.67) | 57 (30.48) | |

| Unemployed | 35 (11.67) | 12 (6.42) | |

| Monthly household net income1 | 6.59 (2.72) | 7.08 (2.78) | ns |

| Self-rated health | 3.46 (0.88) | 3.39 (0.92) | ns |

| Chronic physical illnesses | 1.98 (1.59) | 2.04 (1.51) | ns |

| Outcomes | |||

| Depressive symptoms | 5.85 (4.75) | 4.86 (4.74) | <0.05 |

| Anxiety symptoms | 5.23 (4.28) | 4.07 (4.19) | <0.01 |

| Quality of life | 35.02 (6.65) | 37.07 (6.07) | <0.01 |

| Caregiver burden | 9.18 (7.92) | 7.35 (6.97) | <0.05 |

| Additional covariates | |||

| Perceived impairment in daily life by the pandemic | 3.05 (1.04) | 2.85 (1.03) | <0.05 |

| Perceived danger of the pandemic to themselves | 2.90 (0.98) | 2.76 (0.97) | ns |

| Perceived impairment in their caregiving routine by the pandemic | 2.16 (1.11) | 2.23 (1.02) | ns |

| Perceived danger to their care recipients | 3.19 (1.18) | 3.24 (1.14) | ns |

| Caregiving time, h/week | 12.62 (21.01) | 11.52 (17.01) | ns |

| Caregiving task − personal hygiene | 88 (29.24) | 34 (18.09) | <0.01 |

| Caregiving task − dressing | 78 (25.91) | 31 (16.49) | <0.05 |

| Caregiving task − feeding | 126 (41.86) | 71 (37.77) | ns |

| Caregiving task − household help | 240 (79.73) | 131 (69.68) | <0.05 |

| Caregiving task − supervision | 82 (27.24) | 52 (27.66) | ns |

| Caregiving task − transportation | 205 (68.11) | 132 (70.21) | ns |

| Caregiving task − medication intake | 105 (34.88) | 56 (29.79) | ns |

| Caregiving task − help with financial matters | 148 (49.17) | 92 (48.94) | ns |

Depressive symptoms (PHQ-9, Range: 0–27), higher scores indicate more depressive symptoms; anxiety symptoms (GAD-7, Range: 0–21), higher scores indicate more anxiety symptoms; quality of life (CASP-12, Range: 12–48), higher scores indicate higher quality of life; caregiver burden (BSFCs, Range: 0–30), with higher scores indicating higher caregiver burden; self-rated health (Range 1–5), higher scores indicate better health; number of chronic physical illnesses (Range: 0–13), higher scores indicate worse health; perceived impairment in daily life/in their caregiving routine (Range: 1–5), higher scores indicate higher levels of perceived impairment; perceived danger to themselves/to their care recipients (Range: 1–5), higher scores indicate higher levels of perceived danger. 1 Monthly household net income was assessed with 13 consecutive categories (e.g., <500 EUR, 500 EUR to <1.000 EUR, 1,000 EUR to <1.500 EUR, 1.500 EUR to <2.000 EUR) and is treated as a continuous variable in the analyses of this study.

Regression Analyses

Results of the three sets of adjusted regression analyses can be found in Table 2. Models 1–4 describe the results of the regression analyses, which are adjusted for sociodemographic and health factors. These findings revealed statistically significant higher depressive symptoms (b = 1.00, p < 0.05), anxiety symptoms (b = 1.38, p < 0.01), and burden (b = 2.00, p < 0.05) and lower quality of life (b = −2.16, p < 0.01) among female caregivers compared to male caregivers. In models 5–8, we additionally adjusted for care tasks and care time. Gender differences in these models remained significant for anxiety symptoms (b = 1.12, p < 0.05) and quality of life (b = −1.90, p < 0.05) but not for depressive symptoms (b = 0.79, p = 0.105) and burden (b = 1.06, p = 0.176).

Table 2.

Results of OLS regression analyses for all outcomes (mental health, quality of life, caregiver burden) with models (1–4) adjusted for caregiver characteristics (sociodemographic background and health), models (5–8) additionally adjusted for aspects of care performance (care tasks and caregiving time) and models (9–12) additionally adjusted for pandemic indicators (perceived impairment in daily life and caregiving routine and perceived danger for themselves and for care recipient; fully adjusted models)

| Depressive symptoms (OLS) (1) | Anxiety symptoms (OLS) (2) | Quality of life (OLS) (3) | Caregiver burden (OLS) (4) | Depressive symptoms (OLS) (5) | Anxiety symptoms (OLS) (6) | Quality of life (OLS) (7) | Caregiver burden (OLS) (8) | Depressive symptoms (OLS) (9) | Anxiety symptoms (OLS) (10) | Quality of life (OLS) (11) | Caregiver burden (OLS) (12) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender of informal caregiver (réf. male) | 1.00* | 1.38** | –2.16** | 2.00* | 0.79 | 1.12* | –1.90* | 1.06 | 0.80+ | 1.03* | –1.81* | 1.13 |

| (0.48) | (0.45) | (0.68) | (0.86) | (0.49) | (0.48) | (0.74) | (0.78) | (0.48) | (0.46) | (0.74) | (0.76) | |

| Age | –0.11** | –0.07+ | 0.07 | –0.02 | –0.12** | –0.08+ | 0.05 | 0.04 | –0.13** | –0.09* | 0.05 | –0.01 |

| (0.04) | (0.04) | (0.05) | (0.06) | (0.04) | (0.04) | (0.05) | (0.06) | (0.04) | (0.04) | (0.05) | (0.06) | |

| Highest educational degree (ref. upper secondary school) | ||||||||||||

| Lower secondary school | –0.27 | –0.52 | –1.93* | 0.46 | –0.74 | –0.65 | –1.74+ | –0.03 | –0.47 | –0.38 | –2.15* | 0.19 |

| (0.67) | (0.63) | (0.97) | (1.15) | (0.72) | (0.64) | (1.05) | (1.11) | (0.72) | (0.65) | (1.08) | (1.08) | |

| Intermediate secondary school | –0.50 | –0.63 | –1.04 | 1.19 | –0.38 | –0.40 | –0.75 | 1.26 | –0.45 | –0.34 | –0.90 | 0.89 |

| (0.57) | (0.52) | (0.80) | (1.02) | (0.60) | (0.54) | (0.83) | (0.95) | (0.57) | (0.53) | (0.81) | (0.89) | |

| Polytechnic secondary school | –1.33 | –0.83 | –0.46 | –0.59 | –1.43 | –0.61 | –0.62 | –0.65 | –1.70+ | –0.84 | –0.61 | –0.90 |

| (0.82) | (0.76) | (1.19) | (1.49) | (0.89) | (0.84) | (1.32) | (1.32) | (0.89) | (0.83) | (1.33) | (1.23) | |

| Qualification for applied upper secondary school | –0.23 | –0.53 | –0.69 | –0.77 | 0.18 | –0.13 | –1.01 | –0.05 | 0.21 | –0.16 | –1.07 | 0.12 |

| (0.79) | (0.73) | (1.07) | (1.40) | (0.83) | (0.78) | (1.12) | (1.35) | (0.81) | (0.75) | (1.14) | (1.35) | |

| Marital status (ref. married/partnership) | ||||||||||||

| Divorced | –0.45 | 0.53 | 0.46 | –2.96* | –0.49 | 0.95 | 0.12 | –1.50 | –0.57 | 0.76 | 0.41 | –1.57 |

| (0.77) | (0.75) | (0.99) | (1.24) | (0.75) | (0.83) | (1.07) | (1.25) | (0.74) | (0.81) | (1.09) | (1.26) | |

| Widowed | 0.57 | 0.00 | 1.71 | –4.81** | 1.15 | 1.30 | –0.40 | –3.13 | 1.45 | 1.81 + | –0.29 | –2.16 |

| (0.82) | (0.95) | (1.44) | (1.85) | (0.89) | (0.90) | (1.75) | (1.90) | (0.97) | (0.95) | (1.58) | (1.88) | |

| Single | –0.30 | 0.38 | –1.38 | –2.29+ | –0.49 | 0.20 | –2.12 | –1.96 | –0.37 | 0.31 | –2.14 | –1.67 |

| (0.88) | (0.82) | (1.20) | (1.26) | (0.96) | (0.91) | (1.38) | (1.29) | (0.87) | (0.84) | (1.33) | (1.25) | |

| Living situation (ref. living alone in private household) | ||||||||||||

| Living with others in private household | –0.43 | –0.10 | 0.36 | –1.52 | –0.23 | 0.14 | –0.21 | –1.49 | –0.12 | 0.23 | –0.50 | –1.11 |

| (0.65) | (0.62) | (0.90) | (1.16) | (0.73) | (0.71) | (1.00) | (1.17) | (0.71) | (0.69) | (0.94) | (1.17) | |

| Living in assisted living, retirement home or nursing home | –1.27 | –1.44 | 3.54 | –6.45*** | –3.11 + | –1.31 | 5.92 | –9.67*** | –3.70** | –1.37 | 6.49+ | –10.10*** |

| (1.99) | (1.35) | (3.66) | (1.84) | (1.75) | (1.42) | (4.38) | (1.89) | (1.26) | (1.18) | (3.74) | (2.13) | |

| Children in the household (ref. no) | ||||||||||||

| Yes, children ≤13 years | –0.08 | –0.03 | 0.12 | –1.65 | –0.24 | –0.29 | –0.23 | –0.02 | –0.25 | –0.23 | –0.16 | 0.54 |

| (0.77) | (0.73) | (1.16) | (1.37) | (0.76) | (0.73) | (1.17) | (1.36) | (0.76) | (0.74) | (1.18) | (1.33) | |

| Yes, children between 14 and 18 years | 0.67 | 0.43 | –0.14 | 0.64 | 1.15 | 0.66 | 0.12 | 1.48 | 1.19+ | 0.62 | –0.01 | 1.82+ |

| (0.82) | (0.69) | (0.92) | (1.25) | (0.74) | (0.68) | (1.00) | (1.04) | (0.72) | (0.67) | (1.01) | (0.98) | |

| Employment status (ref. 3 employed [full-time]) | ||||||||||||

| Employed (part-time) | –0.53 | –0.55 | 0.68 | –0.05 | –0.81 | –0.55 | 0.73 | –0.20 | –1.02+ | –0.75 | 0.82 | –0.65 |

| (0.62) | (0.60) | (0.87) | (1.14) | (0.61) | (0.60) | (0.89) | (1.04) | (0.59) | (0.58) | (0.86) | (0.97) | |

| Marginally employed | –1.38+ | –1.49+ | 2.83* | –5.37** | –1.54+ | –2.13* | 2.84+ | –5.28** | –1.54+ | –2.12* | 3.71* | –5.21** |

| (0.80) | (0.88) | (1.31) | (1.82) | (0.82) | (0.92) | (1.64) | (1.82) | (0.90) | (0.93) | (1.79) | (1.63) | |

| Retired | –0.34 | –0.52 | 0.90 | –0.86 | –0.39 | –0.60 | 1.66 | –1.42 | –0.43 | –0.64 | 1.67 | –1.20 |

| (0.82) | (0.79) | (1.07) | (1.38) | (0.88) | (0.85) | (1.15) | (1.33) | (0.88) | (0.87) | (1.16) | (1.30) | |

| Unemployed | 1.28 | 0.89 | –0.28 | –0.15 | 1.46 | 1.26 | –0.22 | –1.19 | 1.07 | 0.81 | 0.52 | –1.88 |

| (0.93) | (0.81) | (1.24) | (1.63) | (0.96) | (0.85) | (1.27) | (1.40) | (0.96) | (0.85) | (1.21) | (1.33) | |

| Monthly household net income1 | –0.14 | 0.03 | 0.38** | –0.25 | –0.23* | 0.04 | 0.35* | –0.21 | –0.23* | 0.05 | 0.36** | –0.20 |

| (0.10) | (0.09) | (0.13) | (0.17) | (0.10) | (0.10) | (0.14) | (0.16) | (0.09) | (0.09) | (0.14) | (0.14) | |

| Chronic physical illnesses | 0.85*** | 0.72*** | –0.49* | 0.71* | 0.85*** | 0.77*** | –0.53+ | 0.50 | 0.85*** | 0.76*** | –0.59* | 0.49+ |

| (0.21) | (0.18) | (0.24) | (0.32) | (0.20) | (0.19) | (0.27) | (0.31) | (0.20) | (0.18) | (0.27) | (0.28) | |

| Self-rated health | –1.69*** | –1.16*** | 2.62*** | –1.32* | –1.47*** | –1.00** | 2.56*** | –1.44** | –1.34*** | –0.85** | 24i*** | –1.05* |

| (0.35) | (0.31) | (0.39) | (0.52) | (0.34) | (0.30) | (0.41) | (0.50) | (0.33) | (0.30) | (0.39) | (0.47) | |

| Caregiving time, h/week | –0.02 | 0.00 | 0.04+ | –0.02 | –0.01 | 0.00 | 0.03 | –0.02 | ||||

| (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.02) | (0.03) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.02) | (0.02) | |||||

| Caregiving task − personal hygiene (ref. no) | 1.12+ | –0.06 | –1.96* | 4 29*** | 0.99 | –0.13 | –1.61 + | 3.71*** | ||||

| (0.65) | (0.57) | (0.93) | (1.15) | (0.65) | (0.57) | (0.94) | (1.09) | |||||

| Caregiving task − dressing (ref. no) | –0.65 | –0.18 | 0.58 | –1.13 | –0.41 | –0.09 | 0.55 | –0.75 | ||||

| (0.69) | (0.63) | (0.92) | (1.21) | (0.68) | (0.63) | (0.91) | (1.14) | |||||

| Caregiving task-feeding (ref. no) | 0.79 | 0.42 | 0.43 | 2.36** | 0.38 | –0.04 | 0.93 | 1.64* | ||||

| (0.49) | (0.46) | (0.73) | (0.85) | (0.48) | (0.44) | (0.73) | (0.82) | |||||

| Caregiving task − household help (ref. no) | 0.58 | 0.92+ | –0.96 | 1.89* | 0.64 | 0.89+ | –1.25 | 1.73+ | ||||

| (0.50) | (0.49) | (0.74) | (0.95) | (0.48) | (0.48) | (0.76) | (0.93) | |||||

| Caregiving task − supervision (ref. no) | 0.63 | 0.60 | –1.46+ | 3 44*** | 0.25 | 0.52 | –1.18 | 2.77** | ||||

| (0.56) | (0.55) | (0.84) | (0.96) | (0.55) | (0.54) | (0.87) | (0.96) | |||||

| Caregiving task − transportation (ref. no) | 0.23 | 0.33 | 0.64 | 1.28 | 0.15 | 0.38 | 0.64 | 1.01 | ||||

| (0.54) | (0.52) | (0.69) | (0.83) | (0.53) | (0.51) | (0.69) | (0.80) | |||||

| Caregiving task − medication intake (ref. no) | –0.30 | 0.12 | –0.03 | 1.47 | –0.34 | 0.21 | –0.27 | 1.60+ | ||||

| (0.60) | (0.58) | (0.84) | (0.97) | (0.58) | (0.57) | (0.85) | (0.95) | |||||

| Caregiving task − help with financial matters (ref. no) | 0.47 | –0.12 | –0.55 | 2.22** | 0.66 | –0.05 | –0.61 | 2.17** | ||||

| (0.47) | (0.46) | (0.65) | (0.75) | (0.47) | (0.45) | (0.65) | (0.71) | |||||

| Perceived impairment by the pandemic in daily life | 0.41 + | 0.38 | –0.68* | –0.27 | ||||||||

| (0.23) | (0.25) | (0.33) | (0.38) | |||||||||

| Perceived impairment by the pandemic in caregiving routine | 0.78** | 0.52* | –0.60+ | 2.06*** | ||||||||

| (0.27) | (0.25) | (0.36) | (0.41) | |||||||||

| Perceived danger for the care recipient | –0.01 | 0.04 | –0.07 | –0.45 | ||||||||

| (0.23) | (0.22) | (0.29) | (0.35) | |||||||||

| Perceived danger for themselves | 0.25 | 0.51 + | 0.04 | 0.93* | ||||||||

| (0.28) | (0.28) | (0.35) | (0.44) | |||||||||

| Constant | 18.51*** | 12.10*** | 22.49*** | 16.98*** | 17.35*** | 10.33*** | 25.45*** | 7.62 | 14.25*** | 6.45* | 29.42*** | 4.44 |

| (2.66) | (2.57) | (3.69) | (4.78) | (2.89) | (2.77) | (4.09) | (4.75) | (3.04) | (2.90) | (4.43) | (4.78) | |

| Observations | 386 | 398 | 361 | 381 | 342 | 354 | 322 | 342 | 337 | 348 | 317 | 338 |

| R2 | 0.31 | 0.22 | 0.32 | 0.14 | 0.36 | 0.25 | 0.35 | 0.35 | 0.41 | 0.31 | 0.38 | 0.43 |

OLS regression analyses were conducted, unstandardized beta coefficients are given with robust standard errors in parentheses; listwise deletion was used for missing values. OLS, Ordinary Least Squares. Level of significance: ***p< 0.001, **p< 0.01, *p< 0.05, +p< 0.10.1 Monthly household net income was assessed with 13 consecutive categories (e.g., <500 EUR, 500 EUR to <1.000 EUR, 1,000 EUR to <1.500 EUR, 1.500 EUR to <2.000 EUR) and is treated as a continuous variable in the analyses of this study.

Models 9–12 show the results after additionally adjusting for pandemic indicators as well; these are the fully adjusted models. In these models, gender differences in depressive symptoms (b = 0.80, p = 0.098) and burden (b = 1.13, p = 0.137) remained nonsignificant, and differences in anxiety symptoms (b = 1.03, p < 0.05) and quality of life (b = −1.81, p < 0.05) remained significant.

Moderator Analyses

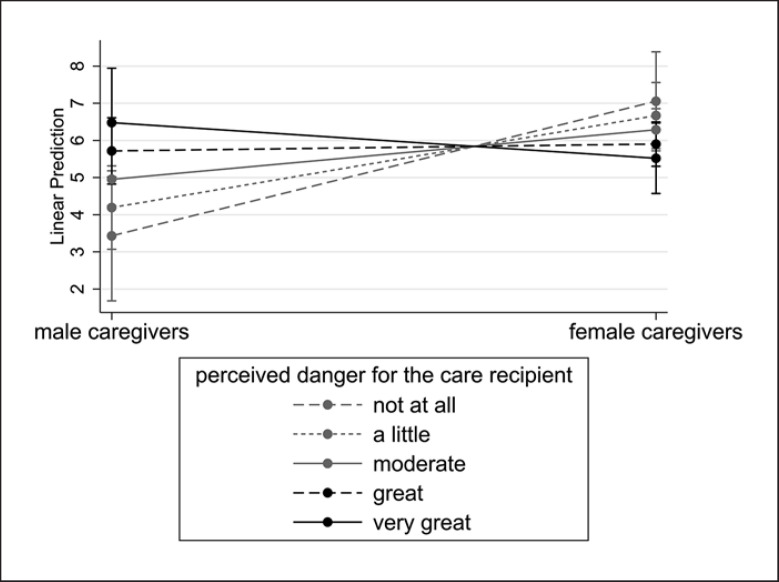

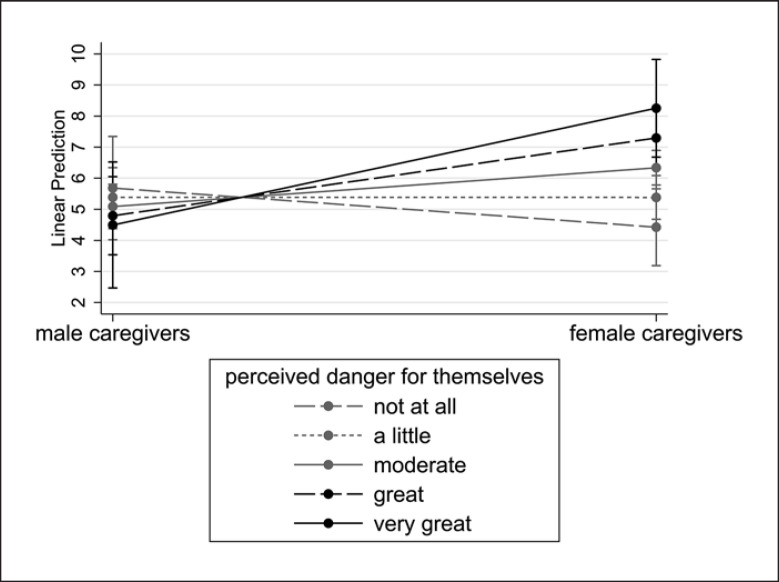

A significant interaction effect was found between gender and perceived danger to care recipients (b = −1.15, p < 0.05) and to themselves (b = 1.25, p < 0.05) due to the pandemic for the model with anxiety symptoms as outcome (Table 3). As shown in the predictive margins plots, among male caregivers, anxiety symptoms increased with higher perceived levels of danger to the care recipient, until they reached a similar level as found in female caregivers (Fig. 1). Among female caregivers, anxiety symptoms increased with growing levels of perceived danger to themselves to a higher level than was found among male caregivers (Fig. 2).

Table 3.

Moderator analyses including the following four interaction effects: gender × perceived danger for themselves; gender × perceived danger for care recipient; gender × perceived impairment by the pandemic in daily life; gender × perceived impairment by the pandemic in caregiving routine

| (1) Depressive symptoms | (2) Anxiety symptoms | (3) Quality of life | (4) Caregiver burden | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender of informal caregiver (ref. male) | 0.73 | 1.50 | –4.73 | 3.73 |

| (1.99) | (1.81) | (3.12) | (3.03) | |

|

| ||||

| Perceived impairment by the pandemic in daily life | 0.23 | 0.36 | –0.35 | 0.20 |

| (0.37) | (0.36) | (0.45) | (0.49) | |

|

| ||||

| Gender × perceived impairment by the pandemic in daily life | 0.29 | 0.06 | –0.63 | –0.64 |

| (0.46) | (0.48) | (0.63) | (0.67) | |

|

| ||||

| Perceived impairment by the pandemic in caregiving routine | 1.09* | 0.70 | –0.89 | 1.79** |

| (0.49) | (0.45) | (0.58) | (0.60) | |

|

| ||||

| Gender × perceived impairment by the pandemic in caregiving routine | –0.46 | –0.22 | 0.45 | 0.40 |

| (0.58) | (0.54) | (0.68) | (0.81) | |

|

| ||||

| Perceived danger for the care recipient | 0.32 | 0.76* | –0.31 | 0.11 |

| (0.39) | (0.37) | (0.48) | (0.54) | |

|

| ||||

| Gender × perceived danger for the care recipient | –0.53 | –1.15* | 0.36 | –0.90 |

| (0.46) | (0.44) | (0.61) | (0.71) | |

|

| ||||

| Perceived danger for themselves | –0.19 | –0.30 | –0.49 | 0.67 |

| (0.44) | (0.43) | (0.57) | (0.66) | |

|

| ||||

| Gender × perceived danger for themselves | 0.69 | 1.25* | 0.92 | 0.42 |

| (0.55) | (0.54) | (0.73) | (0.83) | |

|

| ||||

| Age | –0.13** | –0.08+ | 0.04 | –0.00 |

| (0.04) | (0.04) | (0.05) | (0.06) | |

|

| ||||

| Highest educational degree (ref. upper secondary school) | ||||

| Lower secondary school | –0.52 | –0.48 | –2.25* | 0.22 |

| (0.72) | (0.64) | (1.09) | (1.07) | |

| Intermediate secondary school | –0.45 | –0.35 | –0.94 | 0.92 |

| (0.57) | (0.52) | (0.81) | (0.89) | |

| Polytechnic secondary school | –1.73+ | –0.92 | –0.87 | –0.91 |

| (0.90) | (0.80) | (1.35) | (1.25) | |

| Qualification for applied upper secondary school | 0.26 | –0.00 | –1.28 | 0.35 |

| (0.81) | (0.77) | (1.16) | (1.38) | |

|

| ||||

| Marital status (ref. married/partnership) | ||||

| Divorced | –0.58 | 0.68 | 0.43 | –1.70 |

| (0.75) | (0.80) | (1.09) | (1.25) | |

| Widowed | 1.41 | 1.75+ | –0.27 | –2.28 |

| (0.98) | (0.98) | (1.58) | (1.85) | |

| Single | –0.47 | 0.11 | –2.29+ | –1.76 |

| (0.88) | (0.83) | (1.31) | (1.27) | |

|

| ||||

| Living situation (ref. living alone in private household) | ||||

| Living with others in private household | –0.15 | 0.08 | –0.61 | –1.31 |

| (0.70) | (0.68) | (0.93) | (1.18) | |

| Living in assisted living, retirement home or nursing home | –3.87** | –1.87 | 6.68+ | –10.49*** |

| (1.33) | (1.24) | (3.79) | (2.03) | |

|

| ||||

| Children in the household (ref. no) | ||||

| Yes, children ≤13 years | –0.18 | –0.07 | –0.08 | 0.65 |

| (0.77) | (0.74) | (1.17) | (1.35) | |

| Yes, children between 14 and 18 years | 1.23+ | 0.73 | –0.16 | 1.95* |

| (0.71) | (0.65) | (1.03) | (0.99) | |

|

| ||||

| Employment status (ref. employed [full-time]) | ||||

| Employed (part-time) | –1.04+ | –0.77 | 0.98 | –0.59 |

| (0.60) | (0.60) | (0.86) | (0.98) | |

| Marginally employed | –1.60+ | –2.07* | 4.02* | –5.05** |

| (0.89) | (0.94) | (1.97) | (1.69) | |

| Retired | –0.42 | –0.54 | 2.02+ | –1.16 |

| (0.90) | (0.88) | (1.18) | (1.29) | |

| Unemployed | 1.17 | 0.99 | 0.41 | –1.74 |

| (0.96) | (0.86) | (1.21) | (1.37) | |

|

| ||||

| Monthly household net income1 | –0.24* | 0.04 | 0.36* | –0.20 |

| (0.09) | (0.09) | (0.14) | (0.15) | |

|

| ||||

| Chronic physical illnesses | 0.85*** | 0.78*** | –0.58* | 0.51 + |

| (0.20) | (0.19) | (0.27) | (0.28) | |

|

| ||||

| Self-rated health | –1 33*** | –0.85** | 2 29*** | –1.06* |

| (0.35) | (0.31) | (0.41) | (0.49) | |

|

| ||||

| Caregiving time, h/week | –0.01 | 0.00 | 0.03 | –0.01 |

| (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.02) | (0.03) | |

|

| ||||

| Caregiving task − personal hygiene (ref. no) | 0.99 | –0.11 | –1.58+ | 3 74*** |

| (0.65) | (0.56) | (0.95) | (1.09) | |

|

| ||||

| Caregiving task − dressing (ref. no) | –0.33 | –0.01 | 0.52 | –0.79 |

| (0.68) | (0.63) | (0.92) | (1.14) | |

|

| ||||

| Caregiving task − feeding (ref. no) | 0.35 | –0.05 | 0.92 | 1.69* |

| (0.48) | (0.44) | (0.73) | (0.82) | |

|

| ||||

| Caregiving task − household help (ref. no) | 0.77 | 1.05* | –1.29+ | 1.80+ |

| (0.51) | (0.50) | (0.75) | (0.95) | |

|

| ||||

| Caregiving task − supervision (ref. no) | 0.23 | 0.46 | –1.04 | 2.71** |

| (0.56) | (0.55) | (0.88) | (0.97) | |

|

| ||||

| Caregiving task − transportation (ref. no) | 0.16 | 0.42 | 0.70 | 1.05 |

| (0.53) | (0.50) | (0.71) | (0.80) | |

|

| ||||

| Caregiving task − medication intake (ref. no) | –0.36 | 0.19 | –0.24 | 1.55 |

| (0.58) | (0.56) | (0.85) | (0.95) | |

|

| ||||

| Caregiving task − help with financial matters (ref. no) | 0.60 | –0.14 | –0.64 | 2.15** |

| (0.48) | (0.46) | (0.66) | (0.73) | |

|

| ||||

| Constant | 13.92*** | 5.77+ | 32 73*** | 2.47 |

| (3.69) | (3.44) | (5.19) | (5.61) | |

|

| ||||

| Observations | 337 | 348 | 317 | 338 |

|

| ||||

| R 2 | 0.41 | 0.33 | 0.39 | 0.43 |

OLS regression analyses were conducted, unstandardized beta coefficients are given with robust standard errors in parentheses; listwise deletion was used for missing values. OLS, Ordinary Least Squares. Level of significance: *** p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01, * p < 0.05, + p < 0.10. 1 Monthly household net income was assessed with 13 consecutive categories (e.g., <500 EUR, 500 EUR to <1.000 EUR, 1,000 EUR to <1.500 EUR, 1.500 EUR to <2.000 EUR) and is treated as a continuous variable in the analyses of this study.

Fig. 1.

Predictive margins (with 95% CI) for anxiety symptoms and the interaction effect between gender and perceived danger to their care recipients.

Fig. 2.

Predictive margins (with 95% CI) for anxiety symptoms and the interaction effect between gender and perceived danger for themselves.

Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic and the pandemic countermeasures have brought changes in various areas of daily life and informal caregivers seem to have been impacted more than non-caregivers (e.g., [5, 6]). However, not much research has compared male and female caregivers in their mental health, quality of life, and caregiver burden during the pandemic. In particular, research in Germany is lacking, and international studies have often used only convenience samples, non-validated instruments, have not compared both groups, and have all been conducted during the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, this study adds to current research by investigating a representative, population-based sample of caregivers in Germany with validated instruments during the second wave of the pandemic.

Our findings indicate that female caregivers experienced poorer mental health in terms of higher anxiety symptoms and poorer quality of life, compared to male caregivers. Adding pandemic indicators to the models did not change the results. In view of the large number of changes to daily life due to the pandemic, a reduction of the gender gap in family tasks, i.e., childcare and domestic tasks, has been indicated [27, 48, 49]. Changes in the gender gap regarding health and wellbeing among informal caregivers could therefore have occurred as well. However, our findings mostly confirm research from before the pandemic in terms of findings of poorer mental health (anxiety symptoms) and quality of life among female caregivers [12, 15, 16, 18, 19, 20, 21]. This adds to further findings regarding the prevalence of informal caregiving, with increases seen especially in the proportion of women providing care during the pandemic [31, 50]. Thus, the pre-pandemic gender gap in informal caregiving seemed to have remained. The descriptive results also indicated gender differences in employment; for example, more male caregivers were full-time employed, while more female caregivers were part-time employed. This may be mirrored in the performance of care tasks and care time. Since we controlled for all sociodemographic variables, these should not bias our results. Thus, our findings show, even when controlling for sociodemographic factors, gender differences remained significant with women experiencing poorer psychosocial health and wellbeing.

Previous research from during the pandemic, which came primarily from international studies, was less consistent. Our findings add to results from studies from China [28], Italy [29], the USA [5], the UK [33], and Serbia [32], which also found poorer mental health among female caregivers. While Klaus and Ehrlich [31] only provide descriptive results, their findings are confirmed by our results. Yet, Whitley et al. [33] found gender differences only at the very beginning of the pandemic and Todorovic et al. [32] found no significant differences, while our results indicate a significant gender difference in the second wave during the pandemic. Regarding the findings from Todorovic et al. [32], these differences in results may be due to their study not accounting for confounders and analyzing a small convenience sample. Moreover, gender differences in mental health may only become apparent during a pandemic wave. Further (longitudinal) research during the different stages of the pandemic is needed to test this further.

However, the findings of our fully adjusted models do not confirm previous findings regarding differences in depressive symptoms and burden [13, 14, 16, 17, 51]. Gender differences in these outcomes were only found in our partially adjusted models but not found when accounting for aspects of the care performance, i.e., care time and care tasks. This emphasizes the importance of accounting for confounders. The results can be seen as an indication that gender differences in these outcomes may be (mostly) due to differences in the care time and care tasks that were provided by women and men, i.e., the differences depended on the extent and type of care performance. Changes in these variables during the pandemic may account for finding a reduced gender gap in burden during the pandemic in other research as well, though this has not been analyzed [34]. While our descriptive results showed no significant gender differences in the caregiving time, women provided slightly more care. Also, significantly more women provided help with personal hygiene, dressing, and household tasks. This is in line with previous findings [12] and supports our assumption regarding the importance of the caregiving performance for gender differences in health outcomes.

We also added perceived impairment and danger posed by the pandemic as confounders to the models, which may have accounted for gender differences during the pandemic. The results remained virtually unchanged. However, when added as moderators, the perception of danger significantly moderated the gender differences in anxiety symptoms. Thus, differences in anxiety levels between men and women were linked to the level of perceived danger. Regarding the perceived level of danger to themselves, male and female caregivers had similar levels of anxiety when their perceived level of danger was low. However, with increasing perceived danger to themselves female caregivers' anxiety levels increased beyond the level of male caregivers. Thus, worrying about becoming ill themselves seems to be a central factor for female caregivers during the pandemic with respect to their anxiety levels. This may be due to female caregivers worrying about the effect that being ill may have on their caregiving duties, as has been reported in previous research [52]. Considering that the majority of (main) informal caregivers are women [10], this worry is well-founded. For men, instead, worrying about their care recipient contributed to their anxiety levels, while women already had higher levels of anxiety independent of the perceived danger for the care recipient.

Limitations, Further Research Recommendations, and Strengths

The study has some limitations. A cross-sectional study design was used, thus, changes of the gender gap in informal caregiving over time could not be analyzed. Longitudinal research is required to investigate this. Longitudinal research that analyzes the development from before and throughout the pandemic is also needed in addition and could further extend our findings.

The response rate for our survey was 52.97% with 199 dropouts. Reasons for dropout or nonresponse are not known. An online survey was conducted, which could result in an offline affinity bias. In particular caregivers of older age (e.g., 80 years and older) may be underrepresented due to this. However, we expect this bias to be reduced in this study because our sample was recruited offline via phone from a representative sample. Thus, the sample can still be seen as representative for informal caregivers aged ≥40 years of age in Germany. Further research on a younger group of informal caregivers would also be of interest. Our sample included only individuals aged 40 years and older, since the majority of caregivers can be found after this age cut-off [7, 10, 11]. Still, the exclusion of younger caregivers may be the reason that over 75% of our sample had no children at home. This younger group may also show gender differences, as women have commonly been more involved in caring for children before and during the pandemic [53, 54, 55]. Caring for children in addition to caring for older adults can thus be expected to add to the burden of female caregivers in particular. Further research on this during the pandemic would be of interest.

The study also has various advantages. A representative sample was studied with validated and reliable instruments. Moreover, the study was conducted during the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in Germany, which, to date, had the highest death rates due to COVID-19 [35], and therefore allows us to draw conclusions on health and wellbeing of informal caregivers during the worst phase of the pandemic. Also, it is one of the first studies analyzing gender differences in health and wellbeing of informal caregivers in Germany during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Conclusion and Recommendations

This study is one of the first to provide insight into health, wellbeing, and caregiving burden of male compared to female informal caregivers during the COVID-19 pandemic in Germany. It adds to existing research by investigating a representative, population-based sample of informal caregivers using validated instruments during the second wave of the pandemic (winter 2020) in Germany. The results of the comparison between both groups of informal caregivers point out that female caregivers were particularly vulnerable during the pandemic regarding their quality of life and mental health. Thus, despite the changes in work and family life during the pandemic, the results of this representative study from Germany show that during one of the worst phases of the COVID-19 pandemic it was still female caregivers who were affected worse than male caregivers. This adds to other findings, which indicated that women in particular have been affected negatively by the pandemic [4, 31]. It also highlights again the general and mental burden associated with the often invisible care work for older adults that is primarily provided by women all over the world [7, 10, 11]. The findings may be extended to countries with a similar care system and management of the pandemic. Still, further research on the gender care gap during the pandemic in other countries, with suitable methodology, is recommended, since the management of the pandemic and the care systems greatly differed across countries.

Our findings further emphasize the need for the recognition and acknowledgment of the gender care gap that became again apparent during the COVID-19 pandemic. Research and policy in Germany should therefore focus more and in particular on female caregivers and provide gender-specific support to reduce the gender gap in health and wellbeing among informal caregivers. Considering previous findings, this applies not only during a health crisis but beyond the pandemic. Moreover, our study further extends previous research by indicating that the extent of, and the tasks that are performed during caregiving, could be of relevance in this context. For example, reducing caregiving time and providing more support, in particular with personal hygiene, may be helpful to prevent these negative outcomes for female caregivers. Also, redistribution of care tasks within the caregiving network, including other informal and formal caregivers, is recommended. These findings are a good basis for future research on underlying mechanisms of the gender gap in informal care, which is urgently recommended. The findings should also be used to inform future care policy decisions and provide a basis for adequate support that is gender specific, both during a health crisis and beyond the current pandemic.

Lastly, our findings on the moderating effect of the perceived danger posed by the pandemic indicate that providing information, support, and adequate pandemic measures that help caregivers to protect their care recipients and themselves (from infection and pandemic impairments) is strongly recommended. This could help lower anxiety levels of both, male and female caregivers. It is particularly relevant for female caregivers, who had higher levels of anxiety in general.

Interventions based on these findings, and informed by what was learned during the pandemic about changes in task distribution in work and family life and its consequences for health and wellbeing, could help to achieve a more equal task distribution between men and women, and thereby help end gender differences and improve health and wellbeing for both groups.

Statement of Ethics

The Local Psychological Ethics Committee of the Center for Psychosocial Medicine of the University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf approved the study (Ethics approval number: LPEK-0239). All participants gave written informed consent.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Sources

This study was funded by the research funding program for early career researchers (FFM) of the Faculty of Medicine, Universität Hamburg.

Author Contributions

Larissa Zwar contributed to conception, design, visualization and analysis of the data, and drafted the manuscript. Hans-Helmut König and André Hajek contributed to the conception and design and revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

The data from this study are available upon reasonable request from the authors. Interested parties may contact the corresponding author Larissa Zwar, Department of Health Economics and Health Services Research, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, 20246 Hamburg, Germany (E-mail: l.zwar@uke.de).

Appendix 1

Description of Confounders

Sociodemographic and health factors were included as possible confounders into all models. This included age, education (highest educational degree: without school leaving qualification, currently in school training, lower secondary school, intermediate secondary school, polytechnic secondary school, qualification for applied upper secondary school, upper secondary school), marital status (married/partnership, divorced, widowed, single), living situation (living alone in private home, living together with others in private home, living in assisted living, nursing or retirement home), having children in one's household (no; yes, children aged <13 years; yes, children aged ≥14 and ≤18 years), employment status (full-time employed, part-time employed, marginally employed, retired, unemployed), and income (monthly household net income in Euro, assessed with 13 categories: <500 EUR, 500 EUR to <1.000 EUR, 1,000 EUR to <1.500 EUR, 1.500 EUR to <2.000 EUR, 2.000 EUR to <2.500 EUR, 2.500 EUR to <3.000 EUR, 3.000 EUR to <3.500 EUR, 3.500 EUR to <4.000 EUR, 4.000 EUR to <4.500 EUR, 4.500 EUR to <5.000 EUR, 5.000 EUR to <6.000 EUR, 6.000 EUR to <8.000 EUR, ≥8.000 EUR). Health was assessed in terms of (1) self-rated health (single-item question, Range:1–5, higher values indicate better health), and (2) the number of chronic physical illnesses {sum score based on a list of 13 items (cardiovascular and circulatory diseases; bad circulation; joint, bone, spinal or back problems; respiratory diseases; stomach or intestinal problems; cancer; sugar/diabetes; gall bladder, liver or kidney problems; bladder problems; sleep problems [insomnia]; eye/visual impairments; ear/hearing impairments; neurological diseases; individuals with other problems [4.29% of all informal caregivers] were excluded), Range: 0–13, higher values indicate worse health}.

References

- 1.Benke C, Autenrieth LK, Asselmann E, Pané-Farré CA. Lockdown, quarantine measures, and social distancing: associations with depression, anxiety and distress at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic among adults from Germany. Psychiatry Res. 2020 Nov;293:113462. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holman EA, Thompson RR, Garfin DR, Silver RC. The unfolding COVID-19 pandemic: a probability-based, nationally representative study of mental health in the United States. Sci Adv. 2020;6((42)):eabd5390. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abd5390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vindegaard N, Benros ME. COVID-19 pandemic and mental health consequences: systematic review of the current evidence. Brain Behav Immun. 2020 Oct;89:531–42. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xiong J, Lipsitz O, Nasri F, Lui LMW, Gill H, Phan L, et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2020 Dec 1;277:55–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beach SR, Schulz R, Donovan H, Rosland A-M. Family caregiving during the COVID-19 pandemic. Gerontologist. 2021;61((5)):650–60. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnab049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hughes MC, Liu Y, Baumbach A. Impact of COVID-19 on the health and well-being of informal caregivers of people with dementia: a rapid systematic review. Gerontol Geriatr Med. 2021 Jan–Dec;7:23337214211020164. doi: 10.1177/23337214211020164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Verbakel E, Tamlagsrønning S, Winstone L, Fjær EL, Eikemo TA. Informal care in Europe: findings from the European Social Survey (2014) special module on the social determinants of health. Eur J Public Health. 2017 Feb 1;27((Suppl_1)):90–5. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckw229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Federal Ministry of Justice . Social code book XI. Berlin: Federal Ministry of Justice; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Statistisches Bundesamt Pflegestatistik 2019: pflege im rahmen der pflegeversicherung − deutschlandergebnisse [Internet] 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rothgang H, Müller R. Pflegereport 2018: schriftenreihe zur gesundheitsanalyse. Berlin: BARMER; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Alliance for Caregiving, AARP Public Policy Institute Caregiving in the U.S.: 2020 report. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pinquart M, Sörensen S. Gender differences in caregiver stressors, social resources, and health: an updated meta-analysis. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2006;61((1)):P33–45. doi: 10.1093/geronb/61.1.p33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Swinkels J, Tilburg T, Verbakel E, Broese van Groenou M. Explaining the gender gap in the caregiving burden of partner caregivers. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2017;74((2)):309–17. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbx036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pillemer S, Davis J, Tremont G. Gender effects on components of burden and depression among dementia caregivers. Aging Ment Health. 2018 Sep 2;22((9)):1156–1. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2017.1337718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bom J, Bakx P, Schut F, van Doorslaer E. The impact of informal caregiving for older adults on the health of various types of caregivers: a systematic review. Gerontologist. 2019 Sep 17;59((5)):e629–42. doi: 10.1093/geront/gny137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Collins RN, Kishita N. Prevalence of depression and burden among informal caregivers of people with dementia: a meta-analysis. Ageing Soc. 2020;40((11)):2355–92. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Connors MH, Seeher K, Teixeira-Pinto A, Woodward M, Ames D, Brodaty H. Dementia and caregiver burden: a three-year longitudinal study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2020 Feb;35((2)):250–8. doi: 10.1002/gps.5244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sharma N, Chakrabarti S, Grover S. Gender differences in caregiving among family: caregivers of people with mental illnesses. World J Psychiatry. 2016 Mar 22;6((1)):7–17. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v6.i1.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xiong C, Biscardi M, Astell A, Nalder E, Cameron JI, Mihailidis A, et al. Sex and gender differences in caregiving burden experienced by family caregivers of persons with dementia: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2020;15((4)):e0231848. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0231848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.del Río Lozano M, del Mar García-Calvente M, Calle-Romero J, Machón-Sobrado M, Larrañaga-Padilla I. Health-related quality of life in Spanish informal caregivers: gender differences and support received. Qual Life Res. 2017;26((12)):3227–38. doi: 10.1007/s11136-017-1678-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frias CE, Cabrera E, Zabalegui A. Informal caregivers' roles in dementia: the impact on their quality of life. Life. 2020;10((11)):251. doi: 10.3390/life10110251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heger D. The mental health of children providing care to their elderly parent. Health Econ. 2017;26((12)):1617–29. doi: 10.1002/hec.3457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zwar L, König HH, Hajek A. Consequences of different types of informal caregiving for mental, self-rated, and physical health: longitudinal findings from the German ageing survey. Qual Life Res. 2018 Oct;27((10)):2667–79. doi: 10.1007/s11136-018-1926-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zwar L, König HH, Hajek A. The impact of different types of informal caregiving on cognitive functioning of older caregivers: evidence from a longitudinal, population-based study in Germany. Soc Sci Med. 2018 Oct;214:12–9. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.07.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bundesregierung D. Telefonkonferenz der bundeskanzlerin mit den regierungschefinnen und regierungschefs der länder am 13. 2020 Dec [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lorenz-Dant K. Germany and the COVID-19 long-term care situation. Country report in LTCcovid.org, International long term care policy network. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bundesamt S. Kapitel 14: auswirkungen der coronapandemie. Daten report 2021. 2021 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li Q, Zhang H, Zhang M, Li T, Ma W, An C, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of anxiety, depression, and sleep problems among caregivers of people living with neurocognitive disorders during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front Psychiatry. 2021;11:1516. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.590343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zucca M, Isella V, Lorenzo RD, Marra C, Cagnin A, Cupidi C, et al. Being the family caregiver of a patient with dementia during the coronavirus disease 2019 lockdown. Front Aging Neurosci. 2021 Apr 20;13((132)):653533. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2021.653533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rodrigues R, Simmons C, Schmidt AE, Steiber N. Care in times of COVID-19: the impact of the pandemic on informal caregiving in Austria. Eur J Ageing. 2021;18((2)):195–205. doi: 10.1007/s10433-021-00611-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Klaus D, Ehrlich U. Corona-Krise = Krise der angehörigenpflege? Zur veränderten situation und den gesundheitsrisiken der informell unterstützungs- und pflegeleistenden in zeiten der pandemie. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Todorovic N, Vracevic M, Rajovic N, Pavlovic V, Madzarevic P, Cumic J, et al. Quality of life of informal caregivers behind the scene of the COVID-19 epidemic in Serbia. Medicina. 2020 Nov 26;56((12)):647. doi: 10.3390/medicina56120647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Whitley E, Reeve K, Benzeval M. Tracking the mental health of home-carers during the first COVID-19 national lockdown: evidence from a nationally representative UK survey. Psychol Med. 2021:1–10. doi: 10.1017/S0033291721002555. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Raiber K, Verbakel E. Are the gender gaps in informal caregiving intensity and burden closing due to the COVID-19 pandemic? Evidence from the Netherlands. Gend Work Organ. 2021 Jul 5; doi: 10.1111/gwao.12725. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.World Health Organization WHO coronavirus disease (COVID-19) dashboard: Germany. 2021 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bundesregierung D. Videoschaltkonferenz der bundeskanzlerin mit den regierungschefinnen und regierungschefs der länder am 19. Januar 2021. 2021 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bundesregierung D. Videoschaltkonferenz der bundeskanzlerin mit den regierungschefinnen und regierungschefs der länder am 10. Februar 2021. 2021 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bundesregierung D. Videoschaltkonferenz der bundeskanzlerin mit den regierungschefinnen und regierungschefs der länder am 3. März 2021. 2021 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Löwe B, Spitzer R, Zipfel S, Herzog W. Gesundheitsfragebogen für patienten (PHQ-D). Komplettversion und kurzform. Testmappe mit manual, fragebögen, schablonen. 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schuler M, Strohmayer M, Mühlig S, Schwaighofer B, Wittmann M, Faller H, et al. Assessment of depression before and after inpatient rehabilitation in COPD patients: psychometric properties of the German version of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9/PHQ-2) J Affect Disord. 2018;232:268–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.02.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166((10)):1092–7. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Löwe B, Decker O, Müller S, Brähler E, Schellberg D, Herzog W, et al. Validation and standardization of the generalized anxiety disorder screener (GAD-7) in the general population. Med Care. 2008;46((3)):266–74. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318160d093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Graessel E, Berth H, Lichte T, Grau H. Subjective caregiver burden: validity of the 10-item short version of the burden scale for family caregivers BSFC-s. BMC Geriatr. 2014 Feb 20;14((1)):23. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-14-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pendergrass A, Malnis C, Graf U, Engel S, Graessel E. Screening for caregivers at risk: extended validation of the short version of the burden scale for family caregivers (BSFC-s) with a valid classification system for caregivers caring for an older person at home. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018 Apr 2;18((1)):229. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-3047-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hyde M, Wiggins RD, Higgs P, Blane DB. A measure of quality of life in early old age: the theory, development and properties of a needs satisfaction model (CASP-19) Aging Ment Health. 2003;7((3)):186–94. doi: 10.1080/1360786031000101157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Von Dem Knesebeck O, Wahrendorf M, Hyde M, Siegrist J. Socio-economic position and quality of life among older people in 10 European countries: results of the SHARE study. Ageing Soc. 2007;27((2)):269–84. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Börsch-Supan A, Brugiavini A, Jürges H, Kapteyn A, Mackenbach J, Siegrist J, et al. First results from the survey of health, ageing and retirement in Europe (2004–2007). Starting the longitudinal dimension. Mannheim: Mannheim Research Institute for the Economics of Aging (MEA); 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Craig L, Churchill B. Dual-earner parent couples' work and care during COVID-19. Gend Work Organ. 2021;28:66–77. doi: 10.1111/gwao.12497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yerkes MA, André SCH, Besamusca JW, Kruyen PM, Remery C, van der Zwan R, et al. Intelligent' lockdown, intelligent effects? Results from a survey on gender (in)equality in paid work, the division of childcare and household work, and quality of life among parents in the Netherlands during the Covid-19 lockdown. PLoS One. 2020;15((11)):e0242249. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0242249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sugawara S, Nakamura J. Long-term care at home and female work during the COVID-19 pandemic. Health Policy. 2021 Jul;125((7)):859–68. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2021.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yee JL, Schulz R. Gender differences in psychiatric morbidity among family caregivers: a review and analysis. Gerontologist. 2000;40((2)):147–64. doi: 10.1093/geront/40.2.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Eurocarers/IRCCS-INRCA Impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on informal carers across Europe − final report. Brussels/Ancona. 2021 [Google Scholar]

- 53.Johnston RM, Mohammed A, Van Der Linden C. Evidence of exacerbated gender inequality in child care obligations in Canada and Australia during the COVID-19 pandemic. Pol Gen. 2020;16((4)):1131–41. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sevilla A, Smith S. Baby steps: the gender division of childcare during the COVID-19 pandemic. Oxf Rev Econ Policy. 2020;36((Suppl_1)):S169–86. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zamarro G, Prados MJ. Gender differences in couples' division of childcare, work and mental health during COVID-19. Rev Econ Househ. 2021 Mar;19((1)):11–40. doi: 10.1007/s11150-020-09534-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data from this study are available upon reasonable request from the authors. Interested parties may contact the corresponding author Larissa Zwar, Department of Health Economics and Health Services Research, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, 20246 Hamburg, Germany (E-mail: l.zwar@uke.de).