Abstract

Effective leaders in healthcare settings create a motivating work environment, initiate changes in practice, and facilitate interdisciplinary collaboration to advance patient-centered care. Health professionals in cancer education need leadership development to meet the continued rise in cancer cases and to keep up with the rapid biomedical and technological advances in global cancer care. In addition, leadership development in cancer education supports interprofessional collaboration, optimizes patient engagement, and provides mentorship opportunities necessary for career advancement and skill development. The identified benefits from leadership development in cancer education led to the creation of an interactive pilot leadership workshop titled “Essential Skills in Cancer Education: Leadership, Leading, and Influencing Change in Cancer Education,” held at the International Cancer Education Conference in October 2020. The workshop was led by global leaders in cancer education and utilized lectures, mentorship opportunities, interactive case studies, and individual learning projects to develop leadership skills in multidisciplinary oncology professionals. Fifteen attendees from diverse educational backgrounds and levels of experience participated in the virtual leadership workshop and mentorship program. Following the workshop, participants reported an increase in knowledge regarding how to use different leadership styles, initiate changes in practice, and apply leadership skills in their career development and at their institutions. The feedback received from participants through post-workshop evaluations was overall positive and demonstrated an interest for more leadership development opportunities in cancer education. This pilot workshop shows that leadership is a valuable and teachable skill that will benefit both healthcare professionals and patients in the field of cancer education.

Keywords: Leadership, Interdisciplinary, Continuing education, Leadership workshop, Mentorship, Cancer education

Introduction

Healthcare today is practiced in interdisciplinary teams that must make administrative and clinical decisions to optimize patient care in a rapidly changing environment. Effective leadership skills are important in this setting to identify and confront challenges with creative solutions, and foresee problems that could hinder the delivery of healthcare [1, 2]. Investigations of leadership in healthcare have found strong associations between effective leadership and productive work environments, positive patient outcomes, and an increase in the safety and success of care provided [3, 4]. Leadership encompasses a problem-solving mindset, in addition to qualities such as communicating clearly, establishing direction, and inspiring change, which are necessary in interprofessional care and collaboration [5, 6].

Leadership is a teachable skill that can be taught through mentorship by experienced leaders and leadership development programs. One practical example of the utility of leadership development is that by cultivating an understanding of leadership styles, they can be implemented into ones’ practice. Analyses of leadership development programs in healthcare demonstrated that such programs can be used to advance the quality and efficiency of healthcare by improving a professional’s ability to perform their job, providing education and training specific to the needs of the organization, and developing a strategic focus in employees to initiate changes in practice to meet relevant goals (e.g., quality of care, patient satisfaction, reducing expenses) [7]. A systematic review by Frich et al. (2015) looked at 45 leadership development programs in healthcare and found that the majority of programs focused only on physicians, thus limiting opportunities for team-based leadership and interdisciplinary communication with other professionals. Additionally, the few programs that utilized diverse teaching tools (e.g., mentorship, projects, feedback) were more effective in developing leadership skills in individuals that led to positive impacts at their institutions [8].

Cancer education is an area that would benefit from leadership development opportunities due to the inherent nature of team-based interdisciplinary practice in oncology. Members of an interdisciplinary healthcare team have unique responsibilities related to their role. A noted barrier to effective interdisciplinary collaboration is the physician-dominant culture and professional hierarchy [9]. One study found that tasks executed by physicians, such as completing investigations, pursuing diagnoses, and discussing treatments, tended to take priority over supportive care provided by non-physician members of the team [10]. This hierarchy marginalizes the role of non-physician healthcare professionals, when it is clear that collaborative care is beneficial for cancer patients. Emphasizing care from non-physician members has been shown to enhance quality of life among palliative cancer patients, reduce hospital admissions, and improve patient satisfaction [11–13]. Effective leadership facilitates interprofessional collaboration, and leaders can improve their competency in this area by increasing interactions with professionals from other disciplines, to create a more productive workplace that fosters communication, respect, and teamwork [14–16].

Patient engagement is another hallmark of cancer education, as the patient’s treatment outcome and experiences through illness and recovery are important measures that reflect the quality of care provided. For example, including cancer patients in cancer research can ensure patient-relevant endpoints, allow advocacy on behalf of the population being studied, and add urgency to the research by emphasizing lived patient experiences [17]. Furthermore, engaging patients in shared decision making better reflects patient needs and preferences related to treatment and end-of-life. This is associated with greater patient satisfaction and improved patient outcomes [18, 19]. Emphasizing leadership in cancer education has the potential to inspire professionals to consider actionable ways a patient’s experience can be improved and equip professionals with the skills to initiate such changes in practice [20, 21].

Cancer education is also holistic—it relies on both scholarship and clinical reflections to disseminate information that furthers the learning of healthcare staff and allied professionals. Like in many facets of healthcare, disparities in cancer outcomes exist between low-, middle-, and high-income countries [22]. Leadership development opportunities must be accessible and inclusive to providers from across the globe, and promote the sharing of knowledge and resources. Leadership development would benefit from opportunities that facilitate networking and encourage scholarship initiatives to further support the training of leaders in cancer care internationally, and improve care and access to treatment for cancer patients globally.

The authors of this paper designed a leadership development program targeted to healthcare workers in cancer education and conducted a pilot session, titled “Essential Skills in Cancer Education: Leadership, Leading, and Influencing Change in Cancer Education,” at the International Cancer Education Conference (ICEC) in October 2020. Development of the leadership program emphasized skills necessary in cancer care, which may be transferable to other areas of medicine, such as interdisciplinary teamwork, patient engagement, quality improvement, and scholarship output. Through delivery of specific workshop objectives and provision of mentorship by experienced cancer care leaders, the workshop aimed to build confidence and develop core leadership skills for interprofessional healthcare providers in the field of oncology. The overall goals of the workshop were to enable participants to (1) translate the principles of leadership into action; (2) utilize change, networking, and consensus building to set, align, and achieve goals in an interprofessional setting; and (3) engage the participants in leadership in cancer education and inspire initiative for change.

Methods

Needs Assessment

The needs assessment prior to the development of the educational interactive workshop was conducted in three steps. First, a focus group consisting of leaders in cancer education met at the International Cancer Education Conference in 2019. Workshop objectives were developed and details about workshop delivery, audience, and content were discussed. Second, a literature review was conducted to identify gaps in leadership development and determine what teaching tools and program content is most effective in leadership development programs. The information obtained from this review was used to guide the curriculum for the workshop. Third, presenters were selected and continued to communicate online to discuss workshop planning and ensure that objectives were met in the program curriculum. The workshop was designed to meet the criteria for accreditation with the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons, American Medical Association, and American Nursing Credentialing Center.

Program Content

The literature review conducted during the needs assessment guided curriculum development. Current literature recognizes that leadership development programs conducted with a variety of teaching modalities were more effective in teaching leadership skills to participants [6]. To maximize learning, the workshop was designed to include lectures/seminars for foundational content, case-based activities, networking sessions, individual learning projects, presentations by participants, and mentorship.

The workshop was a 1-day event, divided into two halves across the morning and afternoon. It was delivered over a video-conferencing platform. The morning half of the workshop was comprised of foundational learning, designed to introduce participants to theories underpinning leadership and its utility in healthcare. Topics covered include leadership styles and how to use them in different situations, engaging in leadership in culturally diverse settings, and implementing changes in practice to optimize patient care. From the topics listed above, international cancer education leaders presented initiatives they have led at their own institutions, which were specifically linked to leadership styles (e.g., transactional, transformational, shared/team, laissez-faire, or compassionate) and demonstrated examples of leading successful change. Each presentation had specific objectives and was followed by a question and answer period with the presenters (Table 1). The full workshop curriculum spanned several topics regarding leadership in cancer education.

Table 1.

Leadership workshop curriculum topics and objectives

| Curriculum Topic | Objectives | Format |

|---|---|---|

| Morning half of workshop—2 h | ||

| Leading and influencing change in cancer education program |

Describe the leadership program elements and participant’s roles and responsibilities Discuss the different leadership styles and how equity, diversity and inclusion are integrated into leadership practice including gaps |

Lecture, Q&A, Discussion |

| Dynamic leadership in the challenging climate of medicine and health professions |

Describe the different leadership styles and how they are used in different situations Understand the different approaches in leadership styles and the impact, (including advantages and disadvantages) of compassionate leadership How compassionate leadership is integrated into the leadership style |

Lecture, Q&A, Discussion |

| Leadership in cancer education at Ramban Academic Hospital—Cultural diversity in leadership |

Analyze different leadership structures in an academic setting Demonstrate the importance of cultural sensitivity in leadership and how to engage in leadership in culturally diverse settings |

Lecture, Q + A, Discussion |

| The surgical cancer patient: using credentialed skill-based course model to improve outcomes | Describe how change management can be implemented in practice for optimizing self-care of the complex surgical care patient | Lecture, Q + A, Discussion |

| Challenges and opportunities, change management in leading the Journal of Cancer Education | Identify challenges and opportunities in managing an organization | Lecture, Q + A, Discussion |

| Building successful cancer education & training programs in developing countries: King Hussein Cancer Center, Jordan successful experience |

Discuss capacity building challenges and opportunities Describe different leadership structures in an academic setting Demonstrate the importance of international and regional collaboration in cancer training and education |

Lecture, Q + A, Discussion |

| Afternoon half of workshop—2 h | ||

| Case studies and discussion |

Apply knowledge from the workshop in real-life scenarios Collaborate in interdisciplinary teams Knowledge sharing on how the participant would use a leadership style within a given scenario |

Group work, Discussion |

| Rapid fire presentation on individual leadership projects |

Develop productive and effective mentoring relationships Idea sharing on topics identified by participants in their own practice Engage in scholarly projects to develop leadership skills necessary for oncology professionals |

Individual presentations, mentorship, feedback |

| Conclusion and summary of presented topics |

Follow-up with mentors online to enhance scholarship output of the individual projects discussed at the course Touchpoints with mentor/mentee |

Q&A, reflection, mentorship, evaluations |

The afternoon half of the workshop focused on interactive learning opportunities and group discussion to actively engage participants with their mentors. Participants attended breakout sessions in small groups to consolidate and apply the leadership content learned by working through a provided case study. In the weeks prior to the workshop, participants had been instructed to prepare a presentation on a potential quality improvement project they could implement at their own institution. This was for a large-group session, in which participants were encouraged to present their ideas and receive feedback from the faculty and other attendees. Provision of faculty and peer feedback was incorporated to encourage further development of their ideas, inspire other participants to undertake their own projects, and foster project-based discussion between the interprofessional audience of the workshop. A mentorship program was arranged prior to the workshop and continued for 6 months post-workshop. Mentors, comprised of leaders and faculty in cancer education, were assigned and e-introduced to participants to foster communication and build upon individual projects and/or ideas that participants wanted to implement within their own institutions. Following the workshop, mentors were available to provide on-going support to help mentees initiate their individual projects and encourage scholarship output in the form of presentations or manuscript submissions to the Journal of Cancer Education or other peer-reviewed medical education journals.

Bringing together the foundational learning and interactive sessions, it was anticipated that by the end of the workshop attendees would be better able to describe different leadership styles and how they are used in different situations, define the steps needed to initiate changes in practice, address the challenges and communication gaps, develop productive mentoring relationships, and engage in scholarly projects to develop leadership skills necessary for oncology professionals.

Participants

To emphasize collaboration and address the lack of team-based interdisciplinary leadership courses noted in the literature, the target audience spanned the many professions involved within cancer care. The workshop was offered to radiation oncologists, medical oncologists, surgical oncologists, fellows and medical residents, oncology nurses, radiation therapists, and other allied health professionals in oncology who were interested in developing leadership skills within cancer education. Participants were recruited by advertising the workshop through the American Association of Cancer Education Society, the University of Toronto Radiation Oncology Department, and the University of Toronto Continuing Professional Development department.

Evaluations

A pre-workshop evaluation questionnaire was developed to survey participants about their current knowledge regarding leadership, prior mentorship and scholarship experience, and their expectations of the workshop and what they were hoping to gain by participating. Data was collected by asking participants to answer on a 5-point Likert scale or by responding to open-ended questions. The pre-workshop evaluation was conducted following enrollment of participants and its results were shared with the presenters so that the participant’s prior experience and goals could be taken into consideration when designing the curriculum. The post-workshop evaluation sought feedback from the participants about whether workshop objectives were met, what was learned, and suggested improvements for future workshop sessions.

Post-Workshop

The mentorship program continued 6-months following the workshop to support participants in implementing their individual learning projects and generating scholarship output. Workshop leads and presenters met following the workshop to discuss the post-workshop evaluations and continue the discussion surrounding leadership in cancer education. Participants continued to be engaged by workshop organizers via email to provide additional leadership advice and answer questions.

Results

Participants

Enrollment was capped to 15 participants, due to the virtual environment in which the workshop was held and to maximize engagement among participants. The participant list included an interdisciplinary group of participants with varying amounts of leadership experience in cancer education. The professional disciplines of the workshop attendees included four directors/associate directors of research and education, three professors/associate professors in medical education, three health educators, two researchers, one registered nurse, one doctoral candidate, and one medical student. One of the participants was from Peru and the rest were from across the USA.

Pre-Workshop Evaluations

Six out of fifteen participants completed a pre-workshop evaluation. Questions 1–3 of the pre-workshop evaluation asked participants to rate their current knowledge of leadership styles, familiarity with initiating changes in practice, and leadership in cancer education. The initial responses to these questions are available in Fig. 1, as well as comparison with how their knowledge base was different following the workshop. Questions 4–5 of the pre-workshop evaluation was intended to understand participant experience with mentorship and scholarship/research initiatives. It was found that all the participants who filled out the pre-workshop evaluation had mentors in their professional career, and 4 out of 6 had experience participating in educational scholarship at their institution. This information was helpful for the workshop leads in gauging participant comfort levels with the process of conducting a quality improvement or scholarship project, and therefore adequately providing support and emphasizing mentorship connections.

Fig. 1.

Comparing participant’s knowledge regarding different topics in leadership related to the workshop curriculum prior to and following completion of the workshop

Open-ended questions probing for participants’ expectations and what they hoped to gain from the workshop identified specific areas of interest, which were relayed to the presenters to shape the curriculum. Common themes included initiating change in practice, applying leadership styles in different situations, and developing leadership qualities. One participant specifically commented that they, “…hope to gain insight into different leadership styles and strategies to affect change at [their] institution.” An additional participant also said that they wanted to, “become a stronger leader within [their] organization and professional career” following the workshop. There is an interest in leadership development programs among cancer educators, as one participant expressed that they were, “grateful to attend and… learn that there is a community available for this specific type of scholarship and learning.” The responses to the pre-workshop evaluations were coalesced and can be found in the appendix of this article.

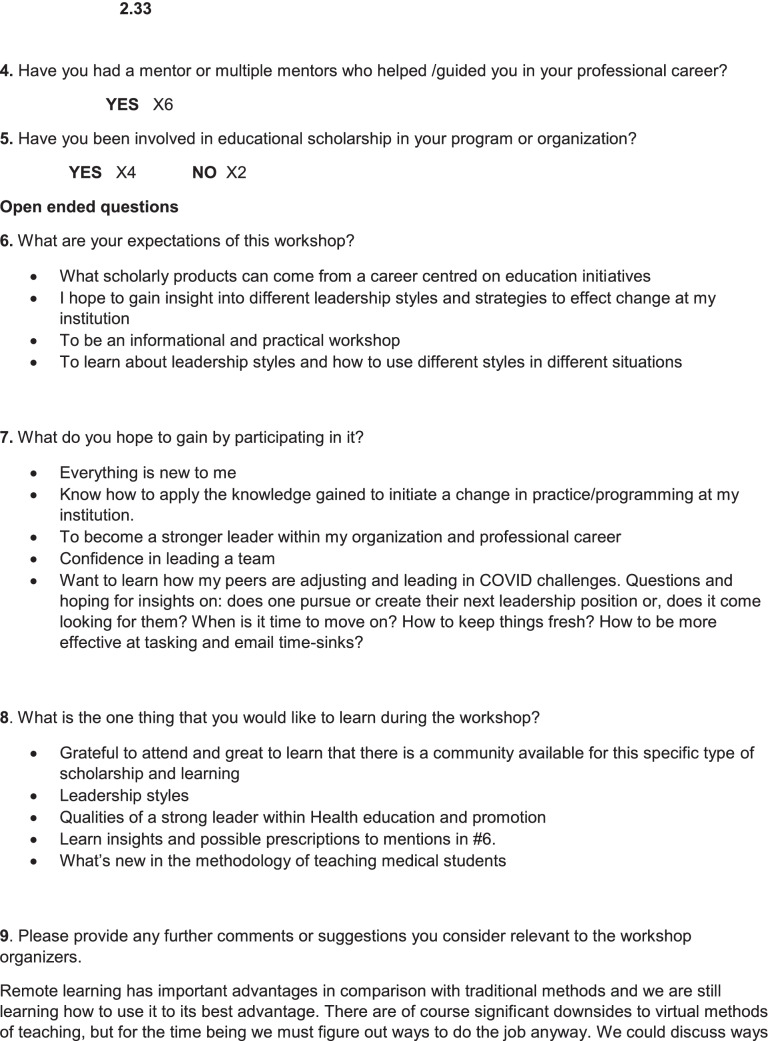

Post-Workshop Evaluations

Four out of fifteen participants completed a post-workshop evaluation. Results from the post-workshop evaluations demonstrated an increase in knowledge regarding all areas that were surveyed in the pre- and post-workshop evaluations (Fig. 1). When asked to rate their satisfaction with the leadership workshop, whether they felt the content was appropriate for their work, and the quality of the workshop materials, the response from the participants was overall positive (Fig. 2). This was further reflected within the post-workshop evaluations, in which participants recounted what was learned and how they plan to utilize this knowledge in future clinical practice and research. All responses indicated that they benefitted from learning about leadership styles and their applications, with one response affirming that, “the section… on the different leadership styles was most helpful.” Another comment, stated, “I will definitely think about my leadership style and how a different leadership style may help me initiate a change at my institution.” The emphasis and opportunity for mentorship in the workshop was also well received, with a comment in the post-workshop evaluation stating that, “mentoring throughout the span of one’s career would be a wonderful innovation in many workplaces.” When participants were asked how they will apply what they have learned in the workshop, the responses demonstrated that participants were critically thinking about how they can initiate changes in practice. One participant’s response to the question said, “[I will] be more intentional about choosing leadership styles based on the given situation [and] explore the possibility of partnerships between researchers and patients/providers.” This comment validates that the workshop was successful in promoting interdisciplinary collaboration. Another response to the question included, “[I will] understand the emotions of the team when initiating change and approach the project with a consistent and appropriate style,” which again reveals that participants left the leadership workshop mindful of how they can enhance collaboration in team-based settings. These comments and feedback solidify that the goals and objectives were met.

Fig. 2.

Feedback collected from participants on the post-workshop evaluations

Discussion

Developing leaders in cancer care is essential for the provision of care amid the rising worldwide burden of cancer. Competent leaders are able to set and achieve goals, build and motivate their team, and create productive work environments [23]. It is no longer tenable for clinicians to avoid recognizing the value of developing leadership skills. In cancer care especially, healthcare professionals require leadership skills to optimize the workflow of interdisciplinary teams for the benefit of patients [24]. Facilitating leadership development in cancer care will also enable better patient engagement, as the patient’s illness and recovery experiences can be used to guide necessary organizational changes that improve patient satisfaction and quality of care delivered. There is increasing recognition from the medical education community that changes are necessary to teach leadership skills to healthcare professionals and to implement culture change based on good clinical decision making and a patient-centered approach to care [25]. This leadership workshop held at the ICEC is an example of a successful pilot endeavor that was able to facilitate leadership skill development to an interdisciplinary group of participants with varying amounts of experience.

Responses to the pre- and post-workshop surveys confirmed that participants felt their knowledge regarding topics in leadership in cancer education increased following completion of the workshop. The answers to the open-ended questions and the feedback provided in post-workshop surveys show that participants were able to reflect on what they learned in the workshop and how to apply that knowledge in their careers in cancer education and at their institutions. Comparing this leadership workshop to ones that currently exist and have been discussed in the literature, the strengths of this workshop include the opportunities for attendees to actively participate. For example, diverse teaching modalities were used to engage participants and promote interactivity. This included discussions between participants and presenters, presentations by attendees on their individual projects where they could receive feedback, and the mentorship program meant to support participants in following-through on their individual projects and scholarship initiatives. This workshop demonstrates the many ways in which leadership can be taught and how leadership development programs can be tailored toward the needs of the participants.

A study by Graham (2020) interviewed cancer care professionals with less than 2 years of experience in their role and found that these new leaders experienced feelings of incompetence, isolation, and a lack of mentorship. The study also demonstrated an interest in structured programs for leadership skill development, especially from professionals newly starting their career [26]. Khan et al. (2016) corroborated similar findings in their study of leadership development in Canadian cancer programs. Through their survey of professionals in leadership roles at Canadian cancer centers, they found that respondents agree on four competencies of leadership: strategic planning, managing change, inspiring communication, and leading people. However, the cancer centers evaluated in their study did not support the development of future leaders, as fewer than 25% offered a formal avenue for leadership development. The study reiterated that leadership development programs are vital to train the next generation of leaders in cancer care [27]. Offering leadership development opportunities can help bridge these feelings of uncertainty with the teaching of core leadership theory that professionals can incorporate into their practice. In addition, both studies demonstrate the need for leadership development programs for early career professionals in oncology.

Mentorship, which the study by Graham (2020) also emphasized, was an aspect of the pilot leadership workshop that we encouraged participants to utilize. Mentorship by experienced leaders in cancer care permits transfer of knowledge, sharing of expertise, and helps early career professionals seek guidance from senior leaders [28]. What our leadership workshop did well was connect participants with qualified mentors prior to the workshop and allow them to initiate a mentor–mentee relationship, as participants discussed their quality improvement ideas in preparation for their presentations in the large group session. The intended purpose was that mentees would continue to communicate with their mentors following the workshop to implement their quality improvement projects. In addition, mentees were encouraged to leverage the experience of their mentors to seek advice regarding other aspects of their career as needed.

The leadership workshop was not without limitations, and areas for improvement have been identified for future sessions of the workshop. For one, while the mentorship program was successful in fostering communication between attendees and mentors prior to and during the workshop, follow-up revealed that most participants did not implement their quality improvement project nor kept in contact with their mentors long-term. Participants revealed difficulties with acquiring funding and getting their projects initiated due to the impact of COVID-19 on institutions and on individual’s work-life balance. Second, statistical analysis of the leadership workshop was limited by the small number of post-workshop evaluations completed. Therefore, much of the analysis of the workshop’s success relied on qualitative metrics, such as the comments from the participants in the open-ended questions and in the chat box during the virtual workshop. Strategies to increase the completion of pre- and post-workshop evaluations for a more robust workshop analysis will need to be addressed moving forward. In addition, future sessions of the workshop would benefit from follow-up interviews with participants to gain greater understanding of participant’s experiences. Finally, the professional make-up of the resulting participant list was not as diverse as the authors intended when planning the workshop. The workshop would have benefited with greater attendance by allied health professionals in cancer care, as their input and experience is valuable in interdisciplinary teams. This should be taken into consideration when choosing recruitment avenues for future leadership development programs.

The pilot leadership development workshop was adapted to take place on a virtual web-conference platform amid the COVID-19 pandemic. The virtual delivery did impact the interactions with and among all participants, including the social aspect of networking and building relationships [29]. Mentee-mentor pairs that were supposed to have connected in-person at the conference were hindered by meeting virtually, which could explain the lack of sustained communication and professional relationship continuing beyond the workshop [30]. One must also consider the impact of participants’ engagement when attending the workshop from home or work as opposed to being within a conference environment. However, the virtual environment was a catalyst in other ways. Participants who would have been limited by cost or travel could now access the workshop more readily, making the workshop increasingly accessible for leadership development [30]. In addition, the virtual environment can allow the introduction of unique tools that enhance the workshop experience, such as the chat function used by participants to engage in discussion who otherwise may be apprehensive to speak. The authors plan to continue delivering this workshop in a virtual environment while conferences remain online, but will consider adapting to an in-person model when possible, to optimize social engagement among participants.

The positive feedback from participants and the success of the pilot leadership workshop establishes the possibility of creating additional opportunities for leadership development in cancer education. Future directions include continuing to develop this leadership workshop as a pre-conference initiative for the ICEC, Association for Medical Education in Europe, and European Association for Cancer Education annual meetings in subsequent years. For example, the following year in October 2021, the authors conducted a second leadership workshop at the ICEC after incorporating evaluations and feedback from participants. The authors have also submitted a proposal to the American Association for Cancer Education Grant in Research, Education, Advocacy, and Direct Service to expand the leadership workshop curriculum into a more comprehensive certificate-based leadership program that entails foundational learning, mentorship, and implementation of an individual learning project.

Conclusion

Feedback gained from the post-evaluations surveys from the pilot workshop titled “Essential Skills in Cancer Education: Leadership, Leading, and Influencing Change in Cancer Education,” identified an interest in opportunities to enhance leadership skills for healthcare professionals in oncology. Utilizing diverse teaching modalities, emphasizing mentorship, and supporting real-life individual learning projects are ways that leadership workshops can be made effective and valuable for participants. The virtual delivery of workshops, which may hinder social engagement, can also increase accessibility and offer alternative ways for attendees to participate. Ultimately, leadership development in cancer education for oncology professionals will improve interprofessional collaboration, facilitate change for the benefit of patients, and foster productive workplaces.

Appendix

Data Availability

The pre- and post-workshop evaluations used and analyzed for this study are available in the appendix of this article.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Ethics Approval

This study was approved by the institutional research ethics board.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Bass BM, Avolio BJ, Jung DI, Berson Y. Predicting unit performance by assessing transformational and transactional leadership. J Appl Psychol. 2003;88(2):207–218. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.2.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kumar RDC, Khiljee N. Leadership in healthcare. Anesth Intensive Care Med. 2016;17(1):63–65. doi: 10.1016/j.mpaic.2015.10.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sfantou DF, Laliotis A, Patelaro AE, Sifaki-Pistolla D, Matalliotakis M, Patelarou E (2017) Importance of leadership style towards quality of care measures in healthcare settings: a systematic review. Healthcare 5(4) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Berriochoa C, Amarnath S, Berry D, Koyfman SA, Suh JH, Tendulkar RD. Physician leadership development: a pilot program for radiation oncology residents. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2018;102(2):254–256. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2018.05.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Folkman AK, Tveit B, Sverdrup S. Leadership in interprofessional collaboration in healthcare. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2019;12:97–107. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S189199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ayub SH, Manaf NA, Hamzah MR. Leadership: communicating strategically in the 21st century. Procedia Soc Behav Sci. 2014;155:502–506. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.10.330. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McAlearney AS. Using leadership development programs to improve quality and efficiency in healthcare. J Healthc Manag. 2008;53(5):319–331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frich JC, Brewster AL, Cherlin EJ, Bradley EH. Leadership development programs for physicians: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(5):656–674. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-3141-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rahbi DA, Khalid K, Khan M. The effects of leadership styles on team motivation. Acad Strateg Manag J. 2017;16(2):1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Willard C, Luker K. Supportive car in the cancer setting: rhetoric or reality? Palliat Med. 2005;19(4):328–333. doi: 10.1191/0269216305pm1016oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miller JJ, Frost MH, Rummans TA, Huschka M, Atherton P, Brown P, Gamble G, Richardson J, Hanson J, Sloan JA, Clark MM. Role of a medical social worker in improving quality of life for patients with advanced cancer with a structured multidisciplinary intervention. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2007;25(4):105–119. doi: 10.1300/J077v25n04_07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gagliardi AR, Dobrow MJ, Wright FC. How can we improve cancer care? A review of interprofessional collaboration models and their use in clinical management. Surg Oncol. 2011;20(3):146–154. doi: 10.1016/j.suronc.2011.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim-Soon N, Abdulmaged AI, Mostafa SA, Mohammed MA, Musbah FA, Ali RR, Geman O. A framework for analyzing the relationships between cancer patient satisfaction, nurse care, patient attitude, and nurse attitude in healthcare systems. J Ambient Intell Humaniz Comput. 2022;13(1):87–104. doi: 10.1007/s12652-020-02888-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Soukup T, Lamb BW, Arora S, Darzi A, Sevdalis N, Green JS. Successful strategies in implementing a multidisciplinary team working in the care of patients with cancer: an overview and synthesis of the available literature. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2018;11:49–61. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S117945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moilanen T, Leino-Kilpi H, Kuusisto H, Rautava P, Seppänen L, Siekkinen M, Sulosaari V, Vahlberg T, Stolt M. Leadership and administrative support for interprofessional collaboration in a cancer center. J Health Organ Manag. 2020;34(7):765–774. doi: 10.1108/JHOM-01-2020-0007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vestergaard E, Nørgaard B. Interprofessional collaboration: An exploration of possible prerequisites for successful implementation. J Interprof Care. 2018;32(2):185–195. doi: 10.1080/13561820.2017.1363725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spears P. Patient engagement in cancer research from the patient's perspective. Future Oncol. 2021;17(28):3717–3728. doi: 10.2217/fon-2020-1198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Waldfogel JM, Battle DJ, Rosen M, Knight L, Saiki CB, Nesbit SA, Cooper RS, Browner IS, Hoofring LH, Billing LS, Dy SM. Team leadership and cancer end-of-life decision making. J Oncol Pract. 2016;12(11):1135–1140. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2016.013862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kneuertz PJ, Jagadesh N, Perkins A, Fitzgerald M, Moffatt-Bruce SD, Merritt RE, D’Souza DM. Improving patient engagement, adherence, and satisfaction in lung cancer surgery with implementation of a mobile device platform for patient reported outcomes. J Thorac Dis. 2020;12(11):6883. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2020.01.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weintraub P, McKee M. Leadership for innovation in healthcare: an exploration. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2019;8(3):138–144. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2018.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cochran J, Kaplan GS, Nesse RE. Physician leadership in changing times. Healthcare. 2014;2:19–21. doi: 10.1016/j.hjdsi.2014.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.De Souza JA, Hunt B, Asirwa FC, Adebamowo C, Lopes G. Global health equity: cancer care outcome disparities in high-, middle-, and low-income countries. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(1):6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.62.2860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Craighead PS. Advancing cancer control in the future through developing leaders. SA J Oncol. 2017;1(1):1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moilanen T, Leino-Kilpi H, Kuusisto H, Rautava P, Seppanen L, Siekkinen M, Sulosaari V, Vahlberg T, Stolt M. Leadership and administrative support for interprofessional collaboration in a cancer center. J Health Organ Manag. 2020;34:765–774. doi: 10.1108/JHOM-01-2020-0007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bronson D. Ellison E (2015) Crafting successful training programs for physician leaders. Healthcare

- 26.Graham GL. The leadership gap: supporting new front line leaders in cancer care. J Med Imaging Radiat Sci. 2020;51(1):54–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jmir.2019.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khan N, Ghatage L, Craighead PS. Canadian cancer programs are struggling to invest in development of future leaders: results of a Pan-Canadian survey. Healthc Q. 2016;19(3):56–60. doi: 10.12927/hcq.2016.24793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coleman CN, Wong JE, Wendling E, Gospodarowicz M, O’Brien D, Ige TA, Aruah SC, Pistenmaa DA, Amaldi U, Balogun O, Brereton HD, Formenti A, Schroeder K, Chao N, Grover S, Hahn SM, Metz J, Roth L, Dosanjh M. Capturing acquired wisdom, enabling healthful aging, and building multinational partnerships through senior global health mentorship. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2020;8(4):626–637. doi: 10.9745/GHSP-D-20-00108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Misa C, Guse D, Hohlfeld O, Durairajan R, Sperotto A, Dainotti A, Rejaie R. Lessons learned organizing the PAM 2020 virtual conference. ACM SIGCOMM Comput Commun Rev. 2020;50(3):46–54. doi: 10.1145/3411740.3411747. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Skiles M, Yang E, Reshef O, Muñoz DR, Cintron D, Lind ML, Rush A, Calleja PP, Nerenberg R, Armani A, Faust KM, Kumar M. Conference demographics and footprint changed by virtual platforms. Nat Sustain. 2022;5(2):149–156. doi: 10.1038/s41893-021-00823-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The pre- and post-workshop evaluations used and analyzed for this study are available in the appendix of this article.

Not applicable.