Abstract

Background:

Sexual minority (lesbian, bisexual, mostly heterosexual) young women face many sexual and reproductive health disparities, but there is scant information on their experiences of chronic pelvic pain, including an absence of information on prevalence, treatment, and outcomes.

Aim:

The purpose of this study was to describe the characteristics of chronic pelvic pain experiences of young women by sexual orientation identity and gender of sexual partners.

Methods:

The analytical sample consisted of a nationwide sample of 6,150 U.S. young women (mean age=23 years) from the Growing Up Today Study who completed cross-sectional questionnaires from 1996–2007.

Outcomes:

Age-adjusted regression analyses were used to examine groups categorized by sexual orientation identity (completely heterosexual [ref.], mostly heterosexual, bisexual, lesbian) and gender of sexual partner (only men [ref.], no partners, both men and women). We examined differences in lifetime and past-year chronic pelvic pain symptoms, diagnosis, treatment, and quality of life outcomes. Sensitivity analyses also examined the role of pelvic/gynecological exam history and hormonal contraceptive use as potential effect modifiers. Results: Around half of all women reported ever experiencing chronic pelvic pain, among whom nearly 90% had past-year chronic pelvic pain. Compared to completely heterosexual women, there was greater risk of lifetime chronic pelvic pain among mostly heterosexual (risk ratio [RR]=1.30, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.22–1.38), bisexual (RR=1.30, 95% CI: 1.10–1.52), and lesbian (RR=1.23, 95% CI: 1.00–1.52) young women. Additionally, compared to young women with only past male sexual partners, young women who had both men and women as past sexual partners were more likely to report chronic pelvic pain interfered with their social activities (b=0.63, 95% CI: 0.25–1.02), work/school (b=0.55, 95% CI: 0.17–0.93), and sex (b=0.53, 95% CI: 0.05–1.00).

Clinical Translation:

Healthcare providers, medical education, and field-wide standards of care should be attentive to the way sexual orientation-based healthcare disparities can manifest into differential prognosis and quality of life outcomes for women with chronic pelvic pain (particularly bisexual women).

Strengths & Limitations:

Our study is the first to examine a variety of chronic pelvic pain outcomes in a nationwide U.S. sample across different outcomes (i.e., past-year and lifetime). Though limited by sample homogeneity in terms of age, race, ethnicity, and gender, findings from this paper provide foundational insights about chronic pelvic pain experiences of sexual minority young women.

Conclusion:

Our key finding is that sexual minority women were commonly affected by chronic pelvic pain, and bisexual women face pain-related quality of life disparities.

Keywords: Sexual and Gender Minorities, Bisexuality, Pelvic Pain, Women’s Health, Chronic Pain, Epidemiology

Introduction

Chronic pelvic pain is noncyclical pelvic pain lasting for more than 6 months, which includes pain in the pelvis or genitals absent of pain caused by menstrual cramps, surgery, pregnancy, childbirth, sports-related or other injury, food poisoning, or stomach flu. Chronic pelvic pain affects up to 27% of women in the United States, and research from smaller community and convenience samples similarly estimate CPP prevalence from 6–30% among U.S. women.1 While psychological morbidity, sexual abuse, body mass index, and behavioral factors (e.g., substance use, physical activity) have been evaluated as consistent and strong risk factors for chronic pelvic pain,2 these studies had analyses that only used data of presumed heterosexual samples. There is a lack of representation of sexual minority (i.e., those who identify as lesbian, bisexual, or mostly heterosexual or those with past sexual partners who were women) young women in extant chronic pelvic pain research, which is problematic since sexual minority young women face other sexual and reproductive health (SRH) disparities (e.g., heightened risk of sexually transmitted infection3 and adolescent pregnancy4) and numerous barriers to healthcare.5–9

Sexual minority young women tend to have worse chronic pain outcomes and are 5 times more likely to experience these outcomes (e.g., muscle/joint pain, headache) compared to heterosexual young women.10 Research on healthcare access,5,7,11 sexual and reproductive healthcare experiences,8,12,13 and contraceptive use14 show that appropriate chronic pelvic pain diagnosis and treatment may not be as accessible (or of the same quality) among all sexual minority young women. Further, prevalence of social stressors, including discrimination8,15 and sexual abuse10,16 can exacerbate pain symptoms due to heightened psychological distress.17 Sexual minority young women disproportionately experience poor mental health outcomes, including greater depression and anxiety,18,19 as well as negative health outcomes like poor self-rated health and health-related quality of life,20,21 which worsen physical health through mechanisms of increased discrimination and daily experiences of sexual orientation-related stigma. These interactions are characterized as minority stress,22 which is an extension of the diathesis-stress framework, and posits that the relationship between mental and physical health is iterative, cyclical, and mediated by sexual orientation-related stress and stigma. Sexual minority women tend to experience more of the risk factors that lead to the development and/or exacerbation of chronic pelvic pain, which include childhood trauma (e.g., maltreatment, sexual abuse),16,23 anxiety and depression,18,19,23,24 social isolation and rejection,25,26 and early victimization experiences.27,28 Further, minority stressors can negatively impact chronic health29 by elevating biomarker levels responsible for inflammation30 which may influence pain symptomology and prevalence.

To date, sexual orientation differences in women’s experiences of pelvic pain have been explored in only two studies. A cross-sectional study on chronic pelvic pain and relationship quality found that bisexual women 18–45 years of age were more likely to report experiencing chronic pelvic pain “on a regular basis” (46%) than heterosexual (39%) and lesbian (15%) women, and bisexual women were more likely to report that chronic pelvic pain interfered with sexual aspects of their relationship than lesbian women.31 Similarly, in another study looking at past-year functional chronic pelvic pain (i.e., chronic pelvic pain that cannot be attributed to a diagnosis) among a longitudinal cohort of women aged 19 to 27 years old, mostly heterosexual and bisexual women were around 25% more likely to report past-year chronic pelvic pain than completely heterosexual women.16

Due to the dearth of research in this area, there is a need to examine chronic pelvic pain experiences across timespans other than recent measures (e.g., past-year16 or “regular”31 pain), and definitions beyond functional pain16 (i.e., general experiences of chronic pelvic pain not tied to receipt or lack of receipt of clinical diagnosis). In addition, lifetime and recent chronic pelvic pain experiences experienced by sexual minority women and whether other indicators of pain or pain-related quality of life indicators differ by sexual orientation have yet to be studied in depth. Understanding how chronic pelvic pain differs by both sexual orientation identity and sexual behavior (e.g., gender of sexual partners) is also an important consideration, as sexual health outcomes tend to differ based on how sexual orientation is measured; including both identity and behavior in analyses allows a more comprehensive understanding of chronic pelvic pain experiences among sexual minority young women.32,33 Further, healthcare and contraceptive use have not been examined in past studies of chronic pelvic pain among sexual minority women. Since hormonal contraceptive use is one potential therapeutic pathway for chronic pelvic pain,34 the investigation of its use may be an indicator of treatment access. Additional aspects of pain-related care, like diagnosis and treatment prevalence, along with pain-related quality of life have also not been assessed in past chronic pelvic pain literature.

Regardless of etiology, there is value in understanding broadly how conditions that manifest in or with chronic pelvic pain are experienced by sexual minority women. Given known disparities in healthcare, it is likely that chronic pelvic pain experiences are not homogenous among all sexual minority women and that their quality of life likely differs from heterosexual counterparts with chronic pelvic pain. Further, related factors, like diagnosis, treatment, and pain-related quality of life may also differ as a function of sexual orientation. Thus, the purpose of this study is to describe the prevalence of chronic pelvic pain by sexual orientation using a variety of chronic pelvic pain outcomes in a nationwide U.S. sample across different timelines (i.e., past-year and lifetime). We hypothesized that, compared to heterosexual women, sexual minority women would a.) report greater lifetime and past-year chronic pelvic pain prevalence, b.) be less likely to have a diagnosis or receive treatment, and c.) have worse pain-related quality of life outcomes, including greater difficulties with work/school, socializing, and sex.

Materials and Methods

This study consisted of 8,055 young women recruited for the U.S.-based longitudinal Growing Up Today Study (GUTS) in 1996. Biennial follow-up of this cohort was ongoing and consisted of paper surveys from 1996–2007. Detailed information about the GUTS protocol can be found in Field et al.35 Participants were hierarchically excluded from analysis if they did not respond to the GUTS 2007 questionnaire (which had the chronic pelvic pain outcomes of interest; n=1,897), or were missing information on all chronic pelvic pain outcomes (n=8). The final analytical sample consisted of 6,150 young women. This study was approved by the [MASKED] Institutional Review Board.

Sexual orientation has been collected on every questionnaire in the form of two items: sexual orientation identity (from 1999 onwards) and gender of sexual partners (from 2001 onwards). The sexual orientation identity item was adapted from the Minnesota Adolescent Health Survey,36 which asked about feelings of attraction and identity with six mutually exclusive response options: completely heterosexual [reference], mostly heterosexual, bisexual, mostly homosexual, completely homosexual, and unsure. For current analyses, we combined the mostly and completely homosexual categories into a single subgroup due to the small size of the mostly homosexual category.

Gender of sexual partners was a lifetime measure and included the response options of “male,” “female,” “both male and female.” Gender of sexual partner subgroups were then modeled as: no partners, only men [reference], and both men and women. In 2007, there were too few participants reporting only female partners and chronic pelvic pain (n=8); further, few (n=1) responded to additional pain measures for most descriptive and bivariate statistics to be calculated (i.e., no variation in responses so means and standard deviations could not be calculated). Therefore, these women were not included in inferential analyses modeling gender of sexual partners.

Chronic pelvic pain variables were asked in the 2007 GUTS questionnaire, which included items about lifetime and past-year chronic pelvic pain. Chronic pelvic pain was defined as “pain in your pelvis or genitals” not counting “pain caused by menstrual cramps, surgery, pregnancy, childbirth, sports-related or other injury, food poisoning, or stomach flu.” Frequency of lifetime pain was assessed on a Likert scale with anchors ranging from “never,” “rarely,” “sometimes,” “often,” or “always.” If a participant reported any pain, they were then asked about ages when pain was experienced (mark all that apply), whether they sought treatment from a doctor (past year [yes, no], lifetime [yes, no]), if they ever received a diagnosis from a doctor (yes, no), frequency of past-year pain (1–2 times; 3–11 times; monthly, but not weekly; weekly, but not daily; daily), and the following health-related quality of life items: degree of difficulty going to school or work in the past year; degree of difficulty socializing in the past year; and degree of difficulty having sex in the past year. These latter three items were assessed on a continuous scale ranging from 0 (“no difficulty”) through 6 (“extreme difficulty”). Based on an examination of variable distributions, skewness, and kurtosis for scale item outcomes, univariate normality indicated these variables were acceptable for use in models as interval outcomes.37,38 For analysis, the lifetime chronic pelvic pain variable was modeled as two categories (“never experienced chronic pelvic pain” and “experienced chronic pelvic pain” categories) and the past-year chronic pelvic pain was also modeled as two categories (“no past-year chronic pelvic pain” and “experienced past-year chronic pelvic pain”).

Model covariates included age in years in 2007. Potential effect modifiers of lifetime and past-year hormonal contraception use (yes, no) and ever having a pelvic/gynecological exam (yes, no) were asked in the 2007 questionnaire, with responses carried forward from previous questionnaire years in order to create composite lifetime variables. Race/ethnicity was collected at baseline and its categories included non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic or Latino/a/x, non-Hispanic Asian, and non-Hispanic another race/multiracial. This variable was included in Table 1 for descriptive purposes of characterizing the sample, but not for effect modification due to prohibitively small sub-group sizes among women who experienced chronic pelvic pain.

Table 1.

Distribution of sociodemographics, chronic pelvic pain, and sexual and reproductive healthcare use by sexual orientation in a cohort of U.S. young women (N=6,150).

| Sexual Identity | Gender of Sexual Partners | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Completely Heterosexual (n=4,824) | Mostly Heterosexual (n=1,099) | Bisexual (n=141) | Lesbian (n=86) | N | Only Male Partners (n=4,876) | No Partners (n=537) | Male and Female Partners (n=706) | |

|

| |||||||||

| Full Sample | 6,150 | 6,119 | |||||||

| Current Age (in years), Mean (SD), range 19–27 | 22.7 (1.7) | 22.7 (1.7) | 22.7 (1.7) | 23 (1.7) | 22.8 (1.7) | 22 (1.6) | 23 (1.7) | ||

| Age at Menarche (in years), Mean (SD), range 8–18 | 12.4 (1.2) | 12.3 (1.2) | 12.1 (1.1) | 12.2 (1.2) | 12.3 (1.2) | 12.4 (1.2) | 12.3 (1.1) | ||

| Race/Ethnicity, % (N) | |||||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 93.7 (4,507) | 92.2 (1,009) | 87.9 (124) | 89.5 (77) | 93.4 (4,543) | 94.0 (503) | 91.3 (640) | ||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0.7 (35) | 0.9 (10) | 2.8 (4) | 1.2 (1) | 0.8 (40) | 0.4 (2) | 1.1 (8) | ||

| Hispanic or Latino/a/x | 1.5 (70) | 1.6 (17) | 1.4 (2) | 4.7 (4) | 1.4 (67) | 1.1 (6) | 2.9 (20) | ||

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 1.4 (66) | 2.5 (27) | 0.7 (1) | 0.0 (0) | 1.6 (77) | 1.5 (8) | 1.3 (9) | ||

| Non-Hispanic Another Race/Multiracial | 2.7 (130) | 2.83 (31) | 7.09 (10) | 4.65 (4) | 3.0 (16) | 3.0 (16) | 3.4 (24) | ||

| Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare Use | |||||||||

| Ever Pelvic/Gynecological Exam, % (N) | 91.4 (4,362) | 94.6 (1,033) | 88.4 (122) | 83.5 (71) | 93.4 (4,509) | 74.6 (399) | 94.7 (662) | ||

| Ever Hormonal Contraceptive Use, % (N) | 79.3 (3,827) | 86.4 (950) | 82.3 (116) | 54.7 (47) | 84.3 (4,111) | 37.4 (201) | 87.7 (619) | ||

| Ever Experienced Chronic Pelvic Pain | 41.7 (2,009) | 54.1 (593) | 54.3 (76) | 51.8 (44) | 44.1 (2,144) | 33.5 (180) | 55.4 (390) | ||

| Women who Ever Experienced Chronic Pelvic Pain | 2,722 | 2,714 | |||||||

| Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare Use | |||||||||

| Ever Pelvic/Gynecological Exam, % (N) | 95.8 (1,923) | 97.1 (576) | 89.5 (68) | 79.5 (35) | 96.7 (2,073) | 83.9 (151) | 95.6 (373) | ||

| Past-Year Hormonal Contraceptive Use, % (N) | 80.1 (1,399) | 79.9 (430) | 51.5 (34) | 53.6 (15) | 80.8 (1,547) | 61.0 (64) | 74.6 (265) | ||

| Lifetime Chronic Pelvic Pain | |||||||||

| Pain Experienced Often/Very Often, % (N) | 6.8 (137) | 7.9 (47) | 13.2 (10) | 4.5 (2) | 7.1 (153) | 5.0 (9) | 8.7 (34) | ||

| Ever Sought Treatment for Chronic Pelvic Pain, % (N) | 57.0 (290) | 59.1 (114) | 54.5 (18) | 33.3 (6) | 58.5 (332) | 48.9 (23) | 54.1 (72) | ||

| Ever Received Diagnosis for Chronic Pelvic Pain, % (N) | 35.2 (180) | 38.7 (74) | 28.1 (9) | 23.5 (4) | 35.6 (203) | 40.4 (19) | 33.1 (44) | ||

| Past-Year Chronic Pelvic Pain (2006–2007) | |||||||||

| Reported Chronic Pelvic Pain, % (N) | 92.3 (468) | 88.0 (168) | 96.9 (31) | 94.1 (16) | 91.5 (518) | 91.5 (43) | 91.0 (121) | ||

| Chronic Pelvic Pain Severity, M (SD), | 3.3 (1.3) | 3.3 (1.4) | 3.5 (1.3) | 2.9 (1.3) | 3.2 (1.3) | 3.2 (1.4) | 3.4 (1.4) | ||

| Sought Treatment for Chronic Pelvic Pain in Past Year, % (N) | 33.9 (168) | 35.9 (66) | 28.1 (9) | 26.7 (4) | 34.4 (190) | 28.3 (13) | 34.6 (44) | ||

| Degree of Difficulty with School or Work, M (SD) | 1.8 (1.8) | 1.9 (1.8) | 2.5 (2.3) | 1.4 (1.3) | 1.7 (1.8) | 1.9 (1.9) | 2.3 (2) | ||

| Degree of Difficulty with Social Activities, M (SD) | 2.1 (1.9) | 2.2 (1.8) | 2.7 (2.3) | 1.9 (1.8) | 2 (1.8) | 2.2 (2.1) | 2.7 (2) | ||

| Degree of Difficulty with Sex, M (SD) | 2.7 (2.1) | 3.4 (2.2) | 3.3 (2.2) | 2.7 (2.1) | 2.8 (2.1) | N/A | 3.4 (2.2) | ||

Note. GUTS participants were born 1982–1987. SD is “standard deviation.” Hormonal contraceptive use includes birth control pill, injectable estrogen, implant, and ring methods. Anchor range for “Chronic Pelvic Pain Severity” is 0 (“No Pain”) – 6 (“Extreme Pain”); range for “Degree of Difficulty” items is 0 (“No Difficulty”) – 6 (“Extreme Difficulty). “Past-year” items assess 2006–2007. “Only Female Partners” not included as a Gender of Sexual Partners’ category due to absence of data. N/A is “not applicable.”

Proportions and percentages were calculated for binary variables and means, and standards deviations were calculated for continuous variables, each reported by sexual orientation identity and gender of sexual partners. Age-adjusted log-binomial and log-Poisson regression models were used to obtain risk ratios (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) and assess differences by sexual orientation identity (completely heterosexual [ref.], mostly heterosexual, bisexual, lesbian) and gender of sexual partner (only men [ref.], no partners, both men and women) in lifetime and past-year chronic pelvic pain symptom, diagnosis, and treatment outcomes. For health-related quality of life outcomes, age-adjusted linear regression models were used to obtain unstandardized beta coefficients (b), standard errors (SE), and 95% CI. To account for clustering of siblings among GUTS participants, a robust sandwich estimator was used based on a compound symmetry correlation structure. Sensitivity analyses also examined the role of pelvic/gynecological exam history and hormonal contraceptive use as potential effect modifiers through stratified regression analyses. Participants missing data on a given predictor and/or outcome were excluded from their specific analysis.

Results

The sample was primarily non-Hispanic white (93.3%), had high sexual and reproductive healthcare use (over 91.8% had ever had a pelvic/gynecological exam and 80.3% ever used hormonal contraception, though these percentages were lower among certain sexual minority subgroups), and the mean age in 2007 was 23 years (range: 19–27 years). Demographic and chronic pelvic pain descriptive analyses further stratified by sexual orientation identity and gender of sexual partners are presented in Table 1.

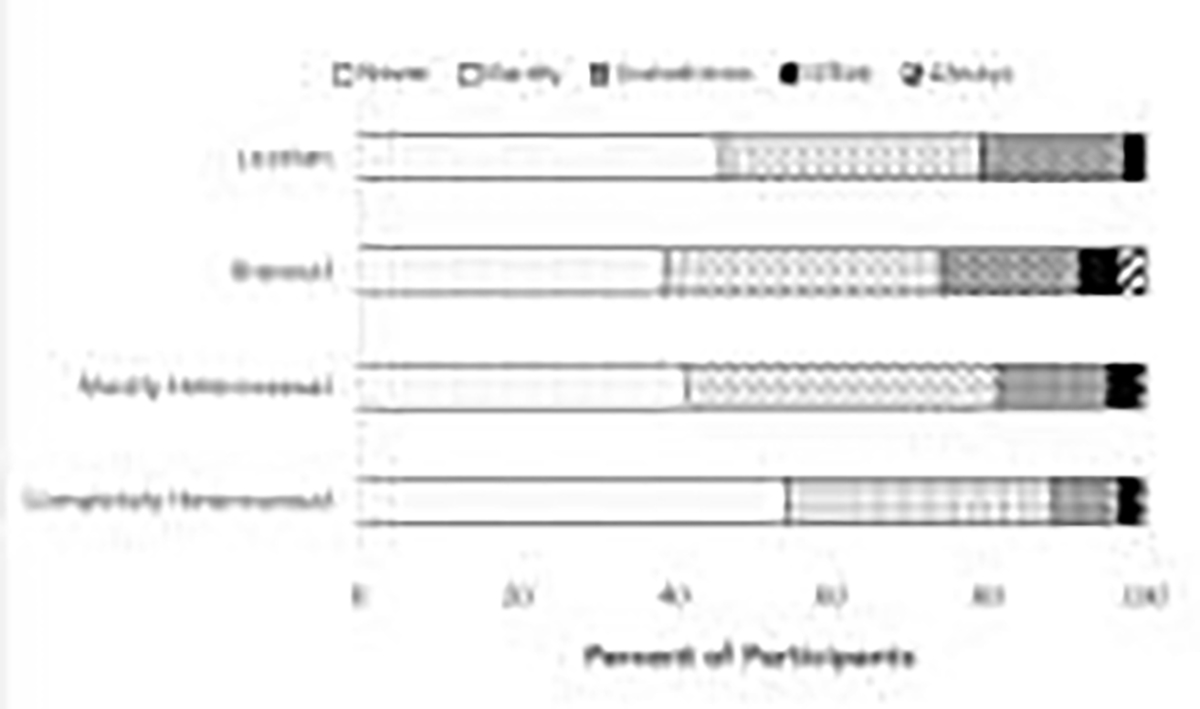

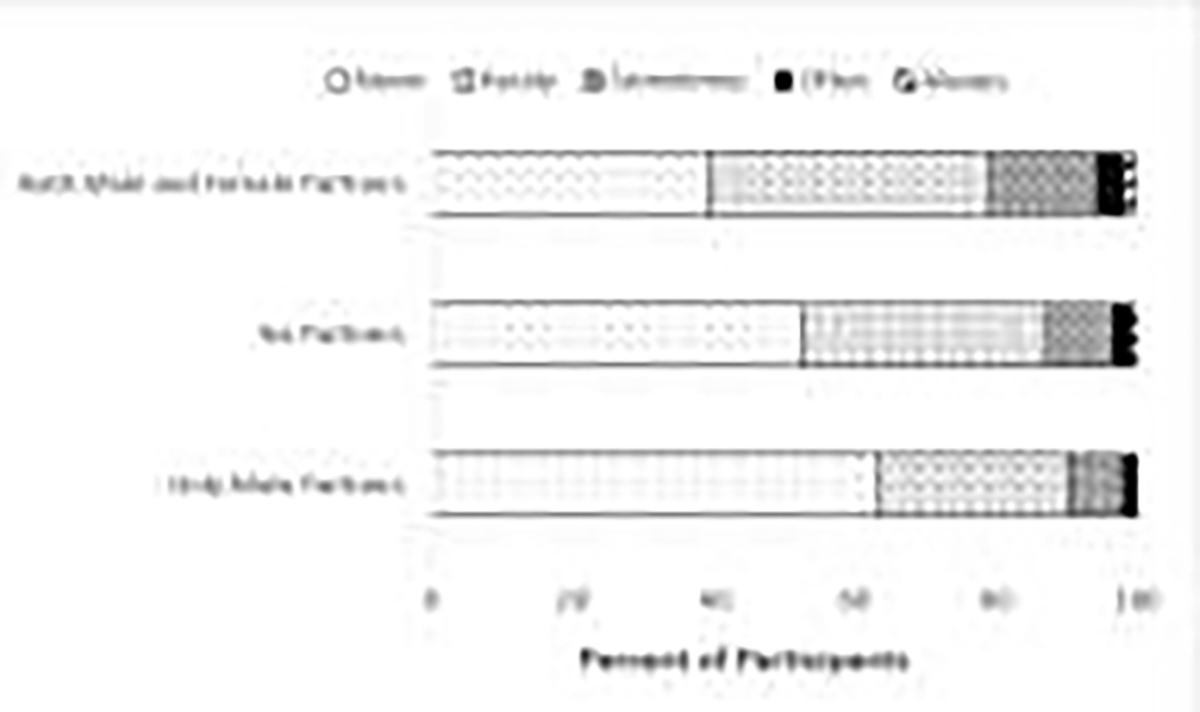

In the full sample (N=6,150), roughly half (44.3%, n=2,726) of young women reported ever experiencing chronic pelvic pain, and this pattern persisted for each sexual orientation identity group: bisexual young women had the greatest proportion of lifetime chronic pelvic pain (n=76, 54.3%), followed by completely heterosexual women (n=593, 54.1%), then lesbian women (n=44, 51.8%). When examining distributions by gender of sexual partners, a similar pattern emerged. There was greater variation in chronic pelvic pain frequency when examining differences by gender of sexual partners. Young women with both male and female partners had the greatest proportion of lifetime chronic pelvic pain (n=390, 55.4%), followed by those with only male partners (n=2,144, 44.1%), those with only female partners (n=8, 36.4%), and finally, those with no past partners (n=180, 33.5%). Looking at symptom frequency, bisexual young women tended to have larger proportions endorsing “always” experiencing chronic pelvic pain in their lifetimes (Figure 1). Women with both male and female partners had higher proportions of “often” and “always” experiencing chronic pelvic pain symptoms than those with only male partners or no partners (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Percentages of lifetime chronic pelvic pain symptom frequency by sexual orientation identity (N=6,150).

Figure 2.

Percentages of lifetime chronic pelvic pain symptom frequency by gender of lifetime sexual partners (N=6,150).

First, differences were examined in lifetime primary chronic pelvic pain distributions. Compared to completely heterosexual young women, mostly heterosexual (RR=1.30, 95% CI: 1.22, 1.38), bisexual (RR=1.30, 95% CI: 1.11–1.52), and lesbian young women (RR=1.23, 95% CI: 1.00–1.52) were more likely to report ever experiencing chronic pelvic pain. Further, compared to young women with only male partners, young women with no partners (RR=0.76, 95% CI: 0.67, 0.86) were less likely to ever experience chronic pelvic pain, while young women with both male and female partners (RR=1.26, 95% CI: 1.17, 1.35) were more likely to ever experience chronic pelvic pain.

Table 2 displays multivariable log-binomial and log-Poisson regression results (adjusted for age) examining differences in chronic pelvic pain variables by sexual orientation identity and gender of sex partners (restricted to participants who ever reported chronic pelvic pain). Among young women who ever experienced pelvic pain, mostly heterosexual (RR=0.96, 95% CI: 0.90, 1.02), bisexual (RR=1.05, 95% CI: 0.98, 1.12), and lesbian (RR=0.97, 95% CI: 0.82, 1.15) young women did not differ from completely heterosexual young women in experiencing pain in the past year. Very few differences emerged by sexual orientation identity for other variables, including no differences in past-year pain severity. In an alternative analysis of lifetime pain frequency, compared to completely heterosexual young women, bisexual young women were more likely to have experienced lifetime pelvic pain often/very often (RR=1.93, 95% CI: 1.06, 3.52), and mostly heterosexual young women had greater difficulty with sex in the past year (b=0.70, 95% CI: 0.30, 1.10). Differences were also examined by gender of sexual partners. Among young women who ever experienced pelvic pain, young women with no partners (RR=1.00, 95% CI: 0.91, 1.09) and those with male and female partners (RR=1.00, 95% CI: 0.94, 1.06) did not significantly differ from completely heterosexual young women in experiencing pain in the past year. Differences by gender of sexual partner did emerge for health-related quality of life items. Young women with both male and female sexual partners had greater difficulty in the past year with school/work (b=0.55, 95% CI: 0.17, 0.93), social activities (b=0.63, 95% CI: 0.25, 1.02), and sex (b=0.53, 95% CI: 0.05, 1.00) compared to those with only male partners.

Table 2.

Age-adjusted regression models of differences in chronic pelvic pain by sexual identity (N=2,722) and gender of sexual partners (N=2,714) in a cohort of U.S. young women who ever experienced chronic pelvic pain.

| Completely Heterosexual | Mostly Heterosexual | Bisexual | Lesbian | ||||

|

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR (95% CI) | RR | (95% CI) | RR | (95% CI) | RR | (95% CI) | |

|

| |||||||

| Lifetime Pain Experienced Often/Very Often | 1.00 | 1.16 | (0.85, 1.60) | 1.93 | (1.06, 3.52) | 0.66 | (0.17, 2.60) |

| Sought Treatment for Chronic Pelvic Pain | |||||||

| Ever* | 1.00 | 1.05 | (0.92, 1.21) | 1.01 | (0.74, 1.38) | 0.61 | (0.32, 1.17) |

| Past Year | 1.00 | 1.06 | (0.84, 1.33) | 0.84 | (0.47, 1.48) | 0.79 | (0.34, 1.85) |

| Ever Received Diagnosis for Chronic Pelvic Pain | 1.00 | 1.12 | (0.90, 1.39) | 0.83 | (0.47, 1.47) | 0.65 | (0.27, 1.54) |

|

|

|||||||

| b (SE) | b (SE) | (95% CI) | b (SE) | (95% CI) | b (SE) | (95% CI) | |

|

|

|||||||

| Chronic Pelvic Pain Severity in Past Year | 1.00 | −0.01 (0.12) | (−0.25, 0.23) | 0.29 (0.24) | (−0.17, 0.76) | −0.33 (0.32) | (−0.94, 0.29) |

| Degree of Difficulty with School or Work in Past Year | 1.00 | 0.08 (0.16) | (−0.24, 0.40) | 0.67 (0.40) | (−0.10, 1.45) | −0.33 (0.32) | (−0.96, 0.28) |

| Degree of Difficulty with Social Activities in Past Year | 1.00 | 0.07 (0.16) | (−0.26, 0.39) | 0.61 (0.40) | (−0.17, 1.39) | −0.22 (0.45) | (−1.09, 0.66) |

| Degree of Difficulty with Sex in Past Year | 1.00 | 0.70 (0.20) | (0.30, 1.10) | 0.69 (0.41) | (−0.11, 1.49) | −0.04 (0.57) | (−1.16, 1.08) |

|

| |||||||

| Only Male Partners | No Partners | Male and Female Partners | |||||

|

|

|||||||

| RR (95% CI) | RR | (95% CI) | RR | (95% CI) | |||

|

|

|||||||

| Lifetime Pain Experienced Often/Very Often | 1.00 | 0.71 | (0.37, 1.37) | 1.22 | (0.85, 1.74) | ||

| Sought Treatment for Chronic Pelvic Pain* | |||||||

| Ever | 1.00 | 1.02 | (0.74, 1.41) | 0.68 | (0.36, 1.29) | ||

| Past Year | 1.00 | 0.83 | (0.51, 1.34) | 0.99 | (0.76, 1.30) | ||

| Ever Received Diagnosis for Chronic Pelvic Pain | 1.00 | 1.34 | (0.95, 1.88) | 0.94 | (0.72, 1.23) | ||

|

|

|||||||

| b (SE) | b (SE) | (95% CI) | b (SE) | (95% CI) | |||

|

|

|||||||

| Chronic Pelvic Pain Severity in Past Year | 1.00 | −0.03 (0.23) | (−0.47, 0.41) | 0.19 (0.14) | (−0.08, 0.47) | ||

| Degree of Difficulty with School or Work in Past Year | 1.00 | 0.21 (0.30) | (−0.38, 0.80) | 0.55 (0.20) | (0.17, 0.93) | ||

| Degree of Difficulty with Social Activities in Past Year | 1.00 | 0.18 (0.33) | (−0.47, 0.82) | 0.63 (0.20) | (0.25, 1.02) | ||

| Degree of Difficulty with Sex in Past Year | 1.00 | N/A | N/A | 0.53 (0.24) | (0.05, 1.00) | ||

Note. Bolded values indicate adjusted relative risk ratios or regression coefficients with significance at p < .05 and 95% confidence intervals. Anchor range for “Chronic Pelvic Pain Severity” is 0 (“No Pain”) – 6 (“Extreme Pain”); range for “Degree of Difficulty” items is 0 (“No Difficulty”) – 6 (“Extreme Difficulty).

Sensitivity analyses were performed by stratifying lifetime and past year chronic pelvic pain analyses by healthcare utilization strata (ever pelvic/gynecological exam, ever hormonal contraceptive use, past-year hormonal contraceptive use). When examining differences in lifetime chronic pelvic pain by sexual orientation identity (Supplemental Table 1) and gender of sexual partners (Supplemental Table 2), several patterns emerged. For lifetime chronic pelvic pain, stratified analyses did not vary substantially for either sexual orientation identity or gender of sexual partners. RRs were all in the same direction and within similar magnitude compared to the overall sample with mostly heterosexual and bisexual young women. Lesbian young women who were able to access care (ever gynecological/pelvic exam, ever hormonal contraception use) no longer differed from heterosexual counterparts. Young women with male and female partners reported greater risk of lifetime chronic pelvic pain regardless of pelvic/gynecological exam history. Additionally, only young women with male and female partners who ever used hormonal contraception were more likely than completely heterosexual women who ever used hormonal contraception to have ever had chronic pelvic pain.

For past-year chronic pelvic pain, stratified analyses by pelvic/gynecological exam were largely the same for all groups – an exception being that among those who ever had a pelvic/gynecological exam, lesbian young women were more likely than heterosexual young women to report past-year chronic pelvic pain. Similarly, among those who used hormonal contraception in the past year, only bisexual young women were more likely than heterosexual counterparts to have past-year chronic pelvic pain. Very few differences emerged when stratifying the models that examined chronic pelvic pain outcomes by gender of sexual partners.

Conclusion

Chronic pelvic pain affects up to one-third of women in the United States.1 However, there is a lack of understanding how women from different sociodemographic backgrounds—including sexual minority women—experience chronic pelvic pain and navigate its diagnosis and treatment. This lack of study leaves significant clinical gaps in the understanding and care of sexual minority women with chronic pelvic pain. Our study indicates chronic pelvic pain is a prevalent medical problem in this population: over 50% of young sexual minority women reported chronic pelvic pain in their lifetimes (compared to only 40% of completely heterosexual young women). Further this was not simply a historic or cumulative phenomenon, with 90% of those reporting ever experiencing chronic pelvic pain noting they experienced this pain within the past year. Bisexual and mostly heterosexual young women, as well as young women with both male and female partners, were more likely than heterosexual referents (and those with only male partners) to report lifetime chronic pelvic pain. Findings indicate that chronic pelvic pain-related prevalence and quality of life are not agnostic to sexual orientation identity and behavior. As such, a key takeaway from our analyses is that chronic pelvic pain prevalence is high among women of all sexual orientations, while life-impact appears to be worse among plurisexual women (i.e., women who identify as being attracted to multiple genders or have sexual experiences with multiple genders). Thus, research and practice regarding chronic pelvic pain should be cognizant of how sexual minority-related factors can shape the overall context of care.

This is the first study to assess prevalence of lifetime chronic pelvic pain by sexual orientation in a U.S.-wide sample, thus these proportions are not readily comparable with other studies. However, in one study of an international convenience sample of adult women, bisexual women were also more likely to report experiencing genital pain “on a regular basis” (38.5%) compared to heterosexual (28.2%) and lesbian (23.3%) women.31 Prevalence is not immediately comparable to our sample due to differences in measurement; over half of sexual minority young women in our study (when observing differences by sexual orientation identity) reported lifetime chronic pelvic pain, with around 90% of these women reporting pain in the past year. An additional study of past-year functional (i.e., not diagnosed) pain in this 2007 GUTS cohort similarly found that mostly heterosexual and bisexual young adult women had a higher prevalence of functional abdominal and pelvic pain than heterosexual referents.16 Cumulatively, these studies indicate that sexual minority women share similar risks with heterosexual women concerning prevalence of chronic pelvic pain, and further point to increased risk among plurisexual women. Future research should be cognizant of how other identities may further modify chronic pain prevalence among sexual minority young women, as these findings are unlikely to be homogenous when considering race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and may be different among transgender, nonbinary, and gender expansive individuals.

Potential mechanisms behind these differences experienced by plurisexual women may include minority stress, healthcare access, and hormonal contraception use history. Chronic stressors and traumatic events experienced by sexual minorities, specifically plurisexual women, can drive adverse health outcomes like chronic pain.17,39 For instance, plurisexual women who have experienced bisexual stigma report greater lifetime odds of sexual violence and verbal coercion.40 Sexual violence is a potential risk factor for the development of chronic pelvic pain2,41 and has previously been identified as a mediator of functional pelvic pain in bisexual and mostly heterosexual young adult women (when compared to heterosexual women).16 Depressive symptoms, social support, and self-esteem are additional minority stress-related mediators of functional pain disparities among plurisexual women.16 Lesbian women report lower levels of identity-related minority stressors compared to bisexual women, which underscores the need to investigate minority stress mechanisms that are specific to plurisexual women.42 Greater depressive symptomology is also linked to adverse chronic pelvic pain-related quality of life outcomes,43 which may also partially explain why young women who had sex with both men and women had greater difficulty with work/school, socializing, and sex due to pelvic pain symptoms in our sample. Such psychosocial mechanisms may also have implications for potential sexual orientation-based disparities in symptom severity over time and health-related quality of life, which should be examined in future research.

In addition to these psychosocial mechanisms, poorer quality of healthcare access and utilization (including health insurance, annual exams, and delaying necessary acute care due to discrimination or other provider-patient factors)5 can affect health outcomes. Given the high prevalence of chronic pelvic pain of women in our sample, there is a need to examine whether quality of care is similar among women of different sexual orientations. The present study was limited by using only two lifetime indicators of care access—ever seeking treatment or received a diagnosis—which does not capture whether there were differences in time-to-diagnosis, provider-patient communication quality, treatment efficacy, experiences of pain-related stigma in clinical care, and other clinical factors. Thus, our null findings that overall diagnosis and lifetime treatment-seeking prevalence did not differ by sexual orientation are inconclusive given the lack of nuanced measurement. This is important to consider, as disparities in these areas may drive our findings bisexual young women’s greater difficulties with sex along with women with male and female sexual partners’ greater difficulties with school/work, socializing, and sex. Though there were no differences in overall treatment seeking or diagnosis receipt in our sample, quality of care and other healthcare access and quality indicators (like provider-patient communication, disaffirming experiences surrounding hormonal contraceptive access, and discrimination toward plurisexual women) were not assessed. These indicators are known to act as barriers to sexual and reproductive healthcare among sexual minority women8,9,44,45 and may contribute to these adverse chronic pelvic pain-related quality of life outcomes. Further, healthcare experiences meant to address chronic pain can instead be stigmatizing,46–48 resulting in further disengagement from medical care48,49 and diagnostic delay.50 Though the present study did not examine differences in healthcare quality in detail, outcomes like time to diagnosis, treatment quality, and provider-patient communication could shed light on whether heterosexual and sexual minority young women with chronic pelvic pain are receiving the same standards of care. Thus, it is highly important that future research considers the full clinical continuum of care that sexual minority young women with chronic pelvic pain conditions encounter.

It is important to note that chronic pelvic pain diagnosis, particularly when associated with potential secondary causes like endometriosis, is difficult to accurately assess in research settings (and likely underestimates cases), as only more severe cases (e.g., longer symptom duration)51 with greater care utilization52 tend to receive diagnosis. Thus, null findings in sexual orientation-based diagnosis may be driven by lower care access among sexual minority young women, particularly lesbian women.5 Additionally, current hormonal contraceptive use is inversely related to chronic pelvic pain caused by dysmenorrhea,2 thus greater hormonal contraceptive use among plurisexual women14 (and indicators of access, like annual pelvic exams) may underestimate true chronic pelvic pain prevalence. To address this, sensitivity analyses stratifying young women by hormonal contraceptive use history found that plurisexual young women were still more likely than heterosexual referents to report lifetime chronic pelvic pain regardless of hormonal contraceptive use history, indicating mechanisms beyond contraceptive use contribute to previously identified disparities. However, only lesbian young women in stratum with indicators of reduced healthcare access (e.g., no hormonal contraceptive use; never pelvic/gynecological exam) were more likely than heterosexual referents to report lifetime chronic pelvic pain, indicating treatment access may underestimate chronic pelvic pain proportions among this subgroup.

There were additional limitations with the study design. Homogeneity of sociodemographics, particularly race/ethnicity and gender identity, precluded intersectional analysis. While such homogeneity is useful in reducing the number of theoretical correlates of chronic pelvic pain, it inhibits generalizability of our findings to other groups. The sample consisted entirely of cisgender women, thus findings cannot be generalized to transgender, nonbinary, or gender expansive people. Similarly, partner gender identity was not collected, thus the “gender of sexual partners” variable cannot be generalized to women who have partners of varying genders. Further, causal mechanisms of chronic pelvic pain were not addressed in the current study design, and future research should incorporate measures of discrimination, provider-patient communication, additional identity categories (e.g., race, ethnicity, gender identity, weight status, developmental age group), and comorbidities (e.g., dysmenorrhea, endometriosis) into the research design. Analyses were cross-sectional; additional research examining predictors of chronic pelvic pain symptomology and diagnosis by sexual orientation group (e.g., through survival analysis methods) can shed light on how risk factors for chronic pelvic pain function as mediators of the relationship between plurisexual sexual orientation and pain outcomes, including quality of life. Longitudinal analysis would also be useful in examining whether pain prevalence, severity, and other care-related factors (like time-to-diagnosis) differ as a function of age. Further, larger sample sizes would allow for more technically sound statistical analyses of effect modification; this study’s stratified regression analyses were selected as a statistical method due to the insufficient sample size needed for modelling interactions (without condensing all sexual minorities into one subgroup, which would hide patterns primarily driven by plurisexual sexual orientations). Multiple barriers to care experienced by sexual minority women may have led to under-reporting of chronic pelvic pain.5 However, our sample is the largest to include measures of sexual orientation and chronic pelvic pain, and is thus useful in highlighting important areas for further research. Finally, data on chronic pelvic pain used in our study was last collected in 2007. However, disparities in regular chronic pelvic pain identified in a 2015 study,31 in conjunction with more recent studies finding associations between discrimination and sexual health,53 poorer quality of life (including more severe pain) among sexual minority women with disabilities compared to those without,54 and higher prevalence of migraine pain in sexual minority women compared to heterosexual women,55 indicate that chronic pain prevalence and concerns are unlikely to have improved. Further, mediators of sexual orientation and functional chronic pelvic pain prevalence include sexual trauma,16 which has a life-course impact on pain and wellbeing trajectories, and future research should account for longitudinal measurements of chronic pelvic pain and its associated risk factors.

A high prevalence of lifetime chronic pelvic pain (>50%) among sexual minority young women in our sample (and similarly high prevalence—nearly 90%—of past-year pain among these women) suggests a need for therapeutic and clinical diagnosis and treatment guidance that accounts for sexual minority-specific factors. There is a need for further research on the etiology, prevalence, incidence, and outcomes of chronic pelvic pain in sexual minority women. Chronic pelvic pain currently remains largely undocumented in sexual minority women, leaving them invisible in a field of medical practice already plagued by gender bias,56 stigma,57 poor provider-patient communication,58 and diagnostic delay.59,60 This may in turn leave plurisexual women with a disproportionate burden of adverse chronic pelvic pain-related quality of life outcomes, identified in our study as greater difficulties with work/school, socializing, and sex. In our study, chronic pelvic pain prevalence varied as a function of the sexual orientation measure used. This indicates the need for multidimensional measures of sexual orientation identity and behavior in research as well as in clinical settings, such as when taking a social history. Resulting differences in provider-patient communication that occur may be a specific manifestation of how cultural humility61 practices in chronic pelvic pain practice environments shape treatment and quality of life outcomes. Comprehensive assessment of both sexual orientation identity and partner history enables medical professionals to more holistically engage patients regarding their sexual and gynecological health needs in an area of medicine that often leaves sexual minority women and chronic pain patients otherwise stigmatized or unheard. Our key finding is that sexual minority women are commonly affected by chronic pelvic pain. Research and clinical approaches to chronic pelvic pain diagnosis and treatment must be cognizant of how sexual minority-specific barriers to care (particularly those affecting plurisexual women, like biphobia) can shape symptom, diagnosis, and treatment experiences.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

This research was supported by U01HL145386 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health as well as R01HD057368 and R01MD015256 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Development. Dr. Tabaac was supported by F32HD100081 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Development, Dr. Sutter was supported by T32HS026120 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Dr. Charlton was supported by grant MRSG CPHPS 130006 from the American Cancer Society, and Dr. S. Bryn Austin was supported by the HRSA training grant T76-MC00001 from the Maternal and Child Health Bureau.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ahangari A Prevalence of Chronic Pelvic Pain Among Women: An Updated Review. Pain Phys. 2014;2;17(2;3):E141–E147. doi: 10.36076/ppj.2014/17/E141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Latthe P, Mignini L, Gray R, Hills R, Khan K. Factors predisposing women to chronic pelvic pain: Systematic review. British Medical Journal. 2006;332(7544):749–751. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38748.697465.55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Risks McNair R. and prevention of sexually transmissible infections among women who have sex with women. Sexual Health. 2005;2(4):209–217. doi: 10.1071/SH04046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Charlton BM, Roberts AL, Rosario M, et al. Teen Pregnancy Risk Factors Among Young Women of Diverse Sexual Orientations. Pediatrics. 2018;141(4):e20172278. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-2278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tabaac AR, Solazzo AL, Gordon AR, Austin SB, Guss C, Charlton BM. Sexual orientation-related disparities in healthcare access in three cohorts of U.S. adults. Preventive Medicine. 2020;132:105999. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2020.105999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mayer KH, Bradford JB, Makadon HJ, Stall R, Goldhammer H, Landers S. Sexual and gender minority health: what we know and what needs to be done. American journal of public health. 2008;98(6):989–995. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.127811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gonzales G, Blewett LA. National and state-specific health insurance disparities for adults in same-sex relationships. American journal of public health. 2014;104(2):e95–e104. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wingo E, Ingraham N, Roberts SCM. Reproductive Health Care Priorities and Barriers to Effective Care for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer People Assigned Female at Birth: A Qualitative Study. Women’s Health Issues. Published online 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2018.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Higgins JA, Carpenter E, Everett BG, Greene MZ, Haider S, Hendrick CE. Sexual Minority Women and Contraceptive Use: Complex Pathways Between Sexual Orientation and Health Outcomes. American Journal of Public Health. 2019;109(12):1680–1686. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Katz-Wise SL, Everett B, Scherer EA, Gooding H, Milliren CE, Austin SB. Factors associated with sexual orientation and gender disparities in chronic pain among U.S. adolescents and young adults. Preventive Medicine Reports. 2015;2:765–772. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2015.09.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blosnich JR, Farmer GW, Lee JGL, Silenzio VMB, Bowen DJ. Health inequalities among sexual minority adults: evidence from ten U.S. states, 2010. American journal of preventive medicine. 2014;46(4):337–349. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.11.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Everett BG. Sexual orientation disparities in sexually transmitted infections: examining the intersection between sexual identity and sexual behavior. Archives of sexual behavior. 2013;42(2):225–236. doi: 10.1007/s10508-012-9902-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Flanders CE, Ross LE, Dobinson C, Logie CH. Sexual health among young bisexual women: a qualitative, community-based study. Psychology & Sexuality. 2017;8(1–2):104–117. doi: 10.1080/19419899.2017.1296486 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Charlton BM, Janiak E, Gaskins AJ, et al. Contraceptive use by women across different sexual orientation groups. Contraception. 2019;100(3):202–208. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2019.05.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hirsch O, Löltgen K, Becker A. Lesbian womens’ access to healthcare, experiences with and expectations towards GPs in German primary care. BMC Family Practice. 2016;17(1):162. doi: 10.1186/s12875-016-0562-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roberts AL, Rosario M, Corliss HL, Wypij D, Lightdale JR, Austin SB. Sexual Orientation and Functional Pain in U.S. Young Adults: The Mediating Role of Childhood Abuse. Mazza M, ed. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(1):e54702. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brown TT, Partanen J, Chuong L, Villaverde V, Griffin AC, Mendelson A. Discrimination hurts: The effect of discrimination on the development of chronic pain. National Institutes of Health. Published online 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.03.015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pyra M, Weber KM, Wilson TE, et al. Sexual Minority Women and Depressive Symptoms Throughout Adulthood. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(12):e83–e90. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Plöderl M, Tremblay P. Mental health of sexual minorities. A systematic review. International Review of Psychiatry. 2015;27(5):367–385. doi: 10.3109/09540261.2015.1083949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Przedworski JM, McAlpine DD, Karaca-Mandic P, VanKim NA. Health and Health Risks Among Sexual Minority Women: An Examination of 3 Subgroups. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(6):1045–1047. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thomeer MB. Sexual Minority Status and Self-Rated Health: The Importance of Socioeconomic Status, Age, and Sex. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(5):881–888. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Frost DM, Lehavot K, Meyer IH. Minority stress and physical health among sexual minority individuals. J Behav Med. 2015;38(1):1–8. doi: 10.1007/s10865-013-9523-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walker E, Katon W, Harrop-Griffiths J, Holm L, Russo J, Hickok LR. Relationship of chronic pelvic pain to psychiatric diagnoses and childhood sexual abuse. Am J Psychiatry. 1988;145(1):75–80. doi: 10.1176/ajp.145.1.75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Siqueira-Campos VM e Da Luz RA, de Deus JM Martinez EZ, Conde DM. Anxiety and depression in women with and without chronic pelvic pain: prevalence and associated factors. J Pain Res. 2019;12:1223–1233. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S195317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mereish EH, Poteat VP. A relational model of sexual minority mental and physical health: The negative effects of shame on relationships, loneliness, and health. J Couns Psychol. 2015;62(3):425–437. doi: 10.1037/cou0000088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Solé E, Racine M, Tomé-Pires C, Galán S, Jensen MP, Miró J. Social Factors, Disability, and Depressive Symptoms in Adults With Chronic Pain. The Clinical Journal of Pain. 2020;36(5):371–378. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0000000000000815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Andersen JP, Zou C, Blosnich J. Multiple early victimization experiences as a pathway to explain physical health disparities among sexual minority and heterosexual individuals. Social Science & Medicine. 2015;133:111–119. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.03.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Raphael KG, Widom CS, Lange G. Childhood victimization and pain in adulthood: a prospective investigation. Pain. 2001;92(1):283–293. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(01)00270-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hatzenbuehler ML. How Does Sexual Minority Stigma “Get Under the Skin”? A Psychological Mediation Framework. Psychol Bull. 2009;135(5):707–730. doi: 10.1037/a0016441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wardecker BM, Graham-Engeland JE, Almeida DM. Perceived discrimination predicts elevated biological markers of inflammation among sexual minority adults. J Behav Med. 2021;44(1):53–65. doi: 10.1007/s10865-020-00180-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Blair KL, Pukall CF, Smith KB, Cappell J. Differential associations of communication and love in heterosexual, lesbian, and bisexual women’s perceptions and experiences of chronic vulvar and pelvic pain. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy. 2015;41(5):498–524. doi: 10.1080/0092623X.2014.931315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Agénor M, Krieger N, Austin SB, Haneuse S, Gottlieb BR. Sexual Orientation Disparities in Papanicolaou Test Use Among US Women: The Role of Sexual and Reproductive Health Services. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(2):e68–e73. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Riskind RG, Tornello SL, Younger BC, Patterson CJ. Sexual Identity, Partner Gender, and Sexual Health Among Adolescent Girls in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(10):1957–1963. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bahamondes L, Petta CA, Fernandes A, Monteiro I. Use of the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system in women with endometriosis, chronic pelvic pain and dysmenorrhea. Contraception. 2007;75(6 SUPPL.):S134–S139. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2006.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Field AE, Camargo CA, Barr Taylor C, et al. Overweight, weight concerns, and bulimic behaviors among girls and boys. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1999;38(6):754–760. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199906000-00024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Remafedi G, Resnick M, Blum R, Harris L. Demography of sexual orientation in adolescents. Pediatrics. 1992;89(4):714–721. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Norman G Likert scales, levels of measurement and the “laws” of statistics. Advances in Health Sciences Education. 2010;15(5):625–632. doi: 10.1007/s10459-010-9222-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jamieson S Likert scales: How to (ab)use them. Medical Education. 2004;38(12):1217–1218. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2004.02012.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Flentje A, Heck NC, Brennan JM, Meyer IH. The relationship between minority stress and biological outcomes: A systematic review. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. Published online 2019. doi: 10.1007/s10865-019-00120-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Flanders CE, Anderson RE, Tarasoff LA, Robinson M. Bisexual Stigma, Sexual Violence, and Sexual Health Among Bisexual and Other Plurisexual Women: A Cross-Sectional Survey Study. The Journal of Sex Research. 2019;56(9):1115–1127. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2018.1563042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fry RPW, Crisp AH, Beard RW. Sociopsychological factors in chronic pelvic pain: A review. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 1997;42(1):1–15. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(96)00233-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dyar C, Feinstein BA, London B. Mediators of differences between lesbians and bisexual women in sexual identity and minority stress. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity. 2015;2(1):43–51. doi: 10.1037/sgd0000090 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Romão APMS, Gorayeb R, Romão GS, et al. High levels of anxiety and depression have a negative effect on quality of life of women with chronic pelvic pain. International Journal of Clinical Practice. 2009;63(5):707–711. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2009.02034.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tabaac AR, Benotsch EG, Barnes AJ. Mediation models of perceived medical heterosexism, provider-patient relationship quality, and cervical cancer screening in a community sample of sexual minority women and gender nonbinary adults. LGBT Health. 2019;6(2):77–86. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2018.0203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Everett BG, Higgins JA, Haider S, Carpenter E. Do Sexual Minorities Receive Appropriate Sexual and Reproductive Health Care and Counseling? Journal of Women’s Health. 2019;28(1):53–62. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2017.6866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nicola M, Correia H, Ditchburn G, Drummond P. Invalidation of chronic pain: a thematic analysis of pain narratives. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2021;43(6):861–869. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2019.1636888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hegarty D, Wall M. Prevalence and relationship between self-stigmatization and self-esteem in chronic pain patients. British Journal of Pain. 2014;3(2):136. doi: 10.4172/2167-0846.1000136 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nguyen RHN, Turner RM, Rydell SA, MacLehose RF, Harlow BL. Perceived Stereotyping and Seeking Care for Chronic Vulvar Pain. Pain Medicine. 2013;14(10):1461–1467. doi: 10.1111/pme.12151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McGowan L, Luker K, Creed F, Chew-Graham CA. ‘How do you explain a pain that can’t be seen?’: The narratives of women with chronic pelvic pain and their disengagement with the diagnostic cycle. British Journal of Health Psychology. 2007;12(2):261–274. doi: 10.1348/135910706X104076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Seear K The etiquette of endometriosis: Stigmatisation, menstrual concealment and the diagnostic delay. Social Science & Medicine. 2009;69(8):1220–1227. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.07.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zondervan KT, Yudkin PL, Vessey MP, Dawes MG, Barlow DH, Kennedy SH. Patterns of diagnosis and referral in women consulting for chronic pelvic pain in UK primary care. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1999;106(11):1156–1161. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1999.tb08141.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fuldeore M, Yang H, Du EX, Soliman AM, Wu EQ, Winkel C. Healthcare utilization and costs in women diagnosed with endometriosis before and after diagnosis: A longitudinal analysis of claims databases. Fertility and Sterility. 2015;103(1):163–171. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.10.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Figueroa WS, Zoccola PM. Sources of Discrimination and Their Associations With Health in Sexual Minority Adults. Journal of Homosexuality. 2016;63(6):743–763. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2015.1112193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Eliason MJ, Martinson M, Carabez RM. Disability Among Sexual Minority Women: Descriptive Data from an Invisible Population. LGBT Health. 2015;2(2):113–120. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2014.0091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nagata JM, Ganson KT, Tabler J, Blashill AJ, Murray SB. Disparities Across Sexual Orientation in Migraine Among US Adults. JAMA Neurol. 2021;78(1):117. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.3406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lukas I, Kohl-Schwartz A, Geraedts K, et al. Satisfaction with medical support in women with endometriosis. Erbil N, ed. PLOS ONE. 2018;13(11):e0208023. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0208023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li AD, Bellis EK, Girling JE, et al. Unmet Needs and Experiences of Adolescent Girls with Heavy Menstrual Bleeding and Dysmenorrhea: A Qualitative Study. Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology. 2020;33(3):278–284. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2019.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Scott KD, Hintz EA, Harris TM. “Having Pain is Normal”: How Talk about Chronic Pelvic and Genital Pain Reflects Messages from Menarche. Health Communication. Published online 2020. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2020.1837464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lamvu G, Antunez-Flores O, Orady M, Schneider B. Path to diagnosis and women’s perspectives on the impact of endometriosis pain. Journal of Endometriosis and Pelvic Pain Disorders. 2020;12(1):16–25. doi: 10.1177/2284026520903214 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ballard K, Lowton K, Wright J. What’s the delay? A qualitative study of women’s experiences of reaching a diagnosis of endometriosis. Fertility and Sterility. 2006;86(5):1296–1301. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.04.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kuzma EK, Pardee M, Darling-Fisher CS. Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender health: Creating safe spaces and caring for patients with cultural humility. Journal of the American Association of Nurse Practitioners. 2019;31(3):167–174. doi: 10.1097/JXX.0000000000000131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.