Abstract

MicroAbstract:

Serum albumin in cancer patients is associated with clinical outcomes. In a single-center retrospective study of 210 advanced NSCLC patients receiving immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) with or without chemotherapy as first-line therapy, we found a significant association of overall survival with pretreatment albumin and early albumin decrease in treatment with ICI monotherapy but not with chemoimmunotherapy.

Background:

Cancer cachexia exhibits decreased albumin and associates with short overall survival (OS) in patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), but whether on-treatment albumin changes associate with OS in NSCLC patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) and combination chemoimmunotherapy has not been thoroughly evaluated.

Patients and Methods:

We conducted a single-center retrospective study of patients with advanced NSCLC who received first-line ICI with or without chemotherapy between 2013 and 2020. The association of pretreatment albumin and early albumin changes with OS was evaluated using Kaplan-Meier method and Cox regression models.

Results:

A total of 210 patients were included: 109 in ICI cohort and 101 in ICI+Chemo cohort. Within a median of 21 days from treatment initiation, patients with ≥10% of albumin decrease had significantly shorter OS compared to patients without albumin decrease in ICI cohort. Pretreatment albumin and albumin decrease within the first or second cycle of treatment were significantly and independently associated with OS in ICI cohort, but not in ICI+Chemo cohort. The lack of association between albumin and OS with the addition of chemotherapy was more pronounced among patients with ≥ 1% PD-L1 expression in subgroup analysis.

Conclusion:

Pretreatment serum albumin and early albumin decrease in ICI monotherapy was significantly associated with OS in advanced NSCLC. Early albumin change, as a routine lab value tested in clinic, may be combined with established biomarkers to improve outcome predictions of ICI monotherapy. The underlying mechanism of the observed association between decreased albumin and ICI resistance warrants further investigation.

Keywords: immune checkpoint inhibitor, albumin, biomarker, NSCLC, cancer cachexia

Introduction

Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) accounts for around 85% of all lung cancers and more than half of the patients with NSCLC have metastatic disease at the time of diagnosis1. The current first-line standard of care for patients with metastatic NSCLC lacking driver mutations is immune-checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) alone or combined with concurrent chemotherapy2–4. ICIs are highly potent anticancer agents which alleviate the downregulation of T cell function and can restore the immune system to kill cancer cells by blocking the interaction between checkpoint proteins and their ligands5. However, only a small portion of patients respond to this therapy despite the use of tumor expression of PD-L1 as an established biomarker6, and mechanisms of resistance to ICI therapy are not well understood. It therefore remains a priority to identify biomarkers that can predict benefit or early failure with ICI therapy so that earlier therapeutic decisions can be made.

Serum albumin has broadly been viewed as a useful biomarker for general health and disease burden. In patients with malignancies such as NSCLC, melanoma, and renal cell carcinoma, pretreatment serum albumin is commonly studied alone or in combination with other lab values, such as C-reactive protein, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), body mass index (BMI), and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), as a biomarker for pretreatment nutrition and systemic inflammation status and to predict disease prognosis7–10. In other disease conditions such as heart failure, infections, and inflammatory bowel disease11–14, hypoalbuminemia has also been studied as a negative predictor of treatment outcome due to its potential relationship with decreased host immune response and high inflammatory burden. Moreover, in patients who receive systemic treatment with chemotherapies15, 16, ICIs17–19, and tyrosine kinase inhibitors20, 21, it has also been identified that a low pretreatment albumin is associated with poor treatment response and increased risk of treatment-related toxicities. Notably, hypoalbuminemia in cancer and other diseases is generally accepted as being due to increased turnover relative to an inflammatory state, and is less likely due to poor nutritional status, decreased synthesis or protein loss through excretion22–28.

In addition to albumin’s use as a broad marker for general health, disease status, and treatment response, serum albumin is one of the most commonly identified covariates on IgG-based antibody drug clearance, therefore it has unique value as a biomarker in antibody drug therapy. Population pharmacokinetic analyses have demonstrated that elevated clearance of monoclonal antibodies is correlated with low pretreatment albumin across many antibody drugs and across many diseases29–39. Furthermore, it was found in recent years that the clearance of ICIs changed over time in patients with advanced cancers, where the variation of ICI clearance post treatment initiation can be driven by longitudinal markers, such as albumin, LDH, lymphocyte count, and tumor size34–37. Although the exact mechanism of this observed association is unclear, it may relate to common IgG and albumin catabolic clearance and salvage pathways, as albumin synthesis rates are not decreased in patients with cancer-associated cachexia and hypoalbuminemia24, 38.

Cachexia, which is a multifactorial syndrome defined by involuntary weight loss of ≥ 5% that cannot be reversed with nutritional support, is relatively common in cancer patients40–42. The association between cancer cachexia, ICI clearance and OS has been investigated in preclinical and clinical studies. Turner et al. found that patients with rapid clearance of pembrolizumab often exhibited clinical features of cancer cachexia, such as excessive weight loss and albumin decrease, and the rapid clearance was associated with short OS in both patients with advanced melanoma and NSCLC43. Castillo and Vu et al. recently described the pharmacokinetics of pembrolizumab in preclinical cancer cachexia mouse models, confirmed decreased albumin in these models as published in prior studies, and replicated the human clinical observations of cachexia-associated elevations in catabolic clearance of pembrolizumab44. These studies have revealed the interactions between cancer cachexia, ICI clearance, and decreased albumin, highlighting albumin changes after ICI treatment initiation may reflect the complex interactions and predict benefit from ICIs.

In summary, early albumin change after treatment initiation could potentially predict benefit from ICIs due to its association with on-treatment progression of disease burden as well as cancer cachexia. Since albumin is a readily available and a cost-effective marker routinely obtained in the clinic, it is of interest to conduct further investigations.

The objective of this study was to evaluate the association of early changes in albumin with OS in patients with advanced NSCLC who received ICI alone or in combination with chemotherapy as first-line treatment. We hypothesized that early changes in albumin would be associated with OS in patients with NSCLC treated with ICIs.

Patients and Methods

A retrospective review was performed at The Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center under two IRB-approved protocols (IRB 2016C0070 and 2018C0177) enrolling patients with stage IV NSCLC who received at least one dose of an ICI with or without chemotherapy either as a part of a clinical trial or standard of care therapy from February 2013 to February 2020. Patient characteristics, including age, gender, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status (ECOG PS)45 at time of ICI, smoking history, histology, and tumor PD-L1 expression by tumor proportion score, were collected from electronic medical records. Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) was used for data collection46. Laboratory values, including NLR, platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR), and LDH, were obtained along with albumin because they were frequently reported prognostic biomarkers of ICI treatment outcomes47–50. Two sets of laboratory measurements, pretreatment and on-treatment, were obtained for each patient. Pretreatment values were measured at the date of first ICI dose, while on-treatment values were measured during the first laboratory testing following treatment initiation (typically prior to the second dose of ICI). To evaluate the association of early changes in those serum-based biomarkers and treatment outcome, patients with on-treatment laboratory testing performed less than 7 days or more than 90 days since treatment initiation were excluded. OS was evaluated as the treatment outcome.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize patient demographics and clinical characteristics. OS was calculated from the date of ICI initiation to death of any cause. Patients were censored at date of last follow-up if patients were still alive. Albumin was categorized as low or normal using the cutoff of 3.5 g/dL, which was commonly used in previous studies50, 51. Continuous NLR, PLR, and LDH were normalized with log-transformation. Missing lab values were imputed with the median value of the patient’s corresponding treatment group. The association of categorical albumin levels with OS was evaluated using log-rank test in Kaplan-Meier survival analysis. Categorical relative albumin change, continuous lab values, along with other baseline characteristics, were evaluated in univariate Cox regression analysis. Variables with p < 0.1 in univariate analysis were included in multivariable Cox proportional-hazards model and then backward eliminated until no further variables could be eliminated without significant loss of model fit (p < 0.05). Collinearity of each independent variable included in multivariable model was evaluated by variance inflation factor (VIF). Variables with VIF > 5 were deemed as variables with high collinearity and were sequentially excluded. All other statistical tests were 2-sided with statistical significance defined as p < 0.05. Statistics analysis was performed with R version 4.0.3.

Results

Demographics and clinical characteristics

A total of 210 patients with stage IV NSCLC were included with baseline characteristics listed in Table 1. The median age at treatment initiation was 63 years (range, 55–71 years). Most of the patients were current or previous smokers, with an ECOG PS of 0–1, and with non-squamous NSCLC. The distributions of gender, smoking history, and histology were generally balanced between treatment groups, but the ICI group was significantly older (median age 65 vs. 61, p = 0.003) and had fewer patients with ECOG PS 0–1 (68.8% vs. 86.1%, p = 0.003).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| All (n=210) | ICI (n=109) | ICI + Chemo (n=101) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at the time of ICI therapy, years, median (range) | 63 (55 – 71) | 65 (39 – 92) | 61 (30 – 79) |

| Male, n (%) | 120 (57.1%) | 67 (61.5%) | 53 (52.5%) |

| Current or former smoker, n (%) | 192 (91.4%) | 103 (94.5%) | 89 (88.1%) |

| ECOG PS 0–1, n (%) | 162 (77.1%) | 75 (68.8%) | 87 (86.1%) |

| Non-squamous cell, n (%) | 161 (76.7%) | 80 (73.4%) | 81 (80.2%) |

| ICI as part of clinical trial, n (%) | 11 (5.4%) | 11 (10.7%)* | 0 (0.0%) |

| ICI start after 2017, n (%) | 176 (83.8%) | 75 (68.8%) | 101 (100.0%) |

| PD-L1 expression, n (%)** | |||

| ≥ 50% | 93 (48.9%) | 80 (87.0%) | 13 (13.3%) |

| < 50% | 43 (22.6%) | 9 (9.78%) | 34 (34.7%) |

| No expression | 54 (28.4%) | 3 (3.26%) | 51 (52.0%) |

| Pretreatment albumin, n (%) | |||

| Normal (≥ 3.5 g/dL) | 152 (72.4%) | 73 (67.0%) | 79 (78.2%) |

| Low (< 3.5 g/dL) | 58 (27.6%) | 36 (33.0%) | 22 (21.8%) |

| On-treatment albumin, n (%) | |||

| Normal (≥ 3.5 g/dL) | 156 (74.3%) | 80 (73.4%) | 76 (75.2%) |

| Low (< 3.5 g/dL) | 54 (25.7%) | 29 (26.6%) | 25 (24.8%) |

| Percentage change of albumin from pretreatment, n (%) | |||

| < −10% | 25 (11.9%) | 11 (10.1%) | 14 (13.9%) |

| < −5% and ≥ −10% | 35 (16.7%) | 22 (20.2%) | 13 (12.9%) |

| < 0% and ≥ −5% | 35 (16.7%) | 18 (16.5%) | 17 (16.8%) |

| ≥ 0% | 115 (54.8%) | 58 (53.2%) | 57 (56.4%) |

6 missing values

17 missing values in ICI group:12 patients with known PD-L1 expression but missed TPS value, 5 patients with missed PD-L1 expression status; 3 missing PD-L1 expression status in ICI+chemo group

Most of the patients (94.6%) received treatment as the standard of care. There were 109 patients who received ICI monotherapy including 90 patients who received pembrolizumab 200 mg every 3 weeks and 19 who received nivolumab 3 mg/kg every 2 weeks. All 101 patients treated with chemoimmunotherapy received pembrolizumab 200 mg every 3 weeks plus chemotherapy; 79 patients were treated with platinum and pemetrexed, and 22 patients received platinum and paclitaxel. A bias in treatment selection based on PD-L1 expression did exist in this study as 87% of patients in ICI group had PD-L1 expression ≥ 50%, while 52% of patients receiving chemoimmunotherapy were negative for PD-L1 expression. This was in line with clinical practice where patients with high PD-L1 expression are often treated with ICIs alone, while patients with low or no PD-L1 expression are likely to be offered treatment with chemoimmunotherapy4. Overall, the frequency of patients with tumors negative for PD-L1 expression was 28.4% in the entire cohort.

The duration of follow-up, duration of treatment, and mortality rate were balanced between treatment groups as shown in Table 2. The median OS for patients who received ICI alone (29.9 months, CI 95% 12.3-not reached) or with chemotherapy (20.9 months, CI 95% 14.3-not reached) were not significantly different (p = 0.63), and were similar to the results from a recent meta-analysis52 (Fig. A. 1).

Table 2.

Time and events

| All (n=210) | ICI (n=109) | ICI + Chemo (n=101) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of deaths n (%) | 102 (48.6%) | 52 (47.7%) | 50 (49.5%) |

| Duration of follow-up, months median (IQR) | 12.1 (6.96, 24.8) | 11.6 (6.93, 27.9) | 13.5 (7.23, 23.0) |

| Duration of therapy, months median (IQR) | 8.37 (2.83, 15.9) | 8.1 (2.07, 16.4) | 8.4 (4.17, 15.3) |

| Time between labs, days median (IQR) | 21 (21, 21) | 21 (19, 21) | 21 (21, 21) |

IQR, interquartile range (25th, 75th percentiles)

Ninety-nine percent of patients had documented on-treatment lab results within the first or second cycle of treatment. The median and interquartile range (IQR) of pretreatment and on-treatment laboratory values are summarized in Table 3. The fraction of pretreatment and on-treatment LDH that was missing and imputed were 17.1% and 37.1%, respectively. All other lab values were imputed at a level less than or equal to 4.29%. Pretreatment hypoalbuminemia occurred in 33.0% and 21.8% of patients in ICI and ICI+Chemo cohort (Table 1). Among patients who had normal pretreatment albumin, 9.59% (7/73) and 13.9% (11/79) had a more than 10% albumin decrease in ICI and ICI+chemo cohorts, respectively; for patients with low pretreatment albumin, it was 11.1% (4/36) and 13.6% (3/22) in ICI and ICI+Chemo cohorts. Pretreatment albumin and on-treatment albumin were both significantly higher in ICI+Chemo cohort compared with ICI cohort (pretreatment p = 0.013; on-treatment p = 0.017), but the percentage change of albumin was balanced between two cohorts (p = 0.761). Furthermore, the number of patients in each albumin category was balanced between ICI and ICI+Chemo cohort, as no significant difference was found using Chi-squared test (pretreatment albumin, p = 0.096; on-treatment albumin, p = 0.882; albumin change, p = 0.492).

Table 3.

Pretreatment and on-treatment laboratory measurements

| All (n = 210) | ICI (n=109) | ICI + Chemo (n=101) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pretreatment albumin, g/dL median (IQR) | 3.70 (3.40, 4.00) | 3.70 (3.30, 4.0) | 3.90 (3.60, 4.10) |

| missing, n (%) | 3 (1.43%) | 2 (1.83%) | 1 (0.990%) |

| On-treatment albumin, g/dL median (IQR) | 3.70 (3.40, 4.00) | 3.60 (3.40, 3.90) | 3.80 (3.45, 4.05) |

| missing, n (%) | 9 (4.29%) | 7 (6.42%) | 2 (1.98%) |

| Albumin percentage change, % median (IQR) | 0.00 (−5.37, 3.03) | 0.00 (−5.40, 3.30) | 0.00 (−5.13, 2.94) |

| Pretreatment NLR median (IQR) | 6.18 (3.47, 12.1) | 5.04 (3.06, 9.94) | 7.19 (4.53, 12.7) |

| missing, n (%) | 2 (0.952%) | 1 (0.917%) | 1 (0.990%) |

| On-treatment NLR median (IQR) | 4.68 (2.87, 7.80) | 4.64 (2.84, 7.80) | 4.77 (2.91, 7.80) |

| missing, n (%) | 1 (0.476%) | 1 (0.917%) | 0 |

| Pretreatment LDH, U/L median (IQR) | 231 (181, 259) | 206 (171, 246) | 243 (209, 279) |

| missing, n (%) | 36 (17.1%) | 7 (6.42%) | 29 (28.7%) |

| On-treatment LDH, U/L median (IQR) | 212 (199, 239) | 199 (193, 210) | 239 (216, 277) |

| missing, n (%) | 78 (37.1%) | 47 (43.1%) | 31 (30.7%) |

| Pretreatment PLR median (IQR) | 246 (163, 390) | 243 (149, 367) | 248 (168, 433) |

| missing, n (%) | 2 (0.952%) | 1 (0.917%) | 1 (0.990%) |

| On-treatment PLR median (IQR) | 277 (170, 413) | 261 (166, 337) | 303 (180, 444) |

| missing, n (%) | 1 (0.476%) | 1 (0.917%) | 0 |

Association of pretreatment and on-treatment albumin with OS

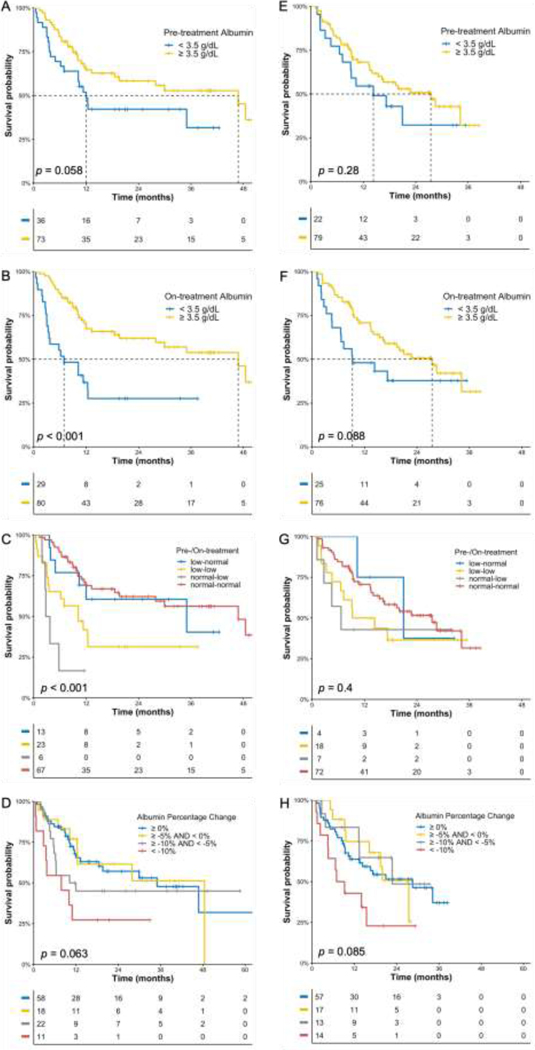

The associations of OS with categorial and continuous albumin levels were investigated. In survival analysis, albumin was categorized at the cut-off level of 3.5 g/dL. Categorical pretreatment albumin was not significantly associated with OS in both ICI and ICI+Chemo cohorts (Fig. 1A and 2E), potentially due to lack of specificity at the cut-off level of 3.5 g/dL. For categorical on-treatment albumin, its association with OS was significant in ICI cohort (Fig. 1B) but not in ICI+Chemo cohort (Fig. 1F).

Fig 1.

Kaplan-Meier OS curves in ICI cohort (A-D) and ICI+Chemo cohort (E-H). A, E) Patients stratified according to pretreatment albumin. B, F) Patients stratified according to on-treatment albumin. C, G) Patients stratified according to pretreatment and on-treatment albumin. D, H) Patients stratified according to percentage change of albumin from pretreatment.

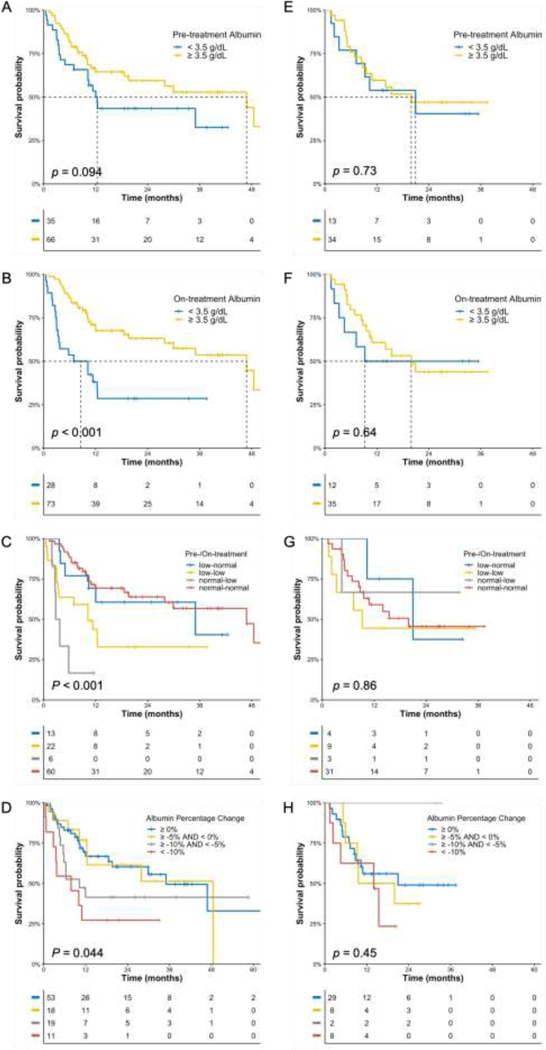

Fig 2.

Kaplan-Meier OS curves in ICI cohort (A-D) and ICI+Chemo cohort (E-H) in patients with PD-L1 positive tumors. A, E) Patients stratified according to pretreatment albumin. B, F) Patients stratified according to on-treatment albumin. C, G) Patients stratified according to pretreatment and on-treatment albumin. D, H) Patients stratified according to percentage change of albumin from pretreatment.

In cox proportional regression analysis, pretreatment albumin as a continuous value was significantly associated with OS in ICI cohort (Table 4, univariate HR 0.33, p = 0.001), but not in ICI+Chemo cohort (Table 5, univariate HR 0.72, p=0.253), indicating that the association of pretreatment albumin with OS was unique to ICI monotherapy. However, the association of on-treatment albumin with OS was significant, regardless of treatment (ICI, univariate HR 0.19, p<0.001; ICI+Chemo, univariate HR 0.37, p=0.012).

Table 4.

Cox regression analysis on OS in ICI cohort.

| Variables | Hazard Ratio (95% CI, p-value) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate | Multivariable | ||

| Age | 1.02 (1.00–1.05, p=0.047) | 1.01 (0.99–1.04, p=0.321) | |

| ECOG PS | 0–1 | Ref | Ref |

| ≥2 | 1.73 (0.95–3.15, p=0.073) | 1.29 (0.68–2.45, p=0.445) | |

| Gender | Male | Ref | |

| Female | 0.65 (0.36–1.18, p=0.158) | ||

| Smoking status | Non-smoker | Ref | |

| Smoker | 0.90 (0.28–2.92, p=0.867) | ||

| Clinical trial | No | Ref | |

| Yes | 1.29 (0.57–2.94, p=0.545) | ||

| Histology | Non-squamous | Ref | |

| Squamous | 1.59 (0.90–2.82, p=0.112) | ||

| PD-L1 expression | ≥ 50% | Ref | |

| 1–49% | 1.62 (0.63–4.18, p=0.321) | ||

| No expression | 0.70 (0.10–5.12, p=0.725) | ||

| Pretreatment albumin | 0.33 (0.16–0.65, p=0.001) | 0.30 (0.13–0.71, p=0.006) | |

| On-treatment albumin * | 0.19 (0.09–0.39, p<0.001) | ||

| Albumin change | ≥ 0% | Ref | Ref |

| −5% – 0% | 1.00 (0.45–2.22, p=0.994) | 1.41 (0.61–3.23, p=0.422) | |

| −10% – −5% | 1.36 (0.68–2.74, p=0.384) | 2.65 (1.17–6.00, p=0.019) | |

| < −10% | 2.79 (1.25–6.23, p=0.012) | 3.95 (1.60–9.74, p=0.003) | |

| Pretreatment NLR | 1.64 (1.25–2.16, p<0.001)| | 0.88 (0.52–1.49, p=0.637) | |

| On-treatment NLR | 2.80 (1.90–4.11, p<0.001)) | 4.86 (2.19–10.76, p<0.001) | |

| Pretreatment LDH | 0.89 (0.40–1.98, p=0.768) | ||

| On-treatment LDH | 2.22 (0.84–5.87, p=0.107) | ||

| Pretreatment PLR * | 1.81 (1.25–2.62, p=0.002)) | ||

| On-treatment PLR | 2.44 (1.46–4.08, p=0.001) | 0.36 (0.14–0.94, p=0.036) | |

Excluded in multivariable analysis due to collinearity

Table 5.

Cox regression analysis on OS in ICI+Chemo cohort.

| Variables | Hazard Ratio (95% CI, p-value) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate | Multivariable | ||

| Age | 1.02 (0.99–1.05, p=0.212) | ||

| ECOG PS | 0–1 | Ref | Ref |

| ≥2 | 2.33 (1.16–4.68, p=0.017) | 1.69 (0.78–3.66, p=0.185) | |

| Gender | Male | Ref | |

| Female | 0.77 (0.44–1.36, p=0.376) | ||

| Smoking status | Non-smoker | Ref | |

| Smoker | 0.96 (0.41–2.26, p=0.925) | ||

| Histology | Non-squamous | Ref | |

| Squamous | 1.55 (0.78–3.05, p=0.208) | ||

| PD-L1 expression | ≥ 50% | Ref | |

| 1–49% | 1.90 (0.70–5.14, p=0.204) | ||

| No expression | 1.43 (0.55–3.75, p=0.462) | ||

| Pretreatment albumin | 0.72 (0.41–1.27, p=0.253) | ||

| On-treatment albumin * | 0.53 (0.30–0.93, p=0.026) | ||

| Albumin change | ≥ 0% | Ref | |

| −5% – 0% | 0.93 (0.42–2.06, p=0.856) | 0.91 (0.41–2.04, p=0.827) | |

| −10% – −5% | 0.79 (0.30–2.05, p=0.627) | 0.87 (0.32–2.33, p=0.774) | |

| < −10% | 2.29 (1.10–4.77, p=0.027) | 1.96 (0.90–4.26, p=0.088) | |

| Pretreatment NLR | 1.08 (0.75–1.54, p=0.675) | ||

| On-treatment NLR | 1.50 (1.02–2.22, p=0.041) | 1.36 (0.90–2.07, p=0.142) | |

| Pretreatment LDH | 1.79 (0.87–3.70, p=0.116) | ||

| On-treatment LDH | 2.26 (0.96–5.30, p=0.062) | 2.02 (0.80–5.11, p=0.139) | |

| Pretreatment PLR | 1.31 (0.89–1.92, p=0.176) | ||

| On-treatment PLR | 1.35 (0.89–2.04, p=0.159) | ||

Excluded in multivariable analysis due to collinearity

Association of early albumin changes with OS

Patients were divided into four different groups based on their pretreatment and on-treatment albumin categories. As depicted in Fig. 1C and 1G, the association of early albumin change with OS was significant in ICI monotherapy but not in ICI+Chemo. In both cohorts, patients whose albumin was normal at pretreatment but decreased to less than 3.5 g/dL early in the treatment had the shortest median OS, followed by patients with consistently low albumin. The survival curves for patients in “normal-low” and “low-low” category were separated in ICI cohort, but in ICI+Chemo cohort the curves crossed-over at around 18 months. The one-year OS rate for patients in “low-normal” category was similar in ICI and ICI+Chemo chort (69.2% and 75.0%, respectively). However, among patients in “normal-low” category, the one-year OS rate was much lower in ICI cohort than in ICI+Chemo cohort (16.7% and 42.9%, respectively).

Association of early albumin decreases with OS

To further investigate the association of albumin decrease with OS, the relative change of albumin from pretreatment was evaluated. Patients were divided into four different groups at the cutoffs of 10%, 5%, and 0% decrease. Although survival analysis (Fig. 1D and 1H) did not indicate significant association of albumin relative change with OS in both cohorts, median one-year OS rate was lower in ICI cohort for patients with > 10% of albumin decrease (27.3% and 42.9% in ICI and ICI+Chemo cohort, respectively) as well as patients with 5–10% of decrease (45.0% and 83.3% in ICI and ICI+Chemo cohort, respectively), signaling that benefit from ICI monotherapy may be hindered in patients with more than 5% albumin decrease early in treatment.

Cox regression analysis demonstrated that the association of albumin decrease with OS was only significant in the ICI monotherapy cohort. As listed in Table 4, the adjusted hazard ratios (HR) of patients with albumin decrease of > 10% and 5–10% were significantly higher than those without albumin decrease in the multivariable model. Additionally, the HR for decrease > 10% group was higher than that for decrease within 5–10% group, demonstrating a trend of shorter OS with greater albumin decrease post-treatment initiation. After backward elimination, only pretreatment albumin, albumin change, on-treatment NLR, and on-treatment PLR remained significant in the model. In contrast, none of the adjusted HRs in multivariable model remained significant in ICI+Chemo cohort (Table 5), suggesting addition of chemotherapy to ICI disrupted the significant association of early albumin decrease with OS.

Subgroup analysis of patients with ≥ 1% PD-L1 expression

Since pembrolizumab monotherapy and pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy have both been approved by the FDA as the first-line therapy in advanced NSCLC patients whose tumors are positive (≥ 1%) for PD-L1 expression, the association of OS with pretreatment albumin, on-treatment albumin, and albumin decrease were further studied in this group of patients. Patients having ≥ 1% PD-L1 expression included 101 patients in the ICI cohort and 47 patients in the ICI+Chemo cohort. OS was not significantly different between two cohorts (Fig.A.2). As shown in Fig 3, categorical pretreatment albumin, on-treatment albumin, and relative albumin change were significantly associated with OS for the ICI cohort but not for the ICI+Chemo cohort. The result was confirmed in Cox regression analysis (Table.A.2) that none of the albumin variables were significant in the ICI+Chemo cohort.

Discussion

Here we report the significant association of pretreatment albumin and early albumin decrease with overall survival in patients with advanced NSCLC who received ICI monotherapy, but not for those treated with chemoimmunotherapy.

Although pretreatment albumin is generally viewed as a prognostic factor across multiple treatment modalities, results from this study suggest that pretreatment albumin might not be a reliable biomarker for chemoimmunotherapy. A similar result was reported previously in a multi-center retrospective study by Mountzios et al. In this study, the association of advanced lung cancer inflammation index (ALI) with outcome from ICI treatment was evaluated in advanced NSCLC10. The authors found that the association of pretreatment ALI with OS, objective response rate, and time-on-treatment was significant in ICI monotherapy, but not in chemoimmunotherapy. Notably, ALI takes into consideration pretreatment BMI, albumin, and NLR, two of which were evaluated in our study where no significant association was found with OS in the ICI+Chemo cohort.

The observed unique association of OS with early albumin decreases in ICI monotherapy is supported by several recent studies. In a retrospective study by Jiang et al, serum albumin at pretreatment and 6-weeks post treatment initiation was evaluated among 29 patients who received ICI monotherapy and 6 patients who received sorafenib as first-line therapy for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma53. The authors found that albumin decrease was significant in patients who progressed on ICI at week 6 but not among patients who progressed on sorafenib, suggesting a unique association of albumin decrease with ICI response. In another retrospective multi-center study by Lenci, et al, researchers investigated the Gustave Roussy Immune (GRIm)-Score in advanced NSCLC patients with ≥ 50% PD-L1 expression treated with first-line pembrolizumab or with chemotherapy9. The study found that 45-day post treatment GRIm (GRImT1) and change of GRIm-Score from pretreatment (GRImΔ) were significantly associated with OS and PFS in the pembrolizumab cohort but not in the chemotherapy cohort. Notably, most of the patients with negative GRImΔ (increase of GRIm from pretreatment) in the pembrolizumab cohort did not show an objective response, demonstrating the value of GRImΔ as an early biomarker to identify advanced NSCLC patients with ≥ 50% PD-L1 expression who may benefit from pembrolizumab monotherapy. Since a negative GRImΔ could be due to NLR increase, LDH increase, and/or albumin decrease, the result from this study might also imply the value of albumin decrease in ICI monotherapy. Notably, on-treatment NLR was also significantly associated with OS in the current study and was independent of pretreatment albumin and albumin decrease in patients who were treatment with ICI monotherapy. Therefore, establishing a holistic model incorporating pretreatment albumin, early on-treatment NLR, early albumin changes, and other early biomarkers may better inform outcomes predictions and early decision-making with ICI monotherapy after only one or two cycles of treatment.

The mechanisms underlying the association of albumin decreases and worse ICI treatment outcome in patients with cancer are likely multifactorial. Decreased albumin can be an indicator of deteriorating health condition in patients with advanced cancers, as albumin is a marker of general health. Disease may have advanced too far for ICIs to be effective or activate the desired T-cell response by the time the first or second dose is administered. However, cancer cachexia may also be a contributing factor due to its associated excessive catabolism of proteins40, such as albumin, and its association with poor outcomes, which has been found in ICIs54, 55 and many other therapies56–58. Meanwhile, prior studies have shown that cancer cachexia and decreased albumin also correlate with increased ICI clearance. Since the clearance of other therapies, such as chemotherapy and tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI), have not been demonstrated to be affected by the hypercatabolic state in cancer cachexia, the elevation of ICI clearance, reflecting the progression of cancer cachexia, may partially explain the unique association of albumin decrease and poor outcome in ICI monotherapy, which was not replicated in this study when chemotherapy was added. Such hypothesis was supported by a multicenter retrospective study showing no significant difference in OS between cachexia and non-cachexia groups in patients with NSCLC who received chemoimmunotherapy60. However, this remains to be tested in prospective studies. Other potential mechanisms may coexist with the above factors and also warrant further investigations in future.

Although these findings are encouraging, we acknowledge there are several limitations of this study. First, causality between albumin changes and ICI therapy outcome cannot be inferred due to the retrospective nature of the study. Next, only anti-PD1 inhibitor and its combination chemoimmunotherapy were evaluated in this study. Therefore, whether the association of albumin decrease and OS exists in patients who are treated with other immune checkpoint inhibitors (PD-L1 or CTLA-4 inhibitors), other monoclonal antibodies, or other therapies, such as chemotherapy or TKIs, cannot be tested in current study. Meanwhile, missing laboratory values were imputed with median values to avoid losing sample size in multivariable analysis, which may bias the result. Most of the missing values imputed were pretreatment and on-treatment LDH, where 17.1% pretreatment and 37.1% on-treatment, missing LDH values were imputed with median value in the corresponding cohort. Therefore, the association of LDH with OS was likely dampened in this study. Besides, although tumor PD-L1 expression was not significantly associated with survival in the entire population or for each treatment modality, the selection bias for treatment based on PD-L1 limits our ability to independently study PD-L1 or incorporate it into these analyses. Moreover, this was a single-center study with approximately 100 patients in each treatment cohort. The analysis may have missed the statistical significance of some independent variables evaluated in this study due to limited patient numbers. Caution should also be taken when extrapolating the study results to dual ICI regimens since nivolumab combined with ipilimumab has also been approved as first-line therapy for metastatic NSCLC59. Lastly, only OS was evaluated in this study because limited data were available to evaluate other treatment outcomes such as tumor progression and immune-related adverse events. Therefore, the association of albumin changes with other treatment outcomes needs to be further investigated.

Conclusion

In conclusion, pretreatment serum albumin and early albumin decreases during ICI treatment were strongly associated with OS in patients with advanced NSCLC treated with ICI monotherapy, but not in patients treated with chemoimmunotherapy. Preclinical and clinical studies have revealed that decreases in albumin can inform the overall deterioration of health condition and hypermetabolic state in advanced cancer patients, as well as reflect complicated interactions between ICI clearance and cancer cachexia. The underlying mechanisms responsible for the observed associations with albumin in ICI monotherapy and lack of association when chemotherapy is added, warrants further investigation to improve therapy decisions and achieve maximum benefit in patients with NSCLC treated with ICI.

Supplementary Material

Clinical Practice Points.

Hypoalbuminemia has broadly been viewed as a marker for unfavorable treatment response in solid tumors across multiple treatment modalities, as well as poor health condition as in cancer-associated cachexia. In patients undergoing ICI treatment, decreases in albumin may also correspond to increase of ICI clearance, which has been demonstrated as a potential biomarker for outcomes from ICI therapy.

In this single-center retrospective study, we found that low pretreatment albumin and an albumin decrease from pretreatment of more than 10% within the first or second cycle of treatment were strongly associated with short overall survival (OS) in patients with advanced NSCLC treated with ICI monotherapy, but not in patients treated with chemoimmunotherapy.

Our result also showed that such lack of association between albumin and OS with the addition of chemotherapy was even more pronounced among patients with ≥ 1% PD-L1 expression.

Taken together, early serum albumin change can be incorporated into a holistic model, along with other early biomarkers to better inform outcomes predictions and early decision-making with ICI monotherapy.

Cancer cachexia may contribute to the association of albumin changes and ICI treatment outcome. However, the underlying mechanism of the observed association in ICI monotherapy but disconnected association in chemoimmunotherapy needs to be further investigated.

Acknowledgements

Research support provided by the REDCap project and The Ohio State University Center for Clinical and Translational Science grant support (National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Grant UL1TR002733). Dr. Owen is a Paul Calabresi Scholar supported by the OSU K12 Training Grant for Clinical Faculty Investigators (K12 CA133250)

Funding

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health P30CA016058 and K12 CA133250.

Footnotes

Ethics approval

This study was approved by Institutional Review Board at the Ohio State University (IRB Study ID #’s 2016C0070 and 2018C0177, PI: Dwight H. Owen, MD, MS).

Consent to participate

A waiver of consent was granted by the Institutional Review Board at the Ohio State University for this retrospective study.

Availability of data and material

In accordance with local and/or U.S. Government laws and regulations, any materials and de-identified data that are reasonably requested by others for the purposes of academic research will be made available in a timely fashion

Conflicts of interest/Competing interests

The authors report no conflicts or competing interests. Financial disclosures not directly relevant to the current work are provided separately.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70:7–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reck M, Rodriguez-Abreu D, Robinson AG, et al. Pembrolizumab versus Chemotherapy for PD-L1-Positive Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1823–1833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reck M, Rodriguez-Abreu D, Robinson AG, et al. Pembrolizumab versus Chemotherapy for PD-L1-Positive Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1823–1833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gandhi L, Rodriguez-Abreu D, Gadgeel S, et al. Pembrolizumab plus Chemotherapy in Metastatic Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:2078–2092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centanni M, Moes D, Troconiz IF, Ciccolini J, van Hasselt JGC. Clinical Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2019;58:835–857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jenkins RW, Barbie DA, Flaherty KT. Mechanisms of resistance to immune checkpoint inhibitors. Br J Cancer. 2018;118:9–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gupta D, Lis CG. Pretreatment serum albumin as a predictor of cancer survival: A systematic review of the epidemiological literature. Nutr J. 2010;9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shim SR, Kim SJ, Kim SI, Cho DS. Prognostic value of the Glasgow Prognostic Score in renal cell carcinoma: a meta-analysis. World J Urol. 2017;35:771–780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lenci E, Cantini L, Pecci F, et al. The Gustave Roussy Immune (GRIm)-Score Variation Is an Early-on-Treatment Biomarker of Outcome in Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC) Patients Treated with First-Line Pembrolizumab. J Clin Med. 2021;10:1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mountzios G, Samantas E, Senghas K, et al. Association of the advanced lung cancer inflammation index (ALI) with immune checkpoint inhibitor efficacy in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. ESMO open. 2021;6:100254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prenner SB, Kumar A, Zhao L, et al. Effect of Serum Albumin Levels in Patients With Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction (from the TOPCAT Trial). Am J Cardiol. 2020;125:575–582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wiedermann CJ. Hypoalbuminemia as Surrogate and Culprit of Infections. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jantti T, Tarvasmaki T, Harjola VP, et al. Hypoalbuminemia is a frequent marker of increased mortality in cardiogenic shock. Plos One. 2019;14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nguyen GC, Du L, Chong RY, Jackson TD. Hypoalbuminaemia and Postoperative Outcomes in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: the NSQIP Surgical Cohort. J Crohns Colitis. 2019;13:1433–1438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ikeda S, Yoshioka H, Ikeo S, et al. Serum albumin level as a potential marker for deciding chemotherapy or best supportive care in elderly, advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients with poor performance status. Bmc Cancer. 2017;17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arrieta O, Ortega RMM, Villanueva-Rodriguez G, et al. Association of nutritional status and serum albumin levels with development of toxicity in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer treated with paclitaxel-cisplatin chemotherapy: a prospective study. Bmc Cancer. 2010;10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Araki T, Tateishi K, Sonehara K, et al. Clinical utility of the C-reactive protein:albumin ratio in non-small cell lung cancer patients treated with nivolumab. Thorac Cancer. 2021;12:603–612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johannet P, Sawyers A, Qian YZ, et al. Baseline prognostic nutritional index and changes in pretreatment body mass index associate with immunotherapy response in patients with advanced cancer. J Immunother Cancer. 2020;8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kasahara N, Sunaga N, Tsukagoshi Y, et al. Post-treatment Glasgow Prognostic Score Predicts Efficacy in Advanced Non-small-cell Lung Cancer Treated With Anti-PD1. Anticancer Res. 2019;39:1455–1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cai W, Kong W, Dong BJ, et al. Pretreatment Serum Prealbumin as an Independent Prognostic Indicator in Patients With Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma Using Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors as First-Line Target Therapy. Clin Genitourin Canc. 2017;15:E437–E446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fiala O, Pesek M, Finek J, et al. Serum albumin is a strong predictor of survival in patients with advanced-stage non-small cell lung cancer treated with erlotinib. Neoplasma. 2016;63:471–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ishida S, Hashimoto I, Seike T, Abe Y, Nakaya Y, Nakanishi H. Serum albumin levels correlate with inflammation rather than nutrition supply in burns patients : a retrospective study. J Med Investig. 2014;61:361–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim S, McClave SA, Martindale RG, Miller KR, Hurt RT. Hypoalbuminemia and Clinical Outcomes: What is the Mechanism behind the Relationship? Am Surg. 2017;83:1220–1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Levitt DG, Levitt MD. Human serum albumin homeostasis: a new look at the roles of synthesis, catabolism, renal and gastrointestinal excretion, and the clinical value of serum albumin measurements. Int J Gen Med. 2016;9:229–255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mirsaeidi M, Omar HR, Sweiss N. Hypoalbuminemia is related to inflammation rather than malnutrition in sarcoidosis. Eur J Intern Med. 2018;53:E14–E16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee JL, Oh ES, Lee RW, Finucane TE. Serum Albumin and Prealbumin in Calorically Restricted, Nondiseased Individuals: A Systematic Review. Am J Med. 2015;128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Narayanan V, Gaudiani JL, Mehler PS. Serum albumin levels may not correlate with weight status in severe anorexia nervosa. Eat Disord. 2009;17:322–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fearon KC, Falconer JS, Slater C, McMillan DC, Ross JA, Preston T. Albumin synthesis rates are not decreased in hypoalbuminemic cachectic cancer patients with an ongoing acute-phase protein response. Annals of surgery. 1998;227:249–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bauman LE, Xiong Y, Mizuno T, et al. Improved Population Pharmacokinetic Model for Predicting Optimized Infliximab Exposure in Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2020;26:429–439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garg A, Quartino A, Li J, et al. Population pharmacokinetic and covariate analysis of pertuzumab, a HER2-targeted monoclonal antibody, and evaluation of a fixed, non-weight-based dose in patients with a variety of solid tumors. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2014;74:819–829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rosario M, Dirks NL, Gastonguay MR, et al. Population pharmacokinetics-pharmacodynamics of vedolizumab in patients with ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;42:188–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang F, Paccaly AJ, Rippley RK, Davis JD, DiCioccio AT. Population pharmacokinetic characteristics of cemiplimab in patients with advanced malignancies. J Pharmacokinet Pharmacodyn. 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wilkins JJ, Brockhaus B, Dai H, et al. Time-Varying Clearance and Impact of Disease State on the Pharmacokinetics of Avelumab in Merkel Cell Carcinoma and Urothelial Carcinoma. CPT Pharmacometrics Syst Pharmacol. 2019;8:415–427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li HS, Sun YN, Yu JY, Liu C, Liu J, Wang YN. Semimechanistically Based Modeling of Pembrolizumab Time-Varying Clearance Using 4 Longitudinal Covariates in Patients With Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. J Pharm Sci-Us. 2019;108:692–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sanghavi K, Zhang JS, Zhao XC, et al. Population Pharmacokinetics of Ipilimumab in Combination With Nivolumab in Patients With Advanced Solid Tumors. Cpt-Pharmacomet Syst. 2020;9:29–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang JS, Sanghavi K, Shen J, et al. Population Pharmacokinetics of Nivolumab in Combination With Ipilimumab in Patients With Advanced Malignancies. Cpt-Pharmacomet Syst. 2019;8:962–970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baverel PG, Dubois VFS, Jin CY, et al. Population Pharmacokinetics of Durvalumab in Cancer Patients and Association With Longitudinal Biomarkers of Disease Status. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2018;103:631–642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Toh WH, Louber J, Mahmoud IS, et al. FcRn mediates fast recycling of endocytosed albumin and IgG from early macropinosomes in primary macrophages. J Cell Sci. 2020;133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bajaj G, Suryawanshi S, Roy A, Gupta M. Evaluation of covariate effects on pharmacokinetics of monoclonal antibodies in oncology. British journal of clinical pharmacology. 2019;85:2045–2058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Baracos VE, Martin L, Korc M, Guttridge DC, Fearon KCH. Cancer-associated cachexia. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018;4:17105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fearon K, Strasser F, Anker SD, et al. Definition and classification of cancer cachexia: an international consensus. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:489–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ni J, Zhang L. Cancer Cachexia: Definition, Staging, and Emerging Treatments. Cancer Manag Res. 2020;12:5597–5605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Turner DC, Kondic AG, Anderson KM, et al. Pembrolizumab Exposure-Response Assessments Challenged by Association of Cancer Cachexia and Catabolic Clearance. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24:5841–5849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Castillo AMM, Vu TT, Liva SG, Chen M, Xie Z, Thomas J, Remaily B, Guo Y, Subrayan UL, Costa T, Helms TH, Irby DJ, Kim K, Owen DH, Kulp SK, Mace TA, Phelps MA, and Coss CC Murine cancer cachexia models replicate elevated catabolic pembrolizumab clearance in humans. JCSM Rapid Communications. 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Oken MM, Creech RH, Tormey DC, et al. Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Am J Clin Oncol. 1982;5:649–655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)-A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Capone M, Giannarelli D, Mallardo D, et al. Baseline neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) and derived NLR could predict overall survival in patients with advanced melanoma treated with nivolumab. J Immunother Cancer. 2018;6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Diem S, Schmid S, Krapf M, et al. Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte ratio (NLR) and Platelet-to-Lymphocyte ratio (PLR) as prognostic markers in patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) treated with nivolumab. Lung Cancer. 2017;111:176–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Matsubara T, Takamori S, Haratake N, et al. The impact of immune-inflammation-nutritional parameters on the prognosis of non-small cell lung cancer patients treated with atezolizumab. J Thorac Dis. 2020;12:1520–1528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mezquita L, Auclin E, Ferrara R, et al. Association of the Lung Immune Prognostic Index With Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Outcomes in Patients With Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Jama Oncol. 2018;4:351–357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sen S, Hess K, Hong DS, et al. Development of a prognostic scoring system for patients with advanced cancer enrolled in immune checkpoint inhibitor phase 1 clinical trials. Br J Cancer. 2018;118:763–769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pathak R, Lopes GD, Yu H, et al. Comparative efficacy of chemoimmunotherapy versus immunotherapy for advanced non-small cell lung cancer: A network meta-analysis of randomized trials. Cancer-Am Cancer Soc. 2021;127:709–719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jiang Y, Tu X, Zhang X, et al. Nutrition and metabolism status alteration in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma patients treated with anti-PD-1 immunotherapy. Supportive care in cancer : official journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer. 2020;28:5569–5579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Roch B, Coffy A, Jean-Baptiste S, et al. Cachexia - sarcopenia as a determinant of disease control rate and survival in non-small lung cancer patients receiving immune-checkpoint inhibitors. Lung Cancer. 2020;143:19–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Turcott JG, Martinez-Samano JE, Cardona AF, et al. The Role of a Cachexia Grading System in Patients with Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Treated with Immunotherapy: Implications for Survival. Nutr Cancer. 2021;73:794–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chu MP, Lieffers J, Ghosh S, et al. Skeletal muscle density is an independent predictor of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma outcomes treated with rituximab-based chemoimmunotherapy. J Cachexia Sarcopeni. 2017;8:298–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kurk S, Peeters P, Stellato R, et al. Skeletal muscle mass loss and dose-limiting toxicities in metastatic colorectal cancer patients. J Cachexia Sarcopeni. 2019;10:803–813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.da Rocha IMG, Marcadenti A, de Medeiros GOC, et al. Is cachexia associated with chemotherapy toxicities in gastrointestinal cancer patients? A prospective study. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2019;10:445–454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.FDA approves nivolumab plus ipilimumab for first-line mNSCLC (PD-L1 tumor expression ≥1%). https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-approvals-and-databases/fda-approves-nivolumab-plus-ipilimumab-first-line-mnsclc-pd-l1-tumor-expression-1. Accessed February 27, 2021.

- 60.Morimoto K, Uchino J, Yokoi T, et al. Impact of cancer cachexia on the therapeutic outcome of combined chemoimmunotherapy in patients with non-small cell lung cancer: a retrospective study. Oncoimmunology. 2021;10(1):1950411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.