Abstract

Lorcaserin is a modestly selective agonist for 2C serotonin receptors (5-HT2CR). Despite early promising data, it recently failed to facilitate cocaine abstinence in patients, and has been compared to dopamine antagonist medications (antipsychotics). Here, we review the effects of both classes on drug reinforcement. In addition to not being effective treatments for cocaine use disorder, both dopamine antagonists and lorcaserin can have biphasic effects on dopamine and reward behavior. Lower doses can cause enhanced drug taking with higher doses causing reductions. This biphasic pattern is shared with certain stimulants, opioids, and sedative-hypnotics; as well as compounds without abuse potential which include agonists for muscarinic and melatonin receptors. Additional factors associated with decreased drug taking include intermittent dosing for dopamine antagonists and use of progressive-ratio schedules for lorcaserin. Clinically relevant doses of lorcaserin were much lower than those that inhibited cocaine-reinforced behavior, and can also augment this same behavior in different species. Diminished drug-reinforced behavior only occurred in animals after higher doses which are not suitable for use in patients. In conclusion, drugs of abuse and related compounds often act as biphasic modifiers of reward behavior, especially when evaluated over a broad range of doses. This property may reflect the underlying physiology of the reward system, allowing homeostatic influences on behavior.

Keywords: Cocaine-Related Disorders, Dose-Response Relationship, Drugs of Abuse, Homeostasis, Self-Administration, Serotonin Receptor Agonists

Introduction

The current epidemic of drug abuse is causing a rising incidence of morbidity and mortality associated with overdose (Mattson et al., 2021) and a substantial economic burden (Bounthavong et al., 2021). Different illicit substances are often adulterated with undisclosed synthetic opioids, increasing the risk of life-threatening overdose (Althoff et al., 2020). For abuse of cocaine and methamphetamine, no approved treatments are currently available (Castells et al., 2016). Based on these trends, new and innovative treatments for substance abuse disorders are urgently needed (Pardo et al., 2021).

The ideal treatment for substance abuse disorders is often considered a biologically-based agent that monophasically decreases drug taking without disrupting alternative behaviors. Early reports portrayed lorcaserin along these lines. It acts as a modestly selective agonist for type 2C serotonin receptors (5-HT2CR), but was recently withdrawn from the market because of its cancer potential (Sharretts et al., 2020). Afterwards, the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) posted preliminary negative data for their trial of lorcaserin in preventing relapse for cocaine use disorder (National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2020). By inference, other agents from this class may not be useful treatments for cocaine use disorder, regardless of their safety and tolerability.

In reviewing NIDA’s trial in treatment-seeking patients, Negus and Banks (2020) describe lorcaserin as an ‘antagonist’ medication that attenuates cocaine-induced increases in dopamine in the nucleus accumbens. This paper will review the role of the serotonin type 2C receptor subtype for influencing drug-motivated behaviors, making comparisons with dopamine antagonists.

The Serotonin System

Serotonin (5-HT or 5-hydroxytryptamine) is one of three monoamine neurotransmitters that play important roles in affect and goal-directed behaviors (Nestler et al., 2020). Serotonergic neurons are located in brain-stem raphe nuclei, and make ascending projections to the basal ganglia, frontal cortex, hypothalamus, and other limbic structures (Steinbusch et al., 2021). Activity of serotoninergic neurons is modulated by 15 or more receptor subtypes (Filip et al., 2009). In addition to the 5-HT2CR, the subfamily of type 2 serotonergic G protein-coupled receptors includes 5-HT2AR and 5-HT2BR (Roth et al., 1998). These three subtypes exhibit significant sequence homology, especially within their transmembrane portions.

5-HT exerts complex actions on limbic neurons, playing a role in both food- and drug- reinforced behaviors. For example, repeated injections of cocaine over five days attenuates serotonin-induced enhancement of excitatory glutamatergic input to prefrontal cortex (Huang et al., 2009). In general, medications that augment serotonergic tone, such as fluoxetine or the 5-HT precursor L-tryptophan, decrease self-administration of cocaine or other stimulants, reviewed by Higgins and Fletcher (2003). Conversely, pretreatment with agents that deplete brain 5-HT levels enhances responding for cocaine (Roberts et al., 1994) or amphetamine (Leccese et al., 1984).

Activation of type 2C serotonin receptors after food intake depolarizes proopiomelanocortin (POMC) neurons in the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus, leading to release of α-melanocyte-stimulating hormone (Mercer et al., 2013). This compound then transmits an anorectic signal to the paraventricular hypothalamus. With exposure to a high fat diet, mutant mice without the 5-HT2CR develop obesity, elevated insulin levels, and spontaneous seizures (Tecott et al., 1995). Conversely, 5-HT2C activation by acute or chronic lorcaserin decreases food intake in rats, through a receptor-mediated and reversible mechanism (Thomsen et al., 2008).

Dopamine Interactions

Dopamine Antagonists

Most medications used to treat psychosis caused by schizophrenia and related disorders, often referred to as antipsychotics, function by blocking activation of dopamine receptors. First generation (typical) antipsychotics act primarily at the dopamine D2 receptor (Seeman, 2013). Newer, second and third generation atypical antipsychotics have lower affinity for the D2 receptor and have complementary mechanisms of action. Given the central role of dopamine in underlying drug-motivated behavior (Di Chiara, 1995), various studies have evaluated dopamine antagonists for potential anti-addictive effects. For the purpose of this review, we will refer to either type of antipsychotic as dopamine antagonists, emphasizing their dopamine blocking properties.

First generation dopamine antagonists include chlorpromazine, flupenthixol, haloperidol, and others. Chlorpromazine was the first marketed medication in this class, which led to a fundamental change in the treatment of psychosis (Ban, 2007). It acts as a nonselective dopamine antagonist, and also has serotonergic, adrenergic, and histamine blocking properties (Boyd-Kimball et al., 2019). Flupenthixol has a similar pattern of affinities for the same receptors, but greater potency (Peroutka et al., 1980). Pimozide and haloperidol are relatively selective for blocking the D2 receptor but having lower affinity for the histamine receptor (Richelson, 1988, Snyder, 1996).

Atypical dopamine antagonists are a heterogeneous class (Meyer, 2018). In addition to low-affinity blockade of the D2 receptor, they are often inverse agonists at 5-HT2A and 5-HT2C receptors (Sullivan et al., 2015). Atypical agents may be better tolerated than typical antipsychotics. Although the atypical antipsychotic clozapine can cause infrequent but life threatening reductions in circulating white blood cells, it is associated with improved overall survival in patients with schizophrenia (Vermeulen et al., 2019).

When infused to the striatum by microdialysis probe, an early study (Westerink et al., 1989) noted that 10 nM or greater concentrations of a dopamine antagonist produced linear increases in dopamine release. This property was attributed to blockade of presynaptic D2-like autoreceptors, causing loss of feedback influences on neurotransmitter synthesis and degradation. In freely moving, awake rats, systemic treatment with various typical or atypical dopamine antagonists caused linear increases in extracellular dopamine in the nucleus accumbens and prefrontal cortex (Kuroki et al., 1999). Using anesthetized rats, linear increases in nucleus accumbal dopamine occurred after treatment with systemic doses of 0.1 mg/kg of different typical dopamine antagonists (Moghaddam et al., 1990).

A recent study using both microdialysis and single-photon emission computerized tomography (SPECT) evaluated two doses of both the typical dopamine antagonist haloperidol and the atypical agent clozapine. Microdialysis demonstrated better temporal resolution, showing that systemic haloperidol produced initial dose-related increases in striatal extracellular dopamine also reflected by reduced SPECT ligand binding (Park et al., 2019). Afterwards, dopamine concentration declined below its initial baseline for high- but not low- dose haloperidol. Either dose of clozapine increased in striatal dopamine.

Lorcaserin

Serotonin neurons synapse directly on several dopaminergic structures that are important for drug reward; including the ventral tegmental area (VTA), nucleus accumbens, and prefrontal cortex (Howell et al., 2015). The 5-HT2CR is expressed by neurons in the same brain regions (Pompeiano et al., 1994, Valencia-Torres et al., 2017). Therefore, both the serotonin system and the 5-HT2CR are well-positioned to influence reward behaviors. Preclinical studies have shown that systemic administration of selective 5-HT2CR agonists decreases both the firing rate of VTA dopaminergic neurons and dopamine release by terminal projections to the nucleus accumbens; with an opposite effect of antagonists (Bubar et al., 2008). Systemic lorcaserin also inhibited the activity of a subpopulation of VTA dopamine neurons in rats, without affecting the activity in substantia nigra or extracellular dopamine in the nucleus accumbens or striatum (De Deurwaerdère et al., 2020). 5-HT2CR knock-out animals exhibit greater cocaine-induced elevations of dopamine levels in the nucleus accumbens, and increased novelty- and cocaine- induced locomotor activity (Rocha et al., 2002). Based on these findings, 5-HT2CR agonists were hypothesized to function as dopamine antagonists, perhaps effective for reducing craving and enhancing abstinence in treatment-seeking patients.

Not all findings have supported the role of 5-HT2CR activation as only opposing dopaminergic function. Firstly, dopamine release in nucleus accumbens stimulated by cocaine is increased by infusion of a 5-HT2CR agonist directly to this brain region at a low concentration, and decreased following infusion at a greater concentration (Navailles et al., 2008). Secondly, increases in accumbal dopamine after cocaine were potentiated by delivery of a 5-HT2CR agonist to the prefrontal cortex (Leggio et al., 2009).

Rather than functioning as agents that only oppose actions of the dopaminergic system, lorcaserin and other 5-HT2CR agonists appear to have the potential to modulate dopamine output in a biphasic manner at reward regions. Potentiation of dopamine release appears to be favored when administered at relatively low concentrations or in combination with cocaine.

Drug-Reinforced Behavior

Dopamine Antagonists

Preclinical

Pretreatment with single doses of typical (first generation) dopamine antagonists have variable effects on cocaine-reinforced behavior. See reviews by Mello and Negus (1996) and Platt et al. (2002). Characteristic effects include:

-

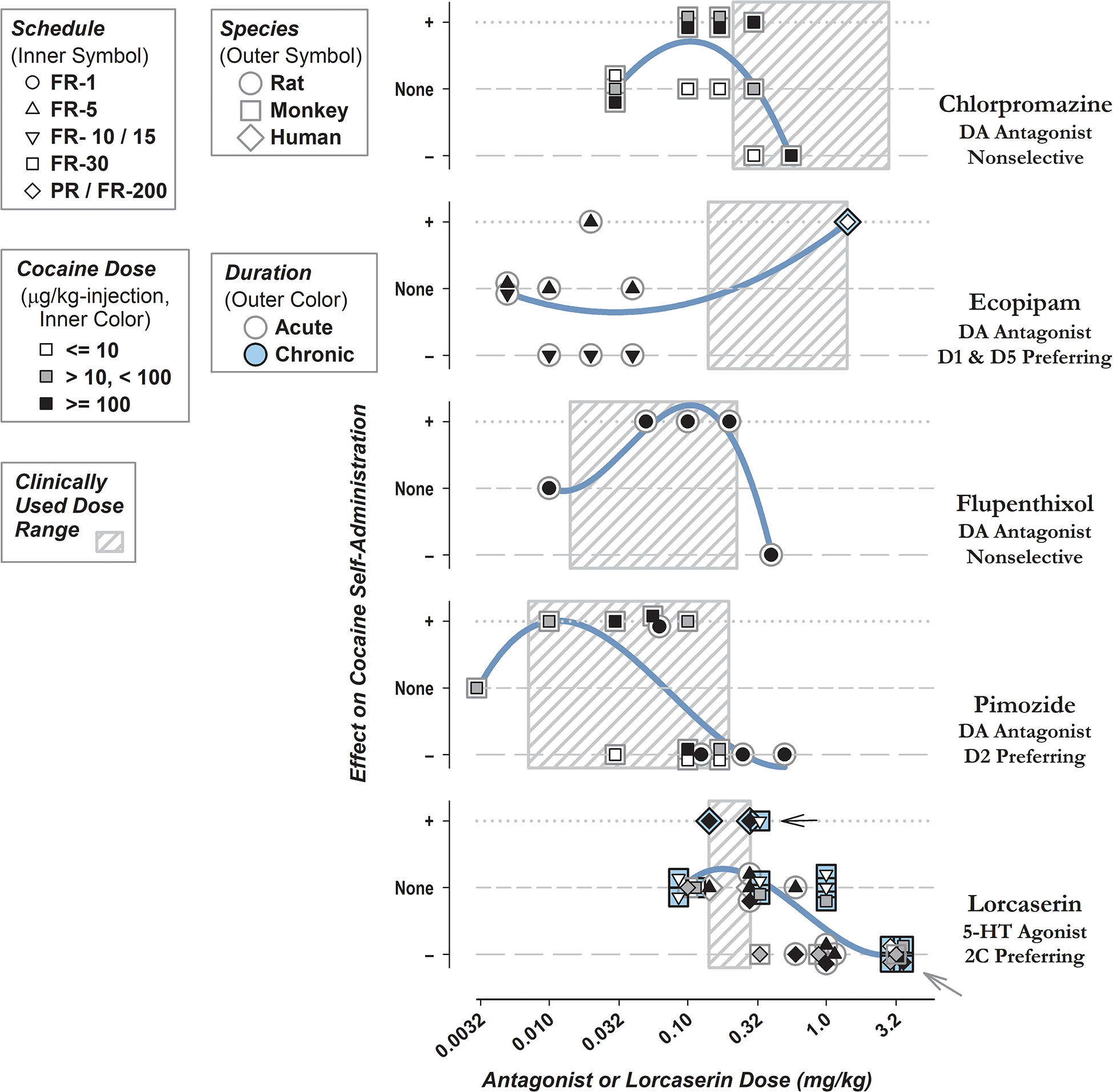

Cocaine-Reinforced Responding is Increased by Acute, Low-Dose Dopamine Antagonists; but Decreased after Higher Doses. Figure 1 shows representative examples for nonselective agents chlorpromazine (Glowa et al., 1996) or flupenthixol (Ettenberg et al., 1982), and pimozide which exhibits selectivity for the dopamine D2 receptor (De Wit et al., 1977). Comparable effects were observed for both rats and rhesus monkeys. Pimozide caused a similar biphasic influences on amphetamine- reinforced responding in rats (Yokel et al., 1975). Higher doses of chlorpromazine did not attenuate response rate during food-reinforced responding, while response rate was decreased by high-dose pimozide for both drug- and food- reinforced behavior (Glowa et al., 1996).

Importantly, reductions in cocaine self-administration become inconsistent after repeated dosing. Acute pretreatment with flupenthixol diminished the reinforcing effects of low doses of intravenous cocaine in rhesus monkeys, but the effect became inconsistent when repeated over 3 to 5 days (Negus et al., 1996). Increases in cocaine-reinforced responding were not observed in this study, likely because a second-order schedule with variable- and fixed- ratio components was employed. Blockade of the discriminative stimulus effects of cocaine by flupenthixol was also transient over days. Rate-decreasing effects of the D1 selective antagonist SCH-23390 during cocaine self-administration also faded within several days of being initiated (Kleven et al., 1990). These results appear to have had important implications for patient-based studies in which chronically administered typical dopamine antagonists have had disappointing results in preventing relapse of stimulant-reinforced behavior (see below).

For a Given Antagonist Dose, Enhancement or Suppression of Drug Taking is More Likely after Lesser- or Greater- Schedule Requirements, Respectively. Biphasic effects of dopamine antagonists can also be shown by varying reinforcement schedule in rats. For example, single doses of ecopipam, an antagonist for type D1 and D5 dopamine receptors, augmented responding under fixed-ratio-5 with a 20-second time out, but attenuated responding under fixed-ratio-15 with a 2-minute time out (Caine et al., 1994). See Figure 1, second panel down from top. An additional study in rats found that single injections of the long-acting decanoate forms of the typical dopamine antagonists flupenthixol or haloperidol caused long-lasting increases in self-administration under FR-1, but decreases in the number of cocaine injections self-administered under a progressive-ratio schedule that persisted for four days or longer (Richardson et al., 1994).

Figure 1.

Changes in Cocaine Self-Administration following Pretreatment with Dopamine Antagonists or Lorcaserin in Laboratory Studies. Total daily doses of dopamine antagonist or lorcaserin pretreatment are shown on horizontal axes. Effects of either class are divided into different categories according to those reporting increases in drug taking or response rate represented as a positive or ‘+’ effect (dotted lines), decreases illustrated by a negative or ‘−’ (long-dash lines), or no effect (short-dashed lines). Criteria of 25% above or below baseline were used to identify increases or decreases respectively from selected studies, all of which are cited above. Some data points are shifted laterally or vertically to accommodate overlap. Because Glowa et al. (1996) reported only response rate and not the number of self-administered cocaine injections, categories for this study are assigned based on changes in response rate. Otherwise, assignments are according to change in the number of self-administered cocaine injections. Legends show schedule (inner symbol), species (outer symbol), unit dose of cocaine (inner color), and duration of pretreatment (outer color). For example, the gray arrow on the lower right-hand side shows results from five evaluations of lorcaserin administered at 3.2 mg/kg, all conducted using rhesus monkeys, with one using a cocaine unit dose of 10 μg/kg, another testing 100 μg/kg, and the others using intermediate doses of cocaine. The black arrow points to results in which lorcaserin increased cocaine-reinforced behavior after chronic treatment, obtained in humans and rhesus monkeys. Gray boxes indicate the clinically used range of doses for either class with lowest single doses shown by left-hand borders and the maximum daily doses by right-hand borders. Curves show results of third-order linear regression, for effect on cocaine self-administration against dose of antagonist or lorcaserin.

Some studies have shown that pretreatment with dopamine antagonists can reliably attenuate conditioned place preference induced by opioids, with no obvious enhancement of preference. For example, acute treatment with 0.5 mg/kg of pimozide decreased place preference conditioned by 0.5 mg/kg of heroin (Bozarth et al., 1981). The pimozide dose employed was five-fold higher than the maximum dose used to show enhancement of cocaine self-administration in Figure 1. This raises doubt as to whether the effects of lower dopamine antagonist doses have been adequately evaluated, which may have caused increases in place preference. Expression of conditioned-place preference induced by 2.0 mg/kg of heroin was attenuated by 0.2 mg/kg of haloperidol (Spyraki et al., 1983). Nonetheless, mice withdrawn after repeated treatment with 1.0 mg/kg of haloperidol exhibit a two-fold increase in place preference conditioned by 5.0 mg/kg of cocaine (Fukushiro et al., 2007). Although not motivated by a drug of abuse, low-dose dopamine antagonists can potentiate food-induced conditioned place preference in rats (Guyon et al., 1993).

Again considering opioids, acute treatment with low- or high- dose haloperidol increased or decreased morphine self-administration during reacquisition of extinguished responding (Smith et al., 1973). Self-administration of 60 μg/kg-injection heroin was modestly decreased by pretreatment with 0.4 mg/kg of flupenthixol but was unaffected by doses of 0.1 and 0.2 (Ettenberg et al., 1982). The absence of low-dose enhancement may be because of the relatively high dose of heroin used; heroin doses of 1.0 or 3.2 μg/kg-injection were used to show lorcaserin-induced increases in drug taking (see below), but increases were not observed after self-administration of 10 or 32 μg/kg-injection in this study (Townsend et al., 2020). Acquisition of intravenous self-administration or conditioned-place preference using low-dose heroin was enhanced after chronic treatment with the decanoate form of flupenthixol (Stinus et al., 1989).

Clinical

In a human laboratory study, pretreatment with single doses of haloperidol partially attenuated the subjective effects of intravenous cocaine and also decreased drug-induced increases in blood pressure (Sherer et al., 1989). Chronic treatment with the decanoate form of flupenthixol did not attenuate the reinforcing or positive subjective effects of cocaine, but appeared to cause modest increases in craving and ratings of drug value (Evans et al., 2001). But, the protocol used was not designed to detect increases in drug-reinforced responding, as participants self-administered near the limit of maximal available cocaine injections. Because it would not have detected an increase in cocaine-reinforced behavior, it is not included in Figure 1. Dystonic motor reactions occurred in two of five participants who received high-dose flupenthixol prior to exposure to cocaine, causing further evaluation of this dose level to be discontinued.

Acute pretreatment with single doses of ecopipam, attenuated cocaine-induced ‘high’, stimulated, and ‘good’ drug effects by more than one-half (Romach et al., 1999). Nonetheless, chronic daily treatment with ecopipam over one week failed to modify the positive subjective effects of cocaine (Nann-Vernotica et al., 2001). Eight days of daily pretreatment with ecopipam increased self-administration of smoked cocaine and caused small increases in its positive subjective effects (Haney et al., 2001). There is no data on the effects of higher doses of ecopipam.

The atypical dopamine antagonist aripiprazole acts as a partial agonist at the dopamine D2 receptor (Wood et al., 2007). Although aripiprazole maintenance produced minimal effects on the subjective effects of intranasal cocaine; it caused biphasic changes in willingness to take drug again, which were diminished for low-dose but increased for high-dose cocaine (Stoops et al., 2007). Chronic aripiprazole treatment decreased ratings of ‘good’ drug, cocaine quality, and drug craving; while enhancing self-administration of low-dose cocaine (Haney et al., 2011). Another study showed increases in euphoria and stimulant effects in patients receiving methamphetamine after chronic aripiprazole treatment (Newton et al., 2008).

As a class, dopamine antagonists may improve retention when used in treatment-seeking patients with cocaine use disorder; but have not convincingly improved more accepted measures of abstinence, drug use, or relapse (Indave et al., 2016, Chan et al., 2019). Small sample sizes, incomplete reporting, and high participant attrition limit the quality of this evidence.

Lorcaserin

Preclinical

Effects of lorcaserin pretreatment on cocaine-reinforced behavior were reported by two studies in rats (Harvey-Lewis et al., 2016, Anastasio et al., 2020) and four in rhesus monkeys (Collins et al., 2015, Gerak et al., 2016, Banks et al., 2017, Collins et al., 2018). When administered under different conditions, lorcaserin caused variable effects on cocaine self-administration (increases, no change, or decreases); with decreases in drug taking uniformly reported after pretreatment with 3.2 mg/kg of lorcaserin. Attenuation of drug taking was more likely for responding under a progressive-ratio rather that fixed-ratio schedules, in rats pretreated with 0.6 mg/kg of lorcaserin (Harvey-Lewis et al., 2016) or rhesus monkeys receiving 0.1 or 0.32 of lorcaserin (Collins et al., 2015, Collins et al., 2018).

Considering opioid-reinforced responding, chronic pretreatment with doses of lorcaserin exceeding those approved for clinical use augmented opioid-reinforced behavior (Townsend et al., 2020), with acute pretreatment decreasing drug taking (Neelakantan et al., 2017, Kohut et al., 2018). In one study, the dose of acute lorcaserin required to attenuate opioid self-administration also attenuated food-reinforced responding (Panlilio et al., 2017), consistent with a nonselective effect on behavior rewarded by drug or food.

Either single or multiple doses of lorcaserin can attenuate behavior reinforced by intravenous nicotine in rats (Levin et al., 2011, Higgins et al., 2012). Although the degree of attenuation increased linearly with greater lorcaserin dose, effective doses also decreased food-reinforced responding (Higgins et al., 2012) and locomotor activity (Levin et al., 2011). However, chronic treatment with an intermediate dose of lorcaserin that did not modify locomotor activity decreased nicotine self-administration by greater than one-half, without modifying food-reinforced responding. Nonetheless, responding for intravenous nicotine was more than three-fold lower than responding for food pellets in both of these studies (Levin et al., 2011, Higgins et al., 2012), which may have biased results towards a greater effect on drug-reinforced behavior. Two additional studies showed that pretreatment with 0.6 mg/kg of lorcaserin can attenuate nicotine self-administration in rats, but did not evaluate control non-drug reinforced behavior (DiPalma et al., 2019, Willette et al., 2019).

Ketanserin is a nonselective antagonist, with activity at both the 5-HT2AR and the 5-HT2CR. When squirrel monkeys lever-pressed to obtain cocaine under a second-order schedule, treatment with ketanserin enhanced responding for low- or intermediate- doses of cocaine (Howell et al., 1995). However, ketanserin decreased nicotine self-administration in rats (Levin et al., 2008). Combined with studies of lorcaserin, these findings support the role of type 2 serotonergic receptors in modulating psychostimulant reward.

Clinical

As shown by the widths of hatched boxes in Figure 1, compared to dopamine antagonists, lorcaserin was used in humans over a relatively narrow dose range. Acute pretreatment with a single 10 or 20 mg doses of lorcaserin did not modify cocaine self-administration (Pirtle et al., 2019). In that study, the lower 10 mg dose increased ratings of ‘high’ and ‘stimulated’ after low-dose cocaine or vehicle, decreased drug craving after intravenous vehicle, and prolonged the time over which participants made intravenous choices. A second human study observed increased self-administration of cocaine under a progressive-ratio schedule after 10 mg of lorcaserin was administered once or twice daily (Johns et al., 2021).

When administered to humans at 10 mg twice-daily, lorcaserin failed to modify oxycodone self-administration (Brandt et al., 2020). However, the study identified a trend for lorcaserin to increase opioid craving (“wanting heroin”) when oxycodone was available.

Euphoria was reported in patients receiving lorcaserin for weight loss (Food and Drug Administration Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, 2011) or abuse liability testing (Shram et al., 2011). Prior to scheduling by the United States Drug Enforcement Administration, lorcaserin was actively marketed by “no prescription” online vendors in violation of prescription requirements (Liang et al., 2013). Because of concern over its potential for abuse, lorcaserin would eventually be marketed in the United States as a controlled substance. Positive subjective effects of lorcaserin may have contributed to increased cocaine self-administration.

Overall Effects on Cocaine Self-Administration

Our major conclusions for effects of lorcaserin and dopamine antagonists on cocaine-reinforced behavior are shown graphically in Figure 1:

Both classes most often produce biphasic effects on drug-reinforced behavior. The one exception is ecopipam, discussed below.

- For lorcaserin

- Clinically relevant doses are associated with either no effect or increases in drug taking in a laboratory setting. This is the best explanation for its failure to facilitate abstinence in treatment-seeking patients.

- Reductions in drug taking have only been seen in non-humans after doses that exceed those used clinically. These are observed in rats or monkeys, under different schedules, for self-administration of low, intermediate, or high doses of cocaine.

Consistent with our first conclusion, analysis by third-order regression produced concave-down curves for lorcaserin and most dopamine antagonists (Figure 1). Although ecopipam did not follow this pattern, this may reflect an absence of studies evaluating relatively high doses of this compound. In addition, modest single doses administered subcutaneously in animals (Caine et al., 1994) are likely not comparable to the higher human doses of ecopipam administered over 5 days which caused increases in cocaine self-administration (Haney et al., 2001). In the current scientific climate, reductions in drug taking are often assessed as more valuable by journals and funding agencies. If so, increases in self-administration may be less likely to be reported, possibly dampening the concave-down shape of the lorcaserin dose-effect curve.

Ignoring ecopipam and methodologic differences between the two classes, the magnitude of concave-down regression curves appears greater for dopamine antagonists. Overall, pretreatment with dopamine antagonists were more likely to either increase or decrease cocaine-reinforced behavior, and less likely to have no effect. Relative to evaluations of dopamine antagonists, more recent studies testing lorcaserin were more likely to utilize chronic pretreatment and progressive-ratio schedules. These differences limit the strength of comparisons between the two classes.

Dependence on cocaine and other classes of abused substances can diminish dopamine neurotransmission in the ventral striatum of animals (Gerrits et al., 2002) and humans (Volkow et al., 1997, Martinez et al., 2007). Increased dopamine in the nucleus accumbens following low-dose dopamine antagonist (Kuroki et al., 1999) or cocaine combined with low-level 5-HT2CR activation (Navailles et al., 2008) may underlie greater drug taking for either class. When administered at higher doses, both dopamine antagonists (Ramaekers et al., 1999, Thompson et al., 2020) and lorcaserin (Shram et al., 2011) can cause significant adverse effects, which could disrupt drug taking. Decreases in dopamine following high-dose dopamine antagonists (Park et al., 2019) or lorcaserin (Navailles et al., 2008) may also contribute to reductions in drug taking. Our hypothesis is that changes in dopamine transmission contribute to effects of lorcaserin and dopamine antagonists on mood and drug taking.

Other Classes causing Biphasic Reward Effects

Table 1 summarizes classes of medication that biphasically modify food or drug reward. Each exhibits enhancement and inhibition following low- and high- doses, respectively.

Table 1. Biphasic Reward Effects by Class.

Different types of medication are listed in alphabetical order which can produce both increases (⇑) or decreases (⇓) in self-administration, food-reinforced responding, or conditioned-place preference. Changes indicate either statistically significant effects at p < 0.05 or differences from baseline of 25% or more.

| Class | Example | Reward | Reference(s) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enhancement (mg/kg)† | Inhibition (mg/kg)† | |||

| Dopamine Antagonist (Anti-psychotic) | Pimozide | 0.01 to 0.056: ⇑ Cocaine SFA, FR-5 & FR-30 |

0.125 to 0.170: ⇓ Cocaine SFA, FR-5 & FR-30 |

Glowa and Wojnicki [24],De Wit and Wise [26]. Additional examples in Figure 1. |

| 0.03 & 0.06: ⇑ Food CPP, Acquisition |

0.5: ⇓ Heroin CPP, Acquisition |

Bozarth and Wise [34],Guyon, Assouly-Besse [36]. | ||

| Melatonin Agonist | Melatonin | 5, 10, & 20: ⇑ Morphine CPP, Acquisition |

25 & 50: ⇓ Morphine CPP, Expression |

Yahyavi-Firouz-Abadi, Tahsili-Fahadan [82],Han, Xu [83]. |

| 25 & 50: ⇓ Cocaine SFA, PR |

Takahashi, Vengeliene [86]. | |||

| Muscarinic Agonist | Pilocarpine | 1.0: ⇑ Cocaine SFA, FR-5‡ |

3.2 & 10: ⇓ Cocaine SFA, FR-5 |

Grasing, Xu [81]. |

| Nicotinic Agonist | Nicotine | 0.3: ⇑ Cocaine SFA, PR |

0.6: ⇓ Cocaine SFA, PR |

Bechtholt and Mark [76]. |

| Opioid Agonist | Heroin^ | 0.001: ⇑ Cocaine SFA, 2nd Order, FR-4 |

0.01: ⇓ Cocaine SFA, 2nd Order, FR-4 |

Mello, Negus [79]. |

| Sedative-Hypnotic | Diazepam | 0.25: ⇑ Cocaine SFA, FR-1 |

8 & 16: ⇓ Cocaine SFA, Fixed-Interval, FR-2 |

Augier, Vouillac [78]; Maier, Ledesma [77]. |

| Serotonin 2C Agonist | Lorcaserin | 0.32 & 1.0: ⇑ Cocaine SFA, FR-10 |

1.0 & 3.2: ⇓ Cocaine SFA, PR |

Banks and Negus [58],Collins and France [59]. Additional examples in Figure 1. |

| 0.20 & 0.64:§ ⇑ Heroin SFA, FR-10 |

1.0: ⇓ Heroin SFA, PR |

Townsend, Negus [38],Kohut and Bergman [61]. | ||

| Stimulants | Amphetamine | 0.064, 0.200: ⇓ Cocaine SFA, PR |

Negus and Mello [80]. | |

| Cocaine | 0.001 to 0.1: ⇑ Heroin SFA, 2nd Order, FR-4 |

0.001 to 0.1: NE Heroin SFA, 2nd Order, FR-4 |

Mello, Negus [79]. | |

Dose of example compound causing effects.

Reported as a trend effect at p < 0.05.

Self-administered dose of heroin. Example compounds otherwise given as single-dose pretreatments.

Administered as a continuous infusion, with the total dose given during the behavioral session listed.

Abbreviations: CPP = Conditioned Place Preference, FR = Fixed-Ratio schedule, PR = Progressive-Ratio schedule, and SFA = Self-Administration.

For rats responding under a progressive-ratio schedule, the number of self-administered injections of cocaine is increased after pretreatment with low-dose nicotine, but decreased after pretreatment with a higher nicotine dose (Bechtholt et al., 2002). Pretreatment with low-dose diazepam increased self-administration of cocaine under a simple fixed-ratio schedule (Maier et al., 2008), but increasing the pretreatment dose by 32-fold decreased self-administration of cocaine without affecting responding for saccharin (Augier et al., 2012).

Rhesus monkeys responding under a second-order schedule for stimulant-opioid (‘speedball’) combinations self-administer a low-dose of cocaine alone at modest levels, which can be augmented by combining it with low-dose heroin (Mello et al., 1995). However, self-administration is diminished when greater doses of cocaine and heroin are combined. For the opposite situation, self-administration of low-dose heroin can be increased when combined with different doses of cocaine. Drug taking was non-significantly decreased when high-dose heroin and cocaine were combined (approximately 20%). This effect may become significant after further increases in cocaine dose. Chronic amphetamine pretreatment decreased cocaine self-administration by rhesus monkeys, with less pronounced effects on food-reinforced responding (Negus et al., 2003).

Opioids, psychostimulants, and sedative-hypnotics are among the drug classes listed in Table 1. Low- and high- dose enhancement and suppression or reward may be a general property of abused substances. Even so, several of the classes listed in Table 1 have no abuse potential. For example, pretreatment with low-doses of the nonselective muscarinic agonist pilocarpine produced a trend for increased cocaine self-administration (exceeding baseline by 11%, p = 0.033), without affecting food-reinforced responding (Grasing et al., 2019). Higher doses of pilocarpine decreased cocaine self-administration, again without modifying food-reinforced responding.

Melatonin functions as an endogenous neurohormone and neurotransmitter that plays a role in daily and seasonal rhythms, but is not known for its abuse potential. When administered at 5 to 20 mg/kg in mice, melatonin increases the place preference conditioned by low-dose morphine by more than 2-fold (Yahyavi-Firouz-Abadi et al., 2007). In other experiments, 25 or 50 mg/kg strongly attenuated the expression of place preferences conditioned by morphine in mice (Han et al., 2008). Overall, biphasic effects on reward are shared by compounds with and without significant abuse potential.

Mechanisms underlying Biphasic Effects on Reward

Loss of Receptor Selectivity

Using in vitro methods, the functional selectivity of lorcaserin for activating 5-HT2C over 5-HT2A and 5-HT2B receptor subtypes has been estimated at 18- and 104- fold, respectively (Thomsen et al., 2008). Off-target activation of the 5-HT2A or 5-HT2B receptors was felt to be unlikely at the previously approved clinical dose of lorcaserin (Food and Drug Administration Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, 2011). This interpretation is based on the lack of obvious signs of 5-HT2A or 5-HT2B receptor activation by lorcaserin in animals receiving clinically-relevant doses of lorcaserin. Reliable reductions in drug taking were only seen at significantly higher lorcaserin doses used in animals (Figure 1), possibly due to off-target or nonselective effects in these experiments.

For dopamine antagonists, off-target activation of a variety of receptors other than the dopamine D2 and 5-HT2A increases with greater drug concentrations (Meyer, 2018). Therefore, reductions in drug taking may also be caused by these nonselective effects which disrupt behavior. Compared to lorcaserin, dopamine antagonists are typically tolerated and prescribed over a much broader range of doses (Figure 1). Even so, significant dose-limiting sedation and motor dysfunction can occur in healthy (Veselinović et al., 2011) or cocaine-abusing individuals receiving dopamine antagonists (Evans et al., 2001). These side effects are most likely secondary to primary dopamine blocking actions of these agents, rather than nonselective or idiosyncratic effects.

Subjective Effects

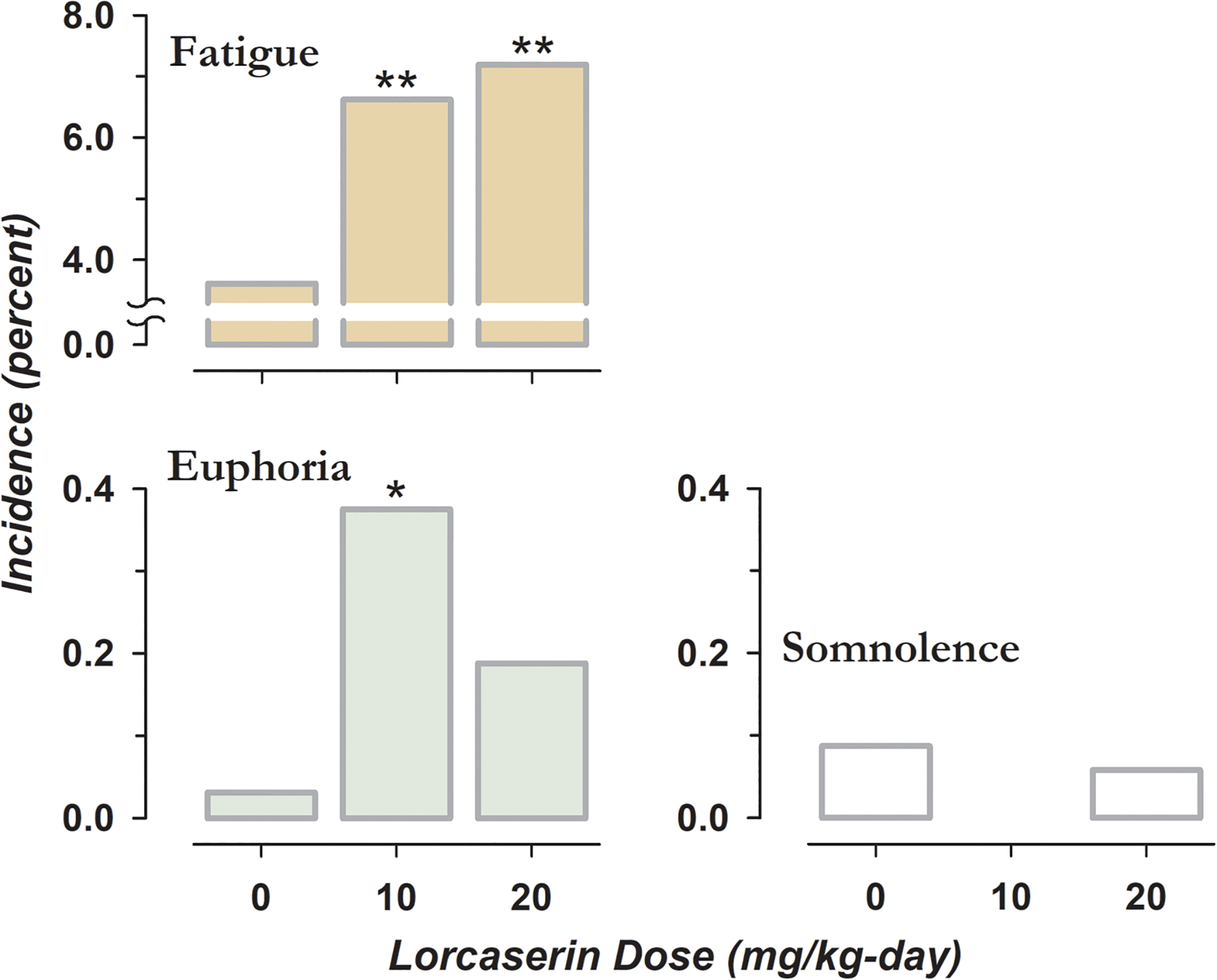

After being illegally marketed by “no prescription” online vendors (Liang et al., 2013), lorcaserin would eventually be marketed in the United States as a controlled substance. The unusual symptom of euphoria was reported by patients receiving lorcaserin during medically-indicated weight loss, especially in those receiving a single daily dose (Figure 2). Pretreatment with low-dose lorcaserin increased the magnitude of drug-induced ‘high’ following intravenous placebo or low-dose cocaine (Pirtle et al., 2019). The incidence of euphoric mood rose linearly during abuse liability testing, approaching a value of one in five participants who received the highest dose of lorcaserin (Shram et al., 2011).

Figure 2. Selected Adverse Effects of Lorcaserin prior to Approval.

Incidence of fatigue, somnolence, and euphoria in patients receiving lorcaserin for medically-indicated weight loss during phase III testing (Food and Drug Administration Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, 2011). Patients were assigned to oral placebo or 10 mg of lorcaserin administered once or twice-daily. * indicates a significant difference in the proportion of subjects between placebo and active treatments by Chi-square test, with one and two symbols corresponding to p < 0.001 and p < 0.0001, respectively.

Lorcaserin also produced linear increases in negative subjective effects, with at least one adverse event reported by all subjects receiving a 60 mg supratherapeutic dose in the study by Shram (2011). When administered at 3 to 6 mg/kg to rodents, lorcaserin produces overt signs that have been interpreted as feelings of malaise; including flattened posture, salivation, and oral gaping (Higgins et al., 2020). We speculate that positive and negative subjective effects underlie increases and decreases in drug taking after low- and high- dose lorcaserin respectively.

In contrast, dopamine antagonists have not consistently increased the positive subjective effects of cocaine. However, enhanced ratings of drug value (Evans et al., 2001) and increased drug taking (Haney et al., 2001, Haney et al., 2011) have been reported. Increases in accumbal levels of dopamine may underlie effects of low-dose lorcaserin (Navailles et al., 2008) or dopamine antagonists (Moghaddam et al., 1990, Kuroki et al., 1999, Park et al., 2019).

Shaping Natural Behaviors through Thresholds

According to the threshold model (Grasing, 2016), low-level, phasic increases in neurotransmitter function are repeated because of their positive subjective and reinforcing properties, with further more persistent increases avoided because of aversive effects. This may be analogous to modest 5-HT2CR activation associated with enhanced euphoria, dopamine release, and increased drug-reinforced behavior. Rather than an off-target or nonspecific effect, negative subjective effects may provide adaptive value when linked to relatively large and long-lasting increases in 5-HT2CR tone. The net effect is to reinforce behavior that maintains endogenous neurotransmission between lower and upper thresholds.

Summary

Lorcaserin, dopamine antagonists, and other classes with variable abuse potential are associated with biphasic effects on reward; with enhancement and inhibition caused by low- and high- doses respectively. Although well-tolerated, the previously approved dose of lorcaserin was likely too low to reliably attenuate drug taking in treatment-seeking patients with cocaine use disorder. Doses that consistently attenuated drug taking in animals were more than 10-fold greater.

Increases in cocaine-reinforced behavior were reported after chronic treatment with relatively low doses of lorcaserin and acute or chronic treatment with low- to intermediate- dose dopamine antagonists. In addition to its potential to enhance stimulant reward, lorcaserin was marketed in some countries as a controlled substance. Susceptibility to biphasic effects likely reflects the underlying physiology of the reward system.

Role of Funding Sources

This study was supported by grant I01 BX004748-01 issued to KG by the issued to KG by the Medical Research Service, Department of Veterans Affairs, Washington, DC, 20420 and grant 1R21DA037556-01 issued to KG by the National Institutes of Health, Institute on Drug Abuse, Bethesda, MD 20892. Neither funding agency was involved in the preparation of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Financial and Competing Interests Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest pertaining to this manuscript.

Off-Label (Unapproved) Drug Use

This manuscript discusses use of lorcaserin and different dopamine antagonist (antipsychotic) medications for treatment of substance abuse disorders. Readers are advised that this indication is not approved by the Food and Drug Administration for any of the compounds discussed. In other words, use of these compounds to treat substance abuse disorders is investigational.

References

- Althoff KN, Leifheit KM, Park JN, Chandran A and Sherman SG (2020). Opioid-related overdose mortality in the era of fentanyl: Monitoring a shifting epidemic by person, place, and time. Drug Alcohol Depend 216:108321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anastasio NC, Sholler DJ, Fox RG, Stutz SJ, Merritt CR, Bjork JM, et al. (2020). Suppression of cocaine relapse-like behaviors upon pimavanserin and lorcaserin co-administration. Neuropharmacology 168:108009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Augier E, Vouillac C and Ahmed SH (2012). Diazepam promotes choice of abstinence in cocaine self-administering rats. Addict Biol 17:378–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ban TA (2007). Fifty years chlorpromazine: a historical perspective. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 3:495–500. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks ML and Negus SS (2017). Repeated 7-day treatment with the 5-HT2C agonist lorcaserin or the 5-HT2A antagonist pimavanserin alone or in combination fails to reduce cocaine vs food choice in male rhesus monkeys. Neuropsychopharmacology 42:1082–1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechtholt AJ and Mark GP (2002). Enhancement of cocaine-seeking behavior by repeated nicotine exposure in rats. Psychopharmacology 162:178–185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bounthavong M, Suh K, Li M, Spoutz PM, Stottlemyer BA and Sepassi A (2021). Trends in healthcare expenditures and resource utilization among a nationally representative population with opioids in the United States: a serial cross-sectional study, 2008 to 2017. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy 16:80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd-Kimball D, Gonczy K, Lewis B, Mason T, Siliko N and Wolfe J (2019). Classics in Chemical Neuroscience: Chlorpromazine. ACS Chem Neurosci 10:79–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozarth MA and Wise RA (1981). Heroin reward is dependent on a dopaminergic substrate. Life Sci 29:1881–1886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt L, Jones JD, Martinez S, Manubay JM, Mogali S, Ramey T, et al. (2020). Effects of lorcaserin on oxycodone self-administration and subjective responses in participants with opioid use disorder. Drug Alcohol Depend 208:107859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bubar MJ and Cunningham KA (2008). Prospects for serotonin 5-HT2R pharmacotherapy in psychostimulant abuse. Prog Brain Res 172:319–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caine SB and Koob GF (1994). Effects of dopamine D-1 and D-2 antagonists on cocaine self-administration under different schedules of reinforcement in the rat. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 270:209–218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castells X, Cunill R, Pérez-Mañá C, Vidal X and Capellà D (2016). Psychostimulant drugs for cocaine dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 9:Cd007380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan B, Kondo K, Freeman M, Ayers C, Montgomery J and Kansagara D (2019). Pharmacotherapy for Cocaine Use Disorder-a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med 34:2858–2873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins GT and France CP (2018). Effects of lorcaserin and buspirone, administered alone and as a mixture, on cocaine self-administration in male and female rhesus monkeys. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol 26:488–496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins GT, Gerak LR, Javors M and France CP (2015). Lorcaserin reduces the discriminative stimulus and reinforcing effects of cocaine in rhesus monkeys. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 356:85–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Deurwaerdère P, Ramos M, Bharatiya R, Puginier E, Chagraoui A, Manem J, et al. (2020). Lorcaserin bidirectionally regulates dopaminergic function site-dependently and disrupts dopamine brain area correlations in rats. Neuropharmacology 166:107915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Wit H and Wise RA (1977). Blockade of cocaine reinforcement in rats with the dopamine receptor blocker pimozide, but not with the noradrenergic blockers phentolamine or phenoxybenzamine. Can J Psychol 31:195–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Chiara G (1995). The role of dopamine in drug abuse viewed from the perspective of its role in motivation. Drug Alcohol Depend 38:95–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiPalma D, Rezvani AH, Willette B, Wells C, Slade S, Hall BJ, et al. (2019). Persistent attenuation of nicotine self-administration in rats by co-administration of chronic nicotine infusion with the dopamine D(1) receptor antagonist SCH-23390 or the serotonin 5-HT(2C) agonist lorcaserin. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 176:16–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ettenberg A, Pettit HO, Bloom FE and Koob GF (1982). Heroin and cocaine intravenous self-administration in rats: mediation by separate neural systems. Psychopharmacology 78:204–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans SM, Walsh SL, Levin FR, Foltin RW, Fischman MW and Bigelow GE (2001). Effect of flupenthixol on subjective and cardiovascular responses to intravenous cocaine in humans. Drug Alcohol Depend 64:271–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filip M and Bader M (2009). Overview on 5-HT receptors and their role in physiology and pathology of the central nervous system. Pharmacol Rep 61:761–777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Food and Drug Administration Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (2011). NDA 022529, Lorcaserin hydrochloride, Arena Pharmaceuticals: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2012/022529Orig022521s022000MedR.pdf.

- Fukushiro DF, Alvarez Jdo N, Tatsu JA, de Castro JP, Chinen CC and Frussa-Filho R (2007). Haloperidol (but not ziprasidone) withdrawal enhances cocaine-induced locomotor activation and conditioned place preference in mice. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 31:867–872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerak LR, Collins GT and France CP (2016). Effects of lorcaserin on cocaine and methamphetamine self-administration and reinstatement of responding previously maintained by cocaine in Rhesus monkeys. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 359:383–391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerrits MA, Petromilli P, Westenberg HG, Di Chiara G and Van Ree JM (2002). Decrease in basal dopamine levels in the nucleus accumbens shell during daily drug-seeking behaviour in rats. Brain Res 924:141–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glowa JR and Wojnicki FH (1996). Effects of drugs on food- and cocaine-maintained responding, III: Dopaminergic antagonists. Psychopharmacology 128:351–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grasing K (2016). A threshold model for opposing actions of acetylcholine on reward behavior: Molecular mechanisms and implications for treatment of substance abuse disorders. Behav Brain Res 312:148–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grasing KW, Xu H and Idowu JY (2019). The muscarinic agonist pilocarpine modifies cocaine-reinforced and food-reinforced responding in rats: comparison with the cholinesterase inhibitor tacrine. Behav Pharmacol 30:478–489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyon A, Assouly-Besse F, Biala G, Puech AJ and Thiébot MH (1993). Potentiation by low doses of selected neuroleptics of food-induced conditioned place preference in rats. Psychopharmacology 110:460–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han J, Xu Y, Yu CX, Shen J and Wei YM (2008). Melatonin reverses the expression of morphine-induced conditioned place preference through its receptors within central nervous system in mice. Eur J Pharmacol 594:125–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haney M, Rubin E and Foltin RW (2011). Aripiprazole maintenance increases smoked cocaine self-administration in humans. Psychopharmacology 216:379–387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haney M, Ward AS, Foltin RW and Fischman MW (2001). Effects of ecopipam, a selective dopamine D1 antagonist, on smoked cocaine self-administration by humans. Psychopharmacology 155:330–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey-Lewis C, Li Z, Higgins GA and Fletcher PJ (2016). The 5-HT(2C) receptor agonist lorcaserin reduces cocaine self-administration, reinstatement of cocaine-seeking and cocaine induced locomotor activity. Neuropharmacology 101:237–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins GA and Fletcher PJ (2003). Serotonin and drug reward: focus on 5-HT2C receptors. Eur J Pharmacol 480:151–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins GA, Fletcher PJ and Shanahan WR (2020). Lorcaserin: A review of its preclinical and clinical pharmacology and therapeutic potential. Pharmacol Ther 205:107417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins GA, Silenieks LB, Rossmann A, Rizos Z, Noble K, Soko AD, et al. (2012). The 5-HT2C receptor agonist lorcaserin reduces nicotine self-administration, discrimination, and reinstatement: relationship to feeding behavior and impulse control. Neuropsychopharmacology 37:1177–1191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell LL and Byrd LD (1995). Serotonergic modulation of the behavioral effects of cocaine in the squirrel monkey. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 275:1551–1559. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell LL and Cunningham KA (2015). Serotonin 5-HT2 receptor interactions with dopamine function: implications for therapeutics in cocaine use disorder. Pharmacol Rev 67:176–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang CC, Liang YC, Lee CC, Wu MY and Hsu KS (2009). Repeated cocaine administration decreases 5-HT(2A) receptor-mediated serotonergic enhancement of synaptic activity in rat medial prefrontal cortex. Neuropsychopharmacology 34:1979–1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Indave BI, Minozzi S, Pani PP and Amato L (2016). Antipsychotic medications for cocaine dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 3:Cd006306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johns SE, Keyser-Marcus L, Abbate A, Boone E, Van Tassell B, Cunningham KA, et al. (2021). Safety and preliminary efficacy of lorcaserin for cocaine use disorder: a phase I randomized clinical trial. Front Psychiatry 12:666945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleven MS and Woolverton WL (1990). Effects of continuous infusions of SCH 23390 on cocaine- or food-maintained behavior in rhesus monkeys. Behav Pharmacol 1:365–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohut SJ and Bergman J (2018). Lorcaserin decreases the reinforcing effects of heroin, but not food, in rhesus monkeys. Eur J Pharmacol 840:28–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuroki T, Meltzer HY and Ichikawa J (1999). Effects of antipsychotic drugs on extracellular dopamine levels in rat medial prefrontal cortex and nucleus accumbens. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 288:774–781. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leccese AP and Lyness WH (1984). The effects of putative 5-hydroxytryptamine receptor active agents on D-amphetamine self-administration in controls and rats with 5,7-dihydroxytryptamine median forebrain bundle lesions. Brain Res 303:153–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leggio GM, Cathala A, Moison D, Cunningham KA, Piazza PV and Spampinato U (2009). Serotonin2C receptors in the medial prefrontal cortex facilitate cocaine-induced dopamine release in the rat nucleus accumbens. Neuropharmacology 56:507–513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin ED, Johnson JE, Slade S, Wells C, Cauley M, Petro A, et al. (2011). Lorcaserin, a 5-HT2C agonist, decreases nicotine self-administration in female rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 338:890–896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin ED, Slade S, Johnson M, Petro A, Horton K, Williams P, et al. (2008). Ketanserin, a 5-HT2 receptor antagonist, decreases nicotine self-administration in rats. Eur J Pharmacol 600:93–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang BA, Mackey TK, Archer-Hayes AN and Shinn LM (2013). Illicit online marketing of lorcaserin before DEA scheduling. Obesity (Silver Spring) 21:861–864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier EY, Ledesma RT, Seiwell AP and Duvauchelle CL (2008). Diazepam alters cocaine self-administration, but not cocaine-stimulated locomotion or nucleus accumbens dopamine. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 91:202–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez D, Narendran R, Foltin RW, Slifstein M, Hwang DR, Broft A, et al. (2007). Amphetamine-induced dopamine release: markedly blunted in cocaine dependence and predictive of the choice to self-administer cocaine. Am J Psychiatry 164:622–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattson CL, Tanz LJ, Quinn K, Kariisa M, Patel P and Davis NL (2021). Trends and geographic patterns in drug and synthetic opioid overdose deaths - United States, 2013–2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 70:202–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mello NK and Negus S (1996). Preclinical evaluation of pharmacotherapies for treatment of cocaine and opioid abuse using drug self-administration procedures. Neuropsychopharm 14:375–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mello NK, Negus SS, Lukas SE, Mendelson JH, Sholar JW and Drieze J (1995). A primate model of polydrug abuse: cocaine and heroin combinations. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 274:1325–1337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercer AJ, Hentges ST, Meshul CK and Low MJ (2013). Unraveling the central proopiomelanocortin neural circuits. Front Neurosci 7:19–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer JM (2018). Pharmacotherapy of psychosis and mania. Goodman & Gilman’s: The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. Brunton LL, Knollmann BC and Hilal-Dandan R. New York, McGraw Hill Medical. [Google Scholar]

- Moghaddam B and Bunney BS (1990). Acute effects of typical and atypical antipsychotic drugs on the release of dopamine from prefrontal cortex, nucleus accumbens, and striatum of the rat: an in vivo microdialysis study. J Neurochem 54:1755–1760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nann-Vernotica E, Donny EC, Bigelow GE and Walsh SL (2001). Repeated administration of the D1/5 antagonist ecopipam fails to attenuate the subjective effects of cocaine. Psychopharmacology 155:338–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Drug Abuse (2020). Lorcaserin in the treatment of cocaine use disorder, https://clinicaltrials.gov identifier NCT03007394. Bethesda, MD, NIH: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03007394. [Google Scholar]

- Navailles S, Moison D, Cunningham KA and Spampinato U (2008). Differential regulation of the mesoaccumbens dopamine circuit by serotonin2C receptors in the ventral tegmental area and the nucleus accumbens: an in vivo microdialysis study with cocaine. Neuropsychopharmacology 33:237–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neelakantan H, Holliday ED, Fox RG, Stutz SJ, Comer SD, Haney M, et al. (2017). Lorcaserin suppresses oxycodone self-administration and relapse vulnerability in rats. ACS Chem Neurosci 8:1065–1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negus SS and Banks ML (2020). Learning from lorcaserin: lessons from the negative clinical trial of lorcaserin to treat cocaine use disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology 45:1967–1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negus SS and Mello NK (2003). Effects of chronic d-amphetamine treatment on cocaine- and food-maintained responding under a progressive-ratio schedule in rhesus monkeys. Psychopharmacology 167:324–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negus SS, Mello NK, Lamas X and Mendelson JH (1996). Acute and chronic effects of flupenthixol on the discriminative stimulus and reinforcing effects of cocaine in rhesus monkeys. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 278:879–890. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nestler EJ, Hyman SM and Malenka RC (2020). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience. New York, The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Newton TF, Reid MS, De La Garza R, Mahoney JJ, Abad A, Condos R, et al. (2008). Evaluation of subjective effects of aripiprazole and methamphetamine in methamphetamine-dependent volunteers. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 11:1037–1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panlilio LV, Secci ME, Schindler CW and Bradberry CW (2017). Choice between delayed food and immediate opioids in rats: treatment effects and individual differences. Psychopharmacology 234:3361–3373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardo B, Taylor J, Caulkins J, Reuter P and Kilmer B (2021). The dawn of a new synthetic opioid era: the need for innovative interventions. Addiction 116:1304–1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park SH, Song YS, Moon BS, Lee BC, Park HS and Kim SE (2019). Combination of in vivo [(123)I]FP-CIT SPECT and microdialysis reveals an antipsychotic drug haloperidol-induced synaptic dopamine availability in the rat midbrain and striatum. Exp Neurobiol 28:602–611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peroutka SJ and Synder SH (1980). Relationship of neuroleptic drug effects at brain dopamine, serotonin, alpha-adrenergic, and histamine receptors to clinical potency. Am J Psychiatry 137:1518–1522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirtle JL, Hickman MD, Boinpelly VC, Surineni K, Thakur HK and Grasing KW (2019). The serotonin-2C agonist Lorcaserin delays intravenous choice and modifies the subjective and cardiovascular effects of cocaine: A randomized, controlled human laboratory study. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 180:52–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platt DM, Rowlett JK and Spealman RD (2002). Behavioral effects of cocaine and dopaminergic strategies for preclinical medication development. Psychopharmacology 163:265–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pompeiano M, Palacios JM and Mengod G (1994). Distribution of the serotonin 5-HT2 receptor family mRNAs: comparison between 5-HT2A and 5-HT2C receptors. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 23:163–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramaekers JG, Louwerens JW, Muntjewerff ND, Milius H, de Bie A, Rosenzweig P, et al. (1999). Psychomotor, Cognitive, extrapyramidal, and affective functions of healthy volunteers during treatment with an atypical (amisulpride) and a classic (haloperidol) antipsychotic. J Clin Psychopharmacol 19:209–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson NR, Smith AM and Roberts DC (1994). A single injection of either flupenthixol decanoate or haloperidol decanoate produces long-term changes in cocaine self-administration in rats. Drug Alcohol Depend 36:23–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richelson E (1988). Neuroleptic binding to human brain receptors: relation to clinical effects. Ann N Y Acad Sci 537:435–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts DC, Loh EA, Baker GB and Vickers G (1994). Lesions of central serotonin systems affect responding on a progressive ratio schedule reinforced either by intravenous cocaine or by food. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 49:177–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocha BA, Goulding EH, O’Dell LE, Mead AN, Coufal NG, Parsons LH, et al. (2002). Enhanced locomotor, reinforcing, and neurochemical effects of cocaine in serotonin 5-hydroxytryptamine 2C receptor mutant mice. J Neurosci 22:10039–10045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romach MK, Glue P, Kampman K, Kaplan HL, Somer GR, Poole S, et al. (1999). Attenuation of the euphoric effects of cocaine by the dopamine D1/D5 antagonist ecopipam (SCH 39166). Arch Gen Psychiatry 56:1101–1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth BL, Willins DL, Kristiansen K and Kroeze WK (1998). 5-Hydroxytryptamine2-family receptors (5-hydroxytryptamine2A, 5-hydroxytryptamine2B, 5-hydroxytryptamine2C): where structure meets function. Pharmacol Ther 79:231–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeman P (2013). Are dopamine D2 receptors out of control in psychosis? Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 46:146–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharretts J, Galescu O, Gomatam S, Andraca-Carrera E, Hampp C and Yanoff L (2020). Cancer risk associated with lorcaserin - the FDA’s review of the CAMELLIA-TIMI 61 trial. N Engl J Med 383:1000–1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherer MA, Kumor KM and Jaffe JH (1989). Effects of intravenous cocaine are partially attenuated by haloperidol. Psychiatry Res 27:117–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shram MJ, Schoedel KA, Bartlett C, Shazer RL, Anderson CM and Sellers EM (2011). Evaluation of the abuse potential of lorcaserin, a serotonin 2C (5-HT2C) receptor agonist, in recreational polydrug users. Clin Pharmacol Ther 89:683–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SG and Davis M (1973). Haloperidol effects on morphine self-administration: testing for pharmacological modification of the primary reinforcement mechanism. Psychol Rec 23:215–221. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder SH (1996). Drugs and the Brain. New York, NY, Scientific American Library Series. [Google Scholar]

- Spyraki C, Fibiger HC and Phillips AG (1983). Attenuation of heroin reward in rats by disruption of the mesolimbic dopamine system. Psychopharmacology 79:278–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinbusch HWM, Dolatkhah MA and Hopkins DA (2021). Anatomical and neurochemical organization of the serotonergic system in the mammalian brain and in particular the involvement of the dorsal raphe nucleus in relation to neurological diseases. Prog Brain Res 261:41–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stinus L, Nadaud D, Deminière JM, Jauregui J, Hand TT and Le Moal M (1989). Chronic flupentixol treatment potentiates the reinforcing properties of systemic heroin administration. Biol Psychiatry 26:363–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoops WW, Lile JA, Lofwall MR and Rush CR (2007). The safety, tolerability, and subject-rated effects of acute intranasal cocaine administration during aripiprazole maintenance. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 33:769–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan LC, Clarke WP and Berg KA (2015). Atypical antipsychotics and inverse agonism at 5-HT2 receptors. Curr Pharm Des 21:3732–3738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tecott LH, Sun LM, Akana SF, Strack AM, Lowenstein DH, Dallman MF, et al. (1995). Eating disorder and epilepsy in mice lacking 5-HT2c serotonin receptors. Nature 374:542–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson J, Stansfeld JL, Cooper RE, Morant N, Crellin NE and Moncrieff J (2020). Experiences of taking neuroleptic medication and impacts on symptoms, sense of self and agency: a systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative data. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 55:151–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomsen WJ, Grottick AJ, Menzaghi F, Reyes-Saldana H, Espitia S, Yuskin D, et al. (2008). Lorcaserin, a novel selective human 5-hydroxytryptamine2C agonist: in vitro and in vivo pharmacological characterization. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 325:577–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Townsend EA, Negus SS, Poklis JL and Banks ML (2020). Lorcaserin maintenance fails to attenuate heroin vs. food choice in rhesus monkeys. Drug Alcohol Depend 208:107848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valencia-Torres L, Olarte-Sanchez CM, Lyons DJ, Georgescu T, Greenwald-Yarnell M, Myers MG Jr., et al. (2017). Activation of ventral tegmental area 5-HT2C receptors reduces incentive motivation. Neuropsychopharmacology 42:1511–1521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermeulen JM, van Rooijen G, van de Kerkhof MPJ, Sutterland AL, Correll CU and de Haan L (2019). Clozapine and Long-Term Mortality Risk in Patients With Schizophrenia: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Studies Lasting 1.1–12.5 Years. Schizophr Bull 45:315–329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veselinović T, Schorn H, Vernaleken I, Schiffl K, Hiemke C, Zernig G, et al. (2011). Effects of antipsychotic treatment on psychopathology and motor symptoms. A placebo-controlled study in healthy volunteers. Psychopharmacology 218:733–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Fowler JS, Logan J, Gatley SJ, Hitzemann R, et al. (1997). Decreased striatal dopaminergic responsiveness in detoxified cocaine-dependent subjects. Nature 386:830–833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westerink BH and de Vries JB (1989). On the mechanism of neuroleptic induced increase in striatal dopamine release: brain dialysis provides direct evidence for mediation by autoreceptors localized on nerve terminals. Neurosci Lett 99:197–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willette BKA, Nangia A, Howard S, DiPalma D, McMillan C, Tharwani S, et al. (2019). Acute and chronic interactive treatments of serotonin 5HT(2C) and dopamine D(1) receptor systems for decreasing nicotine self-administration in female rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 186:172766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood M and Reavill C (2007). Aripiprazole acts as a selective dopamine D2 receptor partial agonist. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 16:771–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yahyavi-Firouz-Abadi N, Tahsili-Fahadan P, Ghahremani MH and Dehpour AR (2007). Melatonin enhances the rewarding properties of morphine: involvement of the nitric oxidergic pathway. J Pineal Res 42:323–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokel RA and Wise RA (1975). Increased lever pressing for amphetamine after pimozide in rats: implications for a dopamine theory of reward. Science 187:547–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]