Abstract

The ring–opening metathesis polymerization (ROMP) of cyclopropenes using hydrazonium initiators is described. The initiators, which are formed by the condensation of 2,3-diazabicyclo[2.2.2]octane and an aldehyde, polymerize cyclopropene monomers by a sequence of [3+2] cycloaddition and cycloreversion reactions. This process generates short chain polyolefins (Mn ≤ 9.4 kg/mol) with relatively low dispersities (Đ ≤ 1.4). The optimized conditions showed efficiency comparable to that achieved with Grubbs’ 2nd generation catalyst for the polymerization of 3-methyl-3-phenylcyclopropene. A positive correlation between monomer to initiator ratio and degree of polymerization was revealed through NMR spectroscopy.

Keywords: Ring-opening metathesis polymerization, ROMP, polymerization, cyclopropene, carbonyl-olefin metathesis

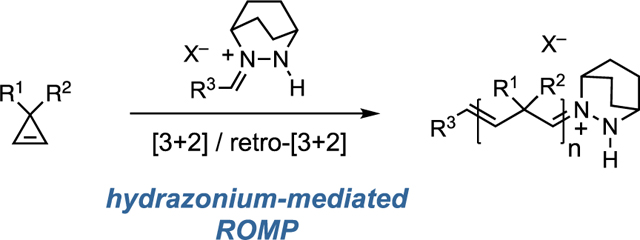

Graphical Abstract

The metal–free ring–opening metathesis polymerization (ROMP) of 3,3-disubstituted cyclopropenes with hydrazonium initiators ultilizing the principle of carbonyl–olefin metathesis is demonstrated.

Ring-opening metathesis polymerization (ROMP) is used extensively in both industrial and fine-chemical synthesis to convert feedstock cyclic olefins into high-value polymers.[1–3] These unique polymerizations have been enabled by a variety of heterogeneous and homogeneous transition metal catalysts, including those based on tungsten,[4–6] titanium,[7–9] tantalum,[10,11] niobium,[11] rhenium,[12] iron,[13] vanadium,[14–19] and especially ruthenium[20–22] and molybdenum[5,6,23] complexes (Figure 1A). While the impact of these reactions on the field of chemistry, and indeed human society, has been profound, there are some well-recognized drawbacks to the use of transition metal reagents. In particular, issues of potential toxicity,[24–27] expense, scarcity, and complex purification[28,29] can complicate the utilization of ROMP polymers. In addition, certain applications such as those involving biomedical devices or electronics are incompatible with polymeric materials that contain metal impurities. Thus, there has been an interest in the discovery of non-metal alternatives for ROMP.[30] Most notable in this regard, Boydston developed an elegant photoredox-mediated ROMP that utilized vinyl ethers as the propagating functionality.[31,32] Despite the highly creative and useful nature of this chemistry, issues of generality and scalability present challenges for its wider adoption. Thus, the development of alternatives to metal-based ROMP chemistries remains a goal of high interest.

Figure 1.

A. Metal alkylidene-mediated ROMP. B. Catalytic cycle for hydrazine-catalyzed carbonyl-olefin metathesis and the alternative hydrazonium-mediated ROMP of cyclopropenes.

Conceptually related to olefin metathesis, carbonyl-olefin metathesis has emerged as a prominent area of research over the past decade.[33–45] In 2012, our group reported the first catalytic strategy for a carbonyl-olefin metathesis ultilizing hydrazine catalysts.[46] In this chemistry, hydrazonium intermediates and [3+2]-cycloadditions / cycloreversions play an analogous role to the metal alkylidenes and [2+2] processes found in traditional olefin metathesis. While closure of the catalytic cycle for this carbonyl-olefin metathesis reaction requires hydrolysis of the metathesized hydrazonium intermediate 1 (Figure 1B), we recognized that preventing this step could allow for the engagement of an additional olefin substrate in the cycloaddition / cycloreversion sequence. In this case, the transformation would be an olefin metathesis, and iteration would result in a ROMP reaction. Such a process would be closely analogous to the metal alkylidene based approach but would utilize only a simple organic initiator. In this Communication, we demonstrate the feasibility of this proposal with the hydrazonium-initiated ring-opening metathesis polymerization of cyclopropenes.

Schrock, Binder, Buchmeiser, and Xia have demonstrated the formation of homopolymers with unique elastomeric properties from selected 1,1- and 1,2-disubstituted cyclopropenes.[47–53] Recently, through fine-tuning the electronic and steric properties of 1-alkyl/aryl-1-(benzoyloxymethyl)-cyclopropenes, Xia has realized precise single addition of cyclopropene in polynorbornene block copolymers or in alternating ROMP (AROMP) with less strained cyclic olefins.[54–57] As these works demonstrate, the intriguing physical properties of polycyclopropenes and the relative paucity of methods to access them warrant a continued interest in cyclopropene ROMP.

As a first indication that the hydrazonium-mediated ROMP described above might be viable, we observed that reaction of benzaldehyde (2) and cyclopropene 3 with 10 mol% of various hydrazine salts at 90 °C in dichloroethane (DCE) led to the production of the ring-opening carbonyl-olefin metathesis (ROCOM) product 4 contaminated by various amounts of oligomeric products 5 (Table 1). A brief survey of conditions revealed that both the structure of the hydrazine and the co-acid salt impacted the ratio of these two products. Pyrazolidine A was the least efficient and generated only the ROCOM adduct 4 in low yield (entry 1), while [2.2.1]-bicyclic hydrazine B led to an 8:1 mixture in favor of 4, regardless of the co-acid (entries 2 and 3). On the other hand, the [2.2.2]-bicyclic hydrazine C resulted in the largest proportions of the oligomeric product 5 (entries 4–6). The co-acid impacted this ratio, with the largest proportion of oligomer (~33%) formed with the bis-HBF4 salt of C. We presume that the amount of oligomer formation was inversely proportional to the propensity of the ring-opened hydrazonium intermediates (1 in Figure 1B) to undergo hydrolysis. The observed oligomerization of cyclopropene 3 suggested that it held promise as a monomer to achieve a proof-of-principle demonstration of hydrazonium-mediated ROMP.

Table 1.

Observation of ROMP products in the catalytic ROCOM of cyclopropene 3.[a]

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| entry | hydrazine | HX | yield (%) | 4:5 |

|

| ||||

| 1 | A | HCl | 5 | 100:0 |

| 2 | B | HCl | 75 | 8:1 |

| 3 | B | TFA | 69 | 8:1 |

| 4 | C | HCl | 80 | 5:1 |

| 5 | C | TFA | 79 | 6:1 |

| 6 | C | HBF4 | 78 | 2:1 |

|

| ||||

| ||||

See ESI for experimental details. Yields reflect isolated and purified ROCOM product.

To parlay the findings shown in Table 1 into a cyclopropene ROMP reaction (Table 2), we sought to suppress chain-end hydrolysis by using preformed hydrazonium 6 as the initiator. Thus 6 was prepared by the condensation of the bistetrafluoroborate salt of hydrazine C with benzaldehyde (2). Tetrafluoroborate was chosen as the counterion based on the results described above and because of the high crystallinity and relative non-hygroscopicity it imparted to the hydrazonium 6. After the reaction of cyclopropene monomer 3 with this initiator 6 (40:1) at 60 °C for 60 h, the polymerization was terminated by hydrolysis at 90 °C for two hours with water (20 equiv) and TFA (2 equiv). The polymeric product 5 was then recovered via centrifugal precipitation from CH2Cl2/MeCN. GPC analysis referenced to polystyrene standards revealed the number average molar mass (Mn) to be 6.1 kDa with a dispersity (Đ) of 1.5. Despite the relatively good agreement between the theoretical and experimental Mn, repeated trials resulted in variable results (Mn as low as 3.6 kDa or as high as 9.2 kDa, Table S1).

Table 2.

Optimization of ROMP of cyclopropene 3 with hydrazonium 6.[a]

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| entry | temp (°C) | DP | Mn theo (kDa) | Mn exp (kDa) | Ð | yield (%) |

|

| ||||||

| 1[b] | 60 | 46 | 5.2 | 6.1 | 1.5 | 25 |

| 2 | 70 | 50 | 5.2 | 6.6 | 1.3 | 23 |

| 3 | 80 | 35 | 5.2 | 4.6 | 1.3 | 27 |

| 4 | 90 | 25 | 5.2 | 3.4 | 1.3 | 29 |

| 5 | 100 | 29 | 5.2 | 3.9 | 1.3 | 18 |

| 6[c] | 90 | 0 | 5.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 7[d] | 90 | 0 | 5.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

See ESI for experimental details. The degree of polymerization (DP), was calculated from Mn exp. Yields reflect isolated and purified polymer.

Reaction time 60 h.

No initiator was used.

NEt3·HBF4 used instead of 6.

In order to ensure the validity and reproducibility of the results, the temperature optimization for the ROMP reaction was performed in triplicate (Table 2, entry 1–3, Table S1, entry 1–6), or quadruplicate (Table 2, entry 4–5, Table S1, entry 7–12). Assessment of the optimized conditions was done on the basis of reproducibility of the obtained polymer chain length and Đ. Among the temperatures screened between 60–100 °C, 90 °C provided the most consistent experimental Mn between quadruplicate runs and resulted in the highest average yield while maintaining a relatively low Đ. Therefore, the optimal temperature for ROMP of cyclopropene 3 was determined to be 90 °C.

Control experiments with no initiator (entry 6), or using an ammonium salt NEt3·HBF4 (entry 7) did not result in polymerization products. In the absence of initiator, 3-methyl-3-phenylcyclopropene largely underwent thermal decomposition after being heated at 90 °C for 18 hours. In the presence of NEt3·HBF4, however, the starting material decomposed completely and gave rise to a complex mixture. While this complex mixture of side products was observed in all crude reactions, attempts to isolate and identify such products were unsuccessful. These control experiments demonstrated that the [2.2.2]-hydrazonium 6 was an active ROMP initiator for cyclopropene 3 and that the thermal degradation of cyclopropene under acidic condition likely inhibits high yielding polymerization.

Consistent with our previous report with Houk,[58] density functional theory (DFT) calculations using the M06–2X functional revealed that cycloaddition (ΔG‡CA = 18.2 kcal/mol) was the rate-determining step during initiation rather than the more facile cycloreversion (ΔG‡CR = 12.1 kcal/mol). More importantly the subsequent, propagating cycloadditions were predicted to be slower than that of the initiation (ΔG‡propagate = 19.6 kcal/mol). These calculations support our observation of relatively narrow molar mass distributions (Đ ≤ 1.4), which are typically associated with well-controlled polymerizations.

To investigate if the polymer chain length could be further extended, the monomer to initiator ratio (M/I) was increased to 80 or 160 (Table 3, entries 1 and 2). At a cyclopropene loading of 160, the average molecular weight increased to 6.9 kDa while the Đ was 1.4. However, the relatively low yield, along with the discrepancy between the targeted and experimental Mn values, underscored the fact that acid-catalyzed thermal decomposition reactions still posed a challenge.

Table 3.

Effect of higher cyclopropene loading table and scope table in [2.2.2]-hydrazonium initiated ROMP.[a]

| |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| entry | Initiator | Cyclopropene | M/l | Mn theo (kDa) | Mn exp (kDa) | Ð | % yield |

|

| |||||||

| 1 | 6 | 3 | 80 | 10.4 | 5.1 | 1.3 | 25 |

| 2 | 6 | 3 | 160 | 20.8 | 6.9 | 1.4 | 20 |

| 3[b] | 11 | 3 | 100 | 13.1 | 5.9 | 1.6 | 30 |

| 4 | 12 | 3 | 80 | 10.5 | 3.4 | 1.3 | 22 |

| 5 | 6 | 8 | 80 | 11.9 | 9.4 | 1.2 | 6 |

|

| |||||||

| |||||||

See ESI for experimental details. Yields reflect isolated and purified polymer.

Stirred at room temperature for 24 h in DCM (0.2 M), then terminated with ethyl vinyl ether (0.1 eq) and polymer was precipitated by addition to methanol.

While the molybdenum catalysts pioneered by Schrock are undisputably the state of the art in 3-methyl-3-phenylcyclopropene ROMP,[47,48,50] allowing access to highly tactic polymers with controlled stereochemistry, they also require more stringent handling conditions. Thus, we felt that the Grubbs 2nd generation catalyst, which has similar handling conditions to the hydrazoniums described here, offered a more direct comparison. We note that Grubbs’ 2nd generation catalyst 11, while able to effect ROMP with cyclopropene, did not result in a substantially larger polymer or a better yield compared to the hydrazonium initiator (entry 3). Additionally, the larger dispersity (Đ = 1.6) was likely the result of a slow initiation rate of the Ru–benzylidene species at room temperature (prior literature reported 54% consumption of 11 after 1 h and 95% consumption after 15 h).[47] Buchmeiser and co-workers addressed this issue of slow initiation by increasing the reaction temperature to 50 °C, leading to complete consumption of the initiator within 46 minutes.[49] Nevertheless, most reported Ru–benzylidene initiated polymerization trials to produce large polymers have been conducted at room temperature, under the conjecture that higher temperatures could cause decomposition of the monomer and/or result in large Đ values. For example, while Buchmeiser and co-workers reported that alkylidene 11-initiated ROMP resulted in low dispersity values (Đ ≤ 1.4)[49] at various M/I loadings; the targeted and experimental Mn values for those reactions disagreed by 34% on average, with the lowest being 2% at the lowest targeted molecular weight, and up to 67% at the highest monomer loading.[49] This discrepancy, as observed with both hydrazonium 6- and ruthenium alkylidene 11-initiated polymerizations, speaks to the inherent instability of the highly strained cyclopropene 3 under these reaction conditions.

To demonstrate the utilization of an alternative initiator, hydrazonium 12 gave rise to the terminal fluorine-tagged polymer 9 (entry 4, Mn = 3.6 kDa, Đ =1.4). In addition, the utilization of a different cyclopropene monomer 8 led to the production of the corresponding polymer 10 (entry 5, Mn = 9.4 kDa, Đ =1.2).

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) of polymer 5 revealed a glass transition temperature (Tg) of 48.1 °C and no observable melting transition (Tm). The lower Tg than reported[49] is likely due to the shorter chain length of the polymer and its atactic nature, which was confirmed by 13C NMR analysis. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) of the polymer showed a relatively high decomposition temperature of 300 °C, which was lower than the reported 395–396 °C of polymer initiated by 11.[49]

Mechanistic investigation of hydrazonium-initiated polymerization was attempted through in situ NMR reaction monitoring. Diffusion filtered NMR acertained that the aldehyde signal, and more importantly, the styrenyl chain-end used to estimate degree of polymerization, belonged to the polymer. Chain length measurement obtained by 1H NMR analysis was comparable to the values obtained from differential refractive index GPC (GPC-DRI) referenced to polystyrene standards and multi angle light scattering GPC (GPC-MALS) (dn/dc measured in THF= 0.2149, DPGPC-DRI = 49, DPGPC-MALS = 50, DPNMR = 65).

Our attempt to correlate monomer conversion with polymer chain extension over time was complicated by the rapid decomposition of the monomer (42% conversion after 27 minutes and 69% conversion after 87 minutes), in contrast to the slower rate of initiation (9% hydrazonium initiated after 27 minutes and 27% hydrazonium initiated after 87 minutes) (Fig. S10). As postulated (vide supra), this observation offers a viable explanation for the lower than expected experimental Mn at elevated temperatures. Furthermore, the propagating chain was highly sentitive to hydrolysis, as brief exposure to air (<2 s) prompted termination of the growing polymer.

Cyclopropene 13 demonstrated higher-order oligomerization with increasing M/I loading (Figure 2). With the aldehyde signal (δ 9.71 ppm) of the ROCOM alkenal 14 as reference, the abundance of oligomers 15 incrementally increased from <5% under stoichiometric conditions to 80% when the M:I was 7:1. The distribution of lower ordered oligomers (up to the tetramer), could be clearly determined by their aldehydic proton resonances. While this study did not provide a definitive linear relationship of monomer consumption versus chain length, chiefly due to thermal decomposition of the cyclopropene monomers, it demonstrated evidence of a positive correlation between M/I ratio and the degree of polymerization.

Figure 2.

Stacked NMRs of cyclopropene 13 oligomerization by in situ initiator generation via [2.2.2]-hydrazinium 3·C and benzaldehyde, 2, with increasing M/I loading from 1:1 to 7:1. Stacked NMRs are scaled by the aldehyde signal of ROCOM product, alkenal 14.

The current work demonstrates that polycyclopropenes can be accessed with simple hydrazonium initiators, thus demonstrating the ability to access ROMP polymers without metals or irradiation. For 3-methyl-3-phenylcyclopropene monomers, the efficiency of the hydrazonium initiator was comparable to that of Grubbs’ 2nd generation catalyst. Although the current system is not viable for polymerization of some more common monomers like norbornene, we anticipate that the development of more reactive initiators will enable a broader range of monomers and expand the application of this non-metal ROMP platform.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Anthony Condo from Cornell Center for Materials Research Shared Facilities for help with thermal characterization. Financial support for this work was provided by the National Institutes of Health (R35GM127135). This work made use of the Cornell University NMR Facility, which is supported, in part, by the NSF through MRI award CHE-1531632. Additionally, this work made use of the Cornell Center for Materials Research Shared Facilities which are supported through the NSF MRSEC program (DMR-1719875).

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is given via a link at the end of the document.

References

- [1].Sutthasupa S, Shiotsuki M, Sanda F, Polym. J. 2010, 42, 905–915. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Bielawski CW, Grubbs RH, in Controlled and Living Polymerizations (Eds.: Mller AHE, Matyjaszewski K), Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim, Germany, 2009, pp. 297–342. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Smith D, Pentzer EB, Nguyen ST, Polymer Revs. 2007, 47, 419–459. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Schrock RR, Feldman J, Cannizzo LF, Grubbs RH, Macromolecules 1987, 20, 1169–1172. [Google Scholar]

- [5].Autenrieth B, Jeong H, Forrest WP, Axtell JC, Ota A, Lehr T, Buchmeiser MR, Schrock RR, Macromolecules 2015, 48, 2480–2492. [Google Scholar]

- [6].Schrock RR, Chem. Rev. 2009, 109, 3211–3226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Gilliom LR, Grubbs RH, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1986, 108, 733–742. [Google Scholar]

- [8].Risse W, Grubbs RH, Journal of Molecular Catalysis 1991, 65, 211–217. [Google Scholar]

- [9].Dono K, Huang J, Ma H, Qian Y, J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2000, 77, 3247–3251. [Google Scholar]

- [10].Wallace KC, Schrock RR, Macromolecules 1987, 20, 448–450. [Google Scholar]

- [11].VenkatRamani S, Roland CD, Zhang JG, Ghiviriga I, Abboud KA, Veige AS, Organometallics 2016, 35, 2675–2682. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Frech CM, Blacque O, Schmalle HW, Berke H, Adlhart C, Chen P, Chem. Eur. J. 2006, 12, 3325–3338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Belov DS, Mathivathanan L, Beazley MJ, Martin WB, Bukhryakov KV, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 2934–2938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Yamada J, Fujiki M, Nomura K, Organometallics 2005, 24, 2248–2250. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Nomura K, Hou X, Organometallics 2017, 36, 4103–4106. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Nomura K, Hou X, Dalton Trans. 2017, 46, 12–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Hayashibara H, Hou X, Nomura K, Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 13559–13562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Kawamoto Y, Elser I, Buchmeiser MR, Nomura K, Organometallics 2021, 40, 2017–2022. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Farrell WS, Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 2021, 647, 584–592. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Vougioukalakis GC, Grubbs RH, Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 1746–1787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Ogba OM, Warner NC, O’Leary DJ, Grubbs RH, Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018, 47, 4510–4544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Yasir M, Liu P, Tennie IK, Kilbinger AFM, Nat. Chem. 2019, 11, 488–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Schrock RR, Acc. Chem. Res. 2014, 47, 2457–2466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Taylor J, Keith S, Cseh L, Ingerman L, Chappell L, Rhoades J, Hueber A, “Vanadium | Toxicological Profile | ATSDR,” can be found under https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/ToxProfiles/tp58.pdf, 2012.

- [25].Todd DG, Keith S, Faroon O, Buser M, Ingerman L, Citra M, Diamond G, Hard C, Klotzbach J, Nguyen A, “Toxicological Profile for Molybdenum,” can be found under https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/toxprofiles/tp212.pdf, 2020.

- [26].Yasbin RE, Matthews CR, Clarke MJ, Chemico-Biological Interactions 1980, 31, 355–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Ciftci O, Beytur A, Vardi N, Ozdemir I, Drug Development and Industrial Pharmacy 2012, 38, 40–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Vougioukalakis GC, Chem. Eur. J. 2012, 18, 8868–8880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Wheeler P, Phillips JH, Pederson RL, Org. Process Res. Dev. 2016, 20, 1182–1190. [Google Scholar]

- [30].Lu P, Kensy VK, Tritt RL, Seidenkranz DT, Boydston AJ, Acc. Chem. Res. 2020, 53, 2325–2335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Goetz AE, Boydston AJ, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 7572–7575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Goetz AE, Pascual LMM, Dunford DG, Ogawa KA, Knorr DB, Boydston AJ, ACS Macro Lett. 2016, 5, 579–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Soicke A, Slavov N, Neudörfl J-M, Schmalz H-G, Synlett 2011, 2011, 2487–2490. [Google Scholar]

- [34].Ludwig JR, Zimmerman PM, Gianino JB, Schindler CS, Nature 2016, 533, 374–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Ma L, Li W, Xi H, Bai X, Ma E, Yan X, Li Z, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 10410–10413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Albright H, Vonesh HL, Becker MR, Alexander BW, Ludwig JR, Wiscons RA, Schindler CS, Org. Lett. 2018, 20, 4954–4958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Tran UPN, Oss G, Pace DP, Ho J, Nguyen TV, Chem. Sci. 2018, 9, 5145–5151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Catti L, Tiefenbacher K, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 14589–14592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Ni S, Franzén J, Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 12982–12985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Pitzer L, Sandfort F, Strieth-Kalthoff F, Glorius F, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 16219–16223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Tran UPN, Oss G, Breugst M, Detmar E, Pace DP, Liyanto K, Nguyen TV, ACS Catal. 2019, 9, 912–919. [Google Scholar]

- [42].Djurovic A, Vayer M, Li Z, Guillot R, Baltaze J-P, Gandon V, Bour C, Org. Lett. 2019, 21, 8132–8137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Wang R, Chen Y, Shu M, Zhao W, Tao M, Du C, Fu X, Li A, Lin Z, Chem. Eur. J. 2020, 26, 1941–1946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Rivero-Crespo MÁ, Tejeda-Serrano M, Pérez-Sánchez H, Cerón-Carrasco JP, Leyva-Pérez A, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 3846–3849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Albright H, Davis AJ, Gomez-Lopez JL, Vonesh HL, Quach PK, Lambert TH, Schindler CS, Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 9359–9406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Griffith AK, Vanos CM, Lambert TH, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 18581–18584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Singh R, Czekelius C, Schrock RR, Macromolecules 2006, 39, 1316–1317. [Google Scholar]

- [48].Singh R, Schrock RR, Macromolecules 2008, 41, 2990–2993. [Google Scholar]

- [49].Binder WH, Kurzhals S, Pulamagatta B, Decker U, Manohar Pawar G, Wang D, Kühnel C, Buchmeiser MR, Macromolecules 2008, 41, 8405–8412. [Google Scholar]

- [50].Flook MM, Gerber LCH, Debelouchina GT, Schrock RR, Macromolecules 2010, 43, 7515–7522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Elling BR, Su JK, Xia Y, Chem. Commun. 2016, 52, 9097–9100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Dumas A, Tarrieu R, Vives T, Roisnel T, Dorcet V, Baslé O, Mauduit M, ACS Catal. 2018, 6, 3257–3262. [Google Scholar]

- [53].Su JK, Jin Z, Zhang R, Lu G, Liu P, Xia Y, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 17771–17776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Elling BR, Xia Y, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 9922–9926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Elling BR, Su JK, Feist JD, Xia Y, Chem 2019, 5, 2691–2701. [Google Scholar]

- [56].Elling BR, Su JK, Xia Y, ACS Macro Lett. 2020, 9, 180–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Elling BR, Su JK, Xia Y, Acc. Chem. Res. 2021, 54, 356–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Hong X, Liang Y, Griffith AK, Lambert TH, Houk KN, Chem. Sci. 2014, 5, 471–475. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.