Abstract

Extensive media coverage and potential controversy about COVID-19 vaccination during the pandemic may have affected people’s general attitudes towards vaccination. We sought to describe key psychological antecedents related to vaccination and assess how these vary temporally in relationship to the pandemic and availability of COVID-19 vaccination. As part of an ongoing online study, we recruited a national (U.S.) sample of young gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men (N = 1,227) between October 2019 and June 2021, and assessed the “4Cs” (antecedents of vaccination; range = 1–5). Overall, men had high levels of confidence (trust in vaccines; M = 4.13), calculation (deliberation; M = 3.97) and collective responsibility (protecting others; M = 4.05) and low levels of complacency (not perceiving disease risk; M = 1.72). In multivariable analyses, confidence and collective responsibility varied relative to the pandemic phase/vaccine availability, reflecting greater hesitancy during later stages of the pandemic. Antecedents also varied by demographic characteristics. Findings suggest negative effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on key antecedents of general vaccination and identify potential targets for interventions.

Keywords: Vaccination, Vaccine confidence, Vaccine hesitancy, COVID-19, Young adults, Gay and sexual, Men who have sex with men

Introduction

Vaccination is heralded as one of the great public health achievements of the 20th century (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2011), yet a growing number of people in the United States (U.S.) either are hesitant or refuse to receive recommended vaccinations (Olive et al., 2018) and, the World Health Organization identified vaccination hesitancy as one of the ten leading threats to global health in 2019 (World Health Organization, 2019). It is important to monitor hesitancy as new threats—such as coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)—emerge, and new vaccines become available. The World Health Organization characterized COVID-19 as a pandemic in March 2020 (Cucinotta & Vanelli, 2020). Multiple COVID-19 vaccines are now available in the U.S. but, despite widespread vaccine availability, only about 53% of the total U.S. population is considered to be fully vaccinated against COVID-19 as of September 2021 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2021a). Starting during vaccine development, COVID-19 vaccination has received extensive media coverage (Krawczyk et al., 2021) and has been involved in a large amount of controversy including widespread misinformation (Hotez et al., 2021). Controversies about COVID-19 vaccination have centered around several issues, including: vaccine safety and side effects; vaccine efficacy; vaccine shedding; the inclusion of controversial substances in the vaccines; and government infringement (Krawczyk et al., 2021; Loomba et al., 2021; Olive et al., 2018), which are, in turn, associated with hesitancy to receive COVID-19 vaccine (Loomba et al., 2021; Reiter et al., 2020). Importantly, the pandemic and these controversies could also affect vaccination hesitancy more generally (Wiysonge et al., 2021). However, little is known about temporal changes in general vaccination hesitancy during the course of the COVID-19 pandemic. Identifying such temporal changes in vaccination hesitancy is of great public health importance given the large decreases in vaccination rates that have been observed during the pandemic (National Foundation for Infectious Diseases, 2020; Patel Murthy et al., 2021).

Understanding antecedents of vaccination among young adults is important as they are among the age groups with the highest levels of hesitancy to receive a vaccine against COVID-19 (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2021), and experience unique challenges with regards to health care as many are young adults making decisions about their own health care for the first time. These challenges may be further heightened among certain groups, such as young adult gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men (YGBMSM) who report additional barriers to health care such as concerns about disclosing of sexual orientation to a health care provider (Wheldon et al., 2018). We therefore sought to examine how the COVID-19 pandemic affected key psychological antecedents of vaccination among a national sample of YGBMSM in the U.S.

Methods

Participants

Data for this study were collected as part of a randomized controlled trial of an online intervention to increase human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination. The study has been described in detail elsewhere (Reiter, Gower, et al., 2020) and briefly here. Between October 2019 and June 2021, we recruited a convenience sample of YGBMSM through paid advertisements on social media and networking sites (e.g., Facebook, Instagram, Grindr) and outreach to existing research panels. Potential participants were eligible if they: (a) were cisgender male; (b) 18–25 years of age; (c) either self-identified as gay, bisexual, or queer; reported ever having sex with a male; or reported being sexually attracted to males; (d) lived in the U.S.; and (e) had not received any doses of HPV vaccine. After providing informed consent, eligible men were directed to complete baseline survey prior to participation in the intervention. A total of 1,227 participants completed the baseline survey. Participant characteristics are presented in Table 1. Participants received $40 for completing study activities at the baseline timepoint from which the data for this report are drawn. The Institutional Review Board at The Ohio State University approved this study.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics (N = 1,227)

| n | (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| COVID-19 pandemic phasea | ||

| Pre-pandemic | 227 | (22.6) |

| Pandemic | 157 | (12.8) |

| Initial vaccine availability | 504 | (41.1) |

| Widespread vaccine availability | 289 | (23.5) |

| Race and ethnicity | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | 578 | (47.1) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 129 | (10.5) |

| Hispanic | 352 | (28.7) |

| Non-Hispanic other | 168 | (13.7) |

| Educational attainment | ||

| High school or less | 380 | (31.0) |

| Some college or more | 847 | (69.0) |

| Region of residence | ||

| Northeast | 227 | (18.5) |

| Midwest | 225 | (18.3) |

| South | 429 | (35.0) |

| West | 346 | (28.2) |

| Health insurance | ||

| Self/other | 554 | (45.2) |

| Parent’s | 420 | (34.2) |

| None/don’t know | 253 | (20.6) |

| Last preventive health visit | ||

| Within last year | 560 | (45.6) |

| 1–3 years ago | 399 | (32.5) |

| More than 3 years ago | 268 | (21.8) |

| M | (SD) | |

| Age (in years, range = 18–25) | 22.25 | (2.20) |

| Psychological antecedents of vaccination | ||

| Confidence | 4.13 | (0.88) |

| Complacency | 1.72 | (0.93) |

| Calculation | 3.97 | (1.05) |

| Collective Responsibility | 4.08 | (1.01) |

Note. Percentages may not sum to 0 due to rounding. M = mean; SD = standard deviation

Measures

The survey assessed psychological antecedents of vaccination with a short version of the 5Cs scale, which broadly assesses not only vaccine confidence but other relevant psychological antecedents, and has been found to predict vaccination intentions and behavior (Betsch et al., 2018; Wismans et al., 2021). Four agree-disagree items assessed: confidence (trust in vaccines; “I am confident that vaccines are safe”); complacency (not perceiving disease risk; “Vaccination is unnecessary because vaccine-preventable diseases are not common anymore”); calculation (deliberation; “When I think about getting vaccinated, I weigh the benefits and risks and make the best decision possible”); and collective responsibility (protecting others; “When everyone is vaccinated, I don’t have to get vaccinated too”) (Betsch et al., 2018). Items had a 5-point response scale. After reverse-coding responses for collective responsibility, higher scores indicate a greater level of each construct.

To assess the potential effects of the pandemic on psychological antecedents of vaccination, we categorized each participant into one of four COVID-19 pandemic phases based on date of enrollment in the study. The phases were based on milestones relative to the pandemic in the U.S. and included: “pre-pandemic” for participants who enrolled prior to March 11, 2020; “pandemic” for those who enrolled between March 11, 2020 and December 13, 2020; “initial vaccine availability” for participants who enrolled between December 14, 2020 (the day the COVID-19 vaccine was given outside of a clinical trial in the U.S. (Guarino et al., 2020)) and April 18, 2021; and “widespread vaccine availability” for participants who enrolled on or after April 19, 2021 (the first day the vaccine was available to all individuals ages 16 and older in all 50 states and the District of Columbia (Schumaker, 2021).

Analyses

We characterized the sample using descriptive statistics and assessed between-group differences in psychological antecedents of vaccination by COVID-19 pandemic phase using one-way ANOVAs. Each antecedent was examined as a separate outcome variable. Multivariable linear regression models controlling for the following demographic characteristics: race/ethnicity, educational attainment, region of residence within the U.S., health insurance, and preventive health services use. All analyses were conducted in Stata Version 15 (StataCorp, College Station, TX); tests were 2-tailed with a critical alpha of 0.05.

Results

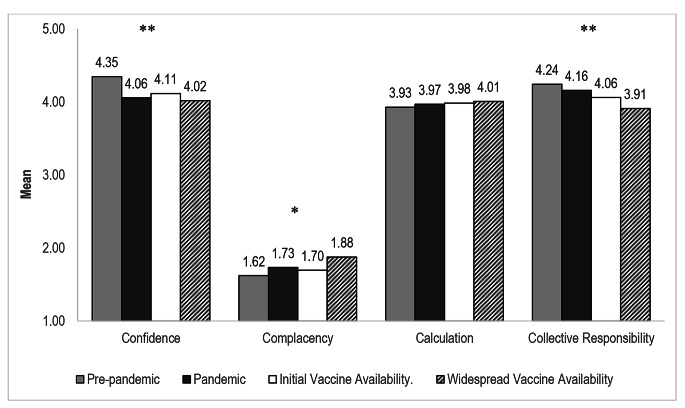

About half (47%) of participants identified as non-Hispanic White and the mean age was about 22 years (Table 1). Most participants had some form of health insurance, either through self (45%) or a parent (34%) but fewer than half had a preventive health visit in the last year (46%). Overall, participants had high levels of confidence (M = 4.13), calculation (M = 3.97) and collective responsibility (M = 4.05) and low levels of complacency (M = 1.72; Table 1). In one-way ANOVAs, these psychological antecedents of vaccination varied across pandemic phases with lower levels of confidence (F(3,1223) = 7.61, p < .001) and collective responsibility (F(3,1223) = 5.57, p < .001; Fig. 1), and greater complacency (F(3,1223) = 3.93, p < .01) among participants who enrolled in the study during later phases of the pandemic compared to pre-pandemic.

Fig. 1.

Psychological Antecedents of Vaccination, by COVID-19 Pandemic Phase

Note. Differences were assessed with one-way ANOVAs.

*p < .01, ** p < .001.

Associations between pandemic phase and two of the antecedents remained statistically significant in multivariable models (Table 2). Compared to participants who enrolled pre-pandemic, those who enrolled during later phases of the pandemic reported lower levels of confidence (pandemic phase: β = −0.22, p < .05, initial vaccine availability phase: β = −0.16, p < .05; widespread vaccine availability phase: β = −0.22, p < .01) and lower levels of collective responsibility (widespread vaccine availability phase: β = −0.26, p < .01). With regards to control variables, psychological antecedents also differed by race/ethnicity, educational attainment, region of residence, health insurance and preventive health services used (Table 2).

Table 2.

Multivariable Correlates of Psychological Antecedents of Vaccination

| Confidence | Complacency | Calculation | Collective Responsibility | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | (SE) | β | (SE) | β | (SE) | β | (SE) | ||||

| COVID-19 pandemic phase | |||||||||||

| Pre-pandemic | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||||||

| Pandemic | -0.22 | (0.08)* | 0.05 | (0.09) | 0.05 | (0.11) | -0.06 | (0.10) | |||

| Initial vaccine availability | -0.16 | (0.06)* | -0.01 | (0.07) | 0.09 | (0.08) | -0.14 | (0.07) | |||

| Widespread vaccine availability | -0.22 | (0.07)** | 0.14 | (0.08) | 0.13 | (0.09) | -0.26 | (0.08)** | |||

| Race and ethnicity | |||||||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||||||

| Non-Hispanic Black | -0.56 | (0.08)*** | 0.50 | (0.09)*** | -0.01 | (0.10) | -0.28 | (0.10)** | |||

| Hispanic | -0.09 | (0.06) | 0.15 | (0.06)* | -0.09 | (0.07) | -0.10 | (0.07) | |||

| Non-Hispanic other | -0.14 | (0.07 | 0.16 | (0.08)* | -0.09 | (0.09) | -0.13 | (0.09) | |||

| Educational attainment | |||||||||||

| High school or less | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||||||

| Some college or more | 0.03 | (0.01)*** | -0.03 | (0.01)*** | 0.01 | (0.01) | 0.02 | (0.01)** | |||

| Region of residence | |||||||||||

| Northeast | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||||||

| Midwest | 0.02 | (0.08) | -0.08 | (0.08) | 0.05 | (0.10) | 0.19 | (0.09)* | |||

| South | 0.05 | (0.07) | -0.10 | (0.08) | 0.02 | (0.09) | 0.10 | (0.08) | |||

| West | 0.01 | (0.07) | -0.06 | (0.08) | -0.04 | (0.09) | 0.20 | (0.09)* | |||

| Health insurance | |||||||||||

| Self/other | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||||||

| Parent’s | 0.16 | (0.06)** | -0.10 | (0.06) | 0.02 | (0.07) | 0.18 | (0.06)** | |||

| None/don’t know | 0.04 | (0.07) | -0.02 | (0.07) | -0.10 | (0.08) | 0.05 | (0.08) | |||

| Last preventive health visit | |||||||||||

| Within last year | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||||||

| 1–3 years ago | -0.16 | (0.06)** | 0.09 | (0.06) | -0.13 | (0.07) | -0.16 | (0.07)* | |||

| More than 3 years ago | -0.13 | (0.06)* | 0.16 | (0.07)* | -0.21 | (0.08)* | -0.23 | 0.08)** | |||

Note. Table presents results of multivariable liner regression models. Each antecedent was examined in a separate model, controlling for all variables listed in the table. β = unstandardized beta regression coefficient; Ref. = referent category; SE = standard error

*p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001

Discussion

This study is among the first we know of to describe general vaccination hesitancy among YGBMSM, a population for whom multiple vaccinations are recommended (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2021b). Vaccination hesitancy has been extensively studied for early childhood and, to a lesser extent, adolescent vaccinations (Betsch et al., 2018; Gilkey et al., 2014; Gilkey et al., 2016), but there is limited information with regards to hesitancy among this population. Although the young adult men in our study held generally positive attitudes and perceptions about vaccination, overall, we found significant decreases in vaccination confidence and collective responsibility among those enrolled during the later phases of the pandemic, which is particularly concerning as other research has found that, of the 4Cs assessed in this study, these two are the most strongly associated with vaccination intent and behavior among college students (Wismans et al., 2021). Although we are not able to identify the exact mechanism for these decreases, many young adults report receiving COVID-19 information on social media (Silva et al., 2021) which has been a source for anti-vaccine content during the pandemic (Hernandez et al., 2021). Thus, strategies to mitigate such content are needed, particularly among YGBMSM and other young adults who may have less experience navigating health care and vaccination decisions independent of their parents or guardians.

Our findings further identify demographic groups that may be at risk of hesitancy. Similar to other research examining vaccination intentions and uptake (Baack et al., 2021; Gilkey et al., 2014; Lu et al., 2021), the patterns of associations with vaccination confidence, complacency and collective responsibility seen in this study suggest greater hesitancy among individuals who are non-Hispanic Black, have lower educational attainment, and who do not receive regular preventive care.

Strengths and limitations

Study strengths include a large, national sample of YGBMSM and a timeframe for data collection that spanned phases of the COVID-19 pandemic thus far, providing a novel opportunity to assess the pandemic’s effects on general vaccination hesitancy. Limitations include the use of cross-sectional data which precludes our ability to examine individual changes over time and a lack of data on constraints (the 5th “C” of the 5 C’s scale (Betsch et al., 2018)) and other factors that may influence hesitancy (e.g., previous vaccination behavior; exposure to vaccination messages; political affiliation). While vaccination items were worded to assess perceptions about vaccination, generally, it is possible that responses were influenced by opinions about COVID-19 vaccination, specifically, due to its salience during the timeframes examined. Finally, our sample was limited to YGBMSM who had not yet received the HPV vaccine, which may reflect different health care experiences and greater hesitancy to receive vaccines, generally, among our study population compared to other populations of young adults.

Conclusions

The COVID-19 pandemic is ongoing. Young adults have lower COVID-19 vaccination rates than other adults (Baack et al., 2021) and continue to need not only COVID-19 vaccine but also other recommended vaccines (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2021b). Understanding how the pandemic has influenced general vaccination antecedents is important for developing future interventions. Our findings suggest that increasing vaccination confidence and collective responsibility may be particularly important among YGBMSM, and identify demographic groups that may benefit from targeted outreach to address vaccination hesitancy.

Acknowledgements

This work was prepared while Dr. Annie-Laurie McRee was employed at the University of Minnesota. The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of the National Institutes of Health, the Department of Health and Human Services, or the United State Government.

Authors’ contributions.

ALM conceptualized and designed the study, conducted data analyses, interpreted data, and drafted the initial manuscript. ALG, PLR and DEK conceptualized and designed the study, consulted on analyses, and interpreted data. All authors reviewed and revised the manuscript, approved the final manuscript as submitted, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding.

The research reported in this publication was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R37CA226682. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Declarations

Conflicts of Interest.

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethics approval.

The Institutional Review Board at the Ohio State University approved all study materials and procedures (#2019C0028).

Consent to participate.

All participants provided informed consent prior to participation in this study.

Consent for publication.

Not applicable.

Availability of data and material.

Not applicable.

Code availability.

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Baack BN, Abad N, Yankey D, Kahn KE, Razzaghi H, Brookmeyer K, Singleton JA. COVID-19 Vaccination Coverage and Intent Among Adults Aged 18–39 Years - United States, March-May 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(25):928–933. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7025e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betsch C, Schmid P, Heinemeier D, Korn L, Holtmann C, Böhm R. Beyond confidence: Development of a measure assessing the 5 C psychological antecedents of vaccination. PLoS One. 2018;13(12):e0208601. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0208601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Ten great public health achievements–United States, 2001–2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(19):619–623. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2021a). September 12, 2021). https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#vaccinations_vacc-total-admin-rate-total. Retrieved from https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2021b). February 12, 2021). Recommended Adult Immunization Schedule for ages 19 years or older, United States, 2021. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/hcp/imz/adult.html

- Cucinotta D, Vanelli M. WHO Declares COVID-19 a Pandemic. Acta Biomed. 2020;91(1):157–160. doi: 10.23750/abm.v91i1.9397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilkey MB, Magnus BE, Reiter PL, McRee AL, Dempsey AF, Brewer NT. The Vaccination Confidence Scale: a brief measure of parents’ vaccination beliefs. Vaccine. 2014;32(47):6259–6265. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilkey MB, McRee AL, Magnus BE, Reiter PL, Dempsey AF, Brewer NT. Vaccination Confidence and Parental Refusal/Delay of Early Childhood Vaccines. PLoS One. 2016;11(7):e0159087. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0159087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guarino, B., Cha, A. E., Wood, J., & Witte, G. (2020). ‘The weapon that will end the war’: First coronavirus vaccine shots given outside trials in U.S. The Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2020/12/14/first-covid-vaccines-new-york/

- Hernandez RG, Hagen L, Walker K, O’Leary H, Lengacher C. The COVID-19 vaccine social media infodemic: healthcare providers’ missed dose in addressing misinformation and vaccine hesitancy. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021;17(9):2962–2964. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2021.1912551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotez, P., Batista, C., Ergonul, O., Figueroa, J. P., Gilbert, S., Gursel, M., & Bottazzi, M. E. (2021). Correcting COVID-19 vaccine misinformation: Lancet Commission on COVID-19 Vaccines and Therapeutics Task Force Members. EClinicalMedicine, 33, 100780. doi:10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.100780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kaiser Family Foundation (2021). COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor Dashboard. Retrieved from https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/dashboard/kff-covid-19-vaccine-monitor-dashboard/

- Krawczyk K, Chelkowski T, Laydon DJ, Mishra S, Xifara D, Gibert B, Bhatt S. Quantifying Online News Media Coverage of the COVID-19 Pandemic: Text Mining Study and Resource. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(6):e28253. doi: 10.2196/28253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loomba S, de Figueiredo A, Piatek SJ, de Graaf K, Larson HJ. Measuring the impact of COVID-19 vaccine misinformation on vaccination intent in the UK and USA. Nat Hum Behav. 2021;5(3):337–348. doi: 10.1038/s41562-021-01056-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu PJ, Hung MC, Srivastav A, Grohskopf LA, Kobayashi M, Harris AM, Williams WW. Surveillance of Vaccination Coverage Among Adult Populations -United States, 2018. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2021;70(3):1–26. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss7003a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Foundation for Infectious Diseases. (2020). Issue Brief: The Impact of COVID-19 on US Vaccination Rates. NFID website

- Olive JK, Hotez PJ, Damania A, Nolan MS. The state of the antivaccine movement in the United States: A focused examination of nonmedical exemptions in states and counties. PLoS Med. 2018;15(6):e1002578. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel Murthy B, Zell E, Kirtland K, Jones-Jack N, Harris L, Sprague C, Gibbs-Scharf L. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Administration of Selected Routine Childhood and Adolescent Vaccinations – 10 U.S. Jurisdictions, March-September 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(23):840–845. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7023a2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiter PL, Gower AL, Kiss DE, Malone MA, Katz ML, Bauermeister JA, McRee AL. A Web-Based Human Papillomavirus Vaccination Intervention for Young Gay, Bisexual, and Other Men Who Have Sex With Men: Protocol for a Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Res Protoc. 2020;9(2):e16294. doi: 10.2196/16294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiter PL, Pennell ML, Katz ML. Acceptability of a COVID-19 vaccine among adults in the United States: How many people would get vaccinated? Vaccine. 2020;38(42):6500–6507. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.08.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumaker, E. (2021). April 19, 2021). All US adults now eligible for COVID-19 vaccines. Retrieved from https://abcnews.go.com/Health/adults-now-eligible-covid-19-vaccines/story?id=77163212

- Silva, J., Bratberg, J., & Lemay, V. (2021). COVID-19 and influenza vaccine hesitancy among college students. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). doi:10.1016/j.japh.2021.05.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Wheldon CW, Daley EM, Walsh-Buhi ER, Baldwin JA, Nyitray AG, Giuliano AR. An Integrative Theoretical Framework for HPV Vaccine Promotion Among Male Sexual Minorities. Am J Mens Health. 2018;12(5):1409–1420. doi: 10.1177/1557988316652937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wismans A, Thurik R, Baptista R, Dejardin M, Janssen F, Franken I. Psychological characteristics and the mediating role of the 5 C Model in explaining students’ COVID-19 vaccination intention. PLoS One. 2021;16(8):e0255382. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0255382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiysonge, C. S., Ndwandwe, D., Ryan, J., Jaca, A., Batouré, O., Anya, B. M., & Cooper, S. (2021). Vaccine hesitancy in the era of COVID-19: could lessons from the past help in divining the future? Hum Vaccin Immunother, 18(1), 1–3. doi:10.1080/21645515.2021.1893062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization (2019). Ten threats to global health in 2019. 2019. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/ten-threats-to-global-health-in-2019