Abstract

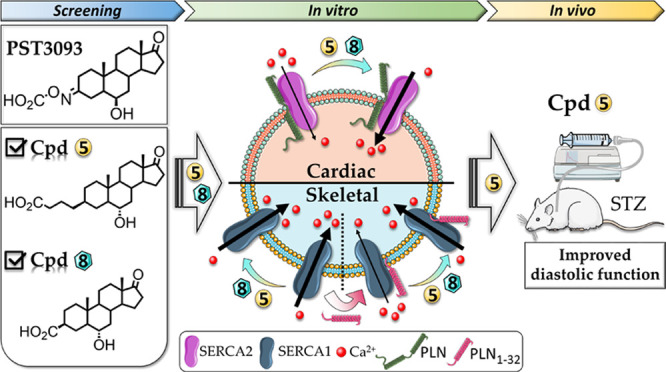

The stimulation of sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase SERCA2a emerged as a novel therapeutic strategy to efficiently improve overall cardiac function in heart failure (HF) with reduced arrhythmogenic risk. Istaroxime is a clinical-phase IIb compound with a double mechanism of action, Na+/K+ ATPase inhibition and SERCA2a stimulation. Starting from the observation that istaroxime metabolite PST3093 does not inhibit Na+/K+ ATPase while stimulates SERCA2a, we synthesized a series of bioisosteric PST3093 analogues devoid of Na+/K+ ATPase inhibitory activity. Most of them retained SERCA2a stimulatory action with nanomolar potency in cardiac preparations from healthy guinea pigs and streptozotocin (STZ)-treated rats. One compound was further characterized in isolated cardiomyocytes, confirming SERCA2a stimulation and in vivo showing a safety profile and improvement of cardiac performance following acute infusion in STZ rats. We identified a new class of selective SERCA2a activators as first-in-class drug candidates for HF treatment.

Introduction

Heart failure (HF) is a life-threatening syndrome characterized by an inability of the heart to meet the metabolic demands of the body. It is age-dependent, ranging from less than 2% of people younger than 60 years to more than 10% of individuals older than 75 years. Most patients with HF have a history of hypertension, coronary artery disease, cardiomyopathies, valve disease, or a combination of these disorders.1 The calculated lifetime risk of developing HF is expected to increase, and those with hypertension are at higher risk.2 Clinical symptoms in HF are caused by a cardiac double pathological feature that consists of diminished systolic emptying (systolic dysfunction) and impaired ability of the ventricles to receive blood from the venous system (diastolic dysfunction). The impaired contractility and relaxation are also caused by an abnormal distribution of intracellular Ca2+, resulting from reduced Ca2+ uptake by the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR).3 SR Ca2+ uptake is operated by the SR Ca2+ ATPase, SERCA2a, a 110 kDa membrane protein. During ion transport across the membrane, SERCA2a undergoes large conformational changes switching between Ca2+-bound E1 and Ca2+-free E2 states.4 SERCA2a activity is physiologically inhibited by the interaction with phospholamban (PLN), a small protein5,6 that stabilizes the E2 state, incompatible with Ca2+ binding.7 SERCA2a inhibition by PLN is normally relieved by PLN phosphorylation with protein kinase A, a signaling pathway severely depressed as a consequence of myocardial remodeling.8 SERCA2a activators are therefore promising drugs that might improve overall cardiac function in HF with reduced arrhythmogenic risk. Various therapeutic approaches that increase SERCA2a function have been recently investigated.9−13 Small-molecule SERCA2a activators have been recently discovered. Among them, a pyridone derivative directly binds to PLN displacing it from SERCA2a14 and a small molecule activates SERCA2a by promoting its SUMOylation [small ubiquitin-related modifier (SUMO)].15 Overall, new SERCA2a activators might be very useful in HF treatment together with the first line of therapeutic agents, β-blockers, and angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors.

The work of our laboratory led to the successful completion of phase IIb clinical trials of the steroid derivative istaroxime,16 which is endowed with a double mechanism of action, that is, Na+/K+ ATPase inhibition17 and SERCA2a activation.18 Istaroxime is an inotropic/lusitropic agent, which is capable of improving both systolic and diastolic functions (HORIZON study)19 with a much lower proarrhythmic effect than digoxin, a pure Na+/K+ ATPase inhibitor.18 This suggests that, by improving Ca2+ clearance from the cytosol,20 SERCA2a stimulation may minimize the proarrhythmic effect of Na+/K+ ATPase blockade18,19,21 while preserving its inotropic effect. Although having an excellent pharmacodynamic profile, istaroxime is not optimal for chronic administration because of its poor gastrointestinal absorption, high clearance rate, and extensive metabolic transformation19 which leads to the formation of a final metabolite, named PST3093. A recent study from our laboratory22 indicates that PST3093 behaves as a selective SERCA2a activator showing a longer half-life than istaroxime and it is likely to account for the lusitropic effect of istaroxime in patients; nonetheless, the presence of the oxime function may still limit the chronic usage of PST3093. The main aim of this work has been the rational design and synthesis of bioisosteric PST3093 analogues with metabolically stable groups replacing the oxime function, with the purpose to maintain the selective activity on SERCA2a. We present here the ligand-based rational design, the synthesis, and the biochemical and pharmacological in vitro and in vivo characterization of a new class of alkene-based PST3093 derivatives that turned out to have selective activity on SERCA2a.

Results

Ligand-Based Rational Design and Synthesis of PST3093-Derived Compounds

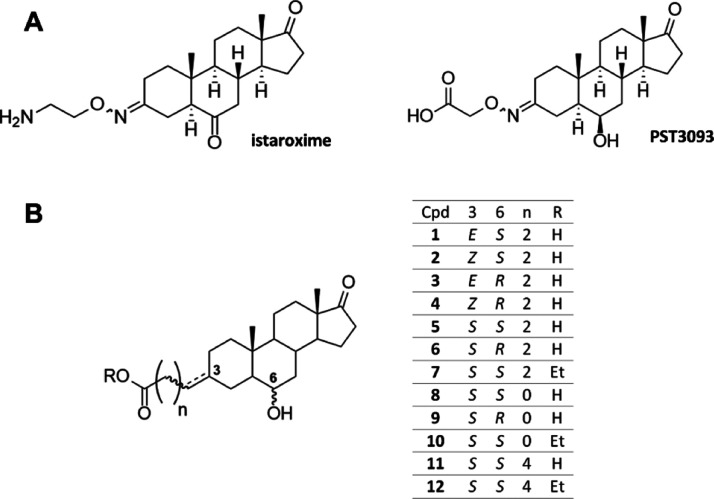

The metabolite PST3093 (Figure 1A) possesses a 17-androstanone core of istaroxime with two main structural differences: a carboxylic acid group instead of amino group on the C3-oxime linker and a hydroxyl group with R configuration (or β-configuration) at C6 instead of istaroxime’s carbonyl. A series of PST3093 variants (compounds 1–12, Figure 1B) has been designed by a ligand-based approach to carry a carboxylic group (acid or ethyl ester) attached through a linker to the C3 position of the 6-hydroxy-17-oxo androstane core. Although structural information and quantitative structure–activity relationship data allowed the identification of the pharmacophore of istaroxime derivatives that binds to Na+/K+ ATPase,16,23 no structural information is available on the interaction between compound PST3093 and SERCA2a and/or PLN. The ligand-based design of compounds 1–12 involved the selective variation of substituents at positions C3 and C6, allowing the pharmacophore identification. The 12 compounds presented here belong to a larger library of synthetic androstane derivatives that were screened for their SERCA2a activity. The need to replace the oxime function with a bioisosteric group guided the design of all derivatives. Namely, the oxime double bond in steroid C3 was replaced with an alkene in compounds 1–4 (in the Z or E configuration) and a saturated C–C bond in the β configuration in compounds 5–12.

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of (A) istaroxime and its metabolite PST3093, and (B) PST3093 synthetic variants 1–12.

The single or double carbon–carbon bonds in C3 would ensure a greater metabolic stability in all compounds compared to PST3093. The length of the C3 linker was also varied: a four-atom linker is present in compounds 1–7 exactly reproducing the PST3093 structure, while a shorter two-atom linker is present in compounds 8, 9 and 10, and a longer six-atom linker is present in compounds 11 and 12. All synthetic compounds have a hydroxyl group at C6 as in PST3093: compounds 3, 4, 6, and 9 are in the (R) configuration as PST3093, all the others are in the (S) configuration.

Compounds 1–12 were synthesized through the synthetic strategy depicted in Scheme 1. Compounds 13 and 14, 6R- and 6S-hydroxyandrostane-3,17-dione, respectively, were prepared as described from the commercially available prasterone (3β-hydroxyandrost-5-en-17-one).16 The lower reactivity of C17 carbonyl compared to that of C3 allowed for the regioselective reaction of the C3 ketones in Wittig or Horner–Emmons reactions, obtaining the insertion of the carboxylic acid or ester functionalities at position C3.

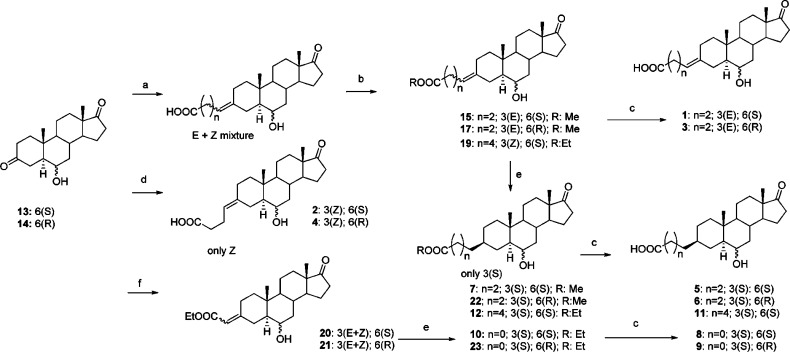

Scheme 1. Synthesis of Compounds 1–12 from the Common Precursors 13 and 14.

Reagents and conditions: (a) NaH, (3-carboxypropyl)triphenylphosphonium or (3-carboxypentyl)triphenylphosphonium bromide, DMSO. (b) EDC, EtOH. E/Z 1:2. (c) aq LiOH 1 M, THF. (d) LiHMDS, (3-carboxypropyl)triphenylphosphonium bromide, THF. (e) H2/Pd–C, EtOAc. (f) triethylphosphonoacetate, NaH, dimethylformamide.

Compounds 1 and 3 were synthesized by reacting compounds 13 and 14, respectively, with (3-carboxypropyl)triphenylphosphonium bromide and sodium hydride in dry dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO), giving the corresponding carboxylic acids (mixture of E + Z isomers 1:2 at C3 alkene) as products of the Wittig reaction that were converted into methyl esters by dissolving in methanol and treating with N-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-N-ethylcarbodiimide (EDC) and 4-(dimethylamino)pyridine. The E and Z isomers of esters were separated by chromatography, giving compounds 15 and 17, respectively. Ethyl ester hydrolysis with aqueous lithium hydroxide in tetrahydrofuran (THF) afforded compounds 1 and 3. The same Wittig reaction using (3-carboxypentyl)triphenylphosphonium bromide followed by ethanol esterification gave compound 19 as a mixture of E + Z isomers. Although the use of sodium hydride as a base for the Wittig reaction gave a mixture of E + Z isomers, by reacting 13 and 14 with the same phosphonium salt in the presence of lithium bis(trimethylsilyl)amide (LiHMDS) in THF, it was possible to obtain stereoselectively only the Z olefins, compounds 2 and 4. The reaction of 13 and 14 with triethylphosphonoacetate in the presence of sodium hydride (Horner–Wadsworth–Emmons reaction) gave the esters 20 and 21 (E + Z mixture).

The catalytic hydrogenation (H2, Pd/C) of compounds 15, 17, 19, 20, and 21 afforded compounds 7, 22, 12, 10, and 23, respectively (Scheme 1). Interestingly, the hydrogenation at the C3 carbon–carbon double bond was found to be completely stereoselective for all derivatives, affording only the β (S) isomers. This is very likely due to the steric hindrance of the C19 methyl group on the upper face of the androstane A ring. Hydrolysis of the esters 7, 22, 12, 10, and 23 by treatment with aqueous lithium hydroxide in THF gave final carboxylic acids 5, 6, 11, 8, and 9, respectively.

New Synthetic Compounds Do Not Affect Na+/K+ ATPase and Stimulate SERCA2a in a PLN-dependent Way

It has been recently shown that although istaroxime inhibits the Na+/K+ ATPase activity (IC50 0.14 μM in dog renal preparations), its metabolite PST3093 is inactive against Na+/K+ ATPase. In contrast, both molecules improve disease-induced SERCA2a depression with a similar potency.22 To assess whether the new PST3093 derivatives retain the pharmacological activity of the parent compound, Na+/K+ ATPase and SERCA2a activities were evaluated in in vitro assays.

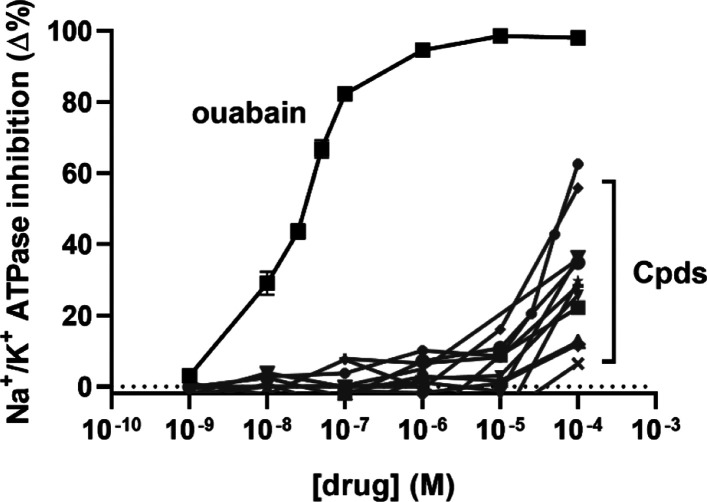

Compounds were tested in a concentration range from 10–9 to 10–4 M on a purified renal Na+/K+ ATPase preparation with a specific activity of 14 μmol/min/mg protein. None of the tested molecules inhibited Na+/K+ ATPase activity up to 10–4 M (Figure 2), similar to PST3093.22

Figure 2.

Na+/K+ ATPase activity inhibition in a dog purified enzyme preparation. All compounds were tested in a concentration range from 10–9 to 10–4 M in comparison to ouabain. (•) Cpd 9 (−62% at 10–4 M), (⧫) Cpd 3 (−55% at 10–4 M), and all the other compounds showed <40% inhibition at 10–4 M (N = 2).

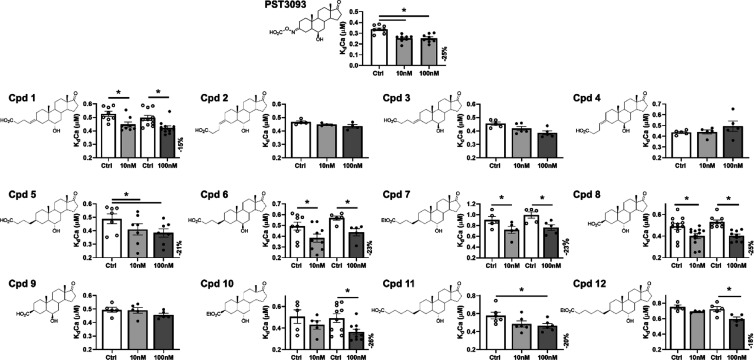

SERCA2a ATPase activity was assessed in SR preparations from healthy guinea pig hearts. Ca2+ dependency of ATPase activity was measured, and kinetic parameters (KdCa and Vmax) were estimated at compound concentrations of 10 and 100 nM. Four compounds (2, 3, 4, and 9) were inactive, while the other eight compounds significantly increased SERCA2a–Ca2+ affinity (decreased KdCa) at nanomolar concentrations (Figure 3). The maximal effect of compounds on KdCa reached −26% at 100 nM, close to that of PST3093 (−25% at 100 nM). No compound affected SERCA2a Vmax activity in healthy guinea pig SR preparations.

Figure 3.

Screening of the compounds by testing their activity on SERCA2a Ca2+ dependency in guinea pig microsomal preparations. Concentration dependency of SERCA2a Ca2+ affinity (KdCa) modulation by all compounds and PST3093 (N = 4–11). All compounds were tested at the concentrations of 10 and 100 nM. PST3093, compounds 5 and 8 were also tested at 1 nM (see text). Data are the mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05 (one-way RM ANOVA plus post hoc Tukey’s multiple comparisons or paired t-test).

Compounds 5–8 and 10 had similar potencies in increasing SERCA2a–Ca2+ affinity (i.e., in stimulating SERCA2a). The activity of compounds 5 and 8 on SERCA2a was further investigated at 1 nM in comparison to PST3093. Also, at this concentration, compounds 5 and 8 increased SERCA2a–Ca2+ affinity (KdCa reduced by 16%, N = 7, p < 0.05 and 14%, N = 12, p < 0.05, respectively) similar to PST3093 (18%, N = 8, p < 0.05), without affecting Vmax; this makes them good candidates for SERCA2a activation.

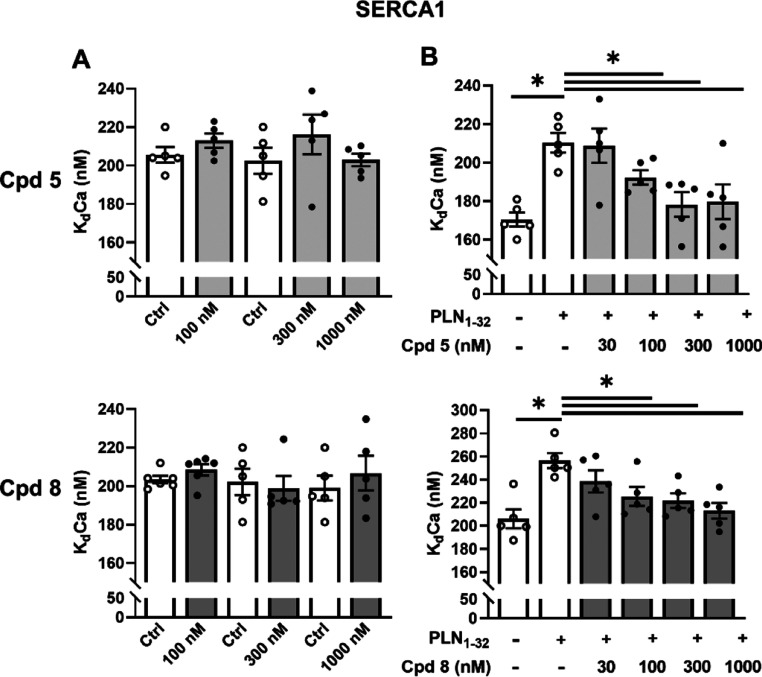

Istaroxime24 and PST309322 stimulated SERCA2a by relieving SERCA2a–PLN interaction. In a range of concentrations from 30 to 1000 nM, compounds 5 and 8 failed to affect skeletal SERCA1 activity in the absence of PLN (Figure 4A). As expected, reconstitution with the PLN1–32 fragment markedly reduced SERCA1 affinity for Ca2+ (KdCa increased by 23–25%), without affecting Vmax. Under this condition, compounds 5 and 8 dose-dependently reversed the PLN-induced shift in KdCa, leaving SERCA1 Vmax unchanged, as previously reported for istaroxime24 and PST3093.22 The present results indicate that in the absence of PLN, SERCA1 is insensitive to compounds 5 and 8; however, sensitivity is restored after reconstitution of SERCA1 with PLN, suggesting that the compounds act by weakening SERCA–PLN interaction, similar to istaroxime24 and PST3093.22

Figure 4.

Effects of compounds 5 and 8 on SERCA1 ATPase activity and its PLN dependency in guinea pig microsomal preparations. Concentration dependency of SERCA1–Ca2+ affinity (KdCa) modulation with compounds 5 and 8 in skeletal muscle microsomes containing SERCA1 alone (A) and after reconstitution with PLN1–32 fragments (B) (N = 5). Data are the mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05 (one-way RM ANOVA plus post hoc Tukey’s multiple comparisons or paired t-test).

Compounds 5 and 8 were further characterized by testing their effects in cardiac preparations from a diabetic rat model [streptozotocin (STZ)-induced] with impaired SERCA2a function.22,25

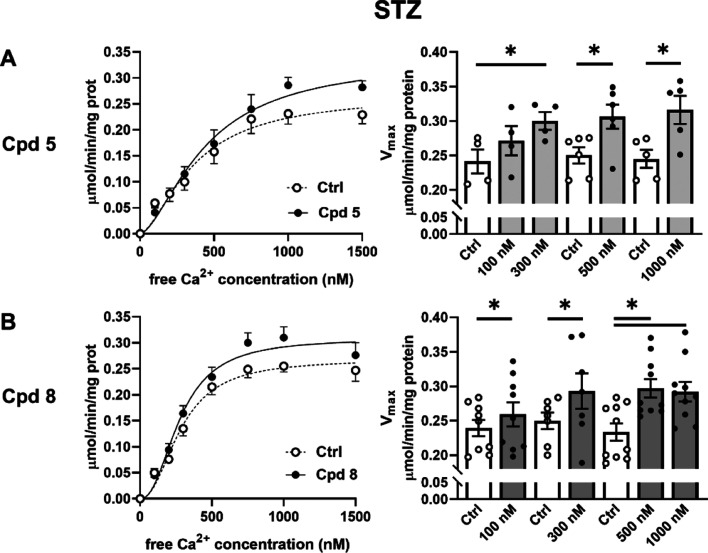

Consistent with our previous reports,22,25 baseline SERCA2a Vmax activity was 30% lower in STZ (0.239 ± 0.012 μmol/min/mg protein, N = 9) than in healthy rats (0.343 ± 0.02 μmol/min/mg protein, N = 8, p < 0.05); SERCA2a KdCa was instead unchanged in STZ rats (healthy 259 ± 22 nM, STZ 293 ± 23 nM, NS). Thus, as previously reported,22,25Vmax may represent a better readout of SERCA2a activity in this species. Over the whole range of concentrations tested, compounds 5 and 8 increased SERCA2a Vmax in STZ rats (+26% and +25%, +17% and +28%, at 300 and 500 nM, respectively) (Figure 5), thus reversing STZ-induced SERCA2a depression. SERCA2a KdCa was unchanged by all compounds. Both compounds failed to affect ATPase Ca2+ dependency in healthy rats in terms of both parameters KdCa and Vmax (Table S1).

Figure 5.

Modulation of SERCA2a ATPase activity in diseased cardiac preparations. Effect of compounds 5 (A) and 8 (B) (concentration range from 100 to 1000 nM) on SERCA2a maximal activity (Vmax) in cardiac homogenates from diabetic (STZ) rats (N = 4–10). Data are the mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05 (one-way RM ANOVA or paired t-test).

In summary, compounds 5 and 8 displayed similar potency in recovering disease-induced depression of SERCA2a ATPase activity in STZ rats, as previously shown for istaroxime25 and PST3093.22

The absence of effects on Na+/K+ ATPase implies that compounds 5 and 8 may represent new selective SERCA2a activators, similar to their precursor PST3093. Compound 5 was selected for further in vitro and in vivo effects.

Compound 5 Stimulates SR Ca2+ Uptake in Isolated STZ Cardiomyocytes

A proof-of-principle evidence that compound 5 stimulates SERCA2a was provided by testing its effects on SR Ca2+ uptake function in isolated STZ cardiomyocytes through the “SR loading” protocol. This protocol (see Methods, Figure S2 and refs (22) and (25)) is suitable to assess SR Ca2+ uptake kinetics following caffeine-induced SR depletion under conditions emphasizing the SERCA2a role, that is, in the absence of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (NCX) function. In particular, through this protocol, we recently showed22 that voltage-induced SR Ca2+ reloading is significantly depressed in STZ myocytes, a functional readout of the depressed SERCA2a function in this model.

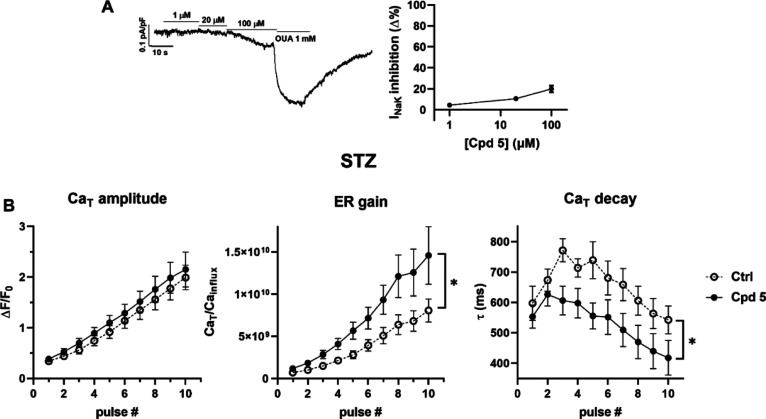

Cells were incubated for at least 30 min with compound 5 at 1 μM, a concentration not affecting Na+/K+ ATPase. Indeed, as shown in Figure 6A, in isolated rat cardiomyocytes, a detectable inhibition of the Na+/K+ ATPase current (INaK) was observed at concentrations higher than 20 μM (−19.8 ± 3.1% at 100 μM, N = 22), likely for PST3093.22

Figure 6.

Modulation of SR Ca2+ uptake under NCX inhibition in V-clamped myocytes from STZ hearts. (A) Na+/K+ ATPase current (INaK) inhibition by compound 5 (n = 22) in rat LV myocytes; INaK recording at increasing concentrations of compound 5 and finally to ouabain (OUA as reference) is shown on the left. Data are the mean ± SEM. (B) Effect of compound 5 on SR Ca2+ loading in patch-clamped STZ myocytes. SR Ca2+ loading by a train of V-clamp pulses was initiated after caffeine-induced SR depletion; NCX was blocked by Na+ substitution to identify SERCA2a-specific effects (see Methods and Figure S2); N = 3, ctrl n = 14, with compound 5, n = 11. Panels from left to right: CaT amplitude, ER gain (the ratio between CaT amplitude and Ca2+ influx through ICaL), and the time constant (τ) of CaT decay. *p ≤ 0.05 for the “interaction factor” in RM two-way ANOVA, indicating a different steepness of curves.

In STZ myocytes, compound 5 (1 μM) sharply accelerated Ca2+ transient (CaT) decay (reducing the CaT decay time constant) and increased excitation release (ER) gain at each pulse of the reloading protocol; CaT amplitude was not significantly affected by the drug (Figure 6B). Comparable results have been obtained with 1 μM PST3093.22

Overall, compound 5 stimulates SR function in diseased myocytes, most likely through SERCA2a enhancement, within the context of an intact cellular environment.

In Vivo Administration of Compound 5 is Safe and Improves STZ-Induced Diastolic Dysfunction

Toxicity

Compound 5 was selected to evaluate in vivo effects of the new class. Acute toxicity (LD50) was preliminarily evaluated in mice following i.v. and oral drug administration. For i.v. administration, compound 5 had an LD50 of 300 mg/kg; for comparison, the LD50 of PST3093 and istaroxime was >25022 and 23 mg/kg,22 respectively. Oral toxicity of compound 5 was >800 mg/kg, as compared to >200 and 200 mg/kg for PST3093 and istaroxime, respectively. The main signs of toxicity were prostration, gasping, and convulsions. No overt signs of acute toxicity were observed in the surviving animals.

Collectively, the present data indicate low toxicity of compound 5, particularly as compared to i.v. istaroxime. This is likely due to lack of inhibitory activity on the Na+/K+ pump, which also applies to istaroxime after its first-pass conversion to PST3093 in the case of oral administration.

In Vivo Hemodynamics

Features of the STZ-induced diabetic cardiomyopathy have been previously assessed by comparing morphometric, echocardiographic, and cellular parameters between healthy and STZ-treated rats under urethane anesthesia.22 Echo measurements in STZ rats indicated primarily an impairment of diastolic function, evidenced by decreased early filling velocity (E), increased E wave deceleration time over the E ratio (DT/E), and decreased protodiastolic TDI relaxation velocity (e′). The systolic function was moderately altered, as shown by larger LV end-systolic diameter (LVESD), reduced ejection fraction, depressed fractional shortening (FS) and systolic tissue velocity (s′).22

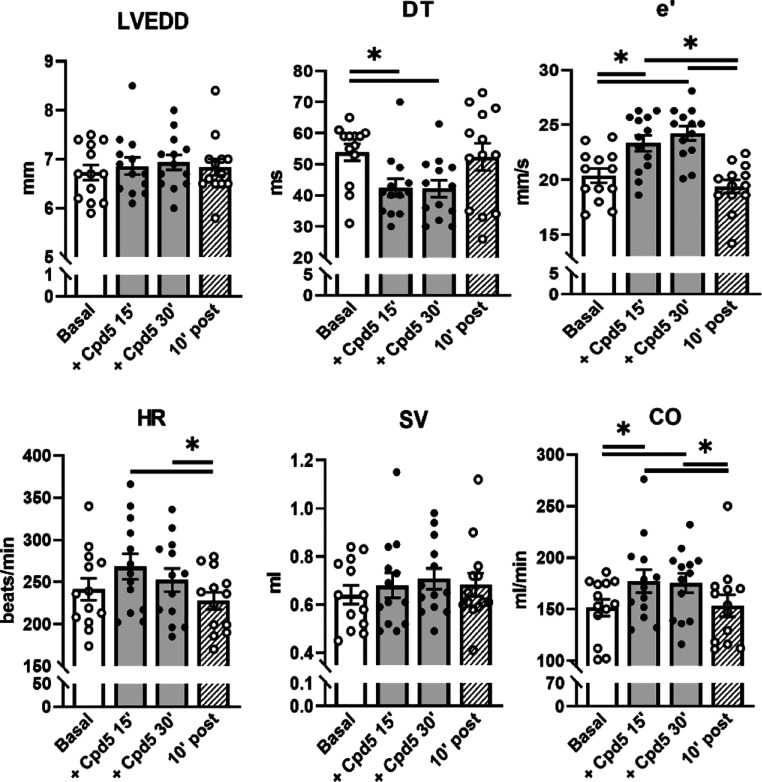

Compound 5 was i.v. infused in STZ rats at a rate of 0.2 mg/kg/min, and the effects on echo parameters were investigated at 15 and 30 min of infusion and 10 min after discontinuation (Figure 7 and Table S2 for all echo parameters). Compound 5 positively affected transmitral Doppler flow indexes by increasing E and A waves; it shortened the DT, reduced the DT/E ratio, and increased both protodiastolic (e′) and telediastolic (a′) TDI relaxation velocities. Compound 5 increased CO, without significantly affecting HR or systolic indexes, such as FS, systolic TDI velocity (s′), or LVESD. Drug effects reached a plateau at 15 min of infusion; 10 min after discontinuation of the infusion, most echo indexes affected by the compound returned to the basal level.

Figure 7.

Effect of compound 5 on in vivo echocardiographic parameters in STZ diabetic rats. Compound 5 was i.v. infused (0.2 mg/kg/min) in rats 8 weeks after STZ treatment. Echocardiographic parameters were measured before (basal) and at 15 and 30 min during drug infusion and 10 min after drug interruption under urethane anesthesia. Data are the mean ± SEM; all the results of echocardiographic indexes are summarized in Table S2; N = 13; *p < 0.05 (one-way RM ANOVA).

To summarize, in vivo hemodynamic data indicate a specific lusitropic effect of compound 5 in STZ rats, compatible with rescue of SERCA2a function and largely comparable to the in vivo effect of the parent drug PST3093.22

Discussion and Conclusions

In spite of the intense research targeting the discovery of small molecules or gene therapy aimed at selectively activating SERCA2a, recognized to be depressed in HF, no promising clinical outcomes have been reached so far. Therefore, there is still a compelling medical need for a compound with positive lusitropic activity. In this context, we successfully developed a new class of derivatives of PST3093 (the long-lasting metabolite of istaroxime)22 with a selective stimulatory action on SERCA2a but devoid of inhibitory activity on Na+/K+ ATPase. This was achieved by replacing the metabolically unstable oxime of PST3093 with more stable saturated and unsaturated carbon–carbon bonds, without altering the molecular geometry. Biological effects of the new compounds have been investigated by in vitro and in vivo assays.

The in vitro tests on SERCA2a clearly point out that replacing the C=N group of PST3093 with an alkene C=C, the activity on SERCA2a is partially retained in the case of E isomers (Figure 3). Indeed, although compound 1 (100 nM), carrying the alkene bond in the E configuration, reduced SERCA2a KdCa by 15%, compound 2 with the same bond in the Z configuration was inactive. However, albeit in the E configuration, compound 3 was less active than compound 1, that is, it showed only a trend to SERCA2a KdCa reduction. For comparison, PST3093 (100 nM) reduced SERCA2a KdCa by 25% in the same guinea pig preparation. The fact that compounds with C=C in the E configuration are active while Z isomers are inactive parallels the observation that the oxime isomer E is the most active in istaroxime.16 The replacement of oxime with a saturated C–C bond in C3 in the beta configuration led to compounds 5–12. Compounds 5–8 and 10, in which the C3 linker is two- and four-carbon atom long, have similar activities. Compounds 11 and 12 with a six-carbon linker are slightly less active.

Among the compounds with significant SERCA2a stimulatory activity, compounds 5 and 8, had the best balance between potency and efficiency of chemical synthesis; thus, they were selected as leads for further evaluations. At nanomolar concentrations, the new compounds enhanced in vitro SERCA2a activity in healthy guinea pig preparations and in diseased (STZ) rat preparations; furthermore, the stimulatory effect on SERCA2a depended on the presence of PLN. This pattern is superimposable on that previously reported for the parent compound PST3093 and suggests that the new compounds may also act by partially relieving SERCA2a from PLN-induced inhibition.22

SR Ca2+ uptake function in diseased (STZ) myocytes was stimulated by compound 5 at a concentration not affecting Na+/K+ ATPase. According to the protocol specificity, this effect is surely attributable to SERCA2a stimulation under conditions of depressed function (STZ-induced SERCA2a downregulation). The parent compound PST3093 also in this case shows similar effects.22

In vivo studies investigated the effects of compound 5 on cardiac function in STZ diabetic rats, a disease model characterized by diastolic dysfunction, as assessed by echocardiography.22 Compound 5 i.v. infusion at a single dose improved diastolic echo indexes and, because of a small increase in the heart rate, cardiac output; however, it did not affect systolic function significantly (Table S2). Although improvement of diastolic indexes mimics the effect of the parent compound, PST3093 also improved systolic indexes.22 Similar to compound 5, PST3093 does not inhibit the Na+/K+ pump; therefore, the reason for this difference remains to be verified.

Evaluation of in vivo acute toxicity after i.v. administration yielded an LD50 of compound 5 comparable to that of PST3093 whereas the oral one was higher, indicating a lower toxicity. The difference between i.v. and oral toxicity may result from the absence of enteric transit/absorption and first-pass hepatic metabolism, which characterize the former administration route. The remarkable reduction of istaroxime toxicity when orally administered can be accounted for by its fast conversion to PST3093, missing Na+/K+ pump inhibition.

Overall, the new PST3093 derivatives provide a tool for pharmacological enhancement of SERCA2a function, leading to improvement of in vivo diastolic function. With respect to PST3093, its derivatives are devoid of the oxime function and thus suitable for chronic usage and have a lower acute oral toxicity. They further differ from istaroxime, the progenitor of “PLN antagonists” already tested for clinical use because of lack of Na+/K+ pump inhibition. Considering the proarrhythmic potential of the latter, this may represent a substantial advantage in terms of safety; nonetheless, at variance with istaroxime, the new compounds should be seen as purely “lusitropic” agents, that is, devoid of “inotropic” effects beyond that expected from systo–diastolic coupling.

Although the mechanism of action of PST3093 and synthetic analogues has still to be investigated, the reversal of electrostatic properties from cationic ammonium for istaroxime to anionic carboxylate for PST3093 and analogues could account for the inactivity toward Na+/K+ ATPase.

Because PST3093 has a half-life (∼10 h) much longer than that of istaroxime (∼1 h)22 and its derivatives have been obtained by introducing groups with higher chemical stability, pharmacokinetics of the new compounds is likely compatible with chronic oral dosing. Nonetheless, suitability of the new compounds for chronic therapy, their natural destination, remains to be directly tested.

Experimental Section

Methods are succinctly described here; details are given in the Supporting Information.

Animal Models

All experiments involving animals confirmed to the guidelines for Animal Care endorsed by the Milano-Bicocca and Chang Gung Universities and to the Directive 2010/63/EU of the European Parliament on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes.

Chemistry

General

All reagents and solvents were purchased from commercial sources and used without further purification. Reactions were carried out under an argon atmosphere unless otherwise noted and were monitored by thin-layer chromatography performed over silica gel 60 F254 plates (Merck), revealed using UV light or with molybdate staining [molybdate phosphorus acid and Ce(IV) sulfate in 4% H2SO4]. Flash chromatography purifications were performed on silica gel 60 (40–63 μm) purchased from commercial sources. 1H and 13C NMR spectra of compounds were recorded with Bruker ADVANCE 400 with TopSpin software or with NMR Varian 400 with VnmrJ software. Chemical shifts are reported in parts per million (ppm) relative to the residual solvent; coupling constants are expressed in Hz. The multiplicity in the 13C spectra was deduced from an attached proton test pulse sequence; peaks were assigned with the help of 2D-COSY and 2D-HSQC and 2D-NOESY experiments. Exact masses were recorded with Orbitrap Fusion Tribrid. Purity of final compounds was about 95% as assessed by high-performance liquid chromatography analysis. Reaction conditions and complete compounds characterization are reported in the Supporting Information.

Biochemical Measurements

Total ATPase activity was assessed by measuring the rate of 32P-ATP release (μmol/min/mg protein) at 37 °C.

Na+/K+ ATPase Activity Assay

The inhibitory effect of compounds was tested at multiple concentrations on Na+/K+ ATPase-alpha1 isoform purified from dog kidneys. Na+/K+ ATPase activity was identified as the ouabain (1 mM)-sensitive component of total one; compound efficacy was expressed as the concentration exerting 50% inhibition (IC50).

SERCA ATPase Activity Assay

Measurements were performed in cardiac SR microsomes (guinea pig) and in whole tissue homogenates (rat). Cardiac preparations included SERCA2a and PLN. To test for PLN involvement in the effect of compounds, SERCA1 activity was measured in PLN-free microsomes (from guinea pig skeletal muscle) before and after reconstitution with the synthetic PLN1–32 inhibitory fragment at a ratio of 300:1 for PLN/SERCA. The SERCA component, identified as the cyclopiazonic acid (10 μM)-sensitive one, was measured at multiple Ca2+ concentrations (100–1500 nM),13 and Ca2+ dose-response curves were fitted to estimate SERCA maximal hydrolytic velocity (Vmax, μmol/min/mg protein) and the Ca2+ dissociation constant (KdCa, nM). Either an increase in Vmax (rat) or a decrease in KdCa (increased Ca2+ affinity) (guinea pig) stands for enhancement of SERCA function.

Functional Measurements in Isolated Cardiomyocytes

LV myocytes were isolated from healthy and STZ rats as previously described26 with minor modifications.

Na+/K+ ATPase Current (INaK)

INaK was recorded in isolated myocytes from healthy rats as the holding current at −40 mV under conditions enhancing INaK and minimizing contamination by other conductances.27INaK inhibition by compound 5 was expressed as percentage reduction of ouabain (1 mM)-sensitive current.

Intracellular Ca2+ Dynamics

Ca2+-dependent fluorescence (Fluo4-AM) was recorded in patch-clamped LV myocytes from STZ rats and quantified by normalized units (F/F0). The SR Ca2+ uptake rate was evaluated through a “SR loading” voltage protocol, specifically devised to examine the system at multiple levels of SR Ca2+ loading and to rule out NCX contribution. Current through the L-type Ca2+ channel (ICaL) was simultaneously recorded, and the ER “gain” was calculated as the ratio between CaT amplitude and Ca2+ influx through ICaL up to the CaT peak22,25 (protocol in Figure S2).

In Vivo Studies

Acute Drug Toxicity Studies in Mice

Acute toxicity of compound 5 was preliminarily evaluated in male Albino Swiss CD-1 mice for determining the dose causing 50% mortality (LD50, mg/kg body weight) at 24 h after i.v. injection or oral treatment. Compound 5 was dissolved in saline solution and i.v. injected at 100, 200, 250, 275, and 300 mg/kg (one–four animals for each group) or orally administered at 100, 200, 400, 600, and 800 mg/kg (four animals for each group). Control animals received the vehicle only.

Acute toxicity following oral treatment with istaroxime and PST3093 was also evaluated for comparison; istaroxime was administered at 30, 100, and 300 mg/kg (four animals for each group) and PST3093 at 200 mg/kg (four animals for each group).

Hemodynamic Studies in Rats with Diabetic Cardiomyopathy

Diabetes was selected as the in vivo model because of its association with reduced SERCA2a function.22,25 Diabetes was induced in Sprague Dawley male rats (150–175 g) by a single i.v. STZ group (50 mg/kg in citrate buffer) injection in the tail vein. Control (healthy group) rats received vehicle (citrate buffer). Fasting glycaemia was measured after 1 week, and rats with values >290 mg/dL were considered diabetic.22,25

Rats were studied by transthoracic echocardiographic under anesthesia (1.25 g/kg urethane, i.p). Left-ventricular end-diastolic (LVEDD) and end-systolic (LVESD) diameter, posterior wall (PWT), and interventricular septal thickness (IVST) were measured according to the American Society of Echocardiography guidelines.16 FS was calculated as FS = (LVEDD – LVESD)/LVEDD. Trans-mitral flow velocity was measured (pulsed Doppler) to obtain early and late filling velocities (E and A waves) and E wave deceleration time (DT). DT was also normalized to E wave amplitude (DT/E ratio). Peak myocardial systolic (s′) and diastolic velocities (e′ and a′) were measured at the mitral annulus by tissue Doppler imaging (TDI).

Compound 5 was i.v. infused at 0.2 mg/kg/min (0.16 mL/min); echocardiographic parameters were measured before and at 15 and 30 min during the infusion and 10 min after drug discontinuation.

Statistical Analysis

Individual means were compared by unpaired or paired t-test; multiple means were compared by one-way ANOVA for repeated measurements (RM) followed by post hoc Tukey’s multiple comparisons. Data are reported as mean ± SEM; p ≤ 0.05 defined statistical significance of differences in all comparisons. The number of animals or cells are specified in each figure legend.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by CVie Therapeutics Limited (Taipei, Taiwan), WindTree Therapeutics (Warrington, USA), and the University of Milano Bicocca. We thank Dr Alberto Cerri, sadly passed away, for his valuable contribution to the structural design of the new compounds. Alberto, you’ll always be in our hearts.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- APT

attached proton test

- 2D-COSY

two-dimension homonuclear correlation spectroscopy

- CO

cardiac output

- CPA

cyclopiazonic acid

- Cpd

compound

- 2D-HSQC

two-dimension heteronuclear single quantum correlation

- 2D-NOESY

two-dimension nuclear Overhauser effect spectroscopy

- DMF

dimethylformamide

- DMSO

dimethylsulfoxide

- DT

E wave deceleration time

- E

early filling velocity

- e′

TDI relaxation velocity

- EDC

N-ethyl-N′-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide

- EF

ejection fraction

- EtOAc

ethyl acetate

- EtOH

ethanol

- FS

fractional shortening

- HPLC

high-performance liquid chromatography

- HF

heart failure

- i.p.

intraperitoneal

- i.v.

intravenous

- HR

heart rate

- IVST

interventricular septal thickness

- LD50

lethal dose 50%

- LVEDD

left-ventricular end-diastolic diameter

- LVESD

left-ventricular end-systolic diameter

- LiHMDS

lithium bis(trimethylsilyl)amide

- PLN

phospholamban

- PWT

posterior wall thickness

- QSAR

quantitative structure–activity relationship

- s′

systolic tissue velocity

- SERCA

sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase

- SR

sarcoplasmic reticulum

- STZ

streptozotocin

- SV

stroke volume

- TDI

tissue Doppler imaging

- THF

tetrahydrofuran

- TLC

thin-layer chromatography

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.jmedchem.2c00347.

Synthetic procedures, characterization of all compounds and intermediates (assignments of 1H and 13C NMR spectra, HRMS, and HPLC spectra), supplementary methods (animal models, biochemical measurements, functional measurements in isolated myocytes, and in vivo studies), supplementary tables (PDF).

Molecular formula strings (CSV).

Author Contributions

F.P., M.R., and A.Z. contributed equally as senior authors to the article. A.L. and A.R. conducted chemical assays; M.F. and P.B. conducted biochemical assays; M.A. and E.T. conducted functional measurements in isolated myocytes; S.-C.H. carried out in vivo measurements; C.R. carried out formal analysis; G.-J.C. supervised in vivo measurements; P.F. and G.B. supervised biochemical measurements; A.Z., M.R., and F.P. revised and supervised the study and wrote the article.

The authors declare the following competing financial interest(s): MF and PB are Windtree employees, PF and GB are Windtree consultants, S-CH is an employee of CVie Therapeutics Limited. All the other Authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Metra M.; Teerlink J. R. Heart Failure. Lancet 2017, 390, 1981–1995. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31071-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd-Jones D. M.; Larson M. G.; Leip E. P.; Beiser A.; D’Agostino R. B.; Kannel W. B.; Murabito J. M.; Vasan R. S.; Benjamin E. J.; Levy D. Lifetime Risk for Developing Congestive Heart Failure. Circulation 2002, 106, 3068–3072. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000039105.49749.6F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bers D. M.; Despa S.; Bossuyt J. Regulation of Ca2+ and Na+ in Normal and Failing Cardiac Myocytes. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 2006, 1080, 165–177. 10.1196/annals.1380.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sitsel A.; De Raeymaecker J.; Drachmann N. D.; Derua R.; Smaardijk S.; Andersen J. L.; Vandecaetsbeek I.; Chen J.; De Maeyer M.; Waelkens E.; Olesen C.; Vangheluwe P.; Nissen P. Structures of the Heart Specific SERCA 2a Ca 2+—ATP Ase. EMBO J. 2019, 38, 1–17. 10.15252/embj.2018100020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bers D. M. Calcium Cycling and Signaling in Cardiac Myocytes. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2008, 70, 23–49. 10.1146/annurev.physiol.70.113006.100455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLennan D. H.; Kranias E. G. Phospholamban: a crucial regulator of cardiac contractility. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2003, 4, 566–577. 10.1038/nrm1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akin B. L.; Hurley T. D.; Chen Z.; Jones L. R. The Structural Basis for Phospholamban Inhibition of the Calcium Pump in Sarcoplasmic Reticulum. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 30181–30191. 10.1074/JBC.M113.501585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y.; Chen J.; Fontes S. K.; Bautista E. N.; Cheng Z. Physiological and Pathological Roles of Protein Kinase A in the Heart. Cardiovasc. Res. 2021, 118, 386–398. 10.1093/cvr/cvab008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne M. J.; Power J. M.; Preovolos A.; Mariani J. A.; Hajjar R. J.; Kaye D. M. Recirculating Cardiac Delivery of AAV2/1SERCA2a Improves Myocardial Function in an Experimental Model of Heart Failure in Large Animals. Gene Ther. 2008, 15, 1550–1557. 10.1038/gt.2008.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoshijima M.; Ikeda Y.; Iwanaga Y.; Minamisawa S.; Date M.-o.; Gu Y.; Iwatate M.; Li M.; Wang L.; Wilson J. M.; Wang Y.; Ross J.; Chien K. R. Chronic Suppression of Heart-Failure Progression by a Pseudophosphorylated Mutant of Phospholamban via in Vivo Cardiac RAAV Gene Delivery. Nat. Med. 2002, 8, 864–871. 10.1038/nm739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwanaga Y.; Hoshijima M.; Gu Y.; Iwatate M.; Dieterle T.; Ikeda Y.; Date M.-o.; Chrast J.; Matsuzaki M.; Peterson K. L.; Chien K. R.; Ross J. Chronic Phospholamban Inhibition Prevents Progressive Cardiac Dysfunction and Pathological Remodeling after Infarction in Rats. J. Clin. Invest. 2004, 113, 727–736. 10.1172/JCI18716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suckau L.; Fechner H.; Chemaly E.; Krohn S.; Hadri L.; Kockskämper J.; Westermann D.; Bisping E.; Ly H.; Wang X.; Kawase Y.; Chen J.; Liang L.; Sipo I.; Vetter R.; Weger S.; Kurreck J.; Erdmann V.; Tschope C.; Pieske B.; Lebeche D.; Schultheiss H.-P.; Hajjar R. J.; Poller W. C. Long-Term Cardiac-Targeted RNA Interference for the Treatment of Heart Failure Restores Cardiac Function and Reduces Pathological Hypertrophy. Circulation 2009, 119, 1241–1252. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.783852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Größl T.; Hammer E.; Bien-Möller S.; Geisler A.; Pinkert S.; Röger C.; Poller W.; Kurreck J.; Völker U.; Vetter R.; Fechner H. A Novel Artificial MicroRNA Expressing AAV Vector for Phospholamban Silencing in Cardiomyocytes Improves Ca2+ Uptake into the Sarcoplasmic Reticulum. PLoS One 2014, 9, e92188 10.1371/journal.pone.0092188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko M.; Yamamoto H.; Sakai H.; Kamada Y.; Tanaka T.; Fujiwara S.; Yamamoto S.; Takahagi H.; Igawa H.; Kasai S.; Noda M.; Inui M.; Nishimoto T. A Pyridone Derivative Activates SERCA2a by Attenuating the Inhibitory Effect of Phospholamban. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2017, 814, 1–8. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2017.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kho C.; Lee A.; Jeong D.; Oh J. G.; Gorski P. A.; Fish K.; Sanchez R.; Devita R. J.; Christensen G.; Dahl R.; Hajjar R. J. Small-Molecule Activation of SERCA2a SUMOylation for the Treatment of Heart Failure. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 7229. 10.1038/ncomms8229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Munari S.; Cerri A.; Gobbini M.; Almirante N.; Banfi L.; Carzana G.; Ferrari P.; Marazzi G.; Micheletti R.; Schiavone A.; Sputore S.; Torri M.; Zappavigna M. P.; Melloni P. Structure-Based Design and Synthesis of Novel Potent Na+,K +-ATPase Inhibitors Derived from a 5α,14α-Androstane Scaffold as Positive Inotropic Compounds. J. Med. Chem. 2003, 46, 3644–3654. 10.1021/jm030830y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Micheletti R.; Mattera G. G.; Rocchetti M.; Schiavone A.; Loi M. F.; Zaza A.; Gagnol R. J. P.; De Munari S.; Melloni P.; Carminati P.; Bianchi G.; Ferrari P. Pharmacological Profile of the Novel Inotropic Agent (E,Z)-3-((2-Aminoethoxy)Imino)Androstane-6,17-Dione Hydrochloride (PST2744). J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2002, 303, 592–600. 10.1124/jpet.102.038331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocchetti M.; Besana A.; Mostacciuolo G.; Micheletti R.; Ferrari P.; Sarkozi S.; Szegedi C.; Jona I.; Zaza A. Modulation of Sarcoplasmic Reticulum Function by Na+/K + Pump Inhibitors with Different Toxicity: Digoxin and PST2744 [(E,Z)-3-((2-Aminoethoxy)Imino)Androstane-6,17-Dione Hydrochloride]. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2005, 313, 207–215. 10.1124/jpet.104.077933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gheorghiade M.; Blair J. E. A.; Filippatos G. S.; Macarie C.; Ruzyllo W.; Korewicki J.; Bubenek-Turconi S. I.; Ceracchi M.; Bianchetti M.; Carminati P.; Kremastinos D.; Valentini G.; Sabbah H. N. Hemodynamic, Echocardiographic, and Neurohormonal Effects of Istaroxime, a Novel Intravenous Inotropic and Lusitropic Agent. A Randomized Controlled Trial in Patients Hospitalized With Heart Failure. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2008, 51, 2276–2285. 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alemanni M.; Rocchetti M.; Re D.; Zaza A. Role and Mechanism of Subcellular Ca2+ Distribution in the Action of Two Inotropic Agents with Different Toxicity. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2011, 50, 910–918. 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2011.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaza A.; Rocchetti M. Calcium Store Stability as an Antiarrhythmic Endpoint. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2014, 21, 1053–1061. 10.2174/1381612820666141029100650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arici M.; Ferrandi M.; Barassi P.; Hsu S.-C.; Torre E.; Luraghi A.; Ronchi C.; Chang G.-J.; Peri F.; Ferrari P.; Bianchi G.; Rocchetti M.; Zaza A.. Istaroxime metabolite PST3093 selectively stimulates SERCA2a and reverses disease-induced changes in cardiac function. 2022, bioRxiv:2021.08.17.455204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gobbini M.; Armaroli S.; Banfi L.; Benicchio A.; Carzana G.; Ferrari P.; Giacalone G.; Marazzi G.; Moro B.; Micheletti R.; Sputore S.; Torri M.; Zappavigna M. P.; Cerri A. Novel analogues of Istaroxime, a potent inhibitor of Na+,K+-ATPase: Synthesis, structure-activity relationship and 3D-quantitative structure-activity relationship of derivatives at position 6 on the androstane scaffold. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2010, 18, 4275–4299. 10.1016/J.BMC.2010.04.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrandi M.; Barassi P.; Tadini-Buoninsegni F.; Bartolommei G.; Molinari I.; Tripodi M. G.; Reina C.; Moncelli M. R.; Bianchi G.; Ferrari P. Istaroxime Stimulates SERCA2a and Accelerates Calcium Cycling in Heart Failure by Relieving Phospholamban Inhibition. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2013, 169, 1849–1861. 10.1111/bph.12278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torre E.; Arici M.; Lodrini A. M.; Ferrandi M.; Barassi P.; Hsu S.-C.; Chang G.-J.; Boz E.; Sala E.; Vagni S.; Altomare C.; Mostacciuolo G.; Bussadori C.; Ferrari P.; Bianchi G.; Rocchetti M. SERCA2a Stimulation by Istaroxime Improves Intracellular Ca2+ Handling and Diastolic Dysfunction in a Model of Diabetic Cardiomyopathy. Cardiovasc. Res. 2021, 118, 1020. 10.1093/cvr/cvab123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocchetti M.; Sala L.; Rizzetto R.; Staszewsky L. I.; Alemanni M.; Zambelli V.; Russo I.; Barile L.; Cornaghi L.; Altomare C.; Ronchi C.; Mostacciuolo G.; Lucchetti J.; Gobbi M.; Latini R.; Zaza A. Ranolazine Prevents INaL Enhancement and Blunts Myocardial Remodelling in a Model of Pulmonary Hypertension. Cardiovasc. Res. 2014, 104, 37–48. 10.1093/cvr/cvu188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocchetti M.; Besana A.; Mostacciuolo G.; Ferrari P.; Micheletti R.; Zaza A. Diverse Toxicity Associated with Cardiac Na+/K+ Pump Inhibition: Evaluation of Electrophysiological Mechanisms. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2003, 305, 765–771. 10.1124/jpet.102.047696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.