Abstract

Background

Shuang Huang Lian (SHL) is a traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) formula made from Lonicerae Japonicae Flos, Forsythiae Fructus, and Scutellariae Radix. Despite the widespread use of SHL in clinical practice for treating upper respiratory tract infections (URTIs), the complete component fingerprint and the pharmacologically active components in the SHL formula remain unclear. The objective of this study was to develop an untargeted metabolomics method for component identification, quantitation, pattern recognition, and cross-comparison of various SHL preparation forms (i.e., granule, oral liquid, and tablet).

Methods

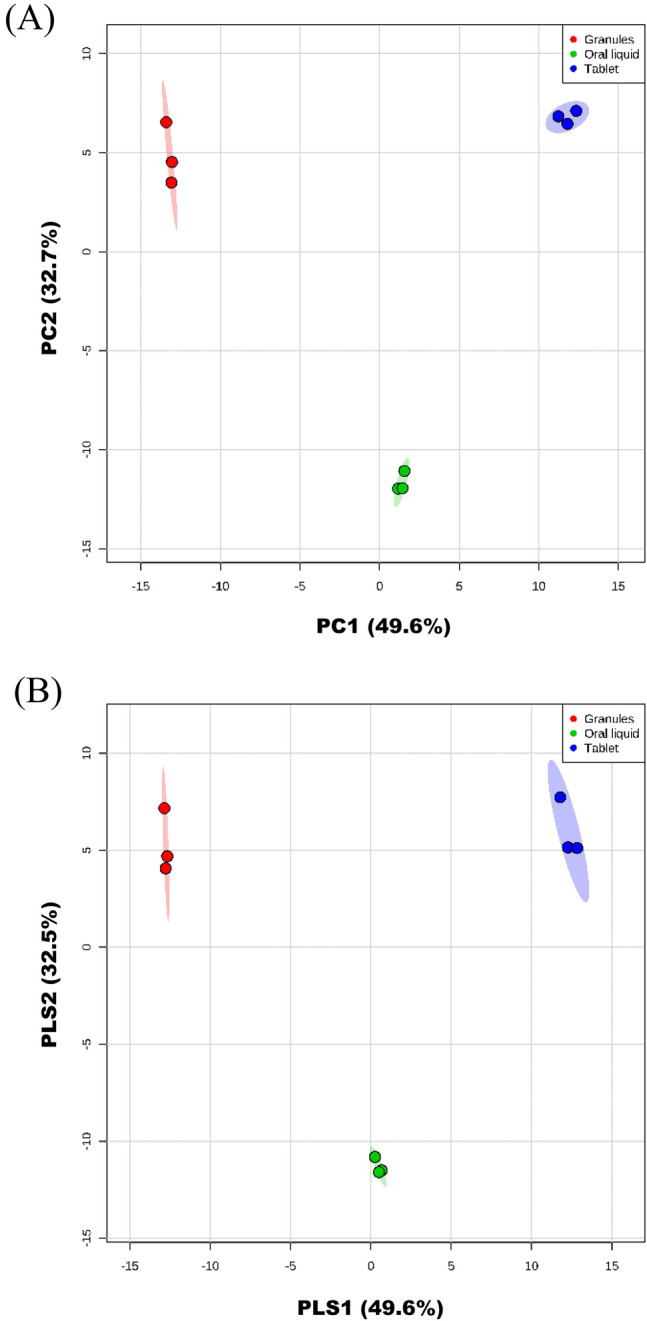

Ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography and quadrupole time-of-flight tandem mass spectrometry (UHPLC-QTOF-MS/MS) together with bioinformatics were used for chemical profiling, identification, and quantitation of SHL. Multivariate data analyses such as principal component analysis (PCA) and partial least squares discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) were performed to assess the correlations among the three SHL preparation forms and the reproducibility of the technical and biological replicates.

Results

A UHPLC-QTOF-MS/MS-based untargeted metabolomics method was developed and applied to analyze three SHL preparation forms, consisting of 178 to 216 molecular features. Among the 95 common molecular features from the three SHL preparation forms, quantitative analysis was performed using a single exogenous reference internal standard. Forty-seven of the 95 common molecular features have been identified using various databases. Among the 47 common components, there were 17 flavonoids, 7 oligopeptides, 5 terpenoids, 2 glycosides, 2 cyclohexanecarboxylic acids, 2 spiro compounds, 2 lipids, 2 glycosylglycerol derivatives, and 8 various compounds such as alkyl caffeate ester, aromatic ketone, benzaldehyde, benzodioxole, benzofuran, chalcone, hydroxycoumarin, and purine nucleoside. Five of the 47 common components were designated by the Chinese Pharmacopoeia as the quality markers of medicinal plants of SHL, and 15 were previously reported to have pharmacological activities. Distinct patterns of the three SHL preparation forms were observed in the PCA and PLS-DA plots.

Conclusions

The developed method is reliable and reproducible, which is useful for the profiling, component identification, quantitation, quality assessment of various SHL preparation forms and may apply to the analysis of other TCM formulas.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13020-022-00610-x.

Keywords: Shuang Huang Lian, Metabolomics analyses, UHPLC-QTOF-MS/MS, Traditional Chinese medicine formula, Upper respiratory tract infections

Background

Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) has been used to prevent and treat various diseases for over 2500 years. Shuang Huang Lian (SHL) is a modern TCM formula that has been widely used in Asian countries as a remedy for fever, cough, sore throat, and upper respiratory tract infections (URTIs) [1–4]. SHL inhibits the respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), para-influenza I–IV, and 23 kinds of pathogenic bacteria such as Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, etc. in vitro cell culture studies [5–8]. Moreover, SHL had been recommended by the Chinese Guidelines for Diagnosis and Treatment of Influenza (2011) for the treatment of influenza [9]. Currently, SHL is widely used in clinical practice to treat various respiratory diseases, including acute URTIs [3, 4, 9, 10].

SHL is comprised of the alcohol–water extracts of Lonicerae Japonicae Flos (the dried buds of Lonicera japonica Thunb.), Forsythiae Fructus [the dried fruits of Forsythia suspense (Thunb.) Vahl], and Scutellariae Radix (the dried roots of Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi.) with a ratio of 1:2:1 [11–13]. Nowadays, various preparation forms of SHL are made and commercially available, such as granules, tablets, oral liquid, powder for injection, etc. [13]. Although the widespread use of SHL by practitioners of complementary and alternative medicine and its efficacy for treating URTIs, the pharmacologically active components and the molecular mechanisms of SHL remain unclear. Therefore, it is necessary to explore the pharmacologically active components of SHL first, then to uncover the molecular mechanisms in support of evidence-based medicine. In this work, we intend to address the first task.

The analytical methods currently available for SHL, including CE, LC-PDA, LC-ECD, and LC–MS, have mainly targeted analyses for quantitation of a few marker components that may not even be the bioactive components of the herbal medicine formula [1, 11, 14–18]. Although there were a few reports on the determination of multi-components in either SHL powder for injection or oral liquid using high-resolution LC–MS [2, 9, 12, 19, 20], the study of chemical components of SHL is still limited. There is neither a complete component fingerprint of the SHL formula nor a comparative analysis on various SHL preparation forms.

SHL is a mixture of three herbal extracts containing hundreds of compounds, and these compounds can further react with each other to form new compounds. In this work, we have developed an untargeted metabolomics workflow for profiling, component identification, semi-quantitation, pattern recognition, and cross-comparison of various SHL preparation forms (i.e., granule, oral liquid, and tablet), which is based on the uses of ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography and quadrupole time-of-flight tandem mass spectrometry (UHPLC-QTOF-MS/MS) for data acquisition and bioinformatics for data analysis. We have also performed both database search and literature mining to retrieve the antiviral, antibacterial, and other pharmacologically active components of the SHL formula, which can be used for the network pharmacology study to unravel the molecular mechanisms of the SHL formula and discover lead compounds for new therapeutic agents [21, 22].

Materials and methods

Chemicals and reagents

Ammonium hydroxide and formic acid were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Acetonitrile and methanol (Optima™ LC/MS grade) were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Bridgewater, NJ, USA). Deionized water was obtained from an in-house Barnstead Nanopure® water purification system (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) with a resistivity meter reading of 18.2 MΩ-cm. Etoposide-d3 used as the internal standard (IS) was purchased from Toronto Research Chemicals (Toronto, Ontario, Canada).

Shuang Huang Lian tablets (Batch number: 1406003) were purchased from Harbin Sanctity Biological Pharmaceutical (Harbin, Heilongjiang, China). Shuang Huang Lian granule (Batch number: 151230) was purchased from Harbin Children Pharmaceutical Factory (Harbin, Heilongjiang, China). Shuang Huang Lian oral liquid (Batch number: 15065022) was purchased from Henan Fusen Pharmaceutical (Nanyang, Henan, China).

Preparation of internal standard, SHL, and QC samples

The stock solution of etoposide-d3 (IS) was prepared by dissolving 1.00 mg powder in 1.00 mL of methanol to a 1.00 mg/mL concentration. The working solution of IS was prepared by a 1/10 dilution of the stock solution in methanol to a concentration of 0.100 mg/mL (169 µM).

Two Shuang Huang Lian tablets (0.530 g/tablet), one package of Shuang Huang Lian granules (5.00 g/package), and 10.0 mL Shuang Huang Lian oral liquid lyophilized using a Freezone 4.5 L Freeze Dry System (Labconco, Kansas City, MO, USA), which were all equivalent to 15.0 g raw herbal pieces according to the manufacturers’ instructions, were transferred to three identical 50.0 mL volumetric flasks (SIBATA Scientific Technology, Kaohsiung, Taiwan), then, 20.0 mL deionized water was added to soak for 60 min. After soaking, 20.0 mL deionized water was added. After being mixed by swirling, the solution was sonicated for 30.0 min using an FS30 Ultrasonic Cleaner (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburg, PA, USA) at 55 °C. Deionized water was added to the mark of the flask and mixed by inverting after the solution cooled down to room temperature. The solution in each flask was allowed to settle for 30.0 min before use. Then, 3.00 mL supernatant was transferred to a borosilicate glass test tube (16 × 100 mm) (Fisher Scientific, Hanover Park, IL, USA) followed by the addition of 6.90 mL methanol and 0.100 mL IS working solution. After vortexing for 30 s using a MaxiMix I Vortex Mixer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), 1.00 mL of solution was transferred to a 1.50 mL microcentrifuge tube (VWR, Radnor, PA, USA), which was centrifuged at 18,000×g for 10 min at 4 °C using a Sorvall ST 40R centrifuge (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The supernatant (600 µL) was then transferred to a 1.80-mL LC glass vial (ThermoFisher Scientific, West Palm Beach, FL, USA) and subjected to the UHPLC-MS/MS analysis.

QC samples (600 µL) could be prepared by mixing 200 µL of each of the three SHL sample solutions and used with each batch analysis by monitoring the selectivity and reproducibility of the 47 commonly identified compounds throughout the analysis.

Assessment of sample matrix effects

The matrix effects were assessed in terms of absolute matrix factors (MFs) for each SHL preparation form at both positive and negative ionization mode by spiking the IS into the sample solution. The MFs of the IS were determined by the mean peak area of the IS spiked at a fixed concentration (1.69 µM) in an extracted sample matrix over that of the IS spiked at the concentration in a blank solution (70% methanol) in each ionization mode.

Method validation

The selectivity and reproducibility of the UHPLC-QTOF-MS/MS method were assessed by replicate measurements of three SHL preparation forms. PCA and PLS-DA score plots were constructed to visualize the closeness of the replicate measurements of each SHL preparation form and the differences among the three SHL preparation forms. The intra-day coefficient variation (CV) was determined by the concentrations of triplicate measurements of the 47 commonly identified compounds in the same sample within the same day, whereas the inter-day CV was determined by the concentrations of three parallel measurements of the 47 commonly identified compounds in three identical samples in 3 separate days.

UHPLC-QTOF-MS/MS system

The UHPLC-QTOF-MS/MS system used in this work consisted of Agilent 1290 Infinity UHPLC modules (Agilent Corp., Santa Clara, CA, USA) coupled with Agilent 6540 QTOF Mass Spectrometer (Agilent Corp., Santa Clara, CA, USA). The UHPLC modules included a solvent reservoir, a degasser, a G4220A binary pump, a G1330B thermostat, a G4226A autosampler, a G1316C thermostatted column compartment, and a G4212A diode-array detector. The mass spectrometer was equipped with an Agilent Jet Stream electrospray ionization (AJS-ESI) probe. The UHPLC column outlet was connected to the mass spectrometer using polyether ether ketone (PEEK) tubing (0.0625 in. o.d. × 0.00500 in. i.d.).

Liquid chromatographic separation was achieved using gradient elution on a Waters ACQUITY UPLC® BEH C18 (2.1 mm i.d. × 100 mm, 1.7 µm, 130 Å) column (Waters, Milford, MA, USA) with an inline VHP filter (0.5 µm, stainless steel) from Upchurch Scientific (Oak Harbor, WA, USA). This column had a pressure tolerance of 18,000 psi, a pH range of 1–12, and a temperature range of 20–90 °C. The mobile phase used for the positive electrospray ionization (ESI+) mode acquisition was composed of (A) 0.1% formic acid aqueous solution and (B) 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile. The mobile phase used for the negative electrospray ionization (ESI−) mode acquisition was composed of (A) 0.1% ammonium hydroxide aqueous solution and (B) 0.1% ammonium hydroxide in acetonitrile. The gradient elution profile was as follows: 0–4 min, 5% B; 4–7 min, 5–10% B; 7–20 min, 10–15% B; 20–30 min, 15–22% B; 30–35 min, 22–35% B; 35–40 min, 35–50% B; 40–45 min, 50–70% B; 45–50 min, 70–90% B; 50–52 min, 5% B; 52–60 min, 5% B. The flow rate was at 0.200 mL/min. The column temperature was at 60 °C. The sample injection volume was 5.00 μL. Before sample analysis, the column was equilibrated with a mobile phase at the initial gradient for 1 h at a flow rate of 0.200 mL/min.

The Agilent 6540 QTOF Mass Spectrometer was operated at both positive and negative ESI modes. The LC–MS/MS data were acquired using Agilent MassHunter Data Acquisition software (Version: B.05.01) with auto MS/MS acquisition mode. The operation conditions of the AJS-ESI source were as follows: drying gas (N2) temperature, 350 °C; drying gas flow rate, 10.0 L/min; nebulizer gas (N2) pressure, 35 psi; sheath gas (N2) temperature, 325 °C; sheath gas flow rate, 11.0 L/min; capillary voltage, 4000 V; nozzle voltage, 500 V; fragmentor voltage, 100 V; skimmer voltage, 65 V; octopole radio-frequency voltage (OCT RF V), 750 V. The collision energies (CE) were set at 10, 20, and 40 eV. The MS scan range was from 50 to 1800 m/z with a scan rate of 5 spectra/s. The MS/MS scan range was from 50 to 1800 m/z with a scan rate of 4 spectra/s. To maintain the mass accuracy, the mass spectrometer was tuned using the Agilent tuning mix solution before analysis, and the reference mass solution was used for real-time mass correction and validation at m/z 121.0509 and m/z 922.0098 for the positive ion mode, and m/z 112.9856 and m/z 1033.9881 for the negative ionization mode, throughout the data acquisition process (Additional file 1: Appendix S1).

Data processing and component identification

Data acquired from the samples of three SHL preparation forms at either positive or negative ionization mode by Agilent MassHunter Data Acquisition software were saved as (.d) files; then evaluated with Agilent MassHunter Qualitative Analysis software (Version: B.06.00) for peak shape, signal to noise ratio, retention time and mass shifts (vs. the spiked IS). The (.d) files were further processed by Agilent MassHunter Profinder software (Version: B.06.00) for batch recursive analysis. The data files were grouped by positive and negative ion modes in three preparation forms. The molecular features were extracted with a peak height threshold of 1,000 counts, possible ion adducts [M+H]+, [M+Na]+, [M+NH4]+ for positive ion mode and [M−H]− for negative ion mode, isotope model of common organic molecules, charge state up to two, a retention time window of 0.10% + 0.60 min, and a mass window of 20.00 ppm + 2.00 mDa for the alignment of the IS in each data group with the same polarity. The post-processing filter was set at 3 out of 3 replicate measurements for each SHL preparation form at the same polarity. The molecular feature extraction and find-by-ion data files using the Agilent MassHunter Profinder software were exported as compound exchange files (.cefs).

Each (.cef) file exported from the Agilent MassHunter Profinder software and its corresponding (.d) file were imported to the Agilent MassHunter Qualitative Analysis software to extract MS/MS data along with its MS data using the “Find by Formula” function under “Method Explorer”. The extracted data file for each sample run was then exported as a new (.cef) file for further data processing. All new (.cef) files of replicates measurements of each SHL preparation form at the same polarity exported from Agilent MassHunter Qualitative Analysis software were imported to Agilent Mass Profiler Professional (MPP) software (Version: B.13.1.1) for molecular formula generation and compound identification using the “ID Browser” function to search the Agilent METLIN AM database. To generate molecular formulas with the extracted molecular features, the selection and cut-off limit of elements were as follows: carbon (3–156); hydrogen (0–180); oxygen (0–40); nitrogen (0–20); sulfur (0–14); chlorine (0–12); fluorine (0–48); bromine (0–10); phosphorus (0–9); and silicon (0–15) [23]. The top 5 identified compounds with the highest scores for each molecular formula were cross-checked with the Traditional Chinese Medicine Integrated Database (TCMID) [24] and the Traditional Chinese Medicine Systems Pharmacology (TCMSP) Database and Analysis Platform before the final annotation [25, 26]. For the analysis of fragmentation pathways of MS/MS spectra, Agilent MassHunter Molecular Structure Correlator (MSC) (Version: 8.1) was first used to correlate the accurate mass MS/MS fragment ions for precursor ions in forms of proton adducts, and the unresolved fragmentation patterns were analyzed by an open-source software SIRIUS + CSI:FingerID GUI (Version 4.9.12) [27].

Statistical analysis and pattern recognition

Principal component analysis (PCA) and partial least squares discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) were performed on the MetaboAnalyst 4.0 online platform [28, 29]. In detail, the (.csv) files of replicate measurements of each SHL preparation form at the same polarity were exported from the Agilent MassHunter Profinder, which carried the data of mass, retention time, and peak area. The (.csv) files of MS peak list data were then combined as one (.zip) file and uploaded to the MetaboAnalyst platform. A mass tolerance of 0.025 Da and a retention time tolerance of 30.0 s were chosen for compound alignment. The data were filtered with the “Interquartile Range (IQR)” model to identify and remove variables from baseline noises and improve the accuracy of the results. Data normalization was performed using the IS reference feature (i.e., mass, retention time, and peak area). All data were log-transformed and auto-scaled. The 2D PCA and PLS-DA score plots were constructed. For PLS-DA, the variable importance in projection (VIP) scores were calculated as a weighted sum of the squared correlation between the PLS-DA components and the original variable, summarizing each variable's contribution and influence to this model [30, 31].

Global semiquantitative analysis

Global semiquantitative analysis was carried out using the (.d) files with the same polarity of the replicate measurements of each SHL preparation form obtained by the Agilent MassHunter Acquisition software and the corresponding combined data files (.cef) with the identities obtained by the Agilent MPP software. The (.d) and (.cef) files were imported into Agilent MassHunter Quantitative Analysis software (Version: B.06.00). The retention time window was set at 0.6 min in the method setup task. The m/z of IS adducts, [IS+NH4]+ and [M−H]−, were chosen for the positive and negative ionization modes and flagged. Other chemical components were set as targets relative to the IS, and the ionization polarities were identified. After validating the method setup, global semiquantitative analysis was performed based on the peak area ratio of each target to the IS. The results were exported as an Excel file for reporting.

Results and discussion

Optimization of the UHPLC-QTOF-MS/MS method

The choices of mobile-phase pair for gradient elution and column for separation were investigated. The data (not shown) indicated that the acetonitrile–water pair had lower back pressure and gave better analyte resolution than those of the methanol–water pair on C18 columns. Therefore, the acetonitrile–water pair was selected as the mobile-phase pair for the method. In addition, 0.1% formic acid or 0.1% ammonium hydroxide was added to the mobile phase pair to facilitate the protonation or deprotonation of the analytes for mass spectrometric detection of the analytes in positive or negative ionization mode. It was also found that the Waters ACQUITY UPLC® BEH C18 column (2.1 mm i.d. × 100 mm, 1.7 µM, 130 Å) gave greater separation efficiency, larger signal-to-noise ratio, and better peak shape than those of the Agilent ZORBAX Extend-C18 Rapid Resolution HT column (2.1 mm i.d. × 50 mm, 1.8 µM, 80 Å); therefore, the former was adopted for the method.

Both positive and negative ionization modes were applied to the analyses of SHL samples using QTOF-MS/MS, and comprehensive information about the SHL components was obtained. The fragmentor voltage that plays a vital role in generating fragments in the auto MS/MS acquisition mode was examined using three voltage settings of 100 V, 120 V, and 150 V. The voltage of 100 V that generated fragments matched the literature reports [9] and therefore adopted for the method. The collision energy was set at 10, 20, and 40 eV to correspond with those of the MS and MS/MS spectra in the METLIN AM database.

Internal standard and matrix effects of various SHL preparation forms

An exogenous stable isotope-labeled compound, etoposide-d3, was chosen as the IS for multiple purposes in this work, including corrections of retention time and mass shifts in the analysis of mass chromatographic data, assessment of sample matrix effect, peak normalization in multivariate data analysis, global semi-quantitative analysis, and cross-comparison of the common multi-components in various SHL preparation forms. Etoposide is a synthetic compound, and its stable isotope etoposide-d3 does not occur as an endogenous compound in plant products. The use of etoposide-d3 as the IS eliminated the potential interference from endogenous compounds in sample matrices.

Our experimental data (not shown) indicated no chromatographic and mass spectrometric interferences on the IS detection from the solution blanks and the samples of the three SHL preparation forms. The matrix effects of the SHL samples on the mass spectrometric detection of the IS were quantified by MFs. As shown in Table 1, the MFs were 0.91–0.93, 0.95–0.97, and 0.89–0.93, respectively, for the SHL granule, oral liquid, and tablet preparation forms by mass spectrometric detections in both positive and negative ionization modes. These MF values were close to 1.0, indicating no significant signal suppression on the detection of the IS by the sample matrices.

Table 1.

Matrix effects of SHL samples on mass spectrometric detection of the IS

| SHL sample | ESI mode | PAISa in extracted sample matrix ± SDb | PAIS in solution ± SD | MFISc ± SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Granules | + | (6.95 ± 0.05) × 105 | (7.6 ± 0.2) × 105 | 0.91 ± 0.02 |

| − | (2.05 ± 0.08) × 106 | (2.2 ± 0.1) × 106 | 0.93 ± 0.06 | |

| Oral liquid | + | (7.4 ± 0.2) × 105 | (7.6 ± 0.2) × 105 | 0.97 ± 0.04 |

| − | (2.09 ± 0.02) × 106 | (2.2 ± 0.1) × 106 | 0.95 ± 0.04 | |

| Tablet | + | (7.1 ± 0.1) × 105 | (7.6 ± 0.2) × 105 | 0.93 ± 0.03 |

| − | (1.96 ± 0.05) × 106 | (2.2 ± 0.1) × 106 | 0.89 ± 0.05 |

[IS] = 1.69 µM

aPAIS = mean peak area of the spiked IS

bSD = standard deviation

cMFIS = (PAIS in the extracted sample matrix)/(PAIS in the solution)

Untargeted and targeted metabolomics analyses of SHL formula

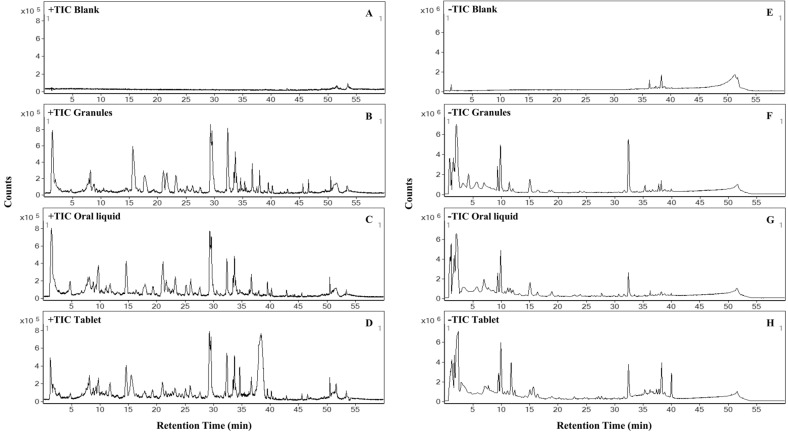

For untargeted metabolomics analysis of various SHL preparation forms, triplicate samples were prepared for each SHL preparation form (i.e., granule, oral liquid, and tablet) and the solution blank (i.e., 70% methanol). A total of twelve samples were analyzed using the UHPLC-QTOF-MS/MS method. The mass chromatograms with MS and MS/MS data were acquired from the twelve samples by both positive and negative ESI modes. The representative total-ion-current (TIC) chromatograms were shown in Fig. 1. Using the chromatographic and mass spectrometric data obtained from the untargeted metabolomics profiling, we achieved component identification, global semi-quantitative analysis, and cross-comparison of common components among various SHL preparation forms, as well as multivariate analysis.

Fig. 1.

The representative total-ion chromatograms (TICs) of the solution blank and the samples of the three SHL preparation forms by both positive ionization mode (A–D) and negative ionization mode (E–H)

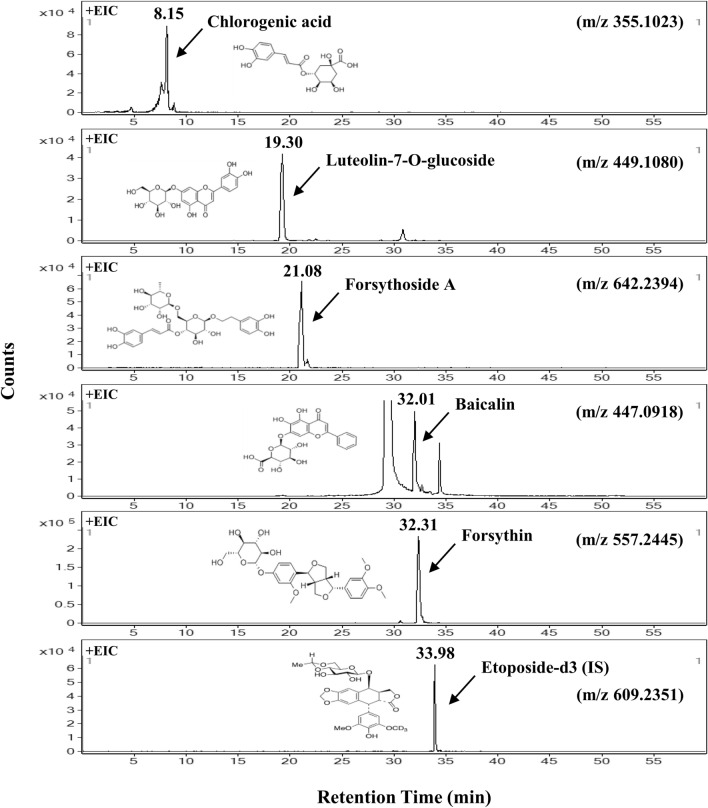

Targeted metabolomics analysis of the SHL formula was illustrated by the extracted ion chromatograms (EICs) (Fig. 2). As per the Chinese Pharmacopoeia [13], there are five non-volatile, water-soluble quality markers (Q-markers) in the herbs of SHL formula (i.e., chlorogenic acid, luteolin-7-O-glucoside, forsythoside A, baicalin, and forsythin). As shown in Fig. 2, these Q-markers could be easily targeted and extracted simultaneously by the UHPLC-MS/MS method developed. They can be used for quality assessment and detection of counterfeited SHL products.

Fig. 2.

The representative extracted-ion chromatograms (EICs) of five Q markers of SHL formula and the IS at a concentration of 1.69 µM

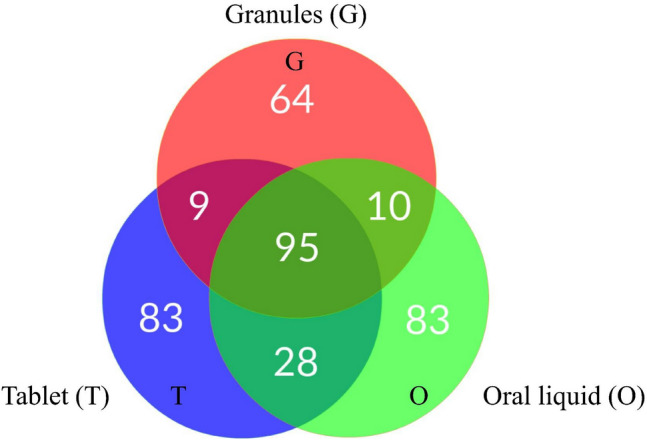

Identification of components in three SHL preparation forms

Identification of chemical components in each SHL preparation form was performed per the procedures described in “Materials and methods” section. The list of components in each SHL preparation form was obtained after subtracting the background components in the solution blanks (Additional file 4: Table S1, Additional file 5: Table S2, Additional file 6: Table S3, Additional file 7: Table S4, Additional file 8: Table S5 and Additional file 9: Table S6). The numbers of components identified with both chemical names and formulas and the components unidentified but with formulas in each SHL preparation form were given in Additional file 10: Table S7. As seen in Additional file 10: Table S7, the total chemical components found in three SHL preparation forms were 178, 216, and 215 for granule, oral liquid, and tablet, respectively. Among the 95 components commonly found in the three preparation forms (Fig. 3), 47 of them were identified with both chemical names and formulas (Table 2), and the other 48 were unidentified (or identified only with formulas) (Additional file 11: Table S8). Among the 47 common components, there were 17 flavonoids, 7 oligopeptides, 5 terpenoids, 2 glycosides, 2 cyclohexanecarboxylic acids, 2 spiro compounds, 2 lipids, 2 glycosylglycerol derivatives, and 8 various compounds such as alkyl caffeate ester, aromatic ketone, benzaldehyde, benzodioxole, benzofuran, chalcone, hydroxycoumarin, and purine nucleoside. The mass spectra of the 47 commonly identified components were shown in Additional file 2: Fig. S1. The fragmentation pathways of the commonly identified compounds (Additional file 3: Fig. S2) were proposed using Agilent MSC software via a systematic bond-breaking approach [32] which was applied to most of the precursor ions as proton adducts, and the unresolved fragmentation patterns were analyzed using SIRIUS + CSI:FingerID GUI by the combined analysis of isotope patterns in MS spectra and fragmentation patterns in MS/MS spectra together with the web search in molecular structure databases on CSI:FingerID [33, 34].

Fig. 3.

The Venn diagram of the components found in each SHL preparation form

Table 2.

The common chemical components identified with names and formulas in all three SHL preparation forms

| No | Formula | Name | tR (min) | Observed mass | Database mass | Precursor ion, m/z | MS/MS quantifier, m/z | MS/MS qualifier, m/z |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | C21H20O13 | Tagetiin | 1.71 | 480.0895 | 480.0916 | 479.0815, [M−H]− | 315.0344 | 139.0030 |

| 2 | C28H16O5 | Naphthofluorescein | 4.61 | 432.1022 | 432.1031 | 431.0940, [M−H]− | 268.0365 | 239.0332 |

| 3 | C21H26N4O8 | Trp-Glu-Glu | 7.88 | 462.1731 | 462.1751 | 485.1633, [M+Na]+ | 339.1063 | 213.0327 |

| 4 | C9H6O3 | Umbelliferone | 8.15 | 162.0316 | 162.0316 | 163.0388, [M+H]+ | 63.0232 | 89.0393 |

| 5 | C16H18O9 | Chlorogenic acida | 8.15 | 354.0950 | 354.0951 | 355.1023, [M+H]+ | 89.0391 | 163.0388 |

| 6 | C10H10O4 | Methyl caffeate | 9.75 | 194.0579 | 194.0582 | 195.0652, [M+H]+ | 77.0387 | 95.0491 |

| 7 | C10H12O5 | Danielone | 9.75 | 212.0683 | 212.0682 | 213.0755, [M+H]+ | 107.0491 | 151.0391 |

| 8 | C8H6O3 | Piperonal | 9.76 | 150.0318 | 150.0319 | 151.0391, [M+H]+ | 51.0228 | 77.0383 |

| 9 | C16H22O10 | Geniposidic acid | 9.76 | 374.1211 | 374.1213 | 397.1106, [M+Na]+ | 235.0573 | 255.0855 |

| 10 | C16H18O8 | p-Coumaroyl quinic acid | 10.48 | 338.1003 | 338.1002 | 339.1078, [M+H]+ | 91.0544 | 147.0435 |

| 11 | C16H22O9 | Tarennoside | 11.72 | 358.1264 | 358.1264 | 359.1337, [M+H]+ | 197.0811 | 127.0390 |

| 12 | C15H26N6O6 | Asp-Arg-Pro | 11.72 | 386.1912 | 386.1916 | 385.1831, [M−H]− | 153.0919 | 59.0145 |

| 13 | C16H28N6O8 | Arg-Glu-Glu | 11.72 | 432.1969 | 432.1960 | 431.1894, [M−H]− | 269.0449 | 387.0756 |

| 14 | C10H12O4 | Paeonilactone B | 11.78 | 196.0736 | 196.0732 | 197.0808, [M+H]+ | 127.0386 | 53.0386 |

| 15 | C20H27N5O6 | Thr-Gln-Trp | 15.15 | 433.1945 | 433.1943 | 434.2017, [M+H]+ | 85.0283 | 145.0490 |

| 16 | C20H24N4O6 | Pro-Trp-Asp | 15.15 | 416.1680 | 416.1696 | 434.2017, [M+NH4]+ | 295.1026 | 285.1343 |

| 17 | C15H21N5O8 | Asp-Glu-His | 16.34 | 399.1396 | 399.1390 | 417.1734, [M+NH4]+ | 285.1301 | 85.0284 |

| 18 | C16H18N6O4 | 2-Phenylaminoadenosine | 16.50 | 358.1394 | 358.1387 | 357.1315, [M−H]− | 151.0398 | 136.0177 |

| 19 | C27H30O16 | Rutin | 17.73 | 610.1536 | 610.1537 | 611.1611, [M+H]+ | 303.0497 | 465.1027 |

| 20 | C21H18O12 | Luteolin 3′-glucuronide | 18.13 | 462.0814 | 462.0797 | 463.0872, [M+H]+ | 287.0550 | 123.0080 |

| 21 | C21H20O11 | Luteolin-7-O-glucosidea | 19.30 | 448.1007 | 448.1006 | 449.1080, [M+H]+ | 287.0548 | 153.0178 |

| 22 | C21H26O12 | Plumieride | 21.08 | 470.1424 | 470.1423 | 471.1499, [M+H]+ | 163.0387 | 325.0912 |

| 23 | C29H36O15 | Forsythoside Aa | 21.08 | 624.2046 | 624.2054 | 642.2394, [M+NH4]+ | 471.1486 | 163.0385 |

| 24 | C13H28N6O8 | Zwittermicin A | 22.64 | 396.1975 | 396.1979 | 395.1906, [M−H]− | 263.1487 | 101.0251 |

| 25 | C20H20O5 | Morachalcone A | 23.24 | 340.1309 | 340.1313 | 341.1384, [M+H]+ | 137.0592 | 291.1008 |

| 26 | C26H32O11 | Brusatol | 23.24 | 520.1943 | 520.1945 | 538.2284, [M+NH4]+ | 235.0961 | 175.0754 |

| 27 | C27H30O14 | Isofurcatain 7-O-glucoside | 25.01 | 578.1637 | 578.1637 | 579.1708, [M+H]+ | 271.0600 | 433.1131 |

| 28 | C25H24O12 | Apigenin 7-(3″,4″-diacetylglucoside) | 25.96 | 516.1268 | 516.1269 | 517.1342, [M+H]+ | 163.0394 | 337.0914 |

| 29 | C21H20O10 | Isovitexin | 29.87 | 432.1059 | 432.1058 | 433.1135, [M+H]+ | 271.0608 | 123.0080 |

| 30 | C27H34O11 | Undulatone | 30.67 | 534.2073 | 534.2065 | 533.2000, [M−H]− | 371.1487 | 356.1261 |

| 31 | C21H18O11 | Baicalina | 32.01 | 446.0846 | 446.0849 | 447.0918, [M+H]+ | 271.0602 | 123.0079 |

| 32 | C27H34O11 | Forsythina | 32.31 | 534.2097 | 534.2101 | 552.2445, [M+NH4]+ | 355.1527 | 189.0910 |

| 33 | C22H20O12 | Hispidulin 7-glucuronide | 33.08 | 476.0957 | 476.0957 | 477.1030, [M+H]+ | 301.0706 | 286.0474 |

| 34 | C21H18O10 | Chrysin 7-glucuronide | 33.44 | 430.0901 | 430.0902 | 431.0974, [M+H]+ | 255.0660 | 153.0179 |

| 35 | C22H20O11 | Wogonin 7-glucuronide | 33.69 | 460.1007 | 460.1008 | 461.1080, [M+H]+ | 285.0756 | 270.0522 |

| 36 | C21H18O11 | Apigenin 7-glucuronide | 34.37 | 446.0845 | 446.0845 | 447.0918, [M+H]+ | 271.0597 | 73.0286 |

| 37 | C16H12O6 | Kaempferide | 36.46 | 300.0638 | 300.0629 | 301.0710, [M+H]+ | 286.0462 | 184.0002 |

| 38 | C15H10O5 | Baicalein | 36.68 | 270.0531 | 270.0530 | 271.0604, [M+H]+ | 123.0085 | 68.9975 |

| 39 | C21H24O6 | Kadsurin A | 37.82 | 372.1575 | 372.1573 | 390.1916, [M+NH4]+ | 137.0600 | 355.1549 |

| 40 | C16H12O5 | Wogonin | 39.51 | 284.0686 | 284.0674 | 285.0758, [M+H]+ | 270.0536 | 77.0387 |

| 41 | C17H14O6 | 5,3′-Dihydroxy-7,4′-dimethoxy-4-phenylcoumarin | 39.88 | 314.0791 | 314.0792 | 315.0863, [M+H]+ | 71.0129 | 285.0407 |

| 42 | C19H18O8 | Skullcapflavone II | 40.19 | 374.1001 | 374.0999 | 375.1075, [M+H]+ | 345.0596 | 197.0086 |

| 43 | C15H22O2 | Eremophilenolide | 45.47 | 234.1622 | 234.1623 | 235.1696, [M+H]+ | 57.0704 | 180.1141 |

| 44 | C24H50NO7P | PE (19:0/0:0) | 46.58 | 495.3325 | 495.3329 | 496.3399, [M+H]+ | 184.0732 | 104.1073 |

| 45 | C19H38O4 | 1-Monopalmitin | 50.89 | 330.2774 | 330.2769 | 331.2846, [M+H]+ | 67.0538 | 57.0694 |

| 46 | C51H84O15 | 1,2-Di-(9Z,12Z,15Z-octadecatrienoyl)-3-(galactosyl-alpha-1-6-galactosyl-beta-1)-glycerol | 51.06 | 936.5809 | 936.5810 | 954.6148, [M+NH4]+ | 614.4875 | 335.2578 |

| 47 | C45H74O10 | 1,2-Di-(9Z,12Z,15Z-octadecatrienoyl)-3-O-Beta-d-galactosyl-sn-glycerol | 51.30 | 774.5282 | 774.5282 | 792.5616, [M+NH4]+ | 614.4787 | 336.2604 |

aQ markers

A comparison of the components identified in SHL oral liquid done in the current work with the Agilent METLIN AM database and a reported one done with an in-house library [9] showed that there were 216 components detected by the present work (Additional file 6: Table S3 and Additional file 7: Table S4) whereas 170 components seen in the reported one [9]. Between the two-component sets, there were 27 identical formulas, 11 annotated with the same names (i.e., baicalein, baicalin, chlorogenic acid, chrysin 7-glucuronide, forsythin, forsythoside A, luteolin-7-O-glucoside, rutin, skullcapflavone II, wogonin, and wogonin 7-glucuronide), and 16 annotated with different names. One possible explanation for the discrepancy between the two-component sets might be the databases (commercial vs. in-house) and the different MS/MS spectra matching criteria used. Nevertheless, the component sets identified in the current and previous work provided valuable information for the quality control and further investigation of the SHL formula. For unequivocal identification of components in the SHL formula, component isolation and comparison with authentic standards by additional analytical work are needed.

Global semi-quantitative analysis and cross-comparison among the three preparation forms

Global semi-quantitative analysis was performed on the 47 common components identified in the three SHL preparation forms using the UHPLC-QTOF-MS/MS method developed with an exogenous stable isotope-labeled IS (etoposide-d3). The concentrations detected (µM) were back-calculated to the amounts (µg) that were equivalent to 15.0-g raw herbal pieces, and the reproducibilities of the UHPLC-QTOF-MS/MS method were assessed by the coefficient of variation (CV) (Table 3). As shown in Table 3, the amounts of the 47 common components identified in the three SHL preparation forms were obtained, which could be cross-compared among the three preparation forms. If a CV ≤ 15% was adopted, the least acceptable coverages for the 47 common components in three SHL preparation forms were 87% for intra-day assay and 89% for inter-day assay, respectively, which were better than the recommended values (at least 70% at CV ≤ 15%) [35], indicating thtablee good reproducibility of the analytical method. To make this approach practical for accurate quantitative assessment of multi-components in SHL, conversion factors of the detector responses between each analyte and the IS should be calculated.

Table 3.

Global semi-quantitative analysis of the 47 common components identified in three SHL preparation forms

| No | Formula | Name | Intra-day (n = 3) | Inter-day (n = 3) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G ± SD (CV%) (µgb) | O ± SD (CV%) (µgb) | T ± SD (CV%) (µgb) | G ± SD (CV%) (µgb) | O ± SD (CV%) (µgb) | T ± SD (CV%) (µgb) | |||

| 1 | C21H20O13 | Tagetiin | 44 ± 8 (18) | 61 ± 3 (5) | 101 ± 5 (5) | 49 ± 10 (20) | 60 ± 3 (5) | 103 ± 4 (4) |

| 2 | C28H16O5 | Naphthofluorescein | 27 ± 7 (26) | 39 ± 14 (37) | 76 ± 4 (6) | 41 ± 13 (31) | 43 ± 12 (28) | 75 ± 3 (5) |

| 3 | C21H26N4O8 | Trp-Glu-Glu | 52 ± 4 (8) | 53 ± 3 (5) | 28 ± 3 (11) | 55 ± 7 (12) | 57 ± 6 (11) | 30 ± 3 (11) |

| 4 | C9H6O3 | Umbelliferone | 31 ± 1 (3) | 26 ± 2 (7) | 54 ± 3 (6) | 31 ± 2 (5) | 25.3 ± 0.6 (2) | 61 ± 7 (11) |

| 5 | C16H18O9 | Chlorogenic Acida | 207 ± 19 (9) | 143 ± 15 (11) | 305 ± 31 (10) | 200 ± 19 (9) | 142 ± 10 (7) | 299 ± 43 (15) |

| 6 | C10H10O4 | Methyl caffeate | 2.52 ± 0.09 (3) | 42 ± 3 (7) | 33 ± 3 (10) | 2.55 ± 0.03 (1) | 43 ± 3 (7) | 32.7 ± 0.6 (2) |

| 7 | C10H12O5 | Danielone | 5.3 ± 0.1 (2) | 79 ± 10 (13) | 71 ± 3 (4) | 5.42 ± 0.08 (1) | 79 ± 5 (6) | 70 ± 5 (6) |

| 8 | C8H6O3 | Piperonal | 2.05 ± 0.05 (3) | 37 ± 4 (12) | 32 ± 4 (11) | 1.8 ± 0.3 (15) | 39 ± 6 (14) | 32 ± 3 (9) |

| 9 | C16H22O10 | Geniposidic acid | 8.6 ± 0.2 (2) | 127 ± 3 (3) | 72 ± 7 (10) | 8.3 ± 0.7 (8) | 130 ± 5 (4) | 70 ± 6 (9) |

| 10 | C16H18O8 | p-Coumaroyl quinic acid | 51 ± 7 (14) | 4 ± 1 (32) | 11 ± 1 (9) | 49 ± 6 (12) | 4 ± 1 (38) | 11 ± 1 (9) |

| 11 | C16H22O9 | Tarennoside | 3.9 ± 0.2 (4) | 82.0 ± 0.8 (1) | 241.00 ± 0.07 (0.03) | 4.0 ± 0.1 (3) | 82 ± 1 (1) | 239 ± 3 (1) |

| 12 | C15H26N6O6 | Asp-Arg-Pro | 40 ± 4 (11) | 63 ± 12 (19) | 91 ± 7 (8) | 51 ± 18 (36) | 66 ± 10 (15) | 89 ± 6 (7) |

| 13 | C16H28N6O8 | Arg-Glu-Glu | 8 ± 1 (14) | 11.8 ± 0.7 (6) | 1.3 ± 0.1 (9) | 7 ± 2 (29) | 11.8 ± 0.7 (6) | 1.3 ± 0.1 (9) |

| 14 | C10H12O4 | Paeonilactone B | 2.79 ± 0.03 (1) | 51.25 ± 0.09 (0.2) | 136 ± 6 (4) | 2.78 ± 0.03 (1) | 51.0 ± 0.4 (1) | 137 ± 5 (3) |

| 15 | C20H27N5O6 | Thr-Gln-Trp | 43 ± 4 (10) | 42 ± 7 (16) | 64 ± 2 (3) | 46 ± 6 (13) | 45 ± 8 (17) | 63 ± 3 (5) |

| 16 | C20H24N4O6 | Pro-Trp-Asp | 34 ± 4 (12) | 33 ± 6 (19) | 55 ± 2 (3) | 35 ± 3 (8) | 32 ± 5 (15) | 54 ± 2 (3) |

| 17 | C15H21N5O8 | Asp-Glu-His | 25 ± 1 (4) | 35 ± 1 (4) | 36 ± 5 (15) | 27 ± 4 (13) | 35 ± 1 (4) | 34 ± 5 (16) |

| 18 | C16H18N6O4 | 2-Phenylaminoadenosine | 110 ± 11 (10) | 36 ± 6 (17) | 108 ± 2 (2) | 110 ± 11 (10) | 37 ± 5 (14) | 107 ± 2 (1) |

| 19 | C27H30O16 | Rutin | 316.4 ± 0.6 (0.2) | 39 ± 4 (9) | 55 ± 1 (2) | 321 ± 8 (2) | 39 ± 2 (6) | 55 ± 1 (2) |

| 20 | C21H18O12 | Luteolin 3′-glucuronide | 107 ± 10 (9) | 122 ± 6 (5) | 111 ± 11 (10) | 128 ± 18 (14) | 109 ± 15 (14) | 131 ± 20 (15) |

| 21 | C21H20O11 | Luteolin-7-O-glucosidea | 64 ± 4 (6) | 178 ± 3 (2) | 294 ± 6 (2) | 62 ± 2 (3) | 178.4 ± 0.8 (0.5) | 285 ± 9 (3) |

| 22 | C21H26O12 | Plumieride | 324 ± 17 (5) | 462 ± 8 (2) | 200 ± 11 (6) | 327 ± 7 (2) | 471 ± 11 (2) | 199 ± 11 (6) |

| 23 | C29H36O15 | Forsythoside Aa | 290 ± 24 (8) | 398 ± 12 (3) | 172 ± 2 (1) | 285 ± 9 (3) | 414 ± 17 (4) | 171 ± 1 (0.4) |

| 24 | C13H28N6O8 | Zwittermicin A | 5.8 ± 0.3 (5) | 28 ± 2 (6) | 1.3 ± 0.1 (11) | 6 ± 1 (16) | 22 ± 5 (20) | 1.5 ± 0.2 (16) |

| 25 | C20H20O5 | Morachalcone A | 98.8 ± 0.3 (0.3) | 97 ± 9 (10) | 66 ± 2 (3) | 98.7 ± 0.3 (0.3) | 99 ± 7 (8) | 64 ± 4 (6) |

| 26 | C26H32O11 | Brusatol | 258 ± 14 (5) | 227 ± 10 (4) | 164 ± 2 (1) | 261 ± 2 (1) | 226 ± 5 (2) | 164 ± 2 (1) |

| 27 | C27H30O14 | Isofurcatain 7-O-glucoside | 2.7 ± 0.3 (10) | 85.7 ± 0.4 (0.5) | 178 ± 2 (1) | 2.7 ± 0.2 (8) | 85.8 ± 0.3 (0.4) | 175 ± 4 (2) |

| 28 | C25H24O12 | Apigenin 7-(3″,4″-diacetylglucoside) | 14.3 ± 0.1 (1) | 92 ± 1 (1) | 98 ± 2 (2) | 14.3 ± 0.1 (1) | 91.4 ± 0.9 (1) | 98 ± 1 (1) |

| 29 | C21H20O10 | Isovitexin | 256 ± 17 (6) | 162 ± 1 (0.6) | 138 ± 7 (5) | 257 ± 11 (4) | 161 ± 2 (2) | 138 ± 5 (3) |

| 30 | C27H34O11 | Undulatone | 23 ± 2 (7) | 82 ± 6 (8) | 91 ± 25 (28) | 23 ± 2 (7) | 84 ± 6 (7) | 91 ± 25 (27) |

| 31 | C21H18O11 | Baicalina | 62 ± 2 (4) | 30 ± 3 (9) | 229 ± 17 (8) | 56 ± 5 (8) | 32 ± 2 (5) | 221 ± 9 (4) |

| 32 | C27H34O11 | Forsythina | 1051 ± 90 (9) | 463 ± 17 (4) | 898 ± 31 (3) | 1056 ± 25 (2) | 463 ± 11 (2) | 895 ± 26 (3) |

| 33 | C22H20O12 | Hispidulin 7-glucuronide | 20 ± 2 (12) | 12.17 ± 0.05 (0.4) | 59 ± 3 (5) | 21 ± 2 (10) | 12.16 ± 0.04 (0.4) | 58 ± 3 (4) |

| 34 | C21H18O10 | Chrysin 7-glucuronide | 376 ± 25 (7) | 306 ± 12 (4) | 461 ± 22 (5) | 382 ± 20 (5) | 308 ± 10 (3) | 456 ± 18 (4) |

| 35 | C22H20O11 | Wogonin 7-glucuronide | 888 ± 75 (8) | 840 ± 52 (6) | 1278 ± 37 (3) | 905 ± 61 (7) | 852 ± 42 (5) | 1268 ± 31 (2) |

| 36 | C21H18O11 | Apigenin 7-glucuronide | 47 ± 2 (4) | 21.9 ± 0.8 (3) | 86 ± 1 (1) | 48 ± 2 (3) | 21.9 ± 0.5 (2) | 85 ± 2 (2) |

| 37 | C16H12O6 | Kaempferide | 22 ± 1 (4) | 34.6 ± 0.1 (0.4) | 37.2 ± 0.3 (1) | 21.7 ± 0.7 (3) | 34.2 ± 0.4 (1) | 36 ± 2 (4) |

| 38 | C15H10O5 | Baicalein | 275 ± 14 (5) | 212 ± 4 (2) | 264 ± 26 (10) | 278 ± 6 (2) | 213 ± 5 (2) | 271 ± 10 (4) |

| 39 | C21H24O6 | Kadsurin A | 50.1 ± 0.7 (1) | 20 ± 1 (6) | 31 ± 1 (3) | 50.2 ± 0.5 (1) | 19 ± 1 (5) | 31.6 ± 0.8 (2) |

| 40 | C16H12O5 | Wogonin | 119 ± 6 (5) | 161 ± 4 (3) | 169 ± 1 (1) | 118 ± 3 (2) | 161 ± 3 (2) | 166 ± 3 (2) |

| 41 | C17H14O6 | 5,3′-Dihydroxy-7,4′-dimethoxy-4-phenylcoumarin | 12.8 ± 0.7 (5) | 22.3 ± 0.8 (4) | 28 ± 1 (5) | 12 ± 1 (8) | 21 ± 2 (7) | 27 ± 3 (10) |

| 42 | C19H18O8 | Skullcapflavone II | 27 ± 2 (9) | 13 ± 1 (8) | 73 ± 6 (8) | 28 ± 1 (4) | 13.0 ± 0.7 (5) | 72 ± 4 (6) |

| 43 | C15H22O2 | Eremophilenolide | 4.4 ± 0.3 (7) | 4.6 ± 0.5 (10) | 6.5 ± 0.6 (9) | 4.4 ± 0.2 (5) | 4.7 ± 0.4 (8) | 6.3 ± 0.5 (7) |

| 44 | C24H50NO7P | PE (19:0/0:0) | 147 ± 16 (11) | 13.9 ± 0.4 (3) | 99 ± 5 (5) | 150 ± 13 (9) | 14.0 ± 0.3 (2) | 98 ± 4 (4) |

| 45 | C19H38O4 | 1-Monopalmitin | 13 ± 2 (12) | 11 ± 1 (10) | 17.4 ± 0.9 (5) | 13 ± 1 (9) | 11.1 ± 0.9 (8) | 17.2 ± 0.7 (4) |

| 46 | C51H84O15 | 1,2-Di-(9Z,12Z,15Z-octadecatrienoyl)-3-(galactosyl-alpha-1-6-galactosyl-beta-1)-glycerol | 88 ± 3 (3) | 16.8 ± 0.9 (5) | 75 ± 1 (2) | 89 ± 2 (2) | 16.6 ± 0.7 (4) | 74 ± 1 (1) |

| 47 | C45H74O10 | 1,2-Di-(9Z,12Z,15Z-octadecatrienoyl)-3-O-Beta-d-galactosyl-sn-glycerol | 68 ± 6 (9) | 54.8 ± 0.4 (1) | 62 ± 4 (6) | 69 ± 5 (8) | 58 ± 6 (11) | 58 ± 7 (12) |

G granules, O oral liquid, T tablet

aQ markers

bPer equivalent to 15.0 g of raw herbal pieces

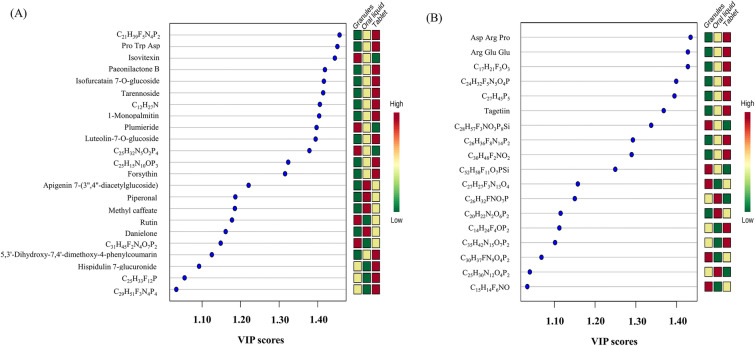

Multivariate analysis

Multivariate analysis was performed on the UHPLC-MS data obtained from the samples of three SHL preparation forms. The unsupervised principal component analysis (PCA) score plot [36] was first constructed to assess the similarities of chemical components among the three SHL preparation forms and the precision of replicate sample measurements of each preparation form, then the supervised partial least squares discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) score plot was established for pattern recognition of the three SHL preparation forms.

As shown in the PCA score plot (Fig. 4A), the variations of the chemical components among the three SHL forms were evident. The principal component 1 (PC1) and principal component 2 (PC2) scores were 49.6% and 32.7%, respectively, accounting for 82.7% of the total variance. The close grouping of replicate measurements of each preparation form in the PCA score plot indicated excellent precision of the analytical method. The PLS-DA score plot (Fig. 4B) confirmed the finding of the PCA score plot. It displayed distinctive patterns of the three SHL preparation forms, which could be used for product differentiation and recognition. Among the 95 components commonly found in the three SHL preparation forms, the components with variable importance in projection (VIP) scores > 1.00 were considered to contribute to the significant variations in the PLS-DA score plot. These components were listed in Fig. 5, including 23 detected by the positive ionization mode (Fig. 5A) and 18 detected by the negative ionization mode (Fig. 5B), and their VIP scores were tabulated in Additional file 12: Table S9.

Fig. 4.

Multivariate data analysis. A The 2D PCA score plot, and B the 2D PLS-DA score plot of the three SHL preparation forms

Fig. 5.

The common components found in all three SHL preparation forms with VIP scores ≥ 1.00. A Positive ionization mode, and B negative ionization mode

Pharmacologically active components in SHL formula

Despite significant variations in the chemical compositions of the granule, oral liquid, and tablet forms of SHL formula, these preparation forms have been used interchangeably in clinical practices to treat the same illnesses. Therefore, it is rational to think that the pharmacologically active components were among the 47 components commonly identified in all three SHL preparation forms. In contrast, the unique components in each SHL preparation form may come from the different geographic origins, agricultural and industrial pollutions of the herbs, and the byproducts associated with the unique manufacturing conditions.

The pharmacological activities of the 47 commonly identified chemical components were explored through database searching and text mining. Twenty out of 47 were found to have various pharmacological activities (Table 4), including anti-bacterial, anti-viral, antipyretic, anti-inflammatory, and anti-influenza activities, and immunostimulatory, anti-cancer, anti-oxidative and antibiotic [37–57], etc. These pharmacologically active components may serve alone or in combination as lead compounds for new drug development and used as ligands for retrieval of protein targets for the mechanistic study of SHL formula in treating URTIs or other related diseases.

Table 4.

Pharmacologically active components found in SHL formula

| No. | Name | PubChem CID | CAS | Reported pharmacological activity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Chlorogenic Acida | 1794427 | 327-97-9 | Antioxidant; antithrombotic; anti-influenza [37]; anti-bacterial [38] |

| 2 | Luteolin-7-O-glucosidea | 5280637 | 5373-11-5 | Antioxidant; anti-inflammatory [39] |

| 3 | Forsythoside Aa | 5281773 | 79916-77-1 | Anti-pyretic [40] |

| 4 | Baicalina | 64982 | 21967-41-9 | Anti-viral [41] |

| 5 | Forsythina | 101712 | 487-41-2 | Regulation of lipid [42] |

| 6 | Umbelliferone | 5281426 | 93-35-6 | Antioxidant; anti-cancer [43] |

| 7 | Piperonal | 8438 | 120-57-0 | Antiobesity [44] |

| 8 | Methyl caffeate | 689075 | 3843-74-1 | Antihyperglycemic and antidiabetic [45] |

| 9 | Danielone | 146167 | 90426-22-5 | Antifungal activity [46] |

| 10 | Geniposidic acid | 443354 | 27741-01-1 | Anti-tumor promoting activity [47] |

| 11 | Rutin | 5280805 | 1340-08-5 | Antimycobacterial [48] |

| 12 | Luteolin 3′-glucuronide | 10253785 | 53527-42-7 | Flavonoid, as a sedative and digestive [49] |

| 13 | Plumieride | 72319 | 511-89-7 | Immunostimulatory activity [50] |

| 14 | Brusatol | 73432 | 14907-98-3 | Anti-cancer (pancreatic cancer) [51] |

| 15 | Isovitexin | 162350 | 29702-25-8 | Anti-cancer [52] |

| 16 | Kaempferide | 5281666 | 491-54-3 | Protects against myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury [53] |

| 17 | Baicalein | 5281605 | 491-67-8 | Anti-cancer (non-small cell lung cancer) [54] |

| 18 | Wogonin | 5281703 | 632-85-9 | Anti-cancer (lymphoma) [55] |

| 19 | Skullcapflavone II | 124211 | 55084-08-7 | Attenuates ovalbumin-induced allergic rhinitis [56] |

| 20 | Zwittermicin A | 44474866 | 155547-95-8 | Antibiotic, suppressing plant disease [57] |

aQ-markers

Conclusions

A UHPLC-QTOF-MS/MS method has been implemented for untargeted and targeted metabolomics analyses of the SHL formula. This method is accurate and precise and can be used for component profiling, identification, semi-quantitative analysis, and cross-comparison among different TCM preparation forms. In this work, the chemical components of the SHL formula in three preparation forms (i.e., granule, oral liquid, and tablet) were obtained, the 47 common components were identified and quantitated, and the pharmacologically active components were investigated. PCA and PLS-DA were performed to assess and visualize the correlations and differences among the three SHL preparation forms and the reproducibility of technical and biological replicates. This method is useful for component fingerprinting, quality assessment, and counterfeit detection of SHL formulas and related products.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Appendix S1. Preparation of MS tuning mix and reference mass solutions.

Additional file 2: Figure S1. The average MS/MS spectra of the 47 commonly identified components in all three SHL preparation forms for all collision energies (10, 20, and 40 eV) by their predominant ESI modes.

Additional file 3: Figure S2. The proposed fragmentation pathways of the commonly identified compounds.

Additional file 4: Table S1. The chemical components identified with both names and formulas in SHL granule preparation form.

Additional file 5: Table S2. The chemical components identified only with formulas in SHL granule preparation form.

Additional file 6: Table S3. The chemical components identified with both names and formulas in SHL oral liquid preparation form.

Additional file 7: Table S4. The chemical components identified with only formulas in SHL oral liquid preparation form.

Additional file 8: Table S5. The chemical components identified with both names and formulas in SHL tablet preparation form.

Additional file 9: Table S6. The chemical components identified with only formulas in SHL tablet preparation form.

Additional file 10: Table S7. The chemical components found in each SHL preparation forms.

Additional file 11: Table S8. The common chemical components unidentified (or identified with formulas only) in all three SHL preparation forms.

Additional file 12: Table S9. The common components found in all three SHL preparation forms with VIP scores > 1.00.

Acknowledgements

GX is grateful for the financial support of the Graduate Student Research Award from Cleveland State University.

Abbreviations

- SHL

Shuang Huang Lian

- TCM

Traditional Chinese medicine

- URTIs

Upper respiratory tract infections

- UHPLC-QTOF-MS/MS

Ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography and quadrupole time-of-flight tandem mass spectrometry

- PCA

Principal component analysis

- PLS-DA

Partial least squares discriminant analysis

- RSV

Respiratory syncytial virus

- MFs

Matrix factors

- CV

Coefficient variation

- AJS-ESI

Agilent jet stream electrospray ionization

- PEEK

Polyether ether ketone

- CE

Collision energy

- MPP

Mass profiler professional (MPP)

- TCMID

Traditional Chinese medicine integrated database

- TCMSP

Traditional Chinese medicine systems pharmacology

- PC1

Principal component 1

- PC2

Principal component 2

- VIP

Variable importance in projection

- Q markers

Quality markers

Author contributions

GX conducted the work, performed data acquisition, analysis and interpretation, and drafted the manuscript; YS supplied the various SHL preparation forms, contributed to the literature search and participated in the project discussion; YX conceived the work, supervised the study, and conducted the manuscript review and revision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Graduate Student Research Award from Cleveland State University.

Availability of data and materials

Data beyond those in Additional files are available upon request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Yes.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Ye JX, Wei W, Quan LH, Liu CY, Chang Q, Liao YH. An LC-MS/MS method for the simultaneous determination of chlorogenic acid, forsythiaside A and baicalin in rat plasma and its application to pharmacokinetic study of Shuang-huang-lian in rats. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2010;52:625–630. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2010.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Han J, Ye M, Guo H, Yang M, Wang BR, Guo DA. Analysis of multiple constituents in a Chinese herbal preparation Shuang-Huang-Lian oral liquid by HPLC-DAD-ESI-MSn. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2007;44:430–438. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2007.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang H, Chen Q, Zhou W, Gao S, Lin H, Ye S, et al. Chinese medicine injection shuanghuanglian for treatment of acute upper respiratory tract infection: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Evid Based Complement Altern Med. 2013;987326:1–7. doi: 10.1155/2013/987326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ni LJ, Zhang LG, Hou J, Shi WZ, Guo ML. A strategy for evaluating antipyretic efficacy of Chinese herbal medicines based on UV spectra fingerprints. J Ethnopharmacol. 2009;124:79–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2009.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu C, Douglas RM. Chinese herbal medicines in the treatment of acute respiratory infections: a review of randomised and controlled clinical trials. Med J Aust. 1998;169:579–582. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1998.tb123423.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen X, Howard OM, Yang X, Wang L, Oppenheim JJ, Krakauer T. Effects of Shuanghuanglian and Qingkailing, two multi-components of traditional Chinese medicinal preparations, on human leukocyte function. Life Sci. 2002;70:2897–2913. doi: 10.1016/S0024-3205(02)01541-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Song ZJ, Johansen HK, Moser C, Faber V, Kharazmi A, Rygaard J, et al. Effects of Radix Angelicae sinensis and shuanghuanglian on a rat model of chronic Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia. Chin Med Sci J. 2000;15:83–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang YH, Xu KJ, Jiang WS. Experimental and clinical study of shuanghuanglian aerosol in treating acute respiratory tract infection. Zhongguo Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Za Zhi. 1995;15:347–350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang FX, Li M, Yao ZH, Li C, Qiao LR, Shen XY, et al. A target and nontarget strategy for identification or characterization of the chemical ingredients in Chinese herb preparation Shuang-Huang-Lian oral liquid by ultra-performance liquid chromatography-quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Biomed Chromatogr. 2018;32:e4110. doi: 10.1002/bmc.4110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kong XT, Fang HT, Jiang GQ, Zhai SZ, O'Connell DL, Brewster DR. Treatment of acute bronchiolitis with Chinese herbs. Arch Dis Child. 1993;68:468–471. doi: 10.1136/adc.68.4.468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen L, Hakamata H, Kusu F, Wang Z, Gao H, Kotani A. Simultaneous determination of various bioactive redox components in Shuang-Huang-Lian preparations using a novel three-channel isocratic elution liquid chromatography with electrochemical detection system. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2014;95:93–101. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2014.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yan GL, Zhang AH, Sun H, Han Y, Shi H, Zhou Y, et al. An effective method for determining the ingredients of Shuanghuanglian formula in blood samples using high-resolution LC-MS coupled with background subtraction and a multiple data processing approach. J Sep Sci. 2013;36:3191–3199. doi: 10.1002/jssc.201300529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chinese Pharmacopoeia Commission . Pharmacopoeia of the People’s Republic of China. Beijing: Chinese Pharmacopoeia Commission; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ye J, Song X, Liu Z, Zhao X, Geng L, Bi K, et al. Development of an LC-MS method for determination of three active constituents of Shuang-huang-lian injection in rat plasma and its application to the drug interaction study of Shuang-huang-lian freeze-dried powder combined with levofloxacin injection. J Chromatogr B Anal Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2012;898:130–135. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2012.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen J, Li BQ, Zhai HL, Lü WJ, Zhang XY. A practical application of wavelet moment method on the quantitative analysis of Shuanghuanglian oral liquid based on three-dimensional fingerprint spectra. J Chromatogr A. 2014;1352:55–61. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2014.05.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Luan L, Wang G, Lin R. HPLC and chemometrics for the quality consistency evaluation of Shuanghuanglian injection. J Chromatogr Sci. 2014;52:707–712. doi: 10.1093/chromsci/bmt104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhou XJ, Chen J, Li YD, Jin L, Shi YP. Holistic analysis of seven active ingredients by micellar electrokinetic chromatography from three medicinal herbs composing Shuanghuanglian. J Chromatogr Sci. 2015;53:1786–1793. doi: 10.1093/chromsci/bmv067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang TB, Yue RQ, Xu J, Ho HM, Ma DL, Leung CH, et al. Comprehensive quantitative analysis of Shuang-Huang-Lian oral liquid using UHPLC-Q-TOF-MS and HPLC-ELSD. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2015;102:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2014.08.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang H, Zhang X, Wang D, Sun H, Lan Y, Jiang H, et al. An on-line analytical approach for detecting haptens in Shuang-huang-lian powder injection. J Chromatogr A. 2017;1513:126–139. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2017.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sun H, Liu M, Lin Z, Jiang H, Niu Y, Wang H, et al. Comprehensive Identification of 125 multifarious constituents in Shuang-huang-lian powder injection by HPLC-DAD-ESI-IT-TOF-MS. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2015;115:86–106. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2015.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hopkins AL. Network pharmacology: the next paradigm in drug discovery. Nat Chem Biol. 2008;4:682–690. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang X, Gu J, Cao L, Li N, Ma Y, Su Z, et al. Network pharmacology study on the mechanism of traditional Chinese medicine for upper respiratory tract infection. Mol Biosyst. 2014;10:2517–2525. doi: 10.1039/C4MB00164H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kind T, Fiehn O. Seven golden rules for heuristic filtering of molecular formulas obtained by accurate mass spectrometry. BMC Bioinform. 2007;8:105. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-8-105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Traditional Chinese medicine integrated database. www.megabionet.org/tcmid/. Accessed 09 Jan 2022.

- 25.Traditional Chinese medicine systems pharmacology database and analysis platform. https://tcmsp-e.com/. Accessed 09 Jan 2022.

- 26.Ru J, Li P, Wang J, Zhou W, Li B, Huang C, et al. TCMSP: a database of systems pharmacology for drug discovery from herbal medicines. J Cheminform. 2014;6:13. doi: 10.1186/1758-2946-6-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.SIRIUS. https://bio.informatik.uni-jena.de/software/sirius/. Accessed 05 Apr 2022.

- 28.MetaboAnalyst 4.0. https://www.metaboanalyst.ca/. Accessed 09 Jan 2022.

- 29.Chong J, Soufan O, Li C, Caraus I, Li S, Bourque G, et al. MetaboAnalyst 4.0: towards more transparent and integrative metabolomics analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:W486–W494. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Banerjee P, Ghosh S, Dutta M, Subramani E, Khalpada J, Roychoudhury S, et al. Identification of key contributory factors responsible for vascular dysfunction in idiopathic recurrent spontaneous miscarriage. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e80940. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Farrés M, Platikanov S, Tsakovski S, Tauler R. Comparison of the variable importance in projection (VIP) and of the selectivity ratio (SR) methods for variable selection and interpretation. J Chemom. 2015;29:528–536. doi: 10.1002/cem.2736. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hill AW, Mortishire-Smith RJ. Automated assignment of high-resolution collisionally activated dissociation mass spectra using a systematic bond disconnection approach. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2005;19:3111–3118. doi: 10.1002/rcm.2177. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dührkop K, Fleischauer M, Ludwig M, Aksenov AA, Melnik AV, Meusel M, et al. SIRIUS 4: a rapid tool for turning tandem mass spectra into metabolite structure information. Nat Methods. 2019;16:299–302. doi: 10.1038/s41592-019-0344-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dührkop K, Shen H, Meusel M, Rousu J, Böcker S. Searching molecular structure databases with tandem mass spectra using CSI:FingerID. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:12580–12585. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1509788112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gika HG, Theodoridis GA, Wingate JE, Wilson ID. Within day reproducibility of an HPLC-MS-based method for metabonomic analysis: application to human urine. J Proteome Res. 2007;6:3291–3303. doi: 10.1021/pr070183p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yuk J, Patel DN, Isaac G, Smith K, Wrona M, Olivos HJ, et al. Chemical profiling of ginseng species and ginseng herbal products using UPLC/QTOF-MS. J Braz Chem Soc. 2016;27:1476–1483. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fuentes E, Caballero J, Alarcón M, Rojas A, Palomo I. Chlorogenic acid inhibits human platelet activation and thrombus formation. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e90699. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lou Z, Wang H, Zhu S, Ma C, Wang Z. Antibacterial activity and mechanism of action of chlorogenic acid. J Food Sci. 2011;76:M398–M403. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2011.02213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hwang YJ, Lee EJ, Kim HR, Hwang KA. Molecular mechanisms of luteolin-7-O-glucoside-induced growth inhibition on human liver cancer cells: G2/M cell cycle arrest and caspase-independent apoptotic signaling pathways. BMB Rep. 2013;46:611–616. doi: 10.5483/BMBRep.2013.46.12.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu C, Su H, Wan H, Qin Q, Wu X, Kong X, et al. Forsythoside A exerts antipyretic effect on yeast-induced pyrexia mice via inhibiting transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 function. Int J Biol Sci. 2017;13:65–75. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.18045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li X, Liu Y, Wu T, Jin Y, Cheng J, Wan C, et al. The antiviral effect of baicalin on enterovirus 71 in vitro. Viruses. 2015;7:4756–4771. doi: 10.3390/v7082841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Do MT, Kim HG, Choi JH, Khanal T, Park BH, Tran TP, et al. Phillyrin attenuates high glucose-induced lipid accumulation in human HepG2 hepatocytes through the activation of LKB1/AMP-activated protein kinase-dependent signalling. Food Chem. 2013;136:415–425. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vijayalakshmi A, Sindhu G. Data on efficacy of umbelliferone on glycoconjugates and immunological marker in 7,12-dimethylbenz(a)anthracene induced oral carcinogenesis. Data Brief. 2017;15:216–221. doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2017.09.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Meriga B, Parim B, Chunduri VR, Naik RR, Nemani H, Suresh P, et al. Antiobesity potential of piperonal: promising modulation of body composition, lipid profiles and obesogenic marker expression in HFD-induced obese rats. Nutr Metab. 2017;14:72. doi: 10.1186/s12986-017-0228-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gandhi GR, Ignacimuthu S, Paulraj MG, Sasikumar P. Antihyperglycemic activity and antidiabetic effect of methyl caffeate isolated from Solanum torvum Swartz. fruit in streptozotocin induced diabetic rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 2011;670:623–631. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2011.09.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Echeverri F, Torres F, Quiñones W, Cardona G, Archbold R, Roldan J, et al. Danielone, a phytoalexin from papaya fruit. Phytochemistry. 1997;44:255–256. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(96)00418-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ueda S, Iwahashi Y, Tokuda H. Production of anti-tumor-promoting iridoid glucosides in Genipa americana and its cell cultures. J Nat Prod. 1991;54:1677–1680. doi: 10.1021/np50078a032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sasikumar K, Ghosh AR, Dusthackeer A. Antimycobacterial potentials of quercetin and rutin against Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv. 3 Biotech. 2018;8:427. doi: 10.1007/s13205-018-1450-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Heitz A, Carnat A, Fraisse D, Carnat AP, Lamaison JL. Luteolin 3′-glucuronide, the major flavonoid from Melissa officinalis subsp. officinalis. Fitoterapia. 2000;71:201–202. doi: 10.1016/S0367-326X(99)00118-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Singh J, Qayum A, Singh RD, Koul M, Kaul A, Satti NK, et al. Immunostimulatory activity of plumieride an iridoid in augmenting immune system by targeting Th-1 pathway in balb/c mice. Int Immunopharmacol. 2017;48:203–210. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2017.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Xiang Y, Ye W, Huang C, Lou B, Zhang J, Yu D, et al. Brusatol inhibits growth and induces apoptosis in pancreatic cancer cells via JNK/p38 MAPK/NF-κb/Stat3/Bcl-2 signaling pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2017;487:820–826. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.04.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ganesan K, Xu B. Molecular targets of vitexin and isovitexin in cancer therapy: a critical review. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2017;1401:102–113. doi: 10.1111/nyas.13446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang D, Zhang X, Li D, Hao W, Meng F, et al. Kaempferide protects against myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury through activation of the PI3K/Akt/GSK-3β pathway. Mediat Inflamm. 2017;5278218:1–11. doi: 10.1155/2017/5278218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cathcart MC, Useckaite Z, Drakeford C, Semik V, Lysaght J, Gately K, et al. Anti-cancer effects of baicalein in non-small cell lung cancer in-vitro and in-vivo. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:707. doi: 10.1186/s12885-016-2740-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wu X, Liu P, Zhang H, Li Y, Salmani JM, Wang F, et al. Wogonin as a targeted therapeutic agent for EBV (+) lymphoma cells involved in LMP1/NF-κB/miR-155/PU.1 pathway. BMC Cancer. 2017;17:147. doi: 10.1186/s12885-017-3145-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bui TT, Piao CH, Song CH, Chai OH. Skullcapflavone II attenuates ovalbumin-induced allergic rhinitis through the blocking of Th2 cytokine production and mast cell histamine release. Int Immunopharmacol. 2017;52:77–84. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2017.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.He H, Silo-Suh LA, Handelsman J, Clardy J. Zwittermicin A, an antifungal and plant protection agent from Bacillus cereus. Tetrahedron Lett. 1994;35:2499–2502. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)77154-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Appendix S1. Preparation of MS tuning mix and reference mass solutions.

Additional file 2: Figure S1. The average MS/MS spectra of the 47 commonly identified components in all three SHL preparation forms for all collision energies (10, 20, and 40 eV) by their predominant ESI modes.

Additional file 3: Figure S2. The proposed fragmentation pathways of the commonly identified compounds.

Additional file 4: Table S1. The chemical components identified with both names and formulas in SHL granule preparation form.

Additional file 5: Table S2. The chemical components identified only with formulas in SHL granule preparation form.

Additional file 6: Table S3. The chemical components identified with both names and formulas in SHL oral liquid preparation form.

Additional file 7: Table S4. The chemical components identified with only formulas in SHL oral liquid preparation form.

Additional file 8: Table S5. The chemical components identified with both names and formulas in SHL tablet preparation form.

Additional file 9: Table S6. The chemical components identified with only formulas in SHL tablet preparation form.

Additional file 10: Table S7. The chemical components found in each SHL preparation forms.

Additional file 11: Table S8. The common chemical components unidentified (or identified with formulas only) in all three SHL preparation forms.

Additional file 12: Table S9. The common components found in all three SHL preparation forms with VIP scores > 1.00.

Data Availability Statement

Data beyond those in Additional files are available upon request.