To the Editor—It has been one year since the release of the first SARS-CoV-2 genome1, which provided scientists with critical knowledge about its proteins. Thanks to the unprecedented experimental efforts by the scientists worldwide, we have now obtained structural knowledge of most SARS-CoV-2 proteins by determining proteins’ 3D shapes. Perhaps even more critical is the structural knowledge of the protein complexes that underlie the basics of viral functioning. Months before the experimental protein structures were solved, computational efforts by several groups have provided researchers with accurate 3D models of the viral proteins and their physical interactions with each other and with the host proteins. Given that it is not ‘if’, but ‘when’ a new viral pandemic will emerge2, it is crucial to know if the computational modeling methods can facilitate structural characterization of viral proteins and their essential complexes. After one year of intensive research by the whole community, we have accumulated enough data to evaluate the impact of the computational modeling efforts towards understanding the structural nature of the virus.

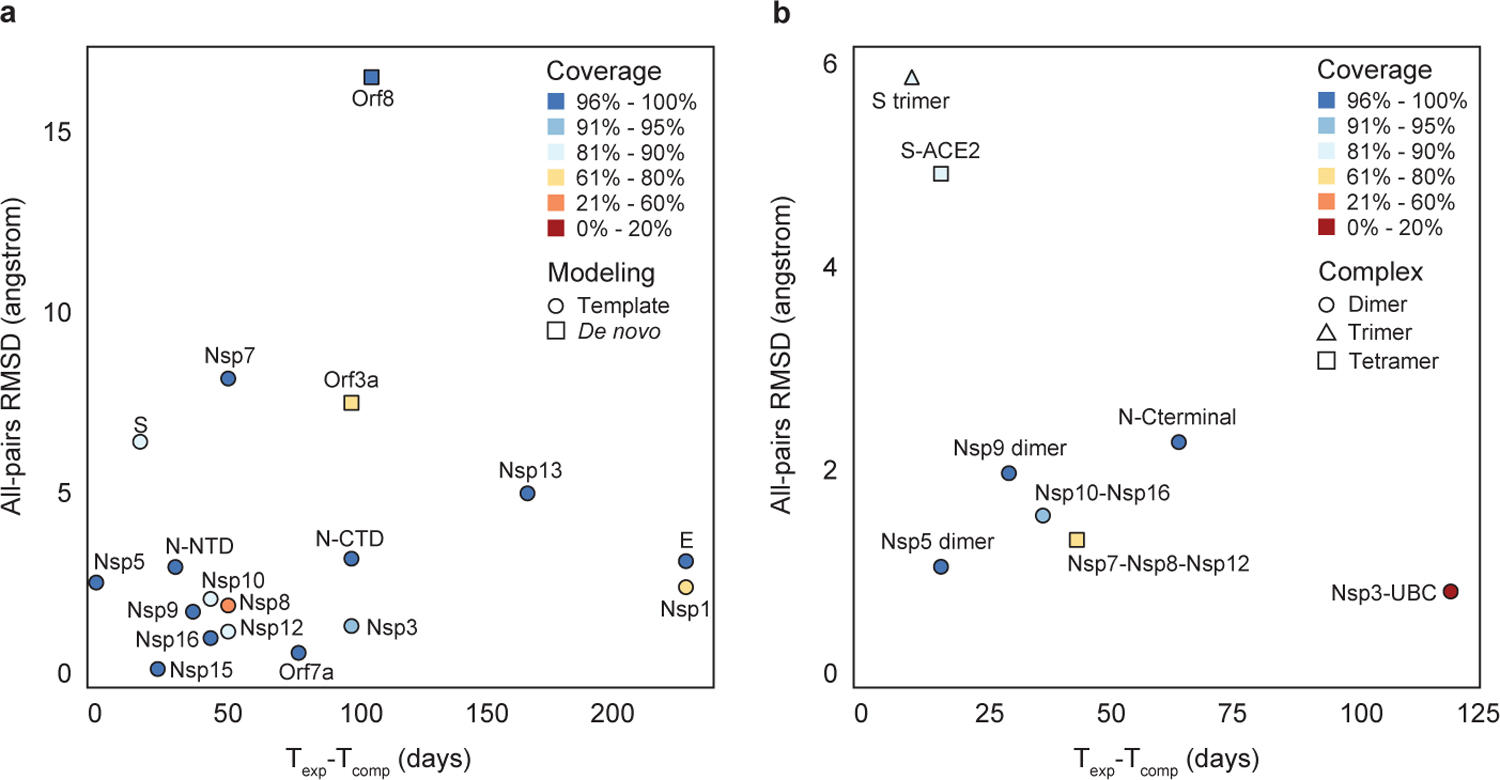

The structural genomics efforts to characterize protein repertoire of a virus are usually carried out by comparative—or template-based—modeling3. A recently emerging technique, de novo protein modeling4, does not require a template structure and may complement well the existing methods. We collected accurate template-based and de novo models of SARS-COV-2 proteins and protein complexes that were also experimentally solved to determine (1) model accuracy when compared with the experimental structure and (2) how far ahead of the experimental structures they were obtained (Fig. 1). We considered comparative models obtained by our group5, and de novo models reported by AlphaFold6 and C-I-TASSER7, which have also contributed to structural characterization of SARS-COV-2 proteins (Fig. 1A, Table S1). We found that of the 29 putative proteins, 16 were experimentally and computationally resolved, partially or fully, while five proteins, including key structural protein M, were characterized only computationally. Furthermore, six putative proteins have not been structurally characterized at all. The computational methods were fairly accurate, producing an average root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) error of 4.1 Å for all 17 proteins (Suppl. Data). On average, a computational model covers roughly 80% of the viral protein sequence, while an experimental structure covers 82%. Most importantly, a 3D model of a viral protein was released on average 86 days earlier than its experimental structure.

Figure 1. Evaluation of computational approaches for modeling 3D structures of SARS-CoV-2 proteins and related protein complexes.

A, analysis of 17 individual proteins that were both experimentally characterized and computationally modeled, using comparative (circles) and de novo (squares) methods. B, analysis of eight protein complexes; each complex consists of two (circle), three (triangle), or four (square) protein subunits. For each modeled protein or protein complex, its RMSD error between the model and experimental structure, the number of days between the releases of experimental and computational structures, and model’s coverage of the protein sequence (represented by colors) are calculated.

Even if we had the structural knowledge of all SARS-COV-2 proteins, our understanding of the virus’ functional units would be far from complete: most, if not all, viral proteins carry out their functions by forming macromolecular complexes. Recent efforts to map all protein complexes formed by SARS-CoV-2 proteins have identified hundreds of putative interactions8. Unfortunately, only a small fraction of these complexes have so far been structurally characterized (Fig. 1B, Table S2): 18 protein complexes have been characterized experimentally, and 16 protein complexes computationally. Overall, for 13 protein complexes the structure was both modeled and resolved experimentally. For five protein complexes, an incorrect oligomer conformation was derived from their homologous complexes. Computational models of the remaining eight protein complexes in correct conformations were accurate, with an average RMSD of 2.6Å over the entire multimeric structure (Suppl. Data). The models were available on average 53 days earlier than experimental structures, covering on average 77.2% of all protein sequences involved in the complex. Lastly, for four modeled complexes, no experimental structures have been obtained to date.

In the 2011 sci-fi movie Contagion that became viral [sic] in 2020, scientists were shown looking at a structure of a viral surface protein bound to the host receptor, just a couple of days after the viral genome was sequenced. What the movie showed is not yet possible experimentally, but can already be achieved using computational modeling. Modeling 3D shapes of the viral proteins and their key complexes brings structural knowledge about the virus several critical months earlier than the experiments are able to. We expect that computational models will be increasingly helpful in designing experiments to test neutralizing antibodies, studying the role of emerging mutations, and understanding the molecular mechanisms behind viral infections. Furthermore, we envision that recent developments of a new generation of AI-driven protein modeling tools, such as AlphaFold 29, will provide even greater improvement in protein models for a novel virus. Still, structural characterization of the macromolecular complexes formed by the viral proteins presents a major challenge. Thus, development of the new de novo methods for accurate characterization of protein complexes, akin to the AI-driven protein structure prediction methods, is required.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

The work has been supported by National Institute of Health (1R01GM135919) to D.K.

Footnotes

Competing interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Zhou P et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature 579, 270–273 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burton DR & Topol EJ Variant-proof vaccines - invest now for the next pandemic. Nature 590, 386–388 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martí-Renom MA et al. Comparative protein structure modeling of genes and genomes. Annual review of biophysics and biomolecular structure 29, 291–325 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuhlman B & Bradley P Advances in protein structure prediction and design. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 20, 681–697 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Srinivasan S et al. Structural genomics of SARS-CoV-2 indicates evolutionary conserved functional regions of viral proteins. Viruses 12, 360 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Senior AW et al. Improved protein structure prediction using potentials from deep learning. Nature 577, 706–710 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zheng W et al. Deep‐learning contact‐map guided protein structure prediction in CASP13. Proteins: Structure, Function, and Bioinformatics 87, 1149–1164 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gordon DE et al. A SARS-CoV-2 protein interaction map reveals targets for drug repurposing. Nature 583, 459–468 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Callaway E ‘It will change everything’: DeepMind’s AI makes gigantic leap in solving protein structures. Nature 588, 203–204 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.