Abstract

Aging is a progressive and complicated bioprocess with overall decline in physiological function. Osteoarthritis (OA) is the most common joint disease in middle-aged and older populations. Since the prevalence of OA increases with age and breakdown of articular cartilage is its major hallmark, OA has long been thought of as “wear and tear” of joint cartilage. Nevertheless, recent studies have revealed that changes in the chondrocyte function and matrix components may reduce the material properties of articular cartilage and predispose the joint to OA. The aberrant gene expression in aging articular cartilage that is regulated by various epigenetic mechanisms plays an important role in age-related OA pathogenesis. This review begins with an introduction to the current understanding of epigenetic mechanisms, followed by mechanistic studies on the aging of joint tissues, epigenetic regulation of age-dependent gene expression in articular cartilage, and the significance of epigenetic mechanisms in OA pathogenesis. Our recent findings on age-dependent expression of two transcription factors, NFAT1 and SOX9, and their roles in the formation and aging of articular cartilage are summarized in the review. Chondrocyte dysfunction in aged mice which is caused by epigenetically mediated spontaneous reduction of NFAT1 expression in articular cartilage is highlighted as an important advance in epigenetics and cartilage aging. Potential therapeutic strategies for age-related cartilage degeneration and OA using epigenetic molecular tools are discussed at the end.

Keywords: Aging, Epigenetics, Articular cartilage, Osteoarthritis, Gene expression, NFAT1

1. Introduction

As one of the age-related diseases, osteoarthritis (OA) is the most common joint disorder and leading cause of chronic disability with high prevalence in the older populations. Although aging has long been recognized as the greatest risk factor for OA, its etiology and how aging predisposes the joint to OA is largely unknown. Due to progressive loss of articular cartilage mainly occurring in load-bearing joints, OA was once considered a mechanical issue which resulted from the “wear and tear” of the joint over time. However, a growing body of evidence from molecular studies has demonstrated that aberrant gene expression regulated by epigenetic mechanisms plays an important role in the pathogenesis of OA [1].

Epigenetics is classically defined as the alterations in the regulatory mechanisms of gene expression without changes in the underlying DNA sequence. Epigenetic alterations include changes in DNA methylation, histone modification and newly defined regulatory non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs). These changes may be retained by the cell throughout its lifespan and passed to future generations for germline cells [2]. Recently, more and more studies on epigenetics have demonstrated the importance of epigenetic regulation of gene expression in normal development, aging, and age-related diseases including OA [3].

In this review, we will summarize the current understanding of epigenetic mechanisms and their relevance to aging of joint tissues, epigenetic regulation of age-dependent gene expression in articular cartilage, and the significance of epigenetic mechanisms in OA pathogenesis. Our recent findings that epigenetically mediated, age-dependent reduction of NFAT1 expression in articular cartilage causes dysfunction of chondrocytes in aged mice are included as an important advance in epigenetics and OA research. Finally, we will discuss novel therapeutic strategies for aging of articular cartilage using epigenetic molecular tools.

2. Epigenetic Mechanisms and Their Relevance to Aging

2.1. DNA methylation

DNA methylation is a biochemical process whereby a methyl group is added to the cytosine or adenine, mainly at the C5 position of CpG dinucleotides, by DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs). At least four DNMTs (DNMT1, DNMT3A, DNMT3B and DNMT3L) have been identified for the de novo DNA methylation or its maintenance [4]. DNA methylation usually suppresses gene expression through two mechanistic modes. The first mode involves direct interference of the methyl group in binding of a protein to its cognate DNA sequence; the second mode involves proteins that are attracted to, rather than repelled by, methyl-CpG [5]. Methylated DNA can be passively or actively demethylated. 5-azacytidine is one of the chemical compounds for passive DNA demethylation, whereas three ten-eleven translocation proteins (TETs) and 5-methycytosine oxidases may be responsible for active DNA demethylation. Both passive and active demethylation may result in increased gene expression. Theoretically, DNA methylation should be widespread in the genome. However, the first global methylomes analysis showed that CpG methylation follows a bimodal distribution, especially in the CpG islands (CGIs), which are averagely 1,000 base pairs long with increased GC density in the promoter regions. DNA hypermethylation has been frequently described as a silent mark for gene transcription. However, a recent study reported that DNA hypermethylation in the gene body could be associated with active gene transcription in specific conditions [6].

2.2. Histone modifications

Histone modifications are enzymatic post-translational modifications which include methylation, acetylation, phosphorylation, sumoylation, ubiquitination, etc. [7]. These modifications primarily occur within the amino-terminal tails of histone proteins which regulate gene expression by changing the chromatin structure. Histone modifications are highly dynamic processes regulated by the opposing action of two families of enzymes. For example, histone acetylation is regulated by opposing action of histone acetyltransferases (HATs) and deacetylases. The notion of “histone codes” have been proposed to explain the role of specific histone modifications. The well-studied histone methylation mainly occurs on lysine (K) residues at positions 4, 9, 20, 27, 36 and 79 of histone 3 (H3). Lysine can be mono-, di-, or tri-methylated. Histone lysine methyltransferases (HKMTs) and histone demethylase dynamically regulate lysine’s methylation status. Lysine-specific demethylase 1 (LSD1) is the first identified lysine demethylase which has been found to target mono- and di-methylation of H3K4 [8], while lysine-specific demethylase 4A (KDM4A) demethylates tri-methylated lysines [9].

The effects of histone modification on gene regulation lie in two aspects: influencing the overall structure of chromatin and/or regulating the binding of transcription effector molecules. With the deposition of transcriptionally active histone codes such as H3K4 methylation, histone acetylation and phosphorylation, the structure of chromatin will be opened as euchromatin, which facilitates the binding of transcription effector molecules to the promoter region and initiates gene expression. When the histone is modified by repressive codes, such as H3K9 and H4K20 methylation, chromatins will be condensed into heterochromatin, which closes the DNA binding sites for transcription effectors and turns off the gene expression.

2.3. Non-coding RNAs

Traditionally, a gene is assumed to be transcribed into messenger RNA (mRNA) and then translated into protein; the discovery of Non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) has extended the definition of a gene. The ncRNA genes produce transcripts functioning as structural, catalytic, or regulatory RNAs rather than being translated into proteins. ncRNAs can be mainly divided into long ncRNAs (lncRNAs, >200 nucleotides) and short ncRNAs (<30 nucleotides) which include microRNAs (miRNAs), short interfering RNAs (siRNAs), and piwi-interacting RNAs (piRNAs). The biogenesis and function of miRNAs has been well-studied. Briefly, they are transcribed from miRNA genes as long primary transcripts (pri-miRNAs) characterized by a hairpin structure and are processed as pre-miRNAs (around 70-nucleotides long) in the nucleus. After being transported into the cytoplasm, pre-miRNAs are cleaved by Dicer and then matured into miRNA of 22–24 nucleotides. Generally, miRNAs modify protein expression mainly at the post-transcriptional level in cytoplasm by binding to a specific target mRNA with a complimentary sequence to induce cleavage, degradation or block translation. Recent progress in the study of ncRNAs has revealed the importance of ncRNAs in development and disease [10].

2.4. Epigenetics in aging

Although many theories have been proposed to explain the aging process, the precise mechanism of aging remains largely unclear [11]. Recent studies have revealed the importance of epigenetic alterations in the aging process and in the pathogenesis of age-related diseases including OA [12,13]. A study of monozygotic twins has revealed significant differences in overall content and genomic distribution of 5-methylcytosine DNA and histone acetylation in older but not in younger twins [14]. A similar result has also been obtained from a longitudinal study in older Swedish monozygotic and dizygotic twins [15], indicative of the environmental effects on epigenetic alterations with age [16].

Recent studies have also suggested that epigenetic remodeling is one of the molecular mechanisms for “inflammaging”, a new term which has been designated to emphasize the importance of chronic and low-grade inflammation in the aging process [17,18]. Inflammaging is a highly significant risk factor for both morbidity and mortality in the elderly population as most age-related diseases share an inflammatory pathogenesis. Nevertheless, the precise etiology of inflammaging and its potential causal role in adverse health outcomes remain largely unknown [19].

3. Aging of Joint Tissues and OA

Recent studies have revealed age-related molecular and cellular changes in joint tissues that may predispose the joint to the development of OA [20].

3.1. Articular cartilage

Articular cartilage is highly specialized connective tissue of diarthrodial joints. Its principal function is to provide a smooth, lubricated surface for articulation and to facilitate the transmission of loads with low friction. Adult articular cartilage contains no blood vessels, nerves, or lymphatics; therefore, it has very limited capacity for intrinsic repair after damage. Chondrocytes are the only resident cell type in articular cartilage. Articular chondrocytes are responsible for maintenance of the extracellular matrix (ECM) which is mainly composed of water, collagens, and proteoglycans. All these components are critical to maintain the unique mechanical properties of articular cartilage.

Loss of the response to mitogenic stimuli is a characteristic of senescent cells; thus, aging chondrocytes rarely divide as a result of telomeres shortening [21]. However, clusters of chondrocyte proliferation are often seen in OA cartilage, which may be a reparative response of chondrocytes to cartilage lesions. The senescent phenotype of articular chondrocytes which is characterized by the increased expression of catabolic cytokines and proteinases is also found in OA chondrocytes, suggesting that articular chondrocyte senescence plays an important role in the development of age-related OA [22].

Aging also affects cartilage matrix. Photographic studies have shown that knee cartilage thins with aging. Age-related changes in amount, crosslinking, architecture, and covalent modification of type II collagen and aggrecan have been reported, especially with the formation and accumulation of advanced glycosylation end production (AGEs) [23]. These changes not only impair the mechanical property of cartilage, but also alter the microenvironment of chondrocytes to survive and maintain its physiological activities. Moreover, age-dependent changes in the subchondral bone have also been found in mouse OA models induced by surgical destabilization of the medial meniscus [20].

Local inflammatory reaction is one of the molecular mechanisms of OA pathogenesis. Up-regulated expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin 1 beta (IL-1β), IL-6 and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) etc., in the joint tissues of human OA and animal OA models has been well documented. The joint inflammatory state contributes to the clinical manifestations of OA, such as joint pain and disfunction [24,25].

3.2. Other joint tissues

OA is a disease of the whole joint. Therefore, age-related changes in other joint tissues, such as bone, synovium, muscle, and ligaments, also could contribute to the development of OA. A multicenter osteoarthritis study using MRI has found that degenerative meniscal tear is common in middle-aged and elderly persons without previous knee surgery which precedes and is strongly associated with the development of radiographic knee OA [26]. Moreover, abnormal matrix organization and/or cellularity (e.g. decreased cellularity, along with cellular hypertrophy and abnormal cell clusters) was observed within the meniscal substance of aged individuals [27]. Similar degenerative changes were also found in the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) of aged individuals [28]. With loss of mass and reduced strength of muscle and subchondral bone, the structure and posture of the joint may be changed, resulting in abnormal mechanical loads onto the articular cartilage and the development of age-related degenerative OA [29].

Synovium is a highly specialized soft tissue that lines the cavity of diarthrodial joints, tendon sheaths, bursae, and fat pads. In synovial joints, the synovium seals the synovial cavity and fluid from surrounding tissues. The synovium is also responsible for the production and maintenance of synovial fluid volume and composition, mainly by producing lubricin and hyaluronic acid. Through the synovial fluid, the synovium also aids in chondrocyte nutrition (together with the subchondral bone), as articular cartilage has no intrinsic vascular or lymphatic supply. In addition to the effect of general cell senescence on the quantity and quality of the synovial fluid, the age-associated chronic inflammation in synovial tissue increases the expression of genes encoding catabolic proteins, such as proinflammatory cytokines (e.g. IL-1β) and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) [29], which participate in the onset or accelerate the progression of OA. Although the mechanisms of inflammation in aging joints are not fully understood, levels of inflammatory mediators typically increase with age even in the absence of acute infection [30].

4. Epigenetic Regulation of Age-Dependent Gene Expression in Articular Cartilage and Its Significance in OA

Cells express (turn on) different fractions of genes during differentiation, maturation, and aging, while the rest of the genes are repressed (turned off). The process of turning genes on and off is known as gene regulation. Age-dependent gene expression and the underlying epigenetic mechanisms play important roles in development, aging, and age-related diseases [31,32]. In normal articular chondrocytes, most catabolic proteases are not expressed or are expressed at a low level, probably because of silencing transcription via epigenetic mechanisms such as DNA methylation. However, osteoarthritic chondrocytes express a set of genes involved in cartilage catabolism such as matrix metalloproteinases (MMP), a disintegrin, and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin motifs (ADAMTS), and proinflammatory cytokines. Clinical trials on OA therapy targeting a single inflammatory mediator or proteinase have been unsuccessful [33], turning the interest of researches to the upstream regulators (e.g. growth factors, transcription factors and epigenetic regulators) which govern the expression of multiple downstream anabolic and catabolic genes. Recent studies on epigenetic regulation of age-dependent expression of growth factors and transcription factors in articular cartilage are highlighted below.

4.1. Age-dependent expression of bone morphogenetic protein-7 in articular cartilage

Although many growth factors, such as transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs), and insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) are proposed to be involved in chondrocyte differentiation and function, BMP-7 (also known as osteogenic protein-1, OP-1) is a growth factor known to be important for articular chondrocyte activities in adults. The alteration in BMP-7 expression level may result in abnormal matrix synthesis and cartilage degradation during OA development [34]. OP-1 mRNA and protein are expressed in adult human articular cartilage and its levels declined with aging and cartilage degeneration which is mediated by increased DNA methylation at OP-1 promoter [35]. However, conditional deletion of BMP-7 from the limb skeleton does not affect articular cartilage formation or limb development and maturation, suggesting that the presence of other BMP family members is sufficient to compensate the function of BMP-7 in the postnatal skeleton [36], implying that BMP-7 is not a key molecule for articular cartilage aging.

4.2. Age-dependent expression of SOX9 and NFAT1 in articular cartilage

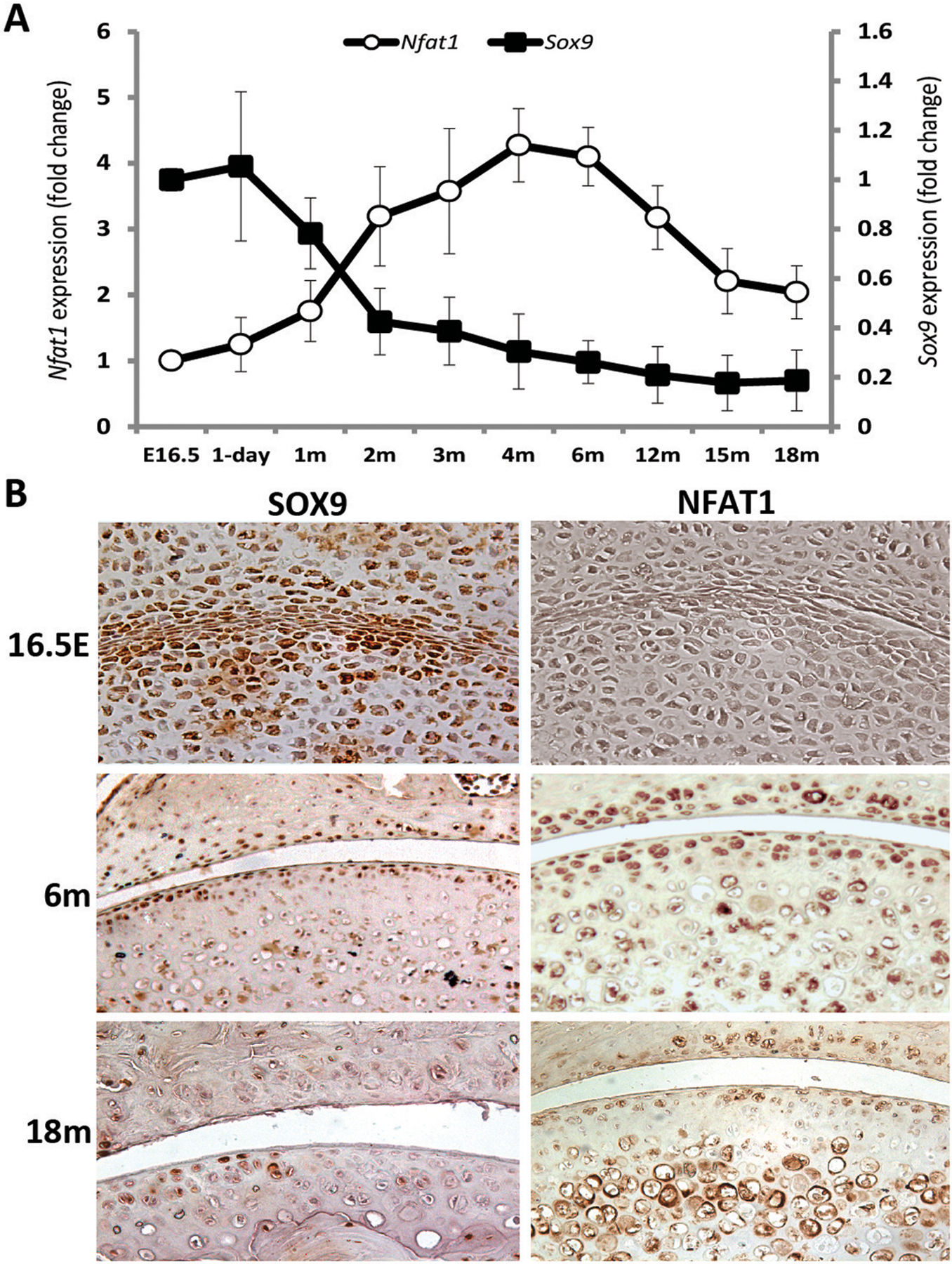

Transcription factor SOX9 is required for chondrocyte differentiation and cartilage formation [37]. SOX9 is one of the earliest markers expressed by mesenchymal stem cells and is essential for expression of cartilage-specific matrix proteins. SOX9 expression was reduced in human OA cartilage, but postnatal inactivation of Sox9 in mouse cartilage resulted in a reduction of proteoglycan content in the articular cartilage without histopathological signs of OA by 18 months of age [38]. Our recent study has demonstrated that SOX9 expression in articular cartilage of mice is highest at embryonic and newborn stages then significantly decreases after the completion of joint development (Figure 1A and 1B) [39]. These findings confirm the importance of SOX9 in cartilage formation and suggest that the physiological demand for SOX9 expression is diminished in adult articular cartilage, although SOX9 may still play a role in the maintenance of cartilage homeostasis.

Figure 1.

Age-dependent expression of SOX9 and NFAT1 in mouse articular cartilage. (A) Age-dependent Sox9 and Nfat1 mRNA levels determined by quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR).. (B) Age-dependent SOX9 and NFAT1 protein expression and localization identified by immunohistochemistry [39,42,43]. E16.5: embryonic day 16.5; m: month.

NFAT1 (NFATc2/NFATp) is a member of the nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT/Nfat) family of transcription factors. NFAT1 was first identified in T cells as a repressor of the immune response in mice, as Nfat1-deficient mice displayed an enhanced immune response [40]. In contrast to BMP-7 and Sox9, whose deletion causes defective bone/cartilage formation with no OA-like changes, mice with global deletion of NFAT1 exhibits normal skeletal development, but begin to show articular chondrocyte dysfunction and OA-like changes as young adults [41,42]. The OA phenotype of Nfat1-deficient mice include osteoarthritic morphology and dysfunction of articular chondrocytes with up-regulated expression of specific proinflammatory cytokines and matrix-degrading proteinases [41,42].

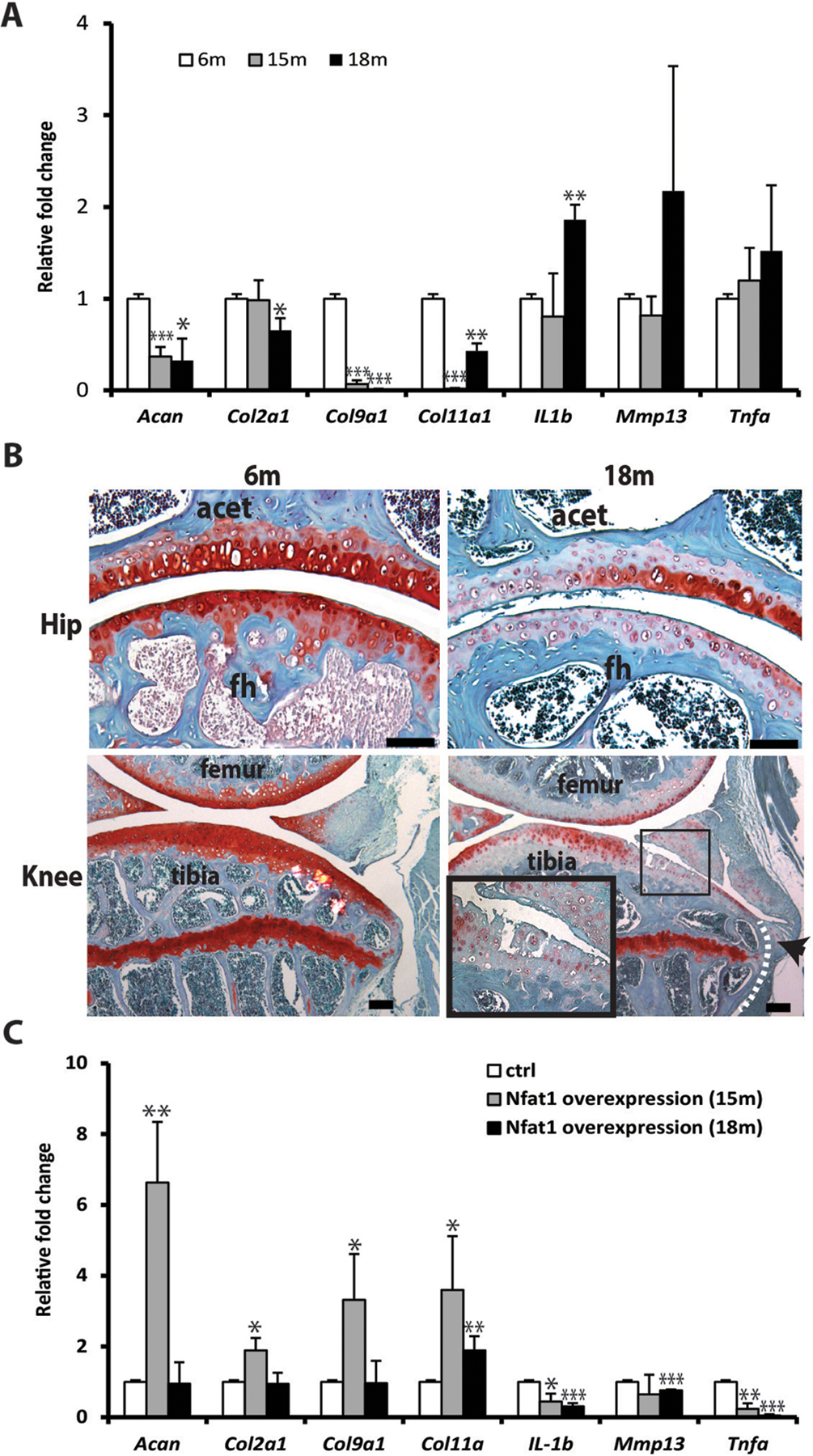

To address why deletion of NFAT1 does not affect skeletal development but causes OA in adult mice, we examined age-dependent NFAT1 expression. NFAT1 expression in murine articular chondrocytes was essentially undetectable at embryonic day 16.5 (E16.5) and postnatal day 1, but was highly expressed at the young adult stage and declined as the mice aged (Figure 1A–B) [42,43]. These finding suggest that NFAT1 is not required for the development of skeletal tissues including articular cartilage; thus, its deletion does not cause dysfunction of articular chondrocytes during development. In contrast, high expression of NFAT1 in articular chondrocytes of young adult mice suggests that NFAT1 is required for maintaining the chondrocyte function in adults; thus, lack of NFAT1 in adult mice causes severe dysfunction of articular chondrocytes and subsequent OA with abnormal expression of numerous genes in articular cartilage and synovium (Figure 2A–B) [41–43]. Importantly, forced expression of Nfat1 in cultured chondrocytes isolated from 15-month-old mice can reverse aberrant expression of specific anabolic and catabolic genes. However, this rescuable effect was reduced in the chondrocytes of 18-month-old mice (Figure 2C), suggesting that the therapeutic efficacy of NFAT1 on age-related dysfunction of articular chondrocytes appears to be more effective in younger mice [41–43]. These results demonstrated that the age-dependent changes in NFAT1 expression may play a critical role in the process of articular cartilage aging.

Figure 2.

Chondrocyte dysfunction and matrix degeneration in articular cartilage of aged mice. (A) Aberrant gene expression in chondrocytes of aged mice; (B) Loss of proteoglycan (red, safranin O staining) and OA-like changes with fibrillation of articular surface (in magnified rectangle) and osteophyte formation at the joint margin (arrowhead), fh: femoral head; acet: acetabulum. (C) Forced overexpression of NFAT1 shows better rescue effect on the dysfunctional chondrocytes from 15-month old mice than that from 18-month old mice [43]. E16.5: embryonic day 16.5; m: month. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

More recently, Greenblatt et al. reported that mice lacking Nfat2 in cartilage displayed no evidence of OA. However, mice lacking both Nfat2 and Nfat1 (Nfatc2) in cartilage developed early joint instability and subsequent OA [44], further confirming that NFAT1 is more important than NFAT2 for cartilage homeostasis and prevention of OA.

4.3. Epigenetic mechanisms underlying the age-dependent SOX9 and NFAT1 expression

To determine if the age-dependent expression of Sox9 and Nfat1 is regulated by epigenetic mechanisms, we first examined the status of histone 3 lysine 4 (H3K4) methylation in the Sox9 promoter region and found that the level of H3K4 dimethylation (H3K4me2, a histone modification linked to transcriptional activation) was highest at E16.5 and significantly reduced from 2 to 18 months. In contrast, histone 3 lysine 9 dimethylation (H3K9me2, a histone modification linked to transcriptional repression) was lowest at E16.5 and significantly increased at 2, 6, and 18 months at specific primer regions [39]. Furthermore, the recruitment of LSD1 to the Sox9 promoter was significantly increased in the articular cartilage of 6-month-old mice compared to the recruitment level of LSD1 at E16.5 when SOX9 was highly expressed. Knockdown of Lsd1 (encoding LSD1) in cultured ACs isolated from the femoral heads of 18-month-old mice increased the expression of Sox9 mRNA and protein which is concomitant with increased H3K4me2 levels. Additionally, the methylation levels of all 5 CpG islands at Sox9 promoter were low at E16.5 and 2 months, but significantly increased at 6 and 12 months. Treatment of articular chondrocytes from 6-month-old mice with 5-AzaC, an inhibitor of DNA methylation, decreased the DNA methylation levels at the CpG islands and resulted in an up-regulated expression of Sox9 mRNA and some of the SOX9 target genes such as Acan and Col11a1. These epigenetic analyses suggest that both DNA methylation and histone methylation are involved in the age-dependent SOX9 expression in mouse articular cartilage [39].

During the developmental stage, Nfat1 is transiently held in a repressed state by a low level of H3K4me2 and a high level of H3K9me2, suggesting that NFAT1 is not required at this stage. In the adult stage, this process is reversed to meet the needs for high NFAT1 expression that is required for maintenance of the adult chondrocyte phenotype. As mice aged, the level of H3K4me2 was decreased over time resulting in decreased NFAT1 expression, while decreased H3K9me2 was associated with increased NFAT1 expression at 2 and 6 months, but not at 12- and 18-months. There is only one CpG island in the promoter region of the Nfat1 gene, therefore, DNA methylation at Nfat1 promoter region had no significant effect on NFAT1 expression in articular cartilage. However, the DNA methylation levels at introns 1 and 10 where enhancer activities have been identified for the Nfat2 gene [45,46] were negatively correlated with the reduced NFAT1 expression in articular chondrocytes of aged mice [43].

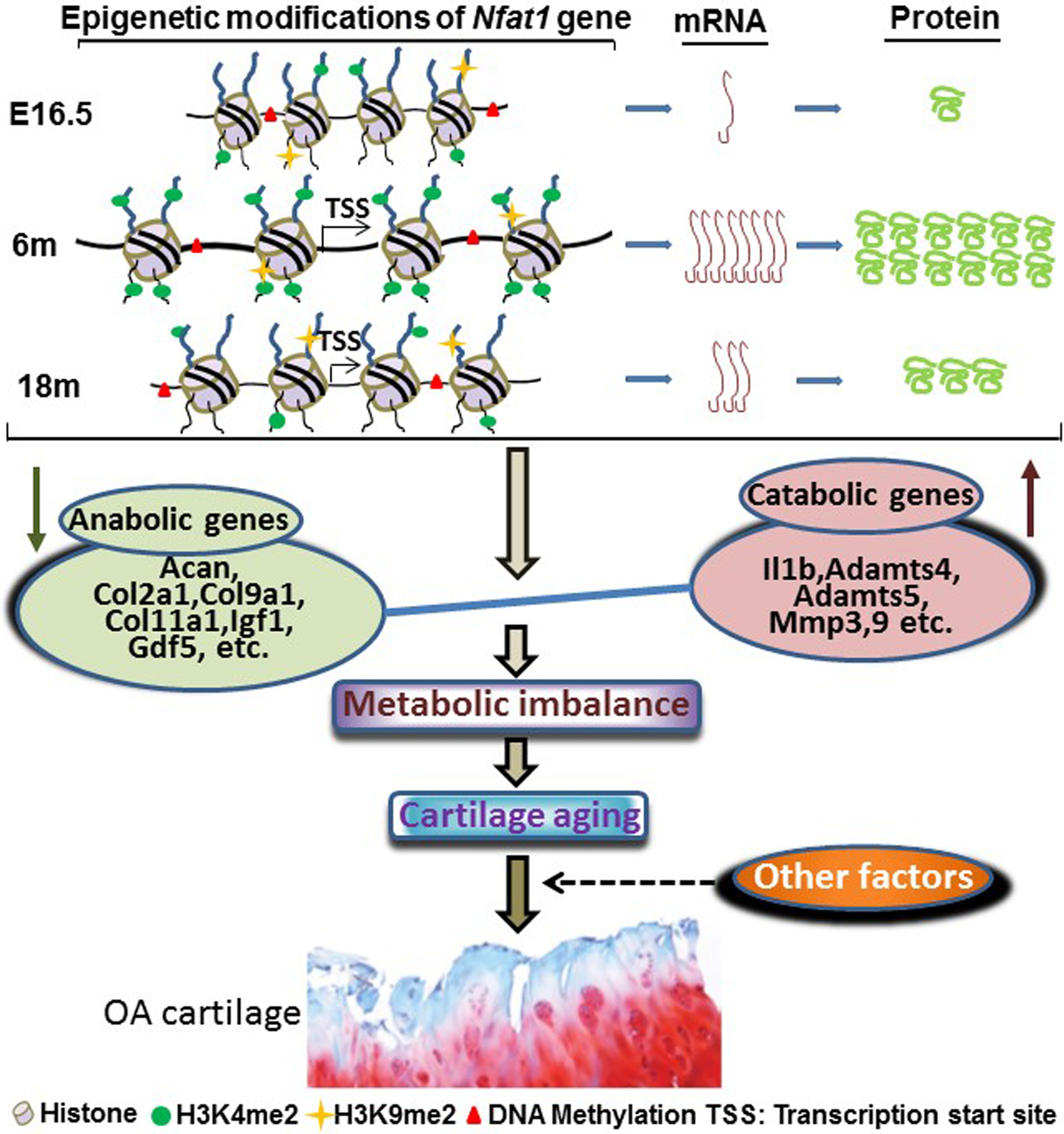

As summarized in Figure 3, our studies have revealed that NFAT1 plays an important role in regulating the transcription of specific anabolic and catabolic genes. The epigenetically regulated spontaneous reduction of NFAT1 expression in articular chondrocytes of aged mice results in imbalanced metabolic activities and degradation of articular cartilage, predisposing the joint of aged mice to OA under mechanical stress.

Figure 3.

Schematic summarization of age-dependent epigenetic regulation of NFAT1 expression in mouse articular cartilage at the mRNA protein levels and the possible mechanisms of NFAT1 reduction-mediated cartilage aging, which predispose the joint to OA under the influence of other factors, including both mechanical stress and biological alternations. Acan: aggrecan; Col2a1: collagen type II alpha 1; Col9a1: collagen type IX alpha 1; Col11a1: collagen type XI alpha 1; Igf1: insulin-like growth factor 1; GDF5: growth differentiation 5; Il1b: interleukin 1β; Adamts: a disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin motifs; Mmp: matrix metalloproteinase

5. Conclusions and Prospects

This review highlights the recent advances in epigenetic regulation of age-dependent gene expression in articular cartilage which has demonstrated the regulatory role of epigenetic mechanisms in aging and OA pathogenesis. Our recent studies have revealed that NFAT1, but not SOX9, is a key transcription factor governing adult articular cartilage homeostasis and aging. Epigenetically regulated spontaneous reduction of NFAT1 expression in articular cartilage of aged mice results in imbalanced metabolic activities as well as cartilage inflammation [43] which may compromise the mechanical properties of cartilage and predispose the joint of aged mice to OA under mechanical stress. This explains, at least in part, why age is the primary risk factor for development of OA. As OA is a disease of whole joint, further studies are needed to elucidate the regulatory mechanisms of NFAT1 expression and function in other joint tissues. The findings we obtained from the mouse model need to be validated in humans.

No proven pharmacologic therapy is currently available to prevent the initiation or permanently reverse the progression of OA. In addition, efforts to develop methods for the surgical and biological repair of damaged articular cartilage face major obstacles due to de-differentiation and dysfunction of newly formed chondrocytes in the repair tissue [47]. Our studies have demonstrated that NFAT1 is a key transcription factor for maintaining the physiological function of articular chondrocytes of adult mice and that the epigenetically mediated spontaneous reduction of NFAT1 is a responsible molecular mechanism for articular cartilage aging. Therefore, NFAT1 would be a promising therapeutic target for treatment of articular cartilage aging and age-related OA.

With the widely increased use of next generation sequencing technologies for quantitative assessment of transcriptional molecules, miRNAs have been discovered to play an epigenetic regulatory role in gene expression. In addition to their regulatory role, many studies have shown that miRNAs are involved in aging and age-related diseases [48]. Further investigations are needed to explore the regulatory effect of specific miRNAs on NFAT1 expression in articular cartilage and other joint tissues and the potential use of miRNAs as therapeutic targets for age-related articular cartilage degeneration and OA [10].

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by the U.S. National Institute of Health (NIH) Grant R01 AR059088 (to J. Wang), the U.S. Department of Defense Research Grant W81XWH-12-1-0304 (to J. Wang), and the Mary A. and Paul R. Harrington Distinguished Professorship Endowment.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Zhang M, Egan B, Wang J: Epigenetic mechanisms underlying the aberrant catabolic and anabolic activities of osteoarthritic chondrocytes. The international journal of biochemistry & cell biology 2015;67:101–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li Y: Epigenetic Mechanisms Link Maternal Diets and Gut Microbiome to Obesity in the Offspring. Frontiers in genetics 2018;9:342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim S, Wyckoff J, Morris AT, Succop A, Avery A, Duncan GE, Michal Jazwinski S: DNA methylation associated with healthy aging of elderly twins. GeroScience 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jin B, Robertson KD: DNA methyltransferases, DNA damage repair, and cancer. Advances in experimental medicine and biology 2013;754:3–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bird A: DNA methylation patterns and epigenetic memory. Genes & development 2002;16:6–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weber M, Hellmann I, Stadler MB, Ramos L, Paabo S, Rebhan M, Schubeler D: Distribution, silencing potential and evolutionary impact of promoter DNA methylation in the human genome. Nature genetics 2007;39:457–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bird A: Perceptions of epigenetics. Nature 2007;447:396–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shi Y, Lan F, Matson C, Mulligan P, Whetstine JR, Cole PA, Casero RA, Shi Y: Histone demethylation mediated by the nuclear amine oxidase homolog LSD1. Cell 2004;119:941–953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Whetstine JR, Nottke A, Lan F, Huarte M, Smolikov S, Chen Z, Spooner E, Li E, Zhang G, Colaiacovo M, Shi Y: Reversal of histone lysine trimethylation by the JMJD2 family of histone demethylases. Cell 2006;125:467–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang M, Lygrisse K, Wang J: Role of MicroRNA in Osteoarthritis. Journal of arthritis 2017;6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cefalu CA: Theories and mechanisms of aging. Clinics in geriatric medicine 2011;27:491–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brunet A, Berger SL: Epigenetics of aging and aging-related disease. The journals of gerontology Series A, Biological sciences and medical sciences 2014;69 Suppl 1:S17–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greene MA, Loeser RF: Aging-related inflammation in osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis and cartilage 2015;23:1966–1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang Y, Karlsson R, Lampa E, Zhang Q, Hedman AK, Almgren M, Almqvist C, McRae AF, Marioni RE, Ingelsson E, Visscher PM, Deary IJ, Lind L, Morris T, Beck S, Pedersen NL, Hagg S: Epigenetic influences on aging: a longitudinal genome-wide methylation study in old Swedish twins. Epigenetics 2018;13:975–987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fraga MF, Ballestar E, Paz MF, Ropero S, Setien F, Ballestar ML, Heine-Suner D, Cigudosa JC, Urioste M, Benitez J, Boix-Chornet M, Sanchez-Aguilera A, Ling C, Carlsson E, Poulsen P, Vaag A, Stephan Z, Spector TD, Wu YZ, Plass C, Esteller M: Epigenetic differences arise during the lifetime of monozygotic twins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2005;102:10604–10609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matt SM, Allen JM, Lawson MA, Mailing LJ, Woods JA, Johnson RW: Butyrate and Dietary Soluble Fiber Improve Neuroinflammation Associated With Aging in Mice. Frontiers in immunology 2018;9:1832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chung HY, Sung B, Jung KJ, Zou Y, Yu BP: The molecular inflammatory process in aging. Antioxidants & redox signaling 2006;8:572–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nardini C, Moreau JF, Gensous N, Ravaioli F, Garagnani P, Bacalini MG: The epigenetics of inflammaging: The contribution of age-related heterochromatin loss and locus-specific remodelling and the modulation by environmental stimuli. Seminars in immunology 2018;40:49–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Franceschi C, Campisi J: Chronic inflammation (inflammaging) and its potential contribution to age-associated diseases. The journals of gerontology Series A, Biological sciences and medical sciences 2014;69 Suppl 1:S4–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang H, Skelly JD, Ayers DC, Song J: Age-dependent Changes in the Articular Cartilage and Subchondral Bone of C57BL/6 Mice after Surgical Destabilization of Medial Meniscus. Scientific reports 2017;7:42294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martin JA, Klingelhutz AJ, Moussavi-Harami F, Buckwalter JA: Effects of oxidative damage and telomerase activity on human articular cartilage chondrocyte senescence. The journals of gerontology Series A, Biological sciences and medical sciences 2004;59:324–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Philipot D, Guerit D, Platano D, Chuchana P, Olivotto E, Espinoza F, Dorandeu A, Pers YM, Piette J, Borzi RM, Jorgensen C, Noel D, Brondello JM: p16INK4a and its regulator miR-24 link senescence and chondrocyte terminal differentiation-associated matrix remodeling in osteoarthritis. Arthritis research & therapy 2014;16:R58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Verzijl N, DeGroot J, Ben ZC, Brau-Benjamin O, Maroudas A, Bank RA, Mizrahi J, Schalkwijk CG, Thorpe SR, Baynes JW, Bijlsma JW, Lafeber FP, TeKoppele JM: Crosslinking by advanced glycation end products increases the stiffness of the collagen network in human articular cartilage: a possible mechanism through which age is a risk factor for osteoarthritis. Arthritis and rheumatism 2002;46:114–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kapoor M, Martel-Pelletier J, Lajeunesse D, Pelletier JP, Fahmi H: Role of proinflammatory cytokines in the pathophysiology of osteoarthritis. Nature reviews Rheumatology 2011;7:33–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guerne PA, Zuraw BL, Vaughan JH, Carson DA, Lotz M: Synovium as a source of interleukin 6 in vitro. Contribution to local and systemic manifestations of arthritis. The Journal of clinical investigation 1989;83:585–592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Englund M, Guermazi A, Roemer FW, Aliabadi P, Yang M, Lewis CE, Torner J, Nevitt MC, Sack B, Felson DT: Meniscal tear in knees without surgery and the development of radiographic osteoarthritis among middle-aged and elderly persons: The Multicenter Osteoarthritis Study. Arthritis and rheumatism 2009;60:831–839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pauli C, Grogan SP, Patil S, Otsuki S, Hasegawa A, Koziol J, Lotz MK, D’Lima DD: Macroscopic and histopathologic analysis of human knee menisci in aging and osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis and cartilage 2011;19:1132–1141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hasegawa A, Otsuki S, Pauli C, Miyaki S, Patil S, Steklov N, Kinoshita M, Koziol J, D’Lima DD, Lotz MK: Anterior cruciate ligament changes in the human knee joint in aging and osteoarthritis. Arthritis and rheumatism 2012;64:696–704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Felson DT: Osteoarthritis as a disease of mechanics. Osteoarthritis and cartilage 2013;21:10–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Singh T, Newman AB: Inflammatory markers in population studies of aging. Ageing research reviews 2011;10:319–329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Loeser RF, Olex AL, McNulty MA, Carlson CS, Callahan MF, Ferguson CM, Chou J, Leng X, Fetrow JS: Microarray analysis reveals age-related differences in gene expression during the development of osteoarthritis in mice. Arthritis and rheumatism 2012;64:705–717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arda HE, Li L, Tsai J, Torre EA, Rosli Y, Peiris H, Spitale RC, Dai C, Gu X, Qu K, Wang P, Wang J, Grompe M, Scharfmann R, Snyder MS, Bottino R, Powers AC, Chang HY, Kim SK: Age-Dependent Pancreatic Gene Regulation Reveals Mechanisms Governing Human beta Cell Function. Cell metabolism 2016;23:909–920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hellio Le Graverand-Gastineau MP: OA clinical trials: current targets and trials for OA. Choosing molecular targets: what have we learned and where we are headed? Osteoarthritis and cartilage 2009;17:1393–1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Merrihew C, Kumar B, Heretis K, Rueger DC, Kuettner KE, Chubinskaya S: Alterations in endogenous osteogenic protein-1 with degeneration of human articular cartilage. Journal of orthopaedic research : official publication of the Orthopaedic Research Society 2003;21:899–907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Loeser RF, Im HJ, Richardson B, Lu Q, Chubinskaya S: Methylation of the OP-1 promoter: potential role in the age-related decline in OP-1 expression in cartilage. Osteoarthritis and cartilage 2009;17:513–517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tsuji K, Cox K, Gamer L, Graf D, Economides A, Rosen V: Conditional deletion of BMP7 from the limb skeleton does not affect bone formation or fracture repair. Journal of orthopaedic research : official publication of the Orthopaedic Research Society 2010;28:384–389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bi W, Deng JM, Zhang Z, Behringer RR, de Crombrugghe B: Sox9 is required for cartilage formation. Nature genetics 1999;22:85–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Henry SP, Liang S, Akdemir KC, de Crombrugghe B: The postnatal role of Sox9 in cartilage. Journal of bone and mineral research : the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research 2012;27:2511–2525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang M, Lu Q, Miller AH, Barnthouse NC, Wang J: Dynamic epigenetic mechanisms regulate age-dependent SOX9 expression in mouse articular cartilage. The international journal of biochemistry & cell biology 2016;72:125–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xanthoudakis S, Viola JP, Shaw KT, Luo C, Wallace JD, Bozza PT, Luk DC, Curran T, Rao A: An enhanced immune response in mice lacking the transcription factor NFAT1. Science (New York, NY) 1996;272:892–895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang J, Gardner BM, Lu Q, Rodova M, Woodbury BG, Yost JG, Roby KF, Pinson DM, Tawfik O, Anderson HC: Transcription factor Nfat1 deficiency causes osteoarthritis through dysfunction of adult articular chondrocytes. The Journal of pathology 2009;219:163–172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rodova M, Lu Q, Li Y, Woodbury BG, Crist JD, Gardner BM, Yost JG, Zhong XB, Anderson HC, Wang J: Nfat1 regulates adult articular chondrocyte function through its age-dependent expression mediated by epigenetic histone methylation. Journal of bone and mineral research : the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research 2011;26:1974–1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang M, Lu Q, Egan B, Zhong XB, Brandt K, Wang J: Epigenetically mediated spontaneous reduction of NFAT1 expression causes imbalanced metabolic activities of articular chondrocytes in aged mice. Osteoarthritis and cartilage 2016;24:1274–1283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Greenblatt MB, Ritter SY, Wright J, Tsang K, Hu D, Glimcher LH, Aliprantis AO: NFATc1 and NFATc2 repress spontaneous osteoarthritis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2013;110:19914–19919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rudolf R, Busch R, Patra AK, Muhammad K, Avots A, Andrau JC, Klein-Hessling S, Serfling E: Architecture and expression of the nfatc1 gene in lymphocytes. Frontiers in immunology 2014;5:21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhou B, Wu B, Tompkins KL, Boyer KL, Grindley JC, Baldwin HS: Characterization of Nfatc1 regulation identifies an enhancer required for gene expression that is specific to pro-valve endocardial cells in the developing heart. Development (Cambridge, England) 2005;132:1137–1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Caldwell KL, Wang J: Cell-based articular cartilage repair: the link between development and regeneration. Osteoarthritis and cartilage 2015;23:351–362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Makwana K, Patel SA, Velingkaar N, Ebron JS, Shukla GC, Kondratov R: Aging and calorie restriction regulate the expression of miR-125a-5p and its target genes Stat3, Casp2 and Stard13. Aging 2017;9:1825–1843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]