SUMMARY

Equine influenza virus (EIV) causes a highly contagious respiratory disease in equids, with confirmed outbreaks in Europe, America, North Africa, and Asia. Although China, Mongolia, and Japan have reported equine influenza outbreaks, Korea has not. Since 2011, we have conducted a routine surveillance programme to detect EIV at domestic stud farms, and isolated H3N8 EIV from horses showing respiratory disease symptoms. Here, we characterized the genetic and biological properties of this novel Korean H3N8 EIV isolate. This H3N8 EIV isolate belongs to the Florida sublineage clade 1 of the American H3N8 EIV lineage, and surprisingly, possessed a non-structural protein (NS) gene segment, where 23 bases of the NS1-encoding region were naturally truncated. Our preliminary biological data indicated that this truncation did not affect virus replication; its effect on biological and immunological properties of the virus will require further study.

Key words: Equine influenza virus, H3N8, NS1 truncation, South Korea

INTRODUCTION

Equine influenza virus (EIV) is a type A influenza virus of the family Orthomyxoviridae, causing rapidly spreading outbreaks of respiratory disease in equine species. Influenza A virus contains a single-stranded, negative-sense RNA genome, consisting of eight separate gene segments, including polymerase basic protein 2 (PB2), polymerase base 1 protein (PB1), polymerase acidic protein (PA), haemagglutinin (HA), nucleoprotein (NP), neuraminidase (NA), matrix protein (M), and non-structural protein (NS) gene segments, and is further classified by subtype on the basis of the two main surface glycoproteins: HA and NA [1]. To date, two subtypes of EIV (H7N7 and H3N8) have been isolated from horses; historically, a H7N7 virus (e.g. A/equine/Prague/56) emerged first in 1956 [2], and a H3N8 virus (e.g. A/equine/Miami/63) occurred in 1963 [3]. Of those, H3N8 EIV has been found to be continuously circulating and has evolved into two genetically and antigenically distinct lineages (Eurasian and American lineages) [4]. More specifically, the American lineage was further divided into three sublineages (Argentina, Kentucky, and Florida sublineages), and the Florida sublineage includes two representative clades; clades 1 and 2 [5], which contains A/equine/Sydney/2888-8/2007 [6] and A/equine/Hubei/6/2008 [7], respectively.

Influenza A virus can transmit from one species to another, and this characteristic of interspecies transmission causes multiple reassortant influenza viruses to emerge [8–10]; H3N8 EIV is not an exception. The H3N8 EIV was transmitted to racing greyhounds kept near infected horses in Florida in January 2004 [11], and this canine influenza that had originated from EIV spread to pet dogs, being the newly emerged H3N8 canine influenza in the USA [12].

Contemporary outbreaks of equine influenza have occurred recently in Japan and Australia, and were caused by EIV strains belonging to Florida sublineage clade 1, while clade 2 occurred in China [6, 7, 13]. However, EIV has not yet been isolated in South Korea, which is adjacent to those countries, although serological evidence of EIV infection of unvaccinated horses was reported by the Korean National Veterinary Research and Quarantine Service in 2010 [14]. Since 2011, we have performed equine influenza surveillance at domestic stud farms and successfully isolated an EIV strain from horses showing typical symptoms of respiratory disease. In this study, we genetically and biologically characterized the first EIV isolate from Korea.

METHODS

Virus isolation and titration

Nasal mucus was collected from both nostrils of 88 horses at domestic stud farms (Gyeonggi, South Korea), using conventional, short, sterile, cotton-tipped swabs, in a transport medium containing penicillin G (2 × 106 U/l), polymyxin B (2 × 106 U/l), gentamicin (250 mg/l), nystatin (0·5 × 106 U/l), ofloxacin HCl (60 mg/l), and sulphamethoxazole (0·2 g/l). The swab samples were centrifuged and stored at −80°C. After thawing, 100 μl of each sample was inoculated into 10-day-old embryonated chicken eggs. After 72 h incubation, the allantoic fluid was harvested and clarified by centrifugation at 1000 g for 20 min. The presence of influenza virus in the allantoic fluid was examined by adding an equal volume of 0·5% chicken red blood cells in phosphate buffered saline (PBS). Virus titres were determined by calculating 50% of egg infectious dose (EID50) in 10-day-old embryonated chicken eggs and 50% of tissue culture infectious dose (TCID50) in Madin–Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells according to the method of Reed & Muench [15, 16]. A control strain of H3N8 EIV (A/equine/Miami/01/1963; MA63) was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, USA).

Sequence analysis

Viral RNA was extracted from the allantoic fluid of the virus-inoculated eggs with the RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen Inc., USA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. One-step reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR) was employed to amplify the viral gene segments with the OneStep RT–PCR kit (Qiagen Inc.) and universal primer sets as described previously [17]. Briefly, reverse transcription was performed at 50°C for 30 min. Standard PCR was performed at 95°C for 15 min, at 94°C for 30 s, at 56°C for 30 s, and at 70°C for 2 min for 35 cycles; followed by a final elongation step at 72°C for 7 min. The amplified gene segments were purified with the QIAquick Gel Extraction kit (Qiagen Inc.) and commercially sequenced three times at Cosmogenetech Ltd (South Korea).

Genetic analysis

The full-length gene sequences of the virus were edited with the Lasergene sequence analysis software package version 5.0 (DNASTAR, USA) and aligned using CLUSTAL V [18]. The phylogenetic relationship was deduced using the neighbour-joining algorithm, and the evolution distances were analysed using the p-distance method in MEGA software version 5.0 [19]. The associated taxa were clustered together in a bootstrap test (1000 replicates) with a scale of 0·005 nucleotide changes per site [20]. Reference sequences were obtained from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov), and previously published accession numbers of the gene sequences used in this study are provided in Supplementary Table S1 (available online).

Growth kinetics

MDCK cells, cultured to confluence in 12-well plates, were infected with a 0·01 multiplicity of infection (MOI) of viruses diluted in infection medium [Minimum Essential Medium (MEM) supplemented with 0·3% bovine albumin (7·5 g/100 ml), 1% gentamicin (10 mg/ml), and 1 μg/ml of l−1-tosylamido-2-phenylethyl chloromethyl ketone (TPCK) trypsin] at 37°C for 1 h. After washing with PBS three times, the cells were incubated in the infection medium at 37°C. The supernatant was collected at 12, 24, 48, and 72 h post-infection, respectively, and virus titres were determined by calculating TCID50/ml. Three chicken embryos aged 7 and 11 days old were inoculated with a 0·001 MOI of viruses per incubation period, i.e. 24, 48 and 72 h. Allantoic fluid was harvested at the indicated time points, and checked for the presence of the virus in the fluid by adding an equal volume of 0·5% chicken red blood cells in PBS, and the pooled allantoic fluid was titrated by EID50/ml.

RESULTS

History of equine influenza outbreak and virus isolation

In July 2011, typical symptoms of respiratory disease, including severe runny nose, were observed in four of 88 horses, that recovered after a week, at a domestic stud farm in Gyeonggi Province, South Korea. All of the horses at this stud farm had been periodically vaccinated with a commercial equine influenza vaccine (Merial Ltd, USA), which was generated from two strains of EIV [A/equine/Kentucky/94 (H3N8) and A/equine/Newmarket/2/93 (H3N8)], On the assumption that the disease-causing agent would be EIV, based on the symptoms of disease, we attempted to isolate influenza virus from the nasal swabs of the sick horses using chicken embryos, and successfully isolated an influenza virus strain [A/equine/Kyonggi/SA01/2011 (KG11)]. The isolate was seen to be of the H3N8 subtype by sequence analysis and was further titrated: 1/32 of haemagglutination units when using chicken red blood cells, 106·75 EID50/ml in chicken embryos, and 105·63 TCID50/ml in MDCK cells.

Genetic and phylogenetic characteristics

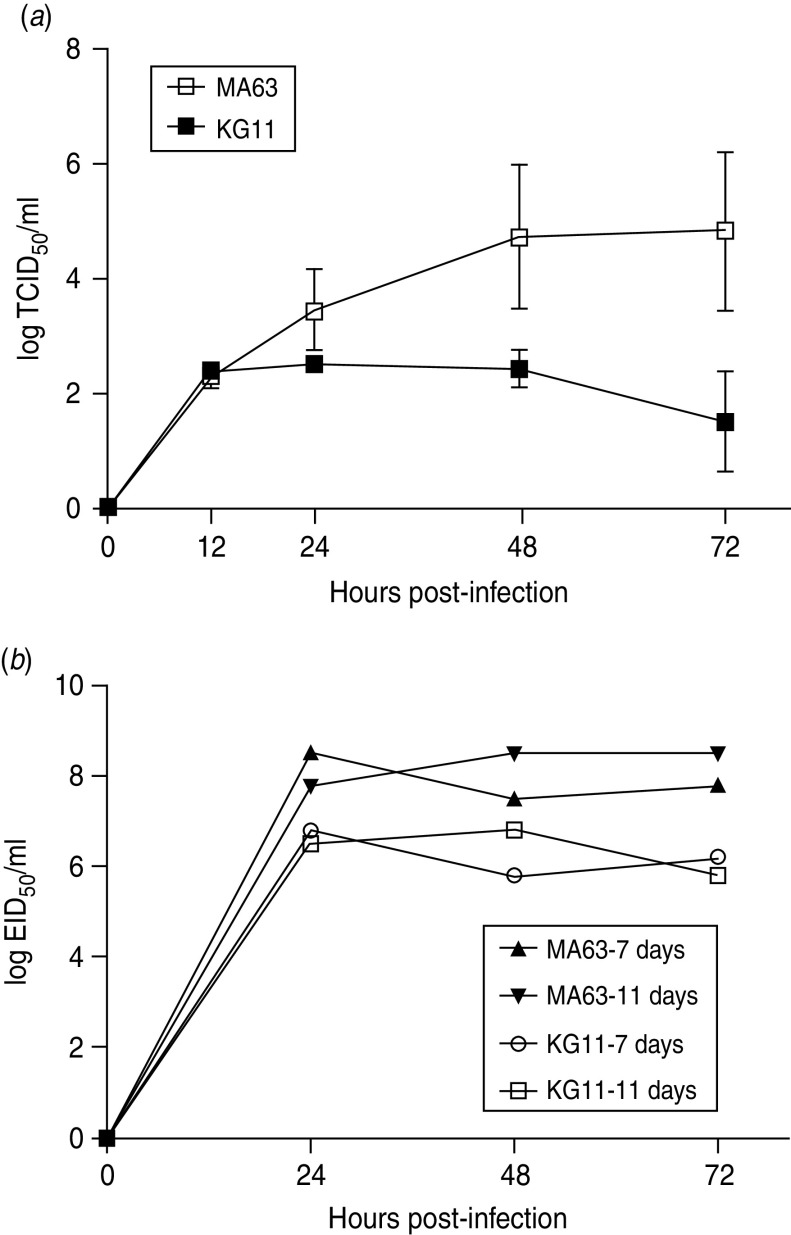

All eight gene segments (PB2, PB1, PA, HA, NP, NA, M, NS) of our H3N8 EIV isolate were sequenced, and the full-length nucleotide information was analysed using the basic alignment search tool (BLAST, http://blast.ncbi.nim.nih.gov/Blast.cgi). Genetic analysis indicated that all gene segments, except NS, were highly homologous (>99%) to those of H3N8 EIV strains isolated in Japan in 2007; NS showed a relatively low similarity (96%) with those of Japanese H3N8 EIV 2007 strains (GenBank accession numbers JX844143–JX844150). Surprisingly, the NS gene segment of our H3N8 EIV isolate was truncated by 23 bases (bases 327–349), with numbering beginning with the start codon (Fig. 1). The truncation was only observed in the gene coding for the NS1 protein, not in the NS2 open reading frame (bases 12–41 and 491–826 of the NS gene nucleotide) [21].

Fig. 1.

NS gene sequence alignment of H3N8 equine influenza viruses. Sequence numbers begin with the start codon. NS truncation of A/equine/Kyonggi/SA01/2011 is observed between bases 327 and 349.

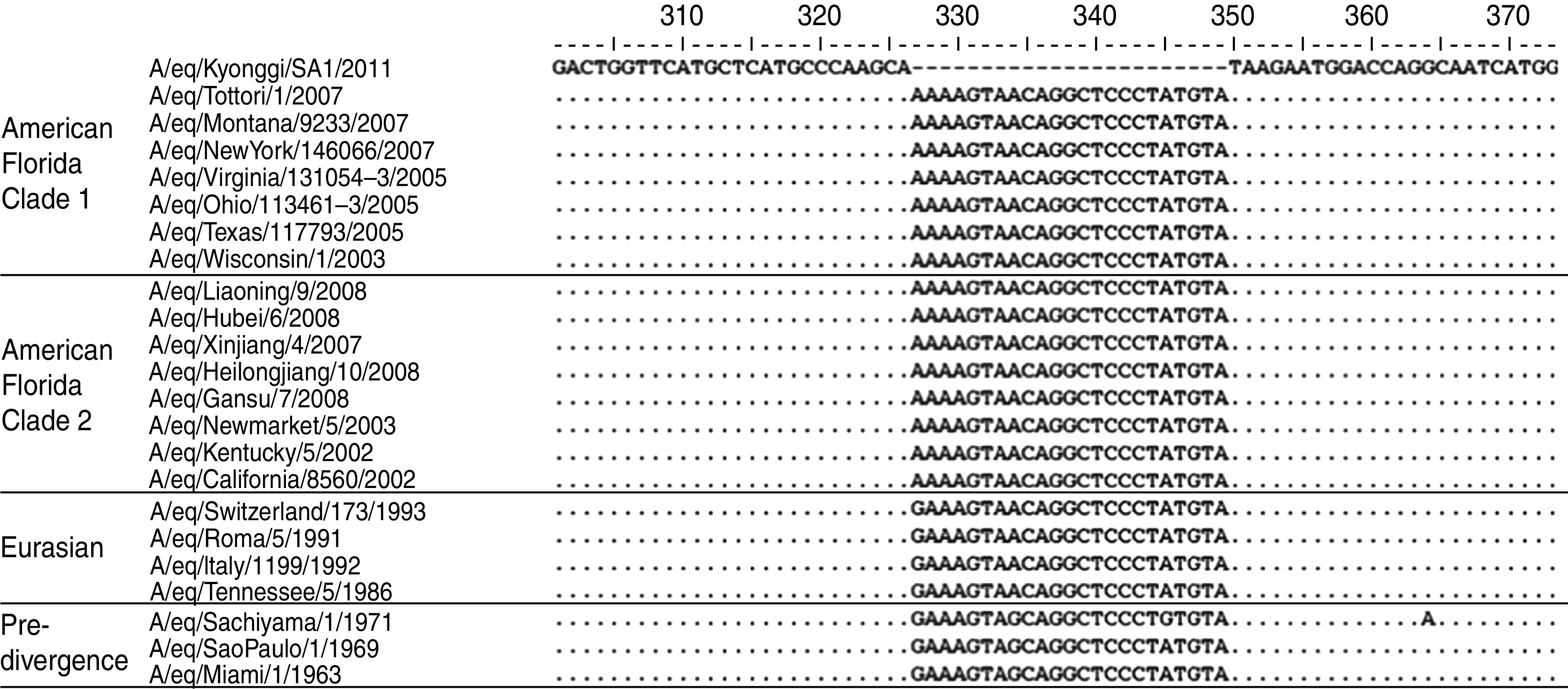

The full-length nucleotide sequences were used to construct phylogenetic trees in order to identify the origin and evolutionary relationships of our H3N8 EIV isolate. As shown in Figure 2, phylogenetic analysis revealed that the HA and NA genes clustered together with those of American, Australian, and Japanese EIV viruses belonging to the Florida sublineage clade 1. Similar phylogenetic topologies were also shown in the internal genes, including PB2, PB1, PA, NP, M, and NS. Overall, and in agreement with the results of the nucleotide sequence similarity analysis, our phylogenetic analysis indicated that the isolate is H3N8 equine influenza A virus belonging to the Florida sublineage clade 1, which belongs to the currently circulating Japanese H3N8 EIV.

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic relationships of the eight genes of the new isolate, A/equine/Kyonggi/SA01/2011 (H3N8) virus. Phylogenetic trees were constructed using the nucleotide sequences of the (a) HA, (b) NA, (c) PB2, (d) PB1, (e) PA, (f) NP, (g) M, and (h) NS genes from our isolate along with those of selected equine influenza A viruses available in GenBank (see Supplementary Table S1 for accession numbers). Analysis was based on the following nucleotides: HA1 (1–1693), NA (1–1408), PB2 (1–2280), PB1 (1–2274), PA (1–2151), NP (1–1497), M (1–982), NS (1–838). The phylograms were generated by neighbour-joining (NJ) analysis using MEGA v. 5 software with 1000 bootstrapping replicates. The NJ percentage bootstrap values for each node are shown in each tree. The viruses characterized in this study are indicated by diamonds (◆).

Growth characteristics

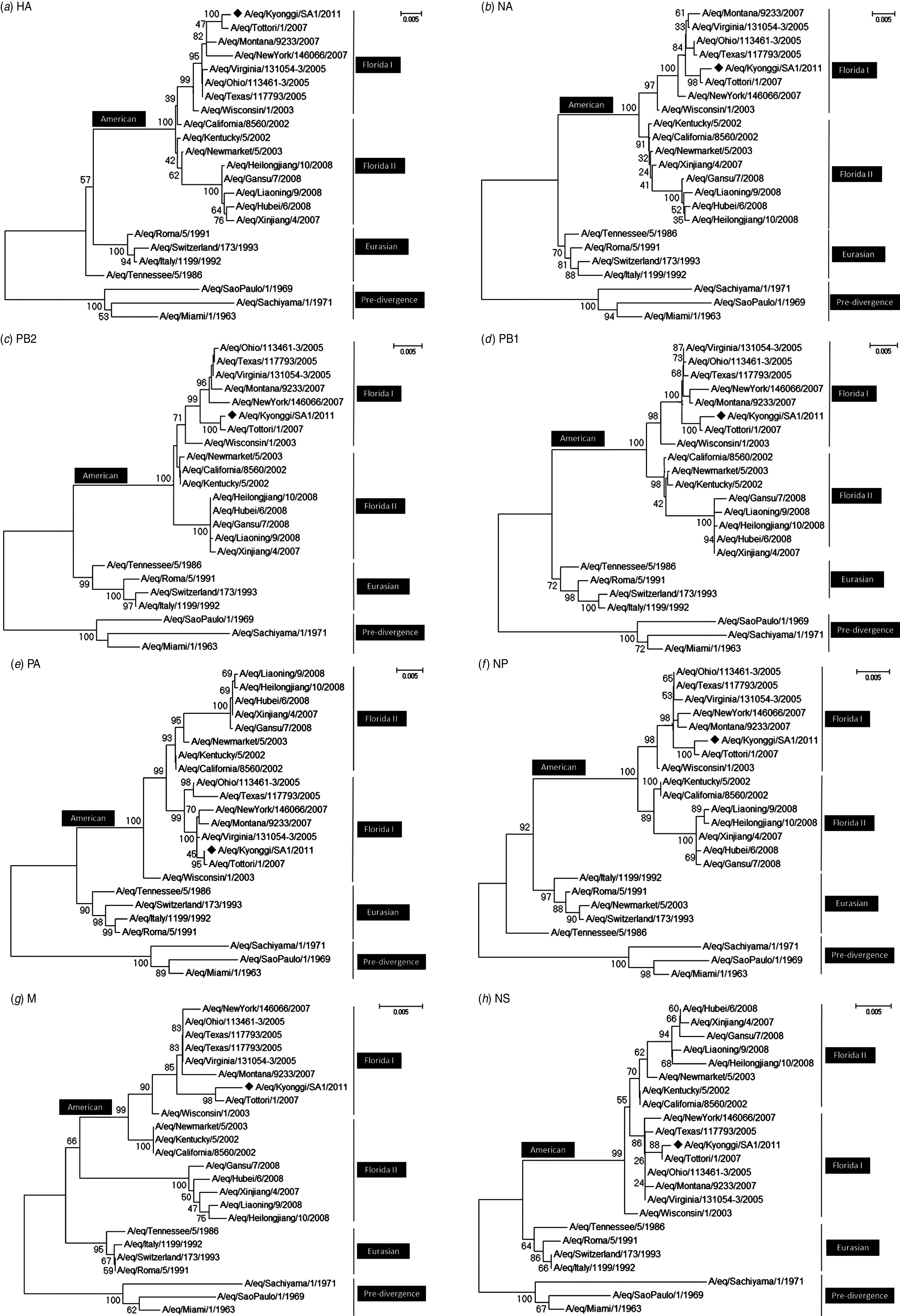

To examine viral replication of our novel H3N8 isolate (KG11), we observed its growth kinetics in MDCK cells (MDCK cells are reported to be an appropriate cell line for a wide variety of influenza A viruses [22]). Cells were infected with viruses at a MOI of 0·01, and the supernatants of infected cells were titrated at various times: 12, 24, 48, 72 h post-infection. KG11 showed a lower viral titre than MA63, and notable differences from 24 h post-infection. At 72 h post-infection, KG11 and MA63 had a TCID50 of 1·5 and 4·8, respectively (Fig. 3a). Furthermore, KG11 showed lower viral titre than MA63 in chicken embryos (Fig. 3b). The viruses were inoculated at a MOI of 0·001 into 7- and 11-day-old embryonated chicken eggs, which have immature interferon (IFN) systems and IFN-competent systems [23], respectively. KG11 showed lower titres than MA63, i.e. 1·7 log10EID50/ml in 7-day-old embryos and 1·9 log10 EID50/ml in 11-day-old embryos. However, each virus showed no difference in titre with respect to the age of the eggs.

Fig. 3.

Characterization of viral growth in MDCK cells and in chicken embryos. (a) MDCK cells were infected with 0·01 multiplicity of infection (MOI) of each virus. The mean viral titre (±s.d.) was determined by TCID50 assay at 12, 24, 48 and 72 h post-infection. (b) Each virus was inoculated with 0·001 MOI into embryonated chicken eggs aged 7 and 11 days old. At the indicated time points, allantoic fluid was harvested and titrated by EID50.

Discussion

In order to certify the conformity of current influenza vaccines with newly occurring viruses, it is necessary that vaccine strains of influenza virus are updated through continuous surveillance programmes, because the influenza A virus, including EIV, undergoes antigenic drift. This results in the emergence of new subtypes that could have different antigenicities from previously circulating viruses [24, 25]. In our study, we found that a recent EIV outbreak occurred in a vaccinated stud farm in Korea and revealed that the virus belonged to the American Florida sub-lineage clade 1. This sub-lineage of H3N8 EIV was transmitted to racing greyhounds and has spread to the general dog population in the USA since as early as 1999 [26]. Co-circulation of H3N8 viruses [H3N8 EIV and enzootic H3N8 canine influenza virus (CIV)] in dogs caused the emergence of H3N8 CIVs, which differ from enzootic H3N8 CIVs in North America [27]. However, in East Asia, i.e. South Korea and China, H3N2 CIV is prevalent; this CIV originated from avian influenza A virus [28–30] and transmission of H3N8 EIV to dogs has not yet been reported. Recently, H3N1 CIV, representing reassortment between pandemic H1N1 virus and the H3N2 CIV, was isolated from a single pet dog [31]. Thus, this raises a concern that co-circulation of Korean EIV and the H3N1 CIV could occur in dogs, which would generate a new triple reassortant virus of equine, canine, and human influenza virus.

Our Korean H3N8 EIV isolate contained a naturally truncated NS gene segment, resulting in a shortened gene coding for the NS1 protein; however, this truncation did not overlap with the open reading frame of NS2. The NS1 protein is generally believed to enhance the efficacy of viral replication suppressing the IFN system in host cells [32], and an influenza virus with a truncated NS gene coding for the NS1 protein rarely replicates in an IFN-competent system [33–35]. Interestingly, we found that our H3N8 EIV isolate containing the truncated NS gene segment replicated efficiently in chicken embryos, and showed comparable viral titre for IFN-competent and immature IFN systems. At present, it is not clear whether the truncated NS gene of our H3N8 EIV isolate would affect the virulence of the strain; further studies are needed to address this issue directly.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S095026881300143X.

click here to view supplementary material

Supplementary information supplied by authors.

DECLARATION OF INTEREST

None.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by grants of the TEPIK (Transgovernmental Enterprise for Pandemic Influenza in Korea), which is part of Korea Healthcare Technology R&D Project by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (Grant no. A103001), the Bio-industry Technology Development Programme by the Ministry for Food, Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries, Republic of Korea (Grant no. 111041-2), and a National Agenda Project by the Korea Research Council of Fundamental Science & Technology and the KRIBB Initiative programme (KGM0821113).

References

- 1.Fouchier RA, et al. Characterization of a novel influenza A virus hemagglutinin subtype (H16) obtained from black-headed gulls. Journal of Virology 2005; 79: 2814–2822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sovinova O, et al. Isolation of a virus causing respiratory disease in horses. Acta Virologica 1958; 2: 52–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Waddell GH, Teigland MB, Sigel MM. A new influenza virus associated with equine respiratory disease. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 1963; 143: 587–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lai AC, et al. Diverged evolution of recent equine-2 influenza (H3N8) viruses in the Western Hemisphere. Archives of Virology 2001; 146: 1063–1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.OIE. Conclusions and recommendations from the Expert Surveillance Panel on Equine Influenza Vaccines. Bulletin de l'Office International des Epizooties 2008; 2: 42–54. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Watson J, et al. Isolation and characterisation of an H3N8 equine influenza virus in Australia, 2007. Australian Veterinary Journal 2011; 89 (Suppl. 1): 35–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Qi T, et al. Genetic evolution of equine influenza viruses isolated in China. Archives of Virology 2010; 155: 1425–1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Webster RG, Sharp GB, Claas EC. Interspecies transmission of influenza viruses. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 1995; 152: S25–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murphy BR, et al. Reassortant virus derived from avian and human influenza A viruses is attenuated and immunogenic in monkeys. Science 1982; 218: 1330–1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ramakrishnan MA, et al. Triple reassortant swine influenza A (H3N2) virus in waterfowl. Emerging Infectious Diseases 2010; 16: 728–730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 11.Crawford PC, et al. Transmission of equine influenza virus to dogs. Science 2005; 310: 482–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Payungporn S, et al. Influenza A virus (H3N8) in dogs with respiratory disease, Florida. Emerging Infectious Diseases 2008; 14: 902–908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ito M, et al. Genetic analyses of an H3N8 Influenza virus isolate, causative strain of the outbreak of equine influenza at the Kanazawa Racecourse in Japan in 2007. Journal of Veterinary Medical Science 2008; 70: 899–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Choi E, et al. Serological survey on equine influenza viruses in Korea. Journal of Preventive Veterinary Medicine 2010; 34: 45–51. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kawaoka Y, Neumann G. Influenza Virus: Methods and Protocols. New York: Humana Press, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reed LJ, Muench H. A simple method of estimating fifty per cent endpoints. American Journal of Hygiene 1938; 27: 493–497. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoffmann E, et al. Universal primer set for the full-length amplification of all influenza A viruses. Archives of Virology 2001; 146: 2275–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Higgins DG, Bleasbly AJ, Fuchs R. CLUSTAL V: improved software for multiple sequence alignment. Computer Applications in the Biosciences 1992; 8: 189–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tamura K, et al. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Molecular Biology and Evolution 2011; 28: 2731–2739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Felsenstein J. Confidence limits on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution 1985; 39: 783–791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lamb RA, Lai CJ. Sequence of interrupted and uninterrupted mRNAs and cloned DNA coding for the two overlapping nonstructural proteins of influenza virus. Cell 1980; 21: 475–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tobita K, et al. Plaque assay and primary isolation of influenza A viruses in an established line of canine kidney cells (MDCK) in the presence of trypsin. Medical Microbiology and Immunology 1975; 162: 9–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sekellick MJ, Biggers WJ, Marcus PI. Development of the interferon system. I. In chicken cells development in ovo continues on time in vitro. In Vitro Cellular & Developmental Biology 1990; 26: 997–1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Webster RG, et al. The mechanism of antigenic drift in influenza viruses: analysis of Hong Kong (H3N2) variants with monoclonal antibodies to the hemagglutinin molecule. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1980; 354: 142–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lewis NS, et al. Antigenic and genetic evolution of equine influenza A (H3N8) virus from 1968 to 2007. Journal of Virology 2011; 85: 12742–12749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Anderson TC, et al. Serological evidence of H3N8 canine influenza-like virus circulation in USA dogs prior to 2004. Veterinary Journal 2012; 191: 312–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rivailler P, et al. Evolution of canine and equine influenza (H3N8) viruses co-circulating between 2005 and 2008. Virology 2010; 408: 71–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee C, et al. A serological survey of avian origin canine H3N2 influenza virus in dogs in Korea. Veterinary Microbiology 2009; 137: 359–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Park SJ, et al. Complete genome sequence of an avian-origin H3N2 canine influenza virus isolated from dogs in South Korea. Journal of Virology 2012; 86: 9548–9549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Song D, et al. Experimental infection of dogs with avian-origin canine influenza A virus (H3N2). Emerging Infectious Diseases 2009; 15: 56–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Song D, et al. A novel reassortant canine H3N1 influenza virus between pandemic H1N1 and canine H3N2 influenza viruses in Korea. Journal of General Virology 2012; 93: 551–554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shors T. Understanding Viruses, 1st edn. USA: Jones and Bartlett, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Garcia-Sastre A, et al. Influenza A virus lacking the NS1 gene replicates in interferon-deficient systems. Virology 1998; 252: 324–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Talon J, et al. Activation of interferon regulatory factor 3 is inhibited by the influenza A virus NS1 protein. Journal of Virology 2000; 74: 7989–7996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang X, et al. Influenza A virus NS1 protein prevents activation of NF-kappaB and induction of alpha/beta interferon. Journal of Virology 2000; 74: 11566–11573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S095026881300143X.

click here to view supplementary material

Supplementary information supplied by authors.