INTRODUCTION

Physician burnout is a global healthcare crisis which has been compounded by the recent coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Drivers of physician burnout include excessive workloads, inefficient work environments, lack of autonomy, work-home conflicts, and lack of organizational support. The consequences of physician burnout are great, with impact on patient care, physician health and engagement, and healthcare systems and organizations (1). Radiologists report higher levels of burnout than physicians in many other specialties (2,3). Burnout among radiologists is seen at all career levels, from trainees to department chairs (4, 5, 6). In a study conducted by the Association of American Medical Colleges between 2016 and 2018, only 28% of all clinical faculty, and 31% of radiologists reported that they enjoyed their work (6). By early 2020, when COVID-19 cases reached hospitals and clinics in the US, physician burnout rates were already at epidemic levels with nearly 50% of those surveyed reporting symptoms of burnout (7). The pandemic brought unprecedented challenges to an already stressed and burned-out healthcare workforce (8,9). The cost of this pandemic to our healthcare system and to our communities has been tremendous. In addition to the lives lost to this virus, we have realized many other losses throughout this crisis. We have experienced loss of jobs, loss of opportunities, loss of connection with loved ones, loss of hope, and for many, loss of joy in our work as healthcare providers. Recovering joy in our work during the greatest health care crisis many of us have ever seen is critical to our ability to weather this storm and those that follow. It is going to require collective action and it is going to take P.R.A.C.T.I.C.E. We are going to examine how Purpose, Reflection, Appreciation, Connection, Time, Inclusion, Choosing Wisely, and Embracing change can help us recover and maintain joy in our work.

PURPOSE: Meaningful work

“May I always act so as to preserve the finest traditions of my calling and may I long experience the joy of healing those who seek my help.” — excerpt from the Hippocratic Oath (10).

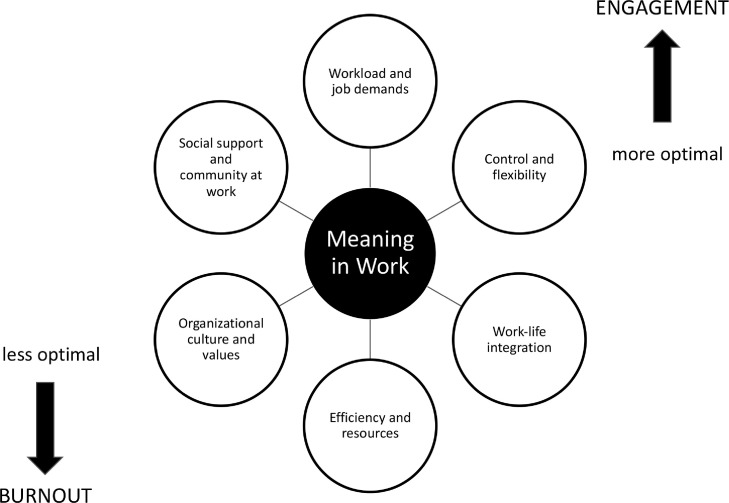

For many of us, one of the earliest memories we have of our medical career involved the donning of our white coats and recitation of the Hippocratic Oath alongside our new classmates and future colleagues. The enthusiasm and eagerness we felt in those early moments, mirrored the sentiments of our personal statements filled with excitement and determination to answer the call to medicine. As we travel down our career path and face the inevitable challenges, setbacks, and crises, these early sentiments are easily forgotten (11). Recent studies have shown that physicians who experience a greater degree of burnout are less likely to identify with medicine as a calling (12). Revisiting the intrinsic factors that motivated us to become physicians can help us become more resilient and reclaim the joy in our practice. Finding meaning in our daily work is a key element to physician engagement and a protective strategy to mitigate burnout (13). Shanafelt et al have placed meaningful work at the center of their driver dimensions model for physician burnout and organizational change (Fig 1 ) (14). Improving our connection to the value and meaning in our work requires examination of our daily practice. Physicians who spend <20% of their time at work on activities that they found personally meaningful were almost three times more likely to experience burnout. We must prioritize work that aligns with our passions and values throughout our careers (15,16). We must take an active approach to defining and re-defining what meaningful work looks like and encourage and support others in doing the same. It is through identifying and prioritizing that which drives us and gives us purpose, that we may discover more joy in medicine.

Figure 1.

Shanafelt's driver dimensions of burnout and organizational change.

REFLECTION: Looking back

Reflective practices have been defined as “those intellectual and affective activities in which individuals engage to explore their experiences in order to lead to a new understanding and appreciation” (17,18). Interventions focused on reflective practice have shown to improve physician well-being (19,20). Reflecting on what we have been through collectively and as individuals is crucial to our ability to learn from what we have endured and celebrate what we have accomplished. Moments of reflection aide in examining a microlevel environment, such as one's immediate work unit (i.e., reading room or division) or macrolevel environment, such as an organization or institution or even a larger world view. It is important that we welcome and honor all feelings that arise from difficult experiences without judgement, including grief, anger, frustration, loss, hopelessness, relief, and gratitude. Mindfulness practices, such as meditation, breathing exercises, or journaling allow the space and time to reflect on what we have experienced. Reflecting on the struggles that we faced in the past offers us a chance to learn from how we responded and to better understand and appreciate the unique qualities that we possess.

APPRECIATION: Appreciative inquiry and gratitude practice

Appreciative inquiry is a “strengths-based approach to identify “what is going well” with a situation” and use this information to envision positive change (21). Instead of asking or dwelling on “what is going wrong,” ask and focus on “what is going well.” These questions seek to identify strengths that individuals or organizations can build upon to achieve intended goals (Table 1 ). Additionally, perceived weaknesses can be reframed as strengths to be developed (21). This small change in mindset can have a notable impact on internal motivation. In the context of perceived weaknesses, a key word to consider is “yet.” Contrast the statement “I can't engage my audience effectively” with “I can't engage my audience effectively yet.” The former portrays a fixed mindset, whereas the latter portrays a growth mindset with a desire to achieve the goal of how to engage an audience more effectively.

Table 1.

The “5-D model” of Appreciative Inquiry and Building on Current Strengths to Achieve Goals Includes the Following Phases (17)

| 1. Definition – “is this worth doing?” |

| 2. Discovery – “what is working well?” |

| 3. Dream – “what would the ideal future situation be like?” |

| 4. Design – “what do we need to do to realize that future?” |

| 5. Destiny or Deliver – “what needs to be done to ensure that the changes continue?” |

Appreciative inquiry, including reflecting on “what is going well,” cultivates gratitude. Positive life experiences, such as receiving an award or recognition, also cultivate gratitude. It can be difficult to cultivate a sense of gratitude during negative or challenging life experiences. Noticing and appreciating things we might otherwise take for granted, such as having a job, good health, food on the table, our family, and/or the beauty of nature, cultivate not only gratitude, but also well-being and joy. Gratitude practices take this one step further and include intentional actions that express gratitude toward ourselves or others (22). In a study, investigating gratitude and subjective well-being, the participants who practiced gratitude exercises showed higher levels of positive affect and well-being (18). Examples include saying thank you, writing 1-3 things we are grateful for in a daily gratitude journal, paying it forward with acts of kindness or volunteerism, and/or sending thank you cards, emails, or texts.

CONNECTION: The value of social connection

“Social connection is an umbrella term that refers to the ways in which one can connect to others physically, behaviorally, cognitively, and emotionally” (23). This connection can provide structural support (via presence of relationships in our lives), functional support (via the resources or functions these relationships do or could potentially provide) and quality support (encompassing the positive and negative emotional part of our relationships.)

The science of human connection has been well studied. Our need to connect with others has been described as “fundamental as our need for food and water” (24). Shanafelt et al includes lack of social support and community as one of the key drivers of physician burnout (25). Cultivating a sense of belonging is an important intrinsic motivator and key component of our well-being. Fishman et al propose three categories of activities that have the potential to enrich the radiology workplace community through connection: socializing, radiologist volunteer work, and radiologist participation in workplace operations (26). Connection builds community, combats feelings of isolation and depression, and mitigates burnout.

TIME: Integrating work and life

In modern medicine, there is increasing time pressure on both academic and private practice physicians, making it more difficult for physicians to accomplish all that they want in both their professional and personal lives. The 24/7 nature of clerical and administrative tasks, coupled with the ubiquity of the electronic health record, has further blurred the boundary between “work” and “life” (27, 28, 29). Previously, this was conceptualized as work-life balance suggesting that there was a tradeoff between the demands of work and life which could be balanced. More recently, however, given the ubiquity of work in people's lives, the concept has shifted towards achieving a harmonious integration of work and life, a concept known as work-life integration (30).

Making time for leisure or recreational activities is a critical component of work-life integration and is a learned skill that takes practice and dedication to perfect. This critical act of self-care and has been likened to “securing our own oxygen mask” before helping others (1). Strategies to achieve better work-life integration are multifactorial and require individual and systemic changes (31). Potential ways individuals can move toward better integration include outsourcing and delegating tasks and replacing perfectionism in all areas of life with an acceptance of being “good enough.” In addition, setting healthier boundaries for designated work time, such as not working during vacation days or limiting off-hours work is an important aspect maintaining better work-life integration (32).

INCLUSION: A place for everyone

We spend many hours at work and may even spend more of our waking hours with our work colleagues than our family members. Thus, having collegial and inclusive work relationships is important for our day-to-day well-being and mental health. Relationships based on mutual respect and trust are important not only for the daily micro-environment, such as with members of your division, but also important with leaders at a departmental level and even an institutional level. As human beings, we need to feel a sense of belonging that is all encompassing and includes feeling seen, accepted, valued, appreciated, and supported (33). We feel joy and deep satisfaction in our work when there is alignment of our goals with the mission of our institution and the work environment is positive. However, this feeling of belonging in academic medicine is often a privilege that is not universally experienced, particularly for individuals in nondominant groups (34).

It is well established that having a diverse workforce is imperative to the success of organizations because diversity in thought, perspectives and experiences leads to more creative ideas and innovative solutions (35). In the Diversity 3.0 Framework from the Association of American Medical Colleges, creating a culture and climate of inclusion begins with making diversity a core value (36). The framework calls on the engagement from all levels of “human capital” within the organization, from administrators to faculty to students to learn, practice and create policies that encourage mutual respect and belonging (36).

At the institutional level, policies are a testament to the institution's culture of inclusion, such as nongendered bathrooms to prevent discrimination against transgender or nonbinary individuals (37). Creating policies that promote diversity and inclusion creates a safe space for employees to present their authentic selves at work without fear of discrimination (37). The sense of belonging occurs when people feel connected to others because they have meaningful relationships with their colleagues. We as individuals must examine our own biases and unintended microaggressions to become aware of how our words and actions are preventing others from feeling included (38).

CHOOSING CAREFULLY: Setting your intention

Choices are ubiquitous in our personal and professional lives. The ability to make choices with intention and purpose is a skill that we need throughout our careers, not only for personal success, but also for sustainability. Personal agency, autonomy, and control are considered drivers of well-being (39). For instance, a survey of nearly 250 academic radiologists revealed that lack of autonomy was associated with high rates of burnout (40). We must make our choices carefully and with intention.

Making choices can be difficult, particularly if a radiologist is trying to cultivate a scholarly niche or foster administrative duties while attending to clinical work. Prioritizing activities means being strategic about what one says “yes” and “no” to since time is a limited resource. A mentor may give advice to a mentee about which choices might be beneficial to their career. A coach may help a radiologist develop insight and self-reflection to guide personal and professions decision making (41).

At an organizational level, businesses and institutions use mission statements to focus and guide their efforts. A personal mission statement can be the foundation upon which one optimizes their approach to their personal strategic planning. An effective personal mission statement should inspire its creator and affirm their intrinsic motivation; in essence, a personal mission statement can serve as our internal compass reminding us of our true north, our core values, helping to inform the choices we make. Li et al describe an effective seven-step framework for crafting a personal mission statement aligned with the acronym INSPIRE (42). In short, the process includes identifying our core values; setting our vision, planning how we will achieve our vision and identifying specific activities that align with our mission. It is important to recognize that our personal goals and visions will evolve over time, and we must revise our personal missions accordingly.

EMBRACING CHANGE: Crisis as a catalyst for change

The response of educators and scholars to the COVID pandemic has been summarized by three emerging themes, caring, courage and curiosity (43). It requires courage to discontinue familiar methods and theories and to challenge the status quo. As physicians we used our curiosity and creativity to rethink how we care for our patients and design new ways of teaching our students and trainees. The innovative solutions we have created, have served in many instances as a catalyst for positive change. This is especially true regarding medical education. The logistical changes in radiologist staffing under COVID-19 social distancing policies resulted in new opportunities for remote work and concurrently, remote teaching. Radiology trainees adapted to remote lecturing and video conferencing formats, and radiology curricula and teaching activities had to be revised, updated, and reimagined into online or hybrid formats. The positive side of these changes was increased learner and faculty participation in many of these sessions. The ability to attend or host lectures and inter-disciplinary conferences virtually, made participation by faculty and learners at different locations possible. Virtual “visiting” professorships further enhanced remote learning and students on virtual rotations were able to experience radiology at distant locations without travel and relocation costs (44, 45, 46). As we continue to navigate our way out of this crisis, we need to ask ourselves which of our adaptive solutions we would like to take with us. Many of the solutions like expanded teleradiology practices, virtual teaching abilities, and greater collaborative efforts in the workplace served to help us survive during the crisis and may help us thrive going forward.

CONCLUSION

Recapturing joy in medicine has been described as the “antidote” to burnout (11,47). Nurturing the intrinsic factors that drew us to medicine and rediscovering purpose and meaning in our work, combined with reflection, appreciation, and connection to and inclusion of others helps us realign with the humanism that is at the core of medicine. Taking time for ourselves outside of work and making careful choices with intention create space for more effective integration of work and personal life. These elements help build resilience and enhance our ability to embrace change and see the challenges we face as opportunities for growth. It will take P.R.A.C.T.I.C.E, but we will be able to recover and sustain joy in our practice of medicine.

REFERENCES

- 1.West CP, Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD. Physician burnout: contributors, consequences and solutions. J Intern Med. 2018;283(6):516–529. doi: 10.1111/joim.12752. 10.111/joim.12752. Epub 2018 Mar 44. PMID:29055159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Giess CS, Ip IK, Gupte A, et al. Self-reported burnout: comparison of radiologists to nonradiologist peers at a Large Academic Medical Center. Acad Radiol. 2022;29(2):277–283. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2020.10.013. Epub 2020 Nov 7. PMID: 33172814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shanafelt TD, West CP, Sinsky C, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life integration in physicians and the general US working population between 2011 and 2017. Mayo Clin Proc. 2019;94(9):1681–1694. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2018.10.023. Epub 2019 Feb 22. PMID: 30803733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perry H, Naud S, Fishman MDC, et al. Longitudinal resilience and burnout in radiology Residents. J Am Coll Radiol. 2021;18(5):639–646. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2021.01.022. Epub 2021 Feb 26. PMID: 33640338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chetlen AL, Chan TL, Ballard DH, et al. Addressing Burnout in Radiologists. Acad Radiol. 2019;26(4):526–533. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2018.07.001. Epub 2018 Jul 31. PMID: 30711406; PMCID: PMC6530597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ganeshan D, Wei W, Yang W. Burnout in chairs of academic radiology departments in the United States. Acad Radiol. 2019;26(10):1378–1384. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2018.12.006. Epub 2019 Jan 11. PMID: 30638976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.AAMC Burnout among US medical school faculty. February 2019 analysis in brief V19 N1. Available at: https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/analysis-brief/report/burnout-among-us-medical-school-faculty. Accessed March 2022.

- 8.Yates SW. Physician stress and burnout. Am J Med. 2020;133(2):160–164. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2019.08.034. Epub 2019 Sep 11. PMID: 31520624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smallwood N, Pascoe A, Karimi L, et al. Moral distress and perceived community views are associated with mental health symptoms in frontline health workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(16):8723. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18168723. PMID: 34444469; PMCID: PMC8392524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Preti E, Di Mattei V, Perego G, et al. The psychological impact of epidemic and pandemic outbreaks on healthcare workers: rapid review of the evidence. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2020;22(8):43. doi: 10.1007/s11920-020-01166-z. PMID: 32651717; PMCID: PMC7350408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miles SH. Oxford University Press; Oxford; New York: 2004. The hippocratic oath and the ethics of medicine. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grimes PE. Physician burnout or joy: rediscovering the rewards of a life in medicine. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2019;6(1):34–36. doi: 10.1016/j.ijwd.2019.12.001. PMID: 32042882; PMCID: PMC6997840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jager AJ, Tutty MA, Kao AC. Association between physician burnout and identification with medicine as a calling. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92(3):415–422. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.11.012. Epub 2017 Feb 8. PMID: 28189341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Restauri N, Nyberg E, Clark T. Cultivating meaningful work in healthcare: a paradigm and practice. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 2019;48(3):193–195. doi: 10.1067/j.cpradiol.2018.12.002. Epub 2018 Dec 8. PMID: 30638757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shanafelt TD, Noseworthy JH. Executive leadership and physician well-being: nine organizational strategies to promote engagement and reduce burnout. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92(1):129–146. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.10.004. Epub 2016 Nov 18. PMID: 27871627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Serwint JR, Stewart MT. Cultivating the joy of medicine: a focus on intrinsic factors and the meaning of our work. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2019;49(12) doi: 10.1016/j.cppeds.2019.100665. Epub 2019 Sep 30. PMID: 31582295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shanafelt TD, West CP, Sloan JA, et al. Career fit and burnout among academic faculty. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(10):990–995. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.70. PMID: 19468093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lutz G, Scheffer C, Edelhaeuser F, et al. A reflective practice intervention for professional development, reduced stress and improved patient care–a qualitative developmental evaluation. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;92(3):337–345. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2013.03.020. Epub 2013 May 1. PMID: 23642894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koshy K, Limb C, Gundogan B, et al. Reflective practice in health care and how to reflect effectively. Int J Surg Oncol (N Y) 2017;2(6):e20. doi: 10.1097/IJ9.0000000000000020. Epub 2017 Jun 15. PMID: 29177215; PMCID: PMC5673148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rabow MW, McPhee SJ. Doctoring to Heal: fostering well-being among physicians through personal reflection. West J Med. 2001;174(1):66–69. doi: 10.1136/ewjm.174.1.66. PMID: 11154679; PMCID: PMC1157069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hunt SL. Reflective debrief and the social space: offload, refuel, and stay on course. Clin Radiol. 2020;75(4):265–270. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2019.12.012. Epub 2020 Jan 25. PMID: 31992456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sandars J, Murdoch-Eaton D. Appreciative inquiry in medical education. Med Teach. 2017;39(2):123–127. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2017.1245852. Epub 2016 Nov 17. PMID: 27852144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Emmons RA, McCullough ME. Counting blessings versus burdens: an experimental investigation of gratitude and subjective well-being in daily life. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2003;84(2):377–389. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.84.2.377. PMID: 12585811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holt-Lunstad J. Fostering social connection in the workplace. Am J Health Promot. 2018;32(5):1307–1312. doi: 10.1177/0890117118776735a. PMID: 29972035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dinnen M (2020) The importance of human connection in remote work. Workhuman. Available at: https://www.workhuman.com/resources/globoforce-blog/the-importance-of-human-connection-in-remote-work Accessed March 2022.

- 26.Shanafelt TD, Noseworthy JH. executive leadership and physician well-being: nine organizational strategies to promote engagement and reduce burnout. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92(1):129–146. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.10.004. Epub 2016 Nov 18. PMID: 27871627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fishman MDC, Mehta TS, Siewert B, et al. The road to wellness: engagement strategies to help radiologists achieve joy at work. Radiographics. 2018;38(6):1651–1664. doi: 10.1148/rg.2018180030. PMID: 30303794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Overhage JM, McCallie D., Jr. Physician time spent using the electronic health record during outpatient encounters: a descriptive study. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172(3):169–174. doi: 10.7326/M18-3684. Epub 2020 Jan 14. Erratum in: Ann Intern Med. 2020 Oct 6;173(7):596. PMID: 31931523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peccoralo LA, Kaplan CA, Pietrzak RH, et al. The impact of time spent on the electronic health record after work and of clerical work on burnout among clinical faculty. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2021;28(5):938–947. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocaa349. PMID: 33550392; PMCID: PMC8068423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Melnick ER, Sinsky CA, Dyrbye LN, et al. Association of perceived electronic health record usability with patient interactions and work-life integration among US physicians. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(6) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.7374. PMID: 32568397; PMCID: PMC7309439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Karakash S, Solone M, Chavez J, et al. Physician work-life integration: challenges and strategies for improvement. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2019;62(3):455–465. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0000000000000442. PMID: 30950862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tawfik DS, Shanafelt TD, Dyrbye LN, et al. Personal and professional factors associated with work-life integration among US physicians. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(5) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.11575. PMID: 34042994; PMCID: PMC8160595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zucker R Help your team achieve work-life balance- even when you can't. Harvard business review. 2017. Available at: https://hbr.org/2017/08/help-your-team-achieve-work-life-balance-even-when-you-cant Accessed March 2022.

- 34.Baumeister RF, Leary MR. The need to belong: desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychol Bull. 1995;117:497–529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roberts LW Belonging, respectful inclusion, and diversity in medical education, Acad Med: 2020;95 (5) 661-664 doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003215 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Bourke J, Smith C, Stockton H, Wakefield N. Deloitte University Press; 2014. From diversity to inclusion: move from compliance to diversity as a business strategy.http://www.orgwise.ca/sites/osi.ocasi.org.stage/files/Fom%20Diversity%20to%20Inclusion_1.pdf Available at: Accessed March 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nivet MA, Castillo-Page L, Schoolcraft Conrad S. A diversity and inclusion framework for medical education. Acad Med. 2016;91(7):1031. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001120. PMID: 26862838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fallon N A culture of inclusion: promoting workplace diversity and belonging. 2021. Available at: https://www.businessnewsdaily.com/10055-create-inclusive-workplace-culture.html Accessed March 2022.

- 39.Volini E Belonging. From comfort to connection to contribution. 2020. Deloitte Development LLC. New York, NY. Available at: https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/insights/focus/human-capital-trends/2020/creating-a-culture-of-belonging.html Accessed March 2022.

- 40.Lomas T. Positive work: a multidimensional overview and analysis of work-related drivers of wellbeing. Int J Appl Posit Psychol. 2019;3(1-3) doi: 10.1007/s41042-019-00016-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gowda V, Jordan SG, Oliveria A et al. Support from within: coaching to enhance radiologist well-being and practice. Acad Rad. Published online Dec 16, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Li STT, Frohna JG, Bostwick SB. Using your personal mission statement to INSPIRE and achieve success. Acad Pediatr. 2017;17(2):107–109. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2016.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Howard-Grenville J. Caring, courage and curiosity: reflections on our roles as scholars in organizing for a sustainable future. Organ Theory. 2021;2(1) doi: 10.1177/2631787721991143. Published. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Larocque N, Shenoy-Bhangle A, Brook A, et al. Resident experiences with virtual radiology learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Acad Radiol. 2021;28(5):704–710. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2021.02.006. Epub 2021 Feb 15. PMID: 33640229; PMCID: PMC7883720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Belfi LM, Dean KE, Bartolotta RJ, et al. Medical student education in the time of COVID-19: a virtual solution to the introductory radiology elective. Clin Imaging. 2021;75:67–74. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2021.01.013. Epub 2021 Jan 20. PMID: 33497880; PMCID: PMC7816883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Belfi LM, Dean KE, Sailer DS, et al. Virtual journal club beyond the pandemic: an enduring and fluid educational forum. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 2021 doi: 10.1067/j.cpradiol.2021.07.001. S0363-0188(21)00132-8Epub ahead of print. PMID: 34600795; PMCID: PMC8425288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Manion J. Joy at work! creating a positive workplace. J Nurs Admin. 2003;33(12):652–659. doi: 10.1097/00005110-200312000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]