Abstract

The white rot fungus Pleurotus ostreatus is an edible basidiomycete with increasing agricultural and biotechnological importance. Genetic manipulation and breeding of this organism are restricted because of the lack of knowledge about its genomic structure. In this study, we analyzed the genomic constitution of P. ostreatus by using pulsed-field gel electrophoresis optimized for the separation of its chromosomes. We have determined that it contains 11 pairs of chromosomes with sizes ranging from 1.4 to 4.7 Mbp. In addition to chromosome separation, the use of single-copy DNA probes allowed us to resolve the ambiguities caused by chromosome comigration. When the two nuclei present in the dikaryon were separated by protoplasting, analysis of their karyotypes revealed length polymorphisms affecting various chromosomes. This is, to our knowledge, the clearest chromosome separation available for this species.

Pleurotus ostreatus (“oyster mushroom”) is an edible basidiomycete of increasing biotechnological interest due to its ability to degrade both wood (10, 19) and chemicals related to lignin degradation products (1). Furthermore, this fungus produces secondary metabolites with pharmaceutical applications (2, 3, 14) and some proteins of potential industrial use (33, 34, 40). This biotechnological interest in P. ostreatus has fueled research on different aspects of its molecular biology. Genetic studies on it are limited, however, by the lack of knowledge about the details of the organization of its genetic material.

Fungal cytogenetics has been hampered by the small size of the chromosomes, the lack of known sexual stages in many medically and industrially important species, and the occurrence of endomitosis (4). The chromosomes of most fungi, however, are small enough to be separated by using pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) (see reference 21 for a review). The molecular karyotype of Coprinus cinereus, obtained by PFGE, has been correlated with its genetic map by the use of cloned gene probes and genetic studies (26, 27). Electrophoretic karyotyping of different fungi has shown that chromosome length polymorphisms (CLPs) are a common and prominent feature of these organisms (see reference 42 for a review). Two mechanisms have been proposed for the generation of these polymorphisms: increasing the copy numbers of particular sequences, such as the ribosomal DNA (rDNA) (27, 36) and subtelomeric repeats (9, 17), and mitotic and meiotic recombination processes (42, 43). In many cases, however, these CLPs seem to have minor genetic consequences, since many different karyotypes are found in a given species. However, some reduction in spore viability has been observed in outcrosses between C. cinereus strains with differences in their chromosome sizes (25) and in crosses between Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains with pronounced CLPs (42). For some species, it has been reported that CLPs within a given strain will eventually disappear by chromosome recombination (43).

The molecular karyotype of P. ostreatus has not been fully clarified yet. Several authors have reported different chromosome numbers and genome sizes by using various analytical techniques, including microscopy, restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis, and PFGE (4, 23, 31); however, the results are sometimes contradictory. By using PFGE experiments, Sagawa and Nagata (31) reported six chromosomes and a total genome size of 20.8 Mbp with chromosome sizes ranging from 2.1 to 5.2 Mbp per chromosome. Peberdy et al. (23) identified nine chromosomes by PFGE with a total genome size of 31.3 Mbp and chromosome sizes ranging from 1.1 to 5.7 Mbp per chromosome. Microscopy studies, on the other hand, have been hampered by the small size of P. ostreatus chromosomes. Notwithstanding, chromosome numbers ranging from 6 to 10 have been reported (4). The optimization of PFGE separation of fungal chromosomes (36, 37, 43) allowed the study of the molecular karyotype of Agaricus bisporus and the assignment of genes to chromosomes in C. cinereus. In this study, we used this technique to clarify the genomic structure of P. ostreatus. These data, together with a genetic linkage map of this P. ostreatus strain (16), will help in the design of breeding and cloning strategies in this mushroom.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Microbial strains and culture conditions.

P. ostreatus N001 is the dikaryotic fungal commercial strain used in this work (15, 24). Vegetative cultures of monokaryotic and dikaryotic mycelia were grown on solid Eger medium (20 g of malt extract, 15 g of agar, 1 liter of H2O) (7) at 24°C in the dark.

Protoplast preparation and mycelium regeneration.

The medium used for the production of P. ostreatus protoplasts was MMP (36): 10 g of malt extract, 5 g of mycological peptone (Oxoid, Hampshire, United Kingdom), and 1 liter of 10 mM 3′-(N-morpholino)-propanesulfonic acid (MOPS) adjusted to pH 7.0 with KOH. Solid medium agar-MMP was made by adding 15 g of agar per liter of MMP. Ten petri dishes containing agar-MMP covered with uncoated cellophane were each inoculated with 5 plugs of mycelium and incubated at 24°C in the dark. The mycelia were removed from the cellophane after 5 days of incubation and fragmented in liquid MMP with a Waring blender for 15 s at low speed. The suspension was used to inoculate three 2-liter Fernbach flasks (150 ml of MMP per flask) and incubated for 2 days at 24°C in the dark without shaking. The mycelium was collected by filtration through a nylon cloth (300-μm mesh) and rinsed with sterile water. The washed mycelium was removed from the nylon cloth and transferred to a clean sterile tube which was filled up to 40 ml with sterile water. Then 40 ml of 2× protoplasting medium (3 mg of Trichoderma harzianum cell wall lytic enzymes per ml [37, 38], 1.2 M sucrose, and 10 mM MOPS [pH 6.0] adjusted with KOH and sterilized by filtration through a 0.45-μm-pore-size membrane) was added. The suspension was mixed, transferred to a Fernbach flask, and incubated for 1 h at 24°C under gentle shaking. The mixture of hyphal fragments and protoplasts was filtered through nylon cloths of 1,000-, 500-, and 150-μm mesh equilibrated with 0.6 M sucrose and through a glass wool column (total column volume, 50 ml) equilibrated with 0.6 M sucrose, to remove cellular debris. Protoplasts were collected by centrifugation (15 min, 500 × g, 10°C) and washed twice with a 0.6 M sucrose solution. After suspension of the final pellet in 0.6 M sucrose, the protoplast concentration was determined by using a hemocytometer.

Protoplast regeneration was performed in agar-MMP medium osmotically supported by 0.6 M sucrose. Protoplasts were diluted in 0.8% (wt/vol) low-melting-point agarose supplemented with 0.6 M sucrose kept at 35 to 38°C to a final concentration of 100 to 500 protoplasts per ml. One milliliter of the protoplast suspension was plated on each petri dish and incubated at 24°C.

Incompatibility tests.

The mating genotype of the monokaryotic protoclones isolated in this work was determined by mating experiments with the four incompatibility testers derived from P. ostreatus N001 (15). The mating trials were made by inoculating the protoclone and the corresponding tester, placed 4 cm apart in the center of a petri dish containing solid Eger medium. The plate was then incubated at 24°C in the dark for approximately 18 days, until the two mycelia formed a large contact zone. A piece of mycelium was cut off from the contact zone, placed on a new culture plate, allowed to grow for some days, and examined under the microscope for the presence of true clamp connections (dikaryons), unfused (false) clamp connections (common B heterokaryons), or the absence of clamp connections (common A heterokaryons) (8).

DNA manipulation.

For DNA isolation, 100 ml of liquid SMY culture medium (10 g of sucrose, 10 g of malt extract, 4 g of yeast extract, 1 liter H2O [pH 5.6]) was inoculated with either dikaryotic or monokaryotic mycelium and incubated at 24°C in the dark without shaking. Mycelia were collected by vacuum filtration and frozen in liquid nitrogen until used. DNA from 2 g of mycelium was purified by using the protocol described by Dellaporta et al. (5) with minor modifications: the frozen mycelium was ground to a fine powder with a mortar, resuspended in 15 ml of extraction buffer (100 mM Tris, 50 mM EDTA, 500 mM NaCl, 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol [pH 8.0]), and gently shaken. Then 10 ml of a solution of sodium dodecyl sulfate, containing 200 g of H2O per liter, was added to the suspension, and the mixture was incubated at 65°C for 10 min. Most of the proteins and polysaccharides were removed by adding 5 ml of 5 M potassium acetate followed by an incubation at 0°C for 20 min and removal of the precipitate by centrifugation. General molecular biology protocols were used as described by Sambrook et al. (32) and Dieffenbach and Dveksler (6).

Microsatellite analysis.

Microsatellite analysis was performed using the sequence 5′-GACA GACA GACA-3′ as an oligonucleotide. A PCR was performed in a reaction volume of 25 μl containing 100 ng of mycelial DNA as a template, 2 mM MgCl2, 67 mM Tris HCl (pH 8.8), 16 mM (NH4)2SO4, 0.1 g of Tween 20 per liter, a 200 μM concentration of each of the four nucleotide triphosphates (ATP, CTP, GTP, and TTP), 1.9 to 2.5 μM concentrations of the primer oligonucleotide, and 1 U of Taq polymerase (Eurobiotaq; Ecogen, Barcelona, Spain). The amplification reactions were performed in a Perkin-Elmer Cetus DNA cycler (The Perkin-Elmer Corporation, Norwalk, Conn.). The amplification reactions were performed for 35 cycles with the following touchdown (11) cycle profile: a 1-min DNA denaturation step at 94°C, a 2-min annealing step (see below), and a 3-min extension step at 72°C. The annealing temperature in the first two cycles was 65°C; it was subsequently reduced each cycle by 2°C for the next 11 cycles and was continued at 40°C for 22 cycles. The reaction was finished with a 7-min-long extension step at 72°C. Amplification products were analyzed by electrophoresis in 1.5% (wt/vol) agarose gels in TAE buffer (400 mM Tris, 200 mM sodium acetate, 20 mM EDTA [pH 8.3]) and stained with ethidium bromide.

Chromosome-sized DNA preparations.

The isolation of genomic DNA suitable for chromosome separation by PFGE was performed as described by Sonnenberg et al. (36): protoplasts were diluted with 2% (wt/vol) InCert agarose (FMC Corporation, Rockland, Maine) kept at 42°C to a final concentration of 0.7% (wt/vol) agarose and 109 protoplasts per ml. After transfer to a prewarmed mold (40°C), the agarose was allowed to solidify on ice for 30 min. The resulting plugs were incubated in NDS buffer (0.5 M EDTA, 0.01 M Tris-HCl [pH 9.5], 1% [wt/vol] N-laurylsarcosine) containing 1 mg of proteinase K per ml for 25 h at 50°C. The plugs were washed three times in 50 mM EDTA (pH 8.0) at room temperature and stored at 4°C in 50 mM EDTA containing 0.2% (wt/vol) NaN3 until they were used.

Pulsed-field electrophoretic separation of chromosomes.

Pulsed-field electrophoresis conditions were optimized for the separation of P. ostreatus chromosomes. The modifications were based on the method previously described by Sonnenberg et al. (37). The gels were run at 14°C in 0.8% (wt/vol) agarose (SeaKem; FMC Corporation) in 0.5× TBE-cytidine buffer (1× TBE-cytidine is 0.089 M Tris-borate, 0.0025 M EDTA, 1 mM cytidine [pH 8.3]) with a CHEF-DR II apparatus (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.). The electrophoretic parameters used had three ramped switching intervals: (i) from 600 to 800 s at 100 V during 48 h, (ii) from 2,500 to 3,000 s at 50 V during 48 h, and (iii) from 3,300 to 3,600 s at 50 V during 96 h. The electrophoretic buffer was replaced once after 96 h. The chromosomes were visualized by ethidium bromide staining by using a solution containing 0.5 μg of ethidium bromide per ml in 1 mM cytidine. The chromosomes of Hansenula wingei and of Schizosaccharomyces pombe (Bio-Rad) were used as size standards.

Identification of chromosome-specific DNA probes.

Two different kinds of chromosome-specific DNA tags were used: probes for functional genes and anonymous DNA sequences (Table 1). The anonymous probes were generated as described by Williams et al. (41) and Larraya et al. (15): PCRs for the generation of randomly amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) markers were performed in a reaction volume of 25 μl containing 100 ng of mycelial DNA as a template, 2 mM MgCl2, 67 mM Tris HCl (pH 8.8), 16 mM (NH4)2SO4, 0.1 g of Tween 20 per liter, a 200 μM concentration of each of the four nucleotide triphosphates (ATP, CTP, GTP, and TTP), 1.9 to 2.5 μM concentrations of the primer oligonucleotide, and 1 U of Taq polymerase (Eurobiotaq; Ecogen). The oligonucleotides used as primers for the reaction were 10-mers belonging to the S, L, and R Operon series (Operon Technologies Inc., Alameda, Calif.). Amplification reactions were performed in a PTC-200 (Peltier thermal cycler; MJ Research, Watertown, Mass.) by using the following program: a 1-min denaturation at 94°C, a 1-min annealing at 37°C, and a 1.3-min extension at 72°C, for 39 cycles. Amplification products were analyzed by electrophoresis in 1.5% (wt/vol) agarose gels in TAE buffer (400 mM Tris, 200 mM sodium acetate, 20 mM EDTA [pH 8.3]) and stained with ethidium bromide. For molecular size markers, HindIII-EcoRI-digested λ DNA was used (32). The appropriate RAPD markers were extracted from the agarose gels and cloned into pGEM-T (Promega, Southampton, United Kingdom) so they could be used as chromosome-specific probes.

TABLE 1.

Chromosome sizes in the two protoclones obtained from P. ostreatus N001

| Chromosome no. | Chromosome size (Mbp) for protoclone:

|

Chromosome size difference (%)a | Chromosome-specific marker | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PC9 | PC15 | ||||

| I | 4.7 | 4.7 | 0 | vmh1 | This study |

| II | 4.7 | 4.0 | 15 | Rib | This study |

| III | 4.4 | 4.7 | −7 | S11900 | This study |

| IV | 3.6 | 3.5 | 3 | L121841 | This study |

| V | 3.4 | 3.5 | −3 | L15614 | This study |

| VI | 3.3 | 2.9 | 12 | POX1 | 10 |

| VII | 3.0 | 3.3 | −10 | L16877 | This study |

| VIII | 3.0 | 2.9 | 3 | R8303 | This study |

| IX | 2.2 | 2.0 | 9 | L31338 | This study |

| X | 1.8 | 1.7 | 6 | vmh3 | This study |

| XI | 1.4 | 1.5 | −7 | fbh1 | 24 |

| Total | 35.3 | 34.7 | 2 | ||

Calculated as [(chromosome size in PC9 − chromosome size in PC15)/chromosome size in PC9)] × 100.

Probe labeling.

Appropriate DNA probes were labeled with digoxigenin according to the supplier’s specifications (Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany) (13). PFGE-separated chromosomes were blotted onto the appropriate membranes and hybridized with the digoxigenin-labeled probes.

Biological material accession numbers.

The two protoclones produced by dedikaryotization of P. ostreatus N001 described in this paper have been deposited in the Spanish Type Culture Collection under the accession numbers in parentheses: PC9 (CECT20311) and PC15 (CECT20312).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The chromosome-specific DNA sequences described in this paper have been deposited in the EMBL and GenBank sequence databases under the accession numbers in parentheses: vmh1 (AJ238147), Rib (AJ242635), S11900 (AJ242636), L121841 (AJ242637), L15614 (AJ242640), L16877 (AJ242641), R8303 (AJ242642), L31338 (AJ242643), and vmh3 (AJ238148).

RESULTS

Protoclone isolation.

In most fungi, the constituent nuclei of the dikaryon do not fuse during vegetative growth. Protoplasting of the mycelium and isolation of colonies derived from single regenerated protoplasts occasionally results in monokaryons. These monokaryons are called protoclones (35), and their nuclear constitution is identical to either one of the two parental nuclei present in the dikaryon from which they derived. In contrast to the parental monokaryons used to construct a dikaryon by mating, the protoclones share the cytoplasm of the dikaryon they were produced from.

In order to isolate protoclones containing each one of the two nuclei present in P. ostreatus N001, mycelia from 3- to 5-day-old regenerated protoplasts were checked under the stereomicroscope to identify those lacking the clamp connections characteristic of dikaryotic mycelia. Twenty-four of 200 mycelia studied lacked clamp connections and were selected for further characterization. The monokaryotic nature of the selected protoclones was confirmed by a microsatellite analysis that allowed us to classify them into two different groups (of 12 individuals each) corresponding to the two possible alternative nuclei (data not shown). Crosses between members of different groups led to dikaryons with clamp connections, whereas no clamp formation was seen after crosses between members of the same group.

The incompatibility genotype of one protoclone belonging to each one of the two alternative groups was determined by mating tests with each one of the four testers representing the combination of the incompatibility alleles present in P. ostreatus N001 (15). The incompatibility genotype of protoclone PC9 was A2B1 and that of protoclone PC15 was A1B2. These two protoclones were used in the rest of the experiments (described below).

Electrophoretic karyotype of P. ostreatus N001.

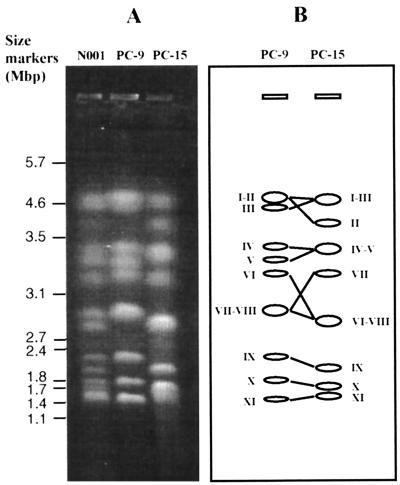

The chromosomes of P. ostreatus N001 (dikaryon) and of the protoclones (monokaryons) PC9 and PC15, each of the latter bearing one of the two nuclei present in the dikaryon, were separated by PFGE (Fig. 1). The number of bands that could be resolved differs for the two protoclones: nine different bands could be identified in PC9, whereas eight bands appeared in the lane corresponding to PC15. Ethidium bromide staining of the chromosome bands revealed two in PC9 (4.7 and 2.9 Mbp) and three in PC15 (4.7, 3.4, and 2.9 Mbp) which were stained more intensely than the others, suggesting that each one of them could correspond to two different chromosomes of approximately the same size. The lane corresponding to the dikaryon, on the other hand, showed all of the bands that appeared in each one of the two protoclones, as expected. The sizes of the P. ostreatus N001 chromosomes varied between 1.4 and 4.7 Mbp (Table 1). Moreover, chromosome sizes in the two protoclones were different, indicating CLPs within P. ostreatus N001.

FIG. 1.

Molecular karyotype of P. ostreatus N001. (A) PFGE separation of the chromosomes from the dikaryon N001 and the two protoclones PC9 and PC15. (B) Idiotype of the chromosomes present in the protoclones PC9 and PC15.

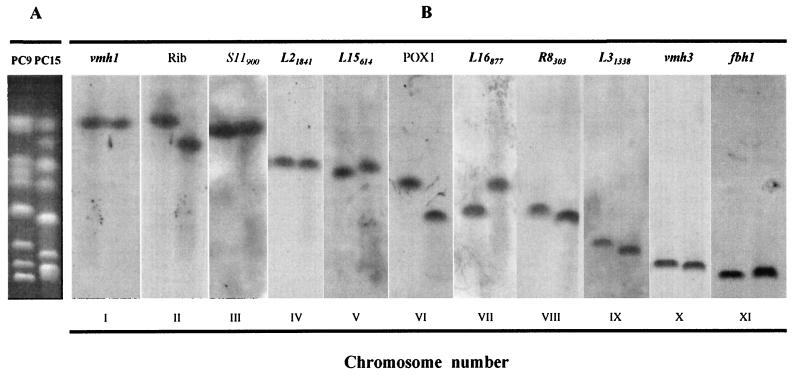

In order to clarify whether the electrophoretic bands showing a high intensity corresponded to two chromosomes of similar size and to identify the members of each pair of corresponding chromosomes, DNA probes representing single-copy P. ostreatus N001 genomic sequences were used. The probes were selected among the RFLP markers mapping in different linkage groups of P. ostreatus N001 (16), were isolated as RAPD markers, and were checked as probes for RFLP detection. The results of the hybridization of 11 selected probes are shown in Fig. 2. The probe Rib is homologous to fragments of the rDNA sequence of other fungi, and it is presumed to be a bona fide marker for this gene in P. ostreatus. This probe allowed the identification of the two chromosome II homologues in PC9 and PC15, which appear to be polymorphic in length. Similarly, probes L15614, POX1, L16877, and R8303 allowed the identification of chromosomes V, VI, VII, and VIII, respectively, which were also polymorphic in length when the two protoclones were compared. In every case, the hybridization intensity of a given probe in the two corresponding chromosomes was the same. In summary, it appeared that two probes of different linkage groups hybridizing to a double band in one of the protoclones always hybridized to two different bands in the other protoclone. In this way, all corresponding chromosomes could be identified (Fig. 1B), a total of 11 chromosomes could be identified, and the ambiguities caused by CLP could be resolved.

FIG. 2.

Specific probe assignment to the different chromosomes of P. ostreatus. (A) PFGE separation of the chromosomes present in the protoclones PC9 and PC15. (B) Southern blot analysis of the hybridization of chromosome-specific probes selected among the RFLP probes used to construct the linkage map of P. ostreatus.

The data gathered in the PFGE and in the probe hybridization experiments allowed the drawing of the chromosome scheme shown in Fig. 1B. The minimum number of chromosomes per haploid genome in P. ostreatus would, most probably, be 11. Chromosomes were numbered consecutively according to their sizes in protoclone PC9, from the largest (number I) to the smallest (number XI) chromosome. As the occurrence and extent of chromosome translocations have not been systematically studied, these chromosome designations (numbers) should be considered preliminary. Table 1 shows the sizes of the different chromosomes in each one of the two protoclones, the relative size differences between the members of each pair of corresponding chromosomes, and the genome size for each one of the two protoclones. The total dikaryotic genome size for P. ostreatus N001 is approximately 70.0 Mbp.

DISCUSSION

The experiments described in this study allowed the identification of 11 chromosomes per haploid genome in this strain of P. ostreatus. This number also corresponds to the number of linkage groups identified in P. ostreatus N001 (16). Additionally, each chromosome was individualized by chromosome-specific probes which allowed the clarification of ambiguities due to CLPs. Chromosome sizes cover all the ranges described by other authors for this species. The optimization of the pulse conditions allowed the reproducible resolution of chromosomes which, otherwise, would have comigrated in complex bands. The total haploid genome length for P. ostreatus is, on average, 35.0 Mbp. This value is slightly higher than that published by Peberdy et al. (23) (31.3 Mbp).

CLPs in fungi have been reported by several authors (see reference 42 for a review). Our data indicate that CLPs occur also in P. ostreatus, even within a single dikaryon. The fate of these polymorphic chromosomes during the meiotic process has not been investigated.

Table 1 shows the relative size differences between the two members of each pair of homologous chromosomes. Chromosomes II, VI, and VII show the major relative differences (i.e., more than 10% of their size). The rest of the chromosome size variations fall in the range of 3 to 9%, with the exception of chromosome I which was, essentially, of the same size in both protoclones. Interestingly, the size difference for the whole genome between the two protoclones is rather small (0.7 Mbp, 2% of the total size). This suggests that the total amount of genetic information present in each one of the two protoclones is similar, although it is differently organized. In this context, translocations have been demonstrated in C. cinereus (43) that support different organizations of the same genetic information in these fungi.

The size difference for chromosome II between protoclones PC9 and PC15 is 0.7 Mbp. This is about 15% of its total size. This chromosome carries the genomic region hybridizing to the rDNA probe. CLPs in chromosomes carrying rDNA genes have been reported by other authors in A. bisporus (36), Candida albicans (12, 29), Ustilago hordei (20), Leptosphaeria maculans (22), S. cerevisiae (29), and Cladosporium fulvum (39). According to Pukkila and Skrzynia (27) and Sonnenberg et al. (36), this polymorphism in C. cinereus and A. bisporus can be due to differences in the copy numbers of the rDNA genes. In the case of P. ostreatus, however, we could not find differences in the rDNA gene copy numbers between the two homologous chromosomes. This suggests that either the polymorphism detected in chromosome II is not due to the copy number of the rDNA genes or that the copy number polymorphism falls outside of the region detected by the probe used. It is interesting, however, to point out that a positive correlation between the growth rate and rDNA copy number has been reported in different fungi, such as Kluyveromyces lactis (18), Neurospora crassa (28), C. albicans, and S. cerevisiae (30). In this context, it is worth mentioning that protoclone PC9 (which carries a larger chromosome II) grows faster than protoclone PC15 (which carries a smaller chromosome II) (unpublished results). The sizes of chromosome VI differ by 0.4 Mbp (12% of its total size) when the homologous chromosomes in protoclones PC9 and PC15 are compared. It is relevant to point out that the two laccase genes probed in these experiments (POX1 and POX2) (10) hybridize to this chromosome and that chromosome VI was larger in protoclone PC9 (a fast-growing monokaryon) than in PC15 (a slow-growing monokaryon). The sizes of chromosome VII differ by 0.3 Mbp (9% of its total size) when the homologous chromosomes in protoclones PC9 and PC15 are compared. Finally, chromosome IX shows a small CLP (0.2 Mbp, corresponding to 7% of its total length). It is interesting to point out that RFLP probes found to be genetically linked to the B type incompatibility locus hybridize to this chromosome (16).

The CLPs detected in P. ostreatus N001 could reflect the hybrid nature of this commercial strain, which is vegetatively propagated by mushroom producers without going through sexual stages that would normalize chromosome sizes as predicted by the model of Zolan et al. (42, 43).

In summary, the results presented here clarify the chromosome number in P. ostreatus, demonstrate the existence of CLPs within a strain, and raise questions about the fate of chromosomes during meiosis in this fungus. These results will complement those of the P. ostreatus linkage map (16) and will help in the genetic manipulation of this fungus for breeding and biotechnological purposes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the research project BIO94-0443 of the Comisión Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología, Funds of the Universidad Pública of Navarra (Pamplona, Spain) and by Funds of the Mushroom Experimental Station (Horst, The Netherlands). L.M.L., G.P., and M.M.P. hold grants from the Departamento de Educación del Gobierno de Navarra, the Departamento de Industria del Gobierno de Navarra, and the Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia (FPU, Spain), respectively.

We thank Anton S. M. Sonnenberg for discussion of the data and Karen D. Hollander for optimizing and running the CHEF gels.

L.M.L. and G.P. contributed equally to this work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bezalel L, Hadar Y, Cerniglia C E. Enzymatic mechanisms involved in phenanthrene degradation by the white rot fungus Pleurotus ostreatus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:2495–2501. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.7.2495-2501.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bobek P, Kuniak L, Ozdin L. The mushroom Pleurotus ostreatus reduces secretion and accelerates the fractional turnover rate of very-low-density lipoproteins in the rat. Ann Nutr Metab. 1993;37:142–145. doi: 10.1159/000177762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bobek P, Ozdin L. The mushroom Pleurotus ostreatus accelerates plasma very-low-density lipoprotein clearance in hypercholesterolemic rat. Physiol Res. 1994;43:205–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chiu S-W. Nuclear changes during fungal development. In: Chiu S-W, Moore D, editors. Patterns in fungal development. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 1996. pp. 105–125. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dellaporta S L, Wood J, Hicks J B. A plant DNA minipreparation: version II. Plant Mol Biol Report. 1983;1:19–21. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dieffenbach C W, Dveksler G S. PCR primer. A laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eger G. Rapid method for breeding Pleurotus ostreatus. Mushroom Sci. 1976;9:567–576. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eugenio C P, Anderson N A. The genetics and cultivation of Pleurotus ostreatus. Mycologia. 1968;60:627–634. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Farman M L, Leong S A. Genetic and physical mapping of telomeres in the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe grisea. Genetics. 1995;140:479–492. doi: 10.1093/genetics/140.2.479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giardina P, Cannio R, Martirani L, Marzullo L, Palmieri G, Sannia G. Cloning and sequencing of a laccase gene from the lignin-degrading basidiomycete Pleurotus ostreatus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:2408–2413. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.6.2408-2413.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hecker K H, Roux K H. High and low annealing temperatures increase both specificity and yield in touchdown and stepdown PCR. BioTechniques. 1996;20:478–485. doi: 10.2144/19962003478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iwaguchi S, Homma M, Tanaka K. Clonal variation of chromosome size derived from the rDNA cluster in Candida albicans. J Gen Microbiol. 1992;138:1177–1184. doi: 10.1099/00221287-138-6-1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koltke H J, Sagner G, Kessler C, Schmitz G. Sensitive chemiluminescent detection of digoxigenin-labeled nucleic acids: a fast and simple protocol and its applications. BioTechniques. 1992;12:104–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kurashige S, Akuzawa Y, Endo F. Effects of Lentinus edodes, Grifola frondosa, and Pleurotus ostreatus administration on cancer outbreak, and activities of macrophages and lymphocytes in mice treated with a carcinogen, N-butyl-N-butanolnitrosamine. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol. 1997;192:175–183. doi: 10.3109/08923979709007657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Larraya L, Peñas M M, Pérez G, Santos C, Ritter E, Pisabarro A G, Ramírez L. Identification of incompatibility alleles and characterisation of molecular markers genetically linked to the A incompatibility locus in the white rot fungus Pleurotus ostreatus. Curr Genet. 1999;34:486–493. doi: 10.1007/s002940050424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Larraya, L. M., G. Pérez, E. Ritter, A. G. Pisabarro, and L. Ramírez. Unpublished data.

- 17.Louis E J, Naumova E S, Lee A, Naumov G, Haber J E. The chromosome end in yeast: its mosaic nature and influence in recombinational dynamics. Genetics. 1994;136:789–802. doi: 10.1093/genetics/136.3.789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maleszka R, Clark-Walker G D. Magnification in the rDNA cluster in Kluyveromyces lactis. Mol Gen Genet. 1990;223:342–344. doi: 10.1007/BF00265074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marzullo L, Cannio R, Giardina P, Santini M T, Sannia G. Veratryl alcohol oxidase from Pleurotus ostreatus participates in lignin biodegradation and prevents polymerization of laccase-oxidized substrates. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:3823–3827. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.8.3823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McCluskey K, Mills D. Identification and characterization of chromosome length polymorphisms among strains representing fourteen races of Ustilago hordei. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 1990;3:366–373. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mills D, McCluskey K. Electrophoretic karyotypes of fungi: the new cytology. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 1990;3:351–357. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morales V M, Séguin-Swartz G, Taylor J L. Chromosome size polymorphisms in Leptosphaeria maculans. Phytopathology. 1993;83:503–509. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peberdy J F, Hanifah A H, Jia J-H. New perspectives on the genetics of Pleurotus. In: Chang S-T, Buswell J A, Chiu S W, editors. Mushroom biology and mushroom products. Hong Kong: The Chinese University Press; 1993. pp. 55–62. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peñas M M, Ásgeirsdóttir S A, Lasa I, Culiañez-Macià F A, Pisabarro A G, Wessels J G H, Ramírez L. Identification, characterization, and in situ detection of a fruit-body-specific hydrophobin of Pleurotus ostreatus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:4028–4034. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.10.4028-4034.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pukkila P J. Methods of genetic manipulation in Coprinus cinereus. In: Chang S T, Buswell J A, Miles P J, editors. Culture collection and breeding of edible mushrooms. Philadelphia, Pa: Gordon & Breach; 1992. pp. 249–264. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pukkila P J, Casselton L A. Molecular genetics of the agaric Coprinus cinereus. In: Bennet J W, Lasure L L, editors. More gene manipulation in fungi. San Diego, Calif: Academic Press Inc.; 1991. pp. 126–150. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pukkila P J, Skrzynia C. Frequent changes in the number of reiterated ribosomal RNA genes throughout the life cycle of the basidiomycete Coprinus cinereus. Genetics. 1993;133:203–211. doi: 10.1093/genetics/133.2.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Russell P J, Rodland K D. Magnification of rRNA gene number in a Neurospora crassa with a partial deletion of the nucleolus organizer. Chromosoma. 1986;93:337–340. doi: 10.1007/BF00327592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rustchenko E P, Curran T M, Sherman F. Variation in the number of ribosomal DNA units in morphological mutants and normal strains of Candida albicans and in normal strains of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Bacteriol. 1993;174:7189–7199. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.22.7189-7199.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rustchenko E P, Sherman F. Physical constitution of ribosomal genes in common strains of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 1994;10:1157–1171. doi: 10.1002/yea.320100904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sagawa I, Nagata Y. Analysis of chromosomal DNA of mushrooms in genus Pleurotus by pulsed field gel electrophoresis. J Gen Appl Microbiol. 1992;38:47–52. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sarkar S, Martínez A T, Martínez M J. Biochemical and molecular characterization of a manganese peroxidase isoenzyme from Pleurotus ostreatus. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1997;1339:23–30. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(96)00201-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shin K-S, Oh I-K, Kim C-J. Production and purification of remazol brilliant blue R decolorizing peroxidase from the culture filtrate of Pleurotus ostreatus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:1744–1748. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.5.1744-1748.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sonnenberg A S, Wessels J G, van Griensven L J. An efficient protoplasting/regeneration system for Agaricus bisporus and Agaricus bitorquis. Curr Microbiol. 1988;17:285–291. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sonnenberg A S M, de Groot P W J, Schaap P J, Baars J J P, Visser J, van Griensven L J L D. Isolation of expressed sequence tags of Agaricus bisporus and their assignment to chromosomes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:4542–4547. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.12.4542-4547.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sonnenberg A S M, Den Hollander K, van de Munckhof A P J, van Griensven L J L D. Chromosome separation and assignment of DNA probes in Agaricus bisporus. In: van Griensven L J L D, editor. Genetics and breeding of Agaricus. Wageningen, The Netherlands: Pudoc; 1991. pp. 57–61. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sonnenberg A S M, Wessels J G H. Heterokaryon formation in the basidiomycete Schizophyllum commune by electrofusion of protoplasts. Theor Appl Genet. 1987;74:654–658. doi: 10.1007/BF00288866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Talbot N J, Oliver R P, Coddington A. Pulse field gel electrophoresis reveals chromosome length differences between strains of Cladosporium fulvum (syn. Fulvia fulva) Mol Gen Genet. 1991;229:267–272. doi: 10.1007/BF00272165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wessels J G. Hydrophobins: proteins that change the nature of the fungal surface. Adv Microb Physiol. 1997;38:1–45. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2911(08)60154-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Williams J G K, Kubelik A R, Livak K J, Rafalski J A, Tingey S V. DNA polymorphisms amplified by arbitrary primers are useful as genetic markers. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:6531–6535. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.22.6531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zolan M E. Chromosome-length polymorphism in fungi. Microbiol Rev. 1995;59:686–698. doi: 10.1128/mr.59.4.686-698.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zolan M E, Heyler N K, Stassen N Y. Inheritance of chromosome-length polymorphisms in Coprinus cinereus. Genetics. 1994;137:87–94. doi: 10.1093/genetics/137.1.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]