SUMMARY

We examined the impact of the neonatal hepatitis B immunization programme, first provided to all neonates born to mothers screened positive for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) in late 1983, on the age-specific prevalence of HBsAg carriage in teenage mothers managed in 1998–2008. HBsAg carriage was found in 2·5%, 2·7%, 8·8% and 8·0% of mothers aged ⩽16, 17, 18, and 19 years, respectively (P = 0·004), which was also correlated with advancing age (P = 0·011). While neither difference nor correlation with age was found in mothers born before 1984, the prevalence of 1·2%, 1·5%, 7·1% and 8·3%, respectively, was significantly different among (P = 0·008) and correlated with (P = 0·002) age in mothers born 1984 onwards. Regression analysis indicated there was a significantly higher incidence of HBsAg carriage from age 17 onwards (adjusted odds ratio 2·55, 95% confidence interval 1·07–6·10, P = 0·035), suggesting that the protective effect of the vaccine declined in late adolescence.

Key words: Hepatitis B, neonatal immunization, pregnancy, teenage

INTRODUCTION

Infection with hepatitis B virus (HBV) is endemic in many parts of the world, and vertical transmission plays a major role [1–5]. To prevent vertical transmission of HBV, a neonatal immunization programme has been adopted in many countries [6–10]. In Hong Kong, this programme was introduced in 1983 after its efficacy has been proven in a randomized study [1]. From 1983 to 1988, this programme, consisting of immunoglobulin at the time of birth together with a three-dose vaccination, was selectively applied to neonates born to mothers screened positive for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) [11]. From November 1988, this programme became universal and covered all neonates born to both HBsAg-positive and HBsAg-negative mothers [12, 13]. Catch-up vaccination to maximize vaccination coverage was also given to students born before 1983 [14]. The vaccination programme was extended in July 1992 to cover all children born between January 1986 and November 1988, so that by the end of 1990s, all children aged ⩽13 years and residing in Hong Kong irrespective of place of birth would have been immunized [15]. Finally, a supplemental hepatitis B vaccination programme was launched starting in the 1998–1999 school year targeting primary 6 students who had not yet received or completed the three-dose regimen. This programme supplemented existing programmes allowing all local children to receive protection against HBV infection before reaching sexual maturity, a time when HBV is commonly transmitted through sexual contact [16]. Since then, the vaccine was widely available from institutions such as universities, and non-governmental organizations such as the Family Planning Association and general practitioners [11]. In view of its reported efficacy [17–24] and the almost complete coverage of all children provided by the different programmes [14–16], a significant decline in the prevalence of positive HBsAg in our antenatal screening would be expected. However, in our latest survey on an unselected sample of women in the antenatal clinic, prevalence remained at 9·1%, and 4·8% of women with a history of hepatitis B vaccination were found to be HBV carriers [25].

Our observation [25] raises the question of the duration of protection of the hepatitis B vaccine, which is believed to be sufficient for lifelong protection [17, 18, 20–22]. Protective antibody concentration was found more than 10 years after neonatal vaccination in 64% of these children, and 97% of the remaining children demonstrated an anamnestic response [26]. Other studies have also found that the vaccine offered strong protection for up to 15–20 years [27–30]. On the other hand, anamnestic responses to booster vaccination given at age 15 years could not be found in half of the children vaccinated at birth [19]. Another study [31] found that antibody-positive rate declined from 100% at age 2 years to 75% at age 6 years for complete vaccines, although this does not necessarily mean a decline in protection. Similarly, undetected antibody levels were found in 22·9% of vaccinated children, which was related to the interval between vaccination and testing, being 36·1%, 20% and 14·6% for the 5–8 years, 2·5–5 years, and 1–2·5 years age groups, respectively, but which was not influenced by gestational age, birthweight or parental origin [32]. A single booster dose 10 years after primary neonatal vaccination has been proposed, as protection was estimated to last between 7·5 and 10·5 years only [33]. Furthermore, despite immunization, 1·3–3·5% of infants became HBsAg carriers 15 years later [27]. Even among complete vaccinees, 1·3% were HBsAg positive at age 2–6 years [31]. In Micronesians vaccinated at birth, 8% showed evidence of past HBV infection 15 years later although none had chronic infection, and only 7·3% of uninfected individuals had positive antibody while an anamnestic response was found in 47·9% of the remaining individuals [34]. Thus the lifelong protection offered by the full neonatal vaccination programme is by no means guaranteed.

As the protection induced by the HBV vaccine would be reflected by the incidence of HBV infection when the cohort reaches adulthood, the best way to resolve any uncertainties regarding the protection provided by the HBV vaccine would be to examine the age-specific prevalence of HBsAg carriage in vaccinees in their transition to adulthood. In a manner similar to HBV immunization, rubella immunization was first introduced in Hong Kong in 1978 to primary 6 schoolgirls and women of child-bearing age, it then evolved to universal coverage of all children aged 1 year using the triple MMR vaccine [35], and finally, all potentially non-immune children aged 1–19 years were targeted in a mass measles-mumps-rubella immunization campaign from July to November 1997, which led to a fall in the measles notification rate from 59/100 000 in May 1997 to 0·9/100 000 in 1998 [36]. We therefore examined the age-specific prevalence of HBsAg carriage in teenage mothers who were universally screened for HBsAg during antenatal care in our department from 1998 to 2008 to address this issue, and we examined the association of the incidence of rubella non-immunity as a proxy for vaccination coverage and immunity status of the subjects in this study.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In Hong Kong, all local residents are entitled to free antenatal care and subsidized inpatient obstetric treatment and confinement in the obstetric units of the regional public hospitals under the Hospital Authority where obstetric management is based on medical indications and protocols established on the basis of international and local guidelines. Our hospital is one of these units with an annual delivery rate of over 6000 and a level III neonatal intensive-care unit. Antenatal care includes the routine screening for HBsAg, rubella immunity, and syphilis by the Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) test. Mothers with positive HBsAg screening are considered to have a HBV infection so that immunoglobulin and HBV vaccine will be given to the newborn infant after delivery. The subjects of this retrospective cohort study were the teenage mothers (aged ⩽19 years at delivery) managed in our department from January 1998 to June 2008. The final study cohort consisted of subjects who were born in Hong Kong as indicated by the alphabetical prefix in their identity card number, and for whom the antenatal screening results were available in the database. All the women remained anonymous, and the study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (Joint Chinese University of Hong Kong – New Territories East Cluster Clinical Research Ethics Committee, reference number CRE-2009.271).

The results of the screening tests, the antenatal examination findings, details of each admission including the one for delivery, and pregnancy complications and outcome as coded according to ICD codes, are captured in a master computerized database set up by the Hospital Authority for the generation of annual statistics. The data entry is made by trained midwives and obstetricians in the clinics and wards, and is doubled-checked after delivery. This database has been validated previously [37]. From the master database, all eligible cases were retrieved and transferred to a research database for analysis; cases without the HBsAg result were excluded.

The HBsAg-positive women (study group) were compared to the HBsAg-negative (comparison group) women, and the prevalence of HBsAg carriage was analysed by maternal age and then re-examined in two groups by their year of birth, i.e. <1984 or ⩾1984, as the neonatal HBV vaccination programme was implemented towards the end of 1983. All infants born in Hong Kong receive a vaccination record which is reviewed at the annual health assessment from primary school onwards, in order for remedial vaccination to be given to those who have failed to complete any of the programmes. The use of this record, together with the neonatal, catch-up and supplemental vaccination programmes mentioned earlier [11–16], ensured that for practical purposes, almost all of the children brought up in Hong Kong would have been immunized so that the detection of HBsAg would be an indication of failed immunization. As nutritional status before pregnancy may influence the immune response, we also examined the relationship between HBsAg status with short stature (height <151 cm in our population) and body mass index (BMI) at first visit, whether it was high (>25 kg/m2) or low (<19 kg/m2). We also analysed the incidence of iron deficiency anaemia as a proxy for maternal nutritional status, and underlying medical conditions and factors that could affect the immune response towards HBV vaccine or infection.

Statistical analysis was performed using Student's t test and χ2 test and calculation of odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Correlation with age was analysed by Spearman's correlation. Multiple logistic regression analysis was then performed to calculate the adjusted odds ratio (aOR) with 95% CI to determine the independent relationship between maternal HBV infection with the implementation of HBV vaccine, age, multiparity status, rubella non-immunity, and the presence of underlying medical conditions. Statistical analysis was performed using a commercially available statistical package (PASW Statistics v. 17.0, SPSS Inc., USA).

RESULTS

The final study cohort consisted of 1486 women, of whom 104 (7·0%) were HBsAg positive. These 1486 women accounted for 2·2% of the 66 748 women managed during this period. The study group had slightly but significantly higher mean maternal age as well as height, but there was no difference in their weight, BMI, incidence of multiparas, iron deficiency anaemia or underlying medical conditions (Table 1). While there was no difference in the incidence of positive VDRL test, the study group had a significantly higher incidence of rubella non-immunity (OR 3·07, 95% CI 1·62–5·81).

Table 1.

Maternal demographics between HBsAg-positive and HBsAg-negative mothers

| HBsAg positive | HBsAg negative | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 104 | 1382 | — |

| Age | 18·4 ± 0·7 | 18·1 ± 1·2 | <0·001 |

| ⩽ 18 years (%) | 44·2 | 51·8 | n.s. |

| Height | 159·5 ± 5·6 | 158·1 ± 5·7 | 0·022 |

| < 151 cm (%) | 5·2 | 7·8 | n.s. |

| Weight (kg) | 56·5 ± 7·9 | 55·4 ± 8·6 | n.s. |

| BMI | 22·2 ± 2·9 | 22·2 ± 3·2 | n.s. |

| > 25 kg/m2 (%) | 16·5 | 16·5 | n.s. |

| < 18·5 kg/m2 (%) | 10·3 | 10·2 | n.s. |

| Multiparas (%) | 9·6 | 9·1 | n.s. |

| Rubella non-immune (%) | 13·5 | 4·9 | <0·001 |

| VDRL positive (%) | 1·2 | 0·4 | n.s. |

| Iron deficiency anaemia (%) | 1·0 | 2·3 | n.s. |

| Any medical condition (%) | 4·8 | 5·9 | n.s. |

BMI, Body mass index; VDRL, Venereal Disease Research Laboratory test; n.s., not significant.

Results are mean±s.d. or % as indicated.

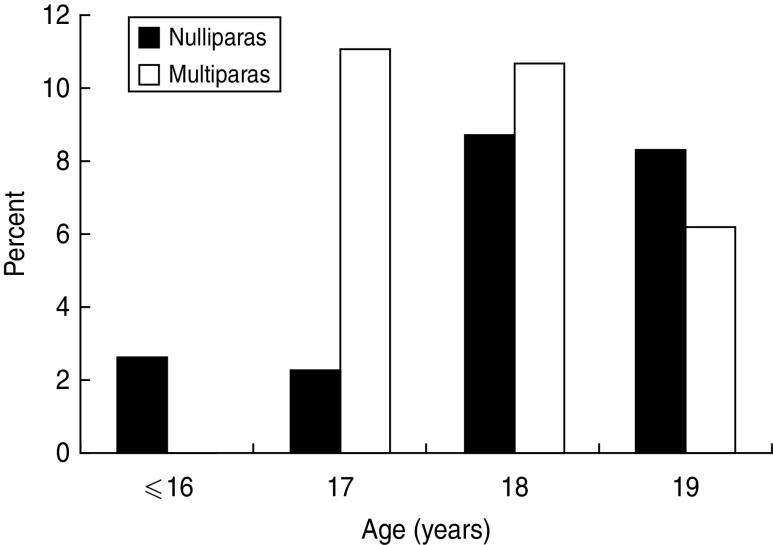

There were 7, 24, 87, 223, 421, and 724 mothers of ages 14, 15, 16, 17, 18 and 19 years, respectively. There were no mothers with positive HBsAg up to age 15, therefore mothers aged ⩽16 were grouped together into one group. The age-specific prevalence of HBsAg carriage was 2·5%, 2·7%, 8·8% and 8·0% for ages ⩽16, 17, 18, and 19 years, respectively, which was significantly different among (P = 0·004), and positively correlated with (P = 0·011) advancing age. When stratified by parity status into nulliparas and multiparas, there was only a significant difference among (P = 0·003) and positive correlation with (P = 0·023) age in the nulliparas, but there was no significant difference or correlation in the multiparas (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Age-specific prevalence of positive HBsAg according to maternal parity status. Nulliparas – significant difference among (P = 0·003) and positive correlation with (P = 0·023) age. Multiparas – no significant difference or correlation with age.

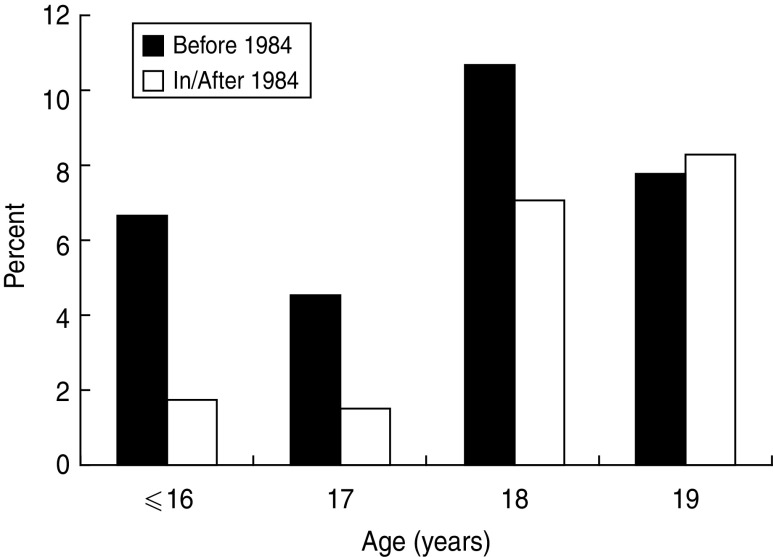

To examine the impact of implementation of HBV vaccination on the incidence of positive HBsAg, further analysis was performed stratified by birth before 1984 vs. 1984 onwards. The prevalences for ages ⩽16, 17, 18, and 19 years in mothers born before 1984 were 6·3%, 4·6%, 10·7% and 7·8%, respectively, which was not significantly different in, or correlated with, age (Fig. 2). On the other hand, for those born 1984 onwards, the prevalence was 1·2%, 1·5%, 7·1% and 8·3%, respectively, which was significantly different among (P = 0·008) and positively correlated with (P = 0·002) maternal age. Although the prevalence of HBsAg carriage was consistently higher for ages ⩽16, 17 and 18 years in mothers born before 1984, the difference failed to reach statistical significance (Table 2). However, when all mothers aged ⩽18 years were grouped together, the prevalence was significantly higher in those born before 1984 (8·6% vs. 4·3%, OR 2·11, 95% CI 1·15–3·87). For mothers aged 19 years, the prevalence in those born before 1984 was similar to that in mothers born 1984 onwards. When the prevalence of HBsAg carriage was compared between mothers aged 19 years and ⩽18 years, the difference was only significantly different for mothers born after 1984 (8·3% vs. 4·3%, OR 2·02, 95% CI 1·09–3·74, P = 0·023), and not for those born before 1984 (7·8% vs. 8·6%, P = 0·719).

Fig. 2.

Age-specific incidence of positive HBsAg according to the year of birth before or after implementation of HBV vaccination (1984). Mothers born before 1984 – no significant difference among or correlation with age. Mothers born 1984 onwards – incidence was significantly different among (P = 0·008) and positively correlated with (P = 0·002) maternal age.

Table 2.

Age-specific prevalence of HBV infection and characteristics of mothers born before and after implementation of the neonatal HBV vaccination programme in 1984

| Age | Born <1984 | Born ⩾1984 | OR (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ⩽16 (%) | 6·3 | 1·2 | 5·67 (0·50–64·77) | 0·119 |

| 17 (%) | 4·6 | 1·5 | 3·23 (0·58–18·02) | 0·159 |

| 18 (%) | 10·7 | 7·1 | 1·57 (0·79–3·10) | 0·193 |

| ⩽18 combined (%) | 8·6 | 4·3 | 2·11 (1·15–3·87) | 0·014 |

| 19 (%) | 7·8 | 8·3 | 0·95 (0·55–1·63) | 0·840 |

Results expressed in % and compared to χ2 test.

To determine if the mothers with positive HBsAg born before and after the implementation of the neonatal vaccination programme represented women with different characteristics, the mothers born before 1984 were compared to mothers born 1984 onwards stratified by their HBsAg status (Table 3). Of the HBsAg positive mothers, those born 1984 onwards tended to have a higher rate of shorter stature, and had a significantly higher rate of high BMI and rubella non-immunity. On the other hand, in the HBsAg-negative mothers, those born 1984 onwards included more nulliparas, a higher rate of rubella non-immunity, and a lower rate of underlying medical conditions. As the mothers born 1984 onwards had a higher rate of rubella non-immunity compared to their peers born before 1984, irrespective of their HBsAg status, the rate of rubella non-immunity was compared between HBsAg-positive and HBsAg-negative mothers born 1984 onwards. The rate of rubella non-immunity was significantly higher in HBsAg-positive mothers (OR 4·45, 95% CI 1·97–10·07, P < 0·001).

Table 3.

Maternal characteristics in mothers with and without HBV infection born before or after the implementation of the neonatal HBV vaccination programme in 1984

| Born <1984 | Born ⩾1984 | OR (95% CI) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HBsAg positive | ||||

| Nulliparas (%) | 90·0 | 90·9 | — | n.s. |

| Height <151 cm (%) | 1·7 | 10·8 | 7·03 (0·75–65·55) | 0·071 |

| BMI >25 kg/m2 (%) | 10·2 | 26·3 | 3·16 (1·04–9·58) | 0·036 |

| BMI <18·5 kg/m2 (%) | 13·6 | 5·3 | — | n.s. |

| Rubella non-immune (%) | 6·8 | 24·3 | 4·42 (1·25–15·62) | 0·014 |

| VDRL positive (%) | 0 | 3·6 | — | n.s. |

| Iron deficiency anaemia (%) | 1·7 | 0 | — | n.s. |

| Any medical condition (%) | 5·0 | 4·5 | — | n.s. |

| HBsAg negative | ||||

| Nulliparas (%) | 88·9 | 92·8 | 1·60 (1·10–2·33) | 0·012 |

| Height <151 cm (%) | 6·9 | 8·8 | — | n.s. |

| BMI >25 kg/m2 (%) | 15·9 | 17·1 | — | n.s. |

| BMI <18·5 kg/m2 (%) | 11·1 | 9·4 | — | n.s. |

| Rubella non-immune (%) | 3·2 | 6·7 | 2·20 (1·28–3·78) | 0·003 |

| VDRL positive (%) | 0·5 | 0·2 | — | n.s. |

| Iron deficiency anaemia (%) | 2·4 | 2·3 | n.s. | |

| Any medical condition (%) | 7·2 | 4·7 | 0·63 (0·40–0·98) | 0·043 |

BMI, Body mass index; VDRL, Venereal Disease Research Laboratory test; n.s., not significant.

Results expressed in % and compared to χ2 test.

To determine the independent effect of age, vaccination (in the form of year of birth), parity status, presence of medical conditions, and rubella non-immunity status, on positive HBsAg status in the mothers, logistic regression analysis was performed including all these factors in the model. Parity status, presence of medical conditions, and HBV vaccination were excluded as significant factors. Rubella non-immunity was associated with HBV infection [adjusted odds ratio (aOR) 3·12, 95% CI 1·62–6·00, P = 0·001]. Age overall was also an independent factor (P = 0·017). Taking age 19 years as the reference group, the association with HBV carriage for age ⩽16 years (aOR 3·93, 95% CI 0·93–16·59, P = 0·062) and 18 years (aOR 0·81, 95% CI 0·51–1·27, P = 0·356) failed to reach significance, while age 17 years was shown to be significantly associated with positive HBsAg (aOR 2·55, 95% CI 1·07–6·10, P = 0·035).

DISCUSSION

There are reports in the literature suggesting the protection by the hepatitis B vaccine is incomplete. One study found that despite immunization in infancy, 1·3–3·5% of subjects became HBsAg carriers 15 years later [27]. In another study, 1·3% and 4·5% of the complete and incomplete vaccines, respectively, were HBsAg positive at age 2–6 years [31]. Of university students vaccinated at birth, 18 years before, the prevalence of chronic HBV infection was 1·9% [38]. Ageing probably plays an under-appreciated role in the waning immune response in children and adults who had received vaccination in infancy. While most children and adolescents who had received a full course of vaccination after birth demonstrated an anamnestic response to a booster, the response rate was inversely correlated with age, being 97% for those aged 5 years compared to 60% for those aged 14 years [39], even though neonatal vaccination is effective in reducing carrier rate [40]. In Taiwan, the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) has declined from 0·54 to 0·20/100 000 children aged 6–14 years in those born before vs. after the vaccination programme, and vaccine failure (33·3–51·4%) was a major cause of HCC, but paradoxically hepatitis B carrier children born after the vaccination programme had a higher risk of HCC than those born before the programme, with a risk ratio of 2·3–4·5 [41]. Thus, many issues regarding the long-term efficacy of the hepatitis B vaccine remain unclear.

In this study, no mothers aged <16 years screened positive for HBsAg irrespective of whether they were born before or after the introduction of the neonatal hepatitis B immunization programme. On the other hand, the incidence of positive HBsAg screening increased rapidly from age 16 years onwards, an association that was significant in nulliparas but not in multiparas. This suggested that the rapid increase in the rate of infection was not only due to horizontal transmission, but that sexual transmission was probably an important, if not the leading, factor. When the protective effect of vaccination was examined, the age-specific prevalence for mothers born before 1984 showed neither significant difference nor correlation with age, whereas mothers born 1984 onwards showed a significant increase and positive correlation with age from 16 to 19 years. While there was a difference in the prevalence of HBsAg carriage for mothers aged <19 years and those born before and after the introduction of vaccine, this difference disappeared for mothers aged 19 years. Furthermore, for mothers born 1984 onwards, those aged 19 years had a more than twofold increase in HBsAg carriage rate compared to their younger peers. Taken together, our data suggested that neonatal vaccination against hepatitis B may not provide lifelong protection against horizontal transmission, and adolescents from the age of 16 onwards may be at risk of infection. As HBV is present in body fluids [42], and it can be transmitted through sexual intercourse [43–46], the most likely cause of acquisition of HBV infection in teenage mothers is through sexual intercourse with HBV carriers. In this regard, pregnant women would serve as the best model to test the protective effect of the HBV vaccine, since this group of subjects would inevitably be exposed to the risk of HBV infection when they underwent repeated unprotected sexual intercourse in order to conceive. For other teenage persons, the absence of HBsAg on screening could be related to no sexual exposure, sexual exposure with HBV-naive or immune subjects, or the use of barrier methods for contraception, so that it cannot be assumed that negative HBsAg screening would equate with HBV immunity unless the antibody titre is measured. In support of our hypothesis is the finding that the weighted age-specific prevalence of HBsAg increased from 1·9% in adolescents to 4·9% in those in their 20s [47] is highly suggestive of intimate and sexual contact as an important contributor to HBV infection in young adults.

Our results also suggest that the teenage mothers with HBV infection before and after the introduction of hepatitis B vaccine were associated with different characteristics, as more of those with positive HBsAg born 1984 onwards were of shorter stature and had a higher BMI. Similarly those screened negative for HBsAg included more nulliparas but had a lower incidence of underlying medical conditions. This suggested that there were different characteristics between women who acquired HBsAg with and without previous immunization, and that those who became carriers despite vaccination had some form of immune defect. It is intriguing to find that mothers born 1984 onwards were associated with increased rubella non-immunity, irrespective of their HBsAg status, and regression analysis confirmed that there was an independent association between rubella non-immunity with HBsAg carriage irrespective of vaccination. This confirmed our previous observation in the overall obstetric population [37], and suggests that there was indeed a subtle defect in immunity in teenage mothers with positive HBsAg, thus accounting also for their failure to develop rubella immunity. This defect is unlikely to be related to nutritional inadequacies, as there was no difference in the rate of iron deficiency anaemia, and more mothers with positive HBsAg born 1984 onwards had a high BMI. Further studies to explore the underlying immune defect are warranted.

There are potential limitations to this study. Owing to the design of the study and the source of the data, we cannot determine how many of the HBsAg carriers born 1984 onwards were hyporesponders, since this was never studied in Hong Kong. We also could not determine when and how the HBsAg carriers were infected, or how many of the HBsAg-negative mothers had been infected but seroconverted before pregnancy. Nevertheless, through the demonstration of the significant difference and positive correlation between the prevalence of HBsAg carriage with increasing age from ⩽16 to 19 years, the results indicate the possibility that the immunity induced with the hepatitis B vaccine is waning during adolescence. In support of this is the finding that in non-boosted children, the average decay in the geometric mean titre of anit-HBs from age 7 to 16 years was 20% per year [47]. This phenomenon, together with the likelihood of subtle immune defects, suggests that the best remedy is a booster dose of vaccine, especially in hyporesponders to the vaccine and high-risk adolescents [47]. In the literature, there are different views on the necessity of a booster dose of HBV vaccine after the neonatal immunization programme [19]. However, the Steering Committee for the Prevention and Control of Infectious Diseases in Asia recommended guidelines for booster dose in high-endemicity Asian populations that include boosting approximately 10–15 years after primary vaccination, when monitoring of antibody levels is not feasible, immunocompromised patients when the titre falls below 10 mIU/ml, and healthcare workers [48].

In conclusion, the result of this study and the relevant literature together support the implementation of a routine booster dose of hepatitis B vaccine in areas and populations of high endemicity. However, one booster dose of vaccine may not be sufficient to induce immune response in healthy adolescents with undetectable prebooster antibody titres, since the response can be impaired by factors such as ethnicity and substance use [49]. Further prospective randomized studies in endemic areas are therefore warranted to establish the optimal timing and number of booster doses of hepatitis B vaccine in children and adolescents.

DECLARATION OF INTEREST

None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wong VCW, et al. Prevention of the HBsAg carrier state in newborn infants of mothers who are chronic carriers of HBsAg and HbeAg by administration of hepatitis-B vaccine and hepatitis-B immunoglobulin. Double-blind randomised placebo-controlled study. Lancet 1984; i: 921–926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beasley RP, et al. Prevention of perinatally transmitted hepatitis B virus infections with hepatitis B immune globulin and hepatitis B vaccine. Lancet 1983; ii: 1099–1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beasley RP, et al. HBIG prophylaxis for perinatal HBV infections – final report of the Taiwan trial. Developments in Biological Standardization 1983; 54: 363–375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leung NW. Patterns of viral hepatitis in Hong Kong. British Journal of Hospital Medicine 1997; 58: 166–169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stevens CE, et al. Vertical transmission of hepatitis B antigen in Taiwan. New England Journal of Medicine 1975; 292: 771–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yeoh EK. Hepatitis B vaccination – Who should be vaccinated? [Editorial]. Journal of the Hong Kong Medical Association 1987; 39: 208–209. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Assad S, Francis A. Over a decade of experience with a yeast recombinant hepatitis B vaccine. Vaccine 1999; 18: 57–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nair PV, et al. Efficacy of hepatitis B immune globulin in prevention of perinatal transmission of the hepatitis B virus. Gastroenterology 1984; 87: 293–298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee PI, et al. A follow-up study of combined vaccination with plasma-derived and recombinant hepatitis B vaccines in infants. Vaccine 1995; 13: 1685–1689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee C, et al. Hepatitis B prophylaxis for newborns of hepatitis B surface antigen-positive mothers Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2004. Issue 2. Art. No. CD004790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kwan LC, Ho YY, Lee SS. The declining HbsAg carriage rate in pregnant women in Hong Kong. Epidemiology and Infection 1997; 119: 281–283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lok ASF. Hepatitis B vaccination in Hong Kong. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology 1993: 8: S27–S29. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Department of Health, Hong Kong. Surveillance of viral hepatitis in Hong Kong – 2006 update report (http://www.info.gov.hk/hepatitis/doc/hepsurv06.pdf). Accessed 30 August 2012.

- 14.The Scientific Working Group on Viral Hepatitis Prevention. Recommendations on hepatitis B Vaccination Regimens in Hong Kong – Consensus of the scientific working group on viral hepatitis prevention. Hong Kong: Department of Health, 1998, p. 9. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee SS. Hepatitis B vaccination programme in Hong Kong. Public Health & Epidemiology Bulletin 1993; 2: 9–12. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leung CW. Proceedings of state of Asian children – immunization. Hong Kong Journal of Paediatrics (New Series) 1999; 4: 9–62. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yeoh EK, Young B, Chan YY. Determinants of immunogenicity and efficacy of hepatitis B vaccine in infants. In: Hollinger FB, Lemon SM, Margolis HS, eds. Viral Hepatitis and Liver Disease. Baltimore, Maryland: Williams & Wilkins, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gabbuti A, et al. Long-term immunogenicity of hepatitis B vaccination in a cohort of Italian healthy adolescents. Vaccine 2007; 25: 3129–3132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hammitt LL, et al. Hepatitis B immunity in children vaccinated with recombinant hepatitis B vaccine beginning at birth: a follow-up study at 15 years. Vaccine 2007; 25: 6958–6964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Poovorawan Y, et al. Long-term hepatitis B vaccine in infants born to hepatitis B e antigen positive mothers. Archives of Diseases in Childhood (Fetal and Neonatal Edition) 1997; 77: F47–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Poovorawan Y, et al. Long term efficacy of hepatitis B vaccine in infants born to hepatitis B e antigen-positive mothers. Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal 1992; 11: 816–821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alfaleh FZ, et al. Long-term protection of hepatitis B vaccine 18 years after vaccination. Journal of Infection 2008; 57: 404–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liao SS, et al. Long-term efficacy of plasma-derived hepatitis B vaccine: a 15-year follow-up study among Chinese children. Vaccine 1999; 17: 2661–2666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ni YH, et al. Hepatitis B virus infection in children and adolescents in a hyperendemic area: 15 years after mass hepatitis B vaccination. Annals of Internal Medicine 2001; 135: 796–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chan OK, et al. Correlation between maternal hepatitis B surface antigen carrier status with social, medical and family factors in an endemic area – have we overlooked something? Infection 2011; 39: 419–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zanetti AR, et al. Long-term immunogenicity of hepatitis B vaccination and policy for booster: an Italian multicentre study. Lancet 2005; 366: 1379–1384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lu CY, et al. Waning immunity to plasma-derived hepatitis B vaccine and the need for boosters 15 years after neonatal vaccination. Hepatology 2004; 40: 1415–1420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McMahon BJ, et al. Antibody levels and protection after hepatitis B vaccination: results of a 15-year follow-up. Annals of Internal Medicine 2005; 142; 333–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Su FH, et al. Waning-off effect of serum hepatitis B surface antibody amongst Taiwanese university students: 18 years post-implementation of Taiwan's national hepatitis B vaccination programme. Journal of Viral Hepatitis 2008; 15: 14–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ni YH, et al. Two decades of universal hepatitis B vaccination in Taiwan: impact and implication for future strategies. Gastroenterology 2007; 132: 1287–1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lin DB, et al. Immune status in preschool children born after mass hepatitis B vaccination program in Taiwan. Vaccine 1998; 16: 1683–1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gold Y, et al. Decreased immune response to hepatitis B eight years after routine vaccination in Israel. Acta Paediatrica 2003; 92: 1158–1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miñana JS, et al. Hepatitis B vaccine immunoresponsiveness in adolescents: a revaccination proposal after primary vaccination. Vaccine 1996; 14: 103–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bialek SR, et al. Persistence of protection against hepatitis B virus infection among adolescents vaccinated with recombinant hepatitis B vaccine beginning at birth. A 15-year follow-up study. Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal 2008; 27: 881–885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Department of Health, Hong Kong. Rubella in Hong Kong Public Health and Epidemiology Bulletin 1995; 4: 17–20. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chuang SK, et al. Mass measles immunization campaign: experience in the Hong Kong Special Administration Region of China. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 2002; 80: 585–591. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lao TT, et al. Chronic hepatitis B virus infection and rubella susceptibility in pregnant women. Journal of Viral Hepatitis 2010; 17: 737–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Su FH, et al. Seroprevalence of hepatitis-B infection amongst Taiwanese university students 18 years following the commencement of a national hepatitis-B vaccination program. Journal of Medical Virology 2007; 79: 138–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Samandari T, et al. Differences in response to a hepatitis B vaccine booster dose among Alaskan children and adolescents vaccinated during infancy. Pediatrics 2007; 120: e373–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chien YC, et al. Nationwide hepatitis B vaccination program in Taiwan: effectiveness in the 20 years after it was launched. Epidemiology Review 2006; 28: 126–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chang MH, et al. for the Taiwan Children HCC Study Group. Prevention of hepatocellular carcinoma by universal vaccination against hepatitis B virus: the effect and problems. Clinical Cancer Research 2005; 11: 7953–7957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Villarejos VM, et al. A. Role of saliva, urine and feces in the transmission of type B hepatitis. New England Journal of Medicine 1974; 291: 1375–1378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Scott RM, et al. Experimental transmission of hepatitis B virus by semen and saliva. Journal of Infectious Diseases 1980; 142: 67–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Inaba N, et al. Sexual transmission of hepatitis B surface antigen infection of husband by HbsAg carrier-state wives. British Journal of Venereal Diseases 1979; 55: 366–368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Heng BH, et al. Prevalence of hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection in Singapore men with sexually transmitted diseases and HIV infection: role of sexual transmission in a city state with intermediate HBV endemicity. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 1995; 49: 309–313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ko YC, et al. Female to male transmission of hepatitis B virus between Chinese Spouses. Journal of Medical Virology 1989; 27: 142–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang CW, et al. Long-term follow-up of hepatitis B surface antibody levels in subjects receiving universal hepatitis B vaccination in infancy in an area of hyperendemicity: Correlation between radioimmunoassay and enzyme immunoassay. Clinical and Diagnostic Laboratory Immunology 2005; 12: 1442–1447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.John TJ, Cooksley G, on behalf of the Steering Committee for the Prevention and Control of Infectious Diseases in Asia. Review. Hepatitis B vaccine boosters: Is there a clinical need in high endemicity populations? Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology 2005; 20: 5–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang LY, Lin HH. Ethnicity, substance use, and response to booster hepatitis B vaccination in anti-HBs-seronegative adolescents who had received primary infantile vaccination. Journal of Hepatology 2007; 46: 1018–1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]