SUMMARY

This cohort study examines trends in pneumonia mortality in Finland and the effects of a WHO recommendation restricting the registering of pneumonia as the underlying cause of death (COD) for several chronic diseases. All cases having pneumonia in any COD fields in 2000–2008 were extracted from the COD statistics. We examined trends in underlying-cause pneumonia mortality where pneumonia was also the immediate COD. Results are presented as age-specific and age-standardized rates. In the study period 2000–2008, there were 90 626 deaths with pneumonia in COD fields, while the underlying-cause pneumonia mortality rate decreased from 32 to 6/100 000 person-years. Immediate-cause pneumonia was less often chosen as underlying-cause towards 2008 suggesting an effect from changing coding practices. Changes in coding practices need to be considered when comparing different countries or time periods in pneumonia mortality.

Key words: Mortality statistics, pneumonia

INTRODUCTION

Pneumonia is an important public health problem in all Western countries. Community-acquired pneumonia is the most common infectious cause of death (COD) in the USA [1]. Pneumonia hospitalizations have increased in both the USA and England [2, 3]. Demographic changes and an increase in comorbid illnesses have had an effect. In Finland about 1% of the adult population are annually diagnosed with pneumonia, with about 10% of pneumonia sufferers dying [4]. Internationally, the figures vary between 5% and 15% depending on patient group [4–8].

A WHO recommendation was introduced in the mid-2000s restricting the use of pneumonia as the underlying COD in connection with several chronic diseases. In these cases the chronic disease in question should be selected as the underlying cause [9]. It was implemented in Finland in 2005–2006. In EU countries pneumonia mortality varied up to tenfold in the early 2000s [10]: pneumonia mortality varied from about 6/100 000 in Greece to almost 60/100 000 in Ireland in 2000. We found no comparative studies on pneumonia incidence, but classification differences for pneumonia probably play a role. Furthermore, pneumonia mortality has decreased since 2000 in most EU countries, especially in Finland, Estonia and Ireland, suggesting differences in the recording of COD.

This study examines trends in pneumonia mortality in Finland and the effects of implementing the WHO recommendation on pneumonia mortality during the period 2000–2008. We examined both pneumonia as the underlying COD and the immediate cause, with analyses of the trends in underlying-cause mortality where pneumonia was the immediate COD.

METHODS

Data were compiled from the COD statistics. All cases having pneumonia in any of the COD fields (ICD-10 classes J12–J18) during 2000–2008 were extracted. COD statistics include underlying COD (provided by the doctor issuing the death certificate, with EU and WHO recommendations applied), immediate COD, contributory causes and intermediate COD (leading from underlying to immediate COD). All these fields are completed by the doctor issuing the death certificate.

The COD statistics also included individual-level information on sex, age at death, and region of residence (Appendix). We used hospital districts for region of residence. The Finnish legislation divides the country into 20 hospital districts (excluding Åland islands) which are responsible for providing municipal secondary-care services [11].

We examined annual trends in pneumonia as the underlying cause where the immediate COD was pneumonia in different age groups for men and women separately and calculated age-standardized rates. The European standard population was used when calculating age-standardized rates. We analysed regional variation in pneumonia deaths as the underlying cause among immediate-cause pneumonia deaths at the hospital district level with a multilevel logistic regression model adjusting for sex, age group and time period. The Wald test was used to assess the significance of regional variation at the hospital district level. We also examined developments in underlying COD in the largest ICD-10 principal groups, where the immediate cause was coded as pneumonia. The study protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the National Centre for Health and Welfare.

RESULTS

During 2000–2008, deaths with pneumonia in any of the COD fields numbered 90 626, while the age-standardized annual mortality rate decreased from 32 to 6/100 000 person-years. Table 1 presents the rates of pneumonia in different fields of COD statistics per 100 000 for the study period. Since few changes were found in the annual numbers for contributory causes after 2003 and intermediate COD for the whole period, we focused on underlying and immediate COD. A trend of decreasing rates of pneumonia as the immediate COD was found from 2000 to 2004, but after 2005 the figures remained unchanged. However, an especially large decrease was found when examining the underlying COD. The decrease was largest before 2005–2006, but continued throughout the study period. The decline was almost 80% during the whole study period. For immediate COD, the decline was more modest, at around 25%.

Table 1.

Age-standardized* rates for pneumonia mortality per 100 000 in 2000–2008 in Finland

| n | All fields, rate (95% CI) | Underlying cause, rate (95% CI) | Immediate cause, rate (95% CI) | Contributory cause, rate (95% CI) | Intermediate cause, rate (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000–2002 | 32 301 | 143 (141–144) | 32 (31–33) | 126 (125–128) | 13 (13–14) | 2 (2–2) |

| 2003–2004 | 21 217 | 134 (132–136) | 24 (23–24) | 118 (116–120) | 13 (12–14) | 2 (2–2) |

| 2005–2006 | 18 202 | 109 (108–111) | 9 (9–10) | 94 (92–95) | 13 12–13) | 2 (2–2) |

| 2007–2008 | 18 906 | 107 (106–109) | 6 (6–7) | 91 (89–92) | 13 (13–14) | 2 (2–3) |

CI, Confidence interval.

European standard population was used in calculation of age-standardized rates.

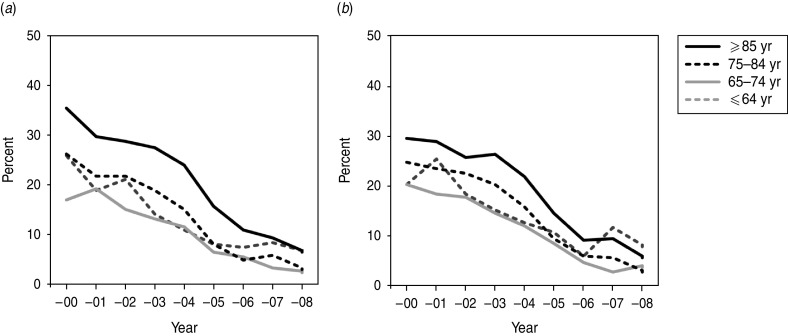

Figure 1 presents trends in age-specific rates for underlying-cause pneumonia mortality when the immediate COD was pneumonia from 2000 to 2008 for men and women separately. For men, the proportion diminished in all age groups but the decline was especially large in those aged ⩾85 years. Results were similar for women, but less marked.

Fig. 1.

Age-specific trends in the proportion of underlying-cause pneumonia (%) of immediate-cause pneumonia in (a) men and (b) women in Finland, 2000–2008.

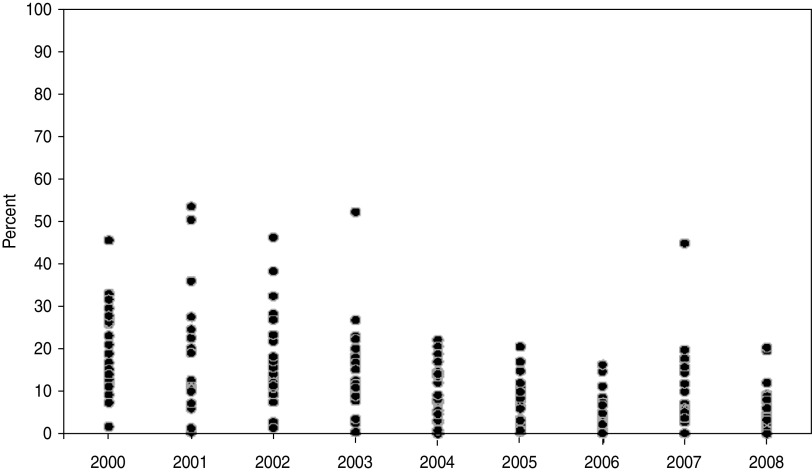

Figure 2 presents the variation in underlying-cause pneumonia mortality when the immediate COD was pneumonia by hospital district in 2000–2008, each dot in each year represents a hospital district. The variation at hospital district level was also statistically significant after controlling for population structure (P = 0·002). Large variation was detected in 2000 in underlying-cause pneumonia mortality when the immediate COD was pneumonia. While the overall proportion decreased, differences between hospital districts also decreased.

Fig. 2.

Trends in hospital district variation in the proportion of underlying-cause pneumonia (%) of immediate-cause pneumonia controlling for sex and age in Finland, 2000–2008.

We additionally examined a development in underlying COD in the largest ICD-10 principal groups where the immediate cause was coded as pneumonia. Our results suggest that changes in coding practices in pneumonia also affect numbers of other COD. Especially principal group G, mainly Alzheimer's disease (G30) and other degenerative diseases of the nervous system (G31) were selected more often as the underlying COD towards the end of the study period. Simultaneously, dementia (F01, F03) was less often coded as the underlying cause. Principal group for cardiovascular disease underwent the following changes: later in the study period, chronic ischaemic heart disease (I25) was more often chosen as the underlying COD while myocardial infarction (I21) and stroke (I63) were less likely to be selected.

DISCUSSION

We found a large decrease in pneumonia mortality especially in older age groups from 2000 to 2008, when a new WHO recommendation in regard to several chronic diseases restricted the use of pneumonia as the underlying COD. We further found increasing numbers of some chronic conditions as underlying cause when the immediate COD was pneumonia.

Similar results were reported for elderly US patients: case fatality for pneumonia decreased by 30% in the population aged ⩾65 years between 1987 and 2005, although its incidence rate had increased up to 1999 [12]. A possible explanation suggested by the US authors is an increase in the use of pneumococcus and influenza vaccine and the wider use of guideline-based antibiotics. Decrease of immediate-cause pneumonia mortality in Finland suggests that the improved efficiency of pneumonia care may explain some of our findings. However, vaccines are not a likely explanation. In Finland coverage of pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccines has traditionally been low and conjugate vaccines were included in the vaccination programmes only in 2010 [13].

The decline in pneumonia mortality is consistent with the decline in all-cause mortality in Finland in the 1990s and 2000s [14]. Nevertheless, much of the apparent decline in pneumonia mortality appears connected to changes in pneumonia coding practices. The underlying-cause pneumonia mortality in 2007–2008 was about 20% that of the early 2000s, whereas immediate-cause pneumonia mortality declined by one quarter during the study period. Large but declining differences were found regionally in underlying-cause pneumonia mortality when the immediate cause was pneumonia. Differences appear to be independent of regional differences in the population structure. Changes in coding practices also appear to affect mortality to Alzheimer's disease and other degenerative neurological diseases, and also chronic ischaemic heart disease, which were more often chosen as the underlying COD later in the study period. Similar results concerning changes in classification rules for underlying COD have been reported earlier from England for the period 1984–1993 [15]. A 1984 rule specified that certain diseases which could be considered a mode of dying rather than the COD should not be coded as the underlying COD. Goldacre and colleagues [15] reported a large decrease in underlying-cause mortality due to pneumonia, heart failure and thromboembolism after the implementation of this rule. In line with these results, our findings suggest that examining underlying cause alone will be misleading for time trends or international comparisons.

The rule changes in coding practices need to be considered when comparing different countries or time periods in pneumonia mortality, as well as in other chronic diseases, since some are now used instead as the underlying COD. Our results also indicate that similar to earlier studies concerning the burden of specific disease, the use of underlying cause only will underestimate the burden of disease [15–17]. Both underlying and immediate cause need to be considered, and in some diseases, also contributory COD are needed to evaluate the mortality burden of a specific disease.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The study was financially supported by the Academy of Finland (project no. 133793). The Academy had no involvement in the study's design, data collection, findings or decision to publish.

APPENDIX.

Characteristics of the study data

| 2000–2002 | 2003–2004 | 2005–2006 | 2007–2008 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Person-years | (%) | Person-years | (%) | Person-years | (%) | Person-years | (%) | |

| Men | 7 510 695 | (48·8) | 5 045 190 | (48·9) | 5 080 460 | (48·9) | 5 125 570 | (49·0) |

| Age (years) | ||||||||

| ⩽64 | 6 603 799 | (87·9) | 4 402 654 | (87·3) | 4 401 150 | (86·6) | 4 411 900 | (86·1) |

| 65–74 | 580 522 | (7·7) | 400 228 | (7·9) | 414 081 | (8·2) | 428 170 | (8·4) |

| 75–84 | 269 604 | (3·6) | 202 924 | (4·0) | 221 992 | (4·4) | 236 452 | (4·6) |

| ⩾85 | 56 770 | (0·8) | 39 384 | (0·8) | 43 237 | (0·9) | 49 047 | (1·0) |

| Number of deaths | 15 361 | 10 429 | 9369 | 9595 | ||||

| Pneumonia deaths | 3400 | 1720 | 755 | 530 | ||||

| Women | 7 877 842 | (51·2) | 5 276 128 | (51·1) | 5 305 576 | (51·1) | 5 343 224 | (51·0) |

| Age (years) | ||||||||

| ⩽64 | 6 438 346 | (81·7) | 4 291 428 | (81·3) | 4 290 698 | (80·9) | 4 301 655 | (80·5) |

| 65–74 | 731 821 | (9·3) | 489 329 | (9·3) | 494 581 | (9·3) | 503 242 | (9·4) |

| 75–84 | 527 550 | (6·7) | 370 606 | (7·0) | 386 410 | (7·3) | 390 416 | (7·3) |

| ⩾85 | 180 125 | (2·3) | 124 765 | (2·4) | 133 887 | (2·5) | 147 911 | (2·8) |

| Number of deaths | 16 940 | 10 788 | 8833 | 9311 | ||||

| Pneumonia deaths | 4011 | 2081 | 816 | 555 | ||||

DECLARATION OF INTEREST

Ilmo Keskimäki has on occasion advised the Finnish Ministry of Health and Social Affairs on matters relating to health policy and services. Regardless of the findings of this study, the outcome of this research would form part of that advice.

REFERENCES

- 1.Armstrong GL, Conn LA, Pinner RW. Trends in infectious disease mortality in the United States during the 20th century. Journal of the American Medical Association 1999; 281: 61–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Christensen KL, et al. Infectious disease hospitalizations in the United States. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2009; 49: 1025–1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Trotter CL, et al. Increasing hospital admissions for pneumonia, England. Emerging Infectious Diseases 2008; 14: 727–733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jokinen C, et al. Incidence of community-acquired pneumonia in the population of four municipalities in Eastern Finland. American Journal of Epidemiology 1993; 137: 977–988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fine MJ, et al. Prognosis and outcomes of patients with community-acquired pneumonia. A meta-analysis. Journal of the American Medical Association 1996; 275: 134–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mortensen EM, et al. Assessment of mortality after long-term follow-up of patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2003; 37: 1617–1624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaplan V, et al. Pneumonia: still the old man's friend? Archives of Internal Medicine 2003; 163: 317–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thomsen RW, et al. Rising incidence and persistently high mortality of hospitalized pneumonia: a 10-year population-based study in Denmark. Journal of Internal Medicine 2006; 259: 410–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Statistics Finland. Causes of death in 2005 [in Finnish]. Helsinki: Tilastokeskus, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 10.European Mortality Database (MDB). (http://data.euro.who.int/hfamdb/). Accessed 29 November 2011.

- 11.Vuorenkoski L, Mladovsky P, Mossialos E. Finland: Health system review. Health Systems in Transition 2008; 10(4): 1–168 (published by WHO European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ruhnke GW, et al. Marked reduction in 30-day mortality among elderly patients with community-acquired pneumonia. American Journal of Medicine 2011; 124: 171–178.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aromaa A, Koskinen S (eds). Health and functional capacity in Finland. Baseline results of the Health 2000 health examination survey. Helsinki, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tarkiainen L, et al. Trends in life expectancy by income from 1988 to 2007: decomposition by age and cause of death. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health Online First. Published online: 4 March 2011. doi: 10.1136/jech.2010.123182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldacre MJ, et al. Trends in mortality rates comparing underlying-cause and multiple-cause coding in an English population 1979–1998. Journal of Public Health Medicine 2003; 25: 249–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Manderbacka K, et al. The burden of diabetes mortality in Finland 1988–2007 – a brief report. BMC Public Health 2011; 11: 747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herttua K, Mäkelä P, Martikainen P. Differential trends in alcohol-related mortality: a register-based follow-up study in Finland in 1987–2003. Alcohol and Alcoholism 2007; 42: 456–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]