Abstract

Essential oils (EO) are aromatic compounds from the plant secondary metabolism. Melaleuca alternifolia EO is well known for its medicinal properties and promising use as an antimicrobial agent. Pythiosis is a difficult-to-treat and emerging disease caused by the oomycete Pythium insidiosum. This study evaluated a nanoemulsion formulation of M. alternifolia (NEMA) in topical and intralesional application to treat experimental pythiosis. Dermal toxicity tests were performed on M. alternifolia EO in Wistar rats. Pythiosis was reproduced in rabbits (n = 9) that were divided into groups: group 1 (control), cutaneous lesions with daily topical application of a non-ionizable gel-based formulation and intralesional application of sterile distilled water every 48 h; group 2 (topical formulation), lesions treated daily with topical application of a non-ionizable gel-based formulation containing 5 mg/ml of NEMA; and group 3 (intralesional formulation), lesions treated with NEMA at 5 mg/ml in aqueous solution applied intralesionally/48 h. The animals were treated for 45 days, and the subcutaneous lesion areas were measured every 5 days. M. alternifolia EO showed no dermal toxicity. The lesion areas treated with intralesional NEMA reduced at the end of treatment, differing from groups 1 and 2 (P < 0.05). In the topically treated group, the lesion areas did not differ from the control group, although the number of hyphae significantly reduced (P < 0.05). Under the experimental conditions of this study, the NEMA formulations presented a favorable safety profile. However, further studies are required to evaluate if this safety applies to higher concentrations of NEMA and to validate its use in clinical pythiosis.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s42770-022-00720-6.

Keywords: Nanoemulsion, Essential oils, Topic, Intralesion, Pythium insidiosum

Introduction

Essential oils (EOs) are natural aromatic compounds originating from the secondary metabolism of plants, and EOs are known to protect against pathogens and herbivores [1]. These compounds are recognized for their medicinal properties, especially their antimicrobial potential, making them attractive products for the pharmaceutical industry since the number of drug-resistant microorganisms has increased at an alarming rate [1, 2]. Moreover, M. alternifolia EO has notorious medicinal properties, including activity against resistant bacteria that cause skin infections [3], antifungal activity against dermatophytes [4], dental application against biofilm formation and anti-inflammatory [5], antitumor properties [6], and anesthetic [7]. Additionally, it can act as a leukocyte activator against Candida krusei [8].

Mammals can be infected with Pythium insidiosum, which is an oomycete that is morphologically similar to fungi. Nonetheless, according to its taxonomic classification, P. insidiosum is closer to diatom algae than to fungi [9]. Pythiosis is a severe and life-threatening disease in veterinary and human medicine [10]. In fact, this disease is economically relevant in equine reproduction among domestic species, with Brazil having the highest number of reported cases [11]. However, pythiosis in humans is frequent in Asia, especially in Thailand, with high lethality rates [12]. This illness is known for its poor prognosis, and the therapeutic protocols available, including surgery, immunotherapy, and antifungal drugs, do not always lead to the cure of the disease.

Due to the constant therapeutic failures and lack of effective treatment, recent studies have sought to develop new treatments by evaluating anti-Pythium insidiosum activity using drugs with antibacterial and antifungal activity [13–19], antiparasitic properties [20], and EOs from medicinal plants and natural compounds [21–25].

Valente et al. [23] demonstrated that M. alternifolia EO has efficient in vitro anti-Pythium insidiosum activity in its pure formulation and nanoemulsion, although the oil nanoemulsion formulation had superior antimicrobial activity against the oomycete.

Fonseca et al. [21] evaluated a gel formulation containing EOs in the topical treatment of experimental pythiosis in rabbits and reported promising results using a Mentha piperita and Origanum vulgare EO combination. Recently, Valente et al. [26] observed that both the non-ionic gel-based formulation containing topically applied biogenic silver nanoparticles and the aqueous formulation applied inside the cutaneous lesions of experimental pythiosis in rabbits reduced lesion size.

Given the above, the present study sought to evaluate the activity of a M. alternifolia nanoemulsion (NEMA) in the topical formulation and intralesionally applied to treat experimental pythiosis.

Materials and methods

Melaleuca alternifolia nanoemulsion

M. alternifolia EO was obtained commercially (Laszlo Aromatherapy Ltd, Belo Horizonte, Brazil), and the major components consisted of terpinene-4-ol (40–52%), γ-terpinene (6–20%), α-terpinene (11–16%), 1.8 cineole (1–2%), terpineol (5%), limonene (3–4%), pinene (3–5%), and terpinolene (1–5%). The nanoemulsion containing 1% of M. alternifolia (10,000 μg/ml) was produced using the spontaneous emulsification method in the ~200 nm range, negative zeta potential, and polydispersity index below 0.25 [27, 28].

Dermal toxicity test

Thirty 60-day-old Wistar rats (Rattus norvegicus) of both sexes were used and kept in the Central Animal Hospital of the Federal University of Pelotas (UFPel) under controlled temperature (22 ± 1 °C) and relative humidity (60–70%) with water and feed ad libitum and a 12-h light/dark cycle. The animals were allocated into three groups of ten animals (five males and five females in separate cages) and acclimated for 5 days. The control group animals (n = 10) were treated daily with topical application of a non-ionic gel-based formulation without active ingredients. The treated groups received daily topical applications of a non-ionic gel formulation containing 2.130 μg/ml (n = 10) and 5.000 μg/ml (n = 10), as determined by the protocol for dermal toxicity tests [29].

On day zero, the animals were weighed and shaved in the dorsal region, not exceeding 10% of the total body area. The shaved area received a daily dermal application (1 g) of the formulations for 28 days. Before each application, the treated region was evaluated by considering the following parameters: weight loss, behavioral changes, inflammation, edema, or hyperemia. After this period, the animals were euthanized according to standard protocols, and representative tissue fragments of the application site were sent for histopathological analysis.

Pythiosis experimental reproduction and treatment

Nine 90-day-old female rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus) were used for the experimental reproduction of pythiosis. The animals were kept in the animal facilities at UFPel, in individual cages with controlled room temperature (25 °C), adequate hygiene and light, water ad libitum, and food according to their body weight. For the experimental reproduction of the disease, a 1-ml induction medium containing ~32,500 viable P. insidiosum zoospores was inoculated subcutaneously in the right dorsal region, according Pereira et al [13]. The animals were clinically evaluated daily to monitor lesion development, and 25 days after inoculation, the animals developed subcutaneous nodules. When the lesions developed, the rabbits were randomly separated into groups of three animals; the lesion area was shaved, before starting the treatment. Group 1 (control) received a daily topical application (5 g) of a non-ionic gel-based formulation in the lesion area and intralesionally applied sterile distilled water (1 ml) every 48 h. Group 2 was treated daily with a gel-based formulation (5 g) containing 5 mg/ml of NEMA, and group 3 received NEMA in an aqueous solution (1 ml) at a concentration of 5 mg/ml intralesionally applied every 48 h. Following the method previously described by Valente et al. [26], the gel formulation was applied to the lesion surface, and circular finger movements were performed until the gel was completely absorbed. In intralesion route, 1 ml of sterile distilled water or 1 ml of aqueous NEMA solution was applied to the lesion using a BD Ultra-Fine insulin syringe.

The clinical presentation of the animals and lesion progression were observed daily throughout the experiment. The lesion area was measured every 5 days using a digital caliper (150 mm Digital Caliper, Jomarca). At the end of the experiment (45 days after the treatment began), the animals were euthanized according to standard protocols. For histopathological analysis, fragments of subcutaneous lesions and organs (the lung, liver, spleen, kidneys) were collected and fixed in a 10% formalin solution, routinely processed, and stained with hematoxylin-eosin (HE) and methenamine silver (Grocott). For each animal group, hyphae impregnated with Grocott were quantified by counting in ten microscopic fields that were randomly selected. All animal experiments were previously approved by the UFPel Animal Ethics and Experimentation Committee.

Hematological and biochemical profiles

The hematological profile of the inoculated animals was assessed by collecting blood samples before starting the treatments and every 15 days until the end of the experiment. The erythrogram and leukogram were performed using an automatic hematological analyzer (Sysmex pocH - 100iVDiff®5, Kobe, Japan). Blood smears were taken to evaluate the erythrocyte morphology and differential leukocyte counts. The enzymatic profile of alanine aminotransferase aspartate aminotransferase, creatinine, urea, alkaline phosphatase, and gamma-glutamyltransferase were determined by biochemical kits, and readings were acquired using an equipment Cobas c111® analyzer, Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, USA.

Statistical analysis

The subcutaneous nodules of the animals in each group were measured every 5 days. After each measurement, the lesion width and height were measured, and the averages were calculated for each group [26]. These data were submitted to normality and homoscedasticity tests. When these hypotheses were satisfactory, analysis of variance and F test was performed (5% significance level). The responses were also modeled according to the measurement data for each treatment using a third-order polynomial function. In the regression analysis, the models were chosen based on the significance of the linear and quadratic coefficients using the Student’s t test (5% significance level). The linear regression equations obtained for the different treatments were compared using the contrast test between the regression coefficients. Given the lack of data normality, the number of hyphae recorded in the control group and NEMA-treated groups was compared using the Kruskal-Wallis test. When differences were found, the means were compared using the Bonferroni test. The analyses were performed using SPSS version 9.4 [30].

Results

Dermal toxicity

The animals presented body weight varying from 240 to 300 g during the evaluation period, and no behavioral changes or weight loss were observed. The application sites did not show any signs of inflammation, edema, or hyperemia. The histopathological analysis also did not show any differences in tissue composition.

Treatment of experimental pythiosis

All animals developed palpable subcutaneous nodules 25 days after P. insidiosum zoospore inoculation.

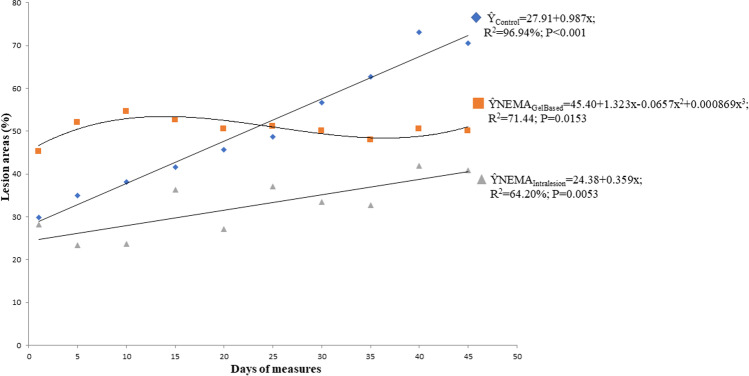

During the experiment, it was observed that the inoculated rabbits presented lesions that varied in size according to the days evaluated (Fig. 1 and Supporting information — Tables S1, S2, and S3). The average and the range of nodules size for each group of the treatment are summarized in Table 1. In the statistical analysis, group 3 differed from the control group (group 1) and group 2 (P < 0.05). In turn, group 2 did not differ from the control group (P = 0.05) (Table 2). The regression analysis of the lesions showed that group 1 adjusted to the increasing linear regression, with a 0.987% increment in lesions each day after the treatment began (Ŷ = 27.91 + 0.987x; R2 96.94%; P < 0.001). Group 3 also adjusted to the increasing linear regression (Ŷ = 24.38 + 0.359x; R2 64.20%; P = 0.0053), with a 0.359% increase in lesions each day of the treatment. Nonetheless, the lesions of the rabbits in group 2 showed a cubic behavior (Ŷ = 45.40 + 1.323x-0.0657x2 + 0.000869x3; R2 71.44; P = 0.0153) with the largest lesion size on the 21st day and the smallest size on the 36th day after starting treatment (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Subcutaneous lesion areas in rabbits inoculated experimentally with zoospores of Pythium insidiosum (control

) and treated with a gel-based formulation of NEMA (

) and treated with a gel-based formulation of NEMA (

) or NEMA aqueous solution intralesion (

) or NEMA aqueous solution intralesion (

)

)

Table 1.

Average and range of nodules size of each group of rabbits inoculated experimentally with zoospores of Pythium insidiosum and treated with a gel-based formulation of NEMA* or NEMA aqueous solution intralesion

| Day of treatment (average of nodules size/mm2) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental group | 1st | 5th | 10th | 15th | 20th | 25th | 30th | 35th | 40th | 45th | Range of nodules size (mm2)# |

| Group 1 (Control) | 29.79 | 35.05 | 38.10 | 41.66 | 45.72 | 48.77 | 56.64 | 62.74 | 73.15 | 70.61 | 29.79–73.15 |

| Group 2 (NEMA gel-based formulation) | 45.21 | 52.07 | 54.61 | 52.58 | 50.55 | 51.05 | 50.04 | 48.01 | 50.55 | 50.04 | 45.21–54.61 |

| Group 3 (NEMA intralesion) | 28.19 | 23.37 | 23.62 | 36.32 | 27.18 | 37.08 | 33.53 | 32.77 | 41.91 | 40.90 | 23.37–41.91 |

*Nanoemulsion formulation of Melaleuca alternifolia. # The range considered the day of the smallest and largest measurement of nodules size during the treatment period

Table 2.

Means of the size of the lesions and the number of hyphae of each group of rabbits inoculated experimentally with zoospores of Pythium insidiosum and treated with a gel-based formulation of NEMA* or NEMA aqueous solution intralesion

| Experimental group | Average lesion size | Average number of hyphae |

|---|---|---|

| Group 1 (control) | 50.223a# | 67.0a |

| Group 2 (NEMA gel-based formulation) | 50.471a | 18.2b |

| Group 3 (NEMA aqueous solution intralesion) | 32.487b | 33.7b |

*Nanoemulsion formulation of Melaleuca alternifolia. #Means followed by different letters in the columns differ statistically (P < 0.05)

The cut surface of the subcutaneous nodules was hardened, multilobulated, pinkish-white, highly vascularized in all infected animals, and, in some lesions, there was purulent exudate. In HE, histopathological analysis revealed multifocal and coalescent areas of necrosis separated by inflammatory polymorphonuclear infiltration (predominantly eosinophils), lymphocytes, macrophages, foreign body-like giant cells, and Langerhans cells. In the areas of necrosis and inside some giant cells, negative tubuliform images consistent with P. insidiosum hyphae were observed, which were surrounded by an intense eosinophilic reaction (Splendore-Hoeppli reactions). Thick, brown-walled hyphae, sparsely septate and irregularly branched, concentrated in the areas of necrosis, were noted in the Grocott.

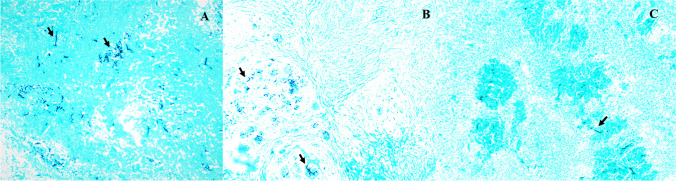

Despite similar histological aspects of the lesions in all experimental groups, the number of hyphae in the control group (group 1) was higher and dispersed throughout the Grocott stain tissue (Fig. 2A). In groups 2 (Fig. 2B) and 3 (Fig. 2C), there were fewer hyphae, which were concentrated in the areas of necrosis and thus differed from the control group (P < 0.05) (Table 1). The analysis of the pre-infection hematological profile of the animals showed normal hematological parameters, according to Spinelli et al [31]. The treated animals had hematological and biochemical patterns similar to the control group.

Fig. 2.

The subcutaneous tissue of rabbits experimentally inoculated with Pythium insidiosum zoospores and treated with NEMA. P. insidiosum hyphae with thick, brown, and irregularly branched walls (arrows). A Control group: the hyphae are dispersed in the field. B Gel-based NEMA topical formulation. C Aqueous formulation of intralesionally administered NEMA. The hyphae are concentrated in the areas of necrosis, and there are fewer hyphae in the tissues. Grocott methenamine silver (GMS) stain. 10× Lens

Throughout the treatment, the parameters of red blood cells, hemoglobin, fibrinogen, and basophil remained within the parameters established [31, 32] until the end of the experiment. Mean corpuscular hemoglobin and the number of lymphocytes continued relatively below these parameters; however, these results were similar to the animals in the control group. The leukogram showed that the average total, segmented leukocytes, monocytes, and eosinophils had numbers above the parameters considered normal for the species. Total protein determination revealed average values, and the biochemical profile remained within the standards established [31, 33].

Discussion

Melaleuca alternifolia EO was first used for medicinal purposes by Australian tropical medicine. Its relevant antimicrobial properties sparked interest, leading to its medical applications worldwide [34]. Research on the use of therapeutic protocols with topical/local substances to treat cutaneous pythiosis is still incipient. Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of two formulations in the treatment of experimental pythiosis: a topical formulation containing 5 mg/ml of NEMA versus an intralesional administration of NEMA at a concentration of 5 mg/ml. Our findings demonstrated that the intralesional administration contributed significantly to regression of the size of the skin lesions (P < 0.05) when compared to the topical administration. Nevertheless, the topical gel-based formulation did not differ from the control group (P > 0.05), although it reduced the number of hyphae in the tissues.

The antimicrobial mechanism of EOs is explained by the damage that these compounds cause in organelles and cellular components of microorganisms [1]. Swamy et al. [35] reported that the EOs may irreversibly damage the fungal cell membrane, leading to the coagulation of cellular components. Furthermore, these authors suggested that EOs can penetrate the fungal cell wall, increasing its permeability and changing electron flow, leading to mitochondrial membrane disintegration and fungal cell apoptosis [35]. In addition, Kong et al. [36] reported that M. alternifolia EO caused the appearance of breakpoints in the hyphae and cytoplasm leakage when administered in Aspergillus ochraceus cells.

Previously, Valente et al. [23] performed in vitro tests to demonstrate the action of M. alternifolia EO in free form and nanoemulsion on P. insidiosum isolates. The authors observed that the nanoemulsion inhibited P. insidiosum growth at lower concentrations, implying that the nanoformulation preserves the stability of the compound and makes it inhibit the pathogen more efficiently. However, the results demonstrated herein differ from Fonseca et al. [21], who obtained the clinical cure of an animal with experimental pythiosis using a topically applied gel-based formulation containing a M. piperita and O. vulgare EO combination. Additionally, our findings differ from Valente et al. [26], who observed no differences in the size of pythiosis lesions in rabbits topically treated with a gel-based formulation containing biogenic silver nanoparticles or intralesionally treated with an aqueous solution of silver biogenic nanoparticles. The authors also reported the clinical cure of an animal treated with the topical gel-based formulation.

Despite the size of the lesions in the animals topically treated with the gel-based formulation not differing from the control group, the quantity and distribution of P. insidiosum hyphae within the lesions was lower (P < 0.05), indicating that this treatment somewhat affected the infection process. Furthermore, in the regression analysis, the lesions of the rabbits in group 2 showed a cubic behavior while in the control group was observed a linear behavior (Fig. 1). Based on previous studies evaluating topical formulations to treat experimental cutaneous pythiosis and reported cure of lesions [21, 26], the lower effectiveness of the topical NEMA formulation was an unexpected outcome of the present study. Nonetheless, this may likely have been because of a low NEMA concentration used for this topical application. On the other hand, we can also suggest that the treatment time needs to be longer. However, further studies are needed to confirm this hypothesis.

In the experimental conditions of this study, the intralesional administration of NEMA demonstrated efficacy in the treatment of cutaneous pythiosis in rabbits. Previously, M. alternifolia EO formulations were used in chinchillas by injectable administration in the tympanic membrane [37], and Souza et al. [7] demonstrated the anesthetic effects of nanoencapsulated M. alternifolia EO on crustaceans. These authors reported that injection was more efficient as an anesthetic than the immersion bath.

The lack of changes in the dermal toxicity tests in mice and the hematological and biochemical parameters of the animals treated with the NEMA-containing formulations suggest that these formulations are safe and not toxic to the animals. Similarly, Bezdjian et al. [37] and Souza et al. [7] did not observe any toxicity when using M. alternifolia EO intratympanic in chinchilla and as an anesthetic substance in crustaceans, respectively. In the present study, as also noticed by Loreto et al. [20] and Valente et al. [26], the hematological changes in the control group and treated animals were similar to the changes in animals with clinical pythiosis.

Conclusion

The NEMA-containing formulations described herein can be safely injected and applied topically. The results obtained allow us to infer that the aqueous formulation of NEMA administered intralesional was effective in the treatment of experimental pythiosis in rabbits. Nonetheless, further research evaluating the effectiveness of these NEMA formulations in naturally infected animals is necessary to validate the use of this therapy.

Supplementary Information

(DOCX 26 kb)

Author contribution

Silveira JS, Pereira DIB, and Botton SA conceived the idea, performed the experiment, collected and interpreted data, and wrote the manuscript. Silveira JS, Brasil CL, Braga CQ, Moreira AS, Albano AP, and Zambrano CG performed the animal experiment. Zamboni R and Sallis ES performed necropsy and histopathological analysis. Franz HC performed hematological and biochemical analysis. Silva CB and Araujo LC produced Melaleuca alternifolia nanoemulsion. Pötter L. performed the statistical analysis, interpreted data, and wrote the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior – CAPES - Finance Code 001) and National Council for Scientific and Technological Development – CNPq (Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico) for student and researcher scholarships.

Declarations

Ethics approval

All applicable institutional guidelines for the care and use of animals were followed (Ethics Committee of Federal University of Pelotas – CEEA - n° 23110.002723/2016-77).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Bakkali F. Biological effects of essential oils - a review. Food Chem Toxicol. 2008;46:446–475. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2007.09.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amann S, Neef K, Kohl S. Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) Eur J Hosp Pharm. 2019;26:175–177. doi: 10.1136/ejhpharm-2018-001820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kozics K, Bučková M, Puškárová A, et al. The effect of ten essential oils on several cutaneous Drug-resistant microorganisms and their cyto/genotoxic and antioxidant properties. Molecules. 2019;24:4570. doi: 10.3390/molecules24244570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carmo PHF, Costa MC, Franco PHC, et al. Essential oils of Taxandria fragrans and Melaleuca alternifolia have effective antidermatophytic activities in vitro and in vivo that are antagonised by ketoconazole and potentiated in gold nanospheres. Nat Prod Res. 2020;2:1–4. doi: 10.1080/14786419.2019.1709186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Casarin M, Pazinatto J, Oliveira LM, et al. Anti-biofilm and anti-inflammatory effect of a herbal nanoparticle mouthwash: a randomized crossover trial. Braz Oral Res. 2019;33:e062. doi: 10.1590/1807-3107bor-2019.vol33.0062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ireland DDJ, Greay SJ, Hooper CM, et al. Topically applied Melaleuca alternifolia (tea tree) oil causes direct anti-cancer cytotoxicity in subcutaneous tumour bearing mice. J Dermatol Sci. 2012;67:120–129. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2012.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Souza CF, Lima T, Baldissera MD, et al. Nanoencapsulated Melaleuca alternifolia essential oil exerts anesthetic effects in the brachyuran crab using Neohelice granulata. Academ Bras Ciências. 2018;90:2855–2864. doi: 10.1590/0001-3765201820170930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tullio V, Roana J, Scala SD, et al. Enhanced killing of Candida krusei by polymorphonuclear leucocytes in the presence of subinhibitory concentrations of Melaleuca alternifolia and "Mentha of Pancalieri" essential oils. Molecules. 2019;24:3824. doi: 10.3390/molecules24213824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Teng L, Fan X, Nelson DR, et al. Diversity and evolution of cytochromes P450 in stramenopiles. Planta. 2019;249:647–661. doi: 10.1007/s00425-018-3028-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gaastra W, Lipman LJ, De Cock AW, et al. Pythium insidiosum: an overview. Vet Microbiol. 2010;146:1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2010.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Souto EPF, Maia LA, Neto EGM, et al. Pythiosis in Equidae in Northeastern Brazil: 1985-2020. J Equine Vet Sci. 2021;105:103726. doi: 10.1016/j.jevs.2021.103726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hilton RE, Tepedino K, Glenn CJ, et al. Swamp cancer: a case of human pythiosis and review of the literature. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175:394–397. doi: 10.1111/bjd.14520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pereira DIB, Santurio JM, Alves SH, et al. Caspofungin in vitro and in vivo activity against Brazilian Pythium insidiosum strains isolated from animals. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2007;60:1168–1171. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zanette RA, Jesus FP, Pilotto MB, et al. Micafungin alone and in combination therapy with deferasirox against Pythium insidiosum. J Mycol Med. 2015;25:91–94. doi: 10.1016/j.mycmed.2014.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Itaqui SR, Verdi CM, Tondolo JS, et al. In vitro synergism between azithromycin or terbinafine and topical antimicrobial agents against Pythium insidiosum. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2016;60:5023–5025. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00154-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jesus FP, Loreto ES, Ferreiro L, et al. In vitro and in vivo antimicrobial activities of minocycline in combination with azithromycin, clarithromycin, or tigecycline against Pythium insidiosum. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2016;60:87–91. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01480-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bagga B, Sharma S, Guda SJM, et al. Leap forward in the treatment of Pythium insidiosum keratitis. British J Ophthalmol. 2018;102:1629–1633. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2017-311360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chatterjee S, Agrawal D. Azitromycin in the management of Pythium insidiosum keratitis. Cornea. 2018;37:e8–e9. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000001419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Loreto ES, Tondolo JSM, Oliveira DC, et al. In vitro activities of miltefosine and antibacterial agents from the macrolide, oxazolidinone and pleuromutilin classes against Pythium insidiosum and Pythium aphanidermatum. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2018;62:1678–1717. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01678-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Loreto ES, Tondolo JSM, Jesus FPK, et al. Efficacy of miltefosine therapy against subcutaneous experimental pythiosis in rabbits. J Mycol Med. 2019;30:1009–1019. doi: 10.1016/j.mycmed.2019.100919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fonseca AO, Pereira DI, Botton SA, et al. Treatment of experimental pythiosis with essential oils of Origanum vulgare and Mentha piperita singly, in association and in combination with immunotherapy. Vet Microbiol. 2015;178:265–269. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2015.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Araujo MJAM, Bosco SMG, Sforcin JM. Pythium insidiosum: inhibitory effects of propolis and geopropolis on hyfal growth. Braz J Microbiol. 2016;47:863–869. doi: 10.1016/j.bjm.2016.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Valente JSS, Fonseca AO, Brasil CL, et al. In vitro activity of Melaleuca alternifolia (tea tree) in its free oil and nanoemulsion formulations against Pythium insidiosum. Mycopathologia. 2016;181:865–869. doi: 10.1007/s11046-016-0051-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Valente JSS, Fonseca AO, Denardi LB, et al. In vitro susceptibility of Pythium insidiosum to Melaleuca alternifolia, Mentha piperita and Origanum vulgare essential oils combinations. Mycopathologia. 2016;181:5–6. doi: 10.1007/s11046-016-0019-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Trolezi R, Azanha JM, Paschoal NR, et al. Stryphnodendron adstringens and purified tannin on Pythium insidiosum:in vitro and in vivo studies. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2017;1:1–7. doi: 10.1186/s12941-017-0183-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Valente JSS, Brasil CL, Braga CQ, et al. Biogenic silver nanoparticles in the treatment of experimental Pythiosis. Med Mycol. 2020;58:913–918. doi: 10.1093/mmy/myz141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bouchemal K, Briançon S, Perrier E, et al. Nano-emulsion formulation using spontaneous emulsification: solvent, oil and surfactant optimization. Int J Pharm. 2004;280:241–251. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2004.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Flores FC, Ribeiro RF, Ourique AF, et al. Nanostructured systems containing an essential oil: protection against volatilization. Química Nova. 2011;34:968–972. doi: 10.1590/S0100-40422011000600010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.OECD (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development): Guideline for the testing of chemicals, 410: “repeated dose dermal toxicity: 21/28-day study”, Adopted 12 May 1981

- 30.Statistical Analysis System (SAS) (2019) SAS/STAT user guide, Version 9.4. Cary, NC: SAS Institute

- 31.Spinelli MO, Motta MC, Cruz RJ, et al. Estudo dos analitos bioquímicos no plasma de coelhos (Nova Zelândia) mantidos no biotério da Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo. Soc Bras Cienc Anim Lab (SBCAL) 2012;1:163–168. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ameri M, Schnaars HA, Sibley JR, et al. Determination of plasma fibrinogen concentrations in beagle dogs, Cynomolgus monkeys, New Zealand white rabbits, and Sprague-Dawley rats by using Clauss and prothrombin-time-derived assays. J Am Assoc Labo Anim Sci. 2011;50:864–867. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Emanuelli M, Lopes ST, Maciel R, et al. Concentração sérica de fosfatase alcalina, gama-glutamil transferase, uréia e creatinina em coelhos (Oryctolagus cuniculus) Ciênc Anim Bras. 2008;9:251–255. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pisseri F, Bertolib A, Nardonic S, et al. Antifungal activity of tea tree oil from Melaleuca alternifolia against Trichophyton equinum: An in vivo assay. Phytomedicine. 2009;16:1056–1058. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2009.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Swamy MK, Akhtar MS, Sinniah UR. Antimicrobial properties of plant essential oils against human pathogens and their mode of action: an updated review. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2016;1:1–21. doi: 10.1155/2016/3012462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kong Q, Zhang L, An P, et al. Antifungal mechanisms of a-terpineol and terpene-4-alcohol as the critical components of Melaleuca alternifolia oil in the inhibition of rot disease caused by Aspergillus ochraceus in postharvest grapes. J Appl Microbiol. 2019;126:1161–1174. doi: 10.1111/jam.14193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bezdjian A, Mujica-mota MA, Azzi M, et al. Assessment of ototoxicity of tea tree oil in a chinchilla animal model. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2014;78:2136–2139. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2014.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 26 kb)