Abstract

Honey is a natural product with beneficial properties to health and has different characteristics depending on the region of production and collection, flowering, and climate. The presence of precursor amino acids of- and biogenic amines can be important in metabolomic studies of differentiation and quality of honey. We analyzed 65 honeys from 11 distinct regions of the State of Santa Catarina (Brazil) as to the profile of amino acids and biogenic amines by HPLC. The highest L-tryptophan (Trp), 5-hydroxytryptophan (5-OH-Trp), and tryptamine (Tryp) levels were detected in Cfb climate and harvested in 2019. Although we have found high content of serotonin, dopamine, and L-dopa in Cfb climate, the highest values occurred in honey produced during the summer 2018 and at altitudes above 900 m. Results indicate that the amino acids and biogenic amine levels in honeys are good indicators of origin. These data warrant further investigation on the honey as source of amino acids precursor of serotonin, melatonin, and dopamine, what can guide the choice of food as source of neurotransmitters.

Keywords: L-tryptophan, serotonin, melatonin, L-dopa, dopamine

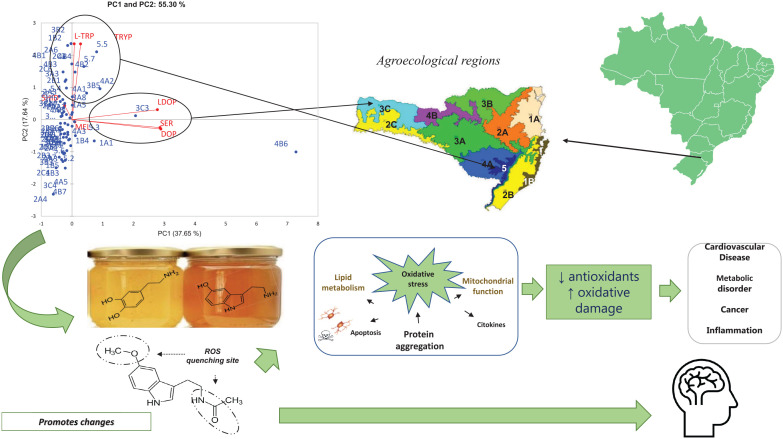

Graphical Abstract.

Introduction

Honey is known for its antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, anticancer, antiatherogenic, antithrombotic, and antioxidant effects, in addition to its analgesic activity in the human body. 1 Conscious consumption and the search for foods with good nutritional quality, aiming at the prevention of diseases, has been a priority in the human diet. In addition, there is also an interest in eating foods that provide well-being, both physical and emotional. 2 Phenolic compounds seem to be the most important constituents of honey, responsible for its antioxidant activity. 3 However, bioactive amines, as well as their precursor amino acids, have been the subject of many studies, due to the great interest regarding the nutritional paradox and their possible action as an antioxidant/well-being agent. These substances are also related to regulation of the cell cycle and play a fundamental role in the synthesis route of important neurotransmitters, 4 such as serotonin and dopamine.

Some studies report the presence of biogenic amines in samples of honey and other bee-derived products (ie, propolis), which have biological properties and can be used beneficially in the food and pharmaceutical industry. The presence of free amino acids in bee products can lead to the formation of biogenic amines (BA), which may be desirable or undesirable in food products, 5 making further research essential.

The ingestion of L-tryptophan (L-Trp) and 5-hydroxytryptophan (5-OH-Trp), for example, is essential for the formation of serotonin in the brain. Serotonin, a neurotransmitter, does not cross the blood–brain barrier 6 and the synthesis and turnover of this monoamine depend on the intake of amino acids. In humans, due to its essentiality, the recommended daily dose of L-Trp is around 4 mg/kg body weight per day for adults and 12 mg/kg body weight for children. 7 Thus, foods containing higher levels of L-Trp and 5-OH-Trp can help balance serotonin levels. It is noteworthy that honey is a source not only of L-Trp, but also of other metabolites derived from this amino acid and important to human health, such as nicotinamide (vitamin B6), melatonin, tryptamine, kynurenine, 3-hydroxykynurenine, and quinolinic and xanthurenic acids. 8 Furthermore, among other parameters, amino acid content has also been proposed as a method to determine the botanical and/or geographic provenance of food products, and honey has often been the target of this approach. 9

Honey and its derivatives have been increasingly valued natural substances; however, their physicochemical and biological properties are determined by many factors, including bee species, the nectar donor plant (specific for each season), geographic area/origin, seasonal conditions, harvesting and storage processes, and climatic conditions. 10 Therefore, it is important to expand the information on chemical composition and explore the biological activity of honeys from different geographic regions and methods of extraction, among other things. Due to its high complexity, the chemical analysis of honey poses a considerable challenge. Therefore, this study aimed to identify compounds from the biogenic amine class, as well as their precursor amino acids (ie, Trp and 5-OH-Trp) in honeys from different agro-ecological regions.

Methods

Honey collection places

Samples of honey (65) harvested in 2018 to 2019 were kindly provided by beekeepers from 11 agroecological regions of Santa Catarina State (Brazil), namely: (1) Planalto Serrano de São Joaquim, (2) coast, Itajaí, and Tijucas River Valleys, (3) coast of Florianópolis and Laguna, (4) Alto Vale do Itajaí, (5) Carboniferous, Extreme South, and Colonial Serrana, (6) Uruguai River Valley, (7) Alto Vale do Rio do Peixe and Alto Irani, (8) Central Plateau, (9) Northern Santa Catarina Plateau, (10) Santa Catarina Northwest, and (11) Campos de Lages (Table 1). All honey samples are polyfloral, because, in addition to presenting the predominant flowering described by beekeepers, they all contain pollen from native species of the regions of origin.

Table 1.

Location and predominant flowering of honey from Santa Catarina (flowering year/collection and season).

| Sample | Region | City | Altitude (m) | Climate (Koppen-Geiger) | Predominant flowering | Year of collection | Season |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1A1 | Coast, Itajaí, and Tijucas river valleys | Benedito Novo | 683 | Humid subtropical climate (Cfa) | Cinnamon and Piptocarpha angustifolia | 2019 | Summer |

| 1A2 | Itapoá | 457 | Wild flowers | 2018 | Spring | ||

| 1A3 | Itapoá | Wild flowers | 2019 | Summer | |||

| 1A4 | Nova Trento | 156 | Wild flowers | 2018 | Spring | ||

| 1A5 | Nova Trento | Eucalyptus | 2019 | Autumn | |||

| 1B1 | Jaguaruna | 92 | Eucalyptus | 2019 | Autumn | ||

| 1B2 | Coast of Florianópolis and Laguna | Balneário Gaivota | 9 | Humid subtropical climate (Cfa) | Wild flowers | 2019 | Spring |

| 1B3 | Jaguaruna | 92 | Wild flowers | 2018 | Autumn | ||

| 1B4 | Jaguaruna | Eucalyptus | 2019 | Spring | |||

| 1B5 | Major Gercino | 42 | Wild flowers | 2018 | Autumn | ||

| 1B6 | Major Gercino | Eucalyptus | 2019 | Autumn | |||

| 2A1 | Alto Vale do Itajaí | José Boiteux | 726 | Humid subtropical climate (Cfa) | Baccharis dracunculifolia | 2018 | Spring |

| 2A2 | José Boiteux | 491 | Dracena frangans and Holvenia dulcis | 2018 | Spring | ||

| 2A3 | José Boiteux | 717 | Eucalyptus | 2019 | Autumn | ||

| 2A4 | Salete | 593 | Holvenia dulcis | 2018 | Spring | ||

| 2A5 | Vidal Ramos | 763 | Baccharis dracunculifolia | 2019 | Summer | ||

| 2A6 | Vidal Ramos | 493 | Holvenia dulcis | 2019 | Summer | ||

| 2A7 | Vidal Ramos | 761 | Baccharis dracunculifolia | 2019 | Summer | ||

| 2B1 | Carboníferous, Extreme South, and Colonial Serrana | Anitápolis | 760 | Humid subtropical climate (Cfa) | Baccharis dracunculifolia, Piptocarpha angustifolia, trimera and Holvenia dulcis | 2018 | Spring |

| 2B2 | Anitápolis | Eugenia sp., Holvenia dulcis, Clethra scabra, and Dracena fragans | 2019 | Summer | |||

| 2B3 | Orleans | 600 | Wild flowers | 2018 | Spring | ||

| 2C1 | Uruguai River Valley | Descanso | 272 | Humid subtropical climate (Cfa) | Holvenia dulcis | 2018 | Spring |

| 2C2 | Descanso | Eucalyptus | 2019 | Autumn | |||

| 2C3 | Itapiranga | 300 | Eucalyptus | 2019 | Autumn | ||

| 2C4 | Itapiranga | Holvenia dulcis | 2019 | ||||

| 2C5 | Saudades | 364 | Holvenia dulcis | 2018 | Spring | ||

| 2C6 | Saudades | Eucalyptus | 2019 | Autumn | |||

| 3A1 | Alto Vale do Rio do Peixe and Central Plateau | Curitibanos | 995 | Humid temperate climate (Cfb) | Wild flowers | 2019 | Summer |

| 3A2 | Curitibanos | Wild flowers | 2019 | Summer | |||

| 3A3 | Erval Velho | 699 | Native fruit tree | 2018 | Spring | ||

| 3A4 | Erval Velho | Holvenia dulcis | 2018 | Spring | |||

| 3A5 | Erval Velho | Baccharis dracunculifolia and Holvenia dulcis | 2019 | Summer | |||

| 3A6 | Luzerna | 725 | Cinnamomum verum | 2018 | Spring | ||

| 3A7 | Luzerna | Holvenia dulcis | 2018 | Spring | |||

| 3A8 | Luzerna | Wild flowers | 2019 | Summer | |||

| 3B2 | Northern Santa Catarina Plateau | Bela Vista do Toldo | 793 | Humid temperate climate (Cfb) | Sebastiania commersoniana and Campomanesia xanthocarpa | 2018 | Spring |

| 3B3 | Três Barras | 766 | Sebastiania commersoniana | 2018 | Spring | ||

| 3B5 | Rio Negrinho | 982 | Wild flowers | 2018 | Spring | ||

| 3B6 | Rio Negrinho | 982 | Wild flowers | 2019 | Summer | ||

| 3B7 | Santa Terezinha | 625 | Holvenia dulcis | 2018 | Spring | ||

| 3C1 | Santa Catarina Northwest | Campo Erê | 894 | Humid temperate climate (Cfb) | Holvenia dulcis | 2019 | Summer |

| 3C2 | Campo Erê | 650 | Eucalyptus | 2019 | Autumn | ||

| 3C3 | Dionísio Cerqueira | 856 | Holvenia dulcis | 2018 | Spring | ||

| 3C4 | Dionísio Cerqueira | Eucalyptus | 2019 | Autumn | |||

| 3C5 | Xaxim | 598 | Holvenia dulcis | 2018 | Spring | ||

| 4A1 | Lages Field | Bocaina do Sul | 980 | Humid temperate climate (Cfb) | Campomanesia xanthocarpa, Piptocarpha angustifolia, Eugenia sp., and Vochysia tucanorum | 2018 | Spring |

| 4A2 | Bocaina do Sul | Clethra scabra | 2019 | Summer | |||

| 4A3 | Bom Retiro | 522 | Holvenia dulcis | 2019 | Summer | ||

| 4A4 | Bom Retiro | 944 | Clethra scabra | 2019 | Summer | ||

| 4A5 | Capão Alto | 1007 | Native plants | 2018 | Spring | ||

| 4A6 | Capão Alto | Wild flowers | 2019 | Summer | |||

| 4B1 | Alto Vale do Rio do Peixe and Alto Irani | Água Doce | 1203 | Humid temperate climate (Cfb) | Piptocarpha tomentosa | 2018 | Spring |

| 4B2 | Água Doce | 1203 | Ocotea porosa | 2018 | Spring | ||

| 4B3 | Água Doce | 1203 | Baccharis trimera | 2019 | Summer | ||

| 4B4 | Lebon Régis | 1280 | Cinnamon, Piptocarpha angustifolia, Clethra scabra, Baccharis uncinella, and Cupania vernalis | 2018 | Spring | ||

| 4B5 | Lebon Régis | 1280 | Vernonia polysphaera and Baccharis trimera | 2019 | Autumn | ||

| 4B6 | Matos Costa | 973 | Astronium fraxinifolium, Lithrea brasiliensis, and Ilex theezans | 2018 | Spring | ||

| 4B7 | Matos Costa | 1156 | Clethra scabra | 2019 | Autumn | ||

| 5(1) | Planalto Serrano de São Joaquim | Bom Jardim da Serra | 1272 | Humid temperate climate (Cfb) | Piptocarpha angustifolia, Lithraea molleoides, Astronium fraxinifolium, Baccharis trimera, and Brosimum gaudichaudii | 2018 | Spring |

| 5(2) | Bom Jardim da Serra | 1247 | Senna bicapsularis, Struthanthus flexicaulis, and Baccharis trimera | 2019 | Autumn | ||

| 5(3) | São Joaquim | 1276 | Piptocarpha angustifolia, Lithrea brasiliiensis, Astronium fraxinifolium, and Baccharis trimera | 2018 | Spring | ||

| 5(4) | São Joaquim | 1309 | Eupatorium sp., Struthanthus flexicaulis, Baccharis trimera, and Strychnos pseudoquina | 2019 | Autumn | ||

| 5(5) | São Joaquim | 1148 | Piptocarpha angustifolia and Mimosa scabrella | 2018 | Spring | ||

| 5(6) | São Joaquim | 1051 | Senna bicapsularis | 2019 | Summer | ||

| 5(7) | São Joaquim | 1055 | Wild flowers | 2019 | Summer |

Extraction and chromatographic analysis

Biogenic amines (serotonin—Ser, melatonin—Mel, dopamine—Dop, and tryptamine—Tryp), L-Trp, 5-OH-Trp, and L-dopa were extracted as described by Lima et al. 11 Honey samples (1 g) were mixed with 3 mL of perchloric acid (5%, v/v), homogenized (vortex, 1 minute) and incubated in a cold ultrasonic bath (30 minutes), followed by centrifugation (10 minutes, 6000g, 5°C). The supernatant containing the free amines and amino acids was collected and subjected to derivatization using supernatant, 4.5 mol/L Na2CO3 and 18.5 mmol/L dansyl-chloride in acetone. The solution was kept at 60°C for 1 hour and, in sequence, proline (1 mg/mL) was added and the mixture kept in the dark for 1 hour and homogenized by vortexing every 15 minutes. After this interval, toluene (HPLC grade) was added, the mixture was vortexed (1 minute) and the supernatant (hydrophobic part containing the target compounds) was dried in a nitrogen line.

The samples were resuspended in acetonitrile (HPLC grade), homogenized by vortexing and incubated (1 minute) in an ultrasonic bath, followed by filtration (0.25 μm) and injection in a high-performance liquid chromatograph (HPLC; Dionex UltiMate 3000; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Bremen, Germany), according to Dadáková et al 12 with modifications. Briefly, 20 μL of sample was injected into an ACE C18 reverse phase column (4.6 × 250 mm; 5 µm), thermostatted at 25°C, coupled to a quaternary automatic sampler 3000 pump and diode array detector (DAD-3000RS). Amines and amino acids were eluted in a gradient system, as follows: 0 to 2 minutes, 40% A + 60% B; 2 to 4 minutes, 60% A + 40% B; 4 to 8 minutes, 65% A + 35% B; 8 to 12 minutes, 85% A + 15% B; 12 to 15 minutes, 95% A + 5% B; 15 to 21 minutes, 85% A + 15% B; 21 to 22 minutes, 75% A + 25% B; 22 to 25 minutes, 40% A + 60% B. Identification of biogenic amine and amino acids of interest (eg, L-Trp, 5-OH-Trp, Tryp, L-dopa, Ser, Mel, and Dop) was based on the retention times of analytical standards (Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA), with detection at λ = 225 nm. For the purposes of compound quantification (µg/100 g), the peak areas were integrated using Chromeleon 7 software (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Bremen, Germany). The limit of detection (LOD), limit of quantification (LOQ), linear regression, regression coefficient (R2), recovery, and repeatability values (n = 6) observed are shown in Table 2. Repeatability (below 5%) was determined using 6 replicates/honey samples chosen at random. Mean recovery (%, n = 6) was tested with 5 concentrations (12.5, 50, 100, 150, and 200 mg/L) of analytical standard (Table 2).

Table 2.

LOD, LOQ, linear regression calibration curves, regression coefficient (R2), recovery, and repeatability of biogenic amines, by the analytical method in samples of honey.

| Aminoacids/biogenic amines | LOD a (mg/L) | LOQ (mg/L) | Regression equation | R2 | Recovery b values (%) | Repeatability c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tryptophan | 0.019 | 0.104 | y = 0.3614x + 0.1297 | .99 | 96.5 | 3.3 |

| 5-OH-tryptophan | 0.026 | 0.102 | y = 0.2574x + 0.0561 | .99 | 97.3 | 3.1 |

| Tryptamine | 0.049 | 0.106 | y = 4.232x + 42.342 | .99 | 94.8 | 4.1 |

| Serotonin | 0.013 | 0.085 | y = 4.0423x + 19.911 | .99 | 96.7 | 3.2 |

| Melatonin | 0.013 | 0.102 | y = 1.3749x + 0.9985 | .99 | 92.3 | 3.9 |

| L-dopa | 0.018 | 0.110 | y = 205.1x − 0.012 | .99 | 91.9 | 3.5 |

| Dopamine | 0.029 | 0.099 | y = 3.822x + 71.767 | .98 | 101.2 | 4.1 |

Range for amino acids and biogenic amines 12.5 to 200 mg/L.

n = 6.

n = 6.

Statistical analysis

Data on biogenic amines and their precursors found in honey samples were submitted to analysis of variance (ANOVA), and if the data were significant, they were submitted to the Scott Knott test (P < .05). The ANOVA and the mean comparison test were performed using SISVAR statistical software. 13 Principal component analysis (PCA; XLSTAT software, version 2020; Addinsoft, France) was applied to visualize the possible correlation between amino acid content and the different classes of biogenic amines and the agroecological regions where the samples were collected.

Results and discussion

Currently, honey and its products have been valued as natural foods. However, it and its physicochemical and biological properties are affected by several factors of (a)biotic nature. The results clearly reveal that the composition of floral honeys produced in southern Brazil is dependent on several factors, including the geographical area of production, that is, the agroecological region of production and collection, as well as the nectar donor plants (specific for each season), as also verified in other similar studies. 10

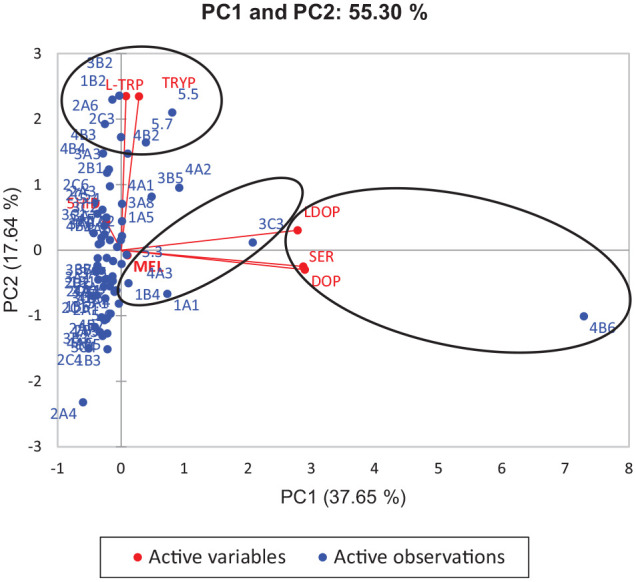

In an attempt to establish a descriptive model for the grouping of precursor amines and amino acids according to the different agroecological regions of collection, as well as flowers from which nectar is collected, it was decided to compare the results obtained by PCA. Honeys from the coast of Florianópolis and Laguna (1B2) (Cfa climate, humid subtropical climate – harvested in spring 2019), from the Northern Plateau of Santa Catarina (3B2, harvested in spring 2018), and from the agroecological region of the Planalto Serrano de São Joaquim (Cfb climate – temperate oceanic climate) (5.5 and 5.7, harvested in summer 2018 and 2019) stood out for their L-Trp content (PC1+ and PC2+). Honeys from Cfa climate (Alto Vale do Itajaí—2A6 and Uruguai River Valley—2C3) harvested in 2019 (summer and autumn, respectively) are distinguished from the others by having the highest tryptamine content (35.01 and 35.43 µg/100 g, respectively). Both L-Trp and Tryp are precursors of Ser and their presence may be important for the control of some physiological disorders, such as obsessive-compulsive disorder. 14 Ser and Dop (r = .89, P < .05), as well as the amino acid L-dopa with these amines, showed a significant and strong correlation (Ser: r = .76 and Dop: .79, P < .05). Honey from the agroecological regions Alto Vale do Rio do Peixe and Alto Irani (4B6), harvested in Spring 2018, showed the highest levels of these amines (Ser: 495.15 µg/100 g; Dop: 33.98 µg/100 g) and the amino acid L-dopa (0.72 µg/100 g) (PC1+ and PC2−) (Figures 1 and 2B; Table 3).

Figure 1.

Two-dimensional projection and scores of profile of precursor amino acids and biogenic amines of floral honeys from the agroecological regions of the State of Santa Catarina. Honey samples are represented by blue points (see Table 1) and amino acids and biogenic amines by red points.

Abbreviations: 5-OH-TRP, 5-hydroxy-tryptophan; L-DOPA, DOP, dopamine; L-TRP, L-tryptophan; MEL, melatonin; SER, serotonin; TRYP, tryptamine.

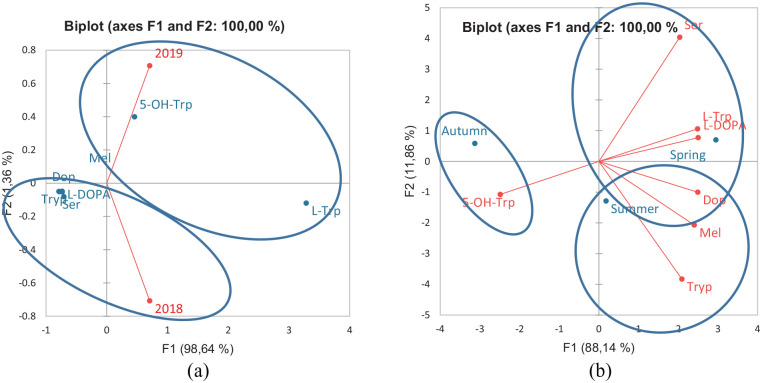

Figure 2.

Two-dimensional projection and scores of profile of precursor amino acids and biogenic amines of floral honeys from the agroecological regions of the State of Santa Catarina analyzed as to the time of harvest (A) and season (B). Honey samples are represented by blue points (see Table 1) and amino acids and biogenic amines by red points.

Abbreviations: 5-OH-TRP, 5-hydroxy-tryptophan; L-DOPA, DOP, dopamine; L-TRP, L-tryptophan; MEL, melatonin; SER, serotonin; TRYP, tryptamine.

Table 3.

Precursor amino acids and biogenic amines (µg/100 g) of floral honeys from the agroecological regions of the State of Santa Catarina (harvest 2018 and 2019).

| Honey | L-Trp 1 | 5-OH-Trp 2 | Tryp 3 | Ser 4 | Mel 5 | L-DOPA 6 | Dop 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1A1 | 749.08 ± 33.86p | 1314.04 ± 1.36d | 15.58 ± 2.47g | 21.27 ± 1.93l | 25.64 ± 3.23h | 0.07 ± 0.04h | 12.79 ± 0.60b |

| 1A2 | 930.66 ± 7.18o | nd | 22.47 ± 0.20d | 55.63 ± 0.79c | nd | 0.02 ± 0.00j | 1.68 ± 0.22j |

| 1A3 | 875.64 ± 0.45o | nd | 12.36 ± 0.14h | 20.68 ± 0.51l | nd | nd | 2.62 ± 0.17i |

| 1A4 | 970.84 ± 9.24o | nd | 17.21 ± 0.19f | 24.11 ± 0.52k | 11.99 ± 0.74k | 0.03 ± 0.00j | 2.32 ± 0.09i |

| 1A5 | 1612.14 ± 46.25j | 989.14 ± 67.77g | 15.26 ± 1.29g | 26.32 ± 1.75i | 24.54 ± 5.72i | 0.05 ± 0.00h | 3.93 ± 0.02g |

| 1B1 | 1408.79 ± 19.32k | 708.82 ± 3.43j | 12.60 ± 0.18h | 23.80 ± 0.14k | nd | 0.02 ± 0.00j | 1.48 ± 0.05j |

| 1B2 | 3358.65 ± 13.70a | 764.09 ± 0.06i | 18.24 ± 1.93f | 29.10 ± 0.25h | nd | 0.04 ± 0.00i | 1.66 ± 0.07j |

| 1B3 | 387.66 ± 23.42r | 1188.36 ± 53.31e | 10.63 ± 0.18i | 10.21 ± 0.16r | 36.16 ± 8.71g | 0.02 ± 0.00j | 4.08 ± 0.14g |

| 1B4 | 1113.56 ± 36.04n | 864.93 ± 78.17h | 13.83 ± 1.94h | 18.83 ± 0.73m | 93.26 ± 12.95a | 0.09 ± 0.04g | 3.86 ± 1.03g |

| 1B5 | 1150.29 ± 19.44n | 36.76 ± 0.86t | 8.25 ± 0.07j | 15.26 ± 0.23o | 20.85 ± 3.97i | 0.02 ± 0.01j | 2.99 ± 0.21h |

| 1B6 | 1224.87 ± 13.32m | 749.16 ± 14.09i | 10.88 ± 2.20i | 12.01 ± 0.02q | nd | 0.01 ± 0.00j | 1.96 ± 0.18j |

| 2A1 | 1226.04 ± 11.92m | 112.67 ± 0.06s | 11.44 ± 0.00i | 13.16 ± 0.21p | nd | 0.05 ± 0.00h | 1.55 ± 0.00j |

| 2A2 | 1316.26 ± 142.72l | 79.55 ± 30.53s | 18.00 ± 0.12f | 2.75 ± 0.10v | nd | 0.09 ± 0.00g | 1.12 ± 0.01k |

| 2A3 | 1081.90 ± 86.28n | 1210.13 ± 90.22e | 22.51 ± 0.39d | 17.73 ± 0.06n | 34.23 ± 1.30g | 0.03 ± 0.02i | 1.10 ± 0.13k |

| 2A4 | 263.31 ± 21.91s | 22.99 ± 0.44t | 6.24 ± 0.07k | 7.62 ± 0.21s | nd | nd | Nd |

| 2A5 | 1032.62 ± 14.80o | 90.07 ± 32.13s | 21.26 ± 0.22d | 6.76 ± 0.12t | nd | 0.02 ± 0.00j | 1.60 ± 0.17j |

| 2A6 | 1083.81 ± 35.33n | 494.50 ± 102.30m | 35.01 ± 0.92a | 4.74 ± 0.07u | 30.19 ± 4.83h | 0.03 ± 0.00j | 1.01 ± 0.08k |

| 2A7 | 944.98 ± 21.23o | 34.40 ± 0.82t | 11.90 ± 0.06i | 13.50 ± 0.05p | 19.17 ± 0.63i | 0.02 ± 0.00j | 1.73 ± 0.09j |

| 2B1 | 1504.82 ± 4.88k | 98.67 ± 13.70s | 23.57 ± 0.20c | 7.80 ± 0.40s | nd | 0.07 ± 0.00h | 1.03 ± 0.01k |

| 2B2 | 576.57 ± 6.24q | 48.96 ± 5.73t | 20.51 ± 0.10e | 2.22 ± 0.15v | nd | 0.03 ± 0.01j | 0.63 ± 0.07k |

| 2B3 | 627.68 ± 7.54q | 57.28 ± 11.45t | 14.58 ± 0.02g | 26.92 ± 0.75i | 21.19 ± 2.64i | 0.01 ± 0.00k | 1.90 ± 0.18j |

| 2C1 | 602.91 ± 6.76q | 337.50 ± 81.44o | 16.95 ± 0.94f | 12.58 ± 0.79p | 16.33 ± 1.14j | nd | 0.84 ± 0.06k |

| 2C2 | 1191.99 ± 28.47m | 141.90 ± 27.21r | 14.47 ± 2.67g | 8.02 ± 0.07s | 12.21 ± 2.42k | 0.01 ± 0.00j | 1.75 ± 0.06j |

| 2C3 | 836.37 ± 11.59p | 182.38 ± 80.60r | 35.43 ± 0.81a | 7.16 ± 0.57t | nd | 0.10 ± 0.03g | 1.32 ± 0.13j |

| 2C4 | 377.62 ± 5.99r | 111.11 ± 3.78s | 12.35 ± 0.15h | 5.43 ± 0.07u | 14.15 ± 1.56k | nd | 0.71 ± 0.22k |

| 2C5 | 743.89 ± 32.08p | 138.26 ± 3.26r | 26.97 ± 0.41b | 5.94 ± 1.48t | 17.43 ± 0.67j | nd | 1.13 ± 0.02k |

| 2C6 | 1764.97 ± 20.53i | 1156.40 ± 2.59f | 17.62 ± 1.83f | 8.24 ± 0.30s | 20.01 ± 0.72i | 0.01 ± 0.00j | 1.44 ± 0.30j |

| 3A1 | 1666.18 ± 15.98j | 343.50 ± 23.86o | 11.77 ± 0.15i | 15.27 ± 0.99o | 17.87 ± 1.27j | 0.02 ± 0.01j | 0.90 ± 0.02k |

| 3A2 | 967.73 ± 12.19o | 423.85 ± 14.23n | 15.39 ± 0.87g | 10.84 ± 0.36r | nd | 0.06 ± 0.00h | 1.23 ± 0.02j |

| 3A3 | 1515.81 ± 16.03k | 624.56 ± 21.23k | 24.17 ± 1.99c | 7.10 ± 0.61t | nd | 0.07 ± 0.00h | 0.86 ± 0.02k |

| 3A4 | 1096.43 ± 47.62n | 173.39 ± 5.96r | 13.59 ± 0.33h | 8.09 ± 0.05s | nd | 0.07 ± 0.00h | 3.20 ± 0.04h |

| 3A5 | 1207.37 ± 14.26m | 664.09 ± 4.33j | 15.31 ± 0.05g | 8.80 ± 0.04r | nd | 0.08 ± 0.00g | 2.34 ± 0.12i |

| 3A6 | 1381.80 ± 1.09k | 156.42 ± 9.71r | 17.69 ± 0.96f | 11.28 ± 0.03r | 27.75 ± 2.76h | 0.02 ± 0.00j | 1.24 ± 0.01j |

| 3A7 | 1440.32 ± 17.23k | 255.07 ± 16.63q | 18.28 ± 0.01f | 17.31 ± 0.20n | 37.79 ± 0.35f | 0.02 ± 0.00j | 1.48 ± 0.10j |

| 3A8 | 1466.00 ± 4.52k | 973.13 ± 34.25g | 18.31 ± 0.47f | 12.98 ± 0.47p | nd | 0.05 ± 0.02h | 4.86 ± 1.04f |

| 3B2 | 3158.17 ± 32.94b | 352.68 ± 9.56o | 21.29 ± 0.26d | 37.01 ± 0.09e | nd | 0.05 ± 0.00h | 1.54 ± 0.19j |

| 3B3 | 928.68 ± 1.88o | 173.53 ± 9.38r | 10.30 ± 0.01i | 13.74 ± 0.01p | 14.93 ± 2.44k | 0.02 ± 0.00j | 0.69 ± 0.04k |

| 3B5 | 1729.82 ± 16.02i | 777.89 ± 2.44i | 20.38 ± 0.02e | 13.97 ± 0.18p | nd | 0.06 ± 0.01h | 9.84 ± 0.06c |

| 3B6 | 1228.09 ± 12.22m | 221.52 ± 15.86q | 16.89 ± 0.15f | 8.82 ± 0.01r | nd | 0.02 ± 0.00j | 2.92 ± 0.03h |

| 3B7 | 1075.95 ± 14.30n | 287.19 ± 2.56p | 17.75 ± 0.16f | 9.61 ± 0.50r | nd | 0.02 ± 0.00j | 1.10 ± 0.04k |

| 3C1 | 934.12 ± 3.76o | 567.29 ± 13.81l | 21.67 ± 0.81d | 4.97 ± 0.00u | nd | 0.01 ± 0.00k | 0.93 ± 0.00k |

| 3C2 | 1309.26 ± 25.95l | 1547.30 ± 55.99c | 17.76 ± 0.99f | 21.38 ± 0.13l | nd | 0.02 ± 0.00j | 2.39 ± 0.07i |

| 3C3 | 1378.81 ± 13.15k | 87.45 ± 9.45s | 16.50 ± 2.51g | 51.52 ± 1.57d | 58.63 ± 0.31d | 0.53 ± 0.01b | 8.49 ± 1.48d |

| 3C4 | 637.20 ± 8.88q | 161.84 ± 3.21r | 11.99 ± 5.05i | 12.98 ± 0.35p | 17.60 ± 0.45j | 0.01 ± 0.00k | 2.51 ± 0.17i |

| 3C5 | 954.75 ± 2.01o | 108.54 ± 0.48s | 16.13 ± 1.05g | 14.92 ± 0.41o | 41.77 ± 0.88e | nd | 2.36 ± 0.62i |

| 4A1 | 2250.72 ± 2.55f | 119.28 ± 0.34s | 15.59 ± 0.63g | 31.31 ± 1.24g | nd | 0.04 ± 0.01i | 3.33 ± 0.37h |

| 4A2 | 944.05 ± 2.95o | 109.71 ± 1.51s | 27.22 ± 1.02b | 11.40 ± 0.52r | nd | 0.32 ± 0.00c | 4.68 ± 0.07f |

| 4A3 | 1451.82 ± 59.95k | 155.58 ± 33.77r | 14.61 ± 0.47g | 10.56 ± 2.09r | 44.49 ± 6.87e | 0.06 ± 0.00h | 3.96 ± 0.07g |

| 4A4 | 1452.47 ± 51.42k | 76.18 ± 7.58s | 12.37 ± 0.78h | 24.81 ± 0.74j | nd | 0.03 ± 0.00i | 1.54 ± 0.06j |

| 4A5 | 826.83 ± 0.73p | 71.95 ± 5.36s | 10.85 ± 0.54i | 24.71 ± 0.25j | nd | 0.01 ± 0.00k | 1.23 ± 0.01j |

| 4A6 | 1291.53 ± 36.42l | 287.23 ± 11.21p | 17.77 ± 0.40f | 37.70 ± 0.44e | nd | 0.03 ± 0.00j | 2.40 ± 0.12i |

| 4B1 | 1455.32 ± 30.95k | 98.47 ± 10.14s | 17.07 ± 0.33f | 33.04 ± 0.24f | 22.05 ± 1.30i | 0.00 ± 0.00k | 0.00 ± 0.00l |

| 4B2 | 2412.74 ± 59.28e | 153.78 ± 2.29r | 20.26 ± 0.41e | 26.98 ± 0.54i | nd | 0.09 ± 0.01g | 2.48 ± 1.61i |

| 4B3 | 2141.29 ± 10.93g | 2045.59 ± 72.26a | 18.65 ± 0.50f | 12.05 ± 0.05q | 45.15 ± 0.23e | 0.09 ± 0.00g | Nd |

| 4B4 | 1951.09 ± 17.79h | 115.81 ± 7.38s | 22.13 ± 1.20d | 20.83 ± 1.09l | nd | 0.05 ± 0.01h | 0.68 ± 0.02k |

| 4B5 | 837.81 ± 9.78p | 76.73 ± 2.56s | 16.03 ± 0.34g | 11.82 ± 1.30r | nd | 0.09 ± 0.02g | 0.69 ± 0.36k |

| 4B6 | 884.27 ± 25.97o | 99.36 ± 29.06s | 17.41 ± 0.86f | 495.15 ± 0.14a | nd | 0.72 ± 0.00a | 33.98 ± 0.20a |

| 4B7 | 786.62 ± 8.64p | 71.21 ± 1.31s | 13.62 ± 0.25h | 33.38 ± 0.44f | nd | 0.03 ± 0.00j | 1.74 ± 0.07j |

| 5.1 | 626.98 ± 7.19q | 1714.61 ± 28.85b | 14.83 ± 1.48g | 33.11 ± 0.54f | 30.03 ± 1.32h | 0.05 ± 0.00h | 2.69 ± 0.03i |

| 5.2 | 662.25 ± 7.29q | 1700.99 ± 10.37b | 15.95 ± 0.02g | 23.05 ± 0.24k | 32.83 ± 0.22g | 0.05 ± 0.00h | 2.97 ± 0.10h |

| 5.3 | 1122.22 ± 46.81n | 80.16 ± 6.03s | 19.63 ± 2.77e | 34.02 ± 3.20f | 88.08 ± 2.31b | 0.02 ± 0.00j | 4.02 ± 0.99g |

| 5.4 | 2024.21 ± 31.36h | 70.86 ± 0.20s | 15.89 ± 0.20g | 16.87 ± 1.19n | 35.24 ± 3.00g | 0.02 ± 0.01j | 1.85 ± 0.01j |

| 5.5 | 2569.65 ± 92.00d | 87.26 ± 5.95s | 25.13 ± 0.13c | 64.13 ± 0.05b | 44.29 ± 2.48e | 0.16 ± 0.03e | 5.02 ± 0.02f |

| 5.6 | 750.03 ± 28.87p | 115.33 ± 15.91s | 16.01 ± 0.32g | 25.57 ± 1.65j | 66.25 ± 3.76c | 0.02 ± 0.00j | 3.67 ± 0.65g |

| 5.7 | 2827.54 ± 41.19c | 81.84 ± 15.31s | 18.65 ± 0.09f | 27.92 ± 0.08h | 35.53 ± 7.00g | 0.13 ± 0.03f | 4.19 ± 0.93g |

| Minimum | 263.31 | nd | 6.24 | 2.22 | nd | nd | Nd |

| Maximum | 3358.65 | 2045.59 | 35.43 | 495.15 | 93.26 | 0.72 | 33.98 |

L-Trp levels ranged from 263.31 µg/100 g (2A4, Spring 2018) to 3358.65 µg/100 g (1B2, Spring 2019) (Figure 2A; Table 3). This difference is attributed to the plant species visited by the bees during nectar collection, as well as the honeys’ geographic origin and the time/season of harvest. Other studies highlight L-Trp values greater than 14 mg/kg in rosemary honeys, 15 while levels reached 1.9 mg/100 g in sunflower honeys 16 and 1.10 mg/100 g in lavender honey. 17 Among the samples analyzed, the lowest L-Trp content was found in honey whose main flowering was Hovenia dulcis (Japanese grape) (2A4), from the Atlantic Forest region, with a Köppen climate classification of Cfa and harvested in Spring 2018 and grouped in PC1− and PC2− (Figure 1). It is worth mentioning that, at the same time of harvest, Mel was not detected. These results also demonstrate that the year of harvest and season affects the levels of biogenic amines (Figure 2A and B). On the other hand, the honey with the highest L-Trp content (3358.65 µg/100 g) was produced in the coastal region of Santa Catarina, whose predominant bloom was composed of wild flowers (polyfloral honey) and harvested in spring 2019 (Table 1; Figure 2A and B). Some articles describe that L-Trp content varies depending on the predominant flora. Hermosín et al 17 detected L-Trp values of between 0.19 and 1.10 mg/100 g and the variation was dependent on the predominant flowering, that is, the lowest content was found in orange blossom honeys and the highest in lavender honeys. The authors claim that amino acid composition does not exactly distinguish the botanical origin of honeys, or their authenticity. In our study, the L-Trp content of most samples is very close to that found in the literature and sample harvested in spring showed the highest level of this amino acid; however, it is worth noting that the botanical origin, as well as the climate, region, and season, can affect the level of metabolites, including amino acids. The levels of metabolites formed from tryptophan are not correlated with the results of L-Trp content.

L-Trp found in honeys may come from plants (pollen, nectar, and resins) or from the metabolism of bees during honey production. In pollen, the contents of this aromatic amino acid are quite variable and may be very low, that is, 0.028 g/kg to 0.197 g/g18,19 or much higher, such as described in Rhododendron ponticum pollen (8053.00 µg/g). 20

L-Trp in honey has been the subject of several studies related to human health. For example, L-Trp supplementation appears to improve the social behavior of people suffering from disorders due to malfunctioning of the serotonergic system.21,22 Intake of L-Trp has been linked to decreased levels of psychosis in both animal and human studies and sleep deprivation. 22 Other studies have demonstrated that ingestion of honey with milk before bedtime may decrease hypoglycemic effects in diabetic patients, 23 or improve the sleep quality of healthy people or those with coronary heart problems. 24 Thus, L-Trp supplementation appears to improve control over social behavior in individuals who suffer from disorders or behaviors associated with dysfunctions in serotonergic functioning.

L-Trp is transported into the brain via the leucine-preferring L1 system and may compete with other amino acids (eg, tyrosine, phenylalanine, leucine, isoleucine, and valine) called “large neutral amino acids” (LNAA). 2 The L-Trp : :p : LNAA ratio determines the flux of this amino acid and, consequently, the biosynthesiSer in the brain. 25 Foods with a high content of L-Trp, such as honey, often also contain other amino acids in varying concentrations. Thus, the net effect of the L-Trp content in honeys is relevant, but it should be considered carefully with regard to possible increases in Ser synthesis, given the competition for a transporter system in the blood–brain barrier between this amino acid and the other LNAA. 2 Furthermore, excess L-Trp may cause adverse reactions, such as gastric problems and dizziness, among others. 21

The remainder of the L-Trp that is not used for protein synthesis may be converted to biomolecules such as kynurenine (KYN) (responsible for approximately 90% of L-Trp catabolism 26 ) or those related to neuroimmunological signaling, such as Ser and Mel. About 1% of dietary L-Trp is used for Ser synthesis,26,27 by the conversion of L-Trp to 5-OH-Trp or Tryp, depending on the metabolic pathway. KYN, derived from L-Trp catabolism, originates niacin, precursor of the coenzyme nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+). 27 In this pathway, 60 mg of Trp produces 1 mg of nicotinic acid or niacin. 28 The usual intake of Trp is approximately 900 to 1000 mg per day, 26 and the recommended daily dose is around 4 mg/kg body weight per day for adults and 12 mg/kg body weight for children. 7 According to our results, the consumption of honey as a source of L-Trp may help in several metabolic processes, including psychiatric and neurological disorders and anticancer immunity. 27 In children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder, the intake of L-Trp may decrease symptoms of irritability and mild depression due to increased Ser levels. 29

Although there is no consensus on the necessary amount of 5-OH-Trp or Tryp (Ser precursors) to be ingested daily, considerable levels were detected in some honeys as 5-OH-Trp (4B3-2045.59 µg/100 g) and Tryp (2A6-35.01 µg/100 g and 2C3-35.43 µg/100 g) (Table 3). Foods with higher levels of 5-OH-Trp and Tryp may favor the formation of Ser and Mel, due to the ease in crossing the brain–blood barrier (BBB), 27 since both the synthesis and the turnover of Ser depend on the intake of L-Trp and 5-OH-Trp. 30 In this study, we highlighted the maximum content of 5-OH-Trp (2045.59 µg/100 g) in the sample from Baccharis dracunculifolia DC (4B3), originating from an altitude of approximately 900 m. The same compound was detected at a lower level (22.99 µg/100 g) in 2A4, from a lower altitude (Alto Vale do Itajaí), that is, 593 m, which also showed a lower content of L-Trp (263.31 µg/100 g) and Tryp (6.24 µg/100 g) and no melatonin, L-dopa and dopamine (Table 3). Tryp has been used as a fermentation marker, along with other amines such as tyramine, cadaverine, putrescine, and histamine. This aromatic and heterocyclic biogenic amine can induce vasoactive or psychoactive effects on the human body. 31 According to the authors, the consumption of 25 to 30 mg/kg of Tryp can cause migraines; however, to reach these values, it would be necessary to consume approximately 900 g of honey from the samples that contain the highest levels.

Ser cannot cross the BBB and its intake contributes to a decrease in reactive oxygen species, as described in red blood cells of a mouse model, 32 mainly in the process of lipid peroxidation. 14 In the present study, Ser, Dop, and the amino acid L-dopa were all detected at higher levels in honeys from the mild Cfb climate. In the present study, Ser was detected in greater amounts (495.15 µg/100 g) in 4B6, a honey from an altitude of 1280 m, produced in spring 2018 and Cfb climate (Table 3). In this region, “aroeira” (Schinus sp.), “aroeira branca” (Lithraea molleoides), and “caúna” (Ilex theezans Mart. ex Reissek) are predominant (Table 1). The non-detection of Mel stands out in this sample. The lack of conversion of Ser into Mel could eventually contribute to an increase of Ser in the investigated honey samples. However, this was not observed in samples that did not show detectable levels of Mel. A low Ser content was verified in honeys from 2A2 and 2B2, both from a Cfa climate and from the Atlantic Forest ecosystem, but from different flowerings, regions, and altitudes (Table 3).

Higher levels of Mel, unlike Ser and Dop, were detected in honeys from coastal regions (agroecological regions coast of Florianópolis and Laguna, 1B4-93.26 µg/100 g) with a Cfa climate, low altitude (92 m), predominantly flowering of Eucalyptus and harvest in Spring 2019. Mel, Ser, and Dop were grouped in PC1− (Figure 2A) according to the year of harvest and in PC1+ in relation to the season (Figure 2B). In these figures and in Table 3 it is possible to verify that the levels of Mel varied between seasons, year, flowering, and climate and it is not possible to use this compound as a biochemical marker of honey quality. Mel, unlike Ser, crosses the BBB, in addition to having high antioxidant potential and not being able to be stored in the pineal gland, being released into the bloodstream and rapidly degraded in the liver. 33 Mel is an essential molecule related to the circadian rhythm; it has immunomodulatory and neuroprotective actions in tumor suppression, in addition to being related to oxidative stress. 34 Several studies were carried out during the Covid-19 pandemic using Mel and it has been recommended that the use of this substance may be related to a decrease in side effects due to its anti-inflammatory and antioxidant action.35,36 Thus, honeys with higher levels of Mel could be an interesting source of this amine, given its already demonstrated pharmacological effects.

In the studied honeys, the presence of L-dopa and Dop was also evidenced, the levels reaching 0.72 and 33.98 µg/100 g (4B6), respectively (Table 3), in honey from Vale do Rio do Peixe and Alto Irani with an altitude 973 m, Cfb climate and flowering of “aroeira” (Schinus sp.), “aroeira branca” (L. molleoides), and caúna (I. theezans Mart. ex Reissek) (Table 1). It is important to mention that the highest Ser content was also detected in these samples.

L-dopa levels in honeys are poorly described in the literature, which makes the data found in this work interesting. L-dopa occurs in plants as it is a precursor of several alkaloids, catecholamines, and melanin. 37 In honeys from Turkey, whose predominant flowering was fava beans (Vicia fava), Topal et al 39 reported an L-dopa content of 0.0321 mg/10 g, much higher than those found in honeys from Santa Catarina, Brazil. The L-dopa content may be due to the botanical source, as its presence at considerable levels in several plant species has already been described, including in fava bean genotypes, in flowers, leaves, and fruits. In humans, L-dopa has been used in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease, characterized by a deficiency in the synthesis of this catecholamine and as Dop cannot cross the BBB, while L-dopa does and is decarboxylated to form Dop in nerve cells. 39 In addition to acting as a neutrotransmitter, Dop may act as an immunomodulatory regulator, besides being indispensable for neuroimmune communication, i.e., its relationship with alterations in the functions of macrophages, lymphocytes, neutrophils and monocytes, showing that immune cells, in homeostatic and pathological conditions, interact with Dop centrally and peripherally. 40 Some studies have shown a relationship between Dop levels and Dop receptors and diseases such as glaucoma, diabetes and cardiovascular disease. 41 The analyzed honeys have been demonstrated to be a source of both substances and may be beneficial as adjuvants in therapies aimed at increasing the content of L-dopa and Dop.

Conclusion

The amino acid and biogenic amine content of floral honeys vary depending on several factors, including the agroecological region of production and collection, as well as the nectar donor plants and season. Ser and Dop, as well as the amino acid L-dopa, showed a significant and strong correlation and were detected in higher levels in honey from agroecological regions with a milder climate (Cfb), at higher altitudes and in Spring 2018. A higher content of 5-OH-Trp was also found in samples from a milder climate, harvest in 2019. On the other hand, L-Trp and Tryp, as well as Mel, were found at higher levels in honeys harvested in 2019 during the hottest seasons and in Cfa climate.

Footnotes

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP) (grants 2016/22665-2 and 2019/27227-1); the Foundation for Research Support of Santa Catarina (2020TR1452); and the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) (grants 307571/2019-0, 304657/2019-0, and 304657/2019-0).

Declaration Of Conflicting Interests: The author declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author Contributions: CVB: Formal analyses, statistical analysis, writing (draft preparation and review and editing). AN: Methodology and data curation, writing (data preparation). VEC: Methodology. ROO: Methodology and data curation. LSPB: Methodology, data curation and statistical analysis. GCM: Methodology and data curation. MM: Conceptualization, formal analysis, supervision, and project administration, writing (original draft preparation and review and editing), and funding acquisition. GPPL: Conceptualization, formal analysis, supervision and project administration, writing (original draft preparation and review and editing), and funding acquisition.

ORCID iDs: Vladimir Eliodoro Costa  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3889-7514

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3889-7514

Gean Charles Monteiro  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6072-8018

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6072-8018

Giuseppina Pace Pereira Lima  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1792-2605

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1792-2605

References

- 1. Siddiqui AJ, Musharraf SG, Choudhary MI, Rahman AU. Application of analytical methods in authentication and adulteration of honey. Food Chem. 2017;217:687-698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Strasser B, Gostner JM, Fuchs D. Mood, food, and cognition: role of tryptophan and serotonin. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2016;19:55-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sancho MT, Pascual-Maté A, Rodríguez-Morales EG, et al. Critical assessment of antioxidant-related parameters of honey. Int J Food Sci Technol. 2016;51:30-36. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gomez-Gomez HA, Minatel IO, Borges CV, et al. Phenolic compounds and polyamines in grape-derived beverages. J Agric Sci. 2018;10:65. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ruiz-Capillas C, Herrero AM. Impact of biogenic amines on food quality and safety. Foods. 2019;8:1-16. doi: 10.3390/foods8020062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Goihl J. Tryptophan can lower aggressive behavior. Feedstuffs. 2006;78:12-22. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Palego L, Betti L, Rossi A, Giannaccini G. Tryptophan biochemistry: structural, nutritional, metabolic, and medical aspects in humans. J Amino Acids. 2016;2016:8952520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Friedman M. Analysis, nutrition, and health benefits of tryptophan. Int J Tryptophan Res. 2018;11:1178646918802282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kelly MT, Blaise A, Larroque M. Rapid automated high performance liquid chromatography method for simultaneous determination of amino acids and biogenic amines in wine, fruit and honey. J Chromatogr A. 2010;1217:7385-7392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Machado De-Melo AA, Almeida-Muradian LBD, Sancho MT, Pascual-Maté A. Composition and properties of Apis mellifera honey: a review. J Apic Res. 2018;57:5-37. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lima GPP, da Rocha SA, Takaki M, Ramos PRR, Ono EO. Comparison of polyamine, phenol and flavonoid contents in plants grown under conventional and organic methods. Int J Food Sci Technol. 2008;43:1838-1843. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dadáková E, Křížek M, Pelikánová T. Determination of biogenic amines in foods using ultra-performance liquid chromatography (UPLC). Food Chem. 2009;116:365-370. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ferreira DF. Sisvar: a computer statistical analysis system. Ciênc. Agrotec. 2011;35:1039-1042. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Azouzi S, Santuz H, Morandat S, et al. Antioxidant and membrane binding properties of serotonin protect lipids from oxidation. Biophys J. 2017;112:1863-1873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Soto ME, Ares AM, Bernal J, Nozal MJ, Bernal JL. Simultaneous determination of tryptophan, kynurenine, kynurenic and xanthurenic acids in honey by liquid chromatography with diode array, fluorescence and tandem mass spectrometry detection. J Chromatogr A. 2011;1218:7592-7600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Qamer Samina Mohammed E, Shahid N, Abdul Rauf S. Free amino acids content of Pakistani unifloral honey produced by Apis mellifera. Pak J Zool. 2007;39:99-102. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hermosín I, Chicón RM, Dolores Cabezudo M. Free amino acid composition and botanical origin of honey. Food Chem. 2003;83:263-268. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lilek N, Adriana Pereyra G, Janko B, Andreja Kandolf B, Jasna B. Chemical composition and content of free tryptophan in Slovenian bee pollen. J Food Nutr Res. 2015;54:323-333. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Vrabie V, Liudmila Y, Valentina CĂ, Stela R. Comparative content of free aminoacids in pollen and honey. Rev Etnografie Ştiinţele Naturii Şi Muzeologie. 2019;30:71-78. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ecem Bayram N. Vitamin, mineral, polyphenol, amino acid profile of bee pollen from Rhododendron ponticum (source of ‘mad honey’): nutritional and palynological approach. J Food Meas Charact. 2021;15:2659-2666. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Steenbergen L, Jongkees BJ, Sellaro R, Colzato LS. Tryptophan supplementation modulates social behavior: a review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2016;64:346-358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Aucoin M, LaChance L, Cooley K, Kidd S. Diet and psychosis: a scoping review. Neuropsychobiology. 2020;79:20-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Brod M, Pohlman B, Wolden M, Christensen T. Non-Severe nocturnal hypoglycemic events: experience and impacts on patient functioning and well-being. Qual Life Res. 2013;22:997-1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Fakhr-Movahedi A, Mirmohammadkhani M, Ramezani H. Effect of milk-honey mixture on the sleep quality of coronary patients: a clinical trial study. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 2018;28:132-135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Stone TW, Darlington LG. The kynurenine pathway as a therapeutic target in cognitive and neurodegenerative disorders. Br J Pharmacol. 2013;169:1211-1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Richard DM, Dawes MA, Mathias CW, Acheson A, Hill-Kapturczak N, Dougherty DM. L-tryptophan: basic metabolic functions, behavioral research and therapeutic indications. Int J Tryptophan Res. 2009;2:45-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Comai S, Bertazzo A, Brughera M, Crotti S. Tryptophan in health and disease. Adv Clin Chem. 2020;95:165-218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Goldsmith GA. Niacin-tryptophan relationships in man and niacin requirement. Am J Clin Nutr. 1958;6:479-486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kałużna-Czaplińska J, Gątarek P, Chirumbolo S, Chartrand MS, Bjørklund G. How important is tryptophan in human health? Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2019;59:72-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Höglund E, Øverli Ø, Winberg S. Tryptophan metabolic pathways and brain serotonergic activity: a comparative review. Front Endocrinol. 2019;10:158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sanlier N, Bektesoglu M. Migraine and Biogenic Amines, 1362– 71. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Amireault P, Bayard E, Launay JM, et al. Serotonin is a key factor for mouse red blood cell survival. PLoS One. 2013;8:e83010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pandi-Perumal SR, Zisapel N, Srinivasan V, Cardinali DP. Melatonin and sleep in aging population. Exp Gerontol. 2005;40:911-925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Vielma JR, Bonilla E, Chacín-Bonilla L, Mora M, Medina-Leendertz S, Bravo Y. Effects of melatonin on oxidative stress, and resistance to bacterial, parasitic, and viral infections: a review. Acta Trop. 2014;137:31-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Essa MM, Hamdan H, Chidambaram SB, et al. Possible role of tryptophan and melatonin in COVID-19. Int J Tryptophan Res. 2020;13:1178646920951832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kleszczyński K, Slominski AT, Steinbrink K, Reiter RJ. Clinical trials for use of melatonin to fight against COVID-19 are urgently needed. Nutrients. 2020;12:2561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Soares AR, Marchiosi R, Siqueira-Soares Rde C, Barbosa de Lima R, Dantas dos Santos W, Ferrarese-Filho O. The role of L-DOPA in plants. Plant Signal Behav. 2014;9:e28275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Topal N, Bulduk I, Mut Z, Bozodlu H, Tosun YK. Flowers, pollen and honey for use in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease. Revista de Chimie. 2020;71:308-319. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Chagraoui A, Boulain M, Juvin L, Anouar Y, Barrière G, Deurwaerdère P. L-DOPA in Parkinson’s disease: looking at the ‘false’ neurotransmitters and their meaning. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;21:294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Matt SM, Gaskill PJ. Where is dopamine and how do immune cells see it?: dopamine-mediated immune cell function in health and disease. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2020;15:114-164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Buccolo C, Leggio GM, Drago F, Salomone S. Dopamine outside the brain: the eye, cardiovascular system and endocrine pancreas. Pharmacol Ther. 2019;203:107392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]