Abstract

Bioluminescent reporter organisms have been successfully exploited as analytical tools for in situ determination of bioavailable levels of contaminants in static environmental samples. Continued characterization and development of such reporter systems is needed to extend the application of these bioreporters to in situ monitoring of degradation in dynamic environmental systems. In this study, the naphthalene-degrading, lux bioreporter bacterium Pseudomonas putida RB1353 was used to evaluate the relative influences of cell growth stage, cell density, substrate concentration, oxygen tension, and background carbon substrates on both the magnitude of the light response and the rate of salicylate disappearance. The effect of these variables on the lag time required to obtain maximum luminescence and degradation was also monitored. Strong correlations were observed between the first three factors and both the magnitude and induction time of luminescence and degradation rate. The maximum luminescence response to nonspecific background carbon substrates (soil extract broth or Luria broth) was 50% lower than that generated in response to 1 mg of sodium salicylate liter−1. Oxygen tension was evaluated over the range of 0.5 to 40 mg liter−1, with parallel inhibition to luminescence and degradation rate (20 mg of sodium salicylate liter−1) observed at 1.5 mg liter−1 and below and no effect observed above 5 mg liter−1. Oxygen tensions from 2 to 4 mg liter−1 influenced the magnitude of luminescence but not the salicylate degradation rate. The results suggest that factors causing parallel shifts in the magnitude of both luminescence and degradation rate were influencing regulation of the nah operon promoters. For factors that cause nonparallel shifts, other regulatory mechanisms are explored. This study demonstrates that lux reporter bacteria can be used to monitor both substrate concentration and metabolic response in dynamic systems. However, each lux reporter system and application will require characterization and calibration.

A major constraint to the development of successful bioremediation technology is the limited ability to quantify bioavailable levels of contaminants to determine whether the concentrations are within the range for potential microbial degradation. There are presently no extraction techniques that are well correlated with bioavailability because current techniques remove some fraction of the sorbed or nonaqueous-phase contaminant which may be physically and chemically unavailable to microbial populations (9, 19, 21, 34). Thus, there is considerable interest in the development of assays that will determine contaminant bioavailability. One such assay uses bioluminescent reporter organisms. In these reporter organisms, the bioluminescence operon (lux) is inserted into biodegradation or resistance pathways of interest so that the lux genes are expressed concurrently and thus can be used to monitor the real-time genetic expression of the pathway of interest. Continued development of this bioluminescent reporter system can meet the urgent need in bioremediation research for tools to not only quantify bioavailable pollutants but also to perform in situ monitoring of degradation in the environment.

Luminescence is produced by the reporter bacterium in a luciferase-catalyzed reaction in response to the oxidation of reduced flavin mononucleotide (FMNH2) and a long-chain aldehyde (15). A number of bioluminescent reporter bacteria have been engineered to quantify bioavailable concentrations of organic contaminants (1, 4, 12, 14, 26, 29, 30, 32) and heavy metals (22, 25). The majority of these organisms use either the luxAB genes encoding the bacterial luciferase or the complete lux operon (luxCDABE), which also encodes the fatty acid reductase complexes required to produce the aldehyde substrate (16, 24). Use of the complete lux operon allows the nondestructive tracking of a specific organism or monitoring of the presence or utilization of organic or heavy-metal compounds in environmental systems without the exogenous addition of the aldehyde substrate. The disadvantage in using the entire operon is that generation of the aldehyde is an ATP- and NADPH-dependent process that not only increases the metabolic load of the cell (5, 10) but also depends upon the channeling of fatty acids into the luminescence system. In addition, for all bioreporters, energy must be diverted to different components of the electron transport system for luminescence production (22). Therefore, the intensity of luminescence can reflect environmental and physiological changes that affect bioreporter metabolic activity.

A number of authors have observed the sensitivity of bioluminescence to various physiological and environmental factors (3, 4, 6, 8, 15, 17, 24). Previous work has also demonstrated the potential for utilization of lux genes for detection in static systems over a small range of concentrations where physiological and environmental conditions can be tightly controlled. For example, Heitzer et al. (7, 8) and Sticher et al. (30) observed a linear relationship between substrate concentration and luminescence, while Rattray et al. (24) and Meikle et al. (18) have looked at the effect of cell density on luminescence. However, no comprehensive studies have been conducted to evaluate the influence of a range of parameters on a single organism. Thus, there remains a need to evaluate physiological and environmental parameters on a broader scale in order to anticipate factors which might cause deviations from the predicted response for applications of the lux bioreporters in situ. In addition, for applications to dynamic systems, it is not enough to consider only the magnitude of luminescence at a specific sample time, as has been done in previous work. Rather, the maximum potential luminescence, the lag time to maximum luminescence, and the relationship of these values to expression of the genes of the regulatory pathway of interest must be understood.

The objective of this research was to conduct a comprehensive overview of the effect of a range of factors on several parameters with a single indicator organism to evaluate the potential use of lux bioreporters as analytical tools or metabolic indicators in a dynamic system such as a saturated flow column. The factors evaluated were cell growth stage, cell density, substrate concentration, oxygen tension, and the interference of potential background carbon substrates from a soil system. Parameters measured included the magnitude of luminescence, the lag time in attaining the maximum response, and the correlation of this response with comparable changes in substrate degradation rates and lag times.

The indicator bioreporter used was Pseudomonas putida RB1353, developed by Burlage et al. (4) and containing two plasmids, the NAH7 plasmid and the constructed nah-lux reporter plasmid, pUTK9. NAH7 is an 83-kb plasmid with genes for naphthalene catabolism in two operons referred to as the upper and lower pathways. The upper pathway degrades naphthalene to salicylate, while the lower pathway is responsible for salicylate metabolism (33). Plasmid pUTK9 is subcloned with a fusion between the promoter from the upper pathway of NAH7 and the luxCDABE genes of Vibrio fischeri (4). Strain RB1353 is an identical sister clone to RB1351 described by Burlage et al. (4a). Burlage et al. (4) demonstrated that light production from RB1351 was directly correlated with naphthalene catabolism and documented a 20-fold increase in light from colonies exposed to naphthalene vapors.

Salicylate was chosen as the substrate for this study because it is responsible for the induction of both nah operons and its high solubility allows investigations of the effects of a wide range of substrate concentrations. Possible inhibitory effects of the lux operon on expression of the nah genes were evaluated by comparison of RB1353 to the parent strain, Pseudomonas putida HK53 (4). Strain HK53 was formed by mating NAH7 into P. putida PB2440.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and media.

P. putida RB1353 with stable plasmids NAH7 and pUTK9 (kanamycin resistance) and Pseudomonas putida HK53 (rifampin resistance), were kindly supplied by Robert Burlage, Oak Ridge National Laboratories, Oak Ridge, Tenn., and Gary Sayler, Center for Environmental Biotechnology, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, Tenn., respectively. The strains were maintained in Luria broth (LB) containing 10 g of tryptone, 5 g of yeast extract, and 10 g of NaCl in 1 liter of deionized H2O with the pH adjusted to 7.0. The medium was supplemented with either 100 mg of kanamycin sulfate liter−1 to select for plasmid pUTK9 or 50 mg of rifampin liter−1 for strain PB2440 as needed. Agar plates were made by amending LB with 1.5% Bacto Agar (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.). Mineral salts broth (MSB), used for growth on sodium salicylate, contained (in grams per liter) KH2PO4, 1.5; Na2HPO4, 0.5; MgSO4 · 7H2O, 0.2; NH4Cl, 2.5; FeCl3, 3 × 10−4; and CaCl2 · 2H2O, 0.013. Sodium salicylate and antibiotics were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo. Bacterial strains were stored frozen in glycerol (12.5% glycerol), and fresh cultures were inoculated from these stocks for each experiment to avoid plasmid loss. Bacterial strains were grown at 24°C with constant shaking at 120 rpm. Cell density was determined spectrophotometrically at 550 nm with a U-2000 spectrophotometer (Hitachi Instruments, Inc., Fremont, Calif.) and confirmed by viable plate counts of serial dilutions.

Cell preparation and experimental design.

Bacteria cells used for luminescence and salicylate degradation assays were grown in LB amended with antibiotics appropriate for the individual strain as specified above. Cultures were inoculated at a density of 104 CFU ml−1 from a 30-h preculture in the same medium and allowed to grow until the desired growth stage according to a previously determined growth curve. Growth was characterized by an initial lag period, logarithmic growth, and a relatively long deceleration phase followed by stationary and death phases. Cells were grown in LB prior to transfer to salicylate because cells grown under these conditions produced a light signal at least twice the intensity of that produced by cells grown originally in salicylate. After removal from LB, the cells were washed twice in saline (0.85% NaCl), resuspended in MSB, and amended with sodium salicylate. Cultures for each treatment were prepared in triplicate in 250-ml Erlenmeyer flasks with 30 ml of culture per flask and placed on the shaker. Samples (1 ml) were removed from each flask at each sampling time and analyzed for luminescence or sodium salicylate.

Quantitation of luminescence and sodium salicylate. (i) Luminescence.

Samples (1 ml) were analyzed for luminescence in 7-ml plastic scintillation vials in a 1600TR Tri Carb liquid scintillation analyzer (Packard Instrument Co., Meriden, Conn.). Samples were placed into a vial and immediately counted for 1 min in the single-photon mode, generating relative values expressed in counts per minute. Repeated counting of a single vial or prolonged incubation (longer than 30 min) of samples in plastic vials was avoided because such treatment was found to cause elevated counts compared to those of samples read immediately after removal from culture flasks. Luminescence values obtained at each sampling time were plotted as a function of time, and the peak luminescence value and peak time were recorded for each experiment. Peak time was defined as the time required to attain the maximum luminescence. Alternatively, total luminescence was calculated by integrating under the curve to evaluate the relationship between total luminescence generated and the salicylate degradation rate.

(ii) Salicylate.

Salicylate samples (1 ml) were added to 0.5 ml of 1 M NaOH to inhibit further degradation. Before analysis, the samples were centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 10 min to remove cell debris. The sodium salicylate concentrations were then determined from a standard curve by using the U-2000 spectrophotometer at 296 nm and plotted as a function of the sampling time. Degradation curves were characterized by an initial lag followed by a period of increasing degradation rate until the maximum degradation rate (Vmax) was attained with approximately 80% of the initial substrate remaining. A decrease in the degradation rate typically began with 35% of the original substrate remaining. Thus, Vmax was defined as the regression of the linear portion of the degradation curve between 35 and 80% of the original sodium salicylate concentration. Maximum degradation was repeatedly found within this interval regardless of initial substrate concentration. Induction or lag time for salicylate degradation was defined as the time required to degrade the initial 20% of substrate before Vmax was attained.

Growth stage, cell density, and substrate experiments.

Three series of experiments were conducted with RB1353(pUTK9, NAH7) to evaluate the influence of growth stage, cell density, and substrate concentration on the following four parameters: magnitude of luminescence, peak luminescence time, maximum salicylate degradation rate (Vmax), and degradation induction time. Growth stage experiments were conducted with cells from the log, deceleration, stationary, and death phases obtained from a continuously growing LB culture as described previously. Cells removed at each growth stage were washed twice in saline, diluted to a standard concentration of 107 CFU ml−1 in MSB, amended with 20 mg of sodium salicylate liter−1, and sampled to determine the luminescence and degradation rate. The influence of cell density was evaluated by using 106, 107, and 108 CFU of RB1353 ml−1 obtained from a stationary-phase LB culture. Cells were exposed to 20 mg of sodium salicylate liter−1, and luminescence and salicylate degradation data were determined. Finally, substrate concentration experiments were conducted in the same way with 107 CFU of stationary-phase RB1353 cells ml−1. Sodium salicylate was supplied at a range of concentrations from 0 to 40 mg liter−1, and data were collected as described previously.

Interference from background carbon substrates.

Luminescence produced in response to nonspecific carbon substrates was measured to evaluate potential false signals produced in a dynamic soil system. Stationary-phase cells were used for all experiments to maximize potential interference, since cells of this growth phase were found to produce the strongest luminescence response (see Results). Triplicate flasks containing 4.5 × 107 CFU of stationary-phase RB1353 cells ml−1 were exposed to either 20 mg of sodium salicylate liter−1, 50% LB, or soil extract broth. Soil extract broth was prepared as described in the Handbook of Microbiological Media (2) with a sandy loam from an oak and pine forest in Rose Canyon (Santa Catalina Mountains, Tucson, Az.) and was diluted 1:1 with MSB. Soil extract was used to evaluate potential interference produced in response to the presence of soil organic material as a substrate, and LB was chosen as the rich substrate preferred for growth of this organism. Luminescence was monitored for 5 h.

Influence of lux genes on degradation rates.

Comparisons were done between P. putida RB1353(NAH7, pUTK9) and the parent strain, P. putida PB2440(NAH7), to evaluate the influence of the lux gene plasmid pUTK9 on salicylate degradation behavior. Simultaneous salicylate degradation assays were conducted as described above with the same cell density and growth stage for both strains. In addition, degradation rates for PB2440 were determined for both deceleration- and stationary-phase cells to evaluate whether changes in cell growth phase had similar effects on Vmax for both RB1353 and PB2440.

DO concentration experiments.

Two series of experiments were designed to determine the effects of dissolved-oxygen (DO) tension on the salicylate degradation rate and the corresponding luminescence response. Stationary-phase cells were used for all experiments, prepared as described previously, and added to the MSB salicylate (20 mg liter−1) broth to give an approximate cell density of 107 CFU ml−1 for each assay unless stated otherwise. DO concentrations were determined by using a micro-oxygen electrode and oxygen meter (Microelectrodes, Inc. Bedford, N.H.). Calibration was done with buffer sparged with N2 gas and ambient air for 0- and 8.5-ppm values, respectively.

The first experiment was designed to evaluate the effects of an environment where initial ambient oxygen levels could not be maintained due to limitations on diffusion potential. Triplicate 250-ml Erlenmeyer flasks were filled with either 12% volume (30 ml) or 90% volume (225 ml) of medium and placed on a shaker at 120 rpm under ambient air conditions. All flasks had an initial DO concentration of 8.5 mg liter−1, but the large volume and limited surface area in the flasks containing 225 ml of medium impeded diffusion of air throughout the medium. Oxygen tension, salicylate concentration, and luminescence were monitored in samples taken from the flasks throughout the assay.

The second series of experiments was designed to evaluate the effect of variations in initial oxygen tension on salicylate degradation and luminescence. Sterile assay medium was added to 20-ml gas chromatography vials, which were then sealed with septa. The vials were then sparged with either sterile O2 or N2 at a constant flow rate for a specific time interval and allowed to equilibrate for 24 h with constant shaking. Variations in sparging time created treatments with oxygen concentrations ranging from 0.5 to 40 mg liter−1. Twelve vials sparged for identical lengths of time were prepared for each treatment, allowing a single vial to be sacrificed at each sample time for oxygen, salicylate, and luminescence measurements. Each vial was inoculated by syringe with 100 μl of saline cell suspension at the start of the assay, giving an average cell density of 3.3 × 107 ± 5.4 × 106 CFU ml−1. Three different DO concentrations were compared for each experiment in addition to an unsparged control, and the experiment was repeated five times. Since luminescence and salicylate degradation data change with slight fluctuations in cell inoculum growth or preparation time, all results were normalized with respect to the unsparged control assay run during each experiment to allow comparison of data from all five experiments.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Growth phase.

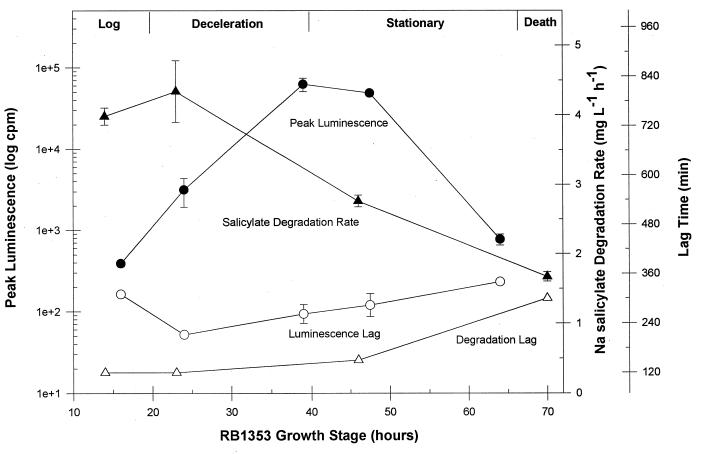

The growth phase was found to have a significant impact on both the magnitude of the luminescence response and the salicylate degradation rate for strain RB1353 (Fig. 1). Luminescence produced by stationary-phase cells was 1 order of magnitude greater than that produced by deceleration phase cells and 2 orders of magnitude greater than that produced from either log-phase or late-stationary-phase cells. The implications of these results are twofold. First, maximum sensitivity for detection of low substrate concentrations or low cell numbers will be attained in a static system with early-stationary-phase RB1353 cells. As a corollary to this, these results suggest that the effect of growth phase on the lux response should be evaluated for all new lux strains to achieve maximum sensitivity. Second, quantitation of carbon substrate, based on the light response, must take into consideration the growth potential of the cells in a dynamic system. As such, alternate standard curves must be developed for actively growing as opposed to stationary-phase cells. The maximum salicylate degradation rate was also found to vary with growth phase, with maximum rates being detected from logarithmic- and deceleration-phase cells (Fig. 1). The rates decreased with stationary-phase cells and continued to decline as cells entered the death phase. The shortest lag times for both Vmax and peak luminescence corresponded to the growth phase associated with maximum Vmax values (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Effect of cell growth stage on peak luminescence, Vmax, and the associated lag times of RB1353.

The growth phase results (Fig. 1) clearly demonstrate a difference between optimal growth phases for maximum luminescence and Vmax. Thus, lux gene expression is not regulated by induction alone, as would be assumed, since both the lux and nah operons are regulated by the nah promoter in response to salicylate. Rather, the parallel effect of growth phase on the minimum lag time for both luminescence and Vmax suggests that both pathways are induced simultaneously but that the optimal growth phase for luminescence seems to be partially controlled by metabolic factors affecting the availability of some essential component of the lux reaction.

Similar effects have been observed previously for Vibrio strains, where the luciferase catalytic cycle was found to be more rapid in late-log-phase than early-log-phase cells (6). In addition, Rattray et al. (24) found that light output varied with growth stage for E. coli strains containing plasmids with the full lux cassette (luxCDABE), with maximum luminescence occurring in the early stationary phase. In contrast, organisms bearing only the luxABE genes produced light evenly throughout the growth cycle. The latter organisms require an exogenous supply of dodecyl aldehyde, thus guaranteeing a constant aldehyde concentration in a reaction where the intensity of luminescence is partially dependent on the aldehyde concentration (3, 30). Light emission is affected by the flux of fatty acid and aldehyde through the fatty acid reductase system, and the fatty acids must be diverted away from normal lipid production for the lux reaction (15). Thus, it is possible to hypothesize that metabolic changes affecting the availability of the aldehyde substrate may be associated with the growth phase and cause the observed fluctuations in luminescence with growth phase.

Cell density.

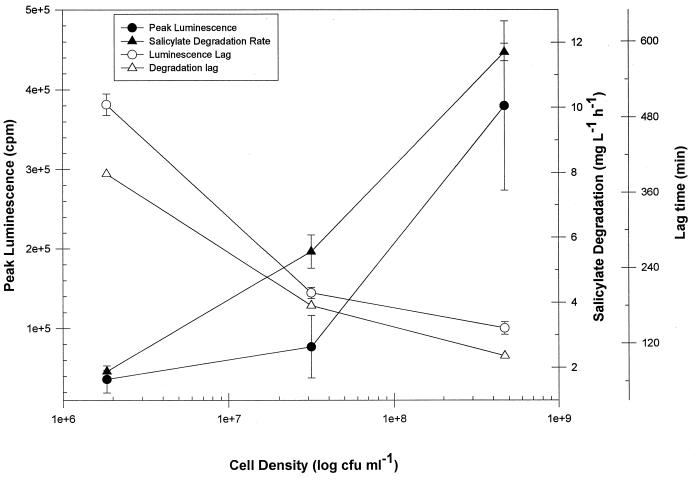

A positive correlation was observed with increasing cell density for both peak luminescence and Vmax (Fig. 2). A particularly good linear correlation was found between peak luminescence and cell number (r2 = 0.9973). Lag times were also affected by changes in biomass. An inverse relationship was observed between cell density and lag times associated with both peak luminescence and Vmax (Fig. 2). Significant shifts in lag time, from 60 to >200 min, were observed in response to 1-log-unit changes in cell counts. Thus, in dynamic systems, changes in cell number will have significant effects on both the magnitude and timing of luminescence and Vmax.

FIG. 2.

Effect of cell density on peak luminescence, Vmax, and the associated lag times of RB1353.

Substrate concentration.

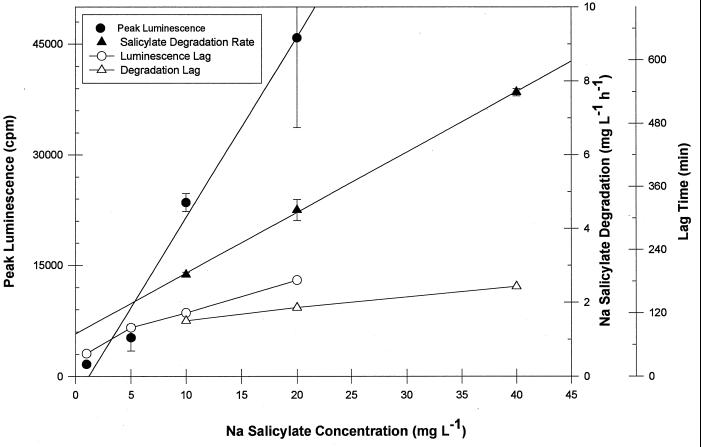

A strong positive linear correlation was found between substrate concentration and both luminescence (r2 = 0.98) and Vmax (r2 = 0.98) (Fig. 3). Lag times increased for both peak luminescence and Vmax in response to increasing substrate concentration (Fig. 3). Thus, both the magnitude and lag time of peak luminescence and Vmax are affected by substrate concentration.

FIG. 3.

Effect of sodium salicylate concentration on peak luminescence, Vmax, and the associated lag times of RB1353.

In previous work, luminescence has been used to measure substrate concentrations in unknown samples. Generally, luminescence is measured at a standardized sample time interval after exposure of the cells to the contaminant. This does not take into account possible shifts in lag time caused by changes in the contaminant concentration, as we have observed for RB1353. Thus, our results show that this can lead to erroneous results. For example, peak luminescence occurs 43 min following exposure to 1 mg of sodium salicylate liter−1 but 182 min following exposure to 20 mg liter−1. Further, the signal generated in response to 20 mg liter−1 at 43 min was lower than that for 1 mg liter−1, while the signal generated in response to 1 mg of sodium salicylate liter−1 was negligible at 182 min. Although shifts in lag time would be minimized if the substrate concentration were held within a very limited range, care must be taken to consider the influence of lag time on luminescence when analyzing for unknown concentrations.

The strong linear correlation between luminescence and both cell density and substrate concentration explains the current enthusiastic exploitation of lux genes as bioreporters, but the associated changes in lag times highlight the fact that these reporters are living cells, and the use of the assay must not be oversimplified. The implications of shifting lag times caused by such factors as growth stage, substrate concentration, and cell density may complicate the use of the luminescence assay as an analytical tool, but they enhance its potential use as a metabolic indicator of degradation behavior and, more specifically, of Vmax. Increases in mineralization lag time associated with increasing substrate concentration have been previously documented (27). This reinforces the hypothesis that the substrate-associated shifts in luminescence lag time are correlated with, and thus indicators of, the lag in induction of the nah and sal operons. This assumption is further corroborated by a similar pattern of increasing lag time associated with increasing salicylate concentration observed by using mRNA detection as an index of gene expression (13). Such parallel behavior demonstrates the unique value of the lux genes as nonextractive, real-time bioindicators of gene expression, in contrast to lacZY-type systems (23), which require an extraction and enzyme assay for analysis.

Influence of background carbon substrates.

Experiments were conducted to evaluate possible false signals generated by nonspecific carbon sources for application of the luminescence assay to in situ experiments such as saturated flow soil columns. MSB with no carbon substrate served as a negative control to indicate background luminescence levels, and 20 mg of sodium salicylate liter−1 was the positive control. Maximum luminescence produced by 4.6 × 107 stationary-phase cells in response to the nonspecific carbon sources evaluated was less than 0.1% of the signal produced by the same number of cells in response to 20 mg of sodium salicylate liter−1 (Table 1). No significant luminescence was detected in response to a 5-h incubation with the soil extract broth, and a maximum increase of 15 times background (from 48 to 749 cpm) was observed over the 5-h incubation period in the more complex medium, 50% LB. The maximum LB response (749 cpm) was still only half the luminescence peak generated by 55% the number of cells in response to 1 mg of sodium salicylate liter−1 (1,500 cpm [Fig. 3]). Thus, no significant interference from nonspecific carbon sources is anticipated during a typical 5-h assay period when analyzing substrate levels of 1 mg liter−1 or greater.

TABLE 1.

Effect of nonspecific carbon substrates on luminescence from RB1353

| Growth medium | Maximum luminescence ± SD (cpm) |

|---|---|

| MSB with no carbon substrate | 48 ± 9 |

| Soil extract broth | 77 ± 26 |

| 50% LB | 749 ± 30 |

| 20 mg of sodium salicylate liter−1 | 257,960 ± 130,539 |

Influence of lux genes on nah gene expression.

Potential impacts of the lux operon on expression of the nah genes were evaluated to assess possible negative aspects to its use as a bioreporter system. In a simultaneous salicylate degradation assay, the Vmax for RB1353 was found to be slightly lower than for the parent strain, PB2440 (2.7 and 3.1 mg liter−1 h−1, respectively), but the difference was insignificant compared to changes caused by factors such as growth stage, cell number, and substrate concentration. Growth phase experiments with the parent strain revealed a similar pattern to RB1353, with a higher Vmax observed from deceleration-phase cells than from stationary-phase cells (data not shown). Thus, the presence of the pUTK9 plasmid bearing the lux genes does not appear to have a significant effect on the degradative behavior of the engineered RB1353 strain under ambient conditions.

DO tension.

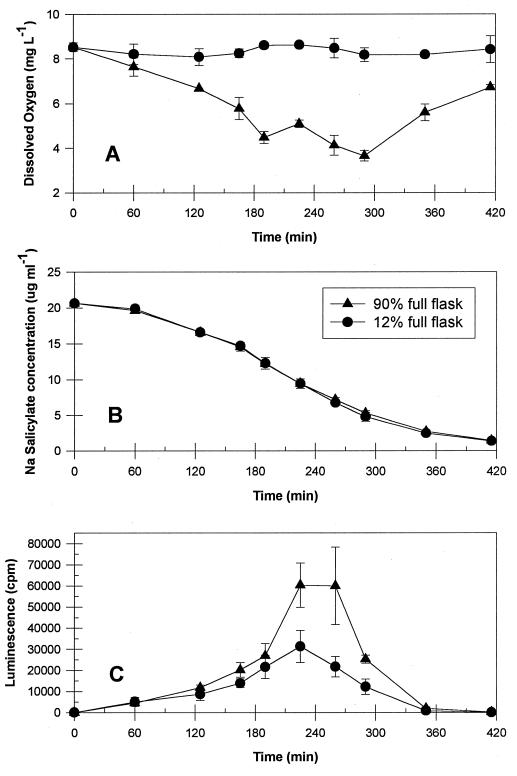

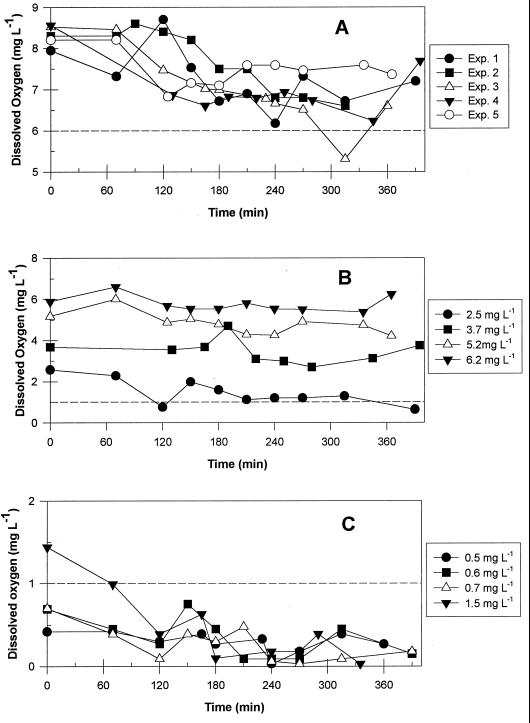

Results from the first oxygen experiment (Fig. 4A) show a significant drop in DO tension during incubation for flasks filled to 90% of capacity, while flasks filled to 12% maintained a fairly constant oxygen level. The lower oxygen levels in the former flasks had no effect on salicylate degradation behavior (Fig. 4B). Limited oxygen availability was most apparent when consumption was highest, most probably due to reduced diffusion rates through the liquid media. Diffusion through water is in the range of 10−5 cm2 s−1, compared to 10−3 cm2 s−1 for air (31). In contrast, the luminescence response was enhanced by the reduced oxygen availability (Fig. 4C). This response was in contrast to anticipated behavior based on the observation that for two different luminescent Photobacterium spp., the luciferase reaction required as much as 10 to 20% of the total available oxygen (6). This competition for oxygen between luciferase and other metabolic enzymes has been previously identified as a possible source of complex luminescence behavior (12). A similar enhancement was documented previously in Vibrio fischerii, the donor organism for the lux genes, but a simultaneous inhibition of glucose metabolism was also observed. These results led to the hypothesis that luciferase has a lower Km value for oxygen and therefore was functioning as a substitute for cytochrome as the terminal carrier of electrons to oxygen under microaerophilic conditions (6). However, for RB1353, substrate degradation was unaffected. Thus, the enhanced luminescence may be because the slightly reduced conditions in this system enhanced FMNH2 or aldehyde availability.

FIG. 4.

Effect of limited oxygen diffusion on DO concentration (A), sodium salicylate degradation (B), and luminescence (C) for RB1353 in response to 20 mg of sodium salicylate liter−1.

The observed influence of oxygen on the luminescence response led to a second series of five experiments with a range of initial DO concentrations. Vmax was calculated for each salicylate degradation curve and normalized with respect to the unsparged control treatment for each experiment to allow a comparison of data from all five experiments. The metabolic behavior of the unsparged control treatment was designated normal for ambient air conditions; thus, a value of 1.0 represents normal degradation behavior. For all five experiments, control vials maintained DO levels above 6.0 mg liter−1 throughout the assay (Fig. 5A). As detailed in Fig. 5B, vials with initial DO concentrations in the range from 2.5 to 6.2 mg liter−1 maintained fairly constant DO levels. In contrast, all initial DO treatments at or below 1.5 mg liter−1 resulted in DO levels below 1.0 mg liter−1 by the first sample time at 70 min (Fig. 5C).

FIG. 5.

DO concentrations during incubation for assays with different initial DO levels. (A) Unsparged controls; (B) initial DO concentrations of 2.5 to 6.2 mg liter; (C) initial DO concentrations less than or equal to 1.5 mg liter−1.

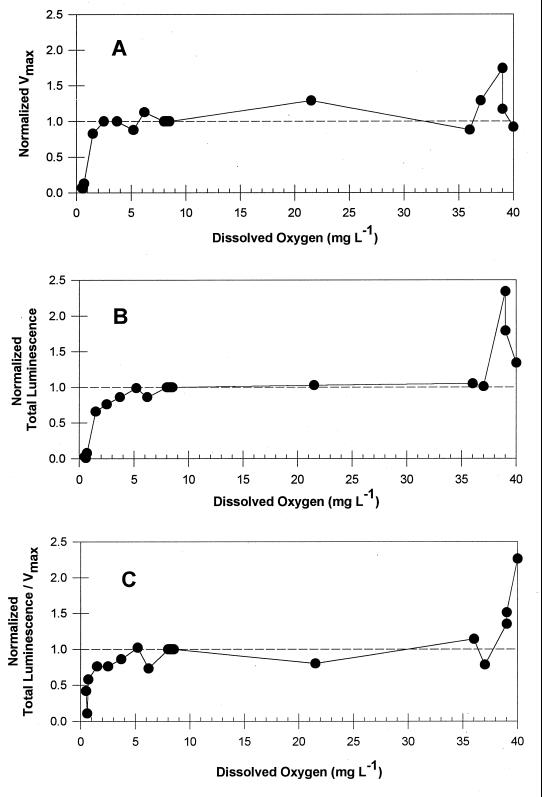

The data in Fig. 6A demonstrate that initial DO levels below 1 mg liter−1 significantly limited but did not completely inhibit salicylate degradation, while initial values of 2.5 mg liter−1 or greater had no effect on Vmax. Vials with initial DO levels of 1.5 mg liter−1 showed a slight reduction in Vmax. As indicated above, DO levels in these vials dropped below 1.0 mg liter−1 soon after initiation of the assay. These data suggest that DO levels greater than 1.5 mg liter−1 must be maintained to support normal degradation behavior on 20 mg of sodium salicylate liter−1. Some enhancement of Vmax was observed for treatments with DO levels greater than ambient (DO > 20 mg liter−1), but the results were not consistent.

FIG. 6.

Effect of initial DO levels on Vmax (A), total luminescence (B), and the ratio of luminescence to Vmax, (C) for RB1353 in response to 20 mg of sodium salicylate liter−1.

Similar effects were observed for luminescence behavior (Fig. 6B). Total rather than peak luminescence is reported for each DO treatment due to the difficulty in identifying the peak luminescence time for each of the various oxygen levels. Data were normalized for each treatment as described above for Vmax. As with Vmax, treatments with initial DO levels less than or equal to 1.5 mg liter−1 demonstrated moderate to severe but not total luminescence inhibition. However, unlike the Vmax data, luminescence inhibition continued at 2.5 and 3.7 mg liter−1, with normal behavior first occurring at 5.2 mg liter−1.

Finally, the ratio of total luminescence to Vmax was calculated and normalized as previously described to evaluate whether they were similarly inhibited. If the ratio is equal to 1, relative inhibition of Vmax and luminescence are the same, suggesting that the mechanism of inhibition is the same. If the ratio is <1, relative inhibition of luminescence is greater, suggesting that multiple mechanisms of inhibition may be operating. As shown in Fig. 6C, luminescence is more inhibited for all experiments with initial DO concentrations less than 5.2 mg liter−1. Upon closer examination of Fig. 6, it becomes apparent that in all cases luminescence is more inhibited than Vmax but that at low initial DO levels (<1.5 mg liter−1) both processes are substantially inhibited. Therefore, we suggest that a separate mechanism of inhibition exists for experiments with initial DO concentrations of 2.5 and 3.7 mg liter−1 while a combined mechanism of inhibition operates at levels less than or equal to 1.5 mg liter−1.

The decreased luminescence at initial DO levels from 2.5 to 3.7 mg liter−1 could be attributed to insufficient oxygen, but this explanation conflicts with observed results from the first study, where enhanced luminescence was observed in flasks where DO levels decreased to levels within the range from 3.5 to 5.5 mg liter−1 (Fig. 4). This observation emphasizes the fact that the critical factor is the initial DO level, not the DO level at the time the luminescence is expressed.

Regulation of biodegradation and luminescence expression.

One possible explanation for the observed effects of substrate and oxygen concentration on salicylate degradation and luminescence behavior can be found through an evaluation of the nahR regulatory system in combination with general bacterial global regulatory mechanisms. Bacterial cells must be able to adapt rapidly to a wide range of fluctuations in environmental conditions in order to survive. An important survival strategy involves the meticulous control of numerous operons to avoid the waste of energy resulting from the synthesis of excess mRNA or enzymes (28). Expression of the sal and lux genes in RB1353 is controlled by the lower-pathway promoter, Psal, and the upper-pathway promoter, Pnah, respectively (4). Both promoters have a site at bp −70 preceding the transcription start site that is recognized by the nahR gene regulatory protein (4). The nahR gene is transcribed constitutively, but the NahR protein is activated (NahRa) only following binding to the inducer, salicylate. Subsequent NahRa-concentration-dependent 10- to 50-fold increases in production of nah enzymes have been observed (33). Thus, it is logical that a linear relationship was observed between substrate concentration and both Vmax and luminescence.

Although the response of Vmax and luminescence to DO levels also appears to be controlled by transcription rate due to the parallel graduated response of the two enzyme systems, a different regulatory mechanism must be involved, since oxygen has no effect on the availability of salicylate, the inducing compound. The enzyme response at DO levels less than or equal to 1.5 mg liter−1 is attributed to regulated induction rather than constitutive expression because of the magnitude of the observed luminescence. Maximum constitutive expression of the lux genes (749 cpm), as determined by growth in rich medium (Table 1), is still more than 5 times lower than the peak luminescence generated from the lowest initial DO treatment of 0.5 mg liter−1 (3,904 cpm). Alternatively, this observed behavior could be attributed to a global regulatory system which exists to help a cell sense and respond to its redox environment in order to repress excess enzyme production at low oxygen levels. Such global mechanisms, which monitor cellular oxidative conditions and respond by adjusting the expression of a range of operons, have been identified in both E. coli (11) and Bacillus subtilis (20). One global mechanism identified in E. coli is the ArcAB (aerobic respiration control) system, a two-component system containing a sensor membrane protein and a DNA binding protein known to repress 17 and activate 9 operons. ArcA is a repressor whose DNA binding activity is stimulated following transphosphorylation by the sensor protein, ArcB, in response to reduced oxygen conditions. Such a two-component system could be functioning in RB1353, where an activated repressor protein such as ArcA competes with NahRa for the Psal and Pnah binding sites, thus repressing the induction rate of nah and lux genes. ResDE, a similar two-component signal transduction system, has been identified in B. subtilis. The ResDE system also plays an essential role in altering metabolic activity by regulating operons in response to oxygen availability (20).

An alternate mechanism could involve the global regulation of plasmid copy number in response to the cell redox potential. NAH7 is a large, low-copy-number plasmid, while pUTK9 is a smaller plasmid with a higher copy number (4). Thus, a greater potential exists for fluctuations in pUTK9 copy number, creating a subsequent effect on lux enzyme production. Although the plasmid copy number must be considered a potential factor influencing lux enzyme expression, no evidence currently exists for global regulation of plasmid copy number in response to cell redox potential, as has been found with the regulation of metabolic activity by the two-component systems described.

The ArcAB-type, two-component global regulatory system could also explain the conflicting luminescence results observed for DO tensions in the range from 3.5 to 5.5 mg liter−1 depending on the initial DO concentration in the experiment. Under the initial DO tensions of 3.5 to 5.5 mg liter−1 established in the second series of oxygen experiments, the reduced luminescence response could not be attributed to regulation of the sal and nah operons, since a parallel response was not observed in the Vmax data. However, alternate operons in the cell may have been partially repressed, affecting the availability of essential components for the luciferase reaction such as FMNH2 or the fatty acids required for conversion to the long-chain aldehyde. The FMN reductase, for example, is not subject to coinduction with luciferase (6) and thus could be regulated at a different rate. The ArcAB system in E. coli represses basic enzymes essential for aerobic respiration such as components of the tricarboxylic acid cycle (11) under conditions of limited oxygen availability. In contrast, production of such reaction components would not have been repressed at the initial DO levels of 8.5 mg liter−1 established in the first oxygen experiment. Even if the relevant pathways became repressed as the oxygen levels decreased in the 90% full flasks, the cell would have accumulated enough of the reaction components during the initial portion of the assay to maintain the enhanced levels of luminescence observed for a limited period.

In conclusion, the oxygen data demonstrates that in the presence of 20 mg of sodium salicylate liter−1, both luminescence and degradation in RB1353 are inhibited by initial DO tensions of 1.5 mg liter−1 or less. The majority of this inhibition can be attributed to regulated induction of the nah and sal promoters, but part of the luminescence inhibition is specific to the luciferase reaction itself, possibly associated with availability of reaction components as discussed above. At oxygen tensions from 2 to 4 mg liter−1, a slight repression in luminescence response can be expected despite normal degradation behavior if the cell has experienced this redox level for an extended period. Alternatively, if the cell experiences a sharp drop in available oxygen, an enhanced luminescence response can be expected over the same general oxygen range. At oxygen levels of 5.5 mg liter−1 or greater, the luminescence response to 20 mg of sodium salicylate liter−1 would follow the predicted behavior. Thus, care must be taken to monitor DO levels in a dynamic system and to identify the DO threshold below which luminescence response is inhibited. Although inhibition of luminescence may be greater than of Vmax at low DO concentrations, luminescence can still be used as an indicator of degradation inhibition in a dynamic system where oxygen is potentially limiting.

The present research demonstrates the value of lux bioreporters as tools not only to monitor real-time expression of specific pathways but also as indicators of metabolic activity in bacterial cells in response to changes in environmental conditions. More extensive work can be done to specifically model the influence on luminescence of a specific combination of environmental or physiological cell conditions which may be in flux in a dynamic system, but the model must be organism and application specific. Despite the necessity for such preliminary work, the possibilities offered by such luminescent reporters are extensive and unique.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This research was supported by grant DEB-9523870 from the National Science Foundation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Applegate B M, Kehrmeyer S R, Sayler G S. A chromosomally based tod-luxCDABE whole-cell reporter for benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene, and xylene (BTEX) sensing. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:2730–2735. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.7.2730-2735.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atlas R M. Handbook of microbiological media. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press, Inc.; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blouin K, Walker S G, Smit J, Turner R F B. Characterization of in vivo reporter systems for gene expression and biosensor applications based on luxAB luciferase genes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:2013–2021. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.6.2013-2021.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burlage R S, Sayler G S, Larimer F. Monitoring of naphthalene catabolism by bioluminescence with nah-lux transcriptional fusions. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:4749–4757. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.9.4749-4757.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4a.Burlage, R. S., et al. Personal communication.

- 5.de Weger L A, Dunbar P, Mahafee W F, Lugtenberg B J J, Sayler G S. Use of bioluminescence markers to detect Pseudomonas spp. in the rhizosphere. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:3641–3644. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.12.3641-3644.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hastings J W, Potrikus C J, Gupta S C, Kurfurst M, Makemson J C. Biochemistry and physiology of bioluminescent bacteria. Adv Microb Physiol. 1985;26:235–291. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2911(08)60398-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heitzer A, Malachowsky K, Thonnard J E, Bienkowski P R, White D C, Sayler G S. Optical biosensor for environmental on-line monitoring of naphthalene and salicylate bioavailability with an immobilized bioluminescent catabolic reporter bacterium. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:1487–1494. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.5.1487-1494.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heitzer A, Webb O F, Thonnard J E, Sayler G S. Specific and quantitative assessment of naphthalene and salicylate bioavailability by using a bioluminescent catabolic reporter bacterium. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:1839–1846. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.6.1839-1846.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herman D C, Zhang Y, Miller R M. Rhamnolipid (biosurfactant) effects on cell aggregation and biodegradation of residual hexadecane under saturated flow conditions. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:3622–3627. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.9.3622-3627.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hill P J, Rees C E D, Winson M K, Stewart G S A B. The application of lux genes. Biotechnol Appl Biochem. 1993;17:3–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iuchi S, Weiner L. Cellular and molecular physiology of Escherichia coli in the adaptation to aerobic environments. J Biochem. 1996;120:1055–1063. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a021519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.King J M H, DiGrazia P M, Applegate B, Burlage R, Sanseverino J, Dunbar P, Larimer F, Sayler G S. Rapid sensitive bioluminescent reporter technology for naphthalene exposure and biodegradation. Science. 1990;249:778–781. doi: 10.1126/science.249.4970.778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marlowe, E. M., R. M. Maier, and I. L. Pepper. 1999. An RT-PCR assay for evaluating gene expression as an index of biodegradation. J. Microbiol. Methods submitted.

- 14.Masson L, Comeau Y, Brousseau R, Samson R, Greer C. Construction and application of chromosomally integrated lac-lux gene markers to monitor the fate of a 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid-degrading bacterium in contaminated soils. Microb Releases. 1993;1:209–216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meighen E A. Enzymes and genes from the lux operons of bioluminescent bacteria. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1988;42:151–176. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meighen E A. Molecular aspects of bacterial bioluminescence. Microbiol Rev. 1991;55:123–142. doi: 10.1128/mr.55.1.123-142.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meikle A, Glover L A, Killham K, Prosser J I. Potential luminescence as an indicator of activation of genetically-modified Pseudomonas fluorescens in liquid culture and in soil. Soil Biol Biochem. 1994;26:747–755. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meikle A, Killham K, Prosser J I, Glover L A. Luminometric measurement of population activity of genetically modified Pseudomonas fluorescens in the soil. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1992;99:217–220. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(92)90029-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller R M. Surfactant-enhanced bioavailability of slightly soluble organic compounds. In: Skipper H, Turco R, editors. Bioremediation science and applications. Madison, Wis: Soil Science Society of America; 1995. pp. 33–54. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nakano N M, Zuber P. Anaerobic growth of a “strict aerobe” (Bacillus subtilis) Annu Rev Microbiol. 1998;52:165–190. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.52.1.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.National Research Council. In situ bioremediation: when does it work? Washington, D.C: National Academy Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patton G I, Campbell C D, Glover L A, Killham K. Assessment of bioavailability of heavy metals using lux modified constructs of Pseudomonas flourescens. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1995;20:52–56. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ramanathan S, Shi W P, Rosen B P, Daunert S. Bacteria-based chemiluminescence sensing system using β-galactosidase under the control of the ArsR regulatory protein of the ars operon. Anal Chim Acta. 1998;369:189–195. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rattray E A S, Prosser J I, Killham K, Glover L A. Luminescence-based nonextractive technique for in situ detection of Escherichia coli in soil. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:3368–3374. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.11.3368-3374.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Selifonova O V, Burlage R, Barkay T. Bioluminescent sensors for detection of bioavailable Hg(II) in the environment. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:3083–3090. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.9.3083-3090.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Selifonova O V, Eaton R W. Use of ibp-lux fusion to study regulation of the isopropylbenzene catabolism operon of Pseudomonas putida RE204 and to detect hydrophobic pollutants in the environment. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:778–783. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.3.778-783.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Simkins S, Alexander M. Models for mineralization kinetics with the variables of substrate concentration and population density. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1984;47:1299–1306. doi: 10.1128/aem.47.6.1299-1306.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Snyder L, Champness W. Molecular genetics of bacteria. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stewart G S A B, Williams P. lux genes and the applications of bacterial luminescence. J Gen Microbiol. 1992;138:1289–1300. doi: 10.1099/00221287-138-7-1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sticher P, Jaspers M C M, Stemmler K, Harms H, Zehnder A J B, van de Meer J R. Development and characterization of a whole-cell bioluminescent sensor for bioavailable middle-chain alkanes in contaminated ground water samples. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:4053–4060. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.10.4053-4060.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tiedje J M. Ecology of denitrification and dissimilatory nitrate reduction to ammonium in biology of anaerobic microorganisms. In: Zehnder A J B, editor. Biology of anaerobic microorganisms. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1988. pp. 179–244. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Willardson B M, Wilkins J F, Rand T A, Schupp J M, Hill K K, Keim P, Jackson P J. Development and testing of a bacterial biosensor for toluene-based environmental contaminants. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:1006–1012. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.3.1006-1012.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yen K, Serdar C M. Genetics of naphthalene catabolism in pseudomonads. Crit Rev Microbiol. 1988;15:247–268. doi: 10.3109/10408418809104459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang Y, Miller R M. Enhanced octadecane dispersion and biodegradation by a Pseudomonas rhamnolipid surfactant (biosurfactant) Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:3276–3282. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.10.3276-3282.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]