Abstract

Background

“Digital public health” has emerged from an interest in integrating digital technologies into public health. However, significant challenges which limit the scale and extent of this digital integration in various public health domains have been described. We summarized the literature about these challenges and identified strategies to overcome them.

Methods

We adopted Arksey and O’Malley's framework (2005) integrating adaptations by Levac et al. (2010). OVID Medline, Embase, Google Scholar, and 14 government and intergovernmental agency websites were searched using terms related to “digital” and “public health.” We included conceptual and explicit descriptions of digital technologies in public health published in English between 2000 and June 2020. We excluded primary research articles about digital health interventions. Data were extracted using a codebook created using the European Public Health Association's conceptual framework for digital public health.

Results and analysis

Overall, 163 publications were included from 6953 retrieved articles with the majority (64%, n = 105) published between 2015 and June 2020. Nontechnical challenges to digital integration in public health concerned ethics, policy and governance, health equity, resource gaps, and quality of evidence. Technical challenges included fragmented and unsustainable systems, lack of clear standards, unreliability of available data, infrastructure gaps, and workforce capacity gaps. Identified strategies included securing political commitment, intersectoral collaboration, economic investments, standardized ethical, legal, and regulatory frameworks, adaptive research and evaluation, health workforce capacity building, and transparent communication and public engagement.

Conclusion

Developing and implementing digital public health interventions requires efforts that leverage identified strategies to overcome diverse challenges encountered in integrating digital technologies in public health.

Keywords: Digital public health, digital health, public health, eHealth, mHealth

Introduction

The potential for digital technologies to improve the delivery and impact of public health interventions on the health and wellbeing of populations and communities is widely acknowledged.1–3 Interest in integrating digital technologies in health services has resulted in digital health as a field of practice, which has in turn been further adapted in public health as the evolving field of “digital public health.”2,4 The term “digital public health” became widely used after public health England (PHE) described its Digital-First Strategy in 2017, and it has been used in different ways to refer to the integration of digital technologies to advance or reimagine public health goals and functions, maximizing its impact on communities and populations by reaching more people with more efficiently delivered health services.2–5 Digital public health has been considered to be a promising strategy to tackle substantial modern public health challenges, including aging populations, the dual burden of noncommunicable and communicable diseases, and the health impacts of climate change, among others. 2

However, numerous challenges impede achieving these potential impacts of digital public health, 6 including policy and ethics-related dilemmas and complexities inherent with integrating specific digital technologies in public health.7,8 Many of these challenges apply to digital health generally and are not specific to digital public health. 9 However, public health action requires wide-ranging public engagement, a population health perspective, and prompt information exchange and cooperation across diverse organizations and public health agencies. These characteristics of public health services necessitate thinking specifically about challenges pertinent to integrating digital technologies within public health. Given that digital public health is in its nascent stages of development, it is critical to characterize these challenges and implement strategies to overcome them.6,7 Drawing on insights from published literature, we aimed to (1) describe shared challenges to integrating digital technologies across various public health domains, (2) summarize recommendations to overcome these shared challenges, and (3) identify common solutions that can form the core of a digital public health strategy. We hoped such a high-level description may help policy makers, public health practitioners, decision makers, and researchers to facilitate systems-level changes that enable a more considered development of digital public health strategies and services.

Methods

Overview

We conducted a scoping review to define the field of digital public health. Our methods and findings about the definition of the field have been described in detail elsewhere.5,10 Here we focus on the challenges and recommended solutions to support the development and implementation of digital public health interventions. We followed Arksey and O’Malley's framework for scoping reviews, 11 with adaptations suggested by Levac et al.. 12 Our reports adhere to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) for scoping reviews. 13

Data sources

Our search strategy (Appendix 1) was applied to MEDLINE [Ovid] and Embase [Ovid] to identify literature containing keywords related to both “digital” and “public health.” Our search strategy explored the intersection between digital health (and closely related domains, e.g. virtual health, mHealth, e-health, digitalization) and public health domains described by the Canadian Public Health Association (CPHA) (e.g. health promotion, surveillance, and epidemiology). 14 We reviewed publications that conceptually described digital technology in public health including expert opinions, commentaries, and reviews. We excluded primary research studies like trials and cross-sectional studies, given that our focus was on assessing the discourse around digital technologies in public health and not specifically on assessing any digital interventions in public health. 10 We included articles published in English between January 2000 and June 2020. Included titles and abstracts were exported to Covidence® for further review and citation management. 15

We also conducted a grey literature search on Google Scholar using the search terms: “digital” AND “public health.” This simplified search strategy was used due to lack of more precise search functions on Google Scholar. We further applied these terms on the Google search engine to inspect 14 pre-identified government and intergovernmental agency websites. 10 We reviewed the first 100 returns from Google Scholar and each website searched. Finally, manual reference list searches were conducted on included articles to identify additional publications.

Screening procedure

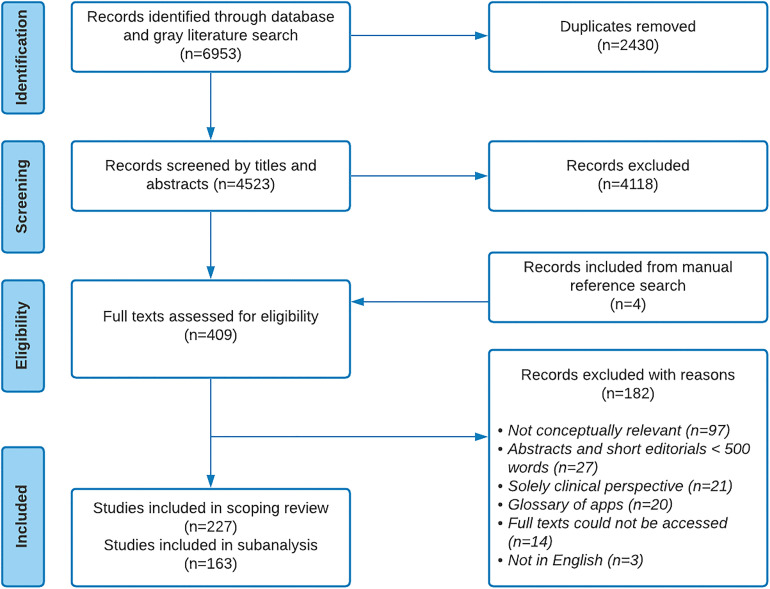

Pre-established inclusion and exclusion criteria were used during the title and abstract screening. 10 Articles that broadly conceptualized digital health from a population and public health perspective that were published in English between January 2000 and June 2020 were included (Table 1). We drew on the CPHA's definition of public health as “an organized effort of society to keep persons healthy and prevent injury, illness and premature death, including a combination of programs, services, and policies that protect and promote the health of all.” 14 Publications that evaluated specific health programs or interventions, focused solely on clinical perspectives, or short summaries of less than 500 words were excluded. Twenty-five percent of the titles and abstracts were independently screened by two reviewers (II and AX) in an iterative approach. Both reviewers met frequently to discuss discrepancies and achieve consensus. Once a general understanding of the procedure was achieved, the remaining titles and abstracts were screened by at least one reviewer. In the full-text screening, all included publications were independently screened by both reviewers using a structured framework (Appendix 2). All discrepancies were discussed among both reviewers until a consensus for inclusion or exclusion was achieved. For this analysis, we identified articles that broadly described challenges to the integration of digital technologies in various public health domains; and/or made recommendations about ways to effectively support the development and implementation of digital technologies in public health (a summary of the selection process is described in Figure 1).

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

| Parameter | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Phenomenon of interest | Publications that broadly conceptualize or analyze digital health from a public health perspective | Publications evaluating or describing specific digital health programs or interventions |

| Health context | Publications focusing on health issues at the population level including perspectives on preventive, community medicine, or public health (e.g. environmental health, obesity, diabetes, stigma, antibiotic resistance, prevention of sexually transmitted, and blood-borne infections) | Publications solely focused on the application of digital health in clinical contexts |

| Language | English | Not in English |

| Publication status | Published or grey literature | No full text, only abstract or short summary <500 words published |

| Year of publication | January 2000–June 2020 | None |

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) flow diagram of the search.

Data extraction and analysis

We imported included publications into QSR NVivo version 12TM and two reviewers (II and AX) independently extracted bibliographic characteristics including article type, publication year, country, and continent of institutional affiliation of the first author. Challenges described in developing digital technologies in public health and solutions recommended were extracted for each publication. Thereafter, we applied a thematic analysis to the text from included papers, following Braun and Clarke's recommendations for thematic analysis. 16 First data familiarization was done to understand the general challenges and recommendations discussed. Thereafter, we generated the initial codes using inducive techniques that were grounded in the data. We used similar or the same words used in the articles to generate the initial codes. We then searched through the codes for emergent themes describing the challenges and recommendations. The themes were then reviewed, renamed, and summarized as presented in this manuscript. 16

Results

We identified 163 articles discussing challenges with integrating digital technologies in public health and/or making recommendations on ways to surmount these challenges. Table 2 presents an overview of the characteristics of the 163 included articles. The majority of the publications (53.4% (87)) were review-type articles, 63.2% (103), were written by first authors based in North America (United States of America and Canada), and 64.4% (105) were published between 2015 and 2020.

Table 2.

Characteristics of included publications.

| Characteristics | Frequency (n = 163) | Percent (100%) |

|---|---|---|

| Article type | ||

| Commentary | 29 | 17.8 |

| Editorial | 17 | 10.4 |

| Report | 16 | 9.8 |

| Review | 87 | 53.4 |

| Others a | 14 | 8.6 |

| Country of the first author | ||

| USA | 84 | 51.5 |

| UK | 21 | 12.9 |

| Intergovernmental Organization | 7 | 4.3 |

| Canada | 18 | 11.0 |

| Australia | 8 | 4.9 |

| Switzerland | 5 | 3.1 |

| Others b | 20 | 12.3 |

| Continent | ||

| Asia | 6 | 3.7 |

| Europe | 41 | 25.2 |

| Transcontinental Organization | 5 | 3.7 |

| North America | 103 | 63.2 |

| Oceania | 8 | 4.9 |

| Years of publication | ||

| 2000–2004 | 9 | 5.5 |

| 2005–2009 | 12 | 7.4 |

| 2010–2014 | 37 | 22.7 |

| 2015–2020 | 105 | 64.4 |

Includes workshop and conference summary recommendations, policy statements, and glossary documents.

It includes Israel, Ireland, Norway, Italy, Cyprus, and Germany among others.

Emergent from our thematic analysis were two broad categories of challenges faced in digital public health: technical and nontechnical challenges. Technical challenges were defined as those related to the technologies and technologically related development and implementation processes relevant to integrating digital tools in public health. Nontechnical challenges referred to other issues pertinent to public health generally but that were emphasized when integrating digital technologies. While these demarcations are somewhat arbitrary and overlapping, we found it an intuitive framing to identify dominant perspectives in the literature. Technical challenges were discussed mainly from an engineering and technical perspective, while nontechnical challenges were discussed from a public health and social science perspective. Overall, nontechnical challenges were more prominently highlighted as key barriers to the development and implementation of digital public health interventions. Both technical and nontechnical challenges were often described as being interrelated and mutually reinforcing.

Nontechnical challenges

Ethical and legal issues

Articles highlighted ethical challenges to the use of digital technologies in public health related to data privacy, confidentiality, ownership, and security.17–21 Protecting individuals’ right to personal privacy and the confidentiality of their health information, preventing re-identification of individual-level data, and clarifying data ownership were described as challenges for the data integration required for public health functions.22–27 Related to data security, articles highlighted inconsistent data encryption standards especially across jurisdictions27–30 and varied ethical and legal traditions as a key barrier. 30 The risk of unauthorized data access and concerns about (mis)appropriation of data beyond consented uses, including for research and commercial purposes, were also emphasized.26,31,32,35,33 34 Additional ethical barriers include the potential identification of individual disease risks and exposures through digital technologies without clear remedies,36–38 perpetuation of stigma through data collection methods that do not acknowledge the existing context.24,39,40 Further concerns were expressed on the inherent shift in the responsibility of disease prevention and care from clinical and public health institutions to individuals as digital interventions may fail to acknowledge core structural issues that manifest as public health issues.41–43

Health equity

Closely related to the ethical issues, articles noted that numerous digital interventions in public health have not adequately considered health equity in their design.35,44–49 The most frequently reported health equity issue concerned the digital divide as expressed in two main ways. First, articles described disparities in access to digital technologies (including Internet services, smartphones, and computer systems) and use of digital health services based on gender, sexual orientation, age, education, ethnicity, urbanicity, and income.17,35,41,46–48,50–62 Further, disparities in digital health literacy, including users’ ability to understand and act on available digital information were highlighted as another major equity challenge.35,38,48,49,53,55,56,58,60–70

Further, digital technologies in public health may disproportionately benefit already privileged groups in society, and exclude marginalized populations.26,33,46,50,71,72 This may be further exacerbated through the economic incentive to target high-income users with commercial digital health interventions. 71 Other equity challenges described include disparities in the impact of overlooked potential consequences of digital technologies, such as data privacy breaches, data misuse, and biased algorithms leading to the perpetuation of stigma on marginalized populations.21,26,33,35,38,40,73,74 Widespread lack of digital health equity implementation frameworks and rigorous evaluation of the equity impacts of these digital technologies may further complicate equity challenges.36,44,45,73

Policy and governance challenges

Articles described challenges with policy keeping pace with evolving digital technologies in public health,20,23,26,40,50,63,64,75–79 resulting in reactive policies that are restrictive (often limiting data exchange), inadequate to support the development and implementation of digital technologies in public health,20,24,50,77,80 or not aligned with prevailing needs. 54 Governance challenges in supporting interjurisdictional digital interventions were also highlighted,20,22,29,30,50 especially for technologies not requiring in-person attendance. The transdisciplinary nature of digital public health interventions and the diversity of regulatory bodies involved in their development and implementation further reinforces the inadequacy of existing policy interventions.22,32,54,77

Paucity of high-quality evidence

The paucity of scientifically rigorous evidence on the real-world effectiveness of digital public health interventions in different contexts and for different populations was described as a significant challenge.33,35,36,40,45,46,77,81–87 Articles noted the inadequacy of cost–analysis evidence, specifically the costs of these interventions to individuals and health systems,36,64,77 and the mostly retrospective use of data in existing research that may be biased or have missing data. 87 Further, the iterative and fast-paced evolution of digital technologies is not matched by current research methods which are often rigid and slow to adapt.27,36,43,45,77,82,83,88,89 There is also a lack of widely agreed-upon standards for assessing outcomes55,90 and reliable outcome measures that extend beyond user engagement metrics.35,48,77,82,83,86,90,91 Further, interventions were frequently implemented on a small scale and their associated evaluations were described as poorly generalizable.48,92 Reliance on non-validated user-provided information was also said to reduce chances of successful follow-up in cases of attrition 93 and reduce the representativeness of data.83,93 Lastly, many digital public interventions were said not to be guided by known theory and lack sufficient documentation of their processes, making them difficult to replicate.43,94

Resource and economic interest barriers

The lack of long-term economic investments required to maintain essential infrastructure and human resources were said to complicate the sustainability of digital innovations in public health,21,50,54,63,64,84,94,95 especially with limited public health funding.19,26,49,50,78,96–102 Difficulties establishing clear cost–benefit outcomes and accountability strategies were also identified.48,97,101,103 These difficulties were reported to be worse among public health practitioners working in resource-limited settings. 73 Current innovations in public health were described as driven by commercial interests of for-profit organizations, often targeting populations serving these interests, worsening existing health disparities, and limiting opportunities for widespread impact in line with public health principles.2,50,71,76

Disinformation and misinformation

Articles described digital media, including social media as susceptible to the amplification of false and poor-quality health information, impacting health promotion efforts online.33–35,56,69,104,105 The nature of such platforms that leverage user-generated content35,51,62,106 with relative anonymity51,107 and unclear guidelines43,105 were said to spread unverified and often questionable information.34,43,51,52,108 Further, information overload on the public and the burden of health-information verification responsibilities placed on individuals was said to potentially worsen existing health disparities35,80,108,109 given that the capacity to verify the information is dependent on digital health literacy.69,110 Overall, the authors suggest that these challenges result in poor health behaviors and over-medicalization of common health problems,56,62,77,80,108 with public health practitioners struggling to control the messaging within these fast-moving media platforms. 95

Technological optimism

The overly enthusiastic assumption that digital technologies provide a catchall solution to public health challenges without due consideration of alternative approaches and foundational principles of public health was noted.18,38,40,111 Articles suggested that digital technologies may propagate a reductionist view on public health that ignores underlying social, economic, environmental, and commercial determinants of health, reducing their effectiveness.17,38,41,42,87,106,112 Further, inherent biases in assumptions and algorithms facilitating technologies like artificial intelligence, big data, and social media in public health were reported to potentially make them counterproductive to public health goals.21,28,36,47,113,114 These technologies were said to sometimes draw false associations and conclusions, perpetuate stigma, and widen health disparities.28,36,113,114

Technical challenges

Unreliability of available data

The heterogeneous nature of data sources and large volumes of data including epidemiologic, surveillance, and health services data required for public health services gathered across various health systems89,113,115–117 without broad standards for reporting and consistency was emphasized as a problem of data reliability.23,37,85,89,116,118–122 Further, data quality issues, including incomplete data, were said to be a challenge,24,40,120,123,124 especially for big data in public health surveillance and research, where noisy data (i.e. poor quality data) reduces efficiency.89,116,125 Further, the unreliability of unvalidated or anonymous user-generated and/or observational data52,56,79,80,83,91,92,118,126–128 were said to bias reports. For example, reports on social media could misrepresent the general public health situation, as significant portions of the population, including people suffering disparities in access to digital technologies, are excluded from the data.21,38,40,46,73,85,89,91,101,116,125,129,130

Fragmented, isolated, and unsustainable systems

A major challenge highlighted in the literature was the lack of coherent, coordinated, and integrated digital health architecture and coding standards across public health and allied agencies at the institutional and country-level, with proprietary systems that must be interoperable to support public health goals.22,23,26,28,50,103,121,131,132 This partly results from privacy and confidentiality concerns,22,37 and infrastructure/capacity gaps.22,123 Further disease and/or area-specific funding for digital interventions99,131 and ad hoc design of these systems were said to result in multiple isolated systems developed by different agencies and technology providers.4,27,31,133 The development and implementation of piecemeal interventions with limited funding that are sustainable and unable to harness economies of scale required to drive down operational costs were said to be characteristic of this problem. 26 Insufficient coordination and administrative barriers between agencies at all levels resulted in duplicated investments and low motivation for long-term investments.27,97,134

Leadership and health workforce capacity-building gaps

We found that strong technical leadership is crucial to facilitating the transformational change required to navigate complex, multifaceted, multi-stakeholder contexts critical for integrating digital technologies in public health.17,96,97 Public health practitioners have been noted to lack the technical training and experience necessary to make strategic decisions about information technologies and implement these systems. 22 The public health workforce has also been noted to lack the requisite technical expertise to benefit fromthe potential advantages of digital technologies in public health.22,37,43,63,64,73,98,99,123,131,135 Public health agencies are said to have challenges with engaging and retaining highly demanded tech-savvy public health analysts.37,40,99,123 New skills will be required in the public health workforce, including data manipulation, data mining, business analysis, project management, and social media communication, which is outside the current job descriptions of most public health workers.25,37,54,73,110,136 The public health workforce has not been supported to develop these capacities at the same pace as the push for development of the technologies required in digital public health. Health workers have also shown limited trust in digital technologies and a reluctance to learn new digital skills given concerns about the potential adverse effects on the public's interaction with health systems and the feeling of being unprepared to engage new systems.22,133,137

Infrastructure gaps

Public health increasingly relies on complex, high-volume data from heterogenous sources. Ensuring the promise of better public health precision in a digital era imposes new infrastructure requirements to enable operations.22,73,118,132,138,139 More robust computing infrastructure,25,64,132,138 including high-bandwidth, low-latency computer networks and clusters of machines for computation19,25,60 are required to take advantage of high-volume data. This was mostly emphasized in the use of big data and artificial intelligence for public health surveillance, epidemiology, and research. Capacity for ongoing maintenance of infrastructure and access to repair parts also constitute a barrier. 98 Many public health agencies lack access to such computing or IT power. Further, in resource-limited settings, unreliable power supply is a complicating factor.36,98 In addition to providers, public health service users also require access to computers, smartphones, and Internet services, which are often disparately distributed along socioeconomic gradients. These infrastructure requirements are closely related to funding and human resource needs, as the development of infrastructure needed to implement effective information systems has been slow, especially in financially limited local health departments. 22

Lack of clear consensus on operations standards

The lack of clear consensus on operations standards demonstrates the nascent nature of digital technologies in public health. 135 Considering the heterogeneity of data required for public health functions, reporting standards are required to effectively pool data; however, these standards are yet to be developed.22,36,134,140 Standards in vocabulary and health information exchange and coordination are lacking, resulting in suboptimal interoperability of varied systems relevant to public health functions.4,22,64,103,141 Standards for evaluating the impact of digital technologies on health outcomes are also suboptimal. 55 Where there are standards, public health professionals have been shown to have suboptimal awareness of existing data reporting standards 22 and data quality requirements across systems.36,64,108,136

Suboptimal design and implementation of digital technologies

Many digital technologies in public health are characterized by overenthusiastic and sometimes complex designs that neglect basic foundations of digital health, including attention to users’ needs rather than needs perceived by the implementers, and implementation of interventions that are based on proven behavioral theories.45,49,51,87,142–144 Further, the focus on using digital interventions for data collection, without due consideration to the value they might offer to frontline health providers and other user potentially limits engagement.30,142,145 User contexts have also been oversimplified and not well accounted for in the development of digital tools, with limited evaluation of the usability and acceptability of the tools among targeted users.122,142

Mapped solutions to overcome technical and nontechnical challenges

Potential solutions, as described in the literature, are summarized in Table 3. We identified seven overarching themes suggested to surmount technical and nontechnical challenges in digital public health.

Table 3.

Challenges to integrating digital technologies in public health and mapped solutions as identified in the literature.

| Challenges | Mapped recommendations |

|---|---|

| Nontechnical challenges | |

| Ethical, legal, and privacy issues |

|

| Paucity of high-quality evidence |

|

| Health equity |

|

| Policy and governance challenges | |

| Resource barriers |

|

| Disinformation and misinformation |

|

| Technological optimism | |

| Technical challenges | |

| Unreliability of available data | |

| Fragmented, isolated, and unsustainable systems | |

| Leadership and health workforce capacity-building gaps | |

| Infrastructure gaps | |

| Lack of clear standards |

|

| Suboptimal design and implementation of digital technologies |

|

Indicates recurring recommendations to address multiple challenges identified.

Political commitment

The importance of political commitments of governments and leaders to implement digital public health strategies across jurisdictions was emphasized.22,121,146 Political commitment is important to surmount resource barriers and foster the development and implementation of ethical, legal, and governance frameworks required for the seamless development of digital public health systems.66,97,147,148 The argument for political commitment is premised on potentially improved public health outcomes and reduced health costs through the provision of accurate and timely aggregate-level data to support decision making. 22 This multi-institutional commitment must include a wide range of stakeholders including the government, private sector organizations, nonprofit organizations, engineers, innovators, academia, research institutes, health care providers, and other government institutions.97,121

Intersectoral transdisciplinary partnerships

Intersectoral and transdisciplinary partnerships between governments, academics, public health practice, and industry partners were recommended to maximize currently available resources through resource pooling, shared expertise, and shared priority setting across jurisdictions.27,53,145,148 Such partnerships were also deemed important for creating coherent and coordinated interoperability, governance, and research frameworks, and garnering required resources, knowledge, and capacities to harness the potential of digital public health interventions.22,97,98,117,149 Such partnerships can help agencies and organizations leverage their comparative advantage and circumvent their own restraints. 21 The importance of these partnerships in securing political commitment to ensure that digital interventions move beyond pilot interventions to bringing them at scale was also emphasized.97,148

Economic investments

Significant economic investments were shown to be relevant to the development and implementation of digital public health. Investments must be planned for sustainability, ensuring funding across the project life-cycle and beyond pilot phases.40,84,148–150 Phased planning of interventions with funding for each cycle of implementation was also suggested.22,145 Opportunities to share risks through integrated planning and pooled resources across the public and private sectors must be explored.22,150 The importance of investing in interventions that improve the health equity outcomes of populations, including securing access to Internet services and publicly available digital access points, were also discussed.21,151 Such investments must be backed by evidence of the cost-effectiveness of interventions which also require investments in research and evaluation.22,40,77,134,146

Standardized ethical, legal, and regulatory frameworks

Establishing standardized ethical, legal, and regulatory frameworks was recommended as a pivotal aspect of facilitating the development and implementation of digital public health interventions. These frameworks should ensure a balance between innovation and ethics and social justice principles of public health.66,77,148 Standardized reporting systems and requirements,22,77,145 data quality standards, and shared digital architecture22,23,77,144,145 were suggested as mechanisms to ensure reliable and interoperable data systems to foster improved use of data for decision making. Articles highlighted the importance of widespread partnerships, coordinating frameworks, advisory, and oversight bodies at all levels.22,45,145,149,152 Members of the public served by these interventions should be involved beyond just consultation, ensuring their collaboration in the development and implementation of interventions. 67 This also involves wide-ranging collaboration and action among government agencies, in partnership with other stakeholders, to ensure that data governance and accountability frameworks are adaptable, proactive, and person-centered.23,40,66,145,146,153,154

Health workforce capacity building

Building capacity of the health workforce was suggested to help surmount both technical and nontechnical challenges. Capacity building is needed for workers to proactively identify digital infrastructure gaps, take advantage of available infrastructure, and maximize the impact of digital public health interventions.19,98,146 Ensuring the integration of digital technologies into existing public health training curricula can reduce data quality issues, inform design of relevant frameworks, and improve the capacity to manage ever-increasing volumes of health data. 19 Articles suggest that such curricula may be made open through communities of practice and interdisciplinary workforce exchanges to foster equitable knowledge uptake.21,98 Further, a deliberate effort to integrate diversity into health workforce capacity-building plans is also recommended to foster equity in the design and implementation of digital public health interventions.73,98 Others recommend updated job descriptions during recruitment that seek to bridge diverse fields involved in digital public health, including data science, engineering, health monitoring, and public health.4,116

Adaptive and comprehensive research and evaluation

The development and implementation of digital public health interventions was reported to require the articulation of a clear research agenda that focuses on generating high-quality evidence to support ongoing investment in the field at all local, national, and international levels.22,38,40,48,134,145,146 New methodology suitable for the peculiar pace of development and application of digital technologies, with appropriate measures of health outcomes, are also required to advance research and evaluation in digital public health.21,27,40,48,58,77,146,149,152 Mechanisms for actively sharing these methods were emphasized, including networks and inter-sectorial communities of practice. 27 Research and development of new privacy, data sharing, and governance frameworks relevant to digital public health were also recommended.30,40,117,136,149 Further, recommendations involved integrating research and evaluation in all stages of development and implementation of digital interventions. 77 These recommendations also highlight the importance of reporting outcomes of digital interventions disaggregated by factors including gender, race, ethnicity, age, and socioeconomic status to inform adaptations to improve health equity.44,72,134,145

Transparent communication and public engagement

Having a clear and transparent communication strategy was recommended in the literature to build trust and engagement between implementers and public health users. Transparency is recommended between stakeholders to ensure clear ownership and governance structures for fair data access, maintenance of security, and inclusion.26,66,98,124,138,149 Open science, equity-based frameworks were also recommended with a focus on including outcomes for marginalized populations in publications.23,111 Proactive public communication strategies are also recommended to mitigate the risk of public mistrust of digital interventions within this trust model. Such strategies must communicate clear and evaluable benefits of digital public health interventions, including data sharing, and proactively address the potential for misinformation to the public (including health care workers).21,26,30,66,69,77,86,152 Engagement strategies must also consider populations that suffer disparities to foster trust and ensure health equity.17,98

Discussion

This scoping review provides a high-level description of the challenges faced by digital public health practitioners and identifies broad-level recommendations to address these challenges. Our review expands on an existing review 2 and describes multiple, complex, and interrelated technical and nontechnical challenges in digital public health. Nontechnical challenges regarding ethics, paucity of evidence, equity, policy and governance concerns, and resource barriers dominate the discourse. Technical challenges including unreliability of data, fragmented, isolated, and unsustainable systems, leadership and health workforce capacity gaps, infrastructure gaps, and a lack of clear standards also constitute significant barriers to integration of digital technologies in public health. Seven recurring recommendations were identified to address these challenges, including securing political commitment, intersectoral transdisciplinary collaboration, economic investments, standardized ethical, legal, and regulatory frameworks, adaptive and comprehensive research and evaluation, health workforce capacity building, and transparent communication and public engagement.

These challenges have been well documented in reference to specific domains of public health.6,7,115,155 For example, privacy and security issues have been documented in relation to public health surveillance. Findings from our review underscore the complexity involved with digital public health and the interrelated challenges previously described in other studies. 2 The findings of our review also underscore cross-cutting themes related to the ethical integration of digital technologies across the domains of public health as described in most of the challenges identified. Further, our high-level description of the challenges extends the literature by mapping out recommended solutions to these challenges, summarily providing actionable strategies that public health policy makers, practitioners, and researchers may explore to foster cohesive and effective development of digital public health. These identified solutions which we refer to as key pillars of digital public health, validate suggestions made by the European Public Health Association (EUPHA). 2 These pillars must be closely considered in tandem with the foundational principles guiding public health practice to create a clear agenda for the ongoing development of the field (Figure 2). 14

Figure 2.

Mutually reinforcing pillars of digital public health.

The COVID-19 pandemic has fostered an unprecedented level of political commitment to identify strategies to optimally harness the potential of digital technologies in public health. 156 This is a crucial opportunity for policy makers, public health practitioners, and researchers to envision digital public health in a cohesive manner.157,158 Leveraging these key pillars as a central aspect of a digital public health strategy can be an effective starting point to ensure the successful development of the field. In envisioning and implementing digital technologies, the importance of aspiring for deep-rooted inter-sectorial transdisciplinary partnerships across traditional public health practices, and nontraditional fields including engineering, computer science, ethics, and behavioral sciences cannot be overstated.4,6,136 The defining feature of these transdisciplinary partnerships is the transcendence of disciplinary perspectives and boundaries (across academia and industry) in a systemic manner that involves practical participatory engagement with real-world problems to create feasible, socially acceptable, effective, and sustainable solutions.159,160 However, we must note that achieving transdisciplinary partnerships will be challenging given differences in vocabulary across disciplines and varied epistemological viewpoints that guide practice and research. 159

Moreover, in creating these partnerships, we must clarify the role of private sector players in digital public health. 7 Existing concerns about commercial interests have been a source of public distrust of digital public health interventions and must be addressed using established principles guiding public health practice.21,73,121,147 Further, standardized ethical, legal, and regulatory frameworks are required to ensure seamless, secure data exchanges between health agencies and authorities. Creating these normative frameworks will be complex, as the literature has highlighted multiple barriers to their establishment. For example, the interjurisdictional coverage of digital public health approaches implies that there must be political engagement to facilitate these frameworks.146,161 Yet, resistance to these new approaches within public health and the tendency to suppress data especially with suboptimal interventions, introduce additional challenges that must be navigated. 3 The speed of technological development must also be considered in these frameworks.

Standardized regulatory frameworks and policies centered on foundational public health principles must be informed by evidence. There is a need for adaptive research and evaluation frameworks, as well as a comprehensive agenda to guide the development and implementation of digital interventions in public health. Such adaptive research must respond to the implementing context and balance research and rigor with a need for data especially on technology that is rapidly evolving. 21 An iterative approach that leverages a wide range of methodologies has been recommended to ensure that these divergent concerns are addressed. 77 Further, adaptive health technology assessment models have been suggested in the context of public health emergencies like COVID-19. 162 However, given the evolving nature of digital technologies in public health, it is recommended that adaptive research and evaluation methods should the standard. 162 Further, for pragmatic policies to be made and implemented appropriately, public health policy makers, practitioners, and researchers will require continued education on new working methods in a digital environment. Considering low public trust in digital technologies generally, there is a need for proactive communication and engagement strategies to foster the growth of digital public health. Such proactive strategies are also necessary to stem the tide of misinformation and disinformation facilitated through digital technology.52,154 There is an ethical imperative to implement such strategies as misinformation and disinformation amplified through digital technology has significant public health consequences.

Limitations

Given the broad scope of this review, a more in-depth discussion of the challenges and recommendations was not practical. We focus here on broad-level challenges which may inadvertently leave out some of the more specific complexities within domains of public health and digital technologies employed. Further, considering that this is a sub-analysis of a larger scoping review to define digital public health, we acknowledge that the search strategy may not be specific enough and may have inadvertently excluded some relevant literature that provides provide an in-depth understanding of the challenges of integrating digital technologies in specific domains of public health. However, given the high-level aims of the review, we remain confident that the breadth of literature included gives a clear understanding of the broad challenges inherent in the field. Finally, our search was conducted in 2020. As such, additional insight may be available in more recent literature exploring digital technologies in the public health response to COVID-19.163,164 However, we remain confident that the broad challenges and strategies identified in this review remain relevant in our current context.

Conclusion

Despite growing interest in digital public health, a plethora of complex, evolving, and interrelated technical and nontechnical challenges hinder the ongoing development and implementation of digital interventions in public health. To foster a stronger approach to the development and implementation of digital public health, consolidated efforts are required to facilitate the comprehensive integration of digital technologies in public health at a scale that improves health outcomes for all. These efforts may leverage the seven key pillars identified in this review, including securing political commitment, inter-sectorial collaboration, economic investments, standardized ethical, legal, and regulatory frameworks, adaptive and comprehensive research and evaluation, health workforce capacity building, and transparent communication and public engagement. These key pillars may be considered as a roadmap to inform stronger and more evidence-based development of digital public health interventions.

Acknowledgments

The authors would also like to acknowledge Ursula Ellis, a University of British Columbia librarian who advised the research team on the search strategy used, and the members of the Clinical Prevention Services division at the British Columbia Centre for Disease Control, Vancouver, British Columbia, who provided critical feedback throughout the review process.

Appendix

Appendix 1. Search strategy

Database; Ovid MEDLINE(R) and Epub Ahead of Print, In-Process, and Other Non-Indexed Citations, published from 2000 to 1 June 2020

Search was conducted on 1 June; all languages included.

| Searches |

|---|

| 1. (mhealth or m-health).mp. [mp = title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, floating sub-heading word, keyword heading word, organism supplementary concept word, protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier, synonyms] |

| 2. virtual health.mp. |

| 3. mobile health.mp. |

| 4. (ehealth or e-health).mp. [mp = title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, floating sub-heading word, keyword heading word, organism supplementary concept word, protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier, synonyms] |

| 5. online health.mp. |

| 6. internet-based health.mp. |

| 7. computer-based health.mp. |

| 8. digit*.tw. |

| 9. electronic health.tw. |

| 10. health informatics.mp. |

| 11. web-based*.tw. |

| 12. telehealth.mp. |

| 13. Telemedicine/ |

| 14. Social Media/ |

| 15. predictive algorithms.mp. |

| 16. machine learning methods.mp. |

| 17. Machine Learning/ |

| 18. Big Data/ |

| 19. public health*.tw. |

| 20. Health Promotion/ |

| 21. health prevention.mp. |

| 22. health protection.mp. |

| 23. Health Policy/ |

| 24. health determinants.mp. |

| 25. Population Surveillance/ |

| 26. health evaluation.mp. |

| 27. health economics.mp. |

| 28. Risk Assessment/ |

| 29. Epidemiology/ |

| 30. community health.mp. |

| 31. emergency preparedness.mp. |

| 32. emergency response.mp. |

| 33. Health Equity/ |

| 34. Social Justice/ |

| 35. social determinants.mp. |

| 36. Artificial Intelligence/ |

| 37. digital public health.mp. |

| 38. digital health.mp. |

| 39. digitalization.mp. |

| 40. digital tools.mp. |

| 41. digital technologies.mp. |

| 42. web-based health.mp. |

| 43. 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 9 or 10 or 12 or 14 or 15 or 16 or 18 or 36 or 37 or 38 or 39 or 40 or 41 or 42 |

| 44. 19 or 20 or 21 or 22 or 23 or 24 or 25 or 26 or 27 or 28 or 29 or 30 or 31 or 32 or 33 or 34 or 35 |

| 45. 43 and 44 |

| 46. ((mhealth or m-health or virtual health or mobile health or (ehealth or e-health) or online health or internet-based health or computer-based health or electronic health or health informatics or telehealth or Social Media or predictive algorithms or machine learning methods or Big Data or Artificial Intelligence or digital public health or digital health or digitalization or digital tools or digital technologies or web-based health) and (public health* or Health Promotion or health prevention or health protection or Health Policy or health determinants or Population Surveillance or health evaluation or health economics or Risk Assessment or Epidemiology or community health or emergency preparedness or emergency response or Health Equity or Social Justice or social determinants)).tw. |

| 47. limit 46 to (english language and yr = "2000 -Current”) |

| 48. Public Health/ |

| 49. public health ethics.mp. |

| 50. 20 or 21 or 22 or 23 or 24 or 25 or 26 or 27 or 28 or 29 or 30 or 31 or 32 or 33 or 34 or 35 or 48 or 49 |

| 51. 43 and 50 |

| 52. ((mhealth or m-health or virtual health or mobile health or (ehealth or e-health) or online health or internet-based health or computer-based health or electronic health or health informatics or telehealth or Social Media or predictive algorithms or machine learning methods or Big Data or Artificial Intelligence or digital public health or digital health or digitalization or digital tools or digital technologies or web-based health) and (Health Promotion or health prevention or health protection or Health Policy or health determinants or Population Surveillance or health evaluation or health economics or Risk Assessment or Epidemiology or community health or emergency preparedness or emergency response or Health Equity or Social Justice or social determinants or Public Health or public health ethics)).tw. |

| 53. limit 52 to (english language and yr = "2000 -Current”) |

| 54. 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 10 or 12 or 14 or 15 or 16 or 18 or 36 or 37 or 38 or 39 or 40 or 41 or 42 |

| 55. 50 and 54 |

| 56. ((Health Promotion or health prevention or health protection or Health Policy or health determinants or Population Surveillance or health evaluation or health economics or Risk Assessment or Epidemiology or community health or emergency preparedness or emergency response or Health Equity or Social Justice or social determinants or Public Health or public health ethics) and (mhealth or m-health or virtual health or mobile health or (ehealth or e-health) or online health or internet-based health or computer-based health or health informatics or telehealth or Social Media or predictive algorithms or machine learning methods or Big Data or Artificial Intelligence or digital public health or digital health or digitalization or digital tools or digital technologies or web-based health)).tw. |

| 57. limit 56 to (english language and yr = "2000 -Current”) |

| 58. Public Health Surveillance/ |

| 59. 20 or 21 or 22 or 23 or 24 or 26 or 27 or 28 or 29 or 30 or 31 or 32 or 33 or 34 or 35 or 48 or 49 or 58 |

| 60. 54 and 59 |

| 61. ((mhealth or m-health or virtual health or mobile health or (ehealth or e-health) or online health or internet-based health or computer-based health or health informatics or telehealth or Social Media or predictive algorithms or machine learning methods or Big Data or Artificial Intelligence or digital public health or digital health or digitalization or digital tools or digital technologies or web-based health) and (Health Promotion or health prevention or health protection or Health Policy or health determinants or health evaluation or health economics or Risk Assessment or Epidemiology or community health or emergency preparedness or emergency response or Health Equity or Social Justice or social determinants or Public Health or public health ethics or Public Health Surveillance)).tw. |

| 62. limit 61 to (english language and yr = "2000 -Current”) |

| 63. 61 not “trial”.mp. [mp = title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, floating sub-heading word, keyword heading word, organism supplementary concept word, protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier, synonyms] |

| 64. 63 not “cross-sectional”.mp. [mp = title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, floating sub-heading word, keyword heading word, organism supplementary concept word, protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier, synonyms] |

| 65. limit 64 to (english language and yr = "2000 -Current”) |

Appendix 2. Framework for full-text review

- 1. Was access gained to the full paper of the citation

- □ Yes, full paper accessed1

- □ No, full text could not be downloaded2

- □ Only abstract available or full article less than 500 words3

If yes to step 1, move to step 2, else stop the review and indicate reason for exclusion

- 2. Is the full text in English?

- □ Yes3

- □ No4

If option 3 (yes) is selected, move to step to the next step, else stop the review and indicate reason for exclusion as “Language not English”

- 3. Does the paper broadly conceptualize and/or analyze a digital health intervention/application from any public health perspective (as described in the CPHA framework)? 1

- □ Yes, it is a commentary/narrative review/systematic review broadly applying digital health in public health5

- □ Yes, it presents a conceptual analysis of digital health in public health, but as a section of a broader public health or digital health discussion6

- □ No, it is a primary study or presents a report of a specific digital health intervention7

- □ No, it is a commentary focusing entirely on describing a specific digital health intervention8

- □ No, it is a systematic review that presents a glossary of specific digital health interventions9

- □ No, it discusses digital health entirely from a clinical perspective10

- □ Can't tell11

If option 5 or 6 is selected, including the paper, else exclude and indicate “not conceptual” for options 7–9, or “clinical/technical perspective” for option 10. If option 11 is selected, indicate “maybe” and discuss with the co-reviewer.

In some of the papers, the CPHA dimensions may not be explicitly stated. Using our own judgement and knowledge of public health will be useful in determining the relevance of the paper to this study. For example, a digital health intervention may be described in “disaster preparedness” which is not directly described in the framework, but it aligns with emergency response. This kind of paper can be included if the other inclusion criteria are met.

Footnotes

Author contributions

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Contributorship: II, OGR, and MG conceived and designed the study. OGR developed the protocol with input from all the authors, II and AX conducted the literature review and data analysis, II wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethical approval: Not applicable, because this article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Foundation for Population and Public Health at the British Columbia Center for Disease Control.

Guarantor: MG.

Informed consent: Not applicable, because this article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects.

ORCID iDs: Ihoghosa Iyamu https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0271-9468

Oralia Gómez-Ramírez https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6632-564X

Trial registration: Not applicable, because this article does not contain any clinical trials.

References

- 1.World Health Organization (WHO). Draft global strategy on digital health 2020–2024. Geneva, Switzerland, https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/documents/gs4dhdaa2a9f352b0445bafbc79ca799dce4d.pdf (2020, accessed 20 July 2020). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Odone A, Buttigieg S, Ricciardi W, et al. Public health digitalization in Europe. Eur J Public Health 2019; 29: 28–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murray CJL, Alamro NMS, Hwang H, et al. Digital public health and COVID-19. Lancet Public Heal 2020; 5: e469–e470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Public Health England. Digital-first public health: public health England’s digital strategy. London, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/digital-first-public-health/digital-first-public-health-public-health-englands-digital-strategy (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iyamu I, Xu AXT, Gómez-Ramírez O, et al. Defining digital public health and the role of digitization, digitalization, and digital transformation: scoping review. JMIR Public Heal Surveill 2021; 7: e30399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kostkova P. Grand challenges in digital health. Front Public Heal 2015; 3: 134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cummins N, Schuller BW. Five crucial challenges in digital health. Front Digit Heal 2020; 2: 536203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guo C, Ashrafian H, Ghafur S, et al. Challenges for the evaluation of digital health solutions—A call for innovative evidence generation approaches. npj Digit Med 2020; 3: 110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vial G. Understanding digital transformation: a review and a research agenda. J Strateg Inf Syst 2019; 28: 118–144. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iyamu I, Gómez-Ramírez O, Xu AXT, et al. Defining the scope of digital public health and its implications for policy, practice, and research: protocol for a scoping review. JMIR Res Protoc 2021; 10: e27686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol 2005; 8: 19–32. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci 2010; 5: 69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018; 169: 467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Canadian Public Health Association, The Canadian Public Health Association, Canadian Public Health Association. Public health: a conceptual framework. Ottawa, https://www.cpha.ca/sites/default/files/uploads/resources/cannabis/cpha_public_health_conceptual_framework_e.pdf (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Veritas Health Innovation. Covidence systematic review software, www.covidence.org.

- 16.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006; 3: 77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Katapally TR. A global digital citizen science policy to tackle pandemics like COVID-19. J Med Internet Res 2020; 22: e19357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fuller D, Buote R, Stanley K. A glossary for big data in population and public health: discussion and commentary on terminology and research methods. J Epidemiol Community Health 2017; 71: 1113–1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yasnoff WA, Overhage JM, Humphreys BL, et al. A national agenda for public health informatics. J Public Health Manag Pract 2001; 7: 1–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scott RE, Jennett P, Yeo M. Access and authorisation in a glocal e-health policy context. Int J Med Inform 2004; 73: 259–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee EWJJ, Viswanath K. Big data in context: addressing the twin perils of data absenteeism and chauvinism in the context of health disparities research. J Med Internet Res 2020; 22: e16377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yasnoff WA, Overhage JM, Humphreys BL, et al. A national agenda for public health informatics: summarized recommendations from the 2001 AMIA Spring Congress. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2001; 8: 535–545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mählmann L, Reumann M, Evangelatos N, et al. Big data for public health policy-making: policy empowerment. Public Health Genomics 2017; 20: 312–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ravi D, Wong C, Deligianni F, et al. Deep learning for health informatics. IEEE J Biomed Heal Informatics 2017; 21: 4–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Salathé M, Bengtsson L, Bodnar TJ, et al. Digital epidemiology. PLoS Comput Biol 2012; 8: e1002616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bublitz F M, Oetomo A, Sahu K S, et al. Disruptive technologies for environment and health research: an overview of artificial intelligence, blockchain, and internet of things. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019; 16: 1–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tate EB, Spruijt-Metz D, O’Reilly G, et al. Mhealth approaches to child obesity prevention: successes, unique challenges, and next directions. Transl Behav Med 2013; 3: 406–415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bu DD, Liu SH, Liu B, et al. Achieving value in population health big data. J Gen Intern Med 2020; 35: 3342–3345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Myers J, Frieden TR, Bherwani KM, et al. Ethics in public health research. Am J Public Health 2008; 98: 793–801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rynning E. Public trust and privacy in shared electronic health records. Eur J Health Law 2007; 14: 105–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fitzpatrick F, Doherty A, Lacey G. Using artificial intelligence in infection prevention. Curr Treat Options Infect Dis 2020; 12: 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fonseka TM, Bhat V, Kennedy SH. The utility of artificial intelligence in suicide risk prediction and the management of suicidal behaviors. Aust New Zeal J Psychiatry 2019; 53: 954–964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McKee M, van Schalkwyk MCI, Stuckler D. The second information revolution: digitalization brings opportunities and concerns for public health. Eur J Public Health 2019; 29: 3–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gill HK, Gill N, Young SD. Online technologies for health information and education: a literature review. J Consum Health Internet 2013; 17: 139–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McGloin AF, Eslami S. Digital and social media opportunities for dietary behaviour change. Proc Nutr Soc 2015; 74: 139–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schwalbe N, Wahl B. Artificial intelligence and the future of global health. Lancet 2020; 395: 1579–1586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ainsworth J, Buchan I. Combining health data uses to ignite health system learning. Methods Inf Med 2015; 54: 479–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Deny S, Elwell-Sutton T, Keith J, et al. Harnessing data and technology for public health: five challenges. The Health Foundation 2019; 1–19. https://www.health.org.uk/publications/long-reads/harnessing-data-and-technology-for-public-health-five-challenges (2019, accessed 1 June 2020). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Collins B. Big data and health economics: strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats. Pharmacoeconomics 2016; 34(2): 101–106. doi: 10.1007/s40273-015-0306-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dolley S. Big data’s role in precision public health. Front Public Heal 2018; 6: 68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lupton D. M-health and health promotion: the digital cyborg and surveillance society. Soc Theory Heal 2012; 10: 229–244. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lupton D. Quantifying the body: monitoring and measuring health in the age of mHealth technologies. Crit Public Health 2013; 23: 393–403. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bucci S, Schwannauer M, Berry N. The digital revolution and its impact on mental health care. Psychol Psychother Theory, Res Pract 2019; 92: 277–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Were MC, Sinha C, Catalani C. A systematic approach to equity assessment for digital health interventions: case example of mobile personal health records. J Am Med Informatics Assoc 2019; 26: 884–890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bakken S, Marden S, Arteaga SS, et al. Behavioral interventions using consumer information technology as tools to advance health equity. Am J Public Health 2019; 109: S79–S85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Naslund JA, Aschbrenner KA. Digital technology for health promotion: opportunities to address excess mortality in persons living with severe mental disorders. Evid Based Ment Heal 2019; 22: 17–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Smith MJ, Axler R, Bean S, et al. Four equity considerations for the use of artificial intelligence in public health. Bull World Health Organ 2020; 98: 290–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Neuhauser L, Kreps GL. Rethinking communication in the E-health era. J Health Psychol 2003; 8: 7–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kreps GL. The relevance of health literacy to mHealth. Stud Health Technol Inform 2017; 240: 347–355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Malvey DM, Slovensky DJ. Global mHealth policy arena: status check and future directions. mHealth 2017; 3: 41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Strathdee SA, Nobles AL, Ayers JW. Harnessing digital data and data science to achieve 90–90–90 goals to end the HIV epidemic. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2019; 14: 481–485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Eysenbach G. Infodemiology and infoveillance: framework for an emerging set of public health informatics methods to analyze search, communication and publication behavior on the internet. J Med Internet Res 2009; 11: e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jackson DN, Trivedi N, Baur C. Re-prioritizing digital health and health literacy in healthy people 2030 to affect health equity. Health Commun 2021; 36: 1155–1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Waldman L, Stevens M. Sexual and reproductive health and rights and mHealth in policy and practice in South Africa. Reprod Health Matters 2015; 23: 93–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Norman CD. Social media and health promotion. Glob Health Promot 2012; 19: 3–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Alexander DE. Social media in disaster risk reduction and crisis management. Sci Eng Ethics 2014; 20: 717–733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Breen N, Berrigan D, Jackson JS, et al. Translational health disparities research in a data-rich world. Heal Equity 2019; 3: 588–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Murray E. Web-based interventions for behavior change and self-management: potential, pitfalls, and progress. Med 20 2012; 1: e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Brewer LC, Fortuna KL, Jones C, et al. Back to the future: achieving health equity through health informatics and digital health. JMIR mHealth UHealth 2020; 8: e14512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rodriguez JA, Clark CR, Bates DW. Digital health equity as a necessity in the 21st century cures act era. JAMA 2020; 323: 2381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.McAuley A. Digital health interventions: widening access or widening inequalities? Public Health 2014; 128: 1118–1120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gibbons MC, Fleisher L, Slamon RE, et al. Exploring the potential of web 2.0 to address health disparities. J Health Commun 2011; 16: 77–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.McDaniel AM, Schutte DL, Keller LO. Consumer health informatics: from genomics to population health. Nurs Outlook 2008; 56: 216–223.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Laakso E-L, Armstrong K, Usher W. Cyber-management of people with chronic disease: a potential solution to eHealth challenges. Health Educ J 2012; 71: 483–490. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Norman CD, Yip AL. Ehealth promotion and social innovation with youth: using social and visual media to engage diverse communities. Stud Health Technol Inform 2012; 172: 54–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Brall C, Schröder-Bäck P, Maeckelberghe E. Ethical aspects of digital health from a justice point of view. Eur J Public Health 2019; 29: 18–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Stellefson M, Paige SR, Chaney BH, et al. Evolving role of social media in health promotion: updated responsibilities for health education specialists. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020; 17: 1153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Levin-Zamir D, Bertschi I. Media health literacy, eHealth literacy, and the role of the social environment in context. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2018; 15: 1643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Betsch C, Brewer NT, Brocard P, et al. Opportunities and challenges of Web 2.0 for vaccination decisions. Vaccine 2012; 30: 3727–3733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kukafka R. Public health informatics: the nature of the field and its relevance to health promotion practice. Health Promot Pract 2005; 6: 23–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Freudenberg N. Assessing the public health impact of the mHealth app business. Am J Public Health 2017; 107: 1694–1696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Veinot TC, Mitchell H, Ancker JS. Good intentions are not enough: how informatics interventions can worsen inequality. J Am Med Informatics Assoc 2018; 25: 1080–1088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zhang X, Pérez-Stable EJ, Bourne PE, et al. Big data science: opportunities and challenges to address minority health and health disparities in the 21st century. Ethn Dis 2017; 27: 95–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Grande SW, Sherman LD. Too important to ignore: leveraging digital technology to improve chronic illness management among black men. J Med Internet Res 2018; 20: e182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.EXPH, Report on Assessing the impact of digital transformation of health services, expert panel on effective ways of investing in health (EXPH). Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 76.de los Reyes G. Institutional entrepreneurship for digital public health promotion: challenges and opportunities. Heal Educ Behav 2019; 46: 30S–36S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Michie S, Yardley L, West R, et al. Developing and evaluating digital interventions to promote behavior change in health and health care: recommendations resulting from an international workshop. J Med Internet Res 2017; 19: e232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Fountain JE. Digital government and public health. Prev Chronic Dis 2004; 1: 1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Schootman M, Nelson EJ, Werner K, et al. Emerging technologies to measure neighborhood conditions in public health: implications for interventions and next steps. Int J Health Geogr 2016; 15: 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Moorhead SA, Hazlett DE, Harrison L, et al. A new dimension of health care: systematic review of the uses, benefits, and limitations of social Media for health communication. J Med Internet Res 2013; 15: e85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ricciardi W, Pita Barros P, Bourek A, et al. How to govern the digital transformation of health services. Eur J Public Health 2019; 29: 7–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Burke-Garcia A, Scally G. Trending now: future directions in digital media for the public health sector. J Public Health (Bangkok) 2014; 36: 527–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sarkar U, Le GM, Lyles CR, et al. Using social Media to target cancer prevention in young adults: viewpoint. J Med Internet Res 2018; 20: e203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hadley TD, Pettit RW, Malik T, et al. Artificial intelligence in global health —A framework and strategy for adoption and sustainability. Int J Matern Child Heal AIDS 2020; 9: 121–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Rumsfeld JS, Joynt KE, Maddox TM. Big data analytics to improve cardiovascular care: promise and challenges. Nat Rev Cardiol 2016; 13: 350–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Evans WD, Thomas CN, Favatas D, et al. Digital segmentation of priority populations in public health. Heal Educ Behav 2019; 46: 81S–89S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Grady A, Yoong S, Sutherland R, et al. Improving the public health impact of eHealth and mHealth interventions. Aust N Z J Public Health 2018; 42: 118–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Erwin PC, Brownson RC. Macro trends and the future of public health practice. Annu Rev Public Health 2017; 38: 393–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Olson SH, Benedum CM, Mekaru SR, et al. Drivers of emerging infectious disease events as a framework for digital detection. Emerg Infect Dis 2015; 21: 1285–1292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Heldman AB, Schindelar J, Weaver JB. Social media engagement and public health communication: implications for public health organizations being truly “social”. Public Health Rev 2013; 35: 13. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Stoové MA, Pedrana AE. Making the most of a brave new world: opportunities and considerations for using twitter as a public health monitoring tool. Prev Med (Baltim) 2014; 63: 109–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Fung IC-H, Tse ZTH, Fu K-W. The use of social media in public health surveillance. West Pacific Surveill Response J 2015; 6: 3–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Korda H, Itani Z. Harnessing social Media for health promotion and behavior change. Health Promot Pract 2013; 14: 15–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Morales J, Inupakutika D, Kaghyan S, et al. Technology-based health promotion: current state and perspectives in emerging gig economy. Biocybern Biomed Eng 2019; 39: 825–842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Heldman MPH AB, Schindelar MPH J, Weaver IIIet al. et al. Social media engagement and public health communication: implications for public health organizations being truly “social”. Public Health Rev 2013; 35: 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Savel TG, Foldy S. The role of public health informatics in enhancing public health surveillance. MMWR Surveill Summ 2012; 61: 20–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.UNICEF Health Section Implementation Research and Delivery Science Unit and the Office of Innovation Global Innovation Centre. UNICEF’s approach to digital health. New York, https://www.unicef.org/innovation/reports/unicefs-approach-digital-health (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 98.Lang T. Advancing global health research through digital technology and sharing data. Science 2011; 331: 714–717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kirkwood J, Jarris PE. Aligning health informatics across the public health enterprise. J Public Heal Manag Pract 2012; 18: 288–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Chismar W, Horan TA, Hesse BW, et al. Health cyberinfrastructure for collaborative use-inspired research and practice. Am J Prev Med 2011; 40: S108–S114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Carney TJ, Kong AY. Leveraging health informatics to foster a smart systems response to health disparities and health equity challenges. J Biomed Inform 2017; 68: 184–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Uscher-Pines L, Fischer S, Chari R. The promise of direct-to-consumer telehealth for disaster response and recovery. Prehosp Disaster Med 2016; 31: 454–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Lu Z. Information technology in pharmacovigilance: benefits, challenges, and future directions from industry perspectives. Drug Healthc Patient Saf 2009; 1: 35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Brownstein JS, Freifeld CC, Madoff LC. Digital disease detection--harnessing the web for public health surveillance. N Engl J Med 2009; 360: 2153–5, 2157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Abroms LC. Public health in the era of social Media. Am J Public Health 2019; 109: S130–S131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Jane M, Hagger M, Foster J, et al. Social media for health promotion and weight management: a critical debate. BMC Public Health 2018; 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Vance K, Howe W, Dellavalle RP. Social internet sites as a source of public health information. Dermatol Clin 2009; 27: 133–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Hayes JF, Maughan DL, Grant-Peterkin H. Interconnected or disconnected? Promotion of mental health and prevention of mental disorder in the digital age. Br J Psychiatry 2016; 208: 205–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Merchant RM, Lurie N. Social Media and emergency preparedness in response to novel coronavirus. JAMA 2020; 323: 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Cawcutt KA, Marcelin JR, Silver JK. Using social media to disseminate research in infection prevention, hospital epidemiology, and antimicrobial stewardship. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2019; 40: 1262–1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]