Introduction

SARS-CoV2 infection presents commonly with the respiratory manifestations however; neurological manifestations have also been reported. The neurological manifestations of this virus range from headache, dizziness, anosmia to more severe complications such as encephalopathy, cerebrovascular stroke, injury to the musculoskeletal system as well as impaired consciousness [1]. Headache has been announced as the most common complaint of the neurological symptoms associated with SARS-CoV2 infection [2]. It has been reported in a case-series study that from fifty-six patients infected with SARS-CoV2, headache associated with intracranial hypertension was the most common findings among them.

This case was presented to overview idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH) as a rare neurological presentation of SARS-CoV2 infection that may be un/misdiagnosed and to increase the suspicion of clinicians for early diagnosis of COVID-19.

Case report

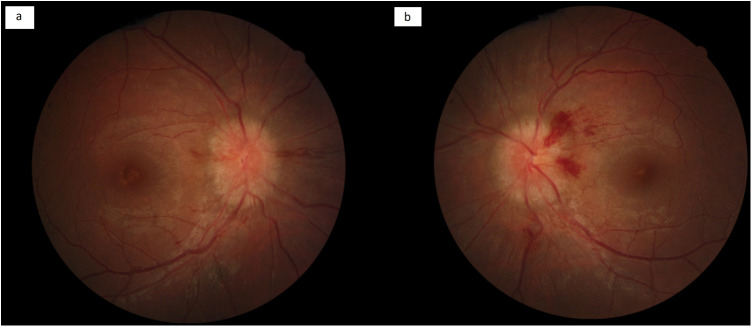

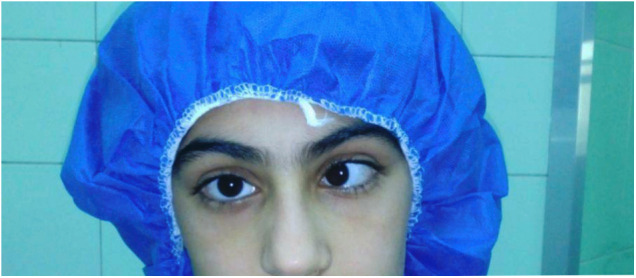

A 13-year-old girl pre-pubertal with a body mass index (BMI) of 23 with no past medical history was admitted to the emergency room with the symptoms including anorexia, nausea, vomiting, fever, headache, flank pain and diplopia. Nausea, vomiting, and a mild flank pain started over the past ten days before admission as the initial symptoms. Five days after the presentation of initial symptoms, flank pain got worse and mild diplopia were developed. The patient was referred to a neurologist and brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) as well as computed tomography (CT-scan) of the orbit was requested. The results were normal for both brain MRI and CT of the orbit. Acetazolamide was prescribed with the diagnosis of increased intracranial pressure. However, her diplopia and strabismus, especially with a severe esotropia of the left eye (Fig. 1 ), worsened day by day with an unbearable pain in the flank area and therefore has been visited by an ophthalmologist. On physical examination, the patient had bilateral abduction limitation of eyes (sixth nerve palsy). Examination of the visual field also revealed enlargement of the both eyes’ blind spot. Fundoscopy of the patient demonstrated a bilateral papilledema (Fig. 2 ). Magnetic resonance venography (MRV) was normal and did not show any signs of impaired blood flow or venous thrombosis. Finally, the patient was referred to a neurologist again with the diagnosis of IIH and LP procedure was done for the patient. LP showed a cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) opening pressure of 40 cm H2o. During the patient's hospitalization, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis of the nasopharyngeal swab was done for the patient which was positive for SARS-CoV2.

Figure 1.

Severe esotropia of the left eye.

Figure 2.

Right (a) and left (b) eyes fundus photos on admission.

Chest computed tomography (CT) did not show any involvement of the lungs and was negative for COVID-19 patterns of involvement. CSF analysis showed elevated WBC (320) and RBC (320) and negative for microbial culture. CSF glucose and protein levels were 65 mg/dL and 34 mg/dL respectively. Serum IgG levels for COVID-19 were elevated (8.5 mg/dL). The patient and her family have had COVID-19 manifestations of anosmia, ageusia, myalgia, headache, and positive nasopharyngeal swab PCR of COVID-19 20 days before developing IIH.

LDH, CRP and ferritin levels were normal. The patient hasn’t received any special treatments for COVID-19 due to the absence of inflammatory state. The patient has been hospitalized for one night after her LP and was prescribed vitamin D and vitamin C with acetazolamide. After the LP procedure, esotropia and diplopia relieved progressively over the next two weeks and almost resolved one month after. In our case, IIH was a post-COVID-19 neurological manifestation.

Discussion

IIH is defined as an increase in intracranial pressure (ICP) without hydrocephalus, any mass lesions to be present, and a normal composition of CSF.[3] Headache, nausea, vomiting, intracranial noises, diplopia as the result of paralysis of the sixth nerve, papilledema and temporary visual obstructions are the common signs and symptoms of this syndrome [4]. The most common sign and symptom of IIH are papilledema and headache respectively [5]. In accordance with the present case, a latter case report of a 35-year old female developing benign intracranial hypertension in the course of COVID-19 has been published. The patient had the complaints of fever, dyspnea and headache on admission and became disoriented soon after. The analysis of the CSF of the patient was normal apart from an elevation in the CSF pressure (40 cm H2O). Brain MRI of the patient also demonstrated enlargement of subarachnoid space around the optic nerves, vertical tortuosity of the optic nerve as well as superior compression of the hypophysis [6]. In addition to this latter case report, a case series of fifty-six SARS-CoV2 infected patients with different neurological symptoms showed a negative CSF analysis of SARS-CoV2 for all patients. Thirteen patients of these 65, suffered from intensive consistent headaches and 84 percent of these patient's headaches were not associated with meningitis or encephalitis the same as our present case [7].

Several etiologies have been defined for IIH such as venous sinus thrombosis, sepsis, obesity, autoimmune diseases, deficiency or excess of some vitamins, and toxicity of some drugs or substances such as contraceptives, and bacterial or viral infections [7].

It has been suggested that in terms of SARS-CoV2 infection, an increase in von willebrand factor, impaired endothelial function, and the systemic inflammatory state, will make a hypercoagulable state that facilitates clot formation and subsequently will result in obstruction of CSF outflow. Thus, it can be assumed as one of the possible mechanisms of SARS-CoV2 which causes IIH in infected patients [7]. Our present case had a normal brain MRI and MRV similar to the reported cases in the recent case series. Although no clot formations have been detected in imagings, IIH in association to SARS-CoV2 could be attributed to preparing an inflammatory state, high viscosity and a hypercoagulable state. Small vessel involvements have also been reported in association with SARS-CoV2 infection [8]. Capillary endothelial cells of the central nervous system express ACE2 receptor of the virus which could give the virus its neuroinvasive nature causing various neurological manifestations such as encephalitis, meningitis, intracerebral hemorrhage, headache, ischemic stroke [2] or IIH in the absence of any underlying encephalitis or meningitis as reported in our case.

Funding

None.

Disclosure of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

References

- 1.Whittaker A, Anson M, Harky A. Neurological Manifestations of COVID-19: A systematic review and current update. Acta Neurol Scand. 2020 Jul;142(1):14–22. doi: 10.1111/ane.13266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Niazkar H.R., Zibaee B, Nasimi A, Bahri N. The neurological manifestations of COVID-19: a review article. Neurol Sci. 2020;41(7):1667–1671. doi: 10.1007/s10072-020-04486-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sylaja P.N., Ahsan Moosa N.V., Radhakrishnan K., Sankara Sarma P., Pradeep Kumar S. Differential diagnosis of patients with intracranial sinus venous thrombosis related isolated intracranial hypertension from those with idiopathic intracranial hypertension. J Neurol Sci. 2003;215:9–12. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(03)00182-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keskin A.O., İdiman F., Kaya D., Bircan B. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension: etiological factors, clinical features, and prognosis. Noropsikiyatri Ars. 2020;57:23–26. doi: 10.5152/npa.2017.12558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bruce B.B., Biousse V., Newman N.J. Update on idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Am J Ophthalmol [Internet] 2011;152:163–169. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2011.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Noro F., Cardoso F., de M., Marchiori E. COVID-19 and benign intracranial hypertension: a case report. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2020;53:1. doi: 10.1590/0037-8682-0325-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Silva M.T.T., Lima M.A., Torezani G., Soares C.N., Dantas C., Brandão C.O., et al. Isolated intracranial hypertension associated with COVID-19. Cephalalgia. 2020;40:1452–1458. doi: 10.1177/0333102420965963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dolhnikoff M., Duarte-Neto A.N., de Almeida Monteiro R.A., da Silva L.F.F., de Oliveira E.P., Saldiva P.H.N., et al. Pathological evidence of pulmonary thrombotic phenomena in severe COVID-19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18:1517–1519. doi: 10.1111/jth.14844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]