Highlights

-

•

Among Asian American study participants, study results show unsafe practices of gun storage.

-

•

More than one third of gun owners reported having carried a gun more frequently when they were outside their home since the COVID-19 pandemic.

-

•

Racial discrimination and cultural racism are associated with gun purchase while anticipatory racism-related stress is associated with intent to purchase a gun.

-

•

Data suggest that racism and its link to increased firearm ownership and carrying may put Asian Americans at elevated risk of firearm injury.

Keywords: Firearm violence, Injury prevention, Safety, Firearm-related behavior, Intention, Coronavirus

Abstract

Firearm-related injury is a major public health concern in the U.S. Experience of racism and discrimination can increase the risk of minority group members engaging in or being victims of firearm-related violence. Given the increased racism endured by Asian Americans during the COVID-19 pandemic, it is imperative to understand firearm-related behaviors in this population. The purpose of this study was to examine how Asian Americans’ racism and discrimination experiences were related to firearm-related behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic. Cross-sectional data were collected between December 2020 and January 2021 from a national sample of 916 Asian Americans. Measures included demographics, firearm-related risks, and three measures of racism/discrimination experiences since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. Among individuals who purchased a gun since the start of the pandemic, 54.6% were first-time gun owners. Among household gun owners, 42.8% stored loaded guns and 47.1% stored guns unlocked. More than 38% of individual gun owners have carried a gun more frequently since the pandemic. After controlling for family firearm ownership and demographics, regression analyses showed that Asian Americans who experienced racial discrimination were more likely to purchase a gun and ammunition and intend to purchase more ammunition during the COVID-19 pandemic. AAs who perceived more cultural racism were more likely to purchase a gun. Individuals who reported higher anticipatory racism-related stress reported greater intent to purchase guns. Our findings suggest an urgent need to investigate further the compounded effects of racism, the COVID-19 pandemic, and firearm-related behaviors in this population.

1. Introduction

Firearm-related injuries are a serious public health problem; gun-related deaths (intentional or violence-related, unintentional, and of undetermined intent) totaled 39,707 in 2019 in the United States (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020). During the COVID-19 pandemic, the U.S. experienced a surge in firearm sales that represented a potentially increased risk of adverse outcomes. In the first three months (March to May) of the pandemic in 2020, over 2.1 million firearms were purchased, with an estimate of 766 additional firearm-related injuries compared to the same period in 2019 (Schleimer et al., 2020). Access to a firearm and firearm carriage place individuals at greater risk of involvement in fighting, interpersonal violence, and violent injuries resulting in death or requiring hospitalization (Branas et al., 2009, Carter et al., 2013, Lowry et al., 1998). In addition, unsafe firearm storage (i.e., loaded and unlocked) in homes with recently purchased firearms can increase youth risk of unintentional and intentional injury and death (Monuteaux et al., 2019). The progression of the COVID-19 pandemic coupled with economic struggles, social isolation, and psychological fallout have intensified violence-related injuries and mortality (Sharma and Borah, 2020).

Asian Americans (who comprise 6.6% of the U.S. population) have faced a tide of racial discrimination, anti-Asian hate, and targeted violence during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism (2021) reported that anti-Asian hate crime in 16 of America’s largest cities increased 145% during the pandemic. This was due in part by misinformation regarding the origins of the virus, and unsubstantiated accusations by political leaders and others that the Chinese government intentionally released the virus as a bioweapon. The fact that national political figures and leaders referred to the COVID-19 crisis as the Chinese flu may have reinforced racial discrimination (Devakumar et al., 2020) and contributed to blaming Asian Americans for the pandemic as an ongoing effort to instill fear and deflect responsibility to help staunch the pandemic in the U.S. (Lee and Johnstone, 2020). Racism experiences like the kind of anti-Asian hate incidents resulting from the pandemic can trigger psychological distress (Brondolo et al., 2005, Krieger, 1999) and feeling the need to protect oneself and family with a gun purchase. This in turn can increase risks for being victims of or engaging in firearm violence (Bryant, 2011, Caldwell et al., 2002, Sellers et al., 2003).

Recent reports noted a sharp increase in gun sales nationwide in early March of 2020 (Lee and Charbria, 2020). Gun sales to Asian Americans are estimated to have increased by 43% in the first half of 2020 (Liu and Hatzipanagos, 2020), possibly in response to the increased in anti-Asian rhetoric and Anti-Asian violence amid the COVID-19 outbreak (Asian Pacific Policy and Planning Council, 2020, Chung and Li, 2020, Devakumar et al., 2020). The decision to obtain a firearm is often motivated by past victimization and fears of future victimization (Chung and Li, 2020, Devakumar et al., 2020), however a direct causal link between discrimination and gun ownership amongst Asian Americans has not been established.

The history of anti-Asian racism and the current state of the Asian American experience in the U.S. suggests an urgent need for research in this population to study the harmful effects of the discrimination and racism experiences. Given the rapid increase in firearm purchase during the COVID-19 pandemic, it is important to understand how discrimination may be related to firearm carrying and the risk for firearm-related injury among Asian Americans.

To our knowledge, no researchers have examined the effects of racism on firearm-related behaviors among Asian Americans during the COVID-19 pandemic. In current study, we examine Asian Americans’ racism experiences and their firearm-related behaviors (purchase, carrying, and storage) well as purchasing intentions during the COVID-19 pandemic. Research questions examined in the current study include: 1. What are the characteristics of firearm-related behaviors and intentions for firearm and ammunition purchase among Asian Americans during the pandemic? 2. Do racism experiences predict firearm-related behaviors?

2. Methods

2.1. Study participants and data collection

A cross-sectional online survey was administered from December 2020 to January 2021 to a representative sample of U.S. adults using a random sample maintained by Dynata (https://www.dynata.com). The Dynata Simplify panel comprises over 2.5 million U.S. residents. To ensure reliability and accuracy of data, the Dynata team deployed a rigorous verification process which included digital fingerprinting, spot-checking via third-party verification to prove identity, and removing panel members that provide illogical responses or do not spend sufficient time answering survey questions.

Eligible participants were individuals 18 years of age or older who could read English and self-identified as Asian Americans who had access to the internet via computer or smartphone to complete online surveys. A total of 1164 eligible participants were invited, and 940 responded to the survey, representing a response rate of 80.8%. The study protocol and procedures were reviewed by the first author’s Institutional Review Board (Protocol #UHSRC-FY18-19-83).

2.2. Measures

Racism experiences consisted of three dimensions: 1) direct experiences of racial discrimination, 2) perceptions of cultural racism, and 3) responses to racism (anticipatory racism-related stress). Direct experience of racial discrimination was measured using 13 items: Nine items were adapted from the Racial-Ethnic Discrimination Scale (Sladek et al, 2020) and four items from Williams’ (2008) Major Experiences of Discrimination (MED) (Williams et al., 2008). The Racial-Ethnic Discrimination Scale measured racial discrimination and unfair treatment in different settings (e.g., restaurant, workplace, etc.). Cultural racism was measured by four items adapted from the Index of Race-Related Stress (IRRS)-Brief Version (Utsey et al., 2013). These items assessed perceptions of cultural racism; the wording referring to “African Americans” was replaced with “Asian Americans.” Anticipatory racism-related stress was measured by four items adapted from Utsey’s Prolonged Activation and Anticipatory Race-Related Stress Scale (PARS) (Utsey, 1999). The items assessed participants’ psychological and behavioral reactions to an impending race-related event (Measurement items can be found in Appendix A).

Firearm-related behaviors and intention. We used the following questions with yes/no options to measure firearm-related behaviors and intention: 1) self or household ownership of a gun (2 questions), 2) purchase of a gun and purchase of more ammunition since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic (2 questions), 3) intention to purchase a gun and intention to purchase more ammunition than usual since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic (2 questions), and 4) for gun owners, we asked two additional questions related to whether any of the guns were stored loaded or unlocked. (Appendix A).

Control Variables. Researchers have reported associations between household demographics and firearm ownership (Hamilton et al., 2018) and parents' demographics in households with teens and firearm purchasing (Sokol et al., 2021). Therefore, we controlled for age, sex, household income, education, nativity (born in the United States), ethnicity, and household firearm ownership in our analyses. Household firearm ownership was assessed by two questions: “Do you personally own a gun?” and “Does anyone else you live with own a gun?” Responding yes to either question was indicative of household firearm ownership.

In addition, racism experiences and firearm access may be more similar for participants residing in the same geographic regions (e.g., West, East, South, or Midwest). Based on the zip code information collected from participants, we controlled for the geographic region and considered the nested structure of the data by using the multilevel models (MLMs) approach for the primary analyses.

2.3. Analyses

Descriptive statistics (frequencies, percentages, and means) were used to describe participants’ firearm ownership and behavior. To explore the geographical variation of the data, we used a geographic information system (GIS) ArcGIS Pro (ESRI, 2021) to geocode participants and present locations on a national map. Next, we conducted an overlay analysis to examine the association between racial and ethnic makeup and the racism experienced by participants from nearby geographic areas. To examine the association between racism experiences from respondents and their surrounding race and ethnicity environment, we created a Diversity Index (DI) derived from 2020 census data (U.S. Census Bureau, 2020) with the equation DI = 1 – (H2 + W2 + B2 + AIAN2 + Asian2 + NHPI2 + SOR2 + Multi2) (Blau, 1977, Meyer and McIntosh, 1992), where H, W, B, AIAN, Asian, NHPI, SOR, Multi represents the proportion of the population in a state who are Hispanic or Latino, White alone, American Indian and Alaska Native alone, Asian alone, Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islanders alone, some other race alone, and two or more races respectively. The racial and ethnic DI in each state is a value between 0% and 100%, where a higher number indicates greater racial and ethnic diversity.

To address the main research questions, we conducted a multilevel logistic regression analysis to examine racism experiences as predictors of firearm behavior outcomes (i.e., intention to purchase and actual purchase of gun and ammunition). The main purpose of the two-level MLMs was to account for the nonindependence of firearm behavior outcomes within regions by allowing the level-1 (individual level) intercepts to vary across level-2 (regional level). We estimated MLMs with Stata/SE 17.0 (StataCorp L.P., College Station, TX). All MLMs controlled for age, sex, income, education, U.S. birth, ethnicity, and household firearm ownership. We also ran a separate model using only the sub-sample of gun owners to examine the link between racism experiences and gun carrying during the COVID-19 pandemic. This model included racism predictors and all the control variables listed above.

3. Results

3.1. Demographics of study participants

Of the 940 survey respondents, 916 had complete data. The a mean age of the analytic sample was 41.51 years (SD = 17.84; range of 18–86 years). Among respondents in this national sample, the majority of participants were women (60.8%) and were born in the U.S. The ethnic breakdown and additional sociodemographic characteristics of participants appear in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic and firearm ownership among Asian Americans.

| Categorical Variables | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 359 | 39.2 |

| Female | 557 | 60.8 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| Indian | 51 | 5.6 |

| Chinese | 291 | 31.8 |

| Filipino | 139 | 15.2 |

| Japanese | 205 | 22.4 |

| Korean | 110 | 12.0 |

| Vietnamese | 110 | 12.0 |

| Other Asian | 10 | 1.1 |

| Education | ||

| High school or less | 103 | 11.2 |

| Some college | 176 | 19.2 |

| College graduate or higher | 637 | 69.5 |

| Income | ||

| $0 to $34,999 | 214 | 23.4 |

| $35,000 to $49,999 | 103 | 11.2 |

| $50,000 to $74,999 | 167 | 18.2 |

| $75,000 to $99,999 | 158 | 17.2 |

| $100,000 or more | 274 | 29.9 |

| Nativity | ||

| Yes | 565 | 61.7 |

| No | 351 | 38.3 |

| Firearm-related Variables | ||

| Intention to Purchase Gun | ||

| Yes | 103 | 11.2 |

| No | 773 | 84.4 |

| Purchased Gun | ||

| Yes | 55 | 6.0 |

| No | 821 | 89.6 |

| Intention to Purchase Ammunition | ||

| Yes | 69 | 7.5 |

| No | 806 | 88.0 |

| Purchased Ammunition | ||

| Yes | 54 | 5.9 |

| No | 822 | 89.7 |

| Household Firearm Ownership | ||

| Yes | 159 | 17.4 |

| No | 718 | 78.4 |

| Continuous Racism Scales | M | SD |

| Racial Discriminationa | 1.45 | 0.90 |

| Cultural Racisma | 2.25 | 1.33 |

| Anticipatory Racism-related Stressa | 2.05 | 1.41 |

Scores are based on a scale of 1 = less than once a year, 2 = a few times a year, 3 = at least once a month, 4 a few times a month, 5 = at least once a week, and 6 = almost every day.

3.1.1. Geographic locations: study participants

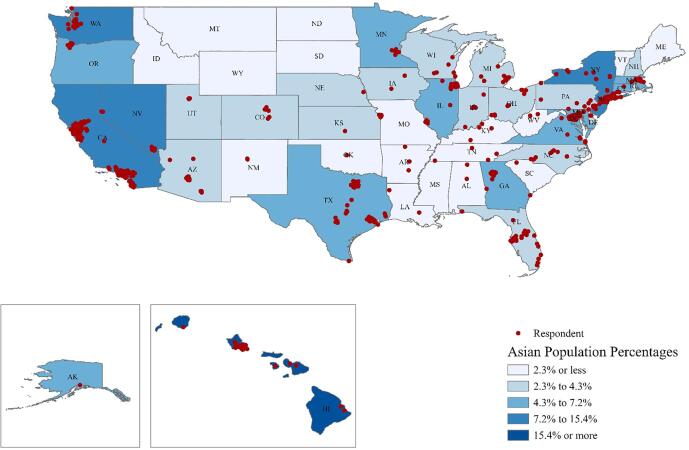

Fig. 1 shows the Asian American population percentage in each state, classified into five colors, with light blue indicating a low percentage of Asian Americans (less than 2.3%) and dark blue representing a high percentage of Asian Americans (greater than 15.4%). The figure is overlaid with the Asian American respondent's location (using zip code collected in the survey) symbolized by the red dot. The map identifies regional clusters (e.g., states like WA-OR-CA-NV; H.I.; TX; MN-IL; NY-NJ-VA-DC; and G.A.) with higher than average Asian American populations. These geographic clusters were used as a base layer to compare with locations of national samples who identified themselves as Asian American. The large number of Asian American respondents residing within these clusters or vicinities suggests our sample was fairly representative of the U.S. Asian population.

Fig. 1.

Geographic locations of study participants and Asian population by state.

3.2. Geographic locations: Diversity Index (DI) and racism

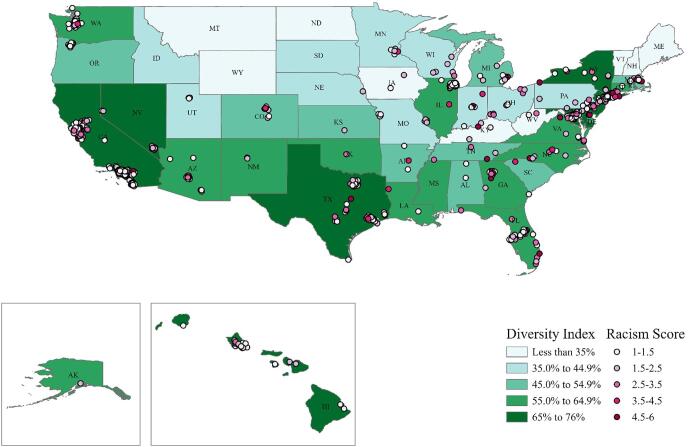

Using geographic information, we employed ArcGIS to geocode each respondent’s latitude and longitude. Among 916 participants, only 43 (4.6%) respondents could not be geocoded due to missing geographic information. Fig. 2 illustrates a heat map showing the state racial and ethnic DI symbolized into five groups, ranging from states with a DI less than 35% in light green, to the states with a DI greater than 65% in dark green. We overlaid the DI heat map with each respondent's location symbolized by the racism score, with light red indicating less racism experienced and dark red showing more racism experienced.

Fig. 2.

Heat map of diversity index by state and participant’s racism score.

3.3. Firearm-related behaviors: purchase, storage and carrying

Examining gun and ammunition purchases during the COVID-19 pandemic, 6% (n = 55) indicated that they or someone in their home purchased a gun, and 5.9% (n = 54) purchased more ammunition than usual. Notably, 54.6% (n = 30) of those who purchased a gun said it was the first gun that someone in their household had purchased. In terms of intentions to purchase, 11.2% of our sample (n = 103) intended to purchase a gun and 7.5% (n = 69) intended to purchase more ammunition since the start of the pandemic.

Among participants within households not currently owning firearms, 7.0% (n = 50) intended to purchase a gun since the start of the pandemic. Among those within households currently owning a firearm, 29.1% (n = 46) intended to purchase more ammunition since the start of the pandemic.

The additional analysis examined safety measures among individuals who reported household gun ownership (17.4%; n = 159). The results showed that while 87.9% reported that they knew where the gun(s) were stored, 42.8% reported the gun(s) on their property was stored loaded, and 47.1% said at least one firearm was stored unlocked. Finally, 38.2% (n = 39) of individual gun owners indicated that they had carried a gun more frequently since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic and the top reason was for protection (Table 2). Furthermore, more than 1/3 of gun owners (38.5%, n = 15) reported that they carried a gun over half of the time (greater than 45 days) in the last three months. Additional descriptive statistics on firearm carrying and storage can be found in Table 2.

Table 2.

Firearm Storage and Carriage among Asian American Gun Owners (n = 157).

| Yes | No | Not Sure |

Valid Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | N | |

| Do you know where the gun(s) on your property are stored? | 138 | 87.9 | 19 | 12.1 | N/A | N/A | 157 |

| Are any of the guns on your property stored loaded? | 59 | 42.8 | 73 | 52.9 | 6 | 4.3 | 138 |

| Are any of the guns on your property stored unlocked? | 65 | 47.1 | 68 | 49.3 | 5 | 3.6 | 138 |

| Since the COVID-19 pandemic, have you carried a gun with you more frequently when you were outside your home? | 39 | 38.2 | 63 | 61.8 | N/A | N/A | 102* |

| Reasons for carrying a gun more often** | |||||||

| For protection | 27 | 69.3 | 39 | ||||

| Getting back at someone | 8 | 20.5 | 39 | ||||

| Threatening for getting something from someone | 7 | 18.0 | 39 | ||||

| For fun or excitement | 7 | 18.0 | 39 | ||||

| Gaining respect or status | 4 | 10.3 | 39 | ||||

| For a right | 1 | 2.6 | 39 | ||||

*Only included individuals who indicated personally owning a gun.

**Respondents can choose more than one reason(s).

3.4. Racism and firearm purchase, intention and carrying

Table 3 shows MLM logistic regression results for racism variables and covariates on four outcomes since the COVID-19 pandemic started in Mar. 2020: 1) purchased a firearm, 2) intention to purchase a firearm, 3) purchased more ammunition than usual, and 4) intention to purchase more ammunition than usual. Participants who experienced more racial discrimination were more likely to report that they or someone in their home purchased a gun (OR = 1.79, CI = 1.25, 2.56), intended to purchase a gun (OR = 1.59; CI = 1.15, 2.19), and purchased more ammunition than usual (OR = 1.52; CI = 1.05, 2.21) compared to those who experienced less discrimination. Racial discrimination was not associated with intention to purchase more ammunition. Participants who perceived more cultural racism against Asians since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic were more likely to purchase a gun (OR = 1.69; CI = 1.16, 2.45) than those who experiences less cultural racism. Cultural racism was not associated with purchasing more ammunition or intention to purchase a gun or ammunition. Participants who reported more racism-related stress were more likely to express an intention to purchase a gun (OR = 1.35; CI = 1.03, 1.76), but this was no associated with purchasing a gun or more ammunition, or intention to purchase ammunition.

Table 3.

Multilevel logistic regression results of racism on firearm purchase and intention to purchase among Asian Americans.

| Intention to Purchase Gun Since COVID (n = 869) |

Purchased Gun Since COVID (n = 869) |

Intention to Purchase Ammunition Since COVID (n = 868) |

Purchased Ammunition Since COVID (n = 869) |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% confidence interval (C.I.) | OR | 95% confidence interval (C.I.) | OR | 95%confidence interval (C.I.) | OR | 95% confidence interval (C.I.) | |||||

| Racial Discrimination | 1.16 | 0.89 | 1.53 | 1.79 | 1.25 | 2.56 | 1.59 | 1.15 | 2.19 | 1.52 | 1.05 | 2.21 |

| Cultural Racism | 0.95 | 0.72 | 1.25 | 1.69 | 1.16 | 2.45 | 1.26 | 0.87 | 1.84 | 1.44 | 0.93 | 2.22 |

| Anticipatory Racism-related Stress | 1.35 | 1.03 | 1.76 | 0.65 | 0.44 | 0.96 | 1.09 | 0.75 | 1.60 | 0.99 | 0.64 | 1.52 |

| Household firearm ownership** | 6.52 | 3.98 | 10.66 | 5.01 | 2.53 | 9.93 | 18.97 | 9.38 | 38.37 | 29.79 | 12.90 | 68.79 |

| Age | 0.99 | 0.97 | 1.00 | 0.97 | 0.94 | 0.99 | 0.96 | 0.93 | 0.99 | 0.97 | 0.94 | 1.00 |

| Male | 1.58 | 0.97 | 2.57 | 2.19 | 1.13 | 4.27 | 1.43 | 0.72 | 2.84 | 1.68 | 0.77 | 3.66 |

| Income | ||||||||||||

| $35,000 to $49,999 | 4.23 | 1.75 | 10.22 | 1.75 | 0.56 | 5.53 | 1.22 | 0.38 | 3.85 | 1.47 | 0.41 | 5.33 |

| $50,000 to $74,999 | 2.54 | 1.10 | 5.87 | 1.16 | 0.39 | 3.44 | 1.73 | 0.65 | 4.60 | 1.17 | 0.37 | 3.67 |

| $75,000 to $99,999 | 1.90 | 0.80 | 4.52 | 0.90 | 0.28 | 2.91 | 0.71 | 0.24 | 2.10 | 0.37 | 0.10 | 1.42 |

| $100,000 or more | 1.95 | 0.87 | 4.36 | 1.79 | 0.66 | 4.86 | 0.90 | 0.33 | 2.42 | 1.23 | 0.42 | 3.64 |

| Education | ||||||||||||

| Some college | 2.07 | 0.76 | 5.68 | 0.73 | 0.21 | 2.56 | 0.99 | 0.32 | 3.04 | 0.38 | 0.11 | 1.31 |

| College graduate or above | 2.60 | 1.02 | 6.58 | 2.51 | 0.85 | 7.37 | 1.76 | 0.64 | 4.84 | 0.78 | 0.27 | 2.19 |

| Nativity | 0.87 | 0.52 | 1.45 | 1.26 | 0.61 | 2.62 | 0.91 | 0.43 | 1.92 | 0.81 | 0.36 | 1.85 |

| Ethnicity | ||||||||||||

| Chinese | 0.86 | 0.33 | 2.27 | 0.44 | 0.14 | 1.41 | 0.26 | 0.09 | 0.79 | 0.24 | 0.07 | 0.82 |

| Filipino | 0.80 | 0.27 | 2.41 | 0.80 | 0.22 | 2.88 | 0.37 | 0.11 | 1.25 | 0.22 | 0.05 | 0.88 |

| Japanese | 1.15 | 0.39 | 3.34 | 0.49 | 0.13 | 1.86 | 0.28 | 0.08 | 1.03 | 0.11 | 0.02 | 0.57 |

| Korean | 0.58 | 0.18 | 1.81 | 0.27 | 0.07 | 1.14 | 0.19 | 0.05 | 0.78 | 0.15 | 0.03 | 0.75 |

| Vietnamese | 0.96 | 0.32 | 2.91 | 0.57 | 0.15 | 2.17 | 0.37 | 0.10 | 1.34 | 0.42 | 0.11 | 1.65 |

| Other Asian | 2.30 | 0.40 | 13.29 | 0.86 | 0.08 | 9.38 | 2.93 | 0.47 | 18.28 | 0.99 | 0.12 | 8.05 |

*All models accounted for the nested effects within geographic regions (East, South, West, Midwest) as level-two variable in the multilevel logistic regression.

**For the outcome of purchase gun during the pandemic, we recoded household firearm ownership to include only those who reported owning a firearm prior to the onset of the pandemic, which enables to obtain a more accurate estimate for this outcome with the existing household gun ownership.

a Reference group for Gender--Female; Income-- Less than $35,000/year; Education-- High School or Less; Place of birth--Not Born in U.S.; Ethnicity-- Asian Indian.

Among gun owners who responded to the gun carriage question (n = 102), experiencing more direct racial discrimination was associated with a higher likelihood of carrying a gun more frequently since the COVID-19 pandemic began (OR = 3.09, CI = 1.32, 7.22).

4. Discussion

Limited research on firearm ownership, gun and ammunition purchase, and storage behaviors has focused on Asian Americans. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to explore the associations between racism and firearm-related behaviors and intention among Asian Americans. Our study delineates the characteristics of Asian Americans who purchased firearms during the pandemic and provides initial evidence of a link between racism and firearm ownership and ammunition purchase in this group. Given that prior research demonstrated that firearm purchase, unsafe storage and carriage can increase the risks of firearm injury (Branas et al., 2009, Carter et al., 2013, Lowry et al., 1998, Monuteaux et al., 2019), our results suggest that racism and its link to increased firearm and ammunition purchasing, and carrying may put Asian Americans at elevated risk of firearm injury.

Although a lower percentage of Asian Americans own guns compared to other ethnic groups (Carter et al., 2015), our findings suggest that the COVID-19 pandemic and the subsequent racism directed toward Asian Americans increased their risk for firearm injury through increased gun and ammunition purchase and unsafe storage. Over half of our study participants who purchased a gun since the pandemic were first-time gun owners (54.6%). This is higher than another firearm study in California in 2020 that indicated 4% of participants for the general population reported they had acquired a firearm in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, and 43.0% were first-time firearm owners (Kravitz-Wirtz et al., 2021). In terms of other firearm-related risks, almost half of owners in this study stored their guns unlocked and loaded, and over one-third reported that they carried a gun more frequently during the pandemic. This greater access and accessibility by others of a firearm raises concerns that the firearm could get into someone else’s hands and be used for self-harm. Unemployment; financial burden; feeling isolated, lonely, and depressed due to changes in social routine; and deaths/illnesses of loved ones due to the COVID-19 pandemic can exacerbate suicidal intent, and firearm purchases may contribute to a potential increase in firearm suicide (Sher, 2020).

Our findings provide initial evidence that direct experiences of racial discrimination and perceptions of cultural racism against Asian Americans predicted the purchase of a gun and more ammunition. Racism-related stress predicted the intention to purchase a gun. Several researchers have reported the leading reason for gun purchase was for the protection of self and family, and this reason has remained the same before (Pew Research Center, 2017) and during the COVID-19 pandemic (Schleimer et al., 2021). Our results provided additional information on how various types of racism among Asian Americans associated with firearm-related behaviors and intention since the beginning of the pandemic. In particular, Asian-Americans may be at increased risks for firearm injuries due to more gun purchases and carriage and less safe storage behavior since the COVID-19 pandemic.

In summary, our results indicated that increased experiences of discrimination among Asian-Americans increased the number of people who purchased a firearm for protection and exacerbated unsafe firearm-related behaviors (e.g., storing unlocked and loaded). Our findings suggest the need to develop and implement policies related to both reducing anti-Asian discrimination and promoting secure gun storage. This could also include promoting harm reduction behaviors for individuals who feel the need to carry for protection. The prevention efforts can be more effective if they both focus on individual firearm behaviors while also addressing the interpersonal and systemic racism that Asian-Americans (and other minority groups) experience.

Our results should be considered in light of several limitations. Our cross-sectional design limits causal attributions. In addition, it is possible that our finding of an association between racism and firearm-related behaviors can be confounded by unmeasured psychological and social attributes; however, the fact that we controlled for alternative explanations adds confidence that the association between variables of interest (racism and firearm outcomes) is not explained by spuriousness alone. Nevertheless, future research using longitudinal designs (e.g., cross-lagged models) would be an important step in establishing the temporal linkages between racism experiences and firearm-related behaviors. Secondly, the self-reported data raises concerns about social desirability in responses, especially the firearm-related behaviors, resulting in fewer reports of new purchases and unsafe storage. Yet, social desirability bias is less of a concern because our study used an anonymous online survey approach, which allows for greater distance between the researcher and respondents and can reduce the desire to look good (Chang and Krosnick, 2009). Finally, our non-probability sample may pose some limitations for us to generalize our findings to all Asian Americans. While our descriptive analysis using geocoded information demonstrated an overall distribution of our study sample in the U.S., future studies may consider a probability-based approach to validate and enhance the generalizability of our findings. Despite these limitations, our findings regarding racism and firearm-related risks offer valuable implications for prevention efforts and suggest that further research with Asian Americans’ experiences of racism and firearm behavior is warranted.

5. Conclusion

Firearm sales in the U.S. have increased during the COVID-19 pandemic. This is one of the first studies to examine Asian Americans’ firearm behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic and that considered the effects of discrimination on firearm-related risks. This study bridges a critical gap by examining the associations between racism and firearm-related behaviors and intention among Asian Americans using a national sample. We have an urgent need to investigate further the compounded effects of racism amid the COVID-19 pandemic in this population.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Tsu-Yin Wu: Funding acquisition, Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Visualization. Hsing-Fang Hsieh: Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing, Visualization. Chong Man Chow: Methodology, Project administration, Writing – review & editing, Visualization. Xining Yang: Investigation, Resources, Writing – review & editing. Ken Resnicow: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Marc Zimmerman: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the participants who have generously given their time to this study. Alice Jo, Rainville and Kirsten Herold provided tireless editing and proofing assistance, and Aleezay Khan, Kelly Yan, and Vedhika Raghunathan assisted with formatting and literature review.

Funding

This research was funded by the Michigan Healthy Asian Americans Project Endowment Fund and CDC COVID-19 Supplement, 6 NU58DP006590-03-03.

Appendix A.

Table A1.

Measurement of three dimensions of racism experiences and firearm-related behaviors and intention.

| Racism: Direct Experience, Cultural Racism and Response | |

|---|---|

| Since the COVID-19 pandemic started in Mar. 2020, how often have the following ever happened to you? |

Response Options: 1 = Less than once a year 2 = A few times a year 3 = At least once a month 4 = A few times a month 5 = At least once a week 6 = Almost everyday |

|

Direct experience: Racial discrimination 9 items from Racial-Ethnic Discrimination Scale (Sladek et al, 2020) and 4 items from Major Experiences of Discrimination (William, 2008) Cronbach’s alpha: 0.98 |

|

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

|

Perceptions of culture racism Index of Race-Related Stress (IRRS)-Brief Version (Utsey et al., 2013) Cronbach’s alpha-0.92 |

|

| |

| |

| |

|

Responses to Racism: Anticipatory Racism-Related Stress Prolonged Activation and Anticipatory Race-Related Stress Scale (PARS) (Utsey, 1999) Cronbach’s alpha-0.95 |

|

| |

| |

|

| Firearm intention and Behaviors | |

|---|---|

| In this survey, when we say guns, we mean guns that are in working order and capable of being fired. This includes pistols, revolvers, shotguns and rifles, but does not include air guns, bb guns, starter pistols, or paintball guns. |

Response Options: 1= Yes 2= No |

| Gun Ownership Questions |

|

| |

| Since the COVID-19 pandemic started in Mar. 2020, have you or someone in your home… |

Response Options: 1= Yes 2= No |

| Gun Purchas Questions |

|

| |

| |

| |

|

ONLY RESPOND TO THIS QUESTION IF YOU RESPONDED “YES” TO Q4. Was this gun the first gun that someone in your household has purchased? | |

| Gun Storage Question: 5. Do you know where the gun(s) on your property are stored? |

Response Options: 1= Yes 2= No |

|

Gun Purchase Question: 5.1. Are any of the gun(s) on your property stored loaded? That is, the ammunition is in the magazine, revolver cylinder, and/or chamber of the gun. |

ONLY RESPOND TO THIS QUESTION IF YOU RESPONDED “YES” TO Q5. Response Options: 1=Yes, at least one gun on my property is stored loaded 2=No, none of the guns on my property are stored loaded 3=Not sure |

| Gun Carrying Question: Since the COVID-19 pandemic, have you carried a gun with you more frequently when you were outside your home? Please don’t count times you have carried a gun for hunting, target shooting, competitive shooting, or recreation. |

ONLY RESPOND TO THIS QUESTION IF YOU RESPONDED “YES” TO Q5. Was this gun the first gun that someone in your household has purchased? |

References

- Asian Pacific Policy and Planning Council, 2020. STOP AAPI HATE Reveals Widespread COVID-19 Related Harassment Across the U.S. Pacific Policy and Planning Council. https://www.asianpacificpolicyandplanningcouncil.org/stop-aapi-hate-reveals-widespread-covid-19-related-harassment-across-the-us/ (accessed 22 November 2021).

- Blau, P.M., 1977. Inequality and Heterogeneity: A Primitive Theory of Social Structure. Free Press. New York, New York.

- Branas C.C., Richmond T.S., Culhane D.P., Ten Have T.R., Wiebe D.J. Investigating the link between gun possession and gun assault. Am. J. Public Health. 2009;99:2034–2040. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.143099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brondolo E., Kelly K.P., Coakley V., Gordon T., Thompson S., Levy E., Tobin J.N., Sweeney M., Contrada R.J. The perceived ethnic discrimination questionnaire: development and preliminary validation of a community version. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2005;35:335–365. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2005.tb02124.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant W.W. Internalized racism’s association with African American male youth’s propensity for violence. J. Black Stud. 2011;42:690–707. doi: 10.1177/0021934710393243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell C.H., Chavous T.M., Barnett T.E., Kohn-Wood L.P., Zimmerman M.A. Social determinants of experiences with violence among adolescents: unpacking the role of race in violence. Phylon. 2002;50:87–113. doi: 10.2307/4150003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carter P.M., Walton M.A., Newton M.F., Clery M., Whiteside L.K., Zimmerman M.A., Cunningham R.M. Firearm possession among adolescents presenting to an urban emergency department for assault. Pediatrics. 2013;132:213–221. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-0163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter P.M., Walton M.A., Roehler D.R., Goldstick J., Zimmerman M.A., Blow F.C., Cunningham R.M. Firearm violence among high-risk emergency department youth after an assault injury. Pediatrics. 2015;135:805–815. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-3572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism, 2021. Report to the Nation: Anti-Asian Prejudice and Hate Crime. https://www.csusb.edu/sites/default/files/Report%20to%20the%20Nation%20-%20Anti-Asian%20Hate%202020%20Final%20Draft%20-%20As%20of%20Apr%2030%202021%206%20PM%20corrected.pdf (accessed 22 November 2021).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020. Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS). National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. http://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/index.html (accessed 22 November 2021).

- Chang L., Krosnick J.A. National surveys via RDD telephone interviewing versus the internet: comparing sample representativeness and response quality. Public Opinion Quart. 2009;73:641–678. doi: 10.1093/poq/nfp075. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chung R.Y., Li M.M. Anti-Chinese sentiment during the 2019-NCoV outbreak. Lancet. 2020;395:686–687. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30358-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devakumar D., Shannon G., Bhopal S.S., Abubakar I. Racism and discrimination in COVID-19 responses. Lancet. 2020;395:1194. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30792-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ESRI, 2021. ArcGIS Pro: Release 2.8. Environmental Systems Research Institute, Redlands, CA.

- Hamilton D., Lemeshow S., Saleska J.L., Brewer B., Strobino K. Who owns guns and how do they keep them? the influence of household characteristics on firearms ownership and storage practices in the United States. Prev. Med. 2018;116:134–142. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2018.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kravitz-Wirtz, N., Aubel, A., Schleimer, J., Pallin, R., Wintemute, G., 2021. Public concern about violence, firearms, and the COVID-19 pandemic in California. JAMA Netw Open. 4, e2033484. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.33484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Krieger N. Embodying inequality: a review of concepts, measures, and methods for studying health consequences of discrimination. Int. J. Health Serv. 1999;29:295–352. doi: 10.2190/M11W-VWXE-KQM9-G97Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K., Charbria A. Gun Sales Are Surging in Many States; Los Angeles Times: 2020. As the Coronavirus Pandemic Grows. https://www.latimes.com/world-nation/story/2020-03-15/coronavirus-pandemic-gun-sales-surge-us-california (accessed 22 November 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lee E., Johnstone M. Resisting the politics of the pandemic and racism to foster humanity. Qual. Soc. Work. 2020;20:225–232. doi: 10.1177/1473325020973313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, M., Hatzipanagos, R., 2020. National Shooting Sports Foundation (NSSF) Survey Reveals Broad Demographic Appeal for Firearm Purchases During Sales Surge of 2020. NSSF. https://www.nssf.org/articles/nssf-survey-reveals-broad-demographic-appeal-for-firearm-purchases-during-sales-surge-of-2020/ (accessed 22 November 2021).

- Lowry R., Powell K.E., Kann L., Collins J.L., Kolbe L.J. Weapon-Carrying, Physical Fighting, and Fight-Related Injury among U.S. Adolescents. Am. J. Preventive Med. 1998;14:122–129. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(97)00020-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer P., McIntosh S. The USA today index of ethnic diversity. Int. J. Public Opinion Res. 1992;4:51–58. doi: 10.1093/ijpor/4.1.51. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Monuteaux M.C., Azrael D., Miller M. Association of increased safe household firearm storage with firearm suicide and unintentional death among U.S. youths. JAMA. Pediatrics. 2019;173(7):657. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.1078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center, 2017. America’s Complex Relationship With Guns. https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2017/06/22/the-demographics-of-gun-ownership/ (accessed 22 November 2021).

- Schleimer, J.P., McCort, C.D., Pear, V.A. et al. 2020. Firearm purchasing and firearm violence in the first months of the coronavirus pandemic in the United States. medRxiv. Preprinted published online July 11, 2020. doi:10.1101/2020.2007.2002.20145508.

- Schleimer J.P., McCort C.D., Pear V.A. Firearm purchasing and firearm violence in the first months of the coronavirus pandemic in the United States: a Cross-Sectional Study. Injury Epidemiol. 2021 doi: 10.1186/s40621-021-00339-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellers R.M., Caldwell C.H., Schmeelk-Cone K.H., Zimmerman M.A. Racial identity, racial discrimination, perceived stress, and psychological distress among African American Young Adults. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2003;44:302–317. doi: 10.2307/1519781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma A., Borah S.B. Covid-19 and domestic violence: an indirect path to social and economic crisis. J. Fam. Violence. 2020:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s10896-020-00188-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher L. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on suicide rates. QJM: Int. J. Med. 2020;113:707–712. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcaa202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sladek, M. R., Umaña-Taylor, A. J., Mcdermott, E. R., Rivas-drake, D., Martinez-Fuentes,S., 2020. Testing Invariance of Ethnic-Racial Discrimination and Identity Measures for Adolescents Across Ethnic-Racial Groups and Contexts. 32, 509–526. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000805. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sokol R.L., Zimmerman M.A., Rupp L., Heinze J.E., Cunningham R.M., Carter P.M. Firearm purchasing during the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in households with teens: a national study. J. Behav. Med. 2021;44:874–882. doi: 10.1007/s10865-021-00242-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau, 2020. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/decennial- census/decade/2020/2020-census-main.html (accessed 22 November 2021).

- Utsey S. Development and validation of a short form of the index of race-related stress (IRRS)-brief version. Measure. Eval. Counsel. Develop. 1999;32:149–172. doi: 10.1080/07481756.1999.12068981. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Utsey S.O., Belvet B., Hubbard R.R., Fischer N.L., Opare-Henaku A., Gladney L.L. Development and validation of the prolonged activation and anticipatory race-related stress scale. J. Black Psychol. 2013;39:532–559. doi: 10.1177/0095798412461808. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Williams D.R., Gonzalez H.M., Williams S., Mohammed S.A., Moomal H., Stein D.J. Perceived discrimination, race and health in South Africa. Soc. Sci. Med. 2008;67:441–452. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]