Abstract

Mobile health (mHealth) apps have the potential to enhance pain management through the use of daily diaries, medication and appointment reminders, education, and facilitating communication between patients and providers. Although many pain management apps exist, the extent to which these apps use evidence-based behavior change techniques (BCTs) remains largely unknown, making it nearly impossible for providers to recommend apps with evidence-based strategies. This study systematically evaluated commercially available pain management apps for evidence-based BCTs and app quality. Pain management apps were identified using the search terms “pain” and “pain management” in the App and Google Play stores. Reviewed apps were specific to pain management, in English, for patients, and free. A total of 28 apps were coded using the taxonomy of BCTs. App quality was assessed using the Mobile App Rating Scale. Apps included 2 to 15 BCTs (M = 7.36) and 1 to 8 (M = 4.21) pain management–specific BCTs. Prompt intention formation, instruction, behavioral-health link, consequences, feedback, and self-monitoring were the most common BCTs used in the reviewed apps. App quality from the Mobile App Rating Scale ranged from 2.27 to 4.54 (M = 3.65) out of a possible 5, with higher scores indicating better quality. PainScale followed by Migraine Buddy demonstrated the highest number of overall and pain management BCTs as well as good quality scores. Although existing apps should be assessed through randomized controlled trials and future apps should include capabilities for electronic medical record integration, current pain management apps often use evidence-based pain management BCTs.

Keywords: Pain self-management, Behavior change techniques, mHealth, Pain apps

1. Introduction

As outlined by the Pain Management Best Practices Inter-Agency Task Force,18 treatment of chronic pain should adhere to a biopsychosocial multimodal approach. Effective management of pain typically includes psychoeducation, symptom monitoring, identification of triggers and relief, and adherence to pharmacological and nonpharmacological treatment recommendations (eg, restorative, behavioral, and complimentary and integrative health therapies).4,18,25 However, obtaining optimal pain management support and skills training during face-to-face medical appointments may not be feasible because of time, cost, insurance coverage, and demand constraints.8,20,24 Technology-based interventions for pain management are an effective way to provide self-management skills in light of these constraints.7,9,10,28,30 Furthermore, patients and providers are increasingly using mobile health (mHealth) apps to provide both education and self-management skills. Although thousands of mHealth apps related to pain management are available, there is no published guidance for healthcare providers on how to identify and recommend commercially available, user-friendly, evidence-based pain management apps.5,14

Several reviews before 2017 concluded that pain management apps were overly simplistic, lacked provider insight in the development, and had not been rigorously tested.14,15,22 The mHealth landscape has significantly changed since these reviews and, although apps continue to need rigorous efficacy testing, systematic guidance regarding the selection of mHealth apps that include evidence-based strategies is a critical need. Systematically reviewing apps using the taxonomy of behavior change techniques (BCTs) provides a structure to reliably identify operationalized, theory-derived BCTs used in interventions such as self-monitoring, specific goal setting, stress management, and instruction (see Ref. 1 for full list). The BCT taxonomy has been used to assess and develop face-to-face behavioral health interventions for a variety of pain populations11,17 and has successfully been adapted to specifically assess BCTs in mHealth interventions.12,21 Thus, as patients and providers are increasingly turning to health technology to support pain management, there is a critical need to understand the extent to which evidence-based behavior change strategies have been translated to available pain management apps.

The current study sought to address this gap in the extant literature by evaluating the presence of evidence-based BCTs in commercially available pain management apps and their quality. Specifically, the aims of this study are to (1) systematically evaluate the content of free, publicly available pain management apps using Abraham and Michie’s theory-driven taxonomy of BCTs1 to assess the presence of overall BCTs and pain management–specific BCTs; (2) evaluate the quality of pain management apps using a validated rating system (Mobile Application Rating Scale [MARS26]); and (3) provide recommendations for providers and patients based on the presence of evidence-based BCTs and usability.

2. Method

2.1. Identification of pain management behavior change techniques and coding manual training

A narrative review of the chronic pain management literature was conducted in October 2019 to identify pain management BCTs. Our search examined PubMed, Cochrane Library, and Google Scholar databases. Reviewed titles and abstract were limited to those focusing on chronic pain in humans that were published in English. The search was not limited by age, specific chronic pain populations, or time. Additional inclusion criteria were (1) including individuals with chronic pain and (2) examining or reviewing behavior change strategies for pain management. Meta-analyses, systematic reviews, and intervention papers including patients of all ages were among the articles reviewed. Unpublished data, abstracts, and dissertations were excluded from analyses. Search terms included pain management OR pain self-management AND behavior change techniques OR behavior change strategies; self-management guidelines AND chronic pain; self-management OR pain management AND chronic pain AND behavior change techniques OR BCTs.

The first author reviewed the abstract and full text of each article for relevant results. References for these studies were also reviewed to find additional articles. A written synopsis of key findings and future directions was discussed with a team of experts in pain management BCTs.

Findings from the narrative review and consultation with experts in pain management BCTs revealed 8 BCTs that have consistently demonstrated efficacy in improving pain outcomes and therefore have been recommended for inclusion in pain management interventions and are herein referred to as “pain management BCTs.” Pain management BCTs include (1) behavior-health link, which provides psychoeducation regarding the relationship between a specific behavior and the user’s health; (2) consequences, or psychoeducation, which informs the user of the consequences likely to occur if the targeted health behavior change is made or not; (3) instruction, which provides the user information on how to perform the target behavior; (4) prompt intention formation, which involves encouraging the user to set a general goal related to a health behavior change; (5) prompt specific goal setting, which involves detailed planning of a goal (eg, when, where, what, and how long) and subsequently aims to increase practice, mastery, and self-efficacy in a self-management technique; (6) self-monitoring or use of written tracking behavior completion to promote accountability and identification of successes and barriers; (7) social support/change, which encourages the user to think about how others could change their behavior to promote behavior change or provide such support during the intervention; and (8) stress management, which incorporates relaxation training to relieve anxiety and tension, so the proposed goal can be achieved.7,9,14,25,27

Six raters received approximately 10 hours of training on BCTs for mHealth coding manual (see Ref. 21 for the development of manual). Training sessions were led by authors with extensive experience coding BCTs (K.L.G. and R.R.R.). Raters included PhD-level behavioral scientists with an understanding of psychological interventions and BCTs. Training consisted of distinguishing between techniques and reviewing examples of BCTs in mHealth apps. Raters downloaded and interacted with 4 common apps for a minimum of 10 minutes each to independently code the presence of BCTs as described in the coding manual. Raters then met with the senior authors to discuss discrepancies and reach consensus. Following this, raters then individually coded 5 pain management apps using the same procedure. All procedures were in accordance with the Declaration of the World Medical Association.

2.2. Identification of mHealth apps for pain management

A series of 4 systematic searches were conducted to identify mHealth apps for pain management. The terms “pain” and “pain management” were searched in the Apple iOS App Store and the Google Play store. In an effort to simulate a consumer app search and because an exhaustive search of all apps is not possible, a list of the first 25 apps for each of these 4 searches was recorded. This protocol is consistent with recent research that only 14% of users download an app that is not in the top 10. This approach also takes into account the complex algorithm used by the App/Google Play store, which considers the description, download frequency, structure, and retention rate of each app.3,6,21 Duplicates were removed and apps were included for coding if they specified being pain related in the description, were free of cost, patient-facing (for patient use), and in English. Specifically, apps with an affiliated cost were not included on the basis that even minimal download fees for apps are a deterrent to patients.29

2.3. Using behavior change techniques and the Mobile App Rating Scale to code pain management apps

The apps were independently coded for the presence or absence of the 26 BCTs. In addition, each rater coded apps using the MARS,26 a 23-item measure that assesses the quality of mHealth apps across 5 domains: Engagement (entertainment quality, interest level, customization options, and interactivity), Functionality (technical performance, ease of use, navigation, and gestural design), Aesthetics (layout, graphics, and visual appeal), Information (accuracy of app description, goals, quality of information, quantity of information, visual information, credibility, and evidence base), and Subjective Quality (recommendation of the app to target audience, estimated frequency of use, app worth, and coder’s overall star rating).Items in each of these domains contain between 3 and 7 questions that are rated on a 5-point scale from 1 (inadequate) to 5 (excellent). Item responses in each domain were averaged to obtain Engagement, Functionality, Aesthetics, Information, and App Subjective Quality subscale scores. An overall quality score was produced by averaging the 5 mean subscale scores.

2.4. Evaluation of interrater reliability

To assess interrater reliability, at least 20% of the apps were randomly selected to be double coded using the BCT manual (n = 8) and the MARS (n = 6). Percent agreement was calculated to assess interrater reliability between coders on the 26 BCTs, and a third coder was assigned to reach consensus on BCT coding. Intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) were computed to assess agreement between raters on the MARS scores, and retraining was provided as necessary to improve agreement.

3. Results

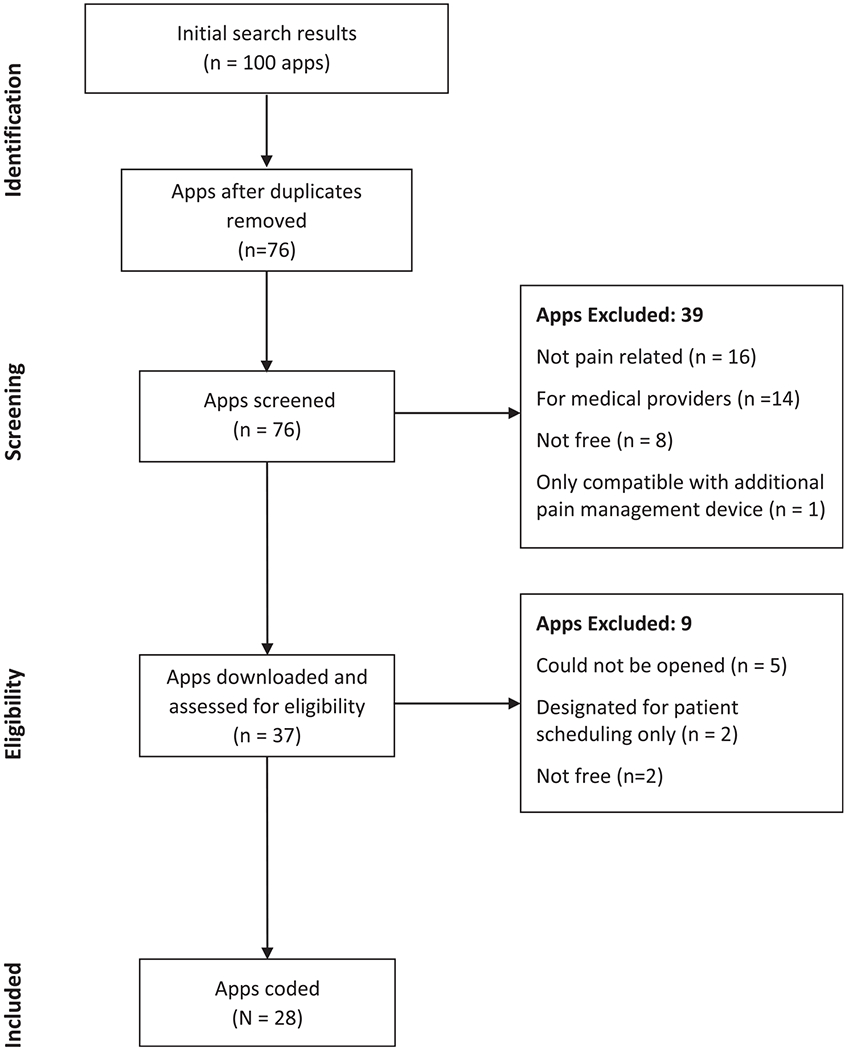

Initial searches using the terms “pain” and “pain management” revealed 100 apps. Of these, 63 apps were initially removed for the following reasons: 24 apps were duplicates, 16 were not pain related, 14 apps were for medical providers rather than individuals with chronic pain, 8 apps had an associated cost, and 1 app could not be used without an additional pain management device. Of the 37 apps downloaded to be coded, 9 apps were removed for the following reasons: 5 could not be opened after multiple attempts, 2 apps were specifically for patient scheduling, and 2 were not free. Thus, 28 apps were downloaded and successfully coded, with 9 (32%) of these apps being available across platforms (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

App search results.

Each of the apps used between 2 and 15 BCTs (MBCT = 7.36) and 1 and 8 pain management BCTs (ie, behavior-health link, consequences, instruction, prompt intention formation, prompt specific goal setting, self-monitoring, social support/change, and stress management; MPAINBCT = 4.21). Half of the apps (n = 11) used at least 5 pain management BCTs, whereas 17.86% (n = 5) used at least 4. Overall, the most commonly used BCTs were prompt intention formation, instruction, behavior-health link, consequences, and feedback, followed by self-monitoring, others’ approval, teach use prompt cues, and stress management; 6 of which are consistent with the extant literature of recommended pain management BCTs.11,14,24,25,27

“Prompt intention formation” found in 75% of the apps (n = 21) often encouraged the user to set a general pain management goal to elicit frequent practice of a new habit such as committing to tracking pain symptoms daily. “Instruction” also found in 75% of the apps (n = 21) provided text, graphics, or videos to teach the user how to perform a pain management behavior such as a specific stretching exercise. “Behavior-health link” was used in 71% of the apps (n = 20) and provided information about the relationship between a behavior and health (eg, psychoeducation on the relationship between regular exercise and reduced inflammation). Similarly, 68% of apps (n = 19) provided information on “consequences” or the pros/cons of engaging in a pain management behavior (eg, quality sleep can reduce pain while limited sleep may exacerbate it). “Self-monitoring” or digital tracking of a pain management behavior was available in 50% of apps (n = 14). “Stress management” was used in 39% of apps (n = 11) and included engaging in techniques that reduce tension and anxiety. Finally, “prompt specific goal setting” such that detailed planning of a pain management behavior is prompted was only used in 10 apps (36%) and “social support/change” was only used in 2 apps (7%).

The other commonly used BCTs that our literature review did not identify as being specifically recommended BCTs for pain management included feedback, others’ approval, teach use prompts/cues, and stress management. “Feedback” was used in 68% of apps (n = 19) and provided visual data on how well a user has performed in relation to a goal such as “You logged your symptoms on 4 of 7 days this week.” “Others’ approval” was used in 46% of apps (n = 13) and often involved either providing information on what others (eg, physician and caregiver) might think of the user’s pain management behaviors or the ability to share this information completion of pain management behavior tracking. Finally, “teach use prompts/cues” found in 39% of apps (n = 11) aided the user in identifying prompts to serve as reminders to perform a pain management behavior, such as setting alarms/push notifications to take medication or stretch. Refer to Table 1 for additional in-app examples of these BCTs.

Table 1.

Examples of the most frequently used BCTs in coded apps.

| BCT | Definitions and examples used in apps |

|---|---|

| Behavior-health link | Information about the relationship between the behavior and health is described in the app. 1. The app gives users the following tip: “neck exercises can help you to release tension, tightness, and stiffness. They can reduce pain and increase flexibility. A strong neck can help to prevent neck and cervical spine injuries as well” (Neck & Shoulder Pain Relief Exercises, Stretches). 2. In one of the learning modules, the app informs users, “several factors can contribute to nonspecific back pain, such as lifestyle, stress level, and how much physical activity a person gets” (Back Pain Exercises). |

| Consequences | The app provides information focusing on what will happen if the person performs the target behavior. 1. In reference to the tracking logs within the app, it is stated “records of your pain can help health professionals gain an insight into the pain you are experiencing” (Pain Log—Pain Tracker). 2. The app provides information about the benefits of completing mindfulness exercises (eg, stress reduction, “unwinding” before going to bed; Mindfulness Daily). |

| Others’ approval | Includes information in the app about what other people think about the target person’s behavior. 1. The app allows users to share their information on a community page and others can comment and “cheer” them on (Ouchie). 2. The app has an option to share the user’s pain report with their doctor through email (PainScale). |

| Prompt intention formation | The app encourages the person to set a general goal or make a behavioral resolution. 1. The app prompts users to make a commitment to set general goals related to tracking pain, trying an exercise, and reflecting on results (Pain Care app). 2. The app prompts users to set a general goal of tracking their pain via adding a pain record on the app (Manage My Pain). |

| Instruction | The app tells the person how to form a behavior or preparatory behaviors. 1. The app instructs users how to perform breathing exercises when they are experiencing fear of pain, including “inhale deeply but comfortably all the way into the lower part of our lungs” (Pathways Pain Relief). 2. The app provides audio sessions that include verbal instructions about how to complete deep breathing exercises and other relaxation techniques (Pain Care app). |

| Self-monitoring | The person is asked to keep a record of a specified behavior in the app (eg, a diary). 1. The app allows user to “add pain record” to log their pain for the day, severity, triggers, and how the pain was treated (Manage My Pain). 2. Users can log their pain, triggers, symptoms, and treatments at any given time (Pain Dairy—Pain Management). |

| Feedback | The person receives data about a recorded behavior through the app. 1. Users are provided with frequency data for workouts, workout time, and exercises completed (Back Pain Exercises). 2. Users can view a report of their logged data including total days with pain, average duration of pain, average days between pain, and average pain score (My Pain Log). |

| Teach use prompt cues | The app teaches the person to identify environmental prompts that can be used to remind them to perform the behavior, including automated scheduled reminders (ie, push notification). 1. The app allows user to set reminders to prompt them to workout (ie, “hey it’s time to work out!” Neck & Shoulder Pain Relief Exercises, Stretches). 2. The app sends user reminders to log their pain (ie, “how is your pain? Tap to record it.”) (Manage My Pain). |

| Stress management | Included in the app are various specific techniques that seek to reduce anxiety and stress to facilitate the performance of the behavior. 1. The app includes information, through various articles within the app, to relieve stress (eg, deep breathing, progressive relaxation, guided imagery; Fibromyalgia Test and Training). 2. The app offers training in mindfulness and stress management exercises, such as deep breathing (Mindfulness Daily). |

BCT, behavior change technique.

When examining specific apps, 4 apps consistently had the most overall BCTs (ie, PainScale [n = 15], Mindfulness Daily [n = 15], Migraine Buddy [n = 13], and Ouchie [n = 12]) and the most pain management BCTs (ie, PainScale [n = 8], Mindfulness Daily [n = 7], Ouchie [n = 7], and Migraine Buddy [n = 6]). PainScale, Mindfulness Daily, Migraine Buddy, and Ouchie all included the pain management BCTs of behavior-health link, consequences, prompt intention formation, instruction, and self-monitoring. PainScale, Mindfulness Daily, and Ouchie also used prompt specific goal setting, whereas PainScale and Migraine Buddy included social support/change. Of the remaining 24 apps reviewed, 9 used 7 to 10 BCTs and 13 apps used fewer than 7 BCTs overall. Table 2 provides a list of BCTs included in each of the 28 apps.

Table 2.

Behavioral change techniques used in coded apps.

| App name | BCT | Behavior-health link* | Consequences* | Others’ approval | Prompt intention formation* | Prompt barrier identification | General encouragement | Graded tasks | Instruction** | Model/demonstrate | Prompt specific goal setting* | Self-monitoring* | Feedback |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PainScale | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Mindfulness Daily | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Ouchie | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Migraine Buddy | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Pathways Pain Relief | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Pain Relief Hypnosis—Chronic Pain Management | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Back Pain Exercises | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Pain Care app | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| Curable | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| Fibromyalgia Test and Training | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| Migraine Relief Hypnosis—Headache & Pain Help | X | X | X | X | |||||||||

| Tally: The Anything Tracker | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| GeoPain | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| Manage My Pain | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| No More Pain | X | X | X | X | |||||||||

| Pain Management/Relief | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| 6-Minute Back Pain Relief | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Chronic Pain Diary | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| Chronic Pain Tracker Lite | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Pain Scored | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Orientate | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Pain Log—Pain Tracker | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| My Pain Log | X | X | X | X | |||||||||

| Pain Management | X | X | X | X | |||||||||

| Right Motion: Relief your pain only with exercises | X | X | X | X | |||||||||

| Neck & Shoulder Pain Relief Exercises, Stretches | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Pain Diary—Pain Management Log | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| Self Pain Management | X | X | |||||||||||

| Totals | 20 | 19 | 13 | 21 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 21 | 10 | 10 | 14 | 19 | |

| App name | Contingent rewards | Teach use prompt cues | Behavioral contract | Prompt practice | Follow-up prompts | Social comparison | Social support/change* | Prompt self-talk | Relapse prevention | Stress management* | Time management | Number of BCTs | Number of pain management BCTs |

| PainScale | X | X | X | X | X | X | 15 | 8 | |||||

| Mindfulness Daily | X | X | X | X | X | 15 | 7 | ||||||

| Ouchie | X | X | X | 12 | 7 | ||||||||

| Migraine Buddy | X | X | X | X | X | 13 | 6 | ||||||

| Pathways Pain Relief | X | X | 10 | 6 | |||||||||

| Pain Relief Hypnosis—Chronic Pain Management | X | X | 7 | 6 | |||||||||

| Back Pain Exercises | X | 8 | 5 | ||||||||||

| Pain Care app | X | X | X | X | X | X | 12 | 5 | |||||

| Curable | X | X | X | X | X | 11 | 5 | ||||||

| Fibromyalgia Test and Training | X | X | 8 | 5 | |||||||||

| Migraine Relief Hypnosis—Headache & Pain Help | X | 5 | 5 | ||||||||||

| Tally: The Anything Tracker | X | X | 8 | 4 | |||||||||

| GeoPain | X | 7 | 4 | ||||||||||

| Manage My Pain | X | 7 | 4 | ||||||||||

| No More Pain | X | 5 | 4 | ||||||||||

| Pain Management/Relief | X | 4 | 4 | ||||||||||

| 6-Minute Back Pain Relief | X | X | 7 | 3 | |||||||||

| Chronic Pain Diary | 6 | 3 | |||||||||||

| Chronic Pain Tracker Lite | X | 6 | 3 | ||||||||||

| Pain Scored | X | 6 | 3 | ||||||||||

| Orientate | 5 | 3 | |||||||||||

| Pain Log—Pain Tracker | 5 | 3 | |||||||||||

| My Pain Log | 4 | 3 | |||||||||||

| Pain Management | 4 | 3 | |||||||||||

| Right Motion: Relief your pain only with exercises | 4 | 3 | |||||||||||

| Neck & Shoulder Pain Relief Exercises, Stretches | X | X | 7 | 2 | |||||||||

| Pain Diary—Pain Management Log | 3 | 2 | |||||||||||

| Self Pain Management | 2 | 1 | |||||||||||

| Totals | 9 | 11 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 11 | 1 | 206 | 118 |

Denotes pain management BCTs.

BCT, behavior change technique.

The overall quality of apps ranged from 2.27 to 4.54 (MMARSoverall = 3.57) out of a possible 5.0. Five apps had an overall quality score higher than 4 (ie, PainScale, Migraine Buddy, Pain Management/Relief, Manage My Pain, and Back Pain Exercises). Seventeen apps had a MARS overall quality score between 3.5 and 4.0. MARS subscale scores for each app can be found in Table 3.

Table 3.

Mean scores for MARS subscales.

| App name | App information |

Means for subscales and overall scores on the MARS |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Available platform(s) | App store rating (iOS/Android)‡ | Age range† | Developer | Engagement | Functionality | Aesthetics | Information | App subjective quality | Overall app Quality | |

| PainScale | Both | 4.5/4.4 | Adolescent + | Boston Scientific | 4.8 | 4.5 | 4.67 | 4.5 | 4.25 | 4.54 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Migraine Buddy * | Both | 4.8/4.7 | Adolescent + | Healint | 4.3 | 4.5 | 4.67 | 3.83 | 3.63 | 4.19 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Pain Management/Relief | Android | N/A | General | Great_Apps | 3.2 | 5 | 5 | 3.67 | 3.5 | 4.07 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Manage My Pain | Both | 4.8/4.5 | Adolescent + | ManagingLife | 4.2 | 4.5 | 4.33 | 3.75 | 3.5 | 4.06 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Back Pain Exercises | Both | 4.7/4.8 | General | Vladimir Ratsev | 4.4 | 4.75 | 4.33 | 3.67 | 3 | 4.03 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Curable | Both | 4.3/3.5 | Adolescent + | Curable Inc. | 3.4 | 3.5 | 4.67 | 4.2 | 4 | 3.95 |

|

| ||||||||||

| GeoPain | iOS | 4.1 | Adolescent + | MoxyTech | 4.4 | 4.5 | 3.67 | 3.5 | 3.5 | 3.91 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Tally: The Anything Tracker | iOS | 4.8 | General | treebetty LLC | 3.8 | 3.75 | 4 | 4.25 | 3.75 | 3.91 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Fibromyalgia Test and Training | iOS | 3 | General | CogniFit | 3.8 | 4.5 | 4.33 | 3.5 | 3 | 3.83 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Mindfulness Daily | iOS | 4.7 | General | Inward, Inc | 4 | 3.25 | 4 | 4.17 | 3.5 | 3.78 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Pathways Pain Relief‡ | Both | 3.6/4.2 | Adolescent + | Pathways Health | 3.7 | 3.75 | 4.17 | 3.75 | 3.5 | 3.77 |

|

| ||||||||||

| My Pain Log | iOS | 3.8 | General | Samantha Roobol | 3.2 | 5 | 4 | 3.75 | 2.75 | 3.74 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Orientate—Pain Management | iOS | 4.2 | General | Reflex Pain Management Ltd. | 2.8 | 4.75 | 3.67 | 4.25 | 3.25 | 3.74 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Pain Diary—Pain Management Log | Android | 2.8 | General | Stay Fit with Samantha | 3.2 | 5 | 4 | 3.75 | 2.75 | 3.74 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Ouchie | Both | 4.4/3.8 | Adolescent + | Ouchie LLC/Upside Health (iOS/Android) | 3.8 | 3.25 | 4.33 | 4 | 3.25 | 3.73 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Neck & Shoulder Pain Relief Exercises, Stretches | Android | 4.5 | General | OHealthApps Studio | 3.8 | 4.5 | 4.33 | 3.17 | 2.75 | 3.71 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Pain Care app | iOS | 5 | Adolescent + | appliedVR, Inc. | 3.6 | 3.5 | 4.33 | 3.83 | 3.25 | 3.7 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Pain Log—Pain Tracker | Android | 3.6 | General | Skillo Apps | 3.2 | 4.25 | 4.33 | 3.5 | 3 | 3.66 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Pain Relief Hypnosis—Chronic Pain Management | Android | 4.4 | General | Surf City Apps | 3.8 | 4.25 | 4 | 3.33 | 2.75 | 3.63 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Six-Minute Back Pain Relief | Both | 3/4.4 | General | Round1Fight | 3.6 | 4.25 | 4 | 3.5 | 2.75 | 3.62 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Right Motion: Relief your pain only with exercises | Android | 4.5 | General | Thiago Nishida | 3.6 | 4 | 4.33 | 3.5 | 2.25 | 3.54 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Chronic Pain Tracker Lite ‡ | iOS | 3.7 | General | Chronic Stimulation LLC | 3.5 | 3.88 | 3.17 | 3.75 | 3.38 | 3.53 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Migraine Relief Hypnosis—Headache & Pain Help | Android | 4.2 | General | Surf City Apps | 3.2 | 4.5 | 4.33 | 2.4 | 2.75 | 3.44 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Pain Scored ‡ | Both | 4.0/2.3 | Adolescent + | Patient Premier, LLC | 3.7 | 3.63 | 3.5 | 3.38 | 2.88 | 3.42 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Pain Management ‡ | Android | N/A | General | GaladimaApps | 2.2 | 4.88 | 3.5 | 3.5 | 2.63 | 3.34 |

|

| ||||||||||

| No More Pain ‡ | iOS | N/A | Adolescent + | Nicola Quinn | 2.8 | 4 | 3.5 | 2.9 | 2.63 | 3.17 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Chronic Pain Diary | iOS | 5 | General | Ben Delaporte | 2.8 | 3.25 | 3 | 2.67 | 1.5 | 2.64 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Self Pain Management | iOS | N/A | General | Rahul Garg | 2.2 | 2.5 | 3.67 | 2 | 1 | 2.27 |

|

| ||||||||||

| All apps: M (SD) | 3.51 (0.64) | 4.13 (0.61) | 4.01 (0.5) | 3.56 (0.53) | 3.04 (0.65) | 3.65 (0.43) | ||||

These apps were rated by multiple coders, and their average scores on the MARS were used.

MARS descriptors for age: children (under 12), adolescents (13-17), young adults (18-25), adults, and general.

“App Store Ratings” are subjective user ratings found in the app store that range from 1 to 5 stars. MARS scores range from 1 (inadequate) to 5 (excellent).

Percent agreement was 91% or higher for 20 of the BCT classifications. Percent agreement was 87% for instruction, prompt specific goal setting, provide contingent rewards, and prompt practice, 84% for model/demonstrate, and 80% for others’ approval. Intraclass correlation coefficients for the MARS were all in the excellent range13: MARS A: Engagement = 0.99, MARS B: Functionality = 0.96, MARS C: Aesthetics = 0.93, MARS D: Information = 0.95, and MARS Overall App Quality = 0.94.

4. Discussion

The current study fills a gap in the extant literature, as the first systematic evaluation of commercially available pain management apps examining BCTs and app quality so that healthcare providers may make informed recommendations to patients with chronic pain. Twenty-eight commercially available pain management apps were evaluated, and each app included between 2 and 15 BCTs and between 1 and 8 pain management–specific BCTs. The MARS overall app quality ranged from fair to excellent. Overall, findings suggest promise with regard to both the content and quality of currently available pain management apps.

Specifically, results were consistent with the pain management BCTs’ recommendations in the extant literature,7,9,14,25,27 such that 5 of the 8 (behavior-health link, consequences, prompt intention formation, instruction, and self-monitoring) were also the most commonly used BCTs. This suggests that, overall, pain management app developers have integrated evidence-based self-management strategies from existing digital and face-to-face interventions into their apps. There are several advantages to translating recommended pain management BCTs into mHealth platforms, including the compact portable platform and accessibility to pain management techniques and educational resources outside of a healthcare setting. For example, incorporating information on the link between specific behaviors and health, associated consequences, and goal setting into mHealth apps allows patients to have access to these educational materials and their health goals on their smartphone at all times. Other benefits include the ability to track and log symptoms passively and in real time (eg, ecological momentary assessment16) or “in-the-moment” instructions about how to perform an intervention behavior.

Interestingly, 2 of the BCTs that our literature review identified as evidence-based pain management BCTs, prompt specific goal setting and social support/change, were rarely used in pain management apps. Chronic pain is often both a physically and mentally debilitating experience that can feel overwhelming for patients to navigate alone. Although it is crucial to help patients make informed decisions to improve their health (prompt intention formation), recognize and understand relationships between pain management behaviors and their health outcomes (behavior-health link and consequences), and properly perform and track pain management behaviors (instruction and self-monitoring), these strategies are more likely to evoke meaningful change when done in combination with setting detailed, concrete goals (specific goal setting) and establishing relationships and accountability with others (social support/change).14,24,27 One way to incorporate specific goal setting into apps would be to prompt users to set a specific goal following the identification of general goals related to pain management. For example, users could be prompted to specify the frequency, intensity, duration, location, time, and method of the goal behavior.1 Requesting this detailed level of information regarding the health behavior goal will set the user up for success by aiding them in thinking through the logistics, definition of success, and timeliness of the goal. In addition, nearly all the pain management apps evaluated may improve their impact with the incorporation of social support/change14 by providing psychoeducation on the importance of social support in the context of pain management or by including a digital “buddy system” or interactive messenger system within the app community.

Other BCTs that were frequently used in the evaluated pain management apps included providing feedback on performance, information about others’ approval, and teaching users to use prompts/cues. Although these BCTs were not identified as having the highest level of evidence based on the extant pain management literature, there is existing evidence for the use of these BCTs to improve pain management.12 In addition, these BCTs are some of the most frequently used strategies in mHealth apps,21 and a significant advantage of app utilization is the ability to customize user experience with respect to feedback, the incorporation of reminders, and the ability to quickly share data with others. These same features are also used within the app world and can further assist the user in identifying adaptive and maladaptive patterns (eg, symptom triggers and relievers) and make use of their self-monitoring data (eg, progress towards goals). Additional research regarding the evidence base of these BCTs would aid in our understanding of their incorporation in mobile apps.

Pain management healthcare providers acknowledge the need for apps to aid in pain management,18 and the “prescribability” of apps has become a significant topic of discussion.2 Although evidence of efficacy through low risk-of-bias randomized controlled trials (RCTs) is necessary to definitively establish the efficacy of pain management apps and allow for true “prescribability” of apps, reviewing the evidence-based BCTs included within mHealth apps can aid clinicians and patients in making mHealth recommendations while large-scale RCTs are being conducted .Based on this evaluation of BCTs and app quality, PainScale and Migraine Buddy contained the most pain management BCTs and the highest usability ratings, suggesting these apps provide behavioral techniques that have been shown to improve pain management in previous research and are likely to be engaging for users.

PainScale, which included all 8 pain management BCTs, is a general pain management app appropriate for users with various chronic pain symptoms and conditions. The app includes a comprehensive daily diary, which can synthesize and send to a provider data related to symptoms and pain correlates such as triggers, relievers, and medications. Migraine Buddy used 6 of the pain-specific BCTs, had a high overall app quality, and may be particularly useful for patients with migraine, given its ability to share information with providers, track triggers, and reliefs as well as calculate a Migraine Disability Assessment score.23 Finally, Back Pain Exercises also had both a high number of pain management BCTs and a high-quality score and may be beneficial for patients with chronic back pain, as the app provides instructions for stretches/exercises targeted at decreasing pain and increasing functioning.

Despite the rigorous systematic search and evaluation protocol used, there are several limitations to this study that should be considered. First, this systematic evaluation is not an exhaustive review of all pain management apps. Limitations to the breath of this review include the exclusion of apps that have an affiliated cost, only broad searches for “pain” and “pain management” in the United States were conducted (eg, specifiers of specific pain populations or conditions were not included in search terms), and only the initial 25 apps were evaluated. Although app store results are based on a complex algorithm taking into account app popularity, reviews, and keywords, the list of apps generated from each search in this evaluation does not ensure that the highest quality apps or the apps with the most BCTs were presented. For example, apps such as WebMAP Mobile,19 MobileNetrix, and Pain Squad are available pain management apps that meet criteria for this review, but they were not included because they are not listed within the first 25 apps on the App/Google Play store. Despite this limitation, our methodology for identifying apps was selected based on use in previous published evaluations and the real-life applicability for providers and patients.3,29 Similarly, this review only includes mHealth apps and therefore did not review existing online pain management programs (eg, Pain Trainer and Pain Course). Second, because raters did not use apps for an extended period of time, it is possible that some BCTs may not have been evident during the evaluation time period. However, this minimum is in accordance with current guidelines and provides important information for making app recommendations.26 Third, although several apps included the ability to send provider-synthesized reports, none of the apps provided information on integrating data into electronic medical records or HIPAA compliance statements. Finally, none of the pain management apps reviewed in this study were identified as being tested in an RCT; therefore, although our app evaluation is based on evidence-based BCTs in the extant pain literature, studies evaluating the adherence and effectiveness of mHealth pain management apps in a sample of individuals with chronic pain is a crucial next step.

4.1. Future directions

This evaluation of commercially available pain management apps examined the quality and BCTs incorporated in the apps and can be used as an initial guide for making pain management app recommendations based on patient and provider preferences. Optimal pain management apps include behavior-health link, consequences, instructions, prompt intention formation, self-monitoring, stress management, prompting of specific goal setting, and social support/change. Currently available apps using these BCTs with high-quality ratings include PainScale, Migraine Buddy, and Back Pain Exercises. It is recommended that providers familiarize themselves with the app ensuring that they are aware of any potential bias of the developer or funder, platform availability for their patient base, and possibility for viewing of synthesized data. Continued reassessment of current pain management mHealth apps, RCTs of pain management apps, integration of apps with the electronic medical record, and improved dissemination of evidence-based mHealth pain management apps across platforms and through provider networks (eg, International Association for the Study of Pain and American Academy of Pain Medicine) are needed to ensure that patients have access to and providers are recommending the best possible pain management apps.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a career development award (grant no. K23HL139992) from the NHLBI and a training grant (grant no. T32HD068223) from the National Institutes of Health NICHD.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- [1].Abraham C, Michie S. A taxonomy of behavior change techniques used in interventions. Health Psychol 2008;27:379–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Byambasuren O, Sanders S, Beller E, Glasziou P. Prescribable mHealth apps identified from an overview of systematic reviews. Npj Dig Med 2018;1:12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Chavez S, Fedele D, Guo Y, Bernier A, Smith M, Warnick J, Modave F. Mobile apps for the management of diabetes. Diabetes Care 2017;40: e145–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Cheatle MD. Biopsychosocial approach to assessing and managing patients with chronic pain. Med Clin North Am 2016;100:43–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].de la Vega R, Mirö J. A strategic field without a solid scientific soul: a systematic review of pain-related apps. PLoS One 2014;9:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Dogruel L, Joeckel S, Bowman ND. Choosing the right app: an exploratory perspective on heuristic decision processes for smartphone app selection. Mob Media Commun 2015;3:125–44. [Google Scholar]

- [7].Eccleston C, Fisher E, Brown R, Craig L, Duggan GB, Rosser BA, Keogh E. Psychological therapies (Internet-delivered) for the management of chronic pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014:CD010152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Fashler SR, Cooper LK, Oosenbrug ED, Burns LC, Razavi S, Goldberg L, Katz J. Systematic review of multidisciplinary chronic pain treatment facilities. Pain Res Manag 2016;2016:1–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Fisher E, Law E, Dudeney J, Eccleston C, Palermo TM. Psychological therapies (remotely delivered) for the management of chronic and recurrent pain in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2019:CD011118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Hunter JF, Kain ZN, Fortier MA. Pain relief in the palm of your hand: harnessing mobile health to manage pediatric pain. Paediatr Anaesth 2019;29:120–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Keogh A, Tully MA, Matthews J, Hurley DA. A review of behaviour change theories and techniques used in group based self-management programmes for chronic low back pain and arthritis. Man Ther 2015;20: 727–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Kleiboer A, Sorbi M, van Silfhout M, Kooistra L, Passchier J. Short-term effectiveness of an online behavioral training in migraine self management: a randomized controlled trial. Behav Res Ther 2014;61: 61–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Koo TK, Li MY. A Guideline of selecting and reporting intraclass correlation coefficients for reliability research. J Chiropr Med 2016;15: 155–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Lalloo C, Jibb LA, Rivera J, Agarwal A, Stinson JN. “There’s a pain app for that”: review of patient-targeted smartphone applications for pain management. Clin J Pain 2015;31:557–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Lalloo C, Shah U, Birnie KA, Davies-Chalmers C, Rivera J, Stinson J, Campbell F. Commercially available smartphone apps to support postoperative pain self-management: scoping review. JMIR MHealth Uhealth 2017;5:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].May M, Junghaenel DU, Ono M, Stone AA, Schneider S. Ecological momentary assessment methodology in chronic pain research: a systematic review. J Pain 2018;19:699–716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Meade LB, Bearne LM, Sweeney LH, Alageel SH, Godfrey EL. Behaviour change techniques associated with adherence to prescribed exercise in patients with persistent musculoskeletal pain: systematic review. Br J Health Psychol 2019;24:10–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Pain Management Best Practices Inter-Agency Task Force. Pain management best practices inter-agency task force report: updates, gaps, inconsistencies, and recommendations. Washington: U.S. Department of Health & Human Services; 2019. Available at https://www.hhs.gov/ash/advisory-committees/pain/reports/index.html. Accessed January 5, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Palermo TM, de la Vega R, Dudeney J, Murray C, Law E. Mobile health intervention for self-management of adolescent chronic pain (WebMAP mobile): protocol for a hybrid effectiveness-implementation cluster randomized controlled trial. Contemp Clin Trials 2018;74:55–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Peng P, Choiniere M, Dion D, Intrater H, LeFort S, Lynch M, Ong M, Rashiq S, Tkachuk G, Veillette Y. Challenges in accessing multidisciplinary pain treatment facilities in Canada. Can J Anesth 2007; 54:977–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Ramsey RR, Caromody JK, Voorhees SE, Warning A, Cushing CC, Guilbert TW, Hommel KA, Fedele DA. A Systematic evaluation of asthma management apps examining behavior change techniques. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2019;7:2583–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Silva AG, Queirös A, Caravau H, Ferreira A, Rocha NP, editors. Systematic review and evaluation of pain-related mobile applications. Encycl E-Health Telemed. Hershey: IGI Global, 2020:383–400 (2016. reprint). [Google Scholar]

- [23].Stewart WF, Lipton RB, Kolodner KB, Sawyer J, Lee C, Liberman JN. Validity of the Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS) score in comparison to a diary-based measure in a population sample of migraine sufferers. PAIN 2000;88: 41–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Stinson J, White M, Isaac L, Campbell F, Brown S, Ruskin D, Gordon A, Galonski M, Pink L, Buckley N, Henry JL, Lalloo C, Karim A. Understanding the information and service needs of young adults with chronic pain: perspectives of young adults and their providers. Clin J Pain 2013;29:600–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Stinson JN, Lalloo C, Harris L, Isaac L, Campbell F, Brown S, Ruskin D, Gordon A, Galonski M, Pink LR, Buckley N, Henry JL, White M, Karim A. ICanCope with Pain™: user-centred design of a web- and mobile-based self-management program for youth with chronic pain based on identified health care needs. Pain Res Manag 2014;19:257–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Stoyanov SR, Hides L, Kavanagh DJ, Zelenko O, Tjondronegoro D, Mani M. Mobile App Rating Scale: a new tool for assessing the quality of health mobile apps. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2015;3:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Sundararaman LV, Edwards RR, Ross EL, Jamison RN. Integration of mobile health technology in the treatment of chronic pain: a critical review. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2017;42:488–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Thurnheer SE, Gravestock I, Pichierri G, Steurer J, Burgstaller JM. Benefits of mobile apps in pain management: systematic review. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2018;6:1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Vaghefi I, Tulu B. The continued use of mobile health apps: insights from a longitudinal study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2019;7:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Vardeh D, Edwards RR, Jamison RN, Eccleston C. There’s an app for that: mobile technology is a new advantage in managing chronic pain. Pain Clin Updates 2013;21:1–8. [Google Scholar]