Abstract

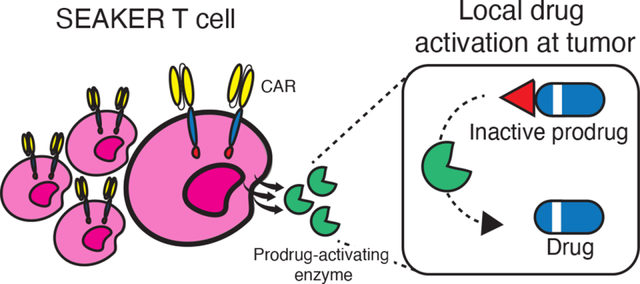

Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR)-T cells represent a major breakthrough in cancer therapy, wherein a patient’s own T cells are engineered to recognize a tumor antigen, resulting in activation of a local cytotoxic immune response. However, CAR-T cell therapies are currently limited to the treatment of B-cell cancers and their effectiveness is hindered by resistance from antigen-negative tumor cells, immunosuppression in the tumor microenvironment, eventual exhaustion of T-cell immunologic functions, and frequent severe toxicities. To overcome these problems, we have developed a novel class of CAR-T cells engineered to express an enzyme that activates a systemically-administered small-molecule prodrug in situ at a tumor site. We show that these Synthetic Enzyme-Armed KillER (SEAKER) cells exhibit enhanced anticancer activity with small-molecule prodrugs, both in vitro and in vivo in mouse tumor models. This modular platform enables combined targeting of cellular and small-molecule therapies to treat cancers and potentially a variety of other diseases.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Targeted cellular therapies are a promising new approach to treat cancers and other human diseases1–3. These living therapeutics undergo logarithmic proliferation triggered by recognition of a target antigen, leading to high concentrations of the therapeutic cells at the disease site. Foremost among these are CAR-T cells, derived from a patient’s own T-cells and engineered to recognize tumor antigens and to kill via a cytolytic immune response. To date, five CAR-T cell therapies have been approved for treatment of B-cell cancers4. Despite these breakthroughs, cellular therapies have significant limitations and lack efficacy in most other cancers, including solid tumors5,6. Even in the context of B-cell malignancies, CAR-T cells cannot recognize antigen-negative cells, leading to incomplete therapeutic responses or later relapse7–9. Moreover, the immunologic functions of CAR-T cells can be suppressed by a variety of factors within the tumor microenvironment10, resulting in dysfunctional or ‘exhausted’ T cells11. Finally, CAR-T cell treatment can result in life-threatening toxicities arising from the immune response itself12.

To address these limitations, new generations of CAR-T cells with enhanced capabilities are being developed13,14, such as ‘armored’ CAR-T cells engineered to release localized doses of therapeutic cytokines, immunostimulatory ligands, or antibody fragments15–19. However, an approach that has not yet been explored is the development of CAR-T cells that can generate an orthogonally acting small-molecule drug locally at the disease site. This provides an attractive means to address the cancer resistance mechanisms described above, because a small-molecule drug with orthogonal anticancer activity would kill antigen-negative tumor cells, would not be hindered by the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment or T-cell exhaustion, could diffuse readily into the tumor mass providing broader efficacy beyond B-cell neoplasms, and may permit dose-sparing of the CAR-T cells to reduce the risk of toxicity arising from the immune response20. Further, local generation of the small-molecule drug at the tumor site would also reduce toxicity associated with systemic administration of the drug. While other approaches have been developed for antigen-targeted drug delivery, such as antibody–drug conjugates (ADC) and antibody-directed enzyme–prodrug therapy (ADEPT)21,22, the cell-based system envisioned here provides synergy with the CAR-T cell immune functions and also enables far higher levels of drug amplification, as the cells undergo logarithmic expansion at the disease site and each cell can, in turn, express thousands of copies of the enzymes that, in turn, generate the active drug catalytically. Bacterial delivery vectors for prodrug-activating enzymes have also advanced to the clinic, but lacked tumor antigen targeting and required intratumoral injection23.

Herein, we report the first demonstrations of this concept with SEAKER (Synthetic Enzyme-Armed KillER) cells, CAR-T cells engineered to activate systemically-administered, inactive prodrugs locally at tumor sites, resulting in enhanced anticancer activity in vitro and in vivo. The small-molecule drug provides activity against antigen-negative cells, is still generated by exhausted T-cells, extends efficacy to a solid-tumor model, and allows lower doses of the CAR-T cells to be used. We demonstrate the modularity and scope of this platform in SEAKER systems comprising two different activating enzymes and three classes of small-molecule drugs.

Results

A wide range of enzymes and prodrugs can be considered for use in the SEAKER platform toward various therapeutic applications22. To demonstrate the feasibility and modularity of this approach, we developed two SEAKER systems that express different hydrolytic enzymes that can activate appropriately masked prodrugs, based on Pseudomonas sp. carboxypeptidase G2 (CPG2), which hydrolyzes C-terminal glutamate masking groups24, and Enterobacter cloacae β-lactamase (β-Lac), which triggers cleavage of cephalosporin masking groups by hydrolysis of the β-lactam25 (Fig. 1A). We selected these two enzymes to facilitate this first implementation of the SEAKER concept as they are well-characterized, having both been used previously in ADEPT systems. Notably, CPG2 constructs have advanced to human clinical trials in that context22.

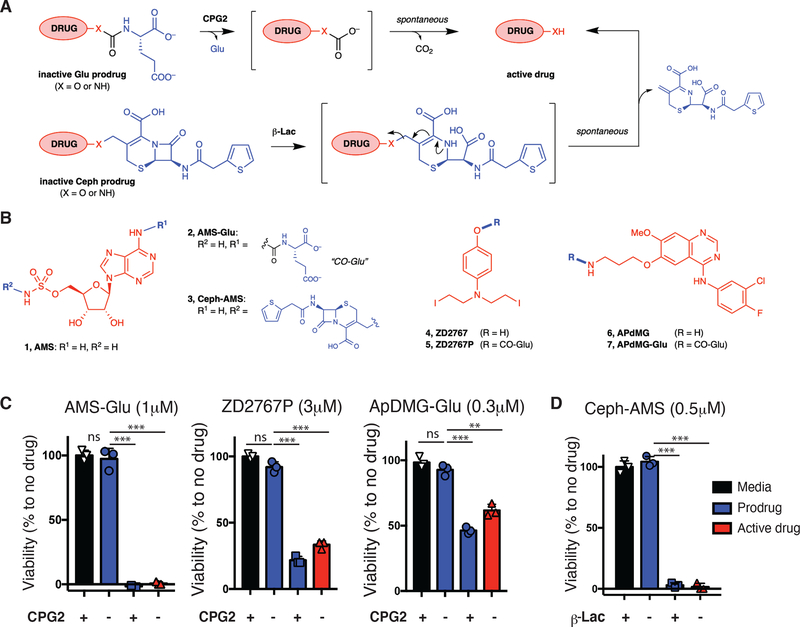

Figure 1. Modular prodrug designs for use with SEAKER cells.

(a) Glutamate-masked prodrugs can be cleaved with Pseudomonas sp. CPG2 to form a carbonic acid intermediate, followed by spontaneous decomposition of the linker to form the active drug. Cephalothin-masked prodrugs can be cleaved by Enterobacter cloacae β-Lac to form a hydrolyzed intermediate, followed by spontaneous elimination of the cephalothin byproduct to form the active drug. Drugs are shown in red, masks in blue, linkers in gray. (b) Structures of cytotoxic natural product AMS (1), glutamate-masked prodrug AMS-Glu (2), and cephalothin-masked prodrug Ceph-AMS (3); nitrogen mustard ZD2767 (4) and glutamate-masked prodrug ZD2767P (5); and targeted kinase inhibitor APdMG (6) and glutamate-masked prodrug APdMG-Glu (7). (AMS = adenosine-5´-O-monosulfamate or 5´-O-sulfamoyladenosine; APdMG = 7-O-aminopropyl-7-O-des[morpholinopropyl]gefitinib). (c) Cytotoxicity of prodrug AMS-Glu (2: 1 μM), ZD2767P (5: 3 μM), APdMG-Glu (7: 0.3 μM) with or without recombinant CPG2 (250 ng/mL), or of the parent drug AMS (1), ZD2767 (4), APdMG (6), to SET2 cells (48 h, CellTitre-Glo assay). (d) Cytotoxicity of prodrug Ceph-AMS (3: 0.5 μM), with or without recombinant β-Lac (10 ng/mL), or of the parent drug AMS (1: 0.5 μM) to SET2 cells (48 h, CellTitre-Glo assay). (For c,d: mean ± s.d. of n = 3 technical replicates/samples; Student’s two-tailed t-test: ns = not significant, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001; representative of 2 or more experiments.)

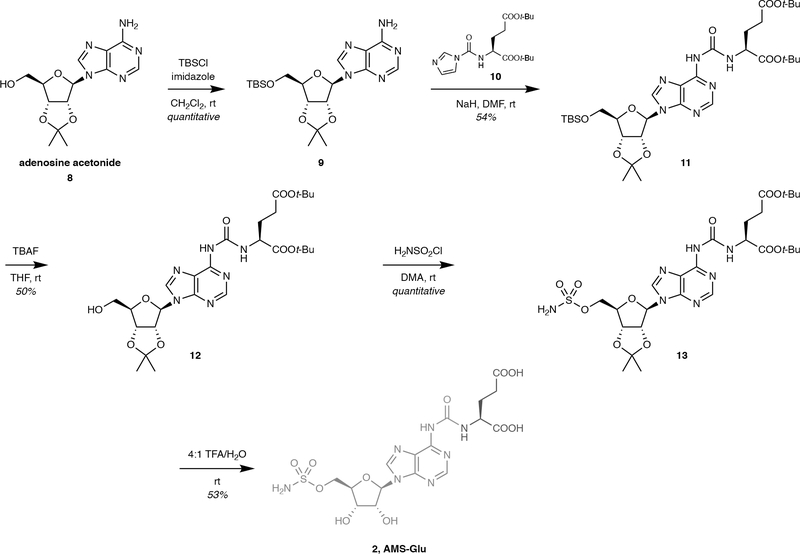

Design, Synthesis, and Cytotoxicity of Prodrugs

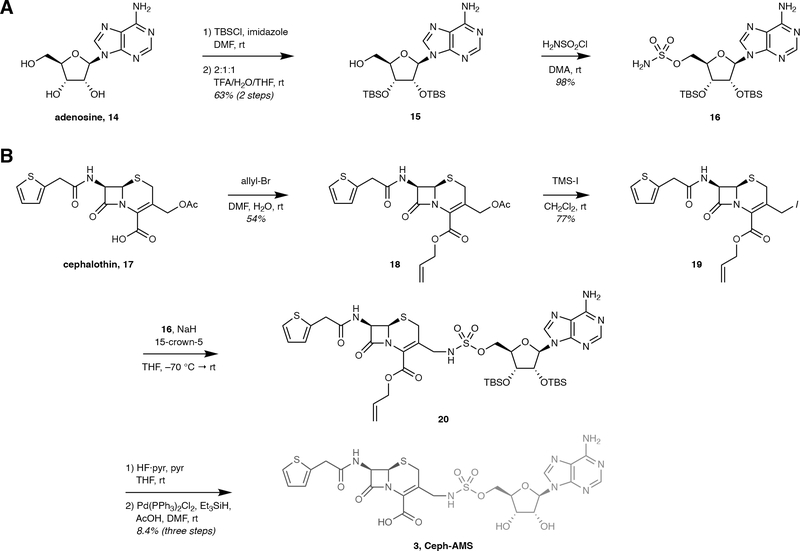

We designed four prodrugs for initial evaluation, using two different masking groups for cleavage by CPG2 or β-Lac, and representing three different chemotypes and mechanisms of action (Fig. 1B). 5´-O-Sulfamoyladenosine (AMS, 1) is a highly cytotoxic natural product26,27 with a mean GI50 of 1.77 nM in the NCI-60 Human Tumor Cell Lines Screen (NSC 133114). For use with CPG2 systems, the prodrug AMS-Glu (2) was designed with a glutamate masking group at the adenine 6-amino group of AMS, and synthesized in five steps from adenosine 2´,3´-O-acetonide (Extended Data Fig. 1) (See Supplementary Note for complete details). For β-Lac systems, the prodrug Ceph-AMS (3) was designed with a cephalothin masking group linked to the sulfamate nitrogen of AMS, and synthesized in seven steps from adenosine (Extended Data Fig. 2). The nitrogen mustard ZD2767 (4) has been masked as a glutamate prodrug ZD2767P (5) that has advanced to human clinical trials in ADEPT28, and was synthesized as previously described29. The parent drug 4 was synthesized in four steps from O-benzyl-4-aminophenol (Suppl. Fig. 1). Finally, APdMG (6, 7-O-aminopropyl-7-O-des[morpholinopropyl]gefitinib), an analogue of the targeted EGFR kinase inhibitor gefitinib, has been used in nanoparticle–drug conjugates30, and the glutamate-masked prodrug APdMG-Glu (7) was synthesized in two steps from the known parent drug30 (Suppl. Fig. 2).

We determined IC50 values for each prodrug–drug pair against a panel of cancer cell lines and primary cells to calculate selectivity indices (SI) (Suppl. Table 1). SI ranged from ≈1 log to >3 logs, with AMS-Glu (2) having the highest selectivities (556-fold median). All four prodrugs were deemed suitable for further evaluation.

Activation of Prodrugs by Recombinant Enzymes

We first investigated whether these prodrugs would be accepted as substrates by the corresponding enzymes. Cleavage of the glutamate-masked prodrugs AMS-Glu (2), ZD2767P (5), and APdMG-Glu (7) by recombinant, purified CPG2 (Suppl. Fig. 3A) was evaluated using a glutamate release assay (Amplex Red), and all three prodrugs were accepted as substrates (Suppl. Fig. 3B). Cleavage of the cephalosporin-masked prodrug Ceph-AMS (3) was assessed using a recombinant, purified mutant of β-Lac reported to have reduced immunogenicity31 (Suppl. Fig 3C), and the prodrug was successfully converted to the parent drug AMS (1) (LC-MS/MS assay). Enzyme kinetic parameters were then determined using SPE-TOF-MS (RapidFire solid-phase extraction/time-of-flight mass spectrometry) assays (Suppl. Table 2).

Next, we tested whether the recombinant, purified enzymes would activate the cytotoxicity of the corresponding prodrugs against a SET2 leukemia cell line. The glutamate-masked prodrugs AMS-Glu (2), ZD2767P (5), and APdMG-Glu (7) all exhibited cytotoxicity in the presence of CPG2 comparable to that of the corresponding parent drugs, but were non-toxic alone (Fig. 1C). Moreover, AMS-Glu (2) was non-toxic to LNCaP prostate cancer cells that express human glutamate carboxypeptidase II (PSMA, prostate-specific membrane antigen) (Suppl. Fig. 4), consistent with stability of the glutamate mask to this endogenous enzyme. The cephalosporin-masked prodrug Ceph-AMS (3) also exhibited analogous cytotoxicity to SET2 cells in the presence of β-Lac (Fig. 1D). Based on their potent cytotoxicity and high SI (Suppl. Table 1), we selected AMS-Glu (2) and Ceph-AMS (3) for further investigations.

Activation of Prodrugs by Enzyme-Expressing Cells

We next sought to determine whether the AMS-Glu (2) and Ceph-AMS (3) prodrugs could be activated by mammalian cells expressing CPG2 or β-Lac, respectively. This required that these bacterial enzymes be expressed by the mammalian cells in active form and without harming the producing cells. Our initial efforts focused on AMS-Glu (2) and CPG2, and we designed both secreted (CPG2-sec) and membrane-anchored (CPG2-tm) forms of the enzyme to compare their effectiveness. We anticipated that the secreted form would provide higher local enzyme concentrations, but also that enzyme diffusion in vivo might result in off-tumor toxicity. In contrast, the membrane-anchored form could provide enzyme activity more tightly localized to the producing cells, but its expression and activity might be hindered by proximity to the lipid bilayer or other membrane proteins.

Initial experiments were carried out in HEK293T cells by retroviral transduction with the CPG2 gene cassettes (Fig. 2A). The eukaryote-optimized CPG2 construct included two point mutations to prevent N-linked glycosylation32. CPG2-sec included an N-terminal CD8 signal peptide to route the enzyme through the secretory system, and a C-terminal CD8 tail that was found empirically to improve secretion. CPG2-tm also included the CD8 transmembrane domain to anchor the enzyme to the membrane. Both enzymes were expressed effectively, with only CPG2-sec detected in the cell supernatant fluid (Suppl. Fig. 5).

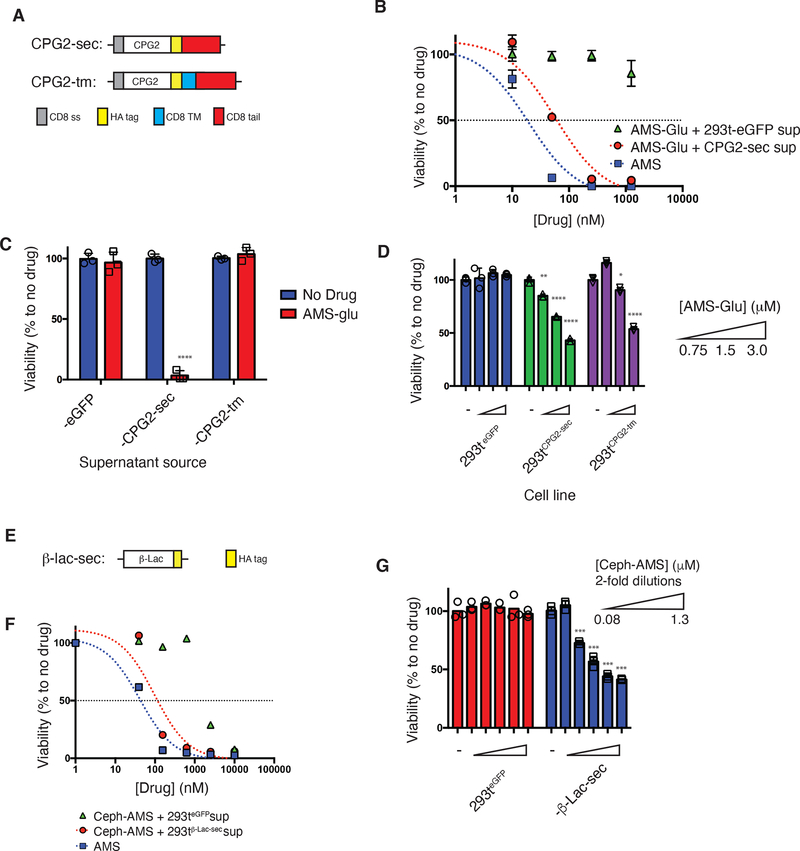

Figure 2. In vitro validation of prodrug activation by CPG2- and β-Lac-expressing HEK293T cells.

(a) CPG2 gene cassettes generated for eukaryotic expression: CPG2-sec (secreted), CPG2-tm (membrane-anchored). CD8 ss = CD8 signal peptide (gray), CPG2 = native CPG2 gene excluding endogenous signal peptide (aa1–22) (white), HA tag = hemagglutinin epitope tag (yellow), CD8 TM = CD8 transmembrane domain (blue), CD8 tail = CD8 cytosolic tail (red). (b) Trans-cytotoxicity of supernatant fluids from HEK293T-CPG2-sec cells (red circles) or control cells (green triangles) with increasing concentrations of prodrug AMS-Glu (2), or of parent drug AMS (1) (blue squares) against SET2 target cells (48 h, CellTiter-Glo assay). (c) Trans-cytotoxicity of supernatant fluids from HEK293T-eGFP, -CPG2-sec, and -CPG2-tm cell lines with or without AMS-Glu (2: 5 μM) against SET2 target cells (48 h, CellTiter-Glo assay). (d) Cis-cytotoxicity of increasing concentrations of AMS-Glu (2) to HEK293T-eGFP, -CPG2-sec, and -CPG2-tm cell lines (96 h, CellTitre-Glo assay). (e) β-Lac-sec (secreted) gene cassette generated for eukaryotic expression: β-Lac = native β-Lac gene excluding endogenous signal peptide (aa1–20) (white), HA tag = hemagglutinin epitope tag (yellow). (f) Trans-cytotoxicity (against other cell lines) of supernatant fluids from HEK293T-β-Lac-sec cells (red circles) or control cells (green triangles) with increasing concentration of prodrug Ceph-AMS (3), or of parent drug AMS (1) (blue squares) against SET2 antigen-negative target cells (48 h, CellTiter-Glo). (g) Cis-cytotoxicity (self-killing) of increasing concentrations of Ceph-AMS (3) to HEK293T-eGFP and HEK293T-β-Lac-sec cell lines (48 h, CellTitre-Glo). (For b-d; f-g: mean ± s.d. of n = 3 biological replicates/samples; Student’s two-tailed t-test: *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001; representative of 2 or more experiments.)

We then tested the ability of the HEK293T-expressed CPG2 to activate cytotoxicity of the AMS-Glu (2) prodrug against SET2 leukemia cells. Supernatant fluid from cells expressing CPG2-sec, but not control cells expressing eGFP (enhanced green fluorescent protein), activated dose-dependent cytotoxicity of AMS-Glu (2) (CellTiter-Glo assay), with potency comparable to that of the parent drug AMS (1) (Fig. 2B). As expected, cytotoxicity was not activated by supernatant fluid from cells expressing CPG2-tm (Fig. 2C). AMS-Glu (7) also exhibited dose-dependent cytotoxicity in direct treatment of HEK293T cells expressing CPG2-sec or CPG2-tm, but not control cells (Fig. 2D). Taken together, these results indicate that both enzymes were expressed in active form, with CPG2-sec in the cell supernatant fluid while CPG2-tm remained cell-associated. Given the higher effectiveness of the secreted form in these studies, we elected to advance it further below, while membrane-anchored forms remain an option for future implementations.

For the Ceph-AMS (3) prodrug, we focused on the secreted form of β-Lac (β-Lac-sec) (Fig. 2E). β-Lac-sec lacking an endogenous signal peptide was found empirically to be secreted in active form when expressed in HEK293T cells (Suppl. Fig. 6). Supernatant fluid from these cells, but not control cells, activated potent, dose-dependent cytotoxicity of the prodrug Ceph-AMS (3) (Fig. 2F). The prodrug also exhibited dose-dependent cytotoxicity in direct treatment of HEK293T cells expressing β-Lac-sec, but not control cells (Fig. 2G). This provided a second enzyme–prodrug pair for further investigations.

Engineering of CPG2 and β-Lac SEAKER Cells

We next incorporated the enzymes into an established CAR-T cell platform to generate SEAKER cells33. The parent CAR cassette (19BBz) includes an anti-CD19 scFv (single-chain variable fragment) domain, a 4–1BB costimulatory domain, and a CD3 zeta chain (Fig. 3A). We engineered new constructs with secreted CPG2 or β-Lac positioned upstream of the CAR cassette, separated by a P2A self-cleaving peptide34.

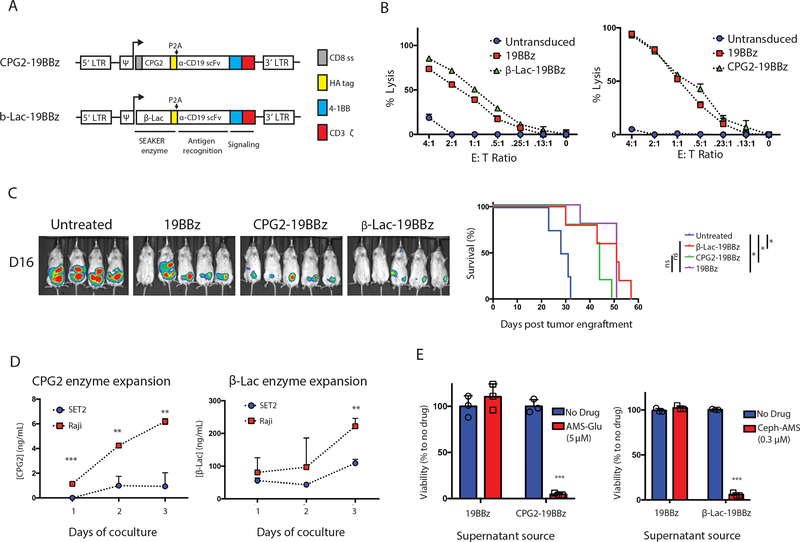

Figure 3. Construction and characterization of CPG2- and β-Lac-expressing SEAKER cells.

(a) SEAKER CAR constructs encoding secreted prodrug-activating enzymes: CPG2–19BBz (CPG2/α-CD19/4–1BB/CD3ζ) and β-Lac-19BBz (β-Lac/α-CD19/4–1BB/CD3ζ). LTR = long terminal repeat, Ψ = psi packaging element, CD8 ss = CD8 signal peptide (gray), HA tag = hemagglutinin epitope tag (yellow), P2A = 2A self cleaving peptide, α-CD19 scFv = CD19-specific single chain variable fragment, 4–1BB = 4–1BB costimulatory domain (blue), CD3ζ = CD3 zeta chain (red). (b) Cytolytic activity of standard 19BBz CAR-T cells, CPG2–19BBz SEAKER cells, and β-Lac-19BBz SEAKER cells against Raji (CD19+) target cells expressing firefly luciferase (18 h, bioluminescence assay; mean ± s.d. of n = 3 biological replicates/sample; representative data from 3 independent donors). (c) Antitumor efficacy of standard 19BBz CAR-T cells, CPG2–19BBz SEAKER cells, and β-Lac-19BBz SEAKER cells, without prodrugs, against Raji xenografts in NSG mice (day 16 post-tumor engraftment, bioluminescent imaging (left) and Kaplan–Meier curve (right). (Log-rank (Mantel–Cox) test: *p<0.05; untreated vs. β-Lac-19BBz: p = 0.003; untreated vs. CPG2–19BBz: p = 0.023; Untreated vs. 19BBz: p = 0.03. Experiment was performed once.) (d) SEAKER enzyme expression in cocultures of anti-CD19 SEAKERS with Raji (CD19+) or SET2 (CD19−) cells (CPG2: ELISA assay; β-Lac: nitrocefin cleavage UV assay; mean ± s.d. of n = 3 biological replicates/samples; Student’s two-tailed t-test: **p<0.01, ***p<0.001; representative of 3 experiments). (e) Trans-cytotoxicity of supernatant fluids from standard 19BBz CAR-T cells and SEAKER cells, with or without the corresponding prodrug, against SET2 target cells (48 h, CellTiter-Glo) (mean ± s.d. of n = 3 biological replicates/samples; Student’s two-tailed t-test: **p<0.01, ***p<0.001).

The CPG2–19BBz and β-Lac-19BBz constructs were first transduced in the Jurkat T-cell line for initial characterization. The secreted enzymes were detected in supernatant fluid from the transduced cells (Suppl. Fig. 7A), and the anti-CD19 CAR module remained functional, based on increased expression of the T cell activation marker CD69, observed in coculture experiments with target Raji (CD19+) Burkitt’s lymphoma cells, but not control SET2 (CD19−) leukemia cells (Suppl. Fig. 7B).

Next, primary human T cells from healthy donors were transduced with the CPG2–19BBz and β-Lac-19BBz constructs, and expression of the anti-CD19 CAR module was confirmed by flow cytometry (Suppl. Fig. 8A). The activity of the CAR module was confirmed in coculture experiments with Raji target cells, in which antigen-dependent cytotoxicity was observed for both the CPG2–19BBz and β-Lac-19BBz SEAKERs at levels comparable to the parent 19BBz CAR-T cells (Fig. 3B). Further, comparable levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines were detected in the supernatant fluids from both classes of SEAKER cells and the parent 19BBz CAR-T cells in cocultures with Raji target cells (Suppl. Fig. 8B). Both SEAKER cells also exhibited intrinsic in vivo antitumor efficacy comparable to that of the parent 19BBz CAR-T cells in a Raji xenograft model (Fig. 3C).

Activation of Prodrugs by SEAKER Cells

We then tested the ability of the SEAKER-secreted enzymes to activate cytotoxicity of the corresponding prodrugs. CPG2-sec and β-Lac-sec were detected in the supernatant fluids from CPG2–19BBz and β-Lac-19BBz SEAKER cells, respectively (Suppl. Fig. 8C). Coculturing the SEAKERs with Raji target cells, but not SET2 control cells, resulted in significant increases in enzyme concentrations (Fig. 3D). This is consistent with expected antigen-dependent expansion of the SEAKER cells, although general antigen-induced upregulation of enzyme expression is also possible. The activity of CPG2-sec was confirmed using a methotrexate cleavage assay35 (Suppl. Fig. 8D and 8E), while β-Lac-sec activity was assessed using a nitrocefin cleavage assay36 (Suppl. Fig. 8F). Moreover, the supernatant fluids from the SEAKER cells activated the cytotoxicity of the corresponding prodrugs against SET2 cells (Fig. 3E). Taken together, these data showed that both classes of SEAKER cells maintained their intrinsic CAR-T cell functions while also gaining the capability to activate corresponding small-molecule prodrugs.

Enhanced Activity of SEAKER–Prodrug Combinations in vitro

To test whether the SEAKER cells would exhibit enhanced antitumor activity in vitro when combined with the corresponding prodrugs, we carried out coculture experiments of CPG2–19BBz or β-Lac-19BBz SEAKER cells with Raji target cells. Addition of the corresponding AMS-Glu (2) or Ceph-AMS (3) prodrug, respectively, resulted in significantly enhanced cytotoxicity, which was especially pronounced at low effector-to-target (E:T) ratios (Fig. 4A and Fig. 4B). In contrast, no increase in cytotoxicity was observed when the prodrugs were combined with standard 19BBz CAR-T cells (Fig. 4C and Fig. 4D). Enhanced anticancer activity with Ceph-AMS (3) was also observed for the β-Lac-19BBz SEAKER cells against a SKOV-3 ovarian carcinoma solid-tumor cell line engineered to express CD19 (Suppl. Fig. 9).

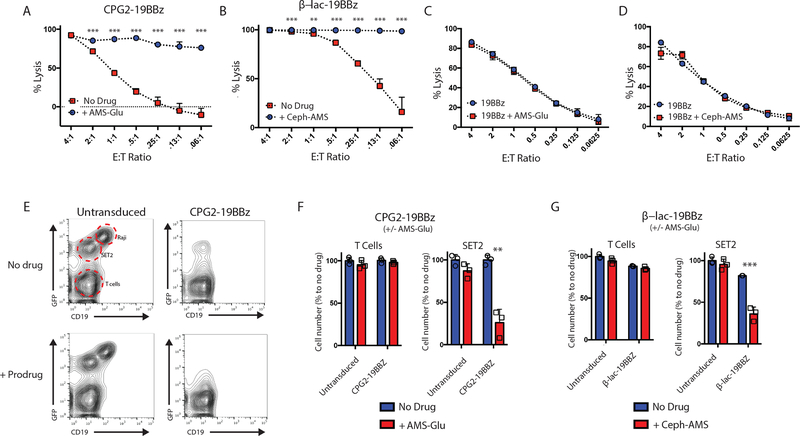

Figure 4. In vitro validation of prodrug activation by SEAKER cells and antigen-negative cell killing.

(a) Specific lysis by CPG2–19BBz SEAKER cells, with and without AMS-Glu (2: 20 μM), against Raji (CD19+) target cells expressing firefly luciferase (18–96 h, bioluminescence assay). (b) Specific lysis of β-Lac-19BBz SEAKER cells, with and without Ceph-AMS (3: 0.3 μM), as in panel a. Specific lysis by 19BBz CAR-T cells, with and without AMS-Glu (2) (c) or Ceph-AMS (3) (d) against Raji (CD19+) target cells expressing firefly luciferase (48 h, bioluminescence assay). (e) Flow cytometric analysis of trans-cytotoxicity of CPG2–19BBz SEAKER cells, with and without AMS-Glu (2: 20 μM), against Raji (CD19+) antigen-positive cells and SET2 (CD19−) antigen-negative cells engineered to express eGFP (representative data from 2 donors). (f) Quantitation of cell numbers from coculture experiments in panel e. (g) Quantitation of cell numbers from flow cytometric analysis of trans-cytotoxicity of β-Lac-19BBz SEAKER cells, with and without Ceph-AMS (3: 0.3 μM) against Raji (CD19+) antigen-positive cells and SET2 (CD19−) antigen-negative cells. (For a-g: mean ± s.d. of n = 3 biological replicates; Student’s two-tailed t-test: **p<0.01, ***p<0.001; representative data from 3 or more independent donors.)

Activity against Antigen-Negative Cancer Cells in vitro

We next investigated whether the SEAKER–prodrug combinations could also kill antigen-negative cancer cells in vitro in coculture experiments with both Raji target and SET2 control cells. In the case of the CPG2–19BBz SEAKER cells, treatment with the SEAKER cells alone eliminated the antigen-positive Raji cells, but not the antigen-negative SET2 cells (Fig. 4E and 4F). In contrast, addition of the AMS-Glu (2) prodrug resulted in elimination of both the Raji and SET2 cells, showing antigen-agnostic killing by the activated parent drug AMS (1). Notably, under these experimental conditions, the SEAKER cells survived, which may be due to the ≈1-log lower sensitivity to AMS (1) observed for 19BBz CAR-T cells compared to the Raji and SET2 cells (Suppl. Table 1). Similar results were also observed for the β-Lac-19BBz SEAKER cells with and without the corresponding Ceph-AMS (3) prodrug (Fig. 4G).

Enhanced Efficacy of SEAKER–Prodrug Combinations in vivo

Toward evaluating the antitumor efficacy of the SEAKER systems in mouse models, we analyzed the in vitro pharmacological properties and in vivo pharmacokinetics of AMS-Glu (2) and Ceph-AMS (3). Both prodrugs were stable in mouse and human plasma and liver microsomes, and exhibited acceptable plasma protein binding (Suppl. Table 3). In single-dose pharmacokinetic experiments in mice, both prodrugs provided plasma Cmax (maximum concentration) values well above the in vitro IC50 values at modest doses (10 and 5 mg/kg, ip, respectively), albeit with short plasma half-lives (t½ <1 h). Notably, AMS (1) (0.5 mg/kg, ip) also exhibited a very short plasma half-life in vivo (t½ <0.2 h). Pilot toxicology studies identified a maximum tolerated dose for AMS-Glu (2) of 50 mg/kg (ip, bid × 3 days). For Ceph-AMS (3), gross toxicity was observed at 50 mg/kg after the first day of dosing (ip, bid), so a lower 4 mg/kg dose was selected for use in efficacy studies below.

We also investigated the pharmacokinetics of CAR-T cells in mice to determine the optimal time for prodrug administration. We engineered 19BBz CAR-T cells to express a membrane-anchored form of Gaussia luciferase (gLuc-19BBz), which could be imaged in vivo by administration of a coelenterazine substrate37 (Suppl. Fig. 10A). These cells exhibited in vitro cytotoxicity comparable to that of standard 19BBz CAR-T cells against Raji target cells engineered to express eGFP and firefly luciferase (Raji-eGFP/fLuc) (Suppl. Fig. 10B). NSG (NOD/SCID/gamma) mice engrafted ip with Raji-eGFP/fLuc (CD19+) tumors were treated ip two days later with gLuc-19BBz CAR-T cells. Bioluminescent imaging revealed that CAR-T cell levels increased rapidly by ≈2 logs in the first day, then remained relatively steady for at least 33 days (Suppl. Fig. 10C), indicating that prodrug treatment could begin anytime after the first day following CAR-T cell administration.

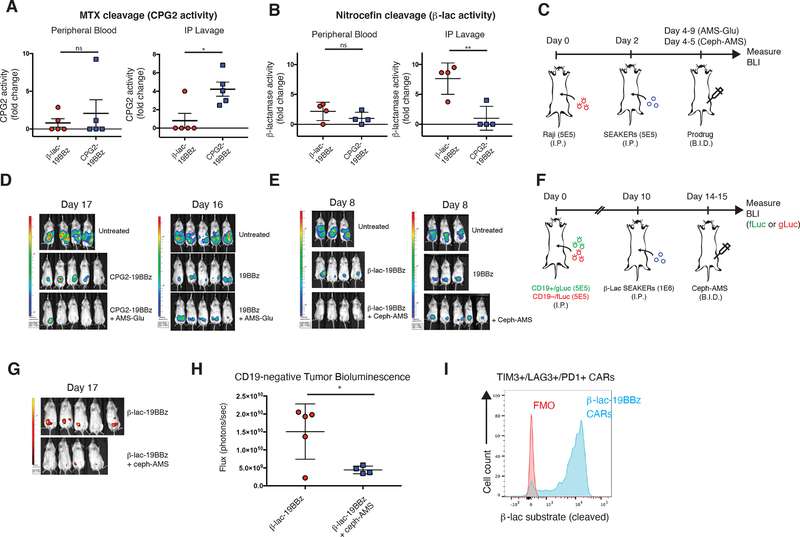

To assess whether the SEAKER cells could produce active enzymes in vivo, NSG mice were engrafted ip with Raji-eGFP/fLuc (CD19+) tumors, then treated two days later ip with CPG2–19BBz or β-Lac-19BBz SEAKER cells. Two days after SEAKER administration, samples from peritoneal lavage (ascites) and peripheral blood were assessed for enzyme activity. In both cases, the active enzymes were detected and, importantly, were restricted to the peritoneum and not detected in peripheral blood (Fig. 5A and 5B).

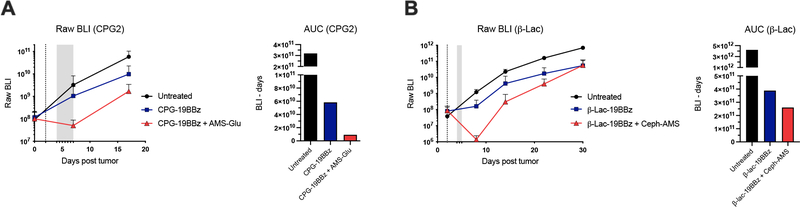

Figure 5. Enhanced in vivo efficacy of prodrug–SEAKER cell combinations in mouse intraperitoneal xenografts.

(a) CPG2 enzyme activity in peripheral blood (left) or peritoneal lavage (right) of Raji tumor-engrafted NSG mice treated with CPG2–19BBz SEAKER cells or β-Lac-19BBz SEAKER cells (negative control), based on methotrexate cleavage assay (fold-change; mean ± s.d. of n = 5 mice per group; Student’s two-tailed t-test: *p<0.05; representative data from 2 independent experiments). (b) β-Lac enzyme activity in peripheral blood (left) or peritoneal lavage (right) of Raji tumor-engrafted mice treated with CPG2–19BBz SEAKER cells (negative control) or β-Lac-19BBz SEAKER cells, based on nitrocefin cleavage assay (fold-change; mean ± s.d. of n = 4 mice per group; Student’s two-tailed t-test: **p<0.01; representative data from 2 independent experiments). (c) Experimental scheme to assess efficacy of SEAKER–prodrug combinations in intraperitoneal tumor model (AMS-Glu (2): 50 mg/kg, ip, bid, 12 doses total; Ceph-AMS (3): 4 mg/kg, ip, bid, 3 doses total). (d,e) Tumor bioluminescence was monitored over time (representative images shown; experiment in panel e was repeated with similar results) (see also Extended Data Fig. 3). (f) Experimental scheme to assess efficacy in a heterogeneous tumor model (2 × 106 total cells, 1:1 Nalm6-mCherry/gLuc (CD19+) and Nalm6-eGFP/fLuc (CD19−). (Ceph-AMS (3): 4 mg/kg, ip, bid, 3 doses total). (g,h) Antitumor efficacy against CD19− Nalm6 cancer cells (fLuc) engrafted within the heterogeneous tumor with CD19+ Nalm6 cancer cells (see also Extended Data Fig. 4), only in mice receiving β-Lac-19BBz SEAKER cells plus Ceph-AMS prodrug (3) (representative images shown on day 17 from 20-day study; one mouse in prodrug-treated group died between day 14 and day 17 and is omitted) (mean ± s.d. of n = 5 mice in SEAKER-treated group and n = 4 mice in SEAKER+prodrug-treated group; Student’s two-tailed t-test: *p<0.05; experiment was performed once). (i) Retention of β-Lac enzyme activity in β-Lac-19BBz SEAKER cells expressing T-cell exhaustion markers (TIM3, LAG3, PD1) after 26 days in Raji-engrafted mice (flow cytometry analysis: FMO = fluorescence minus one control; β-Lac substrate = CCF2-AM) (representative data shown for one of n = 4 mice; representative data from 2 independent experiments).

Finally, to determine if the SEAKER cells could activate the antitumor activity of the prodrugs in vivo, mice engrafted ip with Raji-eGFP/fLuc (CD19+) tumors were treated two days later ip with CPG2–19BBz or β-Lac-19BBz SEAKER cells, at dose levels lower than necessary for full tumor clearance by immune cell cytolysis alone, followed two days after SEAKER administration by the corresponding prodrug AMS-Glu (2) or Ceph-AMS (3), respectively (Fig. 5C). Decreased tumor bioluminescence was observed in mice treated with both the SEAKER cells and corresponding prodrug, compared to SEAKER cells alone (Fig. 5D and 5E and Extended Data Fig. 3). This effect was not observed in mice treated with standard 19BBz CAR-T cells plus either prodrug, consistent with specific activation of the prodrugs by only the SEAKER cells. The parent drug AMS (1) could not be used as a control because it is highly toxic (single-dose LD50 < 0.4 mg/kg, ip, Ha/ICR mice26), and systemic administration at these 10–100-fold higher dose levels would be lethal and unethical. Importantly, we did not observe overt systemic toxicity in these experiments.

Efficacy against Antigen-Negative Cancer Cells in vivo

To test whether the SEAKER–prodrug combination would have efficacy against antigen-negative cells in the context of a heterogeneous tumor in vivo, much like that encountered in a human cancer patient, we used a mixed tumor model comprised of Nalm6 (CD19+) leukemia cells engineered to express mCherry and Gaussia luciferase (Nalm6-mCherry/gLuc [CD19+]) and Nalm6 cells with the CD19 antigen knocked out by CRISPR-Cas9 deletion and engineered to express eGFP and firefly luciferase (Nalm6-eGFP/fLuc [CD19−]). NSG mice were engrafted with a 1:1 mixture of these cells, treated 10 days later ip with β-Lac-19BBz SEAKER cells, then treated 2 days later with the Ceph-AMS (3) prodrug (Fig. 5F). Significant killing of the antigen-negative cells was observed in mice treated with both the SEAKER cells and prodrug, but not the SEAKER cells alone (Fig. 5G and 5H and Extended Data Fig. 4A and 4B). Again, overt systemic toxicity was not observed in these experiments.

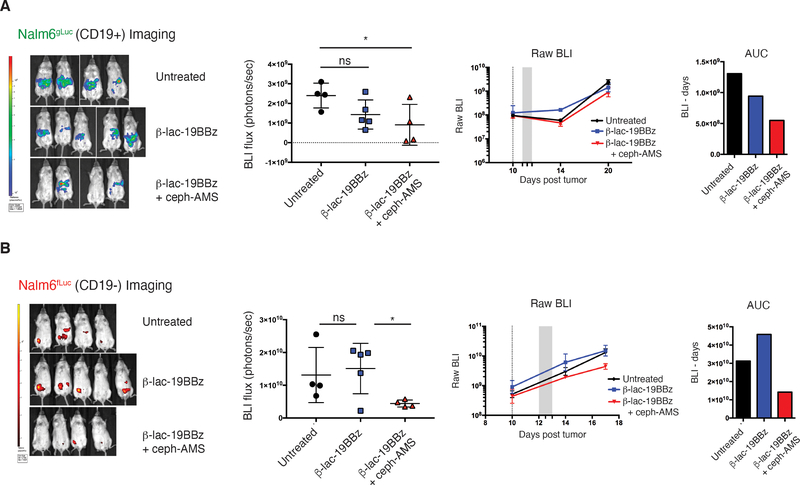

SEAKER Enzyme Activity Persistence after T-Cell Exhaustion

One cause of potential failure of CAR-T cells is exhaustion of their immune cytotoxic functions over time due to chronic antigen stimulation. We examined whether SEAKER cells that have become exhausted would maintain expression and activity of a prodrug activating enzyme. NSG mice were engrafted ip with Raji-eGFP/fLuc tumors, then treated 2 days later ip with β-Lac-19BBz SEAKER cells. SEAKER cells extracted from the mice 26 days later displayed the exhaustion markers TIM3, LAG3, and PD1, but >90% of those cells continued to exhibit β-Lac enzyme activity (Fig. 5I and Suppl. Fig. 11). Moreover, in mice that had also been treated with Ceph-AMS (3) on days 4–5 post tumor engraftment, administration of a second round of prodrug beginning on day 22 led to a >1-log decrease in tumor burden (Extended Data Fig. 5A and 5B). SEAKER cells extracted from these mice by peritoneal lavage on day 30 post tumor engraftment continued to exhibit β-Lac enzyme activity, indicating their survival and continued prodrug-activating capability even after two courses of prodrug treatment (Extended Data Fig. 5C).

SEAKER–Prodrug Efficacy in Subcutaneous Tumor Models

We next investigated whether the SEAKER–prodrug combinations would be efficacious in a subcutaneous tumor model. NSG mice were engrafted subcutaneously (sq) with Raji-eGFP/fLuc (CD19+) tumor cells and pharmacokinetic studies were again carried out using gLuc-19BBz CAR-T cells37, injected iv 7 days after tumor engraftment. Bioluminescent imaging indicated that the CAR-T cells expressing membrane-anchored Gaussia luciferase aggregated at the tumor with peak concentrations at 9 days after administration (Suppl Fig. 12).

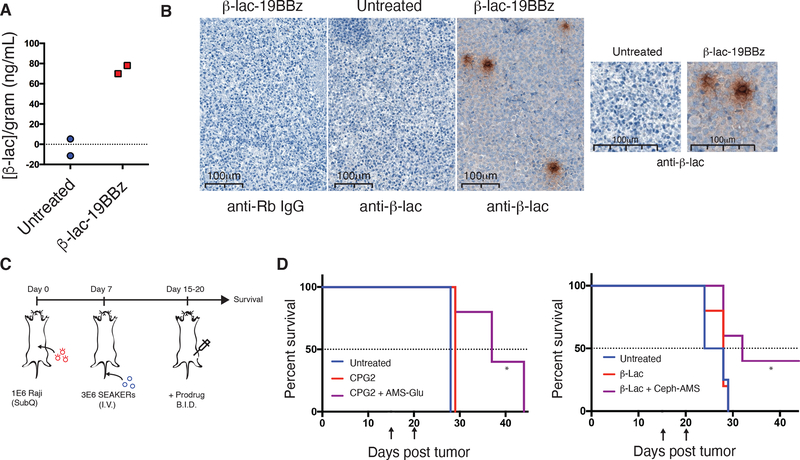

In a key demonstration of the SEAKER concept, we showed that SEAKER cells produced active enzyme in vivo at the tumor site. NSG mice were engrafted sq with Raji-eGFP/fLuc (CD19+) tumors as above, then treated 7 days later iv with β-Lac-19BBz SEAKER cells. Tumors were resected 9 days after SEAKER administration and β-Lac enzyme activity was detected in the tumor (Fig. 6A). In contrast, β-Lac enzyme activity was not detected in the spleen, a natural clearing site of CAR-T cells, consistent with localized distribution in the tumor (Suppl. Fig. 13). Moreover, immunohistochemistry staining of the resected tumors using an anti-β-Lac antibody revealed loci of concentrated staining, with additional diffuse staining throughout the tumor, consistent with diffusion of the enzyme away from the SEAKER cells and throughout the tumor (Fig. 6B).

Figure 6. Enhanced in vivo efficacy of Ceph-AMS–β-Lac-SEAKER cell combinations in mouse subcutaneous xenografts.

(a) Nitrocefin cleavage-based quantitation of tumor β-Lac concentration in a subcutaneous Raji tumor from a mouse treated with 3 × 106 β-Lac-19BBz SEAKER cells (IV) (representative data from two of n = 5 mice per group in 3 independent experiments). (b) anti-β-Lac immunohistochemistry imaging of subcutaneous Raji tumors extracted on day 15 from mice that were untreated, or received 3 × 106 β-Lac-19BBz SEAKER cells (IV) (top panels – left: isotype control; center: untreated mouse stained with anti-β-Lac antibody; right: β-Lac-19BBz-treated mouse stained with anti-β-Lac antibody). Increased magnification highlights diffuse β-Lac staining throughout the tumor environment (bottom panels) (representative data shown from one of the 3 remaining mice from the n = 5 group used in panel a). (c) Experimental scheme to assess therapeutic efficacy of SEAKER–prodrug combinations in a subcutaneous solid tumor model. Raji tumor cells were engrafted sq on day 0 followed by SEAKER cells iv on day 7. The corresponding prodrug was administered beginning on day 15 (AMS-Glu (2): 50 mg/kg, ip, bid, days 15–20, 12 doses total, or Ceph-AMS (3): 4 mg/kg, ip, bid every other day, days 15, 17, 19, 6 doses total) and mice were monitored for survival. (d) Survival analysis of mice engrafted with subcutaneous Raji tumors receiving subtherapeutic doses of CPG2–19BBz SEAKER cells plus AMS-Glu (2) (left panel), or β-Lac-19BBz SEAKER cells plus Ceph-AMS (3) (right panel). (Arrows denote beginning and end of the prodrug administration period; n = 5 mice/group; log-rank (Mantel–Cox) test: *p<0.05; CPG2–19BBz vs. CPG2–19BBz + AMS-Glu: p = 0.023; β-Lac-19BBz vs. β-Lac-19BBz + Ceph-AMS: p = 0.048; experiment was repeated with similar results).

We then evaluated whether the SEAKER–prodrug combinations exhibited enhanced antitumor efficacy in this model. NSG mice were engrafted sq with Raji-eGFP/fLuc (CD19+) tumors, then treated 7 days later iv with CPG2 or β-Lac SEAKER cells as above (Fig. 6C). Beginning 8 days after SEAKER administration, the mice were treated with the corresponding prodrug, AMS-Glu (2) or Ceph-AMS (3), respectively. Mice treated with both the SEAKER cells and corresponding prodrug showed significantly extended survival compared to those treated with the SEAKER cells alone and untreated control mice (Fig. 6D). We did not observe overt systemic toxicity in these experiments (Suppl. Fig. 14). Attempts to quantitate the concentration of the activated drug AMS (1) in tumors were complicated by the high variability at any single timepoint, which is influenced by differences in tumor size, SEAKER cell localization, prodrug concentration, enzymatic activation of the prodrug, and clearance of the activated drug, in contrast to antitumor efficacy, which represents integration of drug concentration across the entire experiment. Notably, the prodrugs did not significantly extend survival of mice treated with standard 19BBz CAR-T cells (Suppl. Fig. 15), again consistent with specific activation of the prodrugs by only the SEAKER cells.

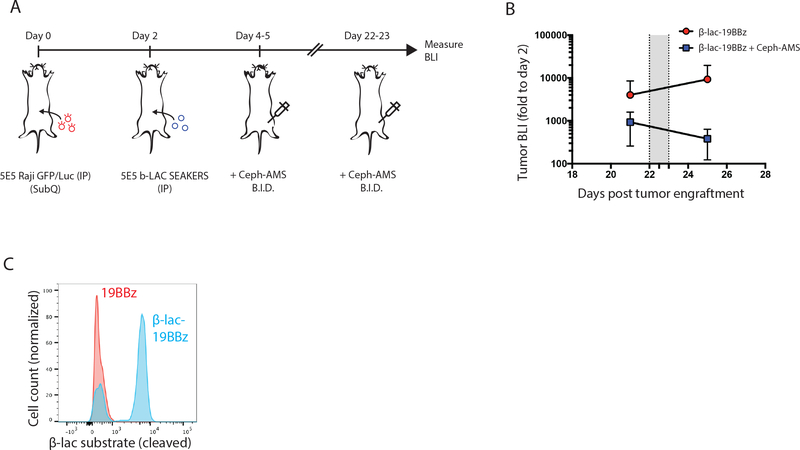

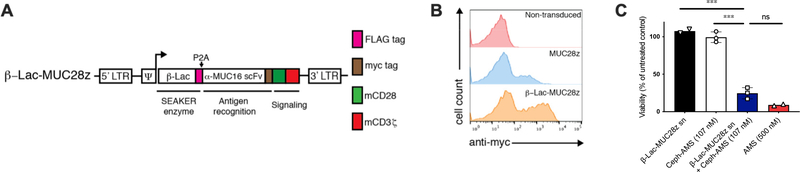

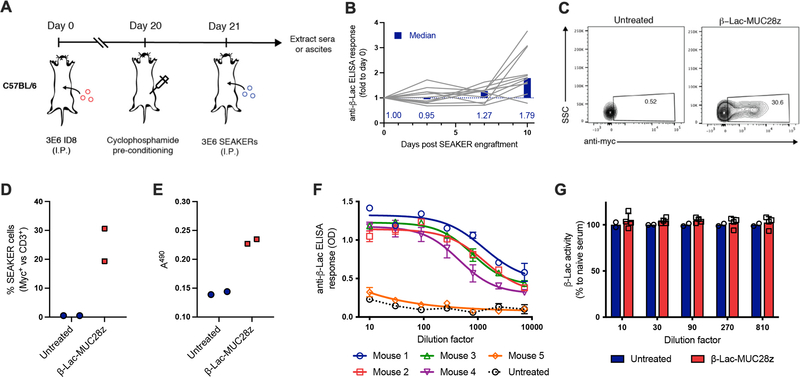

Immunogenicity of SEAKER Cells in a Syngeneic Mouse Model

To investigate whether an intact immune system would neutralize the bacterial enzymes expressed by the SEAKER cells, we used a syngeneic mouse tumor model16. We constructed murine SEAKER cells expressing β-Lac and a CAR comprising an anti-MUC16 scFv domain, a mouse CD28 costimulatory domain, and a mouse CD3 zeta chain (β-Lac-MUC28z), from primary murine T cells (Extended Data Fig. 6A and 6B). The anti-MUC16 CAR was used instead of the anti-CD19 CAR used above to avoid depletion of healthy B cells that would confound a potential antibody response to the bacterial enzyme. We confirmed that supernatant fluid from these cells activated the cytotoxicity of Ceph-AMS (3) against mouse EL4 lymphoma tumor cells in vitro (Extended Data Fig. 6C). Next, immunocompetent C57BL/6 mice were engrafted ip with murine ID8 ovarian surface epithelial cells that express MUC16, then treated 21 days later ip with β-Lac-MUC28z SEAKER cells (Extended Data Fig. 7A). Mice were preconditioned with cyclophosphamide prior to SEAKER cell administration to facilitate engraftment, a regimen that is also used in the clinic. Sera collected from mice over 10 days were analyzed for IgG reactivity to recombinant β-Lac, revealing the development of anti-β-Lac antibodies in most of the mice (Extended Data Fig. 7B). Analysis of ascites showed that the murine SEAKER cells persisted in mice at least 7 days after administration (Extended Data Fig. 7C and 7D). Moreover, these samples retained full β-Lac enyzme activity (Extended Data Fig. 7E). We further demonstrated that anti-β-Lac-containing sera from SEAKER-treated mice (without preconditioning to provide a maximal immune response) did not inhibit the enzymatic activity of recombinant β-Lac in vitro (Extended Data Fig. 7F and 7G). Taken together, these results show that, in this syngeneic model, although SEAKER cells are immunogenic as expected, the resulting immune response does not result in early clearance of the SEAKER cells nor in neutralization of β-Lac enzymatic activity ex vivo.

Discussion

The SEAKER cell platform established herein, provides a potential means to overcome some of the current limitations of CAR-T cells5, through targeted, local activation of small-molecule drugs with orthogonal activity. We have shown that SEAKER–prodrug combinations provide enhanced anticancer activity in vitro and in vivo, with the important added function of killing of antigen-negative cells in heterogeneous tumors. The SEAKER cells maintain prodrug-activating activity even after becoming immunologically exhausted. The secreted enzymes and activated drugs can diffuse throughout tumors, of potential benefit in solid tumors. Further, SEAKERs provide multiple layers of local drug amplification via cell proliferation, enzyme production, and catalytic prodrug activation, in contrast to other drug delivery systems such as ADCs and ADEPT.

We demonstrated this modularity of the SEAKER platform using three classes of small-molecule drugs with different mechanisms of action. Of course, a wide range of other drugs can be envisioned depending on intended therapeutic applications, including those outside of cancer, and many have been explored previously in the context of ADEPT22. Differences in enzyme kinetics and the relative sensitivity of the SEAKER cell and target cells to the activated drug will be important considerations in future applications. Other enzyme transformations can be also envisioned to avoid the use of large masking groups that dominate pharmacological properties.

We envisioned that secreted enzymes would provide higher levels of prodrug activation, while membrane-anchored forms could provide more tightly localized prodrug activation and potentially reduce off-tumor toxicity. In the mouse xenograft models herein, we did not observe appreciable off-tumor toxicity with the secreted enzymes. However, membrane-anchored variants may still be of interest if systemic toxicity proves limiting.

Potential immunogenicity of bacterial enzymes is an important consideration for future translation, as neutralizing antibodies may block their activity38. This may be addressed by using deimmunized forms of the enzymes31 that were developed subsequently to the initial ADEPT clinical trials39, through co-administration of immunosuppressants that do not interfere with T-cell functions40,41or by using human enzymes43–45. Notably, it is well established that CAR-T cells are, themselves immunogenic42, but this has not impeded their effective use in the clinic, as they act through a rapid period of tumor lysis that occurs before the humoral immune response is fully mounted. Further, many non-human enzymes are FDA approved, widely prescribed, and used safely38.

We used herein a well-established anti-CD19 CAR-T cell system that has been clinically validated46, but SEAKER cells can readily be targeted to other antigens to treat a variety of cancers, including solid tumors in which the diffusible small-molecule drug could be particularly valuable, as well as potentially other diseases requiring local delivery of a small-molecule drug that would otherwise cause dose-limiting toxicity if administered systemically. This general approach may also be extended to other cell-based therapeutic platforms, such as tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and synthetic TCR therapy47–49. The SEAKER platform remains antigen-dependent, and thus, like other such cellular therapies, may result in off-tumor toxicity based on the antigen selected and would not be effective against completely antigen-negative tumors. However, antigen-negative cell relapse from heterogeneous tumors is a major source of treatment failure with current CAR-T cell therapies, so SEAKER-prodrug combinations could reduce this relapse mechanism.

In conclusion, we have established a new cellular therapeutic platform of targeted ‘micropharmacies’ that integrates CAR T-cell immunotherapy with local activation of small-molecule prodrugs, exhibits enhanced antitumor activity in vitro and in vivo, and can overcome a variety of current obstacles in conventional CAR T-cell therapy. The platform provides a broadly applicable means to augment cellular therapeutics that may extend to other diseases.

Methods

Chemical synthesis

See Supplementary Note for synthetic methods and analytical data for all new compounds.

Recombinant proteins

CPG224 and β-Lac31 proteins were produced and purified by GenScript. Constructs contain C-terminal hemagglutinin (HA) and His6 epitope tags and were purified by nickel affinity chromatography.

Cloning and generation of retroviral vectors and cell lines

HEK293T cell lines were generated using retroviral transduction with the MMLV gamma retroviral vector pLGPW or pLHCX (gifts from Domenico Tortorella lab, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai). CAR-T and SEAKER vectors were generated by cloning into the SFG gamma-retroviral vector encoding CD19-directed CAR with human 4–1BB costimulatory element and CD3 zeta chain (SFG-19BBz)50 or, for the syngeneic mouse model, the vector encoding α-MUC-16 (4H11) CAR with murine CD28 costimulatory element and murine CD3 zeta chain (SFG-MUC28z)16. β-Lac and CPG2 were cloned upstream of the CAR constructs and separated by a P2A self-cleaving sequence. Standard molecular biology techniques and Gibson assembly were used to generate all constructs. Retroviral producer lines were generated with CaCl2 (Promega) to transiently transfect H29 cells with retroviral constructs encoding CARs or SEAKERs. Supernatant from the H29 cells was collected and used to transduce 293Glv9, PG13, or Phoenix-Eco stable packaging cells. Individual producers were subcloned and expanded.

Cell culture

Cells were maintained in RPMI supplemented with 10% FBS, 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 IU/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL nonessential amino acids, sodium pyruvate, N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N-2-ethane sulfonic acid (HEPES). Human T-cell media was supplemented with 100 IU/mL IL-2.

T cell isolation and modification

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated from healthy donors. PBMCs were activated with 50 ng/mL OKT-3 antibody (MACS) and 100 IU/mL IL-2 for two days prior to transduction and maintained in 100 IU/mL thereafter. Trandsuction was performed by centrifugation of activated T cells in media from retroviral producers at 2000× g at room temperature for 1 h on RetroNectin-coated plates (Takara Bio) for two consecutive days. Experiments were performed in compliance with all relevant ethical regulations and in accordance with MSK IRB Protocol 00009377.

Mouse T cells were engineered as previously described16. Briefly, T-cells were isolated from spleens of naive mice by mechanical disruption using a 100 μm cell strainer. Splenocytes were collected and red blood cells were lysed with ACK (ammonium-chloride-potassium) lysing buffer (ThermoFisher A1049201). Splenocytes were activated overnight with CD3/CD28 Dynabeads (Life Technologies) and 50 IU/mL human IL-2. Activated T cells were transduced by centrifugation with retroviral supernatant from transduced Phoenix-Eco cells on RetroNectin-coated plates (TakaraBio) for 2 consecutive days.

Flow cytometry

Transduction efficiency was determined by flow cytometry using an Alexa647-labeled anti-idiotype antibody directed to the CD19-targeted CAR (mAb clone #19E3 – generated at MSK Antibody and Bioresource Core Facility) or a phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated rabbit antibody directed to the myc epitope tag in the MUC16-targeted CAR (Cell Signaling Technology 64025S). The following additional commerical antibodies were used in flow cytometry experiments where specified: Alexa647-anti-HA (ThermoFisher 26183-A647, clone 26187), APC-CD19 (BD 555415), PE-CD69 (BioLegend 310906), APC/Cy70-CD3 (BioLegend UCHT1). All samples were washed and stained in FACS buffer (2% FBS in PBS) at 4 °C. Data were collected using a Guava EasyCyte HT flow cytometer (Millipore) or an LSR Fortessa (BD). Flow Jo software was used for all data analyses.

Immunoprecipitation and western blot analysis

Anti-HA agarose beads (ThermoFisher 26181) were incubated with cell supernatant or mouse ascites for 2 h at 4 °C on a nutator. The beads were washed 2x with cold PBS, and Laemmli sample buffer (BioRad 161–0747) with or without β-mercaptoethanol (BME) was added. Protein samples (immunoprecipitate or total cell lysates) were homogenized and heated 3x for 3 min at 95 °C and resolved by SDS-PAGE. Gels were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes and blotted for respective antibodies in TBST (ThermoFisher 28360). Detection of antibody was achieved with Pierce ECL femto western substrate (ThermoFisher 34095). The following antibodies were used for immunoblot: mouse IgG HRP-conjugated antibody (R&D systems HAF007), rabbit IgG HRP-conjugated antibody (R&D systems HAF008), anti-HA (Invitrogen 26183). Polyclonal anti-CPG2 and anti-β-Lac antibodies were raised in rabbits by inoculation with whole recombinant protein produced in E. coli and purified by nickel bead affinity chromatography (service performed by GenScript).

ELISA analysis

Sandwich ELISAs were performed on 96-well Immulon HBX plates (ThermoFisher). A mouse IgG anti-HA antibody was used to capture protein (Invitrogen 26183) and a polyclonal mouse anti-rabbit HRP antibody was used as detection antibody (R&D systems HAF008). Protein was detected using TMB substrate (ThermoFisher 34028) and H2SO4 acid quench and read on a SpectraMax M2 plate reader (Molecular Devices). Data were analyzed with SoftMax Pro software.

CPG2 glutamate release assay

Recombinant CPG2 enzyme was incubated with glutamate prodrugs in CPG2 reaction buffer (1M Tris·HCl, 2 mM ZnCl2) for 2 h at 37 °C and the enzyme/prodrug mixture was combined 1:1 with Amplex Red™ Glutamate Oxidase Assay mixture (ThermoFisher A12221). Following 30 min at 37 °C, fluorescent emission at 590 nm was measured on a SpectraMax M2 plate reader (Molecular Devices). Data were analyzed with SoftMax Pro software.

CPG2 methotrexate cleavage assay

Methotrexate (Accord Healthcare) was incubated at a final concentration of 450 μM with recombinant CPG2 enzyme, CAR-T cells, or cell supernatant and incubated at 37 °C for 16 h. Absorbance at 390 nm was recorded on a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific).

β-Lac nitrocefin cleavage assay

Cell supernatant, mouse ascites, or mouse blood was serially diluted (2-fold) and mixed 1:1 with 0.2 mM nitrocefin (abcam ab145625). Samples were incubated 1–16 h at room temperature and absorbance at 490 nm was read on a SpectraMax M2 plate reader (Molecular Devices). Data were analyzed with SoftMax Pro software.

Enzyme kinetic assays

Analysis of enzyme kinetics reported in Extended Data Table 2 was performed on an automated solid-phase extraction RapidFire-MS, equipped with a 6520 TOF (time-of-flight) accurate mass spectrometer detection system (Agilent Technologies). The 6520 TOF-MS has a theoretical limit of high-femtogram sensitivity and up to five orders of magnitude dynamic range. This instrument also includes a Zymark Twister robotic arm that handles microtiter plates, and a solid-phase extraction (SPE) purification system. Samples were aspirated from each well of a 384-well microtiter plate and injected onto a C18 SPE column extraction cartridge (Catalog Number: G9205A) for detection of APdMG-Glu (S4), Ceph-AMS (3) and nitrocefin, or a graphitic carbon SPE cartridge (Catalog Number: G9206A) for detection of AMS (1) and methotrexate. Columns were washed and eluted with solvent system A or B (below) onto the electrospray MS, where the mass spectra were collected in positive mode (Ceph-AMS, APdMG-Glu, nitrocefin) or negative mode (AMS, methotrexate). The RapidFire sipper was washed between sample injections using alkaline/organic and aqueous alkaline solvents. RapidFire-MS screening data were processed and analyzed using Agilent MassHunter Software.

Solvent system A (for detection of AMS, APdMG-Glu, Ceph-AMS, and nitrocefin): washed with aqueous alkaline buffer (10 mM ammonium acetate, pH 10) and eluted using an alkaline/organic solvent (50% methanol + 50% isopropanol in 2 mM ammonium acetate and 0.1% formic acid).

Solvent system B (for detection of methotrexate): washed with aqueous alkaline buffer (5 mM ammonium acetate, pH 10) and eluted using an alkaline/organic solvent (50% water + 25% acetonitrile + 25% acetone in 5 mM ammonium acetate, pH 10).

Analyte, reaction time, aliquot frequency, exact mass, m/z detected: AMS, 10 min, 1 min, 346.0696, 345.0659 [M+H]+; ApDMG-Glu, 180 sec, 20 sec, 698.1903, 699.2136 [M+H]+; methotrexate, 180 sec, 20 sec, 454.1713, 453.168 [M+H]+; Ceph-AMS, 90 min, 10 min, 682.0934, 683.1068 [M+H]+; nitrocefin, 270 sec, 30 sec, 516.4990, 539.0262 [M+Na]+.

For AMS-Glu (2), CPG2 (752 nM) was incubated with various concentrations of AMS-Glu (2) (25–200 μM) at 22 °C in PBS in a glass vial. Aliquots were removed at various time points (up to 10 min) and added to a 384-well plate containing 2 volumes of 0.1% formic acid to stop the reaction. AMS (1) product formation was measured by RapidFire-MS. The resulting data were fit to the Michaelis–Menten equation to determine the Michaelis constants.

For APdMG-Glu (7), CPG2 (752 nM) was incubated with various concentrations of APdMG-Glu (7) (12.5–100 μM) at 22 °C in PBS in a glass vial. Aliquots were removed at various time points (up to 3 min) and added to a 384-well plate containing 6 volumes of 0.1% formic acid to stop the reaction. APdMG-Glu (7 substrate depletion was measured by RapidFire-MS. The resulting data were fit to the Michaelis–Menten equation to determine the Michaelis constants.

For methotrexate, CPG2 (37.6 nM) was incubated with various concentrations of methotrexate (25–200 μM) at 22 °C in PBS in a glass vial. Aliquots were removed at various time points (up to 3 min) and added to a 384-well plate containing 2 volumes of 0.1% formic acid to stop the reaction. Methotrexate substrate consumption was measured by RapidFire-MS. The resulting data were fit to the Michaelis–Menten equation to determine the Michaelis constants.

For Ceph-AMS (3) and nitrocefin, β-Lac (11.44 nM) was incubated with various concentrations of Ceph-AMS (3) or nitrocefin (25–200 μM) at 22 °C in PBS in a glass vial. Aliquots were removed at various time points (up to 90 min for Ceph-AMS or 4.5 min for nitrocefin) and added to a 384-well plate containing 2 volumes of 0.1% formic acid to stop the reaction. Substrate consumption was measured by RapidFire-MS. The resulting data were fit to the Michaelis–Menten equation to determine the Michaelis constants.

Cytotoxicity assays

Prodrug/drug IC50 and trans-cytotoxicity and cis-cytotoxicity assays with secreted enzymes were performed using CellTiter-Glo (Promega). Cells were analyzed in triplicate wells of a 96-well dish and equivalent volume of CellTiter-Glo reagent was added to each well. Following a 10-min incubation at room temperature, samples were transferred to White 96-well Optiplates (Perkin Elmer) and luminescence was measured on a SpectraMax M2 plate reader (Molecular Devices). Data were analyzed with SoftMax Pro software.

The cytotoxicity of CAR-T cells and SEAKER cells was determined by luciferase-based assays. Target cells (Raji and SKOV-3 cells expressing firefly luciferase and GFP (fLuc-GFP) were used as target cells. Effector and tumor target cells were cocultured in triplicate at the indicated E:T (effector-to-target) ratio using clear bottom, white 96-well assay plates (Corning 3903) with 5 × 104 target cells in a total volume of 200 μL. Target cells alone were plated at the same cell density to determine maximum luciferase activity. Cells were cocultured for 4–18 h, at which time D-luciferin substrate (Gold Biotech LUCK) was added at a final concentration of 0.5 μg/μL to each well. Emitted light was detected in a Wallac EnVision Multilabel reader (Perkin Elmer). Target lysis was determined as (1-(RLUsample)/(RLUmax))×100.

Mixed cell bystander toxicity assays were performed by incubating untransduced T cells or SEAKER cells with Raji and SET2 cells at 4:1:1 (CAR-T cells:Raji:SET2) ratio. Following 24 h of coculture, prodrug was added and cells were cultured for an additional 48 h prior to analysis by flow cytometry. Detection of GFP and anti-CD19 staining (APC-CD19 [BD 555415]) delineated Raji versus SET2 versus CAR-T cells. Cell count was measured by acquiring cells for 30 sec/well on a Guava EasyCyte flow cytometer and multiplying percentage of respective gates by total cells acquired.

gLuc-19BBz reporter CAR-T cell analysis in vitro

Assays measuring proliferation of gLuc-19BBz CAR-T cells were performed by measuring emitted light following cleavage of coelenterazine substrate (Prolume 3032). Cells were cocultured for 4–18 h, at which time coelenterazine was added at a final concentration of 2.5 μM to each well. Emitted light was detected in a Wallac EnVision Multilabel reader (Perkin Elmer).

Pharmacological assays and pharmacokinetic studies

In vitro pharmacological assays and mouse pharmacokinetic studies were carried out by Sai Life Sciences, Hyderabad, India, in compliance with all relevant ethical regulations and in accordance with IAEC protocols FB-18–022 and FB-19–033. Plasma protein binding studies were carried out by rapid equilibrium dialysis (ThermoFisher) using fresh plasma from NOD/SCID mice (ACTREC, Mumbai, India) or human drug-free volunteers (Dr. Bhonsle’s Lab, Mumbai, India) and LC-MS/MS analysis. Plasma stability studies were carried out in fresh plasma from NOD/SCID mice (ACTREC), or human drug-free volunteers (AJ Medical, Pune, India) by LC-MS/MS analysis. Microsomal stability studies were carried out in pooled liver microsomes from CD-1 mice (Gibco) or humans (BD Gentest) by LC-MS/MS analysis. Single-dose pharmacokinetic studies were carried out by ip injection of NOD/SCID mice (n = 9) and LC-MS/MS analysis of plasma samples at 0.08, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, and 24 h (n = 3 per timepoint). Pharmacokinetic parameters were calculated using the non-compartmental analysis tool of Phoenix WinNonlin®.

Mouse efficacy studies

All experiments were performed in compliance with all relevant ethical regulations and in accordance with MSK IACUC protocol 96–11-044.

Intraperitoneal model:

NSG mice (NOD.Cg-Prkdcscid Il2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ, 7–13 weeks old, male and female) were obtained from Jackson Laboratory. Mice were engrafted on Day 0 with 0.5 × 106 Raji-eGFP/fLuc tumor cells (intraperitoneal) and treated on Day 2 with 0.5 × 106 CAR-T or SEAKER cells (intraperitoneal). For enzyme activity studies, ascites and peripheral blood samples were taken on Day 4. For efficacy studies, prodrug was administered beginning on Day 4. For prodrug retreatment studies, Ceph-AMS (3) was administered again beginning on Day 22 post tumor engraftment (4 mg/kg, ip, bid × 3 doses). For enzyme persistence studies, SEAKER cells were extracted on Day 30 post tumor engraftment and analyzed for exhaustion markers and β-Lac enzyme activity.

For the mixed antigen-positive/negative tumor model, a total of 2 × 106 Nalm6 cells were engrafted on Day 0 (1:1 Nalm6-gLuc [CD19+/mCherry+/Gaussia luciferase+] and Nalm6-fLuc [CD19−/eGFP+/firefly luciferase+]). Mice were treated on Day 10 with 1 × 106 CAR-T or SEAKER cells (intraperitoneal), and Ceph-AMS prodrug (3) was administered on Day 14 (4 mg/kg ip, bid for 3 total doses).

For enzyme persistence studies, SEAKER cells were extracted on Day 30 post tumor engraftment by injection of 3 mL PBS directly into the peritoneum, followed by gentle agitation and withdrawal using a syringe. Cells were centrifuged and analyzed for exhaustion markers and β-Lac enzyme activity.

Subcutaneous model:

NSG mice (NOD.Cg-Prkdcscid Il2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ, 7–13 weeks old, male and female) were obtained from Jackson Laboratory. Mice were engrafted on Day 0 with 1 × 106 Raji-eGFP/fLuc cells (1:1 with Matrigel, ThermoFisher 356234). On Day 7, 3 × 106 CAR-T or SEAKER cells were injected in the tail vein. For enzyme activity studies, tumors were resected on Day 16 and analyzed. For efficacy studies, prodrug was administered beginning on Day 15 (AMS-Glu (2): 50 mg/kg, ip, bid on days 15–20 post tumor engraftment); (Ceph-AMS (3): 4 mg/kg ip, bid on days 15, 17, 19 post tumor engraftment).

Syngeneic model:

C57BL/6 mice (7–13 weeks old, male and female) were obtained from Jackson Laboratory. Mice were engrafted on Day 0 with 3 × 106 ID8 tumor cells (intraperitoneal). On Day 20, tumor-bearing mice were preconditioned with 100 mg/kg cyclophosphamide to improve adoptive T cell engraftment, then on Day 21, 3 × 106 β-Lac-MUC28z SEAKER cells were engrafted (intraperitoneal). On Day 28, mice were euthanized and a peritoneal lavage was performed using 3 mL PBS/mouse.

For SEAKER cell persistence studies, recovered cells were washed and centrifuged in PBS, then stained with a Myc-Tag (71D10) rabbit mAb (PE conjugate) (Cell Signaling Technology 64025) to detect CAR expression.

For enzyme persistence studies, recovered cells were lysed on dry ice and soluble proteins were dissolved in PBS, then analyzed in the nitrocefin assay above.

For ex vivo immunogenicity assays, sera were collected from the mice in a separate experiment at the indicated time points by cheek bleed, followed by clotting and centrifugation of whole blood. Recombinant β-Lac was coated onto an ELISA plate at 100 ng/mL in ELISA coating buffer (0.05 M carbonate-bicarbonate, pH 9.6). Collected sera were incubated on the coated plates for 1 h. After washing, goat α-mouse IgG-HRP was incubated in each well, followed by development with TMB substrate and stopping with H2SO4. Absorbance at 450 nm was read on a SpectraMax M2 plate reader (Molecular Devices). Data were analyzed with SoftMax Pro software.

Immunohistochemistry

The immunohistochemistry detection of β-Lac was performed at MSK Molecular Cytology Core Facility, using Discovery XT processor (Ventana Medical Systems). A rabbit β-Lac antibody was used in 6 μg/ml concentration. The incubation with the primary antibody was done for 5 h, followed by 60 min incubation with biotinylated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Vector labs, cat#:PK6101) in 5.75 μg/ml, Blocker D, Streptavidin- HRP and DAB detection kit (Ventana Medical Systems) were used according to the manufacturer instructions. Slides were counterstained with hematoxylin and coverslipped with Permount (Fisher Scientific).

CRISPR-Cas9 knockout of CD19

Nalm6 GFP+/firefly luciferase+/CD19-KO cells were generated by transduction of Nalm6-GFP+/firefly luciferase+ cells with LentiCRISPRv2 (Addgene plasmid 52961) (Sanjana NE et al 2014 Nature Methods) encoding a sgRNA targeting CD19 (CCCCATGGAAGTCAGGCCCG). Successful knockout was confirmed by flow cytometry and CD19-negative cells were FACS sorted to >97% purity.

Bioluminescent imaging

Bioluminescent tumor imaging was performed using a Xenogen IVIS imaging system with Living Image software (Xenogen Biosciences). Image acquisition was done on a 25-cm field of view at medium binning level at various exposure times. Coelenterazine (100 μg) was administered ip for gLuc-CAR-T studies, or via retro-orbital injection for subcutaneous tumor studies. D-Luciferin (3 μg) was administered intraperitoneally for firefly luciferase tumor imaging. Images in a single data set were normalized together according to color intensity as indicated by scale bar.

Statistical analysis

Log-rank (Mantel–Cox) and Student’s t-tests (two-tailed) were performed using GraphPad Prism where appropriate. Statistical significance was indicated accordingly: * = p < 0.05, ** = p < 0.01, *** = p < 0.001. For all technical replicates reported, measurements were taken from distinct samples.

Data availability statement

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Information files. Any raw data not provided therein are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Extended Data

Extended Data Fig. 1. Synthesis of AMS-Glu prodrug (2).

Synthesis of AMS-Glu prodrug (2). DMA = N,N-dimethylacetamide; DMF = N,N-dimethylformamide; TBAF = tetrabutylammonium fluoride; TBS = t-butyldimethylsilyl.

Extended Data Fig. 2. Synthesis of Ceph-AMS prodrug (3).

Synthesis of Ceph-AMS prodrug (3). (a) Synthesis of protected AMS precursor S9. (b) Synthesis of Ceph-AMS (3). pyr = pyridine; TFA = trifluoroacetic acid; THF = tetrahydrofuran; TMS = trimethylsilyl.

Extended Data Fig. 3. Complete bioluminescent imaging data for in vivo efficacy in mouse intraperitoneal Raji tumor xenografts.

Complete bioluminescent imaging data for in vivo efficacy in mouse intraperitoneal Raji tumor xenografts treated with (a) CPG2–19BBz SEAKER cells and AMS-Glu (2) (50 mg/kg, ip, bid, days 2–7 post-CAR engraftment, 12 doses total, gray band) or (b) β-Lac-19BBz SEAKER cells and Ceph-AMS (3) (4 mg/kg, ip, bid, days 2–3 post CAR engraftment, 3 doses total, gray band). Raw BLI is plotted on log scale; AUC is plotted on split linear scale. (mean ± s.d. of n = 5 mice per group; experiment was repeated with similar results.) Representative images are shown in Fig. 5d and 5e, respectively, of the manuscript.

Extended Data Fig. 4. Complete bioluminescent imaging data for in vivo efficacy against antigen-negative cells in intraperitoneal heterogeneous tumor xenografts.

Complete bioluminescent imaging data for in vivo efficacy against antigen-negative cells in intraperitoneal heterogeneous tumor xenografts. (a) Bioluminescent imaging (BLI) and quantification of CD19+ Nalm6 cells expressing mCherry and Gaussia luciferase (Nalm6-mCherry/gLuc [CD19+]) in untreated mice or mice receiving β-Lac-19BBz SEAKER cells plus or minus 3 injections of Ceph-AMS (3: 4 mg/kg, ip, bid). Images taken at day 20 post tumor engraftment; one mouse in the group treated with SEAKER cells and prodrug showed tumor clearance but died after day 14 and is omitted. Complete radiance data is shown in the right two panels, with raw BLI plotted on log scale and AUC plotted on a linear scale. (Mean ± s.d. of n = 4 (untreated, SEAKER+prodrug) or n = 5 (SEAKER alone) mice per group; Student’s two-tailed t-test: ns = not significant; *p<0.05; experiment was performed once). (b) BLI and quantification of CD19– Nalm6 cells expressing eGFP and firefly luciferase (Nalm6-eGFP/fLuc [CD19–]) in untreated mice or mice receiving β-Lac-19BBz SEAKER cells plus or minus 3 injections of Ceph-AMS (3: 4 mg/kg, ip, bid). Images taken at day 17 post tumor engraftment; one mouse in the group treated with SEAKER cells and prodrug died after day 14 and is omitted. The left two panels also appear in Fig. 5g,h of the manuscript. Complete radiance data is shown in the right two panels, with raw BLI plotted on log scale and AUC plotted on a linear scale. (Mean ± s.d. of n = 4 (untreated, SEAKER+prodrug) or n = 5 (SEAKER alone) mice per group; Student’s two-tailed t-test: ns = not significant; *p<0.05; experiment was performed once).

Extended Data Fig. 5. Persistence of β-Lacenzyme activity and Ceph-AMS prodrug activation in mouse intraperitoneal Raji tumor xenografts after SEAKER cell exhaustion in vivo.

Persistence of β-Lac enzyme activity and Ceph-AMS prodrug activation in mouse intraperitoneal Raji tumor xenografts after SEAKER cell exhaustion in vivo. (a) Experimental scheme for rescue of relapsed Raji xenograft by treatment with Ceph-AMS (3: 4 mg/kg, ip, bid, days 4–5, 3 doses total, then days 22–23 (gray bar), 3 doses total) after exhaustion of β-Lac-19BBz SEAKER cells. (b) Quantitation of tumor bioluminescence before and after second dosing period (median with s.d. of n = 4 mice per group; experiment was performed once). (c) Persistence of β-Lac enzyme activity in β-Lac-19BBz SEAKER cells extracted from two of the mice from the experiment in panel a at day 30 (day 28 post administration), in comparison to standard 19BBz CAR-T cell controls (flow cytometry analysis: β-Lac substrate = CCF2-AM).

Extended Data Fig. 6. Construction and characterization of βLac-expressing murine SEAKER cells.

Construction and characterization of β-Lac-expressing murine SEAKER cells. (a) SEAKER construct encoding secreted β-Lac and a murine CAR: β-Lac-MUC28z (β-Lac/α-MUC16/CD28/CD3ζ). LTR = long terminal, Ψ = psi packaging element, FLAG = FLAG epitope tag (pink), P2A = 2A self cleaving peptide, α-MUC16 scFv = MUC-16-specific mouse-derived single chain variable fragment, myc = Myc epitope tag (brown), mCD28 = mouse CD28 costimulatory domain (green), mCD3ζ = mouse CD3 zeta chain (red). (b) Flow cytometry analysis of α-MUC16 CAR expression in retrovirally-transduced primary mouse T cells (fluorescently (phycoerythrin, PE) labeled anti-idiotype antibody; representative data from 5 independent experiments). (c) Trans-cytotoxicity of supernatant fluid (sn) from β-Lac-MUC28z SEAKER cells with or without Ceph-AMS (3: 107 nM) against mouse EL4 lymphoma cells, compared to prodrug alone and parent drug AMS (1: 500 nM) (24 h, CellTiter-Glo assay; mean ± s.d. of n = 3 technical replicates/samples; Student’s two-tailed t-test: ns = not significant, ***p<0.001; experiment was perfomed once).

Extended Data Fig. 7. Assessment of SEAKER cell immunogenicity in an immunocompetent mouse model.

Assessment of SEAKER cell immunogenicity in an immunocompetent mouse model. (a) Experimental scheme to assess immunogenicity of β-Lac-MUC28z SEAKER cells in a syngeneic intraperitoneal ID8 tumor model. Sera were collected on Days 21, 24, 28, and 31 and tested for anti-β-Lac antibodies in panel b. In a separate experiment, ascites were recovered on Day 28 by peritoneal lavage and tested for the presence of SEAKER cells in panels c,d and β-Lac enzyme activity in panel e. (b) Detection anti-β-Lac antibodies in sera over 10 days following SEAKER cell engraftment (Days 21–31) (median with lines representing each individual mouse of n = 12; experiment was performed once). (c,d) Flow cytometry analysis of SEAKER cell (myc+) persistence among T cells (CD3+) and (e) nitrocefin cleavage-based quantitation of β-Lac enzyme activity in ascites recovered 7 days after SEAKER cell engraftment (Day 28) (representative data shown from n = 2 mice per group; on average, 25% of T cells were SEAKER-positive; experiment was performed once). SSC = side scatter. (f) In a third experiment, mice were treated as in panel a, but without cyclophosphamide pretreatment to maximize the antibody response, then sera were recovered 5 days after SEAKER cell engraftment (Day 26) and analyzed for anti-β-Lac antibodies (n = 1 mouse in untreated group; n = 5 mice in treated group; mean ± s.d. of n = 3 technical replicates from each mouse; experiment was performed once). Sera from the 4 mice showing anti-β-Lac antibodies were used for the ex vivo enzyme activity experiment in panel g. (g) Nitrocefin cleavage-based quantitation of enzyme activity of recombinant β-Lac treated with sera from untreated or SEAKER-treated mice from panel f (n = 2 mice in untreated group; mean ± s.d. of n = 4 mice in treated group; experiment was performed once).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Elisa de Stanchina and Connor Hagen (MSK Antitumor Assessment Core Facility) for assistance with mouse toxicology studies, George Sukenick and Rong Wang (MSK Analytical NMR Core Facility) for expert NMR and mass spectral support, J. Fraser Glickman and Carolina Adura Alcaino (Rockefeller High-Throughput and Spectroscopy Resource Center) for assistance with SPE-MS experiments, Gabriela Chiosis and Sahil Sharma (MSK) for assistance with LC-MS/MS experiments, and Barney Yoo (MSK) for helpful discussions on the synthesis of APdMG-Glu. Financial support from the NIH (P01 CA023766 to D.A.S. and D.S.T., R01 CA55349 and R35 CA241894 to D.A.S., R01 AI118224 to D.S.T., and CCSG P30 CA008748 to C. B. Thompson), the Tudor Fund (to D.A.S.), the Lymphoma Fund (to D.A.S.), and the Commonwealth Foundation and MSK Center for Experimental Therapeutics (to D.A.S. and D.S.T.) is gratefully acknowledged.

Competing Interests Statement

D.A.S., D.S.T., and R.J.B. are consultants for, have equity in, and have sponsored research agreements with CoImmune, which has licensed technology described in this manuscript from MSK. D.A.S. has equity in or is a consultant for: Actinium Pharmaceuticals, Arvinas, Eureka Therapeutics, Iovance Biotherapeutics, OncoPep, Pfizer, Repretoire, and Sellas. D.S.T. has been a consultant and/or paid speaker for Eli Lilly, Elsevier, Emerson Collective, Merck, National Institutes of Health, Venenum Biodesign, the Research Center for Molecular Medicine of the Austrian Academy of Sciences, and the Institute for Research in Biomedicine, Barcelona. R.J.B. is a co-founder and receives royalties from Juno Therapeutics/Celgene. MSK has filed for patent protection behalf of T.J.G., J.P.L., D.S.T., and D.A.S. for inventions described in this manuscript. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Feldman SA, Assadipour Y, Kriley I, Goff SL & Rosenberg SA Adoptive cell therapy—Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, T-cell receptors, and chimeric antigen receptors. Semin. Oncol. 42, 626–639 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leon E, Ranganathan R & Savoldo B Adoptive T cell therapy: Boosting the immune system to fight cancer. Semin. Immunol. 49, 101437 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sadelain M, Rivière I & Riddell S Therapeutic T cell engineering. Nature 545, 423–431 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beyar-Katz O & Gill S Advances in chimeric antigen receptor T cells. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 27, 368–377 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.June CH, O’Connor RS, Kawalekar OU, Ghassemi S & Milone MC CAR T cell immunotherapy for human cancer. Science 359, 1361–1365 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sermer D & Brentjens R CAR T-cell therapy: Full speed ahead. Hematol. Oncol. 37 Suppl 1, 95–100 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sotillo E et al. Convergence of acquired mutations and alternative splicing of CD19 enables resistance to CART-19 immunotherapy. Cancer Discov. 5, 1282–1295 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maude SL et al. Chimeric antigen receptor T cells for sustained remissions in leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 371, 1507–1517 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Majzner RG & Mackall CL Tumor antigen escape from CAR T-cell therapy. Cancer Discov. 8, 1219–1226 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anderson KG, Stromnes IM & Greenberg PD Obstacles posed by the tumor microenvironment to T cell activity: A case for synergistic therapies. Cancer Cell 31, 311–325 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kasakovski D, Xu L & Li Y T cell senescence and CAR-T cell exhaustion in hematological malignancies. J. Hematol. Oncol. 11, 91 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Neelapu SS et al. Chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy - Assessment and management of toxicities. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 15, 47–62 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dunbar CE et al. Gene therapy comes of age. Science 359, eaan4672 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lim WA & June CH The principles of engineering immune cells to treat cancer. Cell 168, 724–740 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rafiq S et al. Targeted delivery of a PD-1-blocking scFv by CAR-T cells enhances anti-tumor efficacy in vivo. Nat. Biotechnol. 36, 847–856 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yeku OO, Purdon TJ, Koneru M, Spriggs D & Brentjens RJ Armored CAR T cells enhance antitumor efficacy and overcome the tumor microenvironment. Sci. Rep. 7, 10541 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Avanzi MP et al. Engineered tumor-targeted T cells mediate enhanced anti-tumor efficacy both directly and through activation of the endogenous immune system. Cell Rep. 23, 2130–2141 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boice M et al. Loss of the HVEM tumor suppressor in lymphoma and restoration by modified CAR-T cells. Cell 167, 405–418 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuhn NF et al. CD40 ligand-modified chimeric antigen receptor T cells enhance antitumor function by eliciting an endogenous antitumor response. Cancer Cell 35, 473–488 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brudno JN & Kochenderfer JN Recent advances in CAR T-cell toxicity: Mechanisms, manifestations and management. Blood Rev. 34, 45–55 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lambert JM & Berkenblit A Antibody-drug conjugates for cancer treatment. Annu. Rev. Med. 69, 191–207 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sharma SK & Bagshawe KD Translating antibody directed enzyme prodrug therapy (ADEPT) and prospects for combination. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 17, 1–13 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nemunaitis J et al. Pilot trial of genetically modified, attenuated Salmonella expressing the E. coli cytosine deaminase gene in refractory cancer patients. Cancer Gene Ther 10, 737–744 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sherwood RF, Melton RG, Alwan SM & Hughes P Purification and properties of carboxypeptidase G2 from Pseudomonas sp. strain RS-16. Use of a novel triazine dye affinity method. Eur. J. Biochem. 148, 447–453 (1985). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fleming PC, Goldner M & Glass DG Observations on the nature, distribution, and significance of cephalosporinase. Lancet 1, 1399–1401 (1963). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jaffe JJ, McCormack JJ & Meymerian E Trypanocidal properties of 5´-O-sulfamoyladenosine, a close structural analog of nucleocidin. Exp. Parasitol. 28, 535–543 (1970). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rengaraju S et al. 5´-O-Sulfamoyladenosine (defluoronucleocidin) from a Streptomyces. Meiji Seika Kenkyu Nenpo 25, 49–55 (1986). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Francis RJ et al. A Phase I trial of antibody directed enzyme prodrug therapy (ADEPT) in patients with advanced colorectal carcinoma or other CEA producing tumours. Br. J. Cancer 87, 600–607 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Springer CJ et al. Optimization of alkylating agent prodrugs derived from phenol and aniline mustards: a new clinical candidate prodrug (ZD2767) for antibody-directed enzyme prodrug therapy (ADEPT). J. Med. Chem. 38, 5051–5065 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yoo B et al. Ultrasmall dual-modality silica nanoparticle drug conjugates: Design, synthesis, and characterization. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 23, 7119–7130 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harding FA et al. A beta-lactamase with reduced immunogenicity for the targeted delivery of chemotherapeutics using antibody-directed enzyme prodrug therapy. Mol. Cancer Ther. 4, 1791–1800 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marais R et al. A cell surface tethered enzyme improves efficiency in gene-directed enzyme prodrug therapy. Nat. Biotechnol. 15, 1373–1377 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brentjens RJ et al. Genetically targeted T cells eradicate systemic acute lymphoblastic leukemia xenografts. Clin. Cancer Res. 13, 5426–5435 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu Z et al. Systematic comparison of 2A peptides for cloning multi-genes in a polycistronic vector. Sci. Rep. 7, 2193 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Levy CC & Goldman P The enzymatic hydrolysis of methotrexate and folic acid. J. Biol. Chem. 242, 2933–2938 (1967). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bulychev A & Mobashery S Class C beta-lactamases operate at the diffusion limit for turnover of their preferred cephalosporin substrates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43, 1743–1746 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Santos EB et al. Sensitive in vivo imaging of T cells using a membrane-bound Gaussia princeps luciferase. Nat. Med. 15, 338–344 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gurung N, Ray S, Bose S & Rai V A broader view: Microbial enzymes and their relevance in industries, medicine, and beyond. BioMed Res. Int. 2013, 329121 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mayer A et al. Modifying an immunogenic epitope on a therapeutic protein: A step towards an improved system for antibody-directed enzyme prodrug therapy (ADEPT). Br J Cancer 90, 2402–2410 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]