Abstract

Objectives

With the availability of vaccines, commercial assays detecting anti–severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) antibodies evolved toward quantitative assays directed to the spike glycoprotein or its receptor-binding domain (RBD). The objective was to perform a large-scale, longitudinal study involving health care workers (HCWs), with the aim of establishing the kinetics of immune response throughout the 9-month period after receipt of the second dose of the BNT162b2 vaccine.

Methods

Quantitative determination of immunoglobulin (Ig) G antibodies against the RBD of the S1 subunit of the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 on the Alinity systems.

Results

The highest levels of anti-RBD IgG were measured after 1 month from full vaccination (median: 1432 binding antibody units/ml [BAU/ml]); subsequently, a steep decrease (7.4-fold decrease) in IgG levels was observed at 6 months (median: 194.3 BAU/ml), with a further 2.5-fold decrease at 9 months (median: 79.3 BAU/ml). Furthermore, the same data, when analyzed for sex, showed significant differences between male and female participants at both 1 and 9 months from vaccination, but not at 6 months.

Conclusion

Our results confirm the tendency of anti-RBD antibodies to decrease over time, also when extending the analysis up to 9 months, and highlight a better ability of the female sex to produce antibodies 1 month and 9 months after vaccination. Overall, these data, obtained in a wide population of HCWs, support the importance of having increased the vaccine doses.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, Humoral Response, Anti-RBD IgG, BNT162b2, Health care workers

Introduction

Two years after the initial spread of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection, and 1 year from the start of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccination campaign, approximately 416 million people have been infected and a total of approximately 10 billion vaccine doses have been administered worldwide (https://covid19.who.int, accessed on February 15, 2022). Despite a wide range of technologies having been used, including live attenuated, viral vectored, messenger RNA (mRNA)–based, protein-based, and inactivated vaccines (Ng et al., 2020), BNT162b2 was the first vaccine authorized for emergency use by the European Medicines Agency (https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/news/ema-recommends-first-covid-19-vaccine-authorisation-eu, accessed on May 5, 2022) and, in Italy, it was used for the first phase of the immunization program, primarily focused on health care workers (HCWs) (https://www.sa¬lute.gov.it/por¬tale/nuovocorona¬virus/dettaglioContenutiNuovoCoronavirus.jsp?lingua=italiano&id=5452&area=nuovoCoronavirus&menu=vuoto, accessed on May 5, 2022). Several studies have evaluated BNT162b2 efficacy and safety profile (Dighriri et al., 2022; Polack et al., 2020), reporting adverse events after the second dose, as compared with the first dose, following an active surveillance (Ripabelli et al., 2022).

Vaccine immunity involves both cellular and humoral pathways. Given cellular immunity is not easy to assess on a large scale, the evaluation of vaccine effectiveness mainly relies on quantitative measurement of antibodies (Shi and Ren, 2021; Van Tilbeurgh et al., 2021). During the current pandemic, many serological tests, directed at the spike glycoprotein or its receptor-binding domain (RBD) and based on different technologies, have been used (Saker et al., 2022; Van Elslande et al., 2020). The World Health Organization (WHO) released an international standard to facilitate comparison of the results obtained with different assay and in different countries (Knezevic et al., 2022), but its real utility in enabling comparability harmonization of data has been criticized (Ferrari et al., 2021; Matusali et al., 2022; Perkmann et al., 2021). Independently from the used assay, numerous studies agree in highlighting a significant decrease of anti–SARS-CoV-2 antibodies produced after 3 to 6 months after vaccination and have criticized a consequent increased susceptibility to infection for subjects who completed the vaccination schedule from 6 months (Bayart et al., 2021; Bochnia-Bueno et al., 2022; Ferrari et al., 2021; Matusali et al., 2022; Perkmann et al., 2021). In this context, decreasing antibodies over time and immune escape have driven the discussion on the need for evolution of vaccine strategies, such as additional dosing (Garcia-Beltran et al., 2022; Lopez Bernal et al., 2021).

Here, we report the results of a large-scale, longitudinal study involving HCWs that was conducted to assess the kinetics of immune response throughout the 9-month period after receipt of the second dose of the BNT162b2 vaccine.

Methods

Study cohort

A total of 4029 serum samples were longitudinally collected from 1343 HCWs from the San Camillo-Forlanini Hospital who administered the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine (Comirnaty, BioNTech Manufacturing GmbH, Mainz, Germany) during the period February to October 2021. The inclusion criteria for the participants were (1) to be personnel performing health care activities; (2) to sign an informed consent form agreeing to the study aims; (3) to have received and completed the BNT162b2 vaccination; (4) to have been tested for anti-RBD immunoglobulin (Ig) G at 1 month, 6 months, and 9 months after the second dose of Comirnaty; and (5) to have declared no active or past SARS-CoV-2 infection. Descriptive analysis of the cohort study is reported in Table 1 . All samples and volunteers’ data (age, sex) were stored in a pseudonymized manner.

Table 1.

Description of analyzed samples.

| Numbers of HCWs | Month of collection | Positive (%) | Negative (%) | M (%) | F (%) | Median age (min-max) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1343 | February | 1340 (99.8) | 3 (0.2) | 402 (29.9) | 941 (70.1) | 51 (24-68) |

| July | 1338 (99.6) | 5 (0.4) | ||||

| October | 1323 (98.5) | 20 (1.5) |

HCW, health care worker; M, male; F, female; min, minimum; max, maximum.

SARS-CoV-2 IgG II Quant assay

Chemiluminescent microparticle immunoassay, SARS-CoV-2 IgG II Quant assay by Abbott Laboratories (North Chicago, IL), was used for quantitative determination of IgG antibodies against the RBD of the S1 subunit of the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 on the Alinity systems, according to the manufacturer's instructions. Results have been expressed in binding antibody units/ml (BAU/ml) owing to the availability of a conversion factor from arbitrary units/ml (AU/ml) for the assay (1 BAU/ml = 0.142 AU/ml), after the release of a WHO standard preparation for SARS-CoV-2 binding antibodies (Kristiansen et al., 2021). SARS-CoV-2 IgG II positivity range spans from 7.1 BAU/ml (positivity threshold) to 11,360 BAU/ml.

Statistical analysis

GraphPad Software (version 9.0.2, La Jolla, CA) was used to perform statistic comparisons (P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant).

Results

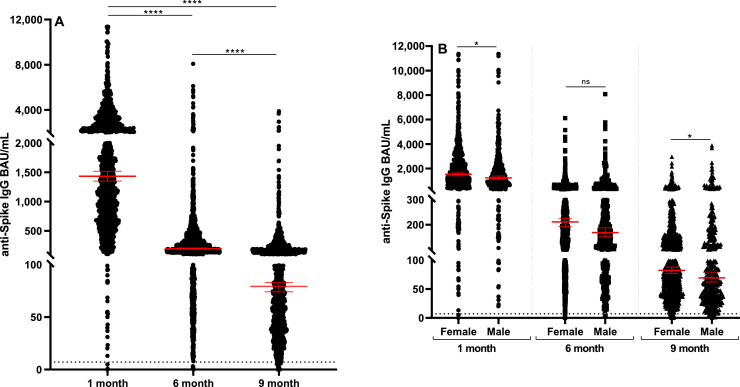

We included in the analysis sera from 1343 HCWs, 402 men (29.9%) and 941 women (70.1%), with a median age of 51 years (range: 24-68). We first performed a quantitative determination of anti-RBD IgG antibodies at different time points from vaccination. As expected, the highest levels of anti-RBD IgG were measured after 1 month from full vaccination (median: 1432 BAU/ml; min-max: 0.1-11,360 BAU/ml); subsequently, a steep decrease (7.4-fold decrease) in IgG levels was observed at 6 months (median: 194.3 BAU/ml; range: 0.0-8080 BAU/ml), with a further 2.5-fold decrease at 9 months (median: 79.3 BAU/ml; range: 0.0-3881 BAU/ml). Differences among median results obtained at the three times of observation were all highly significant (P < 0.0001; Figure 1 A). Furthermore, analyzing the same data for sex by unpaired t-test, we observed weak but significant differences between male and female sex at both 1 and 9 months from vaccination (P = 0.0373 and P = 0.0291, respectively), although a not significant difference was revealed at 6 months (Figure 1B). When stratifying samples into groups based on age (<30, 31-40, 41-50, 51-60, >60), we did not observe any significant difference among groups at 1, 6, and 9 months from vaccination. Nevertheless, in all age groups analyzed, the decrease of IgG levels after 6 and 9 months from vaccination remains significant, as compared with IgG levels observed after 1 month.

Figure 1.

Patterns of anti-RBD IgG persistence. (A) Titers of anti-RBD IgG antibodies in longitudinally collected samples from 1343 HCWs after the second dose of Comirnaty (1 month, 6 months, 9 months), expressed as BAU/ml. (B) Comparison between titers of anti-RBD IgG antibodies in longitudinally collected samples analyzed for sex. The asterisks indicate statistically significant differences determined by Student’s t-test (**** p<0.0001; *p <0.05; ns p≥0.05)

BAU/ml, binding antibody units/ml; HCW, health care worker; IgG, immunoglobulin G; ns, not significant; RBD, receptor-binding domain.

Discussion

With the availability of vaccines, quantitative serological assays provide an important contribution in understanding the immunization status of the different populations of vaccinated individuals. Most scientific publications describe the trend of the antibodies following the first 6 months after vaccination (Bochnia-Bueno et al., 2021; Garcia-Beltran et al., 2022; Matusali et al., 2022). In this study, we observed the evolution of humoral response to BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine in a very wide population (1343 HCWs) in a 9-month follow-up study by analyzing the persistence of anti-RBD antibodies. Our results indicate that the highest levels of anti-RBD IgG were measured after 1 month from full vaccination (median: 1432 BAU/ml); subsequently, a steep decrease (7.4-fold decrease) in IgG levels was observed at 6 months (median: 194.3 BAU/ml), with a further 2.5-fold decrease at 9 months (median: 79.3 BAU/ml). When analyzing the same data for sex, significant differences between men and women at both 1 and 9 months from vaccination were observed, suggesting a greater ability of the female sex to produce anti-RBD antibodies. These data are in agreement with previous observational studies reporting that men seem to be consistently overrepresented in SARS-CoV-2 infection and in COVID-19 severe outcomes, including higher fatality rates (Haitao et al., 2020; Jin et al., 2020; Meng et al., 2020). These differences have been hypothesized to depend on gender-specific behaviors, genetic and hormonal factors, and sex differences in biological pathways related to SARS-CoV-2 infection; nevertheless, the different ability between men and women to produce antibodies that was observed in our study could contribute to this phenomenon and should be better elucidated. Larger studies with sex-specific reporting and robust analyses are crucial to clarify how sex modifies cellular and molecular pathways associated with SARS-CoV-2. We further explored the possible impact of age on anti-RBD antibody decrease by stratifying our results into groups based on age, but we did not observe any significant difference among groups at 1, 6, and 9 months from vaccination. Overall, our results, obtained in a wide population of HCWs, confirm the tendency of anti-RBD antibodies to decrease over time, also when extending the analysis up to 9 months, and they highlight a better ability of the female sex to produce antibodies 1 month and 9 months after vaccination. Moreover, these data support the importance of having increased the vaccine doses, considering also the recent findings that underscore the importance of receiving a third vaccine dose to prevent moderate and severe COVID-19, especially when the Omicron variant is predominant and the effectiveness of two doses of vaccines is reduced against this variant (Thompson et al., 2022).

Acknowledgments

Conflict of interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Funding

Unrestricted grant.

Ethical approval statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and with the protocol code no. 135, approved on 05/02/22021, by Comitato Etico Lazio 1, according to which the study protocol here described provide for the signing of an informed consent by the patients; no further samples were taken other than those performed for diagnostic purposes. The data of biological samples collected for diagnostic purposes were used only after their complete anonymization, and the results of the tests had no impact on the clinical management of the patients. Furthermore, the analysis of genetic data was not provided.

Author contributions

LB and GS analyzed data and wrote and revised the manuscript; BM designed the study, performed laboratory testing, and revised the manuscript; GP read and revised the manuscript; sand CNP, RAC, AM, and PG supervised scientific activities.

References

- Bayart JL, Douxfils J, Gillot C, David C, Mullier F, Elsen M, Eucher C, Van Eeckhoudt S, Roy T, Gerin V, Wieers G, Laurent C, Closset M, Dogné JM, Favresse J. Waning of IgG, total and neutralizing antibodies 6 months post-vaccination with BNT162b2 in healthcare workers. Vaccines (Basel) 2021;9:1092. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9101092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bochnia-Bueno L, De Almeida SM, Raboni SM, Adamoski D, Amadeu LLM, Carstensen S, Nogueira MB. Dynamic of humoral response to SARS-CoV-2 anti-Nucleocapsid and Spike proteins after CoronaVac vaccination. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2022;102 doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2021.115597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dighriri IM, Alhusayni KM, Mobarki AY, Aljerary IS, Alqurashi KA, Aljuaid FA, Alamri KA, Mutwalli AA, Maashi NA, Aljohani AM, Alqarni AM, Alfaqih AE, Moazam SM, Almutairi MN, Almutairi AN. Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine (BNT162b2) side effects: a systematic review. Cureus. 2022;14:e23526. doi: 10.7759/cureus.23526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari D, Clementi N, Spanò SM, Albitar-Nehme S, Ranno S, Colombini A, Criscuolo E, Di Resta C, Tomaiuolo R, Viganó M, Mancini N, De Vecchi E, Locatelli M, Mangia A, Perno CF, Banfi G. Harmonization of six quantitative SARS-CoV-2 serological assays using sera of vaccinated subjects. Clin Chim Acta. 2021;522:144–151. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2021.08.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Beltran WF, St Denis KJ, Hoelzemer A, Lam EC, Nitido AD, Sheehan ML, Berrios C, Ofoman O, Chang CC, Hauser BM, Feldman J, Roederer AL, Gregory DJ, Poznansky MC, Schmidt AG, Iafrate AJ, Naranbhai V, Balazs AB. mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccine boosters induce neutralizing immunity against SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant. Cell. 2022;185:457–466. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.12.033. e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haitao T, Vermunt JV, Abeykoon J, Ghamrawi R, Gunaratne M, Jayachandran M, Narang K, Parashuram S, Suvakov S, Garovic VDs. Mayo Clin Proc. 2020;95:2189–2203. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin JM, Bai P, He W, Wu F, Liu XF, Han DM, Liu S, Yang JK. Gender differences in patients with COVID-19: focus on severity and mortality. Front Public Health. 2020;8:152. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knezevic I, Mattiuzzo G, Page M, Minor P, Griffiths E, Nuebling M, Moorthy V. WHO International Standard for evaluation of the antibody response to COVID-19 vaccines: call for urgent action by the scientific community. Lancet Microbe. 2022;3:e235–e240. doi: 10.1016/S2666-5247(21)00266-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kristiansen PA, Page M, Bernasconi V, Mattiuzzo G, Dull P, Makar K, Plotkin S, Knezevic I. WHO International Standard for anti-SARS-CoV-2 immunoglobulin. Lancet. 2021;397:1347–1348. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00527-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez Bernal J, Andrews N, Gower C, Gallagher E, Simmons R, Thelwall S, Stowe J, Tessier E, Groves N, Dabrera G, Myers R, Campbell CNJ, Amirthalingam G, Edmunds M, Zambon M, Brown KE, Hopkins S, Chand M, Ramsay M. Effectiveness of Covid-19 vaccines against the B.1.617.2 (delta) variant. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:585–594. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2108891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matusali G, Sberna G, Meschi S, Gramigna G, Colavita F, Lapa D, Francalancia M, Bettini A, Capobianchi MR, Puro V, Castilletti C, Vaia F, Bordi L. Differential dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 binding and functional antibodies upon BNT162b2 vaccine: a 6-month follow-up. Viruses. 2022;14:312. doi: 10.3390/v14020312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng Y, Wu P, Lu W, Liu K, Ma K, Huang L, Cai J, Zhang H, Qin Y, Sun H, Ding W, Gui L, Wu P. Sex-specific clinical characteristics and prognosis of coronavirus disease-19 infection in Wuhan, China: a retrospective study of 168 severe patients. PLoS Pathog. 2020;16 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1008520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng WH, Liu X, Mahalingam S. Development of vaccines for SARS-CoV-2. F1000Res. 2020;9 doi: 10.12688/f1000research.25998.1. F1000 Faculty Rev-991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkmann T, Perkmann-Nagele N, Koller T, Mucher P, Radakovics A, Marculescu R, Wolzt M, Wagner OF, Binder CJ, Haslacher H. Anti-spike protein assays to determine SARS-CoV-2 antibody levels: a head-to-head comparison of five quantitative assays. Microbiol Spectr. 2021;9 doi: 10.1128/spectrum.00247-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polack FP, Thomas SJ, Kitchin N, Absalon J, Gurtman A, Lockhart S, Perez JL, Pérez Marc G, Moreira ED, Zerbini C, Bailey R, Swanson KA, Roychoudhury S, Koury K, Li P, Kalina WV, Cooper D, Frenck RW, Jr, Hammitt LL, Türeci Ö, Nell H, Schaefer A, Ünal S, Tresnan DB, Mather S, Dormitzer PR, Şahin U, Jansen KU, Gruber WC, C4591001 Clinical Trial Group Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2603–2615. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2034577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ripabelli G, Tamburro M, Buccieri N, Adesso C, Caggiano V, Cannizzaro F, Di Palma MA, Mantuano G, Montemitro VG, Natale A, Rodio L, Sammarco ML. Active surveillance of adverse events in healthcare workers recipients after vaccination with COVID-19 BNT162b2 vaccine (Pfizer-BioNTech, Comirnaty): a cross-sectional study. J Community Health. 2022;47:211–225. doi: 10.1007/s10900-021-01039-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saker K, Escuret V, Pitiot V, Massardier-Pilonchéry A, Paul S, Mokdad B, Langlois-Jacques C, Rabilloud M, Goncalves D, Fabien N, Guibert N, Fassier JB, Bal A, Trouillet-Assant S, Trabaud MA. Evaluation of commercial anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibody assays and comparison of standardized titers in vaccinated health care workers. J Clin Microbiol. 2022;60 doi: 10.1128/JCM.01746-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi AC, Ren P. SARS-CoV-2 serology testing: progress and challenges. J Immunol Methods. 2021;494 doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2021.113060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson MG, Natarajan K, Irving SA, Rowley EA, Griggs EP, Gaglani M, Klein NP, Grannis SJ, DeSilva MB, Stenehjem E, Reese SE, Dickerson M, Naleway AL, Han J, Konatham D, McEvoy C, Rao S, Dixon BE, Dascomb K, Lewis N, Levy ME, Patel P, Liao IC, Kharbanda AB, Barron MA, Fadel WF, Grisel N, Goddard K, Yang DH, Wondimu MH, Murthy K, Valvi NR, Arndorfer J, Fireman B, Dunne MM, Embi P, Azziz-Baumgartner E, Zerbo O, Bozio CH, Reynolds S, Ferdinands J, Williams J, Link-Gelles R, Schrag SJ, Verani JR, Ball S, Ong TC. Effectiveness of a third dose of mRNA vaccines against COVID-19-associated emergency department and urgent care encounters and hospitalizations among adults during periods of Delta and Omicron variant predominance - VISION network, 10 states, August 2021–January 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:139–145. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7104e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Elslande J, Decru B, Jonckheere S, Van Wijngaerden E, Houben E, Vandecandelaere P, Indevuyst C, Depypere M, Desmet S, André E, Van Ranst M, Lagrou K, Vermeersch P. Antibody response against SARS-CoV-2 spike protein and nucleoprotein evaluated by four automated immunoassays and three ELISAs. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020;26:1557. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.07.038. e1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Tilbeurgh M, Lemdani K, Beignon AS, Chapon C, Tchitchek N, Cheraitia L, Marcos Lopez E, Pascal Q, Le Grand R, Maisonnasse P, Manet C. Predictive markers of immunogenicity and efficacy for human vaccines. Vaccines (Basel) 2021;9:579. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9060579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]