“In the middle of every difficulty lies opportunity.”

Albert Einstein

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has disrupted all aspects of oncologic care ranging from cancer screening and diagnosis[1] to management.[2,3] Clinical trials are integral to quality oncological care. For many patients with rare diseases or specific biomarker-driven cancers, clinical trials may be the only option beyond standard of care therapy. Clinical trials in patients with cancer are complex, with mandated protocol schedules including laboratory tests, scans, biopsies, and clinical visits centered on timing and multiple contact points with the healthcare system.3 At the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, thousands of children and adults with cancer were enrolled on clinical trials across the United States. COVID-19 posed a serious challenge to the conduct of clinical trials, ranging from new patient enrollment to monitoring of patients currently enrolled in clinical trials. If they could continue safely in clinical trials, safety of the enrolled patients with cancer was the primary concern because of the threat of COVID-19 infections. Safety assessments (vital signs, laboratory test, EKGs, and physical examination), tumor assessments (computed tomography scans, magnetic resonance imaging, and tumor markers), and treatment visits were all impacted. After the proclamation of COVID-19 as a national emergency by the President on March 13, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a draft guidance for conducting clinical trials of medical products during the COVID-19 public health emergency. The FDA recognized that clinical trial protocol modifications may be required to ensure patient safety, and deviations may arise with protocol-mandated procedures.[4] This timely guidance document facilitated investigators, industry, and academic centers to work with their institutional review boards to navigate the pandemic.[5] The initial response was to hold new patient enrollment while ensuring the safety of the current trial participants. Overall decrease in clinical trial enrollment has been reported dating back to early March, with several oncology trials (about 62 in March and 139 in April) suspended owing to COVID-19.[6] Two months into the pandemic, with increasing COVID-19 testing and increasing knowledge about COVID-19 in patients with cancer, new patient enrollment finally resumed in May.[7,8]

In this issue of Journal of Immunotherapy and Precision Oncology, Gupta et al.9 report the results of a study that sought to understand the impact of COVID-19 on clinical trials conducted by 51 National Cancer Institute (NCI)-Designated Cancer Centers. The authors utilized information provided on institutional websites and other external platforms such as the SWOG Cancer Research Network, Oncology Live, and Medscape for the purpose of this study. They found only 54.9% cancer centers provided information on the effect of the pandemic on the clinical trial availability at each center. The authors also assessed the issued statements as well as the impacts discussed and solutions proposed by each institution. Although some institutions have discussed how clinical trials and clinical research have been affected with the media and other oncology outlets, many centers do not currently provide any dedicated information discussing the conduct and accrual of clinical trials.

Although Gupta et al.[9] raise an important concern about the lack of patient education and public discussion regarding clinical trial conduct, accrual, and availability during the pandemic, the study has some limitations. First, utilization of institutional websites, external resources such as Medscape or Oncology Live, and media interviews for assessing the effect of pandemic on clinical trial conduct at major cancer centers is far from perfect, especially given the fact that the information on COVID-19, the effect of COVID-19 on patients with cancer, and the response and recommendations from the government are rapidly evolving. Early on in the pandemic, when most of the centers restricted new patient enrollment while maintaining the patients currently enrolled and with all the clinical trial personnel working from home, the clinician investigators and teams would have been in direct communication with the trial participants and their families, which is difficult to assess from the institutional websites. Furthermore, the variability in clinical trial enrollment described between centers in different states (eg, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Pittsburg, PA and Dana Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA) can be partially explained by the total number of cases of COVID-19 in each state and the variation in state-specific recommendations for COVID-19 response.

Despite this, the authors' suggestion of creating a COVID-19-specific webpage by each institution for the public's information is well founded, although keeping it up-to-date with all the institutional and state compliance rules required may be difficult in the rapidly changing pandemic scenario.

We commend the authors for bringing forth the overarching concern that COVID-19 has significantly affected conduct of clinical trials and that the constantly evolving landscape may leave patients out of the picture. Hence, we suggest that a public-facing dashboard displaying a readily available database of cancer clinical trials currently open or on hold at each of these institutions may be helpful for patients navigating to enroll in a clinical trial for their type of disease. Such a database should then potentially provide information of ongoing clinical trials at other institutions that might allow participation via telehealth and local centers, an improvisation of the clinical trial methodology that has evolved during the pandemic. From the trial perspective, this may ensure continual enrollment despite the ongoing pandemic and further fuel clinical research and modernization of clinical trial methodology.

It has been widely recognized that COVID-19 has led to “democratization” of clinical trial conduct, with increasing incorporation of telemedicine and virtual visits, allowance of local and less-frequent testing, including imaging, lower administrative burden, allowing drugs to be self-administered by patients, and less stringent follow-up restrictions.[10] Many have argued that the current pandemic may lead to optimization of how we conduct clinical trials with an emphasis on patient preference and safety while preserving scientific integrity.[11] The American Society of Clinical Oncology recommendations from Global Webinars have also suggested that minimizing data collection or abstraction to what is critical to inform the primary end point may be necessary during the crisis, with enhanced use of critical electronic systems to manage the documentation of protocol deviations.[12] Overall, we hope these improvements in the conduct of oncology clinical trials will bring the principal subject of clinical research to the forefront: the patient.

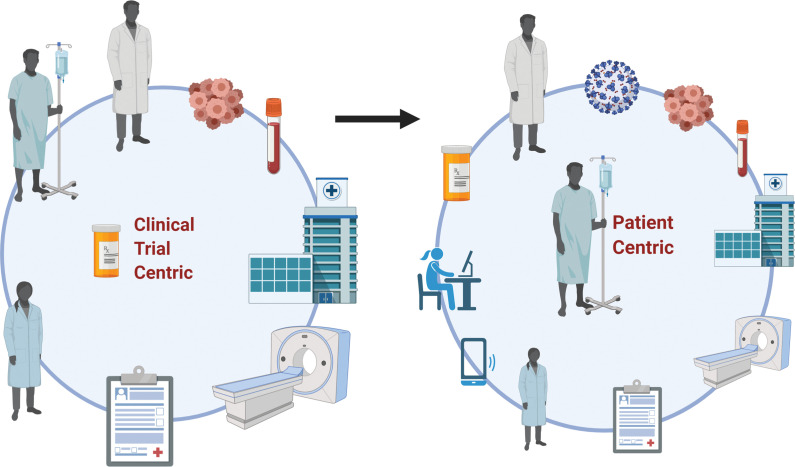

It is currently unclear what the long-term effects of the pandemic will be on the conduct, methodology, and enrollment of oncology clinical trials. We suspect a major shift in the way care is provided and research is conducted, both of which will create increased opportunity for collaboration and, possibly, enhanced accrual of participants (Fig. 1). In addition, the constantly changing landscape will create multiple opportunities to optimize and improve the way we conduct clinical trials, which may drive increased access to clinical trials to the underrepresented population subsets such as elderly patients and patients of ethnic minorities. This may be the silver lining of the pandemic in the field of oncology, so we hope that we find an opportunity in the middle of adversity to move clinical trials from being “trial centric” to more “patient centric.”

Figure 1.

COVID-19 and cancer clinical trial pandemonium: finding the silver lining from a clinical trial-centric to patient-centric approach. Traditional clinical trial methodology model where the rigid clinical trials mandate requirements for patients, physicians, clinical trial investigators, study teams, and hospitals. Improvisations in clinical trial methodology during COVID-19 to bring the patient to the center of the conduct of the clinical trial. Created with BioRender.com.

Funding Statement

Source of Support: None.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: Vivek Subbiah disclosed research funding/grant support for clinical trials from FUJIFILM Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc., Novartis, Bayer, GlaxoSmithKline, Nanocarrier, Vegenics, Celgene, Northwest Biotherapeutics, Berghealth, Incyte, Pharmamar, D3, Pfizer, Multivir, Amgen, Abbvie, Alfa-Sigma, Agensys, Boston Biomedical, Idera Pharma, Inhibrx, Exelixis, Blueprint Medicines, Loxo Oncology, Medimmune, Altum, Dragonfly Therapeutics, Takeda and Roche/Genentech, National Comprehensive Cancer Network, NCI-CTEP. Supported by UT MD Anderson Cancer Center (P30 CA016672). Travel assistance was provided by Novartis, Pharmamar, ASCO, ESMO, Helsinn, Incyte, US-FDA. Vivek Subbiah disclosed a consultancy advisory role for Helsinn, LOXO Oncology/Eli Lilly, Daichi Sankyo, R-Pharma US, INCYTE, Medimmune, Novartis. Aakash Desai has nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Kaufman HW, Chen Z, Niles J, Fesko Y. Changes in the number of US patients with newly identified cancer before and during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. JAMA Netw Open . 2020;3:e2017267–e2017267. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.17267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Elkrief A, Kazandjian S, Bouganim N. Changes in lung cancer treatment as a result of the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. JAMA Oncol . 2020. Sept 17 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Alhalabi O, Subbiah V. Managing cancer care during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond. Trends Cancer . 2020;6:533–535. doi: 10.1016/j.trecan.2020.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Food and Drug Administration. FDA guidance on conduct of clinical trials of medical products during COVID-19 public health emergency. 2020. https://www.fda.gov/media/136238/download Accessed October 2.

- 5.Unger JM, Vaidya R, Hershman DL, Minasian LM, Fleury ME. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the magnitude of structural, clinical, and physician and patient barriers to cancer clinical trial participation. J Natl Cancer Inst . 2019;111:245–255. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djy221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Upadhaya S, Yu JX, Oliva C, Hooton M, Hodge J, Hubbard-Lucey VM. Impact of COVID-19 on oncology clinical trials. Nat Rev Drug Discov . 2020;19:376–377. doi: 10.1038/d41573-020-00093-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alhalabi O, Iyer S, Subbiah V. Testing for COVID-19 in patients with cancer. EClinicalMedicine . 2020:100374. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Subbiah V. A global effort to understand the riddles of COVID-19 and cancer. Nat Cancer . 2020;1:943–994. doi: 10.1038/s43018-020-00129-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gupta D, Kato S, Kurzrock R. The impact of COVID-19 on cancer clinical trials conducted by NCI-designated comprehensive cancer centers. J Immunother Precis Oncol . 2021;4:56–63. doi: 10.36401/JIPO-20-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nabhan C, Choueiri TK, Mato AR. Rethinking clinical trials reform during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Oncol . 2020;6:1327–1329. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.3142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Doherty GJ, Goksu M, de Paula BH. Rethinking cancer clinical trials for COVID-19 and beyond. Nat Cancer . 2020;1:568–572. doi: 10.1038/s43018-020-0083-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jazieh AR, Chan SL, Curigliano G, et al. Delivering cancer care during the COVID-19 pandemic: recommendations and lessons learned from ASCO global webinars. JCO Glob Oncol . 2020. pp. 1461–1471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]