Abstract

The effect of gastrointestinal mucus on protease activity in Vibrio anguillarum was investigated. Protease activity was measured by using an azocasein hydrolysis assay. Cells grown to stationary phase in mucus (200 μg of mucus protein/ml) exhibited ninefold-greater protease activity than cells grown in Luria-Bertani broth plus 2% NaCl (LB20). Protease induction was examined with cells grown in LB20 and resuspended in mucus, LB20, nine-salts solution (NSS [a carbon-, nitrogen-, and phosphorus-free salt solution]), or marine minimal medium (3M) (∼109 CFU/ml). Induction of protease activity occurred 60 to 90 min after addition of mucus and was ≥70-fold greater than protease activity measured in cells incubated in either LB20 or 3M. Mucus was fractionated into aqueous and chloroform-methanol-soluble fractions. The aqueous fraction supported growth of V. anguillarum cells, but did not induce protease activity. The chloroform-methanol-soluble fraction did not support growth, nor did it induce protease activity. When the two fractions were mixed, protease activity was induced. The chloroform-methanol-soluble fraction did not induce protease activity in cells growing in LB20. EDTA (50 mM) inhibited the protease induced by mucus. Upon addition of divalent cations, Mg2+ (100 mM) was more effective than equimolar amounts of either Ca2+ or Zn2+ in restoring activity, suggesting that the mucus-inducible protease was a magnesium-dependent metalloprotease. An empA mutant strain of V. anguillarum did not exhibit protease activity after exposure to mucus, but did grow in mucus. Southern analysis and PCR amplification confirmed that V. anguillarum M93 contained empA. These data demonstrate that the empA metalloprotease of V. anguillarum is specifically induced by gastrointestinal mucus.

Vibrio anguillarum is the causative agent of vibriosis, one of the major bacterial diseases affecting fish, bivalves, and crustaceans (2, 5, 8). The distribution of vibriosis is worldwide, causing great economic loss to the aquaculture industry. Annual losses of cultured fish species in Japan alone exceed $30 million (2). Vibriosis is often the major limiting factor in the successful rearing of salmonids (2). V. anguillarum typically causes a hemorrhagic septicemia. Infected fish display skin discoloration and erythema around the base of the fins, vent, and mouth. Necrotic lesions form in the abdominal muscle. The gastrointestinal tract and rectum become distended and filled with fluid. Infected fish become lethargic and suffer heavy rates of mortality, ranging from 30 to 100% (2, 15, 25).

It has been suggested that infection of a fish host with V. anguillarum begins with the colonization of the posterior gastrointestinal tract and the rectum, because V. anguillarum was isolated from those sites during the initiation of infection (31, 32). Horne and Baxendale (14) demonstrated that V. anguillarum cells adhered to rainbow trout intestine. More recent work by Olsson et al. (30) indicates that the gastrointestinal tract is the major portal of entry for V. anguillarum infection of turbot. Additionally, Bordas et al. (7) have demonstrated that V. anguillarum exhibits strong chemotaxis toward intestinal mucus. Once V. anguillarum cells have colonized the fish gastrointestinal tract, they appear to penetrate the epithelium and cause a systemic infection. We have shown that V. anguillarum cells grow rapidly in Atlantic salmon gastrointestinal mucus and that growth in mucus results in the expression of at least five new membrane proteins, four of which are located in the outer membrane (13).

Extracellular proteases have been shown to be virulence factors for a variety of pathogenic bacteria, including Vibrio cholerae (6), Vibrio vulnificus (16), and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (28). For example, the V. cholerae metalloproteinase has been shown to nick and activate the A subunit of cholera enterotoxin (10), as well as degrade intestinal mucin and facilitate the action of cholera toxin (6), and the Vibrio vulnificus metalloprotease causes a hemorrhagic reaction by degrading type IV collagen in basement membranes (24). These proteases all share significant sequence homology with the empA-encoded metalloprotease of V. anguillarum (1, 27, 29), which has been suggested to be a possible virulence factor.

In this investigation, we examined the induction of protease activity in V. anguillarum under various conditions of incubation and growth. We showed that growth or incubation of V. anguillarum cells in salmon intestinal mucus rapidly and specifically induced protease activity. Chloroform-methanol fractions of mucus were examined for their ability to support the growth of V. anguillarum and to induce protease activity. The induced protease activity was shown to be a metalloprotease. Additionally, we showed by a combination of Southern hybridization analysis and PCR amplification that the metalloprotease was encoded by empA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

V. anguillarum M93 (a gift from Mitsuru Eguchi, Department of Fisheries, Kinki University, Nara, Japan) was isolated from a diseased ayu (Plecoglossus altivelis; Salmoniforms: Plecoglossidae) from Lake Biwa. V. anguillarum M93 is serotype J-O-1. V. anguillarum NB10 and NB12 Cmr (23) and Escherichia coli DH1 Cmr Tcr (pempA) (23) were gifts from Debra Milton (Department of Cell and Molecular Biology, Umea University, Umea, Sweden). Most experiments were carried out with the streptomycin-resistant mutant V. anguillarum M93Sm derived from V. anguillarum M93. All V. anguillarum strains were routinely grown in Luria-Bertani broth plus 2% NaCl (LB20) (13, 35), supplemented with the appropriate antibiotic, on a rotary shaker at 27°C. The experimental media included LB20, nine-salts solution (NSS [a carbon-, nitrogen-, and phosphorus-free salt solution]) (13, 21), marine minimal medium (3M) (13, 26), and NSS plus 200 μg of mucus protein/ml (NSSM) (13). Salmon gastrointestinal mucus was prepared as described below. Overnight cultures of V. anguillarum were grown in LB20 and centrifuged (9,000 × g, 10 min), and pelleted cells were washed twice with NSS (13). Washed cells were resuspended to the appropriate cell densities in experimental media. Specific conditions are described in the text for each experiment. Cell densities were determined by serial dilution and plating on LB20 agar plates or by measuring the optical density at 600 nm (OD600). Antibiotics were used at the following concentrations: tetracycline, 10 μg/ml; chloramphenicol, 5 μg/ml; and streptomycin, 200 μg/ml.

Detection and quantification of protease activity.

Protease activity of culture supernatants was determined by either of two methods. For semiquantitative determinations of protease activity, culture supernatants were assayed by observing zones of hydrolysis on 1% casein agar plates containing 2% NaCl (32). V. anguillarum M93 cells were grown overnight in LB20, 3M, and NSSM to the stationary phase or starved overnight in NSS (at 109 CFU/ml). Cells (109 CFU/ml) were aliquoted under experimental growth conditions and centrifuged at 12,000 × g (10 min, 20°C). The supernatant was removed and filtered through a 0.22-μm-pore-size cellulose-acetate filter to remove any remaining cells. Aliquots (10 μl) of the filtered culture supernatant were spotted onto the 1% casein agar plates in triplicate. Casein agar plates were incubated overnight at 27°C. The diameters of the zones of hydrolysis on the casein agar plates were measured (in millimeters). No colonies were observed in the areas of casein hydrolysis.

Culture supernatants were assayed for proteolytic activity by using a modification of the method described by Windle and Kelleher (36). Briefly, culture supernatant was incubated with azocasein (5 mg/ml) dissolved in Tris-HCl (50 mM [pH 8.0]) containing 0.04% NaN3. Culture supernatant was prepared by centrifuging 1 ml of cells (12,000 × g, 10 min). Supernatant was removed and filtered through a 0.22-μm-pore-size cellulose-acetate filter. Filtered supernatant (100 μl) was incubated at 30°C with 100 μl of azocasein solution. The azocasein reaction time was determined by performing assays on V. anguillarum M93 supernatants from all the experimental media. Incubations of 30 to 60 min were sufficient for assays of supernatants from cell suspensions of ≥5 × 108 cells/ml. Reactions were terminated by addition of trichloroacetic acid (10% [wt/vol]) to a final concentration of 6.7% (wt/vol). The mixture was allowed to stand for 1 to 2 min and centrifuged (12,000 × g, 4 min) to remove unreacted azocasein, and supernatant containing azopeptides was suspended in 700 μl of 525 mM NaOH (36). Absorbance of the azopeptide supernatant was measured at 442 nm with a Pharmacia Ultrospec 2000 spectrophotometer. A blank control was prepared by boiling V. anguillarum M93 supernatant (100°C, 10 min). Trichloroacetic acid was added to the blank control supernatant immediately after the addition of azocasein. The mucus used was also boiled (10 min) to destroy any inherent protease activity. Protease activity units were calculated with the equation 1 protease activity unit = [1,000 (OD442)/CFU] × (109).

Protease inhibition experiments.

V. anguillarum was grown in NSSM for 20 h. Culture supernatant was prepared as described above. In order to determine the effect of the removal of divalent cations upon protease activity, culture supernatant was incubated with 50 mM EDTA (final concentration) or an equivalent volume of water (control) for 60 min at 37°C and then assayed for protease by using azocasein (60-min incubation at 30°C). For reconstitution experiments, either 100 mM CaCl2, 100 mM MgCl2, or 100 mM ZnCl2 (final concentrations) was added to EDTA-treated or untreated control supernatants. The mixtures were allowed to incubate for 60 min at 37°C, and then protease activity was determined by the azocasein assay (60-min reaction time).

Preparation and extraction of mucus.

Gastrointestinal mucus was harvested from Atlantic salmon as previously described by Garcia et al. (13). Mucus was heat inactivated (100°C, 10 min) to destroy any inherent protease activity. Heat-inactivated mucus was extracted with 2:1 (vol/vol) chloroform-methanol. Equal volumes of mucus and chloroform-methanol were mixed and extracted for 30 s. Layers were allowed to separate, and the organic phase was removed. The aqueous layer was extracted twice more. The two mucus fractions were dried under nitrogen gas at 50°C. Mucus fraction samples were dried further under vacuum for 10 to 15 min. NSS was added to each fraction, restoring the initial volume of mucus extracted. The chloroform-methanol mucus extract fraction was sonicated briefly (∼4 s) to bring water-insoluble lipids into suspension. The concentration of protein in each mucus fraction was determined by a protein assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Richmond, Calif.).

Southern DNA transfer and hybridization analysis.

Total genomic DNA was extracted from V. anguillarum M93Sm and NB10 (3). DNA from each bacterial strain (4 μg) was digested to completion with PstI (Promega) according to the instructions of the manufacturer, and the fragments were separated by agarose gel electrophoresis (0.8% agarose gel, 80 V) in Tris-acetate-EDTA buffer (3). DNA samples were transferred from the agarose gel to a nylon membrane (MagnaGraph; MSI, Westboro, Mass.) for Southern hybridization analysis (3). The blot was probed with a digoxigenin (DIG)-dUTP-labeled probe (Boehringer Mannheim). The empA gene probe was constructed by purifying the pempA plasmid from E. coli DH1 by using a Promega Wizard plus miniprep DNA purification system (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The empA gene was PCR amplified with a Boehringer Mannheim DIG-PCR probe synthesis kit. A pempA sample (60 ng) was amplified with Taq polymerase (3.5 U/100 μl; Gibco BRL Life Technologies, Bethesda, Md.) on a Perkin-Elmer GeneAmp model 9600 thermocycler. The PCR cycle conditions were 94°C for 1 min, 51°C for 2 min, and 72°C for 3 min. The reaction was run for 35 cycles and then held at 4°C until the mixture was collected. Primers used for PCR amplification were derived from the empA gene sequence (23) as empA forward (5′-GCTATTCATGTACCGACGCG-3′) and empA reverse (5′-CGGAAGATTTGAAAATGTCGC-3′).

RESULTS

Protease activity in different growth media.

Protease activity of V. anguillarum was initially observed as hydrolysis of casein in agar plates. Supernatant (10 μl) from cells (1 × 109 to 2 × 109 CFU/ml) grown in mucus (200 μg of protein/ml) or LB20 yielded zones of clearing on casein agar plates that averaged 9.7 ± 0.6 mm and 5.3 ± 0.6 mm in diameter, respectively, after 24 h at 27°C. In contrast, supernatant from cells (1 × 109 to 2 × 109 CFU/ml) grown in 3M or starved in NSS (24 h) showed no hydrolysis. Mucus alone exhibited no protease activity. Since hydrolysis on casein plates could not be observed unless cells were at concentrations of 1 × 109 to 2 × 109 CFU/ml, and this method was slow and only semiquantitative, we used azocasein hydrolysis as a more rapid and quantitative assay for protease activity (36).

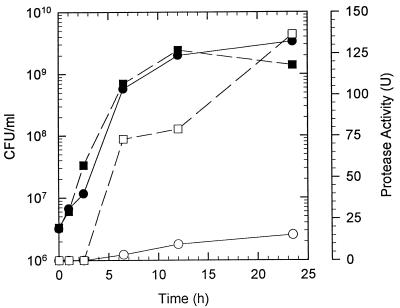

Levels of protease activity produced by V. anguillarum cells grown in either LB20 or NSSM were compared (Fig. 1). Protease activity was not observed until the cells reached the late-exponential to stationary phases. No protease activity could be detected in exponential-phase cells growing in either LB20 or NSSM, even when the protease assay time was greatly extended. Protease activity (∼73 U) was observed in mucus-grown cells as their density approached 109 CFU/ml. LB20-grown cells at a similar density produced only ∼5% (3.5 U) of the protease activity of the mucus-grown cells. Protease activity of both mucus- and LB20-grown cells increased during the stationary phase; however, mucus-grown cells had about ninefold-greater activity than LB20-grown stationary-phase cells at a similar density (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Protease activity during growth of V. anguillarum in LB20 or intestinal mucus. Cells grown overnight in LB20 were washed in NSS and used to inoculate either LB20 (circles) or NSSM (squares). At various times after inoculation, samples were taken for determination of CFU (solid symbols) or protease activity (open symbols).

Induction of protease activity by mucus.

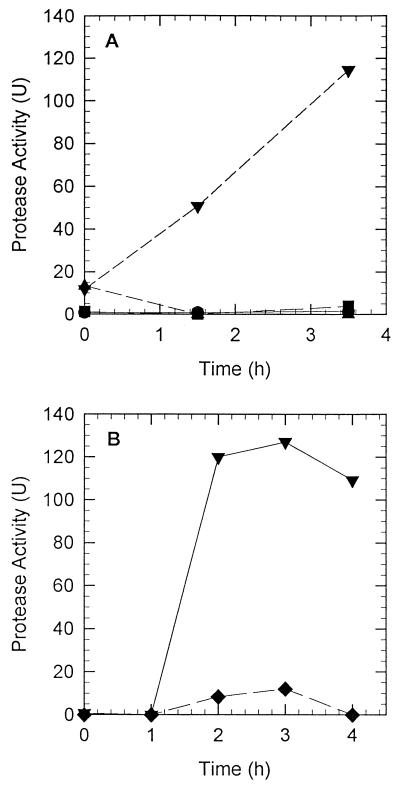

The results of growth experiments demonstrated that stationary-phase, mucus-grown cells were strongly induced to express a protease. In order to determine the rate of protease activity induction, V. anguillarum cells were grown overnight in LB20; washed twice in NSS; resuspended in either LB20, 3M, NSS, or NSSM at 1 × 109 to 2 × 109 CFU/ml; and allowed to incubate at 27°C. Samples were withdrawn and assayed for protease activity periodically. The data presented in Fig. 2 reveal that protease activity was induced in V. anguillarum cells within 90 min after exposure to mucus. Protease activity continued to increase over the following 2 h. Protease activity was not induced significantly in cells resuspended in LB20, 3M, or NSS for 3.5 h (Fig. 2A). The addition of chloramphenicol (200 μg/ml) to cultures resuspended in NSSM inhibited the induction of protease activity (Fig. 2B). Additionally, control experiments to determine protease activity in boiled mucus alone showed that even after 3 h of incubation, no protease activity could be observed (data not shown). Furthermore, the addition of boiled mucus to LB20 culture supernatants did not increase or activate protease activity.

FIG. 2.

Induction of protease activity in V. anguillarum cells incubated in LB20, 3M, NSS, or NSSM. (A) Cells were grown in LB20 overnight, washed twice in NSS, and resuspended at ∼109 CFU/ml in LB20 (●), 3M (■), NSS (▴), or NSSM (▾). The three non-mucus-containing environments resulted in negligible protease activity. (B) Effect of the addition of chloramphenicol (200 μg/ml) on the induction of protease activity by mucus. Cells prepared as described above for panel A were resuspended in NSSM (▾) or NSSM plus chloramphenicol (⧫). Samples were assayed at various times for protease activity.

Determination of metalloprotease activity.

Previous studies by Farrell and Crosa (11) and Norqvist et al. (29) demonstrated that V. anguillarum produces a metalloprotease. We sought to determine whether exposure to mucus induced a similar metalloprotease activity in V. anguillarum M93. Culture supernatant was obtained from V. anguillarum cells grown in NSSM (20 h at 27°C) to induce protease activity. Supernatants from 20-h cultures were incubated in the presence and absence of 50 mM EDTA. The results of the azocasein assay showed that 50 mM EDTA completely inhibited protease activity (Table 1) and suggested that V. anguillarum expressed a metalloprotease when induced with mucus.

TABLE 1.

Effects of EDTA and divalent cation addition on V. anguillarum protease activity

| Sample treatmenta | No. of protease activity units (% of control)b |

|---|---|

| Water | 166 (100) |

| 50 mM EDTA | 0 (0) |

| 50 mM EDTA + 100 mM Ca2+ | 28 (17) |

| 50 mM EDTA + 100 mM Mg2+ | 139 (83) |

| 50 mM EDTA + 100 mM Zn2+ | 90 (54) |

| 100 mM Ca2+ | 201 (121) |

| 100 mM Mg2+ | 360 (217) |

| 100 mM Zn2+ | 113 (68) |

Culture supernatants were obtained from cells grown overnight in NSSM as described in Materials and Methods. To each supernatant sample, an equal volume of water (control) or a solution containing EDTA and/or a divalent metal was added to give the appropriate final concentrations.

Protease activities were measured and calculated as described in Materials and Methods.

Three different metal ions (Mg2+, Ca2+, and Zn2+) were tested for their ability to reverse EDTA inhibition of protease activity (Table 1). Protease activity was restored best by the addition of 100 mM Mg2+ (83% of that of the untreated control). The addition of 100 mM Zn2+ or 100 mM Ca2+ only restored activity to 54 and 17% of the control level, respectively. The addition of 100 mM Mg2+ to culture supernatants, in the absence of EDTA, increased protease activity to >200% of that of the control (Table 1). The addition of either 100 mM Ca2+ or Zn2+ to culture supernatants had insignificant effects on protease activity (Table 1). These data suggest that V. anguillarum secretes a magnesium-dependent metalloprotease when grown in mucus.

Growth and protease induction in mucus fractions.

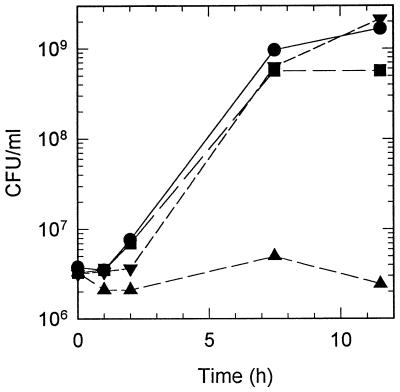

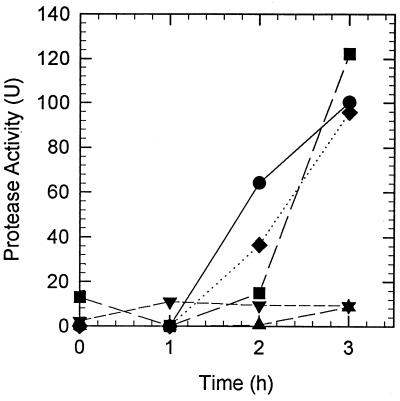

Mucus was fractionated to determine what component induced growth and protease activity in V. anguillarum. Mucus was extracted with chloroform-methanol (2:1 [vol/vol]) to yield an aqueous-phase chloroform-methanol-extracted mucus and a lipid-containing chloroform-methanol-soluble mucus extract. V. anguillarum M93 cells grew in chloroform-methanol-extracted mucus at the same rate as in unextracted mucus, but reached stationary phase at densities about one-third of those observed in mucus (Fig. 3). Both chloroform-methanol-extracted mucus and unextracted mucus had equal protein concentrations (∼100 μg/ml). No protein was present in the chloroform-methanol-soluble mucus extract. No significant growth was observed in the chloroform-methanol-soluble mucus extract fraction (Fig. 3). When both fractions were mixed together, growth occurred at the same rate and reached stationary phase at the same concentration of cells as seen in unextracted mucus. Protease activity was not induced in cells incubated in either the chloroform-methanol-extracted mucus or the chloroform-methanol-soluble mucus extract fraction alone (Fig. 4). However, when both fractions were mixed together, protease induction resembled that of unextracted mucus. Furthermore, when chloroform-methanol-soluble mucus extract was added to a suspension of cells that had been incubated for 1 h in chloroform-methanol-extracted mucus, protease activity was induced and increased more rapidly than in a control suspension of cells incubated in unextracted mucus (Fig. 4). To determine whether the lipid-containing chloroform-methanol-soluble mucus extract could induce protease activity in growing cells, V. anguillarum cells were incubated in LB20 plus mucus extract. No protease activity was induced during the 3-h incubation (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

Growth of V. anguillarum in mucus fractions. Cells grown overnight in LB20 were washed twice in NSS and resuspended in mucus (●), chloroform-methanol-extracted mucus (■), chloroform-methanol mucus extract (▴), or extracted mucus plus chloroform-methanol mucus extract (▾). The cultures were incubated at 27°C with shaking, and samples were taken periodically for the determination of CFU. Mucus fractionation was carried out as described in Materials and Methods.

FIG. 4.

Induction of protease activity in V. anguillarum by mucus fractions. Mucus was extracted with chloroform-methanol (2:1 [vol/vol]) as described in Materials and Methods to yield water-soluble-extracted mucus (▴) and chloroform-methanol-soluble mucus extract (▾). V. anguillarum cells were grown overnight in LB20, harvested by centrifugation, washed twice in NSS, and resuspended (1 × 109 to 2 × 109 CFU/ml) in either whole mucus (●), extracted mucus (▴), mucus extract (▾), extracted mucus plus mucus extract (⧫), or extracted mucus with mucus extract added 1 h after the start of the experiment (■). Protease activity was measured as described in Materials and Methods.

Southern analysis with the empA gene probe.

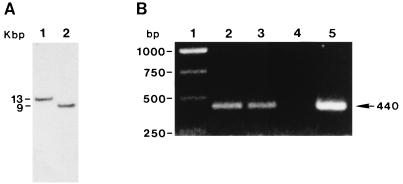

A DNA gene probe was generated from the empA gene by using DIG-PCR (see Materials and Methods). Primers were developed by using the empA gene sequence. Genomic DNA samples from V. anguillarum M93Sm and NB10 were each digested with the restriction endonuclease PstI. Southern analysis of genomic DNA from M93Sm and NB10 showed hybridizable fragments of 13 and 9 kb, respectively (Fig. 5A). PCR analysis with primers for the empA gene yielded the predicted gene product of 440 bp in length for both M93Sm and NB10, as well as the pempA control (Fig. 5B). The data demonstrate that M93Sm contains the empA metalloprotease gene.

FIG. 5.

Demonstration of the presence of empA in V. anguillarum M93Sm by Southern blot hybridization (A) and PCR (B). (A) DNA from V. anguillarum M93Sm (lane 1) and NB10 (lane 2) was digested with PstI, separated on a 0.8% agarose gel, transferred to a nylon membrane, and probed with DIG-dUTP-labeled empA probe as described in Materials and Methods. DNA size markers (kilobase pairs) are shown to the left. (B) DNA from strains M93Sm (lane 2), NB10 (lane 3), and the plasmid pempA (lane 5) was PCR amplified with empA primers as described in Materials and Methods. Lane 4 is a negative control with no DNA added, and lane 1 shows DNA size markers.

In order to determine whether the empA gene was induced by mucus, protease activities in V. anguillarum strains known to contain a functional empA gene (NB10 and M93Sm) and an empA mutant strain (NB12) were assayed and compared during incubation in mucus. The data in Table 2 show that protease activity was strongly induced in both wild-type strains. In contrast, no protease activity was induced in the empA mutant strain. These data strongly suggest that empA is specifically induced in mucus and that the empA gene product accounts for all of the protease activity observed in cells incubated in mucus.

TABLE 2.

Induction of protease activity in wild-type and empA mutant strains of V. anguillarum by the addition of mucusa

| V. anguillarum strain | Protease activity (U)b

|

|

|---|---|---|

| 0 h | 4 h | |

| M93 | 6.0 | 160 |

| NB10 | 5.8 | 170.6 |

| NB12 | 0 | 3.7 |

Cells were grown, prepared, and assayed for protease activity as described in Materials and Methods.

Protease activity was determined immediately after the addition of mucus to cell suspensions (T = 0 h) and 4 h later.

Since both V. anguillarum strains containing the wild-type empA gene showed a strong and rapid induction of protease in mucus and the empA mutant, NB12, failed to show any protease activity when incubated in mucus, we asked whether protease was necessary for growth in mucus. V. anguillarum M93Sm, NB10, and NB12 were each inoculated into NSSM broth with starting concentrations of approximately 106 CFU/ml and allowed to incubate at 27°C with shaking. The cell density of each culture was determined at various times for 24 h. Both wild-type strains (M93Sm and NB10) and the empA mutant strain (NB12) grew rapidly and reached maximum cell density (≥2 × 109 CFU/ml) by 12 h. These observations demonstrate that the empA-encoded protease is not required for growth in mucus.

DISCUSSION

It has been demonstrated that the gastrointestinal tract of fish is a major portal of entry for V. anguillarum (30). Garcia et al. (13) have shown that salmon intestinal mucus is an excellent nutrient source for the growth of V. anguillarum and that during growth in mucus, a number of proteins are induced. In this report, we present data which demonstrate that extracellular protease activity is specifically induced by the growth or incubation of V. anguillarum cells in salmon intestinal mucus. Additionally, we show that while V. anguillarum cells grow on chloroform-methanol-extracted mucus and do not grow on the chloroform-methanol-soluble extract, induction of protease activity requires both fractions. We also demonstrate that the protease activity induced by mucus is the metalloprotease encoded by empA. Finally, we show that despite the strong and rapid induction of protease activity during incubation in mucus, an empA mutant is able to grow at the same rate and to the same cell density in mucus as wild-type strains. To our knowledge, this is the first demonstration of metalloprotease induction by intestinal mucus.

It is interesting that while V. anguillarum grows well in aqueous-phase chloroform-methanol-extracted mucus and does not grow on the chloroform-methanol-soluble extract, protease induction requires whole mucus. Neither chloroform-methanol fraction of mucus alone induces protease activity. However, when the two fractions are mixed prior to the addition of cells, both the rate of protease induction and the amount of activity are nearly indistinguishable from what is observed in cells incubated in whole, unfractionated mucus. Furthermore, the addition of the chloroform-methanol-soluble fraction of mucus to cells incubated for 1 h in chloroform-methanol-extracted mucus induces protease activity more rapidly than in cells incubated in whole mucus. Additionally, the chloroform-methanol-soluble fraction of mucus does not induce protease activity in cells growing in media other than mucus. These data suggest that there is a specific inducing agent or agents within the mucus. These data also confirm our observation that while protease activity is induced in whole mucus, the protease is not required for growth in mucus.

Krivan et al. (17) demonstrated that phosphatidylserine serves as the sole source of carbon and nitrogen for Salmonella typhimurium when growing in mouse intestinal mucus. Additionally, while E. coli can also use phosphatidylserine as the sole source of carbon and nitrogen when growing in mouse intestinal mucus (17), gluconate appears to be preferentially utilized during colonization of the mouse large intestine (34). Our observations that V. anguillarum does not grow on the chloroform-methanol-soluble mucus extract, but does grow on the chloroform-methanol-extracted mucus, suggest that V. anguillarum does not use phosphatidylserine. We do not know whether gluconate is utilized by V. anguillarum during growth in mucus. These observations support the idea that the mucus environment contains several nutritional niches, each capable of supporting the growth of different microorganisms (12, 18).

Other investigators have indicated that protease activity in V. anguillarum (29) and other Vibrio species (9, 19) increases during stationary phase. As a result, a standard method of enrichment for protease is to harvest the culture supernatant from stationary-phase cells. While we also find that protease activity increases during stationary phase, cells grown to stationary phase in mucus produced at least ninefold more protease than did cells grown to stationary phase in LB20 (Fig. 1). This difference was even more pronounced in cells transferred at high density to mucus, LB20, 3M, or NSS and incubated for up to 3 h (Fig. 2). In those experiments, induction of protease activity in mucus was 30- to 100-fold greater than in the other media.

Melton-Celsa et al. (22) observed that mouse and human intestinal mucus activate Shiga-like toxins produced by enterohemorrhagic E. coli O91:H21. This observation raised the possibility that fish mucus could contain an activity that activated preexisting, but inactive protease in V. anguillarum. We find that when the supernatant from LB20-grown cells is incubated with boiled mucus, there is no activation of protease activity. We conclude that under the conditions employed in this study, boiled mucus acts as an inducer of protease activity and not as an activator of preexisting, but inactive protease.

It has been hypothesized that secreted proteases may serve as colonization or virulence factors for various pathogenic bacteria that live in mucus-containing environments, such as the gastrointestinal tract and the lung (10, 27, 33). For example the metalloprotease of Vibrio vulnificus (24), Hap protease of Vibrio cholerae (10), elastase of Pseudomonas aeruginosa (28), and protease of Legionella pneumophila (4) have all been shown to be important virulence factors. Additionally, these proteases all share significant sequence similarity with the empA metalloprotease of V. anguillarum (1, 27, 29). However, it has not been clearly established that the empA protease serves as a virulence of colonization factor for V. anguillarum. Milton et al. (23) showed that V. anguillarum mutants lacking a functional empA gene exhibit only a modest reduction in virulence when introduced into fish by immersion. They suggested that other proteases might compensate for the loss of the empA protease (23). However, the results reported here do not indicate the presence of other protease activities when empA mutant cells are incubated in mucus. It should be pointed out that P. aeruginosa mutants lacking either a functional alkaline protease or a functional elastase also show only a modest decline in virulence in the burned mouse model (28). Thus, Nicas and Iglewski (28) suggest that virulence in P. aeruginosa is multifactorial and that the relative contribution of a given gene product may vary with the type of infection. Furthermore, it has been suggested (10) that the V. cholerae metalloprotease degrades intestinal mucin by allowing increased access to mucosal Gm1 receptor sites by cholera toxin. This suggests that protease may facilitate virulence, but the loss of this activity may not cause avirulence. A similar argument may be made for the role of the V. anguillarum metalloprotease. Since our data demonstrate that the protease is rapidly induced by incubation in mucus, it could be hypothesized that protease activity helps to promote colonization of the intestine and pathogenesis, but is not required for virulence.

Recently, Lory et al. (20) showed that interaction of P. aeruginosa with cystic fibrosis patient mucus resulted in the induction of expression for several genes, including a lipopolysaccharide biosynthesis gene and a gene encoding a protein responsible for the uptake of the ferric pyochelin siderophore. These observations, coupled with our findings, suggest that growth in mucus not only allows for the amplification of the pathogen, but also allows for the induction of activities necessary for successful colonization and invasion of the host.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by USDA NRICGP grant 97-35204-4811 awarded to D.R.N.

We thank Debra Milton and Mitsuru Eguchi for their generous gifts of V. anguillarum strains and plasmids. We also thank Paul Johnson for excellent photographic services.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul S F, Madden T L, Schaffer A A, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman D J. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Austin B, Austin D A. 2nd ed. Diseases in farmed and wild fish. Ellis Horwood, Ltd., Chichester, United Kingdom. 1993. Bacterial fish pathogens. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ausubel F M, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K, editors. Current protocols in molecular biology. New York, N.Y: Wiley; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Black W J, Quinn F D, Tompkins L S. Legionella pneumophila zinc metalloprotease is structurally and functionally homologous to Pseudomonas aeruginosa elastase. J Bacteriol. 1989;172:2608–2613. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.5.2608-2613.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bolinches J, Toranzo A E, Silva A, Barja J L. Vibriosis as the main causative factor of heavy mortalities in the oyster culture industry in northwestern Spain. Bull Eur Assoc Fish Pathol. 1986;6:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Booth B A, Boesman-Finkelstein M, Finkelstein R A. Vibrio cholerae soluble hemagglutinin/protease is a metalloenzyme. Infect Immun. 1984;42:639–644. doi: 10.1128/iai.42.2.639-644.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bordas M A, Balebona M C, Rodriguez-Maroto J M, Borrego J J, Moriñigo M A. Chemotaxis of pathogenic Vibrio strains towards mucus surfaces of gilt-head sea bream (Sparus aurata L.) Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:1573–1575. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.4.1573-1575.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bowser P R, Rosemark R, Reiner C. A preliminary report of vibriosis in cultured American lobster, Homarus americanus. J Invertebr Pathol. 1981;37:80–85. doi: 10.1016/0022-2011(81)90058-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chuang Y C, Chang T M, Chang M C. Cloning and characterization of the gene (empV) encoding extracellular metalloprotease from Vibrio vulnificus. Gene. 1997;189:163–168. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(96)00786-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crowther R S, Roomi N W, Fahim R E, Forstner J F. Vibrio cholerae metalloproteinase degrades intestinal mucin and facilitates enterotoxin-induced secretion from rat intestine. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1987;924:393–402. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(87)90153-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Farrell D H, Crosa J H. Purification and characterization of a secreted protease from the pathogenic marine bacterium Vibrio anguillarum. Biochemistry. 1991;30:3432–3436. doi: 10.1021/bi00228a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Freter R, Brickner H, Botney M, Cleven D, Aranki A. Mechanisms that control bacterial populations in continuous-flow culture models of mouse large intestinal flora. Infect Immun. 1983;39:676–685. doi: 10.1128/iai.39.2.676-685.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garcia T, Otto K, Kjelleberg S, Nelson D R. Growth of Vibrio anguillarum in salmon intestinal mucus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:1034–1039. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.3.1034-1039.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Horne M T, Baxendale A. The adhesion of Vibrio anguillarum to host tissues and its role in pathogenesis. J Fish Dis. 1983;6:461–471. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Horne M T, Richards R H, Roberts R J, Smith P C. Peracute vibriosis in juvenile turbot Scophthalmus maximus. J Fish Pathol. 1977;11:355–361. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kothary M H, Kreger A S. Purification and characterization of an elastolytic protease of Vibrio vulnificus. J Gen Microbiol. 1987;133:1783–1791. doi: 10.1099/00221287-133-7-1783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krivan H C, Franklin D P, Wang W, Laux D C, Cohen P S. Phosphatidylserine found in the intestinal mucus serves as a sole source of carbon and nitrogen for salmonellae and Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1992;60:3943–3946. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.9.3943-3946.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee A. Neglected niches. The microbial ecology of the gastrointestinal tract. Adv Microb Ecol. 1985;8:115–162. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Long S, Mothibeli M A, Robb F T, Woods D R. Regulation of extracellular alkaline protease activity by histidine in a collagenolytic Vibrio alginolyticus strain. J Gen Microbiol. 1981;127:193–199. doi: 10.1099/00221287-127-1-193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lory S, Jin S, Boyd J M, Rakeman J L, Bergman P. Differential gene expression by Pseudomonas aeruginosa during interaction with respiratory mucus. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;154:S183–S186. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/154.4_Pt_2.S183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marden P, Tunlid A, Malmcrona-Friberg K, Odham G, Kjelleberg S. Physiological and morphological changes during short term starvation of marine bacteriological isolates. Arch Microbiol. 1985;142:326–332. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Melton-Celsa A R, Darnell S C, O’Brien A D. Activation of Shiga-like toxins by mouse and human intestinal mucus correlates with virulence of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O91:H21 isolates in orally infected, streptomycin-treated mice. Infect Immun. 1996;64:1569–1576. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.5.1569-1576.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Milton D L, Norqvist A, Wolf-Watz H. Cloning of a metalloprotease gene involved in the virulence mechanism of Vibrio anguillarum. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:7235–7244. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.22.7235-7244.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miyoshi S-I, Nakazawa H, Kawata K, Tomochika K-I, Tobe K, Shinoda S. Characterization of the hemorrhagic reaction caused by Vibrio vulnificus metalloprotease, a member of the thermolysin family. Infect Immun. 1998;66:4851–4855. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.10.4851-4855.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Munn C B. Vibriosis in fish and its control. Fish Management. 1977;8:11–15. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Neidhardt F C, Bloch P L, Smith D F. Culture medium for enterobacteria. J Bacteriol. 1974;119:736–747. doi: 10.1128/jb.119.3.736-747.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nelson, D. R. Unpublished results.

- 28.Nicas T I, Iglewski B H. The contribution of exoproducts to virulence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Can J Microbiol. 1985;31:387–392. doi: 10.1139/m85-074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Norqvist A, Norrman B, Wolf-Watz H. Identification and characterization of a zinc metalloprotease associated with invasion by the fish pathogen Vibrio anguillarum. Infect Immun. 1990;58:3731–3736. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.11.3731-3736.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Olsson J C, Jöborn A, Westerdahl A, Blomberg L, Kjelleberg S, Conway P L. Is the turbot, Sophthalmus maximus (L.), intestine a portal of entry for the fish pathogen Vibrio anguillarum? J Fish Dis. 1996;19:225–234. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ransom D P. Bacteriologic, immunologic and pathologic studies of Vibrio sp. pathogenic to salmonids. Ph.D. thesis. Corvallis: Oregon State University; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ransom D P, Lannan C N, Rohovecm J S, Fryer J L. Comparison of histopathology caused by Vibrio anguillarum and Vibrio ordalii in three species of Pacific salmon. J Fish Dis. 1984;7:107–115. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith A W, Chahal B, French G L. The human gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori has a gene encoding an enzyme first classified as a mucinase in Vibrio cholerae. Mol Microbiol. 1994;13:153–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00410.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sweeney N J, Laux D C, Cohen P S. Escherichia coli F-18 and E. coli K-12 eda mutants do not colonize the streptomycin-treated mouse large intestine. Infect Immun. 1996;64:3504–3511. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.9.3504-3511.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vaantanen P. Microbiological studies in coastal waters of the northern Baltic Sea. I. Distribution and abundance of bacteria and yeasts in the Tvarminne area. Walter Ander Nottbeck Found Sci Rep. 1976;1:1–58. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Windle H J P, Kelleher D. Identification and characterization of a metalloprotease activity from Helicobacter pylori. Infect Immun. 1997;65:3132–3137. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.8.3132-3137.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]