Abstract

Paronychia refers to the inflammation of the tissue which immediately surrounds the nail and it can be acute (<6 weeks duration) or chronic (>6 weeks duration). Disruption of the protective barrier between the nail plate and the adjacent nail fold preceded by infectious or noninfectious etiologies results in the development of paronychia. A combination of general protective measures, and medical and/or surgical interventions are required for management. This review explores the pathogenesis, clinical features, differential diagnosis, medical, and surgical management of paronychia. For the purpose of this review, we searched the PubMed, Cochrane, and Scopus databases using the following keywords, titles, and medical subject headings (MeSH): acute paronychia, chronic paronychia, and paronychial surgeries. Relevant review articles, original articles, and case reports/series published till February 2020 were included in this study.

Keywords: Acute, approach, chronic, paronychia, surgeries

INTRODUCTION

Paronychia refers to the inflammation of the tissue, which immediately surrounds the nail and it can be acute

(<6 weeks duration) or chronic (>6 weeks duration).[1] Disruption of the protective barrier between the nail plate and the adjacent nail fold preceded by infectious or noninfectious etiologies results in the development of paronychia. A combination of general protective measures, medical, and/or surgical interventions are required for management.[1,2] This review explores the pathogenesis, clinical features, differential diagnosis, and medical and surgical management of paronychia. For the purpose of this review, we searched the PubMed, Cochrane, and Scopus databases using the following keywords, titles, and medical subject headings (MeSH): acute paronychia (AP), chronic paronychia (CP), and paronychial surgeries. Relevant review articles, original articles, and case reports/series published till February 2020 were included in this article.

RELEVANT ANATOMY

The nail bed comprises the proximal germinal matrix which gives rise to the new nail, whereas the distal sterile matrix adds volume and strength.[3,4] The paronychium constitutes the soft tissue lateral to the nail bed, whereas perionychium is the paronychium plus the nail bed.[2] The hyponychium is formed at the point where the distal nail bed meets the skin of the fingertip. The proximal nail fold (PNF) is an anatomic transition between the nail bed and the paronychium. Present at the most distal portion of the PNF, at the point of its attachment to the nail plate lies the cuticle or the eponychium, an outgrowth of the PNF and the nail vest, a thin veil of tissue forms at this junction.[2,4] This layout thus forms an efficient barrier to exogenous stimuli and its destruction heralds the onset of paronychia.[4]

ACUTE PARONYCHIA

Definition

This is an acute-onset (less than 6 weeks) inflammation of the tissue immediately surrounding the nail, most commonly occurring as a result of bacterial infection.

Epidemiology

It is considered to be one of the most common hand infections and a female predominance has been reported with a female to male ratio of 3:1.[1]

Pathogenesis

Predisposing factors

The most common initiating factor for fingernail paronychia is nail trauma, often related to onychophagia, manicures, household wet-work, or retention of a foreign body associated with penetrating trauma.[2] AP of the toes occurs in most cases in association with ingrown toenails or onychocryptosis.

Etiology

Infectious causes

AP is commonly caused by inoculation of the organisms present in the skin flora, such as Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes into the nail folds, following the inciting trauma and subsequent disruption of the protective fingertip barrier.[5] Other aerobic bacteria such as gamma-hemolytic streptococci and Klebsiella pneumoniae constitute roughly 25% of the cases, whereas anaerobic organisms account for another 25%. Contact with oral secretions may predispose the digits to inoculation by either the skin flora or the oral flora, including aerobic bacteria such as Eikenella corrodens and anaerobic bacteria (e.g., Fusobacterium, Peptostreptococcus, Prevotella, and Porphyromonas spp.).[5] Contact with livestock may predispose to the acquisition of Pasteurella multocida.[2]Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Coliforms, and Proteus vulgaris have also been isolated.[2,6] Pseudomonas may be identified by a greenish discoloration of the nail bed.[7] Nonbacterial causative pathogens are uncommon causes and include Candida albicans and herpes simplex virus.[2]

Noninfectious causes

Pemphigus vulgaris, pustular psoriasis, and reactive arthritis may also present as AP.[2,8,9] Certain drugs have also been implicated in causing AP, within 1–3 months after treatment initiation, including epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) inhibitors, cytotoxic chemotherapeutic agents (taxanes, doxorubicin, methotrexate, capecitabine), systemic retinoids, and antiretroviral drugs.[10,11,12,13]

Clinical presentation

Patients present 2–5 days after the initiating cause, with acute onset erythema, edema, pain, and tenderness along the lateral and/or PNFs, generally involving a single digit[9,14] [Figure 1A]. Application of pressure along the nail fold may lead to the exudation of purulent material.[15,16] At times pustules, or a frank abscess [Figure 1B] may be seen and a “collar-stud” abscess may form if it connects with the underlying tissues and such deep-seated infection may damage the nail matrix.[14]

Figure 1.

(A) Acute paronychia presenting as erythema, swelling and pus discharge along the lateral and proximal nail fold. (B) Acute paronychia of the thumb with abscess formation

Paronychia associated with psoriasis, Reiter syndrome, and pemphigus may involve multiple digits and the presence of characteristic nail changes is also useful pointers.[2,9,17] Involvement of the periungual tissue in secondary syphilis or congenital syphilis may mimic acute bacterial paronychia, but is more gradual in onset and less painful.[18] Drug-induced AP may involve several digits and a temporal correlation helps in establishing the cause.[2] Furthermore, malignancies of the nail unit (such as glomus tumor), periungual region, metastasis, and paraneoplastic conditions may present as AP.[2] Recently, a case presenting with AP was diagnosed with subungual keratoacanthoma, a rare variant of keratoacanthoma.[19]

Differential diagnosis

Herpetic whitlow presents as painful grouped vesicopustules on an erythematous base which gradually coalesce into large-honeycomb-like bullae; however, frank pus-discharge is never seen. It should be considered in children who suck their thumbs leading to viral autoinoculation, healthcare providers, as well as following genital herpes exposure.[15,20] Incision and drainage are contraindicated and tzanck smear and/or culture are pivotal in diagnosis.[2,5,15]

Diagnosis

A detailed history regarding the risk factors, onset, site, progression, and physical examination is necessary. Routine culture from expressed fluid or drained pus is not recommended, as the results are commonly nondiagnostic.[21,22,23] Ultrasonography (USG) reveals a diffuse thickening of the periungual fold, and can help delineate an abscess or cellulitis when it is not clinically evident.[24]

The digital pressure test is performed by asking the patient to oppose the thumb and index finger, thereby applying light pressure over the distal volar aspect of the affected digit. If an abscess is present, a well-demarcated area of blanching is seen.[25]

Management

Management of AP may be nonsurgical or surgical depending upon the extent and/or severity of inflammation and presence of an abscess.[2,23]

Nonsurgical management

If diagnosed in the initial stages, AP without an abscess can be treated nonsurgically as described in Table 1. A substantial amount of inflammation, early abscess, or immunocompromised states warrant the initiation of systemic antibiotics[5,29,30] [Tables 2 and 3].

Table 1.

Medical management of acute paronychia

| Extent of inflammation | Abscess | Treatment | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Step1 | Minimal inflammation with no overt cellulitis | Absent | Warm water soaks (3–4 times a day) + either of[1,26,27] • Burrow’s solution (aluminum acetate) • Vinegar (acetic acid) • Diluted povidone iodine • Chlorhexidine |

| Step2 | Minimal inflammation with no response to Step 1 | Absent | Add Topical antibiotic ± topical corticosteroida[28] • Mupirocin (2 to 4 times daily for 5–10 days) • Gentamicin (3 to 4 times daily for 5–10 days) • Bacitracin/polymyxin B (3 times a day for 5–10 days) • Topical fluoroquinolone (if pseudomonal infection is suspected) |

| Step3 | • Substantial erythema/inflammation/ • Overt cellulitis • Immunocompromised patients • Severely ill patients | Absent | Add Systemic antibiotic[5,29,30] • Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazoleb • Cephalexin • Amoxicillin + clavulanic acidc • Clindamycind |

aAddition of topical steroids decreases the time to symptom resolution without additional risks[23]

bProvides coverage against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus

cRecommended when exposure to oral flora is suspected

dProvides anti-anaerobic coverage

Table 2.

Recommendations for antibiotic use in acute paronychia

| Recommendations for use of antibiotics in acute paronychia-pearls |

|---|

| • The use of oral antibiotics in acute paronychia should be cautious/limited.[21,22] |

| • Patients with overt cellulitis and possibly those who are immunocompromised or severely ill may warrant use of oral antibiotics.[29,30] |

| • Antibiotic therapy should be directed against the most likely pathogens (staphylococcal and streptococcal species)[29,30] |

| • If there are risk factors for oral pathogens, such as thumb-sucking or nail biting, medications with adequate anaerobic coverage should be given.[29,30] |

| • Local community resistance patterns should be considered when choosing specific agents.[31] |

| • Antibiotics are generally not needed after successful abscess drainage as the addition of systemic antibiotics does not improve cure rates after incision and drainage of cutaneous abscesses.[32] |

| • In case of pseudomonal infection, use of systemic fluoroquinolones, topical ciprofloxacin, gentamicin, silver sulfadiazine, bacitracin and polymyxin B is recommended.[33] |

Table 3.

| Pathogen | Genus | Antibiotic options | Dosage | Duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gram negative aerobes | Fusobacterium | Amoxicillin + clavulanic acid clindamycin fluroquinolones (ciprofloxacin) | 500 mg/125 mg TDS 150–450 mg TDS or QID 500 mg BD | 7 days 7 days |

| Pseudomonas | Ciprofloxacin | 500 mg BD | 7–14 days | |

| Gram-negative anaerobe | Bacteroides | Amoxicillin/clavulanate, Clindamycin, Fluoroquinolones | 500 mg/125 mg TDS 150–450 mg TDS or QID | 7 days 7 days |

| Gram-negative facultative anaerobes | Eikenella | Cefoxitin | 1–2 g 6–8 hourly IV | 7 days |

| Enterococcus | Amoxicillin + clavulanate | 500 mg/125 mg TDS | 7 days | |

| Klebsiella | Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, fluroquinolones | 160 mg/800 mg orally BD | 7days | |

| Proteus | Amoxicillin + clavulanate, Fluroquinolones (ciprofloxacin) | 500 mg/125 mg TDS 500 mg BD | 7 days | |

| Gram-positive aerobes | Staphylococcus | Cephalexin | 250–500 mg QID | 7 days |

| MRSA | Clindamycin, Doxycycline, Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole | 150–450 mg TDS or QID 100 mg BD 160 mg/800 mg orally BD | 7 days 7 days | |

| Streptococcus | Cephalexin | 250–500 mg QID | 7 days |

Complications

Subungual abscess, cellulitis, osteomyelitis, nail plate elevation, and dystrophy are uncommon complications of AP.[5,9,14,17] Rarely, an acquired periungual fibrokeratoma [Figure 2] may develop.[34] The course of AP may be further complicated by recurrences and chronicity. Furthermore, severe infection, diabetes, or other causes of immunosuppression may lead to impaired response to treatment.[2]

Figure 2.

Acquired periungual fibrokeratoma: complication of acute paronychia

CHRONIC PARONYCHIA

Definition

CP is a recalcitrant dermatosis of more than 6 weeks duration, characterized by the inflammation (with or without infection) of the tissue surrounding the nail.[2,4,23]

Pathogenesis

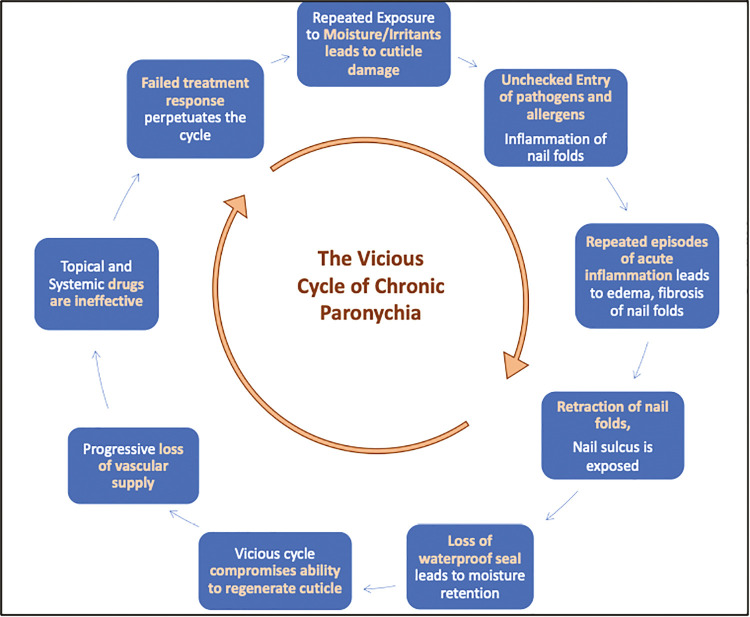

CP is now deemed to be a form of hand eczema where exposure to environmental allergens plays a pivotal role, whereas colonization of the nail sulcus with candida, occurs only secondarily.[4,11,35,36] Recurring episodes of acute inflammation lead to fibrosis of PNF and LNF, causing them to retract, further exposing the nail sulcus.[2,4] As this vicious sequence continues, the capacity to restore the cuticle diminishes and a progressive impairment of the vascular supply of the inflamed and fibrosed PNF ensues[4,37] [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

Pathogenesis of CP-CP is form of hand dermatitis with secondary (bacterial/fungal) colonization. Repeated exposure to moisture and irritants leads to damage to the cuticle, causing unchecked entry of allergens as well as pathogens leading to repeated episodes of acute inflammation resulting in edema, fibrosis and consequent retraction of the nail folds. The nail sulcus is thus, further exposed compromising the effective seal again resulting in the unchecked entry of organisms/allergens. This vicious cycle impedes the cuticle regeneration. In addition, the fibrosis as well as progressive loss of vascular supply prevents topical and systemic drugs from reaching the nail folds. Thus, a failed treatment response perpetuates this cycle

Etiology and risk factors

Occupations associated with repeated exposure to moisture, irritants as well as allergens are seen in homemakers, bartenders, cooks, and health-care professionals, and constitute the most common etiological factor. Diabetes mellitus, HIV infection, and other causes of immunosuppression increase the risk of secondary colonization.[2,4,38] Uncommon causes include infections such as bacterial, fungal (e.g., Candida albicans), and viral,[2,38] Peri and/or subungual inflammation may be seen in secondary or congenital syphilis.[19] Paronychia associated with tuberculosis (TB) [Figure 4] includes painless paronychia (PP) as a result of primary inoculation TB in medical personnel or among patients infected with mycobacterium TB.[39,40] CP associated with TB verrucosa cutis, infection of the distal phalanx leading to contiguous involvement of the PNF and onychodystrophy with tubercular PP have also been reported.[41,42,43] Paronychia is also considered to be a rare variant of cutaneous leishmaniasis.[44,45] Metastatic cancer, subungual melanoma, squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) [Figure 5] should always be excluded when CP is atypical in presentation, involves a single digit or does not respond to conventional treatment.[4,5] Metastatic lesions to the nail bed tend to lift up the nail and the most common source is primary bronchogenic carcinoma.[46] Peripheral vascular disease (PVD) [Figure 6] and Raynaud’s phenomenon may also uncommonly present as CP.[47] Several drugs [Table 4] have been known to cause CP or a delayed complication such as periungual pyogenic granuloma.[4,48,49,50,51] Mechanisms include an increase in the retinoic acid concentrations and inhibition of EGFR.[2,52] Pemphigus [Figure 7], psoriasis [Figure 8] and reactive arthritis may also present with CP, although presentation as AP is more common.[2,8,9]

Figure 4.

Chronic paronychia associated with tuberculosis

Figure 5.

Chronic paronychia associated with an underlying malignancy (squamous cell carcinoma)

Figure 6.

Chronic paronychia associated with underlying peripheral vascular disease

Table 4.

Drugs causing paronychia

| Drug class | Drug | Incidence |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Taxanes | Docetaxel, paclitaxel | Uncommon |

| 2. EGFR inhibitors | Cetuximab panitumumab | 10% of the patients on Cetuximab developed CP |

| 3. EGFR tyrosine Kinase inhibitors | Geftinib | Two-thirds of the cases treated developed CP |

| Erlotinib | 28%–40% of the patients with NSCLC developed CP | |

| Osimertinib | 30%–35% patients treated developed CP | |

| 4. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors | Imatinib | Periungual PG has been reported |

| 5. MEK and EKR inhibitors | Selumetinib | Delayed onset paronychia was reported in 9% of the treated patients |

| 6. B-RAF Inhibitors | Vemurafenib | Uncommon |

| 7. Anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody | Rituximab | Uncommon |

| 8. VEGF inhibitors | Bevacizumab | Uncommon |

| 9. Retinoids | Isotretinoin> etretinate> acitretin | CP and hypergranulation of the lateral nail folds has been described with Isotretinoin and is uncommon with etretinate and least common with acitretin. |

| 10. Anti-retroviral drugs | Lamivudine protease inhibitors- indinavir | CP and PPG Common |

EGFR = epidermal growth factor receptor, CP = chronic paronychia, PG = pyogenic granuloma, NSCLC = nonsquamous cell lung cancer, B-RAF = B-rapidly accelerated fibrosarcoma, VEGF = vascular endothelial growth factor

Figure 7.

Chronic paronychia with nail dystrophy in a patient with pemphigus vulgaris

Figure 8.

Chronic paronychia in a case of psoriasis vulgaris

Clinical features

CP presents with erythema, pain, and swelling involving the perionychium of >6 weeks duration and generally involves more than one fingernail.[2,4,23] [Figure 9] Pus discharge may be associated, but a frank abscess is not seen.[38] Associated nail matrix damage can lead to ridging, discoloration, Beau’s lines, and onychomadesis.[2,9,16,18] Green discoloration of the nail plate is a suggestive of Pseudomonas colonization.[7] Daniel et al.[53] proposed a severity scale for CP [Table 5]. Recently, a new severity index for the evaluation of CP has been proposed by Atiş et al.[54] [Table 6].

Figure 9.

Chronic paronychia showing erythema, pain and swelling involving the perionychium of multiple digits. Loss of cuticle is also visible

Table 5.

Severity scale for chronic paronychia proposed by Daniel et al.[53]

| Severity scale for chronic paronychia | |

|---|---|

| Stage I | Some redness and swelling of the proximal and/or lateral nail folds causing disruption of the cuticle. |

| Stage II | Pronounced redness and swelling of the proximal and/or lateral nail folds with disruption of the cuticle seal. |

| Stage III | Redness, swelling of the proximal nail fold, no cuticle, some discomfort, some nail plate changes. |

| Stage IV | Redness and swelling of the proximal nail fold, no cuticle, tender/painful, extensive nail plate changes. |

| Stage V | Same as stage IV plus acute exacerbation (acute paronychia) of chronic paronychia. |

Table 6.

Objective severity index proposed by Atis et al.[52]

| Objective severity index (Atis et al.)[35] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters (PNF and LNFs) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 1. Number of nail folds involved | – | 1 nail fold | 2 nail folds [proximal or/and lateral] | Bilateral lateral nail fold involvement and proximal nail fold involvement |

| 2. Edema | Absent | Mild | Moderate | Severe |

| 3. Erythema | Absent | Mild | Moderate | Severe |

| 4. Nail plate changes | Absent | Mild | Moderate | Severe |

| 5. Cuticle involvement | Normal | Damaged | Cuticle absent | – |

PNF = proximal nail fold, LNFs = lateral nail folds

Combined total score (between 0 [min.] and 14)

Diagnosis and differential diagnosis

A detailed history is essential including trauma, occupation, hobbies, drug intake, diabetes, HIV, or PVD. Examination findings include edema, erythema, tenderness, and retraction of the PNF along with absence of the adjacent cuticle, generally affecting multiple fingers. Associated nail changes may also be present. Recalcitrant or atypical case may require microscopy (gram staining, potassium hydroxide mount, tzanck smear) culture and/or biopsy, HIV testing, and blood sugar testing.

As compared to AP, CP has a gradual onset, is less painful, involves more than one digit, and can be associated with nail changes.[14] Cutaneous neoplasms as well as malignancies of the nail unit may present as paronychia and failure to respond to conventional therapy is an ominous sign.[2,55] In contrast, long-standing paronychia is considered to be a risk factor for the development of SCC.[56] Recurrent CP, involvement of single digit, and an absence of response to conventional therapy warrant a biopsy to rule out malignancy.

Treatment

The treatment of CP consists of ending the source of irritation, impeding inflammation, allowing the cuticle to regenerate through general measures [Table 7], medical management, and/or surgical management.

Table 7.

Recommended general measures for prevention of chronic paronychia

| Recommended general measures for prevention of chronic paronychia[2,4,19] |

|---|

| Avoid • Prolonged exposure to wet work, moist environments • Prolonged contact with contact irritants including detergent and soap • Trauma, manipulation of nail folds, manicuring, finger sucking, nail biting • Trimming of nail cuticles • Artificial nails |

| Minimize further injury and allow recovery • Keep nails short •Ensure proper footwear and gloves • Rubber gloves(preferably with inner cotton lining) to be used when expecting contact with irritants • Keep hands clean, dry, and moisturize regularly • Diabetic patients should ensure a strict diabetic control |

Medical management

At present, topical corticosteroids (CS) are considered the mainstay of therapy and are considered to be superior to topical antibiotics and systemic antifungals with the use of the latter only recommended in case of accompanying candida infection[2,4,28,36] [Table 8].

Table 8.

Medical management of chronic paronychia

| Medical management of chronic paronychia |

|---|

| A. Topical mid-potent corticosteroid ointment is applied for 2–4 weeks and repeated for flares.[2,4,28] |

| B. Topical broad-spectrum antifungals such as ciclopirox 0.77% topical suspension, which have a significant anti-inflammatory action have shown good results.[57] |

| C. Combined use of a topical anti-fungal(and topical corticosteroid has not shown to be more efficacious as compared to the use of a topical CS alone.[2,58] |

|

D. Tacrolimus ointment is a second-line option for cases not responding to routine management and has been found to be superior to betamethasone 17-valerate or placebo (unmedicated emollient)[59] •Ointment formulation helps to restore barrier function •Active component impedes the elicitation phase of allergic contact dermatitis and prevents an irritant response. |

| E. Intralesional steroid injection use is indicated for resistant cases.[14,58] |

| F. Short course of systemic corticosteroids is recommended in patients with severe involvement of multiple digits.[5,20,58] |

| G. Antiseptics or antifungal lotions or solutions may be used for several months.[2,4,57] |

| H. Oral antifungal agent in the usual doses (itraconazole or fluconazole) is indicated if C.albicans is confirmed or in refractory cases before proceeding with an invasive procedure[2,4,31] |

| I. Management of chemotherapy-induced paronychia and periungual pyogenic granuloma-like lesions: propranolol 1%[60] cream, timolol 0.5% gel,[61,62,63] betaxolol 0,25% eye drops,[64] and adapalene gel.[65] |

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT OF PARONYCHIA

Surgical management in AP is reserved for patients with well-formed abscess/fluctuance or a run-around abscess; failure to respond to medical management and/or extensive involvement or fulminant infection of the eponychium.[2,66] The principle behind surgical intervention in the case of AP is to allow drainage of the purulent material and/or decompress an abscess if present.[67]

The indications for surgical management in CP include more than 6 months duration and lack of response to/failure of medical treatment.[4,67] The surgical approaches aid in removal of the chronically inflamed surrounding tissue fibrosis, aiding drug penetration and cuticular regrowth of the cuticle.[67]

Preoperative evaluation is discussed in Table 9.

Table 9.

Preoperative checklist

| Preoperative checklist[20,53,54,67] | |

|---|---|

| History | Onset Risk factors Progression Comorbidities (diabetes, immunosuppression, peripheral vascular disease) Drugs (retinoids, chemotherapy, ART, anti-platelet,$ anti-coagulant drugsa) |

| Examination | Number of nails affected Severity/extent Status of nail folds, cuticle Associated nail plate changesb |

| Grading | Refer to Tables 5–7 |

| Digital pressure test/fluctuance | To rule out an abscess (blanching will be seen) |

| Investigations | Blood sugar HIV Coagulation profile 10% KOH mount––nail clipping/subungual debrisc Fungal culture |

| Consent | An informed consent for the surgery is taken. |

KOH = potassium hydroxide, HIV = human immunodeficiency virus

aThese drugs may cause increased bleeding during surgery

bIf nail plate changes/irregularities are present, decision may be taken to remove the nail plate during surgery

cIf onychomycosis or secondary fungal colonization is suspected

Intraoperative period

The digit to be operated upon is cleaned thoroughly with betadine and normal saline. A proximal digital block using 2 mL (1 mL on each side) of 2% lignocaine (without adrenaline) is preferred for anesthesia.[68]

The local infiltration of the anesthetic agent into the affected region is often ineffective and more painful than the administration of drugs of a digital block. The next step is application of a tourniquet to prevent excessive bleeding during the surgery. (If procedure lasts longer than 15 min, tourniquet should be released for a few minutes to allow reperfusion.)[69]

Surgical techniques for acute paronychia [Table 10]

Summary of Surgical techniques for acute paronychia

| Surgical technique | Method | Principle/advantage | Disadvantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| No-incision technique[70,71] | A no 11 or 15 scalpel blade (with cutting edge away from nail plate) is inserted at the junction of the lateral nail fold and proximal nail fold to allow spontaneous pus drainage. | No incision is produced in the LNF, and possibility of necrosis of the adjacent tissue is decreased No anesthesia is required | Can only be used when the abscess is small and laying close to the nail sulcus |

| DAREJD technique[72] | A 21- or 23-gauge needle, with its beveled edge up is used to lift the lateral nail fold, at the point where it meets the nail itself, enabling egress of the purulent material. Gentle pressure may be applied close to the nail bed to facilitate complete drainage. | No incision is required Eliminates the requirement for anesthesia or daily dressing | Can only be used for small abscesses laying close to the nail sulcus |

| Single-incision technique[2,14,19,71] | After a digital block, an incision is made using a no. 11 or 15 blade, in the paronychium directly over the abscess while placing the sharp edge of the blade from the nail, preventing matrixial loss. In a different approach, a longitudinal incision is made parallel to the nail fold, the entire nail fold is lifted to visualize the base of the nail and proximal one third of the nail plate is removed.[14,69] | Recommended for large abscesses and those present at a distance from the nail sulcus as well as when the no-incision techniques are not successful | Requires anesthesia and incision |

| Double-incision technique[2,19,71] | Longitudinal incisions are made on either side of the nailfold which is reflected proximally, wound is cavity irrigated, nail fold is returned to its original position and a gauze inserted beneath it. A subungual abscess may require the partial or total removal of the nail plate | For run-around abscess or extensive eponychial involvement Nail bed is exposed to allow adequate drainage of any infectious material. | Requires anesthesia and incision |

| Swiss-role technique[4,73] | Incision is made on either side of the nail fold using a no.15 scalpel blade. Nail fold is elevated and reflected proximally, rolled up like a Swiss-roll over a piece of gauze or nonadherent dressing and secured to the skin using two nonabsorbable stay sutures. | Described for a run-around abscess Nail bed is exposed to allow adequate drainage of any infectious material. | Requires anesthesia and incision |

LNF = lateral nail fold, PNF = proximal nail fold

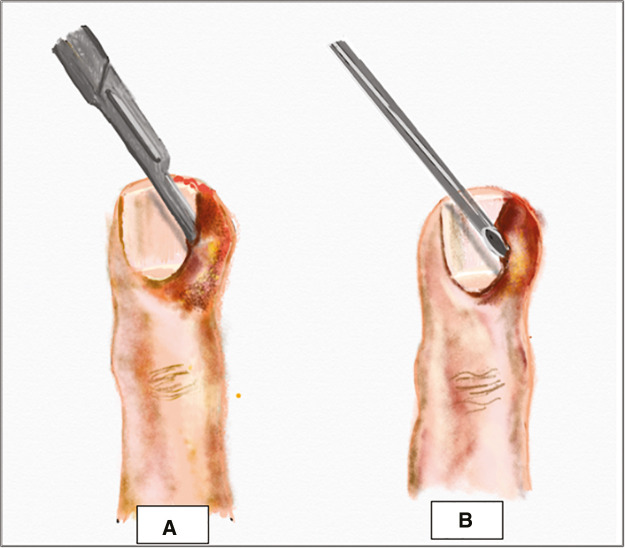

No-incision technique

A No. 11 or 15 scalpel blade (with cutting edge pointed away from nail plate); freer elevator, a hemostat or spatula is placed into the nail sulcus under the nail fold until the abscess is decompressed. The blade is inserted at the junction of the perionychium and the eponychium, extending proximally till the proximal nail edge is visualized. Next, the proximal one-third of the nail may be removed to ensure maximal pus drainage. The wound cavity is irrigated with isotonic sodium chloride. A small piece of mesh gauze may be placed beneath the nail fold allowing continued drainage and removed after 2 days[70,71] [Figure 10A].

The DAREJD technique uses a 21- or 23-gauge needle, to lift the lateral nail fold, at the point where it meets the nail itself, enabling egress of the purulent material. This is followed by wound dressing, and a 5-day course of antibiotics with no subsequent need for dressing[72] [Figure 10B].

Figure 10.

(A) No-incision technique: scalpel blade with cutting edge away from nail plate is inserted at the junction of the lateral nail fold and proximal nail fold to allow spontaneous pus drainage. (B) DAREJD technique: needle inserted into the lateral nail fold and lifted to allow pus drainage

Single-incision technique

This procedure is recommended for large abscesses and those present at a distance from the nail sulcus as well as when the no-incision techniques are not successful[2,19,71] [Figure 11]. The wound is then irrigated with saline, packed with gauze, and dressing is done.

Figure 11.

Single-incision technique: for larger abscesses, number 11 or 15 blade is used to make an incision over the abscess allowing its drainage

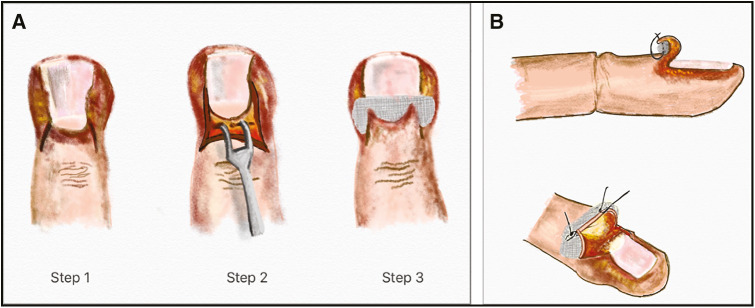

Double-incision technique and Swiss roll technique

If the entire eponychium is involved, or a run-around abscess is present, longitudinal incisions can be made on both sides of the nail. Complete nail plate removal is reserved for subungual extension of abscess, causing nail plate separation from the underlying matrix[2,19,69] [Figure 12A].

Pabari et al.[4] described another technique known as the Swiss Roll technique for a run-around abscess [Figure 12B]. After the double incision, the nail fold is reflected proximally. The dressing is removed after 2 days, wound examined, and if found to be clean, the anchoring sutures are removed. The nail fold is placed back in its original position.[73]

Figure 12.

(A) Double-incision technique: when the abscess is large or entire eponychium is involved, incisions are made on both sides of the nail fold, the nail fold is reflected, cavity is irrigated and a gauze is placed inside. (B) Swiss Roll technique for a run-around abscess. After the double incision, the nail fold is reflected proximally over piece of gauze or nonadherent dressing and secured to the skin using two nonabsorbable stay sutures

Surgical techniques for chronic paronychia [Table 11]

Table 11.

Summary of Surgical techniques for chronic paronychia

| Surgical technique | Method | Principle | Advantage | Disadvantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Eponychial marsupialization[37,74] | Removal of a crescent-shaped portion of the dorsal aspect of the PNF. Incision stretches from one LNF to the other and starts 1mm away from the distal margin of the eponychium extending around 6 mm proximally. | Exteriorizes the inflamed, obstructed nail matrix, allowing its drainage. Distal rim of eponychium is spared | Prevents subsequent roughness of the nail plate Easy to perform | Prolonged healing time Retraction of the PNF Postoperative increase of the nail plate’s length. |

| 2. En bloc excision of the proximal nail fold[75] | Removal of a wedge-shaped crescent formed of the entire depth of the PNF, with a width of 5-6mm, extending from one LNF to the other Distal rim of the eponychium is not spared | Exposes nail matrix, allowing drainage Preserving the fibrosed nail fold has no added advantage | More likely to be curative Cosmetically more acceptable Better functional outcome Easy to perform | Prolonged healing time Retraction of the PNF Postoperative increase of the nail plate’s length. |

| 3. Swiss roll technique[4,73] | Incision is made on either side of the nail fold using a no.15 scalpel blade. Nail fold is elevated and reflected proximally, rolled up like a Swiss-roll over a piece of gauze or nonadherent dressing and secured to the skin using two nonabsorbable stay sutures. | Nail bed is exposed to allow adequate drainage of any infectious material. | Preservation of the nail plate Absence of a skin defect which Quick healing Good cosmetic and functional outcome. | Although this technique improves the acute process, it does not solve the chronic fibrosis problem. |

| 4. Square-flap technique[68] | Oblique incisions (4–5 mm) are made on both sides of the proximal nail fold. Next an incision is made parallel to the epidermis and beneath the fibrosis. The fibrotic tissue lying underneath is removed while saving the epidermis of the PNF. The square flap is kept in place and surgical closure is done using simple interrupted sutures. | Aids in removal of the fibrotic tissue without complete excision of PNF and LNF | Healing in 2 weeks and cuticular regrowth in 6 weeks Good cosmetic and functional outcome. Quick recovery Lack of PNF retraction No increase in nail plate length | Nail fold skin quality is of vital importance for the success Technique is neither fast nor easy to perform, Requires a skilled nail surgeon. |

LNF = lateral nail fold, PNF = proximal nail fold

Eponychial marsupialization (with/without nail plate removal)

First introduced by Keyser and Eaton, this procedure involves the excision of a crescent-shaped portion of the PNF. The excision area includes all of the affected tissue, extends from one LNF to the other and starts 1 mm away from the distal margin of the eponychium stretching around 6 mm proximally [Figure 13]. The entire inflamed tissue within the margins of the crescent and going down to, but not including, the germinal matrix is excised and packed with gauze pieces. This helps to exteriorize the inflamed, obstructed nail matrix, enabling its drainage. Wound epithelization tends to occur in 2–3 weeks and conservation of the ventral aspect of the PNF, prevents the consequent roughness of the nail plate, thus, delivering a more cosmetically appealing result.[74] Concomitant nail removal in patients with nail plate irregularities was proposed by Bednar et al.[37] They suggested that nail removal more thoroughly debrides the entire nail fold by allowing drainage of both the volar portion of the dorsal roof as well as the ventral floor.

Figure 13.

Eponychial marsupialization: excision of a crescent-shaped portion of the dorsal aspect of the proximal nail fold. The excision area starts 1 mm away from the distal margin of the eponychium extending around 6 mm proximally

En bloc excision of the proximal nail fold

This technique, first described by Baran et al., involves the excision of a crescent-shaped segment, formed of the entire depth of the PNF, with a width of 5-6 mm, extending from one LNF to the other, without the concurrent removal of the nail plate [Figure 14A–C]. Complete regeneration of the PNF along with the cuticle is said to occur over a 12-week period. With a post-op normal attachment to the nail plate, minimal effect on the nail shininess the outcome is cosmetically and functionally acceptable. The distal most part of the eponychium is not conserved, as is done in the case of marsupialization, as the authors recommend that the inflamed, fibrosed nail fold with a reduced vascularity does not participate considerably in the nail and cuticular regrowth. It should be noted, however, that en bloc excision may lead to a postoperative lengthening of the nail plate.[75]A subsequent study, compared the results of en bloc excision of the PNF without nail plate removal to that with nail plate removal and concomitant nail avulsion was found to produce a better surgical outcome.[67]

Figure 14.

En bloc excision of the proximal nail fold: this technique involves the removal of a wedge-shaped crescent formed of the entire depth of the PNF, with a width of 5–6 mm, extending from one LNF to the other, without the removal of the nail plate

Swiss-roll technique

A modification of this technique may be used in CP, wherein the nail bed is kept exposed for 7 days to facilitate drainage of any purulent material. The advantages include preservation of the nail plate and lack of a skin defect which enables faster healing with good cosmetic and functional results.[4,73]

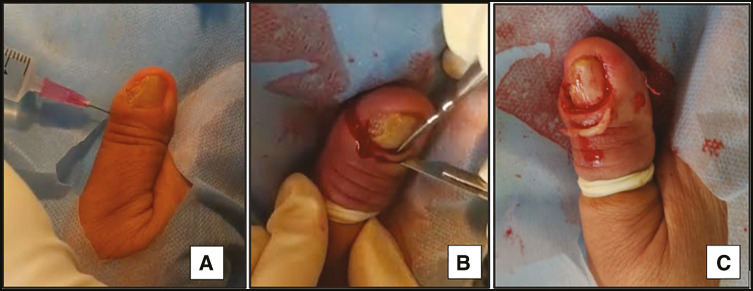

Square flap technique

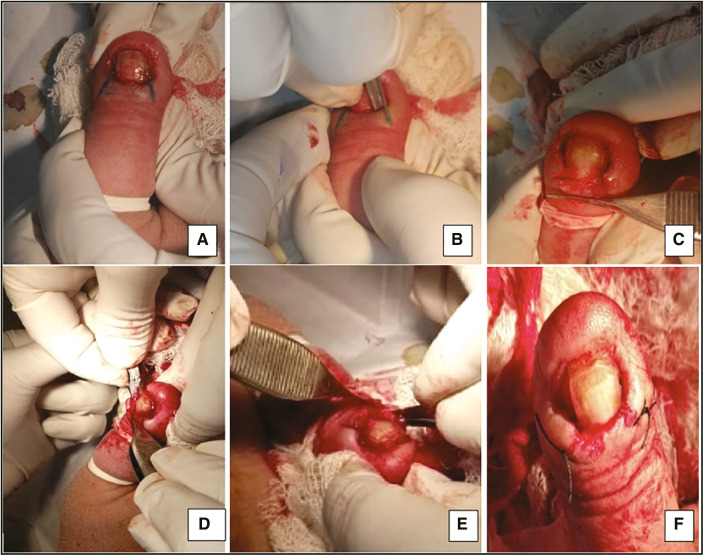

A recently introduced procedure involves the excision of the fibrotic tissue without complete removal of PNF and LNF. Oblique incisions of length (4-5 mm) are made on both sides of the PNF. Next, an incision is made parallel to the epidermis, beneath the fibrosis, taking precautions so as to avoid injury to the nail matrix. The square flap thus created is lifted using forceps. The fibrotic tissue lying underneath is removed while conserving the epidermis of the PNF. A similar incision on the LNF can be used to remove lateral fibrosis, tilting the blade at a 45° angle. The square flap is repositioned and surgical closure is done using simple interrupted sutures [Figure 15A–F]. The epidermis of the proximal and LNF can be conserved using this technique [Figure 16]. However, it must be emphasized that the nail fold skin quality is of utmost value in the success of this technique.[68]

Figure 15.

(A–F) Square flap technique. (A) Oblique marking guidelines are made on both sides of the proximal nail fold. (B) Followed by incision along these markings. Next an incision is made parallel to the epidermis and beneath the fibrosis. (C) The square flap is lifted using a forceps. (D) The fibrotic tissue lying underneath is removed while saving the epidermis of the PNF. (E) A similar incision on the LNF can be used to remove latera fibrosis. (F) The square flap is kept in place and surgical closure is done using simple interrupted sutures

Figure 16.

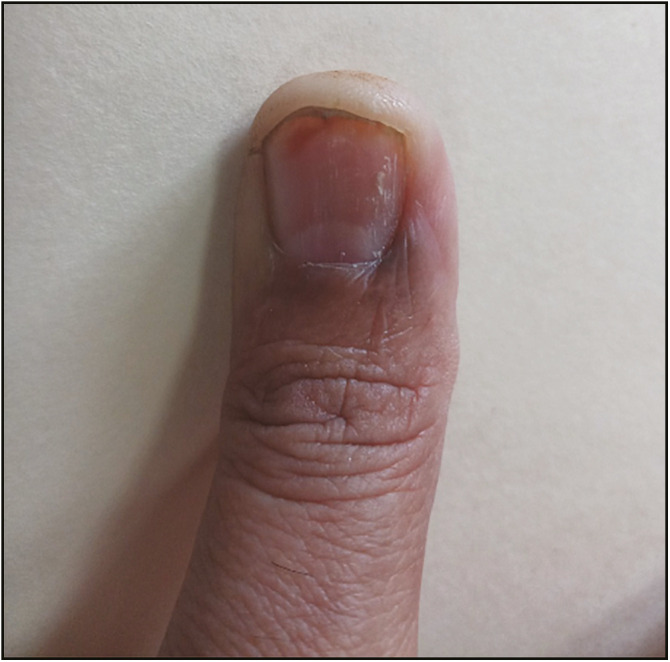

Postop (square flap technique) photograph at 2 months. Healing was observed in 2 weeks and cuticular regrowth in 6 weeks

Postoperative period

Cleaning with an antibiotic solution once a day, application of a topical antibiotic and daily dressing are recommended. Oral antibiotics are administered for a period of 5–7 days and dressing may be continued for 1–2 weeks until healthy granulation tissue is seen.[67] Topical corticosteroid and/or antifungals may also be prescribed.[14] Counseling regarding strict avoidance of contact with irritant/allergens as is essential.[67] Complete healing is expected to occur in 2 weeks, whereas the cuticle regrowth takes around 6 weeks post-surgery.[68]

Postoperative complications

Secondary infection, pain, wound dehiscence, suture margin necrosis, hemorrhage, scarring, nail dystrophy, and relapse have been reported.[37,67] Other complications include long recovery intervals and a postoperative increase in the nail plate length due to PNF retraction.[68,77] Avoidance of irritant contact, hygiene, daily dressing, prevention of secondary infection can help prevent these.

CONCLUSION

Paronychia refers to the inflammation of the tissue which immediately surrounds the nail and can be acute or chronic. AP is most commonly bacterial in origin and presents as sudden onset redness, edema and pain with/without the formation of a frank abscess, along the LNF and/or PNF, commonly involving a single digit. If diagnosed early, AP, with mild inflammation and no abscess can be treated nonsurgically with warm soaks 3–4 times daily, topical antibiotic with/without a topical CS or a combination of these. Significant erythema or an abscess, necessitates use of systemic antibiotics. Surgical management in AP is reserved for a well-formed abscess, failure to respond to medical management, and/or extensive involvement. No randomized controlled trials have compared the various methods of drainage in AP and treatment should therefore be tailored to the clinical situation and skill of the physician.

CP presents with erythema, pain, and swelling involving the perionychium of >6 weeks duration, and generally involves multiple digits. Topical CS are considered the first-line treatment, whereas tacrolimus and topical antifungals are second line options. Surgical intervention is reserved for cases persisting for greater than 6 months, not responding to conservative measure. Various surgical approaches for CP such as marsupialization, en bloc excision of PNF, Swiss-roll technique and square flap technique aim at the removal of the fibrosed tissue facilitating drainage.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Acknowledgement

Nil.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rockwell PG. Acute and chronic paronychia. Am Fam Physician. 2001;63:1113–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shafritz AB, Coppage JM. Acute and chronic paronychia of the hand. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2014;22:165–74. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-22-03-165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fleckman P. Structure and function of the nail unit. In: Scher RK, Daniel CR III, editors. Nails: diagnosis, therapy, surgery. Oxford: Elsevier Saunders; 2005. p. 14. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Relhan V, Goel K, Bansal S, Garg VK. Management of chronic paronychia. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:15–20. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.123482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rigopoulos D, Larios G, Gregoriou S, Alevizos A. Acute and chronic paronychia. Am Fam Physician. 2008;77:339–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brook I. Paronychia: a mixed infection. Microbiology and management. J Hand Surg Br. 1993;18:358–9. doi: 10.1016/0266-7681(93)90063-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Biesbroeck LK, Fleckman P. Nail disease for the primary care provider. Med Clin North Am. 2015;99:1213–26. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2015.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee HE, Wong WR, Lee MC, Hong HS. Acute paronychia heralding the exacerbation of pemphigus vulgaris. Int J Clin Pract. 2004;58:1174–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2004.00111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baran R, Barth J, Dawber RP. Nail disorders: common presenting signs, differential diagnosis, and treatment. New York, NY: Churchill Livingstone; 1991. pp. 93–100. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Robert C, Sibaud V, Mateus C, Verschoore M, Charles C, Lanoy E, et al. Nail toxicities induced by systemic anticancer treatments. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:e181–9. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)71133-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garden BC, Wu S, Lacouture ME. The risk of nail changes with epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors: a systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:400–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2011.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Figueiras Dde A, Ramos TB, Marinho AK, Bezerra MS, Cauas RC. Paronychia and granulation tissue formation during treatment with isotretinoin. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91:223–5. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20163817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sibel S, Macher A, Goosby E. Paronychia in patients receiving antiretroviral therapy for human immunodeficiency virus infection. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2000;90:98–100. doi: 10.7547/87507315-90-2-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jebson PJ. Infections of the fingertip: paronychias and felons. Hand Clin. 1998;14:547–55, viii. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Habif TP. Nail diseases. In: Habif TP, editor. Clinical dermatology: a color guide to diagnosis and therapy. 4th ed. Edinburgh: Mosby; 2008. pp. 71–2. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tosti A, Piraccini BM. Nail disorders. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, editors. Dermatology. 1st ed. London: Mosby; 2003. pp. 1072–3. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baran R. Periungual nail disorders. In: Tosti A, Bristow I, Haneke E, Dawber RPR, Baran R, editors. A text atlas of nail disorders: techniques in investigation and diagnosis. 3rd ed. UK: CRC Press; 2003. p. 82. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Noriega L, Gioia Di Chiacchio N, Cury Rezende F, Di Chiacchio N. Periungual lesion due to secondary syphilis. Skin Appendage Disord. 2017;2:116–9. doi: 10.1159/000449418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Company-Quiroga J, Alique-García S, Martínez-Sánchez D. Atypical acute paronychia. Eur J Dermatol. 2019;29:246–7. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2019.3568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Berker D, Baran R, Dawber RP. Disorders of the nails. In: Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, Griffiths S, editors. Rook’s textbook of dermatology. 7th ed. Oxford: Blackwell Science; 2005. p. 62.1. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Raff AB, Kroshinsky D. Cellulitis: a review. JAMA. 2016;316:325–37. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.8825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Choosing Wisely Campaign. [Last accessed on 2016 Aug 11]. Available from: http://www.choosingwisely.org/clinician-lists/american-college-emergency-physicians-antibiotics-wound-cultures-in-emergency-department-patients/

- 23.Leggit JC. Acute and chronic paronychia. Am Fam Physician. 2017;96:44–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aluja Jaramillo F, Quiasúa Mejía DC, Martínez Ordúz HM, González Ardila C. Nail unit ultrasound: a complete guide of the nail diseases. J Ultrasound. 2017;20:181–92. doi: 10.1007/s40477-017-0253-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Turkmen A, Warner RM, Page RE. Digital pressure test for paronychia. Br J Plast Surg. 2004;57:93–4. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2003.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marx J, Hockberger R, Walls R, editors. Handbook of Rosen’s emergency medicine: concepts and clinical practice. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2013. pp. 534–70. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roberts JR, Hedges JR, editors. Incision and drainage: clinical procedures in emergency medicine. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2013. pp. 719–58. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wollina U. Acute paronychia: comparative treatment with topical antibiotic alone or in combination with corticosteroid. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15:82–4. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-3083.2001.00177-6.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chang P. Diagnosis using the proximal and lateral nail folds. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:207–41. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2014.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fowler JR, Ilyas AM. Epidemiology of adult acute hand infections at an urban medical center. J Hand Surg Am. 2013;38:1189–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2013.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Daum RS. Clinical practice. Skin and soft-tissue infections caused by methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:380–90. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp070747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rerucha CM, Ewing JT, Oppenlander KE, Cowan WC. Acute hand infections. Am Fam Phys. 2019;99:228–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chiriac A, Brzezinski P, Foia L, Marincu I. Chloronychia: green nail syndrome caused by pseudomonas aeruginosa in elderly persons. Clin Interv Aging. 2015;10:265–7. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S75525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sezer E, Bridges AG, Koseoglu D, Yuksek J. Acquired periungual fibrokeratoma developing after acute staphylococcal paronychia. Eur J Dermatol. 2009;19:636–7. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2009.0771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hay RJ, Baran R, Moore MK, Wilkinson JD. Candida onychomycosis–an evaluation of the role of candida species in nail disease. Br J Dermatol. 1988;118:47–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1988.tb01749.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tosti A, Piraccini BM, Ghetti E, Colombo MD. Topical steroids versus systemic antifungals in the treatment of chronic paronychia: an open, randomized double-blind and double dummy study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:73–6. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2002.122191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bednar MS, Lane LB. Eponychial marsupialization and nail removal for surgical treatment of chronic paronychia. J Hand Surg Am. 1991;16:314–7. doi: 10.1016/s0363-5023(10)80118-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dulski A, Edwards CW. StatPearls [Internet] Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2020. Paronychia. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK544307/ . [Last accessed on 2020 May 14] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Goette DK, Jacobson KW, Doty RD. Primary inoculation tuberculosis of the skin: Prosector’s paronychia. Arch Dermatol. 1978;114:567–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.O’Donnell TF, Jr, Jurgenson PF, Weyerich NF. An occupational hazard–tuberculous paronychia. Report of a case. Arch Surg. 1971;103:757–8. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1971.01350120121023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Goh SH, Ravintharan T, Sim CS, Chng HC. Nodular skin tuberculosis with lymphatic spread: a case report. Singapore Med J. 1995;36:99–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Khanna D, Chakravarty P, Agarwal A, Gupta R. Tuberculous dactylitis presenting as paronychia with pseudopterygium and nail dystrophy. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:e172–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2012.01843.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.da Silva Sousa AC, Sousa M, Tente D, Menezes N, Baptista A, Guedes R. Ungual tuberculosis: a unique clinical case. Skin Appendage Disord. 2019;5:386–9. doi: 10.1159/000501698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Raja KM, Khan AA, Hameed A, Rahman SB. Unusual clinical variants of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Pakistan. Br J Dermatol. 1998;139:111–3. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1998.02325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Iftikhar N, Bari I, Ejaz A. Rare variants of cutaneous leishmaniasis: whitlow, paronychia, and sporotrichoid. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:807–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2003.02015.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Paringao AJ. A swollen draining thumb. Am Fam Physician. 2002;65:105–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Viswanath O, Peck J, Gill JS. An atypical presentation of Raynaud’s disease. Med Princ Pract. 2019;28:394–6. doi: 10.1159/000499495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wollina U. Systemic drug-induced chronic paronychia and periungual pyogenic granuloma. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2018;9:293–8. doi: 10.4103/idoj.IDOJ_133_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Habif TP. Clinical dermatology: a color guide to diagnosis and therapy. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2016. Nail disorders; pp. 960–85. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lacouture ME, Anadkat MJ, Bensadoun RJ, Bryce J, Chan A, Epstein JB, et al. MASCC Skin Toxicity Study Group. Clinical practice guidelines for the prevention and treatment of EGFR inhibitor-associated dermatologic toxicities. Support Care Cancer. 2011;19:1079–95. doi: 10.1007/s00520-011-1197-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Capriotti K, Capriotti JA, Lessin S, Wu S, Goldfarb S, Belum VR, et al. The risk of nail changes with taxane chemotherapy: a systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173:842–5. doi: 10.1111/bjd.13743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rigopoulos D, Gregoriou S, Belyayeva Y, Larios G, Gkouvi A, Katsambas A. Acute paronychia caused by lapatinib therapy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:94–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2008.02928.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Daniel CR, 3rd, Iorizzo M, Piraccini BM, Tosti A. Grading simple chronic paronychia and onycholysis. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1447–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2006.03128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Atış G, Göktay F, Altan Ferhatoğlu Z, Kaynak E, Sevim Keçici A, Yaşar ş, et al. A proposal for a new severity index for the evaluation of chronic paronychia. Skin Appendage Disord. 2018;5:32–7. doi: 10.1159/000489024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kuschner SH, Lane CS. Squamous cell carcinoma of the perionychium. Bull Hosp Jt Dis. 1997;56:111–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tambe SA, Patil PD, Saple DG, Kulkarni UY. Squamous cell carcinoma of the nail bed: the great mimicker. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2017;10:59–60. doi: 10.4103/JCAS.JCAS_35_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Daniel CR, 3rd, Daniel MP, Daniel J, Sullivan S, Bell FE. Managing simple chronic paronychia and onycholysis with ciclopirox 0.77% and an irritant-avoidance regimen. Cutis. 2004;73:81–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Baran R. Common-sense advice for the treatment of selected nail disorders. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15:97–102. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-3083.2001.00179.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rigopoulos D, Gregoriou S, Belyayeva E, Larios G, Kontochristopoulos G, Katsambas A. Efficacy and safety of tacrolimus ointment 0.1% vs. Betamethasone 17-valerate 0.1% in the treatment of chronic paronychia: an unblinded randomized study. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160:858–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08988.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Piraccini BM, Alessandrini A, Dika E, Starace M, Patrizi A, Neri I. Topical propranolol 1% cream for pyogenic granulomas of the nail: open-label study in 10 patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:901–2. doi: 10.1111/jdv.13071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cubiró X, Planas-Ciudad S, Garcia-Muret MP, Puig L. Topical timolol for paronychia and pseudopyogenic granuloma in patients treated with epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors and capecitabine. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:99–100. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.4120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sibaud V, Casassa E, D’Andrea M. Are topical beta-blockers really effective “in real life” for targeted therapy-induced paronychia. Support Care Cancer. 2019;27:2341–3. doi: 10.1007/s00520-019-04690-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sollena P, Mannino M, Tassone F, Calegari MA, D’Argento E, Peris K. Efficacy of topical beta-blockers in the management of EGFR-inhibitor induced paronychia and pyogenic granuloma-like lesions: case series and review of the literature. Drugs Context. 2019;8:212613. doi: 10.7573/dic.212613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yen CF, Hsu CK, Lu CW. Topical betaxolol for treating relapsing paronychia with pyogenic granuloma-like lesions induced by epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:e143–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hachisuka J, Doi K, Moroi Y, Furue M. Successful treatment of epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor-induced periungual inflammation with adapalene. Case Rep Dermatol. 2011;3:130–6. doi: 10.1159/000329914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Shaw J, Body R. Best evidence topic report. Incision and drainage preferable to oral antibiotics in acute paronychial nail infection? Emerg Med J. 2005;22:813–4. doi: 10.1136/emj.2005.030163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Grover C, Bansal S, Nanda S, Reddy BS, Kumar V. En bloc excision of proximal nail fold for treatment of chronic paronychia. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:393–8; discussion 398-9. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2006.32079.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ferreira Vieira d’Almeida L, Papaiordanou F, Araújo Machado E, Loda G, Baran R, Nakamura R. Chronic paronychia treatment: square flap technique. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:398–403. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.02.1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Krunic AL, Wang LC, Soltani K, Weitzul S, Taylor RS. Digital anesthesia with epinephrine: an old myth revisited. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:755–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2004.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Canales FL, Newmeyer WL, 3rd, Kilgore ES., Jr The treatment of felons and paronychias. Hand Clin. 1989;5:515–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Paronychia Treatment & Management: Approach Considerations, Pharmacologic and Other Non-invasive Treatment, Drainage. 2019. [Last accessed on 2020 May 31]. Available from: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1106062-treatment#d11 .

- 72.Ogunlusi JD, Oginni LM, Ogunlusi OO. DAREJD simple technique of draining acute paronychia. Tech Hand Up Extrem Surg. 2005;9:120–1. doi: 10.1097/01.bth.0000163575.00615.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pabari A, Iyer S, Khoo CT. Swiss roll technique for treatment of paronychia. Tech Hand Up Extrem Surg. 2011;15:75–7. doi: 10.1097/BTH.0b013e3181ec089e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Keyser JJ, Eaton RG. Surgical cure of chronic paronychia by eponychial marsupialization. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1976;58:66–70. doi: 10.1097/00006534-197607000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Baran R, Bureau H. Surgical treatment of recalcitrant chronic paronychias of the fingers. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1981;7:106–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.1981.tb00609.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]