Abstract

Background

Atopic eczema (AE) is known to be associated with depression and anxiety. We aimed at investigating the occurrence of selected psychological comorbidities in patients with AE under treatment in our university dermatological department.

Methods

Monocentric prospective examination of adult AE patients using PO-SCORAD (Patient-Oriented Severity Scoring of AD), EASI (Eczema Area and Severity Index), POEM (Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure), DLQI (Dermatologic Life Quality Index), LSNS-6 (Lubben Social Network Scale 6), CES-D (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale), HADS-D and -A (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale), and GAD-7 (Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale-7) was carried out. We looked for correlations between AE severity and psychosocial comorbidities. Data were compared with age- and sex-matched controls from nonatopic subjects. Statistics: Mann-Whitney U test and Spearman's rank correlation were used.

Results

Eighty-four patients (44 women, median age 35.0 years, range: 19.4–92.8 years) were included. PO-SCORAD was 40.4 [23.4–55.4] (median [interquartile range]), EASI 9.3 [3.4–18.9], POEM 16 [8–24], and DLQI 10 [4–18]. Compared with 161 from the healthy LIFE-Adult cohort controls, our patients with AE had significantly higher scores for HADS, GAD-7, and CES-D (p < 0.001, respectively), but there was no increase in the LSNS score (18 vs. 19; p = 0.067). Within the group of AE patients, there was a significant correlation of the subjective skin severity and the depression and anxiety values: POEM significantly correlated with GAD-7, CES-D, and HADS-A and -D (p < 0.001). PO-SCORAD significantly correlated with GAD-7 and CES-D (p < 0.05). EASI correlated neither with HADS-A or -D nor with CES-D. Patients with suicidal thoughts, plans, or attempts in the last 12 months had significantly more severe AE than those without (POEM 25 [15.3–26] vs. 15 [7–23]; p = 0.013, and PO-SCORAD 51.6 [40.2–63] vs. 20.5 [20.7–52]; p = 0.014).

Conclusion

Patients with AE being currently under treatment in our department had significantly increased scores indicating depression and anxiety. Suicidal tendency was increased in patients with severe AE.

Key Message

AE patients may develop depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation. Patient-oriented scores may help identifying high-risk patients.

Keywords: Atopic dermatitis, Atopic eczema, Anxiety, Depression, Suicidal ideation

Introduction

Atopic eczema (AE) is a chronic inflammatory disease which may be associated with several atopic and nonatopic comorbidities [1, 2, 3]. Increased numbers of patients with AE were reported to suffer from depression (9.3–44.3%) and/or anxiety (3.31–26.2%) [2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14].

In a recently published cross-sectional population-based investigation in Leipzig (Leipzig Research Centre for Civilization Diseases/LIFE), subjects with self-reported physician-diagnosed AE had increased scores for depression and anxiety as well as reduced quality of life (QoL) [2]. We aimed at validating these findings in a group of patients being under treatment with their AE in our university dermatology department.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

Main Group (Patients)

This was a prospective monocentric noninterventional study conducted at our GA2LEN certified Atopic Dermatitis Centre of Reference and Excellence at the University Dermatology Department in Leipzig, Germany. Diagnosis of AE was based on the criteria of Hanifin and Rajka [15]. The study was conducted conforming to the principles embodied in the Declaration of Helsinki, was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Medical Faculty of the University of Leipzig (079/19-ek), and was registered in the German Clinical Trail Register (Registration No. DRKS00016946). All participants signed written consent prior to participation. The assessments took place between April 2019 and May 2020. Every participant followed a standardized study protocol that was administered and monitored by experienced dermatologists.

Control Group (Healthy)

As the control group, we included 161 age- and sex-matched subjects (2:1) from the LIFE-Adult cohort who had no self-reported history of AE. The details of the study are described elsewhere [16]. All analyzed subjects answered standardized questionnaires (CES-D, GAD-7, LSNS, and SF-8).

Scoring Atopic Eczema

Severity of AE was assessed by a trained dermatologist using objective SCORAD (Severity Scoring of Atopic Dermatitis) and EASI (Eczema Area and Severity Index). Patient's symptoms were assessed by using POEM (Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure), Numerous Rating Scale (NRS) for pruritus, and NRS for sleeping problems.

Questionnaires

Patients were asked to fill in the following 5 standardized questionnaires:

The German version of the Centre for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) is used to assess depression. The CES-D scale is a 20-item self-report scale designed to measure depressive symptomatology in the general population [17]. Patients reported on depressive symptoms during the last week by using a 4-grade scale ranging from 0 (rarely/none) to 3 (frequently). The maximum score is 60. A sum score of ≥23 was regarded as the cutoff value for the presence of depression [18, 19].

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) is a self-report questionnaire consisting of 2 subscales designed to identify and quantify depression (HADS-D) and anxiety (HADS-A). Each subscale includes 7 items. Each item is scored on a response scale with 4 alternatives ranging between 0 and 3. After adjusting for 6 items that are reversed scored, all responses are summed to obtain the 2 subscales. An optimal balance between sensitivity and specificity was found using a cutoff score of 8 or above for both HADS Anxiety and HADS Depression [20].

GAD-7 (Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7) is a 7-item anxiety scale and a brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder. The answer options range from 0 points (not at all) to 3 points (nearly every day). The recall period is 4 weeks; the maximum sum score is 21. A total score of ≥10 indicates the presence of an anxiety symptomatology [21].

In the short-form of the Lubben Social Network Scale (LSNS-6), each of 6 items scores from 0 to 5. The maximum score is 30. Higher scores indicate larger social networks, and lower scores indicate social isolation. A score below 12 is considered an indicator of social isolation [22].

The Dermatological Quality of Life (DLQI) assesses the QoL by asking for concern itch, embarrassment, clothing, social or leisure activities, sports, and problems caused by treatment. The questionnaire is structured with each question having 4 alternative responses: “not at all,” “a little,” “a lot,” or “very much” with corresponding scores of 0, 1, 2, and 3, respectively. The DLQI is calculated by summing the score of each question, resulting in a maximum of 30 and a minimum of 0. The higher the score, the greater the impairment of QoL [23].

In our self-constructed questionnaire, we asked, “Have you thought of suicide, had suicide plans, or attempted suicide, during the last 12 months/ever”? In a multiple-choice manner, the patients could select “no,” “thought of suicide,” “suicide plans,” and “attempted suicide.”

Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed with IBM SPSS Statistics, Version 24.0. Comparisons of continuous and discrete variables were made using nonparametric tests (Mann-Whitney U tests). The categorical variables were compared using the Pearson χ2 test. A p value of <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. Spearman's rank correlation coefficient (r) was used to measure the strength of associations between severity of AE and different psychosocial parameters. The correlation coefficient (r) was interpreted with the effect size scale of Brosius: 0–0.2 very weak, 0.2–0.4 weak, 0.4–0.6 medium, and >0.6 strong. The percentages were reported with 95% confidence interval. To minimize variability and balance, the groups matching (ratio 1:2) on factors age and sex were used.

Results

Comparison between Main and Control Groups

Study Population, Atopic Eczema Severity, and Quality of Life

We included 84 subsequent patients with AE and 161 controls (shown in Table 1). In AE patients, PO-SCORAD was 40.4 (823.4–55.4) (median [interquartile range]), EASI 9.3 (3.4–18.9), POEM 16 (8–24), and DLQI 10 [4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18].

Table 1.

Baseline data of subjects with AE and controls

| Physician-diagnosed AE | Matched control group from LIFE | p value (Mann-Whitney U) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 84 | 161 | |

| Sex female, n (%) | 44 (52.4) | 83 (51.6) | 0.902 |

| Age, years | 35 (29.5–51.6) | 34.5 (29.4–51.3) | 0.760 |

| GAD-7 | 6 (3–12.75) | 2 (1–5) | <0.001 |

| HADS-A | 6 (3–11) | No data | – |

| HADS-D | 4 (2–9) | No data | – |

| CES-D | 18 (10–27.8) | 9 (5–8) | <0.001 |

| LSNS | 18 (12–21) | 19 (14.3–22) | 0.067 |

Median and interquartile ranges are shown. Statistics: Mann-Whitney U test. In bold: p < 0.05. AE, atopic eczema; GAD-7, Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7; HADS-D and -A, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; LSNS-6, Lubben Social Network Scale.

Anxiety, Depression, and Social Network

Values for CES-D, HADS, and GAD-7 (shown in Table 1) indicated significantly increased scores for depression and anxiety in patients with AE (p < 0.001, respectively), but there were no significant differences between patients with AE and controls with regard to LSNS (shown in Table 1).

Analysis within the Group of AE Patients

Correlation between Anxiety and Depression with Severity of AE

Within the group of AE patients, there was a significant correlation of the subjective skin severity and the depression and anxiety values: POEM significantly correlated with GAD-7 and CES-D with medium effect size r = 0.468 and r = 0.460, respectively, p < 0.001. PO-SCORAD significantly correlated with GAD-7 and CES-D with weak effect size: r = 0.325 and r = 0.297, respectively, p < 0.05. The EASI correlated neither with HADS-A or -D nor with CES-D.

The symptoms pruritus and sleep disturbance were assessed with the PO-SCORAD. Sleep disturbance significantly correlated and with medium effect size with GAD-7 (r = 0.460) and CES-D (r = 0.447), p < 0.05. Pruritus showed a significant correlation with GAD-7 and CES-D, but with weak effect size r = 0.306 and r = 0.263, respectively, p < 0.05.

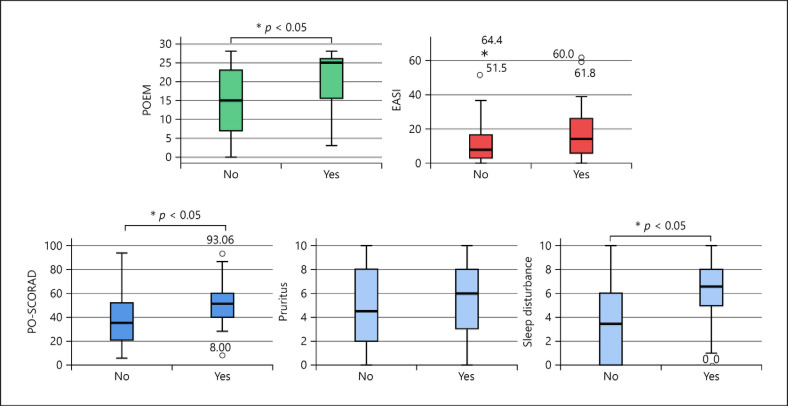

Suicidal Ideation and Suicide

Within the last 12 months, 18 (21.4% 95% CI [12.6; 30.2]) AE patients had thoughts and 2 (2.4% [0; 5.7]) had plans of suicide, but no one had attempted suicide. Subjects of this group had significantly more severe signs and symptoms of AE (as measured by POEM and PO-SCORAD, p < 0.05, respectively, but not with EASI) than those without suicidal thoughts; they suffered significantly (p < 0.05) more often from depression, anxiety, and sleep disturbance (as measured by CES-D, HADS, GAD-7, and PO-SCORAD); and their QoL (DLQI) was significantly decreased (p = 0.004) (shown in Table 2; Fig. 1).

Table 2.

Comparison of AE patients with and without suicidal thoughts, plans, or suicide during the last 12 months

| AE patients with suicidal thoughts, plans, or suicide during the last 12 months | AE patients without suicidal thoughts, plans, or suicide during the last 12 months | p value (Mann-Whitney U) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 18 | 65 | |

| Sex female, n (%) | 9 (50) | 34 (52.3) | 0.863 |

| Age, years | 33.1 (31.2–40.3) | 35.6 (26.7–52.3) | 0.573 |

| DLQI | 17 (9.5–22.5) | 8.0 (3–14) | 0.004 |

| POEM | 25 (15.3–26) | 15 (7–23) | 0.013 |

| PO-SCORAD | 51.6 (40.2–63) | 20.5 (20.7–52) | 0.014 |

| Pruritus (PO-SCORAD) | 6 (2.8–8.3) | 4.5 (2–8) | 0.327 |

| Sleep disturbance (PO-SCORAD) | 6.5 (4.2–8) | 3.5 (0–6) | 0.011 |

| EASI | 14.3 (6.3–26.7) | 8 (2.4–16.8) | 0.073 |

One patient did not answer the questions for suicide or suicidal ideation during the last 12 months. Median and interquartile ranges are shown. Statistics: Mann-Whitney U test. In bold: p < 0.05. Severity of the skin measured with DLQI, POEM, PO-SCORAD, and EASI. AE, atopic eczema; IQR, interquartile ratio; DLQI, Dermatologic Life Quality Index; POEM, Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure; PO-SCORAD, Patient-Oriented Severity Scoring of Atopic Dermatitis; EASI, Eczema Area and Severity Index.

Fig. 1.

Severity scores in patients with atopic eczema with and without suicidal thoughts, plans, or suicide attempt during the last 12 months. DLQI, Dermatologic Life Quality Index; POEM, Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure; PO-SCORAD, Patient-Oriented Severity Scoring of Atopic Dermatitis; EASI, Eczema Area and Severity Index.

Within their life span, 29 patients with AD (34.5% [24.3; 44.7]) had thoughts and 3 (3.6%) had plans of suicide, while 3 (3.6% [0; 7.6]) patients reported having had attempted suicide. Compared with the rest of the group, these subjects also had significantly more severe AE as measured with POEM (19.5 [14.0–26] vs. 15 [6.5–23]; p = 0.033) but not measured with DLQI, PO-SCORAD, or EASI.

Discussion

During the last years, research has acknowledged more and more the association of psychosocial comorbidities and AE. However, most studies performed are cross-sectional studies, which rely on health insurance data or patient-reported diagnosis. The strength of our study is that experienced dermatologists diagnosed the AE. Furthermore, the severity of the skin was assessed with multiple valid instruments (SCORAD, EASI, POEM, and DLQI).

With our analysis, we validated the results of our cross-sectional study which used the patient-reported diagnosis of AE [2]. Patients with AE show more signs of anxiety and depression compared to controls. However, they are not at a higher risk for social isolation. Furthermore, we showed that the severity of the skin especially the subjective severity significantly correlates with scores for anxiety and depression measured with GAD-7, HADS, and CES-D. Our data also show that the risk of suicidal ideation and attempt is significantly associated with the subjective severity of the skin. Especially, the symptom sleep disturbance is linked to increased risk of suicidal ideation. Therefore, we recommend not only the use of purely objective scores such as EASI for dermatological evaluation but also to further include subjective scores such as DLQI and POEM. These subjective severity scores are more helpful in identifying risk patients for anxiety, depression, and suicidal ideation.

A limitation of our study is the small sample size. Multicentric studies with a larger sample size should be conducted to validate our findings.

Statement of Ethics

The study was conducted conforming to the principles embodied in the Declaration of Helsinki, was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Medical Faculty of the University of Leipzig (079/19-ek), and was registered in the German Clinical Trail Register (Registration No. DRKS00016946). Written informed consent was obtained from participants to participate in the study.

Conflict of Interest Statement

Kage P. has received lecture fees as well as travel grants from Sanofi Genzyme, Berlin, Germany, travel grants from ALK-Abello, Berlin, Germany, Hamburg, Germany, and congress support from Novartis, Erlangen, Germany. Poblotzki L. has no conflicts of interest to declare. Zeynalova S. has no conflicts of interest to declare. Zarnowski J. received travel grants from ALK-Abello, Berlin, Germany, Hamburg, Germany, TAKEDA, Berlin, Germany, and CSL Behring. Simon J.C. has received lecture fees and honoraria for advisory boards as well as a nonrestricted scientific grant from Sanofi Genzyme, Berlin, Germany, lecture fees and honoraria for advisory boards from Novartis, Erlangen, Germany, and congress support from ALK-Abello, Hamburg, Germany. Treudler R. has received lecture fees and honoraria for advisory boards as well as a nonrestricted scientific grant from Sanofi Genzyme, Berlin, Germany, lecture fees and honoraria for advisory boards from AbbVie, Wiesbaden, Germany, Novartis, Erlangen, Germany, Takeda, Berlin, Germany, and ALK-Abello, Hamburg, Germany, lecture fees from Pfizer, Berlin, Germany, and congress support from Takeda, Berlin, Germany.

Funding Sources

Grant from Hautnetz Leipzig/Westsachsen e.V. for research on atopic dermatitis and comorbidities was received.

Author Contributions

Treudler R., Kage P., Zeynalova S., and Simon J.C. generated the concept of the present investigation. Treudler R., Kage P., Poblotzki L., and Zarnowski J. contributed to acquisition. All authors contributed to analysis, interpretation of data, and manuscript writing. All authors gave their final, pre-published approval of the version and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article. Further enquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

References

- 1.Kage P, Simon JC, Treudler R. Atopic dermatitis and psychosocial comorbidities. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2020 Feb;18((2)):93–102. doi: 10.1111/ddg.14029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Treudler R, Zeynalova S, Walther F, Engel C, Simon JC. Atopic dermatitis is associated with autoimmune but not with cardiovascular comorbidities in a random sample of the general population in Leipzig, Germany. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:e44–6. doi: 10.1111/jdv.14495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kage P, Zarnowski J, Simon JC, Treudler R. Atopic dermatitis and psychosocial comorbidities − what's new? Allergol Select. 2020;4:86–96. doi: 10.5414/ALX02174E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arima K, Gupta S, Gadkari A, Hiragun T, Kono T, Katayama I, et al. Burden of atopic dermatitis in Japanese adults analysis of data from the 2013 National Health and Wellness Survey. J Dermatol. 2018;45:390–6. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.14218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheng BT, Silverberg JI. Depression and psychological distress in US adults with atopic dermatitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2019;123:179–85. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2019.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chiesa Fuxench ZC, Block JK, Boguniewicz M, Boyle J, Fonacier L, Gelfand JM, et al. Atopic Dermatitis in America Study a Cross-Sectional Study examining the prevalence and disease burden of atopic dermatitis in the US adult population. J Invest Dermatol. 2019;139:583–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2018.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Falissard B, Simpson EL, Guttman-Yassky E, Papp KA, Barbarot S, Gadkari A, et al. Qualitative assessment of adult patients' perception of atopic dermatitis using natural language processing analysis in a Cross-Sectional Study. Dermatol Ther. 2020;10((2)):297–305. doi: 10.1007/s13555-020-00356-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eckert L, Amand C, Gadkari A, Rout R, Hudson R, Ardern-Jones M. Treatment patterns in UK adult patients with atopic dermatitis treated with systemic immunosuppressants data from The Health Improvement Network (THIN) J Dermatolog Treat. 2020 Dec;31((8)):815–20. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2019.1639604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eckert L, Gupta S, Gadkari A, Mahajan P, Gelfand JM. Burden of illness in adults with atopic dermatitis analysis of national health and wellness survey data from France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and the United Kingdom. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:187–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heratizadeh A, Haufe E, Stolzl D, Abraham S, Heinrich L, Kleinheinz A, et al. Baseline characteristics disease severity and treatment history of patients with atopic dermatitis included in the German AD registry TREATgermany. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020 Jun;34((6)):1263–72. doi: 10.1111/jdv.16078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li JC, Fishbein A, Singam V, Patel KR, Zee PC, Attarian H, et al. Sleep disturbance and sleep-related impairment in adults with atopic dermatitis a Cross-sectional Study. Dermatitis. 2018;29:270–7. doi: 10.1097/DER.0000000000000401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ring J, Zink A, Arents BWM, Seitz IA, Mensing U, Schielein MC, et al. Atopic eczema burden of disease and individual suffering − results from a large EU study in adults. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33:1331–40. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tzeng NS, Chang HA, Chung CH, Kao YC, Chang CC, Yeh HW, et al. Increased risk of psychiatric disorders in allergic diseases a Nationwide, Population-Based, Cohort Study. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9:133. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vinnik T, Kreinin A, Abildinova G, Batpenova G, Kirby M, Pinhasov A. Biological sex and IgE sensitization influence severity of depression and cortisol levels in atopic dermatitis. Dermatology. 2020;236:336–44. doi: 10.1159/000504388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hanifin JM, Rajka G. Diagnostic features of atopic dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol. 1980;92:44–7. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Loeffler M, Engel C, Ahnert P, Alfermann D, Arelin K, Baber R, et al. The LIFE-Adult-Study objectives and design of a population-based cohort study with 10,000 deeply phenotyped adults in Germany. BMC public health. 2015;15:691. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1983-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1((3)):385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Luck T, Then FS, Engel C, Loeffler M, Thiery J, Villringer A, et al. (The prevalence of current depressive symptoms in an urban adult population) Psychiatr Prax. 2017;44:148–53. doi: 10.1055/s-0041-111428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zuelke AE, Luck T, Schroeter ML, Witte AV, Hinz A, Engel C, et al. The association between unemployment and depression-results from the population-based LIFE-adult-study. J Affect Disord. 2018;235:399–406. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.04.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bjelland I, Dahl AA, Haug TT, Neckelmann D. The validity of the hospital anxiety and depression scale. An updated literature review. J Psychosom Res. 2002;52:69–77. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(01)00296-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1092–7. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lubben J, Blozik E, Gillmann G, Iliffe S, von Renteln Kruse W, Beck JC, et al. Performance of an abbreviated version of the lubben social network scale among three European community-dwelling older adult populations. Gerontologist. 2006;46:503–13. doi: 10.1093/geront/46.4.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Finlay AY, Khan GK. Dermatology life quality index (DLQI)-a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19:210–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1994.tb01167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article. Further enquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.