Abstract

Objective:

Black Americans who consume alcohol experience worse alcohol-related outcomes. Thus, identifying psycho-sociocultural factors that play a role in hazardous drinking among Black individuals is vital to informing prevention and treatment efforts to reduce these disparities. Racial discrimination is related to hazardous drinking among Black adults, suggesting that some may drink (and continue to drink despite drinking-related problems) to alleviate negative affect (e.g., depression, anxiety) associated with discrimination. Yet, despite the social nature of both racial discrimination and drinking, no known research has examined the role of social anxiety in the relations among racial discrimination experiences and hazardous drinking.

Method:

Participants were 164 Black current drinking undergraduates.

Results:

Racial discrimination was significantly, positively correlated with hazardous drinking, depression, and social anxiety. Discrimination was indirectly related to hazardous drinking via social anxiety, but not depression. Further, discrimination was indirectly related to hazardous drinking via social anxiety alone and via the sequential effects of social anxiety and drinking to cope, but not via coping motives alone. It was also related to hazardous drinking via the sequential effects of depression and drinking to cope but not depression alone. Alternative model testing indicated that social anxiety was not related to hazardous drinking via discrimination, strengthening confidence in directionality of proposed relations.

Conclusions:

Negative affect (social anxiety, depression) appears to be related to hazardous drinking among those who experience more discrimination due in part to drinking to cope. Social anxiety plays an important role in the relation between discrimination and hazardous drinking among Black adults.

Keywords: African American, Black, drinking-related problems, social anxiety, racial discrimination, minority stress

Black1 persons are the second largest racial minority group in the U.S., accounting for over 13% (44 million) of the population (United States Census Bureau, 2019). Black persons evince numerous health inequalities, particularly as it relates to negative consequences associated with alcohol consumption (Chartier & Caetano, 2010). To illustrate, Black individuals evince the greatest increase in average daily volume of alcohol consumed such it is approximately 41% greater than that of White drinkers (Dawson et al., 2015). Further, Black Americans are experiencing increases in drinking frequency and heavy drinking episodes at rates greater than most other racial/ethnic groups (Dawson et al., 2015). And when Black persons experience alcohol use disorder (AUD), their symptoms are more chronic than non-Hispanic/Latinx White individuals (Chartier & Caetano, 2010). The greater rates of alcohol-related problems among Black adults and significant increases in drinking frequency and quantity in this group highlights the importance of identifying contextual and sociocultural factors that play a role in alcohol-related behaviors. Such information is vital to informing theoretical models of alcohol use and related problems among Black adults that could inform treatment and prevention efforts.

Minority Stress Models

Recent work has begun to integrate self-medication-based or coping-based hypotheses of substance use (Khantzian, 2003) such as the affective processing model of negative reinforcement (Baker et al., 2004) with minority stress models (e.g., Meyer, 1995) to help guide research aimed at understanding the experience of race-related stress and trauma on negative alcohol-related outcomes in the Black community (e.g., Boynton et al., 2014; Vaeth et al., 2017) In this context, it is hypothesized that some Black individuals may drink (and continue to drink despite alcohol-related problems) in an attempt to alleviate psychological distress associated with experiences of discrimination. Meta-analytic data indicate that racial discrimination among Black individuals is positively associated with alcohol consumption, heavy/binge drinking, at-risk drinking, and drinking-related problems (Desalu et al., 2019). Racial discrimination is also positively related to developing a variety of negative substance use-related outcomes among Black individuals including increases in substance use and related problems (e.g., Clark et al., 2015; Gibbons et al., 2010; 2004), as well as a greater likelihood of meeting DSM criteria for AUD (Hunte & Barry, 2012). Notably, the relation between racial discrimination and substance use disorder remains after controlling for demographic variables and stressful life events more broadly (Hunte & Barry, 2012).

Although less studied, emerging data are beginning to support the contention that some Black individuals drink to cope with negative affect (NA) that arises after experiencing a discriminatory event, which may increase their hazardous drinking risk. To illustrate, experiences of racism are robustly related to coping-motivated drinking and to drinking-related problems among Black adults (Martin et al., 2003) and undergraduates (Pittman et al., 2019). Further, the relation between racial discrimination and alcohol-related problems was mediated by depression, such that although racial discrimination was robustly related to alcohol problems, it was indirectly related to these problems via depression (Boynton et al., 2014). Prospectively, the relation between racial discrimination and subsequent substance use is mediated by NA (i.e., anxiety and depression) among parents and their children (Gibbons et al., 2004). Among adolescents, racial discrimination was prospectively related to subsequent NA (i.e., anxiety and depression) (Gibbons et al., 2010). Overall, these data provide partial support for the hypothesis that the associations between racial discrimination and negative drinking outcomes are partly explained by some types of NA.

Despite the social nature of racial discrimination and that drinking tends to occur in social situations (e.g., Buckner & Terlecki, 2016), little work has examined the role of social anxiety in these relations. Social anxiety is unique among conditions characterized by NA in that it is characterized by the specific fear of being negatively evaluated by other people. It theoretically follows that experiencing more racial discrimination could lead to a fear of being negatively judged by others, which in turn, could increase the likelihood of drinking to manage these fears and continued drinking despite drinking-related problems. In partial support of this hypothesis, social anxiety is related to experiencing more racial discrimination. To illustrate, among Black Americans, racial discrimination is related to greater odds of social anxiety disorder, even after accounting for variance attributable to age, sex, education, marital status, employment status, and poverty (Levine et al., 2014). Similarly, among Chinese Americans, the relation between racial discrimination and social anxiety is robust, remaining statistically significant after accounting for variance attributable to neuroticism, extraversion, and cultural variables (Fang et al., 2016), suggesting there may be a unique relation of racial discrimination to this socially-oriented type of NA. Further, social anxiety is robustly related to negative drinking outcomes (for review see Buckner, Morris, et al., 2021), including more coping-motivated drinking (e.g., Buckner et al., 2006; Buckner & Shah, 2015; Howell et al., 2016; Terlecki & Buckner, 2015).

Study Aims and Hypotheses

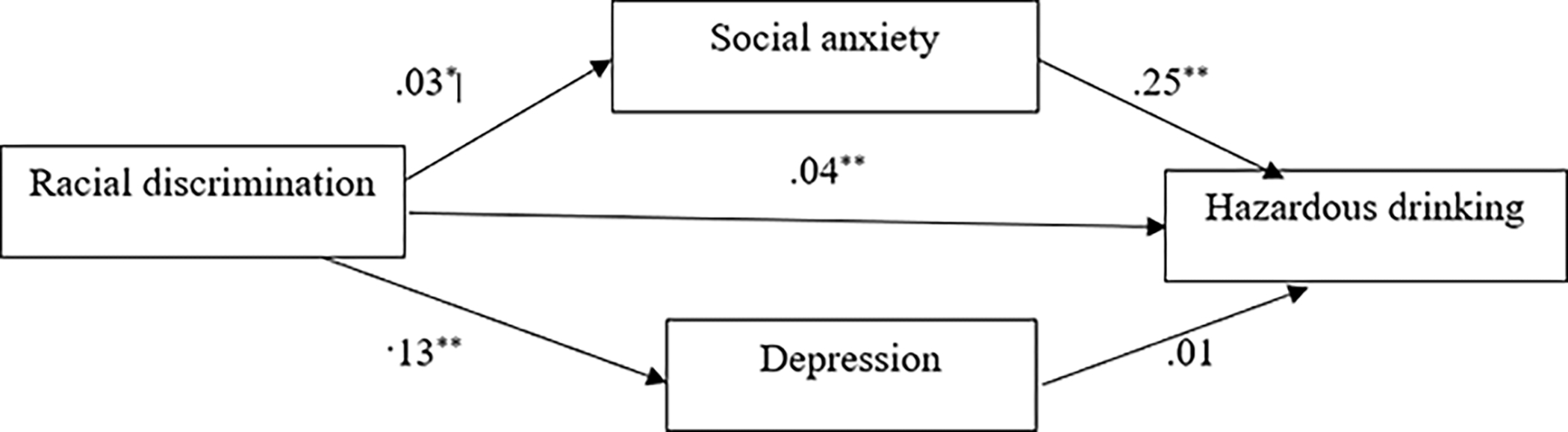

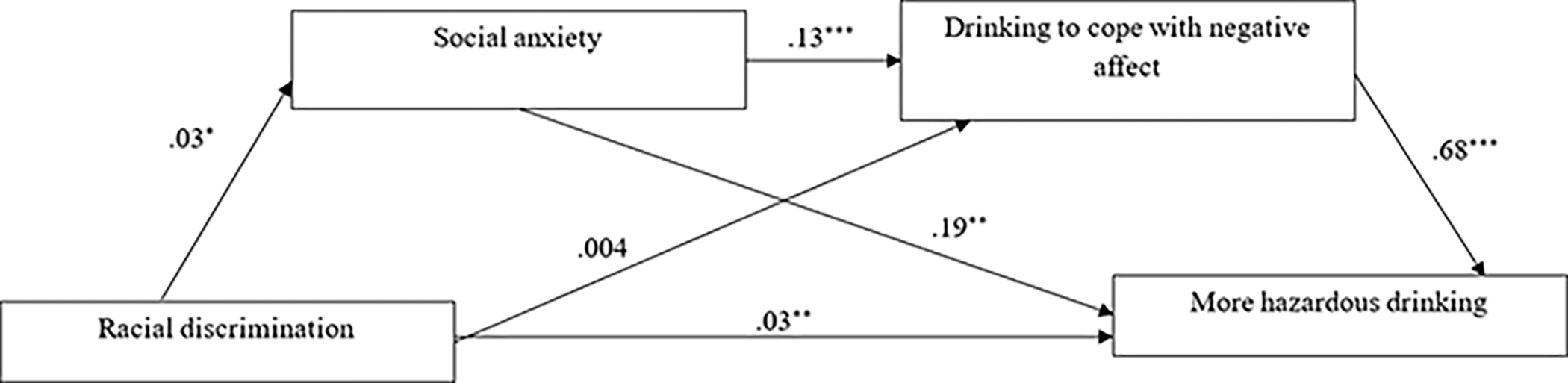

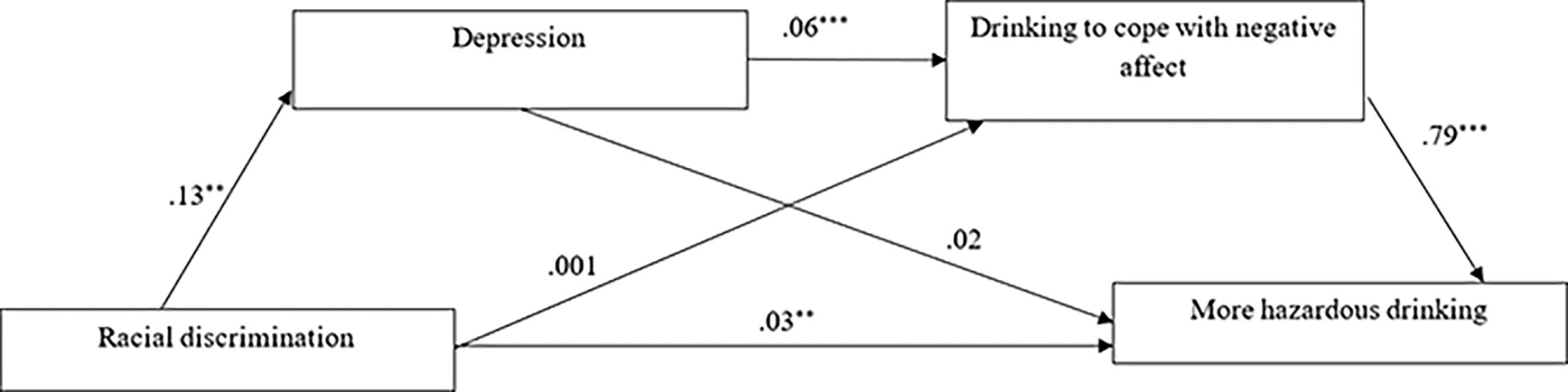

Thus, the current study sought to further understand minority stress-based models of drinking in several ways. First, given that little research has examined whether racial discrimination is related to more social anxiety, we sought to replicate the finding among adults with social anxiety disorder (Levine et al., 2014) that experiencing more racial discrimination would be related to greater social anxiety among alcohol using Black adults regardless of social anxiety disorder status. Second, we tested whether the relation between racial discrimination and hazardous drinking would occur indirectly via social anxiety and whether this relation would remain robust after accounting for variance attributable to depression (Figure 1), given depression is strongly related to racial discrimination (Banks et al., 2006; Brooks et al., 2020; Buckner, Glover, et al., 2021; Hudson et al., 2016). Third, we tested whether the relations between discrimination and hazardous drinking would occur via the sequential effects of social anxiety and drinking to cope (Figure 2). Fourth, we extended prior work finding discrimination to be related to hazardous drinking via depression (Boynton et al., 2014) by testing whether the relations between discrimination and hazardous drinking would also occur via the sequential effects of depression and drinking to cope.

Figure 1.

Hypothesized mediation model of the indirect effect of racial discrimination on hazardous drinking via social anxiety and/or depression. *p<.05, *p<.01, ***p<.001

Figure 2.

Hypothesized mediation model of the indirect effect of racial discrimination on hazardous drinking via the sequential effects of social anxiety and drinking to cope. *p<.05, *p<.01, ***p<.001

Methods

Participants and Procedures

The present sample is a subset of participants from a larger study of mental and physical health among college students at a large, southwestern university. As part of the larger study, participants received extra credit towards their psychology course as compensation and were recruited via flyers and postings on the extra credit website. Inclusion criteria for the larger study included being between ages 18 and 64, identifying with any racial/ethnic group except for those who identified as non-Hispanic/Latin White, and proficiency in English (to ensure comprehension of study questions). Of the 1,451 who completed the survey, 251 identified as Black or African American, 164 (82.9% female) of whom endorsed drinking in the past year on the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT; Saunders et al., 1993) and were thus eligible for the current study. Ages ranged from 18–48 (M = 21.7, SD = 4.3), with 42.8% under the age of 21. The majority were employed either full-time (22.6%) or part-time (40.2%). Regarding drinking behaviors, 55.5% endorsed drinking monthly or less, 32.9% 2–4 times per month, 10.4% 2–3 times per week, and 1.2% 4 or more times per week.

Measures were administered using Qualtrics. Participants provided written informed consent prior to completing the survey. The study was approved by the university’s IRB prior to data collection.

Measures

Perceived Ethnic Discrimination Questionnaire

(PEDQ; Contrada et al., 2001). The PEDQ is a 22-item self-report measure designed to assess perceived racism or ethnic discrimination across racial/ethnic groups. Each item begins with the statement “Because of my ethnicity…” and is followed by a phrase describing a form of ethnic discrimination (e.g., “…others implied I must be dangerous”). Participants rated “How often have you been subjected to offensive ethnic comments aimed directly at you, spoken either in your presence or behind your back?” on a scale of 1 (never) to 7 (very often). The PEDQ has demonstrated adequate internal consistency, good reliability, and discriminant validity in ethnically diverse samples (Contrada et al., 2001) and demonstrated excellent internal consistency in the current study (α = .96).

Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test

(AUDIT; Saunders et al., 1993). The AUDIT is a 10-item measure of alcohol consumption, drinking behaviors, and alcohol-related problems in the past year from 0 to 4. Items were summed and the total score was used, with higher scores indicating more hazardous alcohol use. The AUDIT has demonstrated adequate psychometric properties when used with Black samples (e.g., Cherpitel & Bazargan, 2003; Pittman et al., 2019) and demonstrated good internal consistency in the current study (α = .85).

Coping Motives Scale of the Drinking Motives Questionnaire Revised Short Form

(DMQ-R SF; Kuntsche & Kuntsche, 2009). The DMQ-R SF is a shorter version of the self-report measure, the Drinking Motive Questionnaire Revised (DMQR; Cooper, 1994) on which items are rated on a scale of 1 (never) to 3 (almost always). The three items of the coping motives subscale were summed and used to assess drinking to cope with negative affect. The coping motives subscale has demonstrated adequate internal consistency in prior work (Harbke et al., 2017; Smith et al., 2018) and in our sample (α = .86).

Affect.

The 20-item general depression (e.g., “I felt depressed”) and the 5-item social anxiety (e.g., “I was worried about embarrassing myself socially”) subscales of the Inventory of Depression and Anxiety Symptoms (IDAS; Watson et al., 2007) assessed these constructs over the past two weeks, including today. IDAS items were rated from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely). These subscales demonstrate good convergent and discriminant validity with diagnoses of major depressive disorder and social anxiety disorder, respectively (Watson et al., 2008). The depression (α = .90) and social anxiety (α = .90) subscales demonstrated excellent internal consistency in the current sample.

Data Analytic Strategy

Analyses were conducted in SPSS 26. First, zero-order correlations among study variables were examined. Second, a multiple mediator model (see Figure 1 for illustrative example) was conducted to test whether experiencing more discrimination was associated with more hazardous drinking indirectly via social anxiety and/or depression. Next, two serial multiple mediator model tested the impact of social anxiety or depression and drinking to cope with NA as mediators of the relation between racial discrimination and hazardous drinking (Figures 2 and 3). Hayes (2013) describes this type of model as a serial multiple mediator model, in which the independent variable can impact the dependent variable through four pathways: directly and/or indirectly via social anxiety/depression only, via coping motives only, and/or via both sequentially, with social anxiety/depression impacting coping motives. Although mediation models are ideally tested using prospective data, cross-sectional tests of putative indirect effects can be an important first step (Hayes, 2018). This analysis was conducted using PROCESS, a conditional process modeling program that utilizes an ordinary least squares-based path analytical framework to test for both direct and indirect effects (Hayes, 2018). All specific and conditional indirect effects were subjected to follow-up bootstrap analyses with 10,000 resamples from which a 95% confidence interval (CI) was estimated (Hayes, 2009; Preacher & Hayes, 2004, 2008). Four participants were missing data concerning racial discrimination; thus analyses using this variable were conducted with 160 participants. Bias-corrected bootstrapping is the most powerful method for testing this type of model with smaller sample sizes; moderate to large effect sizes can be observed with samples smaller than the current sample (Fritz & Mackinnon, 2007) and power analyses (Schoemann et al., 2017) indicate that our sample is sufficient to achieve power of .80 to test the hypothesized serial relations.

Figure 3.

Hypothesized mediation model of the indirect effect of racial discrimination on hazardous drinking via the sequential effects of depression and drinking to cope. *p<.05, *p<.01, ***p<.001

Results

Correlations among Study Variables

Means, standard deviations (SD), and bivariate correlations among study variables appear in Table 1. Experiences of racial discrimination were significantly, positively correlated with hazardous drinking, depression, and social anxiety. Hazardous drinking was also significantly correlated with depression, social anxiety, and coping motives. Depression and social anxiety were both significantly correlated with coping motives.

Table 1.

Means, standard deviations, and correlations among study variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | M | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| 1. Racial Discrimination | - | 60.78 | 27.61 | ||||

| 2. Hazardous Drinking | .27** | - | 4.88 | 4.46 | |||

| 3. Depression | .24** | .26** | - | 47.83 | 14.45 | ||

| 4. Social Anxiety | .17* | .34** | .62** | - | 10.12 | 5.15 | |

| 5. Drinking to Cope | .13 | .36** | .46** | .37** | - | 4.68 | 1.87 |

Note.

p <.05.

p < .01.

Mediation Models

The full model with depression and social anxiety as the putative mediators significantly predicted hazardous drinking severity, R2 = .17, F(3, 156) = 10.73, p < .001 (Figure 1). When entered simultaneously, racial discrimination and social anxiety (but not depression) remained significantly correlated with hazardous drinking severity. Discrimination frequency was related to hazardous drinking severity indirectly via social anxiety, b = .008, SE = .005, 95% CI: [.0003, .0194], but not depression, b = .002, SE = .003, 95% CI: [−.0047, .0077].

Given the limitations of testing mediation using cross-sectional data, we tested an alternative temporal pattern – that social anxiety may lead to more racial discrimination which in turn could result in more hazardous drinking. Depression was included as a covariate to account for shared variance. This indirect effect was not significant, b = .008, SE = .018, 95% CI: [−.028, .046], strengthening confidence in directionality of proposed relations that discrimination may lead to social anxiety which in turn may result in more hazardous drinking.

Sequential Mediation Model

We tested whether the relation of racial discrimination and hazardous drinking occurred via the sequential effects of social anxiety and drinking to cope (Figure 2). The full model with predictor and putative mediators predicted statistically significant variance in hazardous drinking severity, R2 = .24, F(3, 156) = 15.99, p <.001, and all predictor variables remained significantly related to hazardous drinking. Racial discrimination was indirectly related to more hazardous drinking via social anxiety alone, b = .006, SE = .004, 95% CI: [.0002, .0148], and via the sequential effects of social anxiety and coping motives, b = .003, SE = .002, 95% CI: [.0001, .0070], but not via coping motives alone, b = .003, SE = .004, 95% CI: [−.005, .010].

We next tested whether the relation of racial discrimination and hazardous drinking occurred via the sequential effects of depression and drinking to cope (Figure 3). The full model with predictor and putative mediators predicted statistically significant variance in hazardous drinking severity, R2 = .20, F(3, 156) = 13.01, p <.001, and discrimination and coping motives, but not depression, remained significantly related to hazardous drinking. Racial discrimination was indirectly related to more hazardous drinking via the sequential effects of depression and coping motives, b = .006, SE = .003, 95% CI: [.0009, .0126], but not via depression, b = .003, SE = .003, 95% CI: [−.0029, .0094], or coping motives alone, b = .001, SE = .004, 95% CI: [−.0081, .0085].

Discussion

This is the first known study of the test of the role of social anxiety on the relation between racial discrimination experiences and hazardous drinking among Black alcohol users. Consistent with hypotheses and with prior work in other samples (e.g., Fang et al., 2016; Levine et al., 2014), experiencing more racial discrimination was significantly correlated with greater social anxiety in our sample of alcohol using Black adults. The current study extends that literature by determining that the relation between racial discrimination and hazardous drinking occurred indirectly via social anxiety; this relationship remained after accounting for variance attributable to depression. In fact, the relation between discrimination and hazardous drinking did not occur indirectly via depression after accounting for social anxiety, suggesting that social anxiety may be an especially important affect-related variable to consider in models of discrimination’s impact on hazardous drinking.

Another notable contribution of this study is that this is the first known test of the serial impact of NA and coping motivated drinking on the relation of racial discrimination and hazardous drinking. We found that the relations between discrimination and hazardous drinking occurred indirectly via social anxiety even after accounting for variance attributable to coping motivated drinking, and that the relation between discrimination and hazardous drinking also occurred via the sequential effects of social anxiety and drinking to cope. Further, results extend prior work indicating that the relation between discrimination and hazardous drinking occurs indirectly via depression, presumably via drinking to manage depression (Boynton et al., 2014), by testing that hypothesis and determining that in support of that hypothesis, the relation between discrimination and hazardous drinking also occurred via the sequential effects of depression and drinking to cope. Together, these findings indicate that NA plays an important role in these relations at least in part due to drinking to cope with these types of NA. This is especially important given that episode-specific coping motives are related to more alcohol consumption among Black young adults (O’Hara et al., 2014).

Findings have important clinical implications. First, as experiences of racial discrimination and social anxiety were significantly related to hazardous drinking severity, clinicians working with Black clients endorsing alcohol use may consider assessing and addressing the impact of racial discrimination to determine whether the Engaging, Managing, and Bonding through Race (EMBRace) intervention (Anderson et al., 2019) may be useful. The EMBRace intervention was designed to combat instances of racial discrimination, stress, and trauma via teaching Black families about helpful techniques to minimize the negative effects of racial distress (Anderson et al., 2019). Pilot data demonstrate that EMBRace may increase psychological wellbeing, including during experiences of increased racial stress among Black adolescents (Anderson et al., 2018). Second, given that racial discrimination and hazardous drinking were indirectly related via the sequential effects of social anxiety and drinking to cope, clinicians may also consider teaching patients more effective means to manage social anxiety than drinking, such as cognitive behavioral skills to manage social anxiety (Hope et al., 2010).

Findings should be considered in the context of some limitations of the study design. First, data were correlational; although we tested an alternate model of the proposed relations, prospective and experimental work will be an important next step to determine causality. Second, data were collected using retrospective self-reports, and future work could benefit from multi-method (e.g., ecological momentary assessment of in vivo relations among racial discrimination and drinking behaviors, biological verification of drinking), multi-informant (e.g., collateral reports of drinking behaviors) approaches. Third, the sample was predominantly female, all participants were in college psychology courses, and participants were those seeking extra credit in these courses; thus, future work is necessary to test whether results generalize to men, other age groups, those who do not chose to participate in extra credit activities, and those with other educational backgrounds, including those who do not take psychology courses. Future work may also consider whether results vary as a function of age, sex, etc. Fourth, the sample was non-treatment-seeking, and future work is necessary to test whether results generalize to those meeting criteria for AUD as well as to test the impact of these variables on the course of treatment. Fifth, the current study focused on social anxiety given the social nature of racial discrimination; however, future work could benefit from testing whether observed relations are specific to social anxiety or also occur for other types of anxiety. Despite these limitations, results highlight the important role of social anxiety in theoretical models of minority stress-based models of hazardous drinking among Black drinkers.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to the University of Houston under Award Number U54MD015946. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Buckner receives funding from the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services’ Graduate Psychology Education (GPE) Program (Grant D40HP33350). The contents are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of, nor an endorsement, by HRSA/HHS, or the U.S. Government.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest

The authors report that they have no conflict of interest.

The term Black is used in the current paper to describe people of African ancestry. The term Black is used rather than African American to include individuals who may identify with other national origins (e.g., Bahamian, Jamaican) per the American Psychological Association (2020).

Contributor Information

Julia D. Buckner, Louisiana State University.

Nina I. Glover, Louisiana State University

Justin M. Shepherd, University of Houston

Michael J. Zvolensky, University of Houston, University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center

References

- Anderson RE, Jones SCT, Navarro CC, McKenny MC, Mehta TJ, & Stevenson HC (2018). Addressing the mental health needs of Black American youth and families: A case study from the EMBRace intervention. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(5), 898. 10.3390/ijerph15050898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson RE, McKenny MC, & Stevenson HC (2019). EMBRace: Developing a racial socialization intervention to reduce racial stress and enhance racial coping among Black parents and adolescents. Family Process, 58(1), 53–67. 10.1111/famp.12412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker TB, Piper ME, McCarthy DE, Majeskie MR, & Fiore MC (2004). Addiction motivation reformulated: An affective processing model of negative reinforcement. Psychological Review, 111(1), 33–51. 10.1037/0033-295x.111.1.33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks KH, Kohn-Wood LP, & Spencer M (2006). An examination of the African American experience of everyday discrimination and symptoms of psychological distress. Community Mental Health Journal, 42(6), 555–570. 10.1007/s10597-006-9052-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boynton MH, O’Hara RE, Covault J, Scott D, & Tennen H (2014). A mediational model of racial discrimination and alcohol-related problems among African American college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 75(2), 228–234. 10.15288/jsad.2014.75.228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks JR, Hong JH, Madubata IJ, Odafe MO, Cheref S, & Walker RL (2020). The moderating effect of dispositional forgiveness on perceived racial discrimination and depression for African American adults. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 10.1037/cdp0000385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner JD, Eggleston AM, & Schmidt NB (2006). Social anxiety and problematic alcohol consumption: The mediating role of drinking motives and situations. Behavior Therapy, 37(4), 381–391. 10.1016/j.beth.2006.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner JD, Glover NI, Dean KE, & Abarno CN (2021). Racial discrimination and substance-related problem severity among Black young adults: A test of the minority stress model [Unpublished mansucript submitted for publication].

- Buckner JD, Morris PE, Abarno CN, Glover NI, & Lewis EM (2021). Biopsychosocial model social anxiety and substance use revised. Current Psychiatry Reports, 23(6). 10.1007/s11920-021-01249-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner JD, & Shah SM (2015). Fitting in and feeling fine: conformity and coping motives differentially mediate the relationship between social anxiety and drinking problems for men and women. Addiction Research and Theory, 23(3), 231–237. 10.3109/16066359.2014.978304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner JD, & Terlecki MA (2016). Social anxiety and alcohol-related impairment: The mediational impact of solitary drinking. Addictive Behaviors, 58, 7–11. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.02.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chartier K, & Caetano R (2010). Ethnicity and health disparities in alcohol research. Alcohol research & health : the journal of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 33(1–2), 152–160. http://libezp.lib.lsu.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=cmedm&AN=21209793&site=ehost-live&scope=site [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherpitel CJ, & Bazargan S (2003). Screening for alcohol problems: comparison of the AUDIT, RAPS4 and RAPS4-QF among African American and Hispanic patients in an inner city emergency department. Drug and alcohol dependence, 71(3), 275–280. 10.1016/S0376-8716(03)00140-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark TT, Salas-Wright CP, Vaughn MG, & Whitfield KE (2015). Everyday discrimination and mood and substance use disorders: A latent profile analysis with African Americans and Caribbean Blacks. Addictive Behaviors, 40, 119–125. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.08.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contrada RJ, Ashmore RD, Gary ML, Coups E, Egeth JD, Sewell A, Ewell K, Goyal TM, & Chasse V (2001). Measures of ethnicity-related stress: Psychometric properties, ethnic group differences, and associations with well-being. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 31(9), 1775–1820. 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2001.tb00205.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML (1994). Motivations for alcohol use among adolescents: Development and validation of a four-factor model. Psychological assessment, 6(2), 117–128. http://libezp.lib.lsu.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=psyh&AN=1994-40642-001&site=ehost-live&scope=site [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DA, Goldstein RB, Saha TD, & Grant BF (2015). Changes in alcohol consumption: United States, 2001–2002 to 2012–2013. Drug and alcohol dependence, 148, 56–61. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.12.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desalu JM, Goodhines PA, & Park A (2019). Racial discrimination and alcohol use and negative drinking consequences among Black Americans: a meta-analytical review. Addiction (Abingdon, England), 114(6), 957–967. 10.1111/add.14578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang K, Friedlander M, & Pieterse AL (2016). Contributions of acculturation, enculturation, discrimination, and personality traits to social anxiety among Chinese immigrants: A context-specific assessment. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 22(1), 58–68. 10.1037/cdp0000030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritz MS, & Mackinnon DP (2007). Required sample size to detect the mediated effect. Psychological Science 18(3), 233–239. 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01882.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons FX, Etcheverry PE, Stock ML, Gerrard M, Weng CY, Kiviniemi M, & O’Hara RE (2010). Exploring the link between racial discrimination and substance use: What mediates? What buffers? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 99, 785–801. 10.1037/a0019880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons FX, Gerrard M, Cleveland MJ, Wills TA, & Brody G (2004). Perceived discrimination and substance use in African American parents and their children: A panel study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 86(4), 517. 10.1037/0022-3514.86.4.517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harbke CR, Laurent J, & Catanzaro SJ (2017). Comparison of the original and short form Drinking Motives Questionnaire-Revised with high school and underage college student drinkers. Assessment, 26(7), 1179–1193. 10.1177/1073191117731812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF (2009). Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Communication Monographs, 76(4), 408–420. 10.1080/03637750903310360 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hope DA, Heimberg RG, & Turk CL (2010). Managing social anxiety: A cognitive-behavioral therapy approach (Therapist Guide, 2nd edition). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Howell AN, Buckner JD, & Weeks JW (2016). Fear of positive evaluation and alcohol use problems among college students: the unique impact of drinking motives. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping, 29(3), 274–286. 10.1080/10615806.2015.1048509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson DL, Neighbors HW, Geronimus AT, & Jackson JS (2016). Racial discrimination, John Henryism, and depression among African Americans. The Journal of Black Psychology, 42(3), 221–243. 10.1177/0095798414567757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunte HER, & Barry AE (2012). Perceived discrimination and DSM-IV–based alcohol and illicit drug use disorders. American journal of public health, 102(12), e111–e117. 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khantzian E (2003). Understanding addictive vulnerability: An evolving psychodynamic perspective. Neuropsychoanalysis, 5(1), 5–21. 10.1080/15294145.2003.10773403 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche E, & Kuntsche S (2009). Development and validation of the Drinking Motive Questionnaire Revised Short Form (DMQ-R SF). Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 38(6), 899–908. 10.1080/15374410903258967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine DS, Himle JA, Abelson JM, Matusko N, Dhawan N, & Taylor RJ (2014). Discrimination and social anxiety disorder among African-Americans, Caribbean Blacks, and Non-Hispanic Whites. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 202(3), 224–230. 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin JK, Tuch SA, & Roman PM (2003). Problem drinking patterns among African Americans: The impacts of reports of discrimination, perceptions of prejudice, and “risky” coping strategies. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 44(3), 408–425. 10.2307/1519787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH (1995). Minority stress and mental health in gay men. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 36(1), 38–56. 10.2307/2137286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Hara RE, Boynton MH, Scott DM, Armeli S, Tennen H, Williams C, & Covault J (2014). Drinking to cope among African American college students: An assessment of episode-specific motives. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 28(3), 671–681. 10.1037/a0036303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pittman DM, Brooks JJ, Kaur P, & Obasi EM (2019). The cost of minority stress: Risky alcohol use and coping-motivated drinking behavior in African American college students. Journal of ethnicity in substance abuse, 18(2), 257–278. 10.1080/15332640.2017.1336958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, & Hayes AF (2004). SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments & Computers, 36(4), 717–731. 10.3758/BF03206553 (Web-based archive of norms, stimuli, and data: Part 2) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, & Hayes AF (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40(3), 879–891. 10.3758/BRM.40.3.879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, De La Fuente JR, & Grant M (1993). Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption--II. Addiction, 88(6), 791–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoemann AM, Boulton AJ, & Short SD (2017). Determining power and sample size for simple and complex mediation models. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 8(4), 379–386. 10.1177/1948550617715068 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith LJ, Gallagher MW, Tran JK, & Vujanovic AK (2018). Posttraumatic stress, alcohol use, and alcohol use reasons in firefighters: The role of sleep disturbance. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 87, 64–71. 10.1016/j.comppsych.2018.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terlecki MA, & Buckner JD (2015). Social anxiety and heavy situational drinking: Coping and conformity motives as multiple mediators. Addictive Behaviors, 40(0), 77–83. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.09.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Census Bureau. (2019). QuickFacts: United States. Retrieved 5/12/21 from https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045219

- Vaeth PAC, Wang-Schweig M, & Caetano R (2017). Drinking, Alcohol Use Disorder, and Treatment Access and Utilization Among U.S. Racial/Ethnic Groups. Alcoholism, clinical and experimental research, 41(1), 6–19. 10.1111/acer.13285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, O’Hara MW, Chmielewski M, McDade-Montez EA, Koffel E, Naragon K, & Stuart S (2008). Further validation of the IDAS: Evidence of convergent, discriminant, criterion, and incremental validity. Psychological assessment, 20(3), 248–259. 10.1037/a0012570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, O’Hara MW, Simms LJ, Kotov R, Chmielewski M, McDade-Montez EA, Gamez W, & Stuart S (2007). Development and validation of the Inventory of Depression and Anxiety Symptoms (IDAS). Psychological assessment, 19(3), 253–268. 10.1037/1040-3590.19.3.253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]