Abstract

The organometallic H-cluster of the [FeFe]-hydrogenase consists of a [4Fe–4S] cubane bridged via a cysteinyl thiolate to a 2Fe subcluster ([2Fe]H) containing CO, CN−, and dithiomethylamine (DTMA) ligands. The H-cluster is synthesized by three dedicated maturation proteins: the radical SAM enzymes HydE and HydG synthesize the non-protein ligands, while the GTPase HydF serves as a scaffold for assembly of [2Fe]H prior to its delivery to the [FeFe]-hydrogenase containing the [4Fe–4S] cubane. HydG uses l-tyrosine as a substrate, cleaving it to produce p-cresol as well as the CO and CN− ligands to the H-cluster, although there is some question as to whether these are formed as free diatomics or as part of a [Fe(CO)2(CN)] synthon. Here we show that Clostridium acetobutylicum (C.a.) HydG catalyzes formation of multiple equivalents of free CO at rates comparable to those for CN− formation. Free CN− is also formed in excess molar equivalents over protein. A g = 8.9 EPR signal is observed for C.a. HydG reconstituted to load the 5th “dangler” iron of the auxiliary [4Fe–4S][FeCys] cluster and is assigned to this “dangler-loaded” cluster state. Free CO and CN− formation and the degree of activation of [FeFe]-hydrogenase all occur regardless of dangler loading, but are increased 10–35% in the dangler-loaded HydG; this indicates the dangler iron is not essential to this process but may affect relevant catalysis. During HydG turnover in the presence of myoglobin, the g = 8.9 signal remains unchanged, indicating that a [Fe(CO)2(CN)(Cys)] synthon is not formed at the dangler iron. Mutation of the only protein ligand to the dangler iron, H272, to alanine nearly completely abolishes both free CO formation and hydrogenase activation, however results show this is not due solely to the loss of the dangler iron. In experiments with wild type and H272A HydG, and with different degrees of dangler loading, we observe a consistent correlation between free CO/CN− formation and hydrogenase activation. Taken in full, our results point to free CO/CN−, but not an [Fe(CO)2(CN)(Cys)] synthon, as essential species in hydrogenase maturation.

Introduction

The [FeFe]-hydrogenase catalyzes the simplest of enzymatic reactions, the reversible reduction of protons to H2, i.e. 2H+ + 2e− ↔ H.1,2 This reaction is important to the metabolism of a variety of microbes, in pathways that utilize H2 oxidation as a source of energy, or alternatively in pathways that use proton reduction to capture reducing equivalents generated during processes such as photosynthesis and fermentation.2 The ability of [FeFe]-hydrogenase to rapidly reduce protons to the green fuel H2 has generated interest in the development of potential biotechnological applications of the enzyme, although commercial implementation is hindered by challenges such as constructing H2-evolving microorganisms that are compatible with oxygenic photosynthesis, and/or coupling electron flow more effectively to H2 production. 3–13 At a more fundamental level, detailed structural and mechanistic studies of the [FeFe]-hydrogenase are needed to establish the chemical basis of catalysis to help inform the development of new hydrogen production catalysts.1,3,14–22

The active site of [FeFe]-hydrogenase (HydA) contains a biologically unique organometallic cluster known as the H-cluster, consisting of a [4Fe–4S] cubane bridged via a cysteinyl thiolate ligand to a binuclear iron subcluster ([2Fe]H) coordinated by CO, CN−, and dithiomethylamine (DTMA) ligands.2,23 The interconversion of protons and H2 occurs at the distal iron of the [2Fe]H.1,24–26 While the [4Fe–4S] subcluster of the H-cluster is built by the housekeeping iron–sulfur cluster machinery,27–29 assembly of the [2Fe]H requires three dedicated [FeFe]-hydrogenase maturation enzymes denoted HydE, HydF, and HydG;30,31 when hydA is expressed heterologously in the absence of hydE, hydF, and hydG, the resulting [FeFe]-hydrogenase (designated HydAΔEFG, Table S1†) lacks the [2Fe]H and exhibits no catalytic activity.32–34

Sequence analysis and in vivo and in vitro biochemical studies have offered insight relating to the specific roles of the three Hyd maturation enzymes.35,36 HydF is a cation-activated GTPase that serves as a scaffold for assembly of a 2Fe precursor of the H-cluster, referred to as [2Fe]F.37–40 This [2Fe]F-loaded HydF can be generated when HydF is co-expressed with HydE and HydG, and then purified out of the cell lysate using affinity chromatography.38,39,41–43 The resulting purified protein, referred to as HydFEG, has been shown using FTIR to harbor a CO and CN− ligated [2Fe]F that is most likely bridged via one of the CN− ligands to a [4Fe–4S] cluster on HydF.43 Purified HydFEG dimer is able to transfer the [2Fe]F to HydAΔEFG to generate the active hydrogenase in a step that is not dependent on GTP hydrolysis.39,44 The GTPase domain of HydF has been shown to act as a molecular switch.45 Multiple reports have provided additional support for the role of HydF as a scaffold, via the ability of dimeric HydFΔEG to capture synthetic 2Fe precursor clusters ([2Fe]MIM) that can subsequently be transferred to HydAΔEFG.21,46 These reports have lent important insights on [2Fe]MIM transfer and rearrangement during the final step of maturation to yield the Hox state of HydA.46–48

HydE and HydG are radical SAM (RS) enzymes, catalyzing the regiospecific S–C5′ homolytic bond cleavage of SAM,49 during synthesis of the non-protein ligands of the H-cluster. While the reaction catalyzed by HydE has not been explicitly determined, it is believed to synthesize the DTMA ligand of the H-cluster from an as-yet unidentified substrate;50–52 recently cysteine and serine have been implicated as the sources of sulfur and C–N–C fragments of DTMA, respectively.53,54 HydG uses tyrosine as a substrate, cleaving it to produce p-cresol and dehydroglycine (DHG), with the latter ultimately forming CO and CN−.55–59 The initial cleavage of tyrosine occurs at the N-terminal RS [4Fe–4S] cluster, where the SAM-derived deoxyadenosyl radical is believed to abstract a hydrogen atom from the amino of tyrosine, leading to Cα–Cβ bond cleavage to produce p-cresol and DHG (Fig. 1).59–64 The DHG travels through a channel towards an auxiliary iron–sulfur ([Fe–S]) cluster near the C-terminus of the protein (AUX cluster, Fig. 1), and is converted to CO and CN− at or near this [Fe–S] cluster.63,65 Based on a combination of structural and spectroscopic studies of HydG, this C-terminal cluster has been proposed to be a novel [4Fe–4S][FeCys] species, in which an S = 1/2 [4Fe–4S]+ cluster is bridged to a “dangler” Fe(II) via a (non-protein) cysteine ligand to give an S = 5/2 cluster (Fig. 1).65–67 It has been suggested that the CO and CN− formed by DHG breakdown bind to the dangler iron, and a second tyrosine turnover results in binding of a second CO to form “complex B” (a species with two CO and a CN− bound to the dangler iron), while the second CN− liberates the dangler Fe from the C-terminal [4Fe–4S] cluster to generate a [Fe(CO)2(CN)(Cys)] synthon.66–69 While the enzymatic fate of the HydG product has yet to be determined, it was recently reported that a synthetic [FeII(CO)2(CN)(Cys)] species is acted on by HydE to generate a mononuclear [FeI(CO)2(CN)(S)] species that could serve as the precursor to the dinuclear FeIFeI center of [2Fe]H in HydA.70

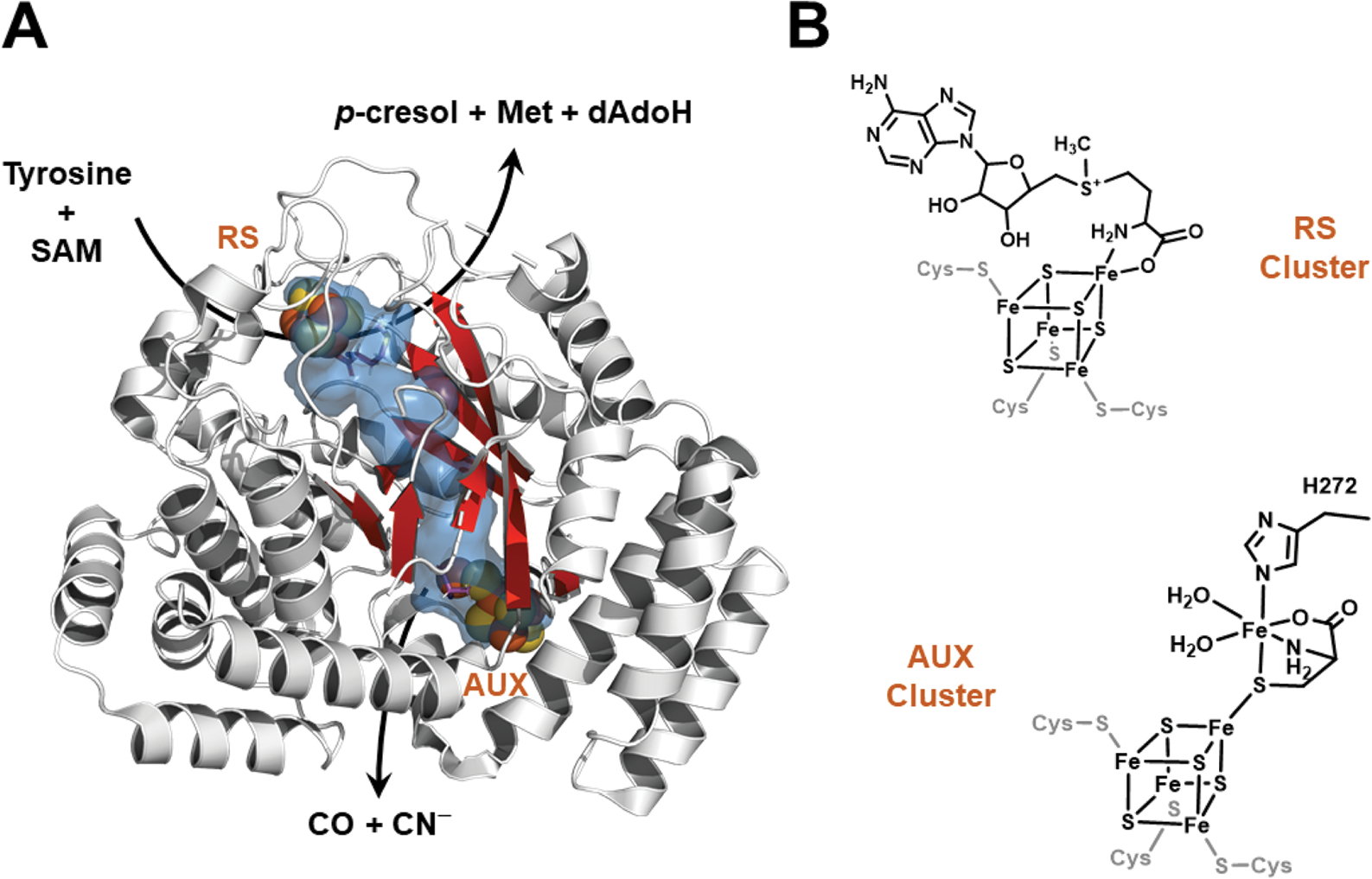

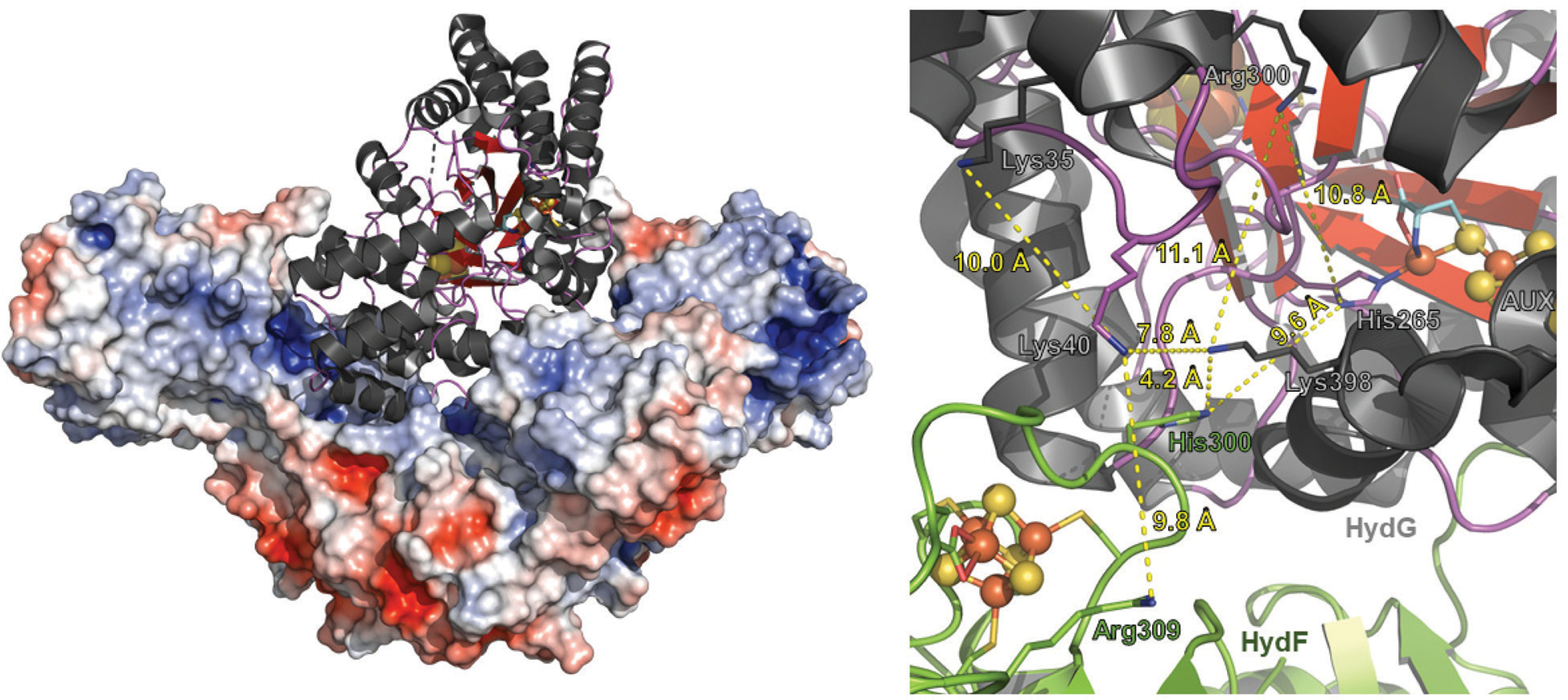

Fig. 1.

HydG structure (left) and iron–sulfur cluster states (right). A. The X-ray crystal structure of Thermoanaerobacter italicus HydG (4WCX.pdb). The radical SAM [4Fe−4S] cluster where tyrosine is cleaved to p-cresol and dehydroglycine (DHG) is at the top of the barrel and is denoted by “RS”, while the auxiliary cluster is located 24 Å away at the bottom of the barrel (denoted by “AUX”). The internal cavity calculation (shown in blue) was performed with Pymol (PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 2.2.3 Schrödinger, LLC) using the Caver3 plugin; this internal tunnel connects solvent (near the RS cluster) to the AUX cluster, and is the proposed pathway by which DHG migrates from the RS to the AUX clusters. Residues 315–325 are not displayed because the helix they form hides the β-barrel, and thus precludes observation of the internal tunnel. B. Line drawings of the RS and AUX clusters of HydG. The conserved His272 residue that provides the only HydG-derived ligand to the dangler Fe is highlighted (amino acid numbering corresponds to Clostridium acetobutylicum).

Here we examine details of the HydG-catalyzed reaction during [FeFe]-hydrogenase maturation, with a specific focus on the role of the C-terminal [Fe–S] cluster and the dangler iron. We find that Clostridium acetobutylicum (C.a.) HydG catalyzes the synthesis of multiple equivalents of free CO and CN− at rates that are moderately increased in enzyme containing the dangler iron. Furthermore, we find that in vitro hydrogenase maturation is not dependent on the presence of the HydG dangler iron, and the spectroscopic properties of the dangler iron are unaffected during HydG turnover. The implications of these results in light of the current models for [FeFe]-hydrogenase maturation are discussed.

Results

Optimization of the detection of free CO

HydG catalyzes the production of CO from substrate l-tyrosine, as we previously demonstrated by detecting the binding of free CO produced during HydG turnover to human deoxyhemoglobin.57 These experimental results showed substoichiometric free CO formation by HydG; for example, reconstituted C.a. HydG with a full complement of [4Fe–4S] clusters produced 0.17 equivalents (relative to protein) of free CO in 30 minutes. We and others hypothesized that the low levels of free CO formation relative to other reaction products (deoxyadenosine, p-cresol, CN−) could be due to sequestration of some CO within HydG itself.57,59,68 Subsequent published work on Shewanella oneidensis (S.o.) HydG provided evidence for CO binding to an iron of the C-terminal [Fe–S] cluster to form a synthon;68 it was proposed that this synthon, [Fe(CO)2(CN) (Cys)], rather than free CO and CN−, is the relevant product of HydG, and that any free CO observed was off-pathway and presumably linked to degradation of “complex B”.66–68 In order to further explore the functional relevance of free CO produced by HydG, we have undertaken optimization of our HydG CO assay, and exploration of the factors involved in free CO formation and its relationship to [FeFe]-hydrogenase activation.

Buffer composition impacts the amount of HydG-generated CO detected in experiments using human deoxyhemoglobin as the reporter molecule (Fig. S1†). For example, phosphate buffers inhibited CO production at a range of pH values (Fig. S1†) and in a concentration dependent manner (Fig. S2†). Since phosphate was used in our early HydG-catalyzed CN− formation assays with no apparent inhibitory effect,56 we conclude that the phosphate anion inhibits or interferes with the mechanism of CO formation at the auxiliary cluster, but not in the steps of HydG catalysis that produce p-cresol and CN−. These results are consistent with there being distinct active sites for CN− and CO production, as previously proposed.64 We subsequently determined that HEPES or Tris buffers at basic pH with low salt and low/no glycerol provided optimal experimental conditions for CO assays (Fig. S1†). The detection of HydG-produced CO has been further improved by use of the H64L variant of sperm whale myoglobin (H64L Mb), which has a significantly greater CO binding affinity than human hemoglobin,71–73 and thus allows more efficient detection of HydG-catalyzed CO formation (Fig. S3 and S4†). These optimized assay conditions were employed as we moved forward with examining the kinetics of CO formation in various HydG preparations.

Kinetics of HydG-catalyzed CO formation

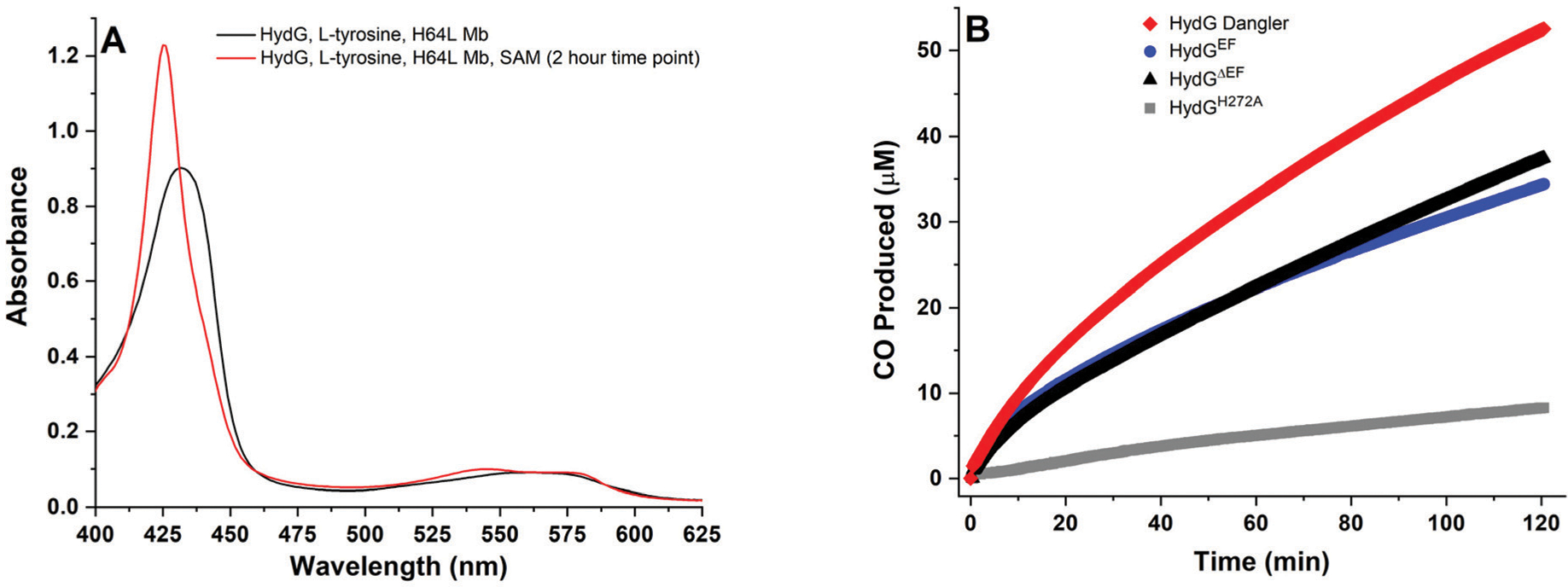

HydG-catalyzed CO formation is biphasic, based on single wavelength experiments (425 nm) under optimized assay conditions (Fig. 2). The initial linear phase exhibits an apparent kcat value that ranges between 0.084–0.097 min−1 in different HydG preparations, while the second phase apparent kcat ranges between 0.035–0.053 min−1 (Table 1). These free CO formation rates are higher than those we originally reported (0.068 min−1 and 0.010 min−1),57 and are similar to the rates we observed for free CN− production (0.036–0.12 min−1).56,60 Precise correlation of the CO and CN− rates is challenging, however, as we cannot simultaneously detect free CO and CN− in situ; rather, while CO is detected in real time by including H64L Mb in the assay and monitoring spectroscopic changes, CN− quantification requires taking time point aliquots, denaturing and precipitating the HydG, derivatizing the product to 1-cyanobenz[f]isoindole, and analysis by LC-MS.56,60 Despite these difficulties, the CO and CN− assay results are consistent with a 1 : 1 correspondence between free CO and CN− formation during HydG catalysis, as expected based on the stoichiometry of tyrosine breakdown. Further discussion of CN− detection during HydG turnover is provided in a later section of this paper.

Fig. 2.

HydG catalyzed CO formation, as monitored via the spectroscopic changes associated with CO binding to deoxy H64L myoglobin at 37 °C. A. H64L myoglobin (80 μM heme) in the presence of 8 mM DT, 600 μM l-tyrosine, and WT dangler reconstituted HydGΔEF (10 μM protein with 8.23 ± 0.43 Fe per protein). Black spectrum, mixture before addition of 1 mM SAM; red spectrum, 2 hours after SAM was added to initiate catalysis. B. CO formed during turnover experiments as monitored via single wavelength kinetics at λ = 425 nm at 37 °C in 50 mM Tris, 10 mM KCl, pH 8.1 buffer. Traditionally reconstituted H272A HydGΔEF (gray, 25 μM protein with 7.65 ± 0.26 Fe per protein); WT traditionally reconstituted HydGΔEF (black, 10 μM protein with 7.54 ± 0.48 Fe per protein); WT traditionally reconstituted HydGEF (blue, 10 μM protein with 7.38 ± 0.40 Fe per protein); and WT dangler reconstituted HydGΔEF (red, 10 μM protein with 8.23 ± 0.43 Fe per protein).

Table 1.

HydG rates for free CO formation as monitored via single wavelength kinetics experiments (λ = 425 nm, see Fig. 2)

| Enzyme | Burst phasee (min−1) | Biphasic, rate 1 f (min−1) | Biphasic, rate 2 f (min−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| HydGΔEF a | 0.0836 ± 0.0022 | 0.0658 ± 0.0034 | 0.0370 ± 0.0079 |

| HydGEF b | 0.0973 ± 0.0193 | 0.0637 ± 0.0046 | 0.0348 ± 0.0052 |

| Dangler loaded HydGΔEF c | 0.0941 ± 0.0036 | 0.0640 ± 0.0001 | 0.0529 ± 0.0032 |

| H272A HydGΔEF d | 0.0036 ± 0.0001 | N/A | N/A |

WT traditionally reconstituted HydGΔEF with 7.54 ± 0.48 Fe per protein.

WT traditionally reconstituted HydGEF with 7.38 ± 0.40 Fe per protein.

WT dangler reconstituted HydGΔEF with 8.23 ± 0.43 Fe per protein.

Traditionally reconstituted H272A HydGΔEF with 7.2 ± 0.4 Fe per protein. N/A = not applicable.

Burst phase rate determined by linear fit to data between 0–5 min.

These rates come from biphasic exponential fits to the same data, using all data points from 0 to 120 min.

HydG dangler Fe and free CO formation

In order to probe the relationship between the dangler iron of the C-terminal cluster and the production of free CO, we carried out a series of experiments to correlate spectroscopic and kinetic properties of different preparations of HydG. C.a. HydG samples purified from different expression backgrounds (HydGΔEF or HydGEF) were examined; HydGΔEF is HydG expressed alone in E. coli, while HydGEF is expressed together with the other maturases HydE and HydF and then purified away from them (Table S1†). Both types of HydG were examined for the absence or presence of the dangler Fe (by EPR spectroscopy) and for their free CO formation kinetics (using Mb H64L-based activity assays), after reconstitution under traditional or dangler-loading conditions.

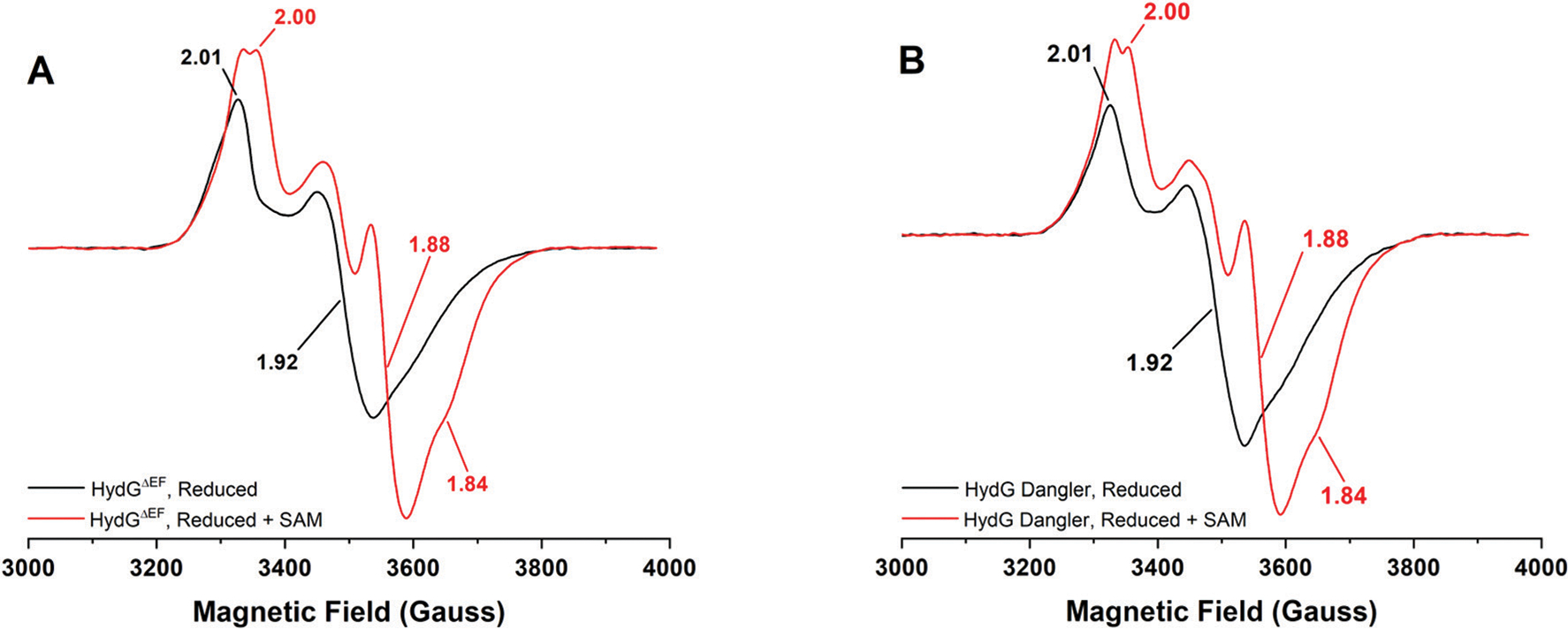

EPR spectroscopy reveals similar S = 1/2 [4Fe−4S]1+ cluster signals in reduced and reduced plus SAM samples in all cases, consistent with our previously published spectroscopic assignments for the N-terminal, N-terminal with SAM bound, and C-terminal [4Fe−4S]1+ cluster states (Fig. 3, S5, and S6†).60 Increases in EPR signal intensity when SAM is added to reduced enzyme samples are consistent with our prior observations wherein SAM coordination to the N-terminal Cx3Cx2C [4Fe−4S] cluster increases its reduction potential.60 Quantitation of S = 1/2 [4Fe−4S]1+ cluster signals in the reduced plus SAM samples gives spin concentrations ranging from 0.70 to 0.95 spins per protein, less than the ∼2 spins per protein one might expect if both [4Fe−4S] clusters are reduced. These numbers can be impacted by non-productive SAM cleavage (which is accompanied by [4Fe−4S]1+ cluster oxidation) in samples prepared for EPR spectroscopic analysis, as well as the propensity of HydG/SAM to undergo visible light-induced reductive cleavage of SAM.74,75 In addition, the [4Fe−4S]1+ spin quantitation can be affected by the presence of the dangler iron, as this S = 2 Fe(II) couples to the C-terminal cluster to give higher spin states.65

Fig. 3.

Low temperature (10.0 K, 1 mW), CW X-band EPR spectra of C.a. HydG. A. WT traditionally reconstituted HydGΔEF (68 μM protein with 7.54 ± 0.48 Fe per protein). B. WT dangler reconstituted HydGΔEF (60 μM protein with 8.23 ± 0.43 Fe per protein). In both panels, black spectra correspond to enzyme treated with 3 mM DT, while red spectra correlate to treatment with 3 mM DT and 2 mM SAM.

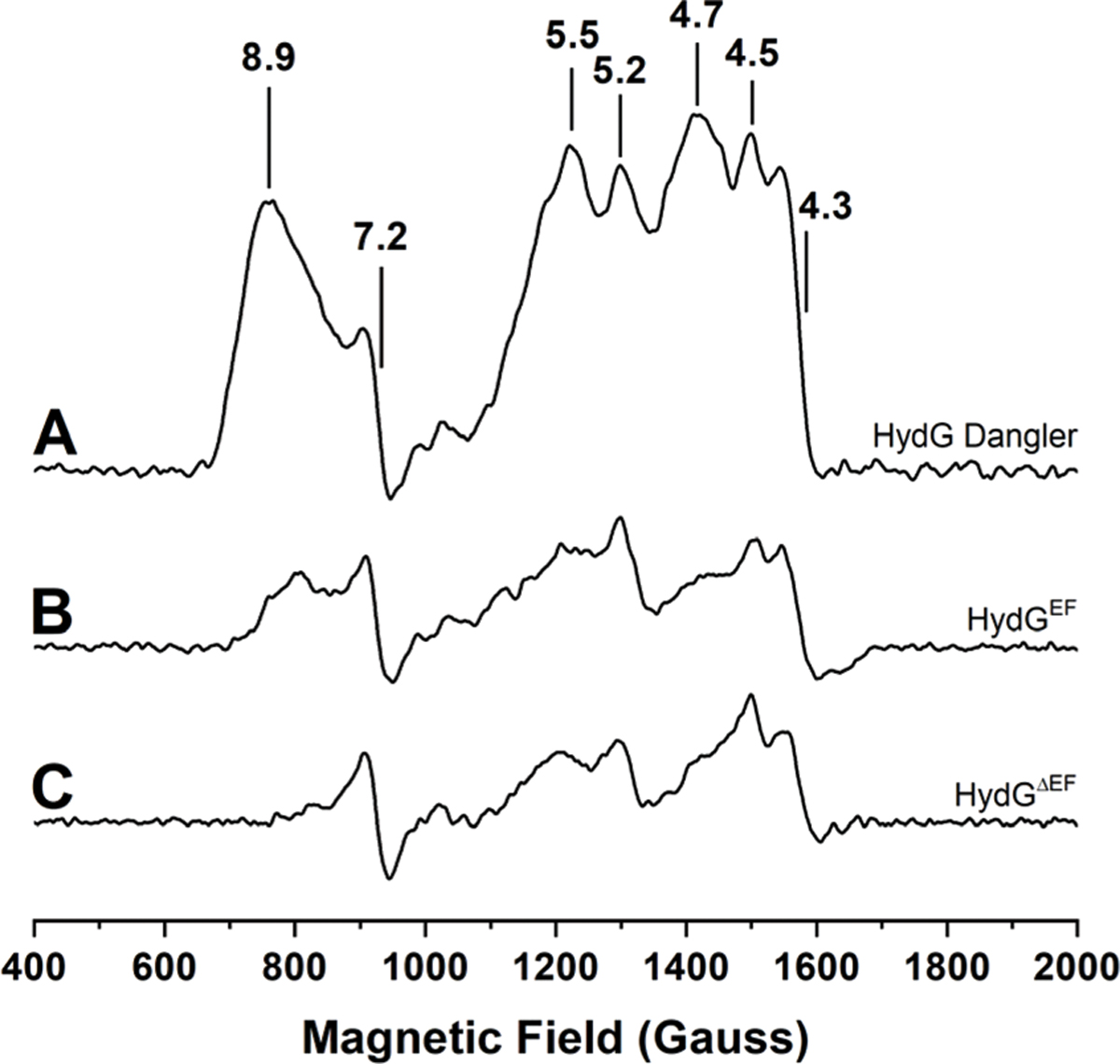

Dangler-loaded C.a. HydGΔEF preparations exhibit a large g = 8.9 feature (Fig. 4 and S7†) consistent with the S = 5/2 [4Fe−4S][(κ3−Cys)Fe] cluster previously reported for S.o. HydG.65 Simulations of the low field region for S.o. HydG demonstrate that S = 5/2 and S = 3/2 spin states both contribute to the low field features, but it is presumed the S = 5/2 signal arises from the site of [Fe(CO)2(CN)(Cys)] synthon formation.65,66,68 We found that even traditionally reconstituted HydG (i.e. which was not specificially treated to load the dangler site) showed features in the g = 4–7 region (Fig. 4) that were reminiscent of some of the low field features reported for the dangler Fe in S. o. HydG.59,65,66 We examined the low field region for proteins that either do not or cannot harbor a dangler Fe moiety, including the radical SAM enzymes pyruvate formate-lyase activating enzyme (PFL-AE) and HydE, as well as the HydG variants HydGH272A and HydGΔCTD; all of these showed features in the g = 4–7 region (Fig. S8†). PFL-AE should not harbor a [4Fe−4S][(κ3−Cys)Fe] “dangler” cluster, because it binds only a single, well-characterized, radical SAM [4Fe−4S] cluster.76–80 For similar reasons, HydE should not exhibit EPR signals arising from a [4Fe−4S][(κ3−Cys)Fe] cluster.50,51,81 HydGH272A lacks the sole protein-derived ligand to the dangler iron, and so would not be expected to bind a [4Fe−4S][(κ3−Cys)Fe] cluster. HydGΔCTD lacks the entire C-terminal domain, and thus has only the radical SAM [4Fe−4S] cluster site, so should not harbor a [4Fe−4S][(κ3−Cys)Fe] cluster. All these proteins, however, show features in the low field region, with g values spanning 4.3–7.2 (Fig. S8†). The source of these signals is not clear, although features in the g = 4.3–9.6 region have been assigned to S = 5/2 linear [3Fe–4S]1+ clusters,82,83 and signals with g-values near 5 have been ascribed to S = 3/2 ground state, [4Fe−4S]1+ clusters.84–87 While we cannot currently assign the origin of the EPR signals in the g = 4–7 region for PFL-AE, HydE, HydGH272A, and HydGΔCTD (Fig. S8†), these seem unlikely to be arising from a [4Fe−4S][(κ3−Cys)Fe] “dangler” cluster.

Fig. 4.

Low temperature, CW X-band EPR spectra of HydG enzyme preparations reduced with 3 mM DT. Spectra recorded at 8.0 K and 5.3 mW microwave power. A. WT dangler-reconstituted HydGΔEF (60 μM protein with 8.23 ± 0.43 Fe per protein). B. WT traditionally reconstituted HydGEF (64 μM protein with 7.38 ± 0.40 Fe per protein). C. WT traditionally reconstituted HydGΔEF (74 μM protein with 7.54 ± 0.48 Fe per protein).

In addition to the g = 4–7 features observed in a wide range of proteins, a distinct low field feature with different temperature dependence is observed only in C.a. HydG, and we attribute this to the [4Fe−4S][(κ3−Cys)Fe] cluster. Temperature dependent EPR spectra of dangler loaded HydG (Fig. 4 and S9†) reveal a maximal intensity for the g ≈ 8.9 signal at 8.0 K (the lowest temperature accessible with our cryostat), with some line broadening in going from 8.0 K to 10 K (Fig. S9†). This line broadening is consistent with the reported temperature dependent line broadening of the S = 5/2, g = 9.5 component of the [4Fe−4S][(κ3−Cys)Fe] cluster in S.o. HydG, with Topt being ≤6.0 K.65 In contrast, the g = 4.3–7.2 features in PFL-AE, HydE, HydGH272A, and HydGΔCTD proteins do not exhibit substantial temperature dependent line broadening between 8.0 and 10.0 K (Fig. S8†). Based on this analysis of the low-field features, we can confidently assign the presence or absence (or degree of loading) of the dangler Fe in various C.a. HydG samples based on the relative intensity of the g ≈ 8.9 feature. Further, the persistence of S = 1/2 C-terminal [4Fe−4S]1+ cluster signals in all WT HydG preparations demonstrates that some speciation exists even in protein that appears to have a high content of dangler Fe in the [4Fe−4S][(κ3−Cys)Fe] cluster (Fig. 3 and 4).

HydG containing either trace or no dangler iron (traditionally reconstituted HydGEF and HydGΔEF, respectively) based on the spectroscopic signatures discussed above, was found to form multiple equivalents of free CO at similar rates (Fig. 5, Table 1). HydGΔEF protein reconstituted specifically for substantial dangler Fe loading (Fig. 4) formed ∼35% more free CO (Fig. 5), although it is not clear whether this effect is exclusively due to greater dangler loading or due to the combined impact of greater overall iron loading at both [4Fe−4S]RS and [4Fe−4S]AUX clusters.

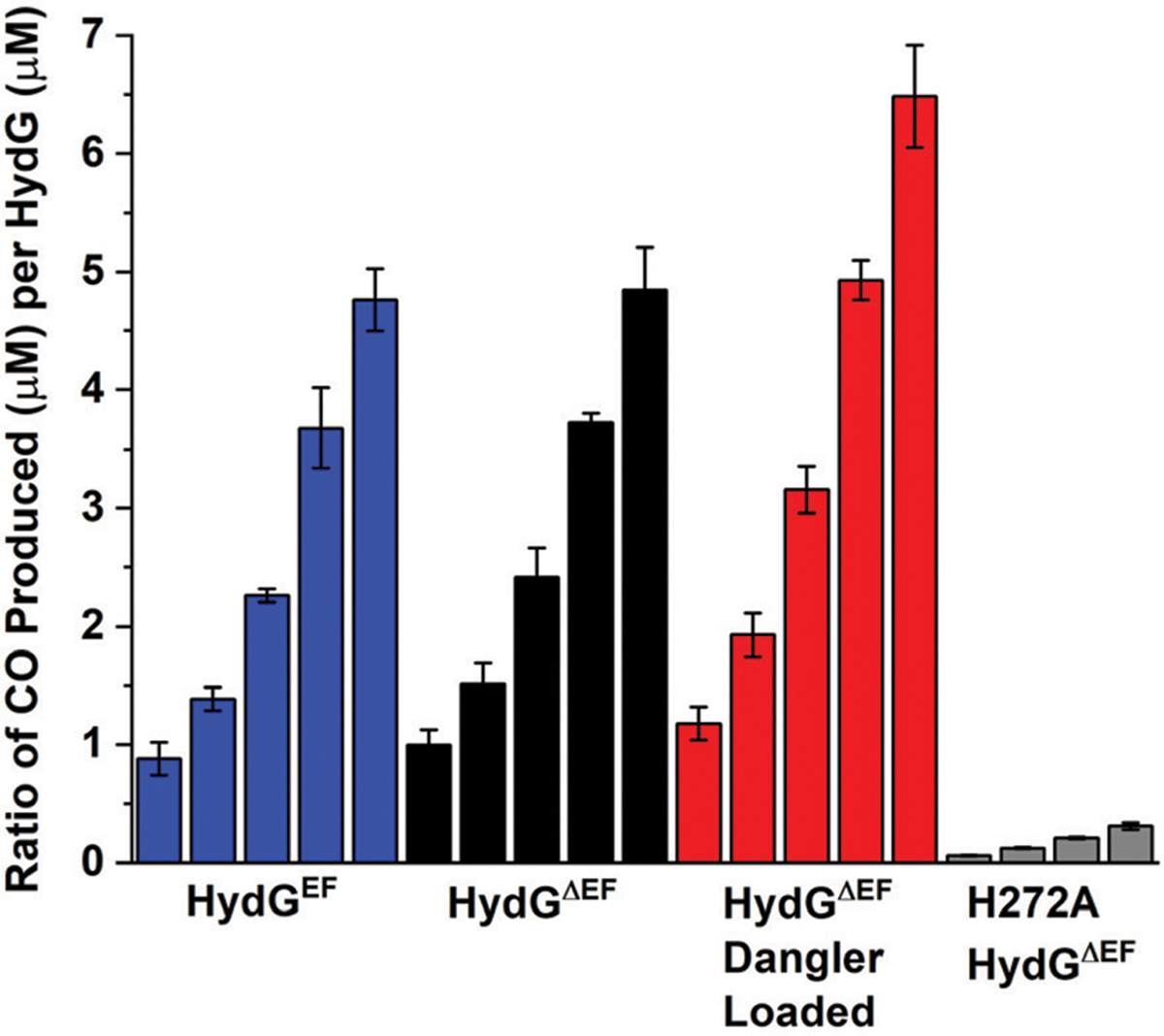

Fig. 5.

CO formed per HydG during kinetics experiments (analysis based on ΔAbs at λ = 425 nm). Each subset of bar graphs depicts the ratio of CO : HydG at 15 min, 30 min, 60 min, 120 min, and 240 min (H272A data set lacks the 240 min time point). The blue subset of bar graphs correspond to experiments performed with WT traditionally reconstituted HydGEF (7.38 ± 0.40 Fe per protein). The black subset of bar graphs correspond to experiments performed with WT traditionally reconstituted HydGΔEF (7.54 ± 0.48 Fe per protein). The red subset of bar graphs correspond to experiments performed with WT dangler reconstituted HydGΔEF (8.23 ± 0.43 Fe per protein). The gray subset of bar graphs correspond to experiments performed with traditionally reconstituted HydGH272A. The color scheme of the data in this figure for particular HydG preparations matches what is depicted in Fig. 2B. Assays conducted in 50 mM Tris, 10 mM KCl, pH 8.1 buffer.

If the dangler Fe serves as a site for CO and CN− binding to form a synthon, we would expect to see only limited free CO in our assays, and/or altered kinetics of free CO production in dangler-loaded samples, due to CO being bound up in a synthon. For example, the free CO detected at longer time points during S.o. HydG turnover was ascribed to degradation of complex B.68 Our results on the C.a. protein, however, are not consistent with this model, as the dangler-loaded protein forms greater amounts of free CO even at early time points (Fig. 5 and Fig. S10†); if the CO and CN− formed during HydG catalysis bound to the dangler Fe to form a synthon, we would expect to see less total free CO, and perhaps a lag in detecting free CO, as the initial CO and CN− produced would not be “free”. These results lead us to draw two conclusions regarding the functional role for the dangler iron of the [4Fe−4S][(κ3−Cys) Fe] cluster. First, the dangler iron is not catalytically essential in the formation of CO by HydG: free CO is formed at appreciable rates in HydG regardless of whether it contains the dangler iron (Table 1, Fig. 5). Second, the dangler iron may play a role in enhancing catalytic CO production, given that CO production is increased in dangler-loaded protein.

In order to address potential artifacts introduced through the use of His-affinity tags with metalloproteins, we examined whether similar results would be observed when using strep-tagged HydG. The WT strep-tagged HydG protein was expressed and purified and subjected to the same spectroscopic and kinetic analyses as described above. The protein showed similar S = 1/2 [4Fe−4S]1+ cluster signals as observed in the His-tagged HydG samples, and low field spectroscopic analysis revealed that some dangler Fe loading occurred during protein overexpression and was maintained through purification and traditional chemical reconstitution steps (Fig. S11†). This protein was assayed for CO formation and found to exhibit similar behavior as the His-tagged protein (Fig. S12†), indicating that the nature of the HydG affinity purification tag has no influence on the observations regarding dangler loading and CO formation.

H272 is essential for efficient CO formation

The dangler Fe of the C-terminal FeS cluster of HydG is bridged to the auxiliary [4Fe−4S] cluster via a non-protein based cysteine to yield the [4Fe−4S][(κ3−Cys)Fe] cluster. The only HydG-derived amino acid that coordinates the dangler Fe is His272 (C.a. numbering).65 The presence of only a single protein ligand led to the hypothesis that the dangler Fe is labile, consistent with its proposed role as the site for formation of the [Fe(CO)2(CN)(Cys)] synthon.66,68 In order to examine the influence of His272 on the ability of HydG to form CO, the H272A HydG variant protein was assayed in the presence of H64L myoglobin. HydGH272A was shown to form small amounts of CO in experimental assays (Fig. 2B, 5 and S13†), forming ≤0.3 equivalents over 2 hours (Fig. 5). The kinetics of CO formation were found to be approximately linear, and the rate of CO production was drastically diminished (relative to WT enzyme) to ≈0.004 min−1 (Table 1). The deleterious impact on CO formation by HydGH272A cannot solely be attributed to the absence of the [4Fe−4S][(κ3−Cys)Fe] cluster, as traditionally reconstituted HydG proteins lack the dangler Fe but still produce appreciable CO (Fig. 2 and 4). Together, these results suggest that the conserved H272 residue plays a key role in DHG breakdown that is independent of the dangler iron.

HydG catalyzes the production of free CN−

It has previously been demonstrated by us and others that HydG forms excess equivalents of CN− during catalysis, with a 1 : 1 stoichiometry relative to p-cresol.56,60,64 However, as described above, our prior methodologies relied on HydG acidification at select time points followed by CN− derivatization and detection.56,60 CN− has alternatively been detected from HydG turnover assays via incubation of the protein at 95 °C in the presence of H2SO4 and KMnO4;64 extracted HCN was then titrated according to the method of Pierik et al.88 Both these published methods likely detect total CN−, not just free CN−. We developed a methodology that would allow us to probe the production of free CN− during catalysis without HydG denaturation using the P115A H-NOX variant protein, which has been demonstrated to be an efficient CN− sensor.89,90 The P115A H-NOX variant binds CN− with a KD value of 290 nM, and exhibits a substantial shift in the Soret band following coordination that provides a visual colorimetric change to samples (Fe(III)-H2O, λmaxSoret = 404 nm; Fe(III)-CN−, λmaxSoret = 421 nm). Dai and Boon demonstrated that P115A H-NOX displays high anion binding selectivity (relative to WT H-NOX),89 thereby making this an attractive protein for the determination of free CN− production during HydG turnover. Fig. S14† demonstrates the visible absorbance changes accompanying addition of KCN to P115A H-NOX.

HydG-MbCO filtrates of the small molecular weight component (≤3000 Daltons) from the endpoint assay experiments represented in Fig. 5 were added to solutions of Fe(III)-H2O P115A H-NOX. As shown in Fig. S15,† this resulted in formation of Fe(III)-CN− P115A H-NOX, with λmaxSoret = 421 nm and λmaxβ = 549 nm. Quantitation of these absorbance features demonstrated that HydG containing trace amounts of dangler species generated multiple equivalents of free CN− (≈2–2.5 equivalents in 4 hours), while dangler-loaded HydG generated 3 equivalents, and HydGH272A generated ≤1 equivalent (Fig. S15†). We observed protein precipitation to occur on the surface of Nanosep centrifugal devices (Fig. S15†) during these assays, and recovery of CN− under conditions of protein precipitation is documented to be challenging.60,88 We therefore suspect that the levels of CN− we detected in CO assay filtrates underestimate the amounts generated during turnover in these experiments. Together, our results demonstrate that as with CO, CN− can be detected in its free state under HydG turnover conditions, and is therefore not fully bound in a synthon.

Fate of the dangler Fe during HydG turnover

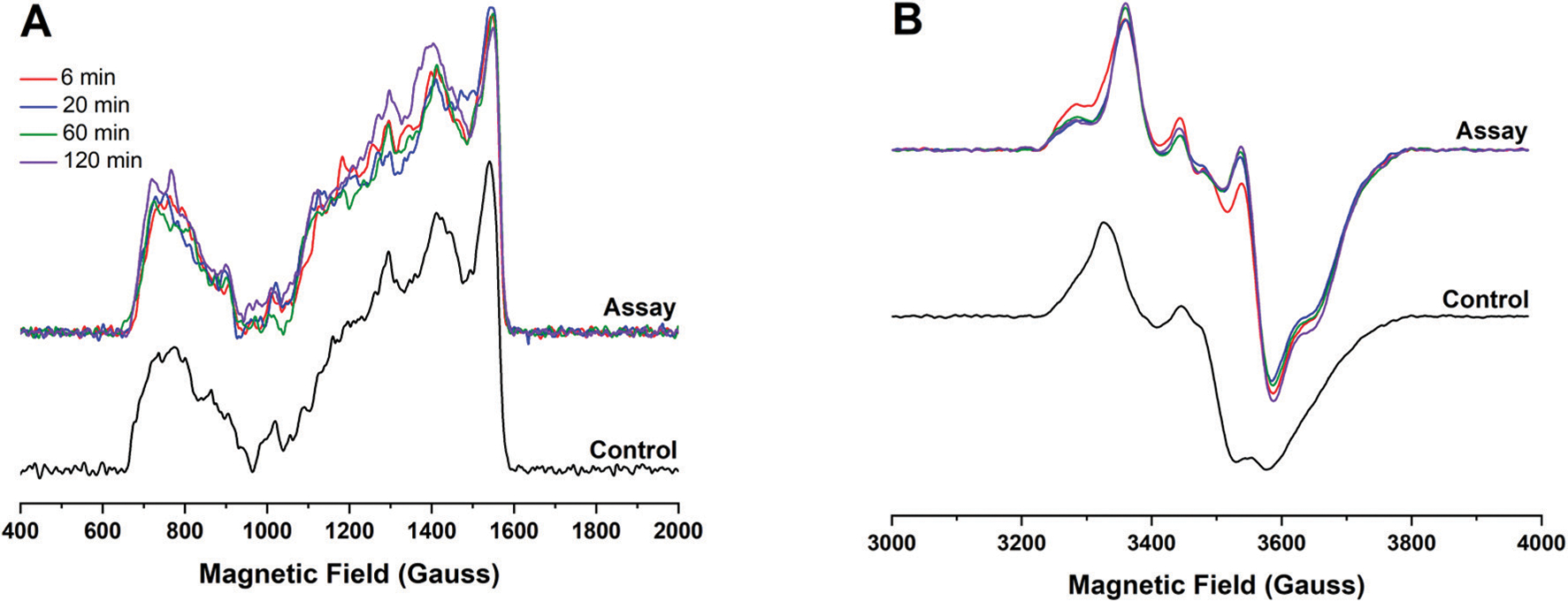

If the dangler Fe serves as the site of synthon formation, then the characteristic [4Fe−4S][(κ3−Cys)Fe] cluster EPR signal would be expected to diminish as the CO and CN− formed during HydG turnover bind to the unique iron; such EPR signal loss could be due to loss of the synthon from HydG, or to the dangler iron spin transition from high-spin Fe(II) to low-spin Fe(II), which is diamagnetic. Alternatively, if the dangler Fe serves as a catalytic site during CO formation, we would expect to see no changes in the dangler Fe EPR signal after HydG turnover. We therefore used EPR spectroscopy to probe the fate of the dangler iron during and after HydG turnover. HydG was mixed with SAM, tyrosine, and H64L deoxy-Mb under reducing conditions in an EPR tube, and reaction was allowed to proceed at ambient temperature for 6, 20, 60, and 120 min. At the indicated intervals, the sample was flash-frozen and EPR spectra were recorded. As can be seen in Fig. 6A (and the broad-field scans in Fig. S16†), the low-field EPR signal characteristic of the dangler Fe species is unchanged at each of these time points, indicating that the dangler Fe remains in its unaltered state. In order to demonstrate that HydG had turned over in these experiments, assay and control EPR samples were thawed after the 120 min time point and UV-vis data were recorded, revealing that a 2.1-fold molar excess of CO is present as the Mb-CO adduct (Fig. S16†). Thus, in these experiments, HydG has turned over at least two times, producing two equivalents of CO and CN−, and yet the dangler Fe remains in its original state. Further, the g ∼ 2 (S = 1/2) EPR signal shows no evidence for formation of the [4Fe−4S]AUX-CN− species previously proposed to be the result of CN− displacement of the synthon from the auxiliary cluster (Fig. 6B).66 Our experimental data instead shows some resolution of an axial signal with a low field shoulder at g ∼ 2.04, which is fully consistent with the N-terminal [4Fe−4S] cluster without SAM coordinated (Fig. S6†).60

Fig. 6.

EPR spectral changes during HydG turnover. A. Low temperature (8.4 K), low magnetic field CW, X-band EPR spectra (average of 6 scans, 5.3 mW microwave power) for dangler loaded HydG (22 μM protein) samples during turnover in the presence of H64L Mb. B. High magnetic field data for the turnover samples (10 K, 1 mW). The colored spectra in both panels correspond to: red, 6 min time point; blue, 20 min time point; green, 60 min time point; purple, 120 min time point.

Dangler Fe is not essential for in vitro activation of HydAΔEFG

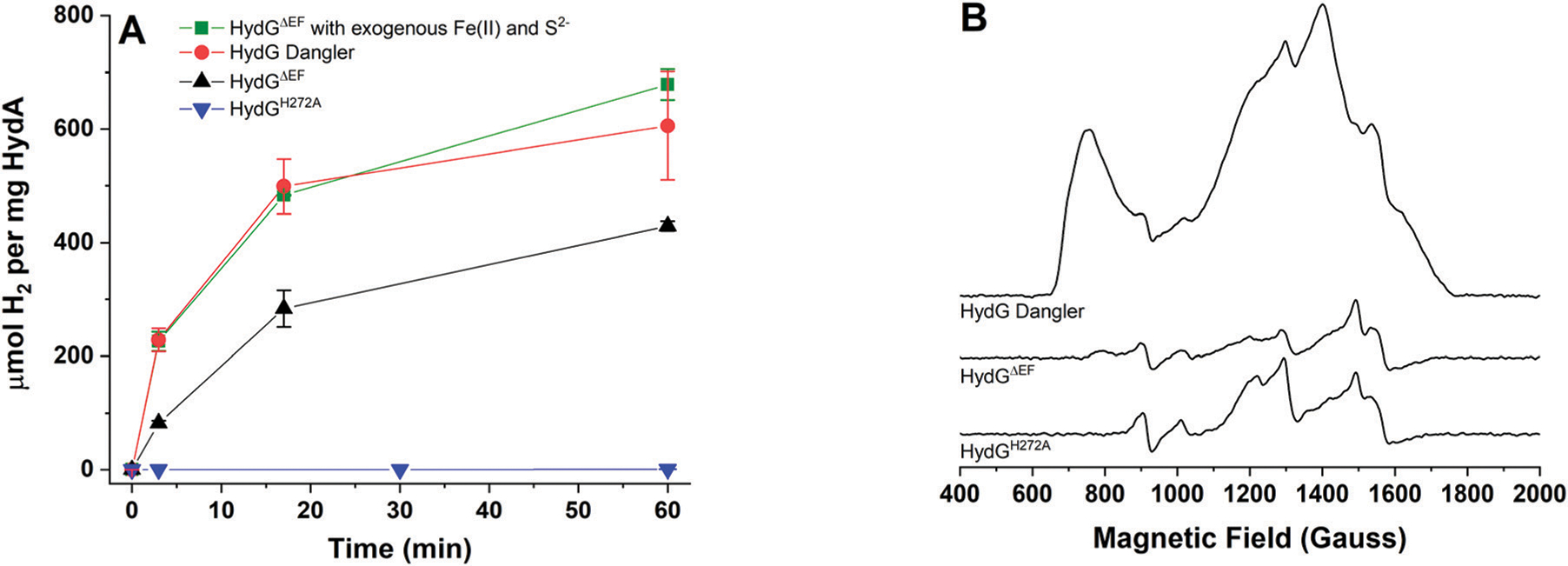

In order to probe the functional importance of the dangler iron and the strictly conserved H272 residue, in vitro hydrogenase activation assays were performed (Fig. 7). In these assays, the H-cluster was matured in vitro using purified HydEΔFG, HydFΔEG, HydGΔEF, and HydAΔEFG proteins supplemented with a defined set of small molecules (PLP, tyrosine, cysteine, SAM, DTT, DT, GTP) in the presence of E. coli lysate. These experiments demonstrate that significant levels of HydAΔEFG activation are achieved when non-dangler loaded HydGΔEF is utilized (Fig. 7), indicating that dangler loading is not essential to hydrogenase maturation. While we cannot completely rule out some inadvertent dangler loading in the complex in vitro activation mixture, any such loading is likely to be minimal given that no exogenous Fe2+ was added to these reactions. The HydA activity can be stimulated when exogenous Fe2+ and S2− are added to the in vitro activation mixture (Fig. 7). In fact, the activation with non-dangler-loaded HydGΔEF in the presence of exogenous Fe2+ and S2− is approximately equivalent to that when dangler-loaded HydGΔEF is used without added Fe2+ and S2− (Fig. 7). The increase in HydA activation with added Fe2+ can thus be attributed largely to additional loading of the dangler Fe in HydG under these conditions, and parallels the increased free CO production observed for dangler-loaded HydG (Fig. 5).

Fig. 7.

In vitro maturation correlated to HydG dangler iron incorporation. A. HydAΔEFG H2 assays following in vitro activation with HydG containing trace amounts of dangler assayed with no added Fe2+ and S2− (black), trace amounts of dangler in the presence of excess Fe2+ and S2− (green), dangler-loaded HydG with no added Fe2+ and S2− (red), or with HydGH272A (blue) B. CW, X-band EPR spectra recorded at 8.0 K and 5.3 mW microwave power for HydG preparations reduced with 3 mM DT. Spectra correlate to the protein samples assayed in panel A: dangler reconstituted HydGΔEF (100 μM, 8.1 ± 0.8 Fe per protein); HydGΔEF (90 μM, 7.7 ± 0.7 Fe per protein); HydGH272A (96 μM, 8.0 ± 0.1 Fe per protein).

HydGH272A affords negligible levels of HydA activation over the course of a typical assay (Fig. 7), although at longer time points, ≈0.5% activity relative to control assays is achieved (data not shown). Addition of exogenous Fe2+ and S2− to in vitro activation assays containing HydGH272A results in a slight increase to ≈0.65% activity at long time periods (data not shown). These data provide support for the idea that H272 plays a critical role in H-cluster maturation, however as with the assay results for free CO production, the functional role of H272 does not appear to be solely to coordinate the dangler iron, because WT HydG lacking the dangler is able to function in activation of HydAΔEFG, while H272A is severely hampered in its ability to do so (Fig. 7). Overall, the in vitro activation results mirror the results based on free CO assays, providing support for the idea that free CO production is in fact on-pathway, and relevant to hydrogenase maturation.

Discussion

The work described here focuses on the role of the “dangler” iron of the auxiliary [4Fe−4S][(κ3−Cys)Fe] cluster of HydG in the catalytic production of CO and CN− ligands during [FeFe]-hydrogenase maturation. Curious differences have been reported for the C.a. vs. S.o. enzymes with regard to CO and CN− production; in the case of C.a. HydG, free CO and CN− are produced during the catalytic decomposition of tyrosine,56,57 whereas S.o. HydG forms an organometallic [Fe(CO)2(CN)(Cys)] synthon rather than the free diatomics.68 The observation that C.a. HydG produced free CO and CN− led to a model for hydrogenase H-cluster maturation involving HydE-catalyzed installation of a DTMA ligand onto a [2Fe–2S] cluster on HydF,44,91,92 followed by delivery of the HydG-produced diatomics in order to make [2Fe]F prior to its delivery to HydA.28,38,39,43,56,57,93 This model for H-cluster maturation was supported by the observation via FTIR of CO and CN− ligands bound to purified HydFEG,39,41,43 and by the evidence for cluster assembly intermediates on HydFE and HydFG.94 Together, these results support a key role for free diatomics during the stepwise assembly of an H-cluster precursor on HydF. However, considerable evidence from studies on S.o. HydG supports an alternative model for [FeFe]-hydrogenase maturation in which HydG synthesizes a [Fe(CO)2(CN)(Cys)] synthon that is either delivered to HydF or serves as a substrate for HydE.65–68,70 In this synthon model, CO and CN− are not produced as free species except when they are released by off-pathway steps.67 The observation that both C.a. and S.o. HydG enzymes are known to support [FeFe]-hydrogenase maturation in in vitro assays is consistent with the expectation that HydG enzymes from different organisms catalyze the same reaction;31,34,58 furthermore, one would expect them to function by the same mechanism, and thus the reported differences between the S.o. and C.a. enzymes are perplexing.

The present work demonstrates that optimizing reaction conditions for C.a. HydG increases the amount of catalytically-generated free CO well beyond the substoichiometric levels initially reported,57 with multiple molar equivalents generated with rate constants in good agreement with the kcat values for CN− formation.56,60 Also reported here is the production of multiple molar equivalents of free CN− during HydG catalysis (Fig. S15†), with no iron-diatomic species observed during or after turnover. Taken together, these results support a model in which HydG catalyzes the synthesis of the free diatomics CO and CN−, which are then delivered to HydFΔEG to assemble [2Fe]F, rather than a [Fe(CO)2(CN)(Cys)] synthon.39 This model is also supported by a recent study showing that exogenous CO stimulates HydA activation when added to HydFE containing an H-cluster assembly intermediate.94

While the “dangler” iron originally characterized in S.o. HydG is also observed here in C.a. HydG by EPR spectroscopy, the presence of the dangler has little impact on the formation of free CO. Lower free CO/CN−, or a lag in production, would be expected if the dangler iron served to bind CO and CN− to form a synthon; instead, enhanced free CO/CN− production is observed in dangler-loaded C.a. HydG. The results of in vitro [FeFe]-hydrogenase maturation parallel these observations: active HydA is produced whether or not the C.a. HydG in the assay is dangler loaded, even in the absence of added Fe(II) that could load the dangler site during the assay. Further, the EPR signal associated with the dangler iron on the [4Fe−4S]aux is unperturbed during HydG catalysis, indicating that the diatomics produced are not forming a synthon at the dangler iron. Taken together, these results support a HydA maturation scheme that does not require synthon formation by C.a. HydG.

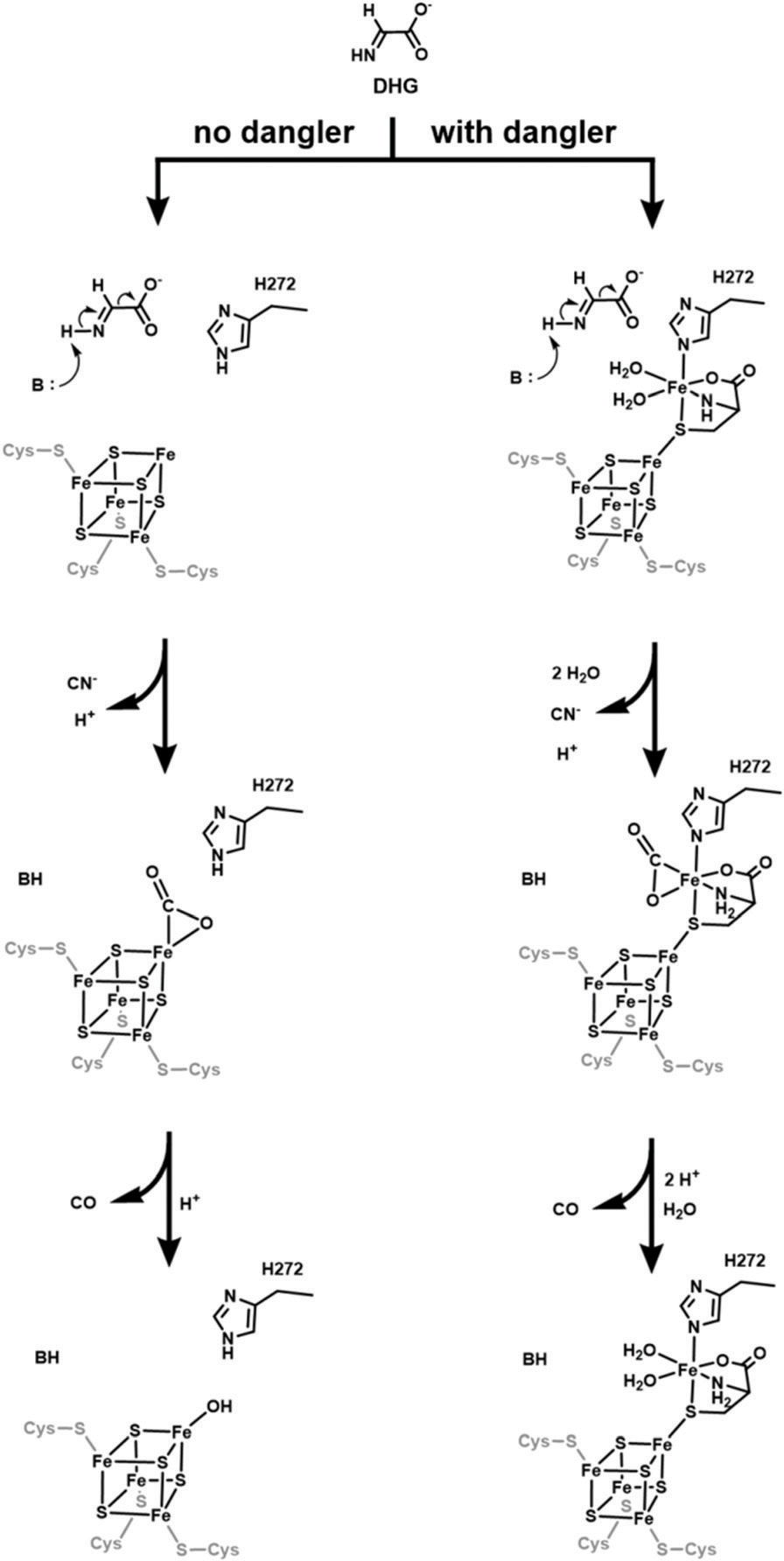

Given that the C.a. HydG studied here exhibits similar catalytic activity (as assessed by free CO production and by hydrogenase activation) regardless of the presence or absence of the dangler iron, we considered possible alternatives to synthon formation as the function for the auxiliary cluster of HydG. One possibility would align with the mechanism proposed by Pagnier et al.,64 in which CN− is formed by DHG breakdown at a site near H272, and then the dangler iron of the [4Fe−4S]AUX mediates decomposition of the formate anion to CO (Scheme 1). Such a role in formate conversion to CO could also be played by the unique iron of the [4Fe−4S]AUX when the dangler is absent (Scheme 1), and thus would be consistent with our results showing that free CO is formed regardless of dangler loading. The observation that HydG variants that completely lack the [4Fe−4S]AUX, for example HydGΔCTD, do not produce any detectable CO, implicate an essential catalytic role for this cluster.60 An essential catalytic role for the dangler iron of the [4Fe−4S]AUX, however, is not supported by the current work.

Scheme 1.

Proposed reactions occurring at or near the C-terminal cluster.

The substantial retardation in CO formation, with more modest reduction in CN− formation, observed for HydGH272A (Fig. 2B, 5 and S15†), parallels the limited degree of HydA activation this variant supports (Fig. 7). While this H272 residue coordinates the dangler iron, the impact of mutation on activity is not due solely to loss of dangler iron binding, because WT enzyme with no dangler iron is nearly fully active both in CO/CN− production and HydA activation. Thus H272 is important in the mechanism regardless of the presence of the dangler iron. This conserved His residue may play a key mechanistic role in DHG breakdown, perhaps during the conversion of formate anion to CO. Such a role would likely be impacted by coordination of H272 to the dangler iron, however, and yet our results reveal little impact of dangler loading on free CO production. Defining the precise role of H272 in HydG catalysis awaits further studies.

The mechanistic details of HydG-catalyzed DHG breakdown to produce CO and CN− remain unclear. The results reported here support the two-site model proposed by Pagnier et al.,64 where a reaction producing CN− occurs at a distinct site near H272, and then the resulting formate anion is converted to CO at the C-terminal cluster, either at the dangler iron or at the unique iron site of [4Fe−4S]AUX, in chemistry reminiscent of that catalyzed by carbon monoxide dehydrogenase at an unusual active site Ni–Fe–S cluster.95 H-cluster biosynthesis has the complexity that HydE, HydF, and HydG may function together in a cooperative manner, and evidence for protein–protein interactions has been reported previously.38,96 How such interactions might impact the details of the chemistry catalyzed by the individual maturases has not been explored, but this is an important next step in elucidating the pathway for [FeFe]-hydrogenase maturation.

The diatomic CO and CN− species produced by HydG are biological toxins; if these do not form an [Fe(CO)2(CN)(Cys)] synthon, then how are these potentially dangerous species tamed during maturation? Protein–protein interactions could be an important factor, by governing how these molecules are chaperoned from HydG to HydF to form the [2Fe]F; protein channels for direct transfer would alleviate the issues of free diatomics needing to be captured by the scaffold protein. HydF has been shown to function in its dimeric state,44,47 and can only interact with a single radical SAM enzyme at a time,96,97 suggesting that the biosynthesis of [2Fe]F occurs in a stepwise manner.39,94 We have generated a molecular docking model of HydG:HydF using ClusPro (Fig. 8).98–101 This model shows the preferred binding of HydG to HydF, wherein the auxiliary cluster domain of HydG, where CO and CN− are formed, is near to the [Fe–S] cluster domain of HydF. This model shows no plausible pathway large enough for a [Fe (CO)2(CN)(Cys)] synthon to translocate out of the bottom of the barrel of HydG, without invoking a significant loop movement. Much smaller free diatomics CO and CN−, however, could diffuse or migrate through a small cationic channel, respectively, to reach HydF. While the structural details of the intimate interactions between the Hyd maturase proteins remain to be revealed, our data suggest that there could be a pathway for free diatomics out of the bottom of the HydG barrel, which would place them in close proximity to the [Fe–S] cluster domain of HydF (Fig. 8), which we have shown can bind a [2Fe–2S] cluster.39,44,91,94

Fig. 8.

Molecular docking model between Thermosipho melanesiensis HydF (5KH0.pdb) and Thermoanaerobacter italicus HydG (4WCX.pdb). (Left) Overall docked structure showing dimeric HydF represented as an electrostatically colored (red, negative charge; blue, positive charge), space filled model. HydG is depicted as a ribbon diagram (α-helix, black; β-strands, red; loop, purple; Fe, orange; and S, yellow). The global contact area between HydG and HydF in the docked structure is 2214 Å2. Surface electronic calculations were carried out using the APBS plugin in PyMOL version 2.2.3 (The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Schrödinger, LLC). (Right) Close up view highlighting the interaction between HydF (green) and HydG (charcoal). The [Fe–S] clusters are depicted in ball-and-stick mode (Fe, orange; S, yellow). The bridging cysteine residue of the HydG auxiliary cluster is shown in stick mode with C, O, N atoms colored cyan, red, and blue, respectively. Residues of interest are denoted accordingly, and these include three lysines and an arginine on HydG, and a histidine and an arginine on HydF, that may be involved in a CN− transfer pathway from HydG to HydF. Distances between certain residues are highlighted in yellow dashed lines; the distance between the dangler Fe in HydG and the [4Fe−4S] cluster of HydF is 23 Å. The docked model was created using the ClusPro software program.98–101

Conclusion

HydG binds an unusual [4Fe−4S][(κ3−Cys)Fe] cluster, as shown previously for S.o. HydG and reported here for C.a. HydG. We show here that C.a. HydG forms multiple equivalents of the diatomic ligands CO and CN− in the free state, with no evidence of organometallic synthon formation. The presence of the fifth “dangler” iron of the [4Fe−4S][(κ3−Cys)Fe] cluster has little impact on either the formation of free CO or on the activation of HydA under in vitro conditions. Further, the activity of the purified HydG in producing free CO correlates directly with the degree of activation of HydA in in vitro maturation. EPR analysis shows that the dangler iron, when present, is unperturbed during turnover, supporting the idea that diatomics form in the free state and are not incorporated as a synthon at the dangler iron site. Together, these results support a model in which the role of HydG is to synthesize free CO and CN− rather than an organometallic synthon. These results are inconsistent with prior studies on the S.o. HydG, where a catalytic activity generating an organometallic synthon has been invoked; delineating the origins of the reported differences between C.a. and S.o. HydG await further studies.

Experimental

All chemicals and other materials used herein were from commercial sources and of the highest purity. Ferric ammonium citrate and NaCl were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO). Triton-X100 and imidazole were obtained from Alfa Aesar (Ward Hill, MA). Tris, HEPES, potassium phosphate, IPTG, PMSF, tryptone, yeast extract, MOPS, dithiothreitol (DTT), glucose, streptomycin, kanamycin, ampicillin, and chloramphenicol were obtained from RPI (Mt. Prospect, IL). Ferrous ammonium sulfate was obtained from J.T. Baker Chemical Company (Phillipsburg, New Jersey). Desthiobiotin was obtained from IBA Lifesciences (Göttingen, Germany). MgCl2, KCl, and glycerol were obtained from EMD (Gibbstown, NJ). Sodium dithionite (DT), sodium sulfide, sodium fumarate, and potassium ferricyanide were obtained from Acros Organics (Fair Lawn, NJ). DNase I, RNase A, and lysozyme (hen egg) were obtained from Roche (Indianapolis, IN). Iron(III) chloride and l-cysteine were obtained from Fisher Scientific (Fair Lawn, NJ).

Preparation of proteins

Wild-type HydGΔEF expression and purification.

HydG was overexpressed and purified as recently described in ref. 74. The purified, buffer-exchanged, and concentrated protein was quantified via Bradford assays using a bovine serum albumin standard solution (Thermo Scientific). Iron in purified protein samples was quantified via a Varian SpectrAA 220 FS flame atomic absorption spectrometer in comparison to a 0.4–2.0 ppm standard curve created from a 1000 ppm iron AA standard solution (Ricca Chemical Company).

Wild-type HydGEF overexpression and purification.

E. coli BL21(DE3) (Stratagene) cells were transformed with plasmids constructed to allow simultaneous expression of the C.a. hydG (CAC1356; engineered to contain BamHI and SalI sites), hydE (CAC1631; engineered to contain NdeI and BglII sites), and hydF (CAC1651; engineered to contain NcoI and BamHI sites) genes. The resulting transformed cells produced the N-terminally, 6x-histidine tagged HydG (pCDFDuet™ vector, MCSI) protein, along with HydE (pETDuet™ vector, MCSII), and HydF (pRSFDuet™ vector, with N-terminal Strep-tag® II at MCSI) proteins. The HydG obtained by affinity purification from these cells that co-express HydE and HydF is denoted HydGEF. A similar cell growth and overexpression protocol as utilized for HydGΔEF was employed for HydGEF,74 with the notable exception of the inclusion of 50 μg mL−1 streptomycin, 30 μg mL−1 kanamycin, and 50 μg mL−1 ampicillin in all LB agar and media preparations. Cell lysis and protein purification steps for HydGEF mirrored those for HydGΔEF.74

WT HydG-strep expression and purification.

The DNA sequence of N-terminally strep-tagged HydG from C.a. was inserted into a pET-14b plasmid (Novagen) between the NcoI and XhoI restriction sites. The recombinant gene was expressed in E. coli BL21-DE3-ΔiscR:kan competent cells. Cells were grown at 37 °C with 200 rpm shaking in phosphate buffered LB media containing kanamycin (30 μg mL−1), ampicillin (100 μg mL−1), and glucose (5 g L−1). At an OD600 of 0.8, cultures were supplemented with ferrous ammonium sulfate (0.3 mM) before induction of protein expression with IPTG (0.5 mM). After a 2.5 hours incubation, cultures were transferred to a 4 °C refrigerator and sparged overnight (14–16 h) with N2(g). The next day, cells were harvested by centrifugation, and resulting cell pellets were flash frozen in liquid N2 and stored at −80 °C until lysis and purification.

Cell lysis and purification steps were performed with minor modifications to the aforementioned protocol. Lysis was performed by sonication (Fisher Scientific, Model 505 sonic dismembrator) at a ratio of 2 mL of buffer per 1 g of cell pellet, using a 100 mM Tris, pH 8, 250 mM KCl, 5% glycerol buffer that was supplemented with lysozyme (180 μg mL−1), PMSF (180 μg mL−1), DNAse (50 μg mL−1), RNAse (50 μg mL−1), 0.5% Triton X-100 (v/v), and MgCl2 (2 mg mL−1). The crude extract was subsequently clarified by ultracentrifugation (150 000g, 1 h) at 4 °C and the supernatant was loaded onto a Strep-Tactin column (IBA Lifesciences, Göttingen, Germany) equilibrated with 100 mM Tris, pH 8, 250 mM KCl, 5% glycerol buffer. After an extensive wash step, the protein was eluted with the same buffer containing 1 mM desthiobiotin and aliquots were flash frozen in liquid N2 and stored at −80 °C until further use.

HydGH272A expression and purification.

The mutant hydG_H272A gene was prepared via a QuikChange Lightning Multi Site-Directed Mutagenesis kit (Agilent Technologies, La Jolla, CA) using the WT C.a. hydG gene encoded on the pCDFDuet™ plasmid as a template; successful incorporation of the mutation site was confirmed by sequencing (Idaho State University Molecular Research Core Facility, Pocatello, ID). The mutant construct encoding the N-terminally, 6x-histidine tagged form of the protein was transformed into E. coli BL21 (DE3) (Stratagene) cells. HydGH272A was prepared using slight modifications to the procedure that was described above. Briefly, single colonies from freshly streaked plates were grown overnight in LB media and were subsequently used to inoculate 9 L LB that was buffered with 50 mM MOPS, pH 7.4, and additionally contained 10 g L−1 tryptone, 5 g L−1 yeast extract, 5 g L−1 NaCl, 5 g L−1 glucose, 500 mg L−1 of ferric ammonium citrate, and 50 μg mL−1 streptomycin. The cultures were grown at 25 °C and 225 rpm shaking until an OD600 = 0.5 was reached, at which point 1.6 g L−1 of sodium fumarate and 242 mg L−1 of l-cysteine were added. Cultures were then sparged with N2(g) for 15 minutes at ambient temperature before 500 μL L−1 of 1 M IPTG was added to each flask. The cultures were then sparged with N2 overnight (16 hours) at ambient temperature. Cells were harvested by centrifugation and the resulting cell pellets were stored at −80 °C until further use.

Cell lysis and protein purification steps for HydGH272A mirrored those for HydGΔEF,74 with the minor exception that 50 mM HEPES, 500 mM KCl, 5% glycerol, pH 7.4 was utilized as the purification buffer. Pure fractions were pooled together and concentrated via centrifugal concentrators (Millipore; Billerica, MA). These concentrated fractions were then dialyzed into 50 mM HEPES, 500 mM KCl, 5% glycerol, pH 7.4 buffer. Concentrated aliquots of HydGH272A were flash frozen in liquid N2 and stored at −80 °C until further use.

HydGΔCTD expression and purification.

A HydG variant protein lacking the last 88 C-terminal residues (termed HydGΔCTD), including the auxiliary [Fe–S] cluster binding Cx2Cx22C motif, was expressed and purified as previously described.60,102 The purified protein was chemically reconstituted (see below) and then buffer exchanged into 50 mM HEPES, 500 mM KCl, pH 7.4, 5% glycerol buffer.

Mutagenesis, expression, and purification of sperm whale H64L myoglobin.

The pVP80K plasmid construct for WT sperm whale Mb was a generous gift from the John S. Olson laboratory (Rice University). Primers for site-directed mutagenesis of H64L were ordered from IDT Technologies and the QuikChange XL Site-Directed Mutagenesis kit (Agilent Technologies, La Jolla, CA) was used with the following minor modifications. In segment 1, 30 PCR cycles were performed, and the Dpn I digestion reaction was only incubated for 5 minutes. PCR products were transformed into E. coli XL10-Gold ultracompetent cells and single colonies from agar plates were used to start small scale (5 mL) overnight growths in LB media (10 g L−1 tryptone, 5 g L−1 yeast extract, 10 g L−1 NaCl, pH 7) in the presence of kanamycin (50 μg mL−1). After 16 hours of aerobic shaking at 250 rpm and 37 °C, cells were harvested via centrifugation, and the QIAprep Spin Miniprep kit (Qiagen) was used to isolate the DNA product. Successful H64L mutagenesis was confirmed via sequence analysis (Genscript).

Plasmid constructs encoding H64L sperm whale Mb were transformed into E. coli BL21-CodonPlus®(DE3)-RIL competent cells (Agilent), and plated on fresh agar plates from which colonies were subsequently plucked and used to inoculate 50 mL overnight cultures in LB media supplemented with kanamycin (50 μg L−1) and chloramphenicol (34 μg L−1). The cultures were allowed to aerobically shake at 250 rpm and 37 °C for approximately 16 hours. The following morning, the overnight cultures were used to inoculate 6 L of phosphate buffered Terrific Broth media (24 g L−1 yeast extract, 12 g L−1 tryptone, 4 mL L−1 glycerol, pH 7), in the presence of kanamycin (50 μg L−1) and chloramphenicol (34 μg L−1). These cultures were then grown aerobically at 37 °C with 230 rpm shaking. When OD600 values were approximately 0.8, the cultures were induced with IPTG to a final concentration of 105 μM, and the cultures continued to grow at 28 °C and 200 rpm for an additional 16 hours. Cells were harvested by centrifugation, and the resulting cell pellets were flash frozen in liquid N2 and stored at −80 °C until further use.

Cell pellets were thawed aerobically and resuspended in a 3 : 1 ratio of lysis buffer to cell pellet at 4 °C; the lysis buffer comprised 50 mM Tris pH 8, 16 mg dithiothreitol, 35 mg PMSF, 0.2 mg DNAse I, 0.2 mg RNAse A, and 20 mg lysozyme per 200 mL buffer. The solution was allowed to stir for an hour and was then sonicated on ice for a total pulse time of 5 minutes (15 seconds bursts, 60% amplitude) using a digital sonifier (Branson Ultrasonics Corporation). The crude lysate was then centrifuged for 30 min at 4 °C and 18 000 rpm. Solid ammonium sulfate was slowly added to 50% (313.5 g L−1) to the supernatant on ice with stirring, and allowed to incubate for 30 minutes, after which the solution was re-centrifuged. A second ammonium sulfate precipitation was then performed to 95% (335.5 g L−1). Following centrifugation, the pellet containing the Mb protein was re-suspended in chilled 20 mM Tris, pH 8 buffer, and loaded onto a Superdex 75 gel filtration column (GE Life Sciences) housed within an anaerobic Coy chamber (Grass Lake, MI) at room temperature. The purified protein was eluted using 20 mM Tris, pH 8 buffer as the mobile phase. Fractions containing purified protein were collected and pooled. Protein and iron quantitation were performed as described above.

To prepare Mb for spectroscopic CO binding studies, the protein was first oxidized using potassium ferricyanide. Solid K3[FeCN6] was dissolved in 50 mM Tris, pH 8 buffer and added to the Mb solution to yield a final concentration that was 100-fold that of the purified protein. This solution was allowed to stir for 1 hour, after which the Mb solution was loaded onto a PD10 desalting column (GE Life Sciences), and eluted with 50 mM Tris, pH 8 buffer. Column fractions containing dark red protein were subsequently pooled.

The Mb was next subjected to reduction under anaerobic conditions in a Coy chamber via addition of sodium dithionite (DT) to 15-fold excess over protein concentration. This solution was stirred for 1 hour, at which time the UV-vis absorbance spectrum was recorded and the presence of deoxy-Mb was confirmed via the Soret band absorbance maxima (λmax = 432 nm). The reduced protein was then concentrated using an Amicon 10 kDa MWCO spin concentrator (Millipore). Following the concentration step, the protein was then dialyzed against 20 mM Tris, pH 8 buffer under anaerobic conditions. Following dialysis, the Mb protein was aliquotted, flash frozen in liquid N2, and stored at −80 °C until future use.

Expression and purification of heme-nitric oxide and/or oxygen binding domain (HNOX).

The DNA for the 6xHis-tagged P115A variant gene (pET-20b vector, Novagen) of the Thermoanaerobacter tengcongensis HNOX (T.t. H-NOX) binding domain was kindly provided from the Elizabeth Boon laboratory (Stony Brook University). Prior literature reports guided the overexpression and purification of P115A T.t. h-nox.89,90,103 DNA was transformed into E. coli Tuner™(DE3)pLysS cells (Novagen). Single colonies from fresh transformations were plucked from agar plates (ampicillin and chloramphenicol resistance) and used to test for H-NOX induction for the creation of glycerol stocks. Fresh chloramphenicol (34 μg L−1) and ampicillin (50 μg L−1) resistant agar plates were then streaked with a P115A T.t. H-NOX glycerol stock; a single colony was subsequently plucked and used to inoculate a 50 mL overnight culture in LB media supplemented with chloramphenicol (34 μg L−1) and ampicillin (50 μg L−1). The culture was grown aerobically at 230 rpm and 37 °C for approximately 15 hours. The following morning, 3 L (2 × 1.5 L flasks) of phosphate buffered Terrific Broth media (24 g L−1 yeast extract, 12 g L−1 tryptone, 4 mL L−1 glycerol, pH 7) supplemented with chloramphenicol (34 μg L−1) and ampicillin (50 μg L−1) was inoculated with 5 mLs per flask from the overnight culture. These cultures were grown aerobically at 37 °C with 230 rpm shaking until an OD600 of 0.6 was achieved. The flasks were then cooled to 25 °C with 230 rpm shaking for 30 min. The cultures were then induced with IPTG (10 μM final concentration), and additionally supplemented with 5-aminolevulinic acid (1 mM final). The cultures continued to shake at 230 rpm at 25 °C for 16 hours. Cells were harvested by centrifugation, and the resulting cell pellets were flash frozen in liquid N2 and stored at −80 °C until further use.

Cell pellets were thawed aerobically at 37 °C and resuspended in a 4 : 1 ratio of lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole supplemented with 1 mM PMSF and 5 mM DTT). The solution was then sonicated on ice for a total pulse time of 5 minutes (15 seconds bursts, 60% amplitude) using a digital sonifier (Branson Ultrasonics Corporation). The crude lysate was then centrifuged for 30 min at 4 °C and 18 000 rpm. The supernatant was then incubated in a 75 °C water bath for 40 minutes, recentrifuged, and then filtered using 0.45 μm membrane filters (Advantec). The clarified supernatant was then passed over a 5 mL HisTrap™ Ni2+- affinity column (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) using an ÄKTA Basic 100 FPLC (GE Healthcare). Purified H-NOX was eluted from the column using an imidazole gradient with increasing amounts of 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 500 mM imidazole. Protein purity was found to be ≥95% via SDS-PAGE.

To prepare the Fe(III)-H2O form of P115A H-NOX for spectroscopic CN− binding studies,89,90 the protein was oxidized with potassium ferricyanide. Solid K3[FeCN6] was dissolved in 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.4 buffer and added to the purified H-NOX protein in ≈100-fold excess. Solutions were incubated for 1–2 hours, and were then immediately run over a PD10 desalting column (GE Life Sciences) equilibrated in 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.4 buffer. Eluted H-NOX was collected in two main pools and analysed via UV-Vis spectroscopy. Protein and iron quantitation were performed as described above. The H-NOX protein utilized herein for HydG generated CN− spectroscopic binding studies contained 1.1 ± 0.13 Fe atoms per protein. To demonstrate CN− binding using the Fe(III)-H2O (ε405 nm = 108 mM−1 cm−1) form of P115A H-NOX, protein (17 μM heme) was incubated with 32 μM KCN in 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.4 buffer. The sample was incubated at 60 °C for 4 h and the spectral changes over time were monitored via UV-Vis. Fe(III)-H2O P115A H-NOX (λmaxSoret = 404 nm; λmaxβ,α = 528 nm, 614 nm) was observed to isosbestically convert to the Fe(III)-CN− complex (λmaxSoret = 421 nm; λmaxβ = 549 nm), consistent with prior literature reports (Fig. S14†).89,90

PFL-AE expression and purification.

PFL-AE was purified as described elsewhere.104,105 Purified protein for EPR spectroscopic analysis was buffer exchanged into 50 mM Tris, 100 mM KCl, pH 7.5 buffer.

HydE expression and purification.

HydE from C.a. was over-expressed, purified, and chemically reconstituted with FeCl3 and Na2S as previously described.50 The purified protein was buffer exchanged into 50 mM Tris, 250 mM KCl, 5% glycerol, pH 8.0 buffer for spectroscopic characterization.

Chemical reconstitution of HydG.

HydG typically purifies with substoichiometric amounts of Fe loading. The WT HydGΔEF enzyme utilized herein contained 3.94 ± 0.28 Fe per protein in its as-purified state, whereas WT HydGEF harbored 2.88 ± 0.24 Fe per protein, strep-tagged HydG contained 3.50 ± 0.20 Fe per protein, HydGH272A contained 2.73 ± 0.17 Fe per protein, and HydGΔCTD had 1.53 ± 0.06 Fe per protein. These samples were subsequently subjected to chemical reconstitution in order to improve [4Fe−4S] cluster loading. Reconstitutions of WT, HydGH272A, and HydGΔCTD preparations were carried out as recently described.74 Briefly, HydG enzyme (≤150 μM) was incubated with a 6-fold excess of FeCl3 and Na2S in the presence of 5 mM DTT in either 50 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 0.25 M KCl, 5% glycerol buffer (WT enzyme) or 50 mM HEPES, 0.5 M KCl, 5% glycerol, pH 7.4 (HydGH272A and HydGΔCTD enzymes, respectively). Strep-tagged HydG was reconstituted by adding a 12-fold excess of Fe(NH4)2(SO4)2 and Na2S at room temperature in the presence of 5 mM DTT, and a 6-fold excess of SAM. Reconstitution mixtures were incubated for 2.5–3.5 h with gentle stirring in an anaerobic Coy chamber, and were then centrifuged to pellet bulk FeS precipitates. The resulting supernatant solutions were then passed over a Sephadex G-25 column to remove adventitiously bound iron, sulfide, and DTT. Gel filtered HydG samples were then concentrated using Amicon Ultra 10 kDa molecular weight cutoff filter devices (Millipore), and aliquots were then flash frozen in liquid N2 and stored at −80 °C until kinetic and spectroscopic characterization. Bradford analysis and iron quantitation were performed as described above. Following reconstitution, WT HydGΔEF harbored 7.54 ± 0.48 Fe atoms per protein, WT HydGEF contained 7.38 ± 0.40 Fe per protein, strep-tagged HydG had 9.20 ± 0.20 Fe per protein, HydGH272A had 7.2 ± 0.4 Fe per protein, and HydGΔCTD had 2.40 ± 0.17 Fe atoms per protein.

Preparation of dangler loaded HydG.

Traditionally reconstituted HydGΔEF (7.54 ± 0.48 Fe per protein) was loaded with the dangler iron according to our recently published methodology.74 Dangler loaded HydGΔEF contained 8.23 ± 0.43 Fe per protein.

Enzymatic assays

HydG-based turnover assays in the presence of H64L myoglobin.

Assay components for HydG-catalyzed CO formation were assembled in an MBraun anaerobic chamber (O2 ≤1 ppm) and were carried out with modifications to our previously published protocol.57,75 Reconstituted HydG samples were assayed for CO production using H64L deoxymyoglobin (deoxyMb) as a reporter. Assays contained HydG protein in 50 mM Tris, 10 mM KCl, pH 8.1 buffer and 8 mM DT, and were conducted at 37 °C. Buffer, HydG enzyme, and DT were sequentially added together and transferred to a 1 mm path-length, anaerobic cuvette (Spectrocell Inc., Oreland, PA, USA). UV-vis absorbance spectra (250–800 nm) were then recorded using a benchtop Cary 60 spectrophotometer (Varian) with a 1.0 nm data interval. Samples were then transferred back into the MBraun chamber wherein H64L Mb (typical heme concentrations near 80 μM) and l-tyrosine (600 μM–1 mM final concentration) additions were made. Samples were then removed from the MBraun and final UV-Vis spectra were recorded. Samples were incubated at 37 °C in the spectrophotometer for 6–8 minutes prior to assay initiation via addition of SAM. Aliquots of SAM were loaded into a Hamilton gas tight syringe inside the MBraun chamber; when it was time to initiate data collection (see below), the needle of the syringe was pushed through the Teflon membrane of the anaerobic cuvette and SAM was directly injected into the sample. Solutions were then quickly mixed via inversion of the cuvette, which typically took between 30–40 seconds before spectral acquisition began.

The formation of CO and complexation by deoxyMb is evidenced by the shift in the Soret band (432 nm to 425 nm) and by the shift and splitting of the ≈565 nm band, which together give rise to a visible spectrum characteristic of MbCO. Accordingly, H64L MbCO formation was monitored via single-wavelength kinetics experiments using the Cary 60 spectrophotometer and monitoring changes at 425 nm. Experiments were typically run for 4 hours, at which time a final UV-Vis scan from 250–800 nm was recorded. UV-vis difference spectra were constructed from scans collected before and after addition of H64L deoxyMb, tyrosine, and SAM (at 2 h and 4 h time points), respectively; these difference spectra were used to correct for sample dilution and quantify the H64L carboxy-Mb that was formed during the experiment. The ΔAu(425 nm) and Δε(425 nm) were used to calculate H64L MbCO concentration values at each time point during single-wavelength kinetics experiments. Turnover (kcat) values were calculated either from linear fits to the initial “burst” phase (≤5 min), or from biphasic exponential association curves involving all time points using the software program OriginPro (either 8.5 or 2018b versions, OriginLab Corp. Northampton, MA, USA).

Spectroscopic detection of free CN− following HydG-based CO turnover assays.

Spectroscopic detection of CN− was achieved via analysis of CO production assay endpoints conducted in the presence of H64L myoglobin (as described above). Following final spectral acquisition of MbCO formation, samples were removed from the anaerobic cuvettes (400–600 μL), placed on ice, and exposed to O2. Following a 10 minutes incubation period, samples were centrifuged at 4 °C under aerobic conditions using Nanosep 3000 MWCO Omega™ (Pall) spin filters. The small molecular weight flow through component was then added to a solution of Fe(III)-H2O P115A H-NOX and was incubated at 60 °C for 4 h; a control sample of Fe(III)-H2O P115A H-NOX supplemented with reaction buffer was treated alongside the sample vial. Formation and quantitation of Fe(III)-CN− was then determined by UV-Vis spectroscopy (Fig. S15†).

In vitro activation assays.

The expression, isolation, and reconstitution of C.a. maturases followed previously published protocols: HydEΔFG as in ref. 50, HydGΔEF (Materials and methods section), and HydFΔEG as in ref. 91. The expression of His6-tagged HydAΔEFG from Chlamydomonas reinhardtii (C.r.) was accomplished by cloning the hydA gene into pET Duet, and then transforming the plasmid into BL21-DE3-ΔiscR:kan competent cells. Single colonies from these transformations were grown in phosphate buffered LB overnight, prior to being used to inoculate large cultures of the same media containing 5 mg mL−1 glucose and 100 μg mL−1 of ampicillin. The cells were grown to an OD600 ≈ 0.5, at which point IPTG (1 mM final concentration) was added to induce protein expression. This was followed by addition of 0.5 mM (NH4)2Fe(SO4)2·6H2O and 0.1 mM l-cysteine and incubated for an additional 16 h at 25 °C while shaking. The cells were harvested by centrifugation, flash frozen and stored in −80 °C until usage.

Purification and reconstitution of C.r. HydA was carried out in an anaerobic Coy chamber maintained in a walk-in cold room (4 °C), following a procedure described in McGlynn et al.38 Since the purified protein had low iron content, HydAΔEFG was chemically reconstituted as described above. Concentration and iron quantitation for maturase proteins were accomplished through Bradford assay and flame atomic absorption spectroscopy, as described above. E. coli lysate for use in the in vitro activation assays was prepared from a glycerol stock of BL21(DE3)ΔiscR:kan, which was used to inoculate 50 mL starter cultures in LB media that contained 30 μg mL−1 kanamycin. Large scale (3 L) growths were inoculated with 7.5 mL of the overnight culture and were subsequently incubated at 37 °C for 3 hours or until OD600 ≈ 0.5 was reached. At this point, the flasks were cooled on ice, and then centrifuged. The wet cell pellet was then resuspended in 100 mM HEPES, pH 8.2, 50 mM KCl buffer that was supplemented with PMSF and Triton-X-100, as described above. The mixture was then sonicated (5 min total pulse time at 60% amplitude) using a model FB505 sonic dismembrator (500 W, Fisher Scientific), followed by ultracentrifugation to obtain a clarified lysate, which was aliquotted and flash frozen in liquid N2.

In vitro activation of C.r. HydAΔEFG consists first maturing the hydrogenase via incubation with purified HydEΔFG, HydFΔEG, and HydGΔEF (dangler loaded, non-dangler loaded, and HydGH272A proteins, respectively), along with defined small molecules in the presence of E. coli lysate (the inclusion of the clarified cell lysate is required, presumably due to the presence of the unidentified small molecule substrate(s) for HydE). Following incubation, the activation of holo-HydA is then achieved by supplementing the mixture with methyl viologen and dithionite to facilitate proton reduction.34,38,106 In vitro maturation and activation experiments of holo-HydA were carried out at ambient temperature, in an anaerobic MBraun chamber (O2 ≤1 ppm). A standard reaction consisted of 50% (by volume) E. coli lysate, 25 μM HydGΔEF (from different protein preparations that contained iron numbers ranging from 8–8.6 per protein), 5 μM HydFΔEG (7.0 Fe per protein), 5 μM HydEΔFG (7.8 Fe per protein), 4 μM HydAΔEFG (4 Fe per protein), 1 mM PLP, 2 mM tyrosine, 2 mM cysteine, 2 mM SAM, 1 mM DTT, 2 mM DT, and 20 mM GTP. Positive control assays additionally contained 1.6 mM Fe2+ and 0.8 mM S2−. Assay components were incubated together for 12 hours in a 100 mM HEPES, pH 8.2, 50 mM KCl buffer. To prepare the hydrogenase activity assay, 200 μL of the reaction mixture was diluted to 2 mL (final volume) using 50 mM Tris, pH 6.9, 10 mM KCl buffer; DT and methyl viologen were then added to the mixture to final concentrations of 20 mM and 10 mM, respectively. At defined time points, aliquots of headspace gas were removed from the vial with a Hamilton gas tight syringe; H2 production was quantified using a SHIMADZU GC-2014 with a TCD detector, with N2 as a carrier gas.38

Electron paramagnetic resonance sample preparation and spectral acquisition

EPR samples were prepared in an MBraun box (O2 ≤1 ppm) using buffers that were freshly degassed on a Schlenk line. Reduced protein samples were loaded into EPR tubes (Wilmad LabGlass, 4 mm OD, NJ, USA), capped with rubber septa, and then immediately transferred from the chamber and flash frozen in liquid N2. Samples were stored in a liquid N2 dewar until spectral acquisition occurred.

WT HydG, HydGH272A, and HydE samples were prepared by reducing protein with freshly prepared DT (3 mM final). For samples wherein SAM was added to monitor perturbations to S = 1/2 cluster signals, protein would first be reduced with DT (3 mM final), followed by the immediate addition of SAM (2 mM final). After a short incubation period (5–8 minutes), reduced and reduced plus SAM EPR samples were simultaneously flash frozen in liquid N2. The SAM stocks utilized herein were enzymatically synthesized from l-methionine and ATP precursor molecules via SAM synthetase as described elsewhere.105,107,108 Purified and lyophilized SAM stocks were resuspended in 50 mM Tris buffers and neutralized to final pH values that ranged between 7.0–7.4. Reduced HydGΔCTD and PFL-AE samples were prepared by supplementing protein with 5 mM DTT and 50–100 μM 5-deazariboflavin in 50 mM Tris, pH 7.4 buffer. Samples were placed in an ice water bath and illuminated for 1 hour using a 300 watt Xe lamp; the ice water bath was constantly maintained during the illumination period. Illumination of proteins in the presence of Tris (the source of reducing equivalents) and 5-deazariboflavin produces a catalytic source of low potential electrons, in a process referred to as photoreduction.109 Immediately following the 1 hour photoreduction period, the EPR samples were flash frozen and stored in a liquid N2 dewar until spectral acquisition occurred. It is important to note that our prior work with WT and variant HydG proteins demonstrated no substantial EPR spectral differences between samples that were prepared either by DT reduction or 5-deazariboflavin mediated photoreduction.60

Low temperature continuous wave (CW), X-band (9.38 GHz) EPR spectra were collected using a Bruker EMX spectrometer fitted with a ColdEdge (Sumitomo Cryogenics) 10 K waveguide in-cavity cryogen free system, with Oxford Mercury iTC controller unit and helium Stinger recirculating unit (Sumitomo Cryogenics, ColdEdge Technologies, Allentown, PA). Helium gas flow was maintained at 100 psi. Typical spectral parameters were: 5.3 mW microwave power (low field scans), 1.0 mW microwave power (high field scans), 100 kHz modulation frequency, 10 G modulation amplitude, and spectra were averaged over 6 scans. The software program OriginPro (2018b, OriginLab Corp. Northampton, MA, USA) was used to baseline correct and plot all experimental spectra. Spin integration of [4Fe−4S]+ cluster EPR spectra was accomplished in OriginPro 2018b via the double-integration of experimental data and comparison to a 100 μM copper(II) triethanolamine spin standard. The methodology of Aasa and Vänngård was used to calculate the proportionality constant for proper normalization of [4Fe−4S]+ cluster EPR spectra.110

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The work described herein was supported by the US Department of Energy, Office of Basic Energy Sciences grant DE-SC0005404 (to J. B. B. and E. M. S.). The preparation and characterization of PFL-AE (Fig. S8†) was supported by the U.S. National Institutes of Health (GM 54608 and GM 131889 to J. B. B.). Contributions of J. W. P were supported by the US National Institutes of Health (GM138592).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available. See DOI: 10.1039/d1dt01359a

Notes and references

- 1.Lubitz W, Ogata H, Rudiger O and Reijerse E, Chem. Rev, 2014, 114, 4081–4148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peters JW, Schut GJ, Boyd ES, Mulder DW, Shepard EM, Broderick JB, King PW and Adams MWW, Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Mol. Cell Res, 2015, 1853, 1350–1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dubini A and Ghirardi ML, Photosynth. Res, 2015, 123, 241–253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khan MA, Ngo HH, Guo WS, Liu YW, Zhang XB, Guo JB, Chang SW, Nguyen DD and Wang J, Renewable Energy, 2018, 129, 754–768. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ghirardi ML, Photosynth. Res, 2015, 125, 383–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jones CS and Mayfieldt SP, Curr. Opin. Biotechnol, 2012, 23, 346–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ghirardi ML, Posewitz MC, Maness P-C, Dubini A, Yu J and Seibert M, Annu. Rev. Plant Biol, 2007, 58, 71–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McKinlay JB and Harwood CS, Curr. Opin. Biotechnol, 2010, 21, 244–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Swanson KD, Ratzloff MW, Mulder DW, Artz JH, Ghose S, Hoffman A, White S, Zadvornyy OA, Broderick JB, Bothner B, King PW and Peters JW, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2015, 137, 1809–1816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Orain C, Saujet L, Gauquelin C, Soucaille P, Meynial-Salles I, Baffert C, Fourmond V, Bottin H and Leger C, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2015, 137, 12580–12587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kubas A, Orain C, De Sancho D, Saujet L, Sensi M, Gauquelin C, Meynial-Salles I, Soucaille P, Bottin H, Baffert C, Fourmond V, Best RB, Blumberger J and Leger C, Nat. Chem., 2017, 9, 88–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lambertz C, Leidel N, Havelius KGV, Noth J, Chernev P, Winkler M, Happe T and Haumann M, J. Biol. Chem, 2011, 286, 40614–40623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stripp ST, Goldet G, Brandmayr C, Sanganas O, Vincent KA, Haumann M, Armstrong FA and Happe T, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A, 2009, 106, 17331–17336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Birrell JA, Rudiger O, Reijerse EJ and Lubitz W, Joule, 2017, 1, 61–76. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Happe T and Hemschemeier A, Trends Biotechnol, 2014, 32, 170–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Artero V, Berggren G, Atta M, Caserta G, Roy S, Pecqueur L and Fontecave M, Acc. Chem. Res, 2015, 48, 2380–2387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Esmieu C, Raleiras P and Berggren G, Sustainable Energy Fuels, 2018, 2, 724–750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morra S, Valetti F and Gilardi G, Rend. Lincei-Sci. Fis, 2017, 28, 183–194. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reeve HA, Ash PA, Park H, Huang AL, Posidias M, Tomlinson C, Lenz O and Vincent KA, Biochem. J, 2017, 474, 215–230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Esselborn J, Lambertz C, Adamska-Venkatesh A, Simmons T, Berggren G, Noth J, Siebel J, Hemschemeier A, Artero V, Reijerse E, Fontecave M, Lubitz W and Happe T, Nat. Chem. Biol, 2013, 9, 607–609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berggren G, Adamska A, Lambertz C, Simmons TR, Esselborn J, Atta M, Gambarelli S, Mouesca JM, Reijerse E, Lubitz W, Happe T, Artero V and Fontecave M, Nature, 2013, 499, 66–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]