Abstract

Objectives

This study aimed to determine extubation failure (EF) rate among intubated preterm infants (<37 weeks gestational age [GA]) admitted to a tertiary care neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) in Oman and identify the risk factors associated with EF.

Methods

This retrospective study included all intubated preterm infants (<37 weeks GA) admitted to the NICU at Sultan Qaboos University Hospital (SQUH) from January 2013 to December 2017. EF was defined as reintubation within seven days of planned extubation. Demographics, ventilation parameters, blood gas values and other possible risk factors of EF were collected. Statistical analysis included comparisons between EF and extubation success (ES) groups and a binary logistic regression analysis.

Results

A total of 190 preterm infants were intubated during the study period with 140 eligible for analysis. A total of 106 infants (75.7%) were successfully extubated while 34 (24.3%) failed extubation. GA <28 weeks (P = 0.029), lower 1-minute Apgar score (P = 0.023) and patent ductus arteriosus diagnosis (P = 0.018) were significantly associated with EF. After the multivariate analysis, only GA <28 weeks predicted EF with an adjusted odds ratio of 2.621 (95% confidence interval: 1.118 – 6.146).

Conclusion

EF rate in preterm infants admitted at the NICU of SQUH was within international rates. GA <28 weeks was the only predictor of the identified extubation failure. Neonatal practitioners need to seriously consider extreme prematurity in the extubation process and consider implementing strategies to decrease extubation failure in this group of fragile infants.

Keywords: Premature Infants, Neonate, Airway extubation, Risk Factors, Oman

Advances in Knowledge

- This study identified a neonatal extubation failure rate of 24.3% and reaffirmed that extreme prematurity (gestational age <28 weeks) is an important predictor in intubated preterm infants admitted to a level III neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) in Oman.

Application to Patient Care

- Health-care professionals in NICUs need to seriously consider extreme prematurity prior to extubation of preterm infants and implement strategies that may help decrease extubation failure. These include formal assessment of extubation readiness and use of positive pressure ventilation as post-extubation respiratory support.

Invasive mechanical ventilation is a life-supporting intervention used for patients with respiratory failure, including preterm infants in neonatal intensive care units (NICUs). Despite this advantage, extubation failure (EF) is a recurrent issue. EF occurs in approximately 40% of intubated extremely low birth weight infants globally, but is highly variable between 10–30%.1,2 This is partly due to the absence of a consistent definition for and standardised criteria to determine EF.2 EF has been defined as reintubation within 24, 48 and 72 hours; however, some patients have required reintubation up to seven days post-extubation.2,3

It is of utmost importance to extubate infants as soon as they are ready. Prolonged intubation and mechanical ventilation in preterm infants are associated with significant adverse effects including ventilator-associated pneumonia, bronchopulmonary dysplasia, sepsis and subglottic stenosis.3,4 However, this is a tenuous balancing act because premature extubation may lead to EF, which itself is associated with serious complications such as prolonged mechanical ventilation, prolonged hospital stay, higher mortality rate and complications related to the reintubation procedure itself.5–8

In order to find an optimal strategy for successful extubation in preterm infants, there must be an awareness of potential risk and success factors. Previous studies had identified predictors of EF such as lower 5-minute Apgar score, poor acid-base homeostasis, lower gestational age (GA; ≤28 weeks), post-extubation lung collapse, patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) and acquired pneumonia.9–12 Similarly, Chawla et al. identified markers of successful extubation in preterm infants, including higher 5-minute Apgar score and arterial pH prior to extubation, lower peak fractional concentration of inspired oxygen (FiO2) on the first day of life and prior to extubation, lower arterial partial pressure of carbon dioxide prior to extubation and “non-small” for GA.13

Currently, there are no studies regarding EF in preterm infants in Middle Eastern countries. This study aimed to describe the EF rate among intubated preterm infants in a tertiary care NICU in Oman and determine the risk factors associated with EF. It is anticipated that this study will provide specific criteria that neonatal practitioners can use to assess extubation readiness in preterm infants in order to optimise success.

Methods

This retrospective case-control study was conducted at a level III NICU of Sultan Qaboos University Hospital (SQUH), in Muscat, Oman. SQUH is a tertiary and academic perinatal hospital and has approximately 5,000 deliveries per year; its NICU has a 24-bed capacity. Eligible infants were intubated preterm infants (<37 weeks) admitted over a period of five years from January 2013 to December 2017. Infants who died prior to extubation, extubated for palliative care/comfort care, transferred to another hospital with an endotracheal tube (ETT), had an unplanned/accidental extubation or were tracheostomised were excluded. Only the first planned extubation attempt for each patient was assessed for this study. EF was defined as the need for reintubation within seven days of a planned extubation.2,3 The patients’ electronic charts were reviewed and specific predefined clinical variables including patient’s demographic data, pre-extubation ventilation parameters (mode, respiratory rate [RR], peak inspiratory pressure [PIP], peak end expiratory pressure [PEEP], tidal volume [Vt in mL/kg], FiO2), blood gas values (pH, partial pressure of carbon dioxide, bicarbonate [HCO3−] and base excess [BE]) and other risk factors of EF were collected. Blood gas values included a mix of arterial, venous and capillary samples.

All infants were ventilated using Dräger babylog® VN500 or SLE5000 ventilators (Dräger, Lübeck, Germany). The primary ventilation mode was pressure control conventional ventilation from 2013 until 2016 and volume-targeted conventional ventilation in 2017. High frequency oscillatory ventilation was used as a rescue mode. Infants were extubated once they were on minimal ventilatory parameters (PIP/PEEP: 16/5, RR: 30/min, FiO2 <0.35), had normal blood gases and were deemed ready by the medical team (established spontaneous breathing, hemodynamically stable). Post-extubation interventions included bubble nasal, nasal non-invasive positive pressure ventilation for infants <1,000 g and high flow nasal cannula for late preterm. Pre-and post-extubation blood gas tests were performed one to two hours prior to and after extubation, respectively.

The study population was classified into two groups: EF and extubation success (ES). Descriptive statistics included mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median and interquartile range (IQR) for continuous variables and counts and percentages for categorical variables. Normality of continuous variables was tested using the One-Sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. The differences in patient characteristics and possible risk factors between the ES and EF groups were tested using the Chi-squared test for categorical variables, independent sample t-test for normally distributed continuous variables and Mann-Whitney U test for non-normally distributed continuous variables. Adjusted binary logistic regression analysis was performed to determine predictors of EF using clinical variables that were significantly different between the two groups (EF versus ES). After obtaining the results of these statistical analyses (post-hoc), the analyses in the sub-group of infants <28 weeks GA (multivariate regression analysis) was repeated; however, it was not completed as the sample size was small and only one variable was significant in the univariate analysis. Missing data was excluded from the data analyses. Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), Version 23.0 (IBM Corp., Chicago, Illinois, USA) was used for data analysis. A P value of ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethical approval was obtained through the institution’s Medical Research Ethics Committee (MREC#1699).

Results

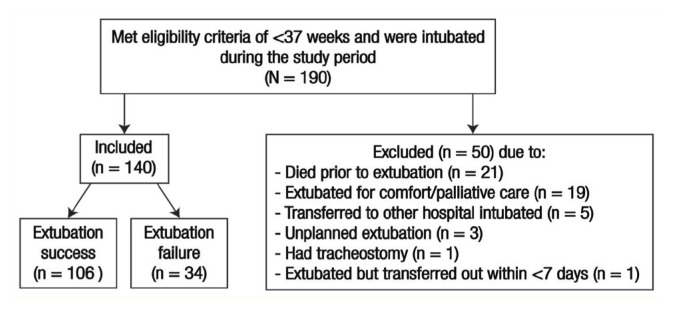

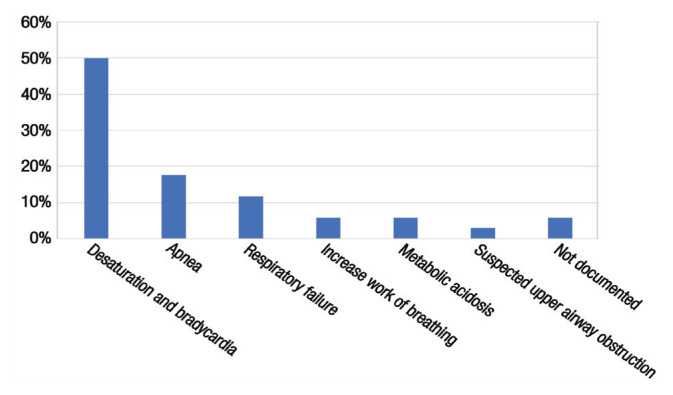

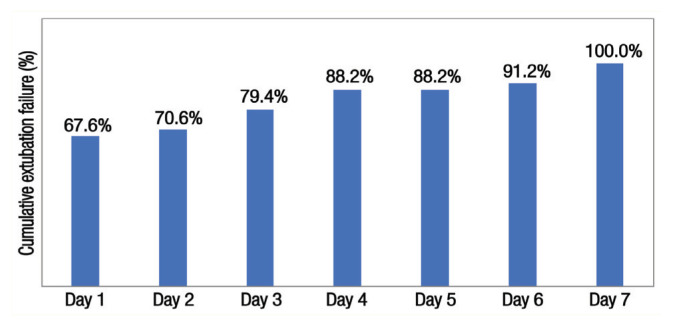

A total 140 infants were included in this study, out of which 34 (24.3%) failed extubation [Figure 1]. The mean GA was higher in the ES group compared to the EF group (31.6 ± 3.0 versus 26.1 ± 1.2 weeks). Approximately 75% of infants were <32 gestational weeks, which was equally distributed between the ES (74%) and EF (79%) groups (P = 0.649). The most common reasons for reintubation were desaturation and bradycardia (50%) followed by apnoea (17.7%) and respiratory failure (11.8%) [Figure 2]. The majority of extubation failures occurred within the first three days of extubation (79.4%) [Figure 3].

Figure 1.

Flowchart showing the study population selection.

Figure 2.

Reported reason for reintubation of infants in the neonatal intensive care unit (n = 34).

Figure 3.

Cumulative extubation failure per day of infants in the neonatal intensive care unit (n = 34).

There were significant differences between the EF and ES groups for the following three clinical variables: GA <28 weeks (P = 0.029), 1-minute Apgar score (P = 0.023) and PDA (P = 0.018). Infants with EF had significantly higher total mechanical ventilation (MV) days as well as longer length of hospital stay compared to those with ES (16 versus 3 days; P <0.001 and 67 versus 54.5 days; P = 0.01, respectively) [Table 1]. There were no significant differences in other clinical variables (5-minute Apgar score, birth weight [BW], weight at intubation and extubation, day of life at intubation and extubation, caffeine use, pre-extubation haemoglobin [Hb] level), intraventricular haemorrhage rate, pre-extubation ventilatory variables (mode, Vt, PIP, PEEP, RR, FiO2) and pre-extubation blood gas results [Tables 1 and 2]. After extubation, pH (P <0.001), HCO3− (P <0.001) and BE (P <0.001) were significantly lower in the EF compared to the ES group [Table 2]. Most infants (81.4%) had a five-minute APGAR score >6.

Table 1.

Characteristics of extubation failure and extubation success groups (N = 140)

| Characteristic | n (%) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ES (n = 106) | EF (n = 34) | ||

| Gestational age <28 weeks | 35 (33.0) | 19 (55.9) | 0.029* |

| Male gender | 58 (54.7) | 20 (58.8) | 0.825* |

| Mean 1-minute Apgar ± SD | 5.98 ± 2.22 | 4.88 ± 2.38 | 0.023† |

| Mean 5-minute Apgar ± SD | 8.10 ± 1.62 | 7.72 ± 1.63 | 0.117† |

| Mean birth weight in kg ± SD | 1.44 ± 0.82 | 1.34 ± 0.73 | 0.448† |

| Mean weight at intubation in kg ± SD | 1.46 ± 0.85 | 1.32 ± 0.70 | 0.481† |

| Mean weight at extubation in kg ± SD | 1.45 ± 0.82 | 1.33 ± 0.76 | 0.370† |

| Patent ductus arteriosus‡ | 39 (36.8) | 21 (61.8) | 0.018* |

| Intraventricular haemorrhage‡ | 14 (13.2) | 5 (14.7) | 1.000* |

| Caffeine | 78 (73.6) | 27 (79.4) | 0.649* |

| Median day of life at intubation (IQR) | 1 (0) | 1 (0) | 0.798§ |

| Median day of life at extubation (IQR) | 3 (5) | 2.5 (6) | 0.965§ |

| Median total mechanical ventilation in days (IQR) | 3 (4) | 16 (26.5) | 0>.001§ |

| Median length of hospital stay in days (IQR) | 54.5 (38.8) | 67 (54.3) | 0.01§ |

ES = extubation success; EF = extubation failure; SD = standard deviation; IQR = interquartile range.

Using Chi-square test.

Using independent sample t-test.

Grade and diagnosis data were not collected.

Using Mann-Whitney U test.

Table 2.

Ventilator and blood gas parameters 1–2 hours prior to and after extubation of infants (N = 140)

| Variable | n (%) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ES (n = 106) | EF (n = 34) | ||

| Prior to extubation | |||

| Mode of ventilation i.e. SIMV | 68 (64.2) | 20 (58.8) | 0.722* |

| Median RR in breaths/min (IQR) | 30 (10) | 25 (5) | 0.093† |

| Median PIP in cmH2O (IQR) | 15 (1) | 15 (2) | 0.461† |

| Median PEEP in cmH2O (IQR) | 6.0 (0) | 6.0 (0.05) | 0.021† |

| Median Vt in mL/kg (IQR) | 4.9 (3.6) | 4.9 (2.5) | 0.640† |

| Median FiO2 in % (IQR) | 23 (4) | 25 (7.5) | 0.228† |

| Median pH (IQR) | 7.39 (0.08) | 7.38 (0.1) | 0.644† |

| Median pCO2 (IQR) | 37.5 (13.4) | 35.5 (13.9) | 0.513† |

| Median HCO3− (IQR) | 22.4 (3.7) | 21.4 (2.6) | 0.057† |

| Median BE (IQR) | −2.5 (4.8) | −3.3 (4.05) | 0.126† |

| Median Hb in g/dL (IQR) | 13.5 (3.1) | 13.9 (3.6) | 0.363† |

| After extubation | |||

| Respiratory support i.e. CPAP | 77 (72.6) | 28 (82.4) | 0.720* |

| Median pH (IQR) | 7.36 (0.08) | 7.32 (0.13) | <0.001† |

| Median pCO2 (IQR) | 41.2 (1 3.97) | 41.7 (18) | 0.298† |

| Median HCO3− (IQR) | 21.7 (3.4) | 19.6 (2.9) | <0.001† |

| Median BE (IQR) | −3.0 (4.2) | −5.9 (4.4) | <0.001† |

ES = extubation success; EF = extubation failure; SIMV = synchronised intermittent mandatory ventilation; RR = respiratory rate; IQR = interquartile range; PIP = peak inspiratory pressure; PEEP = positive end expiratory pressure; FiO2 = fraction of inspired oxygen; Hb = haemoglobin; HCO3− = bicarbonate; PCO2 = partial pressure of carbon dioxide; Vt = tidal volume.

Using Chi-squared test.

Using Mann-Whitney U test.

After the multivariate analysis, only the variable GA <28 weeks remained as a significant predictor of EF; the 1-minute Apgar score and PDA were no longer associated with EF [Table 3].

Table 3.

Predictors of infant extubation failure

| Variable | OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Univariate | Multivariate* | |

| PDA | 2.775 (1.251–6.154 | 2.326 (0.967–5.592) |

| GA<28 weeks | 2.570 (1.168–5.655) | 2.621 (1.118–6.146) |

| 1-minute Apgar | 2.997 (1.190–7.548) | 2.533 (0.958–6.695) |

OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval; PDA = patent ductus arteriosus; GA = gestational age.

Adjusted binary logistic regression analysis performed.

For the post-hoc subgroup analysis of infants of GA <28 weeks (n = 54), 35 (64.8%) had ES and 19 (35.2%) had EF. Given the results of the multivariate analyses on the whole cohort, it is not surprising that the presence of PDA in infants was significantly higher in the EF group (n = 15 out of 19, 78.9%) compared to the ES group (n = 14 out of 35, 40.0%; P = 0.03). Similar to the whole group, the median (IQR) of total MV days was higher in the EF group (20 [23] versus 5 [10] days; P <0.001), but not significantly different for the length of hospital stay (87 [53] versus 70 [15] days; P = 0.142) compared to the ES group. The median length of stay for the entire subgroup was 72.5 days. All other variables were not significantly different between the ES and EF groups.

Discussion

This study determined the EF rate (and associated risk factors) among intubated preterm infants in a tertiary care NICU in Oman. The EF rate was found to be on the upper boundary of the 10–30% EF rate range found by Al-Mandari et al.; however, the majority of respondents (93%) in that study defined EF as occurring within 72 hours.2 The longer the period of time after extubation, the higher the risk of reintubation.1 Thus, the researchers’ definition of reintubation within seven days may be a more accurate reflection of EF rate. Compared with other EF studies using 5–7 days post-extubation as their benchmark, the present study’s EF rate was similar to Hermeto et al. (23.1%) and Wang et al. (23.5%) but lower than Chawla et al. (42%) and Stefanescu et al. (40%).1,10,11,13 However, it is important to consider the differences in GA in these studies as they may have contributed to the difference in EF rates as well. The association of EF with extreme prematurity (exclusively <28 weeks GA) has been inconsistent in the literature as some studies showed an association while others did not.9–14

Costa et al. as well as other authors found that the 5-minute Apgar score was significantly lower for those with EF compared to ES.9,10,13 This association was absent in the present study probably because most infants (81.4%) had a high 5-minute Apgar score of >6 [Table 1]. In addition, the 5-minute Apgar score was missing for five infants (3.6%).

Loss of impact of PDA diagnosis on the extubation outcome on multivariate regression is likely due to the influence of GA, as the present study’s post-hoc subgroup analyses of infants <28 weeks showed a significant difference in PDA presence between the EF and ES groups. The impact of PDA on extubation outcomes continues to be a controversial issue. Hermeto et al. and Chawla et al. found significant associations between EF and the presence of PDA, while Wang et al. and Szymankiewicz et al. did not.6,10,11,15 Similarly, the association between BW and EF is aligned with previously published studies, but contrasts with the findings of other studies which showed that lower BW is associated with an increased chance of EF.10–12,14,16 In the present study, median BWs were not associated with EF, likely because the BWs were consistently larger (>1,000 g).

Randomised trials of prophylactic use of caffeine showed increased chances of successful extubation in preterm infants within one week since birth.17 The lack of difference in caffeine use in this study was most likely because the present study’s NICU routinely uses caffeine in all preterm infants <32 weeks GA. This constitutes approximately 75% of the present study’s sample size and was equally distributed between the ES (74%) and EF (79%) groups (P = 0.649).

The absence of differences in pre-extubation ventilation parameters and blood gas results between EF and ES groups in the present study was similar to Wang et al. but differed from Chawla et al. who found that lower pH, higher CO2 and higher FiO2 prior to extubation were significantly associated with EF.10,11 In addition, Shalish et al. found a significant correlation between lower pre-extubation PEEP and EF.16 As expected, the present study found significantly worse post-extubation blood gas values in the EF compared to the ES group; this is similar to Wang et al.’s study.11 However, these factors cannot be used to predict the risk of extubation failure.

Brix et al. found that Hb <8.5 mmol/L was associated with EF.18 The present study showed no significant difference in pre-extubation Hb level between the EF and ES groups, likely because the study population had normal mean Hb levels >8.5 mmol/L prior to extubation (related to the unit’s transfusion policy).

The longer duration of MV and hospital length of stay in the EF group are expected morbidities of EF. This is consistent with many previous studies.6,9,12,16 The duration of MV for the EF group was also significantly higher for the subgroup of infants <28 weeks GA, but not significantly different for hospital length of stay. It is speculated that, in the <28 weeks GA subgroup, other complications impacted and balanced out their hospital length of stay, because the median for the whole <28 weeks GA subgroup was high at 72.5 (IQR = 33.75%) days (e.g. bronchopulmonary dysplasia). These subgroup results also support that GA (especially <28 weeks) impacted ES and the length of hospital stay for all the infants included in the present study. Prospective, clinical trials with larger sample sizes are needed to confirm these results.

A number of limitations in this study need to be considered. This study had a retrospective design which has more biases associated with confounding factors and causality.19 Moreover, some of the data were not documented in patients’ electronic charts, resulting in missing data and a smaller sample size, which could have negatively affected the results. The subgroup analysis on infants <28 weeks GA was done post-hoc and resulted in a decrease in the sample size. This was done for exploratory reasons; inferences on these results should be made with caution. Blood gas values were arterial, venous or capillary; these could not be distinguished as they were not categorised separately in patients’ charts. Finally, this study only reviewed the charts of preterm infants of a single tertiary centre in Oman and may not be generalisable to other settings.

Conclusion

EF rate (within seven days of extubation) in preterm infants admitted to a tertiary care NICU in Oman, was found to be 24.3%; this is within reported international rates. GA <28 weeks was found to be the main predictor of EF. Neonatal practitioners need to seriously consider extreme prematurity before extubation. It may be beneficial to implement strategies known to help decrease EF such as formal assessment of extubation readiness and post-extubation non-invasive positive pressure ventilation in this group of infants.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

FUNDING

No funding was received for this study.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

HM conceptualised the study while HM and BR prepared the research proposal. BR and AK collected the data. BR, MN and SR analysed the data. All authors contributed to the drafting of the manuscript and approved the final version.

References

- 1.Stefanescu BM, Murphy WP, Hansell BJ, Fuloria M, Morgan TM, Aschner JL. A randomized, controlled trial comparing two different continuous positive airway pressure systems for the successful extubation of extremely low birth weight infants. Pediatrics. 2003;112:1031–8. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.5.1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Al-Mandari H, Shalish W, Dempsey E, Keszler M, Davis PG, Sant'Anna G. International survey on periextubation practices in extremely preterm infants. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2015;100:F428–31. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2015-308549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miller JD, Carlo WA. Pulmonary complications of mechanical ventilation in neonates. Clin Perinatol. 2008;35:273–81. x–xi. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2007.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kamlin CO, Davis PG, Morley CJ. Predicting successful extubation of very low birthweight infants. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2006;91:F180–3. doi: 10.1136/adc.2005.081083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baisch SD, Wheeler WB, Kurachek SC, Cornfield DN. Extubation failure in pediatric intensive care incidence and outcomes. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2005;6:312–18. doi: 10.1097/01.PCC.0000161119.05076.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chawla S, Natarajan G, Gelmini M, Kazzi SN. Role of spontaneous breathing trial in predicting successful extubation in premature infants. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2013;48:443–8. doi: 10.1002/ppul.22623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kurachek SC, Newth CJ, Quasney MW, Rice T, Sachdeva RC, Patel NR, et al. Extubation failure in pediatric intensive care: A multiple-center study of risk factors and outcomes. Crit Care Med. 2003;31:2657–64. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000094228.90557.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guardia CG, Moya FR, Sinha S, Gadzinowski J, Donn SM, Simmons P, et al. Reintubation and risk of morbidity and mortality in preterm infants after surfactant replacement therapy. J Neonatal-Perinatal Med. 2011;4:101–9. doi: 10.3233/NPM-2011-2736. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Costa AC, de Schettino RC, Ferreira SC. [Predictors of extubation failure and reintubation in newborn infants subjected to mechanical ventilation]. Rev Bras Ter Intensiva. 2014;26:51–6. doi: 10.5935/0103-507X.20140008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hermeto F, Martins BM, Ramos JR, Bhering CA, Sant'Anna GM. Incidence and main risk factors associated with extubation failure in newborns with birth weight < 1,250 grams. J Pediatr (Rio J) 2009;85:397–402. doi: 10.1590/S0021-75572009000500005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang SH, Liou JY, Chen CY, Chou HC, Hsieh WS, Tsao PN. Risk factors for extubation failure in extremely low birth weight infants. Pediatr Neonatol. 2017;58:145–50. doi: 10.1016/j.pedneo.2016.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hiremath GM, Mukhopadhyay K, Narang A. Clinical risk factors associated with extubation failure in ventilated neonates. Indian Pediatr. 2009;46:887–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chawla S, Natarajan G, Shankaran S, Carper B, Brion LP, Keszler M, et al. Markers of successful extubation in extremely preterm infants, and morbidity after failed extubation. J Pediatr. 2017;189:113–19e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.04.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dimitriou G, Greenough A, Endo A, Cherian S, Rafferty GF. Prediction of extubation failure in preterm infants. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2002;86:F32–5. doi: 10.1136/fn.86.1.F32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Szymankiewicz M, Vidyasagar D, Gadzinowski J. Predictors of successful extubation of preterm low-birth-weight infants with respiratory distress syndrome. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2005;6:44–9. doi: 10.1097/01.PCC.0000149136.28598.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shalish W, Latremouille S, Papenburg J, Sant'Anna GM. Predictors of extubation readiness in preterm infants: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2019;104:F89–97. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2017-313878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Henderson-Smart DJ, Davis PG. Prophylactic methylxanthines for endotracheal extubation in preterm infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010. p. Cd000139. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Brix N, Sellmer A, Jensen MS, Pedersen LV, Henriksen TB. Predictors for an unsuccessful INtubation-SURfactant-Extubation procedure: A cohort study. BMC Pediatr. 2014;14:155. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-14-155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hulley SB, Cummings SR, Newman TB. Designing Cross-Sectional and Cohort Studies. In: Hulley SB, Cummings SR, Browner WS, Grady DG, Newman TB, editors. Designing Clinical Research. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2013. pp. 85–96. [Google Scholar]