Abstract

Background:

Patient-reported outcomes (PROs) are clinical tools that measure patients’ goals of care and assess patient-reported physical, mental, and social wellbeing. Despite their value in advancing patient-centered care, routine use of PROs in stroke management has lagged. As part of the pragmatic COMprehensive Post-Acute Stroke Services (COMPASS) trial, we developed COMPASS-CP, a clinician-facing application that captures and analyzes PROs for stroke and TIA patients discharged home and immediately generates individualized electronic care plans (CP). In this report, we: 1) present our methods for developing and implementing COMPASS-CP PROs, 2) provide examples of care plans generated from COMPASS-CP, 3) describe key functional, social, and behavioral determinants of health captured by COMPASS-CP, and 4) report on clinician experience with using COMPASS-CP in routine clinical practice for care planning and engagement of stroke and TIA patients discharged home.

Methods and Results:

We report on the first 871 patients enrolled in 20 North Carolina hospitals randomized to the intervention arm of COMPASS between July 2016 and February 2018; these patients completed a COMPASS follow-up visit within 14 days of hospital discharge. We also report user satisfaction results from 56 clinicians who used COMPASS-CP during these visits. COMPASS-CP identified more cognitive and depression deficits than physical deficits. Within 14 days post-hospitalization, less than half of patients could list the major risk factors for stroke, 36% did not recognize blood pressure as a stroke risk factor, and 19% of patients were non-adherent with prescribed medications. Three-fourths of clinicians reported that COMPASS-CP identifies important factors impacting patients’ recovery that they otherwise may have missed, and two-thirds were highly satisfied with COMPASS-CP.

Conclusions:

The COMPASS-CP application meets an immediate need to incorporate PROs into the clinical workflow to develop patient-centered care plans for stroke patients and has high user satisfaction.

Keywords: stroke, transient ischemic attack, patient-reported outcomes, post-acute care, transitional care, care plan, Cerebrovascular Disease/Stroke, Transient Ischemic Attack (TIA), Quality and Outcomes, Health Services

INTRODUCTION

Patient-reported outcomes (PROs) systematically assess patient-reported physical, mental, and social wellbeing.1,2 Defined as “any report of the status of a patient’s health condition that comes directly from the patient, without interpretation of the patient’s response by a clinician or anyone else,”2 PROs are captured by asking patients questions about symptoms, physical, cognitive, and social function, and quality of life.3 They provide clinicians with valuable information about the patient’s health literacy, goals of care, satisfaction with care, and adherence to prescribed medication or therapy.4,5

Capturing the voice of the patient through PROs and immediately incorporating this information into individualized care planning is critical to advancing patient-centered care. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) emphasizes that a key goal of care management is to incorporate patients’ goals of care and social and functional factors that influence their ability to self-manage for recovery, health, and independence.6 The Medicare Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) reimbursement model emphasizes the importance of the routine collection of PROs and individualized care planning in the provision of value-based care.7 In addition, the American Heart Association (AHA) emphasizes the role of social and functional determinants of health in cardiovascular outcomes and the importance of measuring and incorporating these factors into risk factor management and treatment plans.6,8–10

Nonetheless, clinicians’ use of PROs to inform routine clinical decision-making and care planning has been slow.11–13 Indeed, fewer than one in five hospitals routinely use PROs in the healthcare decision-making process.14 Providers and staff are often resistant to incorporate PROs into the clinical workflow, given their already limited time, staff, and financial resources.15 Although incorporating PROs into routine clinical practice does not lengthen patient visit times appreciably,16,17 achieving buy-in from healthcare providers remains challenging.18 PROs that are not perceived as relevant, meaningful or interpretable by clinicians or researchers will not be endorsed and implemented.19 Furthermore, even when PROs are collected, translating those results into actionable clinical decision-making can be challenging.20 Incorporating PROs into clinical care requires real-time analysis and scoring of data, and guidance in interpreting and communicating them.11 To date, few applications support this real-time analysis, scoring, and interpretation,12 and effective incorporation of PROs into electronic health records (EHR) has been slow to progress.13 Despite commercially-available EHR platforms and a call for increased incorporation of PROs in EHR, embedded PROs have been limited to multiple static forms or simple branching questionnaires that are burdensome to both the patient and the clinician.21 Further, responses cannot be immediately analyzed and used to inform care. In addition, the incompatibility of EHR and information technology (IT) systems among providers hampers sharing of PROs and care plans across the continuum of care.14,22 Finally, providers, systems, and payers cite strong concerns over the IT costs needed to incorporate PROs into clinical care.21 Thus, an application for real-time utilization of PROs that overcomes these numerous challenges could have a profound positive influence on authentic shared decision-making and individualized care planning.

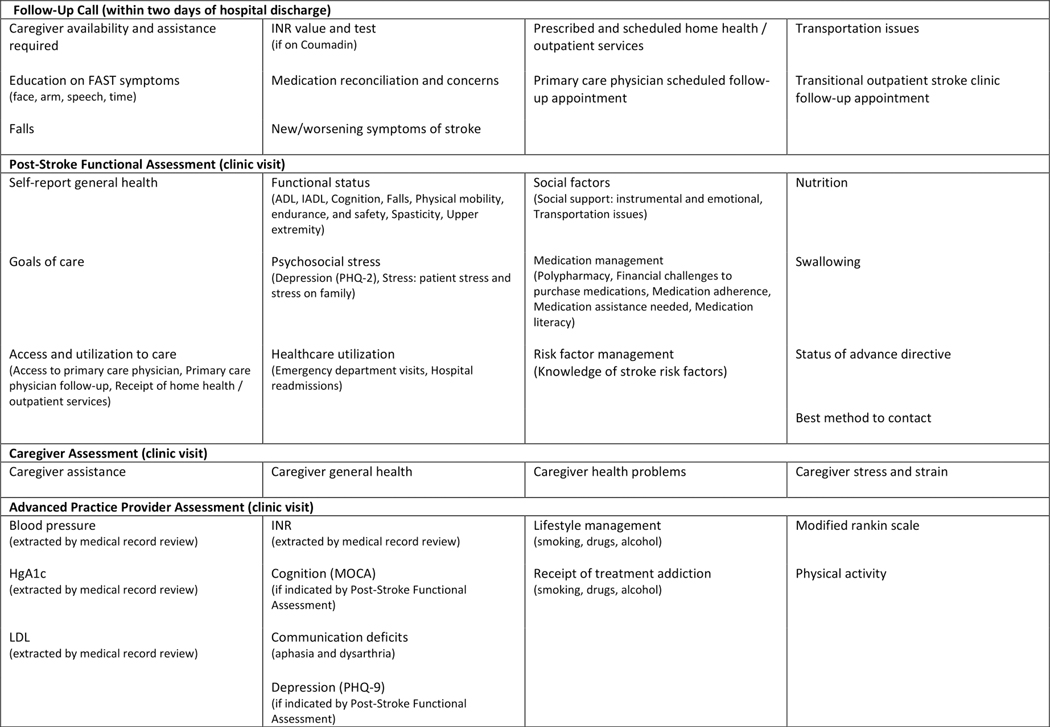

A team of patients, caregivers, multidisciplinary clinicians, and clinical researchers of the COMprehensive Post-Acute Stroke Services (COMPASS) study developed COMPASS-CP,23 an electronic care plan generating application that captures multiple factors including social, behavioral, and functional determinants of recovery, health, and independence through PROs (Figure 1).23,24 COMPASS-CP is designed to be administered by a clinician in a clinical or home setting. It also assesses caregiver abilities and resources critical for patients during the post-stroke care period. COMPASS-CP can be used as a web-based or iPad application. Its questionnaires are simple to administer but are designed to yield a comprehensive overview of factors that can impair a patient’s ability to manage his or her health and recovery.

Figure 1.

Domains measured in the COMPASS study post-discharge follow-up after stroke or transient ischemic attack.

*ADL = Activities of Daily Living; IADL = Instrumental Activities of Daily Living; LDL = Low-density Lipoproteins; HgA1c = Hemoglobin A1c; INR = International Normalized Ratio; MoCA = Montreal Cognitive Assessment; PHQ-9 = 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire

The unique algorithms in COMPASS-CP generate a personalized care plan in real-time clinical practice, immediately identifying, prioritizing, and recommending interventions or support services that could benefit the patient. This information drives recommendations and coordination of appropriate medical, rehabilitation, or community resources to improve the patient’s function, independence, and quality of life. Personalized care plans are available to patients, caregivers, and all care providers.

The COMPASS-CP prototype was developed as part of a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) pragmatic trial of the COMPASS care model. 23,24 The COMPASS-CP application is specific for stroke, a condition which requires early supported discharge and coordinated post-acute care management.25,26 The onset of stroke is sudden, and survivors and their caregivers are frequently ill-prepared.27–29 Functional limitations after mild stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA) are frequently not fully recognized until patients return home and try to resume their daily lives,30–32 making self-management of health and full recovery more difficult.1,23,33 We posit that post-discharge care management that identifies and addresses social and functional deficits and contexts of recovery may improve stroke knowledge, secondary risk factor management, and quality of life, and reduce the likelihood of severe stroke complications.34

Here we present our methods to capture PROs among COMPASS participants and methods for administering PRO questionnaires, capturing responses electronically, and analyzing data in real-time to inform individualized care. We also provide examples of care plans generated from COMPASS-CP. We then describe key social and functional determinants of health, knowledge of cardiovascular risk factor management, medication management, access to care, and caregiver health and needs among those enrolled to date in the intervention arm of COMPASS (n=871). Finally, we report clinicians’ experience with using COMPASS-CP in routine clinical practice for care planning and engagement of stroke and TIA patients discharged home.

METHODS

COMPASS Study

COMPASS-CP is an integral part of the COMPASS model, which is being evaluated in the COMPASS pragmatic trial, the methods and design of which have been published.23,24 The COMPASS study was approved by the Wake Forest University Health Sciences institutional review board (IRB), which acts as a central IRB for 36 participating hospitals. Local IRB approval was granted by 5 additional sites. Informed consent is obtained on the 90-day outcomes data collection call for all patients and at the clinic visit for patients at intervention hospitals.35

At the conclusion of COMPASS trial and after analysis by the study team, the data, analytic methods, and study materials will be made available to other researchers for purposes of reproducing results or replicating procedures, upon reasonable request to the corresponding author and in accordance with PCORI’s Policy for Data Access and Data Sharing.36

COMPASS-CP PROs and Care Plans

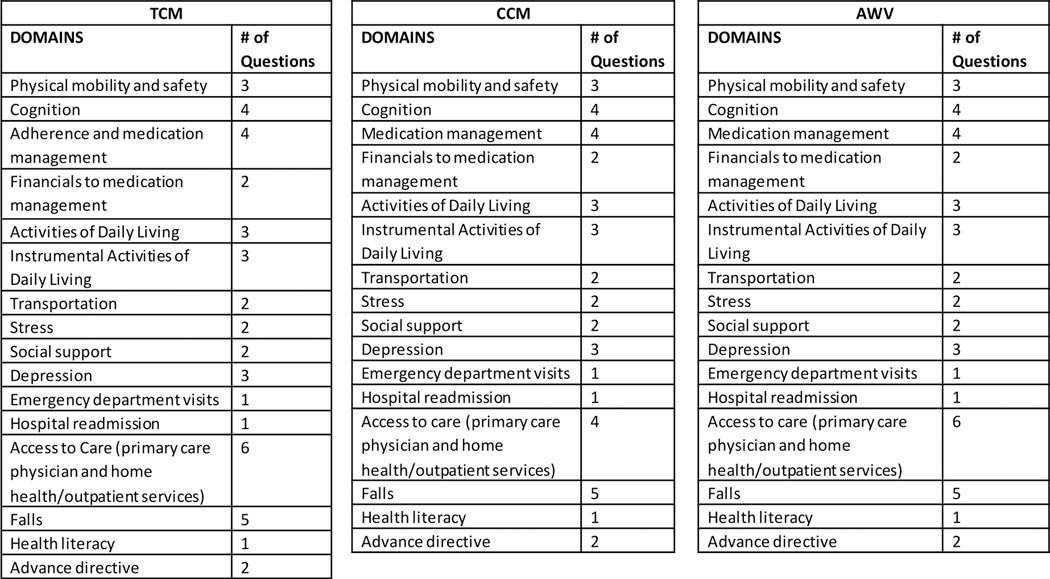

It is not feasible, in the confines of a single clinic visit, to utilize currently available standardized assessment measures to capture all domains expected by CMS for transitional care, chronic care management, and the annual wellness visit (Figure 2).37–40 Therefore, we developed questions that capture information within the CMS-recommended domains and other highly relevant factors (e.g., cognitive function, health literacy, medication management and adherence, cardiovascular risk factor management, knowledge of stroke warning signs) (Figure 1) that are feasible to query within the time constraints of a clinic visit.

Figure 2.

Domains recommended for assessment by CMS Transitional Care Management (TCM), Chronic Care Management (CCM), and Annual Wellness Visit (AWV).

The multidisciplinary COMPASS team—including neurologists, primary care physicians, advanced practice providers, nurses, pharmacists, therapists, social workers, Area Agency on Aging staff, and patient and caregiver stakeholders—selected candidate questions by reviewing the Institute of Medicine’s recommendations for social and functional factors to be included in EHR; 41 CMS’s recommended factors for assessments for transitional care, chronic care, and the annual wellness visit (Figure 2);37–40 and comprehensive care management indicators specified by the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act.8,39

We vetted candidate questions with patients, caregivers, and clinicians from Wake Forest Baptist Health (WFBH) clinical stroke team’s transitional care clinic, where COMPASS-CP was integrated into the clinical workflow. This process included a focus group with three patients and two caregivers, followed by an in-person meeting with an expert in health literacy and health disparities to ensure questions are accessible and culturally sensitive. From there, in an iterative process, two advanced practice providers and a nurse coordinator provided continuous feedback based on their experiences implementing COMPASS-CP at the WFBH clinic until questionnaires could be administered efficiently and care plans could be generated and communicated effectively. Additionally, we asked our home health partners to review and provide feedback on questions to capture medication management, cardiovascular risk factor knowledge, symptom management, and access to primary care and rehabilitation services. (Figure 1) We also developed an assessment of caregiver health, stress, and needs that might impact a caregiver’s ability to support the patient, which is triggered if the patient reports requiring assistance with managing medications, preparing meals, doing housework, bathing, or dressing. Factors considered were those deemed most likely to impact stroke patients’ and caregivers’ ability to manage and optimize patients’ recovery, health, and independence. Next, we evaluated the questions for comprehension, literacy levels, and time to administer. Final questionnaires are provided in Supplement 1.

We then developed a web-based application that included the script, questions, validation rules and skip patterns to capture PROs with minimal burden for patients, caregivers, and clinicians. COMPASS staff administer web-based PRO questionnaires to the patient or proxy at two time points: over the phone by a nurse 2 days after hospital discharge, and in person by a nurse during a clinic visit 7 to 14 days post-discharge. Questionnaires were administered in English. For Spanish-speaking participants, interpreters assisted in administering questionnaires. The 2-day call takes approximately 10–15 minutes to complete, although it can take longer (30–45 minutes) for higher acuity stroke patients. Questionnaires at the clinic visit, on average, take less than 15 minutes to complete. The entire visit, including care plan coaching, can be completed within 60 minutes. Data are collected electronically via iPad or computer. Clinicians complete a 60-minute tutorial on COMPASS-CP and access to a web-based training demonstration before the tool is implemented at each trial site.

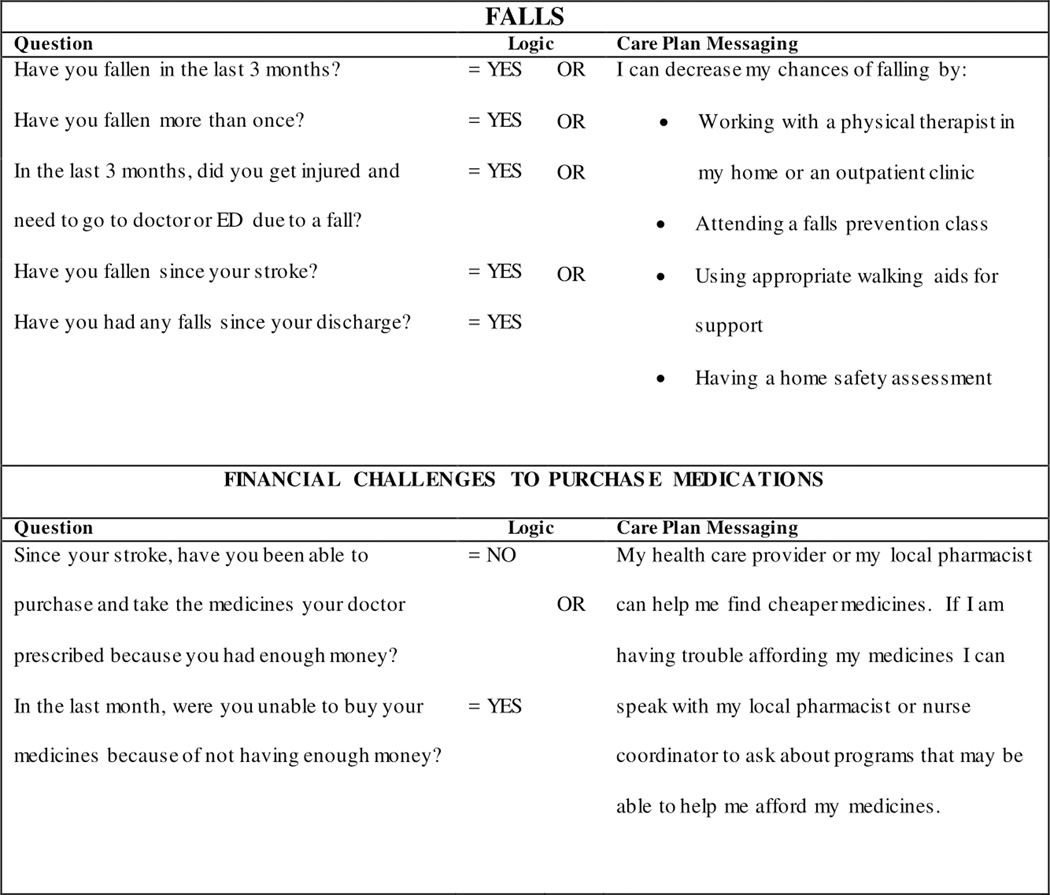

Embedded algorithms within COMPASS-CP integrate and assess electronic data and immediately generate actionable, individualized care plans. Figure 3 provides examples of the algorithms used for patients for whom falls and financial assistance needed to purchase medications were identified as important concerns. In addition, care plans are linked to a stroke-specific Community Resources Directory (CRD), systematically created for all counties served by COMPASS hospitals, and embedded in the COMPASS-CP algorithm. The CRD provides information on local resources that are available to meet a patient’s specific social, economic, behavioral, or environmental needs as identified by COMPASS-CP. These services and supports include home and community-based services, such as disease-specific support groups, caregiver support groups, adult day care, transportation, home delivered meals, and behavioral health services, and include evidence-based health and wellness programs such as chronic disease self-management and diabetes self-management education services. To populate the CRD, clinicians and community-based service providers at each hospital help to identify resources within the communities they serve, with special attention given to resources that provide services to those under age 60, the uninsured with no ability to pay, patients living in rural areas, patients with cognitive deficits, and those with limited access to transportation.

Figure 3.

Examples of COMPASS-CP algorithms for falls and financial challenges to purchase medications.

The COMPASS-CP algorithms evaluate the data captured in questionnaires and identify factors likely to influence recovery, health, and independence of the stroke survivor across each dimension of care (Figure 1) and needed referrals for community-based resources. These are used to generate the patient-facing COMPASS care plan, entitled “Finding My Way Forward for Recovery, Health, and Independence.” Care plans provide education, recommendations, and referrals across essential domains of self-management and care, anchored to the four cardinal directions of a compass:23

Numbers: Know your blood pressure, hemoglobin A1C, cholesterol etc.

Engage: Be active in mind, body and spirit through physical, cognitive, and social activity.

Support: Seek support for your and/or family stress, finances for medications, and transportation.

Willingness: Be willing to manage your medications and lifestyle.

COMPASS staff incorporate input and priorities from the patient and caregiver to create an individualized electronic care plan. The COMPASS nurse then shares the care plan with the patient and/or caregiver at the end of the 7–14 day clinic visit. Care plans are made available to the patient’s primary care physician (PCP) and post-acute care providers and uploaded into their respective EHRs in PDF form Supplement 2 provides an example of a care plan generated by COMPASS-CP.

PROs, care plans, and provider reports that list domains of concern are generated from the COMPASS-CP dashboard as shown in Supplement 3 and the processes are integrated into the clinical workflow as depicted in Supplement 4. A diagram of the COMPASS-CP architecture is included as Supplement 5.

Clinician User Experience

After launching the COMPASS Care model among hospitals in the intervention arm, we surveyed 56 clinicians from 19 of the 20 hospitals using COMPASS-CP to assess their satisfaction with the application in: (1) efficiency in Care Plan development, (2) identifying factors impacting patient self-management and caregiver needs, (3) patient/provider communication, (4) patient/caregiver engagement, and (5) patient satisfaction with care. Clinicians rated their satisfaction in each domain on a 5-point Likert scale (Strongly Agree, Agree, Neither Agree nor Disagree, Disagree, or Strongly Disagree). Surveys identified the type of clinician completing the questionnaire (nurse, nurse practitioner (NP), or physician assistant (PA)), the setting in which COMPASS-CP was used (neurology clinic, PCP office, or other), and how long the clinician has been using COMPASS-CP (less than 1 month, 1–2 months, 3–5 months, or 6 months or longer).

Statistical Analyses

We used SAS version 9.4 to analyze responses from all assessments. (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). We summarized data descriptively as frequencies (percentages) and means (standard deviations), as appropriate.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

Between July 2016 and February 2018, 871 patients were enrolled in the COMPASS intervention arm and returned within 14 days of their stroke or TIA for transitional care clinic follow-up visits. Patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. Half (50.0%) of patients with documented National Institute of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) scores had scores of less than 2. Data from the 7–14 day follow-up clinic visit revealed a continued presence of stroke risk factors.

Table 1.

Characteristics of COMPASS patients at hospital discharge (extracted from medical records), July 2016-February 2018, N=871.

| Characteristic | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age 65 years or Older | 526 (60.4) |

| Male | 443 (50.9) |

| Race | |

| White | 686 (78.8) |

| African-American | 159 (18.3) |

| Other | 24 (2.8) |

| Unknown | 2 (0.2) |

| Hispanic* | 16 (1.8) |

| Discharge Diagnosis | |

| Ischemic Stroke | 573 (65.8) |

| Transient Ischemic Attack | 268 (30.8) |

| Intracerebral Hemorrhage | 18 (2.1) |

| Ischemic Stroke with Hemorrhage | 4 (0.5) |

| Stroke, Not Otherwise Specified | 8 (0.9) |

| Insurance† | |

| Medicare Fee for Service | 437 (50.2) |

| Medicare Advantage | 78 (9.0) |

| Medicaid | 99 (11.4) |

| Private | 244 (28.0) |

| VA/CHAMPUS‡ | 28 (3.2) |

| Self-Pay/No Insurance | 75 (8.6) |

| Not Documented | 7 (0.8) |

| Aphasia at Presentation** | 196 (22.5) |

| Atrial Fibrillation and Discharged on Anticoagulant§ | 41 (57.7) |

| Ambulatory Status at Discharge | |

| Independent | 641 (73.6) |

| With Assistance | 47 (5.4) |

| Unable to Ambulate | 4 (0.5) |

| Not Documented | 179 (20.6) |

| Stroke Severity (NIHSS)‡ | |

| 0 | 280 (32.2) |

| 1 | 155 (17.8) |

| 2 | 105 (12.1) |

| 3–4 | 119 (13.7) |

| 5–7 | 56 (6.4) |

| >7 | 46 (5.3) |

| Not Documented | 110 (12.6) |

Compared to ‘No/Not documented.’

Categories not mutually exclusive.

VA = Veterans Affairs; CHAMPUS = Civilian Health and Medical Program of the Uniformed Services; NIHSS = National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale.

71 patients had history of AF at discharge and non-missing data on discharge medications

Denominator = 680.

Using COMPASS-CP to electronically capture PROs via nurse interview produced a complete set of data for each patient. Table 2 summarizes the factors identified by COMPASS-CP nurse-led interviews that could limit recovery, health, and independence. At the 7–14 day clinic visit, none of the 871 patients could list all seven key stroke risk factors (high blood pressure, smoking, diabetes, atrial fibrillation, heart disease, high cholesterol, and physical inactivity), and 70.5% did not receive a home health referral. Of those who did not receive a home health referral, 77.2 % were also not referred to outpatient therapy at hospital discharge.

Table 2.

Behavioral and lifestyle risk factors identified by COMPASS nurse via COMPASS-CP questionnaires, July 2016-February 2018.

| Behavioral and Lifestyle Risk Factors | N | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Know your Numbers—Lack of Knowledge of Stroke Risk Factors* | ||

| High Blood Pressure | 871 | 315 (36.2) |

| Smoking | 871 | 651 (74.7) |

| Diabetes | 871 | 689 (79.1) |

| Atrial Fibrillation | 871 | 801 (92.0) |

| Heart Disease | 871 | 760 (87.3) |

| High Cholesterol | 871 | 472 (54.2) |

| Physical Inactivity | 871 | 756 (86.8) |

| Engage | ||

| Physical Mobility and Safety Concerns | 871 | 292 (33.5) |

| Fall in Last 3 Months | 871 | 200 (23.0) |

| ADL Limitation† | 871 | 181 (20.8) |

| IADL Limitation† | 871 | 149 (17.1) |

| Depression (PHQ-2) † | 871 | 308 (35.4) |

| Upper Extremity Deficits | 871 | 179 (20.6) |

| Patient Stress | 871 | 273 (31.3) |

| Family Stress | 871 | 90 (10.3) |

| Support †† | ||

| Limited Instrumental Social Support | 871 | 282 (32.4) |

| Limited Emotional Social Support | 663 | 60 (9.0) |

| Willingness | ||

| Low Medication Adherence (MGLS) † | 871 | 169 (19.4) |

| Cognitive Deficits | 871 | 330 (37.9) |

| Financial Challenges to Medication Management | 871 | 159 (18.3) |

| Polypharmacy (≥5 medications/day)‡ | 871 | 639 (73.4) |

| Access to Care | ||

| Does not Have PCP† | 871 | 62 (7.1) |

| Has not Seen PCP in Last 3 Months † | 871 | 122 (14.0) |

| Has seen PCP in Last 3 Months but Not Since Stroke† | 871 | 199 (22.8) |

| No Home Health Referrals at Hospital Discharge | 759 | 535 (70.5) |

| No Outpatient Therapy Referrals at Hospital Discharge§ | 536 | 414 (77.2) |

| Self-Rated Health ** | ||

| Poor or Fair | 867 | 174 (20.1) |

| Caregiver Wellbeing ‡‡ | ||

| Caregiver Stress | 328 | 112 (34.1) |

| Poor or Fair Self-Rated Health** | 298 | 34 (11.4) |

| Health Issues or Responsibilities that Interfere with Caregiving§ | 295 | 61 (20.7) |

Unless otherwise noted, “No Response” was included in the numerator to avoid missing potential care concerns.

ADL = Activities of Daily Living; IADL = Instrumental Activities of Daily Living; MGLS = 4-item Morisky Green Levine Medication Adherence Scale; PCP = Primary Care Physician; PHQ-2 = 2-item Patient Health Questionnaire

Numerator includes patients that responded “Don’t know” and “No Response”.

Excludes patients prescribed home health services, as they are ineligible to receive outpatient therapy services; measured at 2-day follow-up call.

Denominator excludes “No Response”

Instrumental social support = having someone to help bathe/dress, etc. for 30 days if assistance is needed; Emotional social support = having a network of family/friends who visit as often as the patient would like.

COMPASS-CP triggered provider to complete Caregiver Assessment

In addition to physical concerns, COMPASS-CP identified a third of patients with possible depression using the PHQ-2 screening tool,23 patient stress, limited social support, and lack of follow-up with a primary care physician. Other issues identified included low medication adherence and/or financial challenges to medication management, polypharmacy (≥5 medications per day), and uncertainty about the purpose of prescribed medications. Nearly 40% of participants showed signs of cognitive dysfunction.

For over a third of caregivers, COMPASS-CP triggered the nurse to complete a caregiver assessment. Of these, over a third reported health issues that could interfere with caregiving (Table 2).

In the clinical evaluation portion of the clinic visit, COMPASS-CP captured lifestyle management factors and other variables impacting patients’ ability to manage their health (Table 3). COMPASS-CP identified nearly half of patients with low physical activity, almost a fifth with post-stroke communication deficits requiring speech therapy, and 6.0% without an able or willing caregiver.

Table 3.

Key behavioral, social, and clinical risk factors, and additional services needed, identified by advanced practice provider and entered into COMPASS-CP during follow-up clinic visit, July 2016-February 2018 *

| Domain | N | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Behavioral / Lifestyle Risk Factors † | ||

| Low Physical Activity (<20 minutes/day) | 793 | 374 (47.2) |

| Current Smoking | 807 | 147 (18.2) |

| Alcohol Use Over Recommended Daily Limit‡ | 807 | 29 (3.6) |

| Current Recreational Drug Use | 807 | 20 (2.5) |

| Social Risk Factors † | ||

| No Able and Willing Caregiver | 802 | 48 (6.0) |

| Clinical Risk Factors † | ||

| Communication Deficits Requiring Speech Therapy | 805 | 79 (9.8) |

| Systolic Blood pressure >140 mmHg | 805 | 298 (37.0) |

| LDL Cholesterol > 100 mg/dL | 634 | 317 (50.0) |

| Diabetic with Hemoglobin A1C > 8.0% | 478 | 84 (17.6) |

| International Normalized Ratio < 1.9 or 3.1 § | 114 | 96 (84.2) |

| Need for additional services identified | ||

| Assisted Living | 871 | 49 (5.6) |

| Skilled Nursing Facility | 871 | 4 (0.5) |

| Home Health Occupational/Physical Therapy | 871 | 426 (48.9) |

| Home Health Speech Therapy | 871 | 104 (11.9) |

| Home Health Nursing | 871 | 764 (87.7) |

These questions did not require complete data entry to proceed, so sections could be skipped, leading to some missing values.

Excludes those with missing advanced practice provider form or missing or invalid response.

For alcohol use, the threshold for women is 1 drink/day, and for men, 1–2 drinks/day.

Among patients anticoagulated with warfarin and with prothrombin measurements taken

Clinician User Experience and Satisfaction

We invited all COMPASS staff at the 20 intervention hospitals who were involved in the 7–14 day follow-up visit to participate in a survey querying their experience and satisfaction with using COMPASS-CP. We received survey responses from 44 of 59 clinicians (79%), representing 19 of 20 hospital units randomized to the intervention arm (95%).The follow-up visits were conducted in a range of settings: 9 in a neurology clinic, 1 in a cardiology clinic and the others in hospital based transitional care clinics or in primary care offices. Thirty-nine responders (89%) had used COMPASS-CP for 3 months or more. Of the 44 respondents, 27 were nurses, 11 were NPs, 5 were PAs, and 1 was a paramedic.

Approximately two-thirds of responding clinicians agreed that COMPASS-CP was an easier way to generate a care plan for patients than their usual methods and that the tool improved patient engagement in managing his/her recovery (Table 4). Three quarters reported that COMPASS-CP identified important patient needs that they otherwise would have missed, and that the caregiver assessment added value to the care plan. Over half reported that COMPASS-CP improved their communication with patients and caregivers, and nearly half felt that COMPASS-CP improved overall patient satisfaction with care.

Table 4.

Clinician User Satisfaction with COMPASS-CP Application (N=44)

| COMPASS-CP User Survey Question | Strongly Agree or Agree | Neither Agree Nor Disagree | Disagree or Strongly Disagree |

|---|---|---|---|

| Using the eCare Plan app is an easier way to develop a comprehensive care plan for the patient that the way I used to develop a care plan. | 67% | 23% | 9% |

| The eCare Plan app improves my efficiency in evaluating and managing the patient’s care during the 7–14-day clinic visit. | 56% | 35% | 9% |

| The eCare Plan app improves my efficiency in evaluating and managing the patient’s care during the 30- and 60-day follow-up calls. | 37% | 51% | 12% |

| The eCare Plan app makes my job easier. | 58% | 28% | 14% |

| The eCare Plan app identifies important factors impacting the patient’s recovery and ability to self-manage that I might have missed. | 74% | 16% | 9% |

| The caregiver assessment adds value to the care plan for the patient. | 77% | 16% | 7% |

| The community resource directory linked to the eCare Plan app helps patients get the referrals they need. | 56% | 33% | 12% |

| The eCare Plan app improves the patient’s communication with me during the 7–14 day clinic visit. | 54% | 33% | 14% |

| The eCare Plan app improves the caregiver’s communication with me when the caregiver assessment is triggered. | 63% | 28% | 9% |

| The eCare Plan app engages the patient to manage his/her health. | 65% | 23% | 12% |

| The eCare Plan app has increased patient satisfaction with care. | 48% | 43% | 9% |

| Overall, I am satisfied with the eCare Plan app. | 66% | 21% | 14% |

NOTE: “eCare Plan app” = COMPASS-CP.

DISCUSSION

Through COMPASS-CP, we have provided a pragmatic means to systematically assess the multiple factors that influence recovery, health, and independence of post-acute stroke and TIA survivors.5 Further, COMPASS-CP makes these data immediately actionable by using this information to generate individualized electronic care plans at the point of clinical care. There are numerous challenges to implementing PROs into clinical practice,11–13,20 and, to date, few practical solutions to the problem of how to seamlessly achieve the routine collection, electronic integration, application, and communication of PRO data in chronic disease care management.42–45 COMPASS-CP is a feasible tool for overcoming barriers to the efficient and effective implementation of the CMS requirements for care plans, including: (1) improving capture of patient-reported social and functional determinants of health, (2) promoting data-driven decision-making, (3) providing a user-friendly tool to generate a comprehensive care plan at the point of care, (4) creating a care plan that is interpretable and directly actionable, and (5) providing a care plan shared with patients, caregivers, and providers across the continuum of care, regardless of the interoperability of health informatics systems.

COMPASS-CP expands the domains of health beyond those captured with PROMIS, the Neuro-QOL, or instruments recommended by the international consensus panel on stroke outcomes.46,47 COMPASS participants who returned for a transitional care visit report significant challenges and residual deficits within 14 days of stroke. The COMPASS-CP application made this information available, understandable, and immediately actionable through the generation of electronic care plans and a list of relevant local community-based resources so the clinician can help patients and caregivers identify and access needed services. Our results demonstrate that integrating PROs into a web-based application is feasible in the stroke clinical workflow and that provider satisfaction is high. An unsolicited comment from a clinician underscores the value that COMPASS-CP can bring:

“We initiated [COMPASS-CP] today. What a difference it made, we significantly reduced our time from check in to check out. You can’t imagine what a sense of accomplishment that was…. [The patient’s] anxiety was reduced and she trusted our plan of care.”

This study has several limitations. Our study includes only patients whose first language is English or Spanish. For patients that are Spanish-speaking only, an interpreter assists the clinician in administering the questionnaires. In the future, we plan to translate questionnaires into Spanish and other languages. Although all staff members at COMPASS sites were invited to participate in the survey, and 79% did so, a potential limitation of all survey research is volunteer bias, which could impact generalizability. The purpose of this manuscript is not to describe deficits in all stroke/TIA patients discharged home; rather, it is to document that COMPASS-CP processes and methods can successfully document significant residual deficits in those who returned for a clinic visit 7 to 14 days after hospital discharge.

Future Directions

In its current form, COMPASS-CP is an application built on a research platform that is not yet fully integrated into EHRs. Its future scalability and sustainability will require full integration into the EHR. We have selected Substitutable Medical Applications and Reusable Technologies Fast Health Interoperability Resources (SMART on FHIR®) as the architecture for the development of an EHR-integrated application,48 and we are collaborating with health IT vendors to validate the application within their systems. This (SMART on FHIR®) application will ensure that that COMPASS-CP is available to stroke centers of excellence. Further, although the COMPASS-CP application is tailored to meet the complex needs of stroke and TIA patients discharged home, it may be a valuable template for stroke patients discharged to other locations, and those with other complex chronic conditions who require early supported discharge planning and coordination of post-acute services.24

Enrollment in COMPASS ends in spring 2018.23 Thereafter, we will determine if individuals who receive the COMPASS care model and an individualized care plan have improved functional status, the COMPASS study’s primary outcome. We also will compare medication and blood pressure management, reduced readmissions, and improved patient satisfaction among those who were and were not randomized to the COMPASS intervention.23

Conclusions

The COMPASS-CP application supports implementation of CMS’s new value-based payment models and meets an immediate need to incorporate PROs in clinical practice, develop patient-centered care plans, and assist patients and caregivers in accessing needed services. Our analyses of the factors identified in a cohort of mild stroke and TIA patients reveal that patients and caregivers have numerous challenges that hamper patient recovery, health, and independence. Evaluation of the implementation and user satisfaction of COMPASS-CP suggests that PRO-informed care plans are a viable solution to identify and address factors that can limit stroke survivors’ self-management of recovery, health, and independence. Our continued development of the (SMART on FHIR®) application will be the next step to test whether COMPASS-CP is scalable beyond the COMPASS research study.

Supplementary Material

What is Known

Capturing the voice of the patient through patient-reported outcomes (PROs) and immediately incorporating this information into individualized care planning is critical to advancing patient-centered care.

Despite their value in advancing patient-centered care, PROs are still not routinely used stroke management in the US.

What the Study Adds

COMPASS-CP, a clinician-facing application that captures and analyzes PROs in real time, meets an immediate need to incorporate PROs in clinical practice, develop patient-centered care plans, and assist patients and caregivers in accessing needed services.

Integrating PROs into a web-based application is feasible in the stroke clinical workflow, and provider satisfaction with using COMPASS-CP is high.

PRO-informed care plans are a viable solution to identify and address factors that can limit stroke survivors’ self-management of recovery, health, and independence.

Acknowledgments

Ms. Stafford, Dr. D’Agostino, Dr. Psioda, Dr. Jones, and Dr. Duncan had full access to all study data and take responsibility for the integrity and accuracy the data and analyses. All authors take responsibility for the manuscript in its entirety and the data presented herein. We acknowledge the editorial assistance of Karen Klein, MA, in the Wake Forest Clinical and Translational Science Institute (CTSI).

Sources of Funding

This research was funded through Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI; PCS-1403-14532; NCT02588664). Statements presented herein are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of PCORI, its Board of Governors, or Methodology Committee.

We acknowledge support from REDCap and CTSI through the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), National Institutes of Health (UL1TR001420).

Disclosures

Drs. Duncan, Bushnell and D’Agostino and Mr. Rushing are co-founders of CareDirections. Other authors report no conflicts.

Footnotes

Clinical Trial Registration: URL: ClinicalTrials.gov. Unique Identifier: NCT02588664.

REFERENCES

- 1.National Quality Forum. Patient-Reported Outcomes in Performance Measurement. 2012. https://www.qualityforum.org/Publications/2012/12/Patient-Reported_Outcomes_in_Performance_Measurement.aspx. Accessed August 2017.

- 2.US Department of Health and Human Services. Food and Drug Administration Guidance for Industry: Patient-Reported Outcome Measures: Use in Medical Product Development to Support Labeling Claims. 2009. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM193282.pdf. Accessed April 2011.

- 3.Basch E. Patient-Reported Outcomes — Harnessing Patients’ Voices to Improve Clinical Care. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:105–108. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1611252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Speight J, Barendse SM. FDA guidance on patient reported outcomes. Br Med J. 2010;340: c2921. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c2921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Katzan IL, Thompson NR, Uchino K, Lapin B. The most affected health domains after ischemic stroke. Neurology. 2018;0:e1–e8. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000005327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. CMS Quality Strategy 2016. 2016. https://www.cms.gov/medicare/quality-initiatives-patient-assessment-instruments/qualityinitiativesgeninfo/downloads/cms-quality-strategy.pdf. Accessed September 2017.

- 7.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. CMS Quality Measure Development Plan: Supporting the Transition to the Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) and Alternative Payment Models (APMs). 2016. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/Value-BasedPrograms/MACRA-MIPS-and-APMs/MACRA-MIPS-and-APMs.html. Accessed August 2017.

- 8.Havranek EP, Mujahid MS, Barr DA, Blair IV, Cohen MS, Cruz-Flores S, Davey-Smith G, Dennison-Himmelfarb CR, Lauer MS, Lockwood DW, Rosal M, Yancy CW. Social Determinants of Risk and Outcomes for Cardiovascular Disease: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015;132:873–898. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Forman DE, Arena R, Boxer R, Dolansky MA, Eng JJ, Fleg JL, Haykowsky M, Jahangir A, Kaminsky LA, Kitzman DW, Lewis EF, Myers J, Reeves GR, Shen WK. Prioritizing Functional Capacity as a Principal End Point for Therapies Oriented to Older Adults With Cardiovascular Disease: A Scientific Statement for Healthcare Professionals From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017;135:e894–e918. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maddox TM, Albert NM, Borden WB, Curtis LH, Ferguson TB Jr, Kao DP, Marcus GM, Peterson ED, Redberg R, Rumsfeld JS, Shah ND, Tcheng JE. The Learning Healthcare System and Cardiovascular Care: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017;135:e826–e857. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Snyder CF, Aaronson NK, Choucair AK, Elliott TE, Greenhalgh J, Halyard MY, Hess R, Miller DM, Reeve BB, Santana M. Implementing patient-reported outcomes assessment in clinical practice: a review of the options and considerations. Qual Life Res. 2012;21:1305–1314. doi: 10.1007/s11136-011-0054-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schick-Makaroff K, Molzahn AE. Evaluation of real-time use of electronic patient-reported outcome data by nurses with patients in home dialysis clinics. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17:439. doi: 10.1186/s12913-017-2377-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wagle NW. Implementing Patient-Reported Outcome Measures. 2017. http://catalyst.nejm.org/implementing-proms-patient-reported-outcome-measures. Accessed August 2017.

- 14.Gottlieb L, Tobey R, Cantor J, Hessler D, Adler NE. Integrating Social And Medical Data To Improve Population Health: Opportunities And Barriers. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35:2116–2123. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mason D. Health Catalyst. Survey: Fewer Than 2 in 10 Hospitals Regularly Use Patient-Reported Outcomes Despite Medicare’s Impending Plans for the Measures. 2016. https://www.healthcatalyst.com/news/survey-fewer-than-2-in-10-hospitals-regularly-use-patient-reported-outcomes. Accessed August 2017.

- 16.Pakhomov SV, Jacobsen SJ, Chute CG, Roger VL. Agreement between patient-reported symptoms and their documentation in the medical record. Am J Manag Care. 2008;14:530–539. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abernethy AP, Zafar SY, Uronis H, Wheeler JL, Coan A, Rowe K, Shelby RA, Fowler R, Herndon JE 2nd. Validation of the Patient Care Monitor (Version 2.0): a review of system assessment instrument for cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;40:545–558. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang B, Lloyd W, Jahanzeb M, Hassett MJ. Use of patient-reported outcome measures in Quality Oncology Practice Initiative registered practices: Results of a national survey. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:81-81. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.35.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Calvert M, Kyte D, Mercieca-Bebber R, Slade A, Chan AW, King MT; the SPIRIT-PRO Group, Hunn A, Bottomley A, Regnault A, Chan AW, Ells C, O’Connor D, Revicki D, Patrick D, Altman D, Basch E, Velikova G, Price G, Draper H, Blazeby J, Scott J, Coast J, Norquist J, Brown J, Haywood K, Johnson LL, Campbell L, Frank L, von Hildebrand M, Brundage M, Palmer M, Kluetz P, Stephens R, Golub RM, Mitchell S, Groves T. Guidelines for Inclusion of Patient-Reported Outcomes in Clinical Trial Protocols: The SPIRIT-PRO Extension. J Am Med Assoc. 2018;319:483–494. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.21903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu AW. Advances in the Use of Patient Reported Outcome Measures in Electronic Health Records. 2013. http://www.pcori.org/assets/2013/11/PCORI-PRO-Workshop-EHR-Landscape-Review-111913.pdf. Accessed August 2017.

- 21.Baumhauer JF, Dasilva C, Mitten D, Rubery P, Michael Rotondo M. N Engl J Med Catalyst. 2018. https://catalyst.nejm.org/cost-pro-collection-patient-reported-outcomes/ Accessed February 2018.

- 22.Lavallee DC, Chenok KE, Love RM, Petersen C, Holve E, Segal CD, Franklin PD. Incorporating Patient-Reported Outcomes Into Health Care To Engage Patients And Enhance Care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35:575–582. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Duncan PW, Bushnell CD, Rosamond WD, Jones Berkeley SB, Gesell SB, D’Agostino RB Jr, Ambrosius WT, Barton-Percival B, Bettger JP, Coleman SW, Cummings DM, Freburger JK, Halladay J, Johnson AM, Kucharska-Newton AM, Lundy-Lamm G, Lutz BJ, Mettam LH, Pastva AM, Sissine ME, Vetter B. The Comprehensive Post-Acute Stroke Services (COMPASS) study: design and methods for a cluster-randomized pragmatic trial. BMC Neurol. 2017;17:133. doi: 10.1186/s12883-017-0907-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bushnell CD, Duncan PW, Lycan S, Condon C, Pastva AM, Lutz BJ, Halladay J, Cummings DM, Arnan MK, Jones SB, Sissine ME, Coleman SW, Johnson AM, Gesell SB, Mettam LH, Freburger J, Barton-Percival B, Taylor KM, Prvu-Bettger J, Lundy-Lamm G, Rosamond WD. A Patient-Centered Approach to Post-Stroke Care: The COMprehensive Post-Acute Stroke Services (COMPASS) Model. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Broderick JP, Abir M. Transitions of Care for Stroke Patients: Opportunities to Improve Outcomes. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2015;8:S190–2. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.115.002288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Olson DM, Bettger JP, Alexander KP, Kendrick AS, Irvine JR, Wing L, Coeytaux RR, Dolor RJ, Duncan PW, Graffagnino C. Transition of care for acute stroke and myocardial infarction patients: from hospitalization to rehabilitation, recovery, and secondary prevention. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep). 2011;202:1–197. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abubakar SA. Isezuo SA. Health Related Quality of Life of Stroke Survivors: Experience of a Stroke Unit. Int J Biomed Sci. 2012;8:183–187. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lutz BJ, Young ME, Creasy KR, Martz C, Eisenbrandt L, Brunny JN, Cook C. Improving Stroke Caregiver Readiness for Transition From Inpatient Rehabilitation to Home. Gerontologist. 2017;57:880–889. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnw135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bakas T, Clark PC, Kelly-Hayes M, King RB, Lutz BJ, Miller EL. Evidence for stroke family caregiver and dyad interventions: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association and American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2014;45:2836–2852. doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nordin A, Sunnerhagen KS, Axelsson AB. Patients’ expectations of coming home with Very Early Supported Discharge and home rehabilitation after stroke - an interview study. BMC Neurol. 2015;15:235. doi: 10.1186/s12883-015-0492-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Deplanque D, Bastide M, Bordet R.Transient Ischemic Attack and Minor Stroke: Definitively Not So Harmless for the Brain and Cognitive Functions. Stroke. 2018;49:277–278. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.117.020013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bivard A, Lillicrap T, Maréchal B, Garcia-Esperon C, Holliday E, Krishnamurthy V, Levi CR, Parsons M. Transient Ischemic Attack Results in Delayed Brain Atrophy and Cognitive Decline. Stroke. 2018;49:384–390. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.117.019276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hodson T, Gustafsson L, Cornwell P, Love A. Post-acute hospital healthcare services for people with mild stroke: a scoping review. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2017;24:288–298. doi: 10.1080/10749357.2016.1267831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Allen KR, Hazelett S, Jarjoura D, Wickstrom GC, Hua K, Weinhardt J, Wright K. Effectiveness of a postdischarge care management model for stroke and transient ischemic attack: a randomized trial. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2002;11:88–98. doi: 10.1053/jscd.2002.127106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Andrews JE, Moore JB, Weinberg RB, Sissine M, Gesell S, Halladay J, Rosamond W, Bushnell C, Jones S, Means P, King NMP, Omoyeni D, Duncan PW; COMPASS investigators and stakeholders. Ensuring respect for persons in COMPASS: a cluster randomised pragmatic clinical trial. J Med Ethics. 2018. pii: medethics-2017–104478. doi: 10.1136/medethics-2017-104478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. Data Access and Data Sharing Policy: Public Comment. 2017. https://www.pcori.org/get-involved/provide-input/data-access-and-data-sharing-policy-public-comment. Accessed May 2011.

- 37.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Transitional Care Management Services. March 2016. https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNProducts/Downloads/Transitional-Care-Management-Services-Fact-Sheet-ICN908628.pdf. Accessed April 2018.

- 38.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Chronic Care Management Services. 2015. https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNProducts/Downloads/ChronicCareManagement.pdf. Accessed April 2018.

- 39.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. MACRA. 2018. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/Value-Based-Programs/MACRA-MIPS-and-APMs/MACRA-MIPS-and-APMs.html. Accessed April 2018.

- 40.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Comprehensive Primary Care Plus (CPC+) Fact Sheet. 2016. https://www.cms.gov/Newsroom/MediaReleaseDatabase/Fact-sheets/2016-Fact-sheets-items/2016-04-11.html. Accessed April 2018.

- 41.Adler NE, Stead WW. Patients in context—EHR capture of social and behavioral determinants of health. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:698–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wu AW, Kharrazi H, Boulware LE, Snyder CF. Measure once, cut twice — adding patient-reported outcome measures to the electronic health record for comparative effectiveness research. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;66:S12–S20. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Health Measures. PROMIS. 2017. http://www.nihpromis.org Accessed April 2017.

- 44.International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement. 2017. http://www.ichom.org/. Accessed April 2017.

- 45.Bradley S, Rumsfeld J, Ho P. Incorporating health status in routine care to improve health care value: the VA Patient Reported Health Status Assessment (PROST) System. J Am Med Assoc. 2016;316:487–488. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.6495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Salinas J, Sprinkhuizen SM, Ackerson T, Bernhardt J, Davie C, George MG, Gething S, Kelly AG, Lindsay P, Liu L, Martins SC, Morgan L, Norrving B, Ribbers GM, Silver FL, Smith EE1, Williams LS, Schwamm LH. An International Standard Set of Patient-Centered Outcome Measures After Stroke. Stroke. 2016;47:180–186. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.010898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cella D, Lai JS, Nowinski CJ, Victorson D, Peterman A, Miller D, Bethoux F, Heinemann A, Rubin S, Cavazos JE, Reder AT, Sufit R, Simuni T, Holmes GL, Siderowf A, Wojna V, Bode R, McKinney N, Podrabsky T, Wortman K, Choi S, Gershon R, Rothrock N, Moy C. Neuro-QOL: brief measures of health-related quality of life for clinical research in neurology. Neurology. 2012;78:1860–1867. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318258f744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mandel JC, Kreda DA, Mandl KD, Kohane IS, Ramoni RB. SMART on FHIR: a standards-based, interoperable apps platform for electronic health records. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2016;23:899–908. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocv189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.