Abstract

Background:

Fatal overdoses involving cocaine (powdered or crack) and fentanyl have increased nationally and in Massachusetts. It is unclear how overdose risk and preparedness to respond to an overdose differs by patterns of cocaine and opioid use.

Methods:

From 2017 to 2019, we conducted a nine-community mixed-methods study of Massachusetts residents who use drugs. Using survey data from 465 participants with past-month cocaine and/or opioid use, we examined global differences (p < 0.05) in overdose risk and response preparedness by patterns of cocaine and opioid use. Qualitative interviews (n = 172) contextualized survey findings.

Results:

The majority of the sample (66%) used cocaine and opioids in the past month; 18.9% used opioids alone; 9.2% used cocaine and had no opioid use history; and 6.2% used cocaine and had an opioid use history. Relative to those with a current/past history of opioid use, significantly fewer of those with no opioid use history were aware of fentanyl in the drug supply, carried naloxone, and had received naloxone training. Qualitative interviews documented how people who use cocaine and have no history of opioid use are largely unprepared to recognize and respond to an overdose.

Conclusions:

Public health efforts are needed to increase fentanyl awareness and overdose prevention preparedness among people primarily using cocaine.

Keywords: Substance use, opioids, cocaine, crack, overdose

Introduction

Recent mortality data in Massachusetts (MA) and other overdose hotspots show an increase in fatal overdoses involving synthetic opioids and cocaine (powdered or crack).1-5 These overdose deaths are largely driven by fentanyl, which has proliferated the drug market,1,6-9 and is highly lethal in small doses.10 Indeed, starting in 2014 through 2017, fatal overdose data from MA shows that the percentage of death involving heroin, prescription opioids, and benzodiazepines has decreased, whereas the percentage of deaths involving cocaine and fentanyl have steadily increased (2014: fentanyl: 42%; heroin: ~64%; prescription opioids: ~27%; cocaine: ~32%; benzodiazepines: ~65%; 2017: fentanyl: 81%; heroin: 39%; prescription opioids: 15%; cocaine: 42%; benzodiazepines: 57%).4 While medical and non-medical use of benzodiazepines is common among individuals with opioid use disorder,11,12 the increase in postmortem toxicology reports involving both fentanyl and cocaine in particular raise questions about how fentanyl and cocaine are being used and whether people who use drugs are aware of fentanyl in the drug supply.13-15

While valuable, postmortem toxicology data do not provide information on how deceased individuals use drugs and whether their consumption of one or more drugs was intentional.13 Research on the intentional, concurrent use of cocaine and heroin8 finds that many individuals combine cocaine and heroin simultaneously or sequentially.16-18 Indeed, people who use “speedballs” combine cocaine and opioids in a single injection.19 Some individuals may also use cocaine and opioids at different times of the day.16,17 Other people, however, exclusively use opioids or exclusively use cocaine.16,20 While these documented patterns of heroin and cocaine use are informative, they do not speak to how individuals consume fentanyl (i.e. through purposeful use vs. unintentional consumption). Given the impossibility of surveying and interviewing deceased individuals about their intended or unintentional use of fentanyl and cocaine prior to overdosing, it is important to conduct research with people with variable patterns of cocaine and/or opioid use to understand the mechanisms through which fentanyl is consumed and may increase the risk for fatal and nonfatal overdose.

While co-use of substances may be intentional, the cooccurrence of cocaine and fentanyl in the drug supply is increasing and may result in unintentional use.21-28 Indeed, drug seizure data and surveillance research find that cocaine is being intentionally cut with and/or accidentally adulterated with fentanyl resulting in the unintentional consumption of fentanyl.7,9,27 Studies have documented that communities of people who primarily use heroin are highly aware of fentanyl contamination in the heroin supply and have community standards and practices in place to prevent fatal overdoses.29 Limited evidence, on the other hand, suggests that people who do not use opioids or who use opioids other than heroin, such as prescription pain pills, are less informed about overdose risks;30 no research to our knowledge has documented awareness of fentanyl contamination and perceived risk of opioid overdose as a result of contamination.

Also understudied is the extent to which individuals who primarily use cocaine are prepared to respond to an opioid overdose, which is an important line of inquiry in light of increasing contamination of fentanyl in the cocaine supply. To that end, the prevention of fatal opioid-related overdoses requires that those witnessing an overdose know how to recognize and respond to an overdose event. Moreover, once a bystander recognizes that a person is overdosing, they must act quickly to prevent it from turning fatal.31 The best available tool to prevent a fatal overdose is to administer the opioid-overdose reversal drug naloxone (brand name Narcan). While the widespread availability of naloxone can reduce fatal overdoses, naloxone is only effective if people are aware of it, have it on them or can quickly acquire it, and know how to administer it within a time window where it can be effective.32,33 Compared to people who exclusively use cocaine, individuals with a history of opioid use may be better able to recognize an opioid-involved overdose as they are likely to have witnessed or personally experienced an overdose.34,35 Research also finds high levels of naloxone awareness and moderate levels of training among people who use opioids,36,37 but access to naloxone can vary widely according to geographic location, legal restrictions, and implementation model.37-39 However, no research, to our knowledge has explored naloxone awareness, use, and accessibility among people who use cocaine and have no history of opioid use.

Given the gaps in the extant literature, the current study sought to use quantitative and qualitative methods to examine overdose risk and preparedness to respond to an overdose among people who use cocaine and have no history of opioid use relative to those with an opioid use history. Findings from this study can inform overdose prevention efforts to reduce the incidence of overdose among people who use cocaine and other drugs.

Method

Between August 2017 and November 2019, we conducted a mixed-methods rapid assessment of consumer knowledge with 469 people who use drugs in Massachusetts. Individuals were eligible for the study if they were 18 years of age or older; a resident of Massachusetts; and reported using an illicit drug in the past 30 days. Individuals who used marijuana or alcohol alone were not eligible as both are legal in the state of Massachusetts. Individuals who did not report cocaine or opioid use in the past 30 days were excluded from this analysis.

Recruitment

We examined fatal overdose death trends from 2015 through 2017 using the Massachusetts State Unintentional Drug Overdose Reporting System (SUDORS).40 We then selected 9 communities comprised of the 15 cities with the highest rates of overdose deaths in 2016: Lowell; Lawrence; Quincy; Upper- and Mid-Cape Cod (Barnstable, Mashpee, Yarmouth, Falmouth); Springfield; Chicopee; Worcester; the North Shore (Lynn, Salem, Beverly, Peabody); and New Bedford. In preparation for recruitment, we conducted environmental scans comprised of a review of publicly-available public health and surveillance data, community walk-throughs, and meetings with community partners to identify locations for participant recruitment. Recruitment strategies varied by study location though all strategies employed targeted sampling to recruit participants from areas of high drug use, arrest, and overdose. In Lowell, Lawrence, Quincy, Cape Cod, Springfield, Chicopee, Worcester, and the North Shore, we used purposive sampling methods.41,42 Based on concerns about rising stimulant and opioid-involved overdose rates, we oversampled people who use cocaine across all study locations. In New Bedford, we piloted the use of respondent driven sampling (RDS) to augment recruitment43 and assess the feasibility of this method to recruit people who use drugs. For both approaches, we partnered with local organizations (e.g. syringe services programs (SSPs), homeless shelters, community health centers) to facilitate the recruitment of potential participants.

For purposive sampling, we relied on the direct referral of participants from community partners. We also posted flyers online and handed out and posted flyers at community organizations, in public spaces, and in neighborhoods where people who use drugs spend time (as determined via community consultations, overdose death reports, and police arrest data). Snowball sampling strategies were also utilized. Participants received $5 for up to three people whom they referred and who were eligible and enrolled in the study.

For RDS recruitment in New Bedford, we identified “seed” participants who we believed had large social networks or belonged to key subpopulations of people who use drugs in New Bedford (e.g. transactional sex workers, fishermen/anglers, people who use cocaine). We surveyed seed participants and then gave them three time-limited referral coupons for eligible “sprout” participants. Eligible sprouts who returned their referral coupon were subsequently enrolled and completed data collection. Sprout participants then received three coupons to refer new sprouts. Participants who successfully recruited others were compensated with a $5 gift card per eligible recruit (up to three per person).

Data collection

Individuals identified by either purposive sampling or RDS were screened for eligibility by phone or in person. Verbal informed consent was obtained from all participants before initiating study procedures. All participants completed a onetime, approximately 45-minute, interviewer-administered survey on an electronic tablet computer or on paper. The survey assessed participants’ patterns of substance use, history of personally-experienced and witnessed overdoses, and access to harm reduction tools and services (e.g. naloxone, naloxone training). Following the survey, approximately a third of participants (n = 172) completed an in-depth qualitative interview covering the same topics that were assessed in the survey. Participants were offered an interview if they demonstrated (via their survey responses) a willingness to discuss their substance use history and related experiences and/or they reported unique or extensive drug use patterns, experiences of witnessed or personal overdose, experiences accessing harm reduction and treatment services, or other self-reported data that would enable the researchers to better contextualize the risk and protective factors for overdose beyond the data provided by the survey. The interviews were audio-recorded and took approximately 45 minutes to complete. The majority of surveys and interviews were conducted in English; a subset was conducted in Spanish. Participants received a $20 gift card for each portion of the visit that they completed (i.e. survey and interview). The study was approved by the Boston Medical Center Institutional Review Board.

Measures

Socio-demographics

Age was assessed categorically and collapsed into a binary variable of 18 to 40 years of age vs. 41 years of age or more. Gender categories included male, female, or another gender. Race and Hispanic ethnicity were assessed independently and combined to create the following racial/ethnic categories: White, non-Hispanic; Black, non-Hispanic; Native American, non-Hispanic; Hispanic; more than one race/ethnicity; and another race/ethnicity. Educational attainment was assessed and categorized as some high school or less; high school graduate or GED; and some college or more. Participants were asked what they do to make money; openended responses were coded as being employed for wages vs. unemployed. Housing status was assessed by asking participants to indicate where they were living. Responses were categorized as house or apartment; shelter or rooming home; halfway house/sober home; on the street; and other.

Substance use

Participants were asked to report the types of substances they had used in the past 30 days (powdered cocaine, crack cocaine, heroin, fentanyl, opioid pain medication, methamphetamine, benzodiazepine, marijuana). Participants were also asked (via the survey and interviews) about their prior intentional use of fentanyl, heroin, and opioid pain medications (prescribed and not-prescribed) as well as their lifetime prescribed and non-prescribed use of medications for opioid use disorder (i.e. buprenorphine, methadone, naltrexone). Participants who reported using fentanyl, heroin, opioid pain medication, or medications for opioid use disorder were coded as having a history of lifetime opioid use (yes vs. no).

Participants were then categorized into four groups according to current use of cocaine or opioids and their lifetime history of opioid use. Participants reporting the use of powdered cocaine in the past 30 days were stratified according to their lifetime history of opioid use and coded as 1) cocaine use without a history of opioid use; or 2) cocaine use with a history of opioid use. Individuals who reported using opioids and no cocaine in the past 30 days were coded as 3) opioid use only; and those who reported using both opioids and cocaine were coded as 4) cocaine and opioid use.

Awareness of fentanyl in drug supply

Several variables assessed participants’ awareness of fentanyl in the drug supply. Participants were first asked to indicate if they had heard of fentanyl (yes vs. no/don’t know). Participants were also asked to report whether they had used or suspected that they had used drugs containing fentanyl in the past year (yes vs. no/don’t know); those reporting yes were asked whether they knew fentanyl was in their drugs before using them. Participants who reported knowingly using fentanyl were asked to report their basis for knowing; response options, which were check all that apply, included: using a fentanyl test strip; overdosed quickly; someone else overdosed on the drug; bought online as fentanyl; dealer said drug was fentanyl or contained fentanyl; feel, color, taste; or another reason (e.g. testing positive for fentanyl via urine toxicology testing, and the assumption that fentanyl is “in everything” these days). Participants were also asked to indicate if they were looking to intentionally buy fentanyl in the past year (yes vs. no); those that responded “no” were asked what substance they had intended to buy (heroin, powdered cocaine, crack cocaine, something else).

Knowledge to identify and respond to overdose risk

Several variables were used as proxies for the likelihood of knowing how to recognize an opioid overdose. Specifically, participants were asked to indicate whether they had ever personally experienced an overdose (yes vs. no) or witnessed someone else overdosing (yes vs. no). Participants who had experienced or witnessed an overdose were asked to indicate whether they knew or suspected that fentanyl was involved in the last overdose and their reason for suspecting fentanyl involvement. Participants could check all that apply to the reasons for suspected fentanyl-involved overdose which included: personally overdosed quickly; someone else overdosed quickly; feel, color, taste; used a fentanyl test strip; dealer said fentanyl was involved; or another reason (e.g. person was looking to buy fentanyl; fentanyl showed up in drug test; word of mouth; assumption that fentanyl was in everything).

Prepared to respond to an overdose

Preparedness to respond to an overdose was assessed by first asking participants whether they had ever heard about naloxone (yes vs. no/don’t know). Participants were also asked if they had a personal naloxone kit on them or at the place where they use drugs (yes vs. no) and whether they had been trained to use naloxone (yes vs. no). Those reporting receipt of naloxone training were asked how they learned about/were trained to use naloxone with check all that apply response options including: community organization; friend or family member; in treatment; doctor, pharmacist or another provider; syringe services program; jail/prison; self-taught; or another method. Participants were also asked whether 911 was called at the last overdose that they had witnessed (yes vs. no/don’t know), whether naloxone was administered (yes vs. no/don’t know); and if yes whether the participant personally administered naloxone or whether it was administered by someone else.

Data analysis

The analysis was restricted to individuals who utilized cocaine and/or opioids resulting in an analytic sample of N = 465. Descriptive statistics (means and frequencies) were calculated for all study variables. Chi-Square (X2) and Fisher Exact tests assessed global differences in overdose indicators by pattern of cocaine/opioid use. Significance was determined at p < 0.05. All quantitative analyses were conducted in SAS 9.4.

Qualitative interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim by a professional transcription service. The transcripts were entered into NVivo, a qualitative data analysis program, and subsequently analyzed using an inductive and deductive approach. In preparation for the analysis, an initial codebook was created using the key thematic areas contained in the interview guide including (e.g. fentanyl in the drug supply, witnessed an overdose, naloxone use and training). The interview transcripts were then reviewed and open coded for emerging themes and subthemes. Through a series of team meetings and ongoing transcript review, emerging themes were integrated into the codebook. Using NVivo software, two trained research assistants with expertise in qualitative coding coded the transcripts using a rapid, first cycle coding approach.44 A total of 25% of transcripts were double-coded to ensure consistency in coding application. The coders met weekly with the first author to review the application of the codes and revise the codebook, code definitions, and coding application as necessary. After completing the initial qualitative rapid coding process, the first author applied a second layer of codes pertinent to the present quantitative analysis (i.e. fentanyl in the drug supply, overdose response preparedness by substance use history). The coded transcripts were then used to contextualize the findings of the quantitative analysis. Pseudonyms are used throughout the results to protect participant confidentiality.

Results

Socio-demographics

Among the 465 participants in the analytic sample, the majority were between the ages of 18 and 40 (63.6%), male (61.3%), and White, non-Hispanic (59.6%) (Table 1). Nearly three-quarters of the sample had obtained a high school degree/GED or less (73.7%) and 60.1% of the sample was unemployed. About two-fifths of participants (40.9%) reported living in a house or apartment; 32.5% of the sample reported living on the street, and 19.8% reported living in a shelter or rooming house.

Table 1.

Characteristics of People Who Use Drugs in Massachusetts by Current Substance Use, 2017–2019.

| Total N = 465 |

Current cocaine use - no opioid use history N = 37 |

Current cocaine use - opioid use history N = 35 |

Current opioid use N = 88 |

Current cocaine and opioid use N = 305 |

Test statistic | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | p-Value | |

| Age | n = 464 | n = 36 | n = 35 | n = 88 | n = 305 | |

| 18–40 | 295 (63.6) | 19 (52.8) | 19 (54.3) | 48 (54.5) | 209 (68.5) | 9.4 (df = 3) |

| 41 and older | 169 (36.4) | 17 (47.2) | 16 (45.7) | 40 (45.5) | 96 (31.5) | 0.02 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 176 (37.8) | 8 (21.6) | 14 (40) | 32 (36.4) | 122 (40) | Fisher |

| Male | 285 (61.3) | 29 (78.4) | 21 (60) | 55 (62.5) | 180 (59) | 0.38 |

| Another gender | 4 (0.9) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.1) | 3 (1) | |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 277 (59.6) | 17 (45.9) | 20 (57.1) | 61 (69.3) | 179 (58.7) | Fisher |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 35 (7.5) | 7 (18.9) | 1 (2.9) | 3 (3.4) | 24 (7.9) | 0.18 |

| Native American, non-Hispanic | 9 (1.9) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.9) | 2 (2.3) | 6 (2) | |

| Another race/ethnicity, non-Hispanic | 3 (0.6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (1) | |

| Hispanic | 124 (26.7) | 12 (32.4) | 12 (34.3) | 21 (23.9) | 79 (25.9) | |

| More than one race, non-Hispanic | 17 (3.7) | 1 (2.7) | 1 (2.9) | 1 (1.1) | 14 (4.6) | |

| Educational attainment | n = 464 | n = 37 | n = 34 | n = 88 | n = 305 | |

| Some high school/GED or less | 133 (28.7) | 13 (48.1) | 6 (17.6) | 22 (25) | 92 (30.2) | 3.9 (df = 6) |

| High school graduate or GED | 209 (45) | 16 (59.3) | 18 (52.9) | 41 (46.6) | 134 (43.9) | 0.70 |

| Some college or more | 122 (26.3) | 8 (29.6) | 10 (29.4) | 25 (28.4) | 79 (25.9) | |

| Employment for wages | n = 464 | n = 36 | n = 35 | n = 88 | n = 305 | |

| No | 279 (60.1) | 24 (66.7) | 27 (77.1) | 46 (52.3) | 182 (59.7) | 7.16 (df = 3) |

| Yes | 185 (39.9) | 12 (33.3) | 8 (22.9) | 42 (47.7) | 123 (40.3) | 0.07 |

| Housed | ||||||

| House or apartment | 190 (40.9) | 15 (40.5) | 17 (48.6) | 43 (48.9) | 115 (37.7) | Fisher |

| Halfway house/sober home | 25 (5.4) | 1 (2.7) | 1 (2.9) | 12 (13.6) | 11 (3.6) | <.0001 |

| Shelter or rooming house | 92 (19.8) | 9 (24.3) | 8 (22.9) | 18 (20.5) | 57 (18.7) | |

| On the street | 151 (32.5) | 9 (24.3) | 9 (25.7) | 15 (17.0) | 118 (38.7) | |

| Other | 7 (1.5) | 3 (8.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (1.3) | |

| Intentional substance use - past 30 days | ||||||

| Powdered cocaine | 305 (65.6) | 21 (56.8) | 28 (80) | 0 (0) | 256 (83.9) | <.0001 |

| Crack cocaine | 280 (60.2) | 25 (67.6) | 25 (71.4) | 0 (0) | 226 (74.1) | <.0001 |

| Heroin | 320 (68.8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 63 (71.6) | 257 (84.3) | <.0001 |

| Fentanyl | 296 (63.7) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 61 (69.3) | 235 (77.0) | <.0001 |

| Opioid pain medication* | 155 (33.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 30 (34.1) | 125 (41.0) | <.0001 |

| Methamphetamine (n = 367)** | 42 (9) | 2 (5.4) | 3 (8.6) | 1 (1.1) | 36 (11.8) | <.0001 |

| Benzodiazepines*** | 125 (27.1) | 2 (5.4) | 10 (28.6) | 26 (29.6) | 88 (28.9) | 0.009 |

| Marijuana**** | 200 (43.0) | 23 (62.2) | 14 (40.0) | 29 (33.0) | 134 (43.9) | 9.40 (df = 3) 0.02 |

Note. Test-statistic is based on a chi-square test. Fisher’s exact tests were used when cell count was <5; only p-values are reported for Fisher’s Exact. DF: degrees of freedom. Bolded p-value = significant at p < 0.05.

Opioid pain medication includes both prescribed and non-prescribed medication. Notably, 80% of those who used opioid pain medication had a current (80%) or past (20%) history of illicit fentanyl or heroin use.

Methamphetamine use was not assessed in 2 sites; thus 97 people were not included; 1 additional person had missing data.

Includes prescribed and unprescribed use of benzodiazepines.

Includes medical and recreational marijuana use.

Substance use history

The majority of the sample reported using cocaine and opioids in the past 30 days (65.6%) and 18.9% reported only using opioids and no cocaine. A total of 7.5% of the sample reported using cocaine in the past 30 days and had a history of opioid use and 8.0% of the sample reported using cocaine in the past 30 days and did not have a history of opioid use. Significantly more of the participants who reported concurrent cocaine and opioid use were in the younger age group (18–40 years of age), relative to participants in other drug use groups (p = 0.02). Participants who used both cocaine and opioids had the highest percentage of unstable housing with 37.4% reporting living on the street and 18.7% living in a shelter (p = 0.001).

With regard to other substances, use of both prescribed and unprescribed benzodiazepines was high among the full sample (27.1%), with those with a past (28.6%) or current history of opioid use (28.9–29.6%) having the highest observed past 30-day use and those who use cocaine and have no history of opioid use having the lowest reported use of benzodiazepines (5.4%; p = 0.009). Marijuana was also highly prevalent (40.0%) among the full sample, with the highest reported past 30-day use reported by those who use cocaine and have no history of opioid use (62.2%) and the lowest reported use among those who use opioids and not cocaine (33.0%; p < 0.02).

Opioid overdose risk and overdose response preparedness

Awareness of fentanyl in the drug supply

The vast majority of the sample (96.8%) had heard of fentanyl. Significant differences were observed by cocaine and opioid use history, with the greatest level of fentanyl awareness reported among those who had used both cocaine and opioids in the past 30 days (98.4%), followed by cocaine with opioid use history (97.1%), opioids only (96.6%), and cocaine with no opioid use history (83.8%); p = 0.0001. More than three-quarters of the sample (76.1%) reported that they knew or suspected fentanyl was in their drugs in the past year, with significant differences observed according to drug use history. Specifically, only 5.4% of those who used cocaine in the past 30 days and did not have an opioid use history indicated that they suspected that fentanyl was in their drugs, compared to 41.2% of those who used cocaine in the past 30 days and had an opioid use history; 80.0% of those who only used opioids; and 87.5% of those who used cocaine and opioids in the past 30 days (p < 0.0001). The most commonly reported reason for knowing or suspecting that fentanyl was in the drug supply was some aspect of the feel, color, or taste of drugs (71.7%), followed by being told by a dealer (21.9%), testing positive for fentanyl in a urinalysis (8.0%), and the perception that fentanyl is in everything these days (8.0%).

Among the 284 participants who were asked whether they were intentionally looking to buy fentanyl, more than a quarter (26.6%) indicated that they had intentionally bought fentanyl, with the highest prevalence reported by individuals who currently use opioids and do not use cocaine (30.0%) and the lowest reported prevalence among those who use cocaine but have a history of past opioid use (18.2%; p < 0.01). Among the 172 people who were not looking to buy fentanyl and were asked about what they had intended to buy, 89% had intended to buy heroin (95.5% currently use opioids; 90.7% currently use cocaine and opioids; 62.5% currently use cocaine and have an opioid use history). The remaining participants had intended to buy cocaine (7.0%) or something else (4.1%).

Our qualitative findings supported the quantitative findings, indicating that individuals without a history of opioid use tended to be unaware of fentanyl in the drug supply. While most participants without an opioid use history had heard of fentanyl, they associated fentanyl with heroin. For example, one participant noted:

No. I didn’t know what [fentanyl] was. I’ve heard of it. But I never think about it….’Cause I thought it was only something they were doing to that stuff, to the heroin….I didn’t know…I’ve never heard of it.

– Kiara, uses cocaine, no opioid use history

A subset of participants who were not actively using opioids was aware of the potential for fentanyl to be in the drug supply and had learned about it through word of mouth. For example, one participant described learning that there may be fentanyl in the cocaine supply after someone in her apartment building had a bad experience with cocaine that they believed to be laced with fentanyl:

From what I’m hearing [there may be fentanyl in the cocaine]. I heard from somebody tonight that lives in my building. [His friend] bought a bad batch. Like it wasn’t right. Like there’s something else in the cocaine. That’s what he told me. He said [his friend] had a bad experience last Friday, so that scared me. And he was scared it might happen to him.

– Kathy, uses cocaine, no opioid use history

Consistent with the quantitative findings, participants with a current or past history of opioid use described learning about fentanyl in the drug supply when they or someone they knew tested positive for fentanyl during the course of routine urine testing but had not intentionally used fentanyl. For example, Shandra described receiving the results of a mandatory drug test, noting, “My tox screen came back positive for [fentanyl] and I haven’t done any heroin …The only result is that it would be in the crack I smoked.” Participants who tested positive for fentanyl often did so in the context of substance use treatment programs. Substance use treatment programs also served as another means through which participants learned about fentanyl and several participants reported that treatment programs provided education on overdose risk and informed patients about emerging trends like fentanyl pervasiveness and contamination of the drug supply. For example, Lani, who used cocaine and was in treatment for opioids, noted, “[I learned about fentanyl in the drug supply] at a methadone clinic. We’re like first educated on everything.”

The other pathway through which participants believed that fentanyl was in the drugs they used was through the perception of fentanyl saturating the local drug supply. These perceptions were most often voiced by people who reported intentionally using opioids and cocaine. For example, Jess, who had recently used both opioids and cocaine, said, “Yeah, I mean, [I suspect fentanyl is in the drug supply]. I guess they put it in everything now.” Another participant acknowledged the ubiquitous nature of fentanyl in the drug supply and noted the harms that fentanyl-contaminated cocaine could cause for unsuspecting individuals:

Oh yeah, the people are putting fentanyl in cocaine and fentanyl in benzos. Making fake pills, fake Percocets, fake Xanax bars and stuff with fentanyl in them….[My friend] was livid that this [dealer] was putting opiates inside cocaine when it does the opposite. You know, and like, fentanyl is not something we joked with. You know, if you’re opiate naïve and you don’t have a tolerance to opiates, and …you take a bump of cocaine that’s got fentanyl in it, chance of overdose is incredible.

– Brian, uses cocaine and opioids

Knowing how to recognize an overdose

As shown in Table 2, 89.8% of the sample had witnessed an overdose before, with a significantly higher proportion of those with a past (94.3%) or current history of opioid use (opioids only: 90.9%; cocaine and opioids: 90.4%) reporting having witnessed an overdose compared to those without an opioid use history (78.4%; p<.0001). Additionally, 63.0% of the sample reported having personally overdosed, with the highest proportion of overdose experiences (68.9%) reported among those who had used both cocaine and opioids in the past 30 days and the lowest (21.6%) observed among those who had only used cocaine and did not have a history opioid use (p<.0001). Among those who had overdosed, 75.8% indicated that they knew or suspected fentanyl to be involved, with only 37.5% of those who had only used cocaine and did not have a history of opioid use reporting a suspicion of fentanyl involvement compared to 79.1% of those who had used both cocaine and opioids in the past 30 days (p = 0.004). The most commonly reported reason for suspecting that fentanyl was involved in one’s last overdose was something to do with the feel, color, or taste of the drug (43.0%), followed by having overdosed quickly after taking the drug (36.3%).

Table 2.

Overdose Risk Profiles by Substance Use Behaviors in a Sample of Massachusetts Residents Who Use Drugs, 2017–2019.

| Awareness of fentanyl in drug supply | Total |

Current cocaine use – no opioid use history |

Current cocaine use – opioid use history |

Current opioid use |

Current cocaine and opioid use |

Test statistic p-Value |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

N = 465 |

N = 37 |

N = 35 |

N = 88 |

N = 305 |

|||||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | ||

| Fentanyl awareness | |||||||||||

| No/Don’t know | 15 | 3.2 | 6 | 16.2 | 1 | 2.9 | 3 | 3.4 | 5 | 1.6 | |

| Yes | 450 | 96.8 | 31 | 83.8 | 34 | 97.1 | 85 | 96.6 | 300 | 98.4 | 0.001 |

| Know/Suspect fentanyl in drugs – past 12 months | n = 460 | n = 37 | n = 34 | n = 85 | n = 304 | ||||||

| No/Don’t Know | 110 | 23.9 | 35 | 94.6 | 20 | 58.8 | 17 | 20.0 | 38 | 12.5 | |

| Yes | 350 | 76.1 | 2 | 5.4 | 14 | 41.2 | 68 | 80.0 | 266 | 87.5 | <.0001 |

| Reason for knowing/Suspecting fentanyl in drugs | n = 251 | n = 2 | n = 9 | n = 47 | n = 193 | ||||||

| Fentanyl test strip | 7 | 2.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2.1 | 6 | 3.1 | |

| Overdosed quickly | 19 | 7.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 6.4 | 16 | 8.3 | |

| Someone else overdosed | 12 | 4.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 11.1 | 3 | 6.4 | 8 | 4.1 | |

| Bought online as fentanyl | 2 | 0.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 11.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.5 | |

| Dealer said so | 55 | 21.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 22.2 | 9 | 19.1 | 44 | 22.8 | |

| Feel, color, taste | 180 | 71.7 | 1 | 50.0 | 7 | 77.8 | 29 | 61.7 | 143 | 74.1 | |

| Another reason | 49 | 19.5 | 1 | 50.0 | 2 | 22.2 | 13 | 27.7 | 33 | 17.1 | |

| Tested positive for it during mandatory urine drug testing | 20 | 8.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 50 | 4 | 30.8 | 15 | 7.8 | |

| It is in everything/fentanyl saturation in local drug supply | 20 | 8.0 | 1 | 100.0 | 1 | 50 | 3 | 23.1 | 15 | 100.0 | |

| Word of mouth | 5 | 2.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 23.1 | 2 | 13.3 | |

| Another reason* | 4 | 1.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 15.4 | 2 | 13.3 | |

| Looking to intentionally buy fentanyl | n = 284 | n = 2 | n = 11 | n = 50 | n = 220 | ||||||

| Yes | 75 | 26.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 18.2 | 15 | 30.0 | 58 | 26.4 | |

| No | 209 | 73.6 | 2 | 66.7 | 10 | 90.9 | 35 | 70.0 | 162 | 73.6 | 0.01 |

| Intended to buy…** | n = 172 | n = 2 | n = 8 | n = 22 | n = 140 | ||||||

| Heroin | 153 | 89.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 5 | 62.5 | 21 | 95.5 | 127 | 90.7 | |

| Powdered cocaine | 7 | 4.1 | 1 | 50.0 | 1 | 12.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 5 | 3.6 | |

| Crack cocaine | 5 | 2.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4.5 | 4 | 2.9 | 0.003 |

| Something else | 7 | 4.1 | 1 | 50.0 | 2 | 25 | 0 | 0.0 | 4 | 2.9 | |

| Know how to recognize an overdose Number of overdose experiences |

Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Personal (n = 410): IQR: 4 | 3.61 | 8.6 | 0.42 | 0.9 | 1.66 | 2.61 | 3.79 | 8.7 | 4.22 | 9.4 | 2.66 (df = 3) 0.05 |

| Witnessed (n = 462): IQR: 13 | 12.92 | 20.4 | 10.41 | 23.5 | 10.4 | 17.25 | 9.43 | 16.2 | 14.55 | 21.4 | 1.87 (df = 3) 0.13 |

| Ever witnessed an overdose | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| No | 47 | 10.2 | 8 | 21.6 | 2 | 5.7 | 8 | 9.1 | 29 | 9.6 | 0.14 |

| Yes | 415 | 89.8 | 29 | 78.4 | 33 | 94.3 | 80 | 90.9 | 273 | 90.4 | |

| Ever overdosed | 32.8 (df = 3) | ||||||||||

| No | 172 | 37.0 | 29 | 78.4 | 16 | 45.7 | 32 | 36.4 | 95 | 31.1 | |

| Yes | 293 | 63.0 | 8 | 21.6 | 19 | 54.3 | 56 | 63.6 | 210 | 68.9 | <.0001 |

| Suspect fentanyl involved in last overdose | n = 236 | n = 11 | n = 13 | n = 52 | n = 163 | ||||||

| No | 57 | 24.2 | 5 | 62.5 | 7 | 53.8 | 11 | 21.2 | 34 | 20.9 | |

| Yes | 179 | 75.8 | 3 | 37.5 | 6 | 46.2 | 41 | 78.8 | 129 | 79.1 | 0.004 |

| Reason for suspecting fentanyl involved in last overdose | n = 179 | n = 3 | n = 6 | n = 41 | n = 129 | ||||||

| Overdosed quickly | 65 | 36.3 | 2 | 66.7 | 4 | 66.7 | 15 | 36.6 | 46 | 35.7 | |

| Feel, color, taste | 77 | 43.0 | 1 | 33.3 | 2 | 33.3 | 16 | 39.0 | 59 | 45.7 | |

| Fentanyl test strip | 2 | 1.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2.4 | 1 | 0.8 | |

| Someone else overdosed quickly | 4 | 2.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 4 | 3.1 | |

| Dealer said so | 16 | 8.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 9.8 | 12 | 9.3 | |

| Another reason | 61 | 34.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 33.3 | 14 | 34.1 | 45 | 34.9 | |

| Looking to buy fentanyl | 4 | 2.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 7.1 | 3 | 6.7 | |

| Tested positive for it during mandatory urine drug testing | 14 | 7.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 42.9 | 8 | 17.8 | |

| It is in everything/fentanyl saturation in local drug supply | 11 | 6.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 21.4 | 8 | 17.8 | |

| Word of mouth | 3 | 1.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 7.1 | 2 | 4.4 | |

| Small amount | 6 | 3.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 50 | 0 | 0.0 | 5 | 11.1 | |

| Another reason*** | 23 | 12.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 50 | 3 | 21.4 | 19 | 42.2 | |

| Prepared to respond to an overdose | |||||||||||

| Naloxone awareness | |||||||||||

| No | 13 | 2.8 | 3 | 8.1 | 2 | 5.7 | 1 | 1.1 | 7 | 2.3 | |

| Yes | 452 | 97.2 | 34 | 91.9 | 33 | 94.3 | 87 | 98.9 | 298 | 97.7 | 0.08 |

| Have personal naloxone kit | |||||||||||

| No | 174 | 37.4 | 28 | 75.7 | 19 | 54.3 | 39 | 44.3 | 88 | 28.9 | 38.7 (df = 3) |

| Yes | 291 | 62.6 | 9 | 24.3 | 16 | 45.7 | 49 | 55.7 | 217 | 71.1 | <.0001 |

| Trained in naloxone | |||||||||||

| No | 118 | 25.4 | 21 | 56.8 | 12 | 34.3 | 24 | 27.3 | 61 | 20.0 | 25.5 (df = 3) |

| Yes | 347 | 74.6 | 16 | 43.2 | 23 | 65.7 | 64 | 72.7 | 244 | 80.0 | <.0001 |

| Who trained to use naloxone | n = 284 | n = 15 | n = 15 | n = 57 | n = 197 | ||||||

| Community organization | 93 | 19.2 | 10 | 66.7 | 4 | 26.7 | 19 | 33.3 | 60 | 30.5 | — |

| In treatment | 85 | 17.6 | 1 | 6.7 | 2 | 13.3 | 16 | 28.1 | 66 | 33.5 | |

| Syringe services program | 61 | 12.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 20 | 7 | 12.3 | 51 | 25.9 | |

| Doctor, pharmacist or another provider | 47 | 9.7 | 1 | 6.7 | 4 | 26.7 | 15 | 26.3 | 27 | 13.7 | |

| Friend of family member | 34 | 7.0 | 2 | 13.3 | 3 | 20 | 10 | 17.5 | 19 | 9.6 | |

| Self-taught | 19 | 3.9 | 1 | 6.7 | 1 | 6.7 | 5 | 8.8 | 12 | 6.1 | |

| Jail | 10 | 2.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 6.7 | 3 | 5.3 | 6 | 3.0 | |

| Another method**** | 22 | 4.5 | 2 | 13.3 | 1 | 6.7 | 6 | 10.5 | 13 | 6.6 | |

| 911 Called – last witnessed overdose | n = 460 | n = 36 | n = 33 | n = 88 | n = 303 | ||||||

| Don’t know | 6 | 1.3 | 1 | 2.8 | 1 | 3.0 | 2 | 2.3 | 2 | 0.7 | |

| No | 129 | 28.0 | 1 | 2.8 | 8 | 24.2 | 24 | 27.3 | 96 | 31.7 | 0.003 |

| Yes | 278 | 60.4 | 26 | 72.2 | 22 | 66.7 | 54 | 61.4 | 176 | 58.1 | |

| Never witnessed an overdose | 47 | 10.2 | 8 | 22.2 | 2 | 6.1 | 8 | 9.1 | 29 | 9.6 | — |

| Naloxone administered – last witnessed overdose | n = 417 | n = 29 | n = 33 | n = 80 | n = 275 | ||||||

| No/Don’t know | 83 | 19.9 | 9 | 31.0 | 9 | 27.3 | 18 | 22.5 | 47 | 17.1 | 5.08 (df = 3) |

| Yes | 334 | 80.1 | 20 | 69.0 | 24 | 72.7 | 62 | 77.5 | 228 | 82.9 | 0.17 |

| Personally administered | 141 | 42.3 | 6 | 30.0 | 11 | 45.8 | 19 | 30.6 | 105 | 46.1 | 5.78 (df = 3) |

| Someone else administered | 192 | 57.7 | 14 | 70.0 | 13 | 54.2 | 43 | 69.4 | 123 | 53.9 | 0.12 |

Note. Test-statistic is based on a chi-square test. Fisher’s exact tests were used when cell count was <5; only p-values are reported for Fisher’s Exact. DF: degrees of freedom. Bolded p-value = significant at p < 0.05.

Other reasons for suspected fentanyl in drug supply: amount; prior experience with dealer; saw other people’s response to the drug.

Not assessed in Lowell, Quincy, and Cape Cod.

Other reason for suspected fentanyl involvement in last overdose: not sure: used a lot; non-regular dealer; never overdosed on heroin before; shouldn’t have gone out; overdosed, must be fentanyl; didn’t buy from regular dealer; took many narcan kits to come back; watching reactions of other people who used.

Other ways that people were naloxone trained included: shelter; health department; trained at scene; job training; housing site; research study; police; not specified.

Consistent with the quantitative findings, individuals who had no history of opioid use did not report having experienced an opioid overdose while using cocaine. However, several of those who had no history of opioid use reported witnessing an opioid overdose as a result of having friends or family who use opioids. The most overdose experiences, whether personal or witnessed, were reported by people with a current or past history of opioid use. These individuals provided clear descriptions of how to recognize an opioid overdose. As participants described, social networks may mediate overdose risk reduction. For example, Manny, who used cocaine and had a prior history of overdose, noted, “Their lips turn blue. They start making this noise. They call it the death gurgle or something and they just tense up like they’re having a seizure, but they don’t seize.” Another participant described being able to determine the signs and symptoms of an overdose after witnessing several friends overdose:

Well, [I knew he was overdosing] just, after he did his shot, I just noticed he started reacting really funny. He was really hyper at first, and like, just acting really bizarre, and the next thing you know he’s slumped over, he’s falling on his ass, and his eyes are rolling in the back of his head, and I just knew to watch him, because I’ve seen so many people OD. … I’ve had a friend go into a seizure for five minutes, and I had to put my hands in his mouth, and he almost bit my damn fingers off, because I didn’t want him to chew his tongue off.

– Mark, uses cocaine and opioids

Prepared to respond to an overdose

Nearly all participants had heard of naloxone (97.2%). When stratified by cocaine/opioid use history, 8.1% of participants who had used cocaine in the past 30 days and did not have a history of opioid use had not heard of naloxone as well as 5.7% of those who had used cocaine and did have a history of opioid use, 1.1% of those who had used opioids only, and 2.3% of those who had used cocaine and opioids in the past 30 days (p = 0.08).

The majority of the sample (62.6%) reported having a personal naloxone kit and having been trained to use naloxone (74.6%). Participants who used only cocaine in the past 30 days and had no history of opioid use reported the lowest frequency of having a personal naloxone kit (24.3%) and naloxone training (43.2%). Significantly more participants with a past or current history of opioid use reported having naloxone (24.3% cocaine use without opioid use history; 45.7% cocaine use with opioid use history; 55.7% opioid use only; 71.1% cocaine and opioid use; p < 0.0001) and being trained in how to use naloxone (43.2% cocaine use without opioid use history; 65.7% cocaine use with opioid use history; 72.7% opioid use only; 80.0% cocaine and opioid use; p < 0.0001). The most common way that participants learned how to use naloxone was through a community organization (19.2%), followed by a treatment facility (17.6%), syringe service program (12.6%), and a doctor, pharmacist or another provider (9.7%).

Among those who had witnessed an overdose, 60.4% indicated that 911 was called at the last overdose they had witnessed, with the highest reported use of 911 reported by participants who currently use cocaine and have no opioid use history (72.2%) and the lowest reported use of 911 reported among those who use cocaine and opioids (58.1%; p < 0.003). Additionally, of those who had witnessed an overdose, 80.1% indicated that naloxone was administered at the last overdose they had witnessed. The lowest provision of naloxone was reported by individuals who had used cocaine in the past 30 days and had no known opioid use history (69.0%) and the highest reported provision of naloxone at the last overdose witnessed (82.9%) was reported by those who had used cocaine and opioids in the past 30 days (p = 0.17). Of those who indicated that naloxone was administered at the last overdose they witnessed, 42.3% indicated that they had administered the naloxone themselves, with the highest provision of naloxone reported by people who use cocaine and opioids (46.1%) and the lowest provision of naloxone reported among those who use cocaine and have no history of opioid use (30.0%; p = 0.12).

In our qualitative interviews, we found that a number of participants were unprepared to respond to an overdose as they did not know what naloxone was. Others, namely those without a history of opioid use, indicated that they did not carry naloxone because they did not think they needed it. For example, Tommy, who had no history of opioid use, reported, “No [I don’t have naloxone]…It’s not something I’ve ever needed.” Similarly, while recognizing the value of carrying naloxone, another participant indicated that he does not carry naloxone and has concerns about the legality of carrying it, noting:

Narcan’s basically for, you know, opioids. It’s not for, you know, crack cocaine, but maybe I could carry it in case I had to use it to help somebody else, but I don’t know if you’re allowed legally to do that if you haven’t been trained, so I just haven’t gone through all that.

– Ron, uses cocaine, no opioid use history

Several other participants without a history of opioid use reported being unprepared to respond to an overdose. For example, Carlos, who had no opioid use history, indicated that he knew about naloxone but did not carry it, had never been trained to use it, and also described misconceptions about administering naloxone, noting, “I never used it….I’m scared of that. I don’t know how to do it. And I not trying to kill nobody.” The lack of preparedness to respond to an overdose was also reported by a participant while describing the only overdose she had witnessed:

Yes, I did [witness an overdose].… I didn’t know he was into the heroin, but I know he took something. And his body started shaking like convulsing, and he was foaming at the mouth; so that’s when somebody called 911. And the police and the EMS determined it was heroin and I didn’t know. He was my best friend for five years and I never knew he did heroin. Never knew it, ‘cause we used to do Benzos together, that’s all I ever seen him do and drink beer. I never seen him shoot up heroin or snort it, or however they do it. And it was scary. Frightening.….I wanted to help him, but I didn’t know what to do. I didn’t know how to give him CPR, I didn’t have any equipment on me to help him.

– Debbie, uses cocaine, no opioid use history

This participant’s quote helps to contextualize the quantitative findings, by suggesting that while participants with no history of opioid use tend to be less prepared to respond to an overdose by administering naloxone, they readily called 911 because these participants recognized that they did not have the training or equipment to reverse the overdose and save a life.

Many participants were prepared to respond to an overdose due in part to their current or past history of opioid use. Indeed, those with a history of opioid use reported knowing what naloxone is and where to get it, even if they were not actively using opioids at the time of the survey. For example, Billy, who currently uses cocaine and had a past history of opioid use, indicated, “I know [naloxone] instantly makes you sick. I know that it stops an overdose. I know that it can save people’s lives if you catch it in time.” Several participants who were actively using opioids reported receiving naloxone and being trained to use it at a syringe service program. For example, Matty, who was actively using cocaine and opioids, indicated that he carried naloxone and knew how to administer it, noting, “I have [naloxone] on me. It’s in my backpack… [I got trained] at the needle exchange…. They showed me… It’s the nasal. [I got trained] last year…. When they first came out with those ones.” Participants who were in treatment for opioid use disorder or had previously been in detox also reported having acquired naloxone and receiving naloxone training while in treatment. For example, one participant described having naloxone, knowing where to get it, and feeling as though it was easy to use:

They’ve made everybody-like, detox, everybody makes you aware of [Naloxone]. Just walk into CVS and get it at no cost. [The Narcan kit that I have now,] I got it from a treatment facility. Yeah, and I had two or three of them. I don’t know exactly how many I have at home, but yeah. The square [one] for the nose… Very basic, yeah, and they’re great, you know, again sad to say, they’re great for what they need it for, you know. It’s as simple as can be, and, you know, anybody can do that, yeah…It’s easy [to get too], just go to CVS. You know, it’s as easy as getting your needles.

– Ritchie, uses cocaine and opioids.

In addition to learning about how to administer naloxone from one’s treatment provider, many participants with a past or active history of opioid use described their capacity to respond to an overdose and attributed their ability to respond to having witnessed many overdoses throughout their lives. For example, Karen, who was actively using cocaine and opioids reported carrying naloxone on her and knowing how to use it because she had, “witnessed [naloxone being used] many times with my daughter. Whatever the drug is, it takes out the, you know, poison, the heroin in you and it just brings you back… it’s a miracle thing.” Another participant described his history of witnessing overdoses from an early age and noted:

Honestly, I was exposed at such a young age, too young of an age, that I’ve witnessed OD’s when I was, like, eight, nine years old. I’ve seen people give people sternum rubs, I’ve seen somebody drag somebody in the shower, put ice down the bottom of their pants and slap them around for 10 minutes to get them up. And that was back in the day when there wasn’t really Narcan going around, you know? You had to call an ambulance and get a shot in the heart, you know what I mean? Stuff like that. But, you know, fortunately now we have Narcan available, and it’s come in handy. I probably would’ve lost a good couple handfuls of people if it wasn’t for that.

– Kevin, uses cocaine and opioids

Finally, while many more of the participants who were prepared to respond to an overdose were actively using opioids, a few participants who were not actively using opioids reported having a social network that included people who used opioids. Two of these participants indicated that naloxone was easy to acquire and recognized the importance of carrying naloxone, regardless of whether you use opioids or not, as it could save lives and is greatly needed in the age of fentanyl.

I feel like Narcan is very easy to obtain. So I don’t understand why it’s like, everybody doesn’t have it. Because I know everybody knows somebody that has overdosed in the past, or even themselves that have overdosed. And I feel like to keep us alive, it should all be more common to have something on us to save somebody else’s life.

– Jada, uses cocaine and has an opioid use history

Me personally, I don’t have a personal [naloxone kit] with me but like you go into Lynn and there is clinics up there, you can pretty much, they’ll give you stuff…just to try to keep you safe, so, it’s available. Like I got friends personally that carry it right on their person at all times. I’ve known people personally that don’t even use that carry it just in case one of their friends is using [and] something happens. Which is an excellent gesture [of your] willingness to help. It’s dangerous out there today.

– Mickey, uses cocaine, no opioid use history

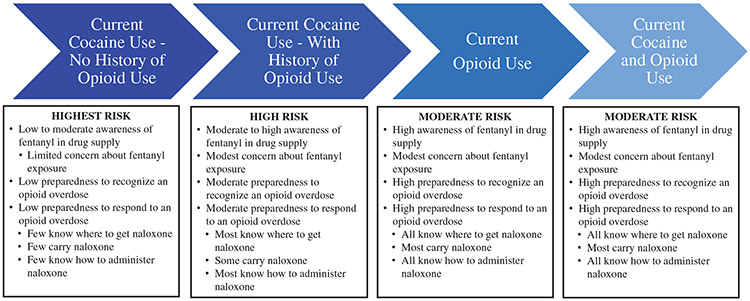

Gradients of fatal overdose risk and overdose response preparedness

In summary, participants described gradients of fatal overdose risk and overdose response preparedness that varied according to patterns of substance use. As illustrated in Figure 1 and described above, individuals who use cocaine and have no history of using opioids appear to be at greatest risk for a fatal opioid-involved overdose and the least prepared to respond to an opioid-involved overdose as a bystander; these risks are lessened among individuals who have intentionally used opioids. Collectively, these results have implications for future overdose prevention and response activities for people who intentionally use cocaine vs. opioids and other drugs.

Figure 1.

Gradients of fatal opioid overdose risk and response preparedness among people who use drugs.

Discussion

This is the first study, to our knowledge, to use mixed methods to explore indicators of opioid overdose risk and overdose response preparedness by patterns of cocaine and/or opioid use. Findings showed that, relative to those who have a past or current history of opioid use, participants who use cocaine and have no history of opioid use are more likely to be unaware of fentanyl in the drug supply; are less likely to know how to recognize an opioid overdose; and are less prepared to respond to an overdose. These findings help generate hypotheses about what is contributing to the increasing trend in fentanyl and cocaine positive toxicology results among people who experienced nonfatal45 and fatal overdoses1,3,13 in recent years. Based on the findings from this study, we theorize that individuals who unintentionally consume fentanyl-contaminated cocaine and are unaware of fentanyl in the drug supply are at much greater risk for personally experiencing a fentanyl overdose and less prepared to respond to a witnessed overdose than individuals who have a past or current history of opioid use. These findings extend prior research on overdose risk and preparedness among people who use drugs33,46-48 and underscore the need for public health intervention strategies to increase awareness of fentanyl contamination in the drug supply and access to and uptake of harm reduction strategies to prevent fatal fentanyl overdoses among people who use cocaine and other drugs.

Despite high fentanyl awareness overall, a lower proportion of participants in the present study knew of or suspected that fentanyl was in the drug supply, with significant differences observed according to substance use history. Indeed, 92% of participants who used cocaine and had no history of opioid use reported that they did not believe fentanyl was in their drugs whereas most of those (>82%) who were currently using opioids believed fentanyl was in their drugs. Qualitative interviews supported these findings as many participants who had no history of opioid use indicated that they did not believe that their drugs ever contained fentanyl. Research finds that individuals who do not use opioids are at elevated risk of fatal opioid overdose due to a lack of tolerance to opioids.2 Given evidence of ongoing fentanyl contamination of the cocaine supply,1,3,9,13 lack of awareness of fentanyl in the drug supply has the potential to be particularly lethal for individuals who unintentionally consume fentanyl-contaminated cocaine.

The small subset of participants who only used cocaine and who were aware that the drug supply was contaminated with fentanyl had predominately learned about possible contamination from their drug use network, a finding which aligns with previous research which showed that individuals who use drugs often acquire information about drug safety through their drug use network.30 Conversely, and consistent with prior research,49,50 people who had a current or past history of opioid use tended to learn about fentanyl in the drug supply through their own use experiences or in the context of receiving treatment for substance use disorder. These findings add to the literature by showing significant gaps in awareness of fentanyl in the drug supply among people who do not intentionally use opioids and underscore the need to increase awareness about fentanyl in the drug supply, particularly among those with no history of intentional opioid use in order to prevent fatal opioid-involved overdoses.

In addition to being less aware of fentanyl in the drug supply, individuals who used cocaine in our sample and did not have a history of opioid use were less able to recognize the signs and symptoms of an opioid overdose, relative to individuals who were actively using or who had previously used opioids. Among the small subset of participants who had personally experienced an overdose and had no history of opioid use, only a few attributed the overdose to fentanyl, whereas the majority of those with a past or current history of opioid use attributed their overdose experiences to fentanyl. Similarly, those who were actively using opioids reported significantly more experiences of having witnessed an overdose than those without a history of opioid use. Moreover, our qualitative data demonstrated that, relative to people with no opioid use history, individuals who had personally experienced an overdose or witnessed other people overdosing could clearly describe the signs and symptoms of an opioid overdose and knew when medical intervention was necessary. Notably, however, there were a few outliers who had no opioid use history but knew how to respond to an overdose based on witnessing the experiences of family members or friends living with opioid use disorder. These findings extend prior qualitative research describing the ability of people who intentionally use opioids to recognize an overdose32 and emphasize the importance of training all people to know how to recognize an overdose regardless of whether they use opioids themselves.

The present study also found that participants who used cocaine and did not have a history of opioid use were less prepared to respond to an opioid overdose, relative to individuals with current or past opioid use. In fact, although awareness of naloxone was high among the full sample (97.2%), only 62.6% carried naloxone on them. Based on a long-standing, state-wide community naloxone distribution program in Massachusetts, it may not be surprising that both awareness and possession of naloxone were higher among this sample than in other studies of people who use drugs.51 Still, we detected notable differences according to substance use history. Indeed, the majority of those with a past or current history of opioid use carried naloxone, whereas less than a quarter of those without an opioid use history had a naloxone kit on them or at the place where they use drugs. Further, our qualitative findings indicated that most of the participants who did not carry naloxone made the conscious decision not to carry it because they only used cocaine and did not believe they were at risk of experiencing an opioid overdose. Still, the majority of participants who had witnessed an overdose, used cocaine, and did (72.7%) and did not (69.0%) have a history of opioid use reported that naloxone was given at the last overdose, suggesting that while these individuals may be less equipped to personally administer naloxone, there was someone nearby and/or first responders arrived on the scene early enough to administer naloxone. Nonetheless, there is still room for improvement as more than a quarter of these participants indicated that naloxone was not administered or they did not know whether it was administered at the last overdose they witnessed. Notably, participants who use cocaine, regardless of their opioid use history, saw the value of carrying naloxone - not only so it was on hand for someone else to administer to them if they were to overdose, but also, as more commonly noted, to allow them to intervene and save the life of another person overdosing. Extending prior research among people who use drugs in the U.S.,48,51-53 this sense of altruism and the willingness to carry naloxone should be leveraged in future efforts to ensure the widespread possession of this lifesaving medication among all people, regardless of their personal use of or proximity to people who use opioids.

Though carrying naloxone is a necessity for being able to properly respond to an overdose, knowing how to properly administer it and having the self-efficacy to do so can be the difference between a fatal vs. non-fatal overdose.32,33,53,54 Notably, greater than 68% of our participants with a past or current history of opioid use had been trained to use naloxone, whereas only about two-fifths of those who used cocaine and had no known opioid use history were trained. Extending prior research among people who use illicit opioids in Rhode Island,48 findings from the present study found that the majority of those who had witnessed an overdose, independent of substance use history, had personally provided or observed naloxone being provided to an overdose victim. Further, our qualitative data showed that those with an opioid use history reported routinely, quickly, and easily responding to a person experiencing an overdose by administering naloxone, whereas those without an opioid use history, tended to report uncertainty about how to administer naloxone and in some cases reported an unwillingness to do so out of fear that they could do more harm. Interestingly, however, those with a current or past history of opioid use less frequently indicated that 911 was called at the last overdose witnessed, relative to those without an opioid use history. Our qualitative data suggest that individuals without an opioid use history may be more likely than those with an opioid use history to call 911 because they do not have naloxone available or recognize that they lack the training to properly intervene as a first responder. While 911 should be called regardless of whether one is able to administer naloxone to a person who is overdosing, not having naloxone available or administering it incorrectly could increase the risk that an individual who is overdosing dies before emergency personnel can arrive on the scene.32,33,53,54 These findings highlight the importance of having access to naloxone and being trained to use it to prevent a fatal overdose, particularly among those who use cocaine and have no history of opioid use.

Interventions are warranted to help prevent fatal overdoses among people who use cocaine and have not used opioids and/or do not have social networks comprised of people who use opioids. While campaigns to educate people about the potential for fentanyl contamination in the cocaine supply are vital, as noted by participants, this information is routinely disseminated in treatment facilities and syringe service programs. However, individuals who only use cocaine access drug treatment services55 and harm reduction programs52 at lower rates than those who use opioids. Thus, there is a need for campaigns that reach the broader public, outside of treatment settings, through such pathways as billboards, TV, and web-based advertisements. Such tactics have been used in other areas of the U.S., such as Ohio,56 and should be brought to Massachusetts and other overdose hotspots. Further, while knowledge of the potential risk of fentanyl exposure through the use of contaminated cocaine is essential, individuals who use cocaine require harm reduction strategies that can help them mitigate the risk of a fatal fentanyl overdose. Such strategies might include providing people who do not use opioids and their dealers with fentanyl test strips so they can identify the presence of fentanyl in their cocaine and potentially implement harm reduction practices.57 All people who use drugs could also benefit from access to drug checking services,58-60 which provide insight into the presence of all active drugs, including fentanyl and its many analogs, as well as the relative quantity of fentanyl in one’s drugs. Our team has recently initiated a program to embed drug checking capabilities within several harm reduction organizations in Massachusetts, with the long-term goal of using the technology to provide individuals who use drugs with information about the substances they are consuming so that they can implement appropriate harm reduction strategies to mitigate their risk of overdose (https://heller.brandeis.edu/opioid-policy/). Continued efforts must also be made to increase the distribution of naloxone and train more people in overdose prevention preparedness, including naloxone administration, regardless of their substance use history. Findings from our study suggest a willingness on the part of individuals who use drugs to administer naloxone in order to save a life; these altruistic attitudes can and should be leveraged among all residents of Massachusetts in order to reduce the risk of fatal overdose among people who intentionally and unintentionally consume fentanyl.

Several methodological limitations should be considered in light of our findings. Given that we conducted a cross-sectional study, causality cannot be inferred. Additionally, we explored the experiences of people who used drugs in Massachusetts, including those living in high-risk areas and among members of subpopulations at greater risk for fatal opioid overdoses (e.g. Hispanic populations); thus, our findings may not be generalizable to individuals living in other regions of the U.S. or from lower-risk populations. Although we utilized convenience sampling for all sites, our use of RDS in New Bedford and purposive sampling in all other locations may have introduced sampling bias. Additionally, we did not assess lifetime opioid use and had to rely on qualitative interviews and quantitative indicators of opioid use history (e.g. past methadone use); thus, it is possible that misclassification occurred and the true proportion of those without an opioid use history was lower than reported. Additionally, some of our drug use categories relied on relatively small sample sizes; thus, we did not have the power to examine risk factors using adjusted multivariable models. However, common to rapid assessment, these descriptive findings are intended to be preliminary and serve as a starting point for future research. Finally, we tended to recruit individuals living with more advanced substance use disorders as well as low-income, marginally-housed people. Future research should aim to recruit a larger sample of higher income, stably-housed individuals who recreationally use cocaine as these individuals may be even less aware of fentanyl in the drug supply, less equipped to respond to an opioid overdose, and thus at even greater risk of a fatal overdose relative to participants in the present study.

Conclusion

Through our novel mixed-methods study, we documented the limited awareness of fentanyl in the drug supply and the limited ability to respond to an opioid overdose among people who use cocaine and who do not intentionally consume opioids. Public education and health promotion campaigns are needed to increase awareness about fentanyl in the drug supply among people who use cocaine and do not use opioids. Additionally, harm reduction tools such as fentanyl test strips, drug checking services, naloxone, and overdose prevention trainings must be made widely available to all people at risk of consuming lethal doses of fentanyl or who may come into contact with someone experiencing an overdose in order to reduce the incidence of fatal overdoses among people who use cocaine and other drugs in Massachusetts.

Acknowledgment

The authors wish to thank the participants and the community partners who helped to make this research possible. We would also like to thank our study funders, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Bureau of Substance Addiction Services at the Massachusetts Department of Public Health, with a special thanks to Sarah Ruiz and Brittni Reilly. Finally, we would like to acknowledge the hard work and dedication of the RACK study teams at Boston Medical Center and Brandeis University. The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation of the manuscript, approval of the manuscript, and decision to submit the manuscript for publication. MDPH did review the final draft of the manuscript prior to submitting for publication.

Funding

This study is funded by grant from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC; NU17CE002724 (PI: Alawad), NU17CE002724 (PI: Ruiz)] to the Massachusetts Department of Public Health (MDPH), Bureau of Substance Addiction Services supported this research. Dr. Hughto is also supported by COBRE on Opioids and Overdose funded by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under [grant number P20GM125507].

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data can be made available by emailing the senior author.

References

- [1].O’Donnell JK, Halpin J, Mattson CL, Goldberger BA, Gladden RM. Deaths involving fentanyl, fentanyl analogs, and U-47700—10 states, July–December 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(43):1197–1202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].McCall Jones C, Baldwin GT, Compton WM. Recent increases in cocaine-related overdose deaths and the role of opioids. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(3):430–432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Massachusetts Department of Public Health. The Massachusetts opioid epidemic: a data visualization of findings from the Chapter 55 report. 2018. http://www.mass.gov/chapter55/ViewinArticle. Accessed January 17, 2018.

- [4].MDPH. Data brief: opioid1-related overdose deaths among Massachusetts residents. 2017. https://www.mass.gov/doc/opioid-related-overdose-deaths-among-ma-residents-august-2017/download. Accessed January 17, 2021.

- [5].MDPH. Data brief trends in stimulant-related overdose deaths. 2020. https://www.mass.gov/doc/data-brief-trends-in-stimulantrelated-overdose-deaths-february-2020/download.

- [6].Aaohn J, Week E, Unit A. Influx of fentanyl-laced counterfeit pills and toxic fentanyl-related compounds further increases risk of fentanyl-related overdose and fatalities. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- [7].DEA Bulletin DEA-MIA-BUL-039-18: Deadly Contaminated Cocaine Widespread in Florida. DEA Miami Field Division. 2018. https://www.dea.gov/sites/default/files/2018-07/BUL-039-18.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- [8].Rudd RA, Seth P, David F, Scholl L. Increases in drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths – United States, 2010–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(50–51):1445–1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].DEA. Cocaine/fentanyl combination in Pennsylvania. 2018. https://www.dea.gov/sites/default/files/2018-07/BUL-061-18%20Cocaine%20Fentanyl%20Combination%20in%20Pennsylvania%20–%20UNCLASSIFIED.PDF.

- [10].Pichini S, Solimini R, Berretta P, Pacifici R, Busardò FP. Acute intoxications and fatalities from illicit fentanyl and analogues: an update. Ther Drug Monit. 2018;40(1):38–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].McHugh RK, Votaw VR, Bogunovic O, Karakula SL, Griffin ML, Weiss RD. Anxiety sensitivity and nonmedical benzodiazepine use among adults with opioid use disorder. Addict Behav. 2017;65:283–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Stein MD, Anderson BJ, Kenney SR, Bailey GL. Beliefs about the consequences of using benzodiazepines among persons with opioid use disorder. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2017;77:67–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Nolan ML, Shamasunder S, Colon-Berezin C, Kunins HV, Paone D. Increased presence of fentanyl in cocaine-involved fatal overdoses: implications for prevention. J Urban Health. 2019;96(1):49–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Administration DE. National drug threat assessment. Annual drug report 2019. Springfield, Virginia: US Department of Justice, Drug Enforcement Administration; 2019. https://www.dea.gov/sites/default/files/2020-02/DIR-007-20%202019%20National%20Drug%20Threat%20Assessment%20-%20low%20res210.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Cano M, Oh S, Salas-Wright CP, Vaughn MG. Cocaine use and overdose mortality in the United States: evidence from two national data sources, 2002–2018. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2020;214:108148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Roy É, Richer I, Arruda N, Vandermeerschen J, Bruneau J. Patterns of cocaine and opioid co-use and polyroutes of administration among street-based cocaine users in Montréal, Canada. Int J Drug Policy. 2013;24(2):142–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Leri F, Bruneau J, Stewart J. Understanding polydrug use: review of heroin and cocaine co-use. Addiction. 2003;98(1):7–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Leri F, Stewart J, Tremblay A, Bruneau J. Heroin and cocaine co-use in a group of injection drug users in Montreal. J Psych Neurosci. 2004;29(1):40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Harrell PT, Mancha BE, Petras H, Trenz RC, Latimer WW. Latent classes of heroin and cocaine users predict unique HIV/HCV risk factors. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;122(3):220–227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Higashikawa Y, Suzuki S. Studies on 1-(2-phenethyl)-4-(N-propionylanilino)piperidine (fentanyl) and its related compounds. VI. Structure-analgesic activity relationship for fentanyl, methyl-substituted fentanyls and other analogues. Forensic Toxicol. 2008;26(1):1–5. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Amlani A, McKee G, Khamis N, Raghukumar G, Tsang E, Buxton JA. Why the FUSS (Fentanyl Urine Screen Study)? A cross-sectional survey to characterize an emerging threat to people who use drugs in British Columbia, Canada. Harm Reduct J. 2015;12(1):54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Darke S, Hall W. Levels and correlates of polydrug use among heroin users and regular amphetamine users. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1995;39(3):231–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Kedia S, Sell MA, Relyea G. Mono- versus polydrug abuse patterns among publicly funded clients. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2007;2(1):33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Grov C, Kelly BC, Parsons JT. Polydrug use among club-going young adults recruited through time-space sampling. Subst Use Misuse. 2009;44(6):848–864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Lorvick J, Browne EN, Lambdin BH, Comfort M. Polydrug use patterns, risk behavior and unmet healthcare need in a community-based sample of women who use cocaine, heroin or methamphetamine. Addict Behav. 2018;85:94–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].McKee G, Amlani A, Buxton J. Illicit fentanyl: An emerging threat to people who use drugs in BC. BCMJ. 2015;57(6):235. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Klar S, Brodkin E, Gibson E, et al. Furanyl-fentanyl overdose events caused by smoking contaminated crack cocaine—British Columbia, Canada, July 15–18, 2016. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can. 2016;36(9):200–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Armenian P, Whitman JD, Badea A, et al. Notes from the field: unintentional fentanyl overdoses among persons who thought they were snorting cocaine – Fresno, California, January 7, 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(31):687–688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Mars SG, Ondocsin J, Ciccarone D. Sold as heroin: perceptions and use of an evolving drug in Baltimore, MD. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2018;50(2):167–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Frank D, Mateu-Gelabert P, Guarino H, et al. High risk and little knowledge: overdose experiences and knowledge among young adult nonmedical prescription opioid users. Int J Drug Policy. 2015;26(1):84–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Kerr D, Kelly AM, Dietze P, Jolley D, Barger B. Randomized controlled trial comparing the effectiveness and safety of intranasal and intramuscular naloxone for the treatment of suspected heroin overdose. Addiction. 2009;104(12):2067–2074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Green TC, Heimer R, Grau LE. Distinguishing signs of opioid overdose and indication for naloxone: an evaluation of six overdose training and naloxone distribution programs in the United States. Addiction. 2008;103(6):979–989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Walley AY, Xuan Z, Hackman HH, et al. Opioid overdose rates and implementation of overdose education and nasal naloxone distribution in Massachusetts: interrupted time series analysis. BMJ. 2013;346:f174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Best D, Gossop M, Man L-H, Stillwell G, Coomber R, Strang J. Peer overdose resuscitation: multiple intervention strategies and time to response by drug users who witness overdose. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2002;21(3):269–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Doe-Simkins M, Walley AY, Epstein A, Moyer P. Saved by the nose: bystander-administered intranasal naloxone hydrochloride for opioid overdose. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(5):788–791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Kestler A, Buxton J, Meckling G, et al. Factors associated with participation in an emergency department-based take-home naloxone program for at-risk opioid users. Ann Emerg Med. 2017;69(3):340–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Tobin K, Clyde C, Davey-Rothwell M, Latkin C. Awareness and access to naloxone necessary but not sufficient: examining gaps in the naloxone cascade. Int J Drug Policy. 2018;59:94–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].You H-S, Ha J, Kang C-Y, et al. Regional variation in states’ naloxone accessibility laws in association with opioid overdose death rates-Observational study (STROBE compliant). Medicine. 2020;99(22):e20033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Ong AR, Lee S, Bonar EE. Understanding disparities in access to naloxone among people who inject drugs in Southeast Michigan using respondent driven sampling. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2020;206:107743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Mass.Gov. Learn more about SUDORS: about the state unintentional drug overdose reporting system. 2021. https://www.mass.gov/service-details/learn-more-about-sudors. Accessed April 16, 2021.

- [41].Tongco MDC. Purposive sampling as a tool for informant selection. Ethnobot Res App. 2007;5:147–158. [Google Scholar]