Abstract

Background

Invasive infections due to Trichosporon spp. are life-threatening opportunistic fungal infections that require complex clinical management. Guidelines assist clinicians but can be challenging to comply with.

Objectives

To develop a scoring tool to facilitate and quantify adherence to current guideline recommendations for invasive trichosporonosis.

Methods

We reviewed the current guideline for managing rare yeast infections (ECMM, ISHAM and ASM). The most important recommendations for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up were assembled and weighted according to their strength of recommendation and level of evidence. Additional items considered highly relevant for clinical management were also included.

Results

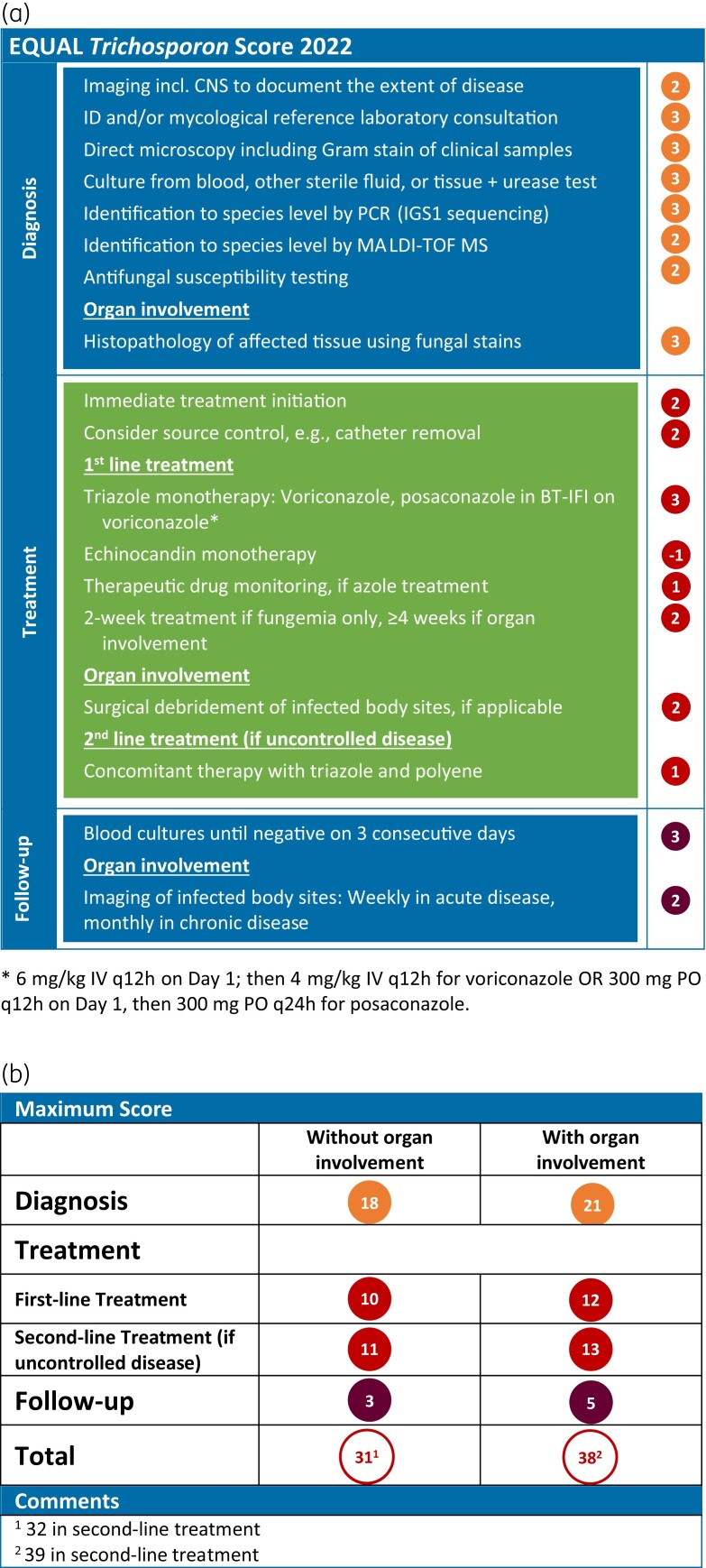

The resulting EQUAL Trichosporon Score 2022 comprises 18 items, with a maximum score of 39 points. For diagnostics, seven or eight items, depending on whether organ involvement is present or not, apply, resulting in a maximum of 18 or 21 points. Recommendations on diagnostics include imaging, infectious diseases expert consultation, culture, microscopy, molecular techniques, histopathology, and susceptibility testing. For treatment, six recommendations with a maximum of ten points were identified, with two additional points for organ involvement and one point for second-line treatment in uncontrolled disease. Treatment recommendations include immediate initiation, source control, pharmacological treatment, therapeutic drug monitoring, treatment duration and surgical intervention. Follow-up comprises two items with five points maximum, covering follow-up blood cultures and imaging.

Conclusions

The EQUAL Trichosporon Score weighs and aggregates factors recommended for optimal management of Trichosporon infections. It provides a tool for antifungal stewardship as well as for measuring guideline adherence, but remains to be correlated with patient outcomes.

Introduction

Candida species represent the majority of fungal pathogens encountered in hospitalized patients and are a frequent cause of nosocomial bloodstream infection.1 However, uncommon yeasts other than Candida and Cryptococcus spp. have increasingly emerged as pathogens over the last few decades.2 These include infections due to Trichosporon species. These fungi are common in the environment and may be part of the normal microbiota of the human skin and gastrointestinal tract.3–5 In addition, Trichosporon spp. are frequently found to cause superficial infections of the skin, nails and hair such as white piedra, a hair shaft infection most prevalent in temperate and subtropical climates.6

Particularly in immunocompromised patients, Trichosporon spp. have garnered increasing attention as a clinically relevant cause of invasive infection with high morbidity and mortality.7,8 Haematological patients with indwelling central venous access devices (CVAD), previous exposure to antimicrobial drugs and prolonged neutropenia are at particular risk.9–15 Besides this well-defined risk-group, other predisposing factors include corticosteroid use and invasive medical procedures such as thoracic and abdominal surgery in critically ill patients.16 The most common manifestation is fungaemia.17 In contrast to candidaemia, approximately half of the reported cases of Trichosporon fungaemia are associated with tissue-invasive manifestations such as metastatic skin lesions, pneumonia, liver and splenic abscesses.17–19

After recent taxonomic revision, the genus Trichosporon now includes 12 species as identified by sequencing of the intergenic spacer 1 (IGS1) ribosomal DNA gene region.20Trichosporon asahii is the major aetiological agent isolated from blood cultures, followed by T. inkin, T. faecale, T. asteroides and T. coremiiforme.2,21,22 In the absence of clinical breakpoints, the results of antifungal susceptibility testing of these yeasts are difficult to interpret. Trichosporon spp. are considered intrinsically resistant to the echinocandins and have variable susceptibility to amphotericin B.21 The difficulties and attendant delay in diagnosis and treatment are illustrated by the high mortality rates of 42% to 87.5% in systemic Trichosporon infections.21,23

The recent guideline from the European Confederation of Medical Mycology (ECMM) in cooperation with the International Society for Human and Animal Mycology (ISHAM) and the American Society for Microbiology (ASM) on the management of invasive Trichosporon infections provides recommendations on multiple diagnostic and therapeutic fronts.2 Complexity of the management of invasive trichosporonosis is reflected in this document, making it a most useful resource for physicians and scientists in a variety of clinical settings. However, these complex recommendations can be difficult to comply with in routine clinical practice.

In 2018, ECMM introduced the first EQUAL score to quantify guideline adherence as a surrogate marker of diagnostic and therapeutic management quality in candidiasis.24 Since then, EQUAL scores have been published for invasive aspergillosis, mucormycosis, cryptococcosis, fusariosis, and scedosporiosis/lomentosporiosis25–29 and have been used in several studies to correlate guideline adherence with patient outcome.24,30–35

To provide a simplified overview of the key recommendations for the management of invasive trichosporonosis, we reviewed the recent guidance document of ECMM, ISHAM and ASM and developed a guideline-based score that highlights the strongest recommendations for patients with invasive Trichosporon infection. The score can be used to assess guideline adherence in daily clinical practice and for future studies, and is intended to support antifungal stewardship.

Methods

The global guideline for the diagnosis and management of rare yeast infections uses the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) method to assess the quality of the evidence (QoE) and determine the strength of recommendations (SoR).2 To design a scoring tool for invasive trichosporonosis, key recommendations were selected, summarized and weighted according to their SoR and QoE.

Each recommendation considered essential to the management of Trichosporon spp. infections was assigned to one of the categories ‘diagnosis’, ‘treatment’ and ‘follow-up’. Additional items that were deemed highly relevant to clinical management but not specifically mentioned in the guideline recommendations were also included and weighted. Score points from 1 to 3 were assigned according to the guidelines grading and clinical importance for a complete workup. A negative value was subtracted from the score when an intervention was not recommended in the corresponding clinical scenario.

Timely, accurate diagnosis directly impacts the prompt and correct initiation of treatment that is paramount in responding to rapidly progressing disease. Therefore, a higher relative weight reflected by a higher point score was assigned to the ‘diagnosis’ category of the score.

Results

The EQUAL Trichosporon Score weighs and aggregates items recommended for optimal management of invasive trichosporonosis. We reviewed recommendations from the current ECMM guideline regarding diagnostic procedures, treatment choices and follow-up procedures for Trichosporon spp. infections.

As with other rare yeasts, diagnosis depends on a combination of diagnostic modalities involving imaging and detection of the organism in clinical specimens (Figure 1). Depending on whether or not organ involvement is present, seven and eight items with a maximum of 18 and 21 points, respectively, were assigned for this category.

Figure 1.

EQUAL Trichosporon Score 2022. (a) Items and score points reflecting guideline recommendations, and (b) the maximum score achievable depending on disease complexity. BT-IFI, breakthrough invasive fungal infection; IGS1, intergenic spacer 1 region.

Recommendations on diagnostic procedures include imaging of suspected sites of involvement to assess the extent of disease. Infectious diseases expert consultation should be an integral component of care for patients with difficult-to-treat invasive fungal infections and is therefore included in the score. Microscopy, blood cultures and cultures from other, presumably sterile material, are the mainstay of microbiological diagnosis in both fungaemia and deep-seated infections. Direct microscopy, including Gram stain, of clinical samples provides rapid and useful diagnostic information. Growth of urease-positive yeast colonies exhibiting arthroconidia and blastoconidia informs the presumptive identification of Trichosporon species. Identification of the fungus down to the species level is advised and should be carried out by molecular techniques such as PCR-based methods, preferably IGS1 sequencing, or MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. There are only limited data indicating that susceptibility can guide effective antifungal therapy. However, susceptibility testing is recommended to provide data for epidemiological surveillance and for the development of epidemiological cut-off values for these fungi. In patients with organ involvement, conventional histopathology of tissue biopsies using standard fungal stains is strongly advised for diagnosis.

For treatment, six general recommendation items were identified with a maximum score of 10 points, with 2 additional points for organ involvement and 1 point for second-line treatment in uncontrolled disease (Figure 1).

Immediate initiation of antifungal treatment and source control such as removal of CVAD or other infected medical devices are recommended. For initial pharmacological treatment, triazole monotherapy is recommended, with voriconazole as first choice and posaconazole as an alternative if breakthrough infection has occurred during voriconazole administration. Combination therapy with azoles and polyenes is poorly supported. Considering the intrinsic resistance of Trichosporon spp. against echinocandins, their use is neither recommended as monotherapy nor in combination with other agents.

Voriconazole and posaconazole serum concentrations have non-linear pharmacokinetics and are further influenced by different host factors. Therefore, plasma drug levels should be measured by therapeutic drug monitoring.36 The duration of pharmacological treatment is empirical and should be individualized depending on the extent of infection, the organs involved, and ongoing immunosuppression. It appears reasonable to continue treatment for 2 weeks after the last negative blood culture in patients with fungaemia only. In disseminated disease with organ involvement, imaging such as PET/CT scan can aid decision-making. Treatment should be continued for at least 4 to 6 weeks and until resolution of clinical and radiological findings.

In patients with tissue-invasive disease that may benefit from removal of infected tissue, adjunctive surgical treatment should be considered. For trichosporonosis, this is particularly relevant in cases with endocarditis or endophthalmitis. In uncontrolled disease under initial triazole monotherapy, second-line treatment should be a combination therapy with azoles and amphotericin B.

Follow-up consists of two items with a maximum of 5 points (Figure 1). Blood cultures should be repeated regularly until negative cultures have been documented for three consecutive days. Follow-up imaging of infected body sites should be performed at appropriate intervals, e.g. weekly for acute and monthly for chronic disease, to monitor organ involvement.

Overall, the EQUAL Trichosporon Score 2022 comprises 18 items (Figure 1). The maximum achievable score ranges from 31 to 39 points and depends on the individual patient course. The score is higher in patients with organ involvement and in those with uncontrolled disease, reflecting more decision points and higher complexity of case management.

Discussion

The EQUAL Trichosporon Score 2022 is an 18 item assessment tool, derived from the current guideline document of ECMM, ISHAM and ASM and also measures quality of care in invasive trichosporonosis. From the guideline, we weighed the strongest recommendations on diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up. The score was created using the same methodology as used for other EQUAL scores25–29,37 and provides an assessment tool for physicians. It will further serve as a basis for studies correlating guideline adherence with patient outcome.

To reduce mortality in hosts at risk, appropriate antifungal prophylaxis is an important tool.38 In contrast to other EQUAL scores,26,37 antifungal prophylaxis was not taken into account in this EQUAL score. Pharmacological prophylaxis measures must be justified from a medical and economic perspective and Trichosporon infections remain too uncommon for specific antifungal prophylaxis recommendations. However, general recommendations for prophylaxis in high-risk patients should be followed.38

The main objective of trichosporonosis management must be to establish the diagnosis promptly and reliably. Incomplete diagnostic work-up, such as delayed testing or failure to order the appropriate assays, can significantly delay correct and immediate treatment initiation.39 Therefore, the EQUAL Trichosporon Score is focused on accurate diagnosis, with the category ‘diagnosis’ accounting for 18 of 31 points without organ involvement and 21 of 38 points in case of organ involvement, respectively.

Consultation of infectious diseases specialists has been shown to improve the outcome of patients with candidaemia and cryptococcosis.40,41 We believe that this also applies to rare yeast infections and have therefore implemented infectious diseases consultation as an integral part of the clinical care of trichosporonosis.

Currently, there are no clinical breakpoints to accurately interpret antifungal MICs for Trichosporon spp.22 Therefore, the results of susceptibility testing must be interpreted cautiously with regard to their clinical significance. However, in vitro susceptibility testing can provide insight into the epidemiology of Trichosporon infections such as the emergence of non-wildtype isolates and may be useful to clinicians in situations where first-line antifungal treatment fails.

Treatment of invasive trichosporonosis is based on three main aspects: Source control such as catheter removal and surgical debridement to reduce fungal burden, systemic antifungal treatment, and control of underlying risk factors such as neutropenia. Timely administration of targeted antifungal therapy is a critical component that impacts on disease outcome, and we therefore assigned an item for immediate initiation of treatment.39 Clinical data have shown that treatment with triazoles improves outcomes in comparison with other regimens.18,42 The superiority of combined therapy over monotherapy in the treatment of trichosporonosis has not been demonstrated. Therefore, it is recommended that combination treatment be reserved for salvage therapy if initial triazole monotherapy fails. Combination therapies with echinocandins and triazoles are discouraged. However, in the absence of randomized clinical trials, therapeutic concepts are mostly based on susceptibility data, animal models and case series. Therefore, the total achievable score for treatment is rather low compared with diagnostics.

One of the main uncertainties pertains to the duration of treatment. It is recommended that treatment should be continued for 2 weeks after documented clearance of Trichosporon spp. from the bloodstream in the absence of metastatic complications, but treatment should be longer in cases with organ involvement. These recommendations are transferred analogously from the management of candidaemia.43 Individualized prolonged therapy may be required.

Judicious follow-up is mandatory as it identifies refractory disease and determines the duration of treatment. Although response assessment is recommended in the current guideline from ECMM, ISHAM and ASM, it does not elaborate on how this should be done. The greatest uncertainties relate to the timing of follow-up imaging and treatment cessation. We therefore added two general recommendations for these invasive infections: (i) blood cultures until negative for three consecutive days; and (ii) weekly or monthly follow-up imaging in cases of acute or chronic organ involvement, respectively. Both aspects are not specifically addressed by studies, but recommendations are based on expert consensus.

The EQUAL Trichosporon Score must only be used with awareness of its limitations. These include the lack of comprehensive clinical trials in this rare disease and thus the lack of high-quality evidence for guideline recommendations. Whether a high score correlates with outcome in the clinical setting needs to be explored. The validity and ultimate utility of the proposed scoring system will be determined by evaluating this correlation in future studies. The score is applicable only in situations where treatment intent is curative and not in patients whose treatment is limited to best supportive care. Finally, new antifungal agents with activity against Trichosporon spp. are in late-stage clinical development.44 The development and approval of novel diagnostic procedures and antifungal agents will require an update of the EQUAL Trichosporon Score to reflect upcoming innovations.

Conclusions

Guidelines are fundamental for evidence-based medicine. Nevertheless, following guidelines can be challenging in daily clinical practice. With the EQUAL Trichosporon Score, we aim to provide treating physicians with a tool for quick and easy assessment. In addition, the score will facilitate antimicrobial stewardship and comparability between health care facilities. It will also provide a basis for future studies evaluating the impact of guideline adherence on patient outcomes.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Sebastian Rahn for technical support with generating the EQUAL Score card.

Funding

This study was carried out as part of our routine work.

Transparency declarations

R.S. and U.B. have nothing to declare. S.C.A.C. reports grants from F2G and MSW Australia, and personal fees from Gilead. O.A.C. reports grants and personal fees from Actelion, personal fees from Allecra Therapeutics, personal fees from Al-Jazeera Pharmaceuticals, grants and personal fees from Amplyx, grants and personal fees from Astellas, grants and personal fees from Basilea, personal fees from Biosys, grants and personal fees from Cidara, grants and personal fees from Da Volterra, personal fees from Entasis, grants and personal fees from F2G, grants and personal fees from Gilead, personal fees from Grupo Biotoscana, personal fees from IQVIA, grants from Janssen, personal fees from Matinas, grants from Medicines Company, grants and personal fees from MedPace, grants from Melinta Therapeutics, personal fees from Menarini, grants and personal fees from Merck/MSD, personal fees from Mylan, personal fees from Nabriva, personal fees from Noxxon, personal fees from Octapharma, personal fees from Paratek, grants and personal fees from Pfizer, personal fees from PSI, personal fees from Roche Diagnostics, grants and personal fees from Scynexis, personal fees from Shionogi, grants from DFG, German Research Foundation, grants from German Federal Ministry of Research and Education, grants from Immunic, outside the submitted work.

References

- 1. Kett DH, Azoulay E, Echeverria PMet al. Candida bloodstream infections in intensive care units: analysis of the extended prevalence of infection in intensive care unit study. Crit Care Med 2011; 39: 665–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chen SC-A, Perfect J, Colombo ALet al. Global guideline for the diagnosis and management of rare yeast infections: an initiative of the ECMM in cooperation with ISHAM and ASM. Lancet Infect Dis 2021; 21: e375–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zhang E, Tanaka T, Tajima Met al. Characterization of the skin fungal microbiota in patients with atopic dermatitis and in healthy subjects. Microbiol Immunol 2011; 55: 625–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cho O, Matsukura M, Sugita T. Molecular evidence that the opportunistic fungal pathogen Trichosporon asahii is part of the normal fungal microbiota of the human gut based on rRNA genotyping. Int J Infect Dis 2015; 39: 87–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pini G, Faggi E, Donato Ret al. Isolation of Trichosporon in a hematology ward. Mycoses 2005; 48: 45–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bonifaz A, Tirado-Sánchez A, Araiza Jet al. White piedra: Clinical, mycological, and therapeutic experience of fourteen cases. Skin Appendage Disord 2019; 5: 135–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Colombo AL, Padovan ACB, Chaves GM. Current knowledge of Trichosporon spp. and Trichosporonosis. Clin Microbiol Rev 2011; 24: 682–700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Shivaprakash MR, Singh G, Gupta Pet al. Extensive white piedra of the scalp caused by Trichosporon inkin: A case report and review of literature. Mycopathologia 2011; 172: 481–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. de Almeida Junior JN, Hennequin C. Invasive Trichosporon infection: a systematic review on a re-emerging fungal pathogen. Front Microbiol 2016; 7: 1629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yong AMY, Yang SS, Tan KBet al. Disseminated cutaneous Trichosporonosis in an adult bone marrow transplant patient. Indian Dermatol Online J 2017; 8: 192–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Alby-Laurent F, Dollfus C, Ait-Oufella Het al. Trichosporon: another yeast-like organism responsible for immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in patients with hematological malignancy. Hematol Oncol 2017; 35: 900–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chaumentin G, Boibieux A, Piens MAet al. Trichosporon inkin endocarditis: short-term evolution and clinical report. Clin Infect Dis 1996; 23: 396–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Milan EP, Silva-Rocha WP, de Almeida JJSet al. Trichosporon inkin meningitis in Northeast Brazil: first case report and review of the literature. BMC Infect Dis 2018; 18: 470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ebright JR, Fairfax MR, Vazquez JA. Trichosporon asahii, a non-Candida yeast that caused fatal septic shock in a patient without cancer or neutropenia. Clin Infect Dis 2001; 33: E28–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. De Hoog GS, Guarro J, Gene Jet al. Atlas of Clinical Fungi. 2nd edn. Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nobrega de Almeida J, Francisco EC, Holguín Ruiz Aet al. Epidemiology, clinical aspects, outcomes and prognostic factors associated with Trichosporon fungaemia: results of an international multicentre study carried out at 23 medical centres. J Antimicrob Chemother 2021; 76: 1907–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Girmenia C, Pagano L, Martino Bet al. Invasive infections caused by Trichosporon species and Geotrichum capitatum in patients with hematological malignancies: a retrospective multicenter study from Italy and review of the literature. J Clin Microbiol 2005; 43: 1818–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Suzuki K, Nakase K, Kyo Tet al. Fatal Trichosporon fungemia in patients with hematologic malignancies. Eur J Haematol 2010; 84: 441–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Viscomi SG, Mortelé KJ, Cantisani Vet al. Fatal, complete splenic infarction and hepatic infection due to disseminated Trichosporon beigelii infection: CT findings. Abdom Imaging 2004; 29: 228–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Liu X-Z, Wang Q-M, Göker Met al. Towards an integrated phylogenetic classification of the Tremellomycetes. Stud Mycol 2015; 81: 85–147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chagas-Neto TC, Chaves GM, Melo ASAet al. Bloodstream infections due to Trichosporon spp.: species distribution, Trichosporon asahii genotypes determined on the basis of ribosomal DNA intergenic spacer 1 sequencing, and antifungal susceptibility testing. J Clin Microbiol 2009; 47: 1074–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dabas Y, Xess I, Kale P. Molecular and antifungal susceptibility study on trichosporonemia and emergence of Trichosporon mycotoxinivorans as a bloodstream pathogen. Med Mycol 2017; 55: 518–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ruan S-Y, Chien J-Y, Hsueh P-R. Invasive trichosporonosis caused by Trichosporon asahii and other unusual Trichosporon species at a medical center in Taiwan. Clin Infect Dis 2009; 49: e11–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mellinghoff SC, Hartmann P, Cornely FBet al. Analyzing candidemia guideline adherence identifies opportunities for antifungal stewardship. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2018; 37: 1563–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cornely OA, Koehler P, Arenz Det al. EQUAL Aspergillosis Score 2018: An ECMM score derived from current guidelines to measure QUALity of the clinical management of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis. Mycoses 2018; 61: 833–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Koehler P, Mellinghoff SC, Lagrou Ket al. Development and validation of the European QUALity (EQUAL) score for mucormycosis management in haematology. J Antimicrob Chemother 2019; 74: 1704–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Guarana M, Nouér SA, Nucci M. EQUAL Fusariosis score 2021: An European Confederation of Medical Mycology score derived from current guidelines to measure QUALity of the clinical management of invasive fusariosis. Mycoses 2021; 64: 1542–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Spec A, Mejia-Chew C, Powderly WGet al. EQUAL Cryptococcus Score 2018: A European Confederation of Medical Mycology Score Derived From Current Guidelines to Measure QUALity of Clinical Cryptococcosis Management. Open Forum Infect Dis 2018; 5: ofy299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Stemler J, Lackner M, Chen SC-Aet al. EQUAL Score Scedosporiosis/Lomentosporiosis 2021: a European Confederation of Medical Mycology (ECMM) tool to quantify guideline adherence. J Antimicrob Chemother 2021; 77: 253–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bal AM. European confederation of medical mycology quality of clinical candidaemia management score: A review of the points based best practice recommendations. Mycoses 2021; 64: 123–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bal AM, Palchaudhuri M. Candidaemia in the elderly: Epidemiology, management and adherence to the European Confederation of Medical Mycology quality indicators. Mycoses 2020; 63: 892–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Budin S, Salmanton-García J, Koehler Pet al. Validation of the EQUAL Aspergillosis Score by analysing guideline-adherent management of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis. J Antimicrob Chemother 2021; 76: 1070–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Huang H-Y, Lu P-L, Wang Y-Let al. Usefulness of EQUAL Candida Score for predicting outcomes in patients with candidaemia: a retrospective cohort study. Clin Microbiol Infect 2020; 26: 1501–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Koehler P, Mellinghoff SC, Stemler Jet al. Quantifying guideline adherence in mucormycosis management using the EQUAL score. Mycoses 2020; 63: 343–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Nemer S, Imtiaz T, Varikkara Met al. Management of candidaemia with reference to the European confederation of medical mycology quality indicators. Infect Dis (Lond) 2019; 51: 527–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hussaini T, Rüping MJGT, Farowski Fet al. Therapeutic drug monitoring of voriconazole and posaconazole. Pharmacotherapy 2011; 31: 214–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mellinghoff SC, Hoenigl M, Koehler Pet al. EQUAL Candida Score: An ECMM score derived from current guidelines to measure QUAlity of Clinical Candidaemia Management. Mycoses 2018; 61: 326–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Mellinghoff SC, Panse J, Alakel Net al. Primary prophylaxis of invasive fungal infections in patients with haematological malignancies: 2017 update of the recommendations of the Infectious Diseases Working Party (AGIHO) of the German Society for Haematology and Medical Oncology (DGHO). Ann Hematol 2018; 97: 197–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Cornely OA, Lass-Flörl C, Lagrou Ket al. Improving outcome of fungal diseases - Guiding experts and patients towards excellence. Mycoses 2017; 60: 420–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Spec A, Olsen MA, Raval Ket al. Impact of Infectious Diseases Consultation on Mortality of Cryptococcal infection in Patients without HIV. Clin Infect Dis 2017; 64: 558–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Patel M, Kunz DF, Trivedi VMet al. Initial management of candidemia at an academic medical center: evaluation of the IDSA guidelines. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2005; 52: 29–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Liao Y, Lu X, Yang Set al. Epidemiology and outcome of Trichosporon fungemia: A review of 185 reported cases from 1975 to 2014. Open Forum Infect Dis 2015; 2: ofv141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Pappas PG, Kauffman CA, Andes DRet al. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Candidiasis: 2016 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2016; 62: e1–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Hoenigl M, Sprute R, Egger Met al. The Antifungal Pipeline: Fosmanogepix, Ibrexafungerp, Olorofim, Opelconazole, and Rezafungin. Drugs 2021; 81: 1703–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]