Abstract

Electron-phonon interaction and related self-energy are fundamental to both the equilibrium properties and non-equilibrium relaxation dynamics of solids. Although electron-phonon interaction has been suggested by various time-resolved measurements to be important for the relaxation dynamics of graphene, the lack of energy- and momentum-resolved self-energy dynamics prohibits direct identification of the role of specific phonon modes in the relaxation dynamics. Here, by performing time- and angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy measurements on Kekulé-ordered graphene with folded Dirac cones at the Γ point, we have succeeded in resolving the self-energy effect induced by the coupling of electrons to two phonons at Ω1 = 177 meV and Ω2 = 54 meV, and revealing its dynamical change in the time domain. Moreover, these strongly coupled phonons define energy thresholds, which separate the hierarchical relaxation dynamics from ultrafast, fast to slow, thereby providing direct experimental evidence for the dominant role of mode-specific phonons in the relaxation dynamics.

Keywords: TrARPES, self-energy, electron-phonon coupling, Kekulé-ordered graphene

High resolution TrARPES measurements of Kekule-ordered graphene resolve the dynamical evolution of electron-phonon interaction in the time domain and reveal the role of specific phonon modes in the ultrafast relaxation dynamics.

INTRODUCTION

Electron-phonon interaction is ubiquitous in solids and fundamental to the transport properties [1,2] as well as the non-equilibrium relaxation dynamics. Electron-phonon interaction determines the electrical resistivity of metals [1,2], affects the electron mobility of semiconductors and drives phase transitions, such as charge density wave [3] and superconductivity [4,5]. Electron-phonon interaction also plays a critical role in the non-equilibrium relaxation dynamics, as has been revealed by various time-resolved optical measurements, where the relaxation rate of electrons is determined by the electron-phonon coupling strength averaged over all phonons [6–9]. In order to further identify whether the relaxation dynamics is dominantly determined by specific phonon modes that are strongly coupled with electrons or contributed by all phonons, it is important to experimentally resolve the self-energy Σ in the time domain and reveal its dynamic evolution. Angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy (ARPES) is a powerful tool for extracting the real and imaginary parts of the self-energy ReΣ and |ImΣ|, which show up in the ARPES data as a renormalization of the electronic dispersion [2] and an increase in the scattering rate near the phonon energy. By combining ARPES with ultrafast pump-probe, time-resolved ARPES (TrARPES) provides unique opportunities for revealing the self-energy effect in the time domain with mode-specific information and establishing a direct connection between the strongly coupled phonons and the relaxation dynamics.

Graphene with low-energy excitations resembling relativistic Dirac fermions [10,11] and strong electron-phonon coupling indicated by the Kohn anomaly [12] is a model system for investigating the electron-phonon interaction in both the equilibrium and non-equilibrium states. The electron-phonon coupling-induced self-energy effect has been resolved in the ARPES measurements of graphene and graphite [13–19] and suggested to be important for the carrier relaxation from time-resolved optical measurements [20–22]. While TrARPES measurements have been performed to reveal the relaxation dynamics of photo-excited carriers [23–35], so far, the electron-phonon coupling-induced self-energy effect and the associated self-energy dynamics have not been resolved in any TrARPES measurement of graphene or graphite. Experimentally, this is limited by the reduced efficiency and resolution of the high harmonic generation (HHG) light source [35–37], which is required for generating a sufficiently high photon energy to probe the Dirac cone at the K point with a large momentum value of 1.7 Å−1.

Here, by taking an experimental strategy of folding the Dirac cones from K to Γ by inducing a  R30° (Fig. 1a) Kekulé order [38,39] through Li intercalation [40–43], we are able to probe the dynamics of Dirac cones using the photon energy of 6.2 eV with greatly improved momentum resolution. This leads to successful identification of coupling of electrons to phonons at Ω1 = 177 meV and Ω2 = 54 meV in both ReΣ and |ImΣ| in the time domain. Moreover, these two strongly coupled phonons dominate the relaxation dynamics of electrons by setting energy thresholds for the hierarchical relaxation dynamics from ultrafast, fast to slow. Our work reveals the dynamical modification of the electron-phonon coupling-induced self-energy effect in the time domain and highlights the dominant role of mode-specific electron-phonon interaction in the non-equilibrium dynamics.

R30° (Fig. 1a) Kekulé order [38,39] through Li intercalation [40–43], we are able to probe the dynamics of Dirac cones using the photon energy of 6.2 eV with greatly improved momentum resolution. This leads to successful identification of coupling of electrons to phonons at Ω1 = 177 meV and Ω2 = 54 meV in both ReΣ and |ImΣ| in the time domain. Moreover, these two strongly coupled phonons dominate the relaxation dynamics of electrons by setting energy thresholds for the hierarchical relaxation dynamics from ultrafast, fast to slow. Our work reveals the dynamical modification of the electron-phonon coupling-induced self-energy effect in the time domain and highlights the dominant role of mode-specific electron-phonon interaction in the non-equilibrium dynamics.

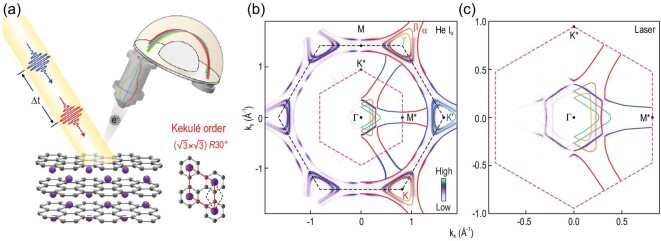

Figure 1.

A schematic of TrARPES and a Fermi surface map of Kekulé-ordered graphene. (a) A schematic of TrARPES on Li-intercalated trilayer graphene with a superlattice period of ( )R30°. The unit cells for graphene and the Kekulé order are labeled with black and red parallelograms. (b) Fermi surface map of the Li-intercalated trilayer graphene measured with a helium lamp source at 21.2 eV. Red and blue curves indicate the largest pockets (α) at K and K′. Smaller pockets β/γ at K and K′ are indicated by yellow and green curves. Black and pink dashed hexagons are graphene and superlattice BZs, respectively. Colored curves around Γ indicate folded pockets from the K and K′ points. (c) Enlarged Fermi surface map using a 6.2 eV laser source. The largest pockets from the K and K′ points are highlighted in red and blue. The pink dashed hexagon is the superlattice BZ with high symmetry points K* and M* labeled.

)R30°. The unit cells for graphene and the Kekulé order are labeled with black and red parallelograms. (b) Fermi surface map of the Li-intercalated trilayer graphene measured with a helium lamp source at 21.2 eV. Red and blue curves indicate the largest pockets (α) at K and K′. Smaller pockets β/γ at K and K′ are indicated by yellow and green curves. Black and pink dashed hexagons are graphene and superlattice BZs, respectively. Colored curves around Γ indicate folded pockets from the K and K′ points. (c) Enlarged Fermi surface map using a 6.2 eV laser source. The largest pockets from the K and K′ points are highlighted in red and blue. The pink dashed hexagon is the superlattice BZ with high symmetry points K* and M* labeled.

RESULTS

The Kekulé-ordered trilayer graphene sample is obtained by intercalating Li into a graphene sample grown on a SiC substrate [40–43], as schematically shown in Fig. S1 of the online supplementary material. The intercalation leads to AA stacking [42] with characteristic dispersion shown in Fig. S2 of the online supplementary material. The  Kekulé order not only leads to a replica of Dirac cones at the Γ point, but also leads to the intervalley coupling and a chiral symmetry breaking induced gap opening [43], which is in analogy to the dynamical mass generation in particle physics. In this work, we focus on the electronic dynamics of the folded Dirac cones at the Γ point of a Li-intercalated trilayer graphene by TrARPES measurements using a 6.2 eV probe laser source operating at a higher repetition rate, which leads to a much higher experimental efficiency and at least a 3 times improvement in the momentum resolution compared to previous TrARPES measurements with a HHG light source (for more information about momentum and time resolution, see the Methods section and Fig. S3 of the online supplementary material). Such improvement is critical for successfully resolving the self-energy effect in the TrARPES measurements.

Kekulé order not only leads to a replica of Dirac cones at the Γ point, but also leads to the intervalley coupling and a chiral symmetry breaking induced gap opening [43], which is in analogy to the dynamical mass generation in particle physics. In this work, we focus on the electronic dynamics of the folded Dirac cones at the Γ point of a Li-intercalated trilayer graphene by TrARPES measurements using a 6.2 eV probe laser source operating at a higher repetition rate, which leads to a much higher experimental efficiency and at least a 3 times improvement in the momentum resolution compared to previous TrARPES measurements with a HHG light source (for more information about momentum and time resolution, see the Methods section and Fig. S3 of the online supplementary material). Such improvement is critical for successfully resolving the self-energy effect in the TrARPES measurements.

Figure 1b shows the Fermi surface map measured by a helium lamp source, which contains three large Fermi pockets (indicated by α, β and γ, and colored curves) with different sizes around each Brillouin zone (BZ) corner (for more information about the Fermi surface map and dispersion image, see Fig. S2 of the online supplementary material). The large pocket size indicates large electron doping induced by the intercalated Li. Folded Dirac cones by the  Kekulé superlattice are observed at the Γ point, similar to previous work [43], and these folded pockets are better resolved in the enlarged Fermi surface map measured by using a laser source with the photon energy of 6.2 eV (Fig. 1c). We note that the Li-intercalated monolayer graphene does not show folded Dirac cones at the Γ point [44], and the Li-intercalated trilayer graphene sample shows a much stronger intensity for the folded pockets at the Γ point than the Li-intercalated bilayer graphene sample [43]. Therefore, a Li-intercalated trilayer graphene sample is used in this TrARPES study. Considering that the Li-intercalated samples are arranged in the AA stacking sequence with weak interlayer coupling, the physics of Li-intercalated trilayer and bilayer graphene is expected to be similar.

Kekulé superlattice are observed at the Γ point, similar to previous work [43], and these folded pockets are better resolved in the enlarged Fermi surface map measured by using a laser source with the photon energy of 6.2 eV (Fig. 1c). We note that the Li-intercalated monolayer graphene does not show folded Dirac cones at the Γ point [44], and the Li-intercalated trilayer graphene sample shows a much stronger intensity for the folded pockets at the Γ point than the Li-intercalated bilayer graphene sample [43]. Therefore, a Li-intercalated trilayer graphene sample is used in this TrARPES study. Considering that the Li-intercalated samples are arranged in the AA stacking sequence with weak interlayer coupling, the physics of Li-intercalated trilayer and bilayer graphene is expected to be similar.

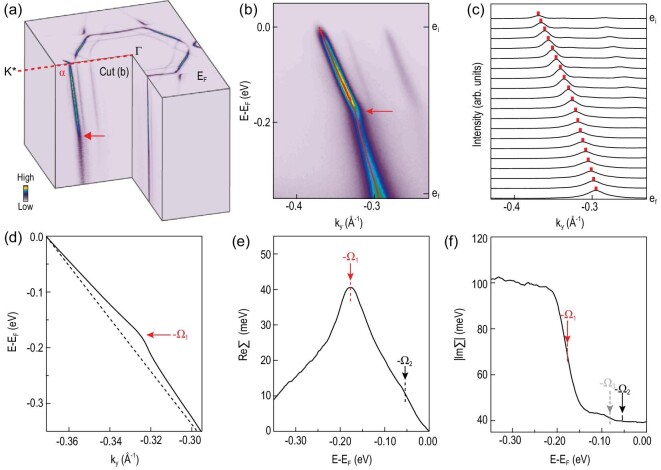

The high-resolution ARPES data allow us to resolve the electron-phonon coupling-induced self-energy effects in the folded Dirac cones at the Γ point. Figure 2a shows the three-dimensional band structure measured by the laser source with sharp dispersions, and a kink (indicated by the red arrow) is observed in the dispersion along the Γ–K* (Γ–M) direction (represented with a red dashed line in Fig. 2a) for the α pocket. The kink is more clearly resolved in the dispersion image in Fig. 2b. By fitting the momentum distribution curves (MDCs) in Fig. 2c, we extract the dispersion (black curve in Fig. 2d) and the peak width, which can be converted into ReΣ and |ImΣ| using standard ARPES analysis [13]. We extract ReΣ by assuming a linear bare band dispersion (dotted line in Fig. 2d). A peak at −Ω1 (red arrow in Fig. 2e) and a shoulder at −Ω2 (black arrow) is observed, which is accompanied by an increase in the scattering rate in |ImΣ| (Fig. 2f), and a possible coupling to an additional phonon at Ω3 (gray arrow) is also observed. Further fitting of the Eliashberg function gives phonon energies of Ω1 = 177 ± 1 meV and Ω2 = 54 ± 4 meV (see the detailed analysis in Fig. S4 of the online supplementary material). We note that electron-phonon coupling has been reported and suggested as important for superconducting CaC6 [17,18] or Li-decorated graphene samples [19,45]. Here, the high data quality of the laser source allows us to resolve fine structures in the self-energy, indicating coupling of electrons to multiple phonons. Such mode-specific electron-phonon interaction lays an important foundation for further investigating the role of these phonons in the relaxation dynamics.

Figure 2.

Electron-phonon coupling-induced self-energy effect. (a) Three-dimensional band structure of the Kekulé-ordered graphene measured using a 6.2 eV laser source. The red arrow indicates the kink, and the red dashed line indicates the Γ–K* (Γ–M) direction. (b) Dispersion image measured along the direction indicated by the red dashed line in (a) before pump excitation. The dispersing band with the strongest intensity is from the largest Fermi surface pocket α. (c) MDCs at energies labeled by ei to ef in (b); the red marks indicate the peak positions from Lorentzian fitting. (d) Extracted dispersion from fitting the MDCs in (c). Black dotted line indicates the bare band dispersion used for extracting ReΣ in (e). (e) and (f) Extracted ReΣ and |ImΣ| reveal the coupling of electrons with phonons at energies Ω1 = 177 and Ω2 = 54 meV, and Ω3 = 82 meV (gray arrow).

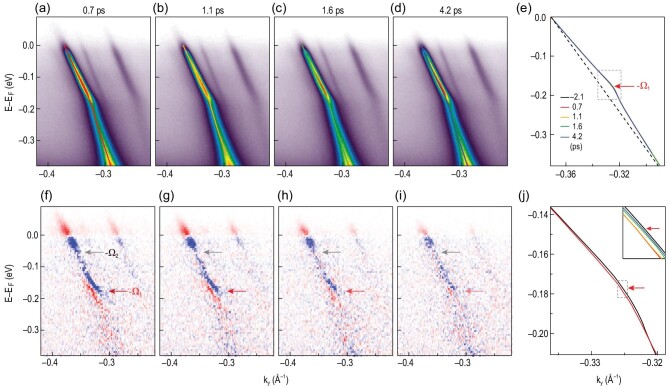

The electron dynamics is revealed by comparing dispersion images measured at different delay times with a pump photon energy of 1.55 eV at a pump fluence of 215 μJ/cm2. Figure 3a–d shows dispersion images measured at 0.7, 1.1, 1.6 and 4.2 ps after pump excitation, respectively, and the extracted dispersions at different delay times are plotted in Fig. 3e. After subtracting the dispersion image measured at -2.1 ps, the spectral weight redistribution is clearly resolved in the differential images shown in Fig. 3f–i. An increase in intensity above EF is clearly resolved (highlighted in red), indicating photo-excited electrons above EF. In addition, a suppression of intensity below EF indicates photo-excited holes below EF (highlighted in blue). In contrast to previous TrARPES studies where the TrARPES signal was widely spread out in a large energy range of approximately 1 eV [23–30,32], our TrARPES signal is mostly confined in a much smaller energy range within 177 meV (indicated by red arrows) with a much stronger TrARPES signal observed

Figure 3.

TrARPES dispersion images measured at different delay times after pumping at a pump fluence of 215 μJ/cm2. (a)–(d) Evolution of the dispersion images measured at different delay times. (e) Extracted dispersion at different delay times. (f)–(i) Differential images obtained by subtracting dispersion images measured at −2.1 ps from (a)–(d). Red and blue pixels respectively represent the increase and decrease in intensity. Red and gray arrows indicate the threshold effect at −Ω1 and −Ω2 energies. (j) Enlargement of the extracted dispersions (indicated by the gray dotted box in (e)) to show a comparison between the dispersions at 0.7 ps (red curve) and −2.1 ps (black curve). The inset displays the enlarged dispersion (over the gray dotted box in (j)) at different delay times to show the dynamic evolution of the kink. Red arrows indicate an energy of −Ω1.

within 54 meV (gray arrows), indicating the energy threshold effect in the TrARPES signal and the relaxation dynamics. Such an energy threshold effect with TrARPES signal confined within 177 meV is ubiquitous across the entire BZ (for more data in a larger momentum space, see Fig. S5 of the online supplementary material). In addition, the differential images in Fig. 3f–i show an unusual fine feature indicated by red arrows around −Ω1 with an increase in intensity (highlighted in red) at the negative side of the peak and a decrease in intensity at the positive side (highlighted in blue), indicating a modification to the dispersions measured at different delay times. The enlarged dispersions in Fig. 3j further reveal the dynamical modification of the dispersion near the kink energy at different delay times (see Fig. S6 of the online supplementary material for a detailed analysis of the self-energy at −2.1 ps and 0.7 ps). At later delay times, the dispersion almost recovers (see the comparison between the blue curve at 4.2 ps and the black curve at −2.1 ps in the inset of Fig. 3j).

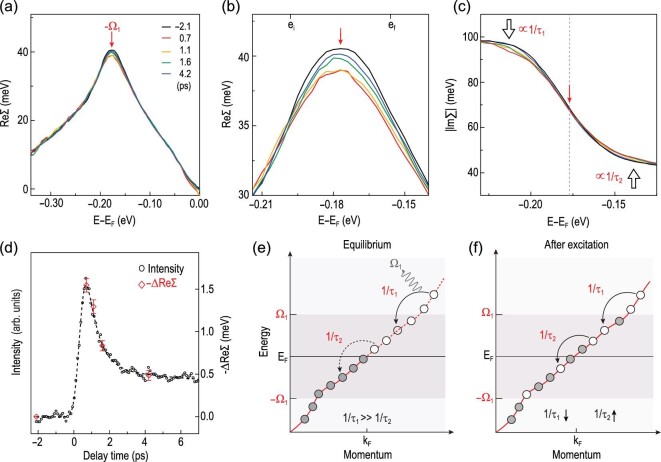

To further reveal the underlying physics behind the dynamical change of the dispersion in the time domain, we show in Fig. 4 an analysis of ReΣ and |ImΣ| at different delay times. A decrease in the peak is observed in ReΣ in Fig. 4a and in the enlarged ReΣ near the kink energy in Fig. 4b, which gradually recovers at a later delay time (from orange to blue curves in Fig. 4b). A corresponding change is also observed in |ImΣ| (see the black open arrows in Fig. 4c), which is related to ReΣ by the Kramers–Kronig relationship (see Fig. S7 of the online supplementary material for more details about the dynamical change of self-energy at difference delay times). To check if the electron-phonon coupling-induced self-energy effect is correlated with the pump-induced spectral weight transfer revealed in Fig. 3f–i, we show in Fig. 4d a comparison between the temporal evolution of the pump-induced change in the self-energy −ΔReΣ (red symbol) and the electron population above EF that is obtained by integrating the TrARPES intensity from 0 to 50 meV (black symbols and dotted curve). The same temporal evolution suggests a correlation between the dynamical self-energy and the pump-induced spectral weight redistribution and the corresponding change in the scattering phase space [46,47]. In the equilibrium state (Fig. 4e), the scattering rate for electrons (holes) inside the phonon energy window (±Ω1, 0), 1/τ2, is much less than that outside this window, 1/τ1, due to insufficient energy to emit a phonon at Ω1, as indicated by the jump in |ImΣ| (Fig. 2f). Upon pump excitation, electrons are populated above the Fermi energy EF and holes below EF (indicated by gray and white circles on the red curve in Fig. 4f); therefore, the scattering rate for holes (or electrons) inside the phonon window (1/τ2) increases due to an increase in the scattering phase space to scatter into, while outside the phonon window (1/τ1) it decreases. Such a change in the scattering rate by the photon-induced spectral weight redistribution leads to a dynamical modification of |ImΣ| in Fig. 4c and ReΣ in Fig. 4b, implying the significant role of the phonons that are coupled to electrons. We note that a dynamical change in the self-energy has been reported in a high-temperature BSCCO superconductor, especially in the superconducting state [48–50]. Here we report the first observation of dynamical change in the self-energy in a non-superconducting material.

Figure 4.

Self-energy dynamics and carrier relaxation dynamics. (a) Extracted ReΣ at different delay times. (b) Enlargement of ReΣ to show the dynamical change of ReΣ around −Ω1 (red arrow). (c) Extracted |ImΣ| at different delay times to show the renormalization of the scattering rate around −Ω1 after pump excitation, as indicated by black open arrows. (d) A comparison between the pump-induced decrease in −ReΣ as a function of the delay time (red symbols, obtained by averaging −ReΣ over the energy range (ei to ef) indicated by black short marks in (b)) and the pump-induced population (black symbols and dotted curve) obtained by integrating from 0 to 50 meV above the Fermi energy. (e) and (f) Schematics of the electron redistribution after pump excitation and the related renormalization of the scattering rate 1/τ for holes (or electrons) inside and outside the phonon window, which gives the dynamical change of the self-energy around the phonon energy. Gray and white circles represent electrons and holes, respectively.

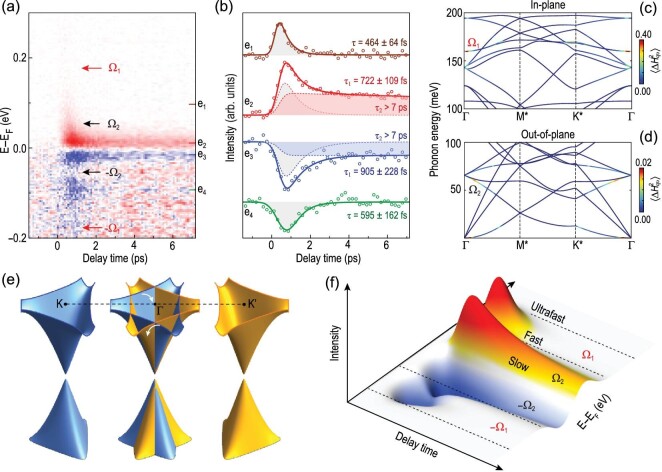

The electron-phonon interaction not only modifies the self-energy in the time domain but also sets energy thresholds, as indicated by the red and gray arrows in Fig. 3f–i, and its relation to the relaxation dynamics is further revealed in Fig. 5. The temporal evolution as a function of energy and delay time (Fig. 5a) and the selected curves at different energies (Fig. 5b) reveal hierarchical relaxation times in different energy windows defined by the two strongly coupled phonons, which are summarized below: (1) for energy windows ±(∞, Ω1) in which photo-excited carriers have sufficient energy to emit phonons with energies of Ω1 and Ω2, the relaxation is ‘ultrafast’—faster than 337 fs (see Fig. S8 of the online supplementary material for a detailed analysis of energy-dependent relaxation time) and there is negligible TrARPES signal; (2) for energy windows ±(Ω1, Ω2) in which photo-excited carriers can emit phonons at Ω2 but not Ω1, the relaxation is ‘fast’, within a few hundred femtoseconds (curves at e1 and e4 in Fig. 5b); (3) for energy windows ±(Ω2, 0) in which the relaxation requires involvement of acoustic phonons at even lower energy, the relaxation is ‘slow’ with an additional component persisting beyond 7 ps (highlighted as red and blue shaded regions for curves e2 and e3 in Fig. 5b) that involves relaxation through another mechanism, e.g. acoustic phonons. The observation of distinct relaxation time scales in different energy regimes ±(∞, Ω1), ±(Ω1, Ω2) and ±(Ω2, 0) establishes a direct correlation between the hierarchical relaxation times and the two strongly coupled phonons at ±(Ω1, 0) and ±(Ω2, 0). Therefore, our results show that the coupled phonons at Ω1 and Ω2 play a dominant role in the relaxation of electrons in graphene. Theoretical calculations of the phonon dispersion and electron-phonon coupling strength for the Li-intercalated graphene (see the online supplementary material for details of the calculation and Fig. S9 therein for more data) have identified that the two phonons at Ω1 and Ω2 that are coupled to electrons and thereby dominate the relaxation dynamics are the in-plane TO phonon A1g (Fig. 5c) and the out-of-plane ZA phonon (Fig. 5d).

Figure 5.

Phonon threshold effect and hierarchical relaxation of electrons in different energy windows. (a) Evolution of momentum-integrated differential intensity with energy and delay time. Red and blue pixels respectively represent the increase and decrease in intensity. (b) Differential intensity as a function of the delay time at energies indicated by colored tick marks in (a). Solid curves are fitting results. Gray shaded regions in e1–e4 indicate the fast relaxation, while red and blue shaded regions in e2 and e3 represent the slow relaxation component. (c) and (d) Calculated phonon dispersion and electron-phonon coupling strength of Li-intercalated graphene for in-plane and out-of-plane phonon modes, respectively. (e) Schematics of electron-phonon coupling in the Li-intercalated graphene. (f) Schematic of the phonon threshold effect with hierarchical relaxation.

CONCLUSION

To summarize, by strategically folding the Dirac cones to Γ (Fig. 5e), high-resolution TrARPES measurements allow us to visualize the coupling of electrons to two strongly coupled phonon modes in the time domain. The coupling of electrons with multiple phonons sets energy windows for electron relaxation with hierarchical relaxation dynamics, as schematically illustrated in Fig. 5f. Moreover, the change in the electron self-energy suggests a dynamical modification of coupling between electrons and phonons, and provides important information for considering the non-equilibrium electron-boson interactions in other systems. Our work not only provides direct experimental evidence for the dominant role of mode-specific phonons in the relaxation dynamics of Kekulé-ordered graphene, but also provides a new material platform for exploring the engineering of Dirac cones by light-matter interaction.

METHODS

Sample preparation

Bilayer graphene was grown by flash annealing the Si face of 6H-SiC(0001) substrates in ultrahigh vacuum. Lithium intercalation was performed by in situ deposition of Li from an alkali metal dispenser (SAES), with the graphene sample maintained at 320 K [43]. The intercalation process was monitored by low-energy electron diffraction and ARPES measurements. The intercalation releases the buffer layer [44] underneath the bilayer graphene, eventually resulting in Kekulé-ordered trilayer graphene with Li atoms inserted between the graphene layers.

TrARPES measurements

TrARPES measurements were performed in the home laboratory at Tsinghua University at 80 K in a working vacuum better than 6 × 10−11 Torr. The pump photon energy was 1.55 eV and the pump fluence was set to 215 μJ/cm2. A pulsed laser source at 6.2 eV with a repetition rate of 3.8 MHz was used as the probe source. The overall time resolution was set to 480 fs. The Fermi edge of the graphene sample measured at 80 K showed an energy width of 33 meV, from which the overall instrumental energy resolution was extracted to be 16 meV after removing the thermal broadening (for more details, see Fig. S1 of the online supplementary material). Moreover, the reduction of photon energy compared to HHG also leads to major improvement in the momentum resolution. Since the momentum resolution at the Fermi energy EF is  , where hν and φ ≈ 4.3 eV are the photon energy and work function, respectively, the reduction in photon energy from hν ≥ 25 to 6.2 eV leads to at least a 3 times improvement in Δk, with an ultimate experimental resolution of Δk = 0.001 Å−1. The greatly improved energy and momentum resolution together with the high data acquisition efficiency are critical to the successful observation of the electron-phonon coupling-induced kink in the TrARPES data and the phonon threshold effect.

, where hν and φ ≈ 4.3 eV are the photon energy and work function, respectively, the reduction in photon energy from hν ≥ 25 to 6.2 eV leads to at least a 3 times improvement in Δk, with an ultimate experimental resolution of Δk = 0.001 Å−1. The greatly improved energy and momentum resolution together with the high data acquisition efficiency are critical to the successful observation of the electron-phonon coupling-induced kink in the TrARPES data and the phonon threshold effect.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Hongyun Zhang, State Key Laboratory of Low-Dimensional Quantum Physics and Department of Physics, Tsinghua University, Beijing 100084, China.

Changhua Bao, State Key Laboratory of Low-Dimensional Quantum Physics and Department of Physics, Tsinghua University, Beijing 100084, China.

Michael Schüler, Stanford Institute for Materials and Energy Sciences (SIMES), SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, Menlo Park, CA 94025, USA.

Shaohua Zhou, State Key Laboratory of Low-Dimensional Quantum Physics and Department of Physics, Tsinghua University, Beijing 100084, China.

Qian Li, State Key Laboratory of Low-Dimensional Quantum Physics and Department of Physics, Tsinghua University, Beijing 100084, China.

Laipeng Luo, State Key Laboratory of Low-Dimensional Quantum Physics and Department of Physics, Tsinghua University, Beijing 100084, China.

Wei Yao, State Key Laboratory of Low-Dimensional Quantum Physics and Department of Physics, Tsinghua University, Beijing 100084, China.

Zhong Wang, Institute for Advanced Study, Tsinghua University, Beijing 100084, China.

Thomas P Devereaux, Stanford Institute for Materials and Energy Sciences (SIMES), SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, Menlo Park, CA 94025, USA; Department of Materials Science and Engineering, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94035, USA.

Shuyun Zhou, State Key Laboratory of Low-Dimensional Quantum Physics and Department of Physics, Tsinghua University, Beijing 100084, China; Frontier Science Center for Quantum Information, Beijing 100084, China.

FUNDING

This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (11427903 and 11725418), the National Key R&D Program of China (2020YFA0308800 and 2016YFA0301004), the Tsinghua University Initiative Scientific Research Program and the Tohoku-Tsinghua Collaborative Research Fund, Beijing Advanced Innovation Center for Future Chip (ICFC). M.S. and T.P.D. acknowledge financial support from the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), Office of Basic Energy Sciences, Division of Materials Sciences and Engineering, under Contract No. DE-AC02-76SF00515. M.S. thanks the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation for its support with a Feodor Lynen scholarship.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

S.Z. conceived the research project. H.Z., C.B., S.Z., Q.L. and L.L. performed the TrARPES measurements and analyzed the data. C.B., L.L. and W.Y. grew the graphene samples. M.S. and T.P.D. performed the calculations. Z.W. involved in the discussion of the theoretical explanations. H.Z. and S.Z. wrote the manuscript, and all authors commented on the manuscript.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1. Sham LJ, Ziman JM. The electron-phonon interaction. Solid State Phys 1963; 15: 221–98. 10.1016/S0081-1947(08)60593-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ashcroft NW, Mermin ND. Solid State Physics. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Grüner G. The dynamics of charge-density waves. Rev Mod Phys 1988; 60: 1129–81. 10.1103/RevModPhys.60.1129 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bardeen J, Cooper LN, Schrieffer JR. Theory of superconductivity. Phys Rev 1957; 108: 1175–204. 10.1103/PhysRev.108.1175 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5. McMillan WL. Transition temperature of strong-coupled superconductors. Phys Rev 1968; 167: 331–44. 10.1103/PhysRev.167.331 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Elsayed-Ali HE, Norris TB, Pessot MAet al. Time-resolved observation of electron-phonon relaxation in copper. Phys Rev Lett 1987; 58: 1212–5. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.58.1212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Schoenlein RW, Lin WZ, Fujimoto JG. Femtosecond studies of nonequilibrium electronic processes in metals. Phys Rev Lett 1987; 58: 1680–3. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.58.1680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Allen PB. Theory of thermal relaxation of electrons in metals. Phys Rev Lett 1987; 59: 1460–3. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.59.1460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Brorson SD, Kazeroonian A, Moodera JSet al. Femtosecond room-temperature measurement of the electron-phonon coupling constant γ in metallic superconductors. Phys Rev Lett 1990; 64: 2172–5. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.64.2172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Geim AK. Graphene: status and prospects. Science 2009; 324: 1530–4. 10.1126/science.1158877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Neto AHC, Guinea F, Peres NMRet al. The electronic properties of graphene. Rev Mod Phys 2009; 81: 109–62. 10.1103/RevModPhys.81.109 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Piscanec S, Lazzeri M, Mauri Fet al. Kohn anomalies and electron-phonon interactions in graphite. Phys Rev Lett 2004; 93: 185503. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.93.185503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zhou SY, Siegel DA, Fedorov AVet al. Kohn anomaly and interplay of electron-electron and electron-phonon interactions in epitaxial graphene. Phys Rev B 2008; 78: 193404. 10.1103/PhysRevB.78.193404 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14. McChesney JL, Bostwick A, Ohta Tet al. Extended van Hove singularity and superconducting instability in doped graphene. Phys Rev Lett 2010; 104: 136803. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.104.136803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fedorov AV, Verbitskiy NI, Haberer Det al. Observation of a universal donor-dependent vibrational mode in graphene. Nat Commun 2014; 5: 3257. 10.1038/ncomms4257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Margine ER, Lambert H, Guistino F. Electron-phonon interaction and pairing mechanism in superconducting Ca-intercalated bilayer graphene. Sci Rep 2016; 6: 21414. 10.1038/srep21414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Valla T, Camacho J, Pan ZHet al. Anisotropic electron-phonon coupling and dynamical nesting on the graphene sheets in superconducting CaC6 using angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy. Phys Rev Lett 2009; 102: 107007. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.102.107007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yang SL, Sobota JA, Howard CAet al. Superconducting graphene sheets in CaC6 enabled by phonon-mediated interband interactions. Nat Commun 2014; 5: 3493. 10.1038/ncomms4493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ludbrook BM, Levy G, Nigge Pet al. Evidence for superconductivity in Li-decorated monolayer graphene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2015; 112: 11795–9. 10.1073/pnas.1510435112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kampfrath T, Perfetti L, Schapper Fet al. Strongly coupled optical phonons in the ultrafast dynamics of the electronic energy and current relaxation in graphite. Phys Rev Lett 2005; 95: 187403. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.95.187403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Winnerl S, Orlita M, Plochocka Pet al. Carrier relaxation in epitaxial graphene photoexcited near the Dirac point. Phys Rev Lett 2011; 107: 237401. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.107.237401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Breusing M, Kuehn S, Winzer Tet al. Ultrafast nonequilibrium carrier dynamics in a single graphene layer. Phys Rev B 2011; 83: 153410. 10.1103/PhysRevB.83.153410 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gierz I, Petersen JC, Mitrano Met al. Snapshots of non-equilibrium Dirac carrier distributions in graphene. Nat Mater 2013; 12: 1119–24. 10.1038/nmat3757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Johannsen JC, Ulstrup S, Cilento Fet al. Direct view of hot carrier dynamics in graphene. Phys Rev Lett 2013; 111: 027403. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.111.027403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Johannsen JC, Ulstrup S, Crepaldi Aet al. Tunable carrier multiplication and cooling in graphene. Nano Lett 2015; 15: 326–31. 10.1021/nl503614v [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gierz I, Calegari F, Aeschlimann Set al. Tracking primary thermalization events in graphene with photoemission at extreme time scales. Phys Rev Lett 2015; 115: 086803. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.115.086803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gierz I, Link S, Starke Uet al. Non-equilibrium Dirac carrier dynamics in graphene investigated with time- and angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy. Faraday Discuss 2014; 171: 311–21. 10.1039/C4FD00020J [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ulstrup S, Johannsen JC, Cilento Fet al. Ultrafast dynamics of massive Dirac fermions in bilayer graphene. Phys Rev Lett 2014; 112: 257401. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.112.257401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gierz I, Mitrano M, Bromberger Het al. Phonon-pump extreme-ultraviolet-photoemission probe in graphene: anomalous heating of Dirac carriers by lattice deformation. Phys Rev Lett 2015; 114: 125503. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.114.125503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Aeschlimann S, Krause R, Chávez-Cervantes Met al. Ultrafast momentum imaging of pseudospin-flip excitations in graphene. Phys Rev B 2017; 96: 020301(R). 10.1103/PhysRevB.96.020301 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pomarico E, Mitrano M, Bromberger Het al. Enhanced electron-phonon coupling in graphene with periodically distorted lattice. Phys Rev B 2017; 95: 024304. 10.1103/PhysRevB.95.024304 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Someya T, Fukidome H, Watanabe Het al. Suppression of supercollision carrier cooling in high mobility graphene on SiC(0001). Phys Rev B 2017; 95: 165303. 10.1103/PhysRevB.95.165303 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Caruso F, Novko D, Draxl Cet al. Photoemission signatures of nonequilibrium carrier dynamics from first principles. Phys Rev B 2020; 101: 035128. 10.1103/PhysRevB.101.035128 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rohde G, Stange A, Müller Aet al. Ultrafast formation of a Fermi-Dirac distributed electron gas. Phys Rev Lett 2018; 121: 256401. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.121.256401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Na MX, Mills AK, Boschini Fet al. Direct determination of mode-projected electron-phonon coupling in the time domain. Science 2019; 366: 1231–6. 10.1126/science.aaw1662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sie EJ, Rohwer T, Lee Cet al. Time-resolved XUV ARPES with tunable 24-33 eV laser pulses at 30 meV resolution. Nat Commun 2019; 10: 3535. 10.1038/s41467-019-11492-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Rohwer T, Hellmann S, Wiesenmayer Met al. Collapse of long-range charge order tracked by time-resolved photoemission at high momenta. Nature 2011; 471: 490–3. 10.1038/nature09829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chamon C. Solitons in carbon nanotubes. Phys Rev B 2000; 62: 2806–12. 10.1103/PhysRevB.62.2806 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Cheianov VV, Fal’ko VI, Syljuäsen Oet al. Hidden Kekulé ordering of adatoms on graphene. Solid State Commun 2009; 149: 1499–501. 10.1016/j.ssc.2009.07.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Virojanadara C, Watcharinyanon S, Zakharov AAet al. Epitaxial graphene on 6H-SiC and Li intercalation. Phys Rev B 2010; 82: 205402. 10.1103/PhysRevB.82.205402 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sugawara K, Kanetani K, Sato Tet al. Fabrication of Li-intercalated bilayer graphene. AIP Adv 2011; 1: 022103. 10.1063/1.3582814 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Caffrey NM, Johansson LI, Xia Cet al. Structural and electronic properties of Li-intercalated graphene on SiC(0001). Phys Rev B 2016; 93: 195421. 10.1103/PhysRevB.93.195421 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bao C, Zhang H, Zhang Tet al. Experimental evidence of chiral symmetry breaking in Kekulé-ordered graphene. Phys Rev Lett 2021; 126: 206804. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.126.206804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Bisti F, Profeta G, Vita Het al. Electronic and geometric structure of graphene/SiC(0001) decoupled by lithium intercalation. Phys Rev B 2015; 91: 245411. 10.1103/PhysRevB.91.245411 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Profeta G, Calandra M, Mauri F. Phonon-mediated superconductivity in graphene by lithium deposition. Nat Phys 2012; 8: 131–4. 10.1038/nphys2181 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Sentef M, Kemper AF, Moritz Bet al. Examining electron-boson coupling using time-resolved spectroscopy. Phys Rev X 2013; 3: 041033. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kemper AF, Sentef MA, Moritz Bet al. Effect of dynamical spectral weight redistribution on effective interactions in time-resolved spectroscopy. Phys Rev B 2014; 90: 075126. 10.1103/PhysRevB.90.075126 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Zhang W, Hwang C, Smallwood CLet al. Ultrafast quenching of electron-boson interaction and superconducting gap in a cuprate. Nat Commun 2014; 5: 4959. 10.1038/ncomms5959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ishida Y, Saitoh T, Mochiku Tet al. Quasi-particles ultrafastly releasing kink bosons to form Fermi arcs in a cuprate superconductor. Sci Rep 2016; 6: 18747. 10.1038/srep18747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Hwang C, Zhang W, Kurashima Ket al. Ultrafast dynamics of electron-phonon coupling in a metal. Europhys Lett 2019; 126: 57001. 10.1209/0295-5075/126/57001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.