Abstract

Different methods of extraction of bacterial DNA from bovine milk to improve the direct detection of Brucella by PCR were evaluated. We found that the use of a lysis buffer with high concentrations of Tris, EDTA, and NaCl, high concentrations of sodium dodecyl sulfate and proteinase K, and high temperatures of incubation was necessary for the efficient extraction of Brucella DNA. The limit of detection by PCR was 5 to 50 Brucella CFU/ml of milk.

Brucella spp. are gram-negative bacteria which cause brucellosis, a widespread zoonosis. The economic importance of brucellosis requires the use of sensitive and rapid diagnosis methods. At present, diagnosis of brucellosis in live dairy cattle involve either the isolation of Brucella from milk samples or the detection of anti-Brucella antibodies in serum or milk (1). However, these methods are not wholly satisfactory. Bacteriological isolation is a time-consuming procedure, and handling the microorganism is hazardous. Serological methods are not conclusive, because not all infected animals produce significant levels of antibodies and because cross-reactions with other bacteria can give false-negative results (1). Some previous studies have demonstrated that PCR can be used to detect Brucella DNA in milk samples (4, 7, 10, 12). PCR-based methods have the potential to be fast, accurate, and efficient in detecting Brucella. However, when PCR was applied to milk samples, its sensitivity was low with respect to bacterial culture, and some false-negative PCR results have been reported (10). The difficulty associated with lysing the microorganisms could account, at least in part, for the failure of the PCR assay in samples that were culture positive. To deal with this problem, we compared different methods of extraction of bacterial DNA from bovine milk to improve the direct detection of Brucella by PCR. The results are described in this paper.

Sterile bovine milk was inoculated with Brucella abortus 2308 to 2 × 105 CFU/ml, and serial dilutions were prepared in milk to determine the limit of detection (expressed as CFU per milliliter) of the PCR. Different modifications of the DNA extraction method previously described (10) were used. Frozen milk was thawed at room temperature, and 500 μl of sample was mixed with 100 μl of TE buffer (1 mM EDTA, 10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.6]) or NET buffer (50 mM NaCl, 125 mM EDTA, 50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.6]). Different combinations of denaturing agents were added: 50 μl of 2.6 N NaOH solution, 100 μl of 24% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) (final concentration, 3.4%), or 100 μl of 10% Zwittergent 3-14 detergent (Zw 3-14 [Calbiochem-Behring Corp.]; final concentration, 1.4%). The mixture was cooled on ice after incubation at room temperature or 80 or 100°C for 10 min. Different combinations of enzymatic conditions were tested: proteinase K (Sigma Chemical Co.; final concentration, 162, 325, or 650 μg/ml) at 37 or 50°C for 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 2.5, or 3 h; lysozyme (Sigma; final concentration, 162, 325, 650, 1,300, or 2,600 μg/ml) at 37°C for 1 h; or RNase (ICN Pharmaceuticals Inc.; final concentration, 19, 37, 75, 150, or 300 μg/ml) at 50°C for 0.25, 0.5, 1, 1.5, or 2 h. In some experiments, cell debris were removed by precipitation with 5 M NaCl and hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide-NaCl (CTAB-NaCl) solution at 65°C for 10 min (13). DNA was extracted by standard methods with phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol, precipitated with isopropanol, washed with ethanol, and dried under vacuum (11). The DNA pellet was dissolved in 25 μl of sterile distilled water and stored at −20°C until further use. A 1-μl volume of this DNA solution was added to the PCR cocktail. Alternatively, DNA was extracted from the mixture after the incubation with proteinase K and RNase by using the Instagene (Bio-Rad Laboratories) or the Prep-A-Gene (Bio-Rad Laboratories) system as specified by the manufacturer. A final purification step with Sephacryl S-300 or S-500 (Pharmacia Biotech) was also assayed. A total of 25 μl of purified DNA was added to 200 μl of a 50% (vol/vol) solution of Sephacryl S-300 or S-500 in distilled water, and the mixture was incubated at room temperature for 10 min. After centrifugation (13,000 × g for 5 min), the supernatant was used for PCR. In all experiments, one sample of sterile milk was included as internal negative control. Amplification and detection of Brucella DNA by PCR was performed with primers F4 and R2 as described previously (9, 10). In all PCR assays, a positive control (B. abortus 2308 DNA) and a negative control (sterile water) were included. Generally recommended procedures were used to avoid contamination (8).

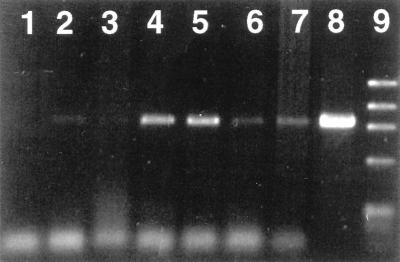

The effects of temperature and the type of denaturing treatment (SDS or Zw 3-14 detergents in NET or TE buffer) on the PCR results were studied. In these experiments, the extraction of DNA was followed by digestion with proteinase K (325 μg/ml at 50°C for 2 h) without RNase treatment. A positive PCR result was obtained only when the DNA extraction was performed with SDS in NET buffer (Fig. 1), and more reproducible amplifications were achieved when the sample was incubated at 80°C. The effect of NaOH as a denaturing agent was also tested in NET buffer with or without SDS. The amplification in the presence of NaOH always resulted in fainter bands (Fig. 1). In addition, digestion with lysozyme did not improve the amplification even at the highest concentration tested (data not shown). Therefore, all subsequent DNA extractions were performed with NET buffer and SDS at 80°C.

FIG. 1.

Effect of lysis buffer composition and denaturing agent on the detection of Brucella DNA by PCR. Samples in lanes 2 to 7 were sterile bovine milk inoculated with B. abortus (2 × 105 CFU/ml). Lanes: 1, negative control without DNA; 2 and 3, DNA extracted with SDS and TE buffer; 4 and 5, DNA extracted with SDS and NET buffer; 6 and 7, DNA extracted with SDS, NaOH, and NET buffer; 8, positive control with B. abortus DNA; 9, φX174 DNA/HaeIII marker (Boehringer Mannheim). The lysis incubation temperature was 80°C in lanes 2, 4, and 6, and 100°C in lanes 3, 5, and 7. The size of the amplification product is about 905 bp. No amplification was detected when Zw 3-14 was used instead of SDS (data not shown).

The effects of the treatment with proteinase K and RNase at various concentrations on the PCR results were also studied. No differences were found when proteinase K was added to a final concentration of 325 or 650 μg/ml, but the amplification was weak when smaller amounts of the enzyme were added (data not shown). The best results were obtained when the incubation was carried out for at least 1.5 h. Incubation temperatures of 37 and 50°C did not give different results. Similar experiments were repeated, including an RNase incubation step prior to treatment with proteinase K. A stronger and more reproducible amplification was achieved when the sample was incubated with 75 μg of RNase per ml at 50°C for 2 h (data not shown). Increasing the enzyme concentration further did not change the efficiency of the amplification. Therefore, all subsequent experiments included digestion with RNase (75 μg/ml) followed by incubation with proteinase K (325 μg/ml), both at 50°C.

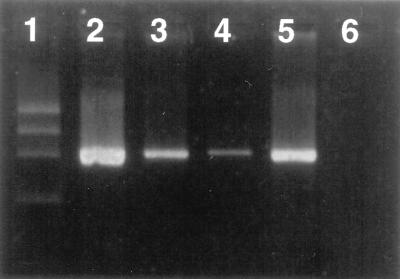

The effect of removal of cell debris by precipitation with CTAB-NaCl on PCR performance was also tested. Our results demonstrated that this treatment was not critical (data not shown). In addition, to avoid excessive manipulation of the sample, the possibility of replacing the standard DNA extraction method by commercial systems was studied. When the Instagene system was used the amplification was always weaker. However, the amplification signal obtained with the Prep-A-Gene system was similar to the one obtained with the standard method (Fig. 2), but the results were less reproducible. To remove possible PCR inhibitors present in the DNA, a final purification step with Sephacryl S-300 or S-500 was also tested. The results of the PCR obtained after these treatments were always negative (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Effect of the DNA extraction with commercial systems on the detection of Brucella DNA by PCR. Samples in lanes 3 to 5 were sterile bovine milk inoculated with B. abortus (2 × 105 CFU/ml). Lanes: 1, φX174 DNA/HaeIII marker (Boehringer Mannheim); 2, positive control with B. abortus DNA; 3, DNA extracted with the Prep-A-Gene system; 4, DNA extracted with the Instagene system; 5, DNA extracted with phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol; 6, negative control without DNA.

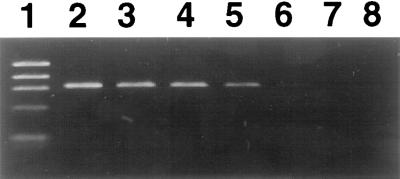

We also determined the limit of PCR detection of Brucella DNA purified by the optimized method under our conditions (NET buffer, SDS at 80°C, digestion with RNase and proteinase K at 50°C, and organic extraction). Sterile bovine milk was inoculated with a known concentration of Brucella and subsequently processed for PCR amplification and culture. A positive PCR result was always obtained with different aliquots containing at least 50 CFU/ml of milk (Fig. 3). However, the amplification signal was obtained in only 50% of the aliquots containing 5 CFU/ml of milk.

FIG. 3.

Limit of detection of PCR. Lanes: 1, φX174 DNA/HaeIII marker (Boehringer Mannheim); 2 to 4, 50 B. abortus CFU/ml of milk; 5 to 7, 5 B. abortus CFU/ml of milk; 8, negative control without DNA. Brucella DNA was extracted from bovine milk by the optimized method.

In a previous study (10), a PCR assay was evaluated for the diagnosis of brucellosis in dairy cattle. Its sensitivity with respect to bacterial culture was lower than the sensitivity of the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, and some false-negative PCR results were reported. The inefficient bacterial DNA extraction could account for these PCR-negative results. In the present study, we evaluated the influence of different parameters (lysis buffer composition, temperatures and times of incubation, denaturing agents, combinations of enzymes and incubation conditions, etc.) on the optimum bacterial DNA extraction. Conditions that (i) improved disruption of bacterial cells, (ii) required fewer manipulations, and (iii) achieved the strongest and more reproducible amplification were selected. Based on the fact that Brucella has a very high affinity for the fat phase of the milk, Rijpens et al. (7) have described a PCR method based on enzymatic extraction of the milk components. They reported sensitivities of 2.8 × 104 Brucella CFU/ml of milk after a single PCR and reverse hybridization and 2.8 × 102 CFU/ml after a nested PCR. However, in our experience the use of nested PCR in bacteriological diagnosis increases the risk of DNA contamination and results in frequent false-positive results. Recently, Serpe et al. (12) described the detection of Brucella in milk by PCR after the release of bacterial DNA by a single-step procedure based on freezing and thawing steps. However, this simple sample-processing method did not enhance the efficiency of Brucella DNA since the PCR sensitivity reported was 4.2 × 104 CFU/ml. In our study, the limit of detection of Brucella after the improved bacterial DNA purification method was as low as 5 to 50 CFU/ml. A similar finding has been reported by Leal-Klevezas et al. (4). These authors purified Brucella DNA from the fatty top layer of milk with a lysis solution consisting of 1% SDS and 2% Triton X-100 followed by proteinase K digestion (125 mg/ml) and an organic extraction with phenol-chloroform. However, when we used this DNA purification method in preliminary assays, the PCR amplifications were always weak or even negative (data not shown).

The cell envelopes (CE) of most gram-negative bacteria are sensitive to Tris buffers and EDTA. However, Moriyón and Berman (5) have shown that Brucella CE was more resistant to nonionic detergents, EDTA, and Tris than were those of Escherichia coli. Likewise, ionic detergents, such as SDS, have a limited action on B. abortus CE under conditions used with CE of other gram-negative bacteria. These data show that the Brucella CE is held by forces stronger than those acting in the CE of other bacteria (6). Accordingly, we found that the use of NET lysis buffer with high concentrations of EDTA and Tris, high concentrations of SDS and proteinase K, and high temperatures of incubation was necessary for the efficient extraction of Brucella DNA. PCR sensitivity is hindered by the method used to isolate the nucleic acid target. In this regard, many substances have been described to be amplification inhibitors. We consistently obtained weaker amplifications when NaOH was used in the lysis buffer. DesJardin et al. (2) also reported that NaOH solutions can affect the sensitivity of the PCR. Recently, several commercial systems have been developed to avoid such inhibitors and to efficiently extract the bacterial DNA from biological samples. However, our results showed that replacement of the phenol-chloroform extraction step by the Instagene or Prep-A-Gene system does not improve the DNA amplifications. Similar findings with other commercial systems or Chelex resin have been reported for the amplification of microbial DNA (3). With the bacterial DNA purification method described in this paper, we increased the sensitivity of our previous PCR-based detection strategy. This sample preparation, followed by PCR, shows considerable promise for the detection of Brucella in milk samples. It is possible that this DNA purification method can also be applied to the PCR detection of other bacterial pathogens in milk.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to R. Díaz for his encouragement and support throughout the experimental work, to G. Martínez de Tejada for critically reviewing the manuscript, and to M. Pardo and J. L. Vizmanos for excellent technical work.

This work was supported by the Plan Nacional de Biotecnología (CICYT) of Spain (BIO96-1398-C02-01). Fellowship support for C. R. from the Asociación de Amigos de la Universidad de Navarra is gratefully acknowledged.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alton G G, Jones L M, Angus R D, Verger J M. Techniques for the brucellosis laboratory. Paris, France: Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 2.DesJardin L E, Perkins M D, Teixeira L, Cave M D, Eisenach K D. Alkaline decontamination of sputum specimens adversely affects stability of mycobacterium mRNA. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:2435–2439. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.10.2435-2439.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fredricks D N, Relman D A. Improved amplification of microbial DNA from blood cultures by removal of the PCR inhibitor sodium polyanetholesulfonate. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:2810–2816. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.10.2810-2816.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leal-Klevezas D S, Martínez-Vázquez I O, López-Merino A, Martínez-Soriano J P. Single-step PCR for detection of Brucella spp. from blood and milk of infected animals. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:3087–3090. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.12.3087-3090.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moriyón I, Berman D T. Effects of nonionic, ionic, and dipolar ionic detergents and EDTA on the Brucella cell envelope. J Bacteriol. 1982;152:822–828. doi: 10.1128/jb.152.2.822-828.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moriyón I, Gamazo C, Díaz R. Properties of the outer membrane of Brucella. Ann Inst Pasteur Microbiol. 1987;138:89–91. doi: 10.1016/0769-2609(87)90082-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rijpens N P, James G, Van Asbroeck M, Rossau R, Herman L M F. Direct detection of Brucella spp. in raw milk by PCR and reverse hybridization with 16S-23S rRNA spacer probes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:1683–1688. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.5.1683-1688.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rolfs A, Schuller I, Finckh U, Weber-Rolfs I. PCR: clinical diagnostic and research. Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag KG; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Romero C, Gamazo C, Pardo M, López-Goñi I. Specific detection of Brucella DNA by PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:615–617. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.3.615-617.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Romero C, Pardo M, Grilló M J, Díaz R, Blasco J M, López-Goñi I. Evaluation of PCR and indirect-ELISA on milk samples for the diagnosis of brucellosis in dairy cattle. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:3198–3200. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.12.3198-3200.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Serpe L, Gallo P, Fidanza N, Scaramuzzo A, Fenizia D. Rivelazione di Brucella spp. nel latte mediante PCR. Ind Aliment. 1998;37:191–192. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wilson K. Preparation of genomic DNA from bacteria. In: Ausubel F M, Brent R, Kimgston R E, Moore D D, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K, editors. Current protocols in molecular biology. New York, N.Y: Greene Publishing Associates, Inc., and John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1990. pp. 241–245. [Google Scholar]