Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the importance of social support for everyone. Supports from relatives, neighbors, and friends are more significant for a job seeker, especially during the pandemic. Accordingly, the present study explored the psychometric properties of the Perceived Social Support for Job Search Activities Scale (PSS-JSAS) in the Indian context with the help of two independent samples. First sample of 518 respondents was randomly divided into two subsamples using the random case selection feature in the statistical package for social sciences (SPSS). The exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was performed on the first subsample, which yielded a one-factor model explaining 47.23% of variations. The confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) conducted on the second subsample concluded a good model fit of PSS-JSAS. In the second sample, Cronbach's alpha and composite reliability values (greater than 0.70) established the scale's reliability. Results also revealed that the correlation coefficients between PSS-JSAS score, hope, self-efficacy, resilience, and optimism were 0.470, 0.552, 0.621, and 0.5 at p < 0.01. It also revealed a negative association with job search anxiety scores (r = −0.549, p < 0.01). Thus, PSS-JSAS was positively associated with PsyCap and negatively correlated with job search anxiety behaviors. It concluded the criterion validity of PSS-JSAS in the Indian context. Multigroup factor analysis concludes that the scale is equally valid for both Indian males and females. Hence, results reported adequate reliability and validity of the scale in the Indian context. These findings will encourage future researchers to investigate the phenomena of social support in the job search.

Keywords: PSS-JSAS, India, EFA, CFA

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has severely dampened the economic activities, including employment and vacancy posting [1]. State-imposed lockdowns, preventive closures by companies, and restricted labor movements have led to the reduction or complete loss of livelihoods for millions (OECD, 2021). In Sweden, vacancy postings were reduced by 40% during the first three months of the COVID outbreak [1]. In South Africa, around 2.2 to 2.8 million adults lost their jobs in the first quarter of 2020 [2]. Other countries like the USA, Canada, China, Brazil, etc., also showed similar downward trends in employment and economic activities. India is no exception: it witnessed an all-time high unemployment rate of 24% during and after the first national lockdown [3]. The situation was particularly challenging for India, with 52% of people self-employed in the informal sector and the other 25% engaged in casual daily wage work (National Sample Survey: 2017–18). Apart from financial hardship, such a situation led to a significant increase in people's anxiety, depression, stress, and suicidal behavior. A systematic review of nineteen studies during the pandemic reported rates for anxiety ranged from 15 to 42%, and depression ranged from 10 to 75% [4]. Amid such a depressing state of life, social support is considered an essential positive resource that can redeem the individual from adverse consequences of life [[5], [6], [7], [8]]. It improves the resilience of individuals, which enhances their capacity to cope with adverse events for a more extended period without negatively impacting their physical and mental well-being [9,10]; Vinokur &Van-Ryn, 1993).

Previously, studies have evidenced the relevance of social support in the early phase of an individual's life [6,8]. In this concern, it has been determined that youth are more vulnerable to mental and psychological problems due to inexperience in countering challenging situations (Paul & Moser, 2009; [11]. Youth are more likely to experience emotional turmoil while facing unexpected life events, which further trigger various psychological issues like depression, generalized anxiety disorder, eating disorders, self-harm, etc. [[12], [13], [14]]. In this background, interpersonal relationships and perceived social support are found to be highly efficient in coping with life stressors among youths [15,16]. Previous studies have recommended that social support has the potential to modify the behavior of youth, which subsequently influences their work domain and employment status [6,17,18,19]. The support of family members and friends play an important role in smooth transition from academic to work life. Social support during job search is poised to make life easier for a job aspirant [17]. However, not many previous searchers have provided the empirical evidences of linakge between social support and different job search-related activities. Accordingly, the present study has outlined the relevance of social support in influencing an individual's job search behavior, which further determines the possibility of receiving or obtaining the desirable job [20]. Specifically, it examines the role of social support in mitigating job search anxiety among job seekers in India. Since, the theme has not been investigated in the Indian context previously, the first and foremost step would be to explore the psychometric properties of social support scale among Indian job seekers.

Accordingly, the present study outlines three major objectives. First, it studies the level of perceived social support in job search activities among Indian job aspirants. Second, there is a scarcity of a reliable and valid scale to measure perceived social support in the Indian context. Thus, this study examines the psychometric properties of [21] perceived social support for job search activities scale (PSS-JSAS) among Indians. And, thirdly it investigates the relationship between perceived social support and job search anxiety among job aspirants.

In order to achieve these objectives, this study examines the psychometric properties of Perceived Social Support for Job Search Activities Scale (PSS-JSAS) in the Indian context with the help of two independent samples. The first sample was randomly divided into two subsamples using the random case selection feature in the statistical package for social sciences (SPSS). The exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was performed on the first subsample and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted on the second subsample. The derived model was subjected to reliability and validity investigation using second sample. This investigation helps in ensuring the reliability and validity of PSS-JSAS among Indian job seekers. Then, the scale is used to explore the level of social support during job search among job aspirants in India. And, lastly, the relationship between PSS-JSAS scores and job anxiety scores is evaluated using correlation.

2. Literature review

2.1. The role of social support in job search activities

The social convoy model states that groups and social relationships are protective components of life that contribute to growth in various domains of life [22,23]. The model highlights the importance of social relationships in ensuring people's affective, psychological, and emotional well-being [24,25]. For instance, Saxena et al. (2020) reported that a sense of community reduces stress among employees [26]. asserted that social affiliation restricts stress and promotes nonviolence among groups. Several studies have conveyed the relevance of social support as a catalyst that further built up other resources, such as self-efficacy, optimism, self-esteem, courage, hope, etc. [23,[27], [28], [29], [30]]. These resources are considered pivotal for personal and professional success, including in the job search process.

The job search is highly uncertain, frustrating, and time-consuming; thus, it may lead to feelings of helplessness, alienation, and loneliness [31]. Perceived social support in such situations helps one overcome physical and mental barriers during the job search process. The theory of planned job search outlines the importance of social support in ensuring a stress-free job search journey. Social support is described as a motivating phenomenon that enhances the job search endeavor of an unemployed individual. It provokes one to remain engaged in job search behavior for a longer time [13,32]. Job search behavior influences the enthusiasm of the job seekers to engage themselves in a job search activity [33,34]. Studies have opined that social support develops an optimistic or favorable attitude within the job seeker. A job seeker with active social support is more likely to achieve positive results in desirable jobs [20]. The theory of planned job search also outlines that low social support raises the societal pressure among job seekers, making them reluctant to invest efforts with vigor. Also, it weakens their coping mechanism against stressful events leading to mental and emotional turmoil [35,36]. Also, other studies illustrated that social support builds psychological and social resources in job seekers [27], which play an essential role in dealing with stress, anxiety, and trauma associated with job search and delay in obtaining a job [37,38].

In their meta-analyses, McKee-Ryan and his colleagues (2005) supported that unemployed youth with social support are more capacitated to respond better to job loss and further help them seek a new job. Similarly [39], have conducted a study to explore the relationship between job search behavior, social support, and self-efficacy among new entrant job seekers and unemployed or underemployed youth. The findings state that perceived social support improves job searchers’ self-esteem and self-efficacy, boosting their efforts to search for jobs more actively [40]. reported that social support from friends, family, and peers guides individuals in their career paths. It also improves the ability and self-efficacy to find the right job opportunities [41]. have attempted a study on 6,987 individuals living in Trent, England. The authors examined the quality of social support among job seekers. The study reported that unemployed youth had received poor social support from their known ones. Several other researchers like [40,[42], [43], [44]]; and [36] also reported various positive effects of social support on job seekers.

2.2. The relevance of social support in the Indian context

Social support in the job search has special significance for Indians for three possible reasons. First, unemployment in youth is a primary concern for India. It creates emotional, mental, and financial insecurities among youth [45,46]. Several studies have concluded that unemployment leads to anxiety, stress, depression, and psychological trauma. It takes away the purpose and identity from a person's life [35,47]. In his meta-analyses [18], suggested that unemployment leads to dissatisfaction with life, which raises psychological problems among unemployed youth. The issue of unemployment is severe in India. The thirty-day moving average unemployment rate was 11.84% in May 2021 [48]. The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has severely dented the prospects of respectable jobs for Indian youth [48,49]. Amid such a high unemployment rate, it would be fruitful to explore the role of social support in the job searching behavior of youth.

Second, India houses one of the largest pools of people in the working-age group. The average age of the Indian population is 28 years. However, the average age in China, Western Europe, the United States, and Japan is 37, 45, 37, and 49, respectively [50,51]. India has an excellent opportunity to become a knowledge economy by the end of 2022 by reaping the benefits of rich demographic dividends [52]. With these vast resources of youth ready to join the workforce, the validation of the PSS-JSAS scale in India will give impetus to studies on the social aspect of the job-seeking process. Third, Indian culture promotes interdependence and interconnectedness (Sharma et al., 2022). A sense of community is an indispensable characteristic of Indian culture [30]. India is well-known for its joint families, extended web of social relationships, and collectivism. Unlike western society, which emphasizes “individualism,” the Indian culture focuses on “collectivism” in that it promotes interdependence and cooperation [53]. Social support is thus an essential pillar for Indians.

Given the importance of social support and affiliation in Indian society, it would be interesting to examine the perceived social support in job search activities during the COVID-19 pandemic. Now, exploring social phenomena in great detail is pertinent to understanding its nitty-gritty. The first and foremost step for an in-depth examination is the availability of a reliable and valid scale to measure the variable. Unfortunately, to the best of our knowledge, neither any scale has been developed in the Indian context nor the psychometric properties of any existing scale have been examined among the Indian sample.

2.3. PSS-JSAS and the necessity to explore its validity among Indians

Researchers refer to a few scales like the multidimensional scale of perceived social support (MSPSS), PSS-JSAS, etc. are referred by researchers to capture social support during the job search. Researchers prefer PSS-JSAS for youth over MSPSS because MSPSS is more successful in measuring the role of social support in the working population, not in the job-seeking population [54,55]. The PSS-JSAS scale is theoretically premised on the social support theory, which states that social support strengthens an individual in normal times and protects one from stressors in challenging times [56,57]. It is an eight-item scale developed by Ref. [21]. Two of the eight items are reverse scored to control respondents' bias. The Cronbach's alpha of the scale was 0.84, and the face validity of the scale was established by a review by three employment and training specialists [21].

Although researchers worldwide have used the scale, there is a need to revalidate the same in different cultural settings. Social support is a cultural-specific phenomenon. The cultural values of a few countries cherish individualism while that of others appreciate collectivism and universalism. Thus, before using the scale, research is required to evaluate the psychometric properties of the PSS-JSAS scale in its cultural background [31].asserted that [21] did not elaborate on the factor structure of the scale. They only referred to face validity; thus, a robust statistical mechanism using exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis is required to establish the factor validity of the scale. Also [21], did not examine the gender invariance of the scale. Previous researchers, including, [19,58]; and [31]reported significant gender-based variations in perceived social support. These reasons necessitate the psychometric analysis of the scale in a novel (where the scale has not been validated) context like India. Accordingly, the present study explores the psychometric properties of PSS-JSAS in the Indian context in three stages. In the first step, the factorial structure of the scale was evaluated using exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). In the second step, the reliability and validity of the factorial model derived from EFA and CFA were evaluated. Lastly, gender invariance was examined using multigroup analysis in AMOS.

3. Method

3.1. Participants

Five hundred and eighteen final year students from different educational backgrounds participated in the present study. Final year postgraduate students were chosen for the study because they actively searched for a job. There were 52% male and 48% female participants. The students enrolled in science, commerce, humanities, and other courses were 29%, 43%, 19%, and 9%. The mean age of the sample was 23.6 years. The respondents registered in central, state, and private universities were 27%, 38%, and 35% of the sample. Convenience sampling was used, and respondents were invited to complete a questionnaire created on an online platform using Google Forms. The demographic details of sample are given in Table 1 .

Table-1.

Sample description.

| Variable | Category | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 52% |

| Female | 48% | |

| Courses | Science | 29% |

| Commerce | 43% | |

| Humanities | 19% | |

| Others | 9% | |

| University type | Central | 27% |

| State | 38% | |

| Private | 35% | |

| Age | Below 18 years | 1% |

| 19–20 years | 8% | |

| 21–22 years | 21% | |

| 23–24 years | 57% | |

| Above 24 years | 13% |

Source: Primary data

3.2. Instruments

The questionnaire is comprised of two parts. The first part of the questionnaire sought demographic details (age, gender, type of courses, and universities) of the respondents. The second part measured perceived social support for job search activities using [21] PSS-JSAS scale. It is an eight-item self-report measure that evaluates job seekers' level of social support throughout their job search on a five-point rating scale, with 1 indicating strong disagreement and 5 indicating strong agreement. A few scale items are “When I am turned down for a job interview, I receive positive encouragement for continuing my job search efforts,” and “I feel that others understand why I want to continue working.” The English version of the scale was used. Indian education system promotes the English language from the beginning of students’ academic life. And till the time student reach postgraduation level, they acquire a good grasp of the language.

Further, psychological capital (PsyCap) was assessed using a 12-item scale proposed by Ref. [59]. It has four dimensions: self-efficacy (3 statements), hope (4 statements), resilience (3 statements), and optimism (2 statements), rated on a six-point rating scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (6). A few scale items were “I feel confident contributing to discussions about the company's strategy,” “I can get through difficult times at work because I have experienced difficulty before,” and “I am optimistic about what will happen to me in the future as it pertains to work.”

And lastly, the job search anxiety scale developed by Ref. [60] was used to capture one's anxiety level during job search activities. The scale consisted of ten statements rated on a five-point rating scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5). Examples of the items are “I feel stressed about the idea of starting a job search” and “I am tense when I think about having to find a job.”

3.3. Procedure

The first page of the survey included information about the purpose and aim of the study. Informed consent was taken from the respondents by asking them to tick on the checklist. Then, respondents were promised confidentiality and anonymity of the data. They were also assured that data would not be shared with anyone and used for academic purposes only. It was clarified that participation in the survey was purely voluntary. And lastly, the participants were requested to read the statements carefully and provide their genuine opinion.

3.4. Data analysis

The sample of 518 respondents was randomly divided into two subsamples using the random case selection feature in SPSS. The EFA was performed on the first sample (n1 = 266). The cross-validation of the exploratory model of PSS-JSAS was evaluated by CFA using the second half of the data (n2 = 252). The indexes used to assess model fits were GFI (Goodness-of-Fit Index) and AGFI (Adjusted Goodness-of-Fit Index), CFI (Comparative Fit Index), and RMSEA (Relative Mean Square Error of Approximation) (Root-Mean-Square Error of Approximation). The model fit was determined using [61,62] criteria. The acceptable values were 0.90 for CFI, GFI, and AGFI and 0.08 for RMSEA. The CFI and RMSEA difference tests were used to verify measurement invariance.

4. Results

4.1. Exploratory factor analysis and confirmatory factor analysis

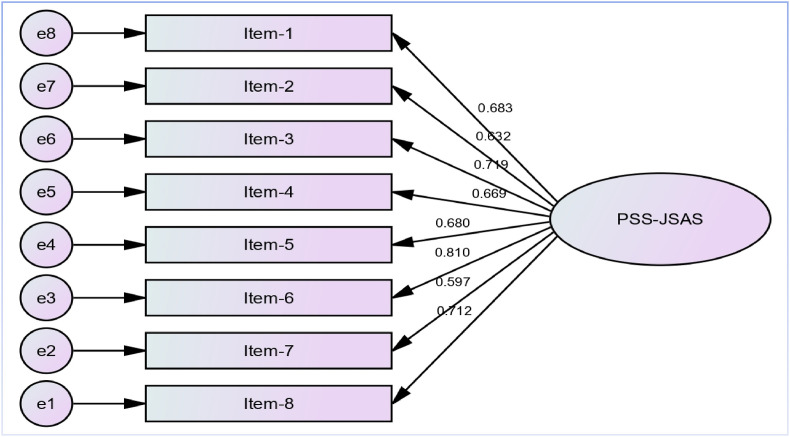

The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) sample adequacy value was 0.838, and Bartlett's test of sphericity was χ2 (28) = 356.286, p < 0.001. These results suggested that the data in subsample 1 were factorable and suitable for the EFA. The correlation matrix's determinant was 0.256, which was higher than the minimum recommended value of 0.0001. The value of 0.256 concluded the absence of multicollinearity or singularity. Now, the first subsample was subjected to EFA. Only one factor was extracted, which explained a total variance of 47.23% with an Eigenvalue of 4.267. The factor loading of eight items of PSS-JSAS ranged from 0.586 (Item 7: If I feel like quitting my search for a job, others encourage me to keep contacting employers) to 0.829 (Item 6: I feel that others understand why I want to continue working) (see Table 2 ). In a nutshell, EFA provided a one-factor solution with an acceptable factor loading of all items (greater than 0.40). The second subsample (n2 = 252) was used in a CFA to cross-validate the exploratory model. The single factor solution produced an excellent fit to the data in subsample 2 (n = 252), with χ2(20) = 23.576 (at p = 01), CFI = 0.989, GFI = 0.976, RMSEA = 0.027, and RMR = 0.031. Fig. 1 reports the pictorial results of the CFA model.

Table-2.

Factor loadings of PSS-JSAS from EFA in subsample 1 (n = 266).

| Item | Item description | Loading | h^2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | No one really understands how hard it is to find a job these days | 0.829 | .687 |

| 4 | Others encourage me to continue searching for a job even when I feel down. | 0.711 | .505 |

| 8 | When it comes to searching for a job, I have others supporting me. | 0.738 | .544 |

| 2 | When I am turned down for a job interview, I receive positive encouragement for continuing my job search efforts. | 0.775 | 600 |

| 1 | I feel that I am receiving a high level of support for my job search efforts. | 0.682 | .465 |

| 5 | I feel that others understand why I want to continue working. | 0.719 | .568 |

| 3 | I feel all alone in dealing with the frustrations of searching for a job | 0.745 | .555 |

| 7 | If I feel like quitting my search for a job, others encourage me to keep contacting employers. | 0.586 | .343 |

| Number of items | 8 | ||

| Eigenvalue | 4.267 | ||

| Total % of variance explained | 47.23 | ||

Source- Primary Data,* satisfactory factor loadings (i.e., greater than |.40| as per Field (2018)), (R) reversed scored items, h2 communality

Fig. 1.

Confirmatory factor analysis.

Source: Primary data

4.2. Reliability and validity

The reliability of the PSS-JSAS scale was measured using Cronbach's alpha and composite reliability estimates. These reliability estimates were calculated using SPSS 21. Although CFA concluded convergent and discriminant validity of PSS-JSAS, it was re-established using Average Variance Explained (AVE) values. Also, criterion validity was studied using the correlation coefficient of PSS-JSAS values with PsyCap and job search anxiety scores. The values of Cronbach's alpha and composite reliability of PSS-JSAS were 0.714 and 0.723, respectively. As these values are greater than the threshold value of 0.70, they conclude the reliability of PS-JSAS in the Indian context. The AVE value of PSS-JSAS was 0.525 (greater than 0.50), which reconfirmed the convergent validity of the scale among Indian students. According to the broaden-and-build theory, positive emotions build psychological resources. Thus, it is expected that social support-induced positive emotions may develop PsyCap for job seekers. It is anticipated that people getting social support during job search activities were more hopeful, confident, and optimistic about life. Thus, one expects a positive relationship between PSS-JSAS and the four dimensions of psychological capital (PsyCap). The correlation coefficients between PSS-JSAS score, hope, self-efficacy, resilience, and optimism were 0.470, 0.552, 0.621, and 0.5 at p < 0.01. Thus, PSS-JSAS was positively associated with PsyCap. It concluded the criterion validity of PSS-JSAS in the Indian context. Hence, the eight-item PSS-JSAS is recommended to be reliable and valid in the Indian context.

4.3. Measurement invariance

Multigroup analysis was also conducted to look at factorial invariance by gender. Table 3 reported that the levels of measurement invariance (configural, metric, scalar) for participants’ gender were acceptable. When the configural model was compared to the metric model, the change in magnitude of the CFI (ΔCFI), RMSEA (ΔRMSEA), and SRMR (ΔSRMR) was less than or equal to the cut-off criterion of −0.01, 0.02, and 0.03 for CFI, RMSEA, and SRMR, respectively. These results showed that the factor loadings in both groups (males and females) were equivalent, and the scale PSS-JSAS worked well for both males and females.

Table-3.

Fit statistics for the multi-group invariance testing across gender in subsample 2 (n = 252).

| Model | χ2 | df | CFI | SRMR | RMSEA | ΔCFI | ΔSRMR | ΔRMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0. Initial model | 23.576** | 20 | .989 | .0357 | .027 | – | – | – |

| 1. Configural invariance | 38.456** | 40 | 1.00 | .0507 | .000 | – | – | – |

| 2. Metric invariance | 48.858** | 48 | .997 | .0671 | .008 | -.003 | .0164 | .008 |

| 3. Scalar invariance | 61.98** | 56 | .981 | .0665 | .021 | -.016 | -.006 | .013 |

Source: Primary data, Male = 123, female = 129, CFI = comparative fit index, RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation, SRMR = standardised root mean square residual, CI = confidence interval, Δ = change in the statistic, **P < 0.01

4.4. Descriptive statistics and relationship with job search anxiety during COVID-19

Table 4 illustrates the descriptive statistics of the validated PSS-JSAS scale. It was reported that the overall PSS-JSAS score is 3.46, which is on the higher side considering a five-point rating scale ranging from 1 to 5. It indicates that Indian job aspirants got sufficient social support during the pandemic. In addition, the correlation coefficient between PSS-JSAS scores and job search anxiety scores was −0.549 (p < 0.01). As expected, the result states that social support would lead to lower levels of job search anxiety. Also, the regression coefficient was −0.549, which concluded that PSS-JSAS is negatively associated with job search anxiety.

Table-4.

Descriptive statistics of the (PSS-JSAS).

| S. No | Item description | M | SD | Skew | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | I feel that I am receiving a high level of support for my job search efforts. | 3.31 | 1.003 | 266 | -.990 |

| 2 | When I am turned down for a job interview, I receive positive encouragement for continuing my job search efforts. | 3.51 | 1.046 | 099 | −1.185 |

| 3 | I feel all alone in dealing with the frustrations of searching for a job (R) | 3.45 | 0.963 | .180 | -.923 |

| 4 | Others encourage me to continue searching for a job even when I feel down. | 3.44 | 0.986 | .277 | -.962 |

| 5 | I feel that others understand why I want to continue working. | 3.53 | 1.017 | .059 | −1.114 |

| 6 | No one really understands how hard it is to find a job these days (R). | 3.48 | 1.006 | 187 | −1.062 |

| 7 | If I feel like quitting my search for a job, others encourage me to keep contacting employers. | 3.59 | 0.855 | -.204 | -.561 |

| 8 | When it comes to searching for a job, I have others supporting me. | 3.40 | 1.012 | .191 | −1.049 |

| Total PSS-JSAS score | 3.46 | 0.974 | – | – |

Source: Primary Data, M = mean, SD = standard deviation. R = reverse coded item

5. Discussion

Social support is a vital component of Indian culture which integrates people into one unit by collaborating their emotional, social, and mental facets [63,64]. Indian society always cherishes social cohesion and collectivism, making them fend for each other in times of adversity [65]. Further, social circle and interpersonal bonds are fundamental features of Indians that nurture and preserve social values [66]. Considering the relevance of social support in India, the present study is intended to: a) examine the status of perceived social support, b) evaluate the psychometric properties of PSS-JSAS, and c) evaluate the relationship between PSS-JSAS and job search anxiety.

Accordingly, the sample was randomly divided into two subsamples. The first subsample utilized EFA with varimax rotation. EFA yielded a single factor structure for the 8-item PSS-JSAS with factor loading ranging from 0.586 to 0.829, explaining 47.23% variations. CFA was conducted on the second subsample, which also suggested a good model fit with acceptable model fit indices, χ2(20) = 23.576 (at p = 01), CFI = 0.989, GFI = 0.976, RMSEA = 0.027, and RMR = 0.031. These results are significant in three ways. First, while proposing the scale [21], did not evaluate the scale's factor structure. They relied on experts' views to determine the scale's validity. The present study derived the factorial structure of the scale using stringent statistical techniques like EFA and CFA. Second, while exploring the psychometric properties of PSS-JSAS in the context of Ghana [31], recommended a six-item factorial structure of the scale. The author suggested that two statements should be discarded to reduce acquiescent response bias. However, this study recommends all eight items inclusive factor structure in the Indian context. Third, the present study's CFA model (CFI = 0.989 and RMSEA = 0.027) seems to be a better fit than the CFA model proposed by Ref. [31] (CFI = 0.950 and RMSEA = 0.080), with better model fit indices. Thus, this study contributes to the literature by empirically and quantitatively examining the PSS-JSAS scale. Contrary to the previous study, it also proposes a better fit model encompassing all eight items of the scale.

Although Cronbach's alpha (0.714) was less than in previous studies (0.84 in Ref. [21]; and 0.79 in Ref. [31], the value is sufficient to recommend internal consistency reliability of the scale. This study supports Cronbach's alpha value with another reliability estimate, composite reliability, which has not been done in the previous studies. Most significantly, to the best of our knowledge, none of the earlier studies have examined the scale's criterion validity in any cultural context. The present study plugs the gap by exploring the relationship between the PSS-JSAS score and the four dimensions of PsyCap. As hypothesized, positive associations were reported, this establishes the criterion validity of the scale in the Indian context.

Also, previous studies, including [19,58]; have reported significant gender differences in perceived social support. India is considered a patriarchal society, where traditionally, men used to dominate every sphere of life. Therefore, it is required to investigate the measurement invariance of the PSS-JSAS to determine whether the scale could be utilized across genders (Pendergast et al., 2017). If measurement invariance is recommended, it shows that the construct has the same structure or meaning to both groups. Thus, it could be used to measure the phenomenon in both groups [21]. were criticized for not examining gender invariance of perceived social support. In line with [31] results, the present study concluded no gender-based invariances, suggesting that perceived social support is conceptualized similarly across males and females. Thus, in a nutshell, this study relied on a more robust and comprehensive methodology to establish the scale's reliability and validity.

Another significant contribution of the study is the exploration of the relationship between perceived social support and job search anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic. It is recommended that job aspirants with social backing report lesser job search anxiety. It implies that the social system must be boosted during job searching, as social interactions facilitate career counseling and provide helpful information for career options [67]. These findings are similar to those of [35,68]; and [6]. Individuals enriched in the social networks are less vulnerable to mental and emotional stress raised due to unemployment [68]. Similarly, social support provokes the individual to strive for continuous efforts to regain employment [20]. Moreover, social ties while searching for a job shares the burden of the miseries and reduce the ill consequences generated from searching for a job [6].

These findings offer practical and workable suggestions for various stakeholders. First, the results suggest that the PSS-JSAS is a psychometrically sound measure. Thus, it could be used in both basic and applied research in different fields like sociology, psychology, and human resource management to measure respondents' perceived social support. The scale could be used by career counselors and employment agencies to enquire about aspirants’ level of support. The counselor may suggest a career in such a field where aspirants have greater social support. Second, since social support reduces job search anxiety, it is recommended to use different group interventions to facilitate social support to a job seeker. Frequent interpersonal interactions with family members help job seekers to identify the right career path with the right efforts [69]. The universities and colleges may create social forums for the interaction of final year students, alumni, industry experts, and volunteers. It would facilitate a better flow of information, assistance, and counseling.

Although the present study provides empirical support for the reliability and validity of PSS-JSAS in the Indian context, the findings should be seen in the light of a few limitations. Firstly, the data is collected using convenience sampling, which is criticized for limiting the generalization of any empirical exploration. Future researchers may look at random sampling for greater acceptability of the study. Second, the study is based on a sample of final-year students. Although the sample is appropriate, a mix of the early, middle, and late-career aspirants could be more helpful for future researchers. Also, the present study only explores the internal consistency reliability of the scale. Future researchers may look at investigating the test-retest or inter-rater reliability. Future researchers may also examine the external and content validity of PSS-JSAS in the Indian context. The study's findings support socially connected and affiliated Indian society. Thus, it provides a frame of reference for future researchers to explore social support theory and the theory of planned job search in the Indian context. Also, future researchers may examine the role of various mediators like psychological capital, social rapport, and social exchange amid the relationship between perceived social support and job search anxiety.

In summary, working on the criticism of previous researchers like [21,31]; this study examined the psychometric properties of the PSS-JSAS using three novel tests (factor structure, criterion validity, and gender-based measurement invariance). Thus, it offers better structured and robust empirical evidence to establish the reliability and validity of the scale in the Indian context. The validation of the scale in the Indian context will encourage scholars to investigate the phenomena of social support in job search, especially in light of the global pandemic COVID-19.

Author statement

Naval Garg: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, validation, supervision; Poonam Mehta: Data curation, Writing- Original draft preparation. Mehak: Visualization, Investigation. Moaz Gharib Writing- Reviewing and Editing, Busayamas Pimpunchat: Reviewing, editing, and finalization of the article.

Biographies

Dr. Poonam Mehta is an Assistant Professor at Chandigarh University. She teaches Human Resource Management and Organizational Behavior. Her research interests are social support, emotional well-being, and job satisfaction

Dr. Naval Garg is an Assistant Professor (HRM & OB) at Delhi Technological. His research interests are workplace spirituality, gratitude, business ethics, and human-computer interaction. He has published more than fifty papers in various national and international journals.

Dr. Gharib is an Associate Professor in the department of management, college of commerce and business management, Dhofar University, Oman.

Ms. Mehak is a research scholar at IISC, Banglore. She is actively involved in different research activities.

References

- 1.Hensvik L., Le Barbanchon T., Rathelot R. Job search during the COVID-19 crisis. J Publ Econ. 2021;194 doi: 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104349. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Posel D., Oyenubi A., Kollamparambil U. Job loss and mental health during the COVID-19 lockdown: evidence from South Africa. PLoS One. 2021;16(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0249352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chatterji S., McDougal L., Johns N., Ghule M., Rao N., Raj A. COVID-19-Related financial hardship, job loss, and mental health symptoms: findings from a cross-sectional study in a rural agrarian community in India. Int J Environ Res Publ Health. 2021;18(16):8647. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18168647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hossain M.A., Rashid M.U.B., Khan M.A.S., Sayeed S., Kader M.A., Hawlader M.D.H. Healthcare workers' knowledge, attitude, and practice regarding personal protective equipment for the prevention of COVID-19. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2021;14:229–238. doi: 10.2147/jmdh.s293717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mol S.S.L., Arntz A., Metsemakers J.F.M., Dinant G.-J., Vilters-Van Montfort P.A.P., Knottnerus J.A. Symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder after non-traumatic events: evidence from an open population study. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;186(6):494–499. doi: 10.1192/bjp.186.6.494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kanfer R., Wanberg C.R., Kantrowitz T.M. Job search and employment: a personality motivational analysis and meta-analytic review. J Appl Psychol. 2001;86(5):837–855. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.86.5.837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bauman M. From foster care to fostering care: the need for community. Socio Q. 2000;41(1):85–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-8525.2000.tb02367.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lindorff M. Is it better to perceive than receive? Social support, stress and strain for managers. Psychol Health Med. 2000;5(3):271–286. doi: 10.1080/713690199. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mehta P. Fake it or make it: employee well-being in emotional work settings. Benchmark Int J. 2021;28(6):1909–1933. doi: 10.1108/BIJ-07-2020-0377. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen Y., Feeley T.H. Social support, social strain, loneliness, and well-being among older adults: an analysis of the Health and Retirement Study. J Soc Pers Relat. 2014;31(2):141–161. doi: 10.1177/0265407513488728. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chronister J.A., Johnson E.K., Berven N.L. Measuring social support in rehabilitation. Disabil Rehabil. 2006;28:75–84. doi: 10.1080/09638280500163695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hiswåls A.S., Ghilagaber G., Wijk K., Öberg P., Soares J., Macassa G. Employment status and suicidal ideation during economic recession. Health Sci J. 2015;9(1) doi: 10.22158/rhs.v2n1p12. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schwarzer R., Knoll N. Functional roles of social support within the stress and coping process: a theoretical and empirical overview. Int J Psychol. 2007;42(4):243–252. doi: 10.1080/00207590701396641. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vansteenkiste M., Lens W., De Witte H., Feather N.T. Understanding unemployed people's job search behaviour, unemployment experience and well-being: a comparison of expectancy-value theory and self-determination theory. Br J Soc Psychol. 2005;44(2):269–287. doi: 10.1348/014466604X17641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mousteri V., Daly M., Delaney L. The scarring effect of unemployment on psychological well-being across Europe. Soc Sci Res. 2018;72:146–169. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2018.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Symister P., Friend R. The influence of social support and problematic support on optimism and depression in chronic illness: a prospective study evaluating self-esteem as a mediator. Health Psychol. 2003;22(2):123–129. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.22.2.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feeney B.C., Collins N.L. A new look at social support: a theoretical perspective on thriving through relationships. Pers Soc Psychol Rev. 2015;19(2):113–147. doi: 10.1177/1088868314544222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McKee-Ryan F.M., Song Z., Wanberg C.R., Kinicki A.J. Psychological and physical well-being during unemployment: a meta-analytic study. J Appl Psychol. 2005;90(1):53–76. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.90.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matud M.P., Ibáñez I., Bethencourt J.M., Marrero R., Carballeira M. Structural gender differences in perceived social support. Pers Indiv Differ. 2003;35(8):1919–1929. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(03)00041-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Van Hooft E.A., Kammeyer-Mueller J.D., Wanberg C.R., Kanfer R., Basbug G. Job search and employment success: a quantitative review and future research agenda. J Appl Psychol. 2021;106(5):674–713. doi: 10.1037/apl0000675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rife J.C., Belcher J.R. Social support and job search intensity among older unemployed workers: implications for employment counselors. J Employ Counsel. 1993;30(3):98–107. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Birditt K.S., Antonucci T.C., Tighe L. Enacted support during stressful life events in middle and older adulthood: an examination of the interpersonal context. Psychol Aging. 2012;27(3):728–741. doi: 10.1037/a0026967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garg N. Exploring role of gratitude in developing teacher leadership in Indian universities. Int J Educ Manag. 2020;34(5):881–901. doi: 10.1108/IJEM-07-2019-0253. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fiori K.L., Antonucci T.C., Akiyama H. Profiles of social relations among older adults: a cross-cultural approach. Ageing Soc. 2008;28(2):203–231. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X07006472. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garg N., Gera S. Gratitude and leadership in higher education institutions: exploring the mediating role of social intelligence among teachers. J Appl Res High Educ. 2019;12(5):915–926. doi: 10.1108/JARHE-09-2019-0241. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sarkar A., Garg N. “Peaceful workplace” only a myth? Examining the mediating role of psychological capital on spirituality and nonviolence behaviour at the workplace. Int J Conflict Manag. 2020;31(5):709–728. doi: 10.1108/ijcma-11-2019-0217. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen I.S., Fellenz M.R. Personal resources and personal demands for work engagement: evidence from employees in the service industry. Int J Hospit Manag. 2020;90 doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Contreras F., Espinosa J.C., Esguerra G.A. Could personal resources influence work engagement and burnout? A study in a group of nursing staff. Sage Open. 2020;10(1) doi: 10.1177/2158244019900563. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hirsch J.K., Conner K.R., Duberstein P.R. Optimism and suicide ideation among young adult college students. Arch Suicide Res. 2007;11(2):177–185. doi: 10.1080/13811110701249988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garg N., Sarkar A. Vitality among university students: exploring the role of gratitude and resilience. J Org Effect: People Perform. 2020;7(3):321–337. doi: 10.1108/JOEPP-03-2020-0041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Teye-Kwadjo E. The perceived social support for job search activity scale (PSS-JSAS): a psychometric evaluation in the context of Ghana. Curr Psychol. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s12144-021-02164-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schwarzer K.I., Moser K. Unemployment impairs mental health: meta-analyses. J Vocat Behav. 2009;74(3):264–282. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2009.01.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maier S.F., Seligman M.E.P. Learned helplessness at fifty: insights from neuroscience. Psychol Rev. 2016;123(4) doi: 10.1037/rev0000033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vansteenkiste S., Verbruggen M., Sels L. Flexible job search behavior among unemployed job seekers: antecedents and outcomes. Eur J Work Organ Psychol. 2016;25(6):862–882. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Van Hooft E.A.J., Noordzij G. The effects of goal orientation on job search and reemployment: a field experiment among unemployed job seekers. J Appl Psychol. 2009;94:1581–1590. doi: 10.1037/a0017592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lakey B., Cohen S. In: Social support measurement and intervention: a guide for health and social scientists. Cohen S., Underwood L.G., Gottlieb B.H., editors. Oxford University Press; 2000. Social support theory and measurement; pp. 29–52. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Salanova M., Bakker A.B., Llorens S. Flow at work: evidence for an upward spiral of personal and organizational resources. J Happiness Stud. 2006;7(1):1–22. doi: 10.1007/s10902-005-8854-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cohen S. Social relationships and health. Am Psychol. 2004;59(8):676–684. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.8.676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Holmstrom A.J., Russell J.C., Clare D.D. Assessing the role of job-search self-efficacy in the relationship between esteem support and job-search behavior among two populations of job seekers. Commun Stud. 2015;66(3):277–300. doi: 10.1080/10510974.2014.991043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Al-Jubari I., Shamsol Anuar S.N.B., Ahmad Suhaiml A.A.B., Mosbah A. The impact of career adaptability and social support on job search self-efficacy: a case study in Malaysia. J Asian Finance Econ Bus. 2021;8(6):515–524. doi: 10.13106/jafeb.2021.vol8.no6.0515. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Roberts H., Pearson J.C., Madeley R.J., Hanford S., Mogawan R. Unemployment and Health:the quality of social support among residents in the Trent region of England. J Epidemiol Community. 1997;51(1):41–45. doi: 10.1136/jech.51.1.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hulshof I.L., Demerouti E., Le Blanc P.M. A job search demands-resources intervention among the unemployed: effects on well-being, job search behavior and reemployment chances. J Occup Health Psychol. 2020;25(1):17–31. doi: 10.1037/ocp0000167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Oh H.J., Ozkaya E., LaRose R. How does online social networking enhance life satisfaction? The relationships among online supportive interaction, affect, perceived social support, sense of community, and life satisfaction. Comput Hum Behav. 2014;30:69–78. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2013.07.053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Waters L.E., Moore K.A. Coping with economic deprivation during unemployment. J Econ Psychol. 2000;22(4):461–482. doi: 10.1016/S0167-4870(01)00046-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fergusson R. In: International organizations in global social governance. Global dynamics of social policy. Martens K., Niemann D., Kaasch A., editors. Palgrave Macmillan; Cham: 2021. International organizations' involvement in youth unemployment as a global policy field, and the global financial crisis. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jumpah E.T., Ampadu-Ameyaw R., Owusu-Arthur J. Youth employment in Ghana: economic and social development policies perspective. World J Enterpreneur Manag Sustain Dev. 2020;16(4):413–427. doi: 10.1108/wjemsd-07-2019-0060. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bolger N., Amarel D. Effects of social support visibility on adjustment to stress: experimental evidence. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2007;92:458–475. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.92.3.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy, CMIE (2021). Retrieved from https://www.cmie.com/kommon/bin/sr.php?kall=warticle&dt=2021-05-24%2011:01:18&msec=696, accessed on 08/08/2021.

- 49.Shaik R.A., Nazeer M., Ahmed M.M. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on Indian migrant workers. J Evol Med Dent Sci. 2021;10(6):362–369. htpps://10.14260/jemds/2021/81 [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jain N., Goli S. 2021. Potential demographic dividend for India, 2001 to 2061: a macro-simulation projection using the spectrum model. SSRN 3916176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Singh P., Kumar S. Demographic dividend in the age of neoliberal capitalism: an analysis of employment and employability in India. Indian J Lab Econ. 2021;64:1–25. doi: 10.1007/s41027-021-00326-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bisht N., Pattanaik F. How inclusive is “inclusive development” in India? Challenges and prospects of Indian youth labour market. Int Bus Educ J. 2021;14(1):17–33. doi: 10.37134/ibej.vol14.1.2.2021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chadda R.K., Deb K.S. Indian family systems, collectivistic society and psychotherapy. Indian J Psychiatr. 2013;55(2):S299. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.105555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dambi J.M., Corten L., Chiwaridzo M., Jack H., Mlambo T., Jelsma J. A systematic review of the psychometric properties of the cross-cultural translations and adaptations of the Multidimensional Perceived Social Support Scale (MSPSS) Health Qual Life Outcome. 2018;16(1):1–19. doi: 10.1186/s12955-018-0912-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zimet G.D., Dahlem N.W., Zimet S.G., Farley G.K. The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J Pers Assess. 1988;52(1):30–41. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa5201_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sarason I.G., Sarason B.R. Social support: mapping the construct. J Soc Pers Relat. 2009;26(1):113–120. doi: 10.1177/0265407509105526. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Uchino B.N. Social support and health: a review of physiological processes potentially underlying links to disease outcomes. J Behav Med. 2006;29(4):377–387. doi: 10.1007/s10865-006-9056-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhou M. Gender differences in the provision of job-search help. Gend Soc. 2019;33(5):746–771. doi: 10.1177/0891243219854436. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Luthans F., Avolio B.J., Avey J.B., Norman S.M. Positive psychological capital: measurement and relationship with performance and satisfaction. Person Psychol. 2007;60(3):541–572. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6570.2007.00083.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Britton T. University of the Witwatersrand; Johannesburg: 2019. Job search anxiety, transition resources, and wellbeing.https://wiredspace.wits.ac.za/bitstream/handle/10539/29418/Final [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hair J.F. seventh ed. Prentice Hall; Upper Saddle River: 2009. Multivariate data analysis: a global perspective. 2009. Print. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tabachnick B.G., Fidell L.S. International edition; 2013. Using multivariate statistics. Pearson2012. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Power E.A. Social support networks and religiosity in rural South India. Nat Human Behav. 2017;1(3):1–6. doi: 10.1038/s41562-017-0057. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sawanth N.S., Jethwani K.S. Understanding family functioning and social support in unremitting schizophrenia: a study in India. Indian J Psychiatr. 2010;52(2):145–154. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.64593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Das S., Das B., Nath K., Dutta A., Bora P., Hazarika M. Impact of stress, coping, social support, and resilience of families having children with autism: a North East India-based study. Asian J Psychiatr. 2017;28:133–139. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2017.03.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sinha S.P., Nayyar P.S., Sinha S.P. Social support and self-control as variables in attitude toward life and perceived control among older people in India. J Soc Psychol. 2002;142(4):527–540. doi: 10.1080/00224540209603916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Oludayo A.O., Omonijo D.O. Work-life balance: relevance of social support. Acad Strat Manag J. 2020;9(3):1–10. 1939-6104-19-3-557. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Heydari M., Xiaohu Z., Saeidi M., Lai K.K., Shang Y., Yuxi Z. Analysis of the role of social support-cognitive psychology and emotional process approach. Eur J Transl Myol. 2020;30(3):1–13. doi: 10.4081/ejtm.2020.8975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Saltzman L.Y., Hansel T.C., Bordnick P.S. Loneliness, isolation, and social support factors in post-COVID-19 mental health. Psychol Trauma: Theor Res Pract Pol. 2020;12(S1):S55–S57. doi: 10.1037/tra0000703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]