Abstract

In Tau protein condensates formed by the Liquid-Liquid Phase Separation (LLPS) process, liquid-to-solid transitions lead to the formation of fibrils implicated in Alzheimer’s disease. Here, by tracking two contacting Tau-rich droplets using a simple and nonintrusive video microscopy, we found that the halftime of the liquid-to-solid transition in the Tau condensate is affected by the Hofmeister series according to the solvation energy of anions. After dissecting functional groups of physiologically relevant small molecules using a multivariate approach, we found that charged groups facilitate the liquid-to-solid transition in a manner similar to the Hofmeister effect whereas hydrophobic alkyl chains and aromatic rings inhibit the transition. Our results not only elucidate the driving force of the liquid-to-solid transition in Tau condensates, but also provide guidelines to design small molecules to modulate this important transition for many biological functions for the first time.

Keywords: liquid-liquid phase separation, liquid-to-solid transition, Tau condensates, Hofmeister effect, small-molecule modulation

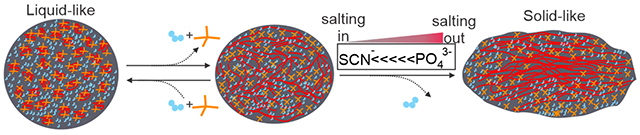

Graphical Abstract

Small molecules with hydrophobic groups (yellow tetrahedral sticks) interact with Tau proteins (red), stabilizing LLPS condensates stay in the liquid-like phase. Tau proteins start to interact with neighboring Tau proteins and aggregate into the solid-like state in the droplet. Salting out ions following the Hofmeister series facilitate the liquid-to-solid transition.

Liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS) is a phase transition phenomenon underlining many chemical, physical, and biological processes.[1] Inside cells, LLPS is critical for the formation of membraneless compartments. Unlike the oil-water phase separation in which the two phases are immiscible due to their respective preference of neighboring molecules with similar properties, LLPS can form between two aqueous phases, each of which is enriched with a distinct set of water-soluble components. Inside cells, LLPS droplets with specific biomolecular components such as RNA and proteins become phase separated from the rest of the cytosol.[2] The interactions between constituting biomolecular components in LLPS droplets employ intermolecular forces (IMF)[3] such as ionic force and hydrophobic interactions. These IMF interactions are affected by soluble components, which can freely enter or leave LLPS condensates due to their membraneless nature. This feature has made the size and the property of LLPS condensates highly dynamic during cell cycles or under distinct external stimuli.

Even for condensates with the same components, their properties vary with time during or after the LLPS process. Over time, it has been found that liquid-to-solid transition occurs in LLPS condensates.[4] This phenomenon has been proposed to cause fibril formation in many neurological diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease.[5] Therefore, it is conceivable to design strategies to disrupt this liquid-to-solid transition in LLPS droplets as a potential treatment for various diseases. Current investigations on LLPS droplets mainly use turbidity or fluorescence measurement. While turbidity is simple and fast, it can’t differentiate morphology or property of individual LLPS droplets, which may be determined by light-scattering techniques.[6] However, both light-scattering and turbidity have low sensitivities while they can’t analyze LLPS droplets one-by-one. By mixing LLPS droplets with fluorophores, individual droplets can be imaged under fluorescence microscope to reveal their size and property. In particular, phase transitions can be probed by the thioflavin dye[2, 7], which showed distinct fluorescence signal for aggregated proteins in LLPS condensates. The biggest drawback of fluorescence measurement is its intrusive nature, which requires the use of fluorophores that may interfere with the property of LLPS condensates. In addition, fluorescence background is omnipresent especially inside cells, compromising the robustness of this method.

In this work, we used simple and non-invasive optical microscopy to investigate the liquid-to-solid transition in LLPS condensates. We reasoned that in a liquid state, fusion of two LLPS droplets occurs spontaneously. However, it is expected to take longer fusion time when two droplets become solid like. To measure the fusion time, we used two optical tweezers[8] to grab and bring two Tau droplets together. Previously, optical tweezers[9] have been used to investigate the fusion of condensate droplets such as lipid droplets[10] and phase separated binary protein droplets.[9a] However, in all these fusion studies, laser traps were continuously used, causing potential bias in the determination of the fusion time since the strong laser power and the gradient force at the focus of a trapping laser may vary the properties of a trapped liquid droplet. In our approach, optical tweezers were transiently used to trap and move two neighboring droplets until they touched each other. The degree of the fusion, which reflects the extent of the liquid-to-solid transition, was evaluated by observing the shape of two touching droplets. After establishing this innovative fusion assay, we then evaluated the effect of ions on the liquid-to-solid transition of the Tau LLPS condensates. Previously LLPS process has been found to be influenced by anions according to the Hofmeister series.[11] However, the effect of different ions in solution on the liquid-to-solid phase transition has never been systematically studied. Finally, we dissected the functional groups of biologically important small molecules, such as ATP and amino acids, to understand their effects on the liquid-to-solid transition of the Tau condensates. Our method can be used to screen and identify small molecules that may interfere with the liquid-to-solid transition of Tau or other protein condensates, which lead to amyloid fibrils found in Alzheimer[5a] and many other diseases.[12] Our results are also instrumental to understand the mechanism of the liquid-to-solid transition in the omnipresent LLPS processes inside cells.

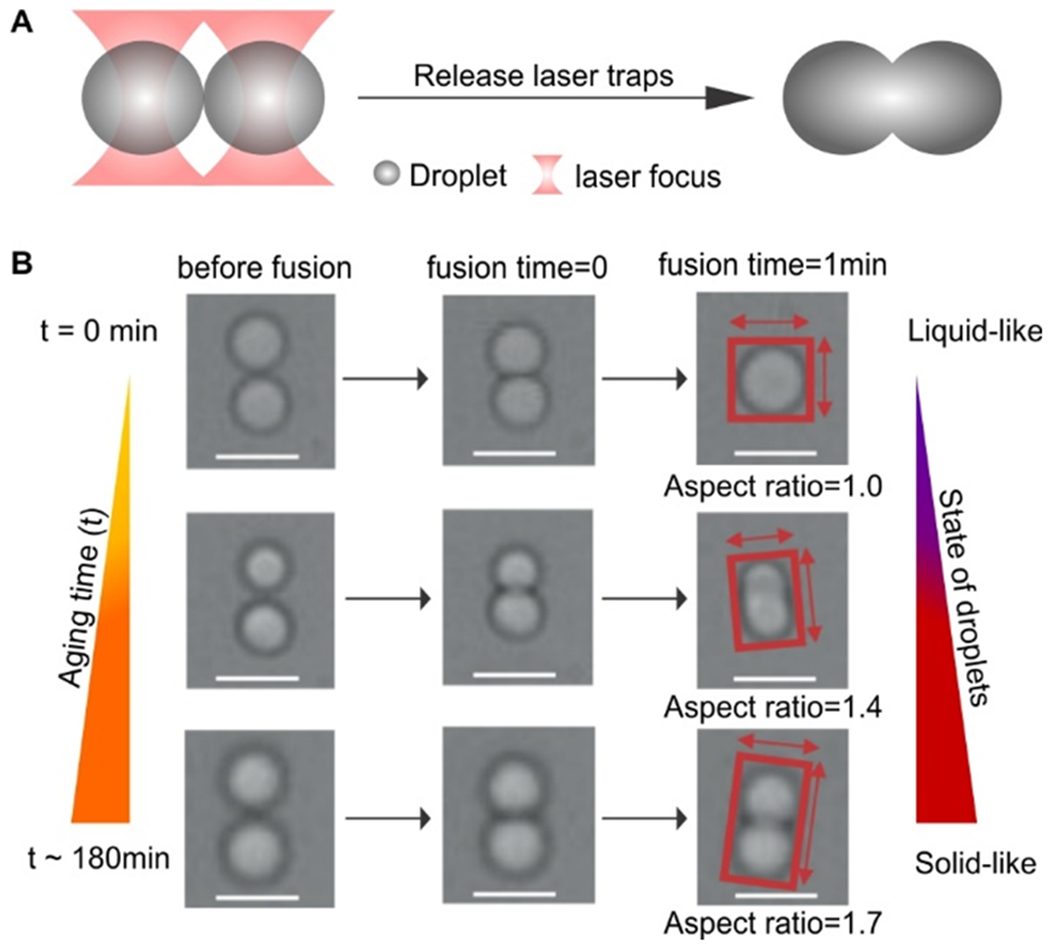

When a LLPS condensate reaches solid-like or gel-like state after liquid-to-solid transition, the molecular motion inside the condensate becomes restricted, which is expected to adversely affect the fusion between two LLPS condensate droplets. Based on this principle, we will monitor the extent of the liquid-to-solid transition in LLPS condensates. To this end, we first prepared Tau LLPS droplets by mixing 5 μM Tau protein with 15% PEG 6000 in 25 mM HEPES buffer at pH 7.4 according to reported methods.[13] To test the fusion of two LLPS droplets, we used our laser tweezers[8] to trap two Tau condensates and then let them touch with each other. The fusion time was started once the two droplets touched with each other while the lasers were off. The aging time was started as soon as the PEG was added to the system. Upon touching, we released both laser traps to avoid the influence of the trapping laser on the fusion (Figure 1a). The fusion event was recorded by a CCD camera (see SI for details). The shape of two touched condensate droplets during the aging time window of 30 sec - 5 hr was evaluated by their aspect ratio (Figures 1b and S2), the value of which represents the extent of the fusion between the two condensates. If the aspect ratio is 1.0 (perfect spherical), the fusion between the condensates is complete, which implies that the condensates are liquid-like (Figure 1b). In contrast, high aspect ratios (e.g. >1.7) suggest little fusion between two condensates, implying the droplets are solid-like.

Figure 1.

Fusion of two Tau condensates assisted by optical tweezers. (a) Schematic of the fusion of two Tau condensates (5 μM Tau and 15% PEG 6000 in 25 mM HEPES buffer at pH 7.4) trapped by two laser beams. (b) 1-min fusions of two Tau condensates at 3 aging times. Aspect ratios of fused condensates depict stages of the liquid-to-solid transitions. Scale bar, 3 μm.

Given that thioflavin has shown its capability to probe amyloid fibrils,[7] we mixed 10 μM thioflavin with 5 μM Tau and 15% PEG 6000 in the same HEPES buffer (pH 7.4). Within 48 hrs, we did not observe any change in fluorescence intensity of the condensates. This result suggested that the liquid-to-solid transitions we observed for the Tau condensates by video microscopy did not involve the amyloid fibril formation of Tau proteins. Indeed, it has been found that it took 3 days for thioflavin to recognize the Tau fibrils.[14] This observation also supported the finding that fibril formation for the Tau protein occurred after the liquid-to-solid transition in the LLPS Tau condensates.[4a]

With the established method for monitoring liquid-to-solid transitions, we tested it on the Tau condensates in the presence of different ions. Over the past decades, influences of ions on many bio-transitions have been shown to follow the Hofmeister series.[15] It was considered that these influences were originated from the ability of ions to make or break water structures.[t] Since the hydration shell is expected to be expelled during the fibril formation in the Tau condensates, we anticipated that the effects of ions on the liquid-to-solid transition of Tau condensates should follow the trend of the Hofmeister series.

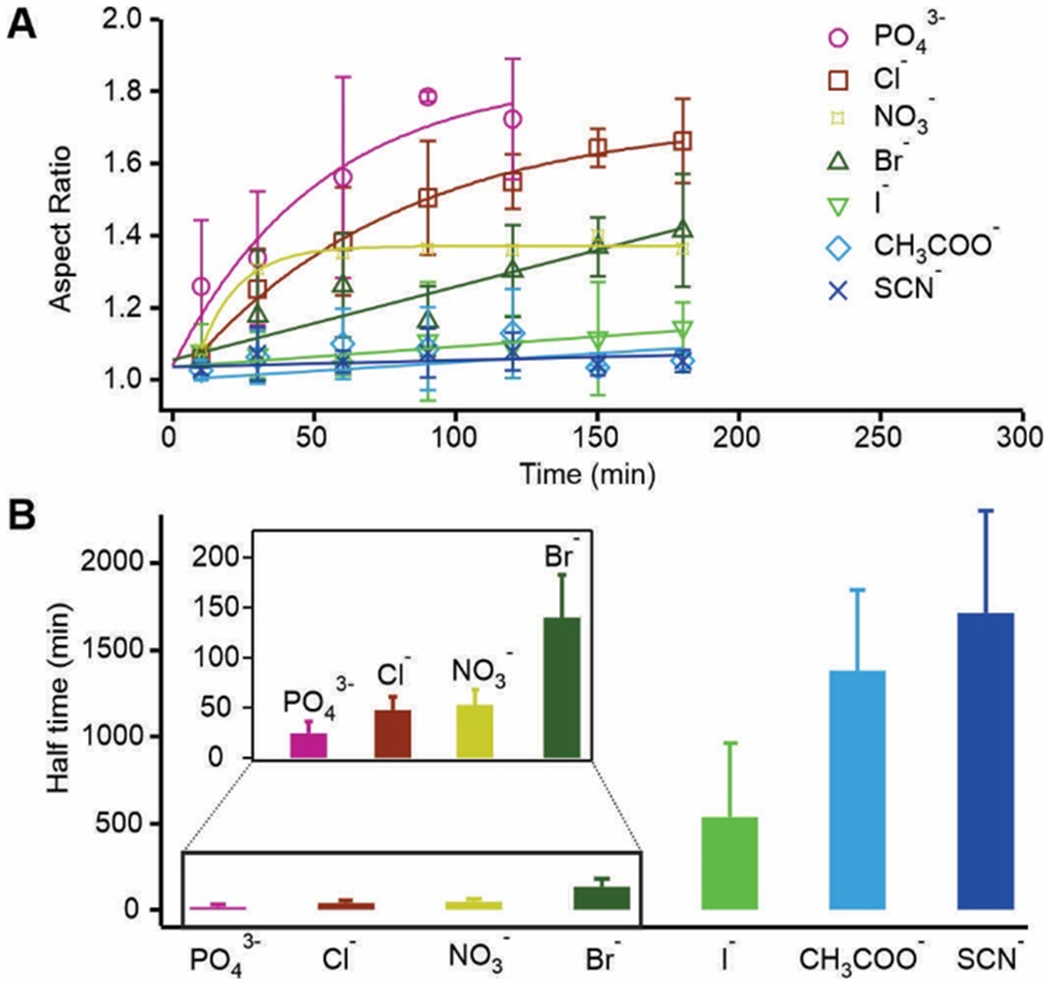

Since the effects of Hofmeister ions are usually more pronounced for anions than cations[16], we chose a series of anions to test our hypothesis. We fixed the potassium cation (150 mM) and changed anions (150 mM) to measure the liquid-to-solid transition of 5 μM Tau condensates in the 25 mM HEPES buffer (1 mM DTT, 15% PEG 6000 pH 7.4) within 5 hours upon the touching of two Tau condensate droplets (Figure S3). At every aging timepoint, we chose at least 3 pairs of condensates to measure the aspect ratio of two joined droplets. The diameter of each condensate droplet was chosen between 1 to 3 μm to avoid the size effect on the transition kinetics[9a]. The average of aspect ratios at different aging time for different anions is shown in Figure 2a. Other than the iodide, acetate, and thiocyanate, an obvious increase of aspect ratio was observed for the rest of the anions over time, which suggested that liquid-to-solid transition occurred faster for these anions.

Figure 2.

Kinetics of the liquid-to-solid transition in Tau condensates. (a) Aspect ratio of the two joined Tau LLPS droplets vs aging time in the presence of different Hofmeister ions (150 mM) in the 25 mM HEPE buffer at pH 7.4. (b) Halftime (t1/2) of the liquid-to-solid transition for different anions. Note 150 mM KCl serves as the control ion for the following experiments in this work. Error bars represent standard deviations from 3 independent measurements.

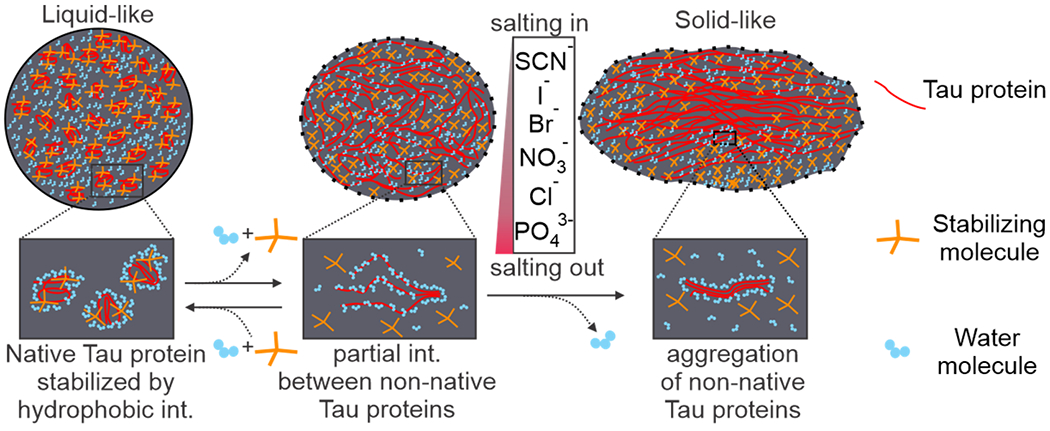

To quantify the liquid-to-solid transition, we used a single exponential or a linear equation to fit the change in the aspect ratio over aging time (see SI methods for details). Between the two equations, the one with the better fitting to the data was chosen to quantify the rate of the transition. The resultant fitting parameters (see Table S1) were used to calculate the halftime (t1/2) with respect to chloride, which is defined as the aging time for the aspect ratio to reaching the half value (A/R = 1.34) between perfect fusion (A/R = 1.0) and no fusion (A/R ~ 1.68, it is noteworthy that due to the soft nature of the Tau condensates, A/R = 2 expected for the two non-fused spherical droplets was never observed). As shown in Figure 2b, the capability of anions to increase the halftime (t1/2) for the liquid-to-solid transition follows the general trend of the Hofmeister series, except the acetate ion (normal Hofmeister series: PO43− < acetate− < Cl− < NO3− < Br− < I− < SCN−;[17] our observation for the Tau condensates: PO43− < Cl− < NO3− < Br− < I− < acetate− < SCN−). Recent investigations revealed that Hofmeister series reflects the trend in the solvation energy between specific ions and water molecules.[18] This general trend suggests that removal of water molecules by anions (salting out) seems to be important factor for the liquid-to-solid transitions in LLPS (Figure 3). Such an observation is consistent with the finding that in the solid-like Tau condensates, the Tau molecules become entangled with each other[19] and the process is likely accompanied by loss of the water molecules solvating individual Tau molecules in the liquid-like state. It is surprising that the acetate ion deviates from the Hofmeister series by maintaining a more liquid-like Tau condensate. Close inspection on the acetate structure led us to propose that this anomaly maybe due to its hydrophobic hydrocarbon moiety. We surmised this hydrophobic moiety might stabilize isolated Tau proteins, slowing the transition to the solid-like phase via aggregation of neighboring Tau proteins (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Schematic of proposed liquid-to-solid transition of LLPS Tau condensates in presence of small molecules. Small molecules with hydrophobic groups interact with Tau proteins, helping LLPS condensates stay in the liquid-like phase (left). Tau proteins start to interact with neighboring Tau proteins (middle) and aggregate into the solid-like state (right) in the droplet. Salting out ions following the Hofmeister series facilitate the liquid-to-solid transition. Solid and dotted outlines of the condensates reflect the spherical and uncertain shapes, respectively.

Acetate is a natural molecule inside cells. This fact plus its abnormal effect on the liquid-to-solid transition of the Tau condensates (Figure 2) prompted us to evaluate the effect of different functional groups of naturally occurring small molecule adducts on the LLPS process. It is well known that the protein LLPS process is driven by a wide variety of interactions, including charge-charge, cation-π, dipole-dipole, and π-π stacking interactions among protein molecules or between proteins and surrounding molecules.[20] Inside cells, the protein LLPS condensates are surrounded by physiologically relevant small molecules with different functional groups that can interfere with the liquid-to-solid transition by directly interacting with proteins for example (Figure 3).

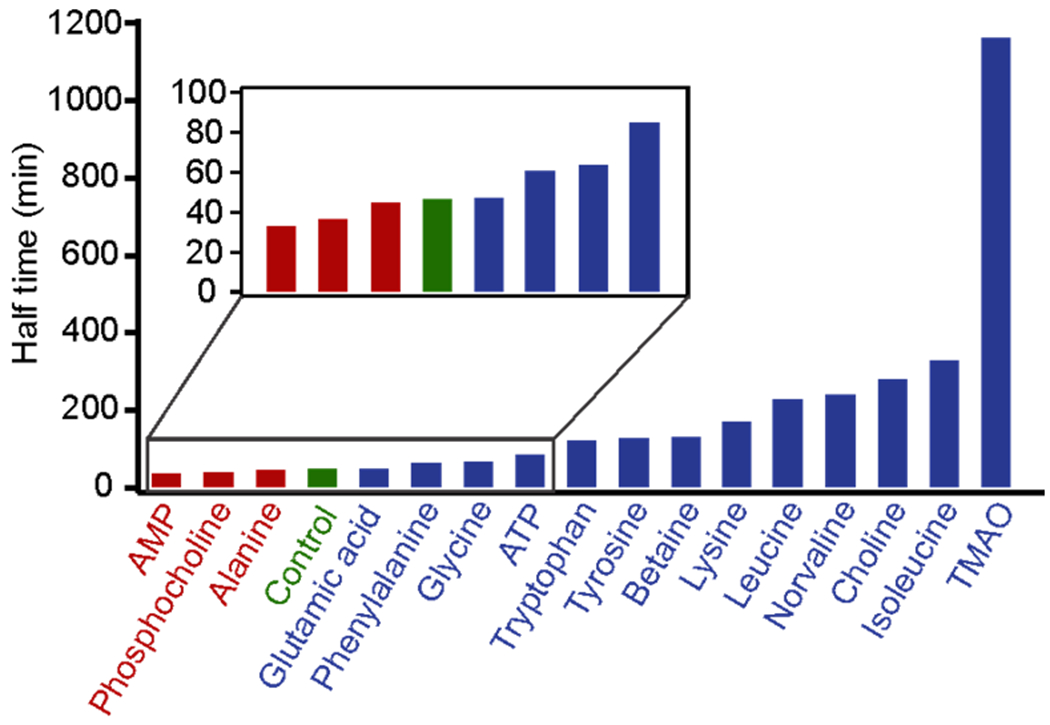

Using the microscopy imaging method established above, we followed the aspect ratios of Tau condensates in presence of sixteen molecules including amino acids, AMP, ATP, and choline and its derivatives (Figures S1 and S4). The trends of the aspect ratios were quantified as described above to obtain the halftimes (t1/2) for the liquid-to-solid transitions of the Tau condensates (Figures 4 and S5). Inspection on the halftimes vs corresponding molecular structures (Table S2) allowed us to identify common structural characteristics that lead to longer halftime of the liquid-to-solid transitions in the Tau condensates with respect to that without ligand (control). For instance, TMAO and choline, which contain a trimethylamino group, showed rather long halftimes. It has been reported that TMAO can stabilize elastin structure by directly interacting with the protein,[21] which supported our finding that TMAO resulted in a rather long halftime for the liquid-like Tau condensates to reach the solid-like state.

Figure 4.

Halftime of the liquid-to-solid transition in Tau condensates in presence of physiologically important small molecules. Each small molecule (0.2 mM) was dissolved in 25 mM HEPES buffer at pH 7.4 at room temperature. Inset indicates the blowup of the molecules with shorter halftimes. Blue and red colors show the halftimes longer and shorter than that of the control (green, without small molecules), respectively.

Next, we quantified the contributions from different functional groups in a small molecule to the halftimes (t1/2) of the liquid-to-solid transition in the Tau condensates. In the first step, the molecules were dissected into sub-molecular functional groups, which include alkyl, phosphate, amino, acetate, aromatic, and trimethylamino groups. For each molecule, we quantified the number of constituting functional groups (Table 1). In particular, the alkyl group was quantified by the carbon number whereas the aromatic group was evaluated by the number of conjugated atoms. Next, we used the numbers of molecular functional groups as matrix A, the halftime difference (Δt1/2) between a molecule and the control (without small molecules) as column vector b, and the contribution of each functional group to the change in halftime (Δt1/2) as column vector x. To evaluate the contribution of each group to the halftime, we solved the x of the linear system, Ax = b (see SI methods for details). The results are summarized in Table 2.

Table 1.

Number of functional groups (or atoms) in small molecules. Halftime of the liquid-to-solid transition in the Tau condensates without small molecules is subtracted from that with small molecules and plotted in the last column (Δt1/2).

| # of phosphate | # of carboxyl | # of trimethylamino | # of amino | Carbon # of free alkyl chain | # of atoms conjugated in aromatic ring | Change in half time (Δt1/2/min) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMP | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 | −13 |

| Phosphocholine | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | −10 |

| Alanine | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | −1 |

| Glutamic acid | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| Phenylalanine | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 15 |

| Glycine | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 17 |

| Tryptophan | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 9 | 72 |

| Tyrosine | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 80 |

| Betaine | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 84 |

| Lysine | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 122 |

| Leucine | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 181 |

| Norvaline | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 191 |

| Choline | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 232 |

| Isoleucine | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 280 |

Table 2.

Contribution of each type of functional group to the change in halftime (Δt1/2) of the liquid-to-solid transition of the Tau condensate.

| Functional group | Contribution to the change in half time (Δt1/2/min) |

|---|---|

| Phosphate | −134 |

| Carboxyl | −43 |

| Amino | −30 |

| Conjugated atoms on aromatic ring | 10 |

| Trimethylamino | 58 |

| Carbon on free alkyl chain | 71 |

From Table 2, it is clear that charged groups (except the trimethylamino group) promote liquid-to-solid transition by reducing its halftime (t1/2). A general trend is that negatively charged groups (phosphate and carboxyl) have more obvious effects than the positively charged groups (i.e. amino), an observation in line with different behaviors of Hofmeister anions and cations.[16] Compared to the carboxyl group, phosphate promotes liquid-to-solid transition more strongly, which has been explained by the facile formation of the hydration shell around the phosphate group with respect to the carboxyl group in the Hofmeister series.[17] On the other hand, the hydrophobic functional groups such as hydrocarbon chains and conjugated aromatic rings slow down the liquid-to-solid transition. It is consistent with the hydrophobic interaction between these hydrophobic functional groups and the hydrophobic residues in the Tau protein. It is interesting that trimethylamino group increases the halftime of the liquid-to-solid transition in the Tau condensates. Given that amino group moderately facilitates the transition (−30 min, Table 2) whereas methyl group demonstrates the strongest capability to inhibit the transition (+71 min, see Table 2), the net effect of the trimethylamino group is likely determined by its three methyl subgroups. As a result, the trimethylamino group still stabilizes the Tau protein, slowing down the liquid-to-solid transition (Figure 3). Such a result is consistent with the finding that TMAO, which contains a trimethylamino group, can stabilize proteins by directly interacting with the proteins[21].

By measuring the aspect ratio of two Tau condensate droplets using video microscopy, we characterized the liquid-to-solid transition in the Tau LLPS condensates. We quantified the effect of physiologically important molecules on the liquid-to-solid transitions. We revealed that the transition was driven by the loss of water among Tau molecules before the condensate became solid-like. We found that different functional groups in biologically important small molecules had variable effects on the liquid-to-solid transition of the Tau condensates. While charged groups facilitated the liquid-to-solid transition, the hydrophobic moieties inhibited the transition. These seminal findings help to develop small molecule drugs that can interfere with the aggregation of Tau proteins, which may change the formation of Tau fibrils responsible for the Alzheimer’s disease. We anticipate the innovative methods described here are instrumental to identify chemicals that can effectively modulate liquid-to-solid transition in LLPS condensates involved in many amyloidosis processes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research work was supported by National Science Foundation [CBET-1904921] and National Institutes of Health [NIH R01CA236350] to H.M.

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is available on the www under http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/anie.201xxxxxx.

Contributor Information

Sagun Jonchhe, Department of Chemistry & Biochemistry, Kent State University, Kent, Ohio 44242 (USA).

Wei Pan, Department of Chemistry & Biochemistry, Kent State University, Kent, Ohio 44242 (USA).

Pravin Pokhrel, Department of Chemistry & Biochemistry, Kent State University, Kent, Ohio 44242 (USA).

Hanbin Mao, Department of Chemistry & Biochemistry, Advanced Materials and Liquid Crystal Institute, Department of Biomedical Sciences, Kent State University, Kent, Ohio 44242 (USA).

Reference

- [1].(a) Hyman AA, Weber CA, Jülicher F, Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology 2014, 30, 39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Alberti S, Gladfelter A, Mittag T, Cell 2019, 176, 419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Lin Y, McCarty J, Rauch JN, Delaney KT, Kosik KS, Fredrickson GH, Shea J-E, Han S, eLife 2019, 8, e42571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Silberberg MS in Chemistry: The Molecular Nature of Matter and Change, 6th ed., McGraw-Hill, New York, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- [4].(a) Ray S, Singh N, Kumar R, Patel K, Pandey S, Datta D, Mahato J, Panigrahi R, Navalkar A, Mehra S, Gadhe L, Chatterjee D, Sawner AS, Maiti S, Bhatia S, Gerez JA, Chowdhury A, Kumar A, Padinhateeri R, Riek R, Krishnamoorthy G, Maji SK, Nat. Chem 2020, 12, 705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Wen J, Hong L, Krainer G, Yao Q-Q, Knowles TPJ, Wu S, Perrett S, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2021, 143, 13056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].(a) Serpell LC, Biochim. Biophys. Acta. Mol. Basis. Dis 2000, 1502, 16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Reynolds NP, Adamcik J, Berryman JT, Handschin S, Zanjani AAH, Li W, Liu K, Zhang A, Mezzenga R, Nat. Commun 2017, 8, 1338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Onuma K, Kanzaki N, J. Cryst. Growth 2007, 304, 452. [Google Scholar]

- [7].Biancalana M, Koide S, Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2010, 1804, 1405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Luchette P, Abiy N, Mao H, Sens. Actuators. B Chem 2007, 128, 154. [Google Scholar]

- [9].(a) Ghosh A, Zhou H-X, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2020, 59, 20837; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem 2020, 132, 21023 [Google Scholar]; (b) Patel A Lee Hyun O., Jawerth L, Maharana S, Jahnel M, Hein Marco Y., Stoynov S, Mahamid J, Saha S, Franzmann Titus M., Pozniakovski A, Poser I, Maghelli N, Royer Loic A., Weigert M, Myers Eugene W., Grill S, Drechsel D, Hyman Anthony A., Alberti S, Cell 2015, 162, 1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Wang J, Choi J-M, Holehouse AS, Lee HO, Zhang X, Jahnel M, Maharana S, Lemaitre R, Pozniakovsky A, Drechsel D, Poser I, Pappu RV, Alberti S, Hyman AA, Cell 2018, 174, 688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Kaur T, Alshareedah I, Wang W, Ngo J, Moosa MM, Banerjee PR, Biomolecules 2019, 9, 71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Alshareedah I, Kaur T, Ngo J, Seppala H, Kounatse L-AD, Wang W, Moosa MM, Banerjee PR, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2019, 141, 14593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Ghimire C, Koirala D, Mathis MB, Kooijman EE, Mao H, Langmuir 2014, 30, 1370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Murthy AC, Dignon GL, Kan Y, Zerze GH, Parekh SH, Mittal J, Fawzi NL, Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol 2019, 26, 637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].(a) Trojanowski JQ, Goedert M, Iwatsubo T, Lee VMY, Cell Death Differ. 1998, 5, 832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Molliex A, Temirov J, Lee J, Coughlin M, Kanagaraj Anderson P., Kim Hong J., Mittag T, Taylor JP, Cell 2015, 163, 123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Hernández-Vega A, Braun M, Scharrel L, Jahnel M, Wegmann S, Hyman BT, Alberti S, Diez S, Hyman AA, Cell Rep. 2017, 20, 2304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Dregni AJ, Mandala VS, Wu H, Elkins MR, Wang HK, Hung I, DeGrado WF, Hong M, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 2019, 116, 16357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Zhang Y, Cremer PS, Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol 2006, 10, 658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Yang Z, Journal of Biotechnology 2009, 144, 12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Wicky BIM, Shammas SL, Clarke J, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 2017, 114, 9882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Andreev M, de Pablo JJ, Chremos A, Douglas JF, J. Phys. Chem. B 2018, 122, 4029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Wegmann S, Eftekharzadeh B, Tepper K, Zoltowska KM, Bennett RE, Dujardin S, Laskowski PR, MacKenzie D, Kamath T, Commins C, Vanderburg C, Roe AD, Fan Z, Molliex AM, Hernandez-Vega A, Muller D, Hyman AA, Mandelkow E, Taylor JP, Hyman BT, The EMBO journal 2018, 37, e98049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Majumdar A, Dogra P, Maity S, Mukhopadhyay S, J. Phys. Chem. Lett 2019, 10, 3929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Liao Y-T, Manson AC, DeLyser MR, Noid WG, Cremer PS, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 2017, 114, 2479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.