Abstract

Family caregivers provide the majority of care for older and disabled family members living with an illness or disability. Although most caregivers want to provide high-quality care, many report providing care that is potentially harmful to care recipients. Given the consequences to health and wellbeing for both caregivers and care recipients associated with low-quality care, there is an imperative for health and social service professionals to identify opportunities to support the quality of family caregiving. We apply the Stress Process Model to review the preponderance of literature implicating quality of the relationship between caregivers and care recipients as a major factor contributing to quality of family caregiving. In drawing together literature on caregiving relationships and caregiving quality, this commentary identifies potentially modifiable intervention targets and relevant contextual variables to inform development of programs to support high quality family caregiving to older adults living with a chronic illness or disability.

Keywords: Family caregiving, care quality, interpersonal relationships

In the US, 17.7 million family members and friends provide the lion’s share of care to older adults living with a chronic or disabling condition who live in the community (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering & Medicine [NASEM], 2016). Family members are responsible for providing instrumental care, personal care, and increasingly complex care tasks to older persons who are unable to do these activities independently (Riffen et al., 2017). The need for family caregivers is expected to grow in coming decades, given the growth of the older adult population, as older persons are at heightened risk of experiencing conditions that cause functional and cognitive impairment (Gaugler, 2021; NASEM, 2016;). While many families report positive experiences of caregiving (e.g., increased closeness with care recipient), many also report high levels of stress, burden, financial loss, and poorer physical and mental health (AARP Public Policy Institute & National Alliance on Caregiving, 2020; Wolff et al., 2017).

Multiple evidence-based intervention programs exist to equip caregivers with practical information about caregiving, as well as psychoeducational programs to guide caregivers on how to cope with stress from caregiving (Gaugler, 2021; Gitlin et al., 2010; NASEM, 2016). Far fewer interventions and less clinical guidance exists for caregivers struggling with interpersonal relationships with care recipients (Quinn et al., 2009). This is an important oversight. Caregiving relationships typically emerge from premorbid relationships (e.g., wife, grandchild), each with unique histories, norms (e.g., patterns for handling conflict), and varying levels of resilience to cope with novel stressors from caregiving. There is growing evidence that relationships between caregivers and care recipients affect the quality of caregiving provided by family members and, consequently, caregivers’ and care recipients’ health and wellbeing (Cheng et al., 2014; Williams & Schaffer, 2001). In this commentary, we describe a modified version of the Stress Process Model to summarize how caregiving relationships affect quality of care; this framework can guide future empirical testing of relationship-focused intervention targets to support high quality family caregiving.

Quality of caregiving is a multidimensional concept that describes the extent to which caregivers deliver excellent care (e.g., making sure the care recipient’s favorite foods are available), adequate care (e.g., meeting all recipient care needs), and potentially harmful care (e.g., threatening the care recipient) (Christie et al., 2009). Notably, what it means to provide high quality care likely varies by culture; for example, the importance of the value filial piety among Chinese families means that “respect” may be a uniquely important component of care quality among Chinese care partners (Dong et al., 2014). Within this paper, “quality of care” is dichotomized to facilitate easier discussion, such that the term “high-quality” care describes care that is both excellent and adequate. “Low-quality” care means providing less than adequate and/or potentially harmful care, including elder mistreatment and neglect. The same caregiver can provide high-quality care when completing some care tasks, but low-quality care when completing others (Dooley, et al., 2007; Shaffer et al., 2007). The quality of care provided by a caregiver can also vary day-to-day (Pickering, et al., 2020).

Delivery of low-quality care is concerningly common among family caregivers. In a community sample, one-quarter of caregivers indicate providing potentially harmful care to the person they assist (Beach et al., 2005). In clinical samples with caregivers to people living with dementia, this rate approaches one-half (Wiglesworth et al., 2010). At the same time, many caregivers describe feeling satisfied from providing care to a family member and aim to provide care that improves their relative’s wellbeing (Cheng et al., 2015). The high prevalence of low-quality care from family members, despite an overall desire to provide high-quality care, has two implications. First, there are likely factors which prevent some family members from providing the high-quality care they would like to. Second, there may be an opportunity to intervene so that family members are better equipped to provide care that benefits both themselves and the care recipient. And yet, there is minimal evidence-based guidance about how health and social service providers can support family caregivers to provide high-quality care to the friends and relatives they assist (Dooley et al., 2007).

In this commentary, we identify potentially modifiable aspects pertaining to the caregiving relationships, as well as other relevant contextual factors, to empirically test and then integrate into interventions to promote high quality family caregiving. We do so by applying the Stress Process Model as a framework to make sense of the preponderance of literature implicating the quality of the relationship between caregivers and care recipients as a major contributing factor affecting quality of family caregiving. From this application, we identify opportunities for future research and possible intervention. We follow Quinn and colleagues (2009) in defining “relationship quality,” as a broad term referring to various aspects of the caregiving relationship (e.g., satisfaction, affect, attachment, emotional support, positive appraisal), largely from the perspective of the caregiver. A number of psychological measures have been used to measure relationship quality. Examples include the University of Southern California Longitudinal Study of Three-Generation Families scale (closeness, communication, similarity of views about life, and the degree of getting along; Mangen et al., 1988), as well as the measure of perceived strain and emotional support in a relationship developed by Schuster et al. (1990) and Walen & Lachman (2000).

Application of the Stress Process Model to Identify the Role of Relationship Quality in Affecting Quality of Caregiving

The Stress Process Model (SPM) is useful starting point for identifying how caregiving relationship quality is related to quality of care, as well as opportunities to intervene to prevent low-quality care by accounting for relationship quality (Pearlin et al., 1990). The Stress Process Model is frequently used to examine how various caregiving stressors affect caregiver health outcomes for the purpose of tailoring behavioral interventions targeted at the caregiver (Guay et al., 2017). According to this model, stress-related outcomes are the result of the accumulation and interaction of background/contextual factors (e.g., length of caregiving), primary stressors (e.g., stressors related to care recipient needs), and secondary stressors (e.g., financial strain). In addition, according to the SPM, resources and interventions can lower stress and thus attenuate negative outcomes (Pearlin et al., 1990).

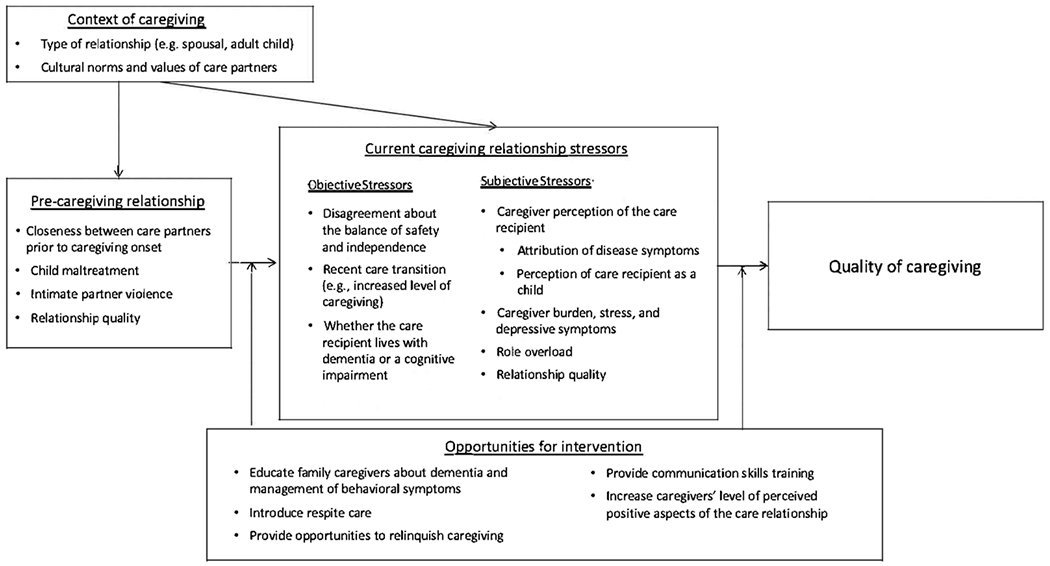

We adopt the SPM to examine relationship factors that contribute to an outcome of care quality because 1) the model is flexible and supports inclusion of a broad range of variables, an important feature given the complexity of this topic and 2) care quality has previously been described as a stress-related outcome within this model (Burnight & Mosqueda, 2011). Further, the inclusion of protective factors and resources in this model is particularly important given that not all caregivers who encounter stressors provide low-quality care (Brandl & Raymond, 2012). When considering an outcome of low-quality care, the relationship between the caregiver and care recipient is relevant at multiple points along the model: the context in which caregiving occurs, the pre-caregiving relationships, and the current relationship as it is affected by care-related stressors. How caregiving relationship quality is implicated in quality of care in accordance with the SPM is described in the sections that follow. Figure 1 summarizes this information and is referenced throughout remaining sections.

Figure 1:

Caregiving relationship quality and the Stress Process Model, as it affects quality of family caregiving

This figure is adapted from Pearlin et al., 1990, pp. 586. Although not depicted, it is recognized that care stressors and relationship quality may affect each other in a bi-directional manner

Importantly, although the SPM forms the basis of the proposed model, it also departs from the SPM in several ways. First, in the adapted model, we separate out pre-caregiving relationship factors from other sections of the model so as to emphasize the multiple ways in which the lifecourse of the relationship may affect quality of care outcomes. Secondly, the SPM was designed to describe an essentially linear process, wherein stressors on the left side of the model accumulate to affect those on the right side. However, in the model proposed, we also recognize the potential for components to, in some cases, affect each other bi-directionally. Finally, in the original Pearlin SPM, social support and coping are identified as possible protective factors. In the proposed model, we build upon these factors (e.g., improving coping ability by altering perspective), but also emphasize the role of education given the antecedents of care quality identified in the literature. With these differences in mind, in the conclusion of this commentary, we also identify an alternative, ecological adaptation of this model to guide future research and encourage future refinement to the model proposed.

The Context of the Caregiving Relationships

Within the Stress Process Model, the context in which caregiving occurs prefaces care-related stressors. For example, the effects of novel care stressors on care quality may be magnified within some caregiving situations (e.g., prior mistreatment in the relationship). The context of care also affects the resources caregivers have available to manage care stressors, such as prior knowledge of dementia. Within the modified version of the SPM presented in Figure 1, we identify contextual variables with high pertinence to care quality, including demographic characteristics of care partners. The examples provided in the section that follows represent key characteristics within the framework, but are not exhaustive.

Type of Caregiving Relationship

Spouses and adult children are among the most likely persons to provide care to older persons living with a chronic illness or disability, though the caregiving role and expectations differ considerably for adult children and spouses (NASEM, 2016). Adult children report higher levels of resentment towards care recipients than do spousal care partners; caregivers who endorse resentment are more likely to report engaging in low-quality and potentially harmful care behaviors (Macneil et al., 2010; Williamson & Shaffer, 2001). Given these unique situational factors that affect relationship quality according to relationship type, interventions should account for kinship differences among care partners.

Cultural Norms and Values of Care Partners

Caregiving occurs within the context of cultural values, norms, and expectations; thus, culture serves as a backdrop that shapes interpersonal caregiving relationships and care quality. For example, culturally-informed beliefs about the causes of illness may contribute to care relationship quality. In some cultures, dementia is considered to be a consequence of personal faults (e.g., poor self-care), which may affect how care recipients are treated by caregivers who sometimes blame recipients for their diminished cognitive functioning (Gerritsen et al., 2018). In addition, in a modified version of the SPM, Knight & Sayegh (2010) further assert that, cultural values impact resources and coping with care stressors, such as interpersonal strain. Additional research is needed on how culturally diverse populations of caregivers cope with evolving caregiving relationships (Roberto et al., 2011), and how this affects quality of caregiving.

Pre-Caregiving Relationship Quality and Linkages to Low-Quality Care

Pre-morbid relationship dynamics between caregivers and recipients may persist even after the onset of caregiving and can affect the quality of care provided, as represented in Figure 1 (“Pre-caregiving relationship”). Caregivers who describe feeling less close to the person they assist prior to onset of caregiving report higher levels of caregiver burden than those who enjoyed closer pre-caregiving relationships (Williamson & Schulz, 1990). Caregiver burden is a risk factor for lower quality caregiving (Orfila et al., 2018). Similarly, those with long-standing marital discord experience exacerbation of relationship tensions with the onset of caregiving (Anderson, & Keating, 2018; Blieszner et al., 2007). In some cases, intimate partner violence (IPV) occurring prior to caregiving onset continues into the care partnership; caregivers who were IPV victims may respond to ongoing, through often lessened, violence by providing low-quality care (Sanchez-Guzman et al., in press). In contrast, caregivers who report high premorbid relationship satisfaction are less reactive to stressful caregiving situations, including behavioral symptoms displayed among care recipients living with dementia (e.g., wandering) (Steadman et al., 2007).

Low Quality Parent-Child Relationships and Care Quality in Later Life

Early-life relationships between parents and children have echoes in later-life caregiving. Among adult child caregivers, experiencing poor early-life parental relationships predicts ambivalence towards care recipients (Willson et al., 2003). While ambivalence about the care recipient does not necessarily result in potentially harmful care—plenty of caregivers provide adequate care, even in the absence of strong positive feelings towards the care recipient (Solomon et al., 2017)— motivation to provide high-quality may be diminished. Among parent-adult child care dyads, there may also be ongoing animosity towards parental care recipients from early-life dynamics. An in-depth interview study by Pickering and colleagues (2015) found that caregivers who were mistreated by recipients in early life sometimes engage in “reciprocal abuse,” wherein adult child caregivers mistreat parents who mistreated them during childhood (Pickering et al., 2015). These authors also found that children mistreated early in life are content to provide adequate care, but not necessarily high-quality care. Further, some daughters limited exposure to mothers as a protective coping mechanism (Pickering et al., 2015). Although they may have contributed to reduced likelihood of verbal aggression, they likely increased risk of neglect (Pickering et al., 2015).

Current Caregiving Stress Affecting Relationship Quality and Links to Low-Quality Care

The introduction and escalation of care-related stressors can affect relationship quality, and may contribute to low-quality caregiving. Notably, the relationship between care stressors and relationship quality can be bi-directional: care stressors can affect relationship quality, and relationship quality can affect the experience of care stressors. Further, even relationships that would otherwise be characterized as high quality may, in cases where care partners experience role overload (Lawrence et al., 1998), contribute to low-quality care. Examples of this are described in the sections that follow, and are summarized in Figure 1 as “Current caregiving relationship stressors”. In adherence with the Pearlin SPM model, we further divide these stressors into objective and subjective stressors.

Cognitive Impairment and Dementia Among Care Recipients

Dementia status of the care recipient is an objective stressor and is known to have a uniquely strong impact on relationship quality. Caregivers to a person living with dementia report feeling less close to the care recipient, experience more conflict, and have fewer relationship rewards compared to caregivers to someone without a cognitive impairment (Townsend & Franks, 1995; Williamson & Shaffer, 2001). However, the relationship between dementia status and poor relationship quality has not been found in all studies. Lawrence and colleagues (1998) did not find a relationship between dementia status and relationship quality. However, these authors did identify an association between behavioral symptoms and relationship quality, suggesting that it is the behavioral symptoms that impact the dementia caregiving relationships more than other factors.

Behavioral symptoms of dementia are a known risk factor for potentially harmful caregiving (Beach et al., 2005; Pickering et al., 2020; Wiglesworth et al., 2010). The effect of behavioral symptoms on interpersonal relationships may explain why these behaviors have such a robust impact on care quality. Behavioral symptoms of dementia are often attributed to character flaws in the care recipient, rather than a manifestation of disease processes, and thereby their presence may affect caregivers through subjective processes (Bliezner et al., 2007). How caregivers cope with behavioral symptoms reflects how they perceive themselves in relationship to recipients of care, such as believing they need to control care recipient behaviors rather than managing these collaboratively (Rath et al., 2019). Several studies describe caregivers taking a coercive approach to managing behavioral symptoms; caregivers who believe coercive communication can resolve caregiving challenges are characterized as “proactively aggressive” (e.g., agreeing to statements such as, “A little threat can go a long way to solve problems when [care recipient] is being difficult,” Shaffer et al., 2007, pp. 497). Proactive aggression in caregivers is associated with providing low-quality care (Shaffer et al., 2007).

Negotiating New Roles and Expectations Following Caregiving Onset

Knobloch and colleagues describe transitions into and during caregiving as times during which relational turbulence is more likely to occur, since care partners renegotiate their roles in relation to one another (Knobloch et al., 2019). An important component of role renegotiation during care transitions, represented in Figure 1 as a type of objective stressor, is deciding upon the balance between safety and independence, a potential subjective stressor. This is particularly relevant when care recipients have diminished capacity to weigh this balance for themselves due to cognitive impairment and may disagree with caregivers’ efforts to curb their ability to engage in certain activities independently (Andersen & Keating, 2018; Blieszner, et al., 2007; Cheng et al., 2015; Roberto et al., 2011; Townsend & Franks, 1995). For example, a care recipient may insist on continuing to drive despite visual impairment (i.e., prioritization of independent choice), while the caregiver would prefer the recipient no longer drive (i.e., prioritization of safety). While conflict in the care relationship can be managed in healthy ways when it arises (e.g., compromising and limiting driving to daylight hours, if appropriate), some responses to conflict by caregivers can be characterized as low-quality caregiving, such as treating the recipient like a child or insulting the care recipient (Cheng et al., 2015; Roberto et al., 2011). Reponses to conflict may also extend from pre-caregiving conflict-management techniques, though may become detrimental to care recipients following onset of care and increased vulnerability (Pickering et al., 2015). Recipients who report that caregivers do not consider their wishes or do not ask for their opinions are at a higher risk of depression (Wolff & Agree, 2004), implicating this behavior as form of low-quality caregiving as well as an indicator of a low-quality relationship. Thus, altered perceptions of the care recipient by the caregiver are also described as a factor affecting relationship quality in modified SPM showed in Figure 1 (“Caregiver perception of the care recipient”).

High Quality Relationships Contributing to Caregiver Stress and Poorer Care Quality

Reflecting the complexity of caregiving relationships, in some cases, positive dimensions of care relationships can also contribute to caregiver stress and poorer caregiver wellbeing, which may affect caregivers’ ability to provide care that promotes recipient wellbeing (Lwi et al., 2017; Quinn et al., 2019). For example, in a study of relationship quality among spousal and adult child caregivers to someone with a severe disability, Lawrence and colleagues (1998) found that caregivers reporting high relationship quality also experienced role overload. Those with a positive relationship with recipients may be more inclined to provide a higher-level of care, thereby exposing themselves to greater care demands. Although some positive dimensions of caregiving relationships are associated with stress in some cases, and stress is a risk factor for low-quality care (Pickering et al., 2020), we are not aware of any research linking positive aspects of relationships to low-quality care. This topic merits additional research, and thus is represented in Figure 1 as a factor that could potentially affect quality of care.

Future Opportunities for Intervention Identified Within the Model

Relationship quality is an important contributor to caregiving quality by family members and to the health and wellbeing of both caregivers and recipients. The context of caregiving, pre-caregiving relationships, and current stressors each contain factors which interact and accumulate to effect quality of caregiving. Based on these areas of risk, we identify promising opportunities for intervention by social work researchers within the adapted stress process model presented in Figure 1 (“Opportunities for intervention”). Although we describe promising intervention targets to improve quality of care via the care relationship, additional basic research to discern the relative strength of direct and indirect associations between multiple components of relationships quality and context with quality care, such as studies that apply structural equation modeling approaches, are also warranted to information intervention.

Educate Caregivers on Dementia and Management of Behavioral Symptoms of Dementia

Evidence-based programs aimed to affect caregivers’ understanding of behavioral symptoms of dementia and their reactions to these may be particularly effective at improving caregiving relationship quality. Behavioral symptoms can greatly affect both relationship quality (Lawrence et al.,1998) and risk of low-quality care (Beach et al., 2005). Interventions such as the Care of Persons with Dementia in their Environments (COPE) program focuses on ways of managing behavioral symptoms, including identifying their triggers (Gitlin et al., 2010). Results from evaluation of this program suggest that attribution of behaviors to environmental factors, rather than personal attributes of the recipient, appears to lead to higher-quality care, such as the use of fewer negative communication strategies (e.g., yelling). Future research should further examine the efficacy of dementia education programs to improve quality of care, as mediated by relationship quality.

Identify Alternative Sources of Care and Respite Opportunities

When developing and researching interventions, it may be appropriate to include identify opportunities to advise or assist caregivers with reducing caregiving responsibilities where relationships are compromised, such as in cases of prior mistreatment, or even relinquishing the caregiving role (Ziminski & Phillips, 2011). Equally important is to find ways to help caregivers continue to provide care, if they choose, despite negative appraisal of their relationship with the care recipient, especially if there are legal requirements for families to provide care in some societies (Pearson, 2012). Respite care may help families to reduce contact with care recipients with whom they have a challenging relationship without risking neglectful or reactive care. Respite care demonstrably reduces levels of caregiver stress when providing care (Klein et al., 2016), so caregivers can better respond to care recipient’s needs.

Build Positive Caregiving Relationships and Communication Skills

It is important to recognize that positive aspects of relationships with care recipients also provide uplifts to caregivers that may dampen potential adverse caregiver responses to objective stressors. In a diary study of caregivers to persons with Alzheimer’s Disease in Taiwan, caregivers expressed joy when recipients showed affection or tried to be helpful to caregivers (Cheng et al., 2015). In a recent dyadic analysis of spousal care partners, high levels of perceived emotional support from a partner were associated with lower levels of depression for both caregivers and recipients of care (Meyer et al., In press) This is important as depression is a risk factor for low-quality care (Lwi et al., 2017; Wiglesworth et al., 2010). Thus, interventions that promote positive and rewarding caregiving relationships may be an avenue to improve quality of caregiving and care recipient wellbeing. Building communication skills to help care partners navigate changing roles may be one way to do this, and may be particularly important for care partners who are negotiating new role expectations (Knobloch et al., 2019).

Conclusion

Caregiving often marks a new stage in existing relationships, introducing novel stressors that may, in turn, affect the quality of care provided by families. The modified version of the Stress Process Model presented here can serve as a guide to future research to develop interventions to address relationship quality as a way to improve quality of care. Specifically, future research should continue to examine empirically which aspects of relationship quality most affect the quality of care provided by family members both directly and indirectly (e.g., resentment towards care recipients, negative attribution) and to determine whether relationship quality may be modified through intervention to affect care quality. This may involve the development of novel intervention programs, as well as evaluation of existing programs that address risk factors for low-quality caregiving relationships for their efficacy in improving care quality. Further, we recognize that an ecological model that addresses individual, dyadic, and contextual factors may also complement the proposed model, and may be better suited to integrate bi-directional aspects of this model. As such, we recommend further refinement of the model proposed, such as through qualitative inquiry.

References

- AARP Public Policy Institute & National Alliance for Caregiving. (2020, May). Caregiving in the U.S. 2020. https://www.caregiving.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/full-report-caregiving-in-the-united-states-01-21.pdf

- Anderson S & Keating N (2018). Marriage after the transition to stroke: a systematic review. Ageing & Society, 38(11), 2241–2279. 10.1017/S0144686X17000526 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beach SR, Schulz R, Williamson GM, Miller LS, Weiner MF, & Lance CE, (2005). Risk factors for potentially harmful informal caregiver behavior. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 53(2), 255–261. 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2007.00452.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blieszner R, Roberto KA, Wilcox KL, Barham EJ & Winston BL (2007). Dimensions of Ambiguous Loss in Couples Coping with Mild Cognitive Impairment. Family Relations, 56(2), 196–209. 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2007.00452.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brandl B & Raymond J (2012). Policy implications of recognizing that caregiver stress is not the primary cause of elder abuse. Generations, 36(3), 32–39. [Google Scholar]

- Burnight K & Mosqueda L (2011). Theoretical model development in elder mistreatment. Report for the US Department of Justice. (No. 234488). https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/grants/234488.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Cheng ST, Lau RW, Mak EP, Ng NS, & Lam LC (2014). Benefit-finding intervention for Alzheimer caregivers: conceptual framework, implementation issues, and preliminary efficacy. The Gerontologist, 54(6), 1049–1058. 10.1093/geront/gnu018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng ST, Mak EP, Lau RW, Ng NS, & Lam LC (2015). Voices of Alzheimer caregivers on positive aspects of caregiving. The Gerontologist, 56(3), 451–460. 10.1093/geront/gnu118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christie J, Smith GR, Williamson GM, Lance CE, Shovali TE, & Silva LC (2009). Quality of informal care is multidimensional. Rehabilitation Psychology, 54(2), 173–181. 10.1037/a0015705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong X, Zhang M, & Simon MA (2014). The expectation and perceived receipt of filial piety among Chinese older adults in the Greater Chicago area. Journal of Aging & Health, 26(7), 1225–1247. 10.1177/0898264314541697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dooley WK, Shaffer DR, Lance CE, & Williamson GM (2007). Informal care can be better than adequate: Development and evaluation of the Exemplary Care Scale. Rehabilitation Psychology, 52(4), 359–369. 10.1037/0090-5550.52.4.359 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gaugler J, (Ed.) (2021). Bridging the Family Care Gap. Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gerritsen DL, Oyebode J, & Gove D (2018). Ethical implications of the perception and portrayal of dementia. Dementia, 17(5), 596–608. doi: 10.1177/1471301216654036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitlin LN, Winter L, Dennis MP, Hodgson N, & Hauck WW (2010). A biobehavioral home-based intervention and the well-being of patients with dementia and their caregivers: the COPE randomized trial. JAMA, 304(9), 983–991. 10.1001/jama.2010.1253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guay C, Auger C, Demers L, Mortenson WB, Miller WC, Gélinas-Bronsard D, & Ahmed S (2017). Components and outcomes of internet-based interventions for caregivers of older adults: systematic review. Journal of Medical Internet research, 19(9), e313. 10.2196/jmir.789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein LC, Kim K, Almeida DM, Femia EE, Rovine MJ & Zarit SH (2016). Anticipating an easier day: Effects of adult day services on daily cortisol and stress. The Gerontologist, 56(2), 303–312. 10.1093/geront/gnu060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence R, Tennstedt S, & Assmann S (1998). Quality of the caregiver-care recipient relationship: Does it offset negative consequences of caregiving for family caregivers? Psychology and Aging, 13(1), 150–158. 10.1037/0882-7974.13.1.150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Kong J, Bangerter LR, Zarit SH, & Almeida DM (2018). Early parental abuse and daily assistance to aging parents with disability: Associations with the middle-aged adults’ daily well-being. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 73(5), e59–e68. 10.1093/geronb/gbx173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lwi SJ, Ford BQ, Casey JJ, Miller BL, & Levenson RW (2017). Poor caregiver mental health predicts mortality of patients with neurodegenerative disease. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114(28), 7319–7324. 10.1073/pnas.1701597114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight BG & Sayegh P (2010). Cultural values and caregiving: The updated sociocultural stress and coping model. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 65(1), 5–13. 10.1093/geronb/gbp096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knobloch LK, Nichols LO, & Martindale-Adams J (2019). Applying Relational Turbulence Theory to Adult Caregiving Relationships. The Gerontologist, 60(4), 598–606. 10.1093/geront/gnz090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macneil G, Kosberg JI, Durkin DW, Dooley WK, Decoster J, & Williamson GM (2010). Caregiver mental health and potentially harmful caregiving behavior: the central role of caregiver anger. The Gerontologist, 50(1), 76–86. 10.1093/geront/gnp099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangen D, Bengtson V, & Landry P (Eds). (1988). Measurement of Intergenerational Relations. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer K, Patel N & White C (In press). A dyadic analysis of perceived support from a spousal care partner on caregiver and care recipient depression. Aging and Mental Health. 10.1080/13607863.2020.1836474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orfila F, Coma-Sole M, Cabanas M, Cegri-Lombardo F, Moleras-Serra A, & Pujol-Ribera E (2018). Family caregiver mistreatment of the elderly: prevalence of risk and associated factors. BMC Public Health, 18(1), 167–181. 10.1186/s12889-018-5067-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin Leonard I., Mullan Joseph T., Semple Shirley J., & Skaff Marilyn M. (1990). Caregiving and the stress process: An overview of concepts and their measures. The Gerontologist, 30(5), 583–594. 10.1093/geront/30.5.583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson KC, (2012). Filial support laws in the modern era: Domestic and international comparison of enforcement practices for laws requiring adult children to support indigent parents. Elder Law Journal, 269(20). [Google Scholar]

- Pickering C, Yefimova M, Maxwell C, Puga F, Sullivan T (2020). Daily Context for Abusive and Neglectful Behavior in Family Caregiving for Dementia. The Gerontologist, 60(3), 483–493. 10.1093/geront/gnz110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickering C, Moon A, Pieters H, Mentes J, & Phillips L (2015). Relationship management strategies for daughters in conflicted relationships with their ageing mothers. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 71(3), 609–619. 10.1111/jan.12547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn C, Clare L, & Woods B (2009). The impact of the quality of relationship on the experiences and wellbeing of caregivers of people with dementia: A systematic review. Aging & Mental Health, 13(2), 143–154. 10.1080/13607860802459799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn C, Nelis SM, Martyr A, Morris RG, Victor C, & Clare L (2019). Caregiver influences on ‘living well’for people with dementia: Findings from the IDEAL study. Aging & Mental Health, 24(9), 1505–1513. 10.1080/13607863.2019.1602590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberto K, McCann B, & Blieszner R (2011). Trajectories of care: Spouses coping with changes related to mild cognitive impairment. Dementia, 12(1), 45–62. 10.1177/1471301211421233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rath L, Meyer K, Avent E, Nash P, Benton D, Gassoumis Z, & Wilber KH (2019). Supporting Family Caregivers: How Do Caregivers of Older Adults Cope with Role Strain? A Qualitative Study. Innovation in Aging, 3(Supplement_1), S489–S489. 10.1093/geroni/igz038.1816 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Guzman MA, Paz-Rodriguez F, Espinola Nadurille M, & Trujillo-De Los Santos Z (In press). Intimate Partner Violence in Persons with Parkinson’s Disease. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 10.1177/08862605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering & Medicine. (2016). Families caring for an aging America. Washington, DC. https://nam.edu/families-caring-for-an-aging-america/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riffin C Van Ness PH, Wolff JL & Fried T. (2017) Family and Other Unpaid Caregivers and Older Adults with and without Dementia and Disability. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 65(11): 1821–1828. 10.1111/jgs.14910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuster TL, Kessler RC, & Aseltine RH (1990). Supportive interactions, negative interactions, and depressed mood. American Journal of Community Psychology, 18(3), 423–38. 10.1007/BF00938116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer DR, Dooley WK, & Williamson GM (2007). Endorsement of proactively aggressive caregiving strategies moderates the relation between caregiver mental health and potentially harmful caregiving behavior. Psychology and Aging, 22(3), 494–504. 10.1037/0882-7974.22.3.494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon DN, Hansen L, & Baggs JG (2017). It’s All About the Relationship: Cognitively Intact Mother–Daughter Care Dyads in Hospice at Home. The Gerontologist, 58(4), 625–634. 10.1093/geront/gnw263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steadman P, Tremont G, & Duncan Davis J (2007). Premorbid relationship satisfaction and caregiver burden in dementia caregivers. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology, 20(2), 115–119. 10.1177/0891988706298624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Townsend A & Franks M, (1995). Binding ties—closeness and conflict in adult children’s caregiving relationships. Psychology & Aging, 10(3), 343–351. 10.1037/0882-7974.10.3.343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walen H & Lachman M. (2000). Social support and strain from partner, family, and friends: Costs and benefits for men and women in adulthood. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 17(1):5–30. 10.1177/0265407500171001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wiglesworth A, Mosqueda L, Mulnard R, Liao S & Gibbs L (2010). Screening for Abuse and Neglect of People with Dementia. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 58(3), 493–500. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02737.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson G, & Schulz R (1990). Relationship orientation, quality of prior relationship, and distress among caregivers of Alzheimer’s patients. Psychology & Aging, 5(4), 502–509. 10.1037/0882-7974.5.4.502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson G, & Shaffer D (2001). Relationship quality and potentially harmful behaviors by spousal caregivers: How we were then, how we are now. The Family Relationships in Late Life Project. Psychology and Aging, 16(2), 217–226. 10.1037/0882-7974.16.2.217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willson A, Shuey K, & Elder G (2003). Ambivalence in the Relationship of Adult Children to Aging Parents and In-Laws. Journal of Marriage and Family, 65(4), 1055–1072. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2003.01055.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff JL, & Agree EM, (2004). Depression among recipients of informal care: The effects of reciprocity, respect, and adequacy of support. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 59(3), S173–S180. 10.1093/geronb/59.3.S173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff JL, Spillman BC, Freedman VA, Kasper J (2016). A National Profile of Family and Unpaid Caregivers Who Assist Older Adults With Health Care Activities. JAMA Internal Medicine 176(3): 372–379. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.7664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeminski CE & Phillips LR (2011). The Nursing Role in Reporting Elder Abuse: Specific Examples and Interventions. Journal of Gerontological Nursing, 37(11), 19–23. 10.3928/00989134-20111010-01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]